Abstract

The interaction between CD47 expressed on cancer cells and signal regulatory protein-α located on macrophages blocks the phagocytosis of tumor cells by macrophages. Our data reveal that human endometrial cancer cells (hECCs) upregulate the CD47 level on their surface and that there is a high density of tumor-associated macrophages within the microenvironment of human endometrial cancer. In vitro functional assay shows that an anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody (mAb) promotes the phagocytosis of hECCs by macrophages. Systemic and in situ treatments with an anti-CD47 mAb effectively reduce tumor burden in vivo in a genetically engineered mouse model of endometrial cancer. Thus, this study provides preclinical evidence that CD47 blockade using an anti-CD47 mAb to augment macrophage phagocytosis is a potential therapeutic strategy for endometrial cancer.

Keywords: CD47, macrophage, phagocytosis, immunotherapy, endometrial cancer

Keywords: Biological Sciences, Medical Sciences

Significance Statement.

Endometrial cancer (EC) is the leading gynecological malignancy in women with increasing incidence and mortality worldwide. The present study develops a novel EC immunotherapy. CD47 on the surface of human EC cells protects them from clearance by macrophages via phagocytosis. CD47 blockade using a monoclonal antibody effectively augments the phagocytosis of EC cells by macrophages and reduces the tumor burden. In situ immunotherapy via transvaginal administration of anti-CD47 monoclonal antibody is developed here for prompt and maximal clearance of primary EC cells to lower the chances of tumor metastasis and recurrence. In this study, our preclinical findings demonstrate that CD47 blockade is a potential therapeutic approach for treating EC to improve women's health.

Introduction

Conventional cancer treatments, including surgery, chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and hormone therapy, target tumor cells, but often have adverse effects and at times with limited clinical outcomes. Utilizing the intrinsic ability of the immune system to detect and clear diseased cells has become a promising avenue for attacking cancer cells (1). Immunotherapeutic approaches that have demonstrated efficacies thus far, such as targeting cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated protein 4 (CTLA-4) (2) and programmed cell death protein 1 (PD-1) (3), activate T cells. Macrophages are a key functional component of the immune system and play important roles in the phagocytosis of pathogens and diseased cells as well as in the activation of T cells and the production of proinflammatory cytokines (4). In the past decades, accumulating evidence has revealed that enhancing the function of macrophages is a promising approach for cancer immunotherapy (5–7).

Cancer cells can evade immunosurveillance by macrophages through upregulating the expression of CD47 (8–11). CD47 is a transmembrane protein that serves as a ligand to signal regulatory protein-α (SIRPα) expressed on macrophages (12). The interaction between CD47 and SIRPα blocks phagocytosis of cancer cells by macrophages, a biological event called “don't eat me” (7), thus allowing the cancer cells to escape the host immune system to grow and spread. This mechanism has been exploited to develop immunotherapeutic treatments for both hematologic and solid malignancies (7, 13). Most studies use a monoclonal antibody (mAb) for blocking CD47 to augment the phagocytic ability of macrophages to clear tumor cells (8–11, 14–19). Encouraging outcomes have been reported in reducing tumor burden in preclinical models (8–11, 14–17) and early clinical trials (18–20). On the contrary, some clinical trials using an anti-CD47 mAb to treat metastatic urothelial carcinoma did not achieve the expected response rates, although the treatment was tolerated and showed a consistent known safety profile (21). The efficacy of anti-CD47 mAb therapy has not been explored in endometrial cancers (ECs), which drove us to test it in the present study.

EC arises from the inner lining of the uterus and is the leading gynecologic malignancy (22). Patients with EC typically present with abnormal vaginal bleeding and pelvic pain. Due to its prevalence, EC broadly impacts the health and lives of women. The American Cancer Society estimates 69,120 new cases and 13,860 associated deaths in the United States in 2025. Contrary to the trend of decreasing mortality in most solid tumors, EC incidence and mortality have been persistently rising (23). Thus, more effective treatments for EC are necessary.

Here, we describe the development of a CD47 blockade immunotherapy for EC. We show that CD47 is highly expressed in both human and mouse EC cells and that a mAb against CD47 effectively augments the phagocytosis of EC cells by macrophages. We further show that the EC burden in mice is reduced by an anti-CD47 mAb. Thus, CD47 is an effective target for EC immunotherapy and a good candidate for further research regarding its clinical applications in EC treatment.

Results

Pathophysiological properties of human EC

The morphology of fresh human cancerous uterine tissue showed carcinoma at the top of uterine tissue significantly expanded in the endometrium, but noncancerous uterine tissue contained a thin normal endometrium (Fig. 1A). Hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) stain of human cancerous and noncancerous uterine tissue sections further revealed a thick and dispersed EC progression above myometrium (Fig. 1B). Immunofluorescence (IF) staining for EpCAM, a marker of normal and cancerous epithelial cells, mapped an expanded and dispersed EC distribution connecting with the myometrium in human cancerous uterine tissue sections, and a thin layer of normal endometrial epithelium in the noncancerous uterine tissue (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

Pathophysiology of human EC. A) Representative fresh human uterine tissue with (left) and without (right) EC. The black dotted line demarcates the EC at the top and myometrium at the bottom. B) Representative H&E staining of human uterine tissue with (left) and without (right) EC. The cancerous uterine tissue contains a thick EC at the top connected with myometrium at the bottom; the border is outlined by a black dotted line. C) Representative IF staining for EpCAM in human uterine tissue section with (left) and without (right) EC. The cancerous uterine tissue contains a thick EpCAM-labeled (magenta) EC top layer connected with bottom myometrium stained with DAPI as blue. The right noncancerous uterine tissue contains a thin EpCAM-labeled magenta normal endometrial layer above the blue bottom myometrium. Twenty uterine samples with cancer and 16 uterine samples without cancer were analyzed. EpCAM is a specific marker of normal epithelial cells or carcinoma cancer cells. DAPI staining was used to label cell nuclei and to assess gross cell morphology. Scale bar: centimeter (CM) in A) and 1,000 μm in B) or C).

Human EC cells upregulate their CD47 expression

To determine the location, distribution, and level of CD47 in human EC, we performed RT-PCR and IF staining for gene and protein expression, respectively. The mRNA level of CD47 in human EC tissue had a 2-fold change increase compared with that of the control postmenopausal (PM) endometrium (Fig. S1). The CD47 protein was expressed on the surface of both normal epithelial cells in the control PM endometrium and cancerous cells in human EC tissue (Fig. 2A). The endometrial glands of PM samples had a basal expression of CD47, whereas the human EC cells (hECCs) had higher CD47 expression level. The specificity of CD47 staining was supported by nondetection of its isotype IgG1 control and secondary antibody control staining without the primary antibody (Fig. S2). KI67 staining revealed that PM epithelial cells rarely proliferated, whereas most cancer cells were actively proliferating (Figs. 2 and S3, 4 ± 2 vs. 45 ± 6, P < 0.001) to support cancer growth and progression, which resulted in a thick, expanded, and dispersed EC distribution, observed in Fig. 1. To determine the level of CD47, we used two quantification methods. We quantified the intensity of the IF staining signal of CD47 in EC and PM glands using ImageJ software and found a significant difference between the two groups (Fig. 2B; 48 ± 13 AU in PM glands, 81 ± 34 AU in EC; P < 0.0001). We also used enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) to measure the CD47 protein level in EC and PM tissue homogenates, using 30 μg of total protein per sample. The ELISA data showed a significant difference between two groups (Fig. 2C; 200 ± 53 pg in PM endometrium, 252 ± 117 pg in EC; P < 0.05) consistent with the fluorescence intensity analysis. Thus, there is an increased expression of CD47 on hECC surfaces.

Fig. 2.

Up-regulation of CD47 expression in hECCs. A) IF staining of CD47 on human uterine tissue sections with (EC, n = 42) or without (PM, n = 23) EC. A stronger green fluorescence signal of CD47 staining on the surface of hECCs was detected compared with control PM endometrial epithelia with a basal level of fluorescence signal (PM). EpCAM was applied to label carcinoma cancer cells in EC or normal epithelial cells in PM shown as magenta. The cell proliferation was assessed by KI67 antibody staining as red. The quantification of cell proliferation is shown in Fig. S3. Blue DAPI staining was used to label cell nuclei and to assess gross cell morphology. B) Fluorescence intensity of CD47 staining in EC (n = 42) and PM (n = 23). ImageJ was used to measure the fluorescence staining signal of CD47. Thirty stained spots in EC or PM epithelium per human uterine sample were randomly captured for analysis. AU, arbitrary units. C) Level of CD47 protein in EC (n = 34) or PM (n = 16). ELISA was used to measure the CD47 protein level in EC tissue homogenate or in control endometrial tissue homogenate of PM. Thirty micrograms of total protein per human endometrial sample were used. Each dot in B) and C) represents a uterine tissue sample from a different patient. Data were analyzed by t test using Prism 10. *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001. Scale bar: 100 μm.

Immune cell infiltration in human EC

IF staining of CD68+ macrophages, CD4+ helper T cells, and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in human EC and PM tissue sections revealed that macrophages, helper T cells, and cytotoxic T cells were more abundant in the human EC compared with control PM uterine tissue (Fig. 3). Quantification of CD68+ macrophages showed 10 ± 7 macrophage cells in PM endometrium and 94 ± 75 macrophage cells in EC with a significant difference between two groups (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3A). Quantification of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells showed 7 ± 6 cytotoxic T cells in PM endometrium and 45 ± 58 cytotoxic T cells in EC with a significant difference between two groups (P < 0.05) (Fig. 3B). Quantification of CD4+ helper T cells showed 10 ± 8 helper T cells in PM endometrium and 49 ± 38 helper T cells in EC with a significant difference between two groups (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3C). The staining and quantification indicated a high density of tumor-associated CD68+ macrophages (TAMs), CD8+ cytotoxic T cells, and CD4+ helper T cells in human EC (Fig. 3). A significant immune cell infiltration was observed in human EC tissue.

Fig. 3.

Significant tumor-associated immune cell infiltration in human EC. A) Assessment of CD68+ macrophages in human uterine endometrium with (EC) or without (PM) cancer. IF staining for CD68 was applied to identify TAMs in human EC (n = 38) or normal macrophages in control PM endometrium (n = 23) shown as green. Quantification of CD68+ TAMs in human EC and normal macrophages in PM. B) Assessment of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in human uterine endometrium with (EC) or without (PM) cancer. IF staining for CD8 was applied to identify cytotoxic T cells in human EC (n = 22) or in control PM endometrium (n = 18) shown as green. Quantification of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in human EC and PM. C) Assessment of CD4+ helper T cells in human uterine endometrium with (EC) or without (PM) cancer. IF staining for CD4 was applied to identify helper T cells in human EC (n = 26) or in control PM endometrium (n = 13) shown as green. Quantification of CD4+ helper T cells in human EC and PM. The immune cells within a tissue area of 0.29 mm2 under 40× magnification were counted based on the green fluorescence signal using a Leica DM5500 B automated upright microscope. At least four tissue areas in EC or PM endometrium per human uterine sample were randomly captured for analysis. Each dot in the quantification charts represents a uterine tissue sample from a different patient. Data were analyzed by t test using Prism 10. ****P < 0.0001; **P < 0.05. Scale bar: 200 μm.

CD47 protects hECCs from phagocytosis by macrophages

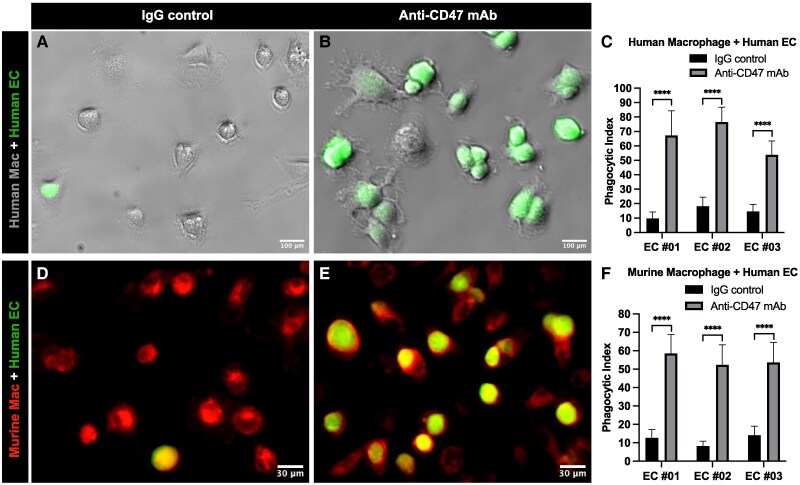

To determine the impact of CD47 overexpression in the interaction of hECCs and macrophages, we used a classical phagocytosis assay (9–11). Extensive studies have shown that human cancer cells can interact with and be phagocytosed by both human and mouse macrophages in this assay system (9). We applied both primary human and mouse macrophages to evaluate the impact of anti-CD47 monoclonal antibodies on phagocytosis of hECCs. First, macrophages derived from the human peripheral blood monocytes were incubated with carboxyfluorescein succinimidyl ester (CFSE)-labeled green primary hECCs in the presence of IgG1 isotype control (Fig. 4A) or an anti-CD47 antibody (clone: B6H12) (Fig. 4B). The co-culture results showed that green hECCs were extensively ingested by human macrophages in the anti-CD47 antibody treatment group (Fig. 4B). Phagocytic index of three independent human EC samples showed that the phagocytosis of hECCs by human macrophages was significantly augmented by an anti-CD47 mAb, compared with the IgG1 isotype control (EC#01: 10 ± 4 vs. 67 ± 17, P < 0.0001; EC#02: 18 ± 6 vs. 77 ± 10, P < 0.0001; EC#03: 15 ± 5 vs. 54 ± 9, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4C). Phagocytosis analysis by flow cytometry of three independent human macrophage samples showed the same pattern that phagocytic index is significantly higher in the anti-CD47 antibody treatment group than in the control group (Fig. S4, 15 ± 3 vs. 56 ± 7, P < 0.01). Second, macrophages expressing red fluorescent protein (RFP) derived from B6.Cg-Tg(CAG-mRFP1)1F1Hadj/J transgenic mouse bone marrow were incubated with CFSE-labeled green hECCs in the presence of IgG1 isotype control (Fig. 4D) or an anti-CD47 mAb (clone: B6H12) (Fig. 4E). The co-culture results showed that green hECCs were extensively ingested by red mouse macrophages in the anti-CD47 mAb treatment group (Fig. 4E). Phagocytic index of three independent human EC samples suggested that the phagocytosis of hECCs by mouse macrophages was significantly augmented by anti-CD47 mAb, compared with the IgG1 isotype control (EC#01: 13 ± 4 vs. 59 ± 10, P < 0.0001; EC#02: 8 ± 2 vs. 52 ± 10, P < 0.0001; EC#03: 14 ± 5 vs. 54 ± 10, P < 0.0001) (Fig. 4F). Thus, blockade of the CD47–SIRPα interaction using monoclonal antibodies against CD47 results in an increasing phagocytosis of hECCs.

Fig. 4.

CD47 protects hECCs from phagocytosis by macrophages. Phagocytosis assay using primary hECCs and healthy human macrophages. CFSE-labeled green hECCs (green) were incubated with macrophages derived from human peripheral blood monocytes in the presence of IgG1 isotype control (A) or an anti-CD47 (clone B6H12) mAb antibody (B), and their phagocytic indices were calculated (C). Phagocytosis assay using primary hECCs and normal mouse macrophages. CFSE-labeled hECCs (green) were incubated with RFP-labeled mouse bone marrow-derived macrophages in the presence of IgG1 isotype control (D) or an anti-CD47 (clone B6H12) mAb (E), and their phagocytic indices were calculated (F). The human macrophages were derived from one healthy human sample. The primary EC cells isolated from three independent human EC samples (EC#01, EC#02, and EC#03) were used. Each experiment was repeated for three times. More macrophages containing ingested green cancer cells were found in the anti-CD47 antibody treatment groups. Two-way ANOVA was performed with GraphPad Prism 10 for statistical analysis. ****P < 0.0001. Scale bar: 100 μm in human macrophage + human EC; 30 μm in murine macrophage + human EC.

Similar human EC phenotypes are reflected in EC mouse model

To evaluate the potential in vivo therapeutic efficacy of CD47 blocking antibodies, we used a mouse EC model. The tumor suppressor gene PTEN is frequently mutated in human EC. PR-cre+/−;Ptenflox/flox female mice, in which Pten is deleted in the progesterone receptor (PR)-expressing uterine cells (24), have been extensively used as a reliable model for EC research. Previous studies have demonstrated that PR-cre+/−;Ptenflox/flox female mice develop endometrial hyperplasia starting at 10 days old, which progresses into cancer, and the severity of EC increases with age. One-month-old female mice with a severe EC burden were used in the current study (Fig. S5). In the mouse EC, a high expression of CD47 was observed (Fig. S6). Similar to that in humans (Fig. 3), a significant immune cell infiltration was observed in mouse EC (Fig. S7). Compared with the control wild-type uteri, higher densities of F4/80+ TAMs (Fig. S7A, 402 ± 68 vs. 100 ± 18, P < 0.0001), CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (Fig. S7B, 177 ± 19 vs. 21 ± 7, P < 0.0001), and CD4+ helper T cells (Fig. S7C, 165 ± 37 vs. 19 ± 3, P < 0.0001) were observed in EC.

Systemic treatment with an anti-CD47 mAb reduces EC burden

Systemic treatment with an anti-CD47 mAb (clone: miap301) via intraperitoneal (IP) injection (Fig. 5A) showed that the growth and progression of EC were effectively inhibited. The size (Fig. 5B) of uteri in the anti-CD47 mAb treatment group was decreased. The average weight of uteri in the anti-CD47 mAb treatment group was significantly reduced compared with these of the control IgG treatment group (Fig. 5E, 1.9 ± 0.5 vs. 1.2 ± 0.4 g, P < 0.05). Histology analysis (Fig. 5C) including H&E stain and EpCAM IF of uterine cross-sections showed that the uteri after treatment with an anti-CD47 mAb contained fewer green EpCAM-labeled EC cells (Fig. 5G, 2.6 ± 1 vs. 0.7 ± 0.5 mm2, P < 0.0001) compared with that after treatment with the control IgG. Further analysis of immune cells (Fig. 5D) posttreatment revealed densities of both CD4+ helper T cells (Fig. 5H, 131 ± 31 vs. 87 ± 13, P < 0.0001) and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (Fig. 5I, 148 ± 42 vs. 89 ± 25, P < 0.0001) decreased in anti-CD47 mAb group compared with the control IgG group. Of note, the body weight of mice treated systemically with an anti-CD47 mAb did not differ significantly from that of mice treated with the control IgG (Fig. 5F, 21.5 ± 1.7 vs. 21.7 ± 1.0 g, P > 0.05) and mice of both groups were active during treatments, indicating that the anti-CD47 treatment did not cause an overt toxic effect to these mice.

Fig. 5.

Systemic treatment with an anti-CD47 mAb reduces EC burden. A) A schematic of systemic treatment with a CD47 blocking antibody. Anti-CD47 mAb (n = 7 mice) or control IgG (n = 8 mice) was given via IP injection to 1-month-old PR-cre+/−;Ptenflox/flox female mice twice per week for 8 weeks at 100 μg in 100 μL PBS per injection each mouse. B) Morphology of uteri posttreatment. Representative uteri from either anti-CD47 mAb or control IgG treatment groups were dissected out and imaged. C) Histology analysis of uteri posttreatments. H&E staining of uterine cross tissue sections shows a thin endometrium in the anti-CD47 mAb treatment group. IF staining of EpCAM was applied for labeling EC cells shown as green. D) Assessment of CD4+ helper T cells or CD8+ cytotoxic T cells by IF staining in uterus tissue from anti-CD47 mAb or control IgG treatment groups. E) Weight of uteri posttreatment with an anti-CD47 mAb or control IgG. F) Weight of bodies posttreatment with an anti-CD47 mAb or control IgG. G) EpCAM+ epithelia tumor area in uterus tissue from anti-CD47 mAb or control IgG treatment groups. H) Quantification of CD4+ helper T cells in uterus tissue from either anti-CD47 mAb or control IgG treatment groups. I) Quantification of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in uterus tissue from either anti-CD47 mAb or control IgG treatment groups. Blue DAPI staining was used to label cell nuclei and to assess gross cell morphology. Each dot in E) and F) represents an individual animal. The size of the green EpCAM+ area of fluorescence was measured using ImageJ software to evaluate tumor size, at least five cross-sectional images per uterus for analysis, three uteri per treatment. The immune cells within a tissue area of 0.29 mm2 under 40× magnification were counted based on the red fluorescence signal using a Leica DM5500 B automated upright microscope. At least nine tissue areas in each mouse uterus were randomly captured for analysis, three uteri per treatment. Data were analyzed by t test using Prism 10. *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001; nsP > 0.05. Scale bar: 1,000 μm in C) and 100 μm in D).

In situ treatment of anti-CD47 mAb reduces EC burden

Tumor cell clearance at the primary site is of importance, because most cancer-related deaths including that of EC are caused by tumor metastasis and recurrence (25). We developed an in situ therapy via transvaginal (TV) administration of anti-CD47 mAb to facilitate direct and maximal targeting of primary EC cells (26). TV delivery of anti-CD47 mAb (clone: miap301) or control IgG1 was given daily to the female PR-cre+/−;Ptenflox/flox mice for 8 weeks at 10 μL of 25 μg per delivery for each mouse (Fig. 6A). The results showed that growth and progression of EC were effectively inhibited by the anti-CD47 mAb. The size (Fig. 6B) of uteri in the anti-CD47 mAb treatment group was decreased. The average weight of uteri in the anti-CD47 mAb treatment group was significantly reduced compared with those of the control IgG treatment group (Fig. 6E, 1.5 ± 0.6 vs. 0.6 ± 0.2 g, P < 0.05). Histology analysis (Fig. 6C) including H&E stain and EpCAM IF of uterine cross-sections showed that the uteri after treatment with anti-CD47 mAb contained fewer green EpCAM-labeled EC cells (Fig. 6G, 2.4 ± 0.7 vs. 0.4 ± 0.1 mm2, P < 0.0001) compared with those of the control IgG treatment. Further analysis of immune cells (Fig. 6D) posttreatment revealed the densities of both CD4+ helper T cells (Fig. 6H, 134 ± 36 vs. 95 ± 14, P < 0.0001) and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells (Fig. 6I, 120 ± 38 vs. 95 ± 13, P < 0.0001) decreased in the anti-CD47 mAb group compared with the control IgG group. Of note, the body weight of mice treated locally with an anti-CD47 mAb did not differ significantly from that of mice treated with the control IgG (Fig. 6F, 21.8 ± 1.2 vs. 21.1 ± 1.2 g, P > 0.05), and all mice were active during the treatments, indicating that local treatment with an anti-CD47 mAb did not cause overt toxicity.

Fig. 6.

In situ treatment with an anti-CD47 mAb reduces EC burden. A) A schematic of in situ treatment with a CD47 blocking antibody. Anti-CD47 mAb (n = 10 mice) or control IgG (n = 5 mice) was given daily via TV delivery to 1-month-old PR-cre+/−;Ptenflox/flox female mouse uterine lumen for 8 weeks at 10 μL of 25 μg per delivery each mouse. B) Morphology of uteri posttreatment. Representative uteri from anti-CD47 mAb or control IgG treatment groups were dissected out and imaged. C) Histology analysis of uteri posttreatments. H&E staining of uterine cross tissue sections shows a thin endometrium in the anti-CD47 mAb treatment group. IF staining of EpCAM was applied for labeling EC cells shown as green. D) Assessment of CD4+ helper T cells or CD8+ cytotoxic T cells by IF staining in uterus tissue from anti-CD47 mAb or control IgG treatment groups. E) Weight of uteri posttreatment with an anti-CD47 mAb or control IgG. F) Weight of bodies posttreatment with an anti-CD47 mAb or control IgG. G) EpCAM+ epithelia tumor area in uterus tissue from anti-CD47 mAb or control IgG treatment groups. H) Quantification of CD4+ helper T cells in in uterus tissue from either anti-CD47 mAb or control IgG treatment groups. I) Quantification of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells in uterus tissue from either anti-CD47 mAb or control IgG treatment groups. Blue DAPI staining was used to label cell nuclei and to assess gross cell morphology. Each dot in E) and F) represents an individual animal. The size of the green EpCAM+ area of fluorescence was measured using ImageJ software to evaluate tumor size, at least five cross-sectional images per uterus for analysis, three uteri per treatment. The immune cells within a tissue area of 0.29 mm2 under 40× magnification were counted based on the red fluorescence signal using a Leica DM5500 B automated upright microscope. At least nine tissue areas in each mouse uterus were randomly captured for analysis, three uteri per treatment. Data were analyzed by t test using Prism 10. *P < 0.05; ****P < 0.0001; nsP > 0.05. Scale bar: 1,000 μm in C) and 100 μm in D).

In situ treatment of anti-CD47 mAb results in better outcomes

A further comparative analysis of the uterine weight and EpCAM+ tumor area from mice treated with systemic or in situ anti-CD47 mAb revealed that in situ treatment of anti-CD47 mAb results in better outcomes. Lower uterus weight (Fig. S8A, 1.2 ± 0.4 vs. 0.6 ± 0.2 g, P < 0.05) and smaller EpCAM+ tumor area (Fig. S8B, 0.7 ± 0.5 vs. 0.4 ± 0.1 mm2, P < 0.05) were observed in the in situ anti-CD47 mAb treatment group (TV) compared with the systemic treatment group (IP), which indicates that in situ treatment was more effective than systemic treatment in reducing primary EC burden.

Discussion

Carcinogenesis is a biological game of hide-and-seek between tumor cells and the immune system. In most cases, the tumor is able to bypass the immune system, progressing or metastasizing by the time of diagnosis (1. 25). The pathology of human EC (Fig. 1) suggests most cancerous endometria will have significant morphological changes at the time of resection. Thus, the key for understanding carcinogenesis and developing effective therapies is to reveal how the tumor cells can evade immunosurveillance.

In most solid tumors, the cancer microenvironment demonstrates infiltration of immune cells, with macrophages being the most abundant (27). In this study, we observed high densities of tumor-associated CD68+ macrophages, CD4+ helper T cells, and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells surrounding the tumor cells in human EC (Fig. 3). The massive proliferation of EC cells despite extensive immune cell infiltration and accumulation in the tumor microenvironment further supports the ability of cancer cells to evade host immunosurveillance. Peripheral lymphocytes and monocytes are attracted to the primary tumor site by chemokines secreted by the tumor cells, leading to T cell and macrophage infiltration (28). The chemoattractant colony-stimulating factor-1 attracts monocytes to the primary tumor site for maturation into macrophages (10, 29, 30). The infiltrating immune cells at the local tumor site are the best targets for immunotherapy, facilitating host defense against tumor cells. Thus, activation of CD8+ cytotoxic T cells via blocking their surface receptors CTLA-4 or PD1 appears to be an effective anti-tumor treatment in solid tumors including EC (2, 3, 31, 32). The current understanding of the potential roles of TAMs in the tumor microenvironment is dynamic. One explanation focuses on the M1 or M2 polarization of macrophages, where the M1 phenotype allows them to attack cancer cells, but TAMs predominant exhibit the M2 phenotype, which supports cancer progression (33). However, some reports (34) suggest a more complicated function of TAMs in carcinogenesis, which may not be fully explained by the M1/M2 polarization. Regardless, it is likely that inhibitory signals block macrophage immunosurveillance for tumors to grow and spread (5–7).

In the past decade, accumulating evidence reveals that CD47 on the surface of human hematologic and solid tumor cells signals “don't eat me” to phagocytic cells to evade immunosurveillance (8–11). Here, we demonstrate that hECCs upregulate their surface CD47 expression to escape phagocytosis by macrophages (Figs. 1–4). The CD47/SIRPα signaling is the best-characterized immune checkpoint that controls the interaction between macrophages and tumor cells (13). The strategy of blocking the binding between CD47 and SIRPα to facilitate macrophage phagocytosis of cancer cells is being applied in both preclinical models and clinical trials for hematologic and solid malignancies (8–11, 14–20). In an aggressive leiomyosarcoma model, anti-CD47 mAb treatment was effective in promoting macrophage phagocytosis of tumor cells, as well as inhibiting tumor progression and metastasis. There have been promising results in both in vitro and in vivo studies using an anti-CD47 mAb to target a wide range of human solid tumors, including ovarian, breast, bladder, and colon cancer and glioblastoma. A clinical trial with a humanized anti-CD47 antibody treatment achieved tumor burden reductions in ovarian and fallopian tube cancers (19).

In this study, we explore CD47 blockade immunotherapy as a novel therapy for EC. As in most solid tumors, CD47 is upregulated in both human and mouse EC at level of gene and protein (Figs. 2, S1, and S6) (35, 36). An anti-CD47 mAb enables both human and mouse macrophages to attack hECCs (Figs. 4 and S4). As in humans (Fig. 3), a significant immune cell infiltration including macrophages and T cells is observed in the mouse EC tissue (Fig. S7). Both systemic and local treatments with an anti-CD47 mAb in EC mice models show promising anticancer properties (Figs. 5 and 6). Progression of EC has been significantly inhibited by anti-CD47 mAb, and tumor burden is effectively ameliorated under both routes of administration. These results plus others (35–37) support “don't eat me” signaling CD47 as a key player in EC progression. The mAb against CD47 blocks the interaction between CD47 on tumor cells and SIRPα on macrophages allowing the macrophages to restore their phagocytic ability, which may also include the potential polarization conversion of TAMs from M2 to M1 (37). Beyond enabling macrophage phagocytosis, the anti-CD47 mAb may also activate CD8+ cytotoxic T cells through matricellular glycoprotein thrombospondin-1 to attack EC cells (38). The decreased densities of both CD4+ helper T cells and CD8+ cytotoxic T cells at the end of treatment with anti-CD47 mAb (Figs. 5 and 6) reflect amelioration of cancer microenvironment. Thus, our findings in EC along with other studies in various solid tumors support that CD47 blockade may restore macrophage immunosurveillance and functionally alter the tumor microenvironment, resulting in tumor burden reduction.

An efficacy comparison of systemic and local treatment shows that in situ treatment of anti-CD47 mAb via TV delivery results in greater reduction of EC burden (Fig. S8). The TV method delivers anti-CD47 mAb precisely and directly to EC cells and their tumor microenvironment where TAMs and T cells are located. The enriched TAMs and T cells at the primary EC site (Figs. 3 and S7) are the best line of defense against tumor cells. This in situ treatment results in prompt and maximal clearance of primary EC cells by these infiltrating immune cells, which is key to lowering the risk of tumor metastasis and recurrence. Because immune cell infiltration is a common phenotype in most solid tumors, in situ immunotherapy against primary cancer may have implications in the treatment of other solid tumors, especially in premetastatic stages.

Prior to clinical application, possible toxicity of the anti-CD47 mAb should be investigated further. Several studies on anti-CD47 mAb treatment in animals did not observe significant toxic effects (9–11), one of which found that anti-CD47 mAb treatment improved survival in mice with acute myeloid leukemia (9). The dosage of anti-CD47 mAb used in our study was lower than that used in these studies. We did not observe any severe adverse effects such as body weight reduction or deaths as a result of anti-CD47 mAb treatment (Figs. 5 and 6). In humans, an early clinical trial in ovarian cancer has shown that CD47 blockade is tolerable and has promising anticancer efficacy (19). Further clinical trials in certain cancer types using systemic infusion of anti-CD47 mAb showed adverse effects, most significant being hemolytic anemia (20, 39). Anti-CD47 mAb-treated mice in this study did not display overt signs of severe hemolytic anemia such as jaundice, sluggishness, or gross hematuria. The toxicity and adverse effect profile previously displayed in other cancer types will help us optimize the dosage and frequency of treatment with anti-CD47 mAb for clinical application in human EC. In situ anti-CD47 mAb treatment limits potential adverse effects due to locally controlled toxicity. A combination of low-dose systemic infusion plus in situ treatment may be another strategy for reducing the cancer burden without apparent toxicity in treating endometrial or other cancers.

Conclusion

We developed a preclinical immunotherapy for EC via blockade of the CD47/SIRPα axis. Our data in both humans and mice reveal a high CD47 expression on the surface of EC cells that blocks macrophage phagocytosis, but the anti-CD47 mAb can disrupt this interaction and allow clearance of tumor cells. Thus, our study provides a rationale for evaluating the clinical efficacy of anti-CD47 mAb as an immunotherapeutic agent in EC.

Materials and methods

Human uterine tissue samples

A Gynecologic Biobank for the Women's Reproductive Health and Disease received approval from the University of Missouri Institutional Review Board to obtain deidentified uterine samples from patients with EC and PM patients without cancer. An informed consent was received and signed by patients prior to tissue collection. Endometrial carcinoma derived from epithelium represents the most common EC in women, which is also an aging-related gynecologic disease (22). In the current study, deidentified human endometrial adenocarcinoma samples and PM control samples were received for research. The patient diagnoses were verified by pathology. The control samples were chosen from PM women without cancer, as most EC patients were PM. Our study investigated 42 human endometrial carcinoma samples and 23 PM noncancerous uterine samples as control.

Histology and immunohistochemistry

H&E and immunohistochemistry stains were done following our published protocol (40, 41). Fresh human uterine tissue and mouse uteri were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde/phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) overnight or longer at 4 °C depending on tissue size, then washed extensively with PBST, transferred through serial sucrose/PBST, and embedded in optimal cutting temperature (OCT) compound (Tissue Tek) for cryosection. Ten micrometers of thickness tissue sections were made using LEICA CM3050S cryostat. For IF staining, the tissue sections were incubated with primary antibodies in PBST overnight at 4 °C. The following day, tissue slides were washed three times with PBST (10 min/wash), incubated with secondary antibodies for at least 2 h at room temperature, washed with PBST three times (10 min/wash), stained by DAPI for 5 min, and washed with PBST three times before mounting in Fluoromount G (SouthernBiotech). The staining was imaged using a Leica fluorescence microscope. Primary antibodies used were as follows: anti-hEpCAM (BioLegend, 1:500), anti-mEpCAM (BioLegend, 1:500), anti-hCD47 (eBioscience, 1:500), anti-mCD47 (BioLegend, 1:500), anti-CD68 (Invitrogen, 1:500), anti-F4/80 (Bio-Rad, 1:500), anti-KI67 (Bio SB, 1:500), anti-hCD4 (BioLegend, 1:500), anti-mCD4 (BioLegend, 1:500), anti-hCD8 (BioLegend, 1:500), and anti-mCD8 (BioLegend, 1:500). Alexa Fluor 488- and Alexa Fluor 568-conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen) against specific species were used for detection (Molecular Probes, 1:1,000). DAPI (Sigma) was used at 1 mg/mL for DNA staining.

CD47 mRNA level in human uterine tissue

Total RNA of each homogenized sample was extracted using TRIzol/chloroform and quantitated in a NanoDrop One (Thermo Scientific, USA). Reverse transcription was carried out using 1 µg of total RNA employing iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, USA). Relative quantification was performed in triplicate on a 7500 Fast Real-Time PCR System (Applied Biosystems, USA) using SsoAdvanced Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad, USA) according to the manufacturer's recommendations. Quantitative Real-Time PCR data were obtained as Ct values used later in statistical analysis. Primer pairs were Homo CD47 (AGAAGGTGAAACGATCATCGAGC; CTCATCCATACCACCGGATCT) and Homo GAPDH (CTGGGCTACACTGAGCACC; AAGTGGTCGTTGAGGGCAATG) for the target gene and reference gene, respectively. The relative gene expression was evaluated by fold-change, calculated by (42).

CD47 protein level in human uterine tissue

Two methods were applied to measure the level of CD47 expression. (i) ImageJ software was used to measure the fluorescence intensity of CD47 staining in human uterine tissue sections (43). A stained region was selected using a circular tool with set area, and mean gray value measurements were obtained using “Analyze.” Background values of nonstained areas were measured in the same way. Thirty stained areas and 30 background areas were imaged from each patient for analysis. The fluorescence intensity value was calculated as the mean gray value of the stained area minus the background area. The unit is arbitrary units (AU). (ii) ELISA. Per instruction of Human CD47 DuoSet ELISA kit (catalog #: DY4670-05, R&D Systems), human endometrial tissue homogenate was used for CD47 protein measurement. Thirty micrograms of total protein per human uterine sample were used.

Measurement of EpCAM+ tumor area

ImageJ analysis software was used to measure the EpCAM+ tumor area. The EpCAM+ tumor areas in the captured images were selected under Color Threshold to get the value of area at μm2. The data were represented as mm2.

Primary hECC dissociation and culture

Fresh tumor specimens were mechanically chopped into small pieces of around 1–2 mm and cultured in gelatin-coated plates. A monolayer of EC cells formed through migration from cancerous tissue pieces attached to the coated bottom of culture plates. The culture was grown in DMEM/F12 with glutamine + 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) + antibiotic–antimycotic under 37 °C.

Macrophage preparation

Macrophages were derived from healthy human peripheral blood monocytes and B6.Cg-Tg(CAG-mRFP1)1F1Hadj/J transgenic mouse bone marrow. Human peripheral blood macrophages were received from STEMCELL TECHNOLOGY and prepared as described previously (9, 10). Mouse marrow was flushed out from femurs and tibias and placed into a sterile suspension of PBS (9, 10). Human macrophages and mouse marrow were cultured in RPMI 1640 media with 10% FBS and 10 ng/mL macrophage colony-stimulating factor (PeproTech) in 37 °C for 7–10 days before phagocytosis assay.

In vitro phagocytosis assays

Following the published protocol (9–11), 5 × 104 human or murine macrophages were plated per well in a 24-well tissue culture plate. The next day, media were replaced with serum-free RPMI 1640. Meanwhile, primary hECCs isolated from three donors (EC #01, EC #02, and EC #03) were labeled with 2.5 μM CFSE according to the manufacturer's protocol (Invitrogen). Macrophages were incubated in serum-free media for 2 h before adding 2 × 105 CFSE-labeled hECCs. Isotype control IgG1 or blocking anti-CD47 antibodies (clone B6H12, eBioscience) were added at a concentration of 10 μg/mL in the cocultures of hECCs + macrophages for 2 h of incubation at 37 °C. At the end of the incubation, noningested hECCs were washed out, and macrophages were then analyzed by fluorescence microscopy or flow cytometry to determine the phagocytosis. For fluorescence microscopy analysis, phagocytic index as the number of cells ingested per 100 macrophages was measured; at least five fields were counted in each well, with three repeat wells of each treatment and three repeats of each independent experiment. An established protocol was applied for flow cytometry analysis (44). After co-culture, phagocytosis assays were stained with Alexa Fluor 647 anti-CD11b (BioLegend) to identify human macrophages. Phagocytosis was measured as a percentage of the number of CD11b+;CFSE+ macrophages in the total CD11b+ macrophages.

Mice

PR-Cre+/−;Ptenflox/flox mice were generated through breeding B6.129S4-Ptentm1Hwu/J with PR-Cre mice. Female PR-Cre+/−;Ptenflox/flox mice at 1 month old were used. B6.129S4-Ptentm1Hwu/J (JAX:006440) (45) and control C57Bl/6J mice (JAX:000664) were obtained from Jackson Laboratory. PR-Cre mice were provided by Dr. Lydon (46). All procedures were approved by the University of Missouri Animal Care and Use Committee.

Antibody administration to animals

Systemic injection of anti-CD47 mAb (clone: miap301, BioLegend) or control IgG2a (BioLegend) was given via IP injection to the female PR-Cre+/−;Ptenflox/flox mice initially at 1 month old and then twice per week for 8 weeks at 100 μg in 100 μL PBS per injection. Ten microliters of 25 μg of the same anti-CD47 antibody or control IgG2a were TV delivered to the uteri of female PR-Cre+/−;Ptenflox/flox mice initially at 1 month old through a sterilized plastic tip connected to a pipette and then daily for 8 weeks. The tip holding the antibody was gently inserted into the vagina of female PR-Cre+/−;Ptenflox/flox mouse, and then, the pipette plunger was slowly pushed down all the way to make sure that all 10 μL of the antibody had been pushed out of the tip and into the vagina and uterus (47). The empty pipette tip was gently removed after delivery. All animals were euthanized for evaluation of tumor size and microenvironment after 8 weeks of treatment.

Statistics

Data were analyzed using Prism 10 software (GraphPad Software, Inc.). The Welch corrected Student's t test was applied to calculate all column statistics. For multiple comparisons, ANOVA was used. Bar graphs represent mean ± SD. All data were considered statistically significant with P value < 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to the patients for their generous donation of uterine tissue for this study. This manuscript was edited at Life Science Editors ($1529).

Contributor Information

Kerem Yucebas, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women's Health, School of Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA.

Sooah Ko, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women's Health, School of Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA.

Jinyu Zhou, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women's Health, School of Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA.

Elizabeth M Hamel, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women's Health, School of Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA.

Mia G Hackworth, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women's Health, School of Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA; College of Arts and Sciences, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA.

Edgar Andres Diaz Miranda, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women's Health, School of Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA.

Haley S Carpenter, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women's Health, School of Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA.

Mark I Hunter, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women's Health, School of Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA.

Omair M Khan, Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305, USA; Department of Pathology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

Irving L Weissman, Institute for Stem Cell Biology and Regenerative Medicine, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305, USA; Department of Pathology, Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, CA 94305, USA.

Shiying Jin, Department of Obstetrics, Gynecology and Women's Health, School of Medicine, University of Missouri, Columbia, MO 65211, USA.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary material is available at PNAS Nexus online.

Funding

This work was supported by MizzouForward Undergraduate Research Training grant (M.G.H.) and National Institutes of Health grant 1R56HD104821-01A1 (S.J.).

Author Contributions

K.Y. was involved in data curation, software, formal analysis, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, and writing—original draft. S.K. was involved in data curation, software, formal analysis, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, and writing—review and editing. J.Z. was involved in data curation, investigation, and validation. E.M.H. was involved in data curation and investigation. M.G.H. was involved in formal analysis, validation, and investigation. E.A.D.M. was involved in software, formal analysis, validation, and writing—review and editing. M.I.H. was involved in investigation. O.M.K. was involved in formal analysis, methodology, and writing—review and editing. H.S.C. was involved in formal analysis and editing. I.L.W. was involved in formal analysis, investigation, and writing—review and editing. S.J. was involved in conceptualization, resources, data curation, software, formal analysis, acquisition, validation, investigation, visualization, methodology, writing—original draft, project administration, and writing—review and editing.

Data availability

All data are included in the manuscript and supporting information.

References

- 1. Mellman I, Coukos G, Dranoff G. 2011. Cancer immunotherapy comes of age. Nature. 480(7378):480–489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Leach DR, Krummel MF, Allison JP. 1996. Enhancement of antitumor immunity by CTLA-4 blockade. Science. 271(5256):1734–1736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Iwai Y, et al. 2002. Involvement of PD-L1 on tumor cells in the escape from host immune system and tumor immunotherapy by PD-L1 blockade. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 99(19):12293–12297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hirayama D, Iida T, Nakase H. 2017. The phagocytic function of macrophage-enforcing innate immunity and tissue homeostasis. Int J Mol Sci. 19(1):92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Jaiswal S, Chao MP, Majeti R, Weissman IL. 2010. Macrophages as mediators of tumor immunosurveillance. Trends Immunol. 31(6):212–219. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Feng M, et al. 2019. Phagocytosis checkpoints as new targets for cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer. 19(10):568–586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Maute R, Xu J, Weissman IL. 2022. CD47-SIRPα-targeted therapeutics: status and prospects. Immunooncol Technol. 13:100070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jaiswal S, et al. 2009. CD47 is upregulated on circulating hematopoietic stem cells and leukemia cells to avoid phagocytosis. Cell. 138(2):271–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Majeti R, et al. 2009. CD47 is an adverse prognostic factor and therapeutic antibody target on human acute myeloid leukemia stem cells. Cell. 138(2):286–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Edris B, et al. 2012. Antibody therapy targeting the CD47 protein is effective in a model of aggressive metastatic leiomyosarcoma. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 109(17):6656–6661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Willingham SB, et al. 2012. The CD47-signal regulatory protein alpha (SIRPa) interaction is a therapeutic target for human solid tumors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 109(17):6662–6667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Brown EJ, Frazier WA. 2001. Integrin-associated protein (CD47) and its ligands. Trends Cell Biol. 11(3):130–135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Weiskopf K. 2017. Cancer immunotherapy targeting the CD47/SIRPα axis. Eur J Cancer. 76:100–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Chao MP, et al. 2010. Anti-CD47 antibody synergizes with rituximab to promote phagocytosis and eradicate non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Cell. 142(5):699–713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nishiga Y, et al. 2022. Radiotherapy in combination with CD47 blockade elicits a macrophage-mediated abscopal effect. Nat Cancer. 3(11):1351–1366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Banuelos A, et al. 2024. CXCR2 inhibition in G-MDSCs enhances CD47 blockade for melanoma tumor cell clearance. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 121(5):e2318534121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Vaccaro K, et al. 2024. Targeted therapies prime oncogene-driven lung cancers for macrophage-mediated destruction. J Clin Invest. 134(9):e169315. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Advani R, et al. 2018. CD47 blockade by Hu5F9-G4 and rituximab in non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. N Engl J Med. 379(18):1711–1721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sikic BI, et al. 2019. First-in-human, first-in-class phase I trial of the anti-CD47 antibody Hu5F9-G4 in patients with advanced cancers. J Clin Oncol. 37(12):946–953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kaur S, Cicalese KV, Bannerjee R, Roberts DD. 2020. Preclinical and clinical development of therapeutic antibodies targeting functions of CD47 in the tumor microenvironment. Antib Ther. 3(3):179–192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Drakaki A, et al. 2023. Atezolizumab plus magrolimab, niraparib, or tocilizumab versus atezolizumab monotherapy in platinum-refractory metastatic urothelial carcinoma: a phase Ib/II open-label, multicenter, randomized umbrella study (MORPHEUS urothelial carcinoma). Clin Cancer Res. 29(21):4373–4384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Crosbie EJ, et al. 2022. Endometrial cancer. Lancet. 399(10333):1412–1428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bogani G, et al. 2024. Adding immunotherapy to first-line treatment of advanced and metastatic endometrial cancer. Ann Oncol. 35(5):414–428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Daikoku T, et al. 2008. Conditional loss of uterine Pten unfailingly and rapidly induces endometrial cancer in mice. Cancer Res. 68(14):5619–5627. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Gerstberger S, Jiang Q, Ganesh K. 2023. Metastasis. Cell. 186(8):1564–1579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Alexander NJ, et al. 2004. Why consider vaginal drug administration? Fertil Steril. 82(1):1–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Noy R, Pollard JW. 2014. Tumor-associated macrophages: from mechanisms to therapy. Immunity. 41(1):49–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kohli K, Pillarisetty VG, Kim TS. 2022. Key chemokines direct migration of immune cells in solid tumors. Cancer Gene Ther. 29(1):10–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Chitu V, Stanley ER. 2006. Colony-stimulating factor-1 in immunity and inflammation. Curr Opin Immunol. 18(1):39–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Smith HO, et al. 2013. The clinical significance of inflammatory cytokines in primary cell culture in endometrial carcinoma. Mol Oncol. 7(1):41–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Oh MS, Chae YK. 2019. Deep and durable response with combination CTLA-4 and PD-1 blockade in mismatch repair (MMR)-proficient endometrial cancer. J Immunother. 42(2):51–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Green AK, Feinberg J, Makker V. 2020. A review of immune checkpoint blockade therapy in endometrial cancer. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 40:1–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Mills CD. 2012. M1 and M2 macrophages: oracles of health and disease. Crit Rev Immunol. 32(6):463–488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Ginhoux F, Schultze JL, Murray PJ, Ochando J, Biswas SK. 2016. New insights into the multidimensional concept of macrophage ontogeny, activation and function. Nat Immunol. 17(1):34–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu Y, et al. 2020. CD47 enhances cell viability and migration ability but inhibits apoptosis in endometrial carcinoma cells via the PI3K/Akt/mTOR signaling pathway. Front Oncol. 10:1525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Yang M, Jiang C, Li L, Xing H, Hong L. 2022. Expression of CD47 in endometrial cancer and its clinicopathological significance. J Oncol. 2022:7188972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Gu S, et al. 2018. CD47 blockade inhibits tumor progression through promoting phagocytosis of tumor cells by M2 polarized macrophages in endometrial cancer. J Immunol Res. 2018:6156757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Stirling ER, et al. 2022. Targeting the CD47/thrombospondin-1 signaling axis regulates immune cell bioenergetics in the tumor microenvironment to potentiate antitumor immune response. J Immunother Cancer. 10(11):e004712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Son J, et al. 2022. Inhibition of the CD47-SIRPα axis for cancer therapy: a systematic review and meta-analysis of emerging clinical data. Front Immunol. 13:1027235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Jin S. 2019. Bipotent stem cells support the cyclical regeneration of endometrial epithelium of the murine uterus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 116(14):6848–6857. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Jin S, Martinelli DC, Zheng X, Tessier-Lavigne M, Fan CM. 2015. Gas1 is a receptor for sonic hedgehog to repel enteric axons. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 112(1):E73–E80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. 2001. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) method. Methods. 25(4):402–408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cho N, Ko S, Shokeen M. 2021. Tissue biodistribution and tumor targeting of near-infrared labelled anti-CD38 antibody-drug conjugate in preclinical multiple myeloma. Oncotarget. 12(20):2039–2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Barkal AA, et al. 2019. CD24 signalling through macrophage Siglec-10 is a target for cancer immunotherapy. Nature. 572(7769):392–396. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Lesche R, et al. 2002. Cre/loxP-mediated inactivation of the murine Pten tumor suppressor gene. Genesis. 32(2):148–149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Soyal SM, et al. 2005. Cre-mediated recombination in cell lineages that express the progesterone receptor. Genesis. 41(2):58–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Radomsky ML, Whaley KJ, Cone RA, Saltzman WM. 1992. Controlled vaginal delivery of antibodies in the mouse. Biol Reprod. 47(1):133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the manuscript and supporting information.