Abstract

In this study, we sought to identify key molecular players in both thyroid cancer (TC) and Hashimoto's thyroiditis (HT) by analyzing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and their potential as biomarkers. We utilized datasets from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database and identified CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 as hub genes common to both TC and HT. These genes were significantly upregulated in TC cell lines compared to normal controls, with high diagnostic accuracy as indicated by Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve analysis. Further validation using the TCGA TC dataset revealed their significant upregulation in tumor tissues, particularly in advanced TC stages. Promoter methylation analysis indicated hypomethylation of these genes in TC, suggesting a role of methylation in their regulation. We also observed mutations and copy number variations (CNVs) in these hub genes, with CLTA and HIP1 showing significant amplifications, which may contribute to their overexpression in tumor samples. In addition, we conducted a meta-analysis to assess the impact of these genes on survival outcomes in TC patients, with results indicating that higher expression of HAPLN1 and HIP1 was associated with poor survival. Our study also highlighted the involvement of CLTA and EDIL3 in activating the Rap1 signaling pathway, crucial for cancer cell migration, proliferation, and invasion. These findings emphasize the potential of CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets for TC and HT.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s10238-025-01689-w.

Keywords: Thyroid cancer, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, Biomarker, Therapeutic target, Proliferation

Introduction

Hashimoto's thyroiditis (HT) and thyroid cancer (TC) are two prevalent thyroid disorders with distinct pathophysiological mechanisms yet some overlapping molecular characteristics [1, 2]. HT is an autoimmune disease that leads to chronic inflammation of the thyroid gland, often resulting in hypothyroidism [3, 4]. It is marked by an infiltration of immune cells, particularly lymphocytes, and the production of thyroid-specific autoantibodies that cause thyroid cell destruction [5, 6]. On the other hand, TC is a malignant tumor of the thyroid gland, with the most common form being papillary thyroid carcinoma (PTC), followed by follicular, medullary, and anaplastic types [7]. Both diseases present distinct molecular features; however, their relationship and shared molecular pathways have not been extensively explored. The global prevalence of HT is increasing, with estimates suggesting that around 5% of the global population is affected, with a significant female predominance [8]. HT is most commonly diagnosed in individuals aged 30–50 years, and its prevalence has risen in recent decades due to improved diagnostic methods and heightened awareness [9]. In 2024, it is expected that over 400 million people globally will be diagnosed with HT, with the disease contributing significantly to cases of hypothyroidism worldwide [10]. Thyroid cancer is also on the rise, with more than 500,000 new cases expected annually by 2024 [11]. This is primarily driven by advancements in imaging techniques and early detection, as well as lifestyle factors and genetic predispositions [12]. Although thyroid cancer has a high survival rate, particularly in the case of papillary thyroid carcinoma, there is a growing concern regarding the increasing incidence of more aggressive forms, such as anaplastic thyroid carcinoma, which poses significant therapeutic challenges.

Despite significant research into HT and TC, there remains a notable gap in identifying shared biomarkers and therapeutic targets for these diseases. Although both diseases are associated with thyroid dysfunction, autoimmune responses, and immune system involvement, few studies have attempted to draw comparisons or highlight common molecular pathways between HT and TC [13, 14]. Current diagnostic methods primarily rely on imaging, histopathological examination, and the assessment of thyroid antibodies, but the lack of reliable molecular biomarkers limits the accuracy of diagnosis and the effectiveness of targeted therapies. Furthermore, while both diseases involve altered gene expression, their molecular bases are poorly understood. For example, while TC is often associated with mutations in genes such as BRAF, RAS, and RET, and HT with autoimmunity markers like TPO (thyroid peroxidase) and TG (thyroglobulin) [15], there is little integration of these findings to identify biomarkers or therapeutic targets that are common to both diseases. This study aims to fill this gap by using bioinformatics tools to analyze the gene expression data from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database [16, 17] and identify overlapping genes and pathways involved in both conditions.

Several studies have already investigated the molecular mechanisms underlying HT and TC, though most have focused on each disease independently, without addressing their potential overlap. For HT, research has identified several genes and pathways involved in the autoimmune response, such as TPO, TG, CTLA-4, and PTPN22, which are involved in immune regulation and thyroid gland inflammation [18, 19]. For example, TPO and TG are thyroid-specific antigens that are often elevated in the serum of HT patients, making them key diagnostic markers for the disease [9]. In addition, studies have shown that PTPN22, a gene involved in T-cell regulation, is upregulated in HT, contributing to the autoimmune attack on thyroid tissue [2]. In thyroid cancer, several oncogenes and tumor suppressor genes have been well-characterized. Mutations in BRAF (particularly V600E), RAS, RET, and TP53 have been shown to be frequent in various types of thyroid cancer, especially in PTC [20]. The BRAF V600E mutation is particularly important, as it has been linked to tumor aggressiveness and poor prognosis [21, 22]. Other genes, such as NKX2-1 and FOXE1, have also been implicated in thyroid carcinogenesis, affecting cell differentiation and survival.

However, studies integrating the molecular landscapes of HT and TC are scarce, particularly those exploring the shared pathways between these two conditions. While HT is primarily considered an autoimmune disorder and TC as a neoplastic condition, recent research has suggested potential crosstalk between inflammation, immune responses, and cancer progression. For instance, genes involved in inflammation such as TNF-α and IL-6, and immune checkpoint inhibitors like PD-1/PD-L1, have been shown to be dysregulated in both HT and TC [23], although their exact roles and interactions remain unclear. In our study, we used GEO datasets to explore the gene expression profiles of HT and TC, aiming to identify common biomarkers and therapeutic targets. We then validate these findings using bioinformatics tools [24, 25] and detailed in vitro experiments [26, 27].

Methodology

Data retrieval, analysis, and identification of hub genes in TC and HT

To identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in TC and HT, we retrieved datasets from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/) [16], including two TC datasets (GSE53157 and GSE153659) and two HT datasets (GSE54958 and GSE138198). Data preprocessing steps were performed prior to DEG analysis to ensure the reliability and reproducibility of the results. Specifically, all raw gene expression data were first normalized to correct for any technical variation between samples, ensuring that the results reflect biological differences rather than technical biases. For normalization, we used the quantile normalization method, which adjusts for differences in overall intensity distribution across samples. This method was chosen to ensure that each dataset could be directly compared by aligning the distributions of expression values. Additionally, batch effects—systematic variations that could arise from differences in experimental conditions, platforms, or other external factors—were corrected using the ComBat method, an empirical Bayes approach available in the sva R package. Batch effect correction is crucial to prevent confounding factors from influencing the DEG analysis, particularly when datasets are collected from different platforms or studies. After normalization and batch effect correction, we performed DEG analysis using the limma package (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/limma.html) in R, which is a widely used tool for analyzing differential expression in high-throughput data. Differential expression was visualized through volcano plots, where the x-axis represents log2 fold change (LogFC) and the y-axis represents the -log10 of the p-value. A LogFC cutoff value of |LogFC|≥ 1 was applied, corresponding to a fold change of ≥ 2 in gene expression, to identify significantly upregulated or downregulated genes. Additionally, genes with an adjusted p-value (Padj) < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Finally, a Venn diagram was used to compare the top 2000 DEGs identified across all four datasets, highlighting the overlap of DEGs between TC and HT samples. For Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) analysis of the common genes, we used the STRING database (https://string-db.org/) [28] to construct the interaction networks. The PPI network was visualized using the Cytoscape software (https://cytoscape.org/). To identify the most important genes within the interaction network, we applied the CytoHubba application in Cytoscape. This tool calculates the "degree" of each node (representing genes) in the network, where the degree is the number of interactions a protein has with other proteins. Genes with the highest degree values were considered to have the most central roles in the network, thus providing a measure of their importance in the biological processes associated with TC and HT. The rationale for using the degree method is based on the premise that highly connected proteins are likely to be functionally important, influencing key pathways involved in disease development. Through this method, CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 emerged as the most significant hub genes, with the highest interaction frequencies. These genes were selected for further analysis due to their central roles in the PPI network and their potential involvement in the molecular mechanisms underlying TC and HT. This focused analysis using the degree method allowed us to narrow down the list of potential biomarkers from overlapping DEGs to four key genes that could serve as promising candidates for further experimental validation and clinical application.

Cell culture

In this study, we purchased 10 TC cell lines and 6 normal thyroid cell lines from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), USA. The thyroid cancer cell lines used were TPC1, CAL62, BHT-101, SW1736, K1, KTC1, CGTH-W-1, ARO, C643, and BCPAP, while the normal thyroid cell lines included Nthy-ori 3–1, FRTL-5, HTori-3, NTHY-1, Thy-1, and HTh7. These cell lines were cultured in our laboratory under optimal conditions for comparative analysis of gene expression and molecular characteristics. For TC cell lines, RPMI-1640 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific) supplemented with 10% Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) and 1% Penicillin–Streptomycin (Thermo Fisher Scientific) was used to support their growth. In contrast, the normal thyroid cell lines were cultured in DMEM/F12 medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific), supplemented with 10% FBS and 1% Penicillin–Streptomycin. All cell lines were maintained in a humidified incubator at 37 °C with 5% CO2, with the medium being changed every 2–3 days. Cells were subcultured upon reaching approximately 80% confluence using Trypsin–EDTA (Thermo Fisher Scientific) for detachment.

Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis

To analyze the gene expression of CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, HIP1, Rap1A, and C3G, RNA was extracted from the cultured TC and normal thyroid cell lines. First, cells were collected from the culture plates once they reached 80% confluence, and total RNA was extracted using the RNeasy Mini Kit (Qiagen) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The RNA concentration and quality were assessed using a NanoDrop spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), and only samples with a 260/280 ratio between 1.8 and 2.0 were used for further analysis. Next, the RNA was reverse transcribed into complementary DNA (cDNA) using the High-Capacity cDNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 1 µg of total RNA was used for cDNA synthesis, and the reaction was carried out in a thermal cycler under conditions specified in the kit protocol.

Following cDNA synthesis, RT-qPCR was performed to assess the expression levels of the target genes (CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, HIP1, Rap1A, and C3G) and GAPDH as a housekeeping gene. The RT-qPCR reactions were set up using SYBR Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems) and performed on the QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). The relative expression levels of the target genes were calculated using the 2^-ΔΔCt method, with GAPDH as the internal control for normalization. All the primers used in this study have been listed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Detail of the primers used in the current study

| Gene | Forward Primer Sequence 5′-3′ |

Reverse Primer Sequence 5'-3' |

Optimal Annealing Temperature (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|

| GAPDH | ACCCACTCCTCCACCTTTGAC | CTGTTGCTGTAGCCAAATTCG | 59 °C |

| CLTA | CGATTGCAGTCAGAGCCTGAAAG | TAGCTGCTCGTCCTGTCTTGCA | 60.5 °C |

| EDIL3 | GCGAATGGAACTTCTTGGCTGTG | GAGCGTTCTGAAGATGCTGGAG | 60.5 °C |

| HAPLN1 | CTGTTGTGGTAGCACTGGACTTA | TCACAGCATCCTGGTCCAGACA | 62 °C |

| HIP1 | CCCAGGTAGATTTGGAACGAGAG | TTGGCTTGTGGCAAGTTCCTGC | 61 °C |

| Rap1A | ACTTACAGGACCTGAGGGAACAG | CCTGCTCTTTGCCAACTACTCG | 59.5 °C |

| C3G | TGCCGACACATTCAAGAAGCGC | GGAAGACCAGTTCCATCAGCAG | 62 °C |

The thermal cycling conditions for RT-qPCR reactions were as follows: an initial denaturation step was performed at 95 °C for 10 min to activate the SYBR Green DNA polymerase. This was followed by 40 cycles of amplification, each consisting of denaturation at 95 °C for 15 s, annealing at the optimal temperature for each gene (Table 1) for 30 s, and extension at 72 °C for 30 s. After amplification, a melting curve analysis was performed by increasing the temperature from 60 °C to 95 °C at a rate of 0.1 °C per second to ensure the specificity of the PCR products.

Validation of hub gene expression and Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA) analysis

To validate the expression of the hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1, we utilized the TCGA TC dataset in conjunction with the GSCA database (http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/GSCA/) [29] The GSCA database provides integrated analysis tools for gene expression and clinical data in cancer, allowing for the comparison of gene expression between tumor and normal tissues. The expression levels of the selected hub genes were assessed in both tumor and normal tissue samples from TC. In addition, this database was also utilized for the GSEA analysis of hub genes in TC.

Promoter methylation analysis

To investigate the promoter methylation status and its correlation with gene expression of the hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 in TC, we utilized the OncoDB and GSCA databases. The OncoDB database (http://oncodb.org/) [30] provides information on genetic and epigenetic alterations in cancer, including methylation profiles across different cancer types. The GSCA database [29] integrates cancer genomic data and allows for the analysis of gene expression and methylation status, making it a suitable resource for this study.

Mutational and copy number variation (CNV) analysis

To analyze the mutational and CNV data of the hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 in TC, we utilized the cBioPortal database (https://www.cbioportal.org/) [31], a comprehensive resource for exploring, visualizing, and analyzing multidimensional cancer genomics data. cBioPortal provides access to mutation, copy number, and clinical data from multiple cancer studies, making it an ideal platform for investigating the genetic alterations of specific genes in various cancer types, including TC.

Meta-analysis of survival associations for hub genes

To assess the survival associations of the hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 in thyroid cancer, we conducted a meta-analysis using data from the GENT2 database (http://gent2.appex.kr/gent2/) [32], which integrates gene expression and clinical data from multiple cancer datasets. The GENT2 database provides tools for analyzing the impact of gene expression on patient survival across a variety of cancers, including TC.

Correlation analysis of hub genes with immune regulation and drug sensitivity

The TISIDB database (http://cis.hku.hk/TISIDB/) [33] is a comprehensive resource for studying tumor immune microenvironments, including immune-related gene expression and immune cell infiltration. In this study, we analyzed the correlation between the expression of the hub genes and immune inhibitor genes in TC and other cancers, using the Spearman correlation coefficient. Additionally, we used the GSCA database (http://bioinfo.life.hust.edu.cn/GSCA/) [29], which integrates gene expression and clinical data, to examine the correlation between the expression levels of the hub genes and immune cell infiltration and to perform drug sensitivity analysis in TC.

PPI network and gene enrichment analysis of hub genes

The GeneMANIA database (http://genemania.org/) [34] is a powerful tool for predicting protein interactions and gene function based on functional genomics data, while the STRING database (https://string-db.org/) [28] provides known and predicted protein interactions derived from experimental and computational data. Using both databases, we constructed the PPI networks for the hub genes. In addition, The DAVID database (https://david.ncifcrf.gov/) [35] was used for functional annotation and enrichment analysis of the hub genes and their other binding partners.

Regulatory miRNAs of hub genes

To investigate the potential regulatory miRNAs targeting the hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1, we used TargetScan (http://www.targetscan.org/) [36], a widely used tool for predicting miRNA targets based on conserved miRNA binding sites in the 3' untranslated regions (UTRs) of genes. TargetScan utilizes a large database of miRNA binding predictions and employs algorithms to assess the likelihood of interactions between miRNAs and their target genes.

For the miRNA analysis, we used the TaqMan® MicroRNA Reverse Transcription Kit (Applied Biosystems) to reverse transcribe 100 ng of total RNA into cDNA, specifically targeting the mature miRNAs of interest. RT-qPCR was then performed using TaqMan® MicroRNA Assays (Applied Biosystems) for hsa-miR-142-3p, hsa-miR-137, hsa-miR-23c, and hsa-miR-19a-3p. The reactions were conducted on the QuantStudio 5 Real-Time PCR System (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Data analysis was conducted using the 2^−ΔΔCt method, with RNU6B as the endogenous control for normalization.

Correlation analysis of hub genes

GEPIA2 (http://gepia2.cancer-pku.cn/#index) is a web-based tool for analyzing gene expression data from TCGA and GTEx projects [37]. It provides comprehensive visualizations and statistical analyses for cancer research. In this work, we used GEPIA2 to explore correlations of hub genes with Rap1 key players in TC.

Knockdown of CLTA and EDIL3 in CAL62 and TPC1 cells

To investigate the functional roles of CLTA and EDIL3 in TC, we performed miRNA-mediated knockdown of these hub genes in CAL62 and TPC1 cell lines. First, we transfected the cells with miRNAs targeting CLTA and EDIL3 using Lipofectamine RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Pre-designed miRNA mimics specific to CLTA and EDIL3 (obtained from Thermo Fisher Scientific) were used to reduce the expression of these genes. Non transfected cells were used in parallel to serve as controls. The transfection was carried out in 6-well plates, and the cells were incubated with the transfection mixture for 48 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. After the knockdown procedure, the cells were harvested for RT-qPCR and Western blot analysis to assess the protein expression levels of CLTA, EDIL3, and other related markers.

For protein extraction, the cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (Thermo Fisher Scientific), supplemented with protease and phosphatase inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich). The protein concentration was determined using the BCA Protein Assay Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific), following the manufacturer’s instructions. Equal amounts of protein (30–50 µg) from each sample were separated by SDS-PAGE and transferred onto a PVDF membrane (Millipore). The transfer was conducted at 100 V for 1 h at 4 °C to ensure efficient protein transfer. After transfer, the membrane was blocked with 5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-T buffer (Tris-buffered saline with 0.1% Tween 20) for 1 h at room temperature to prevent non-specific binding. Following blocking, the membrane was incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies against CLTA, EDIL3, and other proteins of interest. The following primary antibodies were used: anti-CLTA (1:1000), anti-EDIL3 (1:1000), and anti-GAPDH (as a loading control, 1:5000) (all antibodies were purchased from Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Following the primary antibody incubation, the membrane was washed with TBS-T three times for 5 min each to remove excess primary antibody. The membrane was then incubated for 1 h at room temperature with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:5000). After secondary antibody incubation, the membrane was washed again with TBS-T three times for 5 min each. Protein bands were visualized using ECL detection reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific) on a ChemiDoc XRS + System (Bio-Rad). The relative protein expression levels were quantified using ImageJ software and normalized to the GAPDH control.

Cell proliferation assay

To evaluate the effects of CLTA and EDIL3 knockdown on TC cell growth, we performed a cell proliferation assay using the CellTiter 96® AQueous One Solution Cell Proliferation Assay (Promega). After transfection with miRNAs targeting CLTA and EDIL3, CAL62 and TPC1 cells were seeded into 96-well plates at a density of 5,000 cells per well. The cells were incubated at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. At 24, 48, and 72 h, 20 µL of CellTiter 96® AQueous reagent was added to each well, and the cells were incubated for 1 h. Absorbance at 490 nm was measured using a Microplate Reader (BioTek Instruments), and the data were analyzed to calculate the proliferation rate, expressed as a percentage of the control group.

Colony formation assay

To assess the clonogenic potential of CLTA and EDIL3 knockdown cells, we performed a colony formation assay. After transfection, CAL62 and TPC1 cells were plated in 6-well plates at a density of 1,000 cells per well. The cells were incubated for 2–3 weeks at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. During this period, colonies were allowed to form. After incubation, the cells were fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde and stained with crystal violet (Sigma-Aldrich) to visualize the colonies. The colonies were counted manually, and the results were expressed as the number of colonies per well.

Wound healing assay

To investigate the effect of CLTA and EDIL3 knockdown on cell migration, we performed a wound healing assay. After transfection with the miRNAs, CAL62 and TPC1 cells were seeded in 6-well plates and grown to confluence. A wound was created by scraping the monolayer with a sterile pipette tip. The cells were washed with PBS to remove debris and incubated in serum-free medium for 24 h at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 incubator. Images were captured at 0 and 24 h using a phase-contrast microscope (Olympus), and the percentage of wound closure was calculated by measuring the area of the wound at each time point.

Statistics

Statistical analysis for all experiments was performed using GraphPad Prism software (Version 9.0). A two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple comparisons test was used for analyzing differences in cell proliferation assays at various time points. For colony formation and wound healing assays, Student’s t-test was used to compare the number of colonies and wound closure between knockdown and control groups. Venn diagram and network centrality analysis were used to identify common DEGs and hub genes, with statistical significance set at an adjusted p-value (Padj) < 0.05 and LogFC |≥ 1|. ROC curve analysis and AUC values were calculated to assess the diagnostic potential of miRNAs and the effects of knockdown on protein expression levels were analyzed by Western blot using ImageJ software. Statistical significance was considered at P*-value < 0.05, P**-value < 0.01, and P***-value < 0.001.

Results

Data retrieval, analysis, and identification of hub genes in TC and HT

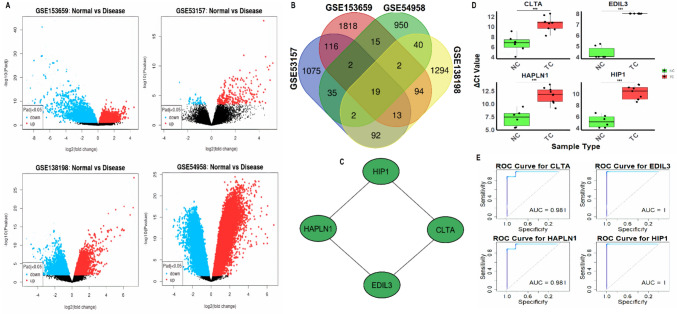

We analyzed datasets retrieved from the GEO database to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in TC and HT. Specifically, we used two TC datasets (GSE53157 and GSE153659) and two HT datasets (GSE54958 and GSE138198). The datasets were analyzed using the limma package to identify DEGs between normal and disease samples. The volcano plots in Fig. 1A illustrate the DEGs identified from each dataset, where the x-axis represents the log2 fold change and the y-axis represents the -log10 of the p-value. In each plot, genes with significant differential expression are highlighted, with red indicating upregulated genes and blue indicating downregulated genes, based on a threshold of adjusted p-value (Padj) < 0.05 (Fig. 1A). The volcano plots show that significant numbers of genes were differentially expressed in each dataset, with the most prominent differences observed in the TC datasets (GSE53157 and GSE153659) compared to the HT datasets (GSE54958 and GSE138198) (Fig. 1A). Next, the Venn diagram in Fig. 1B provides an overview of the top 2000 DEGs identified across all four datasets. Among these DEGs, 19 genes were shared between TC and HT, highlighting potential common molecular players in both diseases (Fig. 1B). Further analysis in Fig. 1C identified hub genes among the 23 common DEGs using the degree method, a network-based approach that calculates the centrality of genes based on their connections. The analysis revealed that CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 emerged as the most significant hub genes (Fig. 1C). The expression analysis of these hub genes across 10 TC and 6 normal control cell lines via RT-qPCR is shown in Fig. 1D. The results indicate a marked (P-value < 0.001) upregulation of CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 in TC cell lines compared to normal control cells. Finally, the ROC curves shown in Fig. 1E were generated based on RT-qPCR data to assess the diagnostic performance of these hub genes. The area under the curve (AUC) for CLTA and HAPLN1 was 0.981, and the AUC for EDIL3 and HIP1 was 1 (Fig. 1E), indicating excellent diagnostic accuracy.

Fig. 1.

Identification of differentially expressed genes and hub genes in TC and HT. A Volcano plots showing differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between normal and disease samples from the TC (GSE53157 and GSE153659) and HT (GSE54958 and GSE138198) datasets. B Venn diagram displaying the overlap of the top 2000 DEGs across all four datasets. C Network-based analysis using the degree method to identify the hub genes among the 23 common DEGs. D Expression analysis of CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 across 10 TC and 6 normal control cell lines via RT-qPCR. E ROC curve analysis based on RT-qPCR data to assess the diagnostic performance of the hub genes. P***-value < 0.001

Validation of hub gene expression and GSEA analysis

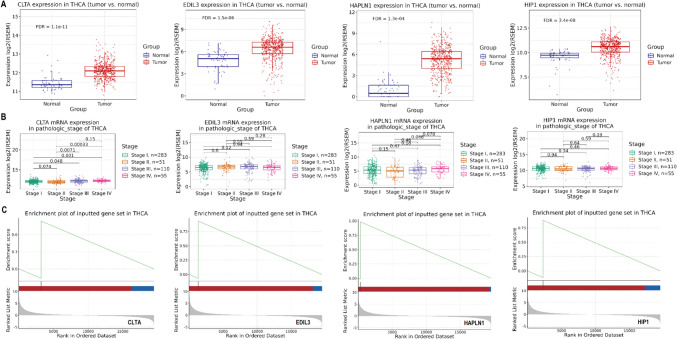

We validated the expression of CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 in the TCGA TC dataset using the GSCA database and conducted GSEA analysis. Figure 2A revealed significant (P-value < 0.05) upregulation of all four genes in tumor tissues compared to normal tissues, with CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 showing FDR values ranging from 1.1e-11 to 3.4e-08 (Fig. 2A). Figure 2B highlighted that CLTA, EDIL3, and HAPLN1 exhibited significant expression differences across TC stages, with advanced stages showing higher expression levels (Fig. 2B). Notably, HIP1 did not show significant variation across stages, indicating its consistent expression (Fig. 2B). Furthermore, GSEA analysis demonstrated that these genes were significantly (P-value < 0.05) associated with the development of TC (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 2.

Validation of hub gene expression and GSEA analysis. A Validation of CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 expression in the TCGA TC dataset using the GSCA database. B Expression analysis of CLTA, EDIL3, and HAPLN1 across different stages of TC. C GSEA analysis showing significant associations between the hub genes and the development of TC. P-value < 0.05

Promoter methylation analysis of hub genes

We analyzed the promoter methylation status and its correlation with gene expression of hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 in TC using the OncoDB and GSCA databases. Figure 3A shows that CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 exhibit differential methylation between tumor and normal tissues, with CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 showing significant (P-value < 0.05) decreased promoter methylation in tumor samples (Fig. 3A). Figure 3B further validated these findings using data from the GSCA database, with CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 showing significant (P-value < 0.05) hypomethylation in TC samples relative to normal controls (Fig. 3B). In Fig. 3C, Spearman correlation analysis via GSCA revealed negative correlations between expression and promoter methylation levels of the hub gens (Fig. 3C). These results highlight the potential role of methylation in regulating the expressions of CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 in TC.

Fig. 3.

Promoter methylation analysis of hub genes. A Promoter methylation status of CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 in TC compared to normal tissues via the OncoDB database. B Validation of the promoter methylation findings using the GSCA database. C Spearman correlation analysis using the GSCA database reveals negative correlations between gene expression and promoter methylation levels for CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1 in TC. P-value < 0.05

Mutational and CNV analysis of hub genes

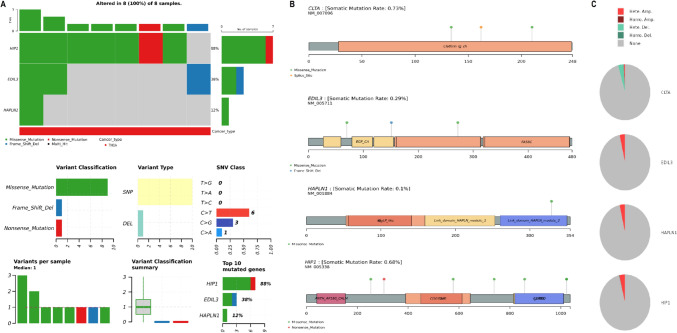

We analyzed the mutational and CNV data of the hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 in TC using the cBioPortal database. Figure 4A shows that HIP1 was mutated in 88% of the analyzed TC samples, primarily due to missense mutations, while EDIL3 and HAPLN1 showed mutations in 38% and 12% of the samples, respectively (Fig. 4A). CLTA exhibited a somatic mutation rate of 0.73%, with mutations primarily in the Clathrin_Ig_ch region (Fig. 4A, B). EDIL3 and HAPLN1 had mutation rates of 0.29% and 0.1%, respectively (Fig. 4A, B), with alterations in specific domains such as EGF_CA and Link_domain_HAPLN_module. HIP1 had a mutation rate of 0.68% with mutations concentrated in the ANTH_AP180_CALM and COG6 regions (Fig. 4A, B). Figure 4C showed CNV analysis, with CLTA and HIP1 exhibiting high amplification in tumor samples, suggesting potential overexpression, while EDIL3 and HAPLN1 displayed stable CNV profiles (Fig. 4C).

Fig. 4.

Mutational and CNV analysis of hub genes in TC. A Mutational analysis of CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 in TC using the cBioPortal database. B Zoomed-in view of mutation sites in the hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1, showing their mutation hotspots. C CNV analysis of CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 in TC samples

Meta-analysis of survival associations for hub genes

We conducted a meta-analysis to assess the survival associations of the hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 in TC using data from the GENT2 database. For CLTA, the overall hazard ratio (HR) from the meta-analysis was 1.02 (95%-CI: [0.78, 1.33]), indicating significant effect on survival with a p-value of 0.023 (Fig. 5A). For EDIL3, the pooled HR from the meta-analysis was 1.12 (95%-CI: [0.90, 1.41]), and it was statistically significant, with a p-value of 0.043 (Fig. 5B). This suggests that EDIL3 significantly influence survival outcomes in TC. In the case of HAPLN1, the pooled HR from the meta-analysis was 1.13 (95%-CI: [0.95, 1.35]), which was statistically significant with a p-value of 0.035 (Fig. 5C). This result suggests that higher expression of HAPLN1 is associated with worse survival in TC. Lastly, for HIP1, the pooled HR from the meta-analysis was 1.09 (95%-CI: [0.90, 1.32]), which was statistically significant (p-value = 0.035) (Fig. 5D). This suggests that HIP1 has a major impact on survival outcomes in thyroid cancer.

Fig. 5.

Meta-analysis of survival associations for hub genes in TC. A Meta-analysis of CLTA survival association in TC using the GENT2 database. B Meta-analysis of EDIL3 survival association in TC. C Meta-analysis of HAPLN1 survival association in TC. D Meta-analysis of HIP1 survival association in TC. P-value < 0.05

Correlation analysis of hub genes with immune regulation and drug sensitivity

In this part of the study, we examined the relationship between the hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 and various immune-related factors and drug sensitivity in TC using the TISIDB, GSCA, and GDSC databases. Figure 6A shows the correlation of the hub genes with immune inhibitor genes in TC and other cancers. Results highlighted that CLTA showed a positive correlation with immune inhibitors such as VTCN1, TGFBR1, and TGFB1, etc. (Fig. 6A). Similarly, EDIL3 exhibited positive correlations with TGFBR1, KDR, and CD274, etc. (Fig. 6A). HAPLN1 was positively correlated with KDR and IDO1, while HIP1 showed a positive correlation with TGFBR1 and CD274, etc. (Fig. 6A). Figure 6B presents the correlation between the hub genes and immune cell types in TC. CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 exhibit negative correlations with various immune cells, including CD4 + T cells, B cells, and Gamma_delta cells (Fig. 6B). This suggests that high expression of these genes is associated with reduced infiltration of these immune cells into the tumor microenvironment, potentially promoting immune evasion and tumor progression. Figure 6C shows the correlation between the expression of these hub genes and drug sensitivity in the GDSC database. Results highlighted significant association between high expression of the hub genes and resistance to several chemotherapy drugs. For instance, CLTA and EDIL3 were associated with resistance to Navitoclax, Tubastatin A, and BMS-754807, while HAPLN1 and HIP1 exhibited similar patterns of resistance to Navitoclax and Neratinib (Fig. 6C).

Fig. 6.

Correlation analysis of hub genes with immune regulation and drug sensitivity. A Correlation of CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 with immune inhibitors in TC and other cancers using the TISIDB database. B Correlation of hub genes with immune cell infiltration in TC using the GSCA database. C Correlation of hub gene expression with drug sensitivity using the GDSC database. P-value < 0.05

PPI network and gene enrichment analysis of hub genes

We analyzed the PPI networks of the hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 using the GeneMANIA and STRING databases, followed by gene set enrichment analysis using DAVID database. Figure 7A and Fig. 7B show the PPI networks for the hub genes, revealing extensive interactions with other proteins like FT57, HIP1R, ACAN, and AP2B1, suggesting that these hub genes play central roles in cellular functions such as adhesion, immune modulation, and cytoskeletal organization (Fig. 7A, B). Gene set enrichment analysis of hub genes and their associated binding partners in Figs. 7C–F highlighted key biological processes and pathways associated with the hub genes and their partners. Figure 7C showed enrichment in “coated pit, vesicle coat, and coated vesicle membrane, indicating involvement in endocytosis and vesicle trafficking.” Fig. 7D revealed enrichment in “clathrin binding and lipid binding, suggesting a role in vesicular trafficking and lipid metabolism.” Fig. 7E highlighted processes like post-synaptic neurotransmitter receptor internalization and synaptic endocytosis, implicating the hub genes in cellular communication and synaptic functions.” Fig. 7F identified the Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways like “SNARE interactions in vesicular transport and Rap1 signaling,” emphasizing the hub genes’ involvement in cancer cell migration, immune evasion, and vesicular transport.

Fig. 7.

PPI network and gene enrichment analysis of hub genes. A PPI network for the hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 constructed using the GeneMANIA. B PPI network for the hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 constructed using the STRING., C Cellular component enrichment analysis. D Molecular function enrichment analysis. E Biological process enrichment analysis. F Pathway enrichment analysis. P-value < 0.05

Regulatory miRNAs of hub genes

Herein, we explored the regulatory miRNAs targeting the hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 using TargetScan predictions and validated their expression through RT-qPCR in 10 TC and 6 normal control cell lines. Figure 8A shows that hsa-miR-142-3p, hsa-miR-137, hsa-miR-23c, and hsa-miR-19a-3p are predicted to regulate the hub genes with varying degrees of binding affinity (Fig. 8A). Figure 8B reveals that hsa-miR-142-3p, hsa-miR-137, hsa-miR-23c, and hsa-miR-19a-3p were significantly (P-value < 0.01) upregulated in TC cell lines, suggesting miRNA expression changes in TC. Figure 8C demonstrates high AUC values in the ROC curve analysis for all miRNAs, indicating strong potential for these miRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers in TC (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

Regulatory miRNAs of hub genes. A TargetScan predictions showing miRNAs that regulate the hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 with varying degrees of binding affinity. B RT-qPCR validation of miRNA expression in 10 TC cell lines and 6 normal control cell lines. C ROC curve analysis. P**-value < 0.01

CLTA and EDIL3 knockdown and functional assays

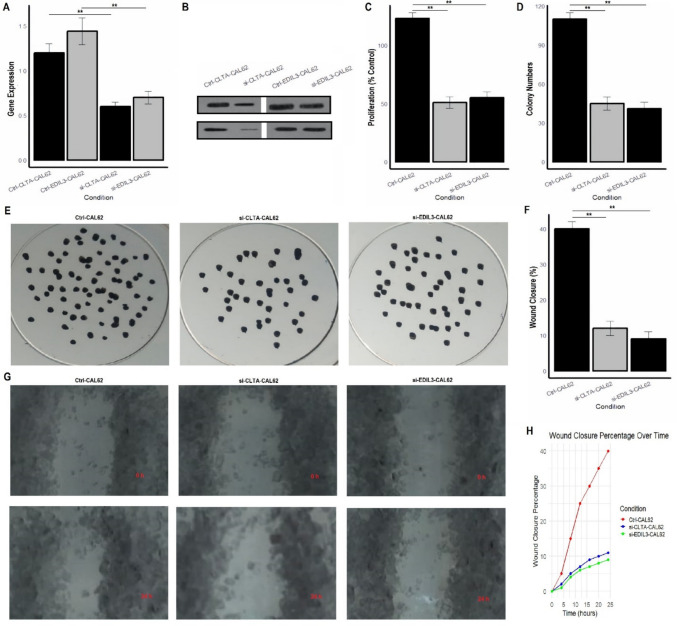

Next, we investigated the functional roles of CLTA and EDIL3 in TC by performing knockdown experiments in the CAL62 and TPC1 cell lines. Gene expression analysis via RT-qPCR and Western blot assays confirmed the successful knockdown of CLTA and EDIL3 in both the CAL62 and TPC1 cell lines, as shown in Figs. 9A, B and 10A, B and supplementary data Fig. 1, where the gene expression of both hub genes was significantly (P-value < 0.01) reduced in the siRNA-treated cells compared to the control. The proliferation assays indicated a significant (P-value < 0.01) decrease in cell proliferation in both the si-CLTA and si-EDIL3 cells when compared to the control (Figs. 9C and 10C). These findings suggest that CLTA and EDIL3 are involved in promoting cell growth in thyroid cancer cells, and their knockdown impairs this process. In colony formation assays (Figs. 9D, E and 10D, E), the number of colonies formed by si-CLTA and si-EDIL3 cells was significantly reduced compared to the control cells, indicating that these genes are essential for maintaining the clonogenic potential of thyroid cancer cells. This highlights their role in cellular proliferation and survival in a 3D environment, which mimics aspects of tumor growth. The wound healing assays (Figs. 9F, G and 10F, G) revealed that both si-CLTA and si-EDIL3 cells had significantly reduced wound closure percentages compared to control cells, suggesting that these genes are crucial for cell migration. This was further confirmed by the time-lapse analysis of wound closure (Figs. 9H and 10H), where the knockdown of CLTA and EDIL3 resulted in delayed wound closure, emphasizing the role of these genes in promoting migration and invasion in thyroid cancer cells.

Fig. 9.

CLTA and EDIL3 knockdown and functional assays in CAL62 cells. A RT-qPCR analysis confirming the successful knockdown of CLTA in CAL62 cells using siRNA. B Western blot analysis confirming the reduced protein expression of CLTA in CAL62 cells after siRNA treatment. C Cell proliferation assay showing a significant decrease in cell proliferation in si-CLTA and si-EDIL3 cells compared to control cells. D Colony formation assay demonstrating that si-CLTA and si-EDIL3 cells formed significantly fewer colonies compared to control cells. F Wound healing assay showing significantly reduced wound closure in si-CLTA and si-EDIL3 cells compared to control cells. G Time-lapse analysis of wound healing showing delayed wound closure in si-CLTA and si-EDIL3 cells. P**-value < 0.01

Fig. 10.

CLTA and EDIL3 knockdown and functional assays in TPC1 cells. A RT-qPCR analysis confirming the successful knockdown of CLTA in TPC1 cells using siRNA. B Western blot analysis confirming the reduced protein expression of CLTA in TPC1 cells after siRNA treatment. C Cell proliferation assay showing a significant decrease in cell proliferation in si-CLTA and si-EDIL3 cells compared to control cells. D Colony formation assay demonstrating that si-CLTA and si-EDIL3 cells formed significantly fewer colonies compared to control cells. F Wound healing assay showing significantly reduced wound closure in si-CLTA and si-EDIL3 cells compared to control cells. G Time-lapse analysis of wound healing showing delayed wound closure in si-CLTA and si-EDIL3 cells, further confirming that the knockdown of these genes results in impaired migration and invasion of TPC1 thyroid cancer cells. P**-value < 0.01

Activation of the Rap1 signaling pathway by CLTA and EDIL3 in TC

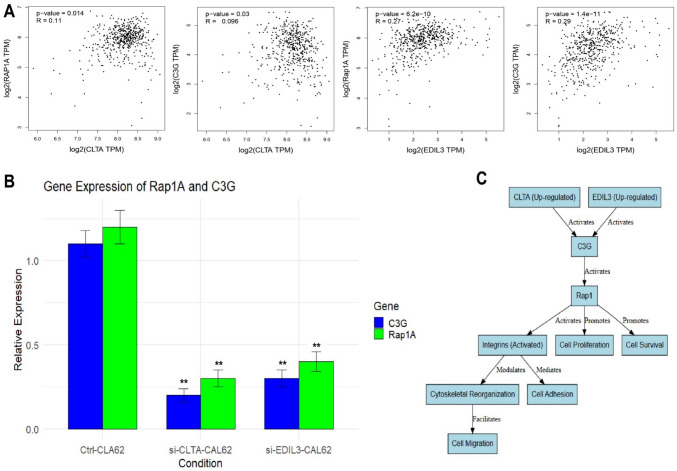

KEGG pathway enrichment analysis results showed that CLTA and EDIL3 are involved in the activation of the Rap1 signaling pathway. Therefore, next, we analyzed the correlation of these genes with two key activators (Rap1A and C3G) of the Rap1 signaling pathway to confirm this involvement. Figure 11A presents the correlation analysis between CLTA and EDIL3 with the activators Rap1A and C3G in TC using the GEPIA2 database. The analysis shows a significant positive correlation between CLTA and Rap1A (p-value = 0.014, R = 0.11), as well as CLTA and C3G (p-value = 0.03, R = 0.96), indicating that CLTA may influence the expression of these key activators of the Rap1 pathway. Similarly, EDIL3 exhibits a stronger positive correlation with both Rap1A (p-value = 6.2e-10, R = 0.27) and C3G (p-value = 1.4e-11, R = 0.29), further supporting the idea that EDIL3 plays an important role in activating the Rap1 signaling pathway in thyroid cancer. Next, Fig. 11B shows the RT-qPCR analysis of the expression of Rap1A and C3G in Ctrl and siRNA-treated (si-CLTA and si-EDIL3) CAL62 cells. The results confirm that the knockdown of both CLTA and EDIL3 significantly reduces the expression of Rap1A and C3G compared to control cells (Fig. 11B), indicating that both CLTA and EDIL3 are involved in activating Rap1A and C3G, which are crucial for the Rap1 signaling pathway in TC cells. Lastly, Fig. 11C illustrates the crosstalk between CLTA and EDIL3 in activating the Rap1 signaling pathway. Both genes are shown to activate C3G, which in turn activates Rap1A. Activated Rap1 regulates multiple cellular processes, including integrin activation, cytoskeletal reorganization, cell adhesion, cell proliferation, and cell migration (Fig. 11C).

Fig. 11.

Activation of the Rap1 signaling pathway by CLTA and EDIL3 in TC. A Correlation analysis between CLTA and EDIL3 with the activators Rap1A and C3G in TC using the GEPIA2 database. B RT-qPCR analysis of the expression of Rap1A and C3G in Ctrl and siRNA-treated (si-CLTA and si-EDIL3) CAL62 cells. C Crosstalk between CLTA and EDIL3 in activating the Rap1 signaling pathway. P**-value < 0.01

Discussion

Hashimoto's thyroiditis (HT) is an autoimmune disorder that causes chronic inflammation of the thyroid gland and is one of the most common causes of hypothyroidism [38, 39]. It is often associated with the development of thyroid cancer (TC), with a number of studies suggesting that patients with HT may have an increased risk of developing TC [13, 40, 41]. However, the molecular mechanisms linking HT to TC remain poorly understood, and the identification of biomarkers that can distinguish between these two conditions, while also serving as diagnostic and prognostic indicators for TC, is an area of critical importance [42, 43]. While various biomarkers have been investigated in both HT and TC [13, 40], there is a lack of comprehensive studies that compare these two conditions to identify common molecular alterations and shared hub genes [44].

Our study addresses this gap by performing an integrated analysis of multiple datasets to identify DEGs common between TC and HT, using data from the GEO database [45]. We identified different hub genes—CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1—that are significantly differentially expressed in both TC and HT. These genes may not only serve as potential diagnostic biomarkers but also help in understanding the molecular mechanisms underlying both conditions, providing insight into their shared and distinct pathways.

Previous studies have explored individual gene alterations in TC and HT, often focusing on their separate pathophysiological mechanisms [46, 47]. Alterations in genes such as CLTA, EDIL3, and HIP1 have been implicated in a variety of cancers, with these genes known to play significant roles in cellular trafficking, immune modulation, and tumor progression [48]. For example, CLTA is involved in the endocytosis of cell surface receptors, which affects cancer cell adhesion and migration [48], while EDIL3 is known to regulate angiogenesis and cell survival, both crucial for tumor growth and metastasis [49]. HIP1 has been linked to vesicular trafficking and signaling in cancer cell migration and invasion [50].

While these studies have identified the individual roles of these genes in various cancers, the novelty of our study lies in its comparative approach between TC and HT, where we identify CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 as common hub genes. Unlike previous studies, which have largely focused on the tumor-specific expression of these genes, our study highlights their role in both the autoimmune context of HT and the malignancy of TC, suggesting that these genes may act as molecular players that bridge the inflammatory processes of HT and the progression of TC. The identification of these common markers is a unique aspect of our research, as it brings together the molecular understanding of HT as an autoimmune thyroid disease and TC as a cancerous condition, shedding light on their potential shared pathways and mechanisms. Moreover, the significant increase in gene expression levels of CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 in TC cell lines, particularly when compared to normal thyroid cells, along with the strong diagnostic performance evidenced by high AUC values in ROC curve analyses, is a novel contribution to the field.

Additionally, while studies have examined promoter methylation in cancer and autoimmune diseases [51–55], our analysis of hypomethylation in the promoters of these hub genes in TC provides novel insight into their potential epigenetic regulation. These findings suggest that DNA methylation could be a key mechanism driving the expression of these genes in both conditions, which has not been widely explored in the context of HT and its association with TC.

The functional roles of the hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 in tumor progression, immune modulation, and cell migration have been well-documented in various cancers [48, 56–58], and our study builds upon this existing knowledge by providing new insights into how these genes may contribute to both the inflammatory processes in HT and the malignant transformation in TC. Previous research has suggested that alterations in the expression of these genes promote immune evasion, tumor progression, and metastasis [59]. For instance, CLTA has been linked to immune cell trafficking and cellular adhesion in cancer [59], EDIL3 has been associated with angiogenesis and immune modulation [49], and HIP1 and HAPLN1 have been shown to influence cancer cell migration and invasion [60]. However, these findings were typically isolated to specific cancers and did not explore the dual role of these genes in both autoimmune and cancerous thyroid conditions. We further demonstrated that the upregulation of these hub genes is associated with negative correlations with various immune cell types in the tumor microenvironment, indicating that these genes may play a critical role in immune suppression. In TC, this immune evasion may contribute to the tumor’s ability to avoid immune surveillance, potentially facilitating the transition from inflammation to malignancy [61].

The KEGG pathway analysis further distinguishes our study by showing that CLTA and EDIL3 are associated with the Rap1 signaling pathway, which plays a crucial role in cellular adhesion, migration, and immune modulation. While these associations suggest potential involvement in TC progression and the inflammatory processes characteristic of HT, the current evidence primarily consists of expression data obtained via the RT-qPCR analysis. These results alone are insufficient to conclusively demonstrate their functional involvement through the Rap1 signaling pathway. Therefore, further experimental validation, such as functional assays to examine the downstream effects of Rap1A/C3G in this context, is required to confirm these interactions. At this stage, while the associations identified in this study provide a basis for further investigation, it is important to note that the interpretation of these relationships mainly remains speculative. Further experimental work will be essential to confirm the functional relevance of Rap1 signaling in TC progression and its potential role in the inflammatory processes associated with HT.

Concerning the clinical diagnostic significance of this study, the identification of hub genes such as CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1, which are upregulated in TC and HT and could serve as potential biomarkers for early diagnosis and improved patient management. The concurrent diagnosis of TC and HT is essential because the presence of HT may influence the molecular landscape of TC, as evidenced by the shared differentially expressed genes between both diseases. Identifying these common molecular players could enhance diagnostic accuracy, especially in cases where TC may be masked or exacerbated by the underlying inflammation in HT. Furthermore, distinguishing between HT patients with normal and abnormal thyroid function could refine the diagnostic approach, as patients with abnormal thyroid function may exhibit more aggressive disease features or higher risk for progression to TC. This differentiation could lead to more personalized treatment plans, where patients with abnormal thyroid function might require closer monitoring or early intervention, improving patient outcomes and ensuring more effective management of both HT and TC.

While this study provides valuable insights into the potential roles of hub genes CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1 in TC and HT, there are several limitations that need to be addressed. First, this study relies heavily on datasets from public repositories and cell-line-based models, which may not fully replicate the complexity and heterogeneity of human tumors in vivo. Additionally, all the datasets used in this study contain TC samples in general without differentiating between subtypes such as PTC, FTC, MTC, and ATC. These subtypes have distinct molecular and cellular origins, which could influence their interaction with HT, and this heterogeneity has not been fully explored in our analysis. Furthermore, the mutational and CNV data provided are based on TC samples, but the heterogeneity of these mutations and their potential interactions with other genetic or environmental factors need to be explored in more detail. Additionally, while miRNA regulatory analyses suggest a possible mechanism for gene regulation, these findings need experimental validation through in vivo studies to assess the role of miRNAs in modulating gene expression. Lastly, clinical sample-based validation is crucial to confirm the relevance of these findings in the context of patient-derived tissues. Future studies should focus on incorporating clinical samples to further validate the expression patterns of hub genes and their potential as diagnostic biomarkers. Additionally, comprehensive in vivo validation and functional assays are needed to confirm the biological relevance of these genes in the progression of TC and HT, including the exploration of potential differences between TC subtypes.

Conclusion

In conclusion, our study provides a comprehensive molecular analysis of shared biomarkers between Hashimoto's thyroiditis and thyroid cancer. By identifying common hub genes, CLTA, EDIL3, HAPLN1, and HIP1, we shed light on the molecular mechanisms that underlie the connection between these two diseases. The diagnostic and prognostic potential of these genes, combined with their role in immune regulation and drug resistance, offers new avenues for targeted therapies and early detection strategies. Our findings provide a foundation for future research aimed at developing clinical tools that can differentiate between HT and TC, ultimately improving patient outcomes by enabling more precise diagnosis and personalized treatments.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Tianyu Liu contributed to the conceptualization and design of the study, data analysis, and manuscript drafting. Dechun Zhang assisted with data analysis and interpretation. Wen Ouyang contributed to the acquisition and processing of experimental data. Rongfang Li provided critical revisions to the manuscript and contributed to the final analysis of results. Siying Wang contributed to the methodology and experimental design. Weixuan Liu (corresponding author) supervised the study, provided guidance on the analysis, and led the manuscript writing and final revisions. All authors reviewed and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

None to declare.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets analyzed during this study are publicly available in the GEO database. The GSE53157 and GSE153659 datasets for TC can be accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc = GSE53157 and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc = GSE153659, respectively. The GSE54958 and GSE138198 datasets for HT are available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc = GSE54958 and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc = GSE138198, respectively. Additional data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Additional data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

Ethical approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.dos Santos Valsecchi VA, Betoni FR, Ward LS, Cunha LL. Clinical and molecular impact of concurrent thyroid autoimmune disease and thyroid cancer: From the bench to bedside. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2024;25(1):5–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vargas-Uricoechea H. Molecular mechanisms in autoimmune thyroid disease. Cells. 2023;12(6):918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tywanek E, Michalak A, Świrska J, Zwolak A. Autoimmunity, new potential biomarkers and the thyroid gland—the perspective of hashimoto’s thyroiditis and its treatment. Int J Mol Sci. 2024;25(9):4703. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhang QY, Wang Q, Fu JX, Xu XX, Guo DS, Pan YC, et al. Multi targeted therapy for alzheimer’s disease by guanidinium-modified calixarene and cyclodextrin co-assembly loaded with insulin. ACS Nano. 2024;18(48):33032–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kotak PS, Kadam A, Acharya S, Kumar S, Varma A. Beyond the thyroid: a narrative review of extra-thyroidal manifestations in hashimoto’s disease. Cureus. 2024. 10.7759/cureus.71126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saharti S. The diagnostic value of add-on thyroid cell block in the evaluation of thyroid lesions. CytoJournal. 2023;20:3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Abdelmoula NB, Abdelmoula B, Masmoudi I, Aloulou S. Review Histopathological-molecular classifications of papillary thyroid cancers: Challenges in genetic practice settings. Biomed Healthc Res. 2024;2(1):2–11. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hu X, Chen Y, Shen Y, Tian R, Sheng Y, Que H. Global prevalence and epidemiological trends of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis in adults: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health. 2022;10:1020709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ralli M, Angeletti D, Fiore M, D’Aguanno V, Lambiase A, Artico M, et al. Hashimoto’s thyroiditis: an update on pathogenic mechanisms, diagnostic protocols, therapeutic strategies, and potential malignant transformation. Autoimmun Rev. 2020;19(10): 102649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hu S, Rayman MP. Multiple nutritional factors and the risk of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis. Thyroid. 2017;27(5):597–610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qin W, Lin J, Luo H, Yu L. The burden of thyroid cancer is associated with the level of national development in Asia: Evidence from 1990–2021 for 47 countries. 2025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Dogra V, Suresh DVH, Achyuth S, Huggine V, Reddy PN, Kotagiri U, editors. DeepThyroid: Advanced Thyroid Cancer Severity Detection with CNN-Based Deep Learning. 2024 Second International Conference on Advances in Information Technology (ICAIT); 2024: IEEE.

- 13.Azizi G, Keller J, Lewis M, Piper K, Puett D, Rivenbark K, et al. Association of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis with thyroid cancer. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2014;21(6):845–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Subhi O, Schulten H-J, Bagatian N, Ra A-D, Karim S, Bakhashab S, et al. Genetic relationship between Hashimotos thyroiditis and papillary thyroid carcinoma with coexisting Hashimotos thyroiditis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15(6): e0234566. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Felicetti F, Catalano MG, Fortunati N. Thyroid autoimmunity and cancer. Endocr Immunol. 2017;48:97–109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Clough E, Barrett T. The gene expression omnibus database. Statistical Genomics: Methods and Protocols. 2016:93-110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Zeng Q, Jiang T, Wang J. Role of LMO7 in cancer. Oncol Rep. 2024;52(3):1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Jacobson EM, Tomer Y. The CD40, CTLA-4, thyroglobulin, TSH receptor, and PTPN22 gene quintet and its contribution to thyroid autoimmunity: back to the future. J Autoimmun. 2007;28(2–3):85–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mahin NM. A review on association of genetic polymorphism with thyroid hormone level leading to different diseases: Brac University; 2024.

- 20.Prete A, Borges de Souza P, Censi S, Muzza M, Nucci N, Sponziello M. Update on fundamental mechanisms of thyroid cancer. Front Endocrinol. 2020;11:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Nikiforov YE. Thyroid carcinoma: molecular pathways and therapeutic targets. Mod Pathol. 2008;21:S37–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lin Y, Li H, Zheng S, Han R, Wu K, Tang S, et al. Elucidating tobacco smoke-induced craniofacial deformities: biomarker and MAPK signaling dysregulation unraveled by cross-species multi-omics analysis. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf. 2024;288: 117343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ferrari SM, Fallahi P, Galdiero MR, Ruffilli I, Elia G, Ragusa F, et al. Immune and inflammatory cells in thyroid cancer microenvironment. Int J Mol Sci. 2019;20(18):4413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Qian F-C, Zhou L-W, Li Y-Y, Yu Z-M, Li L-D, Wang Y-Z, et al. SEanalysis 2.0: a comprehensive super-enhancer regulatory network analysis tool for human and mouse. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023;51(W1):W520–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zheng P, Xu D, Cai Y, Zhu L, Xiao Q, Peng W, et al. A multi-omic analysis reveals that Gamabufotalin exerts anti-hepatocellular carcinoma effects by regulating amino acid metabolism through targeting STAMBPL1. Phytomedicine. 2024;135: 156094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Li X, Liang J, Hu J, Ma L, Yang J, Zhang A, et al. Screening for primary aldosteronism on and off interfering medications. Endocrine. 2024;83(1):178–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li Z, Fan J, Xiao Y, Wang W, Zhen C, Pan J, et al. Essential role of Dhx16-mediated ribosome assembly in maintenance of hematopoietic stem cells. Leukemia. 2024;38(12):2699–708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mering CV, Huynen M, Jaeggi D, Schmidt S, Bork P, Snel B. STRING: a database of predicted functional associations between proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(1):258–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Liu CJ, Hu FF, Xie GY, Miao YR, Li XW, Zeng Y, et al. GSCA: an integrated platform for gene set cancer analysis at genomic, pharmacogenomic and immunogenomic levels. Brief Bioinform. 2023. 10.1093/bib/bbac558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Tang G, Cho M, Wang X. OncoDB: an interactive online database for analysis of gene expression and viral infection in cancer. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022;50(D1):D1334–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cerami E, Gao J, Dogrusoz U, Gross BE, Sumer SO, Aksoy BA, et al. The cBio cancer genomics portal: an open platform for exploring multidimensional cancer genomics data. Cancer Discov. 2012;2(5):401–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Park S-J, Yoon B-H, Kim S-K, Kim S-Y. GENT2: an updated gene expression database for normal and tumor tissues. BMC Med Genom. 2019;12:1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ru B, Wong CN, Tong Y, Zhong JY, Zhong SSW, Wu WC, et al. TISIDB: an integrated repository portal for tumor-immune system interactions. Bioinformatics. 2019;35(20):4200–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Montojo J, Zuberi K, Rodriguez H, Bader GD, Morris Q. GeneMANIA: Fast gene network construction and function prediction for Cytoscape. F1000Research. 2014. 10.12688/f1000research.4572.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Dennis G, Sherman BT, Hosack DA, Yang J, Gao W, Lane HC, et al. DAVID: database for annotation, visualization, and integrated discovery. Genome Biol. 2003;4:1–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Agarwal V, Bell GW, Nam JW, Bartel DP. Predicting effective microRNA target sites in mammalian mRNAs. Elife. 2015;12(4):05005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tang Z, Kang B, Li C, Chen T, Zhang Z. GEPIA2: an enhanced web server for large-scale expression profiling and interactive analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019;47(W1):W556–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Klubo-Gwiezdzinska J, Wartofsky L. Hashimoto thyroiditis: an evidence-based guide to etiology, diagnosis and treatment. Polish Arch Intern Med. 2022. 10.20452/pamw.16222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ragusa F, Fallahi P, Elia G, Gonnella D, Paparo SR, Giusti C, et al. Hashimotos’ thyroiditis: epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinic and therapy. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;33(6): 101367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lopes NMD, Lens HHM, Armani A, Marinello PC, Cecchini AL. Thyroid cancer and thyroid autoimmune disease: a review of molecular aspects and clinical outcomes. Pathol-Res Pract. 2020;216(9): 153098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Abdel-Maksoud MA, Ullah S, Nadeem A, Shaikh A, Zia MK, Zakri AM, et al. Unlocking the diagnostic, prognostic roles, and immune implications of BAX gene expression in pan-cancer analysis. Am J Transl Res. 2024;16(1):63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang L, Irshad S, Sultana U, Ali S, Jamil A, Zubair A, et al. Pan-cancer analysis of HS6ST2: associations with prognosis, tumor immunity, and drug resistance. Am J Transl Res. 2024;16(3):873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Hameed Y. Decoding the significant diagnostic and prognostic importance of maternal embryonic leucine zipper kinase in human cancers through deep integrative analyses. J Cancer Res Ther. 2023;19(7):1852–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hameed Y, Ejaz S. Integrative analysis of multi-omics data highlighted TP53 as a potential diagnostic and prognostic biomarker of survival in breast invasive carcinoma patients. Comput Biol Chem. 2021;92: 107457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bin T, Tang J, Lu B, Xu X-J, Lin C, Wang Y. Construction of AML prognostic model with CYP2E1 and GALNT12 biomarkers based on golgi-associated genes. Ann Hematol. 2024. 10.1007/s00277-024-06119-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Cao D-F, Zhou X-Y, Guo Q, Xiang M-Y, Bao M-H, He B-S, et al. Unveiling the role of histone deacetylases in neurological diseases: focus on epilepsy. Biomark Res. 2024;12(1):142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cao Z, Zhu J, Wang Z, Peng Y, Zeng L. Comprehensive pan-cancer analysis reveals ENC1 as a promising prognostic biomarker for tumor microenvironment and therapeutic responses. Sci Rep. 2024;14(1):25331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Xu Y, Yao Y, Yu L, Zhang X, Mao X, Tey SK, et al. Clathrin light chain A-enriched small extracellular vesicles remodel microvascular niche to induce hepatocellular carcinoma metastasis. J Extracell Vesicles. 2023;12(8):12359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tabasum S, Thapa D, Giobbie-Hurder A, Weirather JL, Campisi M, Schol PJ, et al. EDIL3 as an angiogenic target of immune exclusion following checkpoint blockade. Cancer Immunol Res. 2023;11(11):1493–507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hsu C-Y, Lin C-H, Jan Y-H, Su C-Y, Yao Y-C, Cheng H-C, et al. Huntingtin-interacting protein-1 is an early-stage prognostic biomarker of lung adenocarcinoma and suppresses metastasis via akt-mediated epithelial–mesenchymal transition. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2016;193(8):869–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Richardson BC. Role of DNA methylation in the regulation of cell function: autoimmunity, aging and cancer. J Nutr. 2002;132(8):2401S-S2405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Richardson B. DNA methylation and autoimmune disease. Clin Immunol. 2003;109(1):72–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Luo P, Guo Y, He Y, Wang C. Clinical characteristics, treatment and outcome of pembrolizumab-induced acute pancreatitis. Invest New Drugs. 2024;42(4):369–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Jiang F, Ahmad S, Kanwal S, Hameed Y, Tang Q. Key wound healing genes as diagnostic biomarkers and therapeutic targets in uterine corpus endometrial carcinoma: an integrated in silico and in vitro study. Hereditas. 2025;162(1):5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Sial N, Ahmad M, Hussain MS, Iqbal MJ, Hameed Y, Khan M, et al. CTHRC1 expression is a novel shared diagnostic and prognostic biomarker of survival in six different human cancer subtypes. Sci Rep. 2021;11(1):19873. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Jiang S-H, Wang Y, Yang J-Y, Li J, Feng M-X, Wang Y-H, et al. Overexpressed EDIL3 predicts poor prognosis and promotes anchorage-independent tumor growth in human pancreatic cancer. Oncotarget. 2015;7(4):4226. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zhang T, Li X, He Y, Wang Y, Shen J, Wang S, et al. Cancer-associated fibroblasts-derived HAPLN1 promotes tumour invasion through extracellular matrix remodeling in gastric cancer. Gastric Cancer. 2022. 10.1007/s10120-021-01259-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sun Y, Zhou Y, Xia J, Wen M, Wang X, Zhang J, et al. Abnormally high HIP1 expression is associated with metastatic behaviors and poor prognosis in ESCC. Oncol Lett. 2021;21(2):1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Huang H, Huo Z, Jiao J, Ji W, Huang J, Bian Z, et al. HOXC6 impacts epithelial-mesenchymal transition and the immune microenvironment through gene transcription in gliomas. Cancer Cell Int. 2022;22(1):170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.He A, Liu L, Ning Y, Wen Y, Li P, Cheng B, et al. Genome-Wide DNA methylation profile analysis identified Runx2 and CSGALNACT1 involved in the development of osteonecrosis of the femoral head. SSRN J. 2019. 10.2139/ssrn.3449376. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Yuan L, Zhou P, Liu W, Jiang L, Xia M, Zhao Y. Midkine promotes thyroid cancer cell migration and invasion by activating the phosphatidylinositol 3 kinase/protein kinase B/mammalian target of rapamycin pathway. CytoJournal. 2024;21:41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analyzed during this study are publicly available in the GEO database. The GSE53157 and GSE153659 datasets for TC can be accessed at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc = GSE53157 and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc = GSE153659, respectively. The GSE54958 and GSE138198 datasets for HT are available at https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc = GSE54958 and https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/query/acc.cgi?acc = GSE138198, respectively. Additional data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Additional data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.