Abstract

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species are essential components of diverse intracellular signaling pathways. In addition to their involvement in apoptosis, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species are crucial in the regulation of multiple developmental and physiological processes. This review aims to summarize their role in the regulation of key ovarian stages: ovulation, maturation and postovulatory ageing of the oocyte, and the formation and regression of the corpus luteum. At the cellular level, a mild increase in reactive oxygen and nitrogen species is associated with the initiation of a number of regulatory mechanisms, which might be suppressed by increased activity of the antioxidant system. Moreover, a mild increase in reactive oxygen and nitrogen species has been linked to the control of mitochondrial biogenesis and abundance in response to increased cellular energy demands. Thus, reactive oxygen and nitrogen species should also be perceived in terms of their positive role in cellular signaling. On the other hand, an uncontrolled increase in reactive oxygen species production or strong down-regulation of the antioxidant system results in oxidative stress and damage of cellular components associated with ovarian pathologies and ageing. Similarly, the disturbance of signaling functions of reactive nitrogen species caused by dysregulation of nitric oxide production by nitric oxide synthases in ovarian tissues interferes with the proper regulation of physiological processes in the ovary.

Keywords: ovarian regulation, corpus luteum, nitric oxide, oxidative stress, reactive nitrogen species, reactive oxygen species

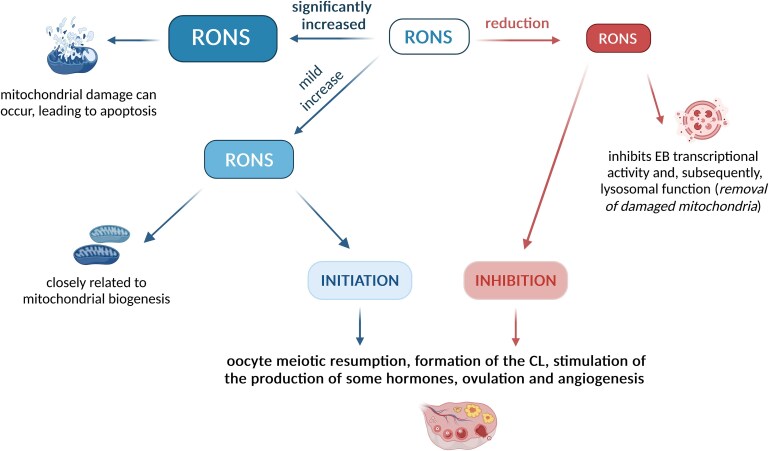

A mild and controlled increase of levels of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species is involved in the regulation of key ovarian stages: ovulation, maturation and postovulatory aging of the oocyte, and the formation and regression of the corpus luteum.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

Introduction: the role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in reproductive physiology

Understanding the complex signaling mechanisms regulating ovarian physiology, including luteotropic and luteolytic processes, is of great interest to cattle reproduction and production [1, 2]. In the case of the corpus luteum (CL), the research interest stems from the possibility of investigating cyclically recurring cellular processes associated with a number of important events in a short period of time. Specifically, these include intense cell division and angiogenesis at its origin, subsequent production of hormones and other signaling compounds, and the processes of apoptosis and necroptosis during CL regression [3, 4].

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species (RONS) are today recognized as crucial redox signaling and regulatory molecules involved in a wide range of developmental and physiological processes. In the field of animal reproduction, a wide range of processes involving ovarian activity may serve as an excellent example [5–7]. Among RONS, nitric oxide (NO) produced both by ovarian cells and vascular endothelium serves essential functions in the physiology and biology of the ovary, including regulation of folliculogenesis, ovulation, and embryo formation [8–14].

Often, physiological processes are very precisely defined by the relationship between site- and time-specific RONS production and activity of the antioxidant system, including local levels of low-molecular antioxidants [15–17]. Basically, there may be four scenarios: (1) a balance between RONS production and removal necessary for intracellular redox maintenance; (2) a controlled slight increase in RONS levels as a signal for the activation of some physiological processes; (3) a considerable predominance of RONS production over their removal associated with oxidative or nitrosative damage of biomolecules and consequent initiation of pathological states; and (4) a slight predominance of the antioxidant system over RONS production, resulting in decreased RONS levels and down-regulation of some processes [5, 18, 19].

The essential roles of RONS were uncovered in cyclically occurring physiological mechanisms, such as the formation and regression of the corpus luteum [20, 21], fluctuations in hormone levels [22, 23], and ovarian angiogenesis [24, 25]. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species participate as regulatory components in a number of physiological processes at different levels, including mitochondrial biogenesis and cell apoptosis [26–28]. However, uncontrolled upregulation of RONS levels results in long-term nitro-oxidative stress associated with ovarian aging [29].

Ovarian aging–associated disorders induced by the damaging effects of reactive oxygen species (ROS) are related to decreased female reproductive function. Long-term moderate oxidative damage has been postulated to mediate the observed decrease in follicle quality and progesterone (P4) production [30–34]. Moreover, in the case of specific processes, such as ovarian angiogenesis and apoptosis, new findings on ovarian physiology have found application to other research areas, such as cancer, where RONS, antioxidant protection, and their precisely balanced relationship play an important role [35–37]. During the initiation and advance of polycystic ovary syndrome, oxidative stress interferes with the development of ovarian follicles and disrupts normal follicular maturation. High ROS levels can damage oocytes and granulosa cells within the follicles, impairing their quality and compromising fertility [38].

Multiple past review articles in the field of reproduction focused mainly on the negative impacts of dysregulated levels of ROS and consequent oxidative stress on ovarian physiology and the development of pathological states. Moreover, the two tightly related groups of signaling molecules, ROS and reactive nitrogen species (RNS), were presented and discussed separately. In this review, we summarize current knowledge on the role of RONS in ovarian processes from the perspectives of both CL formation and development, including ovulation, maturation, postovulatory aging, angiogenesis, and P4 production, as well as structural and functional CL regression.

General characteristics of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species

RONS are small highly reactive molecules containing oxygen and/or nitrogen that interact with other intracellular molecules, resulting in their oxidative, nitrosative, and nitro-oxidative modification. They encompass both free radicals and non-radical species. The most biologically relevant ROS representatives are the superoxide anion radical (O2·−), hydroxyl radical (OH·), and hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), whereas nitric oxide (NO) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) radicals and peroxynitrite (ONOO−) are the most prominent RNS [39–41]. Highly reactive ROS are produced continuously as by-products of aerobic respiration in mitochondria, as well as generated by specific enzymatic and non-enzymatic reactions in other cell compartments [42]. Reactive nitrogen species are derived from nitric oxide (NO) produced from L-arginine by the action of nitric oxide synthases (NOSs) or alternatively in the nitrate/nitrite reduction pathway. A wide spectrum of chemical reactions of NO-derived radicals with the superoxide anion radical and other ROS results in the formation of peroxynitrite and further RONS species [43, 44].

RONS can play a dual role in the organism: at low levels, they are involved in a wide range of physiological processes, including cell signaling, regulation of metabolism, and programmed cell death. However, a localized RONS overproduction is often associated with immune defense responses, resulting not only in the killing of invading pathogens but also in damage of cellular components and tissues and the initiation of inflammatory processes [18, 45, 46]. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species overproduction also leads to nitro-oxidative stress due to an imbalance between the highly activated production of RONS and the ability of cells to scavenge them. Nitro-oxidative stress can also occur when the cellular systems of RONS degradation or removal are overwhelmed or impaired, resulting in an RONS accumulation that can damage cell components, including proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids [47]. It has been recognized that deleterious effects are mediated mainly by highly reactive secondary species (hydroxyl radical, peroxynitrite), produced upon reactions of primary RONS species such as superoxide and nitric oxide, and transition metals [48]. Nitro-oxidative stress in cattle is linked to reduced milk production and various diseases such as mastitis, lameness, and reproductive disorders [31, 42, 49–52].

Antioxidant protection of the organism is ensured by structurally diverse high- and low-molecular components, whose mutual interplay is essential for controlling cellular ROS levels [53, 54]. The key low-molecular antioxidants are glutathione, ascorbate, tocopherols, microelements (selenium, zinc), and other exogenous antioxidants such as ascorbate, carotenoids, and polyphenols. Superoxide dismutase, catalase, and glutathione peroxidase, together with peroxiredoxins and thioredoxins, are all essential high-molecular enzyme antioxidants.

The endocrine system also plays a significant role in responses to increased RONS production and conditions of oxidative stress. Some hormones can be active as direct antioxidants (melatonin, estrogen, P4, ghrelin); many can stimulate antioxidant enzymes mentioned above (e.g., melatonin stimulates superoxide dismutases [SODs], catalase, glutathione peroxidase, and others) or can promote the formation of RONS (corticosteroids and catecholamines). A controversial role has been found for testosterone, which may induce oxidative stress in some tissues and some situations but, in others, have an antioxidant role. Specifically, in cardiomyocytes, it remains unclear if the role of testosterone is prooxidant or antioxidant [55, 56]. In the specific case of thyroid hormones, reactive oxygen species are directly involved in the formation of thyroid hormones, but an imbalance between oxidants and antioxidants is associated with thyroid disease [57]. Some hormones (e.g., melatonin) regulate mitochondrial bioenergetic function and increase the efficiency of the electron transport chain, thereby reducing electron leakage [58]. The interrelationships between individual hormones of the endocrine system are also very important. As an example, ghrelin is not only a gastric hormone regulating food intake, gastrointestinal motility, and body weight but also involved in the regulation of male (and female) reproduction, e.g., in testosterone production, pituitary luteinizing hormone (LH) secretion, choriogonadotropin secretion, and general spermatogenesis. Moreover, ghrelin is also an efficient free radical scavenger [59]. A close relationship is evident between testosterone and estrogen, which are also significantly involved in redox pathways. Thus, the interrelationship between various hormones and the diverse effects of some hormones on oxidative stress brings interesting and important, but not completely understood, physiological regulations. Some growth factors, such as insulin-like growth factors (IGF1, IGF2), epidermal growth factor (EGF), and others, can also play an important role in protection against oxidative stress. From this viewpoint, Kurzawa et al. [60] reported positive effects of these growth factors on the reduction in the number of apoptotic cells and stimulation of embryo development in vitro.

Key advances in the field of RONS and their role as signaling and regulatory molecules have been made recently, and this has introduced new terms such as oxidative eustress, oxidative distress, and the concept of ROS-induced ROS release [61–64]. In general, the current evidence points to the importance of precise time- and site-specific control of RONS levels in physiological processes and its malfunction is involved in the initiation and progression of multiple pathologies.

Sources of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in ovarian tissues

Similar to other aerobic cells in animal tissues, the major source of ROS resides in side redox reactions within the respiratory chain located in the inner mitochondrial membrane. This is related to the capacity of the dioxygen molecule to accept one electron to form a superoxide anion radical. Specifically, the oxygen reduction to this ROS species occurs at the flavin domain of complex I or the semiquinol radical binding site at complex III. It is evident that greater intensity of redox reactions and electron transfer results in a higher rate of superoxide production in mitochondrial respiration [65]. Superoxide can be dismutated to hydrogen peroxide by mitochondrial or cytoplasmic SOD. A series of reactions known as Haber–Weiss and Fenton chemistry then results in the production of a hydroxyl radical, a highly reactive ROS species.

Besides mitochondrial respiration, cell membrane oxidases are another important ROS source in animal cells [66]. NADPH oxidases (NOXs) produce superoxide in the extracellular space using electrons transferred from the cytosol, whereas another group of homologous enzymes are called dual oxidases as they produce simultaneously superoxide and hydrogen peroxide [67, 68]. Interestingly, recent studies suggest that NOX-produced ROS in mature follicles might have an evolutionary conserved function in regulating follicle rupture and ovulation [69]. In addition, other redox reactions in the electron transfer chain localized in the endoplasmic reticulum, as well as the enzyme xanthine oxidase, can also contribute to ROS production [70, 71].

In the ovary of diverse animal species, multiple isozymes of NOS have been identified as sources of NO involved in the processes of steroidogenesis, folliculogenesis, and oocyte meiotic maturation [11, 72]. The tissue localization of specific NOS isoforms was found to be highly diverse among the studied animal species. In rats, the predominance of endothelial NOS (eNOS) is observed in mural granulosa cells, the theca layer, ovarian stroma, and ovarian blood vessels, whereas iNOS is found exclusively in somatic cells of antral follicles and luteal cells. In contrast, both eNOS and inducible NOS (iNOS) are expressed in mouse theca and granulosa cells, whereas eNOS is expressed in theca and granulosa cells, together with the surface epithelium and luteal cells of the bovine ovary [10]. In addition to species-dependent differences, a tissue-specific eNOS and iNOS expression pattern can vary depending on the stage of the estrous cycle [73]. It should be noted that besides ovarian cells, the ovarian vasculature and the resident or infiltrating macrophages also show capacity for NOS-dependent NO production [8]. Furthermore, in the blood vessel wall, NO is produced mainly via L-arginine-dependent eNOS activity. Moreover, it can also be produced by a non-enzymatical decomposition of S-nitrosothiols or reduction of circulating nitrates and nitrites [14].

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species production and mitochondrial biogenesis

This review shows the importance of RONS in controlling a number of ovarian processes at different cellular and organ levels. Overall, two basic situations in the interrelationship between RONS and antioxidant protection are well studied: the balance between RONS production and antioxidant protection, usually associated with a functioning healthy CL and P4 production or a significant increase in ROS associated with the apoptosis of ovarian cells. However, important cell signaling also occurs when this balance is even mildly disturbed, e.g., by a slight increase in RONS levels. This is associated with the upregulation of some physiological processes, whereas the opposite situation, under the predominance of antioxidant protection over RONS, may result in their suppression. A mild increase in RONS was shown to be associated with the initiation of oocyte meiotic resumption, formation of the CL, stimulation of the production of some hormones, ovulation, and angiogenesis, whereas, conversely, the predominance of antioxidants and active RONS scavenging results in the inhibition of these processes [6, 7, 21–23, 25, 35].

It appears that a mild increase in ROS is closely related to mitochondrial biogenesis—a self-renewal process induced in general by energy demand [74]. Mitochondrial biogenesis can be initiated by a number of signals, such as stress, temperature, hypoxia, and hormones [75, 76]. Exercise, high intensity or activity in general, has also been intensively studied as having significant effects on mitochondrial biogenesis and abundance [77]. Several proteins such as PGC1 alpha (peroxisome proliferator–activated receptor–gamma coactivator −1 alpha), NRF1/2 (nuclear respiratory factor), GABP (GA-binding protein), and PPAR (peroxisome proliferator–activated receptors) play a key role in mitochondrial biogenesis [75, 78, 79]. Oxidative stress related to RONS overproduction and expression of mitochondrial respiratory genes is also actively involved in mitochondrial biogenesis [28, 80].

The number and quality of mitochondria have been shown to be an important marker of oocyte and embryo quality. Thus, in pig oocytes, higher mitochondrial counts (250,000–350,000) have been recorded here than in other body cells. The importance of ROS for mitochondrial biogenesis is supported by the finding that the reduction in ROS levels in pig embryonal mitochondria is associated with decreased mitochondrial biogenesis [81]. Collectively, mild oxidative stress is a key factor in mitochondrial biogenesis, which provides a signal for an increase in mitochondria abundance and ultimately provides increased energy supply to the cells. At the same time, sufficient energy supply is crucial for the initiation of a number of key energy-demanding processes in the ovary, such as ovulation, oocyte maturation, and CL formation. However, when RONS are significantly increased, resulting in high oxidative stress, mitochondrial damage can occur, leading to apoptosis [80, 82, 83].

For this reason, the removal of damaged mitochondria via lysosomes, known as mitophagy [84, 85], is essential. Damaged mitochondria must first be tagged with the PTEN-induced kinase 1 (PINK1)–PARKIN protein complex [86]. This activates the transcription factor EB, which is crucial for lysosome biogenesis. Reactive oxygen species removal inhibits EB transcriptional activity and, subsequently, lysosomal function [87]. Further, the absence of EB is associated with fewer lysosomes and the accumulation of damaged mitochondria [88]. The role of lysosomes in the removal of damaged mitochondria is also supported by the observation of a higher occurrence of mitochondria–lysosomal colocalization in bovine oocytes following vitrification and warming [89]. Insufficient mitophagy, i.e., suppressed removal of damaged mitochondria, has been observed during multiple pathological events [84, 85].

The role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in the regulation of ovarian activity

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species participate in important ovarian processes like ovulation, CL formation, and development, including angiogenesis and hypoxia, oocyte maturation (the progression from prophase I to metaphase II), and postovulatory oocyte aging. The involvement of RONS in these physiological processes may be either direct or via other signaling proteins, such as hypoxia-inducible factor (HIF1 alpha) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF), which are described in the following sections.

Ovulation and the formation of the corpus luteum

Ovulation—the release of the egg from the Graafian follicle—is controlled by the LH, produced as the key ovulation regulator by the adenohypophysis. The LH triggers a cascade of reactions in follicle cells, involving activation of members of the EGF family, comprising amphiregulin, betacellulin, epiregulin, epigen, and others, which have similar functional and structural properties. The EGF network transmits the LH signal from follicle cells to the oocyte, initiating meiotic division and ovulation [90]. Furthermore, production of prostaglandins (mainly prostaglandin E2—PGE2) and RONS is increased. This signaling cascade ultimately results in the degradation of a part of the follicle wall, primarily by rupturing the basal lamina layer and subsequent release of the oocyte. The CL, as a transient endocrine gland, is then formed at the site of the ruptured follicle. The ovulation process is often compared to inflammation due to similar manifestations, which include increased leukocytes and ROS levels and increased production of certain cytokines and chemokines, as well as the final regenerative process [91]. In addition, ovulation can be suppressed by agents that inhibit inflammatory processes [91–93]. In this context, as early as 1993, Brännström et al. demonstrated that the contents of macrophages and neutrophil granulocytes in the medullary and thecal layer of the follicle were increased in the periovulatory period preceding ovulation, underlining the appropriateness of comparing ovulation to an inflammatory process [94].

Homozygous knock-out animals have often been used in in vivo experiments to determine the role of cellular antioxidant protection during ovulation. Mice lacking the Cu,ZnSOD gene showed reduced fertility, demonstrating a significant role of oxygen radicals in mammalian reproduction [95]. The inhibition of ROS production in the ovary by SOD, alone or in combination with catalase, is related to lower ovulatory efficiency [96]. Similarly, Shkolnik et al. [97] showed in an in vivo experiment in mice that increased activities of antioxidant enzymes, scavenging ROS, were associated with fewer ovulated oocytes, pointing to ROS as an important component of preovulatory signaling.

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species are also important activators and essential signaling components of the ovulation process. In this context, NO is reported to play a role in the ovulation process by regulating a number of factors, such as amphiregulin and epiregulin, and to be necessary for the preovulatory signaling cascade in bovine granulosa cells [21]. In relation to the latter, studies on the relationship of prostaglandins PGE2, PGF alpha, and NO in the regulation of ovarian physiology uncovered a highly complex cross-talk of their signaling pathways [98]. This study also showed that the inhibitory effects of NO on steroidogenesis, reported in previous studies, may be mediated by PGE2 and PGF alpha, possibly through the NO-dependent activated adenylate cyclase system and elevated AMP levels.

In the rabbit model, CL are temporary endocrine structures that secrete P4, essential for maintaining a healthy pregnancy. It is now clear that, besides the classical regulatory mechanism exerted by prostaglandin E2 (luteotropic) and prostaglandin F2 (luteolytic), a considerable number of other effectors assist in the regulation of CL [99]. Spontaneously ovulating mares showed increased production of follicular estradiol (E2) and NO concentrations from day 5 prior to ovulation, which was associated with vascularization of uterine blood flow [100]. Two peaks of increased NO were observed during the oestrous cycle in mares: the first peak during follicle development, followed by increased estradiol and ovarian blood flow, and the second one during the early development of CL associated with elevated uterine blood flow. Similarly, follicular E2 triggers NO production and subsequent dilatation of blood vessels by activating eNOS activity in ovulating ewes [101]. In contrast, synchronization of the oestrous cycle and ovulation using the Ovsynch method resulted in lower E2 and NO levels, which might be associated with decreased follicle and luteal vascularization [100]. On the other hand, the vasodilatory effects of circulating E2 were later suggested to be mediated by NO [102].

In summary, the current knowledge points to the essential role of ROS for ovulation, with their decreased levels leading to reduced ovulatory efficiency. On the contrary, increased antioxidant activity is associated with fewer ovulated oocytes, highlighting ROS importance in preovulatory signaling. In parallel, NO plays a crucial role in regulating ovulation factors and is necessary for preovulatory signaling in granulosa cells. Nitric oxide interacts with prostaglandins in complex ways to regulate ovarian physiology and follicular development.

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species’ role in the development and angiogenesis of the corpus luteum

The CL is formed on the ovary after the oocyte is released from the Graafian follicle. Its growth and development are associated with high demands for nutrients and oxygen supply [103]. Thus, the development of the CL is associated with the angiogenesis process, which consists of the rapid formation of new capillaries to ensure the supply of oxygen and nutrients. Angiogenesis has been studied not only in the context of CL formation but also in other physiological and pathophysiological processes, such as placental formation and carcinogenesis. VEGF alpha, fibroblast-growth factor 2, and HIF1 alpha factor are known main angiogenic factors in CL development. VEGF alpha, produced by endothelial cells and neutrophil granulocytes, is crucial for the expansion of the capillary network during CL angiogenesis. Blockade of VEGF alpha results in defective CL development and reduced P4 production in primates, cows, and other species [104]. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species also play an important role in this process, as VEGF alpha activity is stimulated by ROS as well as HIF1 alpha and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) alpha [25, 105]. In particular, Gonzalez-Pacheco et al. [24] reported that mild oxidative stress, induced by H2O2, stimulated the expression of VEGF alpha and vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 2 (VEGFR2) genes. Similarly, activation of endothelial cells by H2O2 treatment resulted in VEGF production in mouse heart endothelial cells [106]. Interestingly, cultured bovine luteal endothelial cells treated with TNF alpha and interferon gamma, showed increased NO production, whereas decreased NO production occurred when endothelial cells were treated with P4 [107].

The recognition that angiogenesis and hypoxia are closely intertwined processes and that RONS play a crucial role in their control has been demonstrated in a number of in vivo and in vitro experiments. Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha functions as a general sensor of oxygen deprivation in cells as its levels increase in the absence of oxygen. Under normoxic conditions, HIF1 alpha is hydroxylated by prolyl hydroxylases (PHD) in an oxygen-dependent process followed by ubiquitination and subsequent degradation of HIF in the proteasome. Under oxygen deprivation and hypoxic conditions, PHD is inactive, and this decreases the rate of HIF1 alpha ubiquitination, and the concentration of HIF1 alpha in the cell cytosol remains high. Hypoxia-induced HIF activates genes related to angiogenesis, erythropoiesis, glycolysis, etc. Recent studies show that HIF levels can also be regulated by other signaling pathways involving RONS, heat shock proteins (namely, HSP70 and HSP90), and other signaling proteins [108, 109].

Hypoxia-inducible factor 1 alpha has an important role in activating VEGF alpha and the control of angiogenesis. When comparing the concentration of HIF1 alpha in the CL at the time of its growth and the subsequent period of full CL function, the highest concentrations of HIF1 alpha are, as expected, observed at the beginning of CL development. The response to oxygen deficiency and increased HIF1 alpha is diverse, e.g., activation of VEGF followed by angiogenesis, activation of glycolytic enzymes and glucose GLUT transporters, etc. Interestingly, several studies have shown that ROS are also involved in HIF1 alpha activation [110–112]. Bonello et al. [110] reported that higher ROS levels can activate nuclear factor (NF) kappa B transcription factor, which results in higher transcription of the HIF1 alpha gene. In this context, the authors also conclude that there are no “absolute” ROS levels with specific effects on HIF1 alpha but rather an alteration toward an antioxidant or pro-oxidant state, which can affect HIF1 alpha levels. In general, ROS appear to be essential signaling molecules for activating various growth factors like TNF alpha and VEGF alpha, which initiate angiogenesis within the CL. In contrast, increased ROS production during the luteal phase after ovulation leads to oxidative stress and pathological conditions.

As HIF1 alpha is sensitive to changes in oxygen availability at the cellular level, it directly or indirectly controls ROS levels, which impacts multiple reproductive processes. Lower oxygen availability due to higher altitude can occur partially at the tissue or cellular level and at the level of the whole organism. This is because higher altitude is associated with a decrease in partial oxygen pressure and lower oxygen saturation of arterial blood. Experiments carried out at higher altitudes have contributed to completing our knowledge of the relationship between oxygen-related regulators (HIF1 alpha, VEGF alpha, ROS) and reproduction. In sheep exposed to high altitude, the development and functioning of the CL were negatively affected, whereas HIF1 alpha and VEGF levels, as well as higher serum malondialdehyde concentrations, were increased [113]. On the other hand, no changes in total plasma antioxidant capacity were observed. Thus, a number of studies have shown that hypoxia at the cellular, organ, or whole organism levels is associated with reproductive problems and that RONS are important components of associated signaling pathways [110, 113, 114].

Collectively, ROS play a vital role in activating HIF1 alpha, which controls VEGF alpha, which is crucial for capillary network expansion during CL angiogenesis and in response to hypoxia. While ROS are essential for initiating angiogenesis in CL development, excessive ROS production during the luteal phase can lead to oxidative stress and pathological conditions. Limited knowledge has been obtained so far on the role of NO. The available data point to its production in luteal endothelial cells increased by TNF alpha and interferon gamma, but decreased by P4.

Functional corpus luteum and progesterone production

The CL is a small temporary endocrine gland evolving from the ovulated ovarian follicle. The main function of the CL is the production of P4 in order to maintain the endometrium and regulate the reproduction cycle, particularly pregnancy. However, apart from P4, the cells of CL are an important source of many other signal substances. These include other hormones (luteal oxytocin, estradiol), cytokines, and growth factors (VEGF, TNF, and many others), which are involved in endocrine, autocrine, and paracrine signaling, including both crucial processes in CL itself—luteinization and luteolysis [4, 115–117]. The involvement of these signal substances is, in many cases, not only local. An example is luteal oxytocin production, which is one of several non-neural sources of oxytocin in the organism. Thus, CL is not only a P4 producer, but P4 also remains its typical product.

The cells of the CL can be divided into steroidogenic (capable of producing P4) and non-steroidogenic (endothelial and immune cells, pericytes, and others). The steroidogenic cells are further divided according to size into small luteal cells derived from the theca cells and large luteal cells derived from granulosa cells. Importantly, large luteal cells are crucial for P4 production as they produce up to 30 times more P4 than small cells [118]. Reactive oxygen species also play a vital role in P4 production [36, 119]. Progesterone is produced in the CL from cholesterol, which is supplied externally. Cholesterol is transported across the outer mitochondrial membrane to the inner membrane by the steroidogenic acute regulatory protein (StAR), and, here, it is converted into pregnenolone by the action of cytochrome P450-dependent cholesterol side-chain cleavage enzyme (P450scc). Pregnenolone is processed to form P4 in the smooth endoplasmic reticulum by 3-beta-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3-betaHSD). Thus, the three proteins StAR, P450scc, and 3-betaHSD are crucial to P4 production [120, 121]. Nitric oxide was shown to suppress the activity of these proteins (e.g., via reduced or even abolished P4 production [122, 123]). Nitric oxide causes a dose-dependent decrease of P4 in human granulosa cells [124]. Nitric oxide produced by NO synthase present in human granulosa-luteal cells inhibits estradiol secretion by direct inhibitory action on P450 aromatase independent of cyclic guanosine monophosphate (cGMP) signaling. Similarly, NO was shown to inhibit steroidogenesis via a cGMP-independent process by inhibiting P450 aromatase activity in porcine granulosa cells [125]. However, NO observed to inhibit steroidogenesis in cultured rat granulosa cells might be produced by macrophages invading the ovary during the periovulatory period or alternatively from the endothelium of ovarian blood vessels [126].

The regulatory effects of NO on CL secretory functions were further uncovered using separate cultures of small luteal (SLC) or large luteal (LLC) cells. In mixed culture with endothelial cells, treatment by an NO donor decreased P4 and OT secretion and increased production of prostaglandin F2-alpha and LTC4, while treatment with an NOS inhibitor showed the opposite effects. However, these effects of NO modulators were not observed in pure cultures of either SLC or LLC cells. Collectively, this suggests that the full secretory response of the CL to NO is dependent on the presence of endothelial cells and cell-to-cell communication within CL cells [127].

P4 production is also controlled by ROS via SOD1 activity [23]. Increased ROS production in SOD1-deficient female mice is associated with decreased P4 production in the ovaries and an increased number of apoptotic cells in the CL. The luteotropic hormone prolactin, as well as placental lactogens, activate the antioxidant system in rat CL through upregulation of the expression of Cu,ZnSOD, and MnSOD genes, and this may be highly germane in the maintenance of CL integrity and its steroidogenic capacity [128].

It can be summarized that ROS play a vital role in P4 production mediated by modulation of SOD1 activity. Superoxide dismutase 1 deficiency results in decreased P4 production and increased apoptosis in the CL. Nitric oxide inhibits steroidogenesis in granulosa cells through various mechanisms, including direct inhibition of P450 aromatase activity and suppression of key proteins (StAR, P450scc, 3-betaHSD) crucial for P4 synthesis. It seems that the full secretory response of the CL to NO depends on the presence of endothelial cells and cell-to-cell communication.

Oocyte maturation and postovulatory aging

Oocyte maturation means the restart of meiotic division and its further development from the arrested diplotene stage of prophase I to metaphase II. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species have been suggested to play an important role in this process, although the bulk of the data in this area are obtained in vitro. The formation of intracellular ROS in oocytes can be revealed by fluorescent assay using a specific CellROX reagent. Aggregates of ROS in fresh and vitrified oocytes are labeled by a green signal (Figure 1A and B).

Figure 1.

ROS fluorescent staining in bovine oocytes. (A) ROS in fresh IVM oocytes; (B) ROS in oocytes after vitrification (photo: Dujíčkova L.). The intracellular ROS was assessed by fluorescent staining using the fluorescent reagent CellROX Green (Invitrogen, Massachusetts, USA). Denuded oocytes were incubated in a dye mixture (according to the manufacturer) for 30 min at 37°C, washed in PBS-PVP solution (phosphate-buffered saline with 0.6% polyvinylpyrrolidone), fixed in 4% formalin for 10 min, and mounted onto a sandwich of glass slide and a coverslip. Stained oocytes were scanned by an LSM 700 Zeiss confocal laser scanning microscope.

Nitric oxide produced by eNOS is a key modulator of oocyte maturation and oocyte development in vitro [129]. Moderately elevated ROS (particularly H2O2 in rat ovaries) are important for the meiotic development of oocytes and their maturation from the arrested diplotene stage of prophase I [130]. Increasing antioxidant capacity was detrimental to nuclear maturation, embryonic cleavage, and blastocyst development in oocyte culture [131]. Thus, balanced concentrations of antioxidants are of utmost importance for the preparation of in vitro maturation (IVM) media. Supplementation of different antioxidants in IVM media, e.g., glutathione [132], melatonin [133], and retinoids [134, 135], has been studied. Research on retinoids in IVM media showed that a certain optimal concentration of retinoic acid (RA) is required, whereas high RA levels are associated with deteriorated maturation as well as adverse embryonic development [134, 135]. Almiñana et al. [134] reported that the addition of 5 nM RA to porcine IVM medium increased blastocyst formation. On the other hand, supplementation of porcine IVM medium with 500 nM RA caused decreased oocyte maturation rates. Similar findings were also reported for bovine embryos, where positive effects of low RA concentration compared to toxic effects of high RA levels were reported [135].

Thus, the importance of RONS for oocyte meiotic resumption has been demonstrated in a number of studies, whereas increased ROS levels are associated with termination of the meiotic cycle and initiation of apoptosis [136–138]. After ovulation, the oocyte is either fertilized or transformed by postovulatory aging and finally removed by apoptosis. Postovulatory aging and subsequent oocyte apoptosis are separate and complex processes involving a number of signaling pathways as well as morphological changes of the oocyte, such as hardening of the zona pellucida [139] and abnormal release of cortical granules [140]. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species signaling and oxidative stress are important regulatory components in both processes [136, 140]. Postovulatory aging of oocytes, distinct from reproductive aging caused by advanced age, is a natural process preceding oocyte apoptosis.

One of the main factors in postovulatory oocyte aging is the increase of RONS levels and decreased activity of the antioxidant system. Postovulatory aging of porcine oocytes is induced by oxidative stress and associated with subsequent changes in molecular and cellular levels, such as increased membrane fragmentation and disrupted organelle structures [140]. Reactive oxygen species, namely, O2•-, H2O2, and HOCl, were found to be involved in the postovulatory aging of oocytes, particularly in the regulation of optimal time of fertilization [141]. For this reason, some studies focused on improving the quality of aged oocytes by increasing antioxidant protection. Postovulatory aged mice oocytes and their elevated levels of superoxide could be improved by supplementation of coenzyme Q10 [142]. Apoptosis in pseudopregnant rabbit ovaries was significantly increased in L-NAME-perfused CL [143].

In sum, RONS are involved in several physiological processes at the ovarian level and are an important part of cellular signaling (Figure 2). Increased ROS levels are associated with the termination of the meiotic cycle and the initiation of apoptosis in oocytes. Moderately elevated ROS (particularly H2O2) are important for the meiotic development of oocytes, whereas postovulatory oocyte aging is characterized by increased RONS levels and decreased antioxidant activity, leading to oxidative stress and cellular changes. Moreover, NO produced by eNOS is a key modulator of oocyte maturation. From a practical point of view, balanced concentrations of antioxidants are crucial in IVM media, with both insufficient and excessive levels potentially detrimental to oocyte development (Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Overview of ROS/RNS production and their signaling roles during ovarian physiological activity (Created with BioRender.com). CoQ, coenzyme Q; FR, Fenton reaction; XO, xanthine oxidase

Figure 3.

Overview of effects of modulation of ROS/RNS levels on molecular and physiological processes in different stages of the ovarian cycle (Created with BioRender.com).

The role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in corpus luteum regression

In the CL, two opposing signals occur over a short period of time during the ovarian cycle: first, luteotrophic, which generates and maintains CL, and then luteolytic, which is associated with its regression. The CL in animal models and humans is an issue of cyclical modifications that change its function and size in a very short time. Endothelial cells and blood vessels play key roles in bovine CL function; therefore, NO, as a vasoactive regulator, is expected to be intimately involved in the local regulation of luteolysis [144]. Nitric oxide is produced by all three main types of bovine CL cells: steroidogenic, endothelial, and immune cells. Prostaglandin F2 (PGF2) alpha and some luteolytic cytokines (TNF alpha, interferon) increase NO production and stimulate NOS expression in bovine CL. Nitric oxide inhibits P4 production, stimulates the secretion of PGF2 alpha and leukotriene C4, reduces the number of viable luteal cells, and participates in functional luteolysis. NO induces the apoptotic death of CL cells by modulating Bcl2 family gene expression and stimulating caspase-3 gene expression and activity. However, this simple molecule shows both luteolytic and luteotropic actions during the estrous cycle in ruminants, and discrepant data have been published on the involvement of NO in luteolysis [145]. NO was found to be involved in luteolysis by mediating the action of PGF2 alpha [146–148]. Nitric oxide was suggested to have indirect antiluteolytic effects by increasing PGE2 secretion from luteal tissue [149]. However, another study observed the luteolytic effect of NO as a treatment with NO donor decreased P4 secretion from the luteal cells and their increased apoptosis upon treatment [150].

Recent studies on late pregnancy in rats indicate that ovarian physiology and CL regression are regulated by NO produced in the coeliac ganglion [151]. Decreased production of NO and of gonadotropin-releasing hormone was observed after the application of the NOS inhibitor L-NAME in the coeliac ganglion compartment. This resulted in an increased production of P4 and estradiol in ovarian tissue, which was associated with an up-regulation of biosynthetic enzymes, 3-betaHSD, and P450 aromatase. Decreased NO levels by L-NAME also reduced apoptotic activity and lipid peroxidation, whereas it augmented the total antioxidant capacity of CL.

In pathological cases, the CL may persist as a so-called persistent CL. This occurs when the endometrium produces insufficient prostaglandin PGF2 alpha. In livestock, especially in cattle, this occurs, for example, with endometrial inflammation [152, 153].

Regression of corpus luteum is initiated by an increase in PGF2 alpha and reactive oxygen and nitrogen species

Adequate antioxidant protection is essential for a functional CL, which is provided both enzymatically and non-enzymatically. Superoxide dismutase 1 was reported as an important enzyme of antioxidant protection in the CL [154]. In cattle, the highest SOD and catalase activity was observed until day 16 of the estrous cycle and then decreased during the demise of CL. Moreover, SOD activity correlates with plasma P4 levels in CL [155].

Peroxiredoxins are key components of antioxidant defense that participate in the highly efficient removal of hydrogen peroxide in multiple cell compartments [156, 157]. Peroxiredoxin (PRDX) 1 was found to be important for the maintenance of luteal function, and PRDX1 deficiency is associated with decreased P4 production [158]. Furthermore, PRDX2 deficiency plays a major role in luteal regression induced by PGF2 alpha [159]. During ovarian aging, a decrease in antioxidant protection provided by PRDX4 with increasing age has been demonstrated both in mice and human ovaries [160]. Peroxiredoxin 4 may also prevent apoptosis induced by RONS in cumulus cells [160]. Efficient antioxidant protection is vital for a functional CL, as demonstrated in a number of animals and humans [154, 155, 161–164]. Significant increases in RONS production, in parallel with decreased antioxidant protection, are essential processes in CL regression. Early studies uncovered that H2O2 production occurs in luteal tissue during CL regression in superovulated rats [165]. Similarly, PGF stimulates H2O2 production in cultured bovine luteal cells [154].

From the viewpoint of hormonal control, the initiation of PGF2 alpha production and the termination of P4 production are the basic characteristics of luteolysis and the regression of the CL. The production of PGF2 alpha is controlled by signaling molecules such as TNF alpha, interferon gamma, and NO. PGF2 alpha receptors are expressed in the aforementioned small and large luteal cells. Mice lacking the PGF2 alpha receptor gene were pregnant and had normal pregnancy development. However, they were unable to luteolyze CL and subsequently initiate birth at term [166]. This study demonstrated the crucial role of PGF2 alpha in inducing luteolysis in mice. It is noteworthy that the uterus is the dominant origin of luteolytic PGF2 alpha, but, in some species, the corpus luteum also produces PGF2 alpha and PGF2 alpha of luteal origin is significantly involved in the luteolysis. Thus, PGF2 alpha is not only produced by the endometrium, but, in many animal species, its production by the CL has been shown to enhance the luteolytic effect. The CL produces prostaglandins in rodents, rabbits, pigs, sheep, cows, horses, and humans [167]. The initiation of prostaglandin production in the CL occurs variously, including by external PGF2 alpha [4, 168], cytokines, TNF alpha [169], and other signal components [167]. Activation of luteal PGF2 alpha production occurs by PGF2 alpha–dependent activation of the prostaglandin-endoperoxide synthase 2 (PTGS2) gene, coding the key enzyme for prostaglandin synthesis—cyclooxygenases COX2. In pseudopregnant rats, the regulation of PTGS2 expression is regulated by the transcription factor NF kappa B via ROS-dependent pathways [168]. Administration of catalase and SOD prevented the increase of NF kappa B p65 protein levels and PTGS2 gene expression induced by PGF2 alpha [168]. Thus, elevated ROS are important for activating the whole process of luteal PGF2 alpha production and the overall luteolytic effect.

Functional and structural regression of the corpus luteum

In general, regression of the CL is divided into two related processes: functional regression and structural regression [103]. Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species play a major role in both processes [22, 170, 171]. Functional regression of CL is associated with loss of P4 production. Oxytocin treatment, known to enhance PGF2 alpha synthesis in uterine and ovarian tissues during the CL regression, induced NOS activity and NO levels in ovarian but not in the uterine tissue during the luteolytic phase in the rat [172]. Subsequent studies on rats indicated that NO was involved in luteolysis by modulating PGF2 alpha and P4 production [173]. Elevated RONS levels, particularly NO levels increased by NOS activity, are important contributors to the termination of P4 production [22]. Treatment with NO donor S-nitrosopenicillamine in bovine luteal cells caused decreased mRNA and protein levels of StAR, 3-betaHSD, and P450scc [121]. In particular, through increased levels of NO, cholesterol transport into the mitochondria by the StAR protein is stopped. Similarly, the production of two other proteins (P450scc; 3-betaHSD) essential in P4 production is also suppressed through NO, leading to an overall loss of P4 production and, thus, to functional regression of the CL.

The fundamental process that leads to luteolysis is mediated by NOS-produced NO, which initiates PGF2 alpha production in the CL [22]. The NO-NOS system is also a mediator of lipid peroxidation in CL induced in rats by PGF2 alpha [171]. Nitric oxide is involved both in functional and structural luteolyses as a component of an autocrine/paracrine luteolytic cascade induced by PGF2 alpha [174]. A number of other processes are involved in the increase in RONS during luteolysis. For example, Foyouzi et al. [175] proposed that PGF2 alpha reduces the expression of proteins, which participate in RONS radical scavenging.

The structural regression of the CL is also controlled by the process of cell death. For a long time, apoptosis mediated by activation of caspases was the main type of cell death in the CL. However, recent studies suggest that CL death also occurs independently of caspases by the process of necroptosis involving protein kinases [170, 176]. In these processes of structural regression of the CL, the influence of RONS is well known and accepted. In general, the regression of CL is significantly associated not only with an increase in ROS and oxidative stress [20, 165] but also with an increase in HIF1 alpha [20, 177]. Tang et al. [20] demonstrated that HIF1 alpha (specifically the HIF1 alpha/BNIP3 signaling pathway associated with autophagy and apoptosis) is also involved in CL regression. The authors report that both HIF1 alpha and BNIP3 levels were increased during luteal regression. They also demonstrated increased ROS levels during luteal regression and, thus, the importance of oxidative stress for luteolysis [20]. Under in vitro conditions, Nishimura et al. [177] demonstrated in culturing bovine luteal cells that reduced oxygen is associated with reduced P4 production (with low P450scc expression). This indicates a major effect of oxygen deficiency on luteolysis in cattle [177].

Nitric oxide can be considered among the main factors controlling the luteolytic cascade in various animal species and humans [122, 123, 148, 178, 179]. Nitric oxide was identified as the main mediator of increased luteal blood flow during the early stage of luteolysis in cows [180]. Nitric oxide produced by eNOS activated by luteolytic PGF2 alpha induces a profound increase in luteal blood flow [181]. It should be noted that contrasting results were reported on the ovine oestrous cycle, where NO acted as an antiluteolytic factor preventing luteolysis by altering the PGE:PGF2 alpha ratio secreted by the uterus [149, 182].

In general, there is a mild predominance of antioxidants over RONS in the CL during its period of full activity. This is a significant regulation that is tightly controlled. The action of prostaglandin will shift this balance in the direction of an increase in some RONS. Blocking of the antioxidant system (i.e., Cu,ZnSOD) in the CL leads to increased RONS levels and termination of P4 production, followed by an increased apoptosis in the CL. Progesterone production is also stopped by a reduction in oxygen during luteolysis and reduced expression of P450scc in mitochondria [177] or by increased NO production, which stops P4 production while stimulating the CL to produce PGF2 alpha.

Thus, the role of RONS in the regression of the CL is highly significant and multifaceted. Elevated RONS, particularly NO, contribute to functional CL regression by decreasing P4 production through suppression of key proteins (StAR, P450scc, 3β-HSD). Nitric oxide initiates PGF2 alpha production in the CL, mediating lipid peroxidation and acting as a component of the luteolytic cascade. Structural regression of the CL involves increased ROS and HIF1 alpha levels, contributing to oxidative stress and activating pathways associated with autophagy and apoptosis. Nitric oxide is a main factor controlling luteolysis, influencing luteal blood flow, though its role may be variable across species and deserves further investigation.

The role of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in ovarian aging and pathologies

In this review, we provide compelling evidence that ROS play an indispensable role in various physiological activities of the ovary by mediating intracellular redox signaling and homeostasis. However, as mentioned in previous chapters, the imbalance between ROS production and the activity of components of the antioxidant system contributes to the development of age-related ovarian dysfunction and diverse ovarian pathologies. It should be noted that most of our current knowledge of the mechanisms and therapeutical strategies originates from human studies. Research reports and clinical studies on animal ovarian diseases are rare, and the practical treatment approaches are mostly limited to surgical interventions, with some exceptions like dogs (see, e.g., [183]). However, suitable animal models that include the cellular and molecular mechanisms involved in the tumor initiation and progression might facilitate the development of improved methods for early detection and treatment, such as in the case of ovarian cancer (OC) [184].

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in ovarian aging

Reproductive longevity is determined by the age-associated decline in ovarian functions, characterized by tissue-specific features such as a drop in hormone production, decreased oocyte quality, and accumulation of senescent cells [185–187]. Multiple endogenous and environmental factors contribute to these processes as a part of biological aging, including disturbance of RONS-dependent redox signaling and regulations as well as accumulated nitro-oxidative damage to cellular components [5, 188]. The oxidative processes are tightly linked both to increased ROS production associated with mitochondrial dysfunction and damage and a decline in the efficiency of the antioxidant system, particularly decreased ROS scavenging and repair of oxidative modifications of DNA and proteins, as well as defects in proteasome and autophagy system for damaged proteins [33, 189].

Similarly to other age-related processes, multiple studies identified the key role of the NRF2/KEAP1 signaling in the regulation of antioxidant responses under oxidative stress and thus with a major role in ovarian aging [30, 34]. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2) is an important transcription factor of the oxidative stress response, whose regulation is mediated by its endogenous regulator, the Kelch-like ECH-associated protein 1 (KEAP1) ([190, 191]; Belleza et al., 2018). Under oxidative conditions, NRF2 is released from KEAP1 and translocates to the nucleus, where it forms a heterodimer with small MAF proteins. The NRF2/MAF dimer then binds to the so-called antioxidant response elements (AREs) located in the regulatory regions of NRF2 target genes. These results in transcriptional activation of antioxidant enzymes such as catalase, superoxide dismutase, peroxiredoxins, glutathione S-transferases, NADP(H) quinone dehydrogenases, and heme oxygenase [29, 33, 192]. Other intracellular factors were uncovered to influence NRF2 signal transduction, including NRF2 protein stability, phosphorylation, nuclear export, and ARE binding [34]. Moreover, the KEAP1/NRF2 pathway has been suggested to interact with other signaling pathways involving phosphatidylinositol 3-kinases (PI3K), extracellular signal-regulated kinases (ERK), mitogen-activated protein (MAPK), and mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) pathway. However, the current knowledge of the cross-talk of NRF2 pathways with these complex regulatory networks within antioxidant responses of ovarian cells is still very limited.

The involvement of NRF2 signaling has been detailedly characterized in age-related ovarian aging as well as in aging triggered by xenobiotics, pollutants, and unhealthy lifestyles (for a review, see, e.g., [29]). The expression of NRF2 and KEAP1 proteins is observed mainly in the cytosol of granulosa cells; however, a number of exosomes bearing Nrf2-encoded mRNA are released by granulosa cells and internalized by surrounding cells to enhance the extent of antioxidant response within ovarian tissues. The NRF2 expression levels decline with advancing age in both granulosa cells and oocytes [193]. Inflammatory processes in aging ovaries were also reported to be mediated by iron accumulation and NF kappa B-dependent activation of iNOS, resulting in subsequent down-regulation of NRF2 signaling, decreased activity of glutathione peroxidase 4 and increased oxidative stress in granulosa cells [194]. Collectively, NRF2, as the master regulator of the expression of antioxidant genes, has a vital function in both age-related and pathological ovarian aging. Further insights into the molecular mechanisms of NRF2 regulation in ovarian cells might contribute to the search for therapeutic strategies to reduce oxidative stress, delay the progression of ovarian aging, and prolong healthy female reproductive functions.

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in polycystic ovary syndrome

Polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS) belongs to endocrine disorders of heterogenous origin, highly prevalent in women of reproductive age and associated with dysfunctional ovaries, increased androgens, and insulin resistance [195, 196]. Oxidative stress plays an important role in PCOS pathophysiology and regulates the occurrence and development of this disease together with other pathogenic factors [38, 197, 198]. Several mechanisms have been shown to contribute to increased ROS production in PCOS patients. Dysfunctional mitochondria generate higher ROS amounts within the electron transport chain, whereas induced activity of membrane NADPH oxidase amplifies ROS production and sustains the inflammatory state observed in PCOS. The close proximity of mitochondrial DNA to the site of ROS overproduction and low antioxidant protection in mitochondria facilitates an increased rate of mtDNA mutations, which, in turn, can lead to impaired oxidative phosphorylation, lower ATP production, and induced ROS formation, contributing to the metabolic and hormonal dysregulations observed in PCOS. Reactive oxygen species–mediated damage to cell components such as lipids, proteins, and nucleic acid is evident from increased values of markers of oxidative stress such as malondialdehyde, glycated proteins, or 8-hydroxyguanine [38, 197, 199]. Polycystic ovary syndrome cases have also been connected with reduced antioxidant defenses, resulting in an imbalance between ROS production and the antioxidant system and, consequently, cellular oxidative stress. A highly oxidized state can promote the proliferation of theca-interstitial cells, reduce the secretion of serum sex hormones, increase androgen secretion, and cause hyperandrogenemia [197]. Excess androgens further disrupt redox balance by affecting the expression and activities of cellular pro-oxidant and antioxidant enzyme systems. Increased ROS activate the nuclear factor-kappa B, which affects the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines like TNF-α and IL-6 [36]. Oxidative stress also activates a specific subset of protein kinases that trigger serine/threonine phosphorylation instead of normal tyrosine phosphorylation of insulin receptor substrate, resulting in the inhibition of insulin signaling and the development of insulin resistance typically observed in PCOS [198]. Furthermore, the follicular fluid in PCOS patients was observed to generate excessive ROS levels, leading to mitochondrial damage and subsequent degradation of oocytes during meiosis and causing follicular apoptosis [197, 199]. Diverse antioxidants, such as tocopherols, alpha-lipoic acid, and N-acetyl cysteine, have been proposed as potential therapeutics to decrease oxidative stress and improve metabolic and reproductive outcomes in women with PCOS.

On the other hand, PCOS has been generally found to be associated with impaired mechanisms of NO production and regulation and decreased NO levels [200]. An early study reported a negative association between plasma nitrite, as a marker of endothelium-derived NO, and insulin resistance in PCOS patients [201]. Decreased NO levels are found in women with PCOS, suggesting that NO deficiency in the follicular microenvironment may have substantial impacts on the development of oocytes in PCO [202]. This is in accordance with the outcomes of a meta-analysis of studies on PCOS patients, which found a significant association between PCOS and serum or plasma nitrite levels, suggesting endothelial dysfunction associated with decreased NO production [203].

Several mechanisms have been proposed to contribute to observed disturbances in NO production and signaling. Asymmetric dimethylarginine (ADMA), an endogenous competitive inhibitor of NOS, is likely involved in decreased NO production and, hence, PCOS pathogenesis [204]. The binding of ADMA to the L-arginine substrate site on NOS protein causes the enzyme uncoupling, which results in the production of superoxide by NOS instead of NO. Increased plasma ADMA levels, together with decreased glutathione peroxidase, are observed in PCOS patients [205]. The underlying molecular mechanisms might be associated with a decreased expression and activity of the key ADMA-degrading enzyme dimethylarginine dimethylaminohydrolase 1 (DDAH1). Modulations of DDAH 1 activity are known to interfere with the regulation of NO levels by increasing or decreasing ADMA [206]. The accumulated evidence thus demonstrates the involvement of elevated ADMA levels in redox imbalances during PCOS. A recent study on the ovarian granulosa cell line reported that the overexpression of the DDAH1 gene resulted in lower ADMA levels, decreased oxidative stress, and increased cell viability; in contrast, opposite effects were found in DDAH1 knockdown cells. The authors concluded that strategies for increasing DDAH1 activity in ovarian cells could represent a novel approach to PCOS treatments [207].

Furthermore, the increased activity of arginase, an enzyme competing for NOS substrate L-arginine, might be another factor contributing to alterations of NO metabolism described in PCOS [208]. However, the putative involvement of arginase in the regulation of NO levels in ovarian tissues and in PCOS pathogenesis is poorly understood. Higher levels of arginase-bearing platelet-derived microparticles contribute to the alteration of the arginine metabolism in PCOS patients; moreover, arginine levels might represent an early biomarker of cardiovascular pathologies in PCOS patients [209]. Collectively, decreased NO concentration resulting from combined effects of down-regulation of NOS expression, increased ADMA production, and limited arginine bioavailability play an important role in PCOS etiology [200, 202].

Reactive oxygen and nitrogen species in ovarian cancer

Ovarian cancer (OC) belongs to the most common cancers in women and is known for the lowest survival rates and the worst prognosis among gynecologic malignancies [210]. Reactive oxygen species play a vital role in the activation of several signaling pathways leading to cell proliferation and growth in OC tumorigenesis [211]. ROS plays a crucial role in the pathogenesis and neoangiogenesis of OC by inducing modifications in the phenotype of tumor cells via interaction between tumor cells and the neighboring stroma [212].

Induced ROS production activates the ERK1/2 MAPK and the AKT signaling pathways, which promote cell proliferation during OC initiation and progression [213, 214]. In contrast to the previous hypothesis on the decisive role of mitochondria-derived ROS production, studies on OC cell lines uncovered a key contribution of the upregulation of NADPH oxidase subunit NOX4 in increased ROS production, involved in tumor growth and angiogenesis [215]. Interestingly, increased activity of NOX4 positively correlated with TGF-beta 1 and NF-kappa B activity, which was suppressed by the application of their inhibitors. It should be noted that oxidative stress conditions are generally known to activate pathways of cell death, such as apoptosis and necrosis. However, this can be counterbalanced in cancer cells by activating antioxidant defenses. Nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (NRF2), a key transcriptional regulator of antioxidant genes, is upregulated in OC and mediates the removal of endogenously produced ROS in cancer cells [78, 216].

The chemokine CXCL8 plays an important role in the progression of diverse tumor types, including OC. CXCL8 activates multiple intracellular signaling pathways, which facilitate tumor cell proliferation, epithelial-to-mesenchymal transition, and angiogenesis and inhibit anti-tumor immune responses [217]. Recently, high levels of serum CXCL8 and ROS have been found to be significantly associated with a poor prognosis in OC patients. Analyses of ovarian cancer cells and tumor tissues have revealed that increased ROS up-regulated CXCL8 through inactivation of glycogen synthase kinase-3 beta and activation of p70S6 kinase (Qiu et al., 2025) [218]. Importantly, pharmacological inhibition of p70S6 kinase strongly increased the cytotoxic effects of platinum on OC lines.

Multiple studies in OC brought attention to defects in intracellular mechanisms controlling NO production by inducible NOS, leading to persistent activation of iNOS gene expression and increased iNOS activity [219]. NO and iNOS are considered important players with both pro-tumor and anti-tumor activity, but their importance in ovarian tumors is still far from being understood. The outcomes of clinical studies support the hypothesis that high iNOS expression in ovarian tumours is associated with an increased risk of disease relapse and patient death. In contrast, some in vitro studies on OC cell lines suggest a correlation between high iNOS expression and cisplatin sensitivity.

High amounts of iNOS-generated NO and derived RNS target genes control cell growth, DNA repair processes, and apoptosis. As an example, in various carcinomas, including OC, increased iNOS activity strongly correlates with RNS-induced point mutations in the transcription factor TP53, leading to the loss of its p53 suppressor activity [220]. However, the suggested use of iNOS expression as a prognostic factor for OC is not clear, as the published data are controversial and show both the potential and the lack of prognostic value of iNOS expression [219]. Based on OC liquid biopsy, metabolites in the L-arginine/NO pathway, symmetric dimethylarginine and L-arginine, were proposed as potential biomarkers for OC assessment [221]. For similar reasons, the experimental and clinical evidence for the therapeutic potential of targeting NO signaling in OC is still limited [222]. Improved specificity and effectivity in targeting components of the NO metabolism in cancer cell tissues might provide new advances in NO-based in future cancer therapies. Available NO-releasing nanoparticles already showed a promising extent of growth inhibition of tumor-derived and Ras-transformed ovarian cells [223].

Conclusions and future perspectives

As reviewed in the present article, RONS are involved in the control of several processes at the ovarian level, such as the formation and regression of the CL, its hormone production, ovulation, oocyte maturation, and ovarian angiogenesis. A slight increase in RONS is important for the upregulation of these processes. On the other hand, a number of studies demonstrate that increasing antioxidant protection can downregulate these processes. In the context of new findings that RONS is also positively related to mitochondrial biogenesis, a shift to moderate oxidative stress at the start of many physiological processes seems to be obvious.

Despite the considerable advances in the field of reproductive biology in recent decades, multiple contrasting results on RONS functions leading to controversial hypotheses have been accumulated, and are subjects of continuous debates, as overviewed herein. The dual nature of ROS as both detrimental and potentially beneficial signaling molecules remains a significant point of controversy. While excessive ROS are widely recognized for causing oxidative damage to ovarian cells, emerging evidence suggests that moderate ROS levels may be crucial for critical physiological processes such as follicular development, ovulation, and CL formation. This includes also inconsistent findings in reproductive pathologies regarding the precise mechanisms by which ROS and NO contribute to conditions like PCOS and OC. The complex interplay between RONS and the components of signaling and antioxidant pathways, as well as their potential as diagnostic or therapeutic targets, requires further systematic investigation. Similarly to other biological phenomena involving oxidative stress, the methodological limitations associated with current techniques for measuring ROS and NO in ovarian tissues present significant challenges. Variability in experimental approaches, limited sensitivity of detection methods, and the dynamic, transient nature of these molecules complicate a comprehensive understanding of their physiological roles. Moreover, the ranges of physiological levels or pathogenesis thresholds for RONS and their metabolites seem to differ in a species- and cell-specific manner.

Based on the current knowledge summarized in this article, we would like to outline several future research perspectives. Novel real-time imaging technologies, such as genetically encoded redox sensors, are becoming available that can track RONS dynamics in living ovarian tissues. This would provide new insights into the precise spatiotemporal regulation of RONS levels during follicular development, ovulation, and CL formation. Implementing rapidly advancing multi-omics analyses, such as single-cell transcriptomics and metabolomics, might contribute to uncovering the complex molecular networks involving RONS and other signaling molecules in ovarian physiology. In line with current trends of personalized medicine, personalized oxidative stress profiling can contribute to investigating individual variations in RONS signaling across different reproductive stages and pathological conditions and subsequently lead to more targeted diagnostic and therapeutic interventions. This can be foreseen not only in the field of human physiology and pathologies but also in veterinary reproductive medicine for some highly valued domestic animals. Finally, designing new precisely targeted interventions with RONS modulators, such as antioxidants, NO donors, or scavengers, can potentially offer new therapeutic approaches for the efficient treatment of reproductive disorders while preserving the physiological signaling functions of RONS.

Footnotes

† Grant Support: This study was supported by the Ministry of Agriculture of the Czech Republic (NAZV, grant no. QK22010270) and by the Slovak Research and Development Agency, Slovak Republic (grant no. APVV-19-0111).

Contributor Information

Jiří Bezdíček, Department of Zoology, Faculty of Science, Palacký University, Olomouc, Czech Republic.

Jana Sekaninová, Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, Palacký University, Olomouc, Czech Republic.

Martina Janků, Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, Palacký University, Olomouc, Czech Republic.

Alexander Makarevič, National Agricultural and Food Centre, Research Institute for Animal Production Nitra, Lužianky-near-Nitra, Slovak Republic.

Lenka Luhová, Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, Palacký University, Olomouc, Czech Republic.

Linda Dujíčková, National Agricultural and Food Centre, Research Institute for Animal Production Nitra, Lužianky-near-Nitra, Slovak Republic.

Marek Petřivalský, Department of Biochemistry, Faculty of Science, Palacký University, Olomouc, Czech Republic.

Author contributions

JB and MP conceived the idea. JB, AM, and MP wrote the original draft. LD, LL, and MJ designed and drew the figures, LL and JS supervised the manuscript. All authors edited the manuscript and approved the final version.

Conflict of Interest: The authors have declared that no conflict of interest exists.

Data avaibility

There are no new data generated or associated with this review article

References

- 1. Li L, Shi X, Shi Y, Wang Z. The Signaling pathways involved in ovarian follicle development. Front Physiol 2021; 12:730196. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Thatcher WW. A 100-year review: historical development of female reproductive physiology in dairy cattle. J Dairy Sci 2017; 100:10272–10291. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Davis JS, Rueda BR. The corpus luteum: an ovarian structure with maternal instincts and suicidal tendencies. Front Biosci 2002; 7:d1949–d1978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Mlyczynska E, Kiezun M, Kurowska P, Dawid M, Pich K, Respekta N, Daudon M, Rytelewska E, Dobrzyn K, Kaminska B, Kaminski T, Smolinska N, et al. New aspects of corpus luteum regulation in physiological and pathological conditions: involvement of adipokines and neuropeptides. Cells 2022; 11:957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Agarwal A, Aponte-Mellado A, Premkumar BJ, Shaman A, Gupta S. The effects of oxidative stress on female reproduction: a review. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2012; 10:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Ciani F, Cocchia N, d’Angelo D, Tafuri S. In: Wu B (ed.), Influence of ROS on Ovarian Functions. IntechOpen; 2015: 10.5772/61003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Fujii J, Iuchi Y, Okada F. Fundamental roles of reactive oxygen species and protective mechanisms in the female reproductive system. Reprod Biol Endocrinol 2005; 3:43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Basini G, Grasselli F. Nitric oxide in follicle development and oocyte competence. Reproduction 2015; 150:R1–R9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Hattori M, Sakamoto K, Fujihara N, Kojima I. Nitric oxide: a modulator for the epidermal growth factor receptor expression in developing ovarian granulosa cells. Am J Phys 1996; 270:C812–C818. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Luo Y, Zhu Y, Basang W, Wang X, Li C, Zhou X. Roles of nitric oxide in the regulation of reproduction: a review. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 2021; 12:752410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Nath P, Maitra S. Physiological relevance of nitric oxide in ovarian functions: an overview. Gen Comp Endocrinol 2019; 279:35–44. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nishikimi A, Matsukawa T, Hoshino K, Ikeda S, Kira Y, Sato EF, Inoue M, Yamada M. Localization of nitric oxide synthase activity in unfertilised oocytes and fertilised embryos during preimplantation development in mice. Reproduction 2001; 122:957–963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Rosselli M, Keller PJ, Dubey RK. Role of nitric oxide in the biology, physiology and pathophysiology of reproduction. Hum Reprod Update 1998; 4:3–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Zhao Y, Vanhoutte PM, Leung SW. Vascular nitric oxide: beyond eNOS. J Pharmacol Sci 2015a; 129:83–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Jîtcă G, Ősz BE, Tero-Vescan A, Miklos AP, Rusz CM, Bătrînu MG, Vari CE. Positive aspects of oxidative stress at different levels of the human body: a review. Antioxidants (Basel) 2022; 11:572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kawagishi H, Finkel T. Unraveling the truth about antioxidants: ROS and disease: finding the right balance. Nat Med 2014; 20:711–713. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Poljsak B, Suput D, Milisav I. Achieving the balance between ROS and antioxidants: when to use the synthetic antioxidants. Oxidative Med Cell Longev 2013; 2013:956792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Checa J, Aran JM. Reactive oxygen species: drivers of physiological and pathological processes. J Inflamm Res 2020; 13:1057–1073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Harris IS, DeNicola GM. The complex interplay between antioxidants and ROS in cancer. Trends Cell Biol 2020; 30:440–451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Tang Z, Chen J, Zhang Z, Bi J, Xu R, Lin Q, Wang Z. HIF-1alpha activation promotes Luteolysis by enhancing ROS levels in the corpus luteum of Pseudopregnant rats. Oxidative Med Cell Longev 2021; 2021:1764929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Zamberlam G, Sahmi F, Price CA. Nitric oxide synthase activity is critical for the preovulatory epidermal growth factor-like cascade induced by luteinising hormone in bovine granulosa cells. Free Radic Biol Med 2014; 74:237–244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Motta AB, Estevez A, de Gimeno MF. The involvement of nitric oxide in corpus luteum regression in the rat: feedback mechanism between prostaglandin F(2alpha) and nitric oxide. Mol Hum Reprod 1999; 5:1011–1016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Noda Y, Ota K, Shirasawa T, Shimizu T. Copper/zinc superoxide dismutase insufficiency impairs progesterone secretion and fertility in female mice. Biol Reprod 2012; 86:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Gonzalez-Pacheco FR, Deudero JJ, Castellanos MC, Castilla MA, Alvarez-Arroyo MV, Yague S, Caramelo C. Mechanisms of endothelial response to oxidative aggression: protective role of autologous VEGF and induction of VEGFR2 by H2O2. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 2006; 291:H1395–H1401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Wang K, Zheng J. Signaling regulation of fetoplacental angiogenesis. J Endocrinol 2012; 212:243–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Brillo V, Chieregato L, Leanza L, Muccioli S, Costa R. Mitochondrial dynamics, ROS, and cell Signaling: a blended overview. Life (Basel) 2021; 11:332. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Venditti P, Di Meo S. The role of reactive oxygen species in the life cycle of the mitochondrion. Int J Mol Sci 2020; 21:2173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Yoboue ED, Devin A. Reactive oxygen species-mediated control of mitochondrial biogenesis. Int J Cell Biol 2012; 2012:403870. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Yan F, Zhao Q, Li Y, Zheng Z, Kong X, Shu C, Liu Y, Shi Y. The role of oxidative stress in ovarian aging: a review. J Ovarian Res 2022; 15:100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Gao X, Wang B, Huang Y, et al. Role of the Nrf2 Signaling pathway in ovarian aging: potential mechanism and protective strategies. Int J Mol Sci 2023; 24:13327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Goutami L, Jena SR, Swain A, Samanta L. Pathological role of reactive oxygen species on female reproduction. Adv Exp Med Biol 2022; 1391:201–220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]