Abstract

The ability of bacteria to commit to surface colonization and biofilm formation is a highly regulated process. In this study, we characterized the activity and structure of SadB, initially identified as a key regulator in the transition from reversible to irreversible surface attachment. Our results show that SadB acts as an adaptor protein that tightly regulates the master regulator AmrZ at the post-translational level. SadB directly binds to the C-terminal domain of AmrZ, leading to its rapid degradation, primarily by the Lon protease. Structural analysis suggests that SadB does not directly interact with small molecules upon signal transduction, differing from previous findings in Pseudomonas fluorescens. Instead, the SadB structure supports its role in mediating protein-protein interactions, establishing it as a major checkpoint for biofilm commitment.

Subject terms: Biofilms, Pathogens

Introduction

The Gram-negative bacterium Pseudomonas aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen that can cause severe, life-threatening infections in immuno-compromised individuals and is a leading pathogen associated with hospital-acquired infections1–3. It is not only a successful colonizer that can induce acute infections, but also a persistent survivor, and thus responsible for numerous chronic infections1,4,5. The persistence of P. aeruginosa during such infections has been linked, in part, to its ability to form biofilms6. Biofilm formation involves a specialized mode of growth in which bacterial cells adhere to each other and/or to a surface, at which time they secrete extracellular polymers7–10. A biofilm develops in a continuous process in which bacterial cells initially convert from a reversible to an irreversible mode of surface attachment, followed by proliferation and aggregation to form microcolonies. As the process continues, microcolonies become mature biofilms11. Biofilm formation, an extremely convoluted process, is highly dependent on surface-associated motile behavior12,13. Despite considerable advancements realized in biofilm research, those signals and processes that regulate biofilm formation are still not entirely understood.

Cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) has been identified as major intracellular signal that coordinates the transition from a motile to sessile lifestyle in a wide range of species, including P. aeruginosa14. Specifically, elevated levels of cellular c-di-GMP have been associated with increased biofilm formation, enhanced exopolysaccharide (EPS) synthesis and production of attachment factors. Conversely, low levels of c-di-GMP promote a planktonic lifestyle, enhanced motility and virulence15.

Nonetheless, c-di-GMP is not the only factor known to influence this transition, as it has been shown that biofilm formation involves numerous regulators11. In recent years, efforts have focused on the initial steps in biofilm formation, most notably the commitment of the bacteria to proceed with biofilm formation rather than transition back to the planktonic form16–18.

One such regulator is SadB, first identified in a surface attachment defective (sad) mutant screen, where it was found to control the transition from reversible to irreversible attachment19. A mutation in sadB results in enhanced swarming motility and reduced biofilm formation20. SadB is thought to work upstream of components in the CheIV chemotaxis cluster (i.e., PilJ and ChpB), affecting flagellar reversal rates and matrix polysaccharide production20, and downstream of the diguanylate cyclase (DGC) SadC21 and the phosphodiesterase (PDE) BifA22. Although the activity of SadB has yet to be determined, it was hypothesized that SadB could act upstream of c-di-GMP synthesis or that SadB somehow transmits the c-di-GMP signal to downstream targets18, most of which remain unknown.

In this study, we characterized SadB activity and uncovered its role in biofilm formation. By combining proteomic and transcriptomic analyses of a sadB mutant, versus the wild-type (WT) strain, we were able to decipher that SadB post-translationally regulates AmrZ, a master regulator controlling biofilm formation, motility, and polysaccharide production23. We further demonstrated that SadB tightly regulates AmrZ levels by acting as an adaptor protein via direct binding to the AmrZ C-terminal domain, causing AmrZ to undergo rapid degradation, mainly mediated by the Lon protease. Our structural analysis of SadB, however, argues that it is highly unlikely that SadB binds c-di-GMP or other ligands for signal transduction and activation. Together, these findings establish SadB as a central post-translational regulator and a crucial factor in determining commitment to a biofilm lifestyle.

Results

SadB regulates levels of the transcription factor AmrZ and the phosphodiesterase ProE

SadB shows sequence homology to the YbaK family of tRNA editing proteins (Supplementary Fig. 1A). This may suggest post transcription regulation capabilities, as after transcription, tRNAs undergo various processing events, including numerous modifications that make them fully functional. Some of these modifications not only influence tRNA structure but can also change its functional role and decoding properties24. Indeed, suppression of rare tRNAs has been shown to impair biofilm formation in Escherichia coli25. As such, we considered whether SadB controls biofilm formation and swarming motility via tRNA editing. Accordingly, we performed proteomics and transcriptomics analyses of a ∆sadB mutant, as compared to the WT strain, searching for genes with uncorrelated transcription and translation. We found that in most genes identified, when mRNA levels are elevated, protein levels are correspondingly high, and vice versa (Fig. 1A). Two proteins, namely, AmrZ and PA5295 (ProE), which were overexpressed in the ∆sadB mutant, presented mRNA levels that were either unchanged (ProE) or down-regulated (AmrZ) (Fig. 1A). These results were corroborated by western blotting and real-time PCR (Fig. 1B, C).

Fig. 1. AmrZ and ProE levels are post-translationally regulated by SadB.

A Scatter plot of a Spearman correlation of proteomics and transcriptomics results of a sadB mutant (ΔsadB) strain, as compared to the WT strain, presented as log of fold-change. Spearman’s rho was 0.603 and the p value was <0.00001. B Western blot exhibiting FLAG-conjugated AmrZ and ProE expression levels in a sadB over-expressing strain (pOE sadB) and in a sadB mutant strain carrying an empty vector (ΔsadB/pUCP18), as compared to the WT strain carrying an empty vector (PAO1/pUCP18). The image is representative of three independent repeats. C Real-time PCR analysis measuring amrZ and proE mRNA levels in a sadB over-expressing strain (pOE sadB) and a sadB mutant strain transformed with an empty vector (ΔsadB/pUCP18), as compared to the WT strain also transformed with an empty vector (PAO1/pUCP18).

AmrZ is a global transcriptional regulator that controls biofilm formation and motility 26. It can act both as an activator and a repressor27, regulating genes involved in polysaccharide production, type IV pili, and flagellar function28. AmrZ plays a crucial role in the transition between planktonic and biofilm lifestyles by modulating the expression of biofilm-associated genes and repressing flagellar motility28–30. Interestingly, phenotypes associated with high levels of AmrZ are similar to those observed with a sadB deletion strain. Elevated AmrZ levels suppress Psl production and c-di-GMP synthesis, leading bacteria to exhibits a faster and expanded swarming area (i.e., hyper swarming), and form thin biofilms that lack prominent microcolonies, similar to the biofilm formed by ∆sadB28,30,31. ProE, on the other hand, is a phosphodiesterase which appears to play a crucial role in EPS production32.

Deletion of amrZ suppresses hyper-swarming in a ∆sadB mutant and, when combined with proE deletion, restores biofilm formation

To assess the impact of AmrZ and ProE on the ∆sadB phenotypes, single (i.e., ∆amrZ and ∆proE), double (i.e., ∆sadB∆amrZ and ∆sadB∆proE), and triple (i.e., ∆sadB∆amrZ∆proE) mutants were constructed. When examining the swarming phenotypes our data suggest that the deletion of amrZ was sufficient to completely eliminate hyper swarming activity (Fig. 2A).

Fig. 2. AmrZ and ProE mutants abolish ΔsadB-related phenotypes.

A Swarming assay. B Static biofilm assay. C Flow cell assay and imaris biovolume quantification of the flow cell results. D Cellular c-di-GMP measurements for the WT, sadB mutant (ΔsadB), amrZ mutant (ΔamrZ), proE mutant (ΔproE), sadB amrZ double mutant (ΔsadB ΔamrZ), sadB proE double mutant (ΔsadB ΔproE) and the sadB amrZ proE triple mutant (ΔsadB ΔamrZ ΔproE) strains. The static biofilm assay reflects the average of three independent repeats, with each experiment involving six replicates. Error bars represent standard deviation. For the swarming assay, a representative plate of each strain from three replicates in three independent experiments is shown. For the flow cell assay, one representative image of each strain of three independent experiments is shown. In cellular c-di-GMP measurements, each bar represents the average of three independent experiments. * Indicates a statistically significant result where P < 0.05, ** indicates a statistically significant result where P < 0.01 and *** indicates a statistically significant result where P < 0.001.

As for the biofilm phenotype, deleting amrZ and proE restored biofilm formation in the ∆sadB mutant background (Fig. 2B, C). Furthermore, c-di-GMP levels were measured across all mutant strains. The ∆sadB mutant had very low c-di-GMP levels, consistent with its observed phenotypes. In contrast, the c-di-GMP levels in the ∆sadB∆amrZ mutant were similar to those of the wild-type strain (Fig. 2D).

The swarming and biofilm phenotype in the ∆amrZ mutant closely resembles the ones observed in strains with overexpressed SadB (Supplementary Fig. 1B–D). This provides additional evidence that the swarming and biofilm defects in the ∆sadB mutant are directly linked to its regulation of AmrZ.

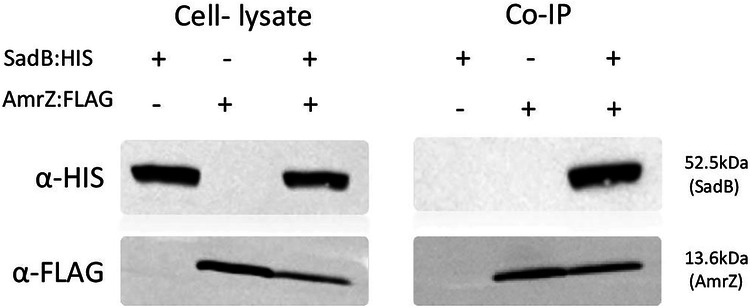

SadB directly binds AmrZ

The sequence similarity between SadB and members of the tRNA editing protein family led us to evaluate whether SadB controls biofilm formation and swarming motility via tRNA editing. To do so, we substituted all rare codons (~20%) in the mRNA sequence of amrZ with common ones (Supplementary Fig. 2A), without altering the translated protein sequence. No effect was detected, with SadB-mediated regulation of AmrZ levels being maintained, despite the absence of rare codons in the amrZ mRNA sequence (Supplementary Fig. 2B), suggesting that rare codon tRNAs are not targeted by SadB. This led us to hypothesize that SadB directly regulates AmrZ at the protein level. To confirm this idea, we conducted a co-immunoprecipitation (co-IP) assay, which confirmed direct interaction between SadB and AmrZ (Fig. 3). To further corroborate this finding, we employed a magnetic modulation biosensing (MMB) system which we recently developed33. In this assay, a magnetic bead binds to one protein, and a fluorescent molecule binds to another. When the proteins interact, the bead is moved by a magnetic field through a laser, creating a detectable oscillating signal. The MMB system results supported the co-IP data, demonstrating that SadB indeed directly binds to AmrZ (Supplementary Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3. SadB interacts with AmrZ at the protein level.

Co-Immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG resin testing for interactions between co-expressed polyhistidine-conjugated SadB and FLAG-conjugated AmrZ using the sadB:HIS and amrZ:FLAG. Cell lysates from SadB- (sadB:HIS) and AmrZ-expressing cells (amrZ:FLAG) served as negative controls. The blot shown is representative of three independent repeats.

The presence of SadB leads to rapid AmrZ degradation

Our results indicate that SadB-mediated regulation of AmrZ occurs at the protein level, with the presence of SadB resulting in decreased AmrZ levels. Moreover, we have shown that SadB and AmrZ directly interact. Thus, our next step was to examine whether SadB is responsible for AmrZ degradation. We, therefore, developed a degradation assay in which AmrZ levels are measured at different time points following sadB induction. For this, two plasmids were constructed, the first mediating the continuous over-expression of AmrZ and the second expressing SadB under the control of an arabinose-inducible promoter. The latter plasmid also contained a defective ribosome-binding site (pRBSmod), ensuring that in the absence of arabinose, no trace amounts of SadB would be produced. This modification was necessary because with a partially leaky promoter, even in the absence of arabinose, minimal amounts of SadB would be expressed, resulting in a significant reduction in AmrZ levels (Supplementary Fig. 3B). Using this assay, we were able to demonstrate that once SadB was expressed, AmrZ underwent degradation. Approximately 90 min after induction of SadB expression, even at concentrations not detectable by western blot, the majority of AmrZ was already degraded (Supplementary Fig. 3C). These findings suggest that even extremely low levels of SadB can regulate AmrZ levels.

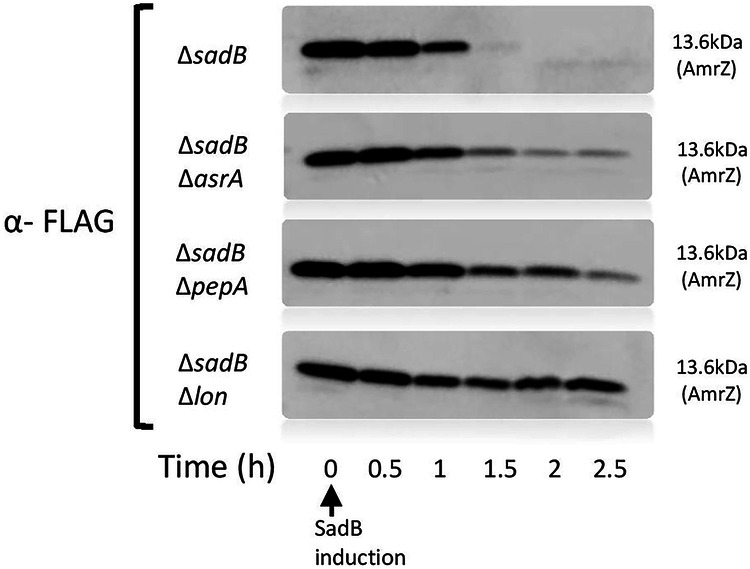

SadB mediates AmrZ degradation via proteolysis, mainly by the quality control protease Lon

Since there is no evidence supporting SadB as possessing enzymatic activity, we hypothesized that SadB interacts with other proteins to mediate AmrZ degradation. To test our hypothesis, we performed a cell lysate pull-down assay followed by mass spectrometry (Supplementary Table 1) on a strain over-expressing His-tagged SadB and found that three of the top six hits were proteases (namely, AsrA, PepA, and Lon). We next created deletion mutant strains lacking each of the three candidate proteases and assessed AmrZ degradation in each mutant. Our results clearly show that the absence of any of these proteases impacted AmrZ degradation brought about by the presence of SadB, with the most prominent effect being observed in cells lacking the Lon protease (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. SadB promotes AmrZ degradation through proteolysis, primarily by the quality control protease Lon.

A degradation assay of FLAG-conjugated AmrZ over time after SadB appearance (∆sadB/ pRBSmod sadB:HIS and pOE amrZ:FLAG) in mutant strains deleted of different protease (∆sadB∆asrA, ∆sadB∆pepA, ∆sadB∆lon). Each blot is a representative of 3 independent repeats.

A highly conserved amino acid region adjacent to the C-terminal end of AmrZ is essential for the degradation process

To delineate the domain within AmrZ required for SadB-mediated activity, we compared the amino acid sequences of AmrZ across Pseudomonas species. Certain regions, particularly the DNA-binding domain, are highly conserved, while the remaining sequence is variable (Fig. 5A). Interestingly, an exception was found in that sequence, ten amino acids near the C-terminus, which is conserved. We proposed that this sequence serves a regulatory function and influences the ability of SadB to mediate AmrZ degradation. To test this, we constructed two modified AmrZ constructs, one not encoding the last ten amino acids and the second not encoding the final twenty residues which contains most of the conserved sequence, with the deletions being made immediately upstream of the stop codon (Fig. 5B). A degradation assay confirmed the crucial role of the ten conserved amino acids in AmrZ degradation, as removing this sequence completely abolished SadB-mediated regulation of the process (Fig. 5C). Furthermore, when we replaced just three amino acids (i.e., Q91A, A94Q and L95Q) within this conserved sequence (Fig. 5D), we obtained similar results, namely, that AmrZ was not degraded upon activation of SadB (Fig. 5E).

Fig. 5. The degradation process depends on a conserved amino acid residue located near the C-terminal end of AmrZ.

A ConSurf results of AmrZ, presenting conservation/variability of amino acids between numerous Pseudomonas species. The blue square highlights the conserved region within the variable sequence. B A diagram presenting different amrZ constructs, namely, complete amrZ and amrZ lacking the sequence encoding the C-terminal ten amino acids (amrZ(-10C):FLAG) or the last twenty residues (amrZ(-20C):FLAG). C A degradation assay of the different AmrZ:FLAG constructs (pOE amrZ:FLAG, pamrZ(-10C):FLAG, pamrZ(-20C):FLAG) over time following SadB appearance (∆sadB/pRBSmod sadB:HIS). Each blot is a representative of three independent repeats. D A diagram presenting the three C-terminal domain point mutations (PM) introduced into amrZ (pamrZ(PM):FLAG), encoding Q91A, A94Q or L95Q. E A degradation assay of the different AmrZ:FLAG constructs (pOEamrZ:FLAG, pamrZ(PM):FLAG) following SadB appearance (∆sadB/pRBSmod sadB:HIS). Each blot is a representative of three independent repeats.

The conserved C-terminal sequence plays a key role in SadB binding and regulatory function

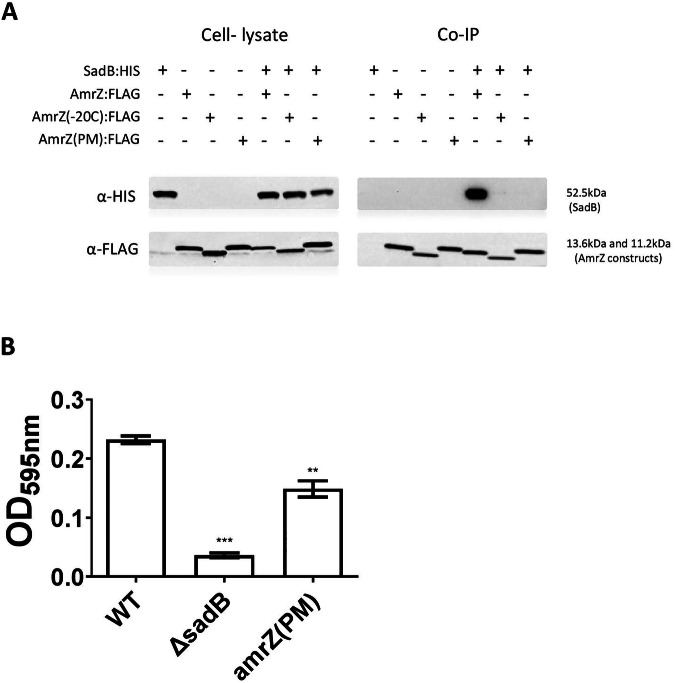

Having identified this C-terminal regulatory sequence, we examined what role it serves in mediating AmrZ degradation. Specifically, we tested whether SadB could bind the modified AmrZ protein in which the three amino acids were replaced (Fig. 5D). An immunoprecipitation assay clearly showed that SadB could not bind this AmrZ variant (Fig. 6A) and, therefore, could not trigger the process leading to its degradation. Lastly, substituting the genomic amrZ with the variant in which these three specific amino acids were replaced resulted in a significant reduction in biofilm formation, which correlates with elevated AmrZ levels (Fig. 6B).

Fig. 6. The conserved C-terminal sequence is crucial for SadB binding and regulation.

A Co-Immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG resin testing for interaction between co-expressed Poly histidine-conjugated SadB and different constructs of FLAG-conjugated AmrZ (sadB:HIS and amrZ:FLAG; amrZ(-20C):FLAG; amrZ(PM):FLAG). Cell lysates from SadB (sadB:HIS) and AmrZ-expressing cells (amrZ:FLAG, amrZ(-20C):FLAG and amrZ(PM):FLAG) served as negative controls. The blot is representative of three independent repeats. B static biofilm assay comparing the WT strain (WT), a sadB mutant (ΔsadB) and a 3 amino acid point-mutated AmrZ variant that is resistant to SadB binding and subsequent degradation (amrZ(PM)). An average of 3 independent experiments is presented; each experiment contains six replicates. Error bars represent the standard deviation. ** indicates a statistically significant result where P < 0.01 and *** indicates a statistically significant result where P < 0.001.

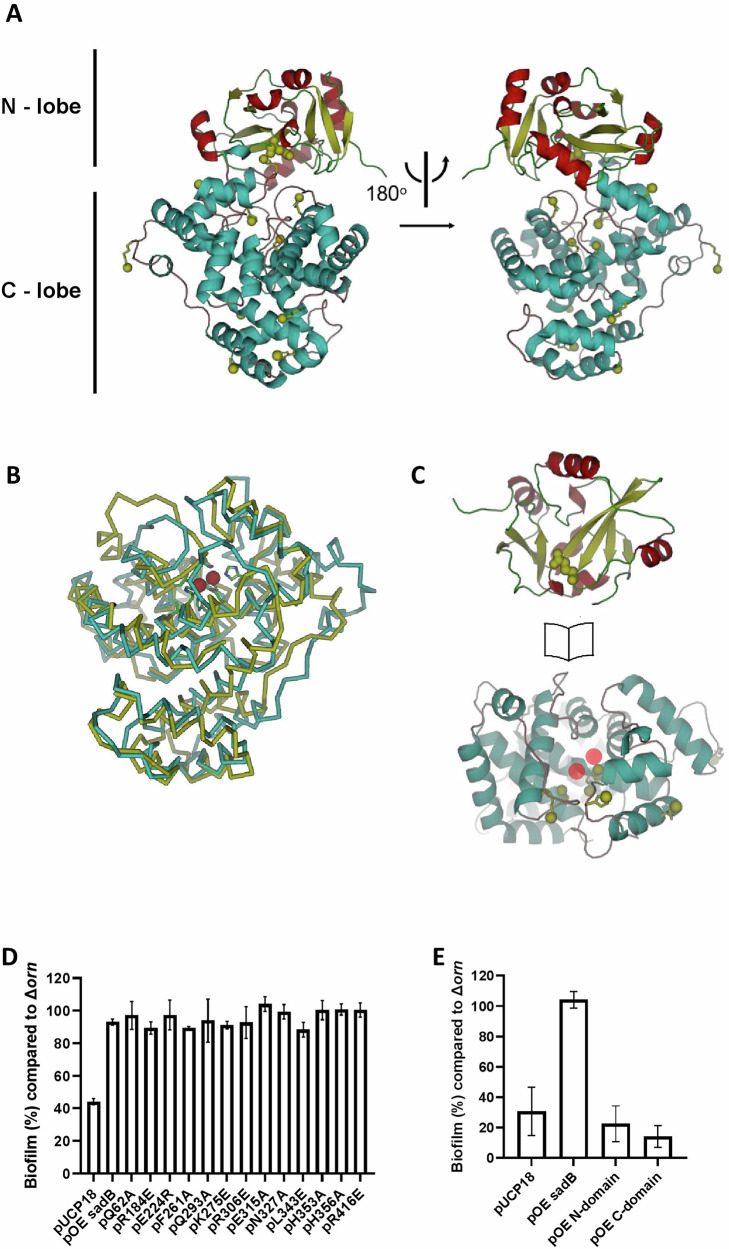

Analysis of the SadB structure

To further characterize SadB, we determined its crystal structure. The structure (Fig. 7A–C) includes two distinctive domains (designated henceforth as the N- and C-domains), namely, a 150 residue-long N-terminal Ybak/ProRS-like domain (also resembling the SacY-like RNA-binding domain), and a 310 residue-long C-terminal HDOD domain. The proximal N- and C-domains are organized so as to create a large cleft between them. The N-domain displays a curved structure with a split seven-stranded (designated βA–G) beta sheet surrounded by seven short helices (designated αA–F) (Supplementary Fig. 4). The beta sheet is split in its center, with the neighboring βB and βE being set apart. This is a hallmark of Ybak/ProRS-like domains, as first described for the crystal structure of the YbaK protein from Haemophilus influenzae (HI1434)34. The C-domain is all-helical with 17 short and long α-helices (designated α1–17) and is arranged as a compact, globular domain around the long core α9 helix.

Fig. 7. Biofilm modulation by SadB does not require ligand binding to the HDOD pocket, although both the N– and C-domains are necessary.

A Domain organization of SadB, with the N-domain colored red and yellow, and the C-domain cyan. Note the groove between the two domains. Sites modified by site-directed mutagenesis performed in this study are highlighted by green spheres. B Super-imposition of the SadB C-domain (cyan) and the HDOD domain from G. sulfurreducens (PDB entry 3HC1) with two iron ions bound in the HDOD pocket (red spheres). While iron coordination in the G. sulfurreducens structure is mediated by five histidine residues and one aspartate residue, the corresponding sites in SadB lack three histidine residues. C “Open book” representation of the separated N- and C-domains, revealing the inter-domain interacting surfaces. D&E. Static biofilm assay, with the genetic background of all the tested strains being ΔsadBΔorn. All SadB modifications are indicated in Supplementary Fig. 4. D Examining the effects of 13 different point mutations on SadB behavior. E Testing the behavior of the SadB N- and C-domains on their own. The average of three independent repeats is shown, with each repeat comprising six replicates. Error bars represent standard deviation.

On that side facing the N-domain, an 8 × 6 Å-wide and 15 Å-deep pocket lined by the α8, α9, α11, α12, α13, and α14 helices exists. Such pockets (termed henceforth the “HDOD pocket”) are characteristic of HDOD domains, which, in some cases, form the site for the binding of ions and possibly for small molecules. This is the case for PDB entry 3HC1 “crystal structure of HDOD domain protein with unknown function (NP_953345.1) from Geobacter sulfurreducens” (Fig. 7B and Supplementary Fig. 4), where two iron ions are bound at the deepest end of the pocket. In this structure, the ions are directly coordinated by five histidine residues and one aspartate (found in the α8, α9, α11, and α13 helices). In the case of SadB, however, only one histidine faces the HDOD pocket (i.e., the α9 helix of H326), which makes it unlikely that SadB relies on similar anion interactions. Moreover, the SadB pocket is mostly occluded by two loops, the loop that connects the N- and C-domains (comprising residues 154–159) and the α14-α15 loop (comprising residues 424–427).

SadB adaptor activity that regulates biofilm formation does not require ligand binding to the HDOD pocket

Despite the fundamental structural differences of the HDOD pocket between SadB and the YbaK protein from H. influenzae presented in Fig. 7B and Supplementary Fig. 4, we cannot completely rule out the possibility of ligand binding to the SadB HDOD pocket. We, therefore, introduced a series of mutations at various SadB sites, particularly in the HDOD pocket, that could compromise putative ligand binding (Fig. 7A and Supplementary Fig. 4). Since point mutations may only have a minor effect on SadB behavior, we used a hyper-biofilm-forming strain (Δorn)35 as genetic background for our biofilm assay, thereby increasing sensitivity of our measurements. We found that none of the introduced mutations had a significant effect on SadB involvement in biofilm formation (Fig. 7D), with the exclusion of drastic truncation of either the N- or C-domain (Fig. 7E). Finally, a Biacore assay, using purified SadB with different concentrations of c-di-GMP corroborated the lack of binding (Supplementary Fig. 5). This strongly suggests that biofilm modulation by SadB does not require ligand binding to the HDOD pocket, despite both the N- of C-domains being necessary.

Discussion

SadB was discovered in the early 2000s and was presumed to play a role in the Gac/Rsm signaling pathway, mediating the transition from reversible to irreversible surface attachment18,36,37. Recent studies showed that a strain carrying a sadB mutation shows dramatically reduced biofilm formation, even when present in hyper-biofilm-forming mutants19. Furthermore, the sadB mutant exhibits a unique hyper-swarming motility phenotype20. Since both SadB-related phenotypes correspond with low c-di-GMP levels, SadB was assumed to be a c-di-GMP-dependent protein. It was also shown that a sadB mutant produced noticeably less extracellular matrix material than the WT20. SadB expression levels seem to correlate with P. aeruginosa commitment to irreversible attachment and are controlled by the RpoN and by the flagellar biosynthesis regulator, FleR20,29. Nonetheless, despite the obvious centrality of SadB, its function in P. aeruginosa and how it mediates the various phenotypes related to its presence remained unknown. The current study demonstrated that all ∆sadB-related phenotypes are directly linked to the effect of SadB on AmrZ, a major transcription factor affecting biofilm formation, swarming motility and polysaccharide production28,30,31,38.

We have shown here that SadB directly binds AmrZ and that even undetectable amounts of SadB are sufficient to dramatically reduce AmrZ levels. The binding of SadB to AmrZ occurs through three amino acids within the C-terminus conserved region and triggers AmrZ degradation via non-specific proteolysis, mainly by the housekeeping protease Lon. It was previously shown that AmrZ down-regulated PSL production31. Mutants in which PSL formation is reduced form a very thin, non-mushroom-like biofilm, similar to that formed by the sadB mutant. It appears that the low c-di-GMP levels in the sadB mutant can also be directly linked to the effect of SadB on AmrZ. Diguanylate cyclase (DGCs) such as GcbA and SiaD which are responsible for c-di-GMP synthesis are down-regulated by AmrZ28,29. In addition, it was previously shown that the Lon proteases can detect and degrade misfolded proteins by recognizing exposed hydrophobic residues which are generally buried within the hydrophobic core upon proper folding39. Alternatively, the Lon proteases can be directed with the help of adaptor proteins40. In Bacillus subtilis, the Lon protease affects biofilm formation and motility by specifically degrading SwrA, a flagellar biosynthesis regulator. This specific degradation is possible only with the help of SmiA, an adaptor protein. Furthermore, this specific proteolysis seems to be surface-dependent, in that when the bacteria sense a solid surface, such proteolysis stops, and SwrA levels rises40. The role of SadB in mediating the transition to irreversible attachment leads us to hypothesize that SadB functions in a similar manner to the B. subtilis adaptor to promote AmrZ degradation via Lon and other proteases.

Recent studies in Pseudomonas fluorescens revealed that SadB can bind c-di-GMP41. To assess whether SadB requires ligand binding for its activity, we first solved its crystal structure, which revealed two domains (i.e., the N- and C-domains) and a HDOD pocket that likely provides a metal-binding site. However, the HDOD pocket is mostly occluded by two loops. Furthermore, only one histidine faces the HDOD pocket instead of five, as seen in HDOD pockets in other proteins. Taking these two structural characteristics into consideration, it is highly unlikely that the HDOD pocket of SadB is capable of ligand binding. Nevertheless, by introducing a series of mutations (mainly in the HDOD pocket) that would compromise any ligand binding to SadB and finding that none of them had any effect on biofilm formation, we concluded that ligand binding to SadB is not necessary for its role in biofilm modulation.

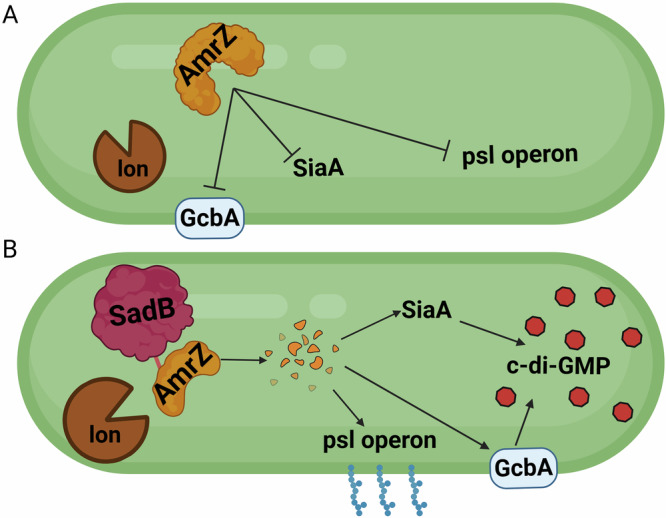

In conclusion, we have shown that SadB’s presumed role in mediating the transition from reversible to irreversible surface attachment is directly linked to AmrZ. When AmrZ is present in the cell, bacteria are more suited for a planktonic mode of growth, as expression of both PSL and the major DGCs is repressed. We hypothesized that upon surface contact, SadB (which is barely detectable in planktonic stage cultures) will start to accumulate, and in turn directly binds AmrZ at a specific stretch adjacent to the C-terminus. SadB acts as an adaptor protein, directing AmrZ to proteolysis, mainly by the housekeeping protease Lon. When AmrZ levels start to decrease, PSL biosynthesis begins31, with PSL being a crucial polysaccharide in the early stages of biofilm formation42. In addition, levels of DGCs, such as AdcA (GcbA) and SiaD, which are repressed by AmrZ, begin to rise28,29. At this point, the accumulation of PSL and c-di-GMP causes P. aeruginosa to transition from a planktonic/reversibly attached state to a biofilm-committed state (Fig. 8). This is a rapid process, allowing P. aeruginosa to quickly adapt to its surroundings. Further study is required to clarify the mechanisms by which surface sensing regulates SadB.

Fig. 8. Scheme summarizing SadB effect on P. aeruginosa.

A Inactive/absent SadB allows AmrZ to accumulate in the cell leading to repression of biofilm formation. B Higher levels of SadB mark AmrZ for degradation inducing c-di-GMP accumulation, PSL production and subsequent biofilm formation.

Methods

Bacterial strains, plasmids and growth conditions

Strains and plasmids used in this study are listed in Supplementary Table 2. P. aeruginosa strains were inoculated into Luria-Bertani medium (LB, Difco) and incubated at 37 °C with agitation, unless otherwise indicated. Agar (1.5%; BA, Difco) was added to prepare solid media. Antibiotics were added to the growth media if necessary for selection. For P. aeruginosa, 300 μg/ml carbenicillin (Carb) and 100 μg/ml gentamicin (Gm) were added, whereas for Escherichia coli, 100 μg/ml ampicillin (Amp), 20 μg/ml gentamicin (Gm) and 34 µg/mL chloramphenicol (Cm) were added. Vogel Bonner minimal mMedium (VBMM), Pseudomonas isolation agar (PIA; Difco) and no-salt Luria-Bertani (NSLB) containing 10% sucrose were used for creating P. aeruginosa deletion strains.

Plasmid construction and cloning

For P. aeruginosa gene product over-expression, primers (Supplementary Table 3) were designed to complement the beginning and end of each gene, with the addition of enzyme restriction sites. For insert amplification, Phusion High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (Thermo) was used. Amplified products were purified using NucleoSpin Gel and PCR Clean-up (MACHEREY-NAGEL). FastDigest restriction enzymes (Thermo Scientific) were used for digestion of amplified DNA and plasmids. Ligation was carried out using BIOGASE – fast ligation kit (Bio-Lab). All processes were conducted according to the manufacturers’ instructions. Ligated plasmids were then introduced into an E. coli DH5α (NEB5α) (Invitrogen) competent strain by heat shock for cloning, followed by plating on selective medium. Successful plasmid transformations were verified using a DNA Polymerase ReddyMix PCR Kit and universal primers. For plasmid extraction, a QIAprep Spin Miniprep Kit (Qiagen) was used. Following sequence verification, plasmids were inserted into relevant P. aeruginosa strains by electroporation.

Deletion mutation

Gene deletion was performed by homologous recombination. Plasmids were constructed by gateway cloning or Gibson assembly. First, two segments 500 bp in length upstream and downstream of the gene to be deleted were amplified using PCR. After the fragments were cleaned, the two sections were fused by SOEing (splicing by overlap extension) PCR. The new fragment was cloned to the pDONRPEX18Gm plasmid using homologous recombination and BP clonase (Invitrogen) enzyme. The plasmid was introduced into the E. coli DH5α competent strain by heat shock transformation, followed by plating on selective medium. After sequence verification, the plasmid was inserted into the E. coli S17 strain (donor) by electroporation.

For conjugation, the S17 donor strain and the PAO1 acceptor strains were grown separately in LB medium overnight at 37 °C. The acceptor strain was then diluted (1:2) into 6 ml LB medium and grown for an additional 3 h at 42 °C without agitation. The donor strains were diluted 1:20 into 6 ml and grown for an additional 3 h at 37 °C with agitation. Following incubation, 500 µl of the acceptor strain and 3 ml of the donor strain were transferred onto Durapore membrane filters (0.45 μm HV, Millipore). The membrane containing the strains was transferred onto LB agar plate (with no selection) and incubated overnight at 30 °C. Strains were then scraped off the membrane, suspended in phosphate-buffered saline (PBSX1, Sigma) and plated on VBMM plates containing 100 µg/ml Gm and incubated at 37 °C for 24–48 h for selection. The strains were streaked on NSLB plates containing 10% sucrose and incubated at 30 °C for 24 h. Colonies were then plated on LB, PIA and LB containing 100 μg/ml Gm. Finally, PCR was carried out to verify mutant colonies that did not grow on LB plates containing Gm.

Codon optimization

The identification of rare codons and codon optimization sequence were scored through the ATGme database43.

Static biofilm assay

Strains were inoculated from a −80 °C stock onto LB agar plates and grown overnight. The next day, the bacteria were scraped from the plate into 500 µl PBSX1. The bacteria were then diluted to OD595nm = 0.05 in 1 ml BM2 + CA define growth media and distributed into a 96-well microtiter plate and incubated overnight at 37 °C. The following day, planktonic bacteria were washed out and the wells were filled with 150 µl crystal violet (Sigma) and stained for 15 min at room temperature. Crystal violet that did not attach to the biofilm was rinsed out, while the attached dye was solubilized by adding 200 µl of absolute ethanol and incubating at room temperature for 15 min. Solubilized dye (100 µl) was transferred from each well to a new 96-well plate. The OD595nm of each well was measured using a Synergy 4 Multi-Detection Microplate Reader (BioTek).

Swarming assay

Strains were inoculated from a −80 °C stock into 2 ml LB and grown overnight. The next day, the bacteria were diluted 1:10 in M9 + casamino acids (CA). Following an incubation of ~3 h, 2.5 µl of bacteria was plated in the middle of an M9 agar (0.5%) plate. The plates were then incubated for 24 h. Pictures were taken using the Molecular Imager Gel Doc XR System (Bio-Rad).

Flow cell assay

Strains were inoculated from a −80 °C stock into 2 ml Tryptic soy broth (TSB) and grown overnight. The next day, the bacteria were diluted to OD595nm 0.05 in 1% TSB and loaded onto µ-Slide I0.4 Luer uncoated slides (ibidi). The 1µ-Slide was connected to a flow cell containing fresh 1% TSB. Fresh media was pumped into the 1µ-Slide at a rate of 10 ml/h and the waste was flushed out. Bacteria were grown in the 1µ-Slide for 24–48 h at 37 °C. Following incubation, pictures were taken using SP8 confocal HyD microscope (Leica).

RNA extraction

Strains were inoculated from a −80 °C stock into 2 ml LB and grown overnight. The bacteria were then diluted 1:100 into 15 ml M9 + CA and incubated for ~3 h (OD595nm 0.5). Following incubation, a 2 ml aliquot was taken and mixed with 4 ml RNAprotect Bacteria Reagent (Qiagen) and allowed to rest for 20 min. The bacteria were then centrifuged at 3220 × g for 20 min and rinsed in Tris-EDTA buffer solution (PH 8, Sigma/Fluka) to remove residual RNAprotect. Lysozyme (90 μg/ml; Roche), 10 μl proteinase K (Qiagen) and 1 ml warm tri-reagent (65 °C, Sigma) were added to the pelleted cells. After incubating for 5 min at 65 °C, 200 μl of chloroform (BIO LAB) were added. The solution was then centrifuged for 15 min at 20,817 × g and the upper liquid phase was transferred into 80% ethanol. RNA was extracted from this fraction using a RNeasy Mini Kit according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Qiagen).

Real-time PCR analysis

GoScriptTM Reverse Transcription System (Promega) was used with 1 μg RNA according to the manufacturer’s instructions to create cDNA. Fast SYBR Green Master Mix (Life Technologies) was used for the real-time PCR analysis, using primers synthesized by IDT, according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Real-time PCR was conducted using the CFX-96 TouchT Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad). Results were normalized using PA3297 as housekeeping gene.

Protein extraction

Strains were inoculated from a −80 °C stock into 2 ml LB and grown overnight. The bacteria were diluted 1:100 in 15 ml M9 + CA with 33.3 µM L-(+)-arabinose (when protein over-expression was required) (Alfa Aesar). Following an incubation of ~3 h (OD595nm 0.5), 1.5*109 bacteria was taken from each strain, centrifuged at 14,000 × g for 2 min, and the supernatant was removed. The cell pellet was re-suspended in lysis buffer (100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5) containing Benzonase Endonuclease (Millipore), cOmplete protease inhibitor cocktail (Roche), and lysozyme (Sigma-Aldrich). Aliquots were then incubated for 10 min at 30 °C with agitation followed by Sonication (90 s, ON 5 s, OFF 5 s, 37% amplitude). The sonicated samples were centrifuged at 20,817 × g for 10 min, and the upper liquid phase containing the proteins was collected.

Western blot analysis

Total protein concentration was metered using NanoDrop Microvolume Spectrophotometers and normalized to 2.5 mg/ml. Protein samples were diluted 3:1 with sample bufferX3 (150 mM Tris-HCl, pH 6.8, 3% β-mercaptoethanol, 6% sodium dodecyl Sulfate, 0.3% nromophenol blue, 30% glycerol), and incubated at 95 °C for 10 min. The proteins were then separated on a 4–20% Tris-glycine gel and transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane. After blocking with 1% alkali-soluble casein in TBS (pH 7.5) for His-tagged proteins or 5% skim milk in TBS (pH 8) for FLAG-tagged proteins overnight at 4 °C, the membrane was incubated for 1 h with anti-His antibodies (1:1000, Merck) or anti-FLAG antibodies (1:2500, Sigma-Aldrich). Following three washes with TBST, the membrane was incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated goat anti-mouse antibodies (1:2500, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) for an hour. After an additional three TBST washes, the membrane was developed with an ECL kit.

Proteomics analysis

Following protein extraction, protein levels were measured and analyzed by mass spectrometry at Weizmann Institute of Science (Rehovot, Israel). The samples were digested with trypsin using the S-trap method. The resulting peptides were analyzed using nanoflow liquid chromatography (nanoAcquity) followed by high resolution, high mass accuracy mass spectrometry (Fusion Lumos). Each sample was analyzed on the instrument in the discovery mode separately in a random order. Raw data were processed with MaxQuant v1.6.6.0 software. The data was searched with the Andromeda search engine against the P. aeruginosa database (http://www.pseudomonas.com44). Quantification was based on the LFQ method, based on unique peptides.

Transcriptomics analysis

Following RNA extraction, RNA quality was evaluated via a Tape station RNA assay (Agilent Technologies). Libraries were constructed with aScriptSeq Complete Kit –Bacteria (Epicentre) using the manufacturer’s instructions. Finally, quality was evaluated by a Tape station HS DNA assay (Agilent Technologies). Equimolar pooling of libraries was performed based on Qubit values and sequenced at the Weizmann Institute of Science. A strand-specific, single end RNA-seq protocol was used, yielding about 15–22 million reads per sample. Reads were aligned to the P. aeruginosa PA01 RefSeq genome (NC_002516) using bowtie2 aligner software (v2.3.2)45,46. HTSeq (v 0.6.1) was used to determine raw read counts for 5584 annotated coding sequences, and 63 tRNA and 37 ncRNA sequences. The annotation file for P. aeruginosa PAO1, in GTF format, was downloaded from http://www.pseudomonas.com44. Differentially expressed genes were determined with the R Bioconductor package DESeq247. P values were corrected with the Benjamini-Hochberg FDR procedure. Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient was used to compare RNA-seq results with mass spectrometry results.

Cellular nucleotide measurements

Strains were inoculated from a −80 °C stock onto LB plates and grown overnight. The bacteria were then scraped and suspended in 500 µl M9 + CA. The bacteria were then diluted 1:100 in 25 ml M9 + CA. Following incubation of approximately 3 h (OD595nm 0.5), 5 ml of culture were transferred into a 15 ml tube and centrifuged for 10 min at 3,220 g. Cultures (1 ml) were harvested to determine protein content by Bradford assay and 200 μl aliqouts were harvested for viability counting. Cell pellets were re-suspended in 300 μL of extraction solvent (40% methanol, 40% acetonitrile, 20% DDW) with cXMP at a final concentration of 266.7 ng/ml (Sigma-Aldrich), incubated for 15 min at 4 °C, followed by 10 min of incubation at 95 °C and centrifugation at 20,817 × g for 5 min at 4 °C. The supernatant was transferred to a new tube. The extraction of the resulting pellets, including resuspension and incubation at 4 °C, was repeated twice more with 200 μL of extraction solvent (without cXMP). Each time, the supernatant was transferred to the same tube, for a total yield of 700 μl of final extract. The supernatant was evaporated until dry at 40 °C under a gentle stream of nitrogen gas. c-di-GMP levels were measured via Reversed-Phase LC-MS/MS at the Medizinische Hochschule Hannover Medical School (Hannover, Germany). Measurements were normalized according to protein levels.

Identification of protein–protein interactions

Anti-His tag antibodies (10 μg; Novagen) were used to coat 0.5 mg of Dynabeads M-280 tosyl-activated magnetic beads (Thermo-Fisher) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Conjugated beads were mixed with cell lysate from the protein extraction and incubated overnight at 4 °C with rotation. Following two washes with lysis buffer, biotinylated anti-FLAG antibodies (1:500; GenScript) were added to the complex of magnetic beads and proteins and incubated for 30 min at room temperature. After an additional wash with lysis buffer, the complex was incubated with streptavidin-RPE (1:500) (Jackson Immuno Research Laboratories) for 20 min. Subsequently, the buffer was replaced, and the complexed beads were subjected to analysis using the MMB system, as described previously 33. Three measurements of each sample were performed. Three independent experiments were averaged. All measurements were normalized to the signal of the conjugated magnetic beads alone. Normalized fluorescence signal values are presented as the mean ± SEM. A one-way ANOVA statistical analysis was performed, followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparison tests.

Co-Immunoprecipitation with anti-FLAG resin

Cell lysate (200 μl) was added to anti-FLAG M2 affinity gel (Sigma-Aldrich) and lysis buffer was added to a final volume of 1 ml, followed by incubation for 2 h at 4 °C wtih rotation. The cell lysate and resin mix were centrifuged at 5000 × g for 30 s, and the supernatant was removed. The mix was then washed five times with 500 μl of lysis buffer (100 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5). 3X FLAG peptide (Sigma-Aldrich) solution (100 μl; 150 ng/μl final concentration in lysis buffer) was added to the mix and incubated with gentle shaking for 30 min at 4 °C. The mix was then centrifuged at 5000 × g for 30 s, and the supernatant was collected. Finally, protein presence was tested via western blot.

Degradation assay

Strains were inoculated from a −80 °C stock into 2 ml LB and grown overnight. The bacteria were then diluted 1:100 in 15 ml M9 + CA. Following incubation of approximately 3 h (OD595nm 0.5), 33.3 µM L-(+)-arabinose was added and 5*108 cells were taken and centrifuged at 16,873 × g for 3 min. The supernatant was discarded and the pellet was suspended in SBX1 (time = 0). This step was repeated at different time points to follow the degradation process. Finally, protein levels were assessed by western blot.

Cell lysate pull-down assay

Following protein extraction, the sample was diluted 1:1 in pull-down buffer (6.5 mM NaPO4, pH 7.4, 140 mM NaCl, 0.02% Tween-20). The sample was added to 50 µL of Dynabeads (Sigma) and incubated with gentle shaking for 2 h at 4 °C. The tube was then placed on a magnet for 2 min and the supernatant was discarded. The Dynabeads were then washed 5 times with 500 μl binding/wash (100 mM NaPO4, pH 8, 600 mM NaCl, 0.02% Tween-20). Lastly, the bound proteins were eluted using His elution buffer (300 mM imidazole; 50 mM NaPO4, pH 8, 300 mM NaCl, 0.01% Tween-20). Protein presence was then measured and analyzed by mass spectrometry at the Weizmann Institute of Science.

SadB purification

For preparative purification, SadB was expressed in the T7 Express E. coli strain (NEB), also containing the RIL Codon Plus plasmid48. Transformed E. coli cells were grown for 3–4 h at 37 °C in 2xYT media. After the culture reached OD600nm 0.4, the temperature was reduced to 16 °C. When the culture growth reached OD600nm 0.6, protein expression was induced with 200 µM IPTG over a 16 h period. Cells were harvested and frozen prior to lysis and centrifugation. SadB was purified as described49. Briefly, cells were suspended at a 1:10 (w:v) ratio with lysis buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 10% glycerol, 5 mM β-mercaptoethanol (βME), 0.1% Triton X-100) and lysed using a microfluidizer (Microfluidics). The cell debris were removed by 20 min centrifugation (10,000 × g) at 4 °C, and the supernatant was then loaded onto a pre-equilibrated Ni-chelated column (HisTrap, GE Healthcare) with binding buffer (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 5 mM βME). The column was washed and eluted using an elution buffer gradient (50 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 300 mM NaCl, 5% glycerol, 500 mM imidazole, 5 mM βME). An in vitro Lysine methylation protocol50 was applied. SadB-containing fractions were diluted at 1:50 (v:v) in buffer containing 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mM βME and loaded on an pre- equilibrated anion exchange monoQ column (GE Healthcare). The protein was eluted with a gradient of 25 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 5 mM BME and 1 M NaCl. SadB-containing fractions were then diluted to 1 mg/ml with monoQ loading buffer for lysine methylation. First, 40 µl of 1 M dimethylamine-borane complex (ABC; Sigma-Aldrich) and 20 µl of 1 M formaldehyde (Sigma-Aldrich) were added per ml of protein solution (both reagents were diluted with DDW) and incubated for 2 h on ice. This step was repeated twice, followed by the addition of 10 µl ABC per ml of solution, and incubation overnight at 4 °C. The following day, the reaction was stopped by adding glycine (final concentration of 13.3 mM) and DTT (final concentration of 5 mM) to reverse any modification of cysteine or methionine residues. The entire solution was then centrifuged (15,000 × g for 15 min), concentrated, and loaded onto a size-exclusion chromatography column (HiLoad 26/60 Superdex 200, GE Healthcare) pre-equilibrated with buffer containing 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.5, 150 mM NaCl, 1 mM DTT. SadB-containing fractions were pooled, concentrated to 16 mg/ml, split into aliquots, flash-frozen in liquid N2 and stored at −80 °C.

SadB crystallography

Methylated SadB was screened for crystal growth conditions with the Crystal screen, PegRX, PEG/Ion, and SaltRX commercial crystallization screens (Hampton Research) at 277 K and 293 K in 96-well hanging-drop clear polystyrene microplates (TTP LabTech) using the mosquito robot for crystallography (TTP LabTech), as described49. A 1:1 sample:reservoir ratio was used with a drop size of 0.2 µl. Optimal crystal growth conditions consisted of a reservoir content of 1 M ammonium citrate tribasic, pH 7, and 0.1 M Bis-Tris propane, pH 7.25. Crystals were gradually introduced into a cryo-protectant solution consisting of 1.1 M ammonium citrate tribasic, pH 7, 0.1 M Bis-Tris propane, pH 7 and 8% glycerol that was added to the mother-liquor, and flash-frozen in liquid N2. Diffraction data were measured at 100 K on the ID30-B beamline51 at the ESRF and were processed and scaled using the XDSAPP software package52.

Crystals belonging to the P212121 space group, with unit cell dimensions of a = 111.939, b = 161.892, c = 235.173, α = γ = β = 90, have four molecules in the asymmetric unit, and a solvent content of 51%. The crystals diffracted to a maximal resolution of 2.9 Å. The crystal structure was solved by molecular replacement using Phaser-MR53 with the putative signal transduction protein (Maqu_0641) from Marinobacter aquaeolei VT8 (PDB 3MEM) that shares 46% sequence identity with P. aeruginosa SadB as the search model. Molecular replacement was followed by electron density modification procedures and cycles of model refinement and re-building using COOT54, PHENIX refine55, and the ReDo server56. The quality of the resulting electron density ensured correct assignment of all amino acid side chains (Supplementary Table 4).

Supplementary information

Acknowledgements

Funding for this project was provided by grants from the Israel Science Foundation (1694/22 and 1125/17) to E.B.

Author contributions

Y.B.D.: Conceived, designed, and performed experiments. Analyzed the data and interpreted the results. Wrote the original draft. M.S.: Conceived, designed, and performed the crystallography. Y.B.: Performed the experiments. B.P.: Performed the experiments. S.R.: Designed and performed experiments. I.Z.: Performed the experiments. M.N.: Performed the experiments. S.S.: Reviewed and edited the manuscript. O.Y.: Performed the experiments. S.K.L.: Performed the experiments. I.L.L.: Analyzed the data. A.D.: Provided materials. Y.O.: Provided materials, analyzed the data, and wrote the original draft. E.B.: Provided materials, reviewed and edited the manuscript, and supervised the project.

Data availability

The raw data can be accessed on Figshare. https://figshare.com/s/16241374193d8aabc627?file=49191181. Accession numbers Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession number 9QZK.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41522-025-00710-0.

References

- 1.Hsueh, P. R. et al. Persistence of a multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa clone in an intensive care burn unit. J. Clin. Microbiol36, 1347–1351 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aloush, V., Navon-venezia, S., Seigman-igra, Y., Cabili, S. & Carmeli, Y. Multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa: risk factors and clinical impact. Society50, 43–48 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kwon, S., Schweizer, M. L. & Perencevich, E. N. National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Disease (NIAID) funding for studies of hospital-associated bacterial pathogens: are funds proportionate to burden of disease?. Antimicrob. Resist Infect. Control1, 5 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hirsch, E. B. & Tam, V. H. Impact of multidrug-resistant Pseudomonas aeruginosa infection on patient outcomes. Expert Rev. Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res.10, 1–18 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hill, D. et al. Antibiotic susceptibility of Pseudomonas aeruginosa isolates derived from patients with cystic fibrosis under aerobic, anaerobic, and biofilm conditions. J. Clin. Microbiol43, 5085–5090 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bjarnsholt, T. The role of bacterial biofilms in chronic infections. APMIS Suppl.10.1111/apm.12099. (2013). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Moreau-Marquis, S., Stanton, B. & O’Toole, G. Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation in the cystic fibrosis airway. Pulm. Pharmacol. Ther.21, 595–599 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wozniak, D. J. & Mann, E. E. Pseudomonas biofilm matrix composition and niche biology. FEMS. Microbiol. Rev.33, 395–401 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mikkelsen, H., Sivaneson, M. & Filloux, A. Key two-component regulatory systems that control biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ. Microbiol.13, 1666–1681 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schurr, M. J. Which bacterial biofilm exopolysaccharide is preferred, psl or alginate?. J. Bacteriol.195, 1623–1626 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Valentini, M. & Filloux, A. Biofilms and cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) signaling: lessons from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and other bacteria. J. Biol. Chem.291, 12547–12555 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merritt, J. udithH. et al. Specific control of Pseudomonas aeruginosa surface-associated behaviors by two c-di-GMP diguanylate cyclases. mBio1, 1–9 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Petrova, O. E., Cherny, K. E. & Sauer, K. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa diguanylate cyclase GcbA, a homolog of P. Fluorescens GcbA, promotes initial attachment to surfaces, but not biofilm formation, via regulation of motility. J. Bacteriol.196, 2827–2841 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ha, D.-G. & O’Toole, G. A. c-di-GMP and its effects on biofilm formation and dispersion: a Pseudomonas aeruginosa review. Microbiol. Spectr.3, MB-0003-2014 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Park, S. & Sauer, K. Controlling Biofilm Development Through Cyclic di-GMP Signaling. in Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology Vol. 1386, 69–94 (Springer, 2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Hickman, J. W., Tifrea, D. F. & Harwood, C. S. A chemosensory system that regulates biofilm formation through modulation of cyclic diguanylate levels. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA102, 14422–14427 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Borlee, B. R. et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa uses a cyclic-di-GMP-regulated adhesin to reinforce the biofilm extracellular matrix. Mol. Microbiol.75, 827–842 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moscoso, J. A. et al. The diguanylate cyclase SadC is a central player in Gac/Rsm-mediated biofilm formation in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol.196, 4081–4088 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Caiazza, N. ickyC. & O’Toole, G. eorgeA. SadB is required for the transition from reversible to irreversible attachment during biofilm formation by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol.186, 4476–4485 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 20.Caiazza, N. C., Merritt, J. H., Brothers, K. M. & O’Toole, G. A. Inverse regulation of biofilm formation and swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol.189, 3603–3612 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Merritt, J. H., Brothers, K. M., Kuchma, S. L. & O’Toole, G. A. SadC reciprocally influences biofilm formation and swarming motility via modulation of exopolysaccharide production and flagellar function. J. Bacteriol.189, 8154–8164 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kuchma, S. L. et al. BifA, a cyclic-di-GMP phosphodiesterase, inversely regulates biofilm formation and swarming motility by Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. J. Bacteriol.189, 8165–8178 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baynham, P. J., Ramsey, D. M., Gvozdyev, B. V., Cordonnier, E. M. & Wozniak, D. J. The Pseudomonas aeruginosa ribbon-helix-helix DNA-binding protein AlgZ (AmrZ) controls twitching motility and biogenesis of type IV Pili. J. Bacteriol.188, 132 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Paris, Z., Fleming, I. M. C. & Alfonzo, J. D. Determinants of tRNA editing and modification: avoiding conundrums, affecting function. Semin. Cell Dev. Biol. 23, 269–274 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 25.García-Contreras, R., Zhang, X. S., Kim, Y. & Wood, T. K. Protein translation and cell death: The role of rare tRNAs in biofilm formation and in activating dormant phage killer genes. PLoS ONE3, e2394 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Muriel, C. et al. AmrZ is a major determinant of c-di-GMP levels in Pseudomonas fluorescens F113. Sci. Rep.8, 1–10 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pryor, E. E. et al. The transcription factor AmrZ utilizes multiple DNA binding modes to recognize activator and repressor sequences of Pseudomonas aeruginosa virulence genes. PLoS Pathog.8, e1002648 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Jones, C. J. et al. ChIP-seq and RNA-seq reveal an AmrZ-mediated mechanism for cyclic di-GMP synthesis and biofilm development by Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS Pathog.10, e1003984 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Oladosu, V. I., Park, S. & Sauer, K. Flip the switch: the role of FleQ in modulating the transition between the free-living and sessile mode of growth in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. J. Bacteriol.206, e0036523 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Hou, L., Debru, A., Chen, Q., Bao, Q. & Li, K. AmrZ regulates swarming motility through cyclic di-GMP-dependent motility inhibition and controlling Pel polysaccharide production in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. Front Microbiol. 10, 1847 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jones, C. J., Ryder, C. R., Mann, E. E. & Wozniak, D. J. AmrZ modulates pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm architecture by directly repressing transcription of the psl operon. J. Bacteriol.195, 1637–1644 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Feng, Q. et al. Regulation of Exopolysaccharide Production by ProE, a Cyclic-Di-GMP Phosphodiesterase in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Front Microbiol.11, 1–18 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Roth, S. et al. Identification of protein-protein interactions using a magnetic modulation biosensing system. Sens Actuators B Chem.303, 127228 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhang, H. et al. Crystal structure of YbaK protein from Haemophilus influenzae (HI1434) at 1.8 A resolution: functional implications. Proteins: Struct., Funct., Genet.40, 86–97 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ghosh, S. & Deutscher, M. P. Oligoribonuclease is an essential component of the mRNA decay pathway. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA96, 4372–4377 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martínez-Granero, F. et al. The Gac-Rsm and SadB signal transduction pathways converge on AlgU to downregulate motility in Pseudomonas fluorescens. PLoS ONE7, e31765 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 37.Lapouge, K., Schubert, M., Allain, F. H. T. & Haas, D. Gac/Rsm signal transduction pathway of γ-proteobacteria: From RNA recognition to regulation of social behaviour. Mol. Microbiol.67, 241–253 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Martínez-Granero, F., Redondo-Nieto, M., Vesga, P., Martín, M. & Rivilla, R. AmrZ is a global transcriptional regulator implicated in iron uptake and environmental adaption in P. fluorescens F113. BMC Genomics15, 237 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gur, E. & Sauer, R. T. Recognition of misfolded proteins by Lon, a AAA+ protease. Genes Dev.22, 2267–2277 (2008). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mukherjee, S. et al. Adaptor-mediated Lon proteolysis restricts Bacillus subtilis hyper flagellation. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA112, 250–255 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Muriel, C. et al. The diguanylate cyclase AdrA regulates flagellar biosynthesis in Pseudomonas fluorescens F113 through SadB. Sci. Rep.9, 1–9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ryder, C., Byrd, M. & Wozniak, D. J. Role of polysaccharides in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm development. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 10, 644–648 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Daniel, E. et al. ATGme: Open-source web application for rare codon identification and custom DNA sequence optimization. BMC Bioinforma.16, 303 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Winsor, G. L. et al. Enhanced annotations and features for comparing thousands of Pseudomonas genomes in the Pseudomonas genome database. Nucleic Acids Res.44, D646–D653 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Anders, S., Pyl, P. T. & Huber, W. HTSeq-A Python framework to work with high-throughput sequencing data. Bioinformatics31, 166–169 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods9, 357–359 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Love, M. I., Huber, W. & Anders, S. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol.15, 1–21 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Barak, R. & Opatowsky, Y. Expression, derivatization, crystallization and experimental phasing of an extracellular segment of the human Robo1 receptor. Acta Crystallogr Sect. F. Struct. Biol. Cryst. Commun.69, 771–775 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Sporny, M. et al. Structural history of human SRGAP2 proteins. Mol. Biol. Evol.34, 1463–1478 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Walter, T. S. et al. Lysine methylation as a routine rescue strategy for protein crystallization. Structure14, 1617–1622 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Mueller-Dieckmann, C. et al. The status of the macromolecular crystallography beamlines at the European Synchrotron Radiation Facility. Eur. Phys. J.130, 70 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Krug, M., Weiss, M. S., Heinemann, U. & Mueller, U. XDSAPP: a graphical user interface for the convenient processing of diffraction data using XDS. J. Appl Crystallogr45, 568–572 (2012). [Google Scholar]

- 53.McCoy, A. J. et al. Phaser crystallographic software. J. Appl Crystallogr40, 658–674 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Emsley, P., Lohkamp, B., Scott, W. G. & Cowtan, K. Features and development of Coot. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr66, 486–501 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Afonine, P. V. et al. Towards automated crystallographic structure refinement with phenix.refine. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr68, 352–367 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Joosten, R. P., Joosten, K., Murshudov, G. N. & Perrakis, A. PDB_REDO: constructive validation, more than just looking for errors. Acta Crystallogr D. Biol. Crystallogr68, 484–496 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The raw data can be accessed on Figshare. https://figshare.com/s/16241374193d8aabc627?file=49191181. Accession numbers Coordinates and structure factors have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession number 9QZK.