Abstract

Life, as we know it, is water based. Exposure to hydroxonium and hydroxide ions is constant and ubiquitous, and the evolutionary pressure to respond appropriately to these ions is likely to be intense. Fungi respond to their environments by tailoring their output of activities destined for the cell surface or beyond to the ambient pH. We are beginning to glimpse how they sense ambient pH and transmit this information to the transcription factor, whose roles ensure that a suitable collection of gene products will be made. Although relatively little is known about pH signal transduction itself, its consequences for the cognate transcription factor are much clearer. Intriguingly, homologues of components of this system mediating the regulation of fungal gene expression by ambient pH are to be found in the animal kingdom. The potential applied importance of this regulatory system lies in its key role in fungal pathogenicity of animals and plants and in its control of fungal production of toxins, antibiotics, and secreted enzymes.

HISTORICAL INTRODUCTION TO pH REGULATION

Many microorganisms, particularly if they are able to grow over a wide pH range, tailor gene expression to the pH of their growth environment. Genes whose expression is likely to be influenced by ambient pH include those involved in the provision of secreted enzymes, permeases, and exported metabolites, all of which must function at ambient pH, and probably also those involved in internal pH homeostasis. Observations suggesting that gene regulation can respond appropriately to ambient pH extend back more than half a century for bacteria (49, 50; for reviews, see references 46, 46a, 57, and 65) and at least a quarter of a century for fungi (25, 72, 89, 107, 123).

The groundwork for a systematic investigation of ambient pH regulation of gene expression in fungi was unknowingly laid by Gordon Dorn. Dorn (34, 35) selected a large number of mutations affecting acid and/or alkaline phosphatase in Aspergillus nidulans and found that they identified an unexpectedly large number of genes. He originally proposed that the phosphatases are hetero-oligomeric, a hypothesis that his subsequent biochemical studies failed to confirm. However, by monitoring both secreted acid phosphatase, an enzyme synthesized under acidic growth conditions, and secreted alkaline phosphatase, an enzyme synthesized under alkaline conditions, he contributed both a methodology and experimental material which were to be crucial to the study of pH regulation.

Our involvement in pH regulation dates back to the mid-1960s, when one of us (H.N.A.) was doing a Ph.D. at the University of Cambridge under the supervision of David Cove, who had selected a number of mutations conferring resistance to molybdate toxicity in Aspergillus nidulans in the hope that they would prove useful in the analysis of nitrate reductase and the molybdenum-containing cofactor it shares with other molybdo-enzymes. In the course of mapping these mutations, I used a number of Dorn's mutants. Unexpectedly, many of the mutations selected by Dorn resulted in resistance or hypersensitivity to molybdate toxicity (1, 4), a finding which was to remain enigmatic for the better part of two decades. The next pleiotropic effect emerged when it was found that Dorn's pacCc5 mutation reduced γ-aminobutyrate (GABA) transport (2). An apparently altered electrophoretic mobility (35) led to the mistaken proposal that pacC encodes a secreted acid phosphatase involved in the synthesis, membrane integration, or functioning of certain permeases, notably those for GABA and molybdate (2). The hypothesis was to be discarded, but GABA transport analysis has proved invaluable in investigating pH regulation.

Shortly afterward, Mark Caddick embarked on a Ph.D. His thesis (14) contains suggested likely roles for nearly every gene Dorn had identified (15, 17, 109). Reproducibility of the altered electrophoretic mobility attributed to pacCc5 proved elusive (14), and, from what is now known, any such altered mobility in a pacC mutant is likely to have resulted from an effect on glycosylation of the acid phosphatase (93, 131).

pH REGULATION IN ASPERGILLUS NIDULANS

pH Regulatory Domain

Identified Aspergillus nidulans genes subject to regulation by ambient pH can be classified into three categories: those encoding secreted enzymes, those encoding permeases, and those encoding enzymes involved in synthesis of exported metabolites. pH-regulated genes encoding secreted enzymes include pacA encoding acid phosphatase (15, 17), xlnB encoding a xylanase (75, 98), abfB encoding an α-l-arabinofuranosidase (54), and one or more genes encoding an acid phosphodiesterase(s) (16, 17), all expressed preferentially under acidic growth conditions, as well as palD encoding alkaline phosphatase (15, 17), prtA encoding an alkaline protease (62, 122, 128), and xlnA encoding a xylanase (75, 96, 98), all expressed preferentially under alkaline growth conditions. pH-regulated genes encoding permeases include gabA encoding a GABA transporter having an acidic pH optimum and expressed preferentially at acidic ambient pH (6, 17, 39, 59). Indirect evidence suggests that a molybdate permease might be synthesized preferentially under acidic conditions (4, 17). pH-regulated genes involved in synthesis of exported metabolites include the preferentially alkaline-expressed acvA encoding δ-(l-α-aminoadipyl)-l-cysteinyl-d-valine synthetase and ipnA encoding isopenicillin N-synthase, the first two enzymes of penicillin biosynthesis (40, 42, 112, 121), as well as the preferentially acid-expressed stcU encoding a ketoreductase catalyzing the reduction of versicolorin A and participating in synthesis of the toxin sterigmatocystin, which, in certain other Aspergillus species, is a precursor of aflatoxins (9, 64). Additionally, one or more activities involved in the toxicity of aminoglycosides such as neomycin and kanamycin appears to be under ambient pH control such that toxicity is greatest under alkaline growth conditions (17). The pacC gene encoding the transcription factor mediating pH regulation is itself preferentially expressed at alkaline pH (122).

Formal Genetics of pH Regulation

Mutations affecting pH regulation fall mainly into two categories. The first is that of alkalinity-mimicking mutations which, irrespective of ambient pH, lead to a pattern of gene expression similar to that in the wild type grown under alkaline conditions. These mutations, for example, reduce GABA transport and acid phosphatase, increase alkaline phosphatase levels, and result in molybdate resistance and neomycin hypersensitivity (Table 1). The second category is that of acidity-mimicking mutations which, irrespective of ambient pH, lead to a pattern of gene expression similar to that shown by the wild type grown under acidic conditions and show the opposite phenotype to mutations in the first category (17, 122). For example, they prevent or reduce growth at alkaline pH, reduce alkaline phosphatase levels, increase GABA transport and acid phosphatase levels, and confer neomycin resistance and molybdate hypersensitivity (Table 1). In addition, a small number of mutations have a neutrality-mimicking phenotype irrespective of ambient pH in which the pattern of gene expression approximates that of the wild type grown at pH 6.5 or has a heterogeneous mixture of alkalinity-mimicking and acidity-mimicking characteristics (83).

TABLE 1.

Approximate plate test phenotypes of A. nidulans mutations affecting pH regulationa

| Relevant genotype | Growth at 25°C | Growth at pH 8 | Growthb in the presence of MoO42− | Growthc in the presence of neomycin | Acid phosphatase stainingd | Alkaline phosphatase stainingd | GABA utilizatione in areAr strain |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pacCc | +++ | +++ | ++ | − | − | ++ | − |

| Wild type | +++ | +++ | + | + | + | + | − |

| pacC−f | − | − | − | +++ | +++ | − | ++ |

| pacC+/−, palA−, palB−, palC−, palF−, palH− | +++ | − | − | +++ | +++ | − | ++ |

| palI−, palF+/−, palH+/− | +++ | + | − | +++ | ++ | − | ++ |

Unless otherwise specified, growth is at 37°C on appropriately supplemented minimal medium at pH 6.5.

Concentration range, 20 to 30 mM.

Concentration range, 0.5 to 2 mg/ml.

On medium lacking phosphate.

As the sole nitrogen source. See reference 3.

Growth scores take into account a reduction of growth on all media.

pH regulation is mediated mainly by seven genes, pacC, palA, palB, palC, palF, palH, and palI, where mutations lead to either alkalinity, acidity or, occasionally, neutrality mimicry.

Acidity-, alkalinity- and neutrality-mimicking mutations have been obtained in pacC (17, 33, 39, 83, 95, 122). This phenotypic heterogeneity reflects the more direct involvement of the pacC product (the key transcription factor, see below) in regulation of gene expression by ambient pH. The pacC acronym reflects the loss of acid phosphatase at acidic pH characteristic of the (numerous) alkalinity-mimicking gain-of-function class (34), denoted pacCc (although strictly speaking these mutations are “constitutive” only for expression of alkali-expressed genes and are “superrepressed” for acid-expressed genes irrespective of ambient pH [Fig. 1]). In contrast to pacCc mutations, which are partially dominant to the wild-type allele, mutations in the partial- and complete-loss-of-function class, denoted pacC+/− and pacC−, respectively, are mostly recessive and lead to acidity mimicry. Neutrality-mimicking mutations (which lead to simultaneous expression of both “acidic” and “alkaline” genes) are denoted pacCc/−.

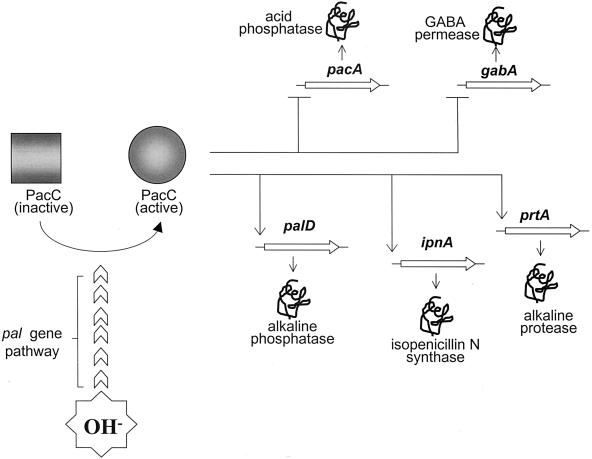

FIG. 1.

Formal genetic model of pH regulation in A. nidulans. PacC is synthesized as an inactive form whose activation requires a signal transduced under alkaline pH conditions by the pal signaling pathway. The active form of PacC is a transcriptional repressor of acid-expressed genes, such as pacA and gabA, and a transcriptional activator of alkaline-expressed genes, such as ipnA, prtA, and palD. Mutations inactivating pacC (pacC− or pacC+/−) or the pal signaling pathway lead to absence of expression of alkaline genes and derepression of acidic genes, which results in acidity mimicry. Gain-of-function pacCc mutations bypassing the pal signaling pathway (i.e., leading to active PacC at any ambient pH) result in permanent activation of alkaline genes and superrepression of acidic genes, which leads to alkalinity mimicry.

In contrast to the above heterogeneity, only acidity-mimicking mutations have been obtained in palA, palB, palC, palF, palH, and palI (3, 17, 95, 122). Mutations in these six pal genes are in all cases recessive and hypostatic to (i.e., phenotypically masked or suppressed by) the vast majority of pacC mutations (3, 17, 95; L. A. Rainbow, J. Tilburn, and H. N. Arst, Jr., unpublished data). Null mutations in pacC and the six pal genes lead to strong acidity mimicry (31, 32, 90, 91, 122; H. J. Bussink, M. A. Peñalva, and H. N. Arst, Jr., unpublished data).

The model shown in Fig. 1 accommodates the formal genetic data: at alkaline ambient pH, but not at acidic ambient pH, the products of the six pal genes transduce a signal able to trigger the conversion of the transcription factor encoded by pacC to an active form able to activate the expression of alkali-expressed genes and to prevent the expression of acid-expressed genes.

PacC Transcription Factor

The derived sequence of PacC contains 678 amino acids (122). An M5I mutation (pacC504) (122) has been used to show that most, possibly all, translation proceeds from methionine codon 5, which would result in a 674-residue protein (83). (Residue numbering, however, continues to be on the basis of 678 residues to avoid confusion between earlier and later publications [83].) The most notable feature of the derived translation product is the presence of three Cys2His2 zinc fingers beginning at residue 78 (Fig. 2A). A number of regions are rich in certain amino acids (95), but the significance of this is unclear with the possible exception of a glycine-plus-proline-rich region beginning at residue 314 (see below) (41, 122). An eye-catching feature is the presence of three perfect copies and one imperfect copy of a 6-residue direct repeat in which the perfect copies contain only acidic and glutamine residues (122). Its significance is unclear but is not likely to be great, since it is not present in isofunctional homologues from organisms as closely related as Aspergillus niger and Penicillium chrysogenum (76, 119).

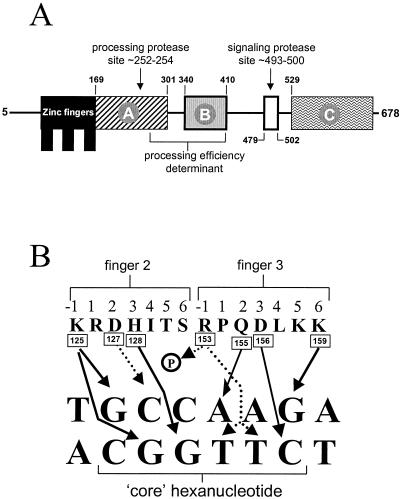

FIG. 2.

Schematic representation of PacC and its DNA binding specificity. (A) Functionally relevant regions in PacC are shown, with limits indicated by residue numbers. Interacting regions A, B, and C are required for maintaining the closed PacC conformation (41). The open box denotes the 24-residue signaling protease box (33). The approximate positions of the signaling protease and the processing protease cleavage sites are indicated by arrows. (B) Prediction of specific contacts between residues in the reading α-helix of PacC zinc fingers 2 and 3 and the PacC target hexanucleotide. Experimental evidence and modeling (43) strongly suggest the contacts indicated by the solid lines. Almost every base in both strands of the target site is predicted to establish specific contacts with PacC zinc finger residues. Dotted arrows indicate possible contacts of Asp127 and of Arg153, whose side chain can be modeled as contacting either the phosphate backbone or the O-4 atoms of both the T4′ and T5′ thymines. Note that finger 1 does not appear to be involved in specific contacts with DNA.

The specificity of the PacC zinc finger DNA binding domain has been thoroughly analyzed using site-directed and classical mutagenesis of both the DNA target and finger residues involved in critical contacts, various footprinting techniques, quantitative binding experiments, and molecular modeling (43, 122). These analyses indicate that finger 1 interacts with finger 2 rather than directly with the DNA and that finger 2 participates in extensive contacts with the 5′ moiety of the binding site while finger 3 binds the 3′ moiety (43). Both partially purified PacC obtained from mycelial extracts and bacterially expressed PacC bind DNA specifically, the core target sequence being 5′-GCCARG with a preference for T at −1 (43, 95, 122). Nearly every base of the core binding sequence appears to be involved in specific contacts (Fig. 2B) (43). A Gln155-to-A4 contact (Fig. 2B) is crucial for binding, which is abolished by either a Gln155Lys substitution or an A4-to-T transversion (43, 95). However, although the sequence specificity for a single PacC binding site is very high, a tandem arrangement of two sites in inverse orientation allows a relaxation of specificity (39). The almost complete conservation of amino acid sequence in the reading (specificity determining) α-helices of fingers 2 and 3 between PacC and its yeast homologues (see below) strongly suggests that these factors will all show the same binding specificity. Indeed, a functional Yl (Yarrowia lipolytica) Rim101p site has been shown to be a direct decameric repeat containing two direct repeats of the above consensus (7).

Activation and Repression Roles of PacC

Detailed studies have been made of the roles of PacC in the promoters of one alkali-expressed gene, ipnA, and one acid-expressed gene, gabA (39, 40).

The bidirectional promoter lying between the divergently transcribed acvA and ipnA genes contains five GCCARG sites (designated ipnA1 through ipnA4B) within the 872 bp separating the coding regions of the two genes (40). The site closest to acvA (ipnA1) has a negligible affinity for a bacterially expressed PacC fusion protein (40). The two sites closest to ipnA are in inverse orientation, separated by 9 bp, and form the double ipnA4AB site starting at −258 relative to the major transcription start point (−699 with respect to the translation start). The ipnA2 and ipnA3 sites are located at −593 and −502 relative to the transcription start point, respectively. Interestingly, although ipnA2 has a fivefold-greater affinity for PacC than does ipnA3 or the double ipnA4AB site, deletion of both ipnA3 and ipnA4AB almost completely abolished the elevation of ipnA expression under alkaline growth conditions as monitored by a fusion reporter gene (40). Deletion of ipnA2 alone reduced expression by nearly half, and triple deletion of ipnA2, ipnA3, and ipnA4AB reduced expression about 20-fold, making the expression level not significantly different from that seen under acidic growth conditions (40). Deletion of ipnA3 reduced expression fivefold (40), and it has also been suggested that ipnA3 is the most important PacC binding site for acvA expression (121). The fact that deletion of PacC binding sites can eliminate the elevation of ipnA expression which occurs under alkaline growth conditions confirms the direct action of PacC in activating the expression of an alkali-expressed gene (Fig. 1).

The gabA promoter contains two inversely oriented, adjacent, PacC binding sites, one a consensus GCCAAG site and the other a near-consensus GCCGAG site (39). These sites overlap the site for the transcription factor IntA/AmdR mediating induction by ω-amino acids, with the consequence that PacC and IntA/AmdR compete for binding (39). Thus, PacC repression of gabA expression is direct and occurs through blocking induction. Exchanging IntA/AmdR binding sites between the gabA and amdS (encoding acetamidase) genes renders gabA expression independent of ambient pH and amdS an acid-expressed gene (39).

Mutational Analysis of pacC

pacC has been thoroughly analyzed genetically, and the molecular characterization of pacC mutations (33, 41, 43, 82, 95, 122) has been crucial for the understanding of PacC activation by proteolysis (see below). Mutational truncations removing between 92 and 412 residues from the C terminus of PacC result in an alkalinity-mimicking (pacCc) phenotype (83, 95, 122; Rainbow et al., unpublished), which revealed that the C-terminal region of PacC contains a negative-acting domain that is inactivated in the presence of alkaline-ambient-pH signaling. Single-residue changes involving residues 259, 266, 340, 573, and 579 also lead to an alkalinity-mimicking pacCc phenotype (41, 83). The relatively large size of the region in which alkalinity-mimicking mutations can occur accounts for the ease with which they can be selected and for the erroneous proposal (17), based on their high frequency, that they constitute the loss-of-function class.

Many more N-terminal truncations result in an acidity-mimicking phenotype (partial loss-of-function pacC+/− mutations), and if the truncation extends into the zinc finger domain, a null pacC− phenotype results (83, 122; C. V. Brown, L. A. Rainbow, J. Tilburn, and H. N. Arst, Jr., unpublished data). The null phenotype of pacC− mutations includes cryosensitivity of growth at the permissive pH of 6.5, a low growth rate at the permissive temperature, poor conidiation, and overproduction of a brown, presumably melanin, pigment (122; Brown et al., unpublished). Single-residue changes within the DNA binding domain result in an acidity-mimicking phenotype whose severity correlates with the relative importance of the residue in question in DNA binding (43; Brown et al., unpublished). Truncations between residues 299 and 315 also result in an acidity-mimicking phenotype, as do a truncation at residue 379 and a deletion of residues 465 through 540 (41, 83, 122; Brown et al., unpublished). Some explanation for this is given in the sections on processing and interactions (see below), but it should also be remembered that anything which reduces the amount of PacC, such as pacC mRNA or PacC instability, will make the phenotype more acidity mimicking to an extent commensurate with the reduction in PacC levels.

Neutrality-mimicking pacCc/− mutations tend to occur in the relatively short region between alkalinity-mimicking and acidity-mimicking truncating mutations (83; Brown et al., unpublished).

Proteolytic Processing of PacC

The analysis of wild-type and mutant forms of PacC in protein extracts prepared from mycelia grown at different ambient pHs provided an explanation for the gain-of-function phenotype of mutations truncating the C-terminal region of PacC. Electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) and Western analysis revealed two different forms of PacC, the 72-kDa translation product and a 27-kDa truncated version (encoded by codons 5 through ∼252 to 254) (83, 95), denoted the processed form. The translation product predominates under acidic growth conditions or in the absence of a functional pal pH signaling pathway, whereas the processed form predominates under alkaline growth conditions or in alkalinity-mimicking pacCc mutants, supporting the conclusion that PacC is proteolytically processed in response to alkaline ambient pH (41, 83, 95). In agreement, the translation product and the processed form show a precursor-to-product relationship in a pal pathway-dependent manner (83). As noted above, the major class of mutant pacCc alleles leading to an alkalinity-mimicking phenotype results from C-terminal truncation of PacC. Mutant proteins truncated at or between residues 407 and 578 are proteolytically processed at any ambient pH, independently of the pal pathway, indicating that a key function of the C-terminal moiety removed by pacCc truncating mutations is prevention of proteolytic processing under acidic ambient pH conditions.

What is the physiological role of PacC processing? The translation product is relatively inert transcriptionally, as shown by the strong acidity-mimicking phenotype resulting from either nonleaky pal− mutations, preventing proteolytic processing (31, 32, 91, 95) and leading to preferential cytosolic localization of PacC (82), or nontruncating pacC+/− mutations (e.g., the pacC+/−20205 deletion and the pacC+/−209 missense mutation [33, 83]), which result in mutants that are phenotypically indistinguishable from null pal mutants. In contrast, a mutant PacC protein truncated after residue 266 (the pacCc50 product) is able both to activate “alkaline” gene and to repress “acidic” gene expression (95). Since the C terminus of this mutant protein is close to that of the processed form(s) (within residues 252 to 254), this finding indicates that processing leads to the activation of the otherwise inactive pacC translation product. In view of the facts that PacC[5-250], PacC[5-265], and PacC[5-273] polypeptides tagged at their C termini (in all three cases close to the processing site) with green fluorescent protein (GFP) are localized in the nucleus in a pal-independent manner (81, 82) and that PacC[5-250] tagged at its N terminus with GFP is also localized in the nucleus in a pH- and pal-independent manner (81, 82), PacC proteolytic activation clearly at least promotes the nuclear localization of a transcriptionally active polypeptide. The model accommodating this finding in references 82 and 95 has been modified to take into account the fact that the proteolytic activation of PacC takes place in two steps (see below and Fig. 4).

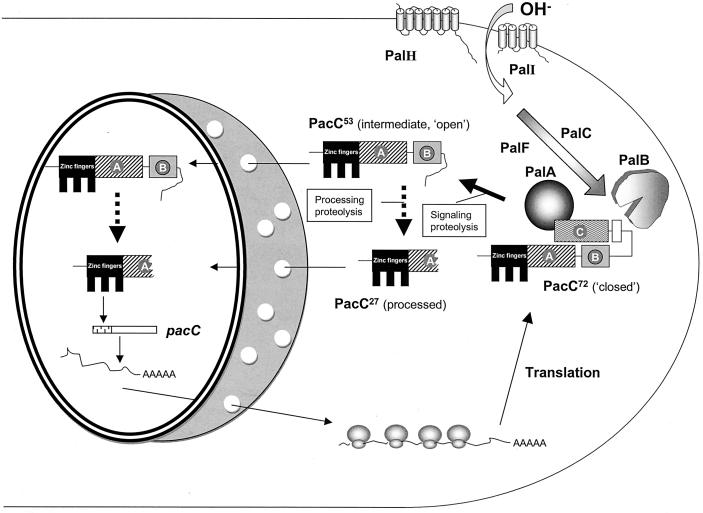

FIG. 4.

Current two-step model of PacC proteolytic activation. Details are described in the text. PacC72, PacC53, and PacC27 refer to the 72-kDa full-length, the 53-kDa intermediate, and the 27-kDa processed PacC forms, respectively. The signaling cleavage step requires alkaline pH signaling through the pal pathway and leads to the intermediate, which is committed to the ambient pH-independent processing cleavage step. The processing protease has not yet been identified, but PalB would appear to be the signaling protease recognizing the signaling protease box (shown as an open box). Commitment to processing results from removal of interacting region C, which is also removed by pacCc-truncating mutations. That the signaling cleavage occurs in the cytosol is supported by the nuclear exclusion of its PacC72 substrate and the preferential nuclear localization of its PacC53 product (82). The processing cleavage might be in the cytosol and/or in the nucleus, as indicated by the dotted lines connecting PacC53 and PacC27. pacC is itself an alkali-expressed gene (122).

Closed and Open Forms of PacC

The products of pacCc alleles are processed at acidic ambient pH, as is the largely nonfunctional but processable pacC+/−230 product (83, 95) (see below), which strongly suggests that the processing protease is not pH (or PacC) regulated. Therefore, the susceptibility of PacC to the processing protease appears to be the pH-regulated, pal signal requiring step.

The existence of two different forms of the translation product was proposed to accommodate both the pH independence of processing and the opposing phenotypes of two mutations which have been crucial for understanding the proteolytic processing cascade (83): pacCc69(L340S) is a missense mutation (33, 83), leading to alkalinity mimicry. PacCL340S is processed irrespective of ambient pH (33, 83), suggesting that its translation product is in an “open” conformation, permanently accessible to the protein protease even in the absence of pal signaling, and that Leu340 is essential for maintaining a protease-inaccessible “closed” conformation, preventing PacC proteolytic activation in the absence of pal signaling (i.e., under inappropriate circumstances). pacC+/−20205 is a strong loss-of-function mutation phenotypically indistinguishable from a pal− mutation (83). The pacC+/−20205 product is largely unprocessed at both acidic and neutral (where pH signaling occurs; note that pacC+/− mutations prevent growth at alkaline pH [Table 1]) pHs (41, 83). This mutant PacC, with residues 465 to 540 deleted, is deficient in pH signal reception and response and appears to be locked in the closed conformation.

That in vitro-synthesized PacCL340S was more susceptible to a proteolysis by a mycelial extract than was the wild-type protein (41) strongly supports the view that the Leu340Ser substitution causes a conformational change in PacC. Moreover, a classically selected mutation corroborates the view that the opposing phenotypes of pacCc69(L340S) and pacC+/−20205 result from opposing effects of the mutational changes on PacC accessibility to the processing protease. pacCc2020507 is an intragenic suppressor of pacC+/−20205 leading to alkalinity mimicry and processing of the doubly mutant PacC at any ambient pH. It results in a Leu340Ser substitution (41), which demonstrates that the processing defect of pacC+/−20205 results from inability to respond to ambient pH by adopting the open conformation.

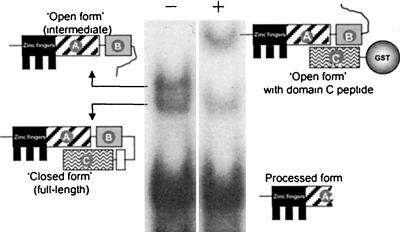

The molecular characterization of pacCc truncating mutations leading to pH-independent processing strongly implicated a C-terminal region of PacC in maintaining the protease-inaccessible conformation. In agreement, one- and two-hybrid, coimmunoprecipitation and affinity column experiments showed that a polypeptide containing residues 529 to 678 was able to interact with upstream regions contained within residues 169 to 410 in a Leu340-dependent manner, demonstrating that this interaction corresponds to that disrupted by L340S (pacCc69) and is therefore physiologically relevant (41). A key finding was that interactions involving PacC polypeptides are strong enough to be detectable by a modified EMSA (41). A truncated PacC form (and therefore open) DNA complex was supershifted by the presence in the reaction mixture of a polypeptide containing PacC residues 529 to 678, expressed, and purified from recombinant bacteria (Fig. 3). The relative ease with which different PacC regions could be monitored in this assay facilitated the identification of three interacting regions in PacC, denoted A, B, and C (Fig. 2A) and contained within residues 169 to 301, 334 to 410, and 529 to 678, respectively (41). Interacting regions A and B include critical determinants for the efficiency of the processing protease (33; E. Díez and M. A. Peñalva, unpublished data), and region A overlaps the processing site, which strongly suggests that access of the processing protease is sterically prevented in the closed conformation (41).

FIG. 3.

Supershift assay. The full-length, intermediate, and processed PacC-DNA complexes can be resolved in an EMSA gel. The open (intermediate) form has its regions A and B available for interaction with a purified glutathione S-transferase (GST) fusion protein (here GST::PacC[410-678]) containing interacting region C, whereas in full-length, closed PacC these regions are not available (see the schematic representations). The remarkably stable interaction of open PacC with the large (possibly dimeric) GST fusion protein results in markedly reduced mobility (i.e., supershift) of the corresponding protein-DNA complex. The presence or absence from the reaction mixture of the GST::PacC[410-678] fusion protein is indicated by + and −, respectively.

In A. nidulans PacC and its most closely related homologues (e.g., in A. niger and P. chrysogenum), regions A and B are separated by a Pro- and Gly-rich linker (119), which is proposed to serve as a hinge enabling opening from the closed conformation in response to alkaline ambient pH signaling (41). The interaction of regions A and B would be held in place by region C, which explains why C-terminal truncating mutations removing this domain result in pH-independent processing and alkalinity mimicry.

Single-residue substitutions disrupting the closed conformation were obtained by classical genetics in each of the interacting domains, bypassing the need for pH signal transduction. These included Leu259Arg (pacCc63) and Leu266Phe (pacCc39) in region A, Leu340Ser (pacCc69) and the phenotypically weaker Leu340Phe (pacCc234) in region B, and Arg573Trp (pacCc2020510), Arg579Gly (pacCc232), and Arg579Thr (pacCc200 pacC20042) in interacting domain C (41, 83)

The supershift assay provided further evidence for disruption of the interactions involving interacting regions A, B, and C by the Leu340Ser substitution. In wild-type PacC obtained using acidic growth conditions, region C, which is involved in intramolecular interactions with upstream regions, could not participate in intermolecular interaction with a purified polypeptide from residues 169 to 410 containing A and B, whereas it could participate in this interaction in the L340S mutant (41). The same situation was found with the L259R mutant, confirming the similarity of consequences of substitutions affecting crucial residues in either A or B (41).

Physiological Relevance of the Open Form

The supershift assay provided a biochemical way of defining the open PacC form as the proportion of unprocessed PacC whose interacting regions A and B are available for interactions with a domain C (residues 529 to 678) polypeptide (41). Mutant proteins lacking all or a significant portion of this domain are in the open conformation, and, if truncation occurs downstream of residue 407 (the downstream limit of a processing efficiency determinant) (83), they are also committed to processing (33).

If the closed-to-open conformational transition is the pH-regulated step, the relative proportion of each form should vary according to ambient pH in a pal-dependent manner. Espeso et al. (41) demonstrated that the relative proportion of open to closed form in unprocessed PacC is twice as great at alkaline as at acidic pH. This response to ambient pH was largely missing in a palA1 mutant strain. Amounts of the open form were much reduced in the palA1 strain and even more so in a pacC+/−20205 strain (41).

Processing Protease Step

The processing protease step leads to the PacC processed form, which appears to be slightly heterogeneous in size. Processing does not remove residues from the N terminus of PacC (83; E. Díez, M. A. Peñalva, and J. Tilburn, unpublished data), enabling high-resolution (∼500-Da discrimination) EMSA gels to be used to determine that the C-terminal residue of the most upstream processed form lies within residues ∼252 to 254 (∼27 kDa) (83). An unexpected feature of the processing proteolysis was revealed by the fact that mutant proteins having deletions of residues 235 through 264 or 235 through 301, which remove the processing protease target site(s), are processed to polypeptides whose size is indistinguishable by EMSA from that of the wild type (83; Díez and Peñalva, unpublished). This strongly suggests that the specificity of the processing protease resides at sequence or structural determinants located upstream of residue 235 and that the protease cuts at peptide bonds remote from these determinants, thereby resembling type 1 endonucleases (83). Identification of this remarkable processing protease has thus far proved elusive. The palB calpain-like product is not the processing protease (32) (see below), and no other Pal protein has sequence signatures characteristic of known proteases. pal− mutations are always hypostatic to pacCc mutations even though the PacC proteins of pacCc strains undergo processing (see above). Thus, the gene(s) encoding the processing protease remains to be identified. It should be noted that the processing protease appears to be conserved in Saccharomyces (83), although it does not appear to recognize the isofunctional PacC homologue Rim101p (135) (see the Saccharomyces discussion below).

In addition to specificity determinants upstream of residue 235, the efficiency of the processing protease is largely dependent on residues 266 to 407 (33, 83; Díez and Peñalva, unpublished). Impaired processing of mutant proteins lacking this efficiency determinant (Fig. 2A), which is dispensable for the signaling protease (see below), revealed the existence of the processing intermediate (33).

Transition from the Closed to the Open Conformation Involves Another Proteolytic Step, the Signaling Proteolysis

High-resolution EMSA (33, 82) discriminates between the open and closed PacC-DNA complexes. PacC in the open complex is not recognized by anti-PacC[529-678] antiserum or, in the case of C-terminally tagged PacC, by antisera against the cognate tag (33), strongly suggesting that open PacC is not the full-length translation product and actually lacks C-terminal residues. Therefore, the closed-to-open transition involves a proteolytic step distinct from the processing step. Two experimental approaches were crucial to demonstrating that this proteolysis, denoted the signaling protease step (33), is the pH-regulated step that is dependent on the pal signaling pathway. First, PacC deletion mutants partially or fully deficient in the processing protease step accumulated a processing intermediate truncated between residues ∼489 and 511 (i.e., lacking the C-terminal interacting region C) at the expense of the translation product and in a pal-dependent manner (33). Second, analysis of PacC in cultures in which the pH was shifted from acidic to alkaline conditions revealed that closed PacC is rapidly converted to open PacC after the pH shift and that this correlates strictly with the detection in Western blots of an intermediate truncated between residues ∼493 and 500. As in deletion mutants, this intermediate accumulated at the expense of the translation product in a pal-dependent manner (33). This intermediate is the precursor of the processed form (truncated at residues ∼252 to 254) (33), as predicted by commitment to processing of similar mutant proteins such as the pacCc14 product (truncated after residue 492) (95).

Díez et al. (33) identified a 24-residue conserved sequence, denoted the signaling protease box, which overlapped the predicted C terminus of the intermediate and whose deletion prevented both the signaling and the processing proteolytic steps, in agreement with a translation-product-to-intermediate-to-processed-form proteolytic cascade (Fig. 4). Two classically selected mutations in which Leu498 located within the signaling protease box was replaced also fully (Leu498Ser) or partially (Leu498Phe) prevented the formation of both the intermediate and the processed form (33), revealing a crucial role for Leu498 in the formation of the intermediate. pacC+/−209, the strongest of the above mutations, is an extreme-acidity-mimicking mutation, phenotypically indistinguishable from null alleles in any of the pal genes except palI (see above) (33). The requirement of the signaling protease box for the formation of the intermediate and processed forms explains why the pacC+/−20205 product is locked in the closed conformation (see above), since the pacC+/−20205 deletion removes this conserved 24-residue sequence (Fig. 2A) (33).

The extreme-acidity-mimicking pacC+/−209 mutation and the molecular nature of the blocked reaction (an irreversible proteolytic cleavage of PacC) strongly suggest that this is the ultimate event in signaling by the pal pathway. The only protease thus far identified in this pathway is the calpain-like PalB protein (see below), implicating it as the likely candidate for the signaling protease (33). In this context, the fact that that calpain, which shows no strong sequence specificity for cleavage, nevertheless shows some preference for Leu in position P2 (21) is very suggestive in view of the critical role shown for Leu498. However, definitive evidence confirming the role of PalB as the signaling protease remains to be provided.

Díez et al. (33) also showed that PacCL340S, in which interactions between regions A, B, and C have been disrupted by the Leu340 substitution (see above), undergoes processing (abnormally) without passing through the intermediate, which in turn provides further support for the conclusion that the key role of the signaling cleavage lies in disrupting the interactions which prevent processing under inappropriate circumstances.

Figure 4 summarizes the current two-step model for the proteolytic activation of PacC (33). The pal-regulated signaling protease cleavage takes place within the signaling protease box, leading to the intermediate which was formerly denoted “open PacC” (41, 83). This intermediate lacks interacting region C and is therefore committed to processing. Readers should note that this two-step processing of PacC can be compared to Rip (regulated intramembrane proteolysis) (10, 11).

Regulation of PacC Nuclear Localization

Ambient-pH-dependent proteolytic activation regulates PacC subcellular localization (82). In the absence of pH signaling, the translation product is largely cytosolic. In contrast, its conversion to the processed form resulting from pH signal reception correlates with almost exclusive nuclear PacC localization. The palA1 mutation, which prevents processing at neutral pH, also prevents this transition from cytosolic to nuclear localization (82). The open PacC polypeptide (i.e., the intermediate truncated after residue ∼500) also appears to be nuclear (82). Therefore, formally, the C-terminal moiety removed by processing prevents the nuclear localization of PacC (82). The mode by which the C-terminal region of PacC prevents its nuclear localization is unknown. Figure 4 incorporates data on the different subcellular distributions of the PacC translation product and the intermediate and processed forms.

PacC contains a putative bipartite nuclear localization signal between residues 252 and 269 (122), which is insufficient to result in nuclear localization of a GFP reporter (82). This sequence might facilitate nuclear localization of the processing intermediate but not of the processed form, since it is removed by the final processing step. Therefore, a nuclear localization signal located within residues 5 through ∼252 to 254 must mediate the pal-independent nuclear localization of the GFP-tagged processed form (82). Using deletion analysis, Mingot et al. (82) showed that within these limits only the zinc finger region (residues 66 through 173) mediates nuclear localization of GFP. The possibility that the 53.8-kDa GFP-tagged processed form is localized in the nucleus following passive diffusion and nuclear retention by DNA binding, rather than by active nuclear localization signal-mediated nuclear import, was discarded for the following reasons. (i) In gel filtration experiments, this GFP-tagged protein elutes as a 101-kDa protein, which would be above the exclusion limit of nuclear pores. (ii) PacC residues 5 to 234 (including the zinc finger region) drive the nuclear localization of Escherichia coli β-galactosidase. (iii) the Gln155Lys substitution involving a residue in the third PacC finger prevents DNA binding (see above) but not nuclear localization. Therefore, the PacC zinc finger region not only is involved in DNA binding but also contains a functional nuclear localization signal (82).

pH Signal Transduction Pathway

All six pal genes of the pH signal transduction pathway have been characterized (3, 31, 32, 77, 90, 91). With the exception of PalB, inspection of the amino acid sequences of their products gives very few clues to molecular functions, strongly suggesting that the pal signaling pathway is mechanistically novel (Table 2).

TABLE 2.

Conservation of the pal signaling pathway

| A. nidulans | S. cerevisiae | Function | Mammals |

|---|---|---|---|

| PalA | Rim20p | Interacts with Rim101p/PacC | Alix/AIP1 (ALG2-interacting protein) |

| PalB | Rim13p | Calpain-like cysteine protease | CAPN7 calpain |

| PalC | None | Unknown | |

| PalF | Rim8p | Unknown | |

| PalH | Rim21p | 7 TM membrane protein | GPCRs ? |

| PalI | Rim9p | 4 TM membrane protein |

Two of the conceptually translated proteins contain putative transmembrane (TM) domains. PalI, with 549 residues, contains four putative TM domains within the N-terminal one-third of the protein (31). The C-terminal two-thirds of the protein is hydrophilic. The Gly47Asp substitution in the predicted acidic loop between transmembrane segments 1 and 2, in a region highly conserved with the Saccharomyces isofunctional homologue, abolishes PalI function (31). It has been suggested that PalI might be a membrane sensor for ambient pH and that this loop, predicted to be periplasmic (i.e., between the plasma membrane and cell wall), might play an important role (31). The null phenotype for palI mutations is less extreme than the null phenotype for the other five pal genes of the pH signaling pathway (3, 31, 32, 90, 91, 122), indicating that some signal can be transduced in the absence of PalI. Therefore, either PalI is not the only pH sensor or it functions in sensing ambient pH in cooperation with other proteins with which its participation is not essential.

A second Pal protein shares with PalI a predicted membrane localization. The derived PalH sequence contains 760 residues with seven putative TM domains in the N-terminal moiety followed by a hydrophilic C-terminal moiety of just over 400 residues (31). As in seven TM plasma membrane receptors, this long, hydrophilic C-terminal moiety is predicted to be cytosolic. Interestingly, it is not absolutely essential for pH signal transduction, since palH frameshift mutations truncating the normal sequence after residues 377 and 598 have a leaky, partial-loss-of-function phenotype similar to that of a null palI mutation (91). Double mutants carrying a leaky palH mutation and a palI mutation have a phenotype indistinguishable from those of null mutations in palA, palB, palC, palF, or palH, indicating additivity (91). The possibility that PalH is a seven-TM-domain plasma membrane receptor seems rather attractive in view of the possible involvement of endocytosis in pH sensing, to be described in the Yarrowia and Saccharomyces sections (see below).

Conceptual translation of the palB sequence yielded an 847-residue polypeptide having convincing similarity to the catalytic domain in the large subunit of calpains (Ca2+-dependent cysteine proteases) (32). Prototypical mammalian m-calpain consists of large and small subunits, both containing calmodulin-like penta-EF-hand (5-EF-hand) motifs which account for Ca2+ binding and dependence (for reviews, see references 113 and 114). PalB, containing the calpain catalytic triad consisting of Cys (providing the active site thiol), His, and Asn residues (32), is an atypical calpain in that it lacks the large calpain subunit 5-EF-hand domain (32). Extrapolation from work with Saccharomyces cerevisiae (see below) indicates that the presumably catalytic Cys residue, completely conserved among PalB homologues, is essential for PalB function (48).

PalB cannot be responsible for the final proteolytic processing of PacC because a palB allele with a null phenotype fails to prevent pH-independent processing of a mutant PacC lacking 214 C-terminal residues (i.e., lacking interacting region C) to yield a processed form indistinguishable from that of the wild type (32). PalB is therefore a likely candidate for the signaling protease removing PacC interacting region C, converting the PacC translation product into the processing-committed intermediate (33). This would imply that the highly conserved signaling protease box (Fig. 2A) is likely to be the PalB recognition and cleavage site (33).

Using amino acid sequence alignments, Sorimachi et al. (113) identified in fungal PalB homologues a highly conserved region located downstream of the putative PalB catalytic domain, which they designated PHB (for “PalB homology Domain”). This region is diagnostic of a subfamily of calpains which includes metazoan homologues, such as Caenorhabditis elegans CE01070, another atypical calpain lacking the 5-EF-hand domain (113, 114). This raises the intriguing possibility that homologues of fungal ambient pH transducers are conserved in metazoans. Indeed, Futai et al. (47) reported the characterization of a human gene, CAPN7, encoding PalBH/Capn7, a human homologue of PalB of unknown function, which shows preferential nuclear localization. This finding underscores the utility of fungal pH signal transduction genes to reveal unexpected gene features in metazoans.

The 798-residue derived PalA sequence provides few clues to its molecular role (90). The presence of several SH3 domain binding motifs and a proline-rich region (90) possibly hint at protein-protein interactions. Xu and Mitchell (135) have shown that the S. cerevisiae PalA homologue interacts with the S. cerevisiae PacC homologue and suggested that such an interaction might be important for the action of the S. cerevisiae PalB homologue (see below). They have shown that the interaction is conserved in Candida albicans. It is also conserved in A. nidulans (O. Vincent and M. A. Peñalva, unpublished data), lending further support to the notion of its generality. The possible relationship of PalA and its fungal homologues with endocytosis is described in the Saccharomyces and Yarrowia sections (see below).

As in the case of PalB, homologues of PalA are present in the animal kingdom, and their molecular characterization strongly suggests that a PalA-like domain is involved in signal transduction pathways in eukaryotes from fungi to mammals. Murine Alix/AIP1 is a PalA homologue which interacts with ALG-2, a protein required for apoptosis triggered by a number of stimuli and a member of the calpain small-subunit subfamily of calcium binding proteins (66, 74, 84, 130). Overexpression of a truncated form of Alix/AIP1 lacking the N-terminal moiety can protect against cell death (130). Overexpression of the human PalA and Alix/AIP1 homologue HP95 inhibits the growth of confluent HeLa cells through G1 arrest (133a). Another PalA homologue is the rat protein p164PTP-TD14, which can inhibit Ha-ras-mediated transformation (20). The C-terminal moiety of p164PTP-TD14 contains a putative protein tyrosine phosphatase that is apparently required for inhibition of Ha-ras-mediated transformation, whereas the N-terminal moiety contains the region of similarity to PalA (20). Other PalA homologues are Xp95, suggested to be an element in a tyrosine kinase signaling pathway involved in progesterone-induced Xenopus oocyte maturation (23), and YNK1, a Caenorhabditis elegans protein of unknown function (24).

The 775- and 507-residue derived PalF and PalC sequences (77, 91), respectively, provide no clues to their functions. A leaky, partial-loss-of-function palF mutation probably gives no information about a single residue or region since it is a frameshift which would exchange the C-terminal 6 residues of PalF, conserved in closer but not more distant homologues, for a highly hydrophobic 56-residue peptide which presumably adversely affects PalF function, stability, solubility, or subcellular localization (H. J. Bussink and H. N. Arst, Jr., unpublished data). This partial-loss-of-function palF mutation is additive in phenotypes with palI mutations and partial-loss-of-function palH mutations, with the double mutants having the stringent null phenotype of palA, palB, palC, palF, and palH mutants (91). The most interesting point that can be made at present about palC is the absence of an identifiable homologue in the S. cerevisiae genome (91), although one is present in Neurospora crassa. The distribution of palC homologues within the fungal kingdom is therefore likely to be of interest. The (extremely limited) current evidence suggests that palC might be present only in filamentous fungi (see below).

Loss-of-function mutations in any of the six pal genes prevent PacC processing (31, 32, 82, 83, 91, 95) because they prevent the formation of the intermediate, the processing protease substrate (33). This feature is less extreme in palI and leaky palF and palH mutants (31, 91). (Leaky mutations in palA, palB, and palC have yet to be obtained.) However, additivity of mutations causing less extreme phenotypes can be seen in EMSA, as can the epistasis of a nonleaky, stringent pal mutation to a palI mutation (31, 91). Alkalinity-mimicking pacCc mutations are epistatic to acidity-mimicking pal mutations, and this epistasis is seen both when monitoring in vivo characteristics (3, 17) and when using EMSA or Western blot analysis to determine the amount and extent of processing of PacC (95).

Presence of the pH Regulatory System Homologues in Other Fungi

As noted in several sections of this review, homologues of A. nidulans pacC have been identified in a number of filamentous ascomycetes, including A. niger (76), Penicillium chrysogenum (119), Acremonium chrysogenum (110), Sclerotinia sclerotiorum (106), and Aspergillus oryzae (M. Sano and M. Machida, GenBank accession no. AB035899). Therefore, it will come as no surprise to readers that other filamentous ascomycetes such as Aspergillus fumigatus (The Institute for Genomic Research [http://www.tigr.org]) and Neurospora crassa (Whitehead Institute/MIT Center for Research [http://www-genome.wi.mit.edu]) have homologues of all the identified genes involved in pH regulation in A. nidulans, including palC. As described in detail in the following sections, the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae and two dimorphic yeasts, Candida albicans and Yarrowia lipolytica, also have homologues of the pH regulatory system genes, with the sole exception of palC. Therefore, the pH regulatory system appears to be universally present in all major groups of ascomycetes: hemiascomycetes, plectomycetes, and pyrenomycetes.

pH REGULATION IN SACCHAROMYCES CEREVISIAE

Molecular Characterization of the RIM Regulatory System

RIM101, formerly RIM1 (rim stands for “regulator of IME2” [see below]), encodes the founding member of the RIM101p/PacC group of transcription factors. RIM101p is a positive regulator of meiosis in budding yeast, through its stimulation of transcription of IME1, a gene encoding a key positive-acting transcription factor which activates a number of meiotic genes, including the kinase-encoding gene IME2 (117, 118). Nonallelic, recessive rim101, rim8, rim9, and rim13 mutations result in a similar phenotype, characterized by reduced expression of ime1::HIS3 and ime2::lacZ gene fusions, cryosensitive growth, and smooth colony morphology (117, 118). As noted above (Table 2) and below, RIM8, RIM9, and RIM13 are the budding yeast homologues of A. nidulans palF, palI, and palB, respectively.

RIM101 was cloned as restoring ime2::lacZ expression in a rim101-1 mutant, taking advantage of its close linkage to RIM4, a gene in which inactivating mutations completely prevent sporulation. This facilitated the isolation by complementation of plasmids covering the RIM101-RIM4 genomic region (118). A rim101Δ mutant was phenotypically indistinguishable from classical rim101, rim8, rim9, and rim13 mutants, in agreement with the conclusion that recessive rim101 classical mutations represent the loss-of-function class. Rim101p is a 628-residue polypeptide (118) (note that the sequence reported in GenBank P33400 by the yeast-sequencing group contains only 625 residues) having three zinc fingers essential for function (118). Despite the similar sizes of PacC and Rim101p, significant amino acid identity is almost completely restricted to the zinc finger region.

In addition to the above phenotypic features, rim101, rim8, rim9, rim13, and rim20 mutations prevent haploid invasive growth (71, 135). This invasive growth resembles pseudofilamentation in yeast diploids and is defined as a combination of filament formation (which implies a switch from axial to polar budding mode) and penetration of agar underneath colonies growing on rich medium (105). Like diploid pseudohyphal growth, invasive growth requires the mitogen-activated protein kinase cascade components Ste20p, Ste11p, Ste7p, and Ste12p involved in the mating pheromone response pathway. It can also be induced independently of the mating pheromone pathway, for example through the Tpk2p cyclic AMP-dependent-protein kinase A pathway (for reviews of Saccharomyces pseudohyphal growth, see references 51 and 70). The functional interaction between the RIM pathway and the last two pathways promoting filamentation remains to be addressed. The fact that the RIM pathway is important for the transition from the yeast to the hyphal mode of growth in the pathogenic yeast Candida albicans is addressed below. Readers should note that Cph1p, the C. albicans Ste12p homologue, also plays a role in filamentation (73).

Rim101p Is Activated by Proteolytic Processing, Removing a C-Terminal Region

In common with PacC, Rim101p undergoes proteolytic processing activation which, in this case, removes approximately 100 residues from the C terminus of the protein (71, 135). The relative levels of the Rim101p translation product and the processed form depend on growth medium composition. As with PacC, media containing high glucose levels, whose catabolism leads to external acidification, promote accumulation of the translation product, whereas the processed form largely predominates on alkalinization (to pH 8.0) of the growth medium or in the presence of acetate as a carbon source (71), which leads to a final culture pH close to neutrality, where pH signaling also takes place.

The rim9, rim8, rim13, and rim20 loss-of-function mutations prevent the proteolytic processing activation of Rim101p (68, 71, 135). In agreement with the activating role of Rim101p processing, mutations truncating the protein after residue 485, 531, or 539, which would be formally equivalent to pacCc gain-of-function mutations truncating the C-terminal region of PacC, suppress a rim9 mutation (71). In contrast, more upstream truncating mutations do not (71). This would suggest that essential Rim101p regions where truncating mutations would be equivalent to the partial loss-of-function pacC+/− class lie upstream of residue 485. However, this conclusion should be reexamined using site-directed mutagenesis to introduce stop codons as appropriate, rather than using 3′ nested deletions, which might lead to transcript instability, complicating phenotype interpretation (examples are described below in the Yarrowia section). In summary, a C-terminal region in Rim101p downstream of residue 531 behaves as a pal (RIM) signaling pathway-dependent negative-acting region. In agreement, an epitope-tagged protein truncated after residue 531 was shown to suppress rim8, rim9, and rim13 mutations by restoring ime1::HIS3 and ime2::lacZ expression and invasiveness and overcoming the cryosensitivity phenotype associated with these mutations (71). In contrast a protein truncated after residue 620, which lacks the eight C-terminal residues, does not suppress a rim9 mutation, indicating that the negative-acting, RIM-dependent region involves more than this C-terminal tip of the protein (assuming that the mutation has not affected mRNA stability).

One-Step Processing

A difference between Rim101p and PacC is that whereas Rim101p proteolytic activation requires one RIM pathway-dependent proteolytic step (71, 135), PacC activation occurs in two sequential steps, the first of which (the signaling proteolysis) is pH regulated through the pal pathway and the second of which (the processing proteolysis) appears to be pH independent (33) (see above). The position of the single proteolysis at Rim101p was estimated at ∼100 residues from C-terminal residue 628 (71, 135). The signaling protease cleavage site in PacC lies between residues ∼493 and 500, ∼180 residues from the C-terminal residue 678 and markedly downstream of the processing proteolysis site(s) at residues ∼252 to 254.

The single rim pathway-dependent Rim101p cleavage would be equivalent to the signaling cleavage in the proximity of the C terminus of PacC (33, 135). A plausible candidate enzyme for this pal (RIM) pathway-dependent proteolysis is PalB/Rim13p (33, 135), although this reaction has not yet been demonstrated directly. From an evolutionary point of view, it remains to be established whether Rim101p has lost susceptibility to the processing protease or PacC has gained this susceptibility.

Despite the apparent lack of processing-protease susceptibility in Rim101p, the PacC processing protease appears to be conserved in Saccharomyces, since PacC[5-492], a mutant protein approximating the PacC intermediate, is processed in yeast (83). In contrast, the yeast RIM pathway does not appear to recognize PacC, since processing fails to occur with the full-length wild-type protein (83).

Rim101p and the pH Response

An important question is whether the RIM pathway in yeast responds to ambient pH and/or has diverged from the Aspergillus pal pathway to respond to a different signal necessary for efficient sporulation in the a/α diploid cells and invasiveness in haploids. Several lines of evidence strongly suggest that the RIM pathway responds to ambient pH. First, as noted above, Rim101p processing is favored by neutral to alkaline ambient pH conditions and diminishes with acidification of the ambient pH. This would be consistent with inactivation of the pal (RIM) signaling pathway, which completely prevents processing, mimicking extremely acidic pHs. It should be noted that in Aspergillus, mimicry of acidic pH conditions achieved by mutational inactivation of the pal pathway is more extreme that that usually achieved by chemically manipulating the growth medium pH, particularly when the pH is modified by microbial growth. Therefore, the inability to prevent fully Rim101p processing by lowering the ambient pH might simply reflect an inability to block pH signaling at the acidic pHs in standard use. Second, a previously unmentioned phenotype of rim101Δ, rim20Δ (68, 135), and rim13Δ (48) mutants is that of impaired growth at alkaline pH, which strongly suggests that the RIM pathway is required for adaptation to alkaline pH. Third, macroarray transcriptional analysis (see below) revealed that transcription of a subset of genes is elevated by alkaline ambient pH in a Rim101p-dependent manner (68).

Domain of Action of the pH Response

Lamb et al. (68) investigated the genes whose transcription was activated by alkaline pH (8.0) relative to acidic pH (4.0) using macroarray filters containing the yeast open reading frames (ORFs). They identified 71 genes whose transcripts were at least 2.1-fold more abundant in pH 8.0 cells than in pH 4.0 cells. These genes included the Na+-ATPase structural gene ENA1, whose transcription was previously known to be stimulated by both high salt and alkaline stress and which was therefore a positive control. This screen identified, among others, several genes involved either in phosphate or in iron or copper starvation. Comparative Northern and reporter analyses of the relatively high expression of a selection of these “alkaline” genes in rim101Δ and RIM101 cells was used to subdivide them into three different classes, depending on whether their relatively high levels in pH 8.0 medium were (i) strictly dependent on RIM101, (ii) partially dependent on RIM101, or (iii) independent of RIM101 (68).

Class i genes include ARN4 (whose product is involved in iron uptake) and three genes of unknown function. That these genes require the positive action of Rim101p for preferential expression at alkaline pH agrees with the fact that their response to alkaline pH is prevented by a rim13Δ allele (68), since an intact RIM (pal) pathway is required for the proteolytic activation of Rim101p. As noted above and below, Rim13p is the homologue of PalB, the cysteine protease presumed to remove the processing-preventing interacting domain C in PacC (33). The requirement for Rim13p is bypassed at alkaline pH by the RIM101-531-HA2 allele (68), which is consistent with the notion that one role of Rim13p involves activation of Rim101p through C-terminal proteolysis of the latter. At pH 4.0, however, transcription of some of the RIM101-dependent genes was not increased in the RIM101-531 mutant. Although this result should be treated with some caution (as noted above, this truncating mutation is a genomic deletion which might cause instability of the incomplete transcript), it might suggest that such genes require, in addition to wide domain regulation provided by active Rim101p, specific induction conditions not provided by the acidic growth medium (a possible example with the Y. lipolytica AXP1 gene is discussed below).

The fact that class ii genes are partially and class iii genes are fully independent of Rim101p demonstrates that in yeast not all the alkaline response is mediated by this PacC homologue (68). Rim101p-independent class iii genes include PHO84 (encoding a high-affinity phosphate/H+ symporter) and, paradoxically, PHO11/12 (encoding phosphate-repressible acid phosphatases). In an independent study, Causton et al. (22) also identified PHO89 (encoding a phosphate/Na+ symporter) as a gene whose expression is stimulated by alkaline pH (but the question of Rim101p control was not addressed). All four PHO genes listed above are regulated by Pho4p in response to phosphate starvation (94). There is therefore another possible explanation for their apparent classification as alkali-expressed genes, an explanation which might resolve the paradox that genes such as PHO11, PHO12, and possibly PHO84, whose functions would lead to a prediction of preferential expression under acidic conditions, apparently show preferential alkaline expression. Phosphate-limiting growth conditions were not used in monitoring the expression of these genes (68), but phosphate repression might have been stronger in acidic than in alkaline medium: accumulation of vacuolar polyphosphate is stimulated by acidic growth conditions and dependent on vacuolar acidification mediated by the vacuolar membrane H+-ATPase (79, 134). Under alkaline growth conditions (leading to vacuole alkalinization through uptake of endocytotic fluid), the predicted decrease in polyphosphate levels might trigger phosphate starvation signaling.

Little is known concerning yeast acidic gene expression. One of the above transcriptional profiling studies (22) identified three genes, PDR12, ZMS1, and TRK2, encoding a putative ATP-dependent exporter of carboxylate anions, a zinc finger protein, and a potassium transporter, respectively. Of note, the GABA permease-encoding gene UGA4 is, like its A. nidulans gabA orthologue, an acid-expressed gene (86). Also like gabA, UGA4 is subject to complex regulation. For example, UGA4 is repressed by the Dal80p/Uga43p GATA factor, whose transcription is also preferential under certain acidic conditions (86). In none of these cases has it been investigated whether their preferential acid expression is Rim101p dependent (i.e., involving Rim101p repression at alkaline pH), although in the case of UGA4 a consensus PacC/Rim101p binding site is found 237 bp upstream of its coding region (86). UGA4 is probably a good example of a case where profiling studies have failed to detect pH regulation because the inducer (GABA) was absent from the growth media (although some inducer is possibly available intracellularly from intermediary metabolism).

Molecular Characterization of Components of the RIM (pal) Signaling Pathway

In addition to RIM101, the S. cerevisiae genome contains homologues for every pal gene except palC (Table 2) (48, 56, 68, 90, 91, 124, 135).

Two potential PalA homologues, Bro1p and Rim20p, are found in the yeast genome (90), but only the latter belongs to the RIM pathway (135). Two-hybrid and coimmunoprecipitation analyses revealed that Rim20p is able to bind Rim101p, whose residues 547 to 678 suffice for reasonably strong interaction with Rim20p, although a second, nonoverlapping region (residues 297 to 546) mediates a weak interaction (135). PalA also interacts with PacC (Vincent and Peñalva, unpublished). Genome-wide two-hybrid analysis (60) revealed that Rim20p and Rim13p interact with Snf7p/Vps32p, the product of a class E gene involved in vacuolar biogenesis. While the possible relationship of endocytosis with pH signaling is described in the Yarrowia section (see below), this ménage à trois prompted Xu and Mitchell (135) to hypothesize, in view of the ability of Rim20p to bind a C-terminal region of Rim101p, that Snf7p might act as an adapter through which Rim20p/PalA would recruit Rim13p/PalB to its putative target in the C-terminal region of Rim101p/PacC (135). While this model agrees with available evidence, it has not yet been established whether the Rim20p interaction with Rim101p requires another yeast protein.

Another important feature of the RIM pathway genes concerns RIM9, the palI homologue. As described above, palIΔ mutants are exceptional in that they grow to some extent on alkaline pH plates. Both Rim9p (71) and PalI (31) contain four predicted transmembrane domains within a region of high amino acid sequence conservation, but they are markedly different in size (Rim9p, 239 residues; PalI, 549 residues; the revised sequence is given in the addendum in reference 31), which is accounted for by the presence in PalI of a ∼370-residue hydrophilic, putatively cytosolic tail which is absent from Rim9p (31). PalI and Rim9p have been suggested to be membrane sensors (31). It will be interesting to see if the differences in the C termini of the two proteins affect their efficiencies or mode of action.

RIM13 (117), the palB homologue (Table 2), was also identified independently and denoted CPL1 because it encodes a calpain-like protein containing the diagnostic Pal homology domain (114) (see above) and the essential (as determined by site-directed mutagenesis) Cys128 residue, which almost certainly provides the catalytic thiol (48). PalH homologue Rim21p was identified by Tréton et al. (124), who also corrected a sequencing error in the yeast genome sequence, leading to the identification of RIM8/palF, which had been previously identified genetically (117).

pH REGULATION IN CANDIDA ALBICANS

Dimorphism and Pathogenesis

Candida spp. are the fourth-leading causes of nosocomial infection worldwide (18). C. albicans, the most prevalent fungal pathogen of humans, is a dimorphic fungus which undergoes reversible morphological transitions between unicellular yeast-like and hyphal and pseudohyphal growth forms in response to environmental signals, of which those involving ambient pH and temperature changes have been best characterized. Under optimal (37°C) temperature conditions, filamentation is favored by ambient pHs close to neutrality and is considerably reduced at pHs lower than 6. In contrast, the yeast form predominates almost exclusively at pH 4 (13). The PacC (CaRIM101/PPR2 in this organism) pH regulatory system is conserved in Candida spp. and plays a major role in controlling the pH-dependent dimorphic transition. The ability of C. albicans to undergo the dimorphic transition and to respond to diverse environments is thought to be essential for pathogenesis, and, at least in mouse models of systemic infection, mutants impaired in filamentation are largely avirulent (73). Therefore, the mechanisms by which pH regulation controls Candida dimorphism and adaptation to different ambient pH niches within the infected host have received considerable attention. Readers interested in Candida virulence factors and dimorphism can consult recent excellent reviews (8, 8a, 38, 72a, 85). A recently published thorough review of fungal development and virulence (70) is strongly recommended to complement this account of pH regulation.

Characterization of the pH-Dependent Morphological Transition

The molecular characterization of the pH-regulated transition in Candida was pioneered by Fonzi's group, who used differential screening techniques to isolate PHR1, a prototypical alkali-expressed gene encoding a 548-residue membrane-anchored glycosylphosphatidylinositol cell surface protein whose expression is prevented by acidic pH. Phr1p and its Phr2p homologue (see below) are 1,3-β-glucanosyltransferases involved in fungal cell wall synthesis (44, 87). At alkaline pH (where PHR1 is expressed and the filamentous mode of growth predominates), a homozygous phr1Δ mutant showed morphological abnormalities resulting from its inability to grow apically (108). Since this mutant grew normally under acidic pH conditions (where the yeast mode of growth predominates), the existence of a PHR1 isofunctional homologue active at acidic pH was predicted and eventually confirmed (88). This gene was designated PHR2 (88). PHR2 is a prototypical acid-expressed gene showing a pattern of expression inverse to that of PHR1. A phr2Δ mutant showed morphological abnormalities and was unable to grow at acidic pH but grew normally under filamentous growth-promoting alkaline pH conditions (88). Therefore, PHR1 and PHR2 encode isofunctional, mutually interchangeable proteins having a key role in the adaptation of Candida to alkaline and acidic growth conditions, respectively.

C. albicans is able to cause infections in a broad range of host niches which show significant differences in ambient pH. For example, the mouse systemic pH is ∼7.3 whereas the pH in the rat vagina is ∼4.5. This suggested that the ability of Candida to react appropriately to (among other environmental variables) rather different pH environments is crucial for its pathogenicity. Null phr1Δ and phr2Δ strains provided the first evidence for this proposal. A phr1Δ mutant is avirulent in a systemic mouse model of candidiasis (29, 53), whereas a phr2Δ mutant is virulent. In contrast, the phr2Δ mutant is strongly attenuated in virulence in a rat vaginitis model whereas the alkali-expressed PHR1 gene is dispensable for infection of the vaginal niche (29). Therefore, the involvement of pH regulation in infection shown by this work is buttressed by the fact that the virulent phenotype parallels the in vitro pH dependence of the mutant strains (29).

Characterization of the Genes Involved in pH Regulation

The analysis of pH regulation in A. nidulans and its conservation in S. cerevisiae strongly suggested that the reverse modes of expression of PHR1 and PHR2 reflect their regulation by a C. albicans pH regulatory system involving homologues of pacC and the pal genes. The Fonzi (104) and Mitchell (28) groups identified the C. albicans pacC homologue, designated CaRIM101/PRR2. We will use here the RIM101 designation (preceded by Ca, when needed, to indicate C. albicans), in agreement with the use of S. cerevisiae gene nomenclature to designate C. albicans homologues, rather than the PRR2 (for “pH Response Regulator”) designation (104). CaRIM101 encodes a 661-residue polypeptide (note that the ORF reported in reference 28 is missing the N-terminal 58 codons of the complete ORF [104]). PacC, CaRim101p, and ScRim101p have extensive amino acid sequence identity in their tridactyl zinc finger regions but otherwise diverge substantially.

Northern analysis of PHR1 and PRA1 (another alkali-expressed gene) (111) in a Carim101Δ strain confirmed that under alkaline growth conditions, PHR1 and PRA1 are subject to the positive action of CaRim101p whereas PHR2 is repressed by this PacC homologue (28, 104). Neither PHR2 repression nor PHR1 (and PRA1) activation takes place under acidic pH conditions. Therefore, CaRim101p, like PacC (122), is required for repression of acid-expressed genes and for activation of alkali-expressed genes. Additionally, like pacC, CaRIM101 behaves as an alkali-expressed gene subject to its own positive control (28, 104).

The characterization of two C. albicans pal genes, CaRIM8/PPR1 (the palF homologue) and CaRIM20 (the palA homologue), has been reported (28, 99). Like Carim101Δ mutations, homozygous Carim8Δ (28, 99) and Carim20Δ mutations (28) lead to acidity mimicry, as shown by elevated PHR2 expression and absence of PHR1 expression at both pH 4.0 and pH 7.5, i.e., in a pH-independent manner. This is in complete agreement with the A. nidulans model in Fig. 1 and demonstrates that a pH signaling pathway isofunctional to the pal pathway operates in C. albicans. Indeed, putative palB, palH, and palI (but not palC) homologues are present in the C. albicans genome (http://genolist.pasteur.fr/CandidaDB/). CaRIM8 appears to be an acid-expressed gene (99), although it remains to be determined whether it is under the negative action of CaRIM101.

Involvement of pH Regulatory Genes in Filamentation and Virulence

Since the absence of CaRIM101 function leads to acidity mimicry, it would be expected that filamentous growth, which is favored by alkaline growth conditions, should be impaired in a Carim101Δ strain. In agreement, a Carim101 allele compromised the ability of cells to filament on spider medium (133). The Carim101Δ allele constructed by Ramón et al. (104) truncates Rim101p upstream of the DNA binding domain and almost certainly represents a null allele. A homozygous Carim101Δ strain was completely deficient in filamentation on both agar-solidified pH 7.5 199 medium and 10% serum medium and was largely defective on spider medium (104). In liquid 199 medium adjusted to pH 7.5, homozygous Carim101 and Carim101Δ strains were unable to filament. However, this morphogenetic defect was not observed on incubation in serum, which promotes filamentation (133). All the above data show that although CaRIM101 plays a major role in filamentation, it is not essential to filamentation under all growth conditions.

In agreement with the model in Fig. 1, the acidity-mimicking Carim20Δ and Carim8Δ mutations in homozygosis also prevent filamentation on several (but not on all) growth media (28, 99, 133). Forced expression of PHR1 did not restore the filamentation defect of a Carim8Δ mutant, indicating that other CaRIM101-dependent, alkali-expressed genes are also required for hyphal development (and/or that expression of a CaRIM101-dependent acid-expressed gene[s] is preventing filamentation) (99).

Since acidity-mimicking Carim101, Carim8 or Carim20 homozygotes are impaired in filamentation and deficient in the pH response, it was predicted that these strains should also be largely avirulent. That the CaRIM101 pathway is required for pathogenesis in vivo was confirmed in a mouse model of systemic candidiasis, where these mutants showed significant reductions in virulence and development of kidney pathology compared to the wild type and were less damaging to endothelial cells, a process thought to precede the invasion of underlying tissues (27). A dominant gain-of-function truncating mutation in CaRIM101 resembling pacCc alkalinity-mimicking mutations (28) rescued all virulence defects resulting from the Carim8 homozygous mutation and was thus shown to be epistatic in the mouse model to a mutation inactivating the pal pathway (27). This establishes that the only function of CaRim8p in infection takes place through the CaRIM101-dependent regulation of genes involved in pathogenesis.

Alkalinity-Mimicking Mutations Truncating CaRim101p

CaRIM101-405 is a constructed alkalinity-mimicking allele (28) truncating the protein (and the mRNA) after Asn462. This allele is epistatic to Carim8 and Carim20 mutations with respect to filamentation defects, but the complete epistasis seen under alkaline conditions is only partial under acidic conditions, which indicates that double-mutant strains are still to some extent pH dependent for filamentation. It is difficult to judge the significance of this finding, since it has not yet been established whether CaRim101p, like its A. nidulans and S. cerevisiae homologues, is activated by proteolytic processing and, if so, what is the approximate C-terminal residue of the putative processed form. Genetic evidence (outlined below), however, strongly suggests that CaRim101p is activated by a processing reaction removing a negative-acting C-terminal domain. Moreover, as seen with certain YlRIM101 alleles (see below), mutational truncation of the mRNA might lead to mRNA instability, possibly obscuring the mutant protein phenotype.

A genetic approach to isolating dominant, alkalinity-mimicking mutations in CaRIM101 has also been used (37). Homozygous phr2Δ strains do not grow at acidic pH. Suppressors of this conditional growth defect result from dominant CaRIM101 mutations promoting pH-independent expression of PHR1, which compensates for the loss of PHR2 (37). In heterozygosis, these mutations also confer the ability to filament at acidic pH (37). CaRIM101-1426 (Gln476stop) removes 186 residues from the C terminus of CaRim101p, whereas CaRIM101-1751 (Ser584stop) removes 78 residues (37). These dominant alleles result in the ability to filament at acidic pH, pH-independent expression of PHR1, and no expression of PHR2 at any ambient pH.