Abstract

Adsorbent materials with humidity-modulated CO2 sorption capacities are essential for direct air capture (DAC) based on moisture swing adsorption (MSA) processes. These materials have seldom been studied in the context of dynamic breakthrough experiments despite their efficacy in providing valuable equilibrium and kinetics information on the adsorbents and their resemblance to practical processes at large scales. Herein, we performed a series of breakthrough experiments to systematically investigate the DAC properties of the MSA adsorbent IRA-900-C. Prepared from the commercially available anion exchange resin IRA-900 (chloride form), IRA-900-C exhibits a CO2 capacity of 1.92 mmol g–1 at 20% RH at 25 °C. The CO2 uptake capacity in IRA-900-C decreases as the environmental relative humidity (RH) increases at constant temperature. The competitive sorption behavior of CO2 and H2O is also revealed by humid CO2 breakthrough experiments. Breakthrough experiments with different gas velocities and particle sizes of IRA-900-C suggest that the CO2 adsorption kinetics in IRA-900-C is controlled by internal mass transfer resistances under DAC conditions. A theoretical maximum CO2 working capacity of 1.27 mmol g–1 can be achieved with IRA-900-C by swinging the RH from 20 to 50% RH at 25 °C along with constant purge of inert gas, and the feasibility of CO2 production in a vacuum is experimentally verified. This study highlights the significance of dynamic breakthrough experiments in evaluating the DAC performance of MSA sorbents and providing valuable information for the design and optimization of DAC systems enabled by moisture swing processes.

Keywords: direct air capture, moisture swing adsorption, anion exchange resins, dynamic breakthrough experiments, competitive adsorption, vacuum desorption

Short abstract

Breakthrough experiments are employed to investigate the equilibrium and kinetic CO2 capture properties of moisture swing adsorbents.

1. Introduction

Most direct air capture (DAC) technologies employed today are based on CO2 scrubbing by alkaline solutions, CO2 reactive sorption by alkali carbonates, or CO2 adsorption in porous materials such as zeolites, silica, aerogels, and metal–organic frameworks (MOFs).1 The regeneration of sorbents in these systems is essential for pseudo-steady state DAC operation, and the various regeneration processes have significant impacts on the CO2 purity and productivity as well as the energy consumption of the DAC processes.2

DAC based on moisture swing adsorption (MSA) proposed by Lackner et al. was one of the first DAC cycles proposed. In this cycle, the CO2 sorbent is regenerated by exposure to high-activity water vapor or liquid water.3,4 Most MSA sorbents contain polymeric matrices with quaternary ammonium (QA) moieties and charge-balancing anions of weak acids. The proposed mechanism of MSA is shown in Scheme 1. When the environmental relative humidity (RH) is low, the hydrated anions Ax–·nH2O hydrolyze to form OH–, which further reacts with CO2 to form HCO3–; the reaction reverses to release CO2 and regenerate the sorbent at high RH conditions.5,6 Strong base anion exchange resins based on cross-linked polystyrene are the most commonly reported MSA sorbents because they can be easily prepared from off-the-shelf resin precursors.7,8 In addition, aerogels and linear polymers such as PES and cellulose with QAs have recently emerged as MSA sorbents.9−12 In terms of the anions in MSA sorbents, a library of anions such as CO32–, PO43–, and B4O72– has been demonstrated to endow the sorbents with humidity-sensitive CO2 capturing properties, but sorbents with other anions have exhibited very limited swingable CO2 sorption capacity.13,14

Scheme 1. Proposed Mechanism of DAC Based on MSA5.

To date, most prior studies have investigated the CO2 capture performance of MSA sorbents using the closed volumetric method. A typical evaluation system of this method is primarily composed of a sample chamber, a pump for forced convection in the system, a humidifier to regulate the system humidity, a gas injection port, and a gas composition analyzer to monitor CO2 and H2O concentrations in the system. The CO2 adsorption or desorption capacities of MSA sorbents are therefore determined by the initial and final CO2 concentrations in the system with pre-calibrated constant volume, while the sorption kinetics is inferred from the dynamic profiles of CO2 concentrations.15−20 Although it is a useful way to acquire CO2 sorption kinetics and changes in CO2 uptakes between different testing conditions using such systems, it is challenging to accurately measure H2O uptakes of the sorbents because humidity levels are usually maintained constant by the humidifier during the CO2 adsorption/desorption experiments, which could be obstacles for the accurate calculation of the energy requirements and subsequent technoeconomic analyses of MSA processes. Prior studies assumed that the weight gain of MSA sorbents during CO2 desorption steps was mainly attributed to H2O adsorption because the amount of desorbed CO2 was negligible.16 This hypothesis may not apply to MSA sorbents with high CO2 uptake and significant levels of hydrophobicity. In addition, the closed volumetric method does not offer information on column dynamics of the CO2 capture bed, which reflects the sorbents’ sorption properties (both thermodynamics and kinetics), dispersion, and thermal behavior of the packed bed. Such information is critical for scaling up MSA technologies.

Dynamic breakthrough experiments, a category of open volumetric methods, have been widely employed to study the performance of sorbents for gas-phase chemical separation applications such as CO2 capture, hydrocarbon separations, and air separations.21 In a typical breakthrough experiment, a gas stream is fed into a packed bed continuously, and the gas compositions and flow rates at the outlet of the packed bed are recorded to generate breakthrough curves. The uptakes of the sorbates can be calculated from their corresponding breakthrough curves, and the sorption kinetic parameters can be derived by fitting the breakthrough curves with computational breakthrough models that take all factors (e.g., sorbent properties, axial dispersion, thermal effects, etc.) into consideration. As breakthrough experiments resemble the sorption steps of practical separation processes, they provide valuable connections between bench-scale lab experiments and pilot or commercial chemical separation processes. Nevertheless, very few prior studies have investigated MSA sorbents using dynamic breakthrough experiments under DAC-relevant conditions.16,22,23

In this work, we present the systematic evaluation of an MSA sorbent based on off-the-shelf resin IRA-900 using dynamic breakthrough experiments. CO2 uptake capacities in the MSA sorbent were measured under different temperatures and humidities. In addition to the CO2 adsorption and desorption properties, the H2O coadsorption capacity of the sorbent during CO2 capture experiments was also carefully studied. We envision that this work will be a useful guideline for the evaluation of MSA sorbents with breakthrough experiments.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals

Amberlite IRA-900 chloride form and KHCO3 (ACS reagent, 99.7%) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. K2CO3 (ACS reagent, 99.0%) was purchased from VWR Chemicals BDH. DI water was obtained from an Elga PureLab Option S7 water purification system. Cylinders of N2 (99.995%), Ar (99.995%), and N2 with different concentrations of CO2 (400 ppm, 1000 ppm, 1%) were purchased from Airgas.

2.2. Characterizations

Elemental analysis was conducted by Atlantic Microlab. SEM. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images were obtained with a Hitachi SU8010. Before imaging, samples were sputtered with a Quorum Q-150T ES for 40 s. Unary water vapor adsorption isotherms were obtained with a TA Instruments VTI-SA+ after the in situ activation of samples by N2 purging at 35 °C for 12 h.

2.3. Preparation of IRA-900-C

IRA-900-C was synthesized via a series of ion exchange processes. Typically, about 1 g of IRA-900 beads in their chloride form were soaked in 40 mL of 1 M KHCO3 aqueous solution with gentle shaking. The aqueous supernatant was decanted after 24 h, and the beads were washed by DI water until the washing liquid was neutral (pH = 7). The beads were redispersed in 40 mL of fresh 1 M KHCO3 aqueous solution for another round of ion exchange, which was repeated until no Cl– could be detected by Ag+ titration with Mohr’s method. The beads were washed by DI water thoroughly before drying in the fume hood at room temperature (23 °C).

2.4. Dynamic Breakthrough Experiments

A schematic illustration of the setup for breakthrough experiments is shown in Scheme 2. The mass flow controllers (MFCs) in the setup were purchased from Alicat Scientific. The CO2 and water vapor concentrations at the outlet of the adsorption bed were measured by an infrared gas analyzer LI-850-1 produced by LI-COR Environmental, and the relative humidities (RH) in the system were cross-checked by a RH and temperature probe HMP8 of Vasaila. Humid gas streams were generated by flowing N2 or CO2/N2 through the customized bubblers that can withstand buildup pressures of the packed bed of IRA-900-C, and the relative humidities were controlled by adjusting the flow rates of dry and humid streams. The whole setup was placed in a thermalized chamber programmed at specific temperatures to prevent water condensation in the system.

Scheme 2. A Scheme of the Breakthrough Setup (Open Volumetric) Used for the Evaluation of MSA Adsorbents.

The whole setup is placed in a thermalized chamber with temperature control for measuring CO2 uptakes at different relative humidities (RHs) at 35 °C to prevent water condensation in the system.

A typical breakthrough experiment is described as follows. IRA-900-C resins after anion exchange (110–300 mg) were packed into a 1/4″ stainless steel column whose both ends were blocked by stainless steel meshes to prevent the resin particles from leaving the bed during the breakthrough experiment. The bed was activated by humid inert gas (200 sccm Ar or N2) with an RH greater than 85% at 25 °C overnight until the CO2 concentrations detected at the outlet of the bed were stable and less than 3 ppm. A stabilized stream of 400 ppm CO2 balanced by N2 (200 sccm) with a desirable RH was then introduced into the bed at 25 °C, and the concentrations of CO2 and H2O at the outlet of the bed were recorded. The bed was determined to be saturated by the feeding of CO2 when the outlet CO2 concentration was equal to the feeding concentration. The bed was regenerated under humid inert gas (200 sccm Ar or N2) with an RH greater than 85% at 25 °C overnight before being purged by a flow of dry inert gas (500 sccm N2) to determine the dry mass of sorbent used in the breakthrough experiment.

2.5. CO2 Desorption under Vacuum

A schematic illustration of the closed volumetric setup for CO2 desorption in a vacuum under forced convection is shown in Scheme 3. In a typical experiment, a diaphragm pump was kept running to force convection within the system. Water in the reservoir was first frozen before evacuating the system for 30 s with a Pfeiffer DUO 2.5 dual-stage rotary vane vacuum pump. The vacuum degree was about −95 kPa. The vacuum pump was then isolated, and the ice in the water reservoir was thawed to release dissolved gases. The freeze–pump–thaw cycles were repeated three times before warming up the water reservoir to 30 °C to achieve target RH levels in the system for sorbent regeneration (while other parts of the system remained at ambient temperature). The water partial pressure of the setup was monitored by Vasaila HMP8, and the gas compositions in the system were probed by a mass spectrometer Pfeiffer Omnistar GSD 320.

Scheme 3. A Scheme of the Experimental Setup (Closed Volumetric) for the Regeneration of MSA Adsorbents by Water Vapor in Vacuum.

Arrows indicate the flowing direction of water vapor when the circulation pump is in operation.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Structural Characterization of the MSA Adsorbent

IRA-900 is an anion exchange resin based on macroporous cross-linked copolymers of styrene and divinylbenzene. Quaternary ammonium (QA) sites are covalently grafted onto the polymer backbones of IRA-900, and the positive charges are balanced by chloride anions that can be substituted by other anions via anion exchange (Scheme 1). There have been several prior works that studied the CO2 capture performance of IRA-900 derivatives. He et al. reported that IRA-900 with triazine anions exhibits a CO2 uptake as high as 4.02 mmol g–1 at 0.15 bar and 25 °C, outperforming IRA-900 with other anions under the same conditions.7 Wang et al. studied IRA-900 along with other anion exchange resins with different basicity and revealed that the form of QA sites determine CO2 uptake capacities, while the textural properties affect CO2 sorption kinetics under conditions relevant to direct air capture of CO2 (DAC).24 A recent study by Hegarty et al. screened a variety of anions of IRA-900 and revealed that IRA-900 with pyrophosphate possesses the highest CO2 swing capacity per ammonium site when the relative humidity (RH) in the closed chamber was increased from 20 to 65%.25

In this work, rather than comparing the DAC performance of different IRA-900 resins, IRA-900 balanced by HCO3–/CO32– was selected as the model material to develop the evaluation system of MSA sorbents based on dynamic breakthrough experiments. The anion exchange experiment was initially performed by immersing IRA-900 beads in a 0.5 M K2CO3 aqueous solution. However, the resin dispersion emitted a fishy odor after anion exchange, hinting at the decomposition of IRA-900 and the release of trimethylamine under high pH conditions, even though the extent of decomposition might be very low. Subsequent anion exchange experiments were carried out in 1 M KHCO3 aqueous solution, during which the fishy odor was not noticed. The anion-exchanged IRA-900 (denoted as IRA-900-C) was then dried in a fume hood at room temperature before being packed into a column for breakthrough experiments. The macroporous nature of IRA-900 was preserved after anion exchange, as examined by scanning electron microscope (SEM), but the surface of IRA-900-C was smoother, probably due to particle attrition during the anion exchange process (Figures 1a and S1). Only trace amounts of chlorine could be detected in IRA-900-C (Figure 1b and Table S1), which, along with titration tests, suggests almost complete anion exchange from Cl– to HCO3–. The amount of QA moieties in IRA-900 was calculated to be 4.18 mmol g–1 based on the N content of the resin determined by elemental analysis. Therefore, a maximum of 2.09 mmol g–1 OH– can be generated in the resin via HCO3– hydrolysis under low RH conditions according to Scheme 1.4 It should be noted that it is challenging to obtain fully dehydrated IRA-900-C due to its tendency of decomposition in the dry state. Therefore, the residual water molecules in the resins, though minimal, will lead to a slightly overestimated dry mass of the resin and an underestimated N content and QA concentrations in the resin. The average diameter of IRA-900-C beads is 614 μm, and the particle size distribution is shown in Figure S2.

Figure 1.

(a) FE-SEM images of IRA-900-C. The inset shows the macroporous surface texture of IRA-900-C. (b) Elemental compositions of IRA-900 and IRA-900-C.

3.2. CO2 Adsorption Capacities of IRA-900-C

Figure 2a shows the 400 ppm CO2 breakthrough curves of the initial two breakthrough experiments using a packed bed of IRA-900-C. The column was purged by dry N2 at room temperature until no CO2 was observed at the column outlet according to the CO2 and H2O IR analyzer before the first breakthrough experiment. Although this is a mild activation method, it is sufficient to desorb physisorbed CO2 from the packed bed if there is any while still retaining chemisorbed CO2 in the form of HCO3– (which should require moisture to desorb). Interestingly, only a negligible amount of CO2 (0.1 mmol g–1) was adsorbed by the column at 23 °C and 23.4% relative humidity (RH) after the dry inert gas activation step, indicating the ultrasmall population of CO2 physisorption sites in IRA-900-C. As prior works have reported the activation of MSA sorbents under high RH atmosphere, the column was subsequently purged by humid Ar with a RH of 80% at 23 °C overnight before the second breakthrough experiment. CO2 uptake in the column was dramatically increased to 1.76 mmol g–1 after the activation step with humid Ar, which underscores the moisture swing properties of IRA-900-C. Interestingly, when dry 400 ppm CO2 is used for the breakthrough experiment, the CO2 uptake kinetics was slower as suggested by the more dispersed breakthrough profile, and the CO2 uptake was much lower (0.97 mmol g–1) after 6 h of the experiment even though the bed was fully activated in humid Ar (Figure S3b, 3rd run test). Further overnight purging by dry Ar did not recover any CO2 uptake capacity (Figure S3b, 4th run test). These experiments demonstrate the essential role of water vapor in both CO2 adsorption and desorption in IRA-900-C. Water vapor coadsorbed in IRA-900-C in the CO2 capture step helps dilate the resin and open the CO2 diffusion pathway toward otherwise inaccessible/hard-to-access sorption sites, and water vapor also drives the release of CO2 and converts HCO3– to CO32– in the desorption step for subsequent CO2 adsorption cycles. Encouraged by the MSA phenomena observed by breakthrough experiments, the anion exchange experiments were repeated, and a new batch of IRA-900-C was used for repetitive breakthrough experiments using 400 ppm CO2 at 25 °C and 21% RH. The IRA-900-C column was purged by humid Ar with 84 ± 1% RH at 25 °C overnight after each adsorption experiment. The resin exhibited consistent CO2 uptake capacities over 10 cycles with an average CO2 uptake capacity of 1.92 mmol g–1 at 400 ppm CO2 (Figures 2b and S4). As the majority of CO2 is captured by the reaction between CO2 and OH–, more than 90% of OH– in IRA-900-C is utilized for CO2 capture based on the QA concentration in IRA-900 and the stoichiometry between QA and OH– (two QA sites are balanced by one HCO3– and one OH–). The utilization efficiency of OH– under this circumstance is significantly greater than the amine efficiency of DAC solid adsorbents, which rarely exceeds 25%.26,27

Figure 2.

(a) CO2 breakthrough curves of the IRA-900-C packed bed before and after full activation. These curves were obtained using 400 ppm CO2/balance N2 with 0.58 mol % H2O (23.4% RH) at 23 °C. The dry mass of IRA-900-C in the bed was 357.0 mg. (b) CO2 adsorption capacities in IRA-900-C over 10 cycles of breakthrough experiments using 400 ppm CO2/balance N2 with 0.66 mol % H2O (21% RH) at 25 °C.

The CO2 uptake in IRA-900-C is higher than what has been reported in the literature earlier (∼0.76 mmol g–1),13,24 which might be attributed to the different methodologies of determining CO2 uptakes used in this work and prior studies. Most of the prior works on MSA adsorbents calculated CO2 uptakes based on the concentration changes of CO2 in a system with constant volume as a result of the changes in RH. These uptakes are relative CO2 uptakes between two humidity levels or CO2 working capacity of the sorbent, and they will converge to the true CO2 uptake at the lower RH condition when the absolute CO2 uptake in the sorbent under regeneration conditions approaches zero. In contrast, as high RH inert gas purging was adopted as the regeneration step to maximize both chemical (water activity) and physical (CO2 partial pressure) driving forces for CO2 desorption in this work, the CO2 uptakes determined from breakthrough experiments most likely represent the absolute CO2 uptakes in the IRA-900-C.

A series of breakthrough experiments using 400 ppm CO2 with different water content were carried out at different temperatures to investigate the effects of moisture and temperature. The CO2 uptakes obtained from these breakthrough experiments were plotted against different humidity levels and are shown in Figures 3a and S5. CO2 uptakes are generally higher at lower temperatures under similar RH conditions, which reflects the exothermic nature of the CO2 adsorption. Interestingly, IRA-900-C possesses comparable CO2 uptakes (∼1.9 mmol g–1) under relatively dry conditions (RH < 30%) at all investigated temperatures, suggesting a nearly full coverage of CO2 sorption sites by 400 ppm CO2 even at 35 °C. CO2 uptakes only decrease slightly at the low RH region but suffer a greater decline when RH increases, and the effects of RH are more pronounced when temperatures are higher. The difference between CO2 uptakes at 21 and 86.5% RH at 25 °C is about 0.88 mmol g–1, which is similar to the literature value determined in a constant-volume system.24 The results in Figure 3a clearly showcase the dependence of CO2 uptakes on RH at different temperatures, which are consistent with what has been reported in similar MSA sorbents based on ion exchange resins. These results also suggest that a greater CO2 productivity can be achieved by spending additional energy input to slightly increase desorption temperatures in an MSA process. A recent modeling study suggests that heating the MSA sorbents during the desorption step can improve the thermodynamic efficiency of the overall DAC process.28

Figure 3.

(a) CO2 adsorption capacities in IRA-900-C at a CO2 composition of 400 ppm (total pressure 1 bar) as a function of RHs at 15, 25, and 35 °C. (b) CO2 adsorption capacities at different CO2 compositions under dry (20.5 ± 1%) and humid (83 ± 1%) conditions at 1 bar and 25 °C.

In addition to the significant impacts of RH on the CO2 uptake capacities, the hydration degree of resins at the beginning of breakthrough experiments also affects the CO2 uptake capacities and kinetics, the relationship of which has been relatively less investigated compared to the relationships between RH and CO2 uptakes. As shown in Figure S6a, the CO2 concentration at the column outlet increased continuously from the beginning of the breakthrough experiment using a column pre-dried to the humid level of the feeding gas after column regeneration under a high RH atmosphere. In comparison, the CO2 breakthrough curve of a column without the pre-drying step shows a stepwise profile with a similar early CO2 breakthrough moment as shown in Figure S6b. Both experiments afford comparable CO2 uptake capacities under equilibrium, despite the different shapes of breakthrough curves. Theoretically, the pre-dried bed of IRA-900-C should have more OH– sites for CO2 adsorption due to the hydrolysis of CO32– at low RH conditions and hence afford a sharper CO2 breakthrough profile than that of the column without the pretreatment, assuming that the mass transfer rates of CO2 are comparable in both columns. The discrepancy between the experimental observation and theoretical analysis suggests a slower CO2 mass transfer kinetics in the pre-dried column, which is likely due to the narrower diffusion pathways for CO2 in the less-dilated resin sorbents. In addition, the different CO2 uptake kinetics could be attributed to the greater diffusion coefficients of all ionic species at higher RHs due to the more connected water network in the pores. The interactions between the QA sites and negatively charged species are also interrupted by water in the vicinity, according to recent simulation findings.29,30 When the resin was purged by dry N2 overnight before the breakthrough experiment, the level of uptake of CO2 in this resin was even lower than those of resins with greater hydration degrees before the breakthrough experiments (Figure S6c). We surmise that the accessibility of quaternary ammonium sites is greatly inhibited in the severely dehydrated IRA-900-C. As the polystyrene backbone of IRA-900-C is hydrophobic, rehydrating IRA-900-C with a moderate level of humidity (the humidity used for the breakthrough experiment) may be insufficient to release all active sites trapped in hydrophobic domains, leading to the compromised CO2 uptake capacity. In comparison, when IRA-900-C is fully hydrated after exposure to 85% RH N2, the resin is fully swollen, and the active sites remain accessible for CO2 sorption even though H2O desorbs from IRA-900-C gradually during the breakthrough experiment.

Unary CO2 uptake isotherms of common CO2 adsorbents have been routinely measured by using commercial gas sorption analyzers. Nevertheless, the coadsorption capacities of CO2 in the presence of water, which are important metrics for DAC sorbents, especially those for MSA processes, have been investigated less. Breakthrough experiments of gas streams with various CO2 compositions were conducted to measure CO2 uptake isotherms of IRA-900-C at dry (20.5 ± 1% RH) and humid (83 ± 1% RH) conditions at 25 °C, and the results are presented in Figure 3b. IRA-900-C loses CO2 uptake significantly as the CO2 composition decreases under the high RH condition. In comparison, CO2 uptake only drops about 15% as the CO2 composition decreases from 400 to 100 ppm under the low RH condition. CO2 increases substantially when the composition of CO2 increases up to 1%, which is attributed to the physisorption of CO2 in the highly polar pore environment of IRA-900-C. CO2 uptakes at high CO2 compositions (1000 and 1%) also exhibit a similar dependence on relative humidity as the CO2 uptakes at 400 ppm (Figure S7). It is worth noting that the CO2 uptake at 1% CO2 composition and 83% RH at 25 °C (2.17 mmol g–1) is greater than the uptake at 400 ppm CO2 and 20% RH (1.92 mmol g–1) at the same temperature. As a result, only a small fraction of captured CO2 could be desorbed from IRA-900-C under humid conditions (e.g., 83% RH) at 25 °C as IRA-900-C reaches a new equilibrium with the desorbed CO2 in the free volume of a closed system, even though the CO2 partial pressure is still relatively low. Higher desorption temperature or continuous removal of desorbed CO2 out of the system to maintain a low CO2 partial pressure would be necessary to achieve meaningful CO2 desorption. Interestingly, the CO2 uptake at 1% CO2 composition at 20% RH, 35 °C in IRA-900-C is even higher than the uptake at the same CO2 partial pressure and 25 °C (Figure S8). Although this abnormal observation appears to violate the thermodynamics of adsorption, it has been reported for DAC solid sorbents based on supported amines, and the observed lower CO2 uptakes at relatively low temperatures are attributed to CO2 mass transfer limitations and insufficient equilibrium time.31 We speculate that more available CO2 sorption sites and faster diffusion kinetics of gas/ionic species synergistically contribute to the observed enhancement of the CO2 uptake capacity at 35 °C.

3.3. Analysis of CO2 Mass Transfer Resistances in IRA-900-C

The mass transfer information on different gas components in addition to their pseudo-equilibrium uptake capacities is crucial for the development of optimal DAC processes based on MSA sorbents with high CO2 productivity and low costs.32 CO2 from the bulk flow needs to travel through the thin film boundary layer, the macropores, and the polymer bulk of IRA-900-C before OH– is combined to form HCO3–, as shown in Figure 4a. Prior works have built models to derive the mass transfer resistances and gas diffusivities of CO2 or H2O in MSA sorbents based on CO2 concentration profiles or mass changes of the sorbents in the closed system.15,19,33 In this work, a series of breakthrough experiments were carried out to identify the primary mass transfer resistance in IRA-900-C under conditions related to DAC. First, streams of 400 ppm CO2 containing 0.63 mol % H2O (20% RH) at different velocities were fed into the bed of IRA-900-C, which was pre-dried at the humidity level of the CO2 streams at 25 °C. The CO2 breakthrough curves of these experiments were plotted in Figure 4b where the x axes of the breakthrough curves were normalized according to the gas velocities, the bed porosity, and bed length. Although increasing the flow rates of CO2 streams do not affect the pseudo-equilibrium CO2 uptake capacities in IRA-900-C, faster gas velocities led to earlier CO2 breakthrough moments and wider mass transfer zones. As we estimate that adsorption heat and axial dispersion have only minor contributions to the broadening of the mass transfer zone (detailed discussion in the Supporting Information), we surmise based on these results that the internal mass transfer processes, namely, CO2 diffusion in the macropores of the resin and CO2 diffusion in the bulk of the cross-linked polystyrene frameworks, or the reaction kinetics of bicarbonate formation, control the rate of CO2 adsorption.

Figure 4.

(a) Schematic illustration of CO2 transport from the gas bulk to the sorption sites where CO2 is converted to HCO3–. (b) CO2 breakthrough curves of the IRA-900-C packed bed using 400 ppm CO2/balance N2 with 0.63 mol % H2O (20% RH) and different linear velocities 25 °C. The IRA-900-C bed was pre-equilibrated with N2 carrying 0.63 mol % H2O (20% RH) at 25 °C before the breakthrough experiment. The breakthrough curves are plotted with dimensionless breakthrough time, which is converted from the actual breakthrough time t (s) based on the linear velocity of the feeding gas v (m s–1), bed porosity εb, and the bed length L (m).

Prior work has observed faster CO2 sorption kinetics in IRA-900 with smaller particle sizes in a constant-volume sorption chamber.24 To understand how particle sizes affect the CO2 sorption kinetics in IRA-900-C under dynamic conditions, IRA-900 was ground by ball milling at cryogenic temperatures before being subjected to anion exchange and particle sieving for breakthrough experiments. The ground IRA-900-C sample is denoted as IRA-900-C-g. As shown in Figure S9a, the ground resin shows a particle size distribution of 10-100 μm, which is about 1/10 of the size of the IRA-900-C beads. SEM revealed the retention of the resin’s macropores after cryogrinding (Figure S9b). IRA-900-C-g possesses a comparable CO2 uptake capacity to that of IRA-900-C beads but different CO2 column dynamics under the same RH and temperature conditions (Figure S9c). The CO2 breakthrough curve of the IRA-900-C-g column showed a sharper profile at the beginning (C C0–1 < 0.5) followed by a gradual-slope profile at the later stage of the breakthrough experiments compared to the breakthrough curve of the IRA-900-C column, indicating an initial regime with relatively faster CO2 uptake kinetics at the beginning followed by a later stage with a noticeable slower sorption kinetics as CO2 loading in IRA-900-C-g increases. We surmise that the larger external surface area of IRA-900-C-g results in faster CO2 uptake kinetics at the initial stage of the breakthrough experiment. As more CO2 is adsorbed in IRA-900-C-g, water desorption occurs faster and the resin particle contracts to a greater extent (vide infra), resulting in the slower CO2 adsorption kinetics at the later stage of the experiment. Interestingly, no obvious differences in CO2 desorption kinetics were observed for IRA-900-C and IRA-900-C-g (Figure S9d), suggesting that the factors independent of particle sizes such as CO2 diffusion in the polymer bulk and reaction kinetics (step C and D in Figure 4a) play significant roles in affecting the overall CO2 sorption kinetics. A detailed modeling study based on breakthrough experiments or other techniques such as zero column length chromatography (ZLC) and frequency response method will be required to fully elucidate the relative contributions of each mass transfer component to the overall CO2 mass transfer performance.32,34,35

3.4. H2O Adsorption in IRA-900-C

Water management is a critical challenge for the DAC processes. It is crucial to understand the water sorption behavior in MSA sorbents so that a judicious water management strategy can be employed for optimal DAC capacities and levelized carbon capture cost.36−38 Unary pseudo-equilibrium water uptakes in IRA-900 and IRA-900-C were measured gravimetrically at 25 °C and shown in Figure 5a. Water uptakes in the resins increased slowly and linearly at low RH region (RH < 45%) and rapidly increased as RH approached the saturation state (> 80%) due to water clustering around the hydrophilic QA sites. Water uptakes in IRA-900-C are slightly higher than those in the precursor under the same RH condition. We speculate that this might be attributed to the larger dimensions of HCO3– and the hydration layer compared to Cl–. Water uptakes at 20 and 85% RH were 7.1 and 28.4 mmol g–1, respectively. It is noteworthy that water uptakes in the resin in the DAC processes could possibly deviate significantly from the unary pseudo-equilibrium uptakes because of the competitive adsorption of CO2 with water vapor, which has been observed in other CO2 adsorbents.39−43 Determining the coadsorption capacities of CO2 and H2O in MSA sorbents with gravimetric methods is nonideal because it is challenging to deconvolute the contribution of CO2 and H2O sorption to the weight changes of samples.15,22 Prior studies have assumed that the adsorption/desorption of water vapor as a result of changing RHs in the constant-volume systems is the primary reason for the sample weight changes.5,6,14 In contrast, breakthrough experiments allow the simultaneous calculation of the sorption capacities of different adsorbates by integrating the corresponding breakthrough curves. In order to determine the water coadsorption capacity in IRA-900-C during CO2 adsorption, breakthrough experiments of humid 400 ppm CO2 were performed after the IRA-900-C bed had been pre-equilibrated to the RH of the feeding CO2/N2 (∼21% RH) at 25 °C. The CO2 and H2O breakthrough profiles are shown in Figure 5b. The water concentration roll-up at the column outlet indicates immediate water desorption along with the introduction of CO2 into the bed. Water concentration gradually equilibrated to the feed concentration at the end of the breakthrough experiment, suggesting that CO2 adsorption leads to water desorption from the resin. Integrating the water breakthrough curves of three repeated breakthrough experiments yields an average desorbed water capacity of −5.7 mmol g–1, which along with the unary water uptake at 20% RH yields the coadsorbed water uptake of around 1.4 mmol g–1 under this condition. The CO2:H2O coadsorption ratio of 1.34 in IRA-900-C is substantially higher than those of typical DAC sorbents such as supported amines, which usually have noticeably higher H2O uptakes (a CO2:H2O coadsorption ratio of less than 0.2 is not uncommon, depending on the sorbent properties and RHs of DAC conditions).36

Figure 5.

(a) Water vapor adsorption isotherms of IRA-900 and IRA-900-C at 25 °C. The star symbol indicates the estimated uptake of water vapor in IRA-900-C after the breakthrough experiment of 400 ppm CO2/balance N2. (b) CO2 and H2O breakthrough profiles of the IRA-900-C packed bed using 400 ppm CO2/balance N2 with 0.65 mol % H2O (21% RH) at 25 °C. The IRA-900-C bed was pre-equilibrated with N2 carrying 0.65 mol % H2O (21% RH) at 25 °C before the breakthrough experiment. The dry mass of IRA-900-C in the bed was 237.3 mg.

3.5. CO2 Desorption from IRA-900-C

Understanding the CO2 desorption conditions is essential for designing practical DAC processes using MSA adsorbents. Dry N2 purging has been demonstrated as an ineffective method to activate/regenerate IRA-900-C as discussed earlier in this work (Figure 2). Further efforts to evacuate the bed using a rotary vane oil pump at room temperature could not recover the CO2 capture capability of IRA-900-C either (Figure 6a). These results suggest the crucial role of water vapor in triggering the desorption of CO2 from the resin. A series of desorption experiments was conducted by progressively varying the RH of the purging gas to investigate different CO2 desorption conditions. As shown in Figure 6b, 0.39 mmol g–1 of CO2 can be desorbed by switching 400 ppm CO2 to pure N2 without changing the water vapor content. This portion of desorbed CO2 might originate from physically adsorbed CO2 and part of the chemically adsorbed counterpart when the CO2 partial pressure decreases. Additional 0.88 and 0.41 mmol g–1 of CO2 were desorbed from the bed when the RH increased to 50 and 87.5%, respectively. These desorption experiments collectively indicate that a theoretical maximum CO2 working capacity of 1.27 mmol g–1 can be achieved with 50% RH at 25 °C and the timely removal of desorbed CO2 from the system. The discrepancy between the total CO2 desorption capacities and the adsorption capacities calculated from breakthrough experiments could be attributed to the accumulated integration errors for the lengthy desorption experiments. Figure 6c shows the CO2 desorption profiles of the IRA-900-C packed bed using high RH (> 76%) N2 flows at 25 and 35 °C immediately after breakthrough experiments. Increasing the desorption temperature enhances the maximum CO2 desorption rate by 75% under similar RH conditions, and 44% more CO2 can be desorbed from the bed within 1 h of the desorption experiments. These properties of the desorption of CO2 from IRA-900-C resemble other typical DAC systems based on amine adsorbents and reflect the endothermic nature of the desorption of CO2.

Figure 6.

(a) Comparison of the original CO2 breakthrough curve and the breakthrough curve after regeneration of the IRA-900-C packed bed under a vacuum. The dry mass of IRA-900-C in the bed was 237.3 mg. (b) Remaining CO2 uptake capacities in IRA-900-C after desorption by N2 purging with different RHs. (c) Rate of CO2 desorption from the packed bed of IRA-900-C under humid N2 flows at 25 and 35 °C. The inset shows the progress of CO2 desorption at these two temperatures.

3.6. CO2 Production in Vacuum

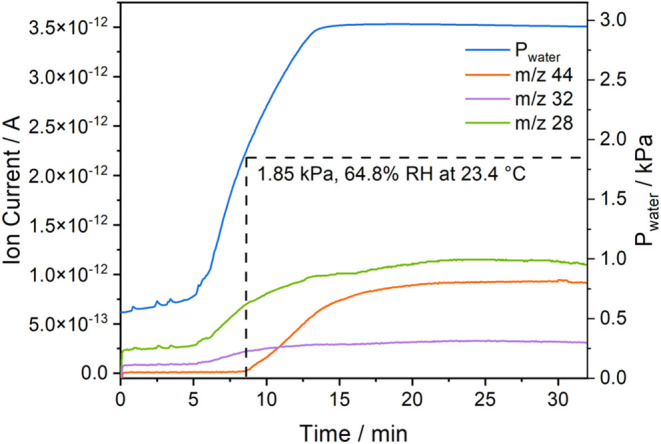

Most works on DAC physisorbents, including the present study, investigate the behavior of CO2 desorption triggered by temperature or moisture swings in a dynamic (e.g., sweeping gas through the bed) or static inert atmosphere. Although these CO2 desorption experiments provide useful information about CO2 desorption capacities and kinetics, such CO2 desorption conditions are impractical for real-world DAC operations as the introduction of inert gases compromises the purity of CO2 produced from the processes. CO2 production in a vacuum is desirable as it eliminates the usage of sweep gases such as steam or N2 used in the desorption step, but relevant experiments have been rarely reported by prior works on MSA sorbents. Therefore, a closed volumetric setup shown in Scheme 3 was designed and constructed to study how water vapor stimulates CO2 desorption from IRA-900-C (saturated by 400 ppm CO2 at 25 °C and 20% RH) in a vacuum under forced convection. Air in the system was evacuated by the roughing vacuum pump, and the dissolved gas in water was also removed by freeze–pump–thaw cycles before increasing the water partial pressure in the system by heating up the water reservoir. A diaphragm circulation pump was deployed in the loop to deliver water vapor from the headspace of the water reservoir to the IRA-900-C bed. As shown in Figure 7, the mass spectrometer ion currents of mass-charge ratios relevant to CO2, O2, and N2, respectively, remained at low levels when water partial pressures were lower than 0.7 kPa (<5 min after the start of the experiment). As heating of the water reservoir was initiated, while other parts of the system remain at ambient temperature (Figure S10a), water partial pressure increased sharply with greater ion currents of mass-charge ratios of 32, 28, and 14 (Figures 7 and S10b), which suggests the increase of N2 and O2 partially due to the release of trapped gas molecules from the swelling resin beads. The CO2 ion current (44) did not increase until the partial pressure of water vapor reached 1.85 kPa, corresponding to 64.8% RH at ambient temperature. This observation is consistent with the breakthrough results that the CO2 uptake capacities in IRA-900-C decrease significantly only when the environmental humidity surpasses a certain threshold level. Although Figure 3a suggests an earlier onset of CO2 desorption from IRA-900-C at RH lower than 64.8%, it took time for the dehydrated IRA-900-C to adsorb water, which is likely the reason for the delayed moment of CO2 desorption. The CO2 signal quickly stabilized within 15 min, suggesting that an equilibrium between gas-phase and adsorbed CO2 was established at the given RH condition. The equilibrium time is of the same order of magnitude as the values reported in prior works that study MSA sorbents in closed systems.24,33 However, there could be a significant amount of CO2 still adsorbed in the sorbent as suggested by Figure 3b despite the quick CO2 desorption. Indeed, Figure S11 shows that more CO2 was desorbed from the resin when the bed was further regenerated under high RH N2 purging after the desorption experiments in a vacuum.

Figure 7.

Mass spectrometer ion current profiles of different species during the CO2 desorption experiments in a vacuum using a packed bed of IRA-900-C.

4. Conclusions

In summary, this work showcases the application of dynamic breakthrough experiments in the systematic investigation of IRA-900-C as an MSA adsorbent for DAC. Cyclic breakthrough experiments show that IRA-900-C possesses a robust CO2 uptake capacity of 1.92 mmol g–1 at 20% RH and 25 °C. More than 91% of OH– sites are utilized for CO2 capture under this condition, which is noticeably superior to the typical amine efficiency of supported amine sorbents for DAC. Breakthrough experiments under different operating conditions are conducted to portray the landscape of CO2 uptake capacities of IRA-900-C as a function of temperatures, RHs, and CO2 partial pressures, confirming the negative impact of RHs on isothermal CO2 uptake capacities. CO2 uptake capacities and kinetics are also affected by the initial hydration degree of IRA-900-C. In addition, the high CO2 sorption capacity of 2.17 mmol g–1 at 1% CO2 concentration, 83% RH, and 25 °C suggests the necessity of maintaining low CO2 partial pressures during sorbent regeneration to achieve a reasonable CO2 working capacity. Breakthrough experiments with different gas velocities and particle sizes of IRA-900-C suggest that the CO2 adsorption in IRA-900-C is controlled by internal mass transfer resistances. Breakthrough experiments also reveal water desorption triggered by CO2 adsorption in the resin, providing valuable insights into water sorption management for DAC based on MSA adsorbents. A theoretical maximum CO2 working capacity of 1.27 mmol g–1 can be achieved with IRA-900-C under a constant purge of humid N2, and the feasibility of CO2 production in vacuum is experimentally verified.

Although we surmise that CO2 diffusion in the polymer bulk phase or (and) the reaction kinetics control the CO2 sorption kinetics in IRA-900-C, the mass transfer behaviors of CO2 and H2O are not fully understood so far with the current sets of breakthrough experiments. Future measurements using ion exchange resins with different texture properties and functionalities should be conducted, and detailed kinetic models considering flow dispersion and adsorption heats should be established to distinguish the contributions of different components of mass transfer resistance with a focus on extracting kinetic information in the polymer bulks and reaction kinetics. In addition, more efforts are necessary for mapping the H2O uptake capacities of MSA sorbents at different CO2 partial pressures, temperatures, and RHs. Last, the long-term stability of IRA-900-C is also a missing piece of the puzzle, which can significantly affect the capital costs of DAC processes based on this material.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Office of Naval Research under Award No. N00014-23-C-1011. This work was performed in part at the Georgia Tech Institute for Electronics and Nanotechnology, a member of the National Nanotechnology Coordinated Infrastructure (NNCI), which is supported by the National Science Foundation (ECCS-2025462).

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssuschemeng.5c00227.

Data processing of breakthrough experiments, additional characterizations of IRA-900 resins, supplementary CO2 breakthrough curves, and CO2 uptake capacities in IRA-900-C under different measurement conditions (PDF)

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Wang E.; Navik R.; Miao Y. H.; Gao Q.; Izikowitz D.; Chen L.; Li J. Reviewing direct air capture startups and emerging technologies. Cell Rep. Phys. Sci. 2024, 5, 101791 10.1016/j.xcrp.2024.101791. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shaw W. J.; Kidder M. K.; Bare S. R.; Delferro M.; Morris J. R.; Toma F. M.; Senanayake S. D.; Autrey T.; Biddinger E. J.; Boettcher S.; Bowden M. E.; Britt P. F.; Brown R. C.; Bullock R. M.; Chen J. G.; Daniel C.; Dorhout P. K.; Efroymson R. A.; Gaffney K. J.; Gagliardi L.; Harper A. S.; Heldebrant D. J.; Luca O. R.; Lyubovsky M.; Male J. L.; Miller D. J.; Prozorov T.; Rallo R.; Rana R.; Rioux R. M.; Sadow A. D.; Schaidle J. A.; Schulte L. A.; Tarpeh W. A.; Vlachos D. G.; Vogt B. D.; Weber R. S.; Yang J. Y.; Arenholz E.; Helms B. A.; Huang W.; Jordahl J. L.; Karakaya C.; Kian K.; Kothandaraman J.; Lercher J.; Liu P.; Malhotra D.; Mueller K. T.; O’Brien C. P.; Palomino R. M.; Qi L.; Rodriguez J. A.; Rousseau R.; Russell J. C.; Sarazen M. L.; Sholl D. S.; Smith E. A.; Stevens M. B.; Surendranath Y.; Tassone C. J.; Tran B.; Tumas W.; Walton K. S. A US perspective on closing the carbon cycle to defossilize difficult-to-electrify segments of our economy. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2024, 8, 376–400. 10.1038/s41570-024-00587-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lackner K. S. Capture of carbon dioxide from ambient air. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2009, 176, 93–106. 10.1140/epjst/e2009-01150-3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Lackner K. S.; Wright A. Moisture Swing Sorbent for Carbon Dioxide Capture from Ambient Air. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 6670–6675. 10.1021/es201180v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X.; Xiao H.; Lackner K. S.; Chen X. Capture CO2 from Ambient Air Using Nanoconfined Ion Hydration. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 4026–4029. 10.1002/anie.201507846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X.; Xiao H.; Chen X.; Lackner K. S. The Effect of Moisture on the Hydrolysis of Basic Salts. Chem. – Eur. J. 2016, 22, 18326–18330. 10.1002/chem.201603701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- He X.; Mei K.; Dao R.; Cai J.; Lin W.; Kong X.; Wang C. Highly efficient and reversible CO2 capture by tunable anion-functionalized macro-porous resins. AIChE J. 2017, 63, 3008–3015. 10.1002/aic.15647. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X.; Xiao H.; Kanamori K.; Yonezu A.; Lackner K. S.; Chen X. Moisture-Driven CO2 Sorbents. Joule 2020, 4, 1823–1837. 10.1016/j.joule.2020.07.005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song J.; Liu J.; Zhao W.; Chen Y.; Xiao H.; Shi X.; Liu Y.; Chen X. Quaternized Chitosan/PVA Aerogels for Reversible CO2 Capture from Ambient Air. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2018, 57, 4941–4948. 10.1021/acs.iecr.8b00064. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hou C.; Wu Y.; Wang T.; Wang X.; Gao X. Preparation of Quaternized Bamboo Cellulose and Its Implication in Direct Air Capture of CO2. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 1745–1752. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.8b02821. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nicotera I.; Policicchio A.; Conte G.; Agostino R. G.; Lufrano E.; Simari C. Quaternary ammonium-functionalized polysulfone sorbent: Toward a selective and reversible trap-release of CO2. J. CO2 Util. 2022, 65, 102259 10.1016/j.jcou.2022.102259. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Biery A. R.; Shokrollahzadeh Behbahani H.; Green M. D.; Knauss D. M. Polydiallylammonium-Polysulfone Multiblock Copolymers for Moisture-Swing Direct Air Capture of Carbon Dioxide. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2024, 6, 2649–2658. 10.1021/acsapm.3c02850. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song J.; Zhu L.; Shi X.; Liu Y.; Xiao H.; Chen X. Moisture Swing Ion-Exchange Resin-PO4 Sorbent for Reversible CO2 Capture from Ambient Air. Energy Fuels 2019, 33, 6562–6567. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.9b00863. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu Y. G.; Booth A.; Hatzell K. B. Confinement Effects on Moisture-Swing Direct Air Capture. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2024, 11, 89–94. 10.1021/acs.estlett.3c00712. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Liu J.; Huang H.; Fang M.; Luo Z. Preparation and kinetics of a heterogeneous sorbent for CO2 capture from the atmosphere. Chem. Eng. J. 2016, 284, 679–686. 10.1016/j.cej.2015.09.009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X.; Li Q.; Wang T.; Lackner K. S. Kinetic analysis of an anion exchange absorbent for CO2 capture from ambient air. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0179828 10.1371/journal.pone.0179828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T.; Wang X.; Hou C.; Liu J. Quaternary functionalized mesoporous adsorbents for ultra-high kinetics of CO2 capture from air. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 21429 10.1038/s41598-020-77477-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong H.; Wang T.; Wang X.; Liu F.; Hou C.; Wang Z.; Liu W.; Fu L.; Gao X. Humidity sensitivity reducing of moisture swing adsorbents by hydrophobic carrier doping for CO2 direct air capture. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 466, 143343 10.1016/j.cej.2023.143343. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Armstrong M.; Shi X.; Shan B.; Lackner K.; Mu B. Rapid CO2 capture from ambient air by sorbent-containing porous electrospun fibers made with the solvothermal polymer additive removal technique. AIChE J. 2019, 65, 214–220. 10.1002/aic.16418. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Chen Y.; Xu W.; Lindbråthen A.; Cheng X.; Chen X.; Zhu L.; Deng L. Development of high capacity moisture-swing DAC sorbent for direct air capture of CO2. Sep. Purif. Technol. 2023, 324, 124489 10.1016/j.seppur.2023.124489. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins N. S.; Rajendran A.; Farooq S. Dynamic column breakthrough experiments for measurement of adsorption equilibrium and kinetics. Adsorption 2021, 27, 397–422. 10.1007/s10450-020-00269-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Parzuchowski P. G.; Swiderska A.; Roguszewska M.; Rolińska K.; Wołosz D. Moisture- and Temperature-Responsive Polyglycerol-Based Carbon Dioxide Sorbents—The Insight into the Absorption Mechanism for the Hydrophilic Polymer. Energy Fuels 2020, 34, 12822–12832. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.0c02174. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.; Zhu L.; Wang P.; Zhao W.; Chen X. CO2 removal from natural gas by moisture swing adsorption. Chem. Eng. Res. Des. 2021, 176, 162–168. 10.1016/j.cherd.2021.09.033. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang X.; Song J.; Chen Y.; Xiao H.; Shi X.; Liu Y.; Zhu L.; He Y.-L.; Chen X. CO2 Absorption over Ion Exchange Resins: The Effect of Amine Functional Groups and Microporous Structures. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2020, 59, 16507–16515. 10.1021/acs.iecr.0c03189. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hegarty J.; Shindel B.; Sukhareva D.; Barsoum M. L.; Farha O. K.; Dravid V. Expanding the Library of Ions for Moisture-Swing Carbon Capture. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2023, 57, 21080–21091. 10.1021/acs.est.3c02543. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Pérez E. S.; Murdock C. R.; Didas S. A.; Jones C. W. Direct Capture of CO2 from Ambient Air. Chem. Rev. 2016, 116, 11840–11876. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.6b00173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anyanwu J.-T.; Wang Y.; Yang R. T. CO2 Capture (Including Direct Air Capture) and Natural Gas Desulfurization of Amine-Grafted Hierarchical Bimodal Silica. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 427, 131561 10.1016/j.cej.2021.131561. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xie R. Y.; Chen S.; Yong J. Y.; Zhang X. J.; Jiang L. Moisture swing adsorption for direct air capture: Establishment of thermodynamic cycle. Chem. Eng. Sci. 2024, 287, 119809 10.1016/j.ces.2024.119809. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shi X.; Xiao H.; Liao X.; Armstrong M.; Chen X.; Lackner K. S. Humidity effect on ion behaviors of moisture-driven CO2 sorbents. J. Chem. Phys. 2018, 149, 164708 10.1063/1.5027105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao H.; Shi X.; Zhang Y.; Liao X.; Hao F.; Lackner K. S.; Chen X. The catalytic effect of H2O on the hydrolysis of CO32– in hydrated clusters and its implication in the humidity driven CO2 air capture. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2017, 19, 27435–27441. 10.1039/C7CP04218C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vallace A.; Ren Y.; Jones C. W.; Lively R. P. Kinetic model describing self-limiting CO2 diffusion in supported amine adsorbents. Chem. Eng. J. 2023, 472, 144838 10.1016/j.cej.2023.144838. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kaneko Y.; Lackner K. S. Kinetic model for moisture-controlled CO2 sorption. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2022, 24, 21061–21077. 10.1039/D2CP02440C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hou C.; Kumar D. R.; Jin Y.; Wu Y.; Lee J. J.; Jones C. W.; Wang T. Porosity and hydrophilicity modulated quaternary ammonium-based sorbents for CO2 capture. Chem. Eng. J. 2021, 413, 127532 10.1016/j.cej.2020.127532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brandani S.; Mangano E. The zero length column technique to measure adsorption equilibrium and kinetics: lessons learnt from 30 years of experience. Adsorption 2021, 27, 319–351. 10.1007/s10450-020-00273-w. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Y. Identification of mass transfer resistances in microporous materials using frequency response methods. Adsorption 2021, 27, 369–395. 10.1007/s10450-021-00305-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Holmes H. E.; Realff M. J.; Lively R. P. Water management and heat integration in direct air capture systems. Nat. Chem. Eng. 2024, 1, 208–215. 10.1038/s44286-024-00032-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Song M.; Rim G.; Kong F.; Priyadarshini P.; Rosu C.; Lively R. P.; Jones C. W. Cold-Temperature Capture of Carbon Dioxide with Water Coproduction from Air Using Commercial Zeolites. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2022, 61, 13624–13634. 10.1021/acs.iecr.2c02041. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fu D.; Park Y.; Davis M. E. Confinement effects facilitate low-concentration carbon dioxide capture with zeolites. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2022, 119, e2211544119 10.1073/pnas.2211544119. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joos L.; Swisher J. A.; Smit B. Molecular Simulation Study of the Competitive Adsorption of H2O and CO2 in Zeolite 13X. Langmuir 2013, 29, 15936–15942. 10.1021/la403824g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magnin Y.; Dirand E.; Orsikowsky A.; Plainchault M.; Pugnet V.; Cordier P.; Llewellyn P. L. A Step in Carbon Capture from Wet Gases: Understanding the Effect of Water on CO2 Adsorption and Diffusion in UiO-66. J. Phys. Chem. C 2022, 126, 3211–3220. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.1c09914. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ho C.-H.; Paesani F. Elucidating the Competitive Adsorption of H2O and CO2 in CALF-20: New Insights for Enhanced Carbon Capture Metal–Organic Frameworks. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2023, 15, 48287–48295. 10.1021/acsami.3c11092. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hastings J.; Lassitter T.; Fylstra N.; Shimizu G. K. H.; Glover T. G. Steam Isotherms, CO2/H2O Mixed-Gas Isotherms, and Single-Component CO2 and H2O Diffusion Rates in CALF-20. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 11544–11551. 10.1021/acs.iecr.4c00373. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen T. T. T.; Balasubramaniam B. M.; Fylstra N.; Huynh R. P. S.; Shimizu G. K. H.; Rajendran A. Competitive CO2/H2O Adsorption on CALF-20. Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 2024, 63, 3265–3281. 10.1021/acs.iecr.3c04266. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.