Abstract

Postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMOP) is a condition in women caused by estrogen deficiency, characterized by reduced bone mass and increased fracture risk. Fatty acid-binding protein 4 (FABP4), a lipid-binding protein involved in metabolism and inflammation, has emerged as a key regulator in metabolic disorders and bone resorption; however, its direct role in PMOP remains unclear. Here, we show that serum FABP4 levels in PMOP patients negatively correlate with bone mineral density, a trend also observed in ovariectomized mice. FABP4 promotes osteoclast formation and bone resorption without affecting osteoblast differentiation. The FABP4 inhibitor BMS309403 suppresses osteoclast differentiation by modulating calcium signaling and inhibiting the Ca2+-Calcineurin-NFATc1 pathway. Oral BMS309403 increases bone mineral density in ovariectomized mice, though less effectively than alendronate. Notably, bone-targeted delivery of BMS309403 achieves comparable efficacy to alendronate. In this work, we demonstrate that FABP4 is a critical mediator in PMOP and that its inhibition offers a promising therapeutic strategy.

Subject terms: Osteoporosis, Predictive markers, Drug delivery, Diagnostic markers

This study identifies FABP4 as driver of postmenopausal osteoporosis and shows that targeting FABP4 with a small-molecule inhibitor or bone-targeted nanoparticles can reduce bone loss and offers a potential new treatment approach.

Introduction

Osteoporosis (OP) is the most common bone disease in the elderly, characterized by diminished bone mass and increased susceptibility to fragility fractures1. It is a complex systemic metabolic disorder, with both primary and secondary forms2. Primary OP includes age-related OP and postmenopausal osteoporosis (PMOP)3, with approximately one-third of women and one-fifth of men over 50 are affected, particularly postmenopausal women4. With the aging global population, the incidence of PMOP is expected to rise significantly, posing a serious public health challenge5. Secondary OP, on the other hand, is often linked to conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis (RA)6, diabetes7, and glucocorticoid use8.

The fundamental pathogenesis of OP involves an imbalance in bone remodeling, where bone resorption surpasses bone formation, leading to decreased bone density and strength9. In PMOP, this imbalance is driven by reduced estrogen levels following menopause, which accelerates bone resorption10,11. In RA-related OP, inflammation factors and immune factors contribute to this imbalance12, while in diabetes-related OP, insulin resistance and changes in the bone marrow microenvironment may play significant roles7. Current treatments aim to restore this balance in bone modeling: some drugs promote bone formation (e.g., teriparatide13), while others inhibit bone resorption (e.g., bisphosphonate14,15 and denosumab16). However, these therapies are not universally effective and can cause side effects, such as musculoskeletal pain and osteonecrosis of the jaw with prolonged alendronate use17–19. Given that OP is a multifactorial disease with different underlying mechanisms in individual patients20, exploring novel pathogenic mechanisms and identifying biomarkers could improve early detection of high-risk patients and enable the development of more personalized treatment strategies.

Fatty Acid-Binding Protein 4 (FABP4) is a key lipid-binding protein predominantly found in adipocytes and macrophages, essential for lipid metabolism through the transport and binding of fatty acids21,22. Previous research has identified FABP4 as a promising target for metabolic disorders such as obesity, insulin resistance, and diabetes23. Recent studies have revealed its role in modulating inflammatory responses, with elevated levels of FABP4 correlating with inflammatory conditions such as arthritis24,25 and atherosclerosis26. In 2022, Cai et al.27 highlighted the exacerbating role of FABP4 from synovial M1 macrophages in RA. Interestingly, its supplementary data indicated that feeding recombinant FABP4 protein to collagen-induced arthritis mice for eight weeks significantly increased osteoclast (OCs) activity in the bone marrow. Subsequently, Cao et al.28 demonstrated that the absence of Kindlin-2 in mouse adipocytes led to a notable increase in overall bone mass by inhibiting FABP4 expression. Despite not being the primary focus, these studies indirectly suggested a potential association between FABP4 and OP.

To date, there is no direct research on the link between FABP4 and PMOP. Our study aims to investigate the impact of FABP4 on bone homeostasis and explore the potential of inhibiting FABP4 as a therapeutic approach for PMOP. As a key regulator of lipid metabolism and inflammation—both of which contributed to OP—FABP4’s role in PMOP could provide valuable insights into the mechanisms of bone loss. If FABP4 is confirmed to exacerbate PMOP, it may emerge as a critical target not only for PMOP but also for RA-related and diabetes-related OP. This could unify the pathophysiology of these conditions and pave the way for multi-targeted treatments. Targeting FABP4 may thus represent a promising strategy for improving bone health in a range of OP-related diseases, with significant implications for both prevention and therapy.

In this work, we observed a negative correlation between serum levels of FABP4 and bone mineral density (BMD) in PMOP patients. In vitro experiments confirmed that high FABP4 expression exacerbates OP by promoting bone resorption without affecting bone formation. Our findings indicated that FABP4 inhibitors BMS309403 (BMS) can mitigate OCs activation through the Ca2+-Calcineurin-NFATc signaling pathway. By utilizing bone targeting nanoparticles (NPs) for targeted delivery, we found that FABP4 inhibitor-loaded NPs exhibit comparable efficacy to alendronate sodium (ALD) in treating ovariectomized (OVX) mice. These findings highlight the pathological relevance of FABP4 in PMOP and support its potential as a therapeutic target.

Results

Patients’ BMD correlates negatively with their serum FABP4 levels

OVX in mice, which induced estrogen deficiency, is a well-known model for causing bone loss and increased marrow adiposity, effectively simulating PMOP. However, the expression of FABP4 in the bone marrow of OVX mice is limited reported. Our study revealed significant trabecular bone loss 30 days post-ovariectomy, as shown by micro-CT scans (Fig. 1a), and an increase in marrow adipose tissue, confirmed by paraffin sections and Hematoxylin and Eosin staining (H&E) (Fig. 1b, d). Immunohistochemistry (IHC) demonstrated a marked upregulation of FABP4 in the bone marrow cavity (Fig. 1c, e), suggesting changes in adipocyte function and possible effects on osteoblast activity.

Fig. 1. Increased FABP4 levels observed in the serum of PMOP patients and in the bone marrow of OVX mice.

a The OVX mice showed a marked decrease in trabecular bone mass. n = 6 mice per group. b H&E staining on paraffin-embedded tibial sections from OVX mice and Sham mice, with circular gaps representing dissolved adipose tissue. Scale bar, 300 μm and 100 μm. c IHC staining of FABP4 on tibial sections. Scale bar, 50 μm. d Quantification analysis of adipose tissue of (b). n = 4 mice in each group. e Quantification analysis of FABP4 expression of (c). n = 5 mice in each group. f Serum level of FABP4 was increased in PMOP patients and non-OP patients confirmed by ELISA assay. Data represent mean ± SEM; n = 8 for PMOP patients and n = 7 for non-OP patients. g Pearson correlation analysis between BMD and FABP4 in all clinical patients. All data is presented as mean ± SEM with p-values (d–f). Two-tailed unpaired t tests (d–f) and the two-tailed Pearson correlation coefficient (g) were calculated were performed. Source data are provided as Source Data file.

Subsequent investigations included measuring serum levels of FABP4 and lipid profiles (total cholesterol (TC), triglycerides (TG), HDL, and LDL) in patients with PMOP (T-scores ≤ −2.5) and non-OP (T-scores ≥ −1) trauma fracture patients (Supplementary Table 1). Our results showed that, among the lipid profile components, none of them were significantly abnormal in PMOP patients compared to non-OP individuals (Supplementary Fig. 1a), and serum FABP4 levels were notably higher in PMOP patients (Fig. 1f). Correlation analysis revealed a significant negative relationship between BMD and serum FABP4 levels (Fig. 1g, Supplementary Fig. 1b), indicating that higher FABP4 levels are associated with lower BMD. These findings provide compelling clinical evidence for FABP4’s role in PMOP development.

Fabp4 has no impact on the osteogenic differentiation of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells (BMSCs)

Both bone marrow adipocytes and osteoblasts originate from BMSCs29. An increase in bone marrow adiposity is associated with a decrease in bone mass30. Initially, we hypothesized that FABP4 might inhibit osteogenic differentiation by promoting BMSCs to differentiate into adipocytes. To test this, we supplemented recombinant human FABP4 protein (25 ng/mL or 50 ng/mL) during the 21-day induction of human BMSCs towards osteogenic differentiation, along with the concurrent addition of FABP4 protein and its inhibitor BMS (5 μM or 10 μM) (Fig. 2a). Surprisingly, Alizarin Red staining revealed that neither the FABP4 protein nor its inhibitor affected the osteogenic differentiation capacity of BMSCs (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2. Increased endogenous or exogenous FABP4 protein does not affect the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs.

a Full image of the effect of rmFABP4 (25 ng/mL or 50 ng/mL) or combined with FABP4 inhibitor BMS (5 μM or 10 μM) on BMSCs osteogenic differentiation, assessed by Alizarin Red staining. b Quantitative analysis of (a). n = 6 wells in 6-well-plate per group. c Representative bright-field and GFP images of FABP4 stably overexpressed BMSCs. Scale bar, 200 μm. At least three independent experiments were performed. d Western Blotting indicated the successful overexpression of FABP4 protein in FABP4 overexpressed BMSCs. Three independent experiments were performed. e q-PCR results showed a nearly 3600-fold increase in FABP4 expression in BMSCs. n = 3 independent samples per group. f Full image of the effect of FABP4 overexpressed BMSCs osteogenic differentiation by Alizarin Red staining. g Quantitative analysis of (f). n = 6 wells in 6-well-plate per group. All experiments were run in at least triplicate. All data is presented as mean ± SEM with p-values (b, e, g), ns = no significance. Two-tailed unpaired t test (e) and one-tailed Dunnett’s Multiple Comparison Test (b, g) were performed, and the p-values were adjusted made by multiple comparisons (b, g). Source data are provided as Source Data file.

This led us to consider whether increased bone marrow adiposity elevates endogenous FABP4 levels within BMSCs, thereby reducing their osteogenic differentiation potential. To investigate this, we established stable BMSC cell lines overexpressing FABP4 (Fig. 2c, d), achieving nearly a 4000-fold increase in FABP4 gene expression (Fig. 2e). However, when inducing osteogenic differentiation in these FABP4-overexpressing BMSCs, with or without BMS (10 μM), the Alizarin Red staining results remained unchanged, indicating that FABP4 overexpression did not impact the osteogenic differentiation of BMSCs (Fig. 2f, g).

These findings demonstrate that both endogenous and exogenously elevated levels of FABP4 do not hinder osteogenic differentiation. While this result may be disheartening, it directs us towards further research, suggesting that FABP4 might influence OCs differentiation.

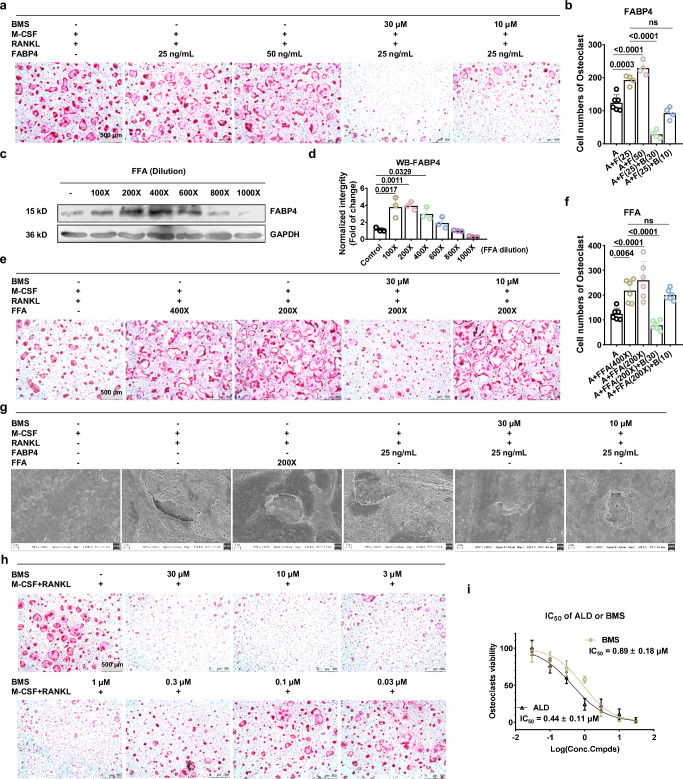

Fabp4 plays a crucial role in enhancing OCs differentiation

To assess the impact of exogenous FABP4 on the differentiation of bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMMs) into OCs, we first induced primary mouse bone marrow single-nucleus cells (BMNCs) into BMMs using M-CSF31. During the subsequent induction of BMMs into OCs with RANKL, we introduced recombinant mouse FABP4 and its inhibitor BMS. TRAP staining results revealed that the addition of 25 ng/mL FABP4 significantly promoted the formation of OCs, and this effect could be reversed by BMS (Fig. 3a, b).

Fig. 3. Increased endogenous or exogenous FABP4 protein both exacerbates OCs differentiation.

a TRAP staining of BMMs after the treatment of rmFABP4 (25 ng/mL or 50 ng/mL) or simultaneously with FABP4 inhibitor BMS (10 μM or 30 μM). Scale bar, 500 μm. n = 4 for each 96-well plate. b Quantitative cell number of OCs in (a). n = 4 for each 96-well plate. c–d Western Blotting strips (c) and its quantitative analysis results (d) indicated treatment with FFA mixture will upregulate the intracellular FABP4 in BMMs. n = 3 independent experimental samples per group. e TRAP staining of BMMs after the treatment of FFA mixture (200X or 400X dilution) or simultaneously with FABP4 inhibitor BMS (10 μM or 30 μM). Scale bar, 500 μm. f Quantitative cell number of OCs in (e). n = 6 for each 96-well plate. g SEM results of bovine bone slices show that bone resorption experiments were conducted with OCs and treated with rm-FABP4, FFA, and BMS. Scale bar, 2 μm. Three independent experiments were performed. h TRAP staining of BMMs after treated with different concentration of BMS. Scale bar, 500 μm. n = 6 for each 96-well plate. i Comparison of the IC50 values of ALD and BMS in inhibiting OCs differentiation activity; n = 6 for each 96-well plate. The IC50 values were calculated by log(inhibitor) vs. normalized response - Variable slope. All experiments were run in at least triplicate. All data is presented as mean ± SEM with p-values (b, d, f, i), ns no significance. Data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (b, d–f). Source data are provided as Source Data file.

To further investigate the effect of increased endogenous FABP4 on OCs formation, we added a mixture of free fatty acids (FFA) to the culture medium32. Western blotting results indicated a significant increase in intracellular FABP4 expression in BMMs with 200X and 400X diluted FFA (Fig. 3c, d). The subsequent addition of FFA and FABP4 inhibitors during OCs differentiation showed that FFA alone significantly increased the number of differentiated OCs, an effect that could be reversed by BMS (Fig. 3e, f).

Confocal microscopy images of F-actin staining in OCs revealed a more regular and distinct bone skeleton structure with abundant F-actin when stimulated by additional FABP4 or FFA compared to the group with only RANKL and M-CSF (Supplementary Fig. 2a). Furthermore, we confirmed the influence of FABP4 on the bone-resorptive capabilities of mature OCs on bovine bone slices. The addition of FFA or FABP4 enhanced bone resorption, whereas the FABP4 inhibitor effectively blocked this process (Fig. 3g, Supplementary Fig. 2b). All of these experiments robustly demonstrate that FABP4 significantly promotes the differentiation of OCs and enhances bone resorption.

FABP4 inhibitor BMS shows comparable OCs differentiation inhibition to ALD

Given the significant expression of FABP4 in BMMs cells (Fig. 3c), we postulated that an FABP4 inhibitor could inhibit OCs differentiation even without external stimuli. The initial CCK8 assay revealed that BMS, at concentrations up to 50 μM, did not hinder the proliferation of BMMs cells (Supplementary Fig. 3a). Subsequently, the successful validation of our hypothesis through TRAP staining after exposure to different doses of BMS underscores the intricate role of FABP4 in OCs differentiation (Fig. 3h, Supplementary Fig. 3b). Remarkably, the in vitro efficacy of BMS in inhibiting OCs, comparable to that of the established clinical therapy ALD (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d), reinforces its therapeutic promise. With an IC50 value of approximately 0.89 μM for BMS and 0.44 μM for ALD (Fig. 3i), these results demonstrate the potency of BMS in regulating OCs function.

FABP4 inhibitor suppresses OCs differentiation via Ca2+-Calcineurin-NFATc1 pathway

To further investigate the mechanism by which FABP4 inhibitors impede OCs differentiation, we performed transcriptome sequencing on three groups: BMMs cells, BMMs-induced OCs, and OCs treated with 1 μM BMS during induction (OCs + BMS). Differentially expressed genes were analyzed using volcano plots for BMMs vs. OCs and OCs vs. OCs + BMS (Fig. 4a). A Venn diagram identified 107 genes upregulated 2-fold in BMMs-induced OCs and 284 genes downregulated 0.3-fold in OCs post-BMS treatment, with 69 common genes identified for KEGG pathway analysis (Fig. 4b) and GO analysis (Supplementary Fig. 4a). The most affected KEGG pathways were OCs differentiation and calcium signaling (Fig. 4c). Cluster analysis of FPKM values (Fig. 4d) and subsequent qPCR validation (Fig. 4e) revealed significant downregulation of key genes related to OCs differentiation, including Oscar, Trap, c-fos and Nfatc1, following BMS treatment. Consequently, Western Blotting results (Fig. 4f) confirmed the suppression of TRAP, c-Fos, and NFATc1 protein levels (Fig. 4g), thereby confirming that FABP4 inhibitors suppress OCs differentiation at both the transcriptional and translational levels.

Fig. 4. BMS blocks OCs differentiation via Ca2+-Calcineurin-NFATc1 signaling pathway.

a Volcano plot of transcriptome sequencing comparing BMMs vs. OCs and OCs vs. OCs treated with 1 μM BMS. n = 3 independent experimental samples. b Venn diagram showing upregulated genes in BMMs vs. OCs and downregulated genes in OCs vs. OCs + BMS. c KEGG pathway analysis of intersecting genes from the Venn diagram. d Cluster analysis of FPKM values for genes associated with OCs differentiation. e qPCR results of differentially expressed genes mentioned in (d). n = 3 independent experimental samples. f Western Blotting results of OCs differentiation marker proteins. g Quantitative analysis of (f). n = 3 independent experimental samples. h Flow cytometry quantification of intracellular Ca2+ concentration in OCs treated with FABP4 (25 ng/mL), FABP4 (25 ng/mL) + BMS (30 μM or 10 μM) (F + BMS30, F + BMS10), and BMS (1 μM) (BMS1) alone. i In situ fluorescence imaging of intracellular Ca2+ in OCs across different groups. Scale bar, 100 μm. Three independent experiments were performed. j Expression levels of Calcineurin and PLCγ proteins in OCs after BMS treatment. k Quantitative analysis of (j). n = 4 independent experimental samples. l Schematic diagram illustrating the mechanism by which the FABP4 inhibitor suppresses OCs differentiation. Created in BioRender. Li, J. (2025) https://BioRender.com/ha5yaui. All experiments were run in at least triplicate. All data is presented as mean ± SEM with p values (e, g, k), ns = no significance. Data was analyzed by one-tailed Student’s t-test (a, c) and one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (e, g, k). Source data are provided as Source Data file.

Regarding the critical role of the calcium signaling pathway highlighted by KEGG, we examined intracellular calcium levels in OCs, OCs + FABP4, OCs + FABP4 + BMS, and OCs + BMS using the calcium fluorescent probe Fluo-4 AM via flow cytometry (Fig. 4h, Supplementary Fig. 4b) and fluorescence microscopy (Fig. 4i). Results showed a significant increase in intracellular calcium levels in OCs with FABP4, which was reversed by BMS. The calcium signaling pathway is crucial in OCs differentiation33, whereby RANKL-RANK interaction activates downstream PLCγ, leading to elevated intracellular calcium concentrations and subsequent Calcineurin activation34. This cascade dephosphorylates NFATc1, regulating transcription of key proteins such as TRAP, CTSK, and OSCAR in the nucleus35. Our transcriptome analysis indicated no change in Plcγ gene expression post-BMS treatment, supported by Western Blotting showing constant PLCγ levels, while the Calcineurin A and B subunits were significantly downregulated (Fig. 4j, k). This suggests that FABP4 elevates calcium levels in OCs, thereby activating the Ca2+-Calcineurin-NFATc1 pathway to promote OCs differentiation, thus expanding our understanding of this cellular process (Fig. 4l).

Effects of FABP4 inhibitor on bone resorption in OVX mouse PMOP model

To further validate the in vivo efficacy of FABP4 inhibitors against PMOP, we established a bilateral OVX-induced mouse model simulating PMOP. Mice were divided into Sham, Model, ALD (1.3 mg/kg), and BMS (10 mg/kg) groups. The Sham group underwent minor fat removal near the ovaries. After 28 days of daily oral gavage, serum, uterus, tibia, femur, and lumbar vertebrae were collected (Fig. 5a). Uterine atrophy confirmed successful modeling (Supplementary Fig. 5a). OVX induced weight gain, while ALD and BMS groups showed slight reductions compared to the Model group, maintaining overall stability (Supplementary Fig. 5b). ELISA revealed elevated serum FABP4 levels in the Model group, significantly reduced by ALD and BMS treatments (Fig. 5b), highlighting the link between FABP4 levels and PMOP progression.

Fig. 5. Oral FABP4 inhibitor BMS increases bone density in OVX mice by inhibiting bone resorption.

a Schematic illustration of the animal study groups and experimental procedures. The scissors, ovary and syringe icons are from templates provided by ChemDraw. b–d ELISA detection of serum levels of FABP4 (b) PINP (c) and CTX-1(d) at the endpoint. n = 5 mice per group in (b, d) and 10 mice per group in (c). e Micro-CT scans of the distal femur in each group, with trabecular bone highlighted in blue and the 3D analysis conducted within the defined ROI region. f Coronal micro-CT images of the L4-L5 lumbar vertebrae in each group, with the 3D analysis ROI region highlighted in bright blue. g–i BMD (g) Tb.Th (h) and Tb.N (i) of trabecular bone in the distal femur for each group. j–l BMD (j) Tb.Th (k) and Tb.N (l) in the trabecular bone of the L5 lumbar vertebra. m–n Quantitative TRAP staining results (m) and representative images (n) of demineralized proximal tibia sections in each group. n = 4 mice per group (g–m). Scale bar, 400 μm and 100 μm. All data is presented as mean ± SEM with p values (b–d, g–m). ns no significance. Data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (b–d, g–m). Source data are provided as Source Data file.

Subsequently, we assessed serum levels of the bone formation marker PINP (Fig. 5c) and the bone resorption marker CTX-1 (Fig. 5d). Similar to ALD, FABP4 inhibitors had little effect on bone formation but reduced bone resorption. Micro-CT of the distal femur (Fig. 5e) and L4-L5 lumbar vertebrae (Fig. 5f) demonstrated attenuated bone loss and OP progression in BMS-treated OVX mice. 3D analysis revealed increased femoral BMD (Fig. 5g), trabecular thickness (Tb.Th, Fig. 5h) and trabecular number (Tb.N, Fig. 5i) with BMS treatment. Notably, BMS showed greater efficacy in the lumbar spine than ALD (Supplementary Fig. 5c), significantly improving BMD (Fig. 5j), Tb.Th (Fig. 5k), Tb.N (Fig. 5l), bone volume/total volume (BV/TV, Supplementary Fig. 5d), and trabecular separation (Tb.Sp, Supplementary Fig. 5e).

Regarding bone strength, we performed a three-point bending test on the femoral midshaft (approximately 6.5 mm from the distal femur) across all groups (Supplementary Fig. 5f). No significant differences in maximum force were observed among the groups (Supplementary Fig. 5g). However, further analysis combining micro-CT data revealed that oral administration of BMS improved the elastic modulus (Supplementary Fig. 5h) and bone stiffness (Supplementary Fig. 5i) in OVX mice. These findings provide preliminary evidence that oral FABP4 inhibitors enhance bone strength in OVX mice.

TRAP staining further confirmed the inhibitory effect of BMS on bone resorption in vivo (Fig. 5m, n). Additionally, H&E staining (Supplementary Fig. 5j, l)and IHC analysis of FABP4 protein expression (Supplementary Fig. 5k, m) in bone marrow fat tissue revealed no significant difference between the BMS and ALD treatments, suggesting that the lack of impact on osteogenic and adipogenic differentiation of BMSCs may account for this.

Pharmacokinetics (PK) and tissue distribution of BMS: implications for bone-targeted therapies in PMOP treatment

FABP4 is extensively distributed across various tissues, including adipose tissue, liver, intestines, heart, and muscles36. This ubiquitous distribution presents challenges in developing FABP4 inhibitors, as their systemic effects may be unpredictable due to the inhibition across multiple tissues. Furthermore, the PK properties of these inhibitors may be affected by the widespread expression of FABP4, potentially compromising their therapeutic efficacy and safety.

In our in vivo study, the oral dose of ALD (1.3 mg/kg) followed clinical standards15, whereas the BMS dose (10 mg/kg) was based on preclinical doses for diabetes37. Although BMS demonstrated comparable activity to ALD in vitro, in vivo results showed that even at 7.7 times the ALD dose, BMS did not achieve the same efficacy in femur. Specifically, compared to ALD, FABP4 inhibitors had no significant effect on trabecular number (Tb.N, Fig. 5j) in OVX mice. Western Blotting of OVX mouse tissues revealed substantial FABP4 in muscles, white adipose tissue (WAT), brown adipose tissue (BAT), heart, and kidneys, while bone marrow showed minimal presence (Supplementary Fig. 6).

PK evaluations of BMS in SD rats provided insights into systemic behavior. Following intravenous (IV) administration (2.0 mg/kg) (Fig. 6a), BMS displayed rapid systemic exposure with a Tmax of 0.083 h, a short T₁/₂ of 1.77 h, and a high Cmax of 7094.95 ng/mL, indicating fast clearance (Cl = 691.37 mL/h/kg). The moderate volume of distribution (Vz = 1734.16 mL/kg) suggests limited tissue penetration. In contrast, after oral administration (10.0 mg/kg) (Fig. 6b), BMS exhibited slower absorption with a Tmax of 2.00 h, an extended T₁/₂ of 3.16 h, and a significantly lower Cmax (1261.10 ng/mL), indicating limited absorption and potential first-pass metabolism. Despite the higher oral dose, the AUC(0-t) was 5527.36 h·ng/mL, indicating reduced systemic exposure compared to IV administration. Moreover, MRT was longer in the oral group (2.76 h) than in the IV group (0.84 h), suggesting more sustained systemic exposure.

Fig. 6. PK data and tissue distribution of BMS in SD rats.

a PK data of three SD rats (101–103) following intravenous administration of BMS at a dose of 2 mg/kg. b PK data of three SD rats (201–203) following oral gavage of BMS at a dose of 10 mg/kg. c, d Tissue distribution of BMS in female (c) and male (d) SD rats at 0.25 h, 1 h, 4 h, and 8 h after oral gavage at a dose of 10 mg/kg. Distribution was assessed in the small intestine, lung, liver, stomach, kidney, heart, bone marrow (highlighted in red and emphasized), ovaries or testes, spleen, large intestine, bladder, adipose tissue, brain, and skeletal muscle. PK parameters included: T1/2 (half-life), Tmax (time to peak concentration), Cmax (maximum concentration), AUC(0–t) (area under the curve from 0 to t), AUC (0–∞) (area under the curve from 0 to infinity), MRT(0–t) (mean residence time from 0 to t), MRT (0–∞) (mean residence time from 0 to infinity), C0 (initial concentration), Vss (volume of distribution at steady state), Vz (apparent volume of distribution), Cl (clearance), F (oral bioavailability). Source data are provided as Source Data file.

Based on PK data, we further analyzed BMS distribution in 16 tissues (brain, heart, lungs, liver, stomach, spleen, kidneys, skeletal muscle, abdominal fat, testes/ovaries, uterus, bladder, small intestine, large intestine, and bone marrow) at different time points (0.25 h, 1 h, 4 h, and 8 h) post oral administration in both female (Fig. 6c) and male (Fig. 6d) SD rats. The results revealed significant accumulation in the small intestine and liver at all time points. Notably, bone marrow accumulation increased over time, with the highest concentration at 8 h (6.21% in females and 0.93% in males), indicating progressive accumulation in bone marrow, crucial for osteoporosis treatment. Although there were sex-based differences, with higher concentrations in female rats at certain time points, the overall distribution pattern suggests that bone-targeted therapies could benefit from optimizing BMS delivery. These findings highlight the need for further research into bone-specific targeting strategies to maximize BMS efficacy in PMOP.

Developing bone-targeted PLGA NPs for BMS delivery with click chemistry

The structural similarity of bisphosphonates to inorganic phosphates in bone allows them to establish strong bonds with hydroxyapatite (HA) crystals on bone surfaces. Studies have shown that bisphosphonate-modified PLGA-PEG NPs enable controlled drug release, proving effective in addressing diverse bone conditions38–40. In this study, bisphosphonate-conjugated PLGA-PEG (PLGA-PEG-Ald) was synthesized via click chemistry using PLGA-PEG-N3 and DBCO-ALD (Fig. 7a). The structure was confirmed by FT-IR (Supplementary Fig. 7) and 1H NMR (Supplementary Fig. 8). Previous research has demonstrated that NPs assembled from polymers with 20% PLGA-PEG-Ald exhibit superior stability and bone-targeting ability38. Building on these findings, the incorporation of BMS into Ald-BMS-NPs, composed of 20% PLGA-PEG-Ald and 80% PLGA-PEG, shows promise. Notably, NPs made entirely of PLGA-PEG are referred to as PLGA-BMS-NPs (Fig. 7b).

Fig. 7. Click chemistry constructs NPs for bone-targeted delivery of FABP4 inhibitors.

a Systematic strategy for one-step click chemistry synthesis of PLGA-PEG-Ald amphiphilic polymers. b Description of the self-assembly process of polymers into Ald-BMS-NPs. c Zeta potentials of PLGA-BMS-NPs and Ald-BMS-NPs. Data was represented mean ± SEM with p values; n = 3 independent samples per group. d DLS size distribution and TEM morphology of Ald-BMS-NPs. Scale bar, 100 nm. e DLS size distribution and TEM morphology of PLGA-BMS-NPs. Scale bar, 100 nm. Data was represented mean ± SEM; n = 3 independent samples per group. f Cumulative release curve of BMS in pH 7.0 PBS over time for PLGA-BMS-NPs and Ald-BMS-NPs. Data represent mean ± SEM; n = 3 independent samples per group. g In situ fluorescence images of BMMs uptake of Ald-BMS-Cy5-NPs and PLGA-BMS-Cy5-NPs after 30 min. Scale bar, 10 μm. h Representative TEM images of surface-bound nano-hydroxyapatite on Ald-NPs and PLGA-NPs. Scale bar, 200 nm. All experiments were run in triplicate. Data was analyzed by two-tailed unpaired t test (c) and one-sample t-test (d–f). Source data are provided as Source Data file.

The encapsulation efficiency of BMS in Ald-BMS-NPs and PLGA-BMS-NPs is 43.94% and 30.43%, respectively, with drug loading rates of 4.21% and 2.95%, significantly higher than reported in existing literature38. The particle surface Zeta potential of Ald-BMS-NPs is approximately −21.6 mV, while that of PLGA-BMS-NPs is around −19.0 mV, indicating successful enrichment of bisphosphonate ions on Ald-BMS-NPs’ surface (Fig. 7c). The particle size of Ald-BMS-NPs is uniform, with an average size of about 183.3 ± 2.8 nm (Fig. 7d), slightly larger than that of PLGA-BMS-NPs at 167.9 ± 1.7 nm (Fig. 7e).

Then in vitro CCK-8 experiments showed that different concentrations of Ald-BMS-NPs, PLGA-BMS-NPs, and empty Ald-NPs did not exhibit cytotoxicity towards BMMs cells (Supplementary Fig. 9a). The BMS encapsulated in Ald-BMS-NPs demonstrated slow release in physiological saline at pH 7.0 for at least 72 h, with a slightly faster release rate compared to PLGA-BMS-NPs (Fig. 7f). By introducing a small amount of fluorescent molecule Cy5 into both NPs, Ald-BMS-Cy5-NPs and PLGA-BMS-Cy5-NPs were obtained. Under confocal microscopy, both types of NPs were observed to be readily taken up by BMSCs after 30 min (Fig. 7g) of co-culturing and had increased accumulation within the cells after 6 h (Supplementary Fig. 9b).

Subsequently, the bone-targeting efficacy of Ald-BMS-NPs was confirmed through both in vitro and in vivo assessments. Initially, Ald-BMS-NPs and PLGA-BMS-NPs were incubated with nano-HA, as visualized with TEM imaging (Fig. 7h). This revealed strong adhesion of Ald-BMS-NPs to HA. Furthermore, Cy5-labeled NPs were co-cultured with bovine bone slices, illustrating increased binding of Ald-BMS-NPs (Supplementary Fig. 10a). In vivo validation using IVIS revealed Ald-BMS-NPs exhibited significantly enhanced bone targeting compared to PLGA-BMS-NPs (Supplementary Fig. 10b, c). IVIM imaging at 24- and 48-hours post-injection highlighted preferential accumulation of Ald-BMS-Cy5-NPs in the bone marrow, underscoring their potent bone-targeting capabilities (Supplementary Fig. 10d).

In conclusion, our click-chemistry-derived PLGA-NPs demonstrate precise bone and bone marrow targeting, uniform size, efficient drug loading, controlled release, and are tailored for targeted FABP4 inhibitor delivery in vivo.

Bone-targeted NPs delivery of FABP4 inhibitor shows enhanced anti-OP effect in OVX mouse PMOP model

To validate the in vivo efficacy of bone-targeted Ald-BMS-NPs loaded with FABP4 inhibitors, we re-established the OVX mouse model. Seven days post-bilateral ovariectomy, all groups received at uniform dose of 10 mg/kg to ensure comparability. C57BL/6 J mice were divided into groups: Sham (saline), Model (saline), ALD (10 mg/kg), Free BMS (10 mg/kg), Ald-BMS-NPs (10 mg/kg BMS), and empty Ald-NPs (equivalent PLGA content without BMS). Mice received bi-weekly intraperitoneal injections for four weeks (Fig. 8a), and body weight was monitored every other day (Supplementary Fig. 11).

Fig. 8. Bone-targeting NPs loaded with FABP4 inhibitors effectively alleviate PMOP in vivo.

a Schematic illustration of the administration protocol for Ald-BMS-NPs treatment in OVX mice. The scissors, ovary and syringe icons are from templates provided by ChemDraw. n = 6 mice for each group. b Representative 3D reconstructed images of Micro-CT scans of femur from each group. c BMD data of the femur from different groups of mice. n = 4 mice per group. d Results of Micro-CT 3D analysis for BV/TV, Tb.Th, Tb.N and Tb.Sp across different groups. Data represent mean ± SEM; n = 4 mice per group. e Serum markers of liver and kidney function in the various groups of mice, Reference values ranges were obtained from literature53. Data are presented as mean ± SEM, with p-values shown in parentheses. Values exceeding the reference range are highlighted in bold; n = 3 mice per group. All data is presented as mean ± SEM with p-values (c, d), ns = no significance. Data was analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test (c, d). Source data are provided as Source Data file.

At the study endpoint, femur (Fig. 8b), tibia (Supplementary Fig. 12a) and lumbar vertebrae (Supplementary Fig. 12d) were analyzed using Micro-CT. BMD measurements at the femoral distal end (Fig. 8c), proximal tibia (Supplementary Fig. 12b), and lumbar L5 region (Supplementary Fig. 12c) showed no improvement in the OVX group treated with empty Ald-NPs. In contrast, BMS administration significantly increased BMD, with Ald-BMS-NPs showing marked BMD elevation, approaching Sham levels. Micro-CT reconstruction revealed reduced trabecular bone loss and increased bone mass in the Ald-BMS-NPs group compared to ALD and Free BMS groups. 3D analysis further confirmed improved Tb.Sp, BV/TV, and Tb.N in femur (Fig. 8d) and tibia(Supplementary Fig. 12b), and higher BV/TV in the lumbar vertebrae (Supplementary Fig. 12e). Although statistically similar to ALD, Ald-BMS-NPs showed slightly better values. Bone strength analysis showed no significant differences in maximum force at the femoral midshaft (Supplementary Fig. 12f). Three-point bending tests indicated intraperitoneal BMS had weaker effect on elastic modulus (Supplementary Fig. 12g) and stiffness (Supplementary Fig. 12h) than oral dosing, while Ald-BMS-NPs demonstrated significant improved, comparable to ALD, confirming the efficacy of bone-targeted BMS delivery.

To assess the impact of NPs on liver and kidney functions, serum markers of liver enzymes (ALT, AST, ALP, γ-GT) and kidney function indicators (UREA, CREA, UA) were measured. No abnormalities were observed across groups, except for elevated AST in one mouse from the Ald-BMS-NPs group and increased UA in the ALD group (Fig. 8e). H&E staining of heart, liver, spleen, lungs, and kidneys revealed no histological changes (Supplementary Fig. 13). These findings demonstrate that bone-targeted NPs loaded with FABP4 inhibitors effectively alleviate PMOP with good safety, supporting their therapeutic potential in PMOP treatment.

Discussion

Bone and adipose tissues share numerous metabolic pathways and significantly influence each other30,41. Imbalances in lipid metabolism, involving products like fatty acids and cholesterol, can impact bone density42, with fatty acids providing energy43 and cholesterol acting as a precursor for vitamin D, which is essential for calcium absorption and bone health44. Adipose tissue secretes hormones and cytokines, such as leptin45 and adiponectin46, that affect bone cell function and metabolism. Therefore, targeting lipid metabolism in anti-osteoporosis drug research could address both metabolic syndrome and osteoporosis. While peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor-γ (PPAR-γ) agonists, such as rosiglitazone47 and pioglitazone48, which are used to treat type 2 diabetes, can decrease bone density by influencing adipocyte and osteocyte differentiation. In this study, we has revealed that FABP4, a lipid protein involved in fatty acid transport and metabolism, can promote bone resorption to exacerbate PMOP. This may clarify why patients with metabolic syndrome, especially those with high FABP4 levels, such as diabetics, are frequently more susceptible to OP7. Therefore, investigating FABP4’s role in bone metabolism and developing effective FABP4 inhibitors is crucial for OP prevention and treatment.

An important finding in this study was that FABP4 inhibitors suppress OCs differentiation by inhibiting the Ca²⁺-Calcineurin-NFATc1 signaling pathway. When intracellular calcium levels rise, calmodulin binds to Ca²⁺, forming a complex that activates calcineurin49. This leads to the dephosphorylation and nuclear translocation of the NFATc transcription factor, which then regulates genes associated with OCs differentiation50. The study shows that overexpression of FABP4 can increase Ca²⁺ concentration in OCs precursors. This may be due to FABP4’s role in binding and transporting fatty acids, altering the intracellular lipid environment and calcium ion flux, thus promoting NFATc activation. This discovery is the first to confirm that FABP4 influences OCs differentiation via the Ca²⁺-Calcineurin-NFATc pathway, providing significant insights into the mechanisms of OCs differentiation.

By inducing OCs differentiation with the FABP4 inhibitor BMS, we determined its inhibitory potency (IC50 = 0.89 μM), comparable to the clinical drug ALD. This suggests that BMS has significant clinical potential. However, despite promising preclinical results, the clinical trials of FABP4 inhibitors are still in their early stages due to the widespread distribution of FABP4 in adipose tissue36. Nonetheless, as FABP4 is a key biomarker for metabolic syndrome, the development of highly selective FABP4 inhibitors remains a major focus of research51,52. Our study demonstrated that oral administration of FABP4 inhibitors effectively improves bone density in mice, indicating the potential for these inhibitors to simultaneously address inflammation, insulin resistance, and OP. Additionally, advancements in drug delivery systems suggest that bone-targeting NPs carrying FABP4 inhibitors can achieve therapeutic effects comparable to existing clinical PMOP drugs. This significantly broadens the potential clinical applications for FABP4 inhibitors.

In summary, our study demonstrates that FABP4 exacerbates PMOP by promoting bone resorption, as proven by clinical and experimental data. The FABP4 inhibitor BMS shows activity comparable to ALD in vitro, inhibiting OC differentiation by reducing calcium ion concentration and suppressing the Ca2+-Calcineurin-NFATc pathway. Oral administration of FABP4 inhibitors significantly increased bone mass in OVX mice, although it was less effective than ALD. Bone-targeting NPs delivering the FABP4 inhibitor demonstrated efficacy comparable to ALD. This research establishes a basis for using FABP4 inhibitors in treating OP-related diseases, with significant practical implications.

Methods

Ethic statement

All animal handling and use was approved by Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee (IACUC) at Shenzhen University Medical School on May 30, 2023. The registration number is IACUC-202300048. The study adhered to the ARRIVE guidelines for reporting animal experiments.

Human studies were reviewed and conducted in accordance with the approval of the ethics committee at Shenzhen University General Hospital (NCT number: KYLLMS-17). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Human studies were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Study design

The primary aim of this study is to validate FABP4 as a promising therapeutic target for PMOP. Serum levels of FABP4 in patients were measured using ELISA to determine its role in exacerbating OP, either by inhibiting bone formation or promoting bone resorption. This investigation included Alizarin Red S staining for BMSC osteogenic differentiation and TRAP staining for the differentiation of bone marrow mononuclear cells into OCs. Additionally, we developed an ovariectomized mouse model to assess the efficacy of a FABP4 inhibitor in treating PMOP, mainly utilizing Micro-CT and histological TRAP staining. Results indicated inconsistent efficacy of the FABP4 inhibitor across in vivo and in vitro settings. To address this discrepancy, we developed bone-targeting drug-loaded NPs and evaluated their distribution using IVIS and IVIM imaging, aiming to achieve targeted delivery of the FABP4 inhibitor to bone tissue.

Animal study

Sixty, Ten- to 12-week-old, female C57BL/6 J mice were purchased from BesTest Bio-Tech (Zhuhai, China). All mice were kept in a pathogen-free environment at Shenzhen university. Mice were accommodated in group housing under conditions of 20–24 °C temperature and 40%–60% humidity, following a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle. Mice were fed a standard chow diet (Keao, cat#12231, CN) with ad libitum access to food and water. Initially, all mice were anesthetized with isoflurane and their fur was shaved. A 1 cm incision was carefully made in the skin and peritoneum, 1 cm away from the spine. For model mice, both ovaries were surgically removed and ligated, whereas in the control group, a minor fat deposit was excised. Subsequently, the incision was meticulously sutured, and iodine was applied for disinfection. Euthanasia was performed by CO2 inhalation followed by cervical dislocation.

Human study

To assess bone health, we measured adult BMD at the hip, including the total hip, femoral neck, and femoral metaphysis, in accordance with ISCD guidelines. BMD values were expressed in milligrams per square centimeter, and T-scores and Z-scores were calculated relative to local population norms.

For the human serum samples analysis, a total of 15 patients who were diagnosed of Non-OP and PMOP at Shenzhen University General Hospital in Shenzhen, China. Patients with a history of systemic autoimmune diseases or severe infectious diseases were excluded from the study. After 2 h fasting period, blood samples were drawn and centrifuged at 700 × g for 5 min. The plasma samples were then stored at −80 °C until further analysis. All PMOP patients were postmenopausal women aged 55 and above, with their biological sex being female.

Primary cell culture

BMNCs were isolated from 6- to 8-week-old C57BL/6 J mice by dissecting intact tibia and femur post-euthanasia. The bone marrow cavity was washed with DMEM complete medium, and cells were filtered and separated using an animal bone marrow mononuclear cell isolation kit. After overnight culture in αMEM complete medium (Gibco, cat#10091148), non-adherent cells were supplemented with 50 ng/mL of M-CSF (Peprotech, cat#315-02) for adhesion and differentiation into BMMs.

OCs formation

The BMNCs were differentiated into BMMs using 50 ng/mL of M-CSF for two days. This was followed by the addition of 50 ng/mL of M-CSF and 100 ng/mL of sRANKL (Peprotech, cat#315-02) for an additional 4 days to promote their differentiation into OCs. The culture medium was refreshed every two days throughout the process. Subsequently, cells were stained following the protocol of the TRAP Staining Kit (Servicebio, cat#G1050), with cell nuclei stained using hematoxylin. For treatment, 25 ng/mL or 50 ng/mL of FABP4 protein (MCE, cat#HY-P70293) and FFA lipid mixture (Sigma, cat#L0288) diluted 200x and 400x were used. The FFA lipid mixture contains non-animal-derived fatty acids (2 μg/ml arachidonic acid, and 10 μg/ml each of linoleic acid, linolenic acid, myristic acid, oleic acid, palmitic acid, and stearic acid), along with 0.22 mg/ml cholesterol from New Zealand sheep wool, 2.2 mg/ml Tween 80, 70 μg/ml tocopheryl acetate, and 100 mg/ml Pluronic F-68, with water for cell culture as the solvent. For experiments involving this lipid mixture, the control groups included 2.2 mg/ml Tween 80, 70 μg/ml tocopheryl acetate, and 100 mg/ml Pluronic F-68 to account for the effects of these components.

Bone resorption activity on mature OCs

Cow bone slices (TuyuanBiotech, China)were arranged in a 96-well plate, and BMNCs were added to each well at a density of 5×104 cells. The cells were then cultured according to the OCs culture protocol for 11 days, with the medium refreshed every other day. Drawing from existing literature, the bone slices underwent a series of treatments: rinsing with distilled water, immersion in 1% ammonia solution under ultrasound for 30 min, dehydration, and drying using a gradient of alcohols prior to field emission scanning electron microscope (ZEISS, SUPRA55).

RNA-seq studies

BMMs, OCs, and OCs + BMS (MCE, cat#HY-101903) groups were collected. The cells were lysed using TRIZOL reagent and sent to BGI Genomics for RNA extraction and bulk mRNA sequencing. The raw sequencing data analysis was performed as previously described. The BMMs group consisted of cells induced with M-CSF for two days. The OCs group consisted of BMMs induced with both M-CSF and sRANKL. The OCs + BMS3 group consisted of BMMs induced with M-CSF, sRANKL, and 1 μM BMS.

NPs self-assembly, drug loading and characterization

Weigh 4 mg of PLGA(50:50, 20 K)-PEG2000-Ald, 16 mg of PLGA(50:50, 20 K)-PEG2000, and 1 mg of BMS in 1 mL of dichloromethane. Add 1 mL of 2% PVA solution and sonicate the mixture for 15 min using a probe sonicator (50%, 10 s on / 10 s off intervals) (SCIENTZ, China). Subsequently, introduce the emulsion into 13 mL of 0.2% PVA solution and sonicate for an additional 15 min at 50% power with the same intervals. The solution is left to stir at room temperature at 100 × g overnight. After centrifugation at 800 × g for 10 min, discard the sediment, and then discard the supernatant after subjecting it to centrifugation at 20,000 × g for 30 min. Dissolve the sediment in 1 mL of ultrapure water, centrifuge again at 800 × g for 10 min, and collect the supernatant as Ald-BMS-NPs. NPs formed without PLGA(50:50, 20 K)-PEG2000-Ald are known as PLGA-BMS-NPs. Adding 0.015 mg of Cy5 under the same conditions yields Ald-BMS-Cy5-NPs and PLGA-BMS-Cy5-NPs. NPs formed without BMS are denoted as Empty Ald-NPs following the same procedure.

Transfer 100 μL of NPs loaded with BMS, disrupt the emulsion with 900 μL of acetonitrile, centrifuge the mixture, and collect the supernatant for HPLC (SHIMADZU, LC-20ADxr) analysis to assess drug loading and encapsulation efficiency. Utilize a Malvern particle size analyzer (ZETASIZER NANO ZS) to determine the size and zeta potential of the NPs. Capture the morphology of the NPs using transmission electron microscopy (TEM, G2 Spirit Biotwin).

ELISA assay of serum PINP, CXT-1and FABP4

In brief, serum samples were obtained from human or mouse blood samples. The levels of Serum P1NP, CTX1, and FABP4 were quantified using specific ELISA kits: PINP ELISA kit (animaluni, cat#LV30683), CTX1 ELISA kit (animaluni, cat#LV30790), and FABP4 ELISA kit (Thermo Fisher, cat#EH177RB), respectively, following the instructions provided by the manufacturers.

Establishment of BMSCs stably transfected FABP4

The pLV2-CMV-FABP4(human)-3×FLAG-ZsGreen1-puro plasmid-packaged lentivirus (2 × 108 Tu/mL) was procured from DINGKE Biotech (Shenzhen, China). BMSC cells were cultured to 40%-60% confluency over 18–24 h before being exposed to 8 μg/mL Polybrene to enhance transfection efficiency. Following a 6 h viral infection period, the cells were switched to standard culture medium for an additional 48 h. Positive cell clones were selected with 1 μg/mL Puromycin, ensuring continuous cell subculture and monitoring throughout the screening process. Subsequently, quantitative real-time RT-PCR and Western blot were conducted to assess FABP4 gene expression.

In vitro osteoblastic differentiation of BMSCs

Primary BMSCs were obtained from OriCell (Guangzhou, China) and plated in 6-well plates at a density of 5 × 105 cells/well. They were then cultured in osteogenic medium consisting of α-MEM with 10% FBS, 50 μg/mL ascorbic acid (Sigma, cat#PHR1008), 10 mM sodium β-glycerophosphate (Sigma, cat#G5422), and 10 nM dexamethasone (Sigma, cat#D1756) for a 14-day period. Upon the observation of ample calcium nodules using a microscope, the cells were fixed in 10% neutral formalin, stained with 1% Alizarin Red (Sigma, cat#A5533) in a dark environment, air-dried, and photographed. Subsequently, 400 μL of 10% cetylpyridinium chloride was added to each well, incubated at room temperature in the dark for 30 minutes, and the OD value was measured at 562 nm.

RT-qPCR and western blotting

RT-qPCR analysis was performed as previously described. The cells were lysed using TRIZOL (Thermo Fisher, US), reverse transcribed with PrimeScript RT Master Mix (TaKaRa, cat#RR036A), and underwent RT-qPCR analysis on a LightCycler96 machine with TB Green dye (TaKaRa, cat#RR820A), employing the primers detailed in Supplementary Table 2.

Protein lysates from BMSC cells or BMMs were extracted using RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher, US), separated by 10% SDS-PAGE, and transferred to a PVDF membrane (Millipore, GER). The membrane was blocked with 5% Bovine Serum Albumin in TBST and incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies including FABP4, NFATc1 (Invitrogen, cat#PA5-79730), c-Fos (Abcam, cat#ab302667), TRAP (Abcam, cat#ab191406), PLCγ (Abcam, cat#ab302940), Calcineurin A (Abcam, cat#ab52761) and Calcineurin B (Abcam, cat#ab303562). All Western blot experiments were performed using the wet transfer method. The electrophoresis process involved: constant voltage of 80 V for 20 min, followed by 120 V for 60 minutes. Regarding transfer, all membranes except for FABP4 were transferred at a constant current of 250 mA for 80 minutes (FABP4 was transferred at 200 mA for 90 minutes). For the sample loading, if not otherwise stated in the raw data, we used 20 μg of protein per lane.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

After decalcification in EDTA (Aladdin, China) for 10 days following fixation of mouse tibiae and femurs, 6 μm sections were prepared post-dehydration and paraffin embedding. The sections underwent xylene dewaxing, ethanol rehydration, and staining with Hematoxylin and Eosin (H&E, Beyotime, China) or TRAP (Servicebio, cat#G1050) as per protocols. Subsequently, the sections were dehydrated, cleared, and mounted.

Following antigen retrieval with sodium citrate (Beyotime, China), sections were blocked with 10% BSA, incubated with FABP4 antibody (Abcam, cat#ab92501) overnight, washed with PBS, incubated with goat anti-rabbit IgG H&L (HRP) (Abcam, cat#ab6721), visualized with DAB (Abcam, cat#ab64238), counterstained with hematoxylin, dehydrated, cleared, and mounted for slide scanning.

Micro-CT scanning

Fixed but non-demineralized mouse femurs were subjected to micro-CT scanning using Brucker μCT (Skyscan 1276 Micro-CT, Kontich, Belgium). The scan parameters included a 6.5 μm voxel size at medium resolution, 70 kV, 200 mA, 0.25 mm Al filter, and an integration time of 350 ms. Three-dimensional images were generated from contoured two-dimensional images using techniques based on distance transformation of the original grayscale images (CTvox, version 3.3.0). Analysis in both 3D and 2D was conducted utilizing CT Analyser software (version 1.18.8.0). Evaluation of bone microarchitecture was carried out within a region of interest (ROI) of 1.5 mm in length, commencing 0.5 mm proximal to the distal growth plate for trabecular measurements.

Three-point bending test on femoral midshaft

The femurs were dissected from each mouse and temporarily stored in cold physiological saline. Each femur was then placed horizontally on a mechanical testing machine (Machine, MX-0350), with the femoral head facing downward. The test point was located 6.5 mm from the femoral condyle, with an 8 mm span (L) and a compression speed of 5 mm/min. Stress (F) was recorded, and stiffness was calculated from the slope of the stress (F)-displacement (d) curve within the elastic range. Micro-CT measurements of the outer (B and H) and inner (b and h) diameters of the femoral midshaft at the test point were used to calculate the moment of inertia (J) using the formula . Stress was then calculated as Stress , and strain was determined using the formula Strain . The elastic modulus was calculated by determining the slope of the stress-strain curve within the elastic range.

PK analysis

PK testing was performed using male SD rats (SPF grade), sourced from Vitalriver Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. (animal reserve number: 999M-017). Nine rats were transferred, with six used for the experiment. Animals were weighed before drug administration, and the dosages were calculated accordingly. Both intravenous (IV, 2 mg/kg) and oral (PO, 10 mg/kg) administration routes were employed. Blood samples were collected at multiple time points after administration: for IV, at 0.083 h, 0.25 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 8 h, and 24 h, and for PO, at 0.25 h, 0.5 h, 1 h, 2 h, 4 h, 6 h, 8 h, and 24 h. Samples (200 μL per time point) were obtained via jugular venipuncture or other suitable methods, using K2-EDTA as an anticoagulant. Blood samples were placed on ice and centrifuged within one hour at 6800 g for 6 minutes at 2–8 °C to separate plasma, which was stored at -80 °C until further analysis. Plasma analysis was conducted by Medicilon Pharmaceutical Technology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. DMPK Analysis Laboratory, which included quality control (QC) samples for intra-day accuracy evaluation, ensuring that at least 66.7% of QC samples and 50% of samples at each concentration had accuracy within the range of 80-120%. The pharmacokinetic parameters, including AUC0-t, AUC0-∞, MRT0-∞, Cmax, Tmax, and T1/2, were calculated using Phoenix WinNonlin 7.0, with their mean values and standard deviations determined based on the concentration-time data collected from the blood samples.

Tissue distribution of BMS following a single oral gavage in SD rats

To investigate the tissue distribution of BMS following a single oral gavage in SD rats, both male and female rats (n = 8 per sex) were used. The animals were sourced from Vitalriver Laboratory Animal Technology Co., Ltd. The rats received 10 mg/kg of BMS (1 mg/mL) by oral gavage after a 10 h fasting period, and food was provided 4 h post-administration. Plasma and 16 tissues (brain, heart, lungs, liver, stomach, spleen, kidneys, skeletal muscle, abdominal fat, testes/ovaries, uterus, bladder, small intestine, large intestine, and bone marrow) were collected at time points of 0.25 h, 1 h, 4 h, and 8 h post-dosing. Blood samples (200 μL per time point) were collected via the jugular vein into K2-EDTA tubes, placed on ice, and centrifuged (6800 × g, 6 min, 2–8 °C) within 1 hour to obtain plasma, which was stored at -80 °C. After euthanasia, tissues were harvested, washed with saline, dried, and stored at –80 °C.

LC-MS/MS was used to analyze the drug concentrations in plasma and liver, with similar methods applied to other tissues. Tissue-to-plasma ratios were calculated using the formula: Tissue/Plasma ratio (mL/g) = tissue drug concentration / plasma drug concentration. All sample analyses were performed by Medicilon Pharmaceutical Technology (Shanghai) Co., Ltd., with quality control ensuring that over 66.7% of quality control samples fell within the acceptable range (80-120% for plasma, 75-125% for tissues).

Ca2+ concentration detection

After 4 days of culture with sRANKL and additional substances, the following groups were examined: OCs, OCs + FABP4 (25 ng/mL), OCs + FABP4 + BMS (30 μM or 10 μM), and OCs + BMS (1 μM). The cells’ intrinsic fluorescence was visualized using Fluo-4 AM (Beyotime, China) and a fluorescence microscope (Leica, DMI8, Japan), while the total fluorescence of the cells was quantified through flow cytometry (Easycell, China) analysis.

PLGA-PEG-Ald polymer synthesis

PLGA(50:50, 20 K)-PEG2000-N3 and PLGA(50:50, 20 K)-PEG2000 were sourced from Hzxqbio (Hangzhou, China), while DBCO-Ald was procured from Confluore (Xi’an, China). The mixture containing one molar equivalent of PLGA(50:50, 20 K)-PEG2000-N3 and 1.5 molar equivalents of DBCO-Ald was stirred at room temperature in DMSO for 3 h. Following this, 75% ethanol was introduced to the solution, stirred, and the resulting solid was filtered, freeze-dried to yield PLGA(50:50, 20 K)-PEG2000-Ald. The chemical structure was authenticated through FT-IR (Thermo Fisher IS50) and 1H NMR analyses (Bruker AV600).

Drug Release Rate of Ald-BMS-NPs

To assess the drug release rate of Ald-BMS-NPs, an Ald-BMS-NPs solution (1 mg/mL) was placed inside a 2000 Da dialysis bag, which was then immersed in physiological saline (pH = 7). The dialysis bag was kept at a constant temperature of 37 °C with stirring at 80 × g. At various time points (2, 6, 12, 18, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, and 96 h), 50 μL of solution was withdrawn from the dialysis bag and mixed with 450 μL of acetonitrile. The BMS concentration in the samples was analyzed using HPLC (SHIMADZU, LC-20ADxr).

In vitro HA binding affinity

Mix Ald-BMS-NPs and PLGA-BMS-NPs with nano-hydroxyapatite (HA, Aladdin, China) by stirring at room temperature for 12 h. Subsequently, centrifuge the mixture to remove unbound HA and collect the supernatant for TEM scanning.

In vivo biodistribution using IVIS and IVIM

Administer 100 μL of Ald-BMS-Cy5-NPs and PLGA-BMS-Cy5-NPs into the peritoneal cavity of 10-week-old female C57/BL/6 J mice. Post-injection, anesthetize the mice at 6 h, 12 h, and 24 h for whole-body fluorescence distribution imaging using IVIS (IVIS Spectrum, Korea). Subsequently, while the mouse is still under anesthesia, dissect the tibia and capture the fluorescence within the bone marrow using IVIM (IVIM, Korea).

Metabolism marker testing of liver and kidney

Adjust the serum dilution accordingly, configure the necessary parameters on the automated biochemical analyzer (Chemray 240, Chemray 420, and Chemray 800), load the samples, and initiate the automated measurement process.

Statistical & Reproducibility

Data are presented as mean ± SEM, with sample sizes specified in the figure legends. All measurements were taken from distinct samples. In vivo experiments utilized 5 to 10 mice per condition, with randomization and blinding applied to group allocation. In vitro experiments included at least three independent replicates, and no data were excluded. Statistical significance was defined as a P-value ≤ 0.05. All statistical analyses were carried out using GraphPad Prism 8 software.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Source data

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (81970761 to H.R.T., 82174033 to Y.W., T2350710233 to B.S.), Shenzhen Science and Technology Major project of China (KJZD20240903102759061 to H.R.T), National Key R&D Program of China (2024YFF206402 to B.S.) and Shenzhen Science and Technology Key Program (JCYJ20220818101404009 to B.S.).

Author contributions

Conceptualization, Q.X., H.R.T. and Y.W., Methodology, Q.X., X.F.D., J.H.L., Y.N.S., Y.F.L., and T.L., Investigation, T.L.W., Validation and Data Curation, Q.X., X.F.D, Z.J.H., and Z.K.K., Resources, B.S., Writing – Original Draft, Q.X., X.F.D and Y.W.; Writing – Review & Editing, Q.X., X.F.D; Supervision, H.R.T.; Funding Acquisition, H.R.T., Y.W. and B.S.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks Lindsay McDermott, and the other, anonymous, reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

All data presented in the manuscript and all uncropped blots in figures are provided in the Excel file as the Source Data file, which is linked to this manuscript. The RNA-seq raw data were uploaded publicly in the GEO datasets via GSE273951. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Qian Xie, Xiangfu Du.

Contributor Information

Qian Xie, Email: xqqx1996@163.com.

Tailin Wu, Email: tl_spine@163.com.

Yan Wang, Email: yan.wang@siat.ac.cn.

Huiren Tao, Email: huiren_tao@163.com.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-59719-w.

References

- 1.Neer, R. M. et al. Effect of parathyroid hormone (1-34) on fractures and bone mineral density in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. N. Engl. J. Med.344, 1434–1441 (2001). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ebeling, P. R. et al. Secondary Osteoporosis. Endocr. Rev.43, 240–313 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Watts, N. B. Postmenopausal Osteoporosis: A Clinical Review. J. Women’s Health27, 1093–1096 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wade, S. W., Strader, C., Fitzpatrick, L. A., Anthony, M. S. & O’Malley, C. D. Estimating prevalence of osteoporosis: examples from industrialized countries. Arch. Osteoporos.9, 182 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reginster, J. Y. & Burlet, N. Osteoporosis: A still increasing prevalence. Bone38, 4–9 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wysham, K. D., Baker, J. F. & Shoback, D. M. Osteoporosis and fractures in rheumatoid arthritis. Curr. Opin. Rheumatol.33, 270–276 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hofbauer, L. C., Brueck, C. C., Singh, S. K. & Dobnig, H. Osteoporosis in patients with diabetes mellitus. J. Bone Miner. Res.22, 1317–1328 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Canalis, E., Mazziotti, G., Giustina, A. & Bilezikian, J. P. Glucocorticoid-induced osteoporosis: pathophysiology and therapy. Osteoporos. Int.18, 1319–1328 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Langdahl, B., Ferrari, S. & Dempster, D. W. Bone modeling and remodeling: potential as therapeutic targets for the treatment of osteoporosis. Therapeutic Adv. Musculoskelet. Dis.8, 225–235 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gallagher, J. C. & Sai, A. J. Molecular biology of bone remodeling: Implications for new therapeutic targets for osteoporosis. Maturitas65, 301–307 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gurban, C. V. et al. Bone turnover markers in postmenopausal osteoporosis and their correlation with bone mineral density and menopause duration. Rom. J. Morphol. Embryol.60, 1127–1135 (2019). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fardellone, P., Salawati, E., Le Monnier, L. & Goëb, V. Bone Loss, Osteoporosis, and Fractures in Patients with Rheumatoid Arthritis: A Review. J. Clin. Med.9. 10.3390/jcm9103361 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Ma, Y. F. L. et al. Teriparatide increases bone formation in modeling and remodeling osteons and enhances IGF-II immunoreactivity in postmenopausal women with osteoporosis. J. Bone Miner. Res.21, 855–864 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.D’Amelio, P. et al. Alendronate reduces osteoclast precursors in osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int.21, 1741–1750 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.McClung, M. et al. Alendronate prevents postmenopausal bone loss in women without osteoporosis - A double-blind, randomized, controlled trial. Ann. Intern. Med.128, 253 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sutton, E. E. & Riche, D. M. Denosumab, a RANK Ligand Inhibitor, for Postmenopausal Women with Osteoporosis. Ann. Pharmacother.46, 1000–1009 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Aki, S. et al. Gastrointestinal side effect profile due to the use of alendronate in the treatment of osteoporosis. Yonsei Med. J.44, 961–967 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Deng, X. et al. Histidine decarboxylase-stimulating and inflammatory effects of alendronate in mice:: Involvement of mevalonate pathway, TNFα, macrophages, and T-cells. Int. Immunopharmacol.7, 152–161 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yilmaz, M., Taninmis, H., Kara, E., Ozagari, A. & Unsal, A. Nephrotic syndrome after oral bisphosphonate (alendronate) administration in a patient with osteoporosis. Osteoporos. Int.23, 2059–2062 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zhivodernikov, I. V., Kirichenko, T. V., Markina, Y. V., Postnov, A. Y. & Markin, A. M. Molecular and Cellular Mechanisms of Osteoporosis. Int. J. Mol. Sci.24, 10.3390/ijms242115772 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Furuhashi, M. Fatty Acid-Binding Protein 4 in Cardiovascular and Metabolic Diseases. J. Atherosclerosis Thrombosis26, 216–232 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Miao, L. et al. FABP4 deactivates NF-κB-IL1α pathway by ubiquitinating ATPB in tumor-associated macrophages and promotes neuroblastoma progression. Clin. Transl. Med.11, 10.1002/ctm2.395 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 23.Rodríguez-Calvo, R. et al. Fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4) as a potential biomarker reflecting myocardial lipid storage in type 2 diabetes. Metab.-Clin. Exp.96, 12–21 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang, K. Y. et al. Identification of Andrographolide as a novel FABP4 inhibitor for osteoarthritis treatment. Phytomedicine11810.1016/j.phymed.2023.154939 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 25.Cerezo, L. A. et al. The level of fatty acid-binding protein 4, a novel adipokine, is increased in rheumatoid arthritis and correlates with serum cholesterol levels. Cytokine64, 441–447 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gormez, S. et al. Relationships between visceral/subcutaneous adipose tissue FABP4 expression and coronary atherosclerosis in patients with metabolic syndrome. Cardiovasc. Pathol.46, 10.1016/j.carpath.2019.107192 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 27.Guo, D. et al. FABP4 secreted by M1-polarized macrophages promotes synovitis and angiogenesis to exacerbate rheumatoid arthritis. Bone Res.10, 10.1038/s41413-022-00211-2 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Tang, W. Z. et al. Targeting Kindlin-2 in adipocytes increases bone mass through inhibiting FAS/PPARg/FABP4 signaling in mice. Acta Pharmaceutica Sin. B13, 4535–4552 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Li, C. J. et al. MicroRNA-188 regulates age-related switch between osteoblast and adipocyte differentiation. J. Clin. Investig.125, 1509–1522 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Beekman, K. M. et al. Osteoporosis and Bone Marrow Adipose Tissue. Curr. Osteoporos. Rep.21, 45–55 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kreja, L., Liedert, A., Schmidt, C., Claes, L. & Ignatius, A. Influence of receptor activator of nuclear factor (NF)-κB ligand (RANKL), macrophage-colony stimulating factor (M-CSF) and fetal calf serum on human osteoclast formation and activity. J. Mol. Histol.38, 341–345 (2007). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Karakas, S. E., Almario, R. U. & Kim, K. Serum fatty acid binding protein 4, free fatty acids, and metabolic risk markers. Metab.-Clin. Exp.58, 1002–1007 (2009). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kajiya, H. In Calcium Signaling Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology (ed M. S. Islam) Vol. 740, 917–932 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 34.Bai, H. et al. TRPV2-induced Ca2+-calcineurin-NFAT signaling regulates differentiation of osteoclast in multiple myeloma. Cell Commun. Signal.16, 10.1186/s12964-018-0280-8 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 35.Asagiri, M. & Takayanagi, H. The molecular understanding of osteoclast differentiation. Bone40, 251–264 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Uhlen, M. et al. Tissue-based map of the human proteome. Science347, 10.1126/science.1260419 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Lee, M. Y. K. et al. Chronic administration of BMS309403 improves endothelial function in apolipoprotein E-deficient mice and in cultured human endothelial cells. Br. J. Pharmacol.162, 1564–1576 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Swami, A. et al. Engineered nanomedicine for myeloma and bone microenvironment targeting. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA111, 10287–10292 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sun, X. D. et al. Alendronate-functionalized polymeric micelles target icaritin to bone for mitigating osteoporosis in a rat model. J. Controlled Release376, 37–51 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Chen, Q. C. et al. Bone Targeted Delivery of SDF-1 via Alendronate Functionalized Nanoparticles in Guiding Stem Cell Migration. Acs Appl. Mater. Interfaces10, 23700–23710 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Li, Y. J., Meng, Y. & Yu, X. J. The Unique Metabolic Characteristics of Bone Marrow Adipose Tissue. Front. Endocrinol.10, 10.3389/fendo.2019.00069 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Wang, B., Wang, H., Li, Y. C. & Song, L. Lipid metabolism within the bone micro-environment is closely associated with bone metabolism in physiological and pathophysiological stages. Lipids Health Dis.21, 10.1186/s12944-021-01615-5 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 43.Baggio, B. Fatty acids, calcium and bone metabolism. J. Nephrol.15, 601–604 (2002). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Makovey, J., Chen, J. S., Hayward, C., Williams, F. M. K. & Sambrook, P. N. Association between serum cholesterol and bone mineral density. Bone44, 208–213 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chen, X. X. & Yang, T. F. Roles of leptin in bone metabolism and bone diseases. J. Bone Miner. Metab.33, 474–485 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kanazawa, I. Adiponectin in Metabolic Bone Disease. Curr. Medicinal Chem.19, 5481–5492 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cho, E. S. et al. The Effects of Rosiglitazone on Osteoblastic Differentiation, Osteoclast Formation and Bone Resorption. Molecules Cells33, 173–181 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shah, P. & Mudaliar, S. Pioglitazone: side effect and safety profile. Expert Opin. Drug Saf.9, 347–354 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Zeng, X. Z. et al. Artesunate suppresses RANKL-induced osteoclastogenesis through inhibition of PLCγ1-Ca2+-NFATc1 signaling pathway and prevents ovariectomy-induced bone loss. Biochemical Pharmacol.124, 57–68 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Pang, M. H. et al. AP-1 and Mitf interact with NFATc1 to stimulate cathepsin K promoter activity in osteoclast precursors. J. Cell. Biochem.120, 12382–12392 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Floresta, G., Patamia, V., Zagni, C. & Rescifina, A. Adipocyte fatty acid binding protein 4 (FABP4) inhibitors. An update from 2017 to early 2022. Eur. J. Medicinal Chem.240, 114604 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Su, H. X. et al. Exploration of Fragment Binding Poses Leading to Efficient Discovery of Highly Potent and Orally Effective Inhibitors of FABP4 for Anti-inflammation. J. Medicinal Chem.63, 4090–4106 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Boehm, O. et al. Clinical chemistry reference database for Wistar rats and C57/BL6 mice. Biol. Chem.388, 547–554 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data presented in the manuscript and all uncropped blots in figures are provided in the Excel file as the Source Data file, which is linked to this manuscript. The RNA-seq raw data were uploaded publicly in the GEO datasets via GSE273951. Source data are provided with this paper.