Abstract

The σS (RpoS) subunit of RNA polymerase is the master regulator of the general stress response in Escherichia coli and related bacteria. While rapidly growing cells contain very little σS, exposure to many different stress conditions results in rapid and strong σS induction. Consequently, transcription of numerous σS-dependent genes is activated, many of which encode gene products with stress-protective functions. Multiple signal integration in the control of the cellular σS level is achieved by rpoS transcriptional and translational control as well as by regulated σS proteolysis, with various stress conditions differentially affecting these levels of σS control. Thus, a reduced growth rate results in increased rpoS transcription whereas high osmolarity, low temperature, acidic pH, and some late-log-phase signals stimulate the translation of already present rpoS mRNA. In addition, carbon starvation, high osmolarity, acidic pH, and high temperature result in stabilization of σS, which, under nonstress conditions, is degraded with a half-life of one to several minutes. Important cis-regulatory determinants as well as trans-acting regulatory factors involved at all levels of σS regulation have been identified. rpoS translation is controlled by several proteins (Hfq and HU) and small regulatory RNAs that probably affect the secondary structure of rpoS mRNA. For σS proteolysis, the response regulator RssB is essential. RssB is a specific direct σS recognition factor, whose affinity for σS is modulated by phosphorylation of its receiver domain. RssB delivers σS to the ClpXP protease, where σS is unfolded and completely degraded. This review summarizes our current knowledge about the molecular functions and interactions of these components and tries to establish a framework for further research on the mode of multiple signal input into this complex regulatory system.

INTRODUCTION

σS, or RpoS, is a sigma subunit of RNA polymerase in Escherichia coli that is induced and can partially replace the vegetative sigma factor σ70 (RpoD) under many stress conditions. As a consequence, transcription of numerous σS-dependent genes is activated (for reviews, see references 75, 77, 79, 124, and 125). Consistent with the multiple functions of the σS regulon, the rpoS gene was discovered independently and named accordingly by several groups (recently summarized in references 79 and 105). It was identified as a gene involved in near-UV resistance (nuv) (216); as a regulator for the katE-encoded catalase HPII (katF) (126, 186), exonuclease III (xthA) [186], and acidic phosphatase (appR) (211); and, finally, as a starvation-inducible gene encoding a central regulator for stationary phase-inducible genes (csi-2) (113). Only then was it recognized that all the previous studies had described alleles of the same gene (113, 212), which codes for a sigma factor (152, 156, 209). Because of its crucial role in stationary phase or under stress conditions, the name σS or RpoS was proposed (113). In addition, the term σ38 is used sometimes (although the molecular mass of σS deviates from 38 kDa in various species and even in some E. coli strains). The rpoS gene has also been identified in other enteric and related bacteria. At present, it seems that σS occurs in the γ branch of the proteobacteria, i.e., in a group of gram-negative bacteria that includes many species with special importance for humans because of their pathogenic or beneficial potential. With minor variations, the general function of σS in these bacteria appears to be similar to that in E. coli (summarized in reference 79).

In more recent studies, it was demonstrated that σS and σS-dependent genes not only are induced in stationary phase but actually respond to many different stress conditions (76, 82, 121, 144, 148). Therefore, σS is now seen as the master regulator of the general stress response, which is triggered by many different stress signals, is often (though not always) accompanied by a reduction or cessation of growth, and provides the cells with the ability to survive the actual stress as well as additional stresses not yet encountered (cross-protection). This is in pronounced contrast to specific stress responses, which are triggered by a single stress signal and result in the induction of proteins that allow cells to cope with this specific stress situation only. While specific stress responses tend to eliminate the stress agent and/or to mediate repair of cellular damage that has already occurred, the general stress response renders cells broadly stress resistant in such a way that damage is avoided rather than needing to be repaired (for a recent review of different bacterial stress responses, see reference 203).

The major function of the general stress response is thus preventive, which is clearly reflected in the σS-dependent multiple stress resistance observed with starved or otherwise stressed cells (82, 113, 136) (for a recent review of the general stress response that also includes physiological aspects, see reference 79). Accordingly, the majority of the more than 70 σS-dependent genes known so far confer resistance against oxidative stress, near-UV irradiation, potentially lethal heat shocks, hyperosmolarity, acidic pH, ethanol, and probably other stresses yet to be identified. Additional σS-controlled gene products generate changes in the cell envelope and overall morphology (stressed E. coli cells tend to become smaller and ovoid). Metabolism is also affected by σS-controlled genes, consistent with σS being important under conditions where cells switch from a metabolism directed toward maximal growth to a maintenance metabolism. σS also controls genes mediating programmed cell death in stationary phase, which may increase the chances for survival for a bacterial population under extreme stress by sacrificing a fraction of the population in order to provide nutrients for the remaining surviving cells (22). Finally, a number of virulence genes in pathogenic enteric bacteria have been found to be under σS control, consistent with the notion that host organisms provide stressful environments for invading pathogens (recently summarized in reference 80). However, even though numerous σS-dependent genes have been identified (see references 77, 79, and 125 for recent compilations), many more such genes will probably be found in the future. Moreover, the functions of the genes known so far are incompletely understood. Even after more than 10 years of intensive research on σS, much remains to be learned about the physiology of the σS-mediated response. The same is true for the regulatory interdependencies within the large regulatory network directed by σS. By contrast, the basic mechanisms of regulation of σS itself are now reasonably well understood and are the subject of this review (for recent minireviews on the same subject, see references 81 and 125). Since by far most of the relevant work has been done with E. coli and Salmonella, the systems referred to in this review are those described for these enteric bacteria if not otherwise mentioned. Whereas the physiological function of σS is comparable in all species where it has been discovered to date, there are significant differences between enteric bacteria and pseudomonads in the regulation of σS that are outlined specifically.

THE PROBLEM OF MULTIPLE STRESS SIGNAL INTEGRATION

Complex and physiologically far-reaching bacterial responses often use a single master regulator at the interface of upstream signal processing and downstream regulatory mechanisms. In the general stress response of E. coli, σS plays the role of this top-level master regulator. Other examples of such central regulators are σB in the general stress response of various gram-positive bacteria (172) and the response regulator Spo0A in sporulation initiation of Bacillus subtilis (202). The master regulators serve as the decisive information processing units, which connect complex signaling networks with downstream regulatory cascades or networks that ultimately control the expression of numerous structural genes associated with a response. These regulatory networks exhibit a hierarchical and modular structure; i.e., they can be subdivided into lower-level smaller modules that are under the control of secondary regulators, which also allow specific signal input at such lower and more confined levels. A master regulator may also commit the cell to a certain complex developmental program, with specific temporal and spatial control being exerted by secondary regulalors.

Depending on the type of master regulator (sigma factor, two-component response regulator, etc.) as well as on whether its cellular level or its activity (or both) is the decisive parameter, signal transduction and integration upstream of the central regulator can be very different. In the general stress response of E. coli, the decisive parameter is the cellular level of σS (however, as described below, there is now some initial evidence that σS may also be subject to some sort of activity control). σS levels increase in response to starvation for carbon, nitrogen, or phosphate sources as well as for amino acids. This leads to entry into stationary phase, i.e., a complete cessation of growth, but σS can also be induced by a partial reduction of the growth rate (64, 89, 92, 113, 114, 157, 210). Additional inducing conditions are hyperosmolarity (148), nonoptimally high (144) or low (199) temperature, acidic pH (18, 121), high cell density (114), and probably other environmental stress situations.

How can so many different stress signals be integrated toward a single parameter, i.e., the intracellular σS concentration? Do they generate a common intracellular signal? Initially it seemed that a reduction or cessation of growth might be such a signal. However, σS is also induced in late exponential phase (provided that a certain cell density is reached) without any change of growth rate (114). In response to the classical heat shock procedure (i.e., a shift from 30 to 42°C), σS is induced even though growth is accelerated (144). On the basis of more recent studies, it has become clear that the concept of a unifying intracellular σS-inducing signal cannot be correct, simply because different environmental signals affect different levels and therefore completely different processes in the regulation of σS.

Regulation of σS occurs at nearly every theoretically possible level (Fig. 1). rpoS transcription is stimulated by controlled downshifts in growth rate in a chemostat (157, 210) as well as by continuous reduction in growth rate which results in an inversely correlated increase in rpoS transcription (5- to 10-fold) (113, 114). By contrast, abrupt cessation of growth, as for example, in response to sudden glucose starvation, only weakly increases rpoS transcription (less than twofold) (113, 114). rpoS translation, i.e., the rate of translation of already existing rpoS mRNA, is stimulated (i) by high osmolarity (hyperosmotic shift rapidly activates translation more than fivefold, but also continuous growth at high osmolarity has clear effects) (148), (ii) during growth at moderately low temperatures (e.g., at 20°C) (199), (iii) on reaching a certain cell density (approximately 1 × 108 to 2 × 108 cells ml−1) during growth in minimal glucose medium (114), and (iv) in response to a pH downshift from pH 7 to pH 5 in rich medium (G. Kampmann and R. Hengge-Aronis, unpublished data).

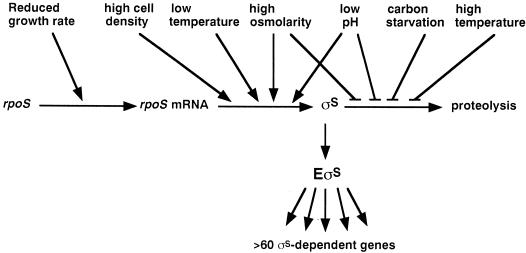

FIG. 1.

Various levels of σS regulation are differentially affected by various stress conditions. An increase of the cellular σS level can be obtained either by stimulating σS synthesis at the levels of rpoS transcription or rpoS mRNA translation or by inhibiting σS proteolysis (which under nonstress conditions is extraordinarily rapid). The most rapid and strongest reaction can be achieved by a combination of these processes (as observed, e.g., on hyperosmotic or pH shifts). For further details, see the text.

Besides this multifaceted regulation of σS synthesis, there is also control of σS degradation. In cells growing on minimal medium, σS (which is produced at a low but measurable rate) is degraded with a half-life between 1 min and a few minutes (114, 144, 148, 208). However, in response to stresses such as starvation (114, 208), shift to hyperosmolarity (148), the classical heat shock (144), or pH downshift to pH 5 (18), σS proteolysis is considerably reduced or even completely inhibited. As a consequence, σS rapidly accumulates in the cell. The kinetics of this stabilization can be very rapid (on hyperosmotic shift, σS is strongly stabilized within a few minutes [148]) or can take somewhat more time (as, e.g., after heat shock [144]). This again indicates that even in cases where the same level of σS regulation is affected by different stress conditions, the regulatory mechanisms involved are likely to be different.

In recent years, considerable progress has been made in identifying (i) cis-acting regulatory regions at the DNA, mRNA, or protein levels; (ii) trans-acting factors such as regulatory proteins or regulatory RNAs; and (iii) additional large or small molecules that modulate σS regulation at these different levels. In general, the closer to the rpoS gene, its mRNA, or the σS protein itself these factors act, the better understood is their molecular mechanism of action. By contrast, the upper parts of the corresponding signal transduction pathways have remained more elusive. It is, however, already clear that these pathways do not operate independently and in parallel until they finally converge to influence, e.g., rpoS mRNA secondary structure or the activity of a specific σS recognition factor for proteolysis. Rather, these pathways are highly interconnected, such that specific stress conditions can influence the cellular σS concentration by multiple mechanisms. Moreover, specific components of these pathways also control each other. Thus, σS is controlled by a complex signal transduction network whose redundancy, additiveness, and internal feedback regulatory loops are crucial for its admirable signal-integrative power (and probably its nonlinear behavior) but at the same time have made life difficult for researchers trying to elucidate these pathways.

REGULATION OF rpoS TRANSCRIPTION

Soon after σS had been recognized as a stationary-phase regulator that was itself induced in stationary phase (113), it became clear that much of its regulation was due to posttranscriptional mechanisms (114, 127, 135). Although σS protein levels are very low in exponentially growing cells, relatively high levels of rpoS mRNA are present and do not seem to change in response to several stresses that actually result in strongly elevated σS protein levels. Therefore, attention has focused on the control of rpoS translation and σS proteolysis (see below) whereas rpoS transcription has remained insufficiently characterized. Nevertheless, transcriptional regulation of rpoS occurs, e.g., during the gradual decrease in growth rate when cells grow in rich medium and finally enter stationary phase. Under these conditions, rpoS transcription is activated approximately 5- to 10-fold (113, 114, 135, 153, 190, 208).

Promoters Contributing to rpoS Transcription

Several promoters are involved in rpoS transcription (Fig. 2). Two transcripts can be detected by Northern analysis (8). Polycistronic nlpD-rpoS mRNA originates from two closely spaced promoters (nlpDp1 and nlpDp2) upstream of the nlpD gene (112, 115), which encodes a lipoprotein of unknown function (87, 115). Another promoter (rpoSp) is located within the nlpD gene and produces a monocistronic rpoS mRNA with an unusually long nontranslated 5′ region of 567 nucleotides (112, 208). Studies with transcriptional fusions that included a 5′ deletion analysis indicated that this transcript is the major rpoS mRNA (112). Moreover, rpoSp accounts for activation of transcription in Luria broth-grown cells during entry into stationary phase (112, 208). The NlpD protein is not stationary phase induced, which indicates that the nlpD promoters are not growth phase regulated (115).

FIG. 2.

Transcriptional control regions upstream of the rpoS gene. (A) The nlpD-rpoS operon is located at 61.76 min on the E. coli chromosome, where it is trancribed in counterclockwise direction. (B) The operon promoters (nlpDp1 and nlpDp2) contribute to basal expression of rpoS but are not regulated by growth rate or growth phase (115). (C) The major rpoS promoter (rpoSp) is located within the nlpD gene, is flanked by two putative cAMP-CRP binding sites (CRP box I and II), and is subject to stationary-phase induction when cells are grown on rich medium (112). Broken lines in panel A indicate the relative positions of the sequences shown in panels B and C.

In other enteric bacteria, Vibrionaceae members, and pseudomonads studied so far, the nlpD and rpoS genes are always linked, which suggests similar transcriptional regulation to that in E. coli. Downstream of rpoS, however, variations are quite common and even occur between different E. coli strains (28, 37, 83). However, nlpD can occur alone in bacteria that do not possess an rpoS gene, such as Haemophilus influenzae (55).

Trans-Acting Factors Controlling rpoS Transcription

cAMP-CRP and EIIA(Glc).

In strains carrying mutations in cya (encoding adenylate cyclase) or crp (encoding the cyclic AMP [cAMP] receptor protein [CRP], also called the catabolite activator protein), σS levels and the activities of transcriptional rpoS::lacZ fusions are already high in exponential phase, indicating that cAMP-CRP is a negative regulator of rpoS transcription. In the cya mutant, this phenotype can be reversed by the addition of external cAMP (113, 114). However, the mode of action of cAMP-CRP in rpoS transcriptional control seems to depend on the growth phase. Recent evidence indicates that during entry into stationary phase, cAMP-CRP positively controls rpoS transcription (F. Scheller and R. Hengge-Aronis, unpublished results). This may resolve an apparent contradiction between the above-mentioned observation of high log-phase levels of σS in cya or crp mutants (114) and the finding that certain rpoS::lacZ fusions show reduced expression in a cya background (135).

Two putative cAMP-CRP binding sites are present upstream and downstream of rpoSp (Fig. 2), and the role of these potential binding sites is currently under investigation. Whereas the location of the upstream cAMP-CRP box is similar to that in the lac promoter and corresponds to a classical activator position at a class I promoter (31), the location of the second cAMP-CRP box downstream of the transcriptional start site may suggest an inhibitory action. In addition, cAMP-CRP may also have an indirect effect on rpoS expression, since cya or crp mutants exhibit a reduced growth rate, which in turn can affect rpoS transcription, as mentioned above.

Adenylate cyclase activity is positively modulated by the crr-encoded EIIA(Glc), which is the soluble part of the glucose-specific EII component of the phosphotransferase system for solute uptake. Consistent with this, a crr mutation results in elevated σS levels during exponential phase, which reflects increased rpoS transcription as well as increased rpoS translation. The former can be suppressed by cAMP addition, indicating that EIIA(Glc) affects rpoS transcription through its modulation of adenylate cyclase activity (217). Phenotypically, the crr mutant thus seems to mimic the log-phase behavior of the cya mutant.

Polyamines stimulate adenylate cyclase expression at the level of translational initiation, and at the same time they lead to 2.3- and 4-fold increases of the cellular levels of σS and σ28, respectively (235). This polyamine-induced upregulation of σS may mimic the positive effect of cAMP-CRP on rpoS transcription during entry into stationary phase.

The GacS-GacA two-component and Las-Rhl quorum-sensing systems in pseudomonads.

GacA is a two-component response regulator in various Pseudomonas species that has long been known to positively affect the production of secondary products such as antibiotics, toxins, and lytic exoenzymes during entry into stationary phase (117, 123, 178). The cognate histidine sensor kinase is the GacS (LemA) protein (85, 178). What is actually sensed by GacS has not been clarified. Homologs of GacA are present in Salmonella (SirA, which controls certain virulence genes [93]) and E. coli (YecB or UvrY [see below]). The GacS-GacA two-component system is at the top of a regulatory cascade that controls the LasI-LasR quorum-sensing system, which in turn regulates a second quorum-sensing system, RhlI-RhlR (110, 167, 176). These quorum-sensing systems are crucial for the control of virulence factors, exoenzymes, and stress-protective proteins as well as for the formation of biofilms (62, 74, 111, 159, 232); for summaries of quorum-sensing systems, see references 61 and 231).

Mutations in gacA or gacS also result in a more than 80% reduction of σS levels and equally reduced expression of a transcriptional rpoS::lacZ fusion specifically during transition into stationary phase (227). Whether this regulation of rpoS by the Gac system is direct or indirect has not been demonstrated. There are also conflicting data about how rpoS is linked to the Las-Rhl cascade. An earlier study had indicated that rpoS is under positive control of both the Las and Rhl systems (110). More recently, however, rpoS was found not to be affected by rhl mutations; in contrast, rhlI is upregulated in rpoS mutants, indicating that σS is a negative regulator of the Rhl system (228). This fits with the observation that pyocyanin and pyoverdin are overproduced in rpoS mutants (205), since these virulence-associated factors are under positive control of the Rhl system (27).

In contrast to the situation in Pseudomonas, the GacA homolog YecB (UvrY) in E. coli appears not to be involved in the control of rpoS expression. Even though YecB overproduction stimulated the expression of transcriptional and translational rpoS::lacZ fusions and resulted in a twofold-higher level of σS specifically during transition into stationary phase, a yecB::cat knockout mutation did not alter the expression of these rpoS::lacZ fusion, nor were σS levels affected (Kampmann and Hengge-Aronis, unpublished). While σS plays similar physiological roles in E. coli and Pseudomonas (188, 205), differential control by YecB-GacA may reflect the different environmental conditions characteristic of the natural habitats of these bacteria.

BarA, a histidine sensor kinase in search of a response regulator.

The E. coli homolog of GacS is a hybrid sensor kinase called BarA (40% identity and 59% overall similarity at the amino acid level to P. aeruginosa GacS). BarA was previously found as a multicopy suppressor of an envZ mutation; i.e., when present at high levels, BarA is able to cross-phosphorylate the response regulator OmpR and thereby activate porin synthesis (88, 154). Under the name AirS, BarA has also been identified as a virulence factor in uropathogenic E. coli (241). There is evidence that BarA plays a positive role in rpoS expression. A strain with a lacZ insertion in the chromosomal copy of barA, which was originally isolated as a hydrogen peroxide-sensitive mutant, exhibits reduced levels of σS (150, 151). In the mutant, rpoS mRNA levels were reduced during exponential phase but were normal in stationary phase. Therefore, BarA was suggested as a positive regulator of rpoS transcription (150). By specifically affecting rpoS mRNA levels in exponential phase, this control may determine the range within which σS levels can be modulated by posttranscriptional control mechanisms in response to various stress conditions.

The homology to the GacS-GacA system, as well as recent biochemical data (166), suggests that BarA is a cognate sensor kinase for YecB. Therefore, it seems surprising that BarA but not YecB (see above) is involved in σS control. However, it is possible that BarA acts on more than one response regulator with an unknown target response regulator being involved in rpoS control. BarA (GacS) belongs to the complex “built-in phosphorelay” sensor kinases in which sensor, transmitter, receiver, and histidine-containing phosphotransfer domains are combined in a single polypeptide chain. In view of their multiple interactions, phosphorelay components seem especially adequate for establishing such phosphotransfer networks.

PsrA in pseudomonads: a TetR-like regulator.

A search for insertional mutations that downregulated the expression of a transcriptional rpoS::lacZ fusion in P. putida yielded a mutant defective in a gene termed psrA (for “Pseudomonas sigma regulator”), which encodes a TetR repressor-like regulatory protein. psrA is required for increased rpoS transcription during entry into stationary phase and is negatively autoregulated (104). Whether this control of rpoS is direct or indirect is currently unknown.

Role for Polyphosphate in rpoS Regulation

Inorganic polyphosphate occurs in most microorganisms and often accumulates in stationary phase or under other stress conditions (106, 107). In E. coli, the actual polyphosphate level is the result of a balance between synthesis (catalyzed by polyphosphate kinase, encoded by ppk) and degradation (catalyzed by exopolyphosphatases, encoded by ppx and gppA) (106). Polyphosphate accumulation is positively affected by the “alarmone” guanosine 3′,5′-bispyrophosphate (ppGpp; see below), which seems to inhibit the ppx-encoded exopolyphosphatase (108). Polyphosphate stimulates Lon-mediated degradation of ribosomal proteins; i.e., it may be crucial for gaining access to intracellular amino acid pools under conditions of sudden carbon or amino acid starvation (109).

Polyphosphate-free ppk mutants are multiple stress sensitive and impaired in stationary phase survival (36, 175). Consistent with these phenotypes, σS levels as well as the expression of a transcriptional rpoS::lacZ fusion are reduced in a strain that overproduces yeast exopolyphosphatase and is therefore depleted of polyphosphate (195). These findings indicate that polyphosphate somehow stimulates rpoS transcription and thereby contributes to stationary-phase induction of rpoS (which in rich media is partly due to increased rpoS transcription). However, polyphosphate fails to stimulate rpoS transcription in vitro and therefore may exert an indirect influence in vivo (195).

Small Molecules That Influence rpoS Transcription

ppGpp.

ppGpp levels in E. coli strongly increase in response to amino acid limitation (triggering the stringent response) or starvation for carbon, nitrogen, and phosphorus sources. Amino acid limitation causes a rise in the cellular level of uncharged tRNA, which is sensed by the ribosome-associated RelA protein (ppGpp synthase I). Under other starvation conditions, ppGpp synthesis is mediated by SpoT (ppGpp synthase II). SpoT is also the degrading enzyme. Only relA spoT double mutants are completely devoid of ppGpp (32).

Such ppGpp-free mutants contain strongly reduced σS levels. Glucose and phosphate starvation, but not amino acid limitation, still induce σS in these mutants (albeit to lower levels than in the wild type). On the other hand, σS accumulation can be triggered by artificially stimulating ppGpp accumulation (64).

ppGpp affects rpoS transcription, as demonstrated with transcriptional rpoS::lacZ fusions (112). However, ppGpp does not seem to specifically target the promoters involved in rpoS transcription, since a transcriptional rpoS::lacZ fusion construct, in which these natural promoters were deleted (and basal expression was due to vector-dependent transcriptional readthrough activity), exhibited similarly reduced expression as the promoter-carrying construct in a ppGpp-free genetic background. It was therefore proposed that in the case of rpoS, ppGpp may affect transcriptional elongation or transcript stability rather than transcriptional initiation (112). In the absence of ppGpp, starvation may result in an uncoupling of transcription and translation, which may lead to increased premature termination, as demonstrated for lacZ mRNA (52, 219, 220).

It is also unclear whether this ppGpp effect is direct or indirect. An increase in the cellular ppGpp content results in the accumulation of polyphosphate, which also stimulates rpoS transcription by an unknown mechanism (see above). It is therefore conceivable that ppGpp acts indirectly via polyphosphate. The finding that a polyphosphate-depleted strain is not impaired in ppGpp accumulation but contains strongly reduced σS levels is consistent with such an indirect mode of action (195). Clearly more research is required to elucidate these relationships at the molecular level.

Is rpoS expression controlled by quorum sensing?

Sometimes high cell density in a bacterial population turns out to be the inducing signal for “stationary phase-inducible” genes. The classical “quorum-sensing” system is the lux system in Vibrio fischeri, where a membrane-permeable acylated homoserine lactone (acylated HSL, the “autoinducer”) is produced by LuxI and accumulates in the medium. Beyond a certain threshold concentration, the autoinducer binds to and activates LuxR, which stimulates the expression of the luxI and luxR genes themselves and the luciferase structural genes (60, 61, 187). Numerous bacterial species contain homologs of the LuxI-LuxR pair, which control a wide variety of output functions (recently summarized in reference 231). Other types of quorum-sensing systems use different kinds of inducing molecules; e.g., gram-positive species use small peptides in general. A hallmark of all these systems is their inducibility on addition of conditioned medium, i.e., spent supernatant obtained from a culture grown to relatively high cell density, which contains the inducing molecule in sufficient concentration.

With respect to rpoS induction by conditioned medium, conflicting data have been reported. Such induction (approximately fourfold) was observed for a transcriptional rpoS::lacZ fusion, and acetate was proposed as the inducing agent (190). With a different rpoS::lacZ operon fusion present in multiple copies, fourfold induction was also found with conditioned Luria broth medium (153), but when the same fusion was present in single copy in the chromosome, induction by spent medium was reduced to a mere 1.6-fold (197). In another study, a transcriptional rpoS::lacZ fusion was found to be completely unaffected by conditioned medium (63). With a set of single-copy transcriptional and translational rpoS::lacZ fusions (114), very little if any induction was obtained, no matter whether conditioned rich or minimal medium was used, and even spent medium freshly prepared in parallel with the induction experiments (to compensate for potential instability of a putative inducer) had little effect on rpoS expression levels (D. Traulsen and R. Hengge-Aronis, unpublished results). It therefore seems that quorum sensing mediated by some excreted medium component does not play a significant role in the regulation of rpoS in E. coli. Therefore, translational induction of rpoS beyond a certain cell density (114) may also be connected to some metabolic alterations rather than to quorum sensing mediated by an excreted substance (see below). The finding that rpoS itself is probably not or is only weakly controlled by quorum sensing does not preclude certain σS-transcribed genes from being subject to such regulation, which may affect the promoters of these genes directly (11, 197, 206).

The E. coli genome sequence (23) does not reveal obvious homologs of genes encoding known acyl-HSL synthases of the LuxI and AinS families (17, 61, 66). There is, however, a LuxR-related protein, SdiA, which may respond to an unidentified acyl-HSL (63, 197). Expression of SdiA itself, as well as the activity of a known target promoter, ftsQp2, responds negatively to conditioned (E. coli) medium, which may mean that the potential of E. coli to respond to an acyl-HSL via SdiA (and thereby activate cell division genes) is downregulated in stationary phase.rpoS, however, does not seem to be under the control of SdiA (63).

Homoserine lactone and homocysteine thiolactone.

Nonacylated HSL has been implicated in rpoS control in E. coli. It was reported that a thrA metL lysC mutant, which is deficient early in the branched pathway that leads to biosynthesis of lysine, methionine, threonine, and isoleucine, had reduced σS levels, which apparently could be suppressed by exogenously adding HSL (at concentrations up to 1 mM). This suppression was weaker in the presence of multiple copies of RspA. Such overexpression also reduced stationary-phase expression of an rpoS::lacZ fusion (which apparently was a transcriptional fusion). Therefore, it was hypothesized that HSL is an inducer for rpoS expression and that RspA may be involved in the degradation of HSL (86). At the time this work was published, this seemed to be in line with quorum-sensing studies that demonstrated the role of acylated HSLs in gene regulation. However, it is now known that free HSL is not the precursor for acylated HSLs that serve as autoinducers in LuxI-LuxR-like systems (72, 165) but, rather, plays the role of an intracellular metabolite. Moreover, there is good evidence against quorum sensing affecting rpoS regulation (see above).

More recently it was found that HSL (up to 1 mM) added to wild-type E. coli did not induce rpoS (197), and the RspA overproduction effect on rpoS is now considered nonphysiological (67). Nevertheless, the idea that RspA may degrade HSL is consistent with the recent observation that RspA-overproducing strains indeed seem to have increased homoserine and decreased HSL levels (U. Sauer, personal communication). Unexpectedly, these strains actually show elevated σS levels, which would not seem consistent with HSL being an inducer for rpoS (226).

Another recent study (67) implicates specifically the methionine biosynthesis pathway in σS control. A metE mutant, which is deficient for conversion of homocysteine to methionine and therefore accumulates homocysteine thiolactone (HCTL), exhibits increased σS levels. Moreover, an asd mutant, which is deficient earlier in methionine biosynthesis (and therefore also in homocysteine and HCTL formation), shows decreased σS levels, and this phenotype could be suppressed by exogenous HCTL (1 mM) (67). During entry into stationary phase in minimal glucose medium, a 2.5-fold accumulation of HCTL was observed in wild-type cells (67). Under these conditions, however, there is little if any activation of rpoS transcription, but σS accumulation is due to posttranscriptional control (114; also see below). Unfortunately, HCTL effects were demonstrated by assaying for σS protein only, and so the level of control affected remains open to speculation (67).

In summary, these studies (67, 86) have demonstrated that amino acid biosynthetic pathways, in particular the branch that leads to methionine (with HCTL as the putative effector), can influence the expression of rpoS. It has not been clarified, however, whether this effect is at the level of rpoS transcription, and the underlying molecular mechanism remains unknown.

Acetate and other weak acids.

In an early study that reported the induction of a transcriptional rpoS::lacZ fusion in spent culture supernatant, the fermentation product acetate (used at 40 mM) was found to activate rpoS expression (190). In another study, however, acetate did not have an effect on rpoS expression (153). The studies agreed that benzoate (10 or 25 mM) has an inducing effect, and it was concluded that this may be so in general for weak acids with a pKa of 4.8 to 4.9 (40 mM propionate was also found to be effective) (153, 190). However, a translational rpoS::lacZ fusion did not show this induction by weak acids (190). One has to take into account, however, that these studies were performed before the advent of limitless precise PCR cloning, and therefore reporter gene fusions had to be constructed in rather complicated ways and often remained incompletely characterized. To finally settle the issue of weak acids in rpoS control, these experiments would have to be repeated and expanded with the precisely characterized systems available today.

Recent genome-wide analyses have shown that addition of acetate to buffered medium results in the activation of various σS-dependent genes and proteins, but unfortunately the cellular concentration and regulation of σS itself were not studied under these conditions (7, 100). Similar conditions resulted in increased synthesis of σS in Salmonella, but the underlying control mechanisms seemed at least in part posttranscriptional (39).

Cellular NADH-to-NAD+ ratio.

Experiments with a transcriptional rpoS::luxAB fusion in a nuoG mutant background (which is defective in a subunit of NADH dehydrogenase) suggested that a high NADH-to-NAD+ ratio somehow downregulates rpoS transcription. Consistent with this proposal, rpoS transcription is low under oxygen-limited (microaerobic) growth conditions, where NADH levels should increase due to the scarcity of oxygen as an electron acceptor for respiration (194). The mechanistic basis of this effect is unclear.

REGULATION OF rpoS TRANSLATION

Initial evidence for posttranscriptional regulation of rpoS was provided by clearly different patterns of expression of transcriptional and translational rpoS::lacZ fusions (114, 127, 135). Translational rpoS::lacZ fusions can actually reflect regulation of rpoS translation as well as of σS proteolysis (114, 148, 192). The latter can be excluded by using translational fusions that contain fewer than 173 N-terminal codons of rpoS, since an essential proteolytic recognition element is located at and around K173 in σS (20; also see below).

Translation of rpoS mRNA is stimulated by a shift to hyperosmolarity (114, 148), by low temperature (199), by a shift to acidic pH (pH 5; Kampmann and Hengge-Aronis, unpublished), or during late exponential phase when a growing culture reaches a certain cell density (114). After the onset of carbon starvation, i.e., on entry into stationary phase, rpoS translation is reduced again, and further increases in σS levels are then due to inhibition of σS degradation, as described below (114).

Role of rpoS mRNA Secondary Structure

There are two species of rpoS mRNA of clearly different lengths (the locations of relevant promoters are given in Fig. 2). Polycistronic nlpD-rpoS mRNA can have two different 5′ ends since there are two closely spaced promoters upstream of nlpD (115). Monocistronic rpoS mRNA originates from rpoSp within the nlpD gene and contains an unusually long nontranslated 5′ region of 567 nucleotides (112, 208). This leader sequence is functionally important, since 5′ deletions in it reduce rpoS expression (38).

Even under conditions where σS protein is hardly detectable, cells produce fair amounts of rpoS mRNA, which seems to remain constant under the translation-inducing conditions mentioned above (8, 147). It is generally believed that control of the rate of translation of already existing complete rpoS mRNA is based on an mRNA secondary structure in which the translational initiation region (TIR) is based paired and therefore not sufficiently accessible to ribosomes (under noninducing conditions). Certain stress signals are hypothesized to trigger changes in this mRNA secondary structure that allow more frequent translational initiation. However, the actual appearance of this rpoS mRNA structure is still largely a matter of speculation.

Theoretical predictions generated with the MFOLD computer program (using complete or partial rpoS mRNA sequences) indicate that approximately 340 nucleotides at the 5′ end of rpoS mRNA fold into an very stable and complex cruciform-type structure (Traulsen and Hengge-Aronis, unpublished). Further downstream, the putative structures are somewhat less stable and the TIR has the potential to fold into two energetically almost equivalent principal structures. One is characterized by a large hairpin that includes the Shine-Dalgarno sequence. There is genetic evidence against this structure playing a role in rpoS translational control (S. Bouché and R. Hengge-Aronis, unpublished results). In the second putative structure, the region around the Shine-Dalgarno sequence is partially base paired to an “internal antisense” region located further upstream, with a relatively long and probably internally structured intervening sequence. There are, however, several theoretical possibilities for the exact location of the “internal upstream antisense” region (Traulsen and Hengge-Aronis, unpublished). Several variations of this second theoretical structure have been published (30, 38, 120, 131), and it is generally believed that this structure may come close to the in vivo reality under noninducing conditions. The only preliminary experimental evidence that such an “internal upstream antisense” structure is in principle correct is provided by two different complementary double point mutations, which showed wild-type expression levels (although one double mutant altered the regulatory pattern, in particular Hfq dependency [see below]) (30, 38). However, the exact details of the in vivo rpoS mRNA secondary structure still await experimental clarification.

In fact, the problem of the correct in vivo rpoS mRNA secondary structure is more complex than, e.g., in the related case of rpoH mRNA, which encodes the heat shock sigma factor σ32.rpoH mRNA folds into a translationally incompetent secondary structure also involving an internal antisense element, which opens up upon heat shock, resulting in a directly temperature-triggered translational induction of rpoH (summarized in reference 236). This process does not involve any regulatory proteins (143), and the experimentally demonstrated rpoH mRNA secondary structure is the one theoretically predicted (142). In rpoS mRNA, however, several proteins and small regulatory RNAs are positively or negatively involved in translational control, and at least some of these can directly bind to rpoS mRNA in vitro (see below). Therefore, theoretical calculations or in vitro structural probing based on rpoS mRNA alone is likely to yield incorrect or at least incomplete results. It seems that the only way of settling the issue of the correct rpoS mRNA secondary structure and its dynamics may be in vivo structural probing. Wild-type strains under different conditions as well as various mutants with cis- or trans-regulatory defects in rpoS translation will have to be tested in such experiments. However, in view of the technical difficulties of such an endeavor, especially with a large mRNA with complex and semistable secondary structure, it is not surprising that such data have yet to be reported for rpoS mRNA.

trans-Acting Factors Involved in rpoS Translation

The RNA binding protein Hfq (HF-I).

More than 30 years ago, the Hfq protein was identified as a host factor (host factor I [HF-I]) essential for replication of phage Qβ RNA (56, 57). Hfq acts as an accessory component of Qβ replicase that binds to several sites in Qβ RNA including the 3′ end (14, 139, 193). Hfq is required for initiating replication specifically of the Qβ RNA plus strand, probaby by affecting the secondary structure at its 3′ end (191). The role of the ribosome-associated (45) Hfq protein in E. coli physiology, however, remained enigmatic until an hfq mutant was observed to have a very pleiotropic phenotype (214), which resembles the phenotype of an rpoS mutant (147). This led to the discovery that Hfq is required for efficient rpoS translation (29, 146). While this can explain the pleiotropy of hfq mutants, Hfq also has physiological functions that are independent of σS (147). In particular, it stimulates the degradation of ompA, miaA, mutS, and its own mRNA (215, 221, 222). Hfq is a 11.2-kDa oligomer-forming protein (57). While this review was under revision, Hfq was reported to form hexameric rings homologous to eukaryotic Sm and Lsm proteins, which occur in the spliceosome and play various roles in mRNA processing (140, 240).

The molecular function of Hfq in rpoS translation is still relatively speculative. Epistasis experiments, where hfq mutations were combined to other mutations or overproduction constructs that affect rpoS translation indicated that Hfq is probably directly involved in translation initiation; i.e., it acts close to or at the level of rpoS mRNA (130, 146, 200, 217, 238). rpoS mRNA coimmunoprecipitates with Hfq in cellular extracts (238). Hfq also binds with high affinity to several sites in a large 5′ fragment of rpoS mRNA synthesized in vitro, which is predicted to fold into the same secondary structure as the wild-type mRNA (Traulsen and Hengge-Aronis, unpublished). A 5′ deletion analysis of rpoS mRNA indicated that regions relatively far upstream of the TIR are important for translational stimulation by Hfq (38). Thus, Hfq binds rpoS mRNA, just as it is able to bind Qβ RNA. However, Hfq does not show similarity to RNA helicases. This makes an active processive unfolding activity unlikely. Alternatively, by binding to a few crucial positions of rpoS mRNA, Hfq may affect the equilibrium between possible alternative secondary structures that are differentially productive for translational initiation. Thus, Hfq may stabilize a semistable rpoS mRNA secondary structure, which can easily open up when some additional stimulating factor is induced or activated (e.g., HU protein or DsrA-RNA, [Fig. 3; see below]). Yet another possibility is that Hfq does not necessarily affect rpoS mRNA secondary structure (although this would not be excluded) but acts like a “platform” bound to rpoS mRNA that recruits additional factors involved in rpoS translational control. The finding that single potentially base-pair-disrupting point mutations in the TIR or in the region likely to be base paired to the TIR result in increased rpoS translation and reduced Hfq dependence (30) appears consistent with both of these putative mechanisms of Hfq action.

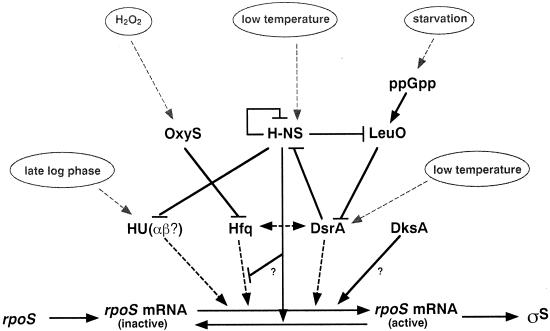

FIG. 3.

The rpoS translational control network. rpoS mRNA is thought to occur in at least two different conformations, one being a more closed structure with the translation initiation region base paired to an upstream internal antisense element, and the other being a more open and translationally competent structure. The translation-stimulating factors Hfq, HU, and DsrA RNA can bind to rpoS mRNA (indicated by broken heavy lines) and together probably drive it into the translationally competent structure. The other components shown are likely to act more indirectly (for further details, see the text).

It was reported that Hfq can also bind to DsrA RNA (200), which is a small regulatory RNA partially complementary to rpoS mRNA that stimulates rpoS translation above all at low temperature (see below for details). Therefore, it was suggested that Hfq may influence DsrA action by forming an active DsrA-Hfq complex and/or by altering DsrA structure (200). However, at 37°C an hfq mutation reduces rpoS translation much more than a dsrA mutation does (146, 199), indicating that Hfq does not act exclusively through DsrA. A hypothetical model consistent with all data available would be that Hfq bound to rpoS mRNA recruits DsrA into a ternary complex (in which secondary structures of rpoS mRNA and/or of DsrA could also be altered) and thereby facilitate translational stimulation by DsrA. In this complex, several Hfq molecules or oligomers bound to different sites on rpoS mRNA could be present. During revision of this review, ternary-complex formation with Hfq was also reported for flhA mRNA and OxyS RNA (240) as well as for galK mRNA and spot 42 RNA (140). Both studies came to the conclusion that the role of Hfq (and perhaps of Sm and LSm proteins in general) is to facilitate specific RNA-RNA interaction. Thus, Hfq could stimulate any process dependent on such RNA-RNA interactions.

If so, stress signal input into rpoS translational control would not necessarily be via a control of the activity or the level of Hfq itself. In fact, hfq mutants show overall reduced activity of translational rpoS::lacZ fusions or rates of σS synthesis (as measured in pulse-labeling experiments), but regulation by stress signals, e.g., by hyperosmotic shift, is not abolished (146). This suggests that stress signals affect the cellular concentrations or activities of the specifically translation-activating or inhibiting components (e.g., DsrA and OxyS) that can join the rpoS mRNA-Hfq complex. These components indeed exhibit pronounced regulation (see below).

HU: a nucleoid protein that also stimulates rpoS translation.

Protein HU is a major protein component of the bacterial nucleoid. It affects overall nucleoid structure and topology but also participates in specific gene regulation, DNA recombination, and DNA repair (155). In addition, HU is required for optimal survival during prolonged starvation (35). In members of the Enterobacteriaceae and Vibrionaceae, two homologous subunits (HUα and HUβ [encoded by hupA and hupB, respectively]) contribute to the formation of active HU protein (158). During growth, the HUα2 homodimer is abundant, whereas during late exponential phase, HUβ is induced and HUαβ heterodimers are formed in E. coli (35). An HU-deficient hupAB double mutant exhibits strongly reduced σS levels because of reduced rpoS translation (12).

In vitro, HU binds with high affinity to a small rpoS mRNA fragment (150 nucleotides covering the TIR and the upstream antisense region probably base paired to the TIR) (12) as well as to a larger fragment (covering more than 700 nucleotides starting from the original mRNA 5′ end) that also binds Hfq (Traulsen and Hengge-Aronis, unpublished). As a DNA binding protein, HU has a strong preference for nicked or cruciform DNA (94). Thus, HU may preferentially recognize secondary-structure elements, such as pronounced bends or kinks, which also occur in RNA secondary structure. HU may directly alter the rpoS mRNA secondary structure, but it is unknown how this effects relates to that of Hfq or of other components that affect rpoS translation (Fig. 3).

Since the induction of HUβ (which is under the negative control of the nucleoid protein FIS [34]) correlates with stimulation of rpoS translation during late exponential growth phase, and specifically since the HUαβ heterodimer is required for stationary phase survival (35), it is tempting to speculate that the heterodimer is the form of HU involved in rpoS translation. However, this hypothesis has yet to be tested experimentally. Nevertheless, phylogenetically, the occurrence of an HUαβ heterodimer correlates with the occurrence of σS (with the exception of the Pseudomonas group, but regulation of σS is significantly different in several aspects in this group).

H-NS and StpA: histone-like proteins acting as RNA chaperones?

H-NS is an abundant histone-like protein with functions in nucleoid organization as well as in gene regulation, where in nearly all cases it acts as a repressor or silencer that can form large nucleoprotein complexes. StpA is a closely related paralog of H-NS with similar properties (although it seems more efficient as an RNA chaperone). Just as with HUα and HUβ, homo- as well as heterooligomers are formed by H-NS and StpA (for reviews, see references 9, 43, and 230).

H-NS-deficient mutants exhibit strongly increased σS levels, which in exponential phase are already similar to those reached by the wild-type only in stationary phase or under other stress conditions (15, 234). In these hns mutants, the rate of rpoS translation is enhanced and proteolysis of σS is strongly reduced or even abolished (234). The slow growth and genetic instability typical of hns mutants are at least partially connected to these abnormally high σS levels, since they can be suppressed by mutations in rpoS (15).

Mechanistically, it is still unclear how H-NS downregulates rpoS translation, but there are a number of possibilities for direct or indirect influences (Fig. 3). Since H-NS can bind to RNA (although high-affinity specific binding has not yet been demonstrated [40, 48]), it may directly interact with rpoS mRNA and affect its secondary structure, perhaps in a transient way as an RNA chaperone. H-NS may also counteract the effects of positive regulators of rpoS translation such as Hfq and/or HU. These possibilities are not mutually exclusive, since the positively acting factors and H-NS may have opposite effects on the equilibrium between two rpoS mRNA conformations that can be translated with different efficiencies (Fig. 3). Consistent with H-NS counteracting Hfq, H-NS deficiency has no effect on rpoS translation in a hfq mutant background (146). H-NS and HU in general seem to play antagonistic roles, e.g., in determining DNA supercoiling (44) or in the expression of certain genes such as ompF (41, 164). Thus, it is also possible that H-NS inhibits rpoS translation by affecting the cellular level of HU or by directly counteracting the stimulatory effect of HU on rpoS translation.

Another candidate for promoting rpoS translation is the H-NS homolog StpA. Several studies have shown that StpA levels are significantly lower than H-NS levels (201, 239), although one report gives approximately equal numbers of H-NS and StpA molecules per cell (10). It seems clear, however, that H-NS and StpA regulate each other negatively at the level of transcription. Therefore, an hns mutant should have an increased cellular concentration of StpA (201, 239). Moreover, StpA is upregulated after a hyperosmotic shift (58). Thus, increased StpA levels appear to correlate with increased rpoS translation. Since StpA can act as a RNA chaperone (40), it was tempting to speculate that it may stimulate rpoS translation. However, high-log-phase levels of σS in an hns mutant were not suppressed by introducing an stpA mutation, and also osmotic induction of rpoS translation was normal in a stpA mutant (Bouché and Hengge-Aronis, unpublished). Therefore, under these conditions, StpA does not seem to play a role in rpoS translation. This, however, does not exclude a potential involvement of StpA under different conditions or in other genetic backgrounds.

Role of small regulatory RNAs in rpoS translation: DsrA, OxyS, and RprA.

Several small regulatory RNAs with important fine-tuning functions in complex regulatory circuits have been identified in E. coli (summarized in reference 1), and three very recently published studies suggest that small regulatory RNAs in E. coli are much more common and significant than previously thought (6, 179, 224). rpoS translation seems to be an especially prominent target for such regulation, with three regulatory RNAs having been found so far. While DsrA and RprA promote rpoS translation, OxyS has an inhibitory function.

DsrA was originally identified as a multicopy suppressor of H-NS-mediated silencing of the rcsA gene in E. coli (198) and was then found to be essential for increased rpoS translation at low temperature (199). DsrA is a stable 87-nucleotide RNA that folds into a three-stem-loop structure (119, 131). A region covering most of stem-loop 1 and the following single-stranded part of DsrA is complementary to an upstream “antisense element” in rpoS mRNA that is assumed to base pair with the TIR region, suggesting that DsrA functions by an “anti-antisense” mechanism that disrupts intramolecular basepairing in rpoS mRNA (119, 120, 131). DsrA plays only a minor role for rpoS translation in cells grown at 37 or 42°C yet becomes the major stimulating factor at 30°C and especially at 20°C (199). The basis of low-temperature translational induction of σS is the clearly enhanced transcription of dsrA as well as a sixfold-increased stability of DsrA at low temperature (177). DsrA and Hfq were recently reported to interact specifically, and Hfq was suggested to stabilize DsrA as well as to alter its secondary structure in a way that promotes association with rpoS mRNA (200). Whether the formation of such a binary complex facilitates DsrA action on rpoS mRNA or whether Hfq already bound to rpoS mRNA (as described above) recruits DsrA, the result is likely to be a ternary complex (see also above). Hfq may affect the secondary structure of both RNAs such that they optimally interact, and with all partners involved interacting with each other, the complex is probably relatively stable. As a result, the formation of an “open” conformation at the TIR of rpoS mRNA that allows ribosome entry would be facilitated (Fig. 3).

Besides rpoS mRNA, DsrA has at least one other target, hns mRNA. While DsrA was initially thought to act like a conventional antisense RNA interfering with hns translation initiation (120), it now seems likely that a region corresponding to unfolded stem-loop 2 of DsrA forms a coaxial stack with two regions in hns mRNA. Negative regulation of hns expression is a consequence of more efficient degradation of hns mRNA within this complex (118). DsrA is predicted to form similar complexes with argR and ilvIH mRNAs, but an involvement of DsrA in the regulation of these genes has not yet been demonstrated (118).

Multifunctionality exerted by different regions may be common in small regulatory RNAs, since it has also been observed for OxyS. OxyS is a 109-nucleotide regulatory RNA that folds into a similar secondary structure to that of DsrA. As a member of the OxyR regulon, OxyS is induced by oxidative stress (hydrogen peroxide) and acts as a pleiotropic regulator (2). Small regions located in loops 1 and 3 of OxyS control translation of fhlA (which encodes a transcriptional activator) by forming a “kissing complex” with two sites of fhlA mRNA, one of which contains the Shine-Dalgarno sequence (3, 5). By contrast, the rather long A-rich single-stranded region between stem-loops 2 and 3 of OxyS is involved in negative regulation of rpoS translation, although this part of OxyS does not show significant sequence complementarity to rpoS mRNA. Coimmunoprecipitation experiments indicate that OxyS binds to Hfq protein. Thus, OxyS may sequester Hfq or form a translationally incompetent ternary complex with Hfq and rpoS mRNA (238) (Fig. 3). OxyS-mediated translational repression of rpoS may be a fine-tuning mechanism to avoid redundant overinduction of oxidative-stress protective genes (katG, gorA, and dps) that are under dual positive control of OxyR/σ70 and σS. It may also prevent the uneconomical induction of the large multifunctional σS regulon under conditions where the cell has to cope with oxidative stress only, i.e., a situation that can be managed by the stress-specific OxyR-mediated response alone.

The third small regulatory RNA involved in rpoS translational control, RprA, was found as a multicopy suppressor for a dsrA mutation (130). In the dsrA mutant background, an rprA null mutation also reduces hyperosmotic stimulation of rpoS translation. However, in the presence of DsrA, neither RprA overproduction nor its knockout seems to affect rpoS expression. Thus, RprA clearly has the potential to stimulate rpoS translation, but the physiological conditions under which this becomes relevant are unknown. The rprA promoter is under positive control of RcsB, a response regulator that activates capsule synthesis (unpublished evidence mentioned in reference 130). RprA exhibits some sequence complementarity to the upstream “antisense” element that basepairs with the TIR of rpoS mRNA and may thus act similarly to DsrA (M. Majdalani and S. Gottesman, personal communication.

The LysR-like regulator LeuO: a repressor for dsrA expression.

LeuO is a LysR-like regulator (189), which is strongly repressed by H-NS in growing E. coli cells (101). Overproduction of LeuO (either from a multicopy plasmid or in a mutant that carries a Tn 10 transposon immediately upstream of leuO with pout of the transposase gene reading into leuO) reduces rpoS translation, especially at low temperature. This effect is entirely dependent on the presence of DsrA, and LeuO was shown to repress dsrA transcription (101). This regulation is direct since LeuO binding sites have recently been identified in the dsrA promoter region (177). A leuO knockout mutation, however, does not affect increased rpoS translation during late exponential phase or in response to high osmolarity or low temperature. This is not entirely surprising, since under these conditions, leuO expression is repressed or even “silenced” by H-NS (101). However, during entry into stationary phase, leuO is induced in a ppGpp-dependent manner (50). This ppGpp-mediated activation may be indirect, since leuO expression is subject to a “promoter relay” activation mechanism that involves the surrounding ilvIH and leuABCD operons (33, 51). As a consequence, LeuO probably downregulates DsrA in stationary phase. While this may alter the expression of other targets of DsrA, the σS level is not affected (E. Klauck and R. Hengge-Aronis, unpublished results), probably because other σS-inducing mechanisms compensate for the reduced levels of DsrA. When all these results are taken together, the physiological role of LeuO is far from clear. However, a hint may come from the “cryptic” bgl operon, where LeuO can antagonize H-NS-mediated (and under certain conditions also σS-dependent) “silencing” (160, 218). Interestingly, the bgl operon becomes expressed in a mammalian host (97). It is thus conceivable that LeuO plays an important regulatory role in a host environment.

DnaK and DksA: a link to heat shock and chaperones.

The heat shock chaperone DnaK, as well as a protein termed DksA (originally identified as a DnaK suppressor [95]), has been implicated in rpoS translation. A dnaK mutant exhibits a stationary-phase-specific multiple-stress-sensitive phenotype very similar to that observed for rpoS mutants (180, 181). This correlates with reduced σS levels in starving dnaK mutant cells (144, 181). Part of this effect is due to reduced rpoS translation, since it can also be seen with RpoS::LacZ hybrid proteins that are not subject to proteolysis. The mechanism behind this effect remains unknown, but the overproduction of the heat shock sigma factor σ32 in the dnaK mutant does not play a role, since a suppressor mutation that reduces the σ32 level and/or activity does not suppress the dnaK effect on σS (144).

DksA is a putative zinc binding protein with similarity to the transcriptional activator TraR (59) and other prokaryotic and eukaryotic regulators (103). The basis of dnaK suppression by multiple copies of dksA is still unclear, but it was suggested that production of some stress response factors might be involved (16). This is consistent with the more recent finding that dksA mutations in Salmonella exhibit reduced σS induction in stationary phase and after a shift to acidic pH. Work with rpoS::lacZ translational fusions indicated that DksA affects rpoS translation by some not yet characterized mechanism (225). In P. aeruginosa, overexpression of DksA inhibits the expression of rhlI, rhlAB, and lasB (26). This would be in line with a repressing effect of σS on the rhl system (228). However, additional data suggest that this effect of DksA overproduction is not due to upregulation of σS alone (26).

EIIA(Glc): a link to the carbon source and energy supply.

A crr mutant, which is defective in the glucose-specific PTS component EIIA(Glc), contains strongly elevated σS levels. Both transcriptional and posttranscriptional effects contribute to this phenotype (217). Higher expression of a transcriptional rpoS::lacZ fusion is fully suppressed by cAMP addition, indicating that the effect reflects stimulation of adenylate cyclase by EIIA(Glc) and negative control of rpoS transcription by cAMP-CRP (see above). However, high σS levels and increased activity of a translational rpoS::lacZ fusion are not fully suppressed by cAMP addition, nor does this effect of crr disruption disappear in a rssB mutant background, where σS is not degraded. Thus, EIIA(Glc) obviously downregulates rpoS translation by some uncharacterized and perhaps indirect mechanism. Moreover, the phosphorylated form of EIIA(Glc) is required for this activity. However, external addition of glucose, which is known to drastically decrease the level of phosphorylated EIIA(Glc) (207), does not result in σS induction (217). In the absence of phosphotransferase system-mediated glucose uptake, however, phosphorylation of EIIA(Glc) reflects the intracellular phosphoenolpyruvate-to-pyruvate ratio (84). Negative regulation of σS by EIIA(Glc) may thus be a function of this ratio, which depends on the nature of the carbon source and the energy supply in general (217).

The cold shock domain proteins CspC and CspE.

CspC and CspE belong to the CspA cold shock protein family in E. coli, although they are expressed at 37°C and are not temperature regulated (169). Overproduction of these two RNA binding proteins strongly stabilizes and thereby increases the cellular level of rpoS mRNA. Whether this is a direct or indirect effect is currently unknown. Such high rpoS mRNA levels are assumed to translate into higher σS levels, since the σS-dependent genes osmY, dps, proP, and katG are significantly activated. Conversely, a cspC cspE double mutant exhibits reduced osmotic induction of osmY and dps (168). Unfortunately, rpoS mRNA levels were not determined in the osmotic shift experiment, and in general the rates of σS synthesis and the cellular σS level were not monitored directly in this CspC-CspE study. It was previously reported that a shift to high osmolarity does not increase the rpoS mRNA level (146), which would not be consistent with rpoS mRNA-stabilizing factors playing a major role in osmotic regulation of rpoS. Therefore, it is possible that the CspC and CspE effects on osmY and dps expression are direct and do not always reflect the regulation of rpoS (168).

A Small Molecule That Influences rpoS Translation: UDP-Glucose

UDP-glucose has been implicated in σS regulation, since several mutants with defects in central carbon metabolism that result in UDP-glucose deficiency exhibit increased σS levels during exponential growth (24). These defects can be in phosphoglucose isomerase (encoded by pgi), with the mutant growing on fructose, as well as phosphoglucomutase (pgm) or UDP-glucose pyrophosphorylase (galU), with the latter two mutants growing on glucose. Glucose and galactose given in trace amounts to the pgi and pgm mutants, respectively, rapidly replenish the internal UDP-glucose pool and in parallele result in a rapid decrease of σS levels (24). More recent work with transcriptional and translational rpoS::lacZ fusions and direct pulse-chase measurements of σS synthesis and degradation indicate that UDP-glucose specifically affects rpoS translation. Moreover, enhanced σS levels in a galU mutation are observed only with an intact hfq gene, which suggests that UDP-glucose directly or indirectly interferes with Hfq function in rpoS translation (A. Muffler and R. Hengge-Aronis, unpublished results). However, the molecular mechanism of UDP-glucose action has yet to be clarified, and it is also unknown whether the cellular UDP-glucose level changes in response to any stress signals that affect rpoS translation.

rpoS Translational Control Network and Stress Signal Input

When all the regulatory factors involved in rpoS translation are considered together, a highly intertwined network characterized by positive and negative feedback regulation emerges (Fig. 3). The regulatory output of this network under different physiological conditions is difficult to predict, especially when changing environmental conditions affect the cellular levels of indirectly acting and multiply connected components such as H-NS or LeuO. DsrA is obviously a central player, since it affects the two global regulators σS and H-NS, with the latter in turn downregulating σS. Thus, DsrA seems to have a dual positive effect on rpoS translation, one direct and the other indirect via H-NS. DsrA, H-NS, and LeuO also seem to form a negative feedback loop (Fig. 3). The physiological function of this regulatory loop, i.e., its behavior and consequences for rpoS translation when external stress signals affect the level of single components in the loop, is currently not clear.

The complexity of the rpoS translational control network makes it difficult to define stress signal input. The only σS-inducing condition, for which the underlying signal transduction mechanism seems pretty straightforward, is a shift to low temperature (around 20°C). This treatment clearly induces DsrA RNA (177), which in turn has a direct positive effect on rpoS translation as described above. Whether low-temperature induction of H-NS (116) plays any role in rpoS regulation is unclear. Starvation induction of LeuO (50) may be relevant only at low temperature, since LeuO acts by repressing DsrA RNA (101). So far, however, different stress conditions have not been studied in combination. Late-exponential-phase induction of rpoS translation (114) correlates with the induction of HUβ (35), but whether this reflects a causal relationship is a matter of speculation. Finally, the intracellular signal that is triggered by osmotic upshift and stimulates rpoS translation more than fivefold within a few minutes (148) is completely elusive.

As complex as the translational control network may be, it is even further interconnected to the networks that control rpoS transcription and σS stability. If ppGpp stimulates LeuO expression under starvation conditions (50), it may at the same time be a strong positive regulator of rpoS transcription (see above) and a negative regulator of rpoS translation (Fig. 3). The physiological function of this multiple role of ppGpp is currently not clear. Its purpose may be to avoid nonappropriate overexpression of σS under conditions of combined stresses, e.g., in response to starvation at low temperature. Also, EIIA(Glc) affects transcription (by controlling adenylate cyclase activity) as well as rpoS translation. H-NS, on the other hand, represses rpoS translation and at the same time keeps σS protein levels down by somehow stimulating σS turnover (see below). At present, it still seems appropriate and helpful to treat the different levels of σS control as separate “regulatory modules.” In the somewhat longer run, however, their interconnection will have to be taken into account.

REGULATION OF σS PROTEOLYSIS

rpoS transcription as well as translation can be stimulated under certain stress conditions, but even in cells that grow in the relative absence of stress, there is a certain basal rate of σS synthesis. However, the cellular σS level remains low because of rapid degradation (114, 208). During growth in rich medium, rpoS transcription is very low and the steady-state σS level is usually at or below the limit of detection, which makes quantitative analyses of σS synthesis and proteolysis difficult. During growth in minimal medium, however, rates of σS synthesis and turnover can be determined by pulse-chase experiments and σS levels can be quantified by immunoblot analysis. Under these conditions, the σS half-life is between 1 min and several minutes (depending on the carbon source) (114, 144, 148, 192, 208). This rapid turnover sets the stage for various stress conditions affecting σS levels by modulating the rate of σS proteolysis. In general, it seems that relatively threatening stress conditions tend to affect σS degradation, maybe because this allows the most rapid reaction. These stresses include sudden carbon starvation (114, 208), osmotic upshift (148), and shift to acidic pH (18), which result in σS stabilization within a few minutes. On the other hand, the classical heat shock procedure, i.e., a shift from 30 to 42°C, results in a more moderate increase in σS half-life, which takes approximately 20 min to develop (144).

σS Degradation by the Complex ATP-Dependent ClpXP Protease

The ClpXP protease is responsible for σS degradation. ClpXP is a barrel-shaped processive protease consisting of two six-subunit rings of the ATP-hydrolyzing ClpX chaperone, which play the role of substrate-discriminating and unfolding gatekeepers to the inner proteolytic chamber formed by two seven-subunit rings of ClpP (69, 99, 223). Mutations in clpP as well as in clpX result in stabilization of σS (192). Since the clpP and clpX genes constitute an operon (68, 133), the clpP phenotype could in principle have been due to polarity on clpX, but the inability to suppress σS stability in the clpP mutant by providing clpX in trans confirmed that the entire ClpXP complex is required for σS proteolysis (Muffler and Hengge-Aronis, unpublished). Recently, it has been possible to reconstitute σS degradation in vitro, and these experiments have defined ClpXP as well as a specific recognition factor (see below) as essential and sufficient for the basic process of σS proteolysis (243). σS degradation by ClpXP is complete; i.e., no stable degradation products have been observed.

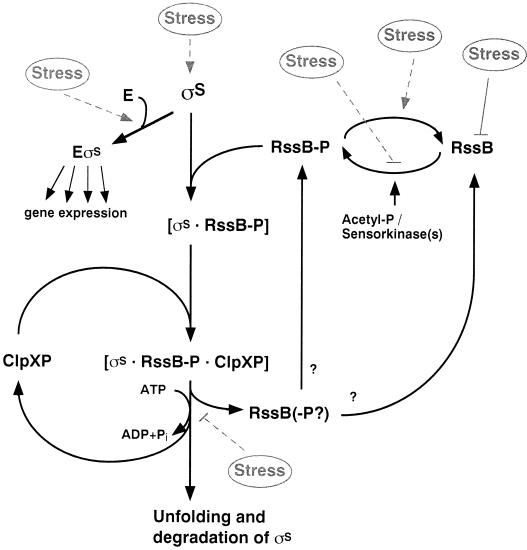

The Response Regulator RssB: a σS Recognition Factor with Phosphorylation-Modulated Affinity

In contrast to other ClpXP substrates, σS cannot be recognized by ClpXP alone, as demonstrated both in vivo and in vitro (145, 243). Rather, a specific recognition factor, the RssB protein (also termed SprE, MviA, or ExpM in different bacterial species), is required (4, 18, 145, 170). A mutation in rssB results in the stabilization of σS (and also of otherwise unstable RpoS::LacZ hybrid proteins) and therefore in elevated σS levels in exponential phase (145, 170). RssB belongs to the two-component response regulator family of proteins, whose activity is modulated by phosphorylation of a conserved aspartyl residue in the N-terminal receiver domain (D58 in RssB). In vitro experiments have shown that phosphorylated RssB directly interacts with σS (20). Phosphorylation as well as σS binding in vitro is lost with RssB variants, in which D58 is replaced by other amino acids, consistent with strains carrying the same mutations exhibiting high levels of stable σS (21, 25, 102). RssB is essential for σS degradation in vitro (243) and may be specific for σS, since turnover of another ClpXP substrate, λO protein, does not depend on RssB (242, 243). In conclusion, the response regulator RssB is an essential, specific, and direct σS recognition factor, whose affinity for σS and therefore whose activity in σS proteolysis are modulated by phosphorylation of its receiver domain.

Like most response regulators, RssB consists of at least two domains, the N-terminal receiver and a C-terminal output domain (the latter could also be more than a single domain). The unique role of RssB in proteolysis is reflected in a unique output domain(s) without similarity to any other protein of known function. In certain response regulators, the output domain alone is mechanistically responsible for the molecular function (most often in transcription initiation), with the receiver domain imposing regulation by phosphorylation-modulated intramolecular inhibition (42, 70). In other cases, phosphorylation of the receiver domain actively contributes to the output function, e.g., by stimulating oligomerization (53, 233) or by exposing an interactive surface in the receiver itself (138, 237). RssB belongs to the latter class, since the isolated N- and C-terminal domains of RssB are functionally inactive in vitro and in vivo; i.e., the N-terminal receiver domain plays an active and positive role in RssB function (102). The molecular details of the RssB-σS interaction remain to be elucidated, but there is evidence that RssB, unlike many other response regulators, does not dimerize or oligomerize on phosphorylation and/or σS binding and that the RssB-σS complex exhibits 1:1 stoichiometry (102).

The cellular concentration of RssB (which in growing cells is around the limit of detection) is the limiting factor for the rate of σS proteolysis in vivo. This means that RssB can be titrated by increased σS synthesis (174). This mechanism can be exploited for stress-induced stabilization of σS (see below). On the other hand, cells have to continuously adjust the expression of RssB to σS in order to maintain σS proteolysis during growth despite controlled or accidential variations in the rate of σS synthesis. This is achieved by a homeostatic feedback coupling that is provided by rssB transcription being dependent on σS (185; Pruteanu and Hengge-Aronis, submitted). These two reports, however, do not agree on the location of the σS-dependent promoter, since Ruiz et al. (185) invoke a promoter just upstream of rssB, which was not found by Pruteanu and Hengge-Aronis (174), who provide evidence that rssB transcription is driven exclusively from the σS-controlled rssAB operon promoter. σS control of rssB expression also results in indirect negative autoregulation of rpoS as well as of rssB, since σS stimulates the expression of a factor, RssB, that initiates σS disappearance (174).

The Turnover Element: the RssB Binding Site within σS

Unlike many other proteolysis substrates, which feature recognition sequences or elements at or close to the N or C termini (96, 229), σS was found to contain a “turnover element” somewhere in the middle of its sequence. Initial evidence for such a proteolysis-promoting element came from the analysis of RpoS::LacZ hybrid proteins carrying N-terminal σS fragments of different lengths. Whereas relatively short hybrid proteins were stable and yielded high β-galactosidase activities in log phase, extending the σS part beyond a certain region resulted in hybrid proteins that were subject to the same regulated turnover as σS itself and yielded low β-galactosidase activities (148, 192). These studies roughly mapped the turnover element somewhere in or downstream of region 2.4 (which is involved in recognition of the −10 promoter element). Consistent with σS and σ70 recognizing the same −10 consensus (19, 47, 81), there is extreme amino acid similarity of these two sigmas up to the end of region 2.4. Just beyond this point, however, the sequences diverge. Reasoning that only σS is unstable and therefore should contain the turnover element, a number of amino acids in this region of σS, which clearly differ from those in σ70, were replaced by the latter ones. This identified K173 as an absolutely crucial amino acid for σS proteolysis. A single point mutation, K173E, eliminates rapid σS proteolysis (20). Single mutations in E174 or V177 also enhance the σS half-life two- and threefold, respectively (20). In conclusion, K173 is a core amino acid of the turnover element. Moreover, K173 is also crucial for promoter recognition in the extended −10 part of a promoter (specifically of a C in position −13) (19), and this part of σS or σ70 is now termed region 2.5 (13, 19).