Abstract

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a severe central nervous system injury without effective therapies. PANoptosis is involved in the development of many diseases, including brain and spinal cord injuries. However, the biological functions and molecular mechanisms of PANoptosis-related genes in spinal cord injury remain unclear. In the bioinformatics analysis of public data of SCI, the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) identified by GSE151371 were hybridized with PANoptosis-related genes (PRGs) to obtain differentially expressed PANoptosis-related genes (DE-PRGs). Through three machine learning algorithms, we obtained the hub genes. Then, we constructed functional analysis, drug prediction, regulatory network construction, and immune infiltrating cell analysis. Finally, the expression of the hub gene was verified in GSE93561, GSE45376, and qRT-PCR analysis. Through the above analysis, 14 DE-PRGs were obtained by intersecting 3582 DEGs with 46 PRGs. Five key hub genes, CASP4, GSDMB, NAIP, NLRC4, and NLRP3, were obtained by 3 machine learning algorithms. All five hub genes were enriched in phagocytosis mediated by FC GAMMA R. The 11 immune cells were significantly different between spinal cord injury (SCI) group and human control (HC) group, such as mast cell and gamma delta T cell. The transcription factor (TF)-hub gene network contained 10-nodes (4 hub genes and 6 TFs) and 8-edges. The miRNA-hub gene network consisting of 5-nodes (3 hub genes and 2 miRNAs) and 3-edges was constructed. Moreover, the CASP4 predicted 1 small molecule drug and NLRP3 predicted 9 small molecule drugs. Finally, the expression of 5 hub genes were significantly different in GSE45376 and GSE93561 (SCI vs. HC) and mice SCI model (Sham vs. SCI). Collectively, we identified 5 hub genes (CASP4, GSDMB, NAIP, NLRC4, and NLRP3) associated with PANoptosis, providing potential directions for treating spinal cord injury.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12035-025-04717-8.

Keywords: Spinal cord injury, PANoptosis, Hub genes, Immune cell, Drug prediction

Introduction

Spinal cord injury (SCI) is a severe injury associated with sensory, motor, and autonomic dysfunction. With the development of transportation and construction in modern society, disease incidence is also increasing, with about 100,000 new patients yearly [1]. Due to severe sequelae of neurological dysfunction, patients with SCI have low self-care ability, which burdens families and society with heavy spiritual and economic burdens. Although there are many studies on treating SCI, there is no specific effective one.

According to the process and mechanism of injury, SCI is usually divided into two stages: primary injury and secondary injury [2]. In primary injury, neuronal death occurs at the moment of injury, primarily due to physical injuries that cannot be controlled or treated, including mechanical tears, cuts, or strains. The occurrence time of secondary injury is later than that of primary injury. Based on primary injury, physiological and biochemical mechanisms, such as tissue edema, necrosis, and apoptosis, cause self-destructive damage to good tissues around the initial injury, further deepening and expanding the injury degree [3]. The study of alleviating and regulating secondary injury may be a breakthrough in finding effective treatment for SCI or improving its prognosis. The degree of tissue cell death directly affects the prognosis of SCI, especially the death of non-regenerative neurons, which is unfavorable in secondary injury. The survival function of neurons directly affects the recovery of spinal cord function. Therefore, protecting neurons after SCI and reducing the occurrence of regulatory death is the key to promoting nerve regeneration and maximizing spinal cord function recovery.

Cell death is a universal phenomenon in living organisms and a necessary condition for maintaining homeostasis in living organisms. Programmed cell death (PCD) is a genetically determined pattern of active cell death, including pyroptosis, apoptosis, and cell necrosis [4, 5], closely associated with homeostasis and disease. The interaction of pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necrosis pathways has led to the concept of PANoptosis [6], which is defined as an inflammatory PCD pathways regulated by the PANoptosome complex [7] and characterized primarily by pyroptosis, apoptosis, or necrosis, which cannot be explained by these PCD pathways alone [8]. PANoptosis emphasizes the interaction and coordination between pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necrosis. Studies have reported that PANoptosis is involved in the progression of various diseases, including tumor and non-tumor diseases [9–11]. For example, Caspase 8 (CASP8), a molecular switch that controls pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necrosis, is a key protein in the cancer panapoptotic crosstalk signaling pathway [12]. Recent studies have shown that ZBP1 activates PANoptosis through RIPK3 signal, ADAR1 negatively regulates ZBP1-mediated apoptosis, and blocking ADAR1 activity contributes to apoptosis and inhibits tumorigenesis [13]. In addition, treatment with an apoptosis inhibitor inhibited pyroptosis and activated necrosis in a rat model of septic-associated encephalopathy [14]. Pyroptosis inhibitors inhibit pyroptosis and apoptosis but activate necrosis [15]. However, apoptosis and pyroptosis are activated when necrosis is inhibited [16]. It can be seen that the pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necrosis of cells are closely related and regulate each other. Therefore, it is of great significance to understand the mechanism of PANoptosis and provide options for treating human diseases.

PCD after SCI is an important factor that makes it difficult to recover spinal cord nerve function [17]. Ischemia, hypoxia, and the release of the histiocytic fragmentation lead to the injury of the remaining nerve cells around the damage, thereby inducing and activating PCD triggered by gene regulation. Triggered PCD include apoptosis, necrosis, pyroptosis, iron necrosis, copper necrosis, and autophagy [18]. PANoptosis is a novel cell death mode involving multiple molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways that ultimately lead to cell death. After spinal cord injury, the local microenvironment changes significantly, such as the deficiency of nerve growth factor, calcium ion inflow, and oxygen free radical increase. These changes activate molecular mechanisms and signaling pathways associated with PANoptosis, such as membrane receptor pathways such as Fas/Apo1 and biochemical pathways such as cytochrome C release [19]. Activation of these pathways eventually leads to the occurrence of PANoptosis in nerve cells.

Treating SCI has always been a complex problem in the medical field. However, the biological function and molecular mechanism of PANoptosis-related genes (PRGs) in SCI remain unclear. In this paper, the key genes associated with PANoptosis in SCI were identified by the bioinformatics analysis, and the possible biological functions and pathways of the key genes were analyzed, as well as their relationship with immune properties and drugs, in order to provide a reference for the treatment of patients with SCI.

Materials and Methods

Data Source

Spinal cord injury-related datasets (GSE151371, GSE93561, and GSE45376) were downloaded from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/). GSE151371 included 38 human spinal cord injury (SCI) blood samples and 10 human control (HC) blood samples. GSE93561 included 6 spinal cord tissue samples from injured mice and 6 control samples. GSE45376 included 3 spinal cord tissue samples 2 days after injury, 3 spinal cord tissue samples 7 days after injury, and 2 mouse control samples. A total of 46 PANoptosis-related genes (PRGs) (Table S1) were downloaded from previous studies [20, 21].

Identification of Differentially Expressed Genes (DEGs)

The R package DESeq2 was used for the differential analysis of GSE151371 (SCI vs. HC). Screening criteria were padj < 0.05&|log2FoldChange (FC)|> 1 [22]. We intersect DEGs and PRGs through the ggVennDiagram to get DE-PRGs.

Functional Analysis of DE-PRGs

Gene Ontology (GO), Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genomics (KEGG), and HALLMARK of Msigdb database (https://www.gsea-msigdb.org/gsea/msigdb) were used as background genes. The enrichment analysis of DE-PRGs was carried out using R “clusterProfiler” [23, 24].

Construction of Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Network

The PPI network was established using the STRING database (https://cn.string-db.org/), and Cytoscape software was used to visualize the network. We used MCODE to screen out the core subnetwork (Score:9, Nodes:9, Edges:36) [25].

Machine Learning

The hub gene was identified using the least absolute shrinkage and selection operator (LASSO) algorithm (via “glmnet” R), Support Vector Machine-Recursive Feature Elimination (SVM-RFE) algorithm (via “caret” R), and eXtreme Gradient Boosting (XGBoost) algorithm (via “xgboost” R) [26, 27].

Analysis of Immune Cell Infiltration

The infiltration abundance of 28 immune cells in GSE151371 was evaluated using the single sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA) algorithm of R-packet “GSVA” [28]. Key immune infiltrating cells were identified based on Wilcoxon analysis and the LASSO algorithm.

Construction of the Molecular Regulatory Network

According to the Network Analyst platform (https://www.networkanalyst.ca/), the JASPER database was used to predict transcription factors (TFs) targeting the hub genes. TarBase and miRTarBase databases predicted miRNAs targeting hub genes [29].

Small Molecule Drugs for Hub Genes

The DGidb database (https://dgidb.org/) was used to predict the small molecule drugs corresponding to the hub gene. The interaction score of the DGIdb database is used to assess the strength of the interaction between the drug and the hub gene. The hub gene proteins and 3D structures of therapeutics were obtained from the PDB protein database (https://www1.rcsb.org/) and the NCBI PubChem Compound Database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pccompound/) [30, 31].

Animals and SCI Model

Six female C57BI/6 J mice (8 weeks old, weight 20 ± 2.0 g) were used to establish SCI models and validate gene expression in this study. Under a single intraperitoneal injection of pentobarbital sodium solution (0.1 ml/10 g), the surgical area was shaved and disinfected with iodophor. Spinal cord injury was performed using a spinal cord impactor. The mice underwent T10 laminectomy using a midline skin incision between T9 and T11, and a midline spinal contuse was performed with a force of 0.7N at the exposed T10 level. Mice in the sham-operated group were anesthetized for a similar duration but without laminectomy and spinal cord shock. The bladder and abdominal cavity were manually pressed 3 times a day to induce urination until the peripheral blood, and the spinal cords were collected 2 h, 2 days, and 7 days after SCI operation. After operation, mice were given access to drinking water containing 1 mg/ml penicillin for infection prophylaxis until euthanasia.

qRT-PCR Analysis

Spinal cord tissue was extracted, and qRT-PCR was performed. Spinal cord tissue homogenate was taken, and every 50–100 mg tissue add 1 ml Trizol (Solarbio, R1200, China). Add 0.2 ml of chloroform, shake violently for 15 s, and leave for 5 min at room temperature, centrifugation at 12,000 rpm for 10 min at 4 ℃. RNA is mainly in the upper colorless aqueous phase; transfer the aqueous phase to a new tube and do not absorb the precipitate. Five hundred microliters eluent was added to the adsorption column, placed at room temperature for 2 min, centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4 ℃ for 2 min, and the waste liquid was discarded. Two hundred microliters of absolute ethanol was added to the supernatant collected and mixed, then added to the adsorption column for 2 min, centrifuged at 12,000 rpm at 4 ℃ for 2 min, and the waste solution was discarded. Add 600 μL of bleach solution (absolute ethanol was added) to the adsorption column, centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 2 min at 4 ℃, and discard the waste solution. Repeat the previous step. Centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 2 min at 4 ℃, discard the collection tube, and place the adsorption column at room temperature for 10 min to remove the residual rinse solution in the adsorption column. Put the adsorption column into a new tube, add 50 μL RNase Free ddH2O to the center of the membrane, place at room temperature for 5 min, and centrifuge at 12,000 rpm for 2 min to obtain RNA. cDNA was reverse-transcribed by Hifair® III 1st Strand cDNA Synthesis SuperMix (11141ES60, Yeasen, Shanghai, China). Quantitative real-time polymerase chain reaction (qRT-PCR) was determined quantitatively on real-time PCR System (MA-6000, Molarray, China) using Hieff® qPCR SYBR Green Master Mix (11201ES08, Yeasen, Shanghai, China). GAPDH was used as a positive internal control, and gene expression levels were calculated by the formula 2 − ∆∆CT. The sequences of primers used are listed in Table S2.

Statistical Analysis

Mouse and human genes are transformed according to the R packet “homologene.” Student’s t-test or Wilcoxon rank sum tests were used to compare the two groups. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Identification and Enrichment Analysis of DE-PRGs

We identified 3582 DEGs (SCI vs. HC) in GSE151371, of which 1706 DEGs were up-regulated, and 1876 DEGs were down-regulated (Fig. 1A). DEGs was intersected with 46 PRGs of AIM2, NLRP3, FADD, CASP4, CASP5, CASP1, RIPK3, PYCARD, MLKL, GSDMB, PSTPIP2, NLRC4, NAIP, and GSDMD to obtain 14 DE-PRGs (Fig. 1B). Correlation analysis showed that the expression of GSDMB was negatively correlated with the expression of CASP1, CASP5, AIM2, CASP4, PSTPIP2, NLRC4, NAIP, MLKL, NLRP3, FADD, RIPK3, and PYCARD, while the expression of genes except GSDMB was positively correlated with each other (Fig. 1C). Additionally, 3 HALLMARK pathways, 366 GO, and 2 KEGG were enriched according to 14 DE-PRGs. In the HALLMARK channel, CASP4, CASP5, and CASP1 participate in “COMPLEMENT,” “APOPTOSIS,” and “INTERFERON GAMMA RESPONSE” (Fig. 1D). In graphene oxide, these DE-PRGs are associated with “inflammasome complexes,” “pyroptosis,” and “active regulation of the inflammatory response” (Fig. 1E). In the KEGG results, these DE-PRGs were enriched in the “NOD-like receptor signaling pathway” and the “cytoplasmic DNA sensing pathway” (Fig. 1F).

Fig. 1.

Analysis of DE-PRGs. A Volcano plot representing PCD-related differentially expressed genes. In the volcano plots, the red points show upregulated genes (log2FC ≥ 0.5 and p-value < 0.05), whereas the blue points represent downregulated genes. B Venn diagrams for DEG-IRGs. 14 DEG-IRGs were obtained. C Correlation analysis of DE-PRGs. D–F GO and KEGG analysis of the DE-PRGs. Red marks indicate a positive correlation, and blue is a negative correlation

Identification of Hub Genes

To explore whether there is interaction between DE-PRGs, we constructed a protein–protein interaction network consisting of 12 nodes and 56 edges. PPI results showed that GSDMB and PSTPIP2 were isolated targets and did not interact with other DE-PRGs (Fig. 2A). The network with the highest score based on the MCODE plug-in contains nine genes: CASP4, CASP5, NLRP3, GSDMD, CASP1, PYCARD, AIM2, NAIP, and NLRC4 (Fig. 2B). These nine genes enriched 6 GO and 2 KEGG, such as “typical inflammasome complex,” “pyroptosis,” “NLRP1 inflammasome complex,” and “Salmonella infection”(Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Pruning and identification of hub gene. A PPI interaction network of DE-PRGs. The PPI protein interaction network was analyzed for 14 DE-PRGs. The PPI interaction information was obtained with medium confidence > 0.4. We found that GSDMB and PSTPIP2 were isolated targets. B Modular gene screening. The subnetwork with the highest score contains nine genes, namely, CASP4, CASP5, NLRP3, GSDMD, CasP4, CasP5, NLRP3, CASP1, PYCARD, AIM2, NAIP, and NLRC4. In addition, the pan-apoptosis-related differential gene PPI protein interaction network contains 12 Nodes and 56 Edges. Score analysis of the PPI network with MCODE. C GO and KEGG analysis. Genes in the subnetworks with the highest scores were analyzed for GO and KEGG enrichment. According to p.adjust < 0.05 as the screening criterion, 6 GO functions and 2 KEGG pathways were enriched. Typical inflammasome complex, pyroptosis, positive regulation of interleukin-1β production, NLRP1 inflammasome complex, detection of biological stimuli, defense response to Gram-positive bacteria (GO function), Salmonella infection, Shigellosis (KEGG signaling pathway)

Based on DE-PRGs, LASSO screened 12 characteristic genes, namely, AIM2, NLRP3, FADD, CASP4, CASP5, CASP1, RIPK3, PYCARD, GSDMB, NLRC4, NAIP, and GSDMD (Fig. 3A, B). After the SVM-RFE algorithm, ten feature genes were obtained (Fig. 3C). XGBoost screened five characteristic genes, namely, ICASP4, NLRC4, GSDMB, NAIP, and NLRP3 (Fig. 3D). The cross genes obtained by the above three algorithms were defined as the key genes, namely, CASP4, GSDMB, NAIP, NLRC4, and NLRP3 (Fig. 3E). The expressions of CASP4, NAIP, NLRC4, and NLRP3 in GSE151371 HC samples were up-regulated compared with those in SCI samples, while the expression trend of GSDMB was reversed (Fig. 3F).

Fig. 3.

Machine learning algorithm. Three kinds of machine learning were carried out according to the expression of p DE-PRGs in the training set (GSE151371). A Ten cross-validations of adjusted parameters in Minimum Absolute Shrink and Selection Operator (LASSO) analysis. LASSO regression analysis was performed on DE-PRGs, and the feature genes whose regression coefficient was not penalized as 0 were obtained. The abscess is the logarithm of the lambdas, and the ordinate is the model error. As can be seen from the figure above, the optimal lambda value is at the lowest point of the red curve, and the corresponding number of variables is 12. They are AIM2, NLRP3, FADD, CASP4, CASP5, CASP1, RIPK3, PYCARD, GSDMB, NLRC4, NAIP, and GSDMD. B LASSO coefficient spectrum. The horizontal coordinate is the logarithm of the lambdas, and the vertical coordinate is the variable coefficient. As the lambdas increase, the variable coefficient approaches 0. When the optimal lambda is reached, the variable whose culling coefficient is equal to 0. C SVM-RFE analysis. Prediction accuracy of the number of different characteristic genes. The horizontal coordinate is the number of characteristic genes, and the vertical coordinate is the accuracy of model prediction. As shown in the figure, when the number of feature genes is 10, the prediction accuracy of the model is the highest. The characteristic genes were NAIP, NLRC4, CASP4, CASP5, GSDMB, FADD, NLRP3, CASP1, AIM2, and MLKL. D XGBoost analysis. The importance of XGBoost to screen for feature genes. The horizontal coordinate is the importance of characteristic genes. As shown in the figure, a total of 5 characteristic genes were finally screened, namely, ICASP4, NLRC4, GSDMB, NAIP, and NLRP3. E Venn diagram of Characteristic hub genes. The intersection of 13 Lasso genes, 10 SVM-RFE genes, and 5 XGBoost genes was mapped. As shown in the figure, a total of 5 intersection genes were obtained. The five hub genes are CASP4, GSDMB, NAIP, NLRC4, and NLRP3. F Violin map of hub gene expression. The expression levels of five hub genes (CASP4, GSDMB, NAIP, NLRC4, and NLRP3) were plotted between SCI and HC. The expression levels of CASP4, NAIP, NLRC4, and NLRP3 in SCI samples were significantly higher than those in HC samples, indicating up-regulated genes. The expression of GSDMB in HC samples was significantly higher than that in SCI samples, which was a down-regulated gene. There are 10 samples from healthy individuals without a history of CNS pathology (HC), and 38 samples are from individuals who suffered a traumatic spinal cord injury (SCI). ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ p < 0.0001

Analysis of Immune Cell Infiltration of Hub Gene

The heat map shows the immune cell abundance of 28 immune infiltrating cells in all samples of GSE151371 (Fig. 4A). Difference analysis showed significant differences in the enrichment scores of 13 types of SCI and HC immune infiltrating cells, including mast cells, immature dendritic cells, and macrophages (Fig. 4B). Additionally, 18 characteristic immune infiltrating cells were screened by the LASSO method. The cells obtained by the two methods were intersected to obtain 11 key immune infiltrating cells such as γδ T cells, neutrophils, and regulatory T cells (Fig. 4C). CASP4 was positively correlated with neutrophils (cor = 0.73). NLRC4 had the strongest negative association with activated CD8 T cells (cor = − 0.81) (Fig. 4D).

Fig. 4.

Immune cell infiltration analysis of hub genes. A Heat maps between SCI and HC samples based on immune infiltrating cell enrichment scores. The heatmap showed the immune cell abundance of 28 immune infiltrating cells. B Box plots based on 28 kinds of immune infiltrating cell enrichment fraction. The 13 types of immune infiltrating cells are different between SCI and HC. ∗ p < 0.05, ∗ ∗ p < 0.01, ∗ ∗ ∗ p < 0.001, and ∗ ∗ ∗ ∗ p < 0.0001. C Venn diagrams for LASSO-Wilcoxon analysis. Eleven11 key immune infiltrating cells were obtained. Venn diagram of Intersection of differential and characteristic immune infiltrating cells. The intersection of 13 differential immunoinfiltrates identified by Wilcoxon analysis and 18 characteristic immunoinfiltrates identified by Lasso was used to obtain the intersection of immunoinfiltrates. Eleven interlocking immune infiltrating cells, namely, key immune infiltrating cells, were obtained. D Heat map of key cell and hub gene correlation. The correlation heat map shows that the positive correlation between the hub genes CASP4 and neutrophil was the strongest, and the correlation coefficient was 0.73. The negative correlation between hub gene NLRC4 and Activated CD8 T cell was the strongest, and the correlation coefficient was − 0.81

Establishment of TF-Hub Gene Network and miRNA-Hub Gene

The intersection of 38 TFS predicted by the database and 3582 DEGs in GSE151371 was used to obtain six intersection TFS (Fig. 5A). The TF-hub gene network comprises ten nodes (4 hub genes and 6 TFS) and eight edges. NLRP3 is regulated by STAT3, CEBPB, and PPARG (Fig. 5B). Three intersection miRNAs were obtained using the two databases to predict the intersection of miRNAs (Fig. 5C). A miRNA-hub gene network consisting of 5 nodes (3 hub genes and 2 miRNAs) and three edges was constructed. NLRP3 predicts one miRNA, namely, hsa-mir-193b-3p (Fig. 5D).

Fig. 5.

TF-hub gene and miRNA-hub gene network. A Venn diagrams of transcription factors (TFs) and differential genes. Using the database, the TFs corresponding to 5 hub genes were predicted, and 32 TFs were predicted. Thirty-two TFs predicted by the database were intersected with 3582 differential genes identified in this study to obtain the intersection TFs. A total of 6 intersection TFs are obtained, that is, differential TFs. B Correspondence diagram. The TF regulatory network consists of 10 Nodes (4 hub genes, 6 TFS) and 8 Edges. Circles (red up-regulated genes, green down-regulated genes) represent hub genes, and rectangles represent differential TFs. C Venn diagram of miRNA-mRNA relationship. Prediction of miRNA corresponding to 5 hub genes from Database. A total of 3 pairs of miRNA-mRNA intersected, including 3 mRNA and 2 miRNAs. D Correspondence diagram of hub gene and miRNA. The hub gene and miRNA regulatory network consists of 5 Nodes (3 hub genes, 2 miRNAs) and 3 Edges. Circles (red up-regulated genes, green down-regulated genes) represent hub genes, and rectangles represent differential miRNA

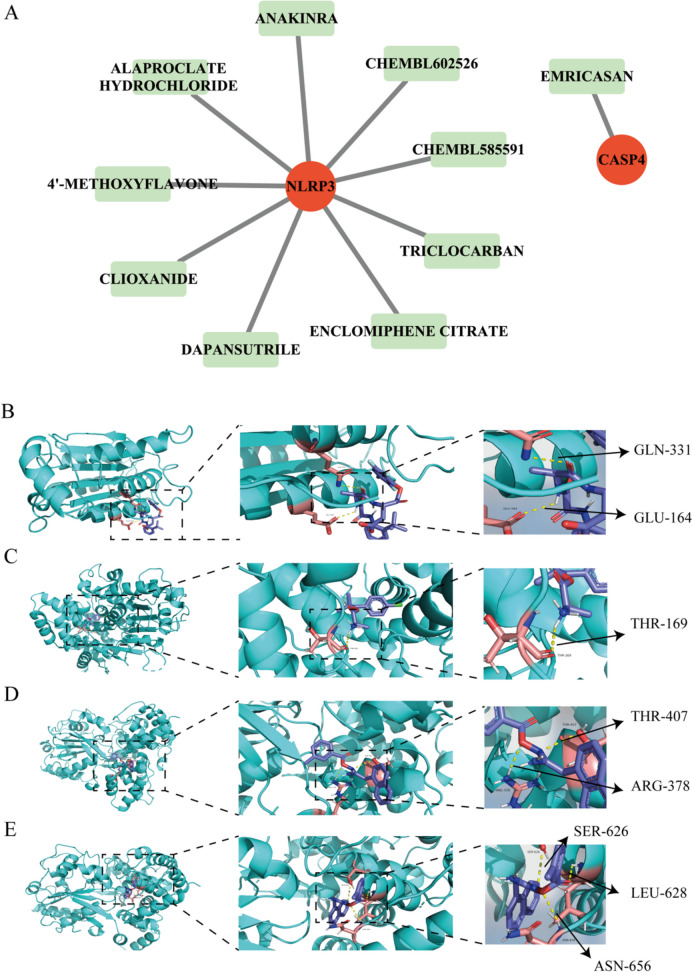

Use of Hub Genes to Predict Small Molecule Drugs

As shown in Fig. 6A, CASP4 predicted one small molecule drug (EMRICASAN), and NLRP3 predicted nine small molecule drugs (such as ALAPROCLATE HYDROCHL ORIDE, DAPANSUTRILE, CHEMBL602526). CASP4 has a strong binding energy with EMRICASAN (− 6.1 kcal/mol). NLRP3 has a strong binding energy (− 8.5 kcal/mol) with ALAPROCLATE HYDROCHLORIDE (− 6.4 kcal/mol), CHEMBL602526 (− 8.4 kcal/mol), and ANAKINRA (Fig. 6B–E).

Fig. 6.

Small molecule drug prediction for SCI therapy. A Correspondence diagram of hub gene and small molecule drug. The circles represent the hub gene, and the long light green squares represent small molecule drugs. These results show the molecular docking of hub genes with drugs that have an Interaction Score of > 1. CASP4 has strong binding energy (less than − 5 kcal/mol) with EMRICASAN, while NLRP3 has strong binding energies (less than − 5 kcal/mol) with ALAPROCLATE HYDROCHLORIDE, CHEMBL602526, and ANAKINRA. Both CASP4 and NLRP3 predicted one or more small molecule drugs, while other hub genes did not predict the corresponding small molecule drugs. Potential therapeutic drugs interact with the hub gene, which could help develop new therapeutic targets for SCI therapy. B 3D structure of CASP4 proteins and EMRICASAN small molecule therapy, as well as local magnification of the structure of amino acid residues (GLN-331, GLU-164) docked to the drug. C 3D structure of NLRP3 proteins and ALAPROCLATE HYDROCHLORIDE small molecule therapy, as well as local magnification of the structure of amino acid residues (THR-169) docked to the drug. D 3D structure of NLRP3 proteins and CHEMBL602526 small molecule therapy, as well as local magnification of the structure of amino acid residues (THR-407, ARG-378) docked to the drug. E 3D structure of NLRP3 proteins and ANAKINRA HYDROCHLORIDE small molecule therapy, as well as local magnification of the structure of amino acid residues (SER-626,LEU-628 and ASN-656) docked to the drug

Expression Analysis of Different Data Sets

In GSE45376, the human central genes (CASP4, NAIP, NLRC4, NLRP3) were transformed into mouse genes (Casp4, Naip2, Nlrc4, Nlrp3). The expression of Naip2 and Nlrc4 was relatively high in samples taken on day seven after SCI (Fig. 7A). In GSE93561, the human central genes CASP4, NAIP, and NLRP3 can correspond to the mouse genes Casp4, Naip2, and Nlrp3. Naip2, Nlrp3, and Casp4 expressions in SCI samples were significantly higher than in HC samples (Fig. 7B).

Fig. 7.

Verification of the hub gene expression in different datasets. A The expression of hub genes In GSE45376. In the GSE45376 dataset, the genetic differences of Casp4, Naip2, Nlrc4, and Nlrp3 in Day 7 samples and control samples (n = 9) after SCI were analyzed. The expression levels of Naip2 and Nlrc4 were relatively higher in day 7 samples after SCI. B The expression of hub genes in GSE93561. In the validation set (GSE93561), the genetic differences of Casp4, Naip2, and Nlrp3 in SCI and HC (n = 3) were analyzed. The expressions of Naip2, Nlrp3, and Casp4 in SCI samples were significantly higher than those in HC samples. ∗ p < 0.05, ∗ ∗ p < 0.01, ∗ ∗ ∗ p < 0.001 and ns = not significant

Validation of Above Results Through qRT-PCR

Since the expression of GSDMD is not observed in mice, we validated four other genes (Casp4, Naip2, Nlrc4, and Nlrp3). qRT-PCR was performed on 3 SCI and paired 3 Sham tissues. Then, mRNA of four genes (Casp4, Naip2, Nlrc4, and Nlrp3) were detected in SCI and Sham samples by qRT-PCR. The results are consistent with the expectation. Four genes (Casp4, Naip2, Nlrc4, and Nlrp3) expression were significantly higher in SCI than in Sham group (Fig. 8B).

Fig. 8.

Verification of the hub gene expression in a mouse SCI model. A Schematic diagrams. The mice underwent T10 laminectomy using a midline skin incision between T9 and T11, and a midline spinal contuse was performed with a force of 0.7 N at the exposed T10 level. 2 h (2 h), 2 days (2d), and 7 days (7d) after surgery, RNA was extracted from the injured spinal cord and peripheral blood of mice for PCR testing. By Figdraw version 2.0. B The expression of Casp4, Naip2, Nlrp3, and Nlrc4 in peripheral blood samples at 2 h (2 h), 2 days (2d), and 7 days (7d) after SCI in a mouse model was analyzed. The expression levels of Casp4, Naip2, Nlrp3, and Nlrc4 at 2 days (2d) and 7 days (7d) after SCI were relatively higher than Sham. C The expression of Casp4, Naip2, Nlrp3, and Nlrc4 in spinal cord samples at 2 days (2d) and 7 days (7d) after SCI in a mouse model was analyzed. The expression levels of Casp4, Naip2, Nlrp3, and Nlrc4 at 2 days and 7 days after SCI were relatively higher than Sham. D Casp4, Naip2, Nlrp3, and Nlrc4 expression in spinal cord samples and peripheral blood samples were compared at 2 h (2 h), 2 days (2d), and 7 days (7d) after SCI. There was no significant difference in the expression of four genes between the two groups at 2 h and 2 days after injury. On the 7th day of injury, the expression of Casp4 was significantly different between the two samples. Data are presented as means ± SD, ∗ p < 0.05, ∗ ∗ p < 0.01, ∗∗∗ p < 0.001, and ns = not significant (n = 3)

Discussion

Spinal cord injury is a common central nervous system disease in clinical practice, and there are currently no effective treatment options. The role of inhibiting cell death in secondary injury has become an important research direction in treating spinal cord injury. PANoptosis is an inflammatory programmed cell death (PCD) pathway with key features of pyroptosis and necrotic apoptosis [32]. PANoptosis is involved in the development of spinal cord injury [33]. As the interactions between the various PCD pathways become clearer, targeting only one pathway that regulates cell death without considering the others that follow cannot achieve the desired therapeutic effect. However, inhibition of the activation of the formation of the PANoptosome complex and PANoptosis can effectively prevent the PCD pathway [6, 34]. Therefore, interfering with or blocking key sensors in the PANoptosis pathway or inhibiting the formation of the PANoptosome complex may be an effective treatment to inhibit secondary injury after spinal cord injury.

We believe that even in different models of spinal cord injury, there may be shared and collective molecular mechanisms of injury, and identifying these mechanisms can provide new ideas for the treatment and prognosis of spinal cord injury. In this study, we retrieved transcriptome datasets from the GEO database, combined with GSE93561 and GSE45376 gene expression profiles, and performed DEGs analysis for spinal cord injury, combined with difference analysis and machine learning. These were chosen because they use spinal cord tissue, providing direct insight into gene expression and reducing confounding factors. Although human spinal cord samples are difficult to obtain, mouse samples are more accessible and facilitate experimental validation, with R tools allowing for the translation of these findings to human genes. Five central genes related to PANoptosis in spinal cord injury were identified: CASP4, GSDMB, NAIP, NLRC4, and NLRP3. All five hub genes were enriched in phagocytosis mediated by FC GAMMA R, and 11 kinds of immune cells, such as mast cells and γδ T cells, were significantly increased after SCI. The analysis predicted that one CASP4 inhibitor (EMRICASAN) and nine NLRP3 inhibitors (such as ALAPROCLATE HYDROCHL ORIDE, DAPANSUTRILE, CHEMBL602526) might be small molecule drugs for the treatment of spinal cord injury.

Among the five hub genes, CASP4, GSDMB, NLRC4, and NLRP3 were apoptosis-related genes, while NAIP were anti-apoptosis-related genes. CASP4 activates the inflammasome and increases pro-inflammatory processes. CASP4 is involved in cell death after spinal cord injury [35]. As a receptor for cytoplasmic lipoproteins in SCI, it plays a role in the formation and pyrolysis of atypical inflammasome pathways. CASP4 plays a similar role in this process, and its activation induces GSDMD-dependent focal intensity and interleukin-18 processing, further aggravating inflammatory damage. Inhibition of CASP4 inhibits spinal cord injury by improving NLRP3 inflammatory anti-inflammatory. Interestingly, inhibiting CASP4 also reduced levels of apoptosis-associated proteins and apoptosis-associated genes, such as CASP3 and Bcl2 [36], suggesting that drugs targeting these genes may be a potential strategy to treat spinal cord injury by inhibiting NLRP3 inflammasome formation and GSDMD-induced scorchability. GSDMB (Gasdermin B) belongs to the GSDM protein family, which can regulate its lipid binding and pore formation activities through different intramolecular domain mechanisms and participate in pyroptosis [37]. GSDMB is associated with many inflammatory diseases. GSDMB can release N-terminal pore through caspase hydrolysis to form a domain and destroy the cell membrane, thus triggering cell lysis. The rupture of the cell membrane causes the release of inflammatory factors, which begin a new round of heat death by binding to receptors on the surrounding cell membrane. NLRC4 is a member of the inflammasome NLR family CARD domain-containing protein 4 [38]. NLRC4 binds to ligands to form polyproteomic complexes, which activate NLRC4 inflammatory body signals, collect, cut, and activate Caspase-1. Activated Caspase-1 can shear the precursors of IL-1β and IL-18 and promote the release of mature IL-1β and IL-18. Activates IL-1β and IL-18 and releases them into tissues outside the cell to participate in the subsequent inflammatory cascade. NLRP3(NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3) is an inflammasome widely distributed in the central nervous system [39]. Studies have found that the expression of NLRP3 inflammasome is significantly up-regulated after spinal cord injury, and inhibition of NLRP3 inflammasome can improve motor function after SCI [40]. The NLRP3 inflammator provides a platform for the autocatalytic hydrolysis of procaspase-1, converting the latter into biologically active caspase-1. Mature caspase-1 further cuts IL-1β and IL-18, converting them into live IL-1β and IL-18 and releasing them into tissues outside the cell to participate in the subsequent inflammatory cascade. The intense inflammatory response causes the death of neurons and oligodendrocytes in the spinal cord. Because various cells in the central nervous system express IL-1β and IL-18 receptors, they are susceptible to the NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammatory signaling pathway. Neuronal apoptosis inhibitory protein (NAIP) is a member of the apoptosis-inhibiting protein family, a group of highly conserved apoptosis-inhibiting proteins [41]. NAIP plays an anti-apoptosis-inhibiting role by inhibiting cysteine aspartic protease, participating in tumor necrosis factor receptor-mediated signal transduction and other pathways, and is closely related to neurological diseases. NAIP plays an essential role in many neurological diseases [42, 43]. Studies showed that typical apoptotic changes occurred in the frontal cortex of rats after chronic cerebral ischemia. There is much evidence that the death of nerve cells after ischemia is regulated by caspases. Studies suggest that NAIP is involved in the apoptosis of nerve cells in the brains of rats with chronic ischemia [44]. NAIP is a marker of activating the anti-apoptosis mechanism in the spinal cord. The present study was consistent with the above and validated that CASP4, NAIP, NLRC4, and NLRP3 were activated after SCI. Animal experimental results demonstrated a progressive increase in the expression levels of Casp4, Naip2, Nlrp3, and Nlrc4 in both the spinal cord and peripheral blood at 2 h, 2 days, and 7 days post-spinal cord injury. This pattern may be associated with the peak expression of the inflammatory immune microenvironment following injury [45]. Notably, we observed no significant differences in the expression levels of Naip2, Nlrp3, and Nlrc4 between peripheral blood and spinal cord across different stages of injury. This finding suggests the potential for detecting the activation of PANoptosis genes in various tissues post-SCI. Future research could focus on confirming the activation of these genes in the spinal cords of patients by analyzing gene expression in peripheral blood, thus informing treatment strategies. However, due to time limitations, we did not investigate gene expression changes beyond the 7-day post-injury mark. Interestingly, at day 7 post-SCI, Casp4 expression exhibited differential patterns between peripheral blood and spinal cord samples, implying that gene expression dynamics may vary across tissues over time. Exploring the correlation of gene expression levels across different tissues could yield novel diagnostic strategies for monitoring PANoptosis within the spinal cord.

Immune cells recruit to the focal center of injury and are closely related to the progression of spinal cord injury [46]. We used CIBERSORT to evaluate infiltrated immune cells after spinal cord injury [47]. By difference analysis, 13 types of immune infiltrating cells were mainly mast cells, immature dendritic cells, and macrophages after SCI. LASSO analysis also identified 11 key immune infiltrating cells, including γδ T cells, neutrophils, and regulatory T cells. According to the literature, DC maturation is significantly reduced in patients with spinal cord injury. Studies have found that Tregs are essential factors in the immune system, which play an immunosuppressive role by regulating various mechanisms, thus promoting the repair of the damaged nervous system [48]. Macrophages secrete cytokines that regulate signaling pathways and promote functional recovery after spinal cord injury. One study showed that reducing neutrophil activity was beneficial in mitigating the harmful effects of neutrophil outbreaks. Our analysis found that CASP4 was positively associated with neutrophils, and NLRC4 had the strongest negative association with activated CD8 T cells. Therefore, CASP4 and NLRC4 may participate in the occurrence and progression of SCI by increasing positively related cells or decreasing negatively related cells. More research on the relationship between biomarkers and immune cells is needed to confirm these suspicions. After spinal cord injury, local tissue damage and many cell debris and decomposition products appear in the spinal cord injury area, which induces secondary cell death, inhibits axon regeneration, and hinders nerve function repair. FC-GAMMA-R (Fc-γR) is a particular receptor that mainly exists on immune cells’ surface, such as macrophages, dendritic cells, and NK cells. Fc-γR can activate the phagocytosis of immune cells, thus playing a role in immune regulation and maintaining body health [49]. Phagocytosis mediated by Fc-γR is one of the most direct and effective immune clearance methods of the immune system. In immune response, when the recognized IgG binds to specific antigens, Fc-γR is activated, and the phagocytic behavior of macrophages, dendritic cells, NK cells, phagocytic pathogens, cellular garbage, tumor cells, etc. is regulated. This phagocytosis is very effective and can quickly remove disease-related substances and protect the body from harm. At the same time, as a crucial inflammatory stimulator, myelin fragments can recruit many monocytes into the spinal cord injury area and then differentiate into mature macrophages (BMDMs). BMDMs play an essential physiological role as specialized phagocytes, responsible for phagocytosis and removal of apoptotic cell debris and myelin debris, which is critical for creating a regenerative microenvironment that promotes damage repair [50]. In addition, we also found that CASP4 is related to “macrophages,” GSDMB is significantly enriched in “lysosomes,” NAIP and NLRC4 are significantly enriched in “reactive oxygen metabolism,” and NLRP3 is significantly enriched in “PPAR signaling pathway,” all of which are related to injury and repair after spinal cord injury.

Abnormal gene expression is closely related to the occurrence and development of spinal cord injury. However, little is known about the interaction of these abnormally expressed genes and the molecular mechanisms that play a role in the injury response. Therefore, it is of great significance to explore the molecular regulation mechanism after spinal cord injury. Through analysis, the TF-hub gene network and miRNA-hub gene were established. NLRP3 is regulated by STAT3, CEBPB, and PPARG transcription factors, and NLRP3 is regulated by hsa-mir-193b-3p. Therefore, we will next study these hub genes and transcriptional regulators to see if they have a role and how they are regulated to play a protective role after spinal cord injury in animals.

Conclusions

By analyzing five genes (CASP4, GSDMB, NAIP, NLRC4, and NLRP3) and drug networks, the molecular mechanism of the role of key genes related to PANoptosis in spinal cord injury can be clarified, providing potential directions for the diagnosis and treatment of spinal cord injury. In addition, we need to explain the shortcomings of our study, such as further validation of the expression of these key genes in vitro experiments. Moreover, we will next investigate how to regulate these hub genes and transcriptional regulators in the hope of playing a protective role after spinal cord injury.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors will thank all the colleagues of Department of Orthopedics of Chinese PLA General Hospital and Department of Neurosurgery of Jinling Hospital for their great help.

Author Contributions

Bo Li and Tao Li were responsible for conceptualization, methodology, and drafting the initial manuscript. Yibo Cai contributed to analysis, investigation, and manuscript editing. Junyao Cheng and Chuyue Zhang provided resources. Jianheng Liu and Keran Song offered supervision and critical review. Zheng Wang managed the project and acquired funding. Xinran Ji finalized the manuscript with administrative support. All authors reviewed and approved the submitted version.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (82172392 and 82372499) and Natural Science Foundation of Beijing (L212049).

Data Availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics Approval

The animal studies were carried out in accordance with Committee of Chinese PLA General Hospital, IACUC of PLAGH on the use of Institutional Animal Care and Use (Ethics Approval No. SQ2024803).

Competing Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Bo Li, Tao Li, and Yibo Cai contributed equally to this work.

Contributor Information

Keran Song, Email: song.ortho@163.com.

Zheng Wang, Email: wangzheng301@163.com.

Xinran Ji, Email: 18510622211@163.com.

References

- 1.Guan B, Anderson DB, Chen L, Feng S, Zhou H (2023) Global, regional and national burden of traumatic brain injury and spinal cord injury, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. BMJ Open 1310:e075049. 10.1136/bmjopen-2023-075049 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guha L, Kumar H (2023) Drug repurposing for spinal cord injury: progress towards therapeutic intervention for primary factors and secondary complications. Pharmaceut Med 376:463–490. 10.1007/s40290-023-00499-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wang XB, Zhou LY, Chen XQ, Li R, Yu BB, Pan MX, Fang L, Li J et al (2023) Neuroprotective effect and possible mechanism of edaravone in rat models of spinal cord injury: a protocol for a systematic review and meta-analysis. Syst Rev 121:177. 10.1186/s13643-023-02306-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.He L, Liu L, Xu D, Tu Y, Yang C, Zhang M, Wang H, Nong X (2024) Deficiency of N6-methyladenosine demethylase ALKBH5 alleviates ultraviolet B radiation-induced chronic actinic dermatitis via regulating pyroptosis. Inflammation 471:159–172. 10.1007/s10753-023-01901-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Meng Q, Ding B, Ma P, Lin J (2023) Interrelation between programmed cell death and immunogenic cell death: take antitumor nanodrug as an example. Small Methods 75:e2201406. 10.1002/smtd.202201406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Christgen S, Zheng M, Kesavardhana S, Karki R, Malireddi RKS, Banoth B, Place DE, Briard B et al (2020) Identification of the PANoptosome: a molecular platform triggering pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis (PANoptosis). Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10:237. 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Samir P, Malireddi RKS, Kanneganti TD (2020) The PANoptosome: a deadly protein complex driving pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis (PANoptosis). Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10:238. 10.3389/fcimb.2020.00238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Malireddi RKS, Kesavardhana S, Kanneganti TD (2019) ZBP1 and TAK1: master regulators of NLRP3 inflammasome/pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis (PAN-optosis). Front Cell Infect Microbiol 9:406. 10.3389/fcimb.2019.00406 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Karki R, Sharma BR, Lee E, Banoth B, Malireddi RKS, Samir P, Tuladhar S, Mummareddy H et al (2020) Interferon regulatory factor 1 regulates PANoptosis to prevent colorectal cancer. JCI Insight 5(12). 10.1172/jci.insight.136720 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Place DE, Lee S, Kanneganti TD (2021) PANoptosis in microbial infection. Curr Opin Microbiol 59:42–49. 10.1016/j.mib.2020.07.012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yan WT, Yang YD, Hu XM, Ning WY, Liao LS, Lu S, Zhao WJ, Zhang Q et al (2022) Do pyroptosis, apoptosis, and necroptosis (PANoptosis) exist in cerebral ischemia? Evidence from cell and rodent studies. Neural Regen Res 178:1761–1768. 10.4103/1673-5374.331539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fritsch M, Günther SD, Schwarzer R, Albert MC, Schorn F, Werthenbach JP, Schiffmann LM, Stair N et al (2019) Caspase-8 is the molecular switch for apoptosis, necroptosis and pyroptosis. Nature 5757784:683–687. 10.1038/s41586-019-1770-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karki R, Sundaram B, Sharma BR, Lee S, Malireddi RKS, Nguyen LN, Christgen S, Zheng M et al (2021) ADAR1 restricts ZBP1-mediated immune response and PANoptosis to promote tumorigenesis. Cell Rep 373:109858. 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.109858 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang W, Zhu S, Liu X, Huang L, Han Y, Han Q, Xie D, Zeng H (2016) Cholinergic anti-inflammatory pathway involves in the neuroprotective effect of huperzine A on sepsis-associated encephalopathy. Zhonghua Wei Zhong Bing Ji Jiu Yi Xue 285:450–454 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abe J, Morrell C (2016) Pyroptosis as a regulated form of necrosis: PI+/annexin V-/high caspase 1/low caspase 9 activity in cells = pyroptosis? Circ Res 11810:1457–1460. 10.1161/circresaha.116.308699 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Los M, Mozoluk M, Ferrari D, Stepczynska A, Stroh C, Renz A, Herceg Z, Wang ZQ et al (2002) Activation and caspase-mediated inhibition of PARP: a molecular switch between fibroblast necrosis and apoptosis in death receptor signaling. Mol Biol Cell 133:978–988. 10.1091/mbc.01-05-0272 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang Y, Li Q, Zhu R, Li S, Xu X, Shi X, Yin Z (2022) Identification of ferroptotic genes in spinal cord injury at different time points: bioinformatics and experimental validation. Mol Neurobiol 599:5766–5784. 10.1007/s12035-022-02935-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Guha L, Singh N, Kumar H (2023) Different ways to die: cell death pathways and their association with spinal cord injury. Neurospine 202:430–448. 10.14245/ns.2244976.488 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shi Z, Yuan S, Shi L, Li J, Ning G, Kong X, Feng S (2021) Programmed cell death in spinal cord injury pathogenesis and therapy. Cell Prolif 543:e12992. 10.1111/cpr.12992 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang X, Sun R, Chan S, Meng L, Xu Y, Zuo X, Wang Z, Hu X et al (2022) PANoptosis-based molecular clustering and prognostic signature predicts patient survival and immune landscape in colon cancer. Front Genet 13:955355. 10.3389/fgene.2022.955355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wei S, Chen Z, Ling X, Zhang W, Jiang L (2023) Comprehensive analysis illustrating the role of PANoptosis-related genes in lung cancer based on bioinformatic algorithms and experiments. Front Pharmacol 14:1115221. 10.3389/fphar.2023.1115221 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wu J, Zhang F, Zheng X, Zhang J, Cao P, Sun Z, Wang W (2022) Identification of renal ischemia reperfusion injury subtypes and predictive strategies for delayed graft function and graft survival based on neutrophil extracellular trap-related genes. Front Immunol 13:1047367. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1047367 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Volpi EM, Ramirez-Ortega MC, Carrillo JF (2023) Editorial: Recent advances in papillary thyroid carcinoma: progression, treatment and survival predictors. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 14:1163309. 10.3389/fendo.2023.1163309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Waespe N, Mlakar SJ, Dupanloup I, Rezgui MA, Bittencourt H, Krajinovic M, Kuehni CE, Nava T et al (2023) A novel integrative multi-omics approach to unravel the genetic determinants of rare diseases with application in sinusoidal obstruction syndrome. PLoS One 184:e0281892. 10.1371/journal.pone.0281892 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen T, Wang Y, Tian L, Guo X, Xia J, Wang Z, Song N (2022) Aberrant gene expression profiling in men with sertoli cell-only syndrome. Front Immunol 13:821010. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.821010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhong M, Zhu E, Li N, Gong L, Xu H, Zhong Y, Gong K, Jiang S et al (2023) Identification of diagnostic markers related to oxidative stress and inflammatory response in diabetic kidney disease by machine learning algorithms: evidence from human transcriptomic data and mouse experiments. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne) 14:1134325. 10.3389/fendo.2023.1134325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peng F, Muhuitijiang B, Zhou J, Liang H, Zhang Y, Zhou R (2023) An artificial neural network model to diagnose non-obstructive azoospermia based on RNA-binding protein-related genes. Aging (Albany NY) 158:3120–3140. 10.18632/aging.204674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xie C, Yin Z, Liu Y (2022) Analysis of characteristic genes and ceRNA regulation mechanism of endometriosis based on full transcriptional sequencing. Front Genet 13:902329. 10.3389/fgene.2022.902329 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yang YC, Zhang MY, Liu JY, Jiang YY, Ji XL, Qu YQ (2022) Identification of ferroptosis-related hub genes and their association with immune infiltration in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease by bioinformatics analysis. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis 17:1219–1236. 10.2147/copd.S348569 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yu H, Liu Y, Li C, Wang J, Yu B, Wu Q, Xiang Z, Feng S (2020) Bioinformatic analysis of neuroimmune mechanism of neuropathic pain. Biomed Res Int 2020:4516349. 10.1155/2020/4516349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dong H, Li X, Cai M, Zhang C, Mao W, Wang Y, Xu Q, Chen M et al (2021) Integrated bioinformatic analysis reveals the underlying molecular mechanism of and potential drugs for pulmonary arterial hypertension. Aging (Albany NY) 1310:14234–14257. 10.18632/aging.203040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.González-Rodríguez P, Fernández-López A (2023) PANoptosis: new insights in regulated cell death in ischemia/reperfusion models. Neural Regen Res 182:342–343. 10.4103/1673-5374.343910 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Xie L, Wu H, Shi W, Zhang J, Huang X, Yu T (2024) Melatonin exerts an anti-panoptoic role in spinal cord ischemia-reperfusion injured rats. Adv Biol (Weinh) 81:e2300424. 10.1002/adbi.202300424 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Uysal E, Dokur M, Kucukdurmaz F, Altınay S, Polat S, Batcıoglu K, Sezgın E, SapmazErçakallı T et al (2022) Targeting the PANoptosome with 3,4-methylenedioxy-β-nitrostyrene, reduces PANoptosis and protects the kidney against renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. J Invest Surg 3511–12:1824–1835. 10.1080/08941939.2022.2128117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Wang C, Ma H, Zhang B, Hua T, Wang H, Wang L, Han L, Li Q et al (2022) Inhibition of IL1R1 or CASP4 attenuates spinal cord injury through ameliorating NLRP3 inflammasome-induced pyroptosis. Front Immunol 13:963582. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.963582 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Geller J, Petak I, Szucs KS, Nagy K, Tillman DM, Houghton JA (2003) Interferon-gamma-induced sensitization of colon carcinomas to ZD9331 targets caspases, downstream of Fas, independent of mitochondrial signaling and the inhibitor of apoptosis survivin. Clin Cancer Res 917:6504–6515 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Broz P, Pelegrín P, Shao F (2020) The gasdermins, a protein family executing cell death and inflammation. Nat Rev Immunol 203:143–157. 10.1038/s41577-019-0228-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu X, Yang ZH, Wu J, Han J (2023) Ribosome-rescuer PELO catalyzes the oligomeric assembly of NOD-like receptor family proteins via activating their ATPase enzymatic activity. Immunity 565:926-943.e927. 10.1016/j.immuni.2023.02.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mangan MSJ, Olhava EJ, Roush WR, Seidel HM, Glick GD, Latz E (2018) Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome in inflammatory diseases. Nat Rev Drug Discov 178:588–606. 10.1038/nrd.2018.97 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jiang W, Li M, He F, Zhou S, Zhu L (2017) Targeting the NLRP3 inflammasome to attenuate spinal cord injury in mice. J Neuroinflammation 141:207. 10.1186/s12974-017-0980-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Fu J, Schroder K, Wu H (2024) Mechanistic insights from inflammasome structures. Nat Rev Immunol 247:518–535. 10.1038/s41577-024-00995-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kano O, Tanaka K, Kanno T, Iwasaki Y, Ikeda JE (2018) Neuronal apoptosis inhibitory protein is implicated in amyotrophic lateral sclerosis symptoms. Sci Rep 81:6. 10.1038/s41598-017-18627-w [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Savad S, Ashrafi MR, Samadaian N, Heidari M, Modarressi MH, Zamani G, Amidi S, Younesi S et al (2023) A comprehensive overview of SMN and NAIP copy numbers in Iranian SMA patients. Sci Rep 131:3202. 10.1038/s41598-023-30449-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Xu Q, Zhao B, Ye Y, Li Y, Zhang Y, Xiong X, Gu L (2021) Relevant mediators involved in and therapies targeting the inflammatory response induced by activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome in ischemic stroke. J Neuroinflammation 181:123. 10.1186/s12974-021-02137-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Loveless R, Bloomquist R, Teng Y (2021) Pyroptosis at the forefront of anticancer immunity. J Exp Clin Cancer Res 401:264. 10.1186/s13046-021-02065-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Tang H, Gu Y, Jiang L, Zheng G, Pan Z, Jiang X (2022) The role of immune cells and associated immunological factors in the immune response to spinal cord injury. Front Immunol 13:1070540. 10.3389/fimmu.2022.1070540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cao L, Li Q (2022) Revealing potential spinal cord injury biomarkers and immune cell infiltration characteristics in mice. Front Genet 13:883810. 10.3389/fgene.2022.883810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Li C, Jiang P, Wei S, Xu X, Wang J (2020) Regulatory T cells in tumor microenvironment: new mechanisms, potential therapeutic strategies and future prospects. Mol Cancer 191:116. 10.1186/s12943-020-01234-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Rosales C (2017) Fcγ receptor heterogeneity in leukocyte functional responses. Front Immunol 8:280. 10.3389/fimmu.2017.00280 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Yang H, Song L, Sun B, Chu D, Yang L, Li M, Li H, Dai Y et al (2021) Modulation of macrophages by a paeoniflorin-loaded hyaluronic acid-based hydrogel promotes diabetic wound healing. Mater Today Bio 12:100139. 10.1016/j.mtbio.2021.100139 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.