Abstract

Background

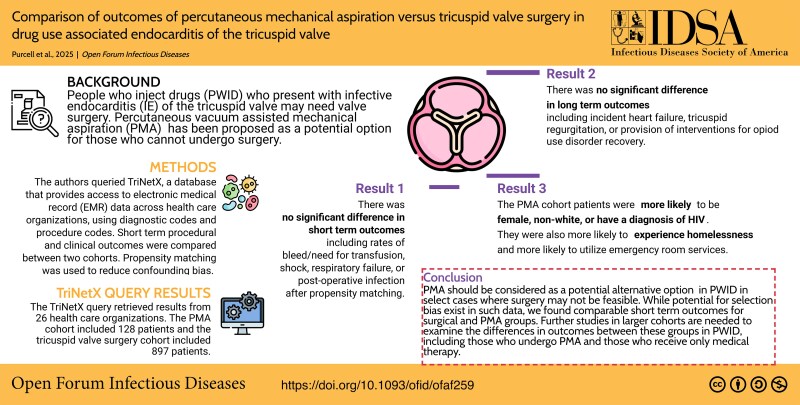

People who inject drugs (PWID) and present with infective endocarditis (IE) of the tricuspid valve may need valve surgery due to persistent infection, heart failure, or embolic risk. Vacuum-assisted percutaneous mechanical aspiration (PMA) has been proposed as a potential option for those who cannot undergo surgery.

Methods

We queried TriNetX, a database that provides access to electronic medical record data across health care organizations, to identify PWID who had tricuspid valve IE and underwent PMA between 2016 and 2024, using diagnostic and procedure codes. Short-term procedural and clinical outcomes were compared with PWID who underwent tricuspid valve surgery.

Results

In total, 129 patients underwent the PMA procedure and 952 had valve surgery. A higher proportion of the PMA cohort was female (66% vs 57%) and of non-White race (32% vs 22.5%). At 1 month postprocedure, the surgical group had a lower rate of death (2.5% vs 7.9%, P = .001), while the PMA group had a lower risk of heart block or need for pacemaker implantation (0% vs 4%). After propensity matching between groups, these differences were not significant. At 1 year postprocedure, groups had similar rates of heart failure, tricuspid insufficiency, or offer of treatment intervention for opioid use disorder.

Conclusions

Short-term outcomes seem comparable between PMA and tricuspid valve surgery in tricuspid valve IE in PWID. Additional studies with larger cohort numbers are needed to further evaluate the difference in long-term postoperative outcomes between the groups.

Keywords: AngioVac, percutaneous mechanical aspiration, PWID, tricuspid endocarditis, tricuspid valve replacement

Percutaneous mechanical aspiration in people who inject drugs and present with tricuspid valve endocarditis may have comparable short-term procedural and clinical outcomes to those who have valve surgery.

Graphical Abstract

Graphical Abstract.

This graphical abstract is also available at Tidbit: https://tidbitapp.io/tidbits/comparison-of-outcomes-of-percutaneous-mechanical-aspiration-versus-tricuspid-valve-surgery-in-drug-use-associated-endocarditis-of-the-tricuspid-valve?utm_campaign=tidbitlinkshare&utm_source=IO

There are approximately 4.5 to 6.6 million people who inject drugs (PWID) in the United States, which represents approximately 1.8% to 3.3% of the population [1]. Over the past decade, there has been a significant increase in trends of the number of PWID [1, 2]. PWID are at higher risk of invasive infections such as bacteremia and drug use–associated infective endocarditis (DUA-IE), and there has been a proportional increase in these conditions in the last 10 years [3, 4]. This has been reflected in trends of greater health care utilization for DUA-IE, including increases in rates of cardiac valve surgery for this condition [5–7]. Some studies have shown that 33% of valve operations performed for infective endocarditis (IE) are for DUA-IE [8]. DUA-IE is also more likely to involve the native tricuspid valve and has higher reported rates of recurrence [7]. These patients have more complicated or prolonged hospital lengths of stay, have high rates of self-directed discharge, and have high rates of need for repeat valve surgery and mortality in the posthospitalization period [8–10]. Individuals with DUA-IE are unique in that they are more likely to be younger, to have adverse social determinants of health (eg, lack of stable housing), and to have challenges with adherence to traditional prescribed processes of care. Yet, they are less likely to have other cardiovascular comorbidities when compared with those with non–DUA-IE [7, 9].

The management of IE may include surgical repair/replacement in addition to prolonged courses of antibiotic therapy and management of complications of infection. The majority of tricuspid valve IE is managed medically, and tricuspid valve surgery accounts for the minority of valve procedures for IE from previous data [11]. However, where indications exist for valve surgery for tricuspid IE, PWID may be deemed poor candidates for surgery due to fear of suboptimal outcomes and to concern for nonadherence and recurrent infection [12]. The 2015 American Heart Association scientific statement on the diagnosis and management of IE goes so far as to state that it is reasonable to avoid surgery, when possible, in PWID [13]. The perspectives of cardiac surgeons may lean away from operative management in PWID [12]. The American Heart Association also issued a scientific statement in 2022 specifically addressing management of DUE-IE, which highlighted the role of individualized multidisciplinary care. This statement acknowledged the barriers that these individuals may face and the need to weigh patient priorities and preferences [14]. It also makes brief mention of catheter-based techniques, such as percutaneous mechanical aspiration (PMA). Such techniques have emerged as an option for debulking tricuspid valve vegetations for source control in the management of tricuspid valve IE, where surgical valve repair may not be feasible due to high risk [14, 15]. However, rigorous criteria for use of this procedure in DUA-IE are lacking.

PMA may be offered as an alternative to operative management or as a bridge to surgery. The rationale behind PMA is that decreasing vegetation burden can result in greater antibiotic efficacy and prevent structural damage to the heart valves. This could prevent the need for sternotomy and implantation of prosthetic material during valve surgery if there is concern for risk of recurrence. It could also be used to debulk vegetations, which are associated with cardiac implantable electronic devices, or large bulky vegetations, which have high embolic risk [16]. The risk of peri- or postoperative complications is plausibly lower and may allow for quicker recovery. The use of PMA as a salvage therapy due to high operative risk may represent a minority of DUA-IE, and considerations such as recurrence risk may influence choice of procedure [17]. To this end, PMA has been added to the 2023 European Society of Cardiology guidelines as a class IIb recommendation for the treatment of right-sided IE in patients at high risk [18].

Given the increase use of PMA, there is a growing need for studies comparing the outcomes data of patients treated with PMA vs operative management. Unfortunately, most published data are in limited single-center case series or reports. They show comparable clinical outcomes, short-term mortality, and potentially shorter length of hospital stay for PMA as compared with surgically managed IE [16, 17]. The lack of clear guidelines or selection criteria and the lack of control for potential confounders make it difficult to compare outcomes or allow for generalizability. To address this, we present in this article a novel use of TriNetX, a large federated electronic health record (EHR)–based database across multiple health care organizations, to compare outcomes of anonymized patients.

METHODS

This multicenter retrospective cohort study compared the outcomes of DUA-IE in people who underwent PMA (intervention) and tricuspid valve surgery (comparator). Our hypothesis was that there should be no differences in clinical outcomes between those treated by PMA and those who underwent surgical repair.

Data Source and Cohort

We queried TriNetX, which is a global federated health research network providing access to real-world deidentified data from EHRs (diagnoses, procedures, medications, laboratory values, genomic information) across large health care organizations and covering diverse populations and locations [19]. We queried the research collaborative network of 97 health care organizations, primarily in North America, that contribute deidentified electronic medical record data to a central database. The platform has built-in functions that work on the deidentified data and can be used for cohort selection and matching, analysis of incidence and prevalence, and comparison of characteristics and outcomes between matched cohorts. Density plot data before and after matching cohorts are presented in Supplementary Figure 1.

Exposure

We included patients with International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision (ICD-10) diagnosis codes of IE and used Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) and ICD-10 Procedure Coding System codes for the AngioVac PMA with a time constraint of 6 weeks between procedure and IE diagnosis. We then identified persons within this group who had ICD-10 diagnosis codes for substance use disorder for opioids, cocaine, and stimulants. Substance use codes were not time constrained and were available from any point in the medical record. A full list of the ICD-10 codes used is in Supplementary Table 1. Data were extracted in July 2024 and had a look-back period of 8 years.

The comparison group was persons who had a substance use disorder and IE diagnosis based on the same ICD-10 codes and had CPT codes of tricuspid valve repair, replacement (valvuloplasty with or without ring insertion), or valvectomy but did not have a PMA procedure code. All codes used in the extraction template are provided in the Supplementary Materials.

The primary outcome was composite of cardiac arrest/death and procedural or postoperative complications within the 30-day period postprocedure. These included occurrence of shock or respiratory failure (ICD-10 Clinical Modification diagnostic codes), need for transfusion (CPT codes), postoperative infection, heart block of grade ≥2 or need for placement of permanent pacemaker (CPT/Procedure Coding System codes), and tricuspid regurgitation. In the 1-year period postprocedure, we looked at incident diagnosis of heart failure, recurrent IE, and interventions targeted at recovery from substance/opioid use disorder. These included prescription of medications for opioid use disorder and individual/group or family therapy and medication management for opioid use disorder. Time windows for these outcomes began 1 day after the first occurrence and ended 30 days or 365 days after the index event.

Baseline covariables extracted included demographic factors, substance use–related comorbid conditions (HIV, infectious hepatitis), and medical comorbidities such as liver or renal failure. We extracted covariables for inclusion in propensity score models that we thought were likely to confound the association between procedure and primary outcome. The TriNetX built-in propensity score–matching function was used, which employs 1:1 matching with a nearest-neighbor greedy matching algorithm, with a caliper of 0.1 times the standard deviation without pair replacement to create balanced cohorts. Propensity score matching was performed on 9 characteristics: age, sex, race, end-stage liver or kidney disease, presence of shock or heart failure, and rates of hospital or emergency room utilization.

Balance between cohorts after propensity matching was assessed by density curves, and an absolute standardized mean difference <0.1 indicated similarity. The fraction of patients with the selected outcomes between the PMA and tricuspid valve replacement groups was compared at 30 days and 1 year prior to and after matching. The risk difference, risk ratio, and odds ratio were calculated, and t tests were used for differences in outcomes between the cohorts. Kaplan-Meier curves were constructed to evaluate primary and other clinical outcomes at 1 year between the PMA and surgical groups. Censoring was applied to account for patients who exited the cohort during the analysis period. The log-rank test, hazard ratio, and test for proportionality were also calculated.

The study protocol was reviewed by the institutional review board at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, and deemed exempt from informed consent and full review.

RESULTS

An overall 97 health care organizations were queried, of which 26 responded with patient data. The final cohort included 129 patients with a PMA procedure and 952 with tricuspid valve surgery. The demographics of the patients in each cohort are listed in Table 1. Baseline demographics showed that a higher proportion of the PMA cohort was female (66% vs 57%) and of non-White race (32% vs 22.5%). A higher proportion of the PMA group had an HIV diagnosis (8% vs 2%). There were differences in rates of diagnosis of cirrhosis of the liver and end-stage renal disease. A higher proportion of patients with PMA (19%) also had diagnosis codes for people experiencing homelessness (Z59) as compared with the surgical group (10.5%), and this group had higher rates of emergency room service utilization (62% vs 41%; Table 1).

Table 1.

Demographics of Patients Included in the Study

| Prematching | Postmatching | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PMA (n = 129) | Surgery (n = 952) | P Value | PMA (n = 125) | Surgery (n = 125) | Standard Difference | |

| Age at event, y, mean (SD) | 35.2 (9.4) | 35.4 (10.4) | … | 35 (9.3) | 34.7 (10.5) | 0.026 |

| Male | 44 (34) | 409 (43) | .056 | 43 (34) | 43 (34) | <0.001 |

| Non-White race | 41 (32) | 214 (22.5) | .019 | 37 (30) | 35 (28) | 0.035 |

| Cocaine-related disorder diagnosis | 33 (25.5) | 213 (22) | .075 | 30 (24) | 28 (22.5) | 0.038 |

| Prescribed | ||||||

| Methadone | 30 (23) | 210 (22) | … | 28 (22.5) | 26 (21) | 0.039 |

| Buprenorphine | 42 (33) | 270 (28) | … | 42 (34) | 36 (29) | 0.1 |

| HIV positive | 10 (8) | 19 (2) | <.001 | 10 (8) | 10 (8) | <0.001 |

| Diagnosis | ||||||

| Hepatitis C | 39 (30) | 282 (30) | … | 37 (30) | 37 (30) | <0.001 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 13 (10) | 97 (10) | … | 11 (9) | 10 (8) | 0.03 |

| Septic arterial embolism | 61 (47) | 447 (47) | … | 58 (46) | 61 (49) | 0.05 |

| Heart failure diagnosis | 33 (26) | 348 (36) | .014 | 32 (26) | 31 (25) | 0.018 |

| Cirrhosis of liver | 10 (8) | 38 (4) | .05 | 10 (8) | 10 (8) | <0.001 |

| End-stage renal disease | 10 (8) | 35 (4) | .03 | 10 (8) | 10 (8) | <0.001 |

| Homelessness | 25 (19) | 100 (10.5) | .003 | 24 (19) | 16 (13) | 0.17 |

| Emergency room utilization | 80 (62) | 394 (41) | <.001 | 76 (61) | 65 (52) | 0.184 |

| Hospital inpatient or observation care services | 100 (77.5) | 717 (75) | … | 97 (77) | 91 (73) | 0.096 |

Data are presented as No. (%) unless noted otherwise.

P values are provided only for values <0.1.

Abbreviation: PMA, percutaneous mechanical aspiration.

Prior to matching, there was lower risk of cardiac arrest or death in the surgical group (2.5% vs 7.9%) at 1 month after the index event (risk difference, 5.4%; 95% CI, −.6% to 10.2%; P = .001). The PMA group had a lower risk of grade ≥2 heart block or need for permanent pacemaker placement vs the surgical group (0% vs 4%). Rates of bleeding and need for transfusion, shock, or respiratory failure were not different between groups. Rates of postoperative infection were surprisingly higher in the PMA group (8.3% vs 4.1%; risk difference, 4.2%; 95% CI, .9%–9.2%; P = .04). After propensity matching, the differences seen between groups were no longer statistically significant (Table 2).

Table 2.

Primary and Secondary Outcomes at 1 Month and 1 Year With and Without Propensity Scoring

| Before Matching | After Matching | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Outcome | PMA | Surgery | Risk Difference (95% CI) | P Value | PMA | Surgery | Risk Difference (95% CI) | P Value |

| 30 d postevent | ||||||||

| Cardiac arrest or death | 0.079 (10/126) | 0.025 (23/906) | 0.054 (.006, .102) | .001 | 0.085 (10/117) | 0.088 (10/114) | −0.002 (−.075, .070) | .95 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | 0.103 (10/97) | 0.092 (38/413) | 0.011 (−.056, .078) | .74 | 0.111 (10/90) | 0.217 (10/46) | −0.106 (−.242, .029) | .09 |

| Grade ≥2 heart block or pacemaker insertion | 0 (0/126) | 0.04 (27/616) | −0.044 (−.060, −0.028) | .02 | 0 (0/118) | 0.112 (10/78) | −0.128 (−.202, −0.054) | .00 |

| Bleeding or transfusion | 0.111 (10/90) | 0.161 (68/422) | −0.050 (−.124, .024) | .23 | 0.122 (10/82) | 0.182 (10/55) | −0.060 (−.184, .064) | .33 |

| Shock or respiratory failure | 0.246 (32/129) | 0.220 (209/952) | 0.027 (−.052, .105) | .5 | 0.231 (28/121) | 0.231 (28/121) | 0 (−.106, .106) | >.99 |

| Postoperative infection | 0.083 (10/121) | 0.041 (36/877) | 0.042 (−.009, .092) | .04 | 0.089 (10/112) | 0.090 (10/111) | −0.001 (−.076, .074) | .98 |

| 1 y postevent | ||||||||

| Heart failure | 0.135 (13/96) | 0.148 (84/566) | −0.013 (−.087, .061) | .74 | 0.144 (13/90) | 0.148 (13/88) | 0.003 (−.107, .101) | .95 |

| Tricuspid regurgitation | 0.186 (18/97) | 0.169 (70/413) | 0.016 (−.069, .101) | .71 | 0.198 (18/91) | 0.2 (10/50) | −0.002 (−.140, .136) | .97 |

| Recurrent IE | 0 | 0.235 (16/68) | … | 0 | 1 (10/10) | … | … | |

| OUD recovery interventions | 0.418 (28/67) | 0.337 (144/427) | 0.081 (−.046, .207) | .197 | 0.443 (27/61) | 0.407 (22/54) | 0.035 (−.146, .216) | .70 |

Data are presented as proportion (No.) unless noted otherwise.

Abbreviations: IE, infective endocarditis; OUD, opioid use disorder; PMA, percutaneous mechanical aspiration.

For the 1-year period postprocedure, incident heart failure (14.4% in PMA group and 14.8% in surgical group), tricuspid regurgitation (19.8% and 20%), and provision of interventions for opioid use disorder recovery (44.3% and 41%) were also not statistically different between groups prior to or after propensity matching.

DISCUSSION

Our results show some significant baseline differences between patients who underwent PMA and surgery for DUA-IE. While there were differences in short-term perioperative complications and mortality between the groups, these differences were not significant after matching the patients. TriNetX has provided valuable insight into risk factors, trends in utilization, as well as outcomes related to COVID-19 during a period when background knowledge and clinical data were emergent and data from large collaborative networks were not easily accessible to those not within such networks [20–22]. To date, most published literature on the use of PMA is in the form of case reports or single-center case series and may have limited sample sizes [16, 23–26]. We attempt to address this by accessing data from this larger database.

We note that PWID who undergo a PMA procedure have many differences in comorbid conditions, which may account for potential selection bias or confounding. Besides technical feasibility and selection based on operative risk, provider or institutional factors may guide selection of procedure. One may assume that patients who are more critically ill, who may be deemed high operative risk, might preferentially be offered PMA. However, PWID with IE are usually younger and have fewer comorbidities [27]. We do note some demographic differences for which we do not have a clear explanation, such as the fact that women account for 77% of the PMA group. Prior case series have not shown this preponderance. Some studies have noted higher representation of females in hospitalized cases of DUA-IE. This has been ascribed to the higher health care–seeking behavior but difficulty accessing harm reduction services [28, 29]. Why women would be overrepresented in the nonoperative group is not clear, but plausibly they could opt for a nonoperative approach, since data show that women are less likely to undergo surgery for DUA-IE [29, 30]. While DUA-IE predominantly affects people who are White, non-White populations have higher mortality risk [27, 31]. Prevalent health care access disparities—including access to substance use treatment, disease severity, and comorbidity burden—and systemic barriers, including racism and implicit bias, may play a role in delayed diagnosis or higher severity of presentation [32–34].

Procedural complications such as bleeding, shock or respiratory failure, and postprocedural infection did not seem to differ between groups. Even though death in the 30-day period was higher in the PMA group, after matching for comorbid conditions, this difference seemed to be nonsignificant. This indicates that the procedure might be offered to people who had more comorbidities or possibly higher severity of illness. Postprocedural worsening of tricuspid regurgitation has been shown to be a risk, perhaps from valve damage, but this did not seem to be different between groups [35, 36]. Around 7% of tricuspid valve repair procedures are complicated by heart block, and this risk might be higher with replacement [37]. This could be from surgical complications but also could be related to perivalvular complications of IE. In our analysis, the occurrence of high-grade heart block or pacemaker implantation was not significantly different between groups after matching.

There are not many studies directly comparing PMA and tricuspid valve replacement, and out of the studies that exist, only 1 has compared them in PWID. Veve et al compared PMA and tricuspid valve replacement in PWID [26]. Their study showed similar outcomes in 12-month mortality between those who underwent PMA and tricuspid valve replacement surgery, with an increased amount of tricuspid regurgitation in the PMA group, which we did not see in our larger analysis.

The theoretical benefit of more rapid recovery time, lower need for intensive care, and less prolonged mechanical ventilation in PMA as compared with surgery could be an advantage and allow for PWID to focus on their substance use recovery. George et al showed that PMA was associated with shorter lengths of stay in the hospital (35 vs 45 days, P = .028) [25]. The use of 2 venous access sites for aspiration and reinfusion can lead to access site bleeding. Registry data of PMA device use show a 25% risk of bleeding needing transfusion [38]. We did not see higher rates of bleeding between groups.

We acknowledge many limitations of this study. We did attempt to retrieve rates of incident death or repeat surgery within a 1-year period after the initial intervention, but the number of patients identified was too small to do any meaningful comparison between the groups. This may reflect not only a limitation in trying to ascertain these outcomes by using EHR data but also the challenges with continued engagement in chronic care services within medical systems among PWID [39]. EHR data may be inaccurate or incomplete and lack information on confounders. Data from ICD-10 diagnosis codes may lack sensitivity to identify DUA-IE [40]. We hypothesize that it may retain specificity due to the use of procedural codes and hence positive predictive value. As such, this indicates that our data may be an underestimate of the true prevalence of this condition. Additionally, the TriNetX database does not capture patients who might have had health care encounters outside the network, rural populations, or outcomes that occur outside the medical record and are not captured within EHRs. PWID often encounter significant challenges in accessing care within traditional systems. They also have high rates of patient-directed discharge and incomplete therapy. Even though we tried to match for conditions that may indicate severity of illness, selection bias due to surgical team preference or practice cannot be eliminated. The outcomes of such encounters are obviously missing from the data [41]. Additionally, there may be a possibility for type II error given that propensity score matching reduced the number of individuals receiving surgical procedures. Finally, the reported numbers can vary with each retrieval because data are continuously updated and refreshed by the uploading health care organization.

There has been a growing movement toward offering patient-centered care, which leverages hospitalization as a reachable moment and provides coordinated clinical care in a shared decision-making framework [14]. Traditional valve surgery may not be feasible or acceptable to some PWID. PMA may be offered within the context of other treatment options, which may be more acceptable or relevant. The patients who receive this intervention may have higher comorbid illness or severity of infection, but the comparable short-term outcomes after matching may suggest that this can be considered an option for a subset of these patients. Further research and real-world data are needed to evaluate meaningful outcomes, such as mortality and need for resurgery in the long term.

CONCLUSIONS

PMA is an option for PWID with tricuspid valve IE as a potential definitive treatment option in selected cases and has comparable short-term outcomes to valve surgery. Additional studies with larger cohort numbers are needed to further evaluate the difference in long-term postoperative outcomes between PMA and tricuspid valve replacement surgery.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Madeleine Purcell, Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Sergey Gnilopyat, Department of Medicine, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Bhargav Makwana, Department of Medicine, Lahey Hospital and Medical Center, Burlington, Massachusetts, USA.

Shivakumar Narayanan, Institute of Human Virology, University of Maryland School of Medicine, Baltimore, Maryland, USA.

Supplementary Data

Supplementary materials are available at Open Forum Infectious Diseases online. Consisting of data provided by the authors to benefit the reader, the posted materials are not copyedited and are the sole responsibility of the authors, so questions or comments should be addressed to the corresponding author.

References

- 1. Lansky A, Finlayson T, Johnson C, et al. Estimating the number of persons who inject drugs in the United States by meta-analysis to calculate national rates of HIV and hepatitis C virus infections. PLoS One 2014; 9:e97596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Bradley H, Hall EW, Asher A, et al. Estimated number of people who inject drugs in the United States. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76:96–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wurcel AG, Anderson JE, Chui KKH, et al. Increasing infectious endocarditis admissions among young people who inject drugs. Open Forum Infect Dis 2016; 3:ofw157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Schranz A, Barocas JA. Infective endocarditis in persons who use drugs: epidemiology, current management, and emerging treatments. Infect Dis Clin North Am 2020; 34:479–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Schranz AJ, Fleischauer A, Chu VH, Wu L-T, Rosen DL. Trends in drug use–associated infective endocarditis and heart valve surgery, 2007 to 2017: a study of statewide discharge data. Ann Intern Med 2019; 170:31–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. McCarthy NL, Baggs J, See I, et al. Bacterial infections associated with substance use disorders, large cohort of United States Hospitals, 2012–2017. Clin Infect Dis 2020; 71:E37–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yucel E, Bearnot B, Paras ML, et al. Diagnosis and management of infective endocarditis in people who inject drugs: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol 2022; 79:2037–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Geirsson A, Schranz A, Jawitz O, et al. The evolving burden of drug use associated infective endocarditis in the United States. Ann Thorac Surg 2020; 110:1185–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Mori M, Brown KJ, Bin Mahmood SU, Geirsson A, Mangi AA. Trends in infective endocarditis hospitalizations, characteristics, and valve operations in patients with opioid use disorders in the United States: 2005–2014. J Am Heart Assoc 2020; 9:e012465. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Shrestha NK, Jue J, Hussain ST, et al. Injection drug use and outcomes after surgical intervention for infective endocarditis. Ann Thorac Surg 2015; 100:875–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Gaca JG, Sheng S, Daneshmand M, et al. Current outcomes for tricuspid valve infective endocarditis surgery in North America. Ann Thorac Surg 2013; 96:1374–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Nguemeni Tiako MJ, Mszar R, Brooks C, et al. Cardiac surgeons' treatment approaches for infective endocarditis based on patients' substance use history. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2021; 33:703–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Baddour LM, Wilson WR, Bayer AS, et al. Infective endocarditis in adults: diagnosis, antimicrobial therapy, and management of complications. Circulation 2015; 132:1435–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Baddour LM, Weimer MB, Wurcel AG, et al. Management of infective endocarditis in people who inject drugs: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 2022; 146:E187–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. El-Dalati S, Sinner G, Leung S, et al. Comparison of medical therapy, valve surgery, and percutaneous mechanical aspiration for tricuspid valve infective endocarditis. Am J Med 2024; 137:888–95.e2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. El Sabbagh A, Yucel E, Zlotnick D, et al. Percutaneous mechanical aspiration in infective endocarditis: applications, technical considerations, and future directions. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv 2024; 3:101269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Starck CT, Dreizler T, Falk V. The AngioVac system as a bail-out option in infective valve endocarditis. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2019; 8:675–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Delgado V, Ajmone Marsan N, de Waha S, et al. 2023 ESC guidelines for the management of endocarditis. Eur Heart J 2023; 44:3948–4042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Palchuk MB, London JW, Perez-Rey D, et al. A global federated real-world data and analytics platform for research. JAMIA Open 2023; 6:ooad035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Singh S, Bilal M, Pakhchanian H, Raiker R, Kochhar GS, Thompson CC. Impact of obesity on outcomes of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in the United States: a multicenter electronic health records network study. Gastroenterology 2020; 159:2221–5.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ganatra S, Dani SS, Ahmad J, et al. Oral nirmatrelvir and ritonavir in nonhospitalized vaccinated patients with coronavirus disease 2019. Clin Infect Dis 2023; 76:563–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wang L, Wang QQ, Davis PB, Volkow ND, Xu R. Increased risk for COVID-19 breakthrough infection in fully vaccinated patients with substance use disorders in the United States between December 2020 and August 2021. World Psychiatry 2022; 21:124–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Poliwoda SD, Durbach JR, Castro A, et al. AngioVac system for infective endocarditis: a new treatment for an old disease. Ann Card Anaesth 2023; 26:105–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Mhanna M, Beran A, Al-Abdouh A, et al. AngioVac for vegetation debulking in right-sided infective endocarditis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Curr Probl Cardiol 2022; 47:101353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. George B, Santos P, Donaldson K, et al. A retrospective comparison of tricuspid valve surgery to tricuspid valve vegetation debulking with AngioVac for isolated tricuspid valve endocarditis. JACC 2019; 73:1973. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Veve MP, Akhtar Y, McKeown PP, Morelli MK, Shorman MA. Percutaneous mechanical aspiration vs valve surgery for tricuspid valve endocarditis in people who inject drugs. Ann Thorac Surg 2021; 111:1451–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Kadri AN, Wilner B, Hernandez AV, et al. Geographic trends, patient characteristics, and outcomes of infective endocarditis associated with drug abuse in the United States from 2002 to 2016. J Am Heart Assoc 2019; 8:e012969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. McCrary LM, Cox ME, Roberts KE, et al. Endocarditis, drug use and biological sex: a statewide analysis comparing sex differences in drug use–associated infective endocarditis with other drug-related harms. Int J Drug Policy 2024; 123:104280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Adams JA, Spence C, Shojaei E, et al. Infective endocarditis among women who inject drugs. JAMA Netw Open 2024; 7:e2437861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Nguemeni Tiako MJ, Mori M, Bin Mahmood SU, et al. Recidivism is the leading cause of death among intravenous drug users who underwent cardiac surgery for infective endocarditis. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2019; 31:40–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Schranz A, Figgatt M, Chu V, Wu L-T, Rosen D. Long-term mortality after drug use–associated endocarditis is high and differs by race and sex: results of a statewide study. Drug Alcohol Depend 2024; 260:110566. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Hajela R. Addiction is more than a substance use disorder. J Addict Med 2017; 11:331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Hall WJ, Chapman MV, Lee KM, et al. Implicit racial/ethnic bias among health care professionals and its influence on health care outcomes: a systematic review. Am J Public Health 2015; 105:e60–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bailey ZD, Krieger N, Agénor M, Graves J, Linos N, Bassett MT. Structural racism and health inequities in the USA: evidence and interventions. Lancet 2017; 389:1453–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Fallon JM, Newman N, Patel PM, et al. Vacuum-assisted extraction of ilio-caval and right heart masses: a 5-year single center experience. J Card Surg 2020; 35:1787–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. George B, Voelkel A, Kotter J, Leventhal A, Gurley J. A novel approach to percutaneous removal of large tricuspid valve vegetations using suction filtration and veno-venous bypass: a single center experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2017; 90:1009–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Kratz JM, Crawford FA, Stroud MR, Appleby DC, Hanger KH. Trends and results in tricuspid valve surgery. Chest 1985; 88:837–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Moriarty JM, Rueda V, Liao M, et al. Endovascular removal of thrombus and right heart masses using the AngioVac system: results of 234 patients from the prospective, multicenter Registry of AngioVac Procedures in Detail (RAPID). J Vasc Interv Radiol 2021; 32:549–57.e3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Rowe TA, Jacapraro JS, Rastegar DA. Entry into primary care-based buprenorphine treatment is associated with identification and treatment of other chronic medical problems. Addict Sci Clin Pract 2012; 7:22. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Barnes E, Peacock J, Bachmann L. International Classification of Diseases (ICD) codes fail to accurately identify injection drug use associated endocarditis cases. J Addict Med 2022; 16:27–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Kimmel SD, Kim J-H, Kalesan B, Samet JH, Walley AY, Larochelle MR. Against medical advice discharges in injection and non-injection drug use–associated infective endocarditis: a nationwide cohort study. Clin Infect Dis 2021; 73:e2484–92. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.