Abstract

Background

A large body of research has focused on investigating the effects of healthcare provider volume and specialization on patient outcomes including outcomes of colorectal cancer surgery. However there is conflicting evidence about the role of such healthcare provider characteristics in the management of colorectal cancer.

Objectives

To examine the available literature for the effects of hospital volume, surgeon caseload and specialization on the outcomes of colorectal, colon and rectal cancer surgery.

Search methods

We searched Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), and LILACS using free text search words (as well as MESH‐terms). We also searched Medline (January 1990‐September 2011), Embase (January 1990‐September 2011) and registers of clinical trials, abstracts of scientific meetings, reference lists of included studies and contacted experts in the field.

Selection criteria

Non‐randomised and observational studies that compared outcomes for colorectal cancer, colon cancer and rectal cancer surgery (overall 5‐year survival, five year disease specific survival, operative mortality, 5‐year local recurrence rate, anastomotic leak rate, permanent stoma rate and abdominoperineal excision of the rectum rate) between high volume/specialist hospitals and surgeons and low volume/specialist hospitals and surgeons.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently abstracted data and assessed risk of bias in included studies. Results were pooled using the random effects model in unadjusted and case‐mix adjusted meta‐analyses.

Main results

Overall five year survival was significantly improved for patients with colorectal cancer treated in high‐volume hospitals (HR=0.90, 95% CI 0.85 to 0.96), by high‐volume surgeons (HR=0.88, 95% CI 0.83 to 0.93) and colorectal specialists (HR=0.81, 95% CI 0.71 to 0.94). Operative mortality was significantly better for high‐volume surgeons (OR=0.77, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.91) and specialists (OR=0.74, 95% CI 0.60 to 0.91), but there was no significant association with higher hospital caseload (OR=0.93, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.04) when only case‐mix adjusted studies were included. There were differences in the effects of caseload depending on the level of case‐mix adjustment and also whether the studies originated in the US or in other countries. For rectal cancer, there was a significant association between high‐volume hospitals and improved 5‐year survival (HR=0.85, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.93), but not with operative mortality (OR=0.97, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.33); surgeon caseload had no significant association with either 5‐year survival (HR=0.99, 95% CI 0.86 to 1.14) or operative mortality (OR=0.86, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.19) when case‐mix adjusted studies were reviewed. Higher hospital volume was associated with significantly lower rates of permanent stomas (OR=0.64, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.90) and APER (OR=0.55, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.72). High‐volume surgeons and specialists also achieved lower rates of permanent stoma formation (0.75, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.88) and (0.70, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.94, respectively).

Authors' conclusions

The results confirm clearly the presence of a volume‐outcome relationship in colorectal cancer surgery, based on hospital and surgeon caseload, and specialisation. The volume‐outcome relationship appears somewhat stronger for the individual surgeon than for the hospital; particularly for overall 5‐year survival and operative mortality, there were differences between US and non‐US data, suggesting provider variability at hospital level between different countries, making it imperative that every country or healthcare system must establish audit systems to guide changes in the service provision based on local data, and facilitate centralisation of services as required. Overall quality of the evidence was low as all included studies were observational by design. In addition there were discrepancies in the definitions of caseload and colorectal specialist. However ethical challenges associated with the conception of randomised controlled trials addressing the volume outcome relationship makes this the best available evidence.

Keywords: Humans; Colonic Neoplasms; Colonic Neoplasms/mortality; Colonic Neoplasms/surgery; Colorectal Neoplasms; Colorectal Neoplasms/mortality; Colorectal Neoplasms/surgery; Colorectal Surgery; Colorectal Surgery/mortality; Colorectal Surgery/statistics & numerical data; Hospitals; Hospitals/statistics & numerical data; Outcome Assessment, Health Care; Outcome Assessment, Health Care/statistics & numerical data; Rectal Neoplasms; Rectal Neoplasms/mortality; Rectal Neoplasms/surgery; Risk Adjustment; Surgical Stomas; Surgical Stomas/statistics & numerical data; Survival Analysis; Workload; Workload/statistics & numerical data

Plain language summary

Workload and surgeon´s speciality for outcome after colorectal cancer surgery

There is some evidence to suggest better patient outcomes with increasing healthcare provider volume in complex cancer surgery. At present, healthcare providers are unsure of this relationship for colorectal cancer patients and there are mixed views on the concentration of such services to higher volume institutions. Some of the consequences of service centralization would include the loss of local healthcare provision for some patients, and the threat to financial viability of smaller hospitals often relying on a regular income from such a common condition. After thorough search of the available literature, we found fifty‐four observational studies (fifty one meta‐analysed) including 943,728 patients that addressed either the volume‐outcome relationship in the context of modern colorectal cancer treatment, or the effects of surgeon specialization. The results confirm the presence of a volume‐outcome relationship in colorectal cancer surgery, based on hospital and surgeon caseload, and benefits for specialization. For death within five years of treatment, hospital volume appeared to be more beneficial in rectal cancer surgery than for colon cancer. However, international differences in the data suggest provider variability at the hospital level between the different countries, making it imperative that every country or healthcare system must establish audit systems to guide changes in the service provision based on local data, and facilitate centralization of services as required. Overall quality of the evidence was low as all included studies were observational by design. In addition there were discrepancies in the definitions of caseload and colorectal specialist. However ethical challenges associated with the conception of randomised controlled trials addressing the volume outcome relationship makes this the best available evidence.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. Hospital volume and primary outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery (adjusted analyses).

| Hospital volume and primary outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery (adjusted analyses) | ||||||

| Population: Patients with outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery Settings: Elective and urgent procedures Intervention: High hospital volume | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | High hospital volume | |||||

| Overall five year survival ‐ Colorectal cancer | 494 per 1000 | 459 per 1000 (436 to 477) | HR 0.9 (0.84 to 0.95) | 36858 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

| Overall five year survival ‐ Colon cancer | 543 per 1000 | 532 per 1000 (453 to 615) | HR 0.97 (0.77 to 1.22) | 5211 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | |

| Overall five year survival ‐ Rectal cancer | 527 per 1000 | 471 per 1000 (438 to 509) | HR 0.85 (0.77 to 0.95) | 4028 (3 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| Inpatient and 30 day mortality ‐ Colorectal cancer | 53 per 1000 | 52 per 1000 (43 to 63) | OR 0.98 (0.79 to 1.2) | 77823 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

| Inpatient and 30 day mortality ‐ Colon cancer | 56 per 1000 | 50 per 1000 (44 to 57) | OR 0.89 (0.78 to 1.01) | 263071 (7 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

| Inpatient and 30 day mortality ‐ Rectal cancer | 54 per 1000 | 57 per 1000 (41 to 79) | OR 1.07 (0.76 to 1.5) | 14941 (5 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Unexplained heterogeneity 2 Study was high risk for 5 of ten items used to assess risk of bias

The following studies were not included in the table 1 because no data was published on number of patients experiencing the outcome and the total number of patients in either control or interventional group.

Simunovic 2000 , Elferink 2010A; Elferink 2010B; Manchon‐Walsh 2011)

Summary of findings 2. Hospital volume and secondary outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery (adjusted analyses).

| Hospital volume and secondary outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery (adjusted analyses) | ||||||

| Population: Patients with outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery Settings: Elective and urgent procedures Intervention: High hospital volume | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | High hospital volume | |||||

| Five year local recurrence rate ‐ Rectal cancer | 152 per 1000 | 119 per 1000 (81 to 174) | HR 0.77 (0.51 to 1.16) | 2986 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

| Anastomotic leak rate ‐ Colon cancer | 18 per 1000 | 26 per 1000 (14 to 45) | OR 1.44 (0.8 to 2.59) | 2808 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| Anastomotic leak rate ‐ Rectal cancer | 72 per 1000 | 53 per 1000 (36 to 78) | OR 0.72 (0.48 to 1.09) | 2615 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| Permanent stoma rate ‐ Rectal cancer | 371 per 1000 | 252 per 1000 (171 to 352) | OR 0.57 (0.35 to 0.92) | 7093 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

| Abdominoperineal excision of the rectum rate ‐ Rectal cancer | 463 per 1000 | 322 per 1000 (266 to 383) | OR 0.55 (0.42 to 0.72) | 894 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low2 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Unexplained heterogeneity 2 Study was high risk for 5 of ten items used to assess risk of bias

The following studies were not included in the table 2 because no data was published on the number of patients experiencing the outcome and the total number of patients in either control or interventional group.

Summary of findings 3. Surgeon volume and primary outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery (adjusted analyses).

| Surgeon volume and primary outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery (adjusted analyses) | ||||||

| Population: Patients with outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery Settings: Elective and urgent procedures Intervention: High surgeon volume | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | High surgeon volume | |||||

| Overall five year survival ‐ Colorectal cancer | 521 per 1000 | 473 per 1000 (453 to 492) | HR 0.87 (0.82 to 0.92) | 15462 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| Overall five year survival ‐ Colon cancer | 393 per 1000 | 343 per 1000 (316 to 371) | HR 0.84 (0.76 to 0.93) | 2905 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| Overall five year survival ‐ Rectal cancer | 428 per 1000 | 425 per 1000 (381 to 471) | HR 0.99 (0.86 to 1.14) | 1903 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| Five year disease specific survival ‐ Colorectal cancer | 659 per 1000 | 636 per 1000 (568 to 703) | HR 0.94 (0.78 to 1.13) | 1416 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| Inpatient and 30 day mortality ‐ Colon cancer | 49 per 1000 | 39 per 1000 (30 to 49) | OR 0.79 (0.61 to 1.02) | 47584 (3 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

| Inpatient and 30 day mortality ‐ Rectal cancer | 93 per 1000 | 75 per 1000 (50 to 111) | OR 0.79 (0.51 to 1.22) | 1903 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Unexplained heterogeneity

The following study was not included in the table 3 because no data was published on number of patients experiencing the outcome and the total number of patients in either control or interventional group.

Summary of findings 4. Surgeon volume and secondary outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery (adjusted analyses).

| Surgeon volume and secondary outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery (adjusted analyses) | ||||||

| Population: Patients with outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery Settings: Elective and urgent procedures Intervention: High surgeon volume | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | High surgeon volume | |||||

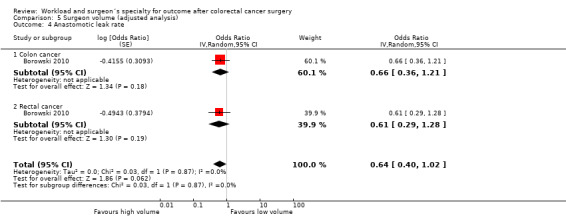

| Anastomotic leak rate ‐ Colon cancer | 27 per 1000 | 18 per 1000 (10 to 33) | OR 0.66 (0.36 to 1.21) | 2570 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| Anastomotic leak rate ‐ Rectal cancer | 93 per 1000 | 59 per 1000 (29 to 116) | OR 0.61 (0.29 to 1.28) | 1929 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| Permanent stoma rate ‐ Rectal cancer | 376 per 1000 | 282 per 1000 (217 to 354) | OR 0.65 (0.46 to 0.91) | 1323 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| Abdominoperineal excision of rectum rate ‐ Rectal cancer | 569 per 1000 | 209 per 1000 (117 to 346) | OR 0.2 (0.1 to 0.4) | 180 (1 study) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Four high risk and two unclear risk items out of ten 2 Total number of events less than 300 3 Large effect present, OR < 0.5

The following study was not included in the table 4 because no data was published on number of patients experiencing the outcome and the total number of patients in either control or interventional group.

Summary of findings 5. Surgeon specialisation and primary and secondary outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery (adjusted analyses).

| Surgeon specialisation and primary and secondary outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery (adjusted analyses) | ||||||

| Population: Patients with outcomes after colorectal cancer surgery Settings: Elective and urgent procedures Intervention: Surgeon specialisation | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of Participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| Control | Surgeon specialisation | |||||

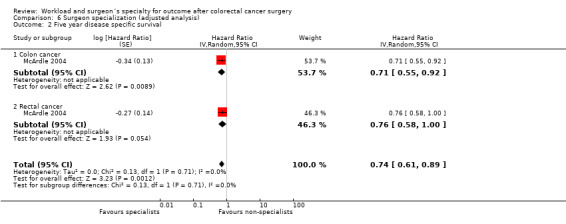

| Overall five year survival ‐ Colorectal cancer | 422 per 1000 | 359 per 1000 (323 to 403) | HR 0.81 (0.71 to 0.94) | 14628 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| Five year disease specific survival ‐ Colorectal cancer | 638 per 1000 | 529 per 1000 (467 to 591) | HR 0.74 (0.62 to 0.88) | 2186 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| Inpatient and 30 day mortality ‐ Colorectal cancer | 104 per 1000 | 79 per 1000 (65 to 95) | OR 0.74 (0.6 to 0.91) | 11973 (2 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| Five year local recurrence rate ‐ Colorectal cancer | 169 per 1000 | 99 per 1000 (78 to 123) | HR 0.56 (0.44 to 0.71) | 2587 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

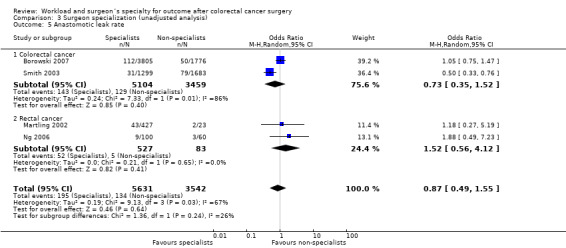

| Anastomotic leak rate ‐ Colorectal cancer | 37 per 1000 | 27 per 1000 (12 to 59) | OR 0.71 (0.31 to 1.63) | 8563 (2 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1 | |

| Permanent stoma rate ‐ Rectal cancer | 362 per 1000 | 285 per 1000 (231 to 348) | OR 0.7 (0.53 to 0.94) | 2026 (1 study) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: Confidence interval; OR: Odds ratio; HR: Hazard ratio; | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Significant unexplained heterogeneity between studies

Background

Description of the condition

Colorectal cancer is an important public health problem. It is the third most common cancer in the developed world (Globocan 2002), and the second most common cause of cancer death (Globocan 2002). Worldwide, approximately 875,000 people are newly diagnosed with colorectal cancer each year, with a four time greater incidence in developed countries compared to the developing world (Globocan 2002). In countries with the highest prevalence, as much as 6% of the population could suffer from the disease within their lifetime (Keating 2003; Skegg 2002).

Despite substantial advances in neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment, the mainstay of treatment for colorectal cancer remains surgery. Resection of the cancer alone may cure around 40% of cases (Wille‐Jørgensen 2001), with adjuvant or neo‐adjuvant treatment in the form of chemotherapy and pre‐operative chemo‐radiotherapy confers an additional survival benefit of 5‐6% (Midgley 2000). Overall, relative survival for colorectal cancer has improved over the last three decades (Verdecchia 2007), particularly attributed to improvements in treatments for rectal cancer (Verdecchia 2007). The mean age‐adjusted 5‐year relative survival in Europe is 55% and 53% for colon and rectal cancer, respectively, with women having slightly better survival than men for both cancers (Sant 2009). However, the recently published Eurocare‐4 data still highlights significant variability in the survival rates between many European countries (Sant 2009).

The outcomes of colorectal surgery can be evaluated in many ways. In the UK, quality benchmarks stated in the guidelines of the Association of Coloproctology of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI) (ACPGBI 2007) include 30‐day mortality, anastomotic leak rates, permanent stoma and Abdomino‐Perineal Excision (APER) rates, 5‐year local recurrence, and overall or cancer‐specific survival (ACPGBI 2007). Furthermore, in order to comparatively evaluate the quality of healthcare providers in observational studies, it is imperative to employ case‐mix adjusted outcomes (Hall 2009). Although most risk factors can be defined objectively, some have a subjective component which may result in inconsistencies for some preoperative variables (Ranta 1997; Haynes 1995), thus introducing bias.

Description of the intervention

A large body of research over the last two decades has focused on explaining the relationship between patient outcomes and volume of work undertaken by health providers. For many rare diseases, the concentration of patient care in the hand of specialist surgeons allows accumulation of experience with such infrequently seen conditions, with obvious benefits for the quality of treatment, training, research and economic efficiency. For more common diseases, the effects of service concentration on training and research are less pronounced, and economy of scale may be even counterproductive if the viability of smaller hospitals is threatened by the reduction of regular income streams. Nonetheless, if the patient's received quality of care is indeed determined by the experience and expertise of the treating surgeon and the whole treatment team, it is important to determine the responsible factors that enable high‐quality healthcare. Whilst it may be difficult to spot each individual intervention that leads to better outcomes, it has been long demonstrated that differences in results exist between providers, even for common conditions (Lee 1957; Lipworth 1963), and that caseload could indeed act as an important measure in comparative analysis (Luft 1979).

In recent times there has been a drive towards centralisation of cancer services based on the widely held assumption that specialists and high‐volume providers achieve better patient outcomes (Dudley 2000; Fong 2005; Ihse 2003). The benefits of higher caseload, although used for surgeons and hospitals often synonymously, may work through different pathways (Gruen 2009): for the high‐volume surgeon, it is thought that greater experience should lead to improvements in the pre‐ and intraoperative decision‐making process, case selection and surgical technique; for the high‐volume hospital, the organisation of care including multi‐disciplinary team work approach, local availability of other specialist services and more active involvement with research is thought to lead to the reported better results (Ihse 2003). An alternative hypothesis to the "practice‐makes‐perfect" concept, explaining at least some of the reported variability between high‐ and low‐volume providers, is that of "selective referral" patterns: the better outcome achieved by more widely known surgeons and centres may in itself result in high‐volume practice, and attract a better case‐mix from a larger population base (Luft 1987). As for the effects of specialisation, patient outcome may be improved not only through dedicated training and practice, and the associated in‐depth knowledge of surgical anatomy and pathology, but also through the concentration of workload resulting in high caseload itself (Chowdhury 2007).

Why it is important to do this review

Colorectal cancer surgery is traditionally performed both by general surgeons and trained colorectal specialists, and is provided in most acute hospitals. There have been conflicting reports regarding the "volume‐outcome relationship" in colorectal cancer surgery (Iversen 2007; Salz 2008); results from high volume centres in support of centralization have been criticised for trying to justify their own existence (Hogan 2009). Within any healthcare system, the outcome of the volume‐outcome debate has substantial implications for the structure and delivery of services for common conditions including colorectal cancer, as there is an inherent conflict between the retention of colorectal services in smaller, but local, hospital units with geographical advantages for many patients, and the concentration in large‐volume, regional units (Soljak 2002; Hogan 2009). Furthermore, the cost involved in developing and maintaining centralised care provision on a large scale is significant and can only be justified by evidence of improved patient outcome. As the treatment of colorectal cancer has evolved rapidly over the last two decades, with widespread introduction of pre‐operative neo‐adjuvant treatment of rectal cancer (Kapiteijn 2001; Swedish Rectal Cancer Trial 1997), Total Mesorectal Excision (TME) (Heald 1988) and the expanding role of adjuvant chemotherapy (Dube 1997; Mamounas 1999), the examination of organisational factors such as caseload and specialization should be performed within the context of contemporary studies.

Objectives

The aim of this systematic review and meta‐analyses is to examine the available literature for the effects of hospital and surgeon volume, and surgeon specialization, on the outcomes of colorectal, colon and rectal cancer surgery in the context of modern management routine.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

There is a well‐known absence of randomised‐controlled trials; in the absence of evidence from randomised controlled trials on this issue, all available non‐randomised cohort and observational studies, and subgroup analysis of clinical trials were included.

Types of participants

Patients with a confirmed histological diagnosis of colorectal, colon and rectal cancer in prospective studies and patients with diagnostic codes for colorectal, colon and rectal cancer, derived from International classification of diseases, 9th Revision (ICD‐9‐CM) for retrospective studies. Analysis was primarily performed for all colorectal cancer patients, but effects for colon and rectal cancer patients were examined in separate subgroups where possible; as not all studies provided individual data on colon and rectal cancer, and some studies exclusively reported only on one or the other subgroup, a third subgroup of colorectal cancer patients was established and analysed.

Types of interventions

Intervention: Surgery for colorectal, colon and rectal cancer performed by high volume and/or specialized units/hospitals or surgeons. In studies with more than two stratified groups, the highest volume category was used for comparative analysis.

Control: Surgery for colorectal, colon and rectal cancer performed by low volume and/or non‐specialized units/hospitals or surgeons. Comparisms were restricted to studies that compared an intervention with this control group. In studies where the highest volume category was used as control, the effects were reversed to standardise analysis.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

1. Five‐year overall and/or cancer specific survival 2. Operative mortality rate (inpatient death or death within 30 days from surgery)

Secondary outcomes

1. Five‐year local recurrence rate 2. Postoperative anastomotic leak rate 3. Permanent stoma rate for rectal cancer surgery 4. Abdominoperineal excision of rectum rate (APER) for rectal cancer surgery

Outcomes were stratified according to colon and rectal cancer surgery if possible, otherwise the outcomes were included as colorectal cancer surgery.

Search methods for identification of studies

Papers in all languages were sought and translations carried out where necessary

Electronic searches

Electronic searches from January 1990 to September 2011 were performed in PUBMED, EMBASE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) and LILACS, with no restriction on language and using free text search for words (as well as MESH‐terms) ‐ Appendix 1. We chose 1990 as the study cut off point to capture the effects of volume and outcome in the context of modern colorectal cancer management, as this has changed dramatically over the years.

Searching other resources

Reports of conference proceedings and abstracts from the last 5 years were searched in the following sources:

American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons (ASCRS)

European Society of Coloproctology (ESCP)

Association of Coloproctologists of Great Britain and Ireland (ACPGBI)

The citation lists of included studies were checked and experts in the field contacted to identify further reports of studies.

Data collection and analysis

Selection of studies

All titles and abstracts retrieved by electronic searching were examined independently by two authors (DA, DWB), and duplicates were removed. The remaining titles and abstracts were scrutinised independently for inclusion by the two reviewers (DA, DWB). Disagreements were resolved by discussion. Studies that clearly did not meet the inclusion criteria were excluded and copies of the full text of potentially relevant references were obtained. The eligibility of retrieved studies was assessed independently by the two reviewers (DA, DWB); disagreements were resolved by discussion. Consultation with a third reviewer was not required. Reasons for exclusion of studies were documented.

Data extraction and management

For all included studies, the following data were extracted as recommended in Chapter 7 of the Cochrane Handboook (Higgins 2008).

Author/year of publication

Country

Setting

Study design and methodology

Study population

Total number of participants

Definition of rectum (colorectal/rectal cancer studies only)

Patient characteristics according to intervention groups (as reported):

Sex

Age

Tumour stage

Tumour grade

Comorbidity

Tumour site

Neoadjuvant therapy

Presentation

Ethnicity

Socioeconomic status/income

Total mesorectal rate (rectal cancer studies only)

Details of Intervention

Total number of hospitals/surgeons/specialists

Definitions of hospital and surgeon volumes

Definitions of specialist surgeons

Details of outcome

Data on all reported primary and secondary outcomes were extracted as follows:

For time to event data (e.g. five year overall survival, five year disease specific survival, local recurrence rate), we extracted the log of the unadjusted and case‐mix adjusted hazards ratios and their standard errors from the included studies. Where not reported, we estimated them from other reported statistics using the methods of Parmar 1998.

For dichotomous outcomes (e.g. 30‐day mortality, anastomotic leak rate, permanent stoma rate and APER rates), we extracted the number of patients in each treatment arm who experienced the outcome of interest and the total number of patients assessed, in order to estimate the odds ratio (OR) in unadjusted meta‐analyses.

For dichotomous outcomes we also extracted the adjusted odds ratios and their standard errors where reported for case‐mix adjusted meta‐analyses. Variables adjusted for in case‐mix adjusted analyses were noted.

Data extraction was performed by the two reviewers (DA, DWB) on special data‐extraction‐sheets (see Appendix 2) designed for the review; disagreements were resolved by discussion. There was no need for further appeal to a third reviewer. Data extraction was performed as recommended in chapter 7 of Cochrane Handbook (Higgins 2008) where applicable. The review was performed in RevMan 5.1.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

The risk of bias in included studies was assessed using a modification of the Newcastle‐Ottawa Scale for non‐experimental studies.

Study design

The design of the included studies were coded as:

Low risk: e.g. if population‐based, multi‐centred and prospectively designed

High risk: e.g. if not population‐based, not multi‐centred and retrospectively designed

Unclear risk:e.g. if no clear study design was reported

Representativeness of study cohort

The representativeness of participants in studies of colorectal/colon/rectal cancer patients were coded as:

Low risk: e.g. if study cohort was representative and not from selected groups

High risk: e.g. if somewhat representative or from selected groups

Unclear risk: e.g. if no description of cohort was reported

Ascertainment of intervention

The ascertainment of surgeon/hospital volume and surgeon specialization in included studies were coded as:

Low risk: e.g. if ascertainment of intervention was from study data or from structured interviews

High risk: e.g. if self reported

Unclear risk: e.g. if not reported

Comparability of intervention and comparison/control group

The comparability of participants in the intervention and comparison/control groups were coded as:

Low risk: e.g. if study reported no differences between intervention and comparison/control group and/or if adjustments for case‐mix differences between intervention and comparison/control were performed

High risk e.g. if study reported significant differences between intervention and comparison/control group and/or if adjustments for case‐mix differences between intervention and comparison/control were not performed

Unclear risk e.g. if differences between intervention and comparison/control groups were not reported

Assessment of outcomes

The assessments of primary and secondary outcomes in studies were coded as:

Low risk: e.g. if independent blind assessment of outcomes was performed or outcomes were assessed by the use of record linkage

High risk: e.g. if self reporting of outcomes was performed

Unclear risk: e.g. if no description was reported of how the outcomes were assessed.

Addressing incomplete data

The proportion of participants whose outcomes were analysed in included studies were assessed and coded as:

Low risk: e.g. if loss of outcome data for participants or participants lost to follow‐up was unlikely to introduce bias (<20%)

high risk: e.g. if loss of outcome data for participants or participants lost to follow‐up was likely to introduce bias (>20%)

Unclear risk: e.g. if no information was provided

Missing data on primary interventions and outcomes

The proportion of participants in the intervention groups whose outcomes were analysed in included studies were assessed and coded as:

Low risk: e.g. if loss of data on primary interventions and outcomes was unlikely to introduce bias (<20%)

High risk: e.g. if loss of data on primary interventions and outcomes was likely to introduce bias (>20%)

Unclear risk: e.g. if no information was provided

Assessment of risk of bias was independently performed (DA and DWB) and disagreements resolved by discussion.

Measures of treatment effect

The following measures of the effect of treatment were used:

For time to event data, we used the hazard ratio

For dichotomous data, we used the odds ratio

Unit of analysis issues

Studies that adjusted for the effects of clustering within healthcare providers were noted, and a unit of analysis error if this was not performed was recorded.

Dealing with missing data

Missing outcome data was not imputed. Where data was missing, an attempt was made to contact study authors to request data on the outcomes only among participants that were assessed.

Assessment of heterogeneity

Heterogeneity between studies was assessed by visual inspection of forest plots, by estimation of the percentage heterogeneity between studies, which cannot be attributed to sampling variation (Higgins 2003), and by a formal statistical test of heterogeneity (Deeks 2001).

Assessment of reporting biases

Funnel plots corresponding to meta‐analysis of the case‐mix adjusted primary outcome (inpatient and 30 day mortality) was examined to assess the potential for publication bias.

Data synthesis

Results were pooled together in unadjusted and case‐mix adjusted meta‐analyses using random effects models.

For adjusted and unadjusted time to event data, hazard ratios were pooled using the generic inverse variance facility of Revman 5.1

For dichotomous data, adjusted odds ratios were also pooled using the generic inverse variance facility of Revman 5.1

For unadjusted dichotomous data, the absolute numbers for each outcome, and the total numbers in intervention and comparison groups were entered into Revman 5.1 for unadjusted meta‐analyses using the Mantel Haenszel statistical method.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

Subgroup analyses was performed, grouping the studies according to continent of origin (North‐America versus Europe). Further subgroup analysis would have been performed for rectal cancer patients only according to site of tumour, (e.g. true rectal and rectosigmoid cancers) if more than one rectal cancer study reporting on adjusted estimates for the outcome APER rate were identified (see Differences between protocol and review)

Sensitivity analysis

Sensitivity analyses was not performed as all studies were non‐randomised and observational by nature (see Differences between protocol and review ).

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

The search strategy identified a total of 894 potentially relevant studies, of which 797 were excluded on the basis of title or abstract. For the remaining 97 studies, the full text were obtained and reviewed. Forty‐three studies were excluded on the basis of reasons listed in the section on Characteristics of excluded studies. In total, 54 studies were judged to fulfil the inclusion criteria; however, three potentially valuable studies (Gort 2010; Grabham 1996; Larson 2008) could not be included in quantitative analyses due to insufficient published statistics or data, leaving 51 studies that were included in the meta‐analysis. Any disagreements were resolved by discussion between the two reviewers (DA, DWB).

Included studies

Characteristics of included studies

Twenty‐eight studies were based in Europe; 11 studies were UK‐based (Borowski 2007; Borowski 2010; Carter et al 1995; Dorrance 2000; Grabham 1996; McArdle 2004; Mella 1997; Ng 2006, Parry 1999; Platell 2003; Smith 2003), five based in Germany (Engel 2005B; Marusch 2001A; Marusch 2001B; Mroczkowski 2011; Ptok 2007), four in the Netherlands (Elferink 2010A; Elferink 2010B; Engel 2005A; Gort 2010), three in Sweden (Kressner 2009; Martling 2002; Sjovall 2007), two in Norway (Debes 2008; Wibe 2005) and one study each in Denmark (Harling 2005) and Spain (Manchon‐Walsh 2011). One study covered a number of European centres (COLOR Study Group). Twenty‐one studies were based in North America; 18 studies were based in USA (Billingsley 2007; Birkmeyer 2002; Dimick 2003; Drolet 2011; Finlayson 2003; Hannan 2002; Harmon 1999; Hodgson 2003; Larson 2008; Meyerhardt 2003; Meyerhardt 2004; Purves 2005; Rabeneck 2004; Rogers 2006; Schrag 2002; Schrag 2003; Simons 1997; Zhang 2007) and three studies in Canada (Simunovic 2000; Simunovic 2006; Urbach 2004). Two studies originated from Asia (Kuwabara 2009; Lin 2006) and three from Australia (Marwan 2010; McGrath 2005; Morris 2007). Twenty‐eight studies were of retrospective design (Billingsley 2007; Birkmeyer 2002; Debes 2008; Dimick 2003; Dorrance 2000; Drolet 2011; Elferink 2010A; Elferink 2010B; Finlayson 2003; Harling 2005; Harmon 1999; Hodgson 2003; Kuwabara 2009; Lin 2006; Manchon‐Walsh 2011; Marwan 2010; Morris 2007; Ng 2006; Parry 1999; Rabeneck 2004; Rogers 2006; Schrag 2002; Schrag 2003; Simons 1997; Simunovic 2000; Simunovic 2006; Urbach 2004; Zhang 2007), and 25 studies were prospective (Borowski 2007; Borowski 2010; Carter et al 1995; COLOR Study Group; Engel 2005A; Engel 2005B; Gort 2010; Grabham 1996; Hannan 2002; Kressner 2009; Larson 2008; Martling 2002; Marusch 2001A; Marusch 2001B; McGrath 2005; Mella 1997; Meyerhardt 2003; Meyerhardt 2004; Mroczkowski 2011; Platell 2003; Ptok 2007; Purves 2005; Sjovall 2007; Smith 2003; Wibe 2005). One study was by design in part retrospective and prospective (McArdle 2004). Most studies were based on data from population registries, with the exception of 13 studies (Birkmeyer 2002; COLOR Study Group; Debes 2008; Dorrance 2000; Harmon 1999; Larson 2008; Marusch 2001A; Marusch 2001B; Ng 2006; Platell 2003; Ptok 2007; Purves 2005; Rabeneck 2004).

In 15 studies, the effect of the intervention(s) were reported on a combined cohort of colorectal cancer patients (Borowski 2007; Borowski 2010; Carter et al 1995; Dimick 2003; Dorrance 2000; Engel 2005A; Harmon 1999; McArdle 2004; Mella 1997; Parry 1999; Platell 2003; Rabeneck 2004; Rogers 2006; Urbach 2004; Zhang 2007), although data in one study (Borowski 2010) was available for analysis of colon and rectal cancers separately. Seventeen studies assessed the effect of the intervention(s) on colon cancer patients (Billingsley 2007; Birkmeyer 2002; COLOR Study Group; Drolet 2011; Elferink 2010A; Finlayson 2003; Hannan 2002; Kuwabara 2009; Larson 2008; Lin 2006; Marusch 2001B; Meyerhardt 2003; Morris 2007; Mroczkowski 2011; Schrag 2003; Simunovic 2006; Sjovall 2007), and 22 studies assessed the effect of the intervention(s) on rectal cancer patients only (Debes 2008; Elferink 2010B; Engel 2005B; Gort 2010; Grabham 1996; Harling 2005; Hodgson 2003; Kressner 2009; Manchon‐Walsh 2011; Martling 2002; Marusch 2001A; Marwan 2010; McGrath 2005; Meyerhardt 2004; Ng 2006; Ptok 2007; Purves 2005; Schrag 2002; Simons 1997; Simunovic 2000; Smith 2003; Wibe 2005).

The effects of hospital volume alone was assessed by 29 studies (Birkmeyer 2002; COLOR Study Group; Dimick 2003; Elferink 2010A; Elferink 2010B; Engel 2005A; Engel 2005B; Finlayson 2003; Hannan 2002; Harling 2005; Hodgson 2003; Kressner 2009; Kuwabara 2009; Lin 2006; Manchon‐Walsh 2011; Marusch 2001A; Marusch 2001B; Meyerhardt 2003; Meyerhardt 2004; Mroczkowski 2011; Ptok 2007; Rabeneck 2004; Simons 1997; Simunovic 2000; Simunovic 2006; Sjovall 2007; Urbach 2004; Wibe 2005; Zhang 2007), and effects of surgeon volume alone was assessed by seven studies (Carter et al 1995; Debes 2008; Grabham 1996; Larson 2008; McArdle 2004; Morris 2007; Purves 2005). Ten studies assessed the effects of both hospital and surgeon volume (Billingsley 2007; Borowski 2010; Drolet 2011; Gort 2010; Harmon 1999; McGrath 2005; Parry 1999; Rogers 2006; Schrag 2002; Schrag 2003). Three studies reported the effects of specialization alone (Dorrance 2000; Ng 2006, Platell 2003), and six studies reported both effects of specialization and surgeon volume (Borowski 2007Martling 2002; Marwan 2010; McArdle 2004; Mella 1997; Smith 2003).

Twenty‐eight studies adjusted for important prognostic factors, of which twelve studies reported overall five year survival (Borowski 2007; Borowski 2010; Kressner 2009; McArdle 2004; Meyerhardt 2003; Meyerhardt 2004; Morris 2007; Platell 2003; Simunovic 2000; Rabeneck 2004; Rogers 2006; Smith 2003; Wibe 2005), one reported five‐year disease specific survival (McArdle 2004 ), 18 reported inpatient and 30‐day mortality (Billingsley 2007; Birkmeyer 2002; Borowski 2007; Borowski 2010; Drolet 2011; Elferink 2010A; Elferink 2010B; Engel 2005B; Finlayson 2003; Harling 2005; Hodgson 2003; Lin 2006; Manchon‐Walsh 2011; Rogers 2006; Simunovic 2000; Simunovic 2006; Smith 2003; Urbach 2004), three studies reported five‐year local recurrence rate (Meyerhardt 2004; Ptok 2007; Wibe 2005), five studies reported permanent stoma rate (Borowski 2007; Borowski 2010; Harling 2005; Hodgson 2003; Rogers 2006), two reported APER rates (Meyerhardt 2004; Purves 2005). Studies adjusting for the various prognostic factors and corresponding primary and secondary outcomes are displayed in theTable 6.

1. Casemix adjusted studies, study outcomes and adjusted prognostic factors.

| Study ID | Outcomes | Type of tumour | Age | Sex | Stage | Grade | Site | Comorbidity | Socioeconomic Status/Income | Ethnicity | Unit of analysis error | Surgeon characteristics | Hospital characteristics | Presentation | Lymph nodes | Others |

| Borowski 2007 | OS*, M*, AL*, PS* | Colorectal | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N |

| Borowski 2010 | OS*, M*, AL*, PS* | Colorectal | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N |

| Rabeneck 2004 | OS* | Colorectal | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Marital status |

| Rogers 2006 | M*, OS*, PS* | Colorectal | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Engel 2005A | M* | Colorectal | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N |

| Urbach 2004 | M* | Colorectal | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N |

| Platell 2003 | OS* | Colorectal | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Chemotherapy |

| Smith 2003 | DS*, OS* M*, AL*, APER | Colorectal | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N |

| McArdle 2004 | OS*, DS*, M |

Colorectal | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N |

| Meyerhardt 2003 | OS* | Colon | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N |

| Billingsley 2007 | M* | Colon | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N |

| Birkmeyer 2002 | M* | Colon | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N |

| Drolet 2011 | M* | Colon | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Procedure type, Insurance status, Laproscopy |

| Elferink 2010A | M* | Colon | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Cancer region. |

| Finlayson 2003 | M* | Colon | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Year of procedure |

| Lin 2006 | M* | Colon | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N |

| Simunovic 2006 | M* | Colon | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Place of residence |

| Morris 2007 | OS*, M | Colon | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Simunovic 2000 | OS*, M* | Rectal | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Referral to regional centre. |

|

Purves 2005 |

APER* | Rectal | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N |

| Wibe 2005 | OS*, M, LR*, AL, APER | Rectal | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N |

| Meyerhardt 2004 | OS*, LR*, APER* | Rectal | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Elferink 2010B | M* | Rectal | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Cancer region |

| Harling 2005 | OS, M*, AL*, PS* | Rectal | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N |

| Hodgson 2003 | M*, PS* | Rectal | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N |

| Kressner 2009 | OS*, M, AL*, LR | Rectal | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Radiotherapy |

| Manchon‐Walsh 2011 | M*, AL, PS | Rectal | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | Procedure type, Year of surgery |

| Ptok 2007 | LR*, APER | Rectal | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | Tumour perforation, Type of procedure, CRM |

Abbreviations

*= Outcomes for which prognostic factors were considered in case mix adjusted studies. Abbreviations; OS= Overall five year survival, M= 30 day and in‐patient mortality, LR=Five year local recurrence rate, AL= Anastomotic leak rate, PS= Permanent stoma rate, APER= Abdominoperineal excision of the rectum rate, Y=YES, N=No

Characteristics of participants

Across all studies, a total of 943,728 patients were included in the meta‐analysis; 222,993 patients with colorectal cancer and no further subgroup analysis for colon and rectum, 655,009 patients with colon cancer, and 65,726 patients with rectal cancer. Patients' age and gender were reported in all but six studies (Grabham 1996; Harling 2005; Marusch 2001A; Mella 1997; Mroczkowski 2011; Simons 1997). One study reported on age, but not on gender (Ng 2006). Tumour staging was reported through the International Union against Cancer (UICC) classification in 14 studies (Billingsley 2007; Elferink 2010A; Elferink 2010B; Engel 2005B; Gort 2010; Kressner 2009; Manchon‐Walsh 2011; Martling 2002; Marusch 2001B; Marwan 2010; Mroczkowski 2011; Ptok 2007; Rabeneck 2004; Sjovall 2007), the American Joint Commitee on Cancer (AJCC) staging classification in seven studies (COLOR Study Group; Hodgson 2003; Larson 2008; Rogers 2006; Schrag 2002; Schrag 2003; Zhang 2007), UICC TNM staging classification in four studies (Drolet 2011; Meyerhardt 2003; Meyerhardt 2004; Simunovic 2006) and Dukes' stage in 13 studies (Borowski 2007; Borowski 2010; Carter et al 1995; Debes 2008; Dorrance 2000; Harling 2005; McArdle 2004; McGrath 2005; Mella 1997; Ng 2006; Parry 1999; Smith 2003; Wibe 2005). One study reported tumour stage specifically by presence of localised disease only, lymph node involvement and organ metastases (Harmon 1999). The grade of the tumour was reported in six studies (Debes 2008; Engel 2005B; Meyerhardt 2003; Meyerhardt 2004; Parry 1999; Wibe 2005). Comorbidity was stratified by the Charlson score and it's modifications in 18 studies (Billingsley 2007; Birkmeyer 2002; Dimick 2003; Finlayson 2003; Gort 2010; Harmon 1999; Hodgson 2003; Kuwabara 2009; Lin 2006; Purves 2005; Rabeneck 2004; Rogers 2006; Schrag 2002; Schrag 2003; Simunovic 2000; Smith 2003; Urbach 2004; Zhang 2007), the American Society of Anaesthesiology (ASA) grading system in 10 studies (Borowski 2007; Borowski 2010; Carter et al 1995; Larson 2008; Manchon‐Walsh 2011; Marusch 2001B; Mella 1997; Mroczkowski 2011; Platell 2003; Ptok 2007), performance status in two studies (Meyerhardt 2003; Meyerhardt 2004) and Elixauser system in one study (Drolet 2011). The incidence of neoadjuvant radiotherapy was reported in four of the rectal cancer studies (Engel 2005B; Harling 2005; Martling 2002, Wibe 2005). Urgency of surgery or the mode of presentation was reported in 20 studies (Billingsley 2007; Birkmeyer 2002; Borowski 2007; Borowski 2010; Carter et al 1995; Dimick 2003; Dorrance 2000; Engel 2005A; Finlayson 2003; Grabham 1996; Harmon 1999; Marusch 2001B; McArdle 2004; Mella 1997; Parry 1999; Platell 2003; Schrag 2002; Schrag 2003; Sjovall 2007; Smith 2003).

Patient's ethnicity was reported by 14 studies (Billingsley 2007; Birkmeyer 2002; Finlayson 2003; Hannan 2002; Harmon 1999; Hodgson 2003; Meyerhardt 2003; Meyerhardt 2004; Purves 2005; Rabeneck 2004; Rogers 2006; Schrag 2002; Schrag 2003; Zhang 2007), and socioeconomic status or income data was reported in eight studies (Billingsley 2007; Finlayson 2003; Hodgson 2003; Purves 2005; Rogers 2006; Schrag 2002; Schrag 2003; Zhang 2007).

In studies that reported outcomes for rectal cancer, a definition of the rectum in terms of distance from the anal verge was given as 15 cm, 16cm and 18cm in eight studies, (Borowski 2007; Borowski 2010; Debes 2008; Kressner 2009; Mella 1997; Ng 2006; Smith 2003; Wibe 2005), four studies (Engel 2005B; Manchon‐Walsh 2011; Marusch 2001A; Ptok 2007) and one study (Platell 2003), respectively. ICD‐9 codes and ICD for oncology 3rd edition C20 were used in six studies (Dimick 2003, Harmon 1999; Meyerhardt 2004; Parry 1999; Purves 2005; Rabeneck 2004) and one study (Marwan 2010), respectively.

Characteristics of interventions

Three studies reported the rate of total mesorectal excision in their studies (Debes 2008; Martling 2002; Marusch 2001A). All studies assessed the impact of the intervention(s) on patients based on open abdominal surgery, but may have included some patients who underwent laparoscopic surgery; however, two studies specifically examined laparoscopic surgery for colon cancer (COLOR Study Group; Kuwabara 2009).

Two volume/caseload groups were used in five studies reporting on hospital volume (McGrath 2005; Rabeneck 2004; Simons 1997; Sjovall 2007; Urbach 2004) and five studies reporting on surgeon volume (Carter et al 1995; Debes 2008; Martling 2002; Marwan 2010; McGrath 2005). Three volume/caseload groups were used in 20 studies reporting on hospital volume (Borowski 2010; COLOR Study Group; Drolet 2011; Elferink 2010A; Elferink 2010B; Engel 2005A; Engel 2005B; Finlayson 2003; Gort 2010; Harling 2005; Harmon 1999; Kressner 2009; Manchon‐Walsh 2011; Marusch 2001A; Marusch 2001B; Meyerhardt 2003; Meyerhardt 2004; Mroczkowski 2011; Ptok 2007; Simunovic 2000) and nine studies reporting on surgeon volume (Borowski 2010; Drolet 2011; Gort 2010; Harmon 1999; Larson 2008; McArdle 2004; Mella 1997; Morris 2007; Purves 2005). Four volume/caseload groups were used in 12 studies reporting on hospital volume (Billingsley 2007; Dimick 2003; Hannan 2002; Hodgson 2003; Kuwabara 2009; Parry 1999; Rogers 2006; Schrag 2002; Schrag 2003; Simunovic 2006; Wibe 2005; Zhang 2007) and five surgeon volume studies (Billingsley 2007; Parry 1999; Rogers 2006; Schrag 2002; Schrag 2003). One study reported on surgeon volume, using six volume/caseload groups (Smith 2003). Although two studies reported on the same patient population, both were included in the analysis; volume/caseload groups were taken from only one of these (Borowski 2010), whilst analysis on the effects of specialists was taken from the other (Borowski 2007).

Excluded studies

Twenty‐three studies were excluded as their study period was outside the set inclusion criteria (Beart 1995; Bokey 1997; Crocetti 1996; Dahlberg 1998; Hayanga 2010; Hermanek 1995; Hermanek 1996; Hermanek 1998; Hermanek 1999; Hermanek 2000; Hilska 2004; Holm 1997; Luna‐Perez 1999; Mander 2002; Martling 2000McArdle 1991; Mohner 1990; Paquette 2010; Pata 2008; Porter 1998; Read 2002; Renzulli 2006; Stocchi 2001; Ubhi 1995 ). Volume/caseload analysis were not performed in six studies (Easson 2002; McArdle 2002; Jestin 2004; Shankar 2001; Singh 1995; Smedh 2001). Three studies did not report any of the measured outcome variables (Miller 2004; Yasunaga 2009a; Yasunaga 2009b). Local recurrence follow‐up for fewer than five years was reported by four studies (Dorrance 1997; Kapiteijn 1998; Machado 2000; Syk 2010). Overall survival was reported by two studies for two years only in two studies (Kee 1999; Machado 2000). The study cohort in two studies were not exclusively cancer patients (Callahan 2003; Hayanga 2010), one study (Schrag 2000) had data previously used in an included study (Schrag 2003), and we did not identify a reference group in the analyses in one study (Ho 2006).

Risk of bias in included studies

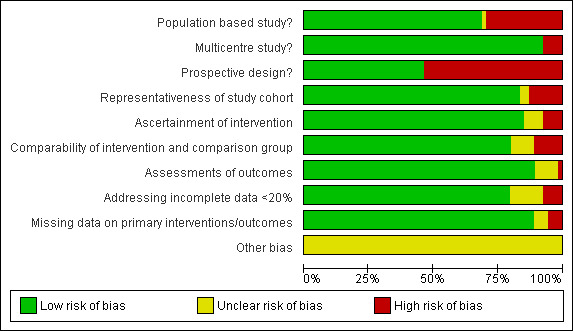

1.

Risk of bias graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

2.

Risk of bias summary: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item for each included study.

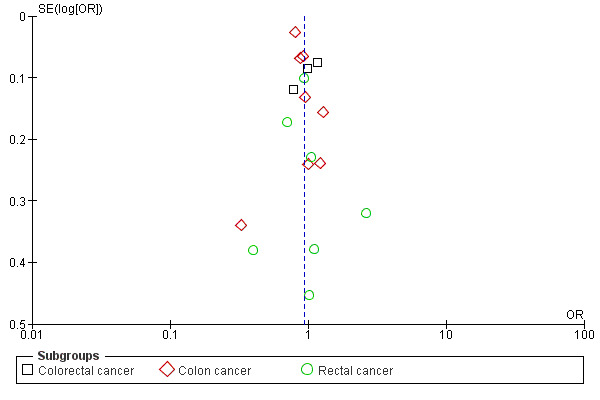

Overall, participants in included studies were satisfactorily representative of colorectal/colon/rectal cancer patients (85%). We judged study design to be satisfactory across studies as approximately fifty percent (50%) of included studies were prospective and approximately ninety percent (90%) were population based and multi‐centred. We judged the ascertainment of interventions and outcomes to be objective across all included studies (88% and 90% respectively). Comparability of intervention and comparison/control group in included studies was satisfactory in our judgement (80%). Missing data on interventions and outcomes in included studies were dealt with satisfactorily (80% and 90% respectively). There was no significant publication bias (see Figure 3).

3.

Funnel plot based on hospital volume and the adjusted operative mortality

4 Hospital volume (adjusted analysis), outcome: 4.2 Inpatient and 30 day mortality.

Effects of interventions

See: Table 1; Table 2; Table 3; Table 4; Table 5

Hospital volume

Overall 5‐year survival for unadjusted studies

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospital volume (unadjusted analysis), Outcome 1 Overall five year survival.

The meta‐analyses of two studies (Rabeneck 2004; Rogers 2006), including 36,858 colorectal cancer patients, showed a significant effect on the five‐year risk of death in favour of high volume hospitals (HR=0.88, 95 %CI 0.80 to 0.98), but had significant heterogeneity between the two studies (i2=94%). In contrast, there was no significant benefit associated with high‐volume hospitals for colon cancer surgery (HR=0.94, 95% CI 0.84 to 1.05) for 22,464 patients from three studies (Borowski 2010; Meyerhardt 2003; Mroczkowski 2011), and for rectal cancer surgery (HR=0.92, 95%CI 0.79 to 1.07) for 13,021 patients in seven studies (Borowski 2010; Harling 2005; Kressner 2009; Meyerhardt 2004; Schrag 2002; Simons 1997; Wibe 2005). There was significant heterogeneity between the colon cancer and rectal cancer studies (I2=97%, and I2=97%, respectively). When all patients from included colorectal, colon and rectal cancer studies with unadjusted data were combined, there was no significant hospital‐volume effect on 5‐year survival (HR=0.92, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.04). Interestingly, the meta‐analysis of the unadjusted data from studies originating from other countries than the United States (Borowski 2010; Harling 2005; Kressner 2009; Mroczkowski 2011; Wibe 2005) was not significant (HR=0.97, 95% CI 0.90 ‐ 1.04), whereas US data (Meyerhardt 2003; Meyerhardt 2004; Rabeneck 2004; Rogers 2006; Schrag 2002; Simons 1997) suggested a significant benefit for high‐volume hospitals (HR=0.87, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.96).

Overall 5‐survival year for studies with case‐mix adjustment

4.1. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospital volume (adjusted analysis), Outcome 1 Overall five year survival.

Two studies (Rabeneck 2004; Rogers 2006), including 36,858 colorectal cancer patients, and four studies (Borowski 2010; Meyerhardt 2004; Simunovic 2000; Wibe 2005), including 5,100 rectal cancer patients, used case‐mix adjustment. Both meta‐analyses demonstrated a significant benefit in 5‐year overall survival associated with high‐volume hospital care (HR=0.90, 95% CI 0.84 to 0.95, and HR=0.85, 95% CI 0.77 to 0.93, respectively); there was significant heterogeneity between colorectal cancer studies (I2=60%), but not between rectal cancer studies (I2=0%). In contrast, no significant volume‐outcome relationship was demonstrated in the meta‐analysis of two case‐mix adjusted studies (Borowski 2010; Meyerhardt 2003), assessing 5,211 patients with colon cancer (HR=0.97, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.22); there was significant heterogeneity between the two studies (I2=88%). Across all 55,169 patients included in the meta‐analysis, however, there remained a significant effect in favour of high volume hospitals (HR=0.90, 95% CI 0.85 to 0.96). Similar to the analysis of studies with unadjusted survival data, two non‐US based studies (Borowski 2010; Wibe 2005) demonstrated no significant effect (HR=0.93, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.13), whilst US data (Meyerhardt 2003; Meyerhardt 2004; Rabeneck 2004; Rogers 2006; Simunovic 2000) suggested better survival in high‐volume hospitals (HR=0.90, 95% CI 0.87 to 0.93).

Operative mortality for unadjusted studies

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospital volume (unadjusted analysis), Outcome 2 Inpatient and 30 day mortality.

Meta‐analyses of seven studies on colorectal cancer (Dimick 2003; Engel 2005A; Hannan 2002; Parry 1999; Rogers 2006; Urbach 2004; Zhang 2007), assessing 113,795 patients, and seven rectal cancer studies (Borowski 2010; Harling 2005; Hodgson 2003; Kressner 2009; Schrag 2002; Simunovic 2000; Wibe 2005), including 18,383 patients, did not show significant differences in mortality rates between high and low volume hospitals (OR=0.74, 95% CI 0.55 to 1.00, and OR=0.75, 95% CI 0.54 to 1.05, respectively). The analyses showed significant heterogeneity amongst the colorectal (I2=95%) and rectal cancer studies (I2=75%). Conversely, the meta‐analyses of 14 studies (Billingsley 2007; Birkmeyer 2002; Borowski 2010; COLOR Study Group; Drolet 2011; Finlayson 2003; Hannan 2002; Kuwabara 2009; Lin 2006; Marusch 2001B; Mroczkowski 2011; Schrag 2003; Simunovic 2006; Sjovall 2007), including 309,693 colon cancer patients, showed a significant difference in mortality rates in favour of high volume hospitals (OR=0.75, 95% CI 0.67 to 0.83), with significant heterogeneity between individual studies (I2=78%). Nonetheless, the overall effect of higher hospital volume for all colorectal, colon and rectal cancer patients was significant (OR=0.75, 95% CI 0.68 to 0.84). Of interest, most studies reporting unadjusted mortality data originated from the United States; the meta‐analysis of studies reporting from countries other that the US (Borowski 2010; COLOR Study Group; Engel 2005A; Harling 2005; Kressner 2009; Kuwabara 2009; Lin 2006; Marusch 2001A; Mroczkowski 2011; Parry 1999; Simunovic 2000; Simunovic 2006; Sjovall 2007; Urbach 2004; Wibe 2005) revealed no association between caseload and mortality (OR=0.93, 95% CI 0.81 to 1.06), whereas US‐based studies (Billingsley 2007; Birkmeyer 2002; Dimick 2003; Drolet 2011; Finlayson 2003; Hannan 2002; Harmon 1999; Hodgson 2003; Rogers 2006; Schrag 2002; Schrag 2003; Zhang 2007) overall suggested a significant effect (OR=0.63, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.70).

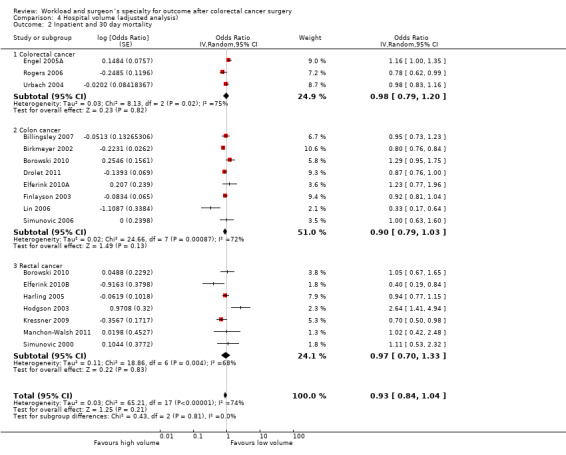

Operative mortality for studies with case‐mix adjustment

4.2. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospital volume (adjusted analysis), Outcome 2 Inpatient and 30 day mortality.

Including only studies that used case‐mix adjustment, there was no significant volume‐outcome relationship for operative mortality amongst three colorectal cancer studies (Engel 2005A; Rogers 2006; Urbach 2004), including a total of 77,823 patients (OR=0.98, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.20), eight colon cancer studies (Billingsley 2007; Birkmeyer 2002; Borowski 2010; Drolet 2011; Elferink 2010A; Finlayson 2003; Lin 2006; Simunovic 2006), including 302,978 patients (OR=0.90, 95% CI 0.79, 1.03), and seven rectal cancer studies (Borowski 2010; Elferink 2010B; Harling 2005; Hodgson 2003; Kressner 2009; Manchon‐Walsh 2011; Simunovic 2000), including 33,747 patients (OR=1.07, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.50). However there was significant heterogeneity between the studies for colorectal, colon and rectal cancer (I2=83%, I2=72%, I2=68%, respectively). The overall effect of hospital volume on in‐patient and 30 day mortality for all colorectal, colon and rectal cancer patients was not significant (OR=0.95, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.05). Stratified by country, adjusted data on hospital caseload from non‐US studies (Borowski 2010; Engel 2005A; Harling 2005; Kressner 2009; Lin 2006; Simunovic 2000; Simunovic 2006; Urbach 2004) equally did not suggest a significant association (OR=0.95, 95% CI 0.80 to 1.14), whereas US data (Billingsley 2007; Birkmeyer 2002; Drolet 2011; Finlayson 2003; Kressner 2009; Rogers 2006; Simunovic 2000; Simunovic 2006) suggested a greater, but still not a significant hospital effect (OR=0.89, 95% CI 0.79 to 1.01).

Five‐year local recurrence for unadjusted studies

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospital volume (unadjusted analysis), Outcome 3 Five year local recurrence rate.

Meta‐analyses of four rectal cancer studies (Engel 2005B; Meyerhardt 2004; Ptok 2007; Wibe 2005), totaling 3,870 patients, demonstrated significantly lower risk of local recurrence within five years in favour of high volume hospitals (HR=0.70, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.91). There was moderate heterogeneity between the studies (I2=55%).

Five‐year local recurrence for studies with case‐mix adjustment

4.3. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospital volume (adjusted analysis), Outcome 3 Five year local recurrence rate.

Although meta‐analysis on 2,986 patients in three rectal cancer studies (Meyerhardt 2004; Ptok 2007; Wibe 2005) demonstrated an effect in favour of high volume hospitals, this was not statistically significant (HR=0.77, 95% CI 0.51 to 1.16) and there was significant heterogeneity between the studies (I2=72%).

Anastomotic leak rate for unadjusted studies

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospital volume (unadjusted analysis), Outcome 4 Anastomotic leak rate.

Meta‐analyses of three colon cancer studies (Borowski 2010; COLOR Study Group; Marusch 2001B), assessing 4,568 patients, and five rectal cancer studies (Borowski 2010; Harling 2005; Manchon‐Walsh 2011; Marusch 2001A; Wibe 2005), assessing 4,962 patients, did not show significant effect attributable to high‐volume hospitals (OR=1.26, 95% CI 0.66 to 2.41, and OR=1.1, 95% CI 0.77‐1.61, respectively). There was moderate heterogeneity between the studies (I2=56%, and I2= 58%, respectively). The overall effect of hospital volume on colon and rectal cancer patients was not significant (OR=1.1, 95% CI 0.77 to 1.61).

Anastomotic leak rate for studies with case‐mix adjustment

4.4. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospital volume (adjusted analysis), Outcome 4 Anastomotic leak rate.

Using odds ratios to compare the risk of anastomotic leaks between high and low volume hospitals, one study (Borowski 2010) assessed 2,808 colon cancer patients and showed a greater risk for anastomotic leak in high volume hospitals (OR=1.44, 95% CI 0.80 to 2.59), but this was not statistically significant. In contrast, meta‐analysis of three studies (Borowski 2010; Harling 2005; Kressner 2009), assessing 13,040 rectal cancer patients, demonstrated significantly lower odds for anastomotic leaks in favour of high volume hospitals (OR=0.77, 95% CI 0.61 to 0.97). There was no heterogeneity between the rectal cancer studies (I2=0%). The overall effect of hospital volume on anastomotic leak rates for colon and rectal cancer surgery was in favour of high‐volume hospitals, but this was not significant (OR=0.87, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.18).

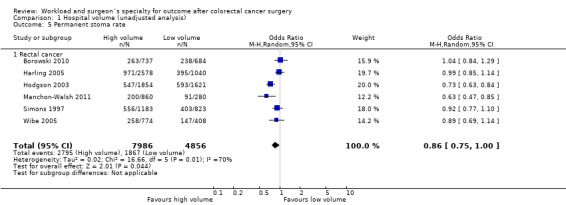

Permanent stoma rate for unadjusted studies

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospital volume (unadjusted analysis), Outcome 5 Permanent stoma rate.

Six rectal cancer studies (Borowski 2010; Harling 2005; Hodgson 2003; Manchon‐Walsh 2011; Simons 1997; Wibe 2005), including 12,852 patients, did not show a significant difference between high and low volume hospitals (OR=0.86, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.00); there was significant heterogeneity between the studies (I2=70%)

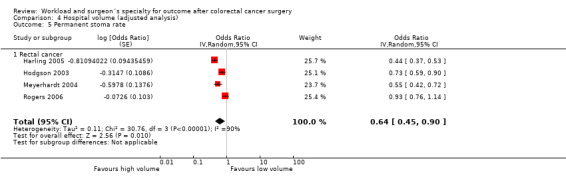

Permanent stoma rate for studies with case‐mix adjustment

4.5. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospital volume (adjusted analysis), Outcome 5 Permanent stoma rate.

In contrast to the findings in unadjusted analysis, the meta‐analysis of four studies (Harling 2005; Hodgson 2003; Meyerhardt 2004; Rogers 2006), assessing 15,475 rectal cancer patients, showed statistically significant lower risk of permanent stoma formation in favour of higher volume hospitals (OR=0.64, 95% CI 0.45 to 0.90). There was significant heterogeneity between the studies (I2=90%).

APER rate for unadjusted studies

1.6. Analysis.

Comparison 1 Hospital volume (unadjusted analysis), Outcome 6 Abdominoperineal excision of rectum rate.

Meta‐analysis of nine studies (Engel 2005B; Harmon 1999; Marusch 2001A; McGrath 2005; Meyerhardt 2004; Parry 1999; Ptok 2007; Schrag 2002; Wibe 2005), totaling 7,609 rectal cancer patients, showed significant differences between high and low volume hospitals (OR=0.80, 95% CI 0.65 to 0.99). There was significant heterogeneity between the studies (I2=76%)

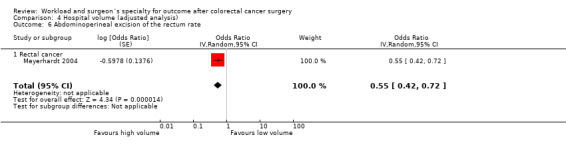

APER rate for studies with case‐mix adjustment

4.6. Analysis.

Comparison 4 Hospital volume (adjusted analysis), Outcome 6 Abdominoperineal excision of the rectum rate.

One study of 1330 rectal cancer patients (Meyerhardt 2004) showed a statistically significant lower odds of APER (OR=0.55, 95% CI 0.42 to 0.72) in favour of high volume hospitals.

Surgeon volume

Overall 5‐year survival for unadjusted studies

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Surgeon volume (unadjusted analysis), Outcome 1 Overall five year survival.

Meta‐analysis of two colorectal cancer studies (McArdle 2004; Rogers 2006), assessing 17,232 patients, and three rectal cancer studies on 3,279 patients (Borowski 2010; Debes 2008; Schrag 2002) showed a lower risks of death within five years in favour of high volume surgeons (HR=0.86, 95% CI 0.82 to 0.90, and HR=0.85, 95% CI 0.78 to 0.94, respectively). There was no significant heterogeneity between the colon cancer and rectal cancer studies (I2=17% and I2=34%, respectively). Meta‐analysis of two studies (Borowski 2010; Morris 2007), assessing 3,670 colon cancer patients, did show similarly low risk of death in favour of high‐volume surgeons (HR=0.85, 95% CI 0.71 to 1.02), but failed to reach statistical significance. There was significant heterogeneity between the studies (I2=83%). The overall effect of surgeon volume on colorectal, colon and rectal cancer surgery for overall five year survival was significant, and in favour of higher caseload (HR=0.85, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.90). Contrasting with findings relating to hospital volume, there were no differences between US (Rogers 2006; Schrag 2002) and non‐US data (Borowski 2010; Debes 2008; McArdle 2004; Morris 2007) in stratified analysis of surgeon caseload (HR=0.84, 95% CI 0.81 to 0.88, and HR=0.87, 95% CI 0.80 to 0.95, respectively).

Overall 5‐year survival for studies with case‐mix adjustment

5.1. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Surgeon volume (adjusted analysis), Outcome 1 Overall five year survival.

Meta‐analyses of two colorectal cancer studies (McArdle 2004; Rogers 2006), assessing 17,232 patients, showed a lower risk of death within five years in favour of high volume surgeons (HR=0.87, 95%CI 0.82 to 0.92). There was no heterogeneity between the two studies (I2=0%). Using a hazard ratio to compare the survival between high volume and low volume surgeons, one study (Borowski 2010), study assessing 2,907 patients, showed a lower risk of death within five years (HR=0.84, 95% CI 0.76 to 0.93) for colon cancer surgery in favour of high volume surgeons. However for 1,903 rectal cancer patients in the same study (Borowski 2010), the relationship was not significant (HR=0.99, 95%CI 0.86 to 1.14). The overall effect of surgeon volume on colorectal, colon and rectal cancer surgery for overall five year survival, however, remained significant in favour of higher surgeon caseload (HR=0.88, 95% CI 0.83 to 0.93).

Five‐year disease specific survival for unadjusted studies

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Surgeon volume (unadjusted analysis), Outcome 2 Five year disease specific survival.

Only one study on 1,416 colorectal cancer patients (McArdle 2004) was found to report on the disease‐specific survival; it demonstrated no significant surgeon volume‐outcome association (HR=0.88, 95% CI 0.75 to1.03).

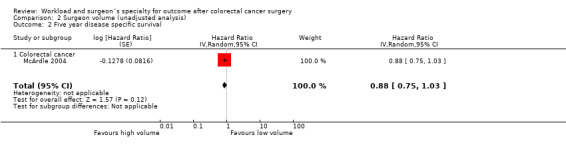

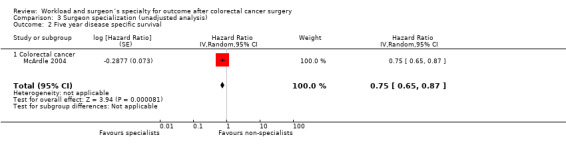

Five‐year disease specific survival for studies with case‐mix adjustment

5.2. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Surgeon volume (adjusted analysis), Outcome 2 Five year disease specific survival.

In case‐mix adjusted analysis, the same study (McArdle 2004) did also not demonstrate a significant effect for higher surgeon caseload, both for colon cancer (HR=0.99, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.29) and rectal cancer (HR=0.88, 95% CI 0.65 to 1.19).

Operative mortality for unadjusted studies

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Surgeon volume (unadjusted analysis), Outcome 3 Inpatient and 30 day mortality.

Meta‐analyses of five colorectal cancer studies (Harmon 1999; McArdle 2004; Mella 1997; Parry 1999; Rogers 2006), including 23,644 patients, seven colon cancer studies (Billingsley 2007; Borowski 2010; Drolet 2011; Finlayson 2003; Hannan 2002; Morris 2007; Schrag 2003) including 152,231 patients, and four rectal cancer studies (Borowski 2010; Martling 2002; McGrath 2005; Schrag 2002) including 5,740 patients, showed significant associations between surgeon caseload and mortality in favour of high volume (OR=0.65, 95% CI 0.56 to 0.76, OR=0.62, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.76, and OR=0.73, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.98, respectively). There was minimal heterogeneity between colorectal cancer studies and rectal cancer studies (I2=9% and I2=28%, respectively), and significant heterogeneity between colon cancer studies (I2=89%). The overall effect of surgeon volume on colon, rectal and colorectal patients across all studies was significant (OR=0.65, 95% CI 0.57 to 0.75). Both US based (Billingsley 2007; Drolet 2011; Finlayson 2003; Hannan 2002; Harmon 1999; Rogers 2006; Schrag 2002; Schrag 2003) and non‐US based studies (Borowski 2010; Martling 2002; McArdle 2004; McGrath 2005; Mella 1997; Morris 2007; Parry 1999) reported significant associations between surgeon caseload and mortality (OR=0.63, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.74, and OR=0.73, 95% CI 0.54 to 0.97, respectively)

Operative mortality for studies with case‐mix adjustment

5.3. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Surgeon volume (adjusted analysis), Outcome 3 Inpatient and 30 day mortality.

Meta‐analyses of four colon cancer studies (Borowski 2010; Billingsley 2007; Drolet 2011; Rogers 2006), including 57,995 patients, showed a significantly lower risk of operative death in favour of high volume surgeons (OR=0.75, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.92). There was significant heterogeneity between studies (I2=71%). However for rectal cancer surgery, meta‐analyses of two studies (Borowski 2010; Rogers 2006) assessing 5,537 patients did not show significant odds in favour of high volume surgeons (OR=0.86, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.19). There was no heterogeneity between the rectal cancer studies (I2=0%). The overall effect of surgeon volume on colon and rectal cancer surgery combined was significant in favour of higher caseload (OR=0.77, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.91), and there was no difference between US‐based (Billingsley 2007; Drolet 2011; Rogers 2006) and one non‐US based study (Borowski 2010) that reported case‐mix adjusted data (OR=0.81, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.99, and OR=0.66, 95% CI 0.51 to 0.87, respectively).

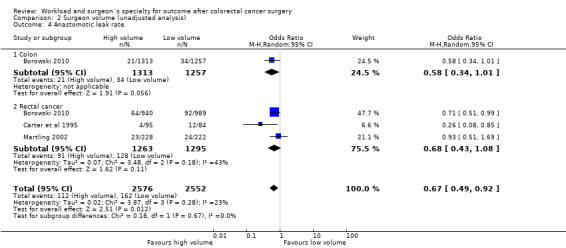

Anastomotic leak rate for unadjusted studies

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Surgeon volume (unadjusted analysis), Outcome 4 Anastomotic leak rate.

One study (Borowski 2010) assessed the risk of anastomotic leaks for 2,570 patients with colon cancer in favour of high volume surgeons, but this failed to reach statistical significance (OR=0.58, 95 %CI 0.34 to 1.01). Meta‐analyses of three rectal cancer studies (Borowski 2010; Carter et al 1995; Martling 2002) assessing a total of 2,558 patients did also not show a significant difference in anastomotic leak rate in favour of high volume surgeons (OR=0.68, 95%CI 0.43 to 1.08); there was moderate heterogeneity between the rectal cancer studies (I2=43%). However, the overall effect of surgeon volume on colon and rectal cancer surgery was significantly in favour of high‐volume surgeons (OR=0.67, 95% CI 0.49 to 0.92).

Anastomotic leak rate in studies with case‐mix adjustment

5.4. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Surgeon volume (adjusted analysis), Outcome 4 Anastomotic leak rate.

One study (Borowski 2010) assessed the risk of anastomotic leakage in a population of 2,570 colon cancer and 1,929 rectal cancer patients, with no significant effect in either group (OR=0.66, 95 %CI 0.36 to 1.21, and OR=0.61, 95 %CI 0.29 to 1.28, respectively), or combined for all included colorectal cancer patients (OR=0.64, 95%CI 0.40 to 1.02)

Permanent stoma rate for unadjusted studies

2.5. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Surgeon volume (unadjusted analysis), Outcome 5 Permanent stoma rate.

The meta‐analyses of three rectal cancer studies (Borowski 2010; Carter et al 1995; Martling 2002), including 2,235 patients, showed a significantly lower risk of permanent stoma for high‐volume surgeons (OR= 0.75, 95 % CI 0.62 to 0.89). There was no heterogeneity between the studies (I2=0%).

Permanent stoma rate for studies with case‐mix adjustment

5.5. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Surgeon volume (adjusted analysis), Outcome 5 Permanent stoma rate.

Two rectal cancer studies (Borowski 2010; Rogers 2006), assessing 8,955 patients, demonstrated showed significantly lower risk of a permanent stoma for surgery carried out by high‐volume surgeons (0.75, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.88) . There was no heterogeneity between the studies (I2=0%).

APER rate for unadjusted studies

2.6. Analysis.

Comparison 2 Surgeon volume (unadjusted analysis), Outcome 6 Abdominoperineal excision of the rectum.

In the meta‐analyses of seven rectal cancer studies (Harmon 1999; Martling 2002; Marwan 2010; McGrath 2005; Parry 1999; Purves 2005; Schrag 2002), assessing a total of 4,348 patients showed significantly lower risk of APER for patients operated on by a high‐volume surgeons (OR=0.66, 95%CI 0.52 to 0.84); there was significant heterogeneity between studies (I2=62%).

APER rate for studies with case‐mix adjustment

5.6. Analysis.

Comparison 5 Surgeon volume (adjusted analysis), Outcome 6 Abdominoperineal excision of rectum rate.

One study examined the risk of APER (Purves 2005) in a cohort of 180 rectal cancer patients, with significantly lower risk for those patients treated by high‐volume surgeons (OR=0.75, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.88).

Surgeon Specialization

Overall 5‐year survival for unadjusted studies

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 Surgeon specialization (unadjusted analysis), Outcome 1 Overall five year survival.