Abstract

In this study, a new magnesium(II) porphyrazine derivative tetrasubstituted with dicarboxypyrrolyl moieties was synthesized. Two different approaches were used, utilizing conventional heating and microwave irradiation. The developed three-step processes were compared showing the superior performance of the microwave-assisted organic synthesis. The new macrocycle and the novel maleonitrile derivatives were characterized using spectral techniques (mass spectrometry, NMR spectroscopy, UV-Vis spectrophotometry) and the ability of the porphyrazine to generate singlet oxygen assessed using the method with 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran. The singlet oxygen generation quantum yields were found to be moderate (ΦΔ = 0.23 and 0.22 in DMF and DMSO, respectively) and no aggregation behavior was noted in a series of dilutions. Additionally, the acute toxicity test using Microtox was performed showing almost no toxicity at the concentration of 10− 5 mol/L. The electrochemical studies revealed three redox processes of targeted porphyrazine with low first oxidation peak, whereas the spectroelectrochemistry showed the formation of both cationic and anionic species at proper potentials.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-00428-1.

Keywords: Microwave-assisted organic synthesis; Singlet oxygen; Porphyrazine; Diaminomaleonitrile; Electrochemistry, aminoporphyrazines

Subject terms: Microwave chemistry, Chemistry, Electrochemistry

Introduction

Tetraazaporphyrins (porphyrazines, Pzs) are porphyrin analogues with meso nitrogen atoms instead of carbon atoms. This causes significant structural and electronic changes in the macrocycle1. The unsubstituted porphyrazine ring is poorly soluble and prone to aggregation, which alters its unique features, most notably it quenches its photochemical properties. Thus, considerable effort is being devoted to modify the porphyrazine macrocycle. In this context, two main approaches may be distinguished: introduction of a metal cation into the Pz coordinating center and/or peripheral substitution. In recent years, various Pzs substituted in the β-positions with nitrogen2–4, and sulfur5–7 residues or rings connected to both β-positions8–10 have been synthesized by various methods. Aminoporphyrazines represent a fascinating class of compounds characterized by one-of-a-kind structural features and versatile properties. These nitrogen-rich macrocycles have attracted much interest in recent years due to their potential applications in such diverse fields as electrochemical conversion11,12, photonics13,14, and biomedicine15,16. The incorporation of amine groups into the porphyrazine structure not only improves its solubility and stability but also facilitates its functionalization. Aminoporphyrazines have found potential applications as photosensitizers in biomedicine17,18, as cutting-edge components in materials chemistry (including nanotechnology, electrophotography, optical data acquisition systems, electronic devices, photovoltaic cells, fuel cells, and electrochromic displays)19,20, and as constituents of devices designed for analytical applications (metal ion probes, electrocatalysts)21,22. Their popularity might be ascribed to low price and easy access to diaminomaleonitrile, which is their main precursor. Concurrently, pyrrole is a particular motif that often appears in molecules with biological and pharmacological activity. Pyrrole rings are found in many drugs that have anticancer activity (leukemia, lymphoma, myelofibrosis), or are used in the treatment of inflammation, tuberculosis, psychosis, anxiety, as well as infections, caused by viruses, bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and malaria. In this respect, probably the best-known drugs sharing the pyrrolic motif that are clinically used in the treatment of dyslipidemia and prevention of circulatory system diseases are atorvastatin or fluvastatin23–25.

Currently, as humanity we are facing the ongoing human-induced climate change26. To reverse this trend or at least to decelerate its rate, the term ‘green chemistry’ was formed along with its twelve principles27. In this regard use of microwave irradiation instead of classical heating is widely employed to make the chemistry more green and sustainable. Microwave-assisted organic synthesis (MAOS) offers reduced reaction times, improved reaction yields, as well as improved selectivity and increased purity of the synthesized product28,29. As such, MAOS is deemed as a more cost- and energy-efficient alternative to conventional heating. Regardless of these advantages, application of MAOS is currently superficially studied in the case of porphyrazine chemistry. The scarce publications on this subject report the isolated cases of MAOS of precursors of Pzs, a few Pzs itself, and modifications thereof30–33, which generally highlight the improved yields and reduced reaction times as compared to the classical synthetic methods.

Taking all of the above into account, the aim of this study was to prepare new pyrrole-substituted porphyrazine derivatives and to develop a more sustainable microwave-assisted synthesis pathway. New porphyrazine was synthesized using both MAOS and classical methods, which were then compared to each other in terms of – most notably – reaction times and yields. A three-step process involved the synthesis of two new maleonitrile derivatives and one porphyrazine derivative. The new porphyrazine was subjected to physicochemical characterization (mass spectrometry, NMR spectroscopy, UV-Vis spectrophotometry and spectrofluorimetry), as well as to photochemical studies and acute toxicity assessment using the Microtox test.

Results and discussion

Synthesis and characterization

The synthesis of new compounds was carried out using two synthetic methods. First method was classical synthesis. Diaminomaleonitrile 1 was subjected to Paal-Knorr reaction with diethyl 2,3-diacetylsuccinate and oxalic acid in methanol34 to give derivative 2. The Paal-Knorr reaction proceeds according to the nucleophilic addition mechanism, in the first step the nucleophile of the amine attacks the 1,4-dione derivative, which is followed by the cyclization and elimination of the water molecule35 The reaction mixture was stirred under reflux for 24 h. Next, 2 was methylated with (CH3O)2SO22 in the presence of NaH to give derivative 336. In the final step maleonitrile derivative 3 was used in tetracyclization reaction using Linstead conditions36 resulting in the formation of porphyrazine 4. Apart from macrocyclization reaction, transesterification occurred, leading to buthyl ester groups in porphyrazine. The mechanism of the Linstead macrocyclization reaction proceeds via a rather complex multistep-scheme. At first, the nitrile groups (-CN) in the maleonitrile derivative undergo nucleophilic attack by metal species, which leads to the formation of cyclic imine (C = NH) intermediates. Next, intermediates react further, forming a tetrameric macrocyclic intermediate and the metal ion template inducing the ring closure, promoting the correct orientation37.

The second used method was Microwave-Assisted Organic Synthesis (MAOS). Similarly as in the classical synthesis, diaminomaleonitrile 1 was used in Paal-Knorr reaction with diethyl 2,3-diacetylsuccinate, oxalic acid in methanol but the applied temperature was considerably higher (120 °C) thanks to increased pressure, which ultimately enabled to finish the reaction after 10 min38. The maleonitrile derivative 2, isolated using column flash chromatography, was used in the alkylation reaction with iodomethane in the presence of cesium carbonate in THF using MAOS (120 °C, 20 min) to give derivative 3. Subsequent use of MAOS for the Linstead macrocyclization36, with magnesium n-butoxide as a base in n-butanol, shortened the reaction time to just 8 min and led to magnesium(II) porphyrazine 4 (Fig. 1). All newly synthetized compounds were fully characterized by mass spectrometry (Supporting information, Figure S16-S18), 1H, 13C1H-1H COSY, 1H-13C HSQC and 1H-13C HMBC NMR spectroscopy (Supporting information, Figure S1-S15), UV-Vis spectrophotometry and melting point determination. The structure of Pz 4 was resolved by NMR data (Fig. 2).

Fig. 1.

Synthetic pathway leading to porphyrazine 4. Conditions and reagents: classical synthesis: (i) methanol, reflux, 24 h; (ii) NaH, THF, (CH3O)2SO2, − 17 °C to room temperature; (iii) magnesium(II) butoxide, n-butanol, reflux, 20 h; microwave-assisted organic synthesis: (i) methanol, 120 °C, 10 min; (ii) MeI, Cs2CO3, THF, 120 °C, 20 min; (iii) magnesium(II) butoxide, n-butanol, 180 °C, 8 min.

Fig. 2.

The structure of Pz 4, with NMR chemical shifts in ppm (italic font indicates carbon chemical shifts). The arrows indicate correlations observed in the 1H-13C HMBC spectrum.

The comparison of the applied synthesis methods leads to some interesting findings (Table 1). By using MAOS, in each of the cases it is possible not only to shorten the reaction times from hours to minutes, but it is also accompanied by a significant increase in the amount of product isolated, with almost 50% increase in the yield of the porphyrazine 4 (increase from 19 to 28%). One should however be cautious comparing both reactions for maleonitrile derivative 3, as different conditions and methylating agents were used due to the danger of hydrogen release from NaH in the microwave reactor. All of these are in agreement with the literature findings39.

Table 1.

Summary of the reactions performed in the synthetic pathway leading to porphyrazine 4.

| Synthesized compound | Overall reaction time | Reaction temperature | Isolated yields (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2 | 24 h | 65 °C | 73 |

| 2 (MAOS) | 10 min | 120 °C | 95 |

| 3 a | 5 h | −17 °C to rt | 68 |

| 3 (MAOS)b | 20 min | 120 °C | 84 |

| 4 | 20 h | 118 °C | 19 |

| 4 (MAOS) | 8 min | 180 °C | 28 |

a – NaH, THF, (CH3O)2SO2; b – MeI, Cs2CO3, THF. MAOS – microwave-assisted organic synthesis; rt – room temperature.

Electrochemical and spectroelectrochemical studies

Cyclic (CV) and differential pulse (DPV) voltammetries were employed to investigate porphyrazine 4 with peripheral dibutyl-(3,4-dicarboxylate)pyrrolyl and dimethylamino substituents in terms of the electroactivity of its π-conjugated system and the determination of oxidation and reduction potentials of macrocycle. Measurements were conducted in previously deoxygenated DCM containing 0.1 M tetrabutylammonium perchlorate (TBAP) as the supporting electrolyte. To assess the presence of diffusion-controlled processes, the CV scans were obtained at the scan rate range of 50–250 mV/s. Within the applied electrochemical window of − 1.5 V to + 1.3 V, the targeted macrocyclic compound revealed 3 redox pairs - one reduction at − 1.76 V and two oxidations at − 0.19 V and 0.30 V, respectively (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

CV and DPV voltammograms of 4 at different scan rates in 0.1 M TBAP/DCM. DPV parameters: modulation amplitude 20 mV, step rate 10 mV/s.

In porphyrinoids that contain an electrochemically inactive metal ion center, such as Mg2+ or Zn2+, all redox processes involve ligand-centered reactions. Oxidation results in the formation of π-cation radicals, while reduction leads to π-anion radicals38,40,41. Since the oxidation ipa/ipc values are close to unity, these processes can be classified as single-electron transfers. Additionally, the ΔEp values of the oxidation peaks indicate their reversible nature, and the cyclic voltammetry CV data for compound 4 suggest that all oxidation reactions are diffusion-controlled. The findings reveal that the synthesized porphyrazine undergoes oxidation relatively easily, with the first redox couple observed at − 0.19 V versus Fc⁺/Fc. This behavior is attributed to the presence of peripheral dimethylamine groups directly attached to the porphyrazine core, which are known for their strong electron-donating effects. These groups promote the formation of π-cation radicals, significantly lowering the oxidation potential—a trend previously observed in other amino-substituted porphyrazines42,43. The recorded data, using the Fc⁺/Fc reduction couple as an internal reference, are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Electrochemical data of the obtained magnesium(II) porphyrazines 4.

| Red(Pz− 1/Pz) | Oxd1(Pz/Pz+ 1) | Oxd2(Pz+ 1/Pz+ 2) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| E 1/2 [V] vs. Fc/ + Fc | −1.76a | −0.19 | 0.30 |

| ΔE p [mV] | – | 50 | 59 |

| i pa /i pc [V] | – | 0.88 | 1.34 |

a Estimated on DPV.

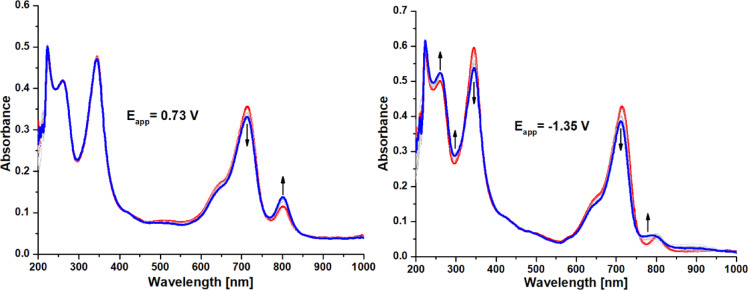

UV-Vis spectroscopy serves as a valuable tool for analyzing redox reactions, providing insight into the electronic structures of porphyrinoid ligands and their coordinated metal cations. To investigate the formation of anionic and cationic species in compound 4, in situ spectroelectrochemical measurements were conducted. During controlled oxidation at 0.73 V, changes in the UV-Vis spectra showed a decrease in the Q-band intensity at approximately 714 nm without any shift, along with the emergence of a new band around 801 nm and an isosbestic point near 750 nm (Fig. 4). These red-shifted bands have previously been associated with the cationic forms of porphyrazines [Pz]⁺44. Notably, no alterations were detected in the Soret band under positive potential conditions. A similar reduction in the Q-band was observed at − 1.35 V; however, only minor spectral changes were noted around 800 nm at this negative potential. In contrast, a significant decrease in the Soret band at 345 nm was recorded, likely indicating the formation of the anionic form of porphyrazine.

Fig. 4.

UV-Vis spectra of 4 in 0.1 M TBAP/DCM at Eapp= 0.73 V (left), Eapp = − 1.35 V (right). Red spectra were recorded without potential, whereas the blue ones appeared after 120 s of proper potential was applied.

Absorption and emission properties

Absorption and emission properties of 4 were studied in N,N-dimethylformamide (DMF) and dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO) as solvents, results are summarized in Table 3. Absorbances of the series of solutions of 4 obey the Beer-Lambert law (Fig. 5).

Table 3.

Summary of photophysical properties of 4 in solution.

| Parameter | Solvent used | |

|---|---|---|

| DMF | DMSO | |

| ΦΔ | 0.23 | 0.22 |

| ΦF | 0.036 | 0.043 |

| absorption maxima λmax [nm], (molar absorption coefficients - log ε [M− 1·cm− 1]) | 725 (5.19), 522 (4.23), 347 (5.15) | 732 (4.95), 528 (4.00), 348 (4.89) |

| emission maximum λF [nm] | 742 | 752 |

| Stokes shift [cm− 1] | 316 | 362 |

Fig. 5.

UV-Vis spectra of 4 in (a) DMF and (b) DMSO at different concentrations (left), and correlation between concentration and absorbance at wavelength corresponding to the absorption peaks (right).

Q band of the Pz is not split or accompanied by a longer-wavelength band or shoulder. Thus, we conclude that introduction of ester groups to the pyrrolyl moiety prevents aggregation observed previously for phenyl-pyrrolyl Pz analogues45. The Q and B (Soret) bands are the result of π→π* transitions, respectively S0→S1 and S0→S2, while the less intense band at ~ 520 nm can be assigned to n→π* transitions7,46,47. Q-bands are accompanied by the vibronic shoulder, around 660 nm. Fluorescence quantum yields are similar to those observed previously for pyrrolyl Pzs34,48,38,45,49, and no emission from S2 state was observed, in contrast to our previous work45 (Fig. 6). Small Stokes shift indicate little difference in molecular geometry in its ground S0 and excited S1 states (Table 3).

Fig. 6.

Absorption, emission and excitation spectra of Pz 4 in (a) DMF and (b) DMSO.

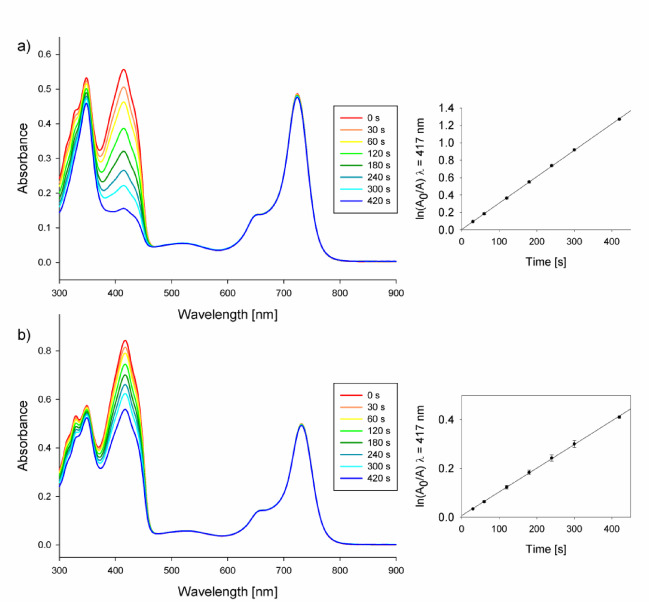

Singlet oxygen generation measurements

Singlet oxygen quantum yields of 4 were determined in DMF and DMSO as solvents, using zinc(II) phthalocyanine (ZnPc) as a reference and 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran as a singlet oxygen quencher (Fig. 7). Singlet oxygen quantum yield were found to be moderate (ΦΔ = 0.23 and 0.22 in DMF and DMSO, respectively) (Table 3) and are similar to values of other non-aggregating magnesium(II) Pzs34,48,38,45,49.

Fig. 7.

Changes in the UV-Vis spectrum, corresponding to different irradiation times for the mixture of 4 and DPBF in DMF (a) and DMSO (b).

Acute toxicity assessment using Microtox test

The synthesized porphyrazine was subjected to Microtox acute toxicity test. The basis of it is the monitoring of the change of the bioluminescent of the bacteria, Aliivibrio fischeri, which is proportional to the sample toxicity50. The intensity of light emitted by the bacteria is recorded just before the addition of the sample and after 5 and 15 min thereafter. The results of the experiment are presented in the Fig. 8.

Fig. 8.

The changes in A. fischeri bioluminescence as a function of Pz 4 concentration.

Based on the results, it can be seen that the toxicity increases as the concentration of 4 increases. The concentration of 10− 5 M (10 µM) is almost non-toxic, oscillating around 20%, which is an arbitrary threshold for toxicity determination in this test51. As for the higher tested concentration, 10− 4 M (100 µM), the toxicity towards the bacteria is much more pronounced, as a decrease of around 80% bioluminescence can be seen. These results suggests that for in-depth antimicrobial experiments a lower concentration might be more suitable to avoid dark toxicity of the photosensitizer.

Conclusion

New derivatives possessing pyrrole dicarboxylate groups were obtained by classical synthesis methods and MAOS. MAOS proved to be a faster and more efficient method, in the case of porphyrazine 4 the reaction time was reduced from 24 h to 8 min, and the yield increased from 19 to 28%. Spectral techniques, especially 1D and 2D NMR techniques, and MS were applied for the characterization of all compounds. In addition, macrocycle Pz 4 was subjected to photophysical and photochemical studies, in DMF and DMSO as solvents. No aggregation in the studied concentration range was found, Pz was characterized to have low fluorescence and moderate singlet oxygen generation quantum yield. Additionally, a spectroelectochemical study was performed. Then, the ecotoxicity of the macrocycle was tested.

Porphyrazine was tested for singlet oxygen generation. Additionally, electrochemical and spectroelectochemical studies were performed in DCM/0.1 M TBAP. Three redox pairs were observed, pairs, 4 showed its first oxidation shifted towards lower potential due to the presence of electron-donating dimethylamino groups. Moreover, at positive potential applied, the targeted compound revealed the formation of cationic species as new red-shifted band occurred at approx. 801 nm. Similar changes were observed when negative potential was applied indicating anionic forms of the macrocyclic ring. Then, the acute toxicity of the macrocycle was tested using the Microtox test, which indicated non-toxicity of 4 at the concentration of 10− 5 M in the dark conditions, suggesting it might be a suitable derivative to serve as a photosensitizer in subsequent photodynamic therapy evaluation.

Experimental section

General procedures

All reactions were conducted in oven-dried glassware under argon. All solvents were rotary evaporated at or below 50°C. Reaction temperatures are reported as set in Heidolph Hei-Plate Mix’n’ Heat using heating blocks. Microwave syntheses were performed with Anton-Paar Monowave 400 and Anton-Paar Monowave 400R. Solvents and all reagents were obtained from commercial suppliers and used without further purification. Melting points were obtained on a “Stuart” Bibby Scientific SMP10 and are uncorrected. Dry flash column chromatography was carried out on Merck silica gel 60, particle size 40–63 μm. Thin-layer chromatography (TLC) was performed on silica gel 60 A F254 plates and visualized with UV (λmax 254–365 nm). UV-Vis spectra were recorded on a Hitachi UV-Vis U-1900 spectrometer; λmax (logε), nm. Mass spectra (ES, MALDI TOF) were carried out by the Wielkopolska Centre for Advanced Technologies in Poznan. 1H NMR,13C NMR spectra were recorded using Bruker AvanceCore 400 and Agilent DD2 800 spectrometers. Data were processed and analyzed with Topspin 4.3 or MestReNova 9.0 software. Chemical shifts (δ) are quoted in parts per million (ppm) and are referred to the residual solvent peak (DMSO-d6: 2.50 ppm in 1H NMR and 39.51 ppm in 13C NMR; CDCl3: 7.24 ppm in 1H NMR and 77.23 ppm in 13C NMR; pyridine-d5: 8.74, 7.58, and 7.22 ppm in1H NMR and 150.35, 135.91, and 123.87 in 13C NMR). Coupling constants (J) are quoted in Hertz (Hz). The abbreviations s, t, q, and m refer to singlet, triplet, quartet, and multiplet, respectively.

Electrochemical measurements

Electrochemical experiments were carried out using the Metrohm Autolab PGSTAT128N potentiostat controlled by a PC for data acquisition and storage, driven by Metrohm Nova 2.1.4 software. Measurements were made in dichloromethane with a glassy carbon (GC) working electrode (3 mm, area = 0.02 cm2, Ag wire as a pseudo-reference electrode, and a platinum wire as a counter electrode. Prior to the electrochemical experiments, the GC electrode was polished with an aqueous 50 nm Al2O3 slurry (provided by Sigma-Aldrich) on a polishing cloth, followed by subsequent washing in an ultrasonic bath with water/acetone mixture (1:1, v/v) for 10 min in order to remove organic and inorganic impurities. Ferrocene (Sigma-Aldrich) was used as an internal standard. Before each measurement, a glass cell (volume 10 mL) containing dichloromethane with a supporting electrolyte (0.1 M tetrabutylammonium perchlorate, TBAP) was deoxygenated by purging nitrogen gas for 15 min. All electrochemical experiments were carried out at ambient laboratory temperature. DCM and TBAP were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich.

Spectroelectrochemical measurements

Spectroelectrochemical studies were performed with the use of the Ocean Optics USB 2000 + XR1-ES diode array spectrophotometer and Metrohm Autolab PGSTAT128N potentiostat. Measurements were made in a 2 mm path length quartz cuvette with the use of a Pt gauze working electrode, a Ag/AgCl as a reference, and a platinum wire as an auxiliary electrode in deoxygenated DCM/0.1 M TBAP solution. Absorbance spectra were recorded in the range of 400–1000 nm within 2 min (every 10 s) during application of proper overpotential.

Fluorescence measurements

A Jasco 6200 spectrofluorometer with Spectra Manager version 1.55 was used for the recording of the emission spectra. Measurements were made at ambient temperature, using 1 cm path length quartz cuvettes. The diluted solutions (absorbances were kept below 0.1) of porphyrazine and unsubstituted zinc(II) phthalocyanine used as a reference were excited at λ = 630 nm. The fluorescence quantum yields ΦF were calculated according to the equation:

|

where F is the area under the emission curve for the sample (Fs) and the reference (Fr), A is the absorbance at the excitation wavelength for the sample (As) and the reference (Ar), and ΦFr is the fluorescence quantum yield of the reference (ΦFr = 0.17 and 0.20 in DMF and DMSO, respectively)52,53.

Singlet oxygen generation quantum yields measurements

The assessment of singlet oxygen generation quantum yield for the porphyrazine was performed in DMF solution under air conditions at ambient temperature. 1,3-Diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF, Sigma-Aldrich) was used as a chemical quencher of singlet oxygen. The chemical quencher and photosensitizer mixture was irradiated with light of wavelength adjusted to the maximum absorbance of the macrocycle. Unsubstituted zinc(II) phthalocyanine with known singlet oxygen quantum yields (0.56 in DMF, 0.67 in DMSO) was used as a reference52,53. The decrease of absorbance was monitored at 417 nm under light irradiation. The rate at which the quencher degrade is related to the generation of singlet oxygen.

Microtox acute toxicity test

The synthesized porphyrazine 4 was subjected to Microtox 81.9% Screening test according to the ISO 11348-3:2007 standard54. Briefly, the bioluminescence of a suspension of Aliivibrio fischeri bacteria was recorded, after which an aqueous solution of 4 was added and the changes in bioluminescence assessed after 5 and 15 min. For the measurements, Microtox M500 was used with MicrotoxOmni 4.2 software. Due to insolubility of the porphyrazine in water, an addition of DMSO was used for solubilisation (final concentration of DMSO was below 1% v/v).

Synthetic procedures

Diethyl 1-[(Z)-2-amino-1,2-dicyanoethenyl]-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrole-3,4-dicarboxylate (2)

Classical synthesis:

Diethyl 2,3-diacetylsuccinate (1356 mg, 5.25 mmol), diaminomaleonitrile (540 mg, 5 mmol) and oxalic acid (90 mg, 1 mmol) were refluxed in methanol (50 mL) for 24 h. Then, solvent was evaporated and a solid residue was subjected to flash column chromatography in dichloromethane leading to 2 (1204 mg, 73% yield).

Microwave-assisted synthesis.

DAMN 1 (540 mg, 5 mmol), diethyl 2,3-diacetylsuccinate (1356 mg, 5.25 mmol), oxalic acid (90 mg, 1 mmol) and methanol (2 mL) were placed in a glass tube (G10) and sealed with a silicone septum. The tube was put into the microwave reactor. The reaction conditions were as follows: heating to 120 °C, next maintaining the reaction temperature for 10 min, and finally cooling to 55 °C. Contents of the vial were evaporated. The purification of the crude residue by flash column chromatography with dichloromethane as eluent led to 2 (1570 mg, 95% yield).

Mp 241 °C (dec). Rf 0.08 (CH2Cl2:CH3OH 35:1). UV-Vis (CH2Cl2): λmax, nm (logε) 266 (4.2). 1H NMR (800 MHz; DMSO-d6): δH, ppm, 8.27, (s, 2 H), 4.18–4.15 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 4 H), 2.21 (s, 6 H), 1.23 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 6 H) 13C NMR (200 MHz; DMSO-d6): δC ppm, 167.0, 164.1, 134.1, 132.8, 84.1, 61.6, 59.8, 57.3, 30.1, 14.1, 13.7, 10.4. MS ES m/z 331 [M + H+]. HRMS m/z found: 331.1388 [M + H]+ C16H19N4O4 requires 331.1406 [M + H]+.

Diethyl 1-[(Z)-1,2-dicyano-2-(dimethylamino)ethenyl]-2,5-dimetyl-1H-pyrrole-3,4-dicarboxylate (3)

Classical synthesis:

Sodium hydride (60% dispersion in mineral oil, 44 mg, 1.1 mmol) was suspended in THF (15 mL) at (− 17 °C). Next 2 (330 mg, 1.00 mmol) in THF (2 mL) was added and stirring was continued for 30 min at temperature (− 15 °C). After that (CH3O)2SO2 (130 µL, 1.1 mmol) in THF (2 mL) was added dropwise for 30 min at (− 10 °C) and the reaction mixture was stirred at room temperature for another 4 h. The reaction was carefully quenched by adding water (2 mL), after which the reaction mixture was poured into ice-water mixture (100 mL). The resulting yellow solid precipitate was filtrated to give 3 (243 mg, 68% yield).

Microwave-assisted synthesis.

Maleonitrile 2 (330 mg, 1 mmol), iodomethane (186 µL, 3 mmol), cesium carbonate (325 mg, 1 mmol) and THF (2 mL) were placed in a glass tube (G10) and sealed with a silicone septum. The tube was put into the microwave reactor. The reaction conditions were as follows: heating to 120 °C, next maintaining the reaction temperature for 20 min, and finally cooling to 70 °C. The purification of the crude reaction residue by flash column chromatography in dichloromethane led to 3 (301 mg, 84% yield).

Mp 88–89 °C. Rf 0.27 (CH2Cl2:CH3OH 50:1). UV-Vis (CH2Cl2): λmax, nm (logε) 317 (4.11). 1H NMR (400 MHz; CDCl3): δH, ppm, 4.27–4.22 (q, J = 7.1 Hz, 4 H), 3.37 (s, 4 H), 2.81 (s, 2 H), 2.35 (s, 6 H), 1.32–1.28 (t, J = 7.1 Hz, 6 H) 13C NMR (100 MHz; CDCl3): δC, ppm, 165.0, 164.7 136.70 135.7, 135.1, 133.2, 115.8, 114.4, 114.2, 109.8 85.0 60.6, 60.4, 43.2, 42.1, 14.3, 14.2, 11.5, 11.3. MS ES m/z 359 [M + H+]. HRMS m/z found: 359.1695 [M + H]+ C18H23N4O4 requires 359.1719 [M + H]+.

2,7,12,17-Tetrakis[dibutyl(3,4-dicarboxylate)-2,5-dimethyl-1H-pyrrolyl]-3,8,13,18-tetrakis(dimethylamino)porphyrazinato]magnesium(II) (4)

Classical synthesis:

Mg turnings (36 mg, 1.50 mmol), a crystal of I2, and 1-butanol (20 mL) were heated under reflux for 6 h. After cooling to room temperature, maleonitrile derivative 3 (1075 mg, 3.00 mmol) was added to the reaction mixture and further heating under reflux for 20 h was applied. Next, the dark green reaction mixture was cooled to room temperature, filtered through Celite and the filtrate evaporated to dryness. The crude residue was purified by column flash chromatography (CH2Cl2:CH3OH, 50:1; n-hexane: EtOAc, 7:3) leading to 4 (240 mg, 19% yield).

Microwave-assisted synthesis.

Maleonitrile 3 (1075 mg, 3 mmol), freshly prepared magnesium butoxide (225 mg, 1,5 mmol), and n-butanol (2 mL) were placed in a glass tube (G10) and sealed with a silicone septum. The tube was put into the microwave reactor. The reaction conditions were as follows: heating to 180 °C, next maintaining the temperature for 8 min, and finally cooling to 70 °C. The purification of the crude residue using column flash chromatography (CH2Cl2:CH3OH, 50:1; n-hexane: EtOAc, 7:3) led to 4 (352 mg, 28% yield).

Mp 196–197 °C. Rf 0.1 (CH2Cl2:CH3OH 35:1). UV-Vis (CH2Cl2): λmax, nm (logε) 262 (4.73), 345 (4.83), 515 (4.08), 720 (4.73). 1H NMR (800 MHz; Pyridine-d5): δH, ppm, 4.55–4.52 (m, 16 H), 3.62. (s, 24 H), 2.56 (s, 24 H), 1.85–1.83 (m, 16 H), 1.55–1.52 (m, 16 H), 0.97 (t, J = 7.4 Hz, 24 H) 13C NMR (200 MHz; Pyridine-d5): δC ppm, 166.7, 154.3, 151.3, 150.7, 149.3, 138.2, 136.2, 124.2, 114.4, 108.9, 64.8, 43.0, 32.0, 20.2, 14.3, 13.0. MALDI TOF m/z 1681 [M + H+]. HRMS m/z found: 1681.8956 [M + H]+ C88H121MgN16O16 requires 1681.8997 [M + H]+.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The Authors thank Mrs Beata Kwiatkowska and Mrs Rita Kuba for their excellent technical support. This work was carried out with the support of the Center of Innovative Pharmaceutical Technology at the Poznan University of Medical Sciences. Anton Paar Monowave 400R was acquired with the help of the ProScience fund provided by Poznan University of Medical Sciences. This research was funded by PUMS statutory fund No. JAK0000056.

Author contributions

Author Contributions: Conceptualization W.S; methodology, W.S., T.K., L.P., M.K. and D.M.; investigation, W.S., T.K., D.M., L.P., M.K. and E.Z.; resources, W.S.; writing—original draft preparation, W.S., T.K., D.M. and M.K.; writing-review and editing, W.S and D.M.; supervision, W.S.; project administration, W.S; funding acquisition, W.S. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Data availability

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Stuzhin, P. A. & Ercolani, C. Porphyrazines with annulated heterocycles. in The Porphyrin Handbook 263–364 (Elsevier, 10.1016/B978-0-08-092389-5.50011-0. (2003).

- 2.Fuchter, M. J. et al. ROM Polymerization-Capture-Release strategy for the Chromatography-Free synthesis of novel unsymmetrical porphyrazines. J. Org. Chem.70, 2793–2802 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mani, N. S. et al. Synthesis and characterisation of porphyrazinoctamine derivatives: X-ray crystallographic studies of [2,3,7,8,12,13,17,18-octakis(dibenzylamino)- porphyrazinato]magnesium(II) and {2,3,7,8,12,13,17,18-octakis[allyl(benzyl)amino]- porphyrazinato} nickel(II). J. Chem. Soc., Chem. Commun. (1994) (2095). 10.1039/c39940002095

- 4.Fuchter, M. J. et al. Synthesis of porphyrazine-octaamine, hexamine and Diamine derivatives. Tetrahedron61, 6115–6130 (2005). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leng, F., Wang, X., Jin, L. & Yin, B. The synthesis and properties of unsymmetrical porphyrazines annulated with a tetrathiafulvalene bearing two tetraethylene glycol units. Dyes Pigm.87, 89–94 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Falkowski, M. et al. Manganese Sulfanyl Porphyrazine–MWCNT nanohybrid electrode material as a catalyst for H2O2 and glucose biosensors. Sensors24, 6257 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hassani, M. et al. Synthesis, electrochemical and photochemical properties of Sulfanyl porphyrazine with Ferrocenyl substituents. Molecules28, 5215 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Stuzhin, P. A. et al. Tetrakis(1,2,5-thiadiazolo)porphyrazines. 9. Synthesis and spectral and theoretical studies of the lithium(i) complex and its unusual behaviour in Aprotic solvents in the presence of acids. Dalton Trans.48, 14049–14061 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donzello, M. P. et al. Porphyrazines with annulated Diazepine rings. 2. Alternative synthetic route to Tetrakis-2,3-(5,7-diphenyl-1,4-diazepino)porphyrazines: new metal complexes, general physicochemical data, Ultraviolet – Visible linear and optical limiting behavior, and electrochemical and spectroelectrochemical properties. J. Am. Chem. Soc.125, 14190–14204 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Beduoğlu, A., Sevim, A. M., Koca, A., Altındal, A. & Bayır, Z. A. Thiazole-substituted non-symmetrical metallophthalocyanines: Synthesis, characterization, electrochemical and heavy metal ion sensing properties. New. J. Chem.44, 5201–5210 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hsu, C. W., Chiang, C. J., Liu, K. Y., Chen, T. H. & Chen, H. L. Efficient screening of single-atom Porphyrazine-coordinated transition metal catalysts for electrochemical nitric oxide reduction: Insights from first-principles calculations. Appl. Surf. Sci.681, 161439 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Zhou, W., Tan, R., Yang, C., Zhang, B. & Deng, K. Selective oxidation of benzyl alcohols photocatalyzed by asymmetric Cobalt thioporphyrazine supported on alumina. Mol. Catal.569, 114608 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wieczorek, E. et al. Magnesium porphyrazine with peripheral Methyl (3,5-dibromophenylmethyl)amino groups – synthesis and optical properties: Dedicated to the memory of professor Franciszek Sączewski. Heterocycl. Commun.25, 1–7 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Belashov, A. V. et al. Multifunctional cyanoaryl porphyrazine pigments with push-pull structure of macrocycle framing: Photophysics and possible applications. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A. 458, 115964 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pinheiro, P. A. et al. Modulating the phototoxicity and selectivity of a porphyrazine towards epidermal tumor cells by coordination with metal ions. Photochem. Photobiol Sci.23, 1757–1769 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wysocki, M. et al. Porphyrazine/phthalocyanine hybrid complexes – Antibacterial and anticancer photodynamic and sonodynamic activity. Synth. Met.299, 117474 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sobotta, L. et al. Optical properties of a series of pyrrolyl-substituted porphyrazines and their photoinactivation potential against Enterococcus faecalis after incorporation into liposomes. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A. 368, 104–109 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Redkin, T. S. et al. Dendritic cells pulsed with tumor lysates induced by Tetracyanotetra(aryl)porphyrazines-Based photodynamic therapy effectively trigger Anti-Tumor immunity in an orthotopic mouse glioma model. Pharmaceutics15, 2430 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fahim, A. M., Magar, H. S., Nasar, E., Abdelrazek, F. M. & Aboelnaga, A. Synthesis of Cu-Porphyrazines by annulated Diazepine rings with electrochemical, conductance activities and computational studies. J. Inorg. Organomet. Polym.32, 240–266 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang, D. et al. Photoelectrocatalytic degradation of partially hydrolyzed polyacrylamide using a novel particle electrode. RSC Adv.7, 55496–55503 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goslinski, T. et al. Experimental and computational study on the reactivity of 2,3-bis[(3-pyridylmethyl)amino]-2(Z)-butene-1,4-dinitrile, a key intermediate for the synthesis of Tribenzoporphyrazine bearing peripheral methyl(3-pyridylmethyl)amino substituents. Monatsh Chem.142, 599–608 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Szczolko, W., Chornovolenko, K., Kujawski, J., Dutkiewicz, Z. & Koczorowski, T. Magnesium(II) porphyrazine with thiophenylmethylene Groups-Synthesis, electrochemical characterization, UV–Visible Titration with palladium ions, and density functional theory calculations. Molecules29, 3610 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rao, H. S. P., Jothilingam, S. & Scheeren, H. W. Microwave mediated facile one-pot synthesis of polyarylpyrroles from but-2-ene- and but-2-yne-1,4-diones. Tetrahedron60, 1625–1630 (2004). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bhardwaj, V., Gumber, D., Abbot, V., Dhiman, S. & Sharma, P. Pyrrole: a resourceful small molecule in key medicinal hetero-aromatics. RSC Adv.5, 15233–15266 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Li Petri, G. et al. Bioactive pyrrole-based compounds with target selectivity. Eur. J. Med. Chem.208, 112783 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Forster, P. M. et al. Indicators of global climate change 2023: Annual update of key indicators of the state of the climate system and human influence. Earth Syst. Sci. Data. 16, 2625–2658 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ivanković, A. Review of 12 principles of green chemistry in practice. IJSGE6, 39 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 28.De La Hoz, A., Díaz-Ortiz, A. & Prieto, P. Microwave-assisted green organic synthesis. in Alternative Energy Sources for Green Chemistry (eds. Stefanidis, G. & Stankiewicz, A.) 1–33The Royal Society of Chemistry, (2016). 10.1039/9781782623632-00001

- 29.Gawande, M. B., Shelke, S. N., Zboril, R. & Varma, R. S. Microwave-Assisted chemistry: Synthetic applications for rapid assembly of nanomaterials and organics. Acc. Chem. Res.47, 1338–1348 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Löser, P., Winzenburg, A. & Faust, R. A perfluorous polyphenyl dendritic shell for the protection of a photosensitizing porphyrazine core. Chem. Commun.49, 9413 (2013). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Shaabani, A., Maleki-Moghaddam, R., Maleki, A. & Rezayan, A. H. Microwave assisted synthesis of metal-free phthalocyanine and metallophthalocyanines. Dyes Pigm.74, 279–282 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kantar, C., Şahin, Z. S., Büyükgüngör, O. & Şaşmaz, S. Microwave-assisted synthesis, characterization and spectral properties of non-peripherally tetra-substituted phthalocyanines containing Eugenol moieties. J. Mol. Struct.1089, 48–52 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Maleki, A. & Rezayan, A. H. One-Pot synthesis of Metallopyrazinoporphyrazines using 2,3-Diaminomaleonitrile and 1,2-Dicarbonyl compounds accelerated by microwave irradiation. Org. Chem. Int.2014, 1–5 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 34.Szczolko, W. et al. The Suzuki cross-coupling reaction for the synthesis of porphyrazine possessing bulky 2,5-(biphenyl-4-yl)pyrrol-1-yl substituents in the periphery. Polyhedron102, 462–468 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Amarnath, V. et al. Intermediates in the Paal-Knorr synthesis of pyrroles. J. Org. Chem.56, 6924–6931 (1991). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Linstead, R. P. & Whalley, M. 944. Conjugated macrocylces. Part XXII. Tetrazaporphin and its metallic derivatives. J. Chem. Soc. 4839 (1952). 10.1039/jr9520004839

- 37.Oliver, S. W. & Smith, T. D. Oligomeric cyclization of dinitriles in the synthesis of phthalocyanines and related compounds: The role of the alkoxide anion. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans.2 157910.1039/p29870001579 (1987).

- 38.Szczolko, W. et al. Porphyrazines with bulky peripheral pyrrolyl substituents – Synthesis via microwave-assisted Suzuki-Miyaura cross-coupling reaction, optical and electrochemical properties. Dyes Pigm.206, 110607 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lidström, P., Tierney, J., Wathey, B. & Westman, J. Microwave assisted organic synthesis—a review. Tetrahedron57, 9225–9283 (2001). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tuncer, S., Koca, A., Gül, A. & Avcıata, U. 1,4-Dithiaheterocycle-fused porphyrazines: Synthesis, characterization, voltammetric and spectroelectrochemical properties. Dyes Pigm.81, 144–151 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 41.Uslu Kobak, R. Z., Öztürk, E. S., Koca, A. & Gül, A. The synthesis and cyclotetramerisation reactions of aryloxy-, arylalkyloxy-substituted pyrazine-2,3-dicarbonitriles and spectroelectrochemical properties of octakis(hexyloxy)-pyrazinoporphyrazine. Dyes Pigm.86, 115–122 (2010). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Eichhorn, D. M. et al. [60]Fullerene and TCNQ donor–acceptor crystals of octakis(dimethylamino) porphyrazine. J. Chem. Soc. Chem. Commun. 1703–1704. 10.1039/C39950001703 (1995).

- 43.Lange, S. J., Nie, H., Stern, C. L., Barrett, A. G. M. & Hoffman, B. M. Peripheral Palladium(II) and Platinum(II) complexes of Bis(dimethylamino)porphyrazine. Inorg. Chem.37, 6435–6443 (1998). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Yaraşir, M. N., Koca, A., Kandaz, M. & Salih, B. Voltammetry and spectroelectrochemical behavior of a novel Octapropylporphyrazinato Lead(II) complex. J. Phys. Chem. C. 111, 16558–16563 (2007). [Google Scholar]

- 45.Szczolko, W. et al. Magnesium(II) porphyrazine with peripherally overloaded pyrrolyl substituents – Synthesis, optical and electrochemical characterization. J. Mol. Struct.1318, 139356 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tao, W. et al. The origin of the unusual broad and intense visible absorption of tetrathiafulvalene-annulated zinc porphyrazine: A density functional theory study. J. Mol. Graph. Model.33, 26–34 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Goslinski, T. et al. Synthesis and characterization of periphery-functionalized porphyrazines containing mixed pyrrolyl and pyridylmethylamino groups. J. Porphyrins Phthalocyanines. 13, 223–234 (2009). [Google Scholar]

- 48.Szczolko, W. et al. X-ray and NMR structural studies of the series of porphyrazines with peripheral pyrrolyl groups. Inorg. Chim. Acta. 484, 368–374 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 49.Koczorowski, T. et al. Influence of bulky pyrrolyl substitent on the physicochemical properties of porphyrazines. Dyes Pigm.112, 138–144 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Johnson, B. T. Microtox® Toxicity Test System — New Developments and Applications. in Microscale Testing in Aquatic Toxicology 201–218CRC Press, Boca Raton, (2018). 10.1201/9780203747193-14

- 51.Krakowiak, R. et al. Titanium(IV) oxide nanoparticles functionalized with various meso-porphyrins for efficient photocatalytic degradation of ibuprofen in UV and visible light. J. Environ. Chem. Eng.10, 108432 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ogunsipe, A., Maree, D. & Nyokong, T. Solvent effects on the photochemical and fluorescence properties of zinc phthalocyanine derivatives. J. Mol. Struct.650, 131–140 (2003). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Sobotta, L. et al. Functional singlet oxygen generators based on porphyrazines with peripheral 2,5-dimethylpyrrol-1-yl and dimethylamino groups. J. Photochem. Photobiol., A. 269, 9–16 (2013). [Google Scholar]

- 54.ISO 11348-3:2007. ISOhttps://www.iso.org/standard/40518.html

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.