Abstract

A 67-year-old man had a tumor on his right cheek. It was resected 15 years earlier but recurred 1 year before his first visit. He had a red papule on his right cheek and subcutaneous induration in the right preauricular area. A right cheek biopsy revealed a mucinous carcinoma. The positron emission tomography-computed tomography showed accumulation only in the right cheek and parotid gland lymph node; therefore, we diagnosed primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma. Sentinel lymphoscintigraphy showed accumulation of parotid gland and level II lymph node. He underwent extended resection and sentinel-node biopsy. Both lymph nodes were metastatic, requiring the appropriate range of neck dissection. There were no recurrence and metastasis postoperatively. There is no effective treatment when distant metastasis occurs, and the prognosis is poor. Therefore, it is important to prevent metastasis. However, positron emission tomography-computed tomography could not reveal early micrometastases. Therefore, a sentinel-node biopsy can be key to early detection and treatment.

Keywords: malignant skin tumor, rare skin tumor, lymph node metastasis, primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma, PET-CT

Background

New therapeutic agents, such as anti-programmed cell death protein 1 inhibitors, have significantly changed treatment strategies for several skin cancers, including malignant melanoma and Merkel cell carcinoma. However, effective systemic therapy for rare skin cancer metastases is lacking. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma (PCMC) with lymph node metastasis progresses to distant metastasis in approximately half the cases. PCMCs with metastasis have a poor prognosis. Therefore, complete resection in the early phase is important. We report a case of PCMC with cervical lymph node metastasis. In our case, sentinel lymph node biopsy revealed micrometastasis that was not identifiable using (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose-Positron emission tomography (FDG-PET).

Case Presentation

A 67-year-old man presented with a right cheek subcutaneous tumor. He underwent tumor resection at another hospital 15 years earlier and was referred to our department because of gradual tumor growth a year before his visit. The patient had a history of type 2 diabetes mellitus and an abdominal aortic aneurysm.

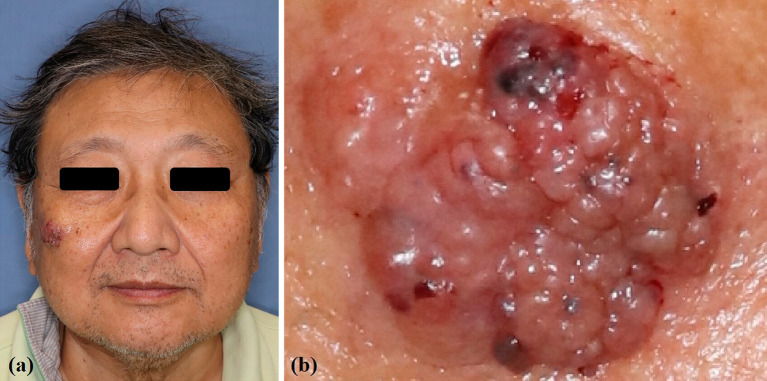

Clinical findings showed a 3 × 2.5 cm2 red mass on the right cheek and a subcutaneous induration in front of the right ear (Figure 1a, b). MRI demonstrated the tumor invading the buccinator muscle. A cheek mass biopsy revealed unequally sized tumor cell nests surrounded by fibrous septa. The nests contained multiple mucus components with scattered tumor cell aggregates. Thus, mucinous carcinoma was diagnosed (Figure 2a, b). Immunohistochemistry analysis was positive for CK7 and negative for CK5/6, p63, CK20, and D2-40 (Figure 2c, d). Histopathology revealed a mucinous carcinoma.

Figure 1.

Physical findings.

(a) Clinical findings showing a 3 × 2.5 cm2 red mass on the right cheek.

(b) The tumor with an irregular surface, including microhemorrhagic lesions.

Figure 2.

Histopathological findings.

(a) Hematoxylin and eosin (H–E) (50×): tumor cell nests of unequal size surrounded by fibrous septa. The nests contain multiple mucus components, with tumor cell aggregates scattered in the mucus.

(b) H-E staining (350×): tumor cells proliferate in a foaming cribriform-like structure.

(c): Immunohistochemistry staining (100×): tumor cells positive for CK7.

(d): Immunohistochemistry staining (100×): tumor cells negative for CK20.

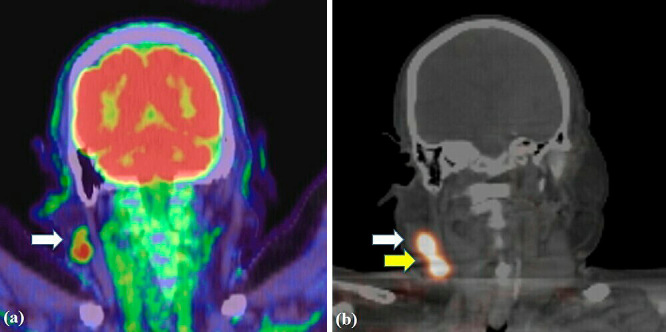

PET-CT showed FDG accumulations in the right cheek tumor and parotid lymph node (Figure 3a). PET-CT and gastrointestinal endoscopy revealed no distant metastasis or other primary mucinous carcinomas. The patient was consequently diagnosed with PCMC.

Figure 3.

Imaging findings.

(a): Positron emission tomography-computed tomography image showing a tumor in the right cheek region and accumulation of (18)F-fluorodeoxyglucose in the lymph node of the right parotid gland.

(b): Preoperative lymphoscintigraphy image revealing the right parotid and cervical lymph nodes.

Preoperative lymphoscintigraphy showed the right parotid and cervical level II lymph nodes (Figure 3b); however, PET-CT did not reveal the cervical lymph node accumulation.

We performed extended resection with a 20-mm surgical margin and buccinator muscle tumor. Sentinel lymph node biopsy was performed using a radioisotope (technetium-99 m-labeled phytate) with combined dye and fluorescence methods (intradermal injection of 0.4-mL patent blue and 0.4-mL indocyanine green).

Sentinel lymph node biopsy was performed using the malar flap incisional approach, and the parotid and cervical lymph nodes were positive for metastasis1). Cervical dissections (I, II, III, and V) were performed and reconstructed with a cervicofacial flap (Figure 4a, b, c). The number of dissected lymph nodes was 2/9, and there was no metastasis in any lymph node except for the sentinel lymph node. At the 10-month postoperative follow-up, the patient's progress was favorable (Figure 5). One year after the operation, contrasted CT showed no recurrence and metastasis.

Figure 4.

Intraoperative view.

(a): We designed an incisional line according to extended resection with 20 mm surgical margin and malar flap incisional approach.

(b): After an extended resection and neck dissection.

(c): Reconstruction by cervicofacial flap.

Figure 5.

10 months after the surgery; There were no complication and recurrence.

He developed a cardiogenic stroke and is currently admitted to another hospital; however, his survival has been confirmed at 18 months postoperatively. Additionally, no apparent recurrent metastases occurred.

Discussion and Conclusions

Lennox et al. first reported PCMC in 1952, as a very rare skin cancer with an incidence of 0.07 per million people2,3). Because mucinous carcinoma of the skin is often metastatic, mucinous carcinoma in other organs is common. Therefore, it is necessary to exclude metastatic tumors through general examination and systemic workup to diagnose PCMC.

Recently, clinical feature differences between PCMC and cutaneous metastases of other mucinous carcinomas have been reported: PCMC is more prevalent in the head and neck regions, whereas cutaneous metastases of mucinous carcinoma are more common in the abdominal wall4). Furthermore, a prolonged clinical course is a characteristic of PCMC, and the typical clinical findings of PCMC are consistent with those in our case.

Local recurrence of PCMC is relatively common, at 30%-40%, while distant metastasis is extremely rare at 3%5). Therefore, the overall prognosis of PCMC is favorable. However, on the development of regional lymph node metastasis, distant metastasis, which has a poor prognosis, has been observed in half the cases till date6).

Kamalpour et al. have reported 159 PCMC cases from 1952 to 2010 and 13 distant metastasis cases; however, the details of these cases are not described. Distant metastases are resistant to chemotherapy and radiotherapy, and as they are extremely rare, there is no established treatment. There have been three reported cases of distant metastases with details of the clinical course6-8); since the prognosis was poor, all three patients died within a few years. Thus, early detection and lymph node dissection are necessary to improve the PCMC prognosis.

The frequency of regional lymph node metastasis in all PCMC cases is approximately 10%, while regional lymph node metastasis in the trunk is approximately 23%, which varies depending on the site5).

Kamalpour et al., in a meta-analysis, identified favorable prognostic factors, including head and neck lesions and being of East Asian descent5). In Japan, there were reported 100 PCMC cases, including ours. The local PCMC recurrence rate was 16% (16/100), lower than that reported in other countries. However, the regional lymph node metastasis rate (7.9%), and the distant metastasis rate (2.9%) were similar to other studies.

Despite the low recurrence rate of the primary tumor, the comparable incidence of lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis may indicate that some cases have already spread to the lymph nodes even if the primary tumor had been completely resected.

Recurrence is lower in some racial groups. However, there is no difference in the incidence of lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis, which plays an important role in prognosis. Therefore, the disease may not be associated with a good prognosis in our country. Furthermore, Kamalpour et al. found that the metastasis and recurrence rate increase when the initial tumor diameter is 1.5 cm or larger5). In our case, the site of origin was the head and neck region, which was a favorable prognostic factor. However, the tumor was more than 1.5 cm in diameter and was prone to lymph node metastasis and distant metastasis. Therefore, a sentinel lymph node biopsy was performed. We believe that sentinel lymph node biopsy may be indicated when the tumor is larger than 1.5 cm or when the tumor is in the trunk.

PET-CT has a high detection rate for PCMC lymph node metastases. However, PET-CT cannot detect early micrometastases9). Some lymph node metastasis may develop several years after the primary PCMC resection. In our case, PET-CT showed 18F-FDG accumulation in the enlarged parotid lymph nodes but not in level II lymph nodes.

However, lymph node metastasis was also identified intraoperatively in level II lymph nodes by sentinel lymph node biopsy, which was useful in setting the area of lymph node dissection.

In cases with a favorable prognosis, a 5-10 mm surgical margin is recommended10). However, there are very few reports on the resection area in large tumor diameter or trunk incidence cases. Therefore, there are no standardized guidelines for PCMC because it is rare cancer. As mentioned previously, the rate of metastasis and recurrence increases when the tumor diameter is 1.5 cm or larger. Therefore, we used the 20-mm margin previously recommended for lymph node metastasis11). There are no reports describing the details of the vertical margin. In our case, the primary tumor was in contact with the muscle layer on MRI; hence we performed a radical resection at a 20-mm margin on the periosteum.

PCMC has a good prognosis with early detection and complete resection. However, once lymph node metastasis occurs, there is a risk of distant metastasis. Therefore, we consider that sentinel lymph node biopsy can be a key to treatment in cases with large tumors or those on the trunk, which have a high risk of metastasis.

Author Contributions: H Motomura and H Fujikawa offered valuable feedback regarding the study. T Hatano assisted in the early stages of this work. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Conflicts of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

Ethical Approval: The need for ethical review and approval was waived for this study because informed consent was obtained from the patient for using the patient's medical information.

Consent to Participate: The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Consent for Publication: Informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this study.

Acknowledgments

We thank Editage (www.editage.com) for English language editing.

References

- 1.Motomura H, Hatano T, Maruyama Y, et al. A malar flap incisional approach for sentinel lymph-node biopsy in patients with periocular skin malignancies. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2009;62:e184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Breiting L, Christensen L, Dahlstrøm K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a population-based study. Int J Dermatol. 2008;47:242-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lennox B, Pearse AG, Richards HG. Mucin-secreting tumours of the skin with special reference to the so-called mixed-salivary tumour of the skin and its relation to hidradenoma. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1952;64:865-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brownstein MH, Helwig EB. Metastatic tumors of the skin. Cancer. 1972;29:1298-307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kamalpour L, Brindise RT, Nodzenski M, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma: a systematic review and meta-analysis of outcomes after surgery. JAMA Dermatol. 2014;150:380-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yugueros P, Kane WJ, Goellner JR. Sweat gland carcinoma: a clinicopathologic analysis of an expanded series in a single institution. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1998;102:705-10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jih MH, Friedman PM, Kimyai-Asadi A, et al. A rare case of fatal primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma of the scalp with multiple in-transit and pulmonary metastases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52:S76-80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miyasaka M, Tanaka R, Hirabayashi K, et al. Primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin: a case of metastasis after 10 years of disease-free interval. Eur J Plast Surg. 2009;32:189-93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kitamura S, Hata H, Inamura Y, et al. Positron emission tomography-computed tomography can be useful in the early detection of metastases in primary mucinous carcinoma of the skin on the head and neck. Br J Dermatol. 2015;173:1263-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi JH, Kim SC, Kim J, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma treated with narrow surgical margin. Arch Craniofac Surg. 2016;17:158-61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fin A, D'Alì L, Mura S, et al. Primary cutaneous mucinous carcinoma of the chin: report of a case. Indian J Pathol Microbiol. 2019;62:173-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]