Abstract

A 34-year-old man became aware of an erythematous nodule on the left nasal wing. He was treated with topical steroids and oral antibacterial agents at his local doctor, but his condition did not improve, and he was referred to our hospital. A skin biopsy revealed diffuse cellular infiltration through the dermis. No epidermotropism was seen. The major infiltrate was small to medium-sized lymphoid cells. The number of CD3+ cells was almost the same as that of CD20+ cells, while CD4+ cells were dominant over CD8+ cells. Atypical lymphocytes were positive for BCL6 and PD-1. Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of immunoglobulin heavy chain and T-cell receptor gene rearrangements on paraffin-embedded tissue sections revealed a clonal expansion of T-cells. The patient was diagnosed as having primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder (PCSM-LPD) and treated with fludroxycortide tape. The red nodule completely disappeared after three months. Nuclear staining for nuclear factor of activated T-cells c1 (NFATc1), which had been suggested to be useful in distinguishing PCSM-LPD from pseudolymphoma, was negative in our case.

Our case was considered to be typical of PCSM-LPD among existing reports of PCSM-LPD from Japan, except for the young age of the patient. Our case suggested that young cases with PCSM-LPD may have been misdiagnosed with cutaneous pseudolymphoma (CPL), which may be one of the reasons why this type of lymphoproliferative disorder has been reported to occur in elderly people.

Keywords: bcl6, cutaneous pseudolymphoma, nuclear staining for nuclear factor of activated t-cells c1 (nfatc1), primary cutaneous cd4+ small/medium t-cell lymphoproliferative disorder (pcsm-lpd), programmed death 1 (pd-1), t-cell receptor gene rearrangement

Introduction

Primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder (PCSM-LPD) is synonymous with what used to be called primary cutaneous CD4-positive small- and medium-sized T-cell lymphoma, which has recently been renamed [1]. PCSM-LPD is characterized by nodules or plaques on the face, neck, and upper body [1]. Histology shows nodular or diffuse infiltration of CD4+ small to medium-sized T cells. The tumor cells are positive for follicular helper T-cell markers such as PD-1, BCL6, and CXCL13. The proliferation rate assessed by Ki-67 positivity is low, ranging from less than 5% to a maximum of 20% [1-5]. The male-to-female ratio of PCSM-LPD European patients was 1:1, and 91% of patients were said to be rash-free and mildly relieved within a median of 63 months. The median age of the disease onset in Europe is 53 years. The remaining 9% of patients survive with residual skin symptoms. PCSM-LPD often resolves spontaneously after skin biopsy but may be treated with topical steroids, surgery, or radiation therapy [6]. In the Japanese report, the male-to-female ratio of PCSM-LPD was 11:14 [7]. The median age was 61.5 years, older than that of Europeans. It was relatively rare, occurring in 25 (1.4%) of 1733 patients with cutaneous lymphoma diagnosed between 2007 and 2011 [7]. Here, we report a young patient with PCSM-LPD, who was successfully treated with occlusive topical steroid.

Case presentation

A 34-year-old man was referred to our hospital with a suspicion of cutaneous lymphoma. The patient noticed a red nodule on the left nasal wing two months before. He visited his local doctor due to its gradual increase in size. He was treated with faropenem, topical bacitracin/fradiomycin sulfate, topical ketoconazole, and topical hydrocortisone butyrate, which were all ineffective. The nodule decreased in size while the patient took oral betamethasone, but it flared up when he stopped the drug. When the patient visited us, an erythematous nodule without ulceration was located on the left nasal wing (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Red nodule on the left wing of the nose at the first visit.

The skin biopsy specimen showed diffuse cellular infiltration through the dermis (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Hematoxylin and eosin stain shows significant cellular infiltration of the dermis (x40).

No epidermotropism was seen. The major infiltrate was small to medium-sized lymphoid cells (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Cells infiltrating the dermis in hematoxylin and eosin stain are small to medium-sized lymphoid cells (x400).

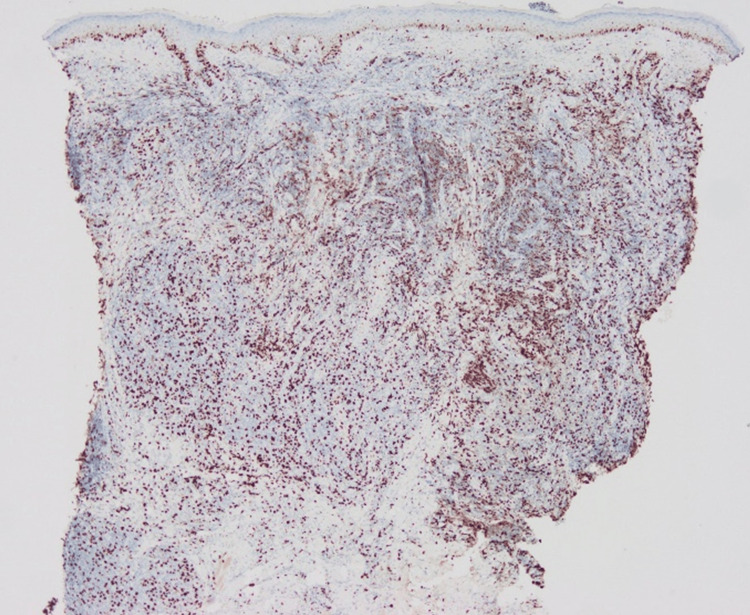

The number of CD3+ cells was almost the same as that of CD20+ cells, while CD4+ cells were dominant over CD8+ cells (Figures 4-7).

Figure 4. Immunohistological staining for CD3.

Figure 5. Immunohistological staining for CD4.

Figure 6. Immunohistological staining for CD8.

Figure 7. Immunohistological staining for CD20.

The ratio of Ki-67+ cells was about 20% (Figure 8).

Figure 8. Immunohistological staining for Ki-67.

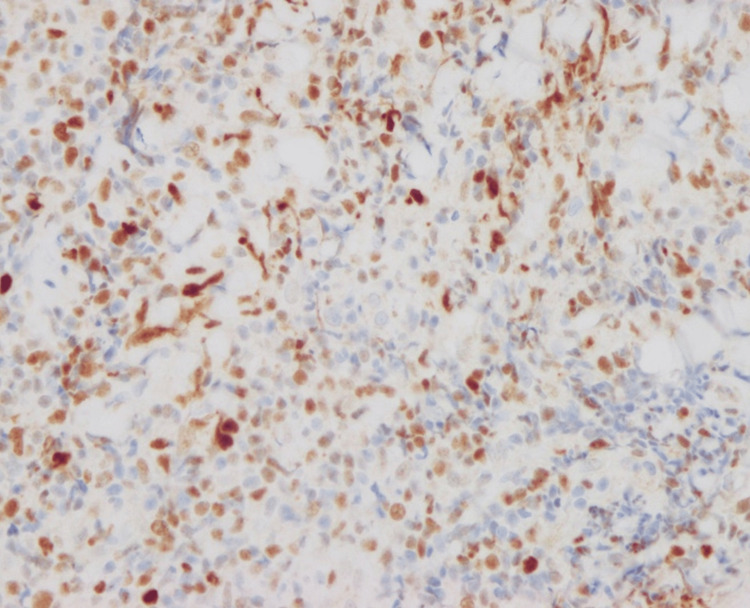

Atypical lymphocytes were positive for BCL6 and PD-1 (Figures 9, 10).

Figure 9. Immunohistological staining for BCL6.

Figure 10. Immunohistological staining for PD-1.

Polymerase chain reaction (PCR) analysis of immunoglobulin heavy chain and T-cell receptor gene rearrangements on paraffin-embedded tissue sections revealed a clonal expansion of T-cells. CT scanning showed no extracutaneous lesions. The patient was diagnosed as PCSM-LPD and treated with fludroxycortide tape. The red nodule completely disappeared after three months (Figure 11).

Figure 11. Red nodule on left wing of nose completely disappeared after three months.

Discussion

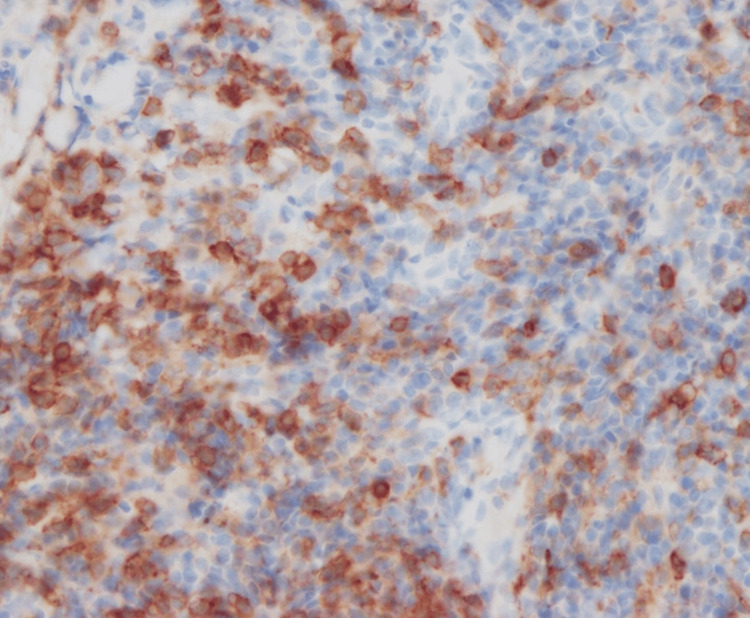

A solitary red nodule on the nose with histologically dense lymphocytic infiltration is commonly seen. The diagnosis may be either cutaneous pseudolymphoma (CPL), lymphocytoma cutis, lymphadenosis benigna cutis, or cutaneous lymphoid hyperplasia, all of which refer to the same benign process mimicking lymphoma. CPL may occur at any age. It is not always easy to distinguish between CPL and PCSM-LPD. The latter is a better fit for our case because of the very high CD4+/CD8+ ratio, positivity of follicular helper T-cell makers, and clonal T-cell proliferation. Nuclear staining for nuclear factor of activated T-cells c1 (NFATc1) was reported to be a key finding of PCSM-LPD [8]. We performed additional staining for NFATc1. Unlike a previous study [8], NFATc1 was negative (Figure 12).

Figure 12. Nuclear staining for nuclear factor of activated T-cells c1 (NFATc1) in this case.

In a previous study [8], the cytoplasm was stained; however, in the present case (as shown in the image), the cytoplasm is not stained.

A case report of PCSM-LPD in a 33-year-old woman was reported as a young case of PCSM-LPD from Japan [9]. However, this report is considered atypical for PCSM-LPD because of the high Ki-67 (40%) and negative T cell receptor gene rearrangements [9]. Another case report from Japan is that of a 52-year-old patient [10]. He was diagnosed as PCSM-LPD, but his CD30-positive status and aggressive course also made this case atypical for PCSM-LPD [10].

Conclusions

We experienced a young Japanese case of PCSM-LPD. This case was considered typical for PCSM-LPD, except for the fact that the patient was young. Our case suggested that young cases with PCSM-LPD may have been misdiagnosed with CPL, which may be one of the reasons why this type of lymphoproliferative disorder has been reported to occur in elderly people.

In addition, NFATc1 was not stained by either PCSM-LPD or CPL. Further investigation may be needed to determine if NFATc1 can be used to differentiate PCSM-LPD from CPL.

Disclosures

Human subjects: Consent for treatment and open access publication was obtained or waived by all participants in this study. Insitutional Review Board, International University of Health and Welfare, Japan issued approval 20-Nr-009. The authors obtained the necessary written in-force consent to report the case.

Conflicts of interest: In compliance with the ICMJE uniform disclosure form, all authors declare the following:

Payment/services info: All authors have declared that no financial support was received from any organization for the submitted work.

Financial relationships: All authors have declared that they have no financial relationships at present or within the previous three years with any organizations that might have an interest in the submitted work.

Other relationships: All authors have declared that there are no other relationships or activities that could appear to have influenced the submitted work.

Author Contributions

Concept and design: Yuta Norimatsu, Mina Komuta, Yuichiro Hayashi, Kennosuke Karube, Makoto Sugaya

Acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data: Yuta Norimatsu, Mina Komuta, Yuichiro Hayashi, Kennosuke Karube, Makoto Sugaya

Drafting of the manuscript: Yuta Norimatsu, Makoto Sugaya

Critical review of the manuscript for important intellectual content: Yuta Norimatsu, Mina Komuta, Yuichiro Hayashi, Kennosuke Karube, Makoto Sugaya

Supervision: Yuta Norimatsu, Makoto Sugaya

References

- 1.The 2018 update of the WHO-EORTC classification for primary cutaneous lymphomas. Willemze R, Cerroni L, Kempf W, Berti E, Facchetti F, Swerdlow SH, Jaffe ES. Blood. 2019;133:1703–1714. doi: 10.1182/blood-2018-11-881268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Primary cutaneous T-cell lymphomas other than mycosis fungoides and Sézary syndrome. Part I: clinical and histologic features and diagnosis. Stoll JR, Willner J, Oh Y, et al. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:1073–1090. doi: 10.1016/j.jaad.2021.04.080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma expresses follicular T-cell markers. Rodríguez Pinilla SM, Roncador G, Rodríguez-Peralto JL, et al. Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33:81–90. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31818e52fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Epstein-Barr virus negative clonal plasma cell proliferations and lymphomas in peripheral T-cell lymphomas: a phenomenon with distinctive clinicopathologic features. Balagué O, Martínez A, Colomo L, et al. Am J Surg Pathol. 2007;31:1310–1322. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e3180339f18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Expression of programmed death-1 in primary cutaneous CD4-positive small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma, cutaneous pseudo-T-cell lymphoma, and other types of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma. Cetinözman F, Jansen PM, Willemze R. Am J Surg Pathol. 2012;36:109–116. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e318230df87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Primary cutaneous CD4+ small-/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma: a cutaneous nodular proliferation of pleomorphic T lymphocytes of undetermined significance? A study of 136 cases. Beltraminelli H, Leinweber B, Kerl H, Cerroni L. Am J Dermatopathol. 2009;31:317–322. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0b013e31819f19bb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cutaneous lymphoma in Japan, 2012-2017: a nationwide study. Fujii K, Hamada T, Shimauchi T, Asai J, Fujisawa Y, Ihn H, Katoh N. J Dermatol Sci. 2020;97:187–193. doi: 10.1016/j.jdermsci.2020.01.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Differential NFATc1 expression in primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium-sized pleomorphic T-cell lymphoma and other forms of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma and pseudolymphoma. Magro CM, Momtahen S. Am J Dermatopathol. 2017;39:95–103. doi: 10.1097/DAD.0000000000000597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Primary cutaneous CD4(+) small/medium T-cell lymphoproliferative disorder with high Ki-67 proliferation index. Takei I, Kawai K, Nakajima M, Ansai O, Anan T. J Dermatol. 2021;48:0–4. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.15821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Primary cutaneous CD4+ small/medium T-cell lymphoma with aggressive clinical course. Yasuda M, Igarashi N, Nagai Y, Tamura A, Ishikawa O. Australas J Dermatol. 2014;55:304–306. doi: 10.1111/ajd.12208. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]