Abstract

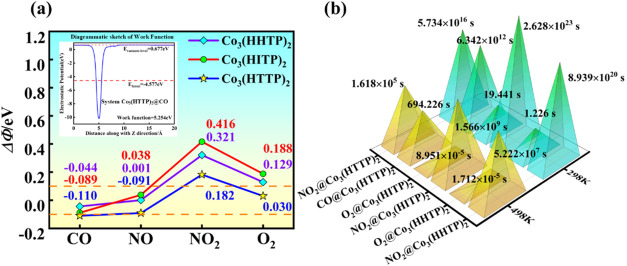

Combustion processes produce noxious gases, causing environmental pollution and health risks, which require high-performance sensing materials. Herein, metal–organic framework structures (MOFs) Co3(HXTP)2 (X = H, I, T) with superior conductivity and sensing properties are employed based on density functional theory (DFT) calculations. Adsorption energies of Co3(HXTP)2@gas are exceptionally outstanding in the realm of gas-sensitive material. Co3(HXTP)2 bases exhibit a responsive behavior toward the gas by comparing the work function and have a short recovery time (τ). Our results demonstrate that Co3(HHTP)2 (τ = 1.226 s) and Co3(HITP)2 (τ = 19.441 s) can serve as gas-sensitive materials for detecting O2 at 298 K, whereas Co3(HTTP)2 (τ = 694.226 s) can be used for CO at 498 K. Moreover, excellent gas-sensitive properties arise from chemical interactions, such as the electron “donation–backdonation” mechanism between gas and substrate (σ → 3dz2 and 3dxz, 3dyz → π*), and the simultaneous refilling of the d-suborbitals (3dz2 → 3dxz, 3dyz) within Co atoms. The descriptor φ demonstrates excellent predictive capability for both the adsorption and response of gas-sensitive materials. Our findings provide valuable insights into the design of gas-sensitive materials in this class of TM3(HXTP)2 structures.

Introduction

Gases in the combustion process (GCPs), including O2, CO, CO2, NO, and NO2, are among the most common atmospheric components. Specifically, excessive O2 intake can accelerate aging in humans. Combustion products such as NO and NO2 contribute to acid rain and smog formation, leading to severe soil and water pollution. The presence of CO causes gas poisoning. CO2 plays a prominent role in global greenhouse effects. Excessive inhalation of GCPs not only poses significant risks to human cognitive function but also jeopardizes life itself. Consequently, the accurate identification and quantification of these gases are of paramount importance for the surveillance of the ecological environment and the safeguarding of human health.

To accurately and quickly monitor the aforementioned gases, a great deal of studies have been conducted on various gas-sensitive materials,1,2 including metal oxide,3−5 carbon-based materials,6−8 and transition metal dichalcogenides9−12 (TMDs). However, these materials possess certain limitations to some extent. Due to the strong polarity of oxygen, metallic oxide materials exhibit robust adsorption against specific gases but require high temperatures for activation, thereby resulting in increased energy consumption and rendering them unsuitable for mobile devices. Carbon-based materials such as graphene lack polar active sites, leading to limited sensor sensitivity and selectivity. TMDs are effortless to degradation caused by adsorbed gases, leading to the irreversible depletion of raw materials. Due to the various defects in these materials, there is an urgent need to identify more suitable gas-sensing materials.

Metal–organic framework structures (MOFs) have a wide range of physical and chemical properties, such as the large specific surface area and high porosity, as well as a wealth of active sites due to their diverse combinations of polar atoms.13−20 To date, the synthesis of MOFs can be realized through simple room-temperature preparation via a top-down solution process. The easily controllable and remarkably efficient catalytic activity bestows MOF materials with significant research and application value in the pharmaceutical and chemical industries. Nevertheless, most MOFs exhibit low electrical conductivity,18,21 which significantly influences the performance of electrochemical gas sensors. Pentyala and his colleagues16 found that the original MOF-74 has poor electrical conductivity. After functional modification with Mg and ethylene diamine, the material not only improved its electrical conductivity but also enhanced its sensing ability toward CO2. As a result, it is interesting to find a MOF material with good electrical conductivity and explore its potential as a gas-sensitive material.

Recently, a novel MOF material TM3(HXTP)2 (X = H, I, T) has already been synthesized22−33 and exhibited potential for room-temperature conductivity.22−36 The single-layer TM3(HXTP)2 structure is predominantly constructed from metal atoms and organic ligands HITP (C18H12N6), HHTP (C18H6O6), and HTTP (C18H6S6) interconnected through covalent bonds. The favorable energy matching between the linker and the metal orbitals facilitates the extension of the π-conjugated system, which promotes effective in-plane delocalization of charge carriers and endows outstanding electrical conductivity. Moreover, the periodic cavity with a size of approximately 22 Å theoretically enables the encapsulation of a greater number of gas molecules within superlarge pores.

TM3(HXTP)2 is widely used for its excellent electrocatalytic performance, but there are also some experiments in the field of gas-sensitive materials that confirm its superior gas-sensing properties. Yao et al.28 reported that Cu3(HHTP)2 thin films exhibit outstanding room-temperature sensing performance for the selective detection of NH3 with a rapid response time, excellent long-term stability, and reproducibility. Campbell et al.37 successfully utilized Cu3(HHTP)2, Cu3(HITP)2, and Ni3(HITP)2 materials for the detection of volatile organic gases (VOCs), encompassing five functional groups such as alcohols, aromatics, ketones, amines, and alkanes. Despite all of these applications, the gas-sensing characteristics of TM3(HXTP)2 toward combustion process gases have never been investigated. Therefore, it is necessary to reveal the potential application of TM3(HXTP)2 (X = H, I, T) as a new kind of gas-sensitive material for GCPs.

In this study, taking advantage of the excellent electrical conductivity exhibited by Co3(HXTP)2,27,30,31,33−35,38 we explore their feasibility as gas-sensitive materials for detecting GCPs. The gas-sensitive performance of these materials was evaluated through their adsorption, response, and desorption behaviors with respect to GCPs. To further elucidate the origins of their gas-sensing properties, we performed a detailed analysis of each material’s electronic structures. Results indicate that Co3(HHTP)2 and Co3(HITP)2 are effective for detecting O2, while CO adsorption exhibits favorable electronic and geometric characteristics on the Co3(HTTP)2 monolayer, suggesting its potential as a highly responsive material for gas-sensing applications. Furthermore, we developed a new descriptor φ to quantify the response and adsorption properties of gas-sensitive materials. Our results can provide a theoretical basis for future experimental validation, thereby promoting the application of Co3(HXTP)2 materials in the detection of gases from combustion processes. This comprehensive investigation underscores the potential of Co3(HXTP)2-based materials for GCP gas detection and offers valuable insights into the application of TM3(HXTP)2 as an effective gas sensors.

Computational Details and Methods

In this study, all of the first-principles spin-polarized calculations are performed using the Vienna Ab-initio Simulation Package39 (VASP 5.4.4). The interaction between ions and electrons is described employing projector augmented waves40 (PAW) pseudopotential, while the exchange-correlation potential is determined by utilizing the generalized gradient approximation (GGA) with the Perdew–Burke–Ernzerhof41 (PBE) functional. The DFT-D342 correction of the Grimme scheme is employed to elucidate the van der Waals (vdW) interactions between the gases and substrates. The cutoff energy is set to 520 eV, while criteria of 10–5 eV and 0.02 eV/Å are employed for achieving force and energy convergence in the calculation. To eliminate the interaction brought by the periodic repeating units, a vacuum layer of 15 Å thickness is added in the z direction. The 2 × 2 × 1 and 3 × 3 × 1 k-point meshes generated based on the Monkhorst–Pack scheme were employed for the geometric optimization and calculation of the density of states (DOS) for all systems. Furthermore, the Bader charge analysis is employed to quantitatively analyze the charge transfer between the gas and the substrate. DS-PAW43 2023A software is utilized for ab-initio molecular dynamic44 (AIMD) simulations to determine the thermodynamic stability of Co3(HTTP)2 simulated at 498 K for 10 ps. The initial placement of the gas is optimized by locating it 2 Å7,45 away from the surface. The projected crystal orbital Hamilton populations (pCOHP) are calculated using the LOBSTER 4.1.0 procedure to quantitatively study the bond interaction between atoms.

To evaluate the capturing ability of Co3(HXTP)2, the adsorption energy between gas and substrate is calculated by the following formula:9,46,47

| 1 |

where Egas@Co3(HXTP)2, ECo3(HXTP)2, and Egas represent the total energy of gas@Co3(HXTP)2 adsorption systems, the Co3(HXTP)2, and the adsorbed GCP gas, respectively.

The VESTA software is utilized for visualizing the charge density difference between the gas and the substrate using the subsequent formula:3,6,7

| 2 |

where ρgas@Co3(HXTP)2, ρCo3(HXTP)2, and ρgas are the charge density of the adsorption systems, Co3(HXTP)2, and the adsorbed gas, respectively.

Results and Discussion

Structures of GCPs and Co3(HXTP)2 (X = H, I, T)

For combustion process gases, which mainly contain CO2, CO, O2, NO, and NO2, the optimized structure is shown in Figure 1b, and geometric structure information and physicochemical properties are listed in Table S1. It is noteworthy that O2 exhibits a magnetic moment of 2 μB, and NO and NO2 possess a magnetic moment of 1 μB. Additionally, calculations have been performed for the highest occupied orbital (HOMO) and lowest unoccupied orbital (LUMO) of GCPs, which are presented in Table S1. The HOMO and LUMO band gaps (EL-H) can serve as an indicator of their electron-donating and feedback capabilities to a certain extent. The EL-H width of GCPs follows the order as CO2 (8.108 eV) > CO (6.886 eV) and O2 (6.759 eV) > NO (4.383 eV) > NO2(2.855 eV), suggesting a potential adsorption energy sequence of CO2 < CO and O2 < NO < NO2.

Figure 1.

Optimized structure of (a) Co3(HXTP)2 and (b) GCP gases. (c) Calculated electron localization function (ELF) of Co3(HHTP)2. (d) AIMD simulation for Co3(HTTP)2 at 498 K. (e) Band structure and density of states for Co3(HHTP)2. The Fermi level is set to be zero (denoted as red dotted lines).

Co3(HXTP)2 (X = H, I, T) can be categorized into three types, designated as Co3(HHTP)2, Co3(HITP)2, and Co3(HTTP)2, which, respectively, correspond to X ligand atoms containing O, N, and S. The Co3(HXTP)2 structures are relaxed, as depicted in Figure 1a, consistent with the early reports.34,35,38 The calculated lattice parameters for Co3(HHTP)2 are a = b = 21.50 Å, the average bond lengths of Co-X4 (dCo-X4) center are 1.83 Å, and the magnetic moment (M) are 3.206 μB. In addition, the electron localization function (ELF) diagram in Figure 1c illustrates the formulation of the electron cavity for Co3(HHTP)2 around the Co-X4 center, primarily originating from the unbonded electron pairs of the X ligand atoms, which facilitate gas molecule adsorption and thus are selected as potential adsorption sites. The calculated band structures and density of states (DOS) of Co3(HHTP)2 are presented in Figure 1e and Table S2. Co3(HHTP)2 possesses an almost negligible band gap (Eg) width of approximately 0.017 eV. The calculated lattice parameters for Co3(HITP)2 are a = b = 21.91 Å, the dCo-X4 is 1.83 Å, and the M is 3.067 μB. The ELF diagram is presented in Figure S1a, and band structures and DOS are presented in Figure S3. Co3(HITP)2 exhibits semiconductor behavior with band gap widths of 0.212 eV. Lattice parameters for Co3(HTTP)2 are a = b = 23.22 Å, the dCo-X4 is 2.13 Å, and the M is 2.823 μB. Figure S1b is the ELF diagram, and band structures and DOS are presented in Figure S4 with Eg widths of 0.399 eV. Moreover, ab-initio molecular dynamic (AIMD) simulation was performed to determine the stability of Co3(HTTP)2. As depicted in Figure 1d, Co3(HTTP)2 can well maintain the structural integrity after 10 ps at the high temperature of 498 K, exhibiting remarkable thermodynamic stability. In summary, all Co3(HXTP)2 substrates demonstrate remarkable stability and excellent electrical conductivity.

Adsorption Behaviors of Co3(HXTP)2 (X = H, I, T) on the GCPs

Two adsorption manners were considered in order to evaluate the adsorption behaviors for GCPs, as seen in Figure 2a. NO and CO molecules are adsorbed on the Co3(HXTP)2 surface with the O-terminal (site 2) or N, C-terminal (site 1). CO2, NO2, and the O2 molecules are placed vertically to the substrate surface end with the O atom (site 1) or horizontally (site 2) to the substrate. The optimized structures can be found in Figure S5. It can be seen that upon CO/NO adsorption, the gas molecule can be perpendicular to the monolayer or inclined adsorbed with the C or N atoms pointing to the Co adatom. For the O2 and NO2, they prefer to be inclined adsorbed on the surface accompanied by O binding with the Co adatom. The average bond length of the Co-X center (dCo-X4), and the adsorption height of GCPs (hgas) can be found in Table S3. For the Co-X4 center, the calculated difference of the average bond length of the Co-X center (ΔdCo-X4) ranges from 0.025 to 0.081 Å (see Figure 2b), manifesting that the Co atom is slightly pulled out of the Co3(HXTP)2 plane upon GCPs adsorption. The summarized absorption energies (Eads) of Co3(HXTP)2 to each GCP gases as illustrated in Figure 2c show that the Co3(HXTP)2 has strong chemisorption for CO, NO, and NO2, with Eads ranging from −1.214 to −2.095 eV. And the adsorption energy of GCPs gases exhibits a strong inverse ratio with their EL–H, as previously speculated. The large Eads for GCPs are associated with the newly forming Co–O/C/N bonds (lCo-gas) in Table S4 (ranging from 1.679 to 1.903 Å), which also indicate the strong interaction. In contrast, the O2 molecule possesses a medium adsorption energy (−0.492 to −0.786 eV) on the Co3(HXTP)2. The CO2 adsorption systems with Eads values of −0.134 to −0.149 eV exhibit much weaker interactions and a physical adsorption nature, indicating that the substrate does not provide sufficient anchoring for CO2. Therefore, it should be excluded from consideration for the next studies. Furthermore, the strong interaction between NO2 and the substrate may surpass our expectations, thereby posing a challenge for desorption. Compared with other common gas-sensitive materials, it can be found that the adsorption energy values of Co3(HXTP)2 for CO/NO/NO2/O2 exceed those reported in previous studies as listed in Table 1. The adsorption of GCP gases on two-dimensional surfaces such as MoS2, BC3, and As2C3 is relatively limited. In contrast, the superior adsorption energy of Co3(HXTP)2 can be primarily attributed to its unique charge cavity, which facilitates gas adsorption and enhances chemical interactions with metal atoms. Moreover, our results surpass those achieved through engineering modifications, such as doping or defect introduction, as reported in previous studies. In summary, compared to other two-dimensional surfaces, Co3(HXTP)2 has a more outstanding gas-anchoring ability. The strong adsorption energy is primarily due to the stronger adsorption of gas molecules by the electron cavity, leading to more intense electron-transfer-dominated chemical interactions. Thus, the adsorption behavior analysis shows the practical application of Co3(HXTP)2 sheet as a potential gas sensor.

Figure 2.

(a) Adsorption configurations of GCPs on Co3(HTTP)2. (b) Bar plot represents the change of the average bond length of the Co-X4 center (ΔdCo-X4) and the line plot shows the adsorption height (hgas) of GCPs. (c) Adsorption energies of various adsorption systems.

Table 1. Comparison of the Adsorption Energies of Co3(HTTP)2@CO/NO/NO2/O2 in This Study and in Previous Studies.

| systems | Eads, eV | systems | Eads, eV |

|---|---|---|---|

| Co3(HTTP)2@CO (this work) | –1.467 | Co3(HITP)2@NO2 (this work) | –2.095 |

| Ag-PdSe2@CO46 | –0.714 | MoS2@NO29 | –1.57 |

| Ga-graphene@CO7 | –0.674 | BC3@NO248 | –1.69 |

| Ag-Bi@CO49 | –1.42 | GeBi@NO250 | –1.09 |

| 2D-Mg@CO45 | –0.508 | Au-BSe@NO251 | –1.12 |

| Co3(HTTP)2@NO (this work) | –1.792 | Co3(HITP)2@O2 (this work) | –0.786 |

| In-Ti2O@NO3 | –0.91 | Fe2GeS4(010)@O252 | –0.46 |

| As2C3@NO53 | –0.31 | V3S4@O254 | –0.59 |

| C3.6B@NO55 | –0.57 | N-graphene@O256 | –0.123 |

| Sb-MoTe2@NO57 | –0.74 | bilayer TiS2@O258 | –0.086 |

Intrinsic Mechanism of the Adsorption

The origin of these strong adsorption energies has been elucidated through a deeper-order intrinsic mechanism analysis. Taking Co3(HTTP)2@CO as an example, the spin-polarized total density of states (TDOS) and projected density of states (PDOS) are provided in Figure 3a,b, while Figure S6 displays TDOS for other adsorption systems. Figure 3a clearly demonstrates that the introduction of gas induces a shift in the overall energy levels toward higher energy positions, which can be potentially attributed to the electron flow directed from the substrate to the gas.

Figure 3.

(a) TDOS spectra of Co3(HTTP)2 and Co3(HTTP)2@CO. (b) PDOS of Co_3d and the TDOS of CO molecules before adsorption, the COHP and ICOHP for the Co_3d orbital and C_2p orbital, the PDOS of Co_3d and CO molecules after adsorption. (c) Disparity in the number of electrons between α-dxz, β-dxz, α-dyz, β-dyz, α-dz2, and β-dz2 orbitals, and the total number of electron changes for 3dxz (Sum-dxz), 3dyz (Sum-dyz), and 3dz2 (Sum-dz2) orbitals.

The first row in Figure 3b shows four characteristic orbitals, namely, 4σ*, 1π, 5σ, and 2π* in free CO molecular within the range of −6 to 6 eV. The 5σ orbital, being in close proximity to the Fermi energy level, exhibits a higher tendency for electron donation, whereas the 2π* orbital, positioned above the Fermi level, is more inclined toward accepting electrons. As shown in lines 2 to 3 in Figure 3b, the electrons were obviously transferred from the 5σ orbital of CO to the 3dz2 orbitals of Co after CO adsorption. Correspondingly, the unoccupied d orbitals of the Co atom accepted the electrons from *CO, forming the Co–C bonding state to strengthen the CO capture, as evidenced by the evident hybridization between Co_3d and C_2p orbitals around the Fermi level.59 The integral value of the COHP (ICOHP) between the Co_3d orbital and the C_2p orbital is −1.89 eV, confirming the formation of a chemical bond. Furthermore, both 3dxz and 3dyz orbitals experience splitting, leading to the occupation states spanning a broader energy range above and below the Fermi level, accompanied by the disappearance of the asymmetrical peaks. It illustrates that electrons are returned to the hollow antibonding 2π* orbital of the gas by metal dxz and dyz orbitals, following the mechanism of “donation–backdonation”. As a result, 2π* orbitals of adsorbed *CO on the catalyst reveal a significant downshift in comparison with isolated CO molecular. In summary, there exists a “donation–backdonation“ electron exchange mechanism between the Co atom at the adsorption site and the vertically adsorbed gas molecule. Specifically, the gas molecule donates electrons from its highest occupied σ orbital to the metal dz2 orbital, which satisfies the orbital symmetry and has a similar energy level. In return, the metal dxz and dyz orbitals backdonate a portion of electrons to the lowest unoccupied π orbital of the gas molecule.

In addition, we also quantitatively analyze the electron number (Qd) and disparity in the number (ΔQd) of 3d orbitals of Co before and after adsorption by integrating PDOS into the Fermi level, as shown in Tables S5 and S6. It can be seen that the 3dz2 orbital undergoes electron loss, while the 3dxz and 3dyz orbitals experience electron gain, as seen in Figure 3c. Furthermore, the accepted electrons are found in the spin-down 3dxz (β-dxz) and 3dyz (β-dyz) orbitals, whereas the lost electrons occupy the spin-up and spin-down 3dz2 orbitals (α-dz2 and β-dz2). Hence, the electron-transfer behavior is not limited to a simple 5σ → 3dz2 and 3dxz, 3dyz → 2π* transition. Instead, the electrons obtained in 3dz2 from the 5σ orbital are refilled into the 3dxz and 3dyz orbitals (3dz2 → 3dxz, 3dyz) where the electrons were previously depleted. Moreover, the electrons in the 3dx2–y2 and 3dxy orbitals remain the same, demonstrating their presence in the adsorption system as nonbonding orbitals.

Furthermore, the amount of Bader charge transfer between GCPs and Co3(HXTP)2 (X = H, I, T) was analyzed based on the simulation of charge density differences (CDD). The yellow region represents the charge accumulation, and the cyan color is the region of charge depletion in Figure 4a–c. As shown in Figure 4a–c, the GCP molecules gained simultaneously in the hollow region of the Co3(HXTP)2 surface, which indicated that the charges of GCPs are transformed to the nanosheet. The Bader charge analysis shows 0.3–0.403 and 0.416–0.538 e charge transfer for O2 and NO2, which is a very high amount than other GCP molecules.

Figure 4.

(a–c) Charge density differences of CO, NO, NO2, and O2 adsorbed on Co3(HXTP)2 (X = H, I, T). Iso-surfaces is set to 0.01 e/Bohr3. (d) Percentage of changes in magnetic moments for different gases on Co3(HXTP)2 (X = H, I, T). (e) Egap of both spin-up (α) and spin-down (β) orbitals in all O2 and CO adsorption systems. (f) Change rate of band gap changes. (g) Schematic representation of the spin-polarized HOMO and LUMO orbit for Co3(HTTP)2 and Co3(HTTP)2@CO.

The magnetic moments (M) of both the gas and substrate warrant our attention. The density profiles of spin-polarized electron states can be observed in Figure S7. In comparison to the pristine Co3(HXTP)2 substrate, CO adsorption leads to a complete disappearance of spin-polarized electrons at the adsorption site, whereas O2 adsorption preserves these spin-polarized electrons. Specifically, the percentage change in the magnetic moment (ΔM%) caused by the adsorption of each gas on substrates Co3(HTTP)2, Co3(HITP)2, and Co3(HHTP)2, as seen in Figure 4d, is calculated by

| 3 |

where ΔMslabi is the magnetic moment change caused by the adsorption of gas i (CO, NO, NO2, and O2) on base slab Co3(HXTP)2 (X = H, I, and T). The CO adsorption system shows the largest ΔM%, whereas the ΔM% for the O2 adsorption system remains comparatively low, showing two distinct differences in the changes of magnetic moments (ΔM, as provided in Table S7). Meanwhile, Mgas+surface (after gas adsorption) undergoes a certain decrease compared to that of Msurface (pristine surface), except for Co3(HITP)2@O2. As shown in Figure 4e, we use the maximum energy gap between the 3d suborbital band centers (Egap) to roughly evaluate the trend in magnetic moment changes; a higher Egap corresponds to a more pronounced ΔM. Obviously, the Egap for CO adsorption (0.582–0.757 eV) is consistently higher than that for O2 adsorption (0.110–0.397 eV) across all substrates, leading to a significantly greater ΔM in the CO system compared to the O2 system.

The conductivity of the Co3(HXTP)2@GCPs (X = H, I, T) can be estimated based on the band gap (Eg) as shown in the following equation:45,60,61

| 4 |

Additionally, the change rate of the band gap (ΔEg %) is also calculated as follows:

| 5 |

where ΔEg = Ega – Egs is the band gap difference of the adsorption systems (Ega) and the pristine Co3(HXTP)2 (X = H, I, T) slab (Egs), the T denotes temperature, and the kB is Boltzmann’s constant (8.62 × 10–5 eV K–1). As shown in Table S4, the band gaps all decreased with different degrees with the values of ΔEg in the range of −0.006 to −0.397 eV. The conductivity of the substrate dramatically improves along with the reduction of band gap in all adsorption systems, which is advantageous for detecting resistance changes caused by gas adsorption. Specifically, ΔEg % for Co3(HXTP)2 (X = H, I, T) are 35.29–82.35%, 44.81–96.7%, and 29.57–99.50% in Co3(HXTP)2@gas, in Figure 4f, respectively. Furthermore, the adsorption of CO could maximum decrease the values of band gap with the ΔEg % changes of 82.35–98.75%. This observation implies that CO adsorption has the most pronounced influence on the conductivity of the Co3(HXTP)2 material and that CO is the most promising gas for achieving electrochemical gas-sensitive detection. Furthermore, the HOMO and LUMO distributions can reflect the improvement of conductivity. Taking Co3(HTTP)2@Co as an example, the adsorption of CO introduces a redistribution of electron clouds, causing changes in the energy values of HOMO and LUMO, as depicted in Figure 4g. It is evident that there is a significant quantity of LUMO dispersed around the CO, suggesting that these electrons are free to transfer throughout the adsorption process. Moreover, the HOMO and LUMO band gaps (EL–H) significantly reduce upon CO adsorption, thereby enhancing the conductance of the adsorption system and enabling gas detection. The alterations in both the band gaps, HOMO and LUMO orbitals, demonstrate an enhancement in conductivity subsequent to gas adsorption, so Co3(HXTP)2 can be used as a resistive gas sensor to detect CO, NO, NO2, and O2.

Sensing Properties and Recovery Time

Sensing properties are recognized as indicators of the electrochemical gas sensors by considering the change of resistance. The variation of the work function (Φ) can directly reflect the response of the substrate to the gas by changing the resistance of the system. Generally, the Φ refers to the difference between the vacuum and Fermi levels, as shown in Figure 5a, which is calculated by50,62−64

| 6 |

where the Evac is the vacuum level and the EFermi is Fermi level. The calculated Φ (in Table S2) of Co3(HHTP)2, Co3(HITP)2, and Co3(HTTP)2 are 5.302, 4.152, and 5.364 eV, respectively. After the adsorption of GCPs, the Φ value undergoes considerable changes to the range of 4.063–5.623 eV. The difference of work function (ΔΦ) between the pristine Co3(HXTP)2 and the Co3(HXTP)2@GCPs systems increased with different degrees. For example, the ΔΦ of Co3(HHTP)2@NO2/O2, Co3(HITP)2@NO2/O2, and Co3(HTTP)2@NO2 are 0.321, 0.129, 0.416, 0.188, and 0.182 eV, respectively, while that of Co3(HTTP)2@CO is −0.110 eV. Taking Co3(HTTP)2@CO as an example again, the decrease of the work function implies that electrons can more easily escape from Co3(HTTP)2, thereby increasing the electron density on the material surface. This indicates that the adsorption process of CO is accompanied by an increase in electrical conductivity, enabling excellent detection of CO by an electrical measurement. So, these pronounced variations in work function demonstrate that the substrate exhibits excellent gas responsiveness and can be preferentially detected. In short, the superior sensing properties of Co3(HXTP)2 is primarily attributed to the strong chemical interactions. Gas molecules adsorbed within the electron localization cavities of Co3(HXTP)2 can change the electron transport pathways in the material, resulting in significant changes in its electrical conductivity, which facilitate their detection. In addition, we compared relevant previous studies, as shown in Table 2. It can be seen that our research with a high sensing performance for the adsorption of NO2, O2, and CO demonstrates advantages over some earlier studies. A larger change in the work function indicates a stronger gas-sensing capability, which also suggests that the Co3(HXTP)2 material is more suitable for use as a corresponding gas-sensing material. Thus, they are selected for further desorption characteristics studies.

Figure 5.

(a) Schematic of the work function for Co3(HTTP)2@CO and the changes in the work function (ΔΦ). The orange line represents ΔΦ of ± 0.1 eV. (b) τ of the adsorption systems.

Table 2. Comparison of the Changes of Work Function (ΔΦ) of Co3(HTTP)2@CO/NO2/O2 in This Study and Previous Studies.

In order to be reused, the adsorbed gas should be able to desorption smoothly so that the gas-sensitive material can return to its preadsorption state; hence, the reasonable recovery time of gas-sensitive materials has been a focus of research. The recovery time (τ) is calculated by69−71

| 7 |

where Eads is the adsorption energy of gases, and the A–1 represents the apparent frequency factor (1012 s–1). The τ can be reduced by heating, and strong Eads can lead to longer τ, according to the formula. As seen in Figure 5b, the τ is then investigated at 298 and 498 K. Due to the moderate Eads, Co3(HHTP)2@O2 and Co3(HITP)2@O2 exhibit rapid recovery at 298 K, with τ of only 1.226 and 19.441 s, respectively. Furthermore, Co3(HTTP)2 at 498 K has a short τ of 694.226 s, indicating that CO can desorb from Co3(HTTP)2 at high temperatures. However, caused by the large Eads, the τ values for the other systems are significantly prolonged, suggesting their unsuitability as gas-sensitive materials. Therefore, after the adsorption of gases, some Co3(HXTP)2 can rapidly return to its original surface state within a short period, allowing for the subsequent adsorption, sensing, and desorption of gases. This indicates that it possesses long-term stable gas-sensing performance, significantly enhancing the economic viability of using Co3(HXTP)2 as a GCPs sensing material. In conclusion, Co3(HHTP)2@O2, Co3(HITP)2@O2, and Co3(HTTP)2@CO exhibit favorable τ values, demonstrating their suitability as highly efficient gas-sensitive materials.

Descriptors of the Gas-Sensitive Material

For gas-sensitive materials, it is essential but challenging to identify key parameters and suitable descriptors. A perfect descriptor should exhibit strong correlation with both the adsorption energies of GCPs (Eads) and change in the work function (ΔΦ). In this regard, we proposed several key parameters and made a heat map of the Pearson correlations related to Eads and ΔΦ. The features utilized for constructing the Pearson correlation coefficient (P) heat map encompass the electron count in spin-up and spin-down d/p-orbitals (α-QTM-d, β-QTM-d, α-Qgas-p, β-Qgas-p) of substate and the GCPs, and electron changes (Δβ-Qdxz+dyz, Δβ-Qdz2) for dxz, dyz, and dz2 of the Co atom. The LUMO–HOMO band gap (EL–H) and average Pauling electronegativity (χgas-average) are for the gas molecules. The lattice constant (aslab), work function (Φslab), and d-band center (α-φd, β-φd) for the substrate. In Figure 6a, the chordal thickness connecting each feature represents the absolute value of their Pearson correlation coefficient (P, detailed parameters can be found in Figure S8). It is noteworthy that some features show strong correlation with either ΔΦ or Eads, but no feature exhibits an ideal correlation coefficient (|P| ≥ 0.7) with both targets simultaneously. Thus, we proposed a descriptor φ with the following formula:

| 8 |

Figure 6.

(a) Chordal graph of correlations between individual features plotted using Pearson correlations coefficient data, while chordal with lower correlation coefficients are displayed in gray. (b) Heat map of the Pearson correlation coefficient between the φ, the features used by the constructed descriptor and ΔΦ, Eads.

The χgas-average and the β-Qgas-p were selected as divisors due to their prevalent use in previous72−75 descriptors involving the product of electronegativity and electrons count. In this study, incorporating gas properties enables a more comprehensive characterization of diverse adsorption systems compared to focusing solely on the properties of the Co metal. Additionally, these gas-related factors demonstrate a stronger correlation with the target variable, as indicated by the heat map in Figure S8. Meanwhile, the product of EL–H and lCo-gas was chosen as the dividend, where EL–H exhibits the best dual-correlation performance, and lCo-gas accounts for the adsorption structure correlation effects. The created descriptor φ exhibits an absolute value for the Pearson coefficient of over 0.7 for both ΔΦ or Eads, as illustrated in Figure 6b. The φ exhibit a strong negative correlation coefficient of −0.73 with the work function, and conversely, a significant positive correlation coefficient of 0.72 with the Eads. This confirms that it can assess both targets simultaneously. Consequently, we can conclude that descriptor φ enables a rapid assessment of the adsorption and response properties of gas-sensitive materials.

Conclusions

This study focuses on metal–organic framework structures (Co3(HXTP)2) to explore their feasibility as gas-sensitive materials for combustion process gases (GCPs). We calculated the adsorption energies (Eads), variation in work function (ΔΦ), and the recovery time (τ) for the adsorption systems. Among these systems, Co3(HHTP)2@O2, Co3(HITP)2@O2, and Co3(HTTP)2@CO exhibit excellent response characteristics with the ΔΦ of 0.129 0.188, and −0.110 eV, respectively. For Co3(HHTP)2@O2 and Co3(HITP)2@O2, although the adsorption energies are not the best, the moderate Eads (−0.715 and −0.786 eV) imply very short recovery time at 298 K, which are 1.226 and 19.441 s, respectively, suggesting potential in gas-sensitive materials. The Co3(HTTP)2@CO possesses outstanding Eads of −1.467 eV and τ of merely 694.226 s at 498 K, which makes Co3(HTTP)2 a highly promising candidate for CO gas sensing. In the case of Co3(HTTP)2@CO, the strong chemical interaction follows a “donation–backdonation” mechanism, where electrons transfer between Co and CO (5σ → 3dz2 and 3dxz, 3dyz →2π*), alongside electron rearrangement within d orbitals of Co atom (3dz2 → 3dxz, 3dyz). The results of the change in magnetic moment (ΔM), the band gap (Eg), and the HOMO and LUMO band gaps (EL–H) imply the transfer of electrons and an increase in conductivity. The introduced descriptor φ shows a strong linear correlation with Eads and ΔΦ, with the Pearson correlation coefficient of 0.72 and −0.73, respectively, which can be used as a possible predictor for gas sensitivity. We believe that these findings offer valuable insights for further exploration of TM3(HXTP)2 as catalysts or gas-sensitive materials.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China [Grant No. 22168036]; the Central Government Funds for Local Science and Technological Development [No. XZ202201YD0020C]; the Natural Science Foundation Project of Tibet Autonomous Region [XZ202301ZR0026G]; the Tibet University Graduate High-Level Talent Training Program [Grant No. 2022-GSP-S047]. In addition, we gratefully acknowledge HZWTECH for providing computation facilities.

Supporting Information Available

The Supporting Information is available free of charge at https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acsomega.4c10559.

Visualizations of charge localization, projected density of states (PDOS), and band structures for Co3(HITP)2 and Co3(HTTP)2; PDOS for Co3(HHTP)2; all considered adsorption configurations along with their corresponding adsorption energy data; total density of states (TDOS) images for the optimized adsorption systems; spin-electron distribution for gas adsorption of NO2, NO, CO, and O2; Pearson correlation coefficient heatmaps containing all relevant data; physical and electronic parameters for the GCP gases and Co3(HXTP)2 substrate, including bond lengths, bond angles, magnetic moments, HOMO–LUMO gaps of gas molecules and lattice constants, average metal–ligand bond lengths, band gaps, and magnetic moments of the Co3(HHTP)2 substrate; the average bond lengths of Co-X4 center after gas adsorption and their corresponding changes; adsorption heights of gas molecules; bond lengths of chemical bonds formed between gas molecules and metals; band gaps of gas molecules after adsorption and their changes; magnetic moments after gas adsorption and their variations; work functions after gas adsorption and their changes; number of electrons transferred between gas molecules and the substrate; and electron counts and changes in dxz, dyz, and dz2 orbitals for adsorption systems. (PDF)

Author Contributions

∥ T.F., W.X., and D.L. contributed equally to this work. T.F.: conceptualization, data curation, formal analysis, investigation, methodology, software, visualization, and writing—original draft. W.X.: investigation, methodology, and writing—review and editing. D.L.: investigation, methodology, and writing—review and editing. J.X.: methodology, supervision, validation, and writing—review and editing. Q.W.: resources, supervision, validation, and writing—review and editing.

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

Supplementary Material

References

- Wang Z.; Bu M.; Hu N.; Zhao L. An overview on room-temperature chemiresistor gas sensors based on 2D materials: Research status and challenge. Composites, Part B 2023, 248, 110378 10.1016/j.compositesb.2022.110378. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Q.; Huang B.; Li X. Graphene-Based Heterostructure Composite Sensing Materials for Detection of Nitrogen-Containing Harmful Gases. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2021, 31 (41), 2104058 10.1002/adfm.202104058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao C.; Zhang Y.; Yang H.; Liu Y.; Liu Y.; Du J.; Ye H.; Zhang G. A DFT study of In doped Tl2O: a superior NO2 gas sensor with selective adsorption and distinct optical response. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2019, 494, 162–169. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2019.07.067. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liangruksa M.; Sukpoonprom P.; Junkaew A.; Photaram W.; Siriwong C. Gas sensing properties of palladium-modified zinc oxide nanofilms: A DFT study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2021, 544, 148868 10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.148868. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yang C.; Yang Y.; Zhang C.; Yu H.; Wang T.; Shi K.; Zhang Z.; Wang D.; Dong X. High selectivity of Ag-doped Fe2O3 hollow nanofibers in H2S detection at room operating temperature. Sens. Actuators, B 2021, 341, 129919 10.1016/j.snb.2021.129919. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Y.; Chen X.; Weng K.; Arramel; Jiang J.; Ong W. J.; Zhang P.; Zhao X.; Li N. Highly Sensitive and Selective Gas Sensor Using Heteroatom Doping Graphdiyne: A DFT Study. Adv. Electron. Mater. 2021, 7 (7), 2001244 10.1002/aelm.202001244. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liang X.-Y.; Ding N.; Ng S.-P.; Wu C.-M. L. Adsorption of gas molecules on Ga-doped graphene and effect of applied electric field: A DFT study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 411, 11–17. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.03.178. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Deshpande S.; Deshpande M.; Ahuja R.; Hussain T. Tuning the electronic, magnetic, and sensing properties of a single atom embedded microporous C3N6 monolayer towards XO2 (X = C, N, S) gases. New J. Chem. 2022, 46 (28), 13752–13765. 10.1039/D2NJ01956F. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xiao Z.; Wu W.; Wu X.; Zhang Y. Adsorption of NO2 on monolayer MoS2 doped with Fe, Co, and Ni, Cu: A computational investigation. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2020, 755, 137768 10.1016/j.cplett.2020.137768. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fan Y.; Zhang J.; Qiu Y.; Zhu J.; Zhang Y.; Hu G. A DFT study of transition metal (Fe, Co, Ni, Cu, Ag, Au, Rh, Pd, Pt and Ir)-embedded monolayer MoS2 for gas adsorption. Comput. Mater. Sci. 2017, 138, 255–266. 10.1016/j.commatsci.2017.06.029. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu H.; Wang F.; Hu K.; Li T.; Yan Y.; Li J. The Adsorption and Sensing Performances of Ir-modified MoS2 Monolayer toward SF6 Decomposition Products: A DFT Study. Nanomaterials 2021, 11 (1), 100. 10.3390/nano11010100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang M.; Zeng Q.; Cao J.; Chen D.; Zhang Y.; Liu J.; Jia P. Highly Sensitive Gas Sensor for Detection of Air Decomposition Pollutant (CO, NOx): Popular Metal Oxide (ZnO, TiO2)-Doped MoS2 Surface. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16 (3), 3674–3684. 10.1021/acsami.3c15103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jo Y. M.; Jo Y. K.; Lee J. H.; Jang H. W.; Hwang I. S.; Yoo D. J. MOF-Based Chemiresistive Gas Sensors: Toward New Functionalities. Adv. Mater. 2023, 35 (43), 22006842 10.1002/adma.202206842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lv Y.; Xu P.; Yu H.; Xu J.; Li X. Ni-MOF-74 as sensing material for resonant-gravimetric detection of ppb-level CO. Sens. Actuators, B 2018, 262, 562–569. 10.1016/j.snb.2018.02.058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nguyen D.-K.; Lee J.-H.; Nguyen T.-B.; Le Hoang Doan T.; Phan B. T.; Mirzaei A.; Kim H. W.; Kim S. S. Realization of selective CO detection by Ni-incorporated metal-organic frameworks. Sens. Actuators, B 2020, 315, 128110 10.1016/j.snb.2020.128110. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pentyala V.; Davydovskaya P.; Ade M.; Pohle R.; Urban G. Carbon dioxide gas detection by open metal site metal organic frameworks and surface functionalized metal organic frameworks. Sens. Actuators, B 2016, 225, 363–368. 10.1016/j.snb.2015.11.071. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.; Xiong S.; Gong Y.; Gong Y.; Wu W.; Mao Z.; Liu Q.; Hu S.; Long X. MOF-SMO hybrids as a H2S sensor with superior sensitivity and selectivity. Sens. Actuators, B 2019, 292, 32–39. 10.1016/j.snb.2019.04.076. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sun L.; Campbell M. G.; Dincă M. Electrically Conductive Porous Metal–Organic Frameworks. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2016, 55 (11), 3566–3579. 10.1002/anie.201506219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ko M.; Mendecki L.; Mirica K. A. Conductive two-dimensional metal–organic frameworks as multifunctional materials. Chem. Commun. 2018, 54 (57), 7873–7891. 10.1039/C8CC02871K. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie L. S.; Skorupskii G.; Dincă M. Electrically Conductive Metal–Organic Frameworks. Chem. Rev. 2020, 120 (16), 8536–8580. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talin A. A.; Centrone A.; Ford A. C.; Foster M. E.; Stavila V.; Haney P.; Kinney R. A.; Szalai V.; Gabaly F. E.; Yoon H. P.; et al. Reticular synthesis and the design of new materials. Science 2014, 423 (6941), 705–714. 10.1126/science.1246738. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Downes C. A.; Clough A. J.; Chen K.; Yoo J. W.; Marinescu S. C. Evaluation of the H2 Evolving Activity of Benzenehexathiolate Coordination Frameworks and the Effect of Film Thickness on H2 Production. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10 (2), 1719–1727. 10.1021/acsami.7b15969. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mendecki L.; Mirica K. A. Conductive Metal–Organic Frameworks as Ion-to-Electron Transducers in Potentiometric Sensors. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2018, 10 (22), 19248–19257. 10.1021/acsami.8b03956. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J.; Huang Y.; Zhou Y.; Dong H.; Wang H.; Shan H.; Li Y.; Xu M.; Wang X. Controllable Construction of Two-Dimensional Conductive M3(HHTP)2 Nanorods for Electrochemical Sensing of Malachite Green in Fish. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2023, 6 (24), 22916–22926. 10.1021/acsanm.3c04264. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mähringer A.; Jakowetz A. C.; Rotter J. M.; Bohn B. J.; Stolarczyk J. K.; Feldmann J.; Bein T.; Medina D. D. Oriented Thin Films of Electroactive Triphenylene Catecholate-Based Two-Dimensional Metal–Organic Frameworks. ACS Nano 2019, 13 (6), 6711–6719. 10.1021/acsnano.9b01137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. G.; Sheberla D.; Liu S. F.; Swager T. M.; Dincă M. Cu3(hexaiminotriphenylene)2: An Electrically Conductive 2D Metal–Organic Framework for Chemiresistive Sensing. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2015, 54 (14), 4349–4352. 10.1002/anie.201411854. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lian Y.; Yang W.; Zhang C.; Sun H.; Deng Z.; Xu W.; Song L.; Ouyang Z.; Wang Z.; Guo J.; Peng Y. Unpaired 3d Electrons on Atomically Dispersed Cobalt Centres in Coordination Polymers Regulate both Oxygen Reduction Reaction (ORR) Activity and Selectivity for Use in Zinc–Air Batteries. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2020, 59 (1), 286–294. 10.1002/anie.201910879. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yao M. S.; Lv X. J.; Fu Z. H.; Li W. H.; Deng W. H.; Wu G. D.; Xu G. Layer-by-Layer Assembled Conductive Metal–Organic Framework Nanofilms for Room-Temperature Chemiresistive Sensing. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2017, 56 (52), 16510–16514. 10.1002/anie.201709558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hmadeh M.; Lu Z.; Liu Z.; Gándara F.; Furukawa H.; Wan S.; Augustyn V.; Chang R.; Liao L.; Zhou F.; et al. New Porous Crystals of Extended Metal-Catecholates. Chem. Mater. 2012, 24 (18), 3511–3513. 10.1021/cm301194a. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Miner E. M.; Wang L.; Dincă M. Modular O2 electroreduction activity in triphenylene-based metal–organic frameworks. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9 (29), 6286–6291. 10.1039/C8SC02049C. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clough A. J.; Skelton J. M.; Downes C. A.; de la Rosa A. A.; Yoo J. W.; Walsh A.; Melot B. C.; Marinescu S. C. Metallic Conductivity in a Two-Dimensional Cobalt Dithiolene Metal–Organic Framework. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2017, 139 (31), 10863–10867. 10.1021/jacs.7b05742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheberla D.; Sun L.; Blood-Forsythe M. A.; Er S.; Wade C. R.; Brozek C. K.; Aspuru-Guzik A.; Dincă M. High Electrical Conductivity in Ni3(2,3,6,7,10,11-hexaiminotriphenylene)2, a Semiconducting Metal–Organic Graphene Analogue. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2014, 136 (25), 8859–8862. 10.1021/ja502765n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu X.; Xu W.; Wang Z.; Li H.; Wang M.; Zhang D.; Lai J.; Wang L. Rapid microwave synthesis of Ru-supported partially carbonized conductive metal–organic framework for efficient hydrogen evolution. Chem. Eng. J. 2022, 431, 133247 10.1016/j.cej.2021.133247. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J.; Li F.; Liu Z.; Dai Z.; Gao S.; Zhao M. Two-Dimensional Conductive Metal–Organic Frameworks as Highly Efficient Electrocatalysts for Lithium–Sulfur Batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2021, 13 (51), 61205–61214. 10.1021/acsami.1c19381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tian Y.; Zhao T.; Zhao C.; Likai Y. Two–dimensional metal organic nanosheet as promising electrocatalysts for carbon dioxide reduction: A computational study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 597, 153724 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.153724. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Momeni M. R.; Zhang Z.; Dell’Angelo D.; Shakib F. A. Tuning electronic properties of conductive 2D layered metal–organic frameworks via host–guest interactions: Dioxygen as an electroactive chemical stimuli. APL Mater. 2021, 9 (5), 051109 10.1063/5.0049317. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Campbell M. G.; Liu S. F.; Swager T. M.; Dincă M. Chemiresistive Sensor Arrays from Conductive 2D Metal–Organic Frameworks. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2015, 137 (43), 13780–13783. 10.1021/jacs.5b09600. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhauriyal P.; Heine T. Catalysing the performance of Li–sulfur batteries with two-dimensional conductive metal organic frameworks. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10 (23), 12400–12408. 10.1039/D2TA00521B. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hafner J. Ab-initiosimulations of materials using VASP: Density-functional theory and beyond. J. Comput. Chem. 2008, 29 (13), 2044–2078. 10.1002/jcc.21057. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blöchl P. E. Projector augmented-wave method. Phys. Rev. B 1994, 50 (24), 17953–17979. 10.1103/PhysRevB.50.17953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perdew J. P.; Yue W. Accurate and simple density functional for the electronic exchange energy: Generalized gradient approximation. Phys. Rev. B 1986, 33 (12), 8800–8802. 10.1103/PhysRevB.33.8800. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grimme S.; Antony J.; Ehrlich S.; Krieg H. A consistent and accurate ab initio parametrization of density functional dispersion correction (DFT-D) for the 94 elements H-Pu. J. Chem. Phys. 2010, 132, 154104 10.1063/1.3382344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng Z.; Zhang X.; Zhang H.; Liu H.; Yu X.; Dai X.; Liu G.; Chen G. BeN4 monolayer as an excellent Dirac anode material for potassium-ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd. 2023, 936, 168351 10.1016/j.jallcom.2022.168351. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Toton D.; Lorenz C. D.; Rompotis N.; Martsinovich N.; Kantorovich L. Temperature control in molecular dynamic simulations of non-equilibrium processes. J. Phys.: Condens. Matter 2010, 22 (7), 074205 10.1088/0953-8984/22/7/074205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas S.; Mayr F.; Madam A. K.; Gagliardi A. Machine learning and DFT investigation of CO, CO2and CH4 adsorption on pristine and defective two-dimensional magnesene. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2023, 25 (18), 13170–13182. 10.1039/D3CP00613A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao P.; Tang M.; Zhang D. Adsorption of dissolved gas molecules in the transformer oil on metal (Ag, Rh, Sb)-doped PdSe2 momlayer: A first-principles study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 600, 154054 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.154054. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Du R.; Wu W. Adsorption of gas molecule on Rh, Ru doped monolayer MoS2 for gas sensing applications: A DFT study. Chem. Phys. Lett. 2022, 789, 139300 10.1016/j.cplett.2021.139300. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Aghaei S. M.; Monshi M. M.; Torres I.; Zeidi S. M. J.; Calizo I. DFT study of adsorption behavior of NO, CO, NO2, and NH3 molecules on graphene-like BC3: A search for highly sensitive molecular sensor. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2018, 427, 326–333. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2017.08.048. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Isa M.; Ashfaq I.; Majid A.; Shakil M.; Iqbal T. A DFT study of silver decorated bismuthene for gas sensing properties and effect of humidity. Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 2022, 145, 106635 10.1016/j.mssp.2022.106635. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V.; Rajput K.; Roy D. R. Sensing applications of GeBi nanosheet for environmentally toxic/non-toxic gases: Insights from density functional theory calculations. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 606, 154741 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.154741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yu Y.; Dai C. DFT study of gas adsorption and sensing based on noble metal (Ag, Au and Pt) functionalized boron selenide nanosheets. Physica E 2021, 125, 114409 10.1016/j.physe.2020.114409. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang D.; She A.; Yang H.; Liu X.; Li H.; Feng M. Fe2GeS4 (010) surface oxidation mechanism and potential application of the oxidized surface in gas sensing: A first-principles study. J. Alloys Compd. 2021, 888, 161532 10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.161532. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar V.; Jung J. Enhancement of gas sensing by doping of transition metal in two-dimensional As2C3 nanosheet: A density functional theory investigation. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 599, 153941 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.153941. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chepkasov I. V.; Sukhanova E. V.; Kvashnin A. G.; Zakaryan H. A.; Aghamalyan M. A.; Mamasakhlisov Y. S.; Manakhov A. M.; Popov Z. I.; Kvashnin D. G. Computational Design of Gas Sensors Based on V3S4 Monolayer. Nanomaterials 2022, 12 (5), 774. 10.3390/nano12050774. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun X.; Song Z.; Liu Q.; Xiao B.; Li Y.; Cheng J.; Liu Z.; Yang X.; Yu X.; Li Q. First-principles study on the C-excess C3B for its potential application in sensing NO2 and NO. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2020, 512, 145611 10.1016/j.apsusc.2020.145611. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dai J.; Yuan J. Adsorption of molecular oxygen on doped graphene: Atomic, electronic, and magnetic properties. Phys. Rev. B 2010, 81 (16), 165414 10.1103/PhysRevB.81.165414. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Panigrahi P.; Hussain T.; Karton A.; Ahuja R. Elemental Substitution of Two-Dimensional Transition Metal Dichalcogenides (MoSe2and MoTe2): Implications for Enhanced Gas Sensing. ACS Sens. 2019, 4 (10), 2646–2653. 10.1021/acssensors.9b01044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakhuja N.; Jha R. K.; Chaurasiya R.; Dixit A.; Bhat N. 1T-Phase Titanium Disulfide Nanosheets for Sensing H2S and O2. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3 (4), 3382–3394. 10.1021/acsanm.0c00127. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y.; Wang Y.; Ma N.; Li Y.; Liang B.; Luo S.; Fan J. Establishing an orbital-level understanding of active origins of heteroatom-coordinated single-atom catalysts: The case of N2 reduction. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 650, 961–971. 10.1016/j.jcis.2023.07.047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khan M. I.; Hassan M.; Majid A.; Shakil M.; Rafique M. DFT perspective of gas sensing properties of Fe-decorated monolayer antimonene. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 616, 156520 10.1016/j.apsusc.2023.156520. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chen D.; Zhang X.; Tang J.; Cui Z.; Cui H. Pristine and Cu decorated hexagonal InN monolayer, a promising candidate to detect and scavenge SF6 decompositions based on first-principle study. J. Hazard. Mater. 2019, 363, 346–357. 10.1016/j.jhazmat.2018.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raval D.; Gupta S. K.; Gajjar P. N. Detection of H2S, HF and H2 pollutant gases on the surface of penta-PdAs2 monolayer using DFT approach. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13 (1), 699 10.1038/s41598-023-27563-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hu J.; Zhai S.; Zhang Q.; Cui H.; Jiang X. Two-dimensional HfTe2 monolayer treated by dispersed single Pt atom for hazardous gas Detection: A First-principles study. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2022, 605, 154572 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.154572. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Guo G.; Mao L.; Liu K.; Tan X. Pd-Adsorbed SiN3 Monolayer as a Promising Gas Scavenger for SF6 Partial Discharge Decomposition Components: Insights from the First-Principles Study. Langmuir 2024, 40 (14), 7669–7679. 10.1021/acs.langmuir.4c00370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma Y.; Xiong H.; Gan L.; Deng G. Theoretical investigation of FeMnPc, Fe2Pc, Mn2Pc monolayers as a potential gas sensors for nitrogenous toxic gases. Surf. Interfaces 2024, 45, 103910 10.1016/j.surfin.2024.103910. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pan W.; Qi N.; Zhao B.; Chang S.; Ye S.; Chen Z. Gas sensing properties of buckled bismuthene predicted by first-principles calculations. Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2019, 21 (21), 11455–11463. 10.1039/C9CP01174A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao J.; Cui X.; Huang Q.; Zeng H. Adsorption behavior of small molecule on monolayered SiAs and sensing application for NO2 toxic gas. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2023, 613, 156010 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.156010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao Z.; Yong Y.; Hu S.; Li C.; Kuang Y. Adsorption of gas molecules on a C3N monolayer and the implications for NO2 sensors. AIP Adv. 2019, 9 (12), 125308 10.1063/1.5128803. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang H.; Xiang Y.; Zhan H.; Zhou Y.; Kang J. DFT investigation of transition metal-doped graphene for the adsorption of HCl gas. Diam. Relat. Mater. 2023, 136, 109995 10.1016/j.diamond.2023.109995. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y.; Meng Y.; Li X.; Sun J.; Li X. FeN4-embedded warped nanographene as a potential candidate for scavenging and detecting sulfur-based gases: A DFT study. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2023, 11 (3), 109705 10.1016/j.jece.2023.109705. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ma D.; Zhang J.; Li X.; He C.; Lu Z.; Lu Z.; Yang Z.; Wang Y. C3N monolayers as promising candidates for NO2 sensors. Sens. Actuators, B 2018, 266, 664–673. 10.1016/j.snb.2018.03.159. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gao S.; Cheng Y.; Chen L.; Huang S. Rapid Discovery of Gas Response in Materials Via Density Functional Theory and Machine Learning. Energy Environ. Mater. 2024, 0, e12816 10.1002/eem2.12816. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu H.; Cheng D.; Cao D.; Zeng X. Revisiting the universal principle for the rational design of single-atom electrocatalysts. Nat. Catal. 2024, 7, 207–218. 10.1038/s41929-023-01106-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Qi L.; Gao W.; Jiang Q. Effective Descriptor for Designing High-Performance Catalysts for the Hydrogen Evolution Reaction. J. Phys. Chem. C 2020, 124 (42), 23134–23142. 10.1021/acs.jpcc.0c05898. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Xu R.; Bo T.; Cao S.; Mu N.; Liu Y.; Chen M.; Zhou W. High-throughput screening of transition metal doping and defect engineering on single layer SnS2 for the water splitting hydrogen evolution reaction. J. Mater. Chem. A 2022, 10 (40), 21315–21326. 10.1039/D2TA04254A. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.