Abstract

Reported herein is the use of a recyclable coupling agent, 2,2’-dipyridyldithiocarbonate (DPDTC), that generates isolable thioesters in a plug flow reactor (PFR). If not isolated, thioesters can be reintroduced directly into the PFR, along with amines, to generate amides in a “flow-to-flow” sense. Both electron-rich and -poor aromatic acids, as well as sterically hindered aliphatic acids, are efficiently coupled with a variety of amines, including the formation of Weinreb amides and peptides, in high yields.

Keywords: flow chemistry, telescoping, recyclable green solvent, amide formation, 1-pot sequence

Short abstract

Tandem plug flow, realized from readily available components, produces amides in minutes using a recyclable coupling reagent and sustainable solvent.

Introduction

Continuous flow technology has been increasingly utilized in green chemistry1−4 and especially in the production5−11 of pharmaceuticals. In 2019, the International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry (IUPAC) ranked flow chemistry as one of the top 10 innovations in the area of sustainability.12 Increased mixing, decreased reaction times, improved worker safety, and continuous output of materials are but a few benefits of flow chemistry over traditional batch methods.13 An additional benefit is the ability to run multistep or telescoped reactions through tandem flow reactors.5,14−16 This allows reactants for subsequent steps to be introduced directly into the reactor at the appropriate time without operator interventions, a feature which is commonly applied to the total synthesis of active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs)6,17−19 and other pharmaceutically relevant small molecules.20−22 This leads to increases in reproducibility, which also adds to the scalability of the overall process.23

Beyond flow technology utilized in both academic and industrial laboratories, extension to “flow-to-flow” reactors offer even greener options by reducing the number of separate steps, ultimately creating a single setup for a streamlined synthesis of products of interest, e.g., to the fine chemicals industry. A PFR reactor, therefore, was developed that would be readily accessible to most laboratories.24

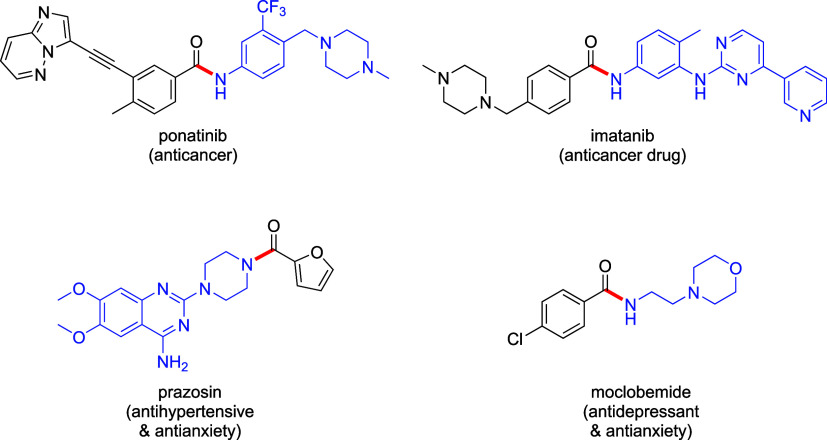

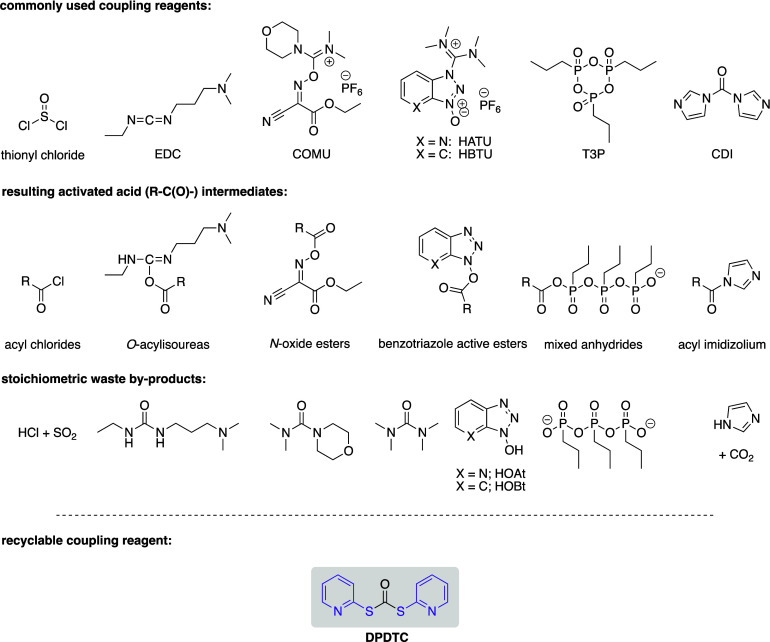

Among the many reactions that benefit from translation into flow,15,25 amide coupling stands out given that it is among the most utilized reaction in pharmaceutical26 and fine chemical production.27,28 Amide bonds are commonly seen in anticancer drugs such as ponatinib29 and imatinib,29 as well as antihypertensive and antianxiety drugs, like prazosin30 and moclobemide,31 respectively (Scheme 1). There are several reagents32 commonly used in organic solvents that activate a carboxylic acid, including those that form acyl chlorides, mixed anhydrides, acyl imidizoliums, and O-acylisoureas, among others (Scheme 2). According to the green reagent guide for amidations,33 there are only a few coupling reagents that are listed as being “green”, among which several are problematic or even hazardous. All produce stoichiometric amounts of organic waste and are usually employed in egregious organic solvents (e.g., DCM, DMF, etc.). For example, EDC, listed as a green reagent, generates stoichiometric urea byproducts, which can be easily separated from the reaction via an aqueous workup. However, this generated waste is difficult to treat.34 Others from the uronium group, such as HATU and HBTU, are based on the HOBt core, which can be explosive.35 Nonetheless, these are still utilized due to their relatively mild reaction conditions and excellent coupling capabilities, notwithstanding their low atom economy.36−39 Meanwhile, reagents with high atom economy, such as CDI, produce less reactive acyl imidazolium intermediates, thus affording less efficient coupling partners. Finally, reagents such as thionyl chloride are difficult to work with due to water sensitivity, although the highly reactive acyl chlorides formed show good atom economy. These limitations led us to pursue an alternative green coupling reagent for use under flow conditions, as described herein.

Scheme 1. Representative Amide-Containing APIs.

Scheme 2. Commonly Used Reagents for Amide Couplings, Their Associated Activated Intermediates, and Their Byproducts.

Previously, we disclosed use of 2,2′-dipyridyldithiocarbonate (DPDTC) as a coupling reagent in the course of a 1-pot, 2-step protocol that results in the required amide/peptide bond.38 This reagent efficiently couples carboxylic acids and amines (Scheme 3), and although two equivalents of 2-mercaptopyridine are generated as byproduct, it can easily be separated and recycled, being used to remake the coupling reagent (DPDTC) itself.40 Thus, under these conditions (including the recycling of 2-mercaptopyridine), one equivalent of CO2 is the only byproduct. While this batch methodology uses near neat reaction conditions at moderate temperatures, reaction times can be long (>8 h). Use of DPDTC in a PFR, however, leads to amides via the intermediate thioesters in recyclable 2-MeTHF under relatively mild conditions in less than 1 h.

Scheme 3. Amide Coupling of Carboxylic Acids with Amines Using DPDTC under Batch vs. Flow Modes.

Results and Discussion

Batch-to-Flow Methodology

Use of DPDTC in batch mode as a green amide coupling agent involved longer reaction times; i.e., up to 24 h. Although lower reaction temperatures and concentrated reaction mixtures contributed to this, transitioning to a continuous plug flow setup proved challenging, even with the improved mixing that plug flow typically provides.41 Improved mixing is a general benefit attributed to flow; however, it generally arises from high flow rates and the associated increases in Reynold’s numbers, implying enhanced mixing. The Reynold’s number itself is a unitless measure of the mass transfer in a system and can be used to predict the type of mixing that will be seen. Hence, it was crucial to find a method that shortened reaction times such that the flow rates were relatively high in our 2.0 mL coil reactor.

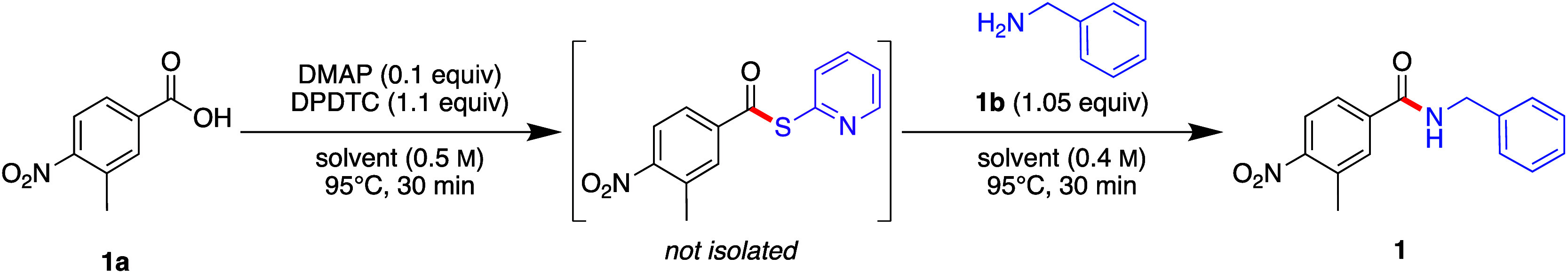

Initial experiments focused on temperature, looking to increase reaction rates; hence, an initial temperature of 95 °C was selected. This is above the boiling point of 2-MeTHF (i.e., 78 °C), although it is considerably safer when done in continuous flow systems.41 The reaction between 3-methyl-4-nitrobenzoic acid (1a) and benzylamine (1b) was run in a 2-step, 1-pot manner with minimal head space in batch to simulate flow conditions (Table 1). Each step was allowed 30 min to ensure sufficient mixing in a 2.0 mL PFR. This initial reaction led to only a 35% yield with no thioester remaining, indicating the need for screening additives to enhance the rate of reaction to the thioester intermediate. Among several additives, only DMAP (10 mol %) afforded the product amide in near quantitative yield (entry 5), while alternatives such as 4-methoxypyridine and 4-pyrrolidinylpyridine were not as efficient even in stoichiometric amounts (see SI, Section 3d). Lowering the amount of DMAP under these conditions led to a decrease in the yield (entry 6).

Table 1. Screening Additives Leading to Product 1 in Batch Mode.

| entry | additive | mol % | NMR yield 1 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | none | n/a | 35 |

| 2 | 2,6-lutidine | 10 | 35 |

| 3 | DBU | 10 | 28 |

| 4 | N-methylmorpholine | 10 | 32 |

| 5 | DMAP | 10 | 98 (quant)a |

| 6 | DMAP | 5 | 42 |

| 7 | DABCO | 10 | 38 |

| 8 | NEt3 | 10 | 35 |

| 9 | 4-methoxypyridine | 10 | 46 |

| 10 | 4-pyrrolidinylpyridine | 10 | 86 (75)a |

Isolated yields in parentheses. NMR yields using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as internal standard.

The amounts of both DPDTC and amine needed were then optimized (see SI, Sections 3e and 3h), leading to the finding that 1.05 equiv are optimal for both. Lastly, various solvents were screened (Table 2) based on GSK’s solvent selection guide.42,43 While alcohols would be preferred over most other types of solvents, their use could potentially lead to ester formation following the in situ generated thioester.44 Nonetheless, while tertiary alcohol, t-BuOH, showed promise leading to 79% yield of the amide (entry 6), it showed reduced solubilizing properties toward carboxylic acid 1a. Since the reaction had already been run in batch mode at 0.5 M, stock solutions for use in flow would need to be more concentrated. Therefore, MIBK, while a good solvent for use in batch (entry 1), would be inappropriate in flow; the same is true for CPME (entry 3). The only solvents that could work to solubilize the carboxylic acid above 0.5 M would be THF or 2-MeTHF. Since the amines were expected to be soluble in the chosen solvent or water, 2-MeTHF was selected as it could be recovered and reused in the presence of an aqueous reaction medium.

Table 2. Screening of Solvents for Amide Couplings with DPDTC and Solubilities of 1aa.

| entry | solvent | NMR yield 1 (%) | solubility of acid in solvent (M) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | MIBK | 100 | 0.1 |

| 2 | MEK | 46 | 0.2 |

| 3 | CPME | 95 | 0.1 |

| 4 | THF | 97 | 1 |

| 5 | iPrOAc | 76 | 0.1 |

| 6 | tBuOH | 79 | 0.5 |

| 7 | EtOAc | 98 | 0.1 |

| 8 | 2-MeTHF | 98 | 0.75 |

| 9 | toluene | 100 | not soluble |

| 10 | MTBE | 100 | 0.1 |

NMR yields using 1,3,5-trimethoxybenzene as internal standard.

Tandem Reactor Setup

In this system (see SI, Section 2Figure S1) the outlet of the first coil reactor serves as the inlet to the second coil reactor. Given the previous use of a 2.0 mL (0.03 in. ID) reactor coil, this was chosen, leading to sufficient mixing and a 66.67 μL/min total flow rate out of coil 1. The second coil, therefore, would need to change size based on the flow rate of the amine entering the reactor at the third T-joint. To minimize variation between reactors, 2.5 and 4.0 mL reactor coils were chosen to allow for dilution of the amine as needed in the second coil reactor. Table S2 shows several options where the acid was solubilized at 0.83 or 0.31 M, while the amine ranged from 2.10 to 0.26 M. To minimize variations in the setup, only substrates that would not dissolve at concentrations above 0.83 M were diluted (to 0.31 M) to create an overall reaction concentration of 0.25 M in the 2.0 mL coil for the thioester formation step.

Finally, a system was constructed akin to that previously used by our group (see SI, Section 2Figure S2).24,45Figure 1 represents a sample schematic, where a peristaltic pump delivers the carboxylic acid through a T-joint that meets with the first coil reactor (2.0 mL). DPDTC and DMAP are delivered in a perpendicular fashion via syringe pump and are joined via a short pass (1 in. × 0.03 in. ID). Both solutions are 2.63 and 0.25 M, delivering exactly 1.05 and 0.1 equiv, respectively. It was crucial to introduce DPDTC prior to DMAP to avoid precipitation of salts from the acid–base interactions. Thus, changing the reactor coils and concentrations of the carboxylic acid and amine did not affect either DPDTC or DMAP, both being delivered from the same syringe pump. The second syringe pump was used to deliver the amine, based on the concentration and flow rate in Table 3, via a T-joint between the two reactor coils. A second peristaltic pump was configured as a back pressure regulator, with the BPR set to 4 bar.

Figure 1.

Schematic for flow-to-flow reactor.

Table 3. Comparisons with Literature Methods.

Scope: Amide Formation

The first successful coupling in flow using the tandem system gave amide-containing product 1 in 97% isolated yield, which matched the yield obtained in batch (98%; Scheme 4). A variety of aromatic carboxylic acids were then successfully coupled, giving products 2, 3, 9, and 10 in quantitative yields. Heterocycles such as the pyrrole-containing product 7 and isoxazole 12 were obtained in moderate to high yields. An aliphatic carboxylic acid led to dipeptide 4 as a mixture (96:4) of diastereomers, formed from Boc-L-Tle-OH and L-Phe-OMe using a 1:1 2-MeTHF:2 wt % Savie/H2O mixture in a combined yield of 76%. The dr was confirmed by an HPLC analysis run against pure standards of each diastereomer made using HATU. Other aliphatic carboxylic acids gave products 5 and 11. A Weinreb amide 12 could also be prepared in flow using the N,O-dimethyhydroxylamine hydrochloride salt, along with 1.05 equiv of NaHCO3, both being introduced into the reactor in water.

Scheme 4. Substrate Scope: Amide Couplings under Flow Conditions.

Coil 1 was 1.44 mL and coil 2 was 2.0 mL.

2nd Step was done with amine·HCl salt (1.05 equiv) and NaHCO3 (1.05 equiv).

2nd Step stock solutions dissolved in 2 wt % Savie/H2O.

1st Step was 0.5 M and second step was 0.25 M.

1st Step was 0.25 M and second step was 0.2 M.

10% DMSO was used to solubilize the acid stock solution.

The remaining mass is thioester.

2nd Step stock solutions dissolved in H2O. Isolated yields (yields from batch mode in parentheses).

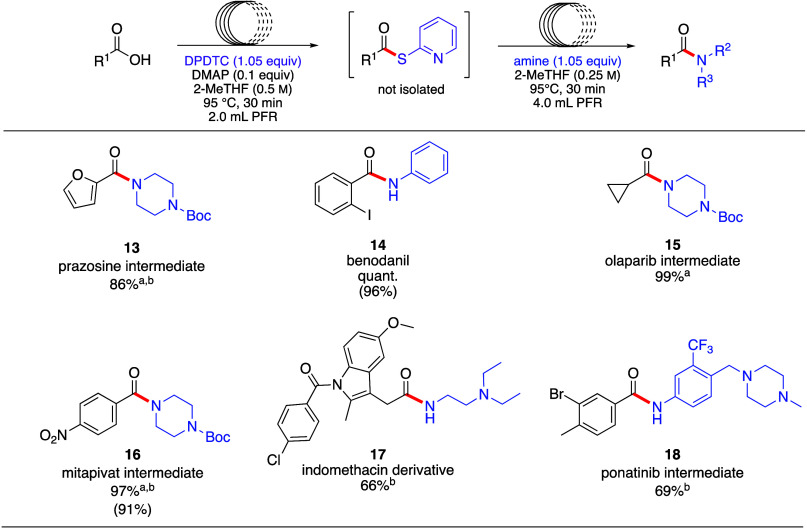

Drug Intermediates, Targets, and Derivatives

This technology was also applied to the syntheses of various drug intermediates and targets, where the amide-forming step was conducted in a 4.0 mL reactor rather than a 2.5 mL reactor due to the necessity of diluting the amine stock solutions (Scheme 5). The intermediates containing the N-Boc-protected piperazine 13, 15, and 16, toward the drugs prazosin, olaparib, and mitapivat, respectively, were prepared in high yields. Amide formation occurred in a 1:1 mix of 2-MeTHF and H2O, where the amine was solubilized in water while preparing the stock solution which also increases the nucleophilicity of the amine.46 Amide formation of a derivative of the nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug indomethacin (product 17) took place in moderate yield under these reaction conditions, the remaining mass composed of the thioester intermediate. Intermediate 18, useful en route to the anticancer agent ponatinib, was also prepared in moderate yield (69%), given the dilution to 0.125 M in the second step.

Scheme 5. Substrate Scope: Amide Couplings Towards Drug Targets and Derivatives Prepared under Flow Conditions.

Amine was dissolved in water.

1st Step was 0.25 M and second step was 0.125 M. Isolated yields (yields from batch mode in parentheses).

Direct Comparisons toward Other Amide Coupling Systems in Flow

Recent reports highlight more attention to environmentally friendly amide couplings,47,48 such as use of EDC·HCl in a mechanochemical screw reactor,49 CS2/Al2O350 or boronic acid-supported51 packed-bed reactors, and a Ir/Co cocatalytic photocatalysis system52 in plug flow. While these are representative of inherently greener processes using flow technology, they require either specialized equipment or catalysts and all generate stoichiometric amounts of waste.

Direct comparisons of results using flow systems were made, the results of which are shown in Table 3. Products 9 and 10 were formed in quantitative yields using DPDTC in recyclable 2-MeTHF. Product 9 was previously reported using a photocatalyst under blue LED light in DCM, giving the product in 90% yield in 40 min. Amide 11 was reportedly formed in up to 35% conversion (vs. 43% yield) using a packed-bed reactor containing a boronic acid-supported catalyst using toluene at 110 °C. While product 13 can be made under neat conditions within 1–2 min in a mechanochemical screw reactor,52 use of EDC·HCl leads to a stoichiometric amount of urea.53 Amide 13 was previously reported by us (77% yield) using DPDTC in batch mode, where the amide forming step occurred in 2 wt % TPGS-750-M/H2O (0.5 M); when translated to flow, the amide was prepared in 86% yield in 60 min compared to 12–18 h.

Formation and Isolation of Thioesters

In addition to the generation of amides via a tandem reactor setup, the potential to form and isolate the thioester intermediates can also be attractive. Historically, thioesters are useful intermediates toward a variety of alternative bond constructions, such as in Fukuyama54 and Liebskind–Srogl55,56 couplings. Thioesters derived from DPDTC have been shown to be amenable to further conversion to other valuable targets such as esters and thioesters,44 as well as shelf-stable intermediates en route to aldehydes and alcohols via reduction with NaBH4 in 95% EtOH.57 As illustrated in Scheme 6, thioesters can be readily formed and isolated within 30 min in flow. Both aromatic (19 and 23) and aliphatic (20–22) acids afforded their corresponding 2-pyridyl thioesters (Scheme 6).

Scheme 6. Substrate Scope: Formation and Isolation of Thioester Intermediates Using Flow Technology.

Renewable, Recoverable, and Recyclable

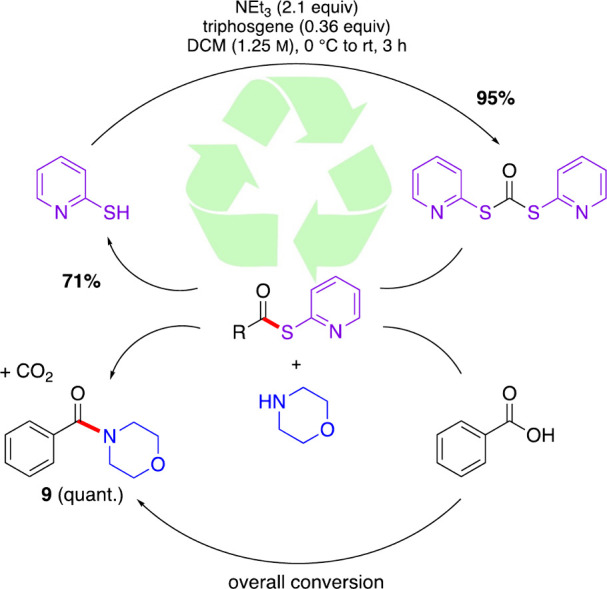

According to the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry(58) a renewable feedstock is always preferred over one that cannot be replaced. Since 2-MeTHF is bioderived from sugars via hydrogenation of furfural,59 it was chosen as solvent from a sustainability standpoint. Also noted (vide supra) is the stoichiometric amount of waste created from most alternative coupling agents, while DPDTC leads to recoverable and recyclable 2-mercaptopyridine. Scheme 7 depicts the life cycle of DPDTC in the context of amide coupling, using amide product 9 as an example. Recovery of the 2-mercaptopyridine (71%) allowed for its reuse to make additional DPDTC (95% yield, and in high purity). 2-MeTHF was also recoverable and reusable. Product 6 was collected (Scheme 8), after which the solvent was distilled from the crude reaction mixture (78% recovery). The solvent was then used in making stock solutions toward product 5. After this, the solvent was again distilled from the crude reaction mixture and used in making the stock solutions toward amide product 7.

Scheme 7. Recycling of 2-Mercaptopyridine Generated Using DPDTC for Amide Formation.

Scheme 8. Recycling of 2-MeTHF.

Multistep Flow-to-Batch-to-Flow-to-Batch Synthesis

To demonstrate the potential applicability of this methodology toward syntheses of APIs, a multistep synthesis was conducted alternating between flow and batch (Scheme 9). Starting with 2-bromo-1-fluoro-4-nitrobenzene and 4-methoxyphenol, an SNAr reaction was initially run using flow conditions, as recently described.60 After 3 h of collection followed by removal of the 2-MeTHF, 4 wt % Savie/H2O was added to the reaction mixture. The crude material was then subjected to batch reduction using carbonyl iron powder (CIP).61 Upon completion, the reaction was filtered through a Celite plug and extracted with EtOAc after which the solvent was evaporated under reduced pressure (which is recoverable). The mixture containing the amine was used in flow for an amide coupling to 24, with the acid being converted initially to the corresponding thioester with DPDTC. Lastly, a Suzuki–Miyaura coupling with 24 led to final product 25, purified via column chromatography, in 84% yield over 5 steps.

Scheme 9. Multistep Synthesis Alternating between Flow and Batch Mode.

Summary and Conclusions

A new technology has been developed that offers a route to amide formation that relies on a recoverable and recyclable green solvent, 2-MeTHF, utilizing a readily accessible plug flow reactor. The process involves initial formation of a thioester derived from a commercially available precursor (DPDTC), which leads to a recyclable byproduct, 2-mercaptopyridine. By combining technologies in a “flow-to-flow” sense, initially formed thioesters, which are themselves isolable and storable, can be converted to amides in ≤1 h. Several aspects of this technology are documented, including (1) tolerance to many functional groups, (2) favorable comparisons to existing literature methodologies, and (3) application to a multistep sequence documenting that products of considerable complexity can be obtained using a combination of flow and batch approaches, all under environmentally respectful conditions.

Experimental Section

General Procedure for Amide Couplings in Batch Mode

To a 1-dram vial equipped with a PTFE stir bar was added carboxylic acid (1 equiv, 0.5 mmol), N,N-dimethylpyridin-4-amine (DMAP) (6.1 mg, 0.1 equiv, 0.05 mmol), and DPDTC (130. mg, 1.05 equiv, 0.525 mmol). 2-MeTHF (1.0 mL, 0.5 M) was added, and the vial was capped and sealed with Teflon tape. The reaction vial was placed into an aluminum heating block which was preheated to 95 °C, and the reaction was stirred vigorously for 30 min. The reaction was taken off the aluminum block and allowed to cool to rt briefly. Once cooled, the cap was removed, and amine (1.05 equiv, 0.525 mmol) and 2-MeTHF (0.25 mL, 0.4 M) were quickly added. The vial was capped, taped, and stirred for another 30 min. The resulting mixture was allowed to cool to rt before being washed 3 times with saturated NaHSO3 (sodium bisulfite) as a mild reductant to reduce 2,2′-dipyridyldisulfide to 2-mercaptopyridine. Then the reaction was washed with 1 M NaOH. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and purified by column chromatography as needed.

Synthesis of 2,2-Dipyridyldithiocarbonate (DPDTC)

2,2-Dipyridyldithiocarbonate (DPDTC) was synthesized as previously reported.40 The reaction was run on a 0.47 mol scale (58 g), and the concentration was increased to 1.25 M. After slow addition of solid triphosgene in small portions over 1 h under a positive argon pressure, the reaction was allowed to warm to rt while stirring for 3 h. At this point, the reaction was complete by TLC and quenched with H2O. The crude product was washed with 1:1 MTBE:hexanes (rather than Et2O:pentane, as in ref (40)) giving DPDTC as a yellow-orange solid 96% yield (56 g). The purity was confirmed by NMR showing no remaining 2-mercaptopyridine or 2,2-dipyridyldisulfide peaks.

General Procedure for Amide Couplings in Flow

Peristaltic pump 1 delivered a solution of carboxylic acid (1 equiv) in 2-MeTHF through a T-assembly (High Pressure PEEK, 0.02 in. ID) with syringe pump 1 delivering a solution of DPDTC (1.05 equiv) in 2-MeTHF perpendicular to the peristaltic pump 1. This led into a short pass of tubing (0.03 in. ID × 1 in. length) connected to a second T-assembly (High Pressure PEEK, 0.02 in. ID) with syringe pump 1 delivering a solution of DMAP (0.1 equiv) in 2-MeTHF perpendicular to the short pass. This led directly into the 2 mL reactor (0.03 in. ID) which met a third T-assembly (High Pressure PEEK, 0.02′ in. ID) with syringe pump 2 delivering a solution of amine (1.05 equiv) in 2-MeTHF perpendicular to the 2 mL reactor coil. This led directly into the second reactor coil 2.5 or 4.0 mL (0.03 in. ID) which led through a short pass to peristaltic pump 2 operating as a back-pressure regulator (4 bar) before collection.

Prior to running the reaction, the appropriate reactors and short passes with T-mixers were connected and flushed with 2-MeTHF. The SS syringes were filled with the requisite solutions and connected as described above. The stock solutions and concentrations of each step were determined based on solubility of substrates (see Table S2). The peristaltic pump and syringe pumps were set to the correct flow rate, as outlined in each diagram below. Once the pumps began flowing and the back pressure regulator read 4 bar, the system was allowed to come to equilibrium by priming for two residence times (1 h each). Then a minimum of five fractions were collected in 2-dram vials for either 15 or 30 min (to give 0.25 or 0.5 mmol aliquots). The resulting mixture was allowed to cool to rt before being washed 3 times with saturated NaHSO3 (sodium bisulfite) as a mild reductant to reduce 2,2′-dipyridyldisulfide to 2-mercaptopyridine. Then the reaction was washed with 1 M NaOH. The organic layer was dried over anhydrous MgSO4, and the solvent was removed under reduced pressure and purified by column chromatography as needed.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the funding made available by PHT International towards the purchase of the flow equipment shown in Figure S2. We also acknowledge VapourTec for providing additional tubing for the SF-10 peristaltic pumps.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- DPDTC

dipyridyldithiocarbonate

- PFR

plug flow reactor

- IUPAC

International Union of Pure and Applied Chemistry

- API

active pharmaceutical ingredients

- DCM

dichloromethane

- DMF

N,N-dimethylformamide

- HATU

1-[bis(dimethylamino)methylene]-1H-1,2,3-triazolo[4,5-b]pyridinium 3-oxid hexafluorophosphate

- HBTU

[benzotriazol-1-yloxy(dimethylamino)methylidene]-dimethylazanium hexafluorophosphate

- HOBt

1H-1,2,3-benzotriazol-1-ol

- EDC

3-{[(ethylimino)methylidene]amino}-N,N-dimethylpropan-1-amine

- COMU

(1-cyano-2-ethoxy-2-oxoethylidenaminooxy)dimethylamino-morpholino-carbenium hexafluorophosphate

- T3P

2,4,6-tripropyl-1,3,5,2λ5,4λ5,6λ5-trioxatriphosphinane-2,4,6-trione

- CDI

1,1′-carbonyldiimidazole

- DMAP

N,N-dimethylaminopyridine

- DBU

2,3,4,6,7,8,9,10-octahydropyrimido[1,2-a]azepine

- DABCO

1,4-diazabicyclo[2.2.2]octane

- GSK

GlaxoSmithKline

- MIBK

methyl isobutyl ketone

- CPME

cyclopentyl methyl ether

- THF

tetrahydrofuran

- 2-MeTHF

2-methyltetrahydrofuran

- MEK

methyl ethyl ketone

- iPrOAc

isopropyl acetate

- EtOAc

ethyl acetate

- MTBE

methyl t-butyl ether

- BPR

back-pressure regulator

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acssuschemeng.5c00914.

Experimental procedures, optimization details, and analytical data of isolated materials (NMR, ICPMS, HRMS) (PDF)

Author Contributions

J.M.S. planned and performed the experiments. E.O.N. and J.L. helped conduct experiments. M.J.W., K.F., and B.H.L. helped supervise, consult on the work, and edit the manuscript. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

Financial assistance provided by PHT International and the NSF (CHE 2152566) is warmly acknowledged with thanks. E. Oceguera Nava is supported by the National Science Foundation, California, LSAMP Bridge to Doctorate Fellowship under Grant No. EES- 2404971.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Alfano A. I.; Lange H.; Brindisi M. Amide Bonds Meet Flow Chemistry: A Journey into Methodologies and Sustainable Evolution. ChemSusChem 2022, 15, e202200301. 10.1002/cssc.202200301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrucci C.; Strappaveccia G.; Giacalone F.; Gruttadauria M.; Pizzo F.; Vaccaro L. An E-Factor Minimized Protocol for a Sustainable and Efficient Heck Reaction in Flow. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2014, 2, 2813–2819. 10.1021/sc500584y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Newman S. G.; Jensen K. F. The Role of Flow in Green Chemistry and Engineering. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 1456–1472. 10.1039/c3gc40374b. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dallinger D.; Kappe C. O. Why Flow Means Green - Evaluating the Merits of Continuous Processing in the Context of Sustainability. Curr. Opin. Green Sustainable Chem. 2017, 7, 6–12. 10.1016/j.cogsc.2017.06.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bana P.; Örkényi R.; Lövei K.; Lakó Á.; Túrós G. I.; Éles J.; Faigl F.; Greiner I. The Route from Problem to Solution in Multistep Continuous Flow Synthesis of Pharmaceutical Compounds. Bioorg. Med. Chem. 2017, 25, 6180–6189. 10.1016/j.bmc.2016.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bogdan A. R.; Poe S. L.; Kubis D. C.; Broadwater S. J.; McQuade D. T. The Continuous-Flow Synthesis of Ibuprofen. Angew. Chem. 2009, 121, 8699–8702. 10.1002/ange.200903055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isidro-Llobet A.; Kenworthy M. N.; Mukherjee S.; Kopach M. E.; Wegner K.; Gallou F.; Smith A. G.; Roschangar F. Sustainability Challenges in Peptide Synthesis and Purification: From R&D to Production. J. Org. Chem. 2019, 84, 4615–4628. 10.1021/acs.joc.8b03001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porta R.; Benaglia M.; Puglisi A. Flow Chemistry: Recent Developments in the Synthesis of Pharmaceutical Products. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2016, 20, 2–25. 10.1021/acs.oprd.5b00325. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gutmann B.; Cantillo D.; Kappe C. O. Continuous-Flow Technology—A Tool for the Safe Manufacturing of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 6688–6728. 10.1002/anie.201409318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malet-Sanz L.; Susanne F. Continuous Flow Synthesis. A Pharma Perspective. J. Med. Chem. 2012, 55, 4062–4098. 10.1021/jm2006029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Poechlauer P.; Manley J.; Broxterman R.; Gregertsen B.; Ridemark M. Continuous Processing in the Manufacture of Active Pharmaceutical Ingredients and Finished Dosage Forms: An Industry Perspective. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2012, 16, 1586–1590. 10.1021/op300159y. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gomollón-Bel F. Ten Chemical Innovations That Will Change Our World: IUPAC Identifies Emerging Technologies in Chemistry with Potential to Make Our Planet More Sustainable. Chem. Int. 2019, 41, 12–17. 10.1515/ci-2019-0203. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guidi M.; Seeberger P. H.; Gilmore K. How to Approach Flow Chemistry. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 8910–8932. 10.1039/C9CS00832B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lignos I.; Mo Y.; Carayannopoulos L.; Ginterseder M.; Bawendi M. G.; Jensen K. F. A High-Temperature Continuous Stirred-Tank Reactor Cascade for the Multistep Synthesis of InP/ZnS Quantum Dots. React. Chem. Eng. 2021, 6, 459–464. 10.1039/D0RE00454E. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- McQuade D. T.; Seeberger P. H. Applying Flow Chemistry: Methods, Materials, and Multistep Synthesis. J. Org. Chem. 2013, 78, 6384–6389. 10.1021/jo400583m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wegner J.; Ceylan S.; Kirschning A. Flow Chemistry - A Key Enabling Technology for (Multistep) Organic Synthesis. Adv. Synth. Catal. 2012, 354, 17–57. 10.1002/adsc.201100584. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Snead D. R.; Jamison T. F. A Three-Minute Synthesis and Purification of Ibuprofen: Pushing the Limits of Continuous-Flow Processing. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54, 983–987. 10.1002/anie.201409093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fu W. C.; Jamison T. F. Modular Continuous Flow Synthesis of Imatinib and Analogues. Org. Lett. 2019, 21, 6112–6116. 10.1021/acs.orglett.9b02259. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang J. C.; Niu D.; Karsten B. P.; Lima F.; Buchwald S. L. Use of a “Catalytic” Cosolvent, N,N-Dimethyl Octanamide, Allows the Flow Synthesis of Imatinib with No Solvent Switch. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55, 2531–2535. 10.1002/anie.201509922. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiao J.; Nie W.; Yu T.; Yang F.; Zhang Q.; Aihemaiti F.; Yang T.; Liu X.; Wang J.; Li P. Multi-Step Continuous-Flow Organic Synthesis: Opportunities and Challenges. Chem. Eur. J. 2021, 27, 4817–4838. 10.1002/chem.202004477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herath A.; Molteni V.; Pan S.; Loren J. Generation and Cross-Coupling of Organozinc Reagents in Flow. Org. Lett. 2018, 20, 7429–7432. 10.1021/acs.orglett.8b03156. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton J.; Raston C. L. Multi-Step Continuous-Flow Synthesis. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2017, 46, 1250–1271. 10.1039/C6CS00830E. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lovato K.; Fier P. S.; Maloney K. M. The Application of Modern Reactions in Large-Scale Synthesis. Nat. Rev. Chem. 2021, 5, 546–563. 10.1038/s41570-021-00288-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton J.; Jamison T. F. The Assembly and Use of Continuous Flow Systems for Chemical Synthesis. Nat. Protoc. 2017, 12, 2423–2446. 10.1038/nprot.2017.102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capaldo L.; Wen Z.; Noël T. A Field Guide to Flow Chemistry for Synthetic Organic Chemists. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 4230–4247. 10.1039/D3SC00992K. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown D. G.; Boström J. Analysis of Past and Present Synthetic Methodologies on Medicinal Chemistry: Where Have All the New Reactions Gone?. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59, 4443–4458. 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.5b01409. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carey J. S.; Laffan D.; Thomson C.; Williams M. T. Analysis of the Reactions Used for the Preparation of Drug Candidate Molecules. Org. Biomol. Chem. 2006, 4, 2337–2347. 10.1039/b602413k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugger R. W.; Ragan J. A.; Ripin D. H. B. Survey of GMP Bulk Reactions Run in a Research Facility between 1985 and 2002. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2005, 9, 253–258. 10.1021/op050021j. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lipton J. H.; Chuah C.; Guerci-Bresler A.; Rosti G.; Simpson D.; Assouline S.; Etienne G.; Nicolini F. E.; le Coutre P.; Clark R. E.; Stenke L.; Andorsky D.; Oehler V.; Lustgarten S.; Rivera V. M.; Clackson T.; Haluska F. G.; Baccarani M.; Cortes J. E.; Guilhot F.; Hochhaus A.; Hughes T.; Kantarjian H. M.; Shah N. P.; Talpaz M.; Deininger M. W.; investigators E. Ponatinib versus Imatinib for Newly Diagnosed Myeloid Leukaemia: An International, Randomised, Open-Label, Phase 3 Trial. Lancet Oncol. 2016, 17, 612–621. 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00080-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guo P.; Xu Y.; Lv L.; Feng M.; Fang Y.; Cheng S.; Xiao X.; Huang J.; Sheng W.; Wang S.; Chen H. Augmentation with Prazosin for Patients with Depression and a History of Trauma: A Randomised, Double-blind, Placebo-controlled Study. Acta Psychiatr. Scand. 2025, 151, 142–151. 10.1111/acps.13763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshri A.; Gupta A.; Gulati U.; Datt Bhatt T.; Kashyap M.; Laha J. K. A Telescopic, Scalable and Industrially Feasible Method for the Synthesis of Antidepressant Drug, Moclobemide. Helv. Chim. Acta 2024, 107, e202400075. 10.1002/hlca.202400075. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Magano J. Large-Scale Amidations in Process Chemistry: Practical Considerations for Reagent Selection and Reaction Execution. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2022, 26, 1562–1689. 10.1021/acs.oprd.2c00005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Adams J. P.; Alder C. M.; Andrews I.; Bullion A. M.; Campbell-Crawford M.; Darcy M. G.; Hayler J. D.; Henderson R. K.; Oare C. A.; Pendrak I.; Redman A. M.; Shuster L. E.; Sneddon H. F.; Walker M. D. Development of GSK’s Reagent Guides - Embedding Sustainability into Reagent Selection. Green Chem. 2013, 15, 1542–1549. 10.1039/c3gc40225h. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Urbańczyk E.; Sowa M.; Simka W. Urea Removal from Aqueous Solutions - A Review. J. Appl. Electrochem. 2016, 46, 1011–1029. 10.1007/s10800-016-0993-6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wehrstedt K. D.; Wandrey P. A.; Heitkamp D. Explosive Properties of 1-Hydroxybenzotriazoles. J. Hazard. Mater. 2005, 126, 1–7. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2005.05.044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valeur E.; Bradley M. Amide Bond Formation: Beyond the Myth of Coupling Reagents. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2009, 38, 606–631. 10.1039/B701677H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- El-Faham A.; Funosas R. S.; Prohens R.; Albericio F. COMU: A Safer and More Effective Replacement for Benzotriazole-Based Uronium Coupling Reagents. Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 9404–9416. 10.1002/chem.200900615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freiberg K. M.; Kavthe R. D.; Thomas R. M.; Fialho D. M.; Dee P.; Scurria M.; Lipshutz B. H. Direct Formation of Amide/Peptide Bonds from Carboxylic Acids: No Traditional Coupling Reagents, 1-Pot, and Green. Chem. Sci. 2023, 14, 3462–3469. 10.1039/D3SC00198A. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subirós-Funosas R.; Prohens R.; Barbas R.; El-Faham A.; Albericio F. Oxyma: An Efficient Additive for Peptide Synthesis to Replace the Benzotriazole-Based HOBt and HOAt with a Lower Risk of Explosion. Chem. Eur. J. 2009, 15, 9394–9403. 10.1002/chem.200900614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer K. S.; Yirak J. R.; Muchalski H.; Lipshutz B. H. Synthesis of S,S-Di(Pyridin-2-yl)Carbonodithioate (DPDTC) for the Reduction of Carboxylic Acids. Org. Synth. 2024, 101, 274–294. 10.15227/orgsyn.101.0274. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Plutschack M. B.; Pieber B.; Gilmore K.; Seeberger P. H. The Hitchhiker’s Guide to Flow Chemistry. Chem. Rev. 2017, 117, 11796–11893. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.7b00183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alder C. M.; Hayler J. D.; Henderson R. K.; Redman A. M.; Shukla L.; Shuster L. E.; Sneddon H. F. Updating and Further Expanding GSK’s Solvent Sustainability Guide. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 3879–3890. 10.1039/C6GC00611F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Prat D.; Wells A.; Hayler J.; Sneddon H.; McElroy C. R.; Abou-Shehada S.; Dunn P. J. CHEM21 Selection Guide of Classical- and Less Classical-Solvents. Green Chem. 2016, 18, 288–296. 10.1039/C5GC01008J. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Freiberg K. M.; Ghiglietti E.; Scurria M.; Lipshutz B. H. Use of Dipyridyldithiocarbonate (DPDTC) as an Environmentally Responsible Reagent Leading to Esters and Thioesters under Green Chemistry Conditions. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 9941–9947. 10.1039/D3GC03093H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M. J.; Oftadeh E.; Saunders J. M.; Wood A. B.; Lipshutz B. H. Palladium-Catalyzed Aminations in Flow · on Water. ACS Catal. 2024, 14, 1545–1552. 10.1021/acscatal.3c05257. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brotzel F.; Chu Y. C.; Mayr H. Nucleophilicities of Primary and Secondary Amines in Water. J. Org. Chem. 2007, 72, 3679–3688. 10.1021/jo062586z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li B.; Weisenburger G. A.; McWilliams J. C. Practical Considerations and Examples in Adapting Amidations to Continuous Flow Processing in Early Development. Org. Process Res. Dev. 2020, 24, 2311–2318. 10.1021/acs.oprd.0c00112. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dankers C.; Tadros J.; Harman D. G.; Aldrich-Wright J. R.; Nguyen T. V.; Gordon C. P. Immobilized Carbodiimide Assisted Flow Combinatorial Protocol to Facilitate Amide Coupling and Lactamization. ACS Comb. Sci. 2020, 22, 255–267. 10.1021/acscombsci.0c00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atapalkar R. S.; Kulkarni A. A. Direct Amidation of Acids in a Screw Reactor for the Continuous Flow Synthesis of Amides. Chem. Commun. 2023, 59, 9231–9234. 10.1039/D3CC02402D. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orsy G.; Fülöp F.; Mándity I. M. Direct Amide Formation in a Continuous-Flow System Mediated by Carbon Disulfide. Catal. Sci. Technol. 2020, 10, 7814–7818. 10.1039/D0CY01603A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du Y.; Barber T.; Lim S. E.; Rzepa H. S.; Baxendale I. R.; Whiting A. A Solid-Supported Arylboronic Acid Catalyst for Direct Amidation. Chem. Commun. 2019, 55, 2916–2919. 10.1039/C8CC09913H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Su J.; Mo J.; Chen X.; Umanzor A.; Zhang Z.; Houk K. N.; Zhao J. Generation of Oxyphosphonium Ions by Photoredox/Cobaloxime Catalysis for Scalable Amide and Peptide Synthesis in Batch and Continuous-Flow. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2022, 134, e202112668. 10.1002/ange.202112668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheehan J. C.; Cruickshank P. A.; Boshart G. L. A Convenient Synthesis of Water- Soluble Carbodiimides. J. Org. Chem. 1961, 26, 2525. 10.1021/jo01351a600. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sikandar S.; Zahoor A. F.; Naheed S.; Parveen B.; Ali K. G.; Akhtar R. Fukuyama Reduction, Fukuyama Coupling and Fukuyama-Mitsunobu Alkylation: Recent Developments and Synthetic Applications. Mol. Divers. 2022, 26, 589–628. 10.1007/s11030-021-10194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lou J.; Wang Q.; Wu P.; Wang H.; Zhou Y.-G.; Yu Z. Transition-Metal Mediated Carbon-Sulfur Bond Activation and Transformations: An Update. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 4307–4359. 10.1039/C9CS00837C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liebeskind L. S.; Srogl J. Thiol Ester-Boronic Acid Coupling. A Mechanistically Unprecedented and General Ketone Synthesis. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000, 122, 11260–11261. 10.1021/ja005613q. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Iyer K. S.; Nelson C.; Lipshutz B. H. Facile, Green, and Functional Group-Tolerant Reductions of Carboxylic Acids in, or with, Water. Green Chem. 2023, 25, 2663–2671. 10.1039/D3GC00517H. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anastas P. T.; Warner J. C.. Green Chemistry; Theory and Practice; Oxford University Press, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Khoo H. H.; Wong L. L.; Tan J.; Isoni V.; Sharratt P. Synthesis of 2-Methyl Tetrahydrofuran from Various Lignocellulosic Feedstocks: Sustainability Assessment via LCA. Resour., Conserv. Recycl. 2015, 95, 174–182. 10.1016/j.resconrec.2014.12.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wong M. J.; Freiberg K. M.; Reynafarje Jones T.; Dismuke Rodriguez K. B.; Wood A. B.; Lipshutz B. H. SNAr Reactions Using Continuous Plug Flow...in Aqueous Biphasic Media. ACS Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2024, 12, 18725–18734. 10.1021/acssuschemeng.4c08612. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lee N. R.; Bikovtseva A. A.; Cortes-Clerget M.; Gallou F.; Lipshutz B. H. Carbonyl Iron Powder: A Reagent for Nitro Group Reductions under Aqueous Micellar Catalysis Conditions. Org. Lett. 2017, 19, 6518–6521. 10.1021/acs.orglett.7b03216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.