Abstract

Purpose

This study’s primary aim was to investigate whether including a mental health component to healthy lifestyle interventions are associated with greater effects on quality of life (QoL) for post-treatment cancer survivors than addressing physical activity and/or nutrition alone.

Methods

PsycINFO, Scopus, Medline, CINAHL, and Google Scholar were searched to identify randomised control trials of healthy lifestyle interventions for post-treatment cancer survivors, with a usual care or waitlist control, and measured QoL. Meta-analyses quantified the effects of interventions vs controls at post-treatment on total QoL, physical, emotional, and social well-being. Subgroup analyses compared interventions with vs without a mental health component, modes of delivery, and duration. The quality of the included studies was assessed using the Cochrane Risk of Bias 2.

Results

Eighty-eight papers evaluating 110 interventions were included: 66 effect sizes were extracted for meta-analysis, and 22 papers were narratively synthesised. The pooled effect size demonstrated a small, significant effect of healthy lifestyle interventions in comparison to control for all QoL outcomes (total g = 0.32, p >.001; physical g = 0.19, p = 0.05; emotional g = 0.20, p >.001; social g = 0.18, p = 0.01). There was no significant difference between interventions with vs without a mental health component. Face-to-face delivered interventions were associated with greater total QoL and physical well-being compared to other modalities. Interventions delivered ≤12 weeks were associated with greater physical well-being than those delivered ≥13 weeks. Overall, studies had substantial levels of heterogeneity and 55.9% demonstrated high risk of bias.

Conclusions

Participating in a healthy lifestyle intervention following cancer treatment improves QoL. Few trials addressed mental health or evaluated online or telephone modalities; future research should develop and evaluate interventions that utilise these features.

Implications for Cancer Survivors

Brief healthy lifestyle interventions can be recommended for cancer survivors, particularly those interested in improving physical well-being.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s11764-023-01514-x.

Keywords: Cancer survivors, Lifestyle intervention, Quality of life, Complex interventions

Introduction

Advances in earlier detection and diagnosis, improved treatment options, and better supportive care are contributing to the growing cancer survivor population [1]. However, the physical (e.g. fatigue, pain, nausea, and changes in appearance) and psychosocial (e.g. psychological distress, challenges in relationships, financial stress, and changes in cognitive and sexual functioning) side effects of a cancer diagnosis and its associated treatments can significantly impact an individual’s quality of life (QoL) long after they have completed treatment [2–4]. QoL for cancer survivors is a subjective multi-dimensional concept that encompasses and measures various aspects of a person’s physical, emotional, social, and spiritual well-being, and functional status. QoL refers to how a person perceives their life in the context of their health and personal values, and how well they can function and participate in activities that are important to them [5–7].

Healthy lifestyle interventions addressing physical activity, nutrition, and/or weight management have been posited as one strategy to improve QoL and support cancer survivors following the completion of treatment. Such interventions have demonstrated efficacy in (a) reducing treatment-related side effects, cancer recurrence and mortality [8], and (b) improving emotional well-being [9]. Several meta-analyses have evaluated the efficacy of healthy lifestyle interventions in enhancing QoL in cancer survivors, but their results have been inconsistent. Small to moderate positive effects on QoL have been demonstrated across meta-analyses involving physical activity interventions involving all cancer types [7] and breast cancer survivors [9–11]. Similarly, healthy lifestyle education programs have demonstrated a moderate positive effect on lung cancer survivors QoL [12]. In contrast, meta-analyses which have investigated healthy lifestyle interventions for gynaecological cancers [13] or have only involved nutritional therapy [14] have not demonstrated significant differences to usual care control groups. Two meta-analyses investigating telehealth interventions [15, 16], such as those delivered via telephone, or videoconferencing and online platforms, have produced contrasting findings. Larson and colleagues [15] conducted a meta-analysis involving eleven studies and initially obtained a large positive effect; however, the magnitude of the effect was decreased to non-significant when two large studies contributing to heterogeneity were removed. In comparison, the second, and larger, meta-analysis by Li and colleagues [16] involving 28 studies found a small positive effect for telehealth interventions on cancer survivors’ QoL.

Although these meta-analyses support the implementation of healthy lifestyle interventions following cancer treatment, they have primarily focused on interventions which target physical health behaviours, such as physical activity and diet quality. However, a qualitative study conducted by Grant and colleagues [17] with cancer survivors, oncology healthcare professionals, and representatives from cancer support organisations identified that a healthy lifestyle after cancer treatment includes both physical health and mental health. The participants of this study recommended that a mental health component be included in healthy lifestyle interventions. Addressing mental health within healthy lifestyle interventions is also promoted by research investigating barriers to physical activity and healthy eating, which have identified stress as a prevalent barrier to engaging in these health behaviours [18, 19].

Thus, interventions targeting a healthy lifestyle after cancer treatment should go beyond physical activity and nutrition and address mental health as well. To date, meta-analyses have not examined whether interventions that include a mental health component increase the impact of healthy lifestyle interventions on cancer survivors’ QoL. The current meta-analysis aims to update the previous evidence for the efficacy of healthy lifestyle interventions on QoL post-intervention and to investigate whether interventions which include a mental health component in their intervention protocol are associated with greater effects on QoL in comparison to interventions which only address physical activity or nutrition. The secondary aim of this meta-analysis is to investigate whether other aspects of the intervention, such as mode of delivery (individual, group, telephone, online, or print) or duration (shorter vs longer), affect the association between the interventions and QoL.

Method

This meta-analysis followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) statement [20] and was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (CRD42021273722).

Study selection

To identify relevant studies, a review of electronic databases relevant to psychology and health, including PsycINFO, Scopus, Medline, and CINAHL, was conducted. In addition, the first 200 references identified in Google scholar were included in the review. The search strategy was based on the PICO approach, as follows: population—terms related to (1) cancer, and (2) survivor; intervention—terms related to (1) healthy lifestyle, (2) physical activity, (3) nutrition, and (4) weight control; outcome—terms related to QoL (see Multimedia A for details). The final database search was conducted on the 9th of June 2022.

Articles were included in the analysis if they meet the following criteria: (1) involved adult cancer survivors (i.e. ≥18 years and have completed active treatment); (2) offered an intervention targeting health behaviour change (i.e. physical activity, sedentary time, or diet, or weight management); (3) reported an outcome measure for total QoL, and/or Physical, Emotional, or Social Well-being on a reliable and valid measure of QoL (e.g. European Organization for the Research and Treatment of Cancer Quality of Life Questionnaire (EORTC QLQ-C30; [6]), Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy-General (FACT-G; [5]), or 36- or 12-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36; [21], SF-12; [22]); (4) involved a randomised control trial or pilot randomised control trial using a waitlist or usual care control (i.e. access to publicly available materials); (5) written in English and published in a peer-reviewed journal. Included articles investigated interventions utilising any mode of delivery. Articles were excluded if they involved a population other than adult cancer survivors, did not offer an intervention targeting health behaviour change, offered an intervention which only targeted mental health, did not measure QoL, or utilised any of the following designs: crossover design, single group pre-post, qualitative, cross-sectional design, protocol paper, systematic review, or meta-analysis. Articles were also excluded if they were grey literature (e.g. dissertations or conference papers).

Authors ML and CG conducted preliminary screening of titles and abstracts. Abstracts meeting inclusion criteria were subject to full-text evaluation. Disagreement between the two reviewers were resolved through discussion. If consensus was not achieved, a third author (LB) was consulted.

Data extraction

Data extracted from articles that met inclusion criteria included study characteristics (e.g. author, year of publication, country intervention was delivered), participant characteristics (e.g. gender, age, cancer type, and time since diagnosis), intervention characteristics (i.e. duration, mode of delivery, and behaviours targeted), and outcome measures. Interventions were categorised as addressing physical activity if they targeted bodily movement and included increasing exercise (i.e. planned, structured, and repetitive movements to increase physical fitness), leisure time activity, and reducing sedentary time. Interventions were categorised as addressing nutrition if they targeted the increase and/or decrease of certain foods or nutrients. Interventions were categorised as including a mental health component if they provided a manualised psychological treatment, psycho-education material on mental health and well-being, or counselling with the intention of addressing emotional distress. To calculate effect sizes between the intervention and control groups, the post-intervention sample size, means, and standard deviations for total QoL were extracted. As several QoL measures do not quantify a total score, the means and standard deviations of subscales relevant for physical, emotional, and social well-being in both the intervention and control groups were also extracted. These subscales were selected as they were present in all valid QoL scales. For inter-rater reliability, two authors (ML and CG) undertook data extraction on a subset of articles (n = 58).

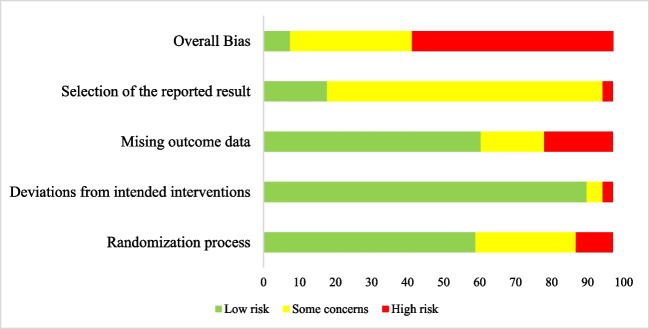

Quality assessment

The risk of bias of each study was evaluated by one author (ML) using the Cochrane Risk of Bias tool 2.0 (RoB 2; [23]). This tool evaluates the risk of bias in five domains: (1) the randomisation process, (2) deviations from intended interventions, (3) missing outcome data, (4) measurement of outcome, and (5) selection of the reported result. As the current meta-analysis was summarising self-reported QoL, domain 4: measurement of outcome, was not considered in the evaluation of risk. Using this tool, the articles were evaluated and judged on the domains as being either low risk of bias, some concerns, or high risk of bias. For overall bias, articles were considered to have low risk of bias if they were rated as low risk of bias on each of the domains and high risk of bias if they were rated as having high risk of bias on at least one of the domains or as having some concerns on at least two of the domains.

Data analysis

The Comprehensive Meta-Analysis computer package [24] was used for all analyses. Standardised mean differences (Hedge’s g) between the intervention and control groups with 95% confidence intervals were calculated for the total QoL and each of the QoL subscales. Effect sizes were pooled using a random effects model to derive the overall effect size of healthy lifestyle interventions on QoL for cancer survivors. Following this, three pre-specified subgroup analyses were conducted to investigate whether the efficacy of healthy lifestyle interventions on QoL was influenced by selected intervention components. The first subgroup analysis interventions were categorised based on the inclusion of a mental health component. The second sub-group analysis separated interventions based on their dominant mode of delivery, such as individual face-to-face, groups, telehealth, digital health, or print. As there were interventions where one delivery was not dominant, a multiple category was included. The final pre-specified sub-group analysis investigated interventions which had a shorter duration (i.e. 12 weeks or less) or a longer duration (i.e. 13 weeks or more). Narrative synthesis was used to summarise findings in studies which could not be included in the meta-analysis. The narrative synthesis focused on the efficacy of the healthy lifestyle intervention in comparison to the usual care control and the potential impact the intervention characteristics of the inclusion of a mental health component, the mode of intervention delivery, and intervention duration.

Heterogeneity and publication bias

The heterogeneity of the data was assessed using Q (presence of heterogeneity) and I2 (proportion of total variation between studies that results from heterogeneity) statistics [25]. The I2 scale ranges from 0% (no heterogeneity) to 100% (high heterogeneity). Cochrane’s guide to interpretation of the I2 statistic specifies that 0–40% = heterogeneity that might not be important, 30–60% = moderate heterogeneity, 50–90% = substantial heterogeneity, and 75–100% = considerable heterogeneity. To interpret the I2 statistic, the number of studies included magnitude and direction of the effect, and Q statistic was taken into consideration. Sources of heterogeneity were explored by conducting post hoc sub-group analyses [26], by dividing studies into two or more subgroups and calculating the Q and I2 statistics for each subgroup. Three subgroups were explored: (1) multi-component (i.e. targeting more than one health behaviour) vs single component (i.e. targeting a single health behaviour); (2) measure of QoL; (3) QoL measured as the primary vs secondary outcome. For the second subgroup analysis, the measures of QoL were grouped under their measurement system, rather than individual measures, to ensure relatively equal groups. For example, those who included the FACT-Breast, FACT-Colorectal, and FACT-General were grouped under FACT and the SF12 and SF-36 were grouped under SF.

Publication bias was evaluated by Egger’s regression intercept, which examines the correlation between effect sizes and standard errors of effect sizes. If there is a significant association between study effect size and study precision, this indicates the possibility of publication bias. Each QoL outcome was considered separately.

Results

Study selection

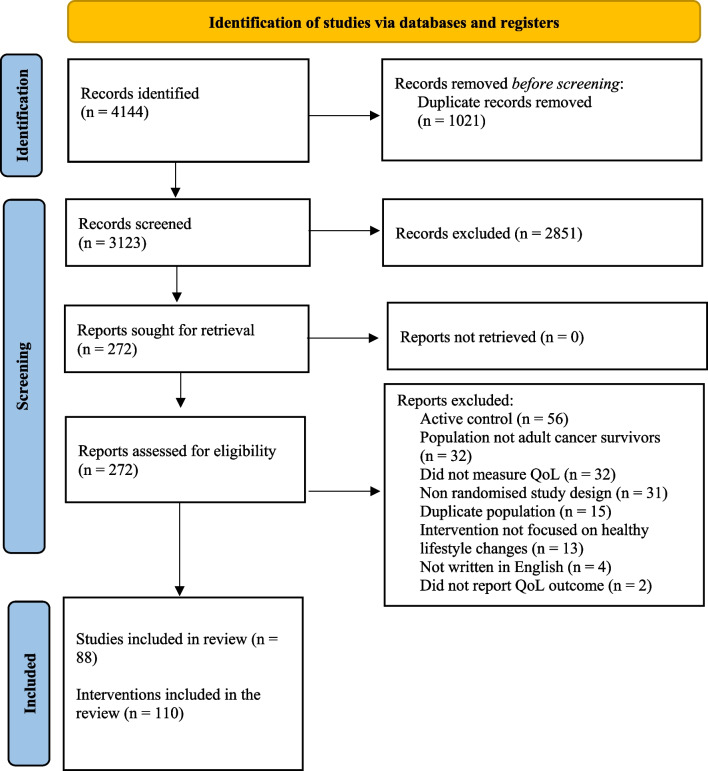

Figure 1 presents the PRISMA flow diagram of the study selection process. Following screening, 88 articles involving 110 interventions met inclusion criteria for the systematic review, and 66 articles met criteria for meta-analysis. Articles were most commonly excluded due to the use of an active control (e.g. workbook or telephone calls). The predominant reason for excluding articles from the meta-analysis was reporting change over time instead of post treatment means and standard deviations. The agreement rate between reviewers was 91.5% for title and abstract screening, 77.4% for full text review, and 66% for data extraction. Exacting different total scores for QoL when multiple scales were reported (e.g. SF-36 and FACT-G) accounted for 73% of the differences in the data extraction. In all instances of disagreement, consensus was reached through discussion.

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of included studies

Study characteristics

Multimedia B summarises the 88 included studies. The total number of participants included in this review was 9556, with sample sizes ranging from 14 to 641 and a median of 71. There was an over-representation of females in included studies with 51 interventions offered only to breast cancer survivors. The average age of included participants was 57.93 (SD = 11.32) years. Forty-eight studies reported time since diagnosis, of which the median was 23.53 months (range = 6.40–87.6 months). The majority of included studies were conducted in the USA (n = 27), Canada (n = 11), Australia (n = 9), Spain (n = 6), Netherlands (n = 6), and the UK (n = 5). In terms of study design, 30.7% studies measured QoL as their primary outcome. The most common QoL measures were the FACT (n = 33), EORTC QLQC30 (n = 25), and the SF questionnaire (n = 23).

Intervention characteristics

Mode of delivery

A diverse range of delivery modalities were investigated in the included interventions. Most utilised face-to-face delivery (n = 84), of which approximately half (n = 43) were provided individually [27–52] while the remainder were delivered via groups [43, 53–83]. Twenty-five (22.7%) of these face-to-face interventions were supported by additional modalities, such as printed or emailed materials [55–57, 84–86], telephone [41, 66, 87, 88], videos [89, 90], or a combination of these [71, 73, 91].

Sixteen studies utilised a digital health modality (such as an online platform, or a mobile application) [82, 92–97]. Within this group, wearable devices were also utilised as either the primary delivery modality [98] or accompanying another delivery modality [57, 87, 88, 98]. Nine utilised telehealth, of which 8 delivered content over phone calls and 1 investigated SMS delivery [99], whereby participants were sent education material over text messages. Delivery modalities less frequently used included DVDs [100] and print [98, 101–103].

Intervention duration

The duration of the interventions ranged from 2 to 104 weeks (M = 20, Mdn = 12). 50.9% of the interventions were delivered over 12 weeks or less, with the most common intervention durations being 12 weeks (31.8%), 26 weeks (15.5%), and 52 weeks (17.3%).

Health behaviours targeted

Physical activity

Most included interventions addressed physical activity (n = 107, 93.9%). Twenty-two interventions targeted aerobic activity (e.g. walking, cycling) [28–30, 34, 43, 45, 50, 51, 57, 58, 61, 63, 75, 80, 81, 91, 104, 105]. Seven interventions focused on resistance exercises (e.g. lifting weights) [35, 40, 48, 67, 78]. Thirty-four interventions promoted a combination of aerobic and resistance exercises [27, 31–33, 36–39, 41, 42, 52, 53, 55, 59, 68, 76, 77, 79, 83, 85, 89, 90, 93, 101, 103, 106–108]. Four interventions practiced yoga [60, 62, 72] and one intervention [70] involved a combination of aerobic, resistance, and yoga exercises. Twenty-five interventions did not specify a particular exercise, instead focusing on increasing minutes of physical activity per week [46, 47, 54, 71, 74, 82, 86, 87, 94–100, 102, 109], reducing sedentary time [92], or a combination of these [69, 88, 110].

Nutrition

Thirty-five (30.7%) of the included interventions contained a nutritional component. Of these interventions, 12 focused on diet restriction through decreasing certain food groups consumed [56], or reducing total daily calorie intake [50]. Common recommendations for daily calorie intake in the included interventions were between 1200 and 2000 kcal/day [38, 58, 83] or reducing the participants current calorie intake by 600 kcal [85]. Comparatively, six interventions focused on dietary change and promoted increasing certain food groups [65, 84, 97], such as 5 servings of vegetables and 2 servings of fruit per day, and increasing intake of nuts, grains, and fish. Thirteen interventions utilised a combination of dietary restriction and dietary change strategies [34, 55, 59, 69, 79, 87, 105–108]. Two inventions cited a particular diet plan, such as an anti-inflammatory diet [73] or the Mediterranean diet [56]. Six interventions included non-specified dietary guidance or counselling [70, 74, 77, 95, 99, 111]. Three interventions included recommendations to decrease alcohol consumption [55, 85, 108].

Mental health

Overall, 19 of the 110 (17.3%) interventions featured a mental health component in their protocol. Six provided mental health treatment based on evidence based psychological therapies, such as cognitive behavioural therapy [45, 66, 95, 97, 105] or Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction [79]. Seven interventions included psycho-educational material on social and emotional well-being [99], stress management [46, 56, 112], mindfulness [77], or psychological adjustment following a cancer diagnosis [111]. One intervention utilised meditation following a yoga session [60]. Three interventions described the use of ‘psychological support’ or counselling but did not provide further details [38, 42, 76].

Meta-analysis of overall intervention effects

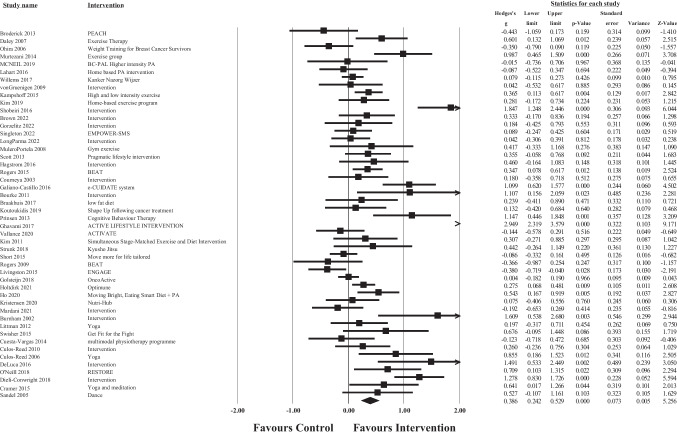

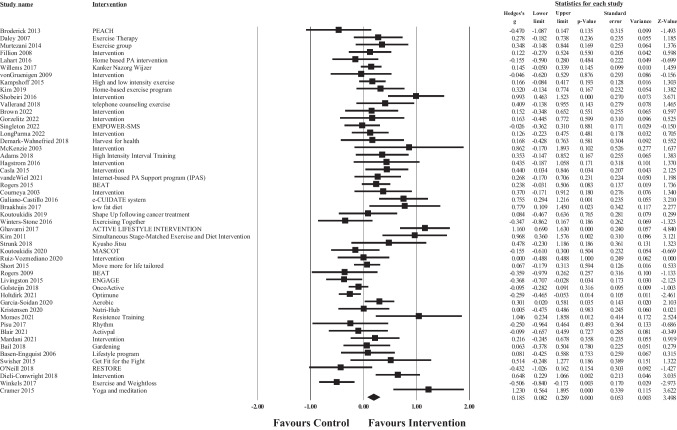

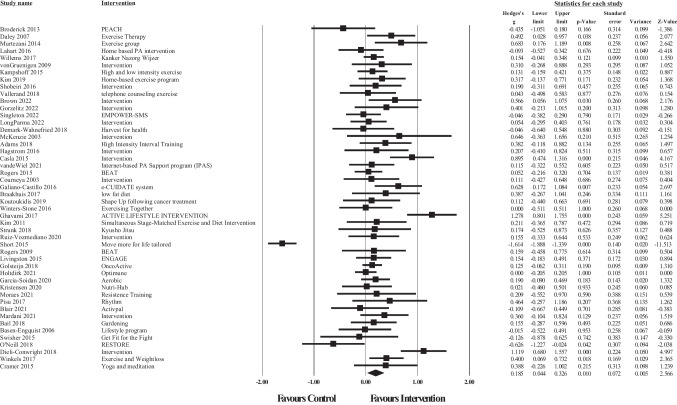

Post-treatment data was available for meta-analysis from 48 articles for total QoL (Fig. 2), 50 for physical well-being (Fig. 3), 50 for emotional well-being (Fig. 4), and 48 for social well-being (Fig. 5).

Fig. 2.

Forest plot of meta-analysis of effect sizes identified for each health behaviour intervention on post intervention Total QoL

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of meta-analysis of effect sizes identified for each health behaviour intervention on post intervention physical well-being

Fig. 4.

Forest plot of meta-analysis of effect sizes identified for each health behaviour intervention on post intervention emotional well-being

Fig. 5.

Forest plot of meta-analysis of effect sizes identified for each health behaviour intervention on post intervention social well-being

The overall pooled effect size of the interventions demonstrated a small significant, positive effect of healthy lifestyle interventions on cancer survivors’ total QoL (g = 0.32, 95% CI [0.17, 0.48], p >.001), physical well-being (g = 0.19, 95% CI [0.01, 0.36], p = 0.05), emotional well-being (g = 0.20, 95% CI [0.10, 0.31], p >.001), and social well-being (g = 0.18, 95% CI [0.05, 0.31], p = 0.01) in comparison to waitlist or usual care controls. For total QoL, 1 intervention demonstrated a negative effect, and favoured the control group over the intervention group [113]. Similar results were found for each of the subscale outcomes, whereby 3 interventions demonstrated negative effects (favouring the control condition) for physical well-being [73, 78, 113], 3 for emotional well-being [67, 95, 113, 114], and 2 for social well-being [103]. Consequently, these results should be interpreted with caution. According to Cohen’s criteria, substantial heterogeneity was observed for emotional well-being (Q = 142.99, p <.001; I2 = 65.73) and considerable heterogeneity was observed for total QoL (Q = 236.19, p <.001; I2 = 80.10), physical well-being (Q = 384.89, p <.001; I2 = 87.27), and social well-being (Q = 248.98, p <.001; I2 = 81.12); visual inspection of each forest plot demonstrates dispersion across 0.

Subgroup analyses

Table 1 summarises the results of the pre-specified subgroup analyses conducted to examine differences arising from the inclusion of a mental health component, mode of delivery, and the duration of the intervention on each of the QoL outcomes.

Table 1.

Prespecified and post hoc subgroup analyses

| Meta-analysis | N interventions | Sub-group (N interventions) |

Hedge’s g [95% CI] | Difference between subgroups: Q | Heterogeneity | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| I2 | Q | |||||

| Total QoL | ||||||

| Mental health | 48 | Yes (12) | 0.26 [0.10, 0.42] | 2.05, df = 1, p = 0.15 | 43.08 | 19.33, df = 11, p = .06 |

| No (36) | 0.41 [0.22, 0.60] | 83.87 | 216.98, df = 35, p <.001 | |||

| Mode of delivery | 47 | Individual (16) | 0.65 [0.27, 1.03] | 15.48, df = 5, p =.01* | 87.42 | 119.27, df = 15, p <.001 |

| Group (20) | 0.35 [0.14, 0.57] | 71.28 | 66.15, df = 16, p <.001 | |||

| Digital (5) | 0.26 [−0.02, 0.53] | 79.58 | 19.59, df = 4, p <.001 | |||

| Telehealth (2) | 0.14 [−0.15, 0.44] | 0 | 0.41, df = 5, p = 0.52† | |||

| Print (2) | −0.11 [−0.33, 0.11] | 0 | 0.16, df = 1, p = 0.69† | |||

| Multiple (2) | 0.21 [−0.46, 0.88] | 81.75 | 5.48, df = 1, p = 0.02 | |||

| Duration | 48 | ≤12 (29) | 0.35 [0.18, 0.51] | 0.44, df = 1, p = 0.50 | 73.88 | 107.18, df =28, p <.001 |

| ≥13 (19) | 0.45 [ 0.19, 0.71] | 86.01 | 128.68, df =17, p <.001 | |||

| Multicomponent | 48 | Yes (18) | 0.50 [0.26, 0.74] | 1.36, df = 1, p = 0.24 | 80.85 | 88.77, df = 17, p <.001 |

| No (30) | 0.32 [0.14, 0.50] | 79.84 | 143.88, df = 29, p <.001 | |||

| Measure | 43 | FACT (26) | 0.33 [0.16, 0.49] | 0.93, df = 1, p = 0.33 | 64.44 | 70.30, df = 25, p <.001 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 (17) | 0.48 [0.20, 0.77] | 88.92 | 144.39, df = 16, p <.001 | |||

| Level of measure | 48 | Primary (18) | 0.42 [0.21, 0.63] | 0.16, df = 1, p = 0.69 | 76.63 | 72.73, df = 17, p <.001 |

| Secondary (30) | 0.37 [0.17, 0.56] | 82.00 | 161.07, df = 29, p <.001 | |||

| Physical well-being | ||||||

| Mental health | 50 | Yes (14) | 0.22 [ 0.11, 0.34] | 0.10, df = 1, p = 0.76 | 18.93 | 16.04, df = 13, p =0.25† |

| No (36) | 0.18 [−0.06, 0.42] | 90.45 | 366.49, df = 34, p<.001 | |||

| Mode of delivery | 49 | Individual (16) | 0.36 [ 0.03, 0.68] | 15.95, df = 4, p = 0.003* | 83.93 | 93.31, df = 15, p<.001 |

| Group (22) | −0.03 [−0.36, 0.31] | 91.30 | 241.28, df = 21, p<.001 | |||

| Digital (6) | 0.20 [−0.06, 0.46] | 80.01 | 25.01, df = 5, p<.001 | |||

| Telehealth (3) | 0.27 [−0.05, 0.58] | 26.95 | 2.74, df = 2, p = 0.26† | |||

| Print (2) | 0.51 [−0.50, 1.51] | 92.64 | 13.58, df =1, p<.001 | |||

| Duration | 50 | ≤12 (27) | 0.33 [0.18, 0.49] | 46.73, df = 1, p = 0.03* | 69.07 | 84.06, df = 26, p<.001 |

| ≥13 (23) | −0.04 [−0.35, 0.26] | 92.48 | 279.11, df = 22, p<.001 | |||

| Multicomponent | 50 | Yes (23) | 0.29 [0.16, 0.42] | 1.87, df = 1, p = 0.17 | 52.59 | 46.40, df = 22 p = .002 |

| No (27) | 0.07 [−0.22, 0.35] | 91.96 | 323.57, df = 26, p<.001 | |||

| Measure | 55 | FACT (17) | −0.07 [−0.52, 0.38] | 3.72, df = 2, p = 0.16 | 93.44 | 243.93, df = 16, p<.001 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 (16) | 0.39 [0.13, 0.64] | 85.67 | 104.71, df = 15, p<.001 | |||

| SF (15) | 0.16 [0.01, 0.31] | 32.64 | 20.78, df =14, p=0.11† | |||

| Level of measure | 48 | Primary (15) | 0.31 [0.11, 0.52] | 1.87, df =1, p = 0.17 | 73.75 | 53.33, df = 14, p <.001 |

| Secondary (35) | 0.10 [−0.13,0 0.33] | 89.57 | 326.11, df = 34, p <.001 | |||

| Emotional well-being | ||||||

| Mental health | 50 | Yes (14) | 0.10 [−0.08, 0.36] | 0.93, df = 1, p = 0.36 | 60.90 | 34.17, df = 13, p = .001 |

| No (36) | 0.23 [0.10, 0.36] | 67.68 | 106.06, df = 5, p <.001 | |||

| Mode of delivery | 49 | Individual (17) | 0.30 [0.08, 0.51] | 3.27, df = 4, p = 0.51 | 66.27 | 47.44, df = 16, p <.001 |

| Group (21) | 0.12 [−0.05, 0.28] | 62.71 | 53.63, df = 20, p <.001 | |||

| Digital (6) | 0.08 [−0.16, 0.32] | 76.24 | 21.05, df = 5, p =.001 | |||

| Telehealth (3) | 0.41 [−0.17, 0.98] | 75.82 | 8.27, df = 2, p =.02 | |||

| Print (2) | 0.10 [−0.12, 0.32] | 53.74 | 2.16, df = 1, p = .14† | |||

| Duration | 50 | ≤12 (27) | 0.23 [0.08, 0.39] | 0.84, df = 1, p = 0.36 | 68.45 | 82.42, df = 26, p <.001 |

| ≥13 (23) | 0.14 [−0.01, 0.28] | 63.25 | 59.87, df = 22, p <.001 | |||

| Multicomponent | 50 | Yes (23) | 0.21 [0.04, 0.38] | 0.13, df = 1, p = 0.72 | 71.92 | 78.36, df = 22, p <.001 |

| No (27) | 0.17 [0.04, 0.30] | 59.73 | 64.56, df = 26, p <.001 | |||

| Measure | 49 | FACT (18) | 0.22 [0.06, 0.37] | 0.50, df = 2, p = 0.78 | 49.11 | 33.40, df = 17, p =.01 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 (16) | 0.23 [0.04, 0.43] | 75.61 | 61.51, df = 15, p <.001 | |||

| SF (15) | 0.14 [−0.05,0.33] | 55.88 | 31.73, df = 14, p = .004 | |||

| Level of measure | 50 | Primary (14) | 0.33 [0.13, 0.53] | 2.89, df = 1, p = 0.09 | 71.43 | 45.50, df = 13, p <.001 |

| Secondary (36) | 0.13 [0.004, 0.25] | 63.02 | 94.65, df = 35, p <.001 | |||

| Social well-being | ||||||

| Mental Health | 48 | Yes (13) | 0.07 [−0.03, 0.17] | 2.01, df = 1, p = 0.16 | 0 | 9.80, df = 12, p = 0.64† |

| No (35) | 0.23 [0.03, 0.43] | 85.71 | 237.02, df = 34, p <.001 | |||

| Mode of delivery | 48 | Individual (16) | 0.40 [0.18, 0.62] | 7.30, df = 4, p = 0.12 | 65.20 | 43.11, df = 15, p <.001 |

| Group (21) | 0.16 [0.04, 0.28] | 26.88 | 6.84, df = 20, p = .15† | |||

| Digital (6) | 0.13 [−0.01, 0.26] | 56.97 | 11.62, df = 5, p = 0.02 | |||

| Telehealth (3) | 0.03 [−0.23, 0.28] | 0 | 0.58, df = 2, p = 0.75† | |||

| Print (2) | −0.63 [−2.57, 1.30] | 98.06 | 51.46, df = 1, p = 0.99† | |||

| Duration | 48 | ≤12 (26) | 0.15 [−0.10, 0.39] | 0.35, df = 1, p = 0.56 | 86.89 | 190.68, df = 25, p <.001 |

| ≥13 (22) | 0.23 [0.09, 0.36] | 57.19 | 49.05, df = 21, p <.001 | |||

| Multicomponent | 48 | Yes (22) | 0.21 [0.06, 0.35] | 0.13, df = 1, p = 0.72 | 59.14 | 51.39, df = 21, p <.001 |

| No (26) | 0.16 [−0.05, 0.37] | 87.98 | 153.14, df = 25, p <.001 | |||

| Measure | 47 | FACT (17) | 0.14 [−0.24, 0.51] | 0.25, df = 2, p = 0.88 | 91.05 | 178.68, df = 16, p <.001 |

| EORTC QLQ-C30 (16) | 0.22 [0.07, 0.37] | 67.31 | 45.89, df = 15, p <.001 | |||

| SF (14) | 0.24 [0.09, 0.39] | 22.69 | 16.82, df = 13, p = .21† | |||

| Level of measure | 48 | Primary (14) | 0.24 [0.13, 0.36] | 0.85, df = 1, p = 0.36 | 15.20 | 15.33, df = 13, p = 0.29† |

| Secondary (34) | 0.14 [−0.06, 0.33] | 85.48 | 227.33, df = 33, p <.001 | |||

*The difference between groups is p <0.05

†Heterogeneity in this group is not significant

Mental health component

There were no significant differences in effect between interventions with or without a mental health component. Heterogeneity varied across these analyses: Heterogeneity was considerable on total QoL and emotional well-being subscales, whereas physical well-being and social well-being had no significant heterogeneity.

Modality

The mode of delivery subgroup analyses demonstrated a significant subgroup effect on total QoL and physical well-being. For total QoL, the individual (g = 0.65, 95% CI [0.27, 1.03]) and group modalities (g = 0.35, 95% CI [0.14, 0.57]) were associated with significant positive effects (favouring the intervention group). No other delivery modality was significant. Conversely, on the physical well-being outcome, only the individual modality (g = 0.36, 95% CI [0.03, 0.68]) was associated with a significant positive effect (favouring the intervention). However, these results should be interpreted with caution due to covariation distribution. Only two or three trials were included in the analysis for the print, telehealth, and multiple subgroups. Therefore, we cannot confidentially conclude that this is a true subgroup effect. Heterogeneity notably reduced in the group modality subgroup with the social well-being outcome and reduced in the smaller groups across the analyses, specifically the telephone and print subgroups.

Duration

There was a significant subgroup effect of duration on the physical well-being outcome. Shorter interventions (g = 0.33, 95% CI [0.18, 0.49]) were associated with a small positive effect and favoured the intervention group, whereas longer interventions (g = −0.04, 95% CI [−0.35, 0.26]) did not demonstrate a significant effect. However, substantial unexplained heterogeneity remained within each of the subgroups.

Sources of heterogeneity

The post hoc subgroup analyses exploring additional sources of heterogeneity are also presented in Table 1. None of the post hoc subgroup analyses identified significant associations across all outcomes. Heterogeneity remained considerable across these subgroup analyses, with the exception of studies which measured QoL as their primary outcome on the social well-being subscale (I2 = 15.20), and studies which used the SF to measure physical well-being (I2 = 32.64) and social well-being subscales (I2 = 22.69).

Narrative synthesis of interventions on QoL

Twenty-two studies investigating 31 interventions were excluded from the meta-analysis as they did not provide post-treatment means and standard deviations [36, 38, 43, 48, 51, 53, 59, 74, 76, 80, 86, 89–91, 98, 107–109, 111, 115, 116]. Total QoL was reported in 14 studies evaluating 19 interventions. Of these, 5 (26.3%) interventions demonstrated significant improvements compared to control [36, 38, 51, 76, 91]. For physical well-being, 10 of the 25 interventions (40%) reporting this outcome showed significant improvements compared to control [36, 51, 74, 91, 111, 115]. In terms of emotional well-being, 6 of the 24 interventions (25%) reported greater improvements in the intervention group [51, 76, 91, 115], though in one study [43] this benefit was only found in a subgroup of participants (those not currently taking endocrine therapy). Lastly, for social well-being, only 1 out of 25 interventions reported significant improvements compared to a waitlist intervention [111]. Moreover, Saarto and colleagues [80] found that an aerobic exercise intervention demonstrated significantly less change over time in social well-being compared to the usual care control group.

Three studies investigated 5 interventions with a mental health component, all of which showed significant improvements in at least one area of QoL. Three of the interventions utilised individual counselling and demonstrated significant improvements in total QoL [38, 76], physical well-being [42, 76], and emotional well-being [76] compared to the control groups. Naumann and colleagues [76] also investigated group counselling, which demonstrated significant improvements in physical well-being compared to the control group. Lastly, one intervention investigated by Chang and colleagues [111] involved an e-health booklet on psychological adjustment after cancer and this intervention demonstrated significant improvements in physical well-being and social well-being compared to the control group.

In terms of mode of delivery, all interventions that demonstrated significant improvements in all QoL measures utilised face-to-face delivery [individual n = 6, group n = 3; 36, 38, 51, 76, 91, 111], with the exception of one telehealth intervention implemented by Baruth and colleagues [115], which demonstrated significant improvements in physical well-being and emotional well-being in comparison to the control group.

Finally, with regard to duration, 17 interventions were offered over 12 weeks or less. Of these interventions, 4 (23.5%) demonstrated improvements in total Qol [36, 38, 51, 76], 7 (41.2%) demonstrated significant improvements in physical well-being [36, 42, 51, 76, 111, 115], 4 (23.5%) demonstrated significant improvements in emotional well-being [51, 76, 115], and 1 (5.8%) demonstrated significant improvements in social well-being [111] compared to the control group. Fourteen interventions were delivered over 13 weeks or more. Only 1 (7.1%) intervention demonstrated improvements in total QoL [91], 3 (21.4%) demonstrated improvements in physical well-being [59, 74, 91], and 1 (7.1%) demonstrated improvements in emotional well-being in comparison to the control group [91].

Risk of bias

The results from the risk of bias assessment are presented in Table 3 (Multimedia C) and a visual representation is provided in Fig. 6. Overall, the risk of bias was high for 55.9% of articles included in the meta-analysis. Domain 5, selection of the reported result, was the biggest contributor for risk of bias concerns, as most of the studies did not publish prespecified measurements or a data analysis plan. Consequently, only 5 studies were rated as having low risk of bias.

Fig. 6.

Risk of bias assessment for included domains as percentages across all studies included in the meta-analysis

Publication bias

Publication bias was indicated by the Egger’s regression intercept for the Total QoL outcome, 1.90, 95% CI [0.40, 3.40], p = .01, and the emotional well-being subscale, 1.92, 95% CI [0.09, 3.75], p = .04.

Discussion

This systematic review and meta-analysis updates and extends the current evidence for the use of healthy lifestyle interventions to improve the QoL in post-treatment cancer survivors. Overall, results from the meta-analysis indicate a small but significant effect in favour of healthy lifestyle interventions’ positive impact on total QoL and on the dimensions of physical well-being, emotional well-being, and social well-being compared to a usual care or waitlist control. However, there was notable heterogeneity among the included studies and the majority did not find a significant effect of the intervention on all QoL outcomes. This finding was corroborated by studies included in the narrative synthesis, where out of 22 healthy lifestyle interventions examined, 17 did not differ from the usual care or waitlist control groups in each of the QoL domains. The observed heterogeneity in the results aligns with the inconsistencies found in previous research on this topic.

A unique contribution of this paper was to investigate whether the association between the intervention and QoL is moderated by key intervention characteristics, primarily the inclusion of a mental health component. There was no evidence that the inclusion of a mental health component impacted the association between participation in a healthy lifestyle intervention and QoL. Consequently, there is a discrepancy between what cancer survivors request to be part of a healthy lifestyle program and support from current research on these interventions impact on QoL. A potential explanation is that improving physical well-being through physical activity and diet also addresses emotional well-being and overall QoL [117]. However, it is premature to discount the usefulness of including a mental health component, given the small number of studies which continued to display high levels of heterogeneity. Consequently, more evidence is required to appropriately answer this question. Alternatively, including a mental health component may have benefits in other areas, such as addressing barriers experienced by cancer survivors in participating in physical activity and a nutritious diet [18, 19]. Furthermore, psychosocial issues are one of the most prominent unmet needs described by cancer survivors [118] and including a component addressing these has the potential to make cancer survivors feel more supported following treatment. Therefore, future reviews might consider investigating whether including a mental health component in a healthy lifestyle intervention is associated with increased physical activity and diet outcomes or promotes more positive qualitative feedback compared to interventions which do not.

In contrast, mode of delivery and intervention duration emerged as predictors of intervention efficacy: Face-to-face delivery, either individually or in a group format, was associated with significantly higher total QoL. Individual face-to-face delivery was also associated with significantly higher physical well-being. Similarly, shorter interventions were associated with greater improvements in physical well-being. This finding aligns to some extent with the findings from a meta-analysis completed by Ferrer and colleagues [7], which investigated exercise interventions for cancer survivors and also found that intervention duration was inversely associated with QoL outcomes. However, Ferrer and colleagues found one exception to this relationship where the intensity of the intervention moderated outcomes, such that longer interventions (i.e. 26 weeks) with higher intensity exercise were associated with greater changes in QoL than shorter interventions (i.e. 8 weeks) and/or interventions with lower intensity exercise. Thus, while select longer interventions may be beneficial, collectively the weight of evidence from both prior and current meta-analyses support the implementation of short-term and face-to-face delivered healthy lifestyle interventions at the completion of cancer treatment, particularly for those looking to improve their physical well-being.

Nagpal and colleagues [119] have previously recommended that adherence is an important consideration when evaluating the efficacy of exercise interventions, due to the implications on whether participants receive the recommended ‘dose.’ Shorter durations and face-to-face modalities may promote greater engagement and adherence by minimising time commitments and enhancing accountability [120]. Further, interventions involving intense exercise may necessitate supervision to ensure participant safety and offer the advantage of increased accountability and tailoring. However, adherence data was not extracted in either the current study, nor the meta-analysis conducted by Ferrer and colleagues. To date, no research has directly compared the degree of adherence to shorter verses longer healthy lifestyle interventions in the cancer survivor or other relevant populations, such as older individuals or individuals with other chronic health conditions. Consequently, future primary research should consider comparing the same healthy lifestyle interventions with differing durations or delivery modalities to investigate adherence and its relationship to QoL outcomes. Future reviews should consider extracting adherence data to investigate its relationship with other intervention characteristics and outcomes. This meta-analysis provides preliminary evidence to suggest that interventions delivered via telephone or online can lead to comparable outcomes to face-to-face interventions; however, more studies are required to compare the different delivery modalities on QoL in cancer survivors.

Limitations

Although the overall meta-analysis and subgroup analyses yielded significant findings, these results should be interpreted with caution due to high levels of heterogeneity, limited power, high risk of bias, and lack of follow-up data. High levels of heterogeneity are commonly reported in meta-analyses on this topic. Notable heterogeneity continued across the pre-defined subgroup analyses, with only a reduction observed in individual subgroups, typically characterised by a low number of included studies (i.e. fewer than 10 studies). Additionally, the current meta-analysis may have limited power to detect an effect of the healthy lifestyle interventions on QoL, as less than one third of the included studies were designed to measure QoL. Consequently, the majority of the included studies may not be adequately powered to detect an effect on QoL. We attempted to address these limitations through post hoc subgroup analyses investigating multi-verse single-component interventions, whether QoL was measured as a primary or secondary outcome, and the type of outcome used, however, nil differences or reductions in heterogeneity were observed. Additionally, the validity of the results may be impacted by the quality of the studies, as the majority of them presented with a high risk of bias. Finally, as this current meta-analysis did not extract follow-up data, we are unable to evaluate whether the effects on QoL are maintained after the intervention period.

Additionally, there may be clinical factors that may moderate the efficacy of healthy lifestyle interventions on QoL in cancer survivors that were not explored in this study. A recent follow-up analysis conducted by Schleicher and colleagues [121] identified that breast cancer survivors participating the BEAT intervention who had a longer time since diagnosis (<24 months) and those who did not have a history of chemotherapy demonstrated greater increases in QoL. Schleicher and colleagues suggested that this may be due to perceived physical functioning, as cancer survivors with a more recent diagnosis may be experiencing acute side effects from treatment, such as fatigue and nausea. This finding was particularly relevant for time since diagnosis, as those who were more than 24 months post treatment were also more likely to engage in more moderate and vigorous physical activity post treatment. Future systematic reviews and meta-analyses should consider extracting data on time since diagnosis and treatment type to explore these as potential moderating factors.

Conclusion

Overall, the current meta-analysis suggests that participating in any healthy lifestyle intervention following cancer treatment is likely to have positive benefits on QoL. Interventions which are delivered face-to-face or over a shorter duration may have a greater impact on the efficacy of such interventions; however, only a few randomised control trials have investigated alternative delivery modalities, such as digital or telehealth. Furthermore, few randomised control trials have specifically investigated the inclusion of a mental health component to healthy lifestyle interventions. Consequently, there is a need for future research to develop and rigorously evaluate healthy lifestyle interventions which also address mental health and utilise alternative delivery modalities.

Supplementary information

(DOCX 24 kb)

(DOCX 154 kb)

(DOCX 350 kb)

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge Dr. Julia Morris for her contribution to the study conceptualisation.

Author contribution

Morgan Leske, Bogda Koczwara, and Lisa Beatty contributed to the study conception and design. Data collection was performed by Morgan Leske and Christina Galanis and analysis were performed by Morgan Leske. The first draft of the manuscript was written by Morgan Leske and all authors commented on previous versions of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open Access funding enabled and organized by CAUL and its Member Institutions

Data availability

The datasets generated and analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. Cancer in Australia 2021;2021. 10.25816/ye05-nm50

- 2.Jefford M, Ward AC, Lisy K, Lacey K, Emery JD, Glaser AW, et al. Patient-reported outcomes in cancer survivors: a population-wide cross-sectional study. Support Care Cancer. 2017. 10.1007/s00520-017-3725-5. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 3.Mazariego CG, Juraskova I, Campbell R, Smith DP. Long-term unmet supportive care needs of prostate cancer survivors: 15-year follow-up from the NSW Prostate Cancer Care and Outcomes Study. Support Care Cancer. 2020. 10.1007/s00520-020-05389-x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 4.Joshy G, Thandrayen J, Koczwara B, Butow P, Laidsaar-Powell R, Rankin N, et al. Disability, psychological distress and quality of life in relation to cancer diagnosis and cancer type: population-based Australian study of 22,505 cancer survivors and 244,000 people without cancer. BMC Med. 2020. 10.1186/s12916-020-01830-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Cella DF, Tulsky DS, Gray G, Sarafian B, Linn E, Bonomi A, et al. The Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy scale: development and validation of the general measure. J Clin Oncol. 1993. 10.1200/JCO.1993.11.3.570. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 6.Niezgoda HE, Pater JL. A validation study of the domains of the core EORTC Quality of Life Questionnaire. Qual Life Res. 1993. 10.1007/BF00449426. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Ferrer RA, Huedo-Medina TB, Johnson BT, Ryan S, Pescatello LS. Exercise interventions for cancer survivors: a meta-analysis of quality of life outcomes. Ann Behav Med. 2011. 10.1007/s12160-010-9225-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Castro-Espin C, Agudo A. The Role of Diet in Prognosis among Cancer Survivors: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Dietary Patterns and Diet Interventions. Nutrients. 2022;14 10.3390/nu14020348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Duijts SF, Faber MM, Oldenburg HS, van Beurden M, Aaronson NK. Effectiveness of behavioral techniques and physical exercise on psychosocial functioning and health-related quality of life in breast cancer patients and survivors-a meta-analysis. Psycho-Oncology. 2011. 10.1002/pon.1728. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 10.Aune D, Markozannes G, Abar L, Balducci K, Cariolou M, Nanu N, et al. Physical activity and health-related quality of life in women with breast cancer: a meta-analysis. JNCI Cancer Spectrum. 2022. 10.1093/jncics/pkac072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Zeng Y, Huang M, Cheng ASK, Zhou Y, So WKW. Meta-analysis of the effects of exercise intervention on quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Breast Cancer. 2014. 10.1007/s12282-014-0521-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Heredia-Ciuró A, Martín-Núñez J, López-López JA, López-López L, Granados-Santiago M, Calvache-Mateo A, et al. Effectiveness of healthy lifestyle–based interventions in lung cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Support Care Cancer. 2022. 10.1007/s00520-022-07542-0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Smits A, Lopes A, Das N, Bekkers R, Massuger L, Galaal K. The effect of lifestyle interventions on the quality of life of gynaecological cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gynecol Oncol. 2015. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2015.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 14.Baguley BJ, Skinner TL, Wright ORL. Nutrition therapy for the management of cancer-related fatigue and quality of life: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Br J Nutr. 2019. 10.1017/S000711451800363X. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 15.Larson JL, Rosen AB, Wilson FA. The effect of telehealth interventions on quality of life of cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Health Informatics J. 2019. 10.1177/1460458219863604. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Li J, Liu Y, Jiang J, Peng X, Hu X. Effect of telehealth interventions on quality of life in cancer survivors: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Int J Nurs Stud. 2021. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2021.103970. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Grant AR, Koczwara B, Morris JN, Eakin E, Short CE, Beatty L. What do cancer survivors and their health care providers want from a healthy living program? Results from the first round of a co-design project. Support Care Cancer. 2021. 10.1007/s00520-021-06019-w. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 18.Ventura EE, Ganz PA, Bower JE, Abascal L, Petersen L, Stanton AL, et al. Barriers to physical activity and healthy eating in young breast cancer survivors: modifiable risk factors and associations with body mass index. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013. 10.1007/s10549-013-2749-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 19.Cho D, Park CL. Barriers to physical activity and healthy diet among breast cancer survivors: a multilevel perspective. Eur J Cancer Care. 2018;27:e12772. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. BMJ. 2009. 10.1136/bmj.b2535. [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Ware JEJ, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-ltem Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36): I. Conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ware JE, Kosinski M, Keller SD. A 12-Item Short-Form Health Survey: Construction of Scales and Preliminary Tests of Reliability and Validity. Med Care. 1996. 10.1097/00005650-199603000-00003. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Sterne JA, Savović J, Page MJ, Elbers RG, Blencowe NS, Boutron I, Cates CJ, Cheng HY, Corbett MS, Eldridge SM, Emberson JR. RoB 2: a revised tool for assessing risk of bias in randomised trials. BMJ. 2019. 10.1136/bmj.l4898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Borenstein M, Hedges L, Higgins J, Rothstein H. Comprehensive meta-analysis version 3.3. Englewood, NJ, Biostat, 2014.

- 25.Higgins JPT, Thompson SG, Deeks JJ, Altman DG. Measuring inconsistency in meta-analyses. BMJ. 2003. 10.1136/bmj.327.7414.557. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 26.Cuijpers P. Meta-analyses in mental health research: a practical guide, vol. 15. Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam; 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Casla S, López-Tarruella S, Jerez Y, Marquez-Rodas I, Galvao DA, Newton RU, et al. Supervised physical exercise improves VO 2max, quality of life, and health in early stage breast cancer patients: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015. 10.1007/s10549-015-3541-x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 28.Adams SC, DeLorey DS, Davenport MH, Fairey AS, North S, Courneya KS. Effects of high-intensity interval training on fatigue and quality of life in testicular cancer survivors. Br J Cancer. 2018. 10.1038/s41416-018-0044-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 29.Burnham TR, Wilcox A. Effects of exercise on physiological and psychological variables in cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2002. 10.1097/00005768-200212000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 30.Courneya KS, Mackey JR, Bell GJ, Jones LW, Field CJ, Fairey AS. Randomized controlled trial of exercise training in postmenopausal breast cancer survivors: cardiopulmonary and quality of life outcomes. J Clin Oncol. 2003. 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.093. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Culos-Reed SN, Robinson JW, Lau H, Stephenson L, Keats M, Norris S, et al. Physical activity for men receiving androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer: benefits from a 16-week intervention. Support Care Cancer. 2010. 10.1007/s00520-009-0694-3. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 32.De Luca V, Minganti C, Borrione P, Grazioli E, Cerulli C, Guerra E, et al. Effects of concurrent aerobic and strength training on breast cancer survivors: a pilot study. Public Health. 2016. 10.1016/j.puhe.2016.03.028. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 33.Dieli-Conwright CM, Courneya KS, Demark-Wahnefried W, Sami N, Lee K, Sweeney FC, et al. Aerobic and resistance exercise improves physical fitness, bone health, and quality of life in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res: BCR. 2018. 10.1186/s13058-018-1051-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 34.Ghavami H, Akyolcu N. Effects of a lifestyle interventions program on quality of life in breast cancer survivors. UHOD - Uluslararasi Hematoloji-Onkoloji Dergisi. 2017. 10.4999/uhod.171734.

- 35.Hagstrom AD, Marshall PWM, Lonsdale C, Cheema BS, Fiatarone Singh MA, Green S. Resistance training improves fatigue and quality of life in previously sedentary breast cancer survivors: a randomised controlled trial. Eur J Cancer Care. 2016. 10.1111/ecc.12422. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 36.Herrero F, San Juan AF, Fleck SJ, Balmer J, Perez M, Canete S, et al. Combined aerobic and resistance training in breast cancer survivors: a randomized, controlled pilot trial. Int J Sports Med. 2006. 10.1055/s-2005-865848. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 37.Koutoukidis DA, Land J, Hackshaw A, Heinrich M, McCourt O, Beeken RJ, et al. Fatigue, quality of life and physical fitness following an exercise intervention in multiple myeloma survivors (MASCOT): an exploratory randomised Phase 2 trial utilising a modified Zelen design. Br J Cancer. 2020. 10.1038/s41416-020-0866-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 38.Kwiatkowski F, Mouret-Reynier M-A, Duclos M, Bridon F, Hanh T, Van Praagh-Doreau I, et al. Long-term improvement of breast cancer survivors' quality of life by a 2-week group physical and educational intervention: 5-year update of the 'PACThe' trial. Br J Cancer. 2017. 10.1038/bjc.2017.112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 39.McKenzie DC, Kalda AL, McKenzie DC, Kalda AL. Effect of upper extremity exercise on secondary lymphedema in breast cancer patients: a pilot study. J Clin Oncol. 2003. 10.1200/JCO.2003.04.069. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Moraes RF, Ferreira-Junior JB, Marques VA, Vieira A, Lira CAB, Campos MH, et al. Resistance training, fatigue, quality of life, anxiety in breast cancer survivors. J Strength Condition Res (Lippincott Williams & Wilkins). 2021. 10.1519/jsc.0000000000003817. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 41.Mulero Portela AL, Colón Santaella CL, Cruz Gómez C, Burch A. Feasibility of an exercise program for Puerto Rican women who are breast cancer survivors. Rehab Oncol. 2008. 10.1097/01893697-200826020-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 42.Naumann F, Martin E, Philpott M, Smith C, Groff D, Battaglini C. Can counseling add value to an exercise intervention for improving quality of life in breast cancer survivors? A feasibility study. J Support Oncol. 2012. 10.1016/j.suponc.2011.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 43.Park S-H, Tish Knobf M, Jeon S. Endocrine therapy-related symptoms and quality of life in female cancer survivors in the Yale Fitness Intervention Trial. J Nurs Scholarship : an Official Publication Sigma Theta Tau Int Honor Soci Nurs. 2019. 10.1111/jnu.12471. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 44.Pisu M, Demark-Wahnefried W, Kenzik KM, Oster RA, Lin CP, Manne S, et al. A dance intervention for cancer survivors and their partners (RHYTHM). J Cancer Surv : Res Pract. 2017. 10.1007/s11764-016-0593-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Prinsen H, Bleijenberg G, Heijmen L, Zwarts MJ, Leer JWH, Heerschap A, et al. The role of physical activity and physical fitness in postcancer fatigue: a randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer. 2013. 10.1007/s00520-013-1784-9. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 46.Rogers LQ, Courneya KS, Anton PM, Hopkins-Price P, Verhulst S, Vicari SK, et al. Effects of the BEAT Cancer physical activity behavior change intervention on physical activity, aerobic fitness, and quality of life in breast cancer survivors: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015. 10.1007/s10549-014-3216-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 47.Rogers LQ, Hopkins-Price P, Vicari S, Markwell S, Pamenter R, Courneya KS, et al. Physical activity and health outcomes three months after completing a physical activity behavior change intervention: persistent and delayed effects. Cancer Epidemiol, Biomarkers Prev : A Publication Am Assoc Cancer Res, Cosponsored By The Am Soc Prev Oncol. 2009. 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-1045. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Speck RM, Gross CR, Hormes JM, Ahmed RL, Lytle LA, Hwang W-T, et al. Changes in the Body Image and Relationship Scale following a one-year strength training trial for breast cancer survivors with or at risk for lymphedema. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2010. 10.1007/s10549-009-0550-7. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 49.Strunk MA, Zopf EM, Steck J, Hamacher S, Hallek M, Baumann FT. Effects of Kyusho Jitsu on physical activity-levels and quality of life in breast cancer patients. In vivo (Athens, Greece). 2018. 10.21873/invivo.11313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 50.Swisher AK, Abraham J, Bonner D, Gilleland D, Hobbs G, Kurian S, et al. Exercise and dietary advice intervention for survivors of triple-negative breast cancer: effects on body fat, physical function, quality of life, and adipokine profile. Support Care Cancer : official J Multinat Assoc Support Care Cancer. 2015. 10.1007/s00520-015-2667-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 51.Toohey K, Pumpa K, McKune A, Cooke J, DuBose KD, Yip D, et al. Does low volume high-intensity interval training elicit superior benefits to continuous low to moderate-intensity training in cancer survivors? World J Clin Oncol. 2018. 10.5306/wjco.v9.i1.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 52.Winters-Stone KM, Lyons KS, Dobek J, Dieckmann NF, Bennett JA, Nail L, et al. Benefits of partnered strength training for prostate cancer survivors and spouses: results from a randomized controlled trial of the Exercising Together project. J Cancer Surv : Res Pract. 2016. 10.1007/s11764-015-0509-0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 53.Alibhai SMH, O'Neill S, Fisher-Schlombs K, Breunis H, Timilshina N, Brandwein JM, et al. A pilot phase II RCT of a home-based exercise intervention for survivors of AML. Support Care Cancer : official J Multinat Assoc Support Care Cancer. 2014. 10.1007/s00520-013-2044-8. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 54.Basen-Engquist K, Taylor CLC, Rosenblum C, Smith MA, Shinn EH, Greisinger A, et al. Randomized pilot test of a lifestyle physical activity intervention for breast cancer survivors. Patient Educ Couns. 2006. 10.1016/j.pec.2006.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 55.Bourke L, Thompson G, Gibson DJ, Daley A, Crank H, Adam I, et al. Pragmatic lifestyle intervention in patients recovering from colon cancer: a randomized controlled pilot study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil. 2011. 10.1016/j.apmr.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 56.Braakhuis A, Campion P, Bishop K. The effects of dietary nutrition education on weight and health biomarkers in breast cancer survivors. Med Sci (Basel, Switzerland). 2017. 10.3390/medsci5020012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 57.Broderick JM, Guinan E, Kennedy MJ, Hollywood D, Courneya KS, Culos-Reed SN, et al. Feasibility and efficacy of a supervised exercise intervention in de-conditioned cancer survivors during the early survivorship phase: the PEACH trial. J Cancer Surv : Res practice. 2013. 10.1007/s11764-013-0294-6. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 58.Brown JC, Giobbie-Hurder A, Yung RL, Mayer EL, Tolaney SM, Partridge AH, et al. The effects of a clinic-based weight loss program on health-related quality of life and weight maintenance in cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Psycho-oncology. 2022. 10.1002/pon.5817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 59.Brown JC, Sarwer DB, Troxel AB, Sturgeon K, DeMichele AM, Denlinger CS, et al. A randomized trial of exercise and diet on health-related quality of life in survivors of breast cancer with overweight or obesity. Cancer. 2021. 10.1002/cncr.33752. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 60.Cramer H, Rabsilber S, Lauche R, Kummel S, Dobos G. Yoga and meditation for menopausal symptoms in breast cancer survivors-a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2015. 10.1002/cncr.29330. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 61.Cuesta-Vargas AI, Buchan J, Arroyo-Morales M. A multimodal physiotherapy programme plus deep water running for improving cancer-related fatigue and quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Eur J Cancer Care. 2014. 10.1111/ecc.12114. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 62.Culos-Reed SN, Carlson LE, Daroux LM, Hately-Aldous S. A pilot study of yoga for breast cancer survivors: physical and psychological benefits. Psycho-Oncology. 2006. 10.1002/pon.1021. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 63.Daley AJ, Crank H, Saxton JM, Mutrie N, Coleman R, Roalfe A. Randomized trial of exercise therapy in women treated for breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2007. 10.1200/JCO.2006.09.5083. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 64.Darga LL, Magnan M, Mood D, Hryniuk WM, DiLaura NM, Djuric Z. Quality of life as a predictor of weight loss in obese, early-stage breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2007. 10.1188/07.ONF.86-92. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 65.Demark-Wahnefried W, Cases MG, Cantor AB, Fruge AD, Smith KP, Locher J, et al. Pilot randomized controlled trial of a home vegetable gardening intervention among older cancer survivors shows feasibility, satisfaction, and promise in improving vegetable and fruit consumption, reassurance of worth, and the trajectory of central adipos. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2018. 10.1016/j.jand.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 66.Fillion L, Gagnon P, Leblond F, Gelinas C, Savard J, Dupuis R, et al. A brief intervention for fatigue management in breast cancer survivors. Cancer Nurs. 2008. 10.1097/01.NCC.0000305698.97625.95. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 67.Garcia-Soidan JL, Perez-Ribao I, Leiros-Rodriguez R, Soto-Rodriguez A. Long-term influence of the practice of physical activity on the self-perceived quality of life of women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020. 10.3390/ijerph17144986. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 68.Kampshoff CS, Chinapaw MJM, Brug J, Twisk JWR, Schep G, Nijziel MR, et al. Randomized controlled trial of the effects of high intensity and low-to-moderate intensity exercise on physical fitness and fatigue in cancer survivors: results of the Resistance and Endurance exercise After ChemoTherapy (REACT) study. BMC Med. 2015. 10.1186/s12916-015-0513-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 69.Koutoukidis DA, Beeken RJ, Manchanda R, Burnell M, Ziauddeen N, Michalopoulou M, et al. Diet, physical activity, and health-related outcomes of endometrial cancer survivors in a behavioral lifestyle program: the Diet and Exercise in Uterine Cancer Survivors (DEUS) parallel randomized controlled pilot trial. Int J Gynecol Cancer : official J Int Gynecol Cancer Soc. 2019. 10.1136/ijgc-2018-000039. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 70.Kristensen MB, Wessel I, Beck AM, Dieperink KB, Mikkelsen TB, Moller J-JK, et al. Effects of a multidisciplinary residential nutritional rehabilitation program in head and neck cancer survivors-results from the NUTRI-HAB randomized controlled trial. Nutrients. 2020. 10.3390/nu12072117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 71.Lahart IM, Metsios GS, Nevill AM, Kitas GD, Carmichael AR. Randomised controlled trial of a home-based physical activity intervention in breast cancer survivors. BMC Cancer. 2016. 10.1186/s12885-016-2258-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 72.Littman AJ, Bertram LC, Ceballos R, Ulrich CM, Ramaprasad J, McGregor B, et al. Randomized controlled pilot trial of yoga in overweight and obese breast cancer survivors: effects on quality of life and anthropometric measures. Support Care Cancer : official J Multinat Assoc Support Care in Cancer. 2012. 10.1007/s00520-010-1066-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 73.Long Parma DA, Reynolds GL, Munoz E, Ramirez AG. Effect of an anti-inflammatory dietary intervention on quality of life among breast cancer survivors. Support Care Cancer : official J Multinat Assoc Support Care in Cancer. 2022. 10.1007/s00520-022-07023-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 74.McCarroll ML, Armbruster S, Frasure HE, Gothard MD, Gil KM, Kavanagh MB, et al. Self-efficacy, quality of life, and weight loss in overweight/obese endometrial cancer survivors (SUCCEED): a randomized controlled trial. Gynecol Oncol. 2014. 10.1016/j.ygyno.2013.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 75.Murtezani A, Ibraimi Z, Bakalli A, Krasniqi S, Disha ED, Kurtishi I. The effect of aerobic exercise on quality of life among breast cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Res Ther. 2014. 10.4103/0973-1482.137985. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 76.Naumann F, Munro A, Martin E, Magrani P, Buchan J, Smith C, et al. An individual-based versus group-based exercise and counselling intervention for improving quality of life in breast cancer survivors. A feasibility and efficacy study. Psycho-oncology. 2012. 10.1002/pon.2015. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 77.O'Neill LM, Guinan E, Doyle SL, Bennett AE, Murphy C, Elliott JA, et al. The RESTORE randomized controlled trial: impact of a multidisciplinary rehabilitative program on cardiorespiratory fitness in esophagogastric cancer survivorship. Ann Surg. 2018. 10.1097/SLA.0000000000002895. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 78.Ohira T, Schmitz KH, Ahmed RL, Yee D. Effects of weight training on quality of life in recent breast cancer survivors: the Weight Training for Breast Cancer Survivors (WTBS) Study. Cancer. 2006. 10.1002/cncr.21829. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 79.Ruiz-Vozmediano J, Lohnchen S, Jurado L, Recio R, Rodriguez-Carrillo A, Lopez M, et al. Influence of a multidisciplinary program of diet, exercise, and mindfulness on the quality of life of stage IIA-IIB breast cancer survivors. Integr Cancer Ther. 2020. 10.1177/1534735420924757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 80.Saarto T, Penttinen HM, Sievanen H, Kellokumpu-Lehtinen P-L, Hakamies-Blomqvist L, Nikander R, et al. Effectiveness of a 12-month exercise program on physical performance and quality of life of breast cancer survivors. Anticancer Res. 2012;32:3875–84. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Shobeiri F, Masoumi SZ, Nikravesh A, Heidari Moghadam R, Karami M. The impact of aerobic exercise on quality of life in women with breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. J Res Health Sci. 2016;16:127–32. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.van de Wiel HJ, Stuiver MM, May AM, van Grinsven S, Aaronson NK, Oldenburg HSA, et al. Effects of and lessons learned from an internet-based physical activity support program (With and without physiotherapist telephone counselling) on physical activity levels of breast and prostate cancer survivors: the pablo randomized controlled trial. Cancers. 2021. 10.3390/cancers13153665. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 83.Winkels RM, Sturgeon KM, Kallan MJ, Dean LT, Zhang Z, Evangelisti M, et al. The women in steady exercise research (WISER) survivor trial: the innovative transdisciplinary design of a randomized controlled trial of exercise and weight-loss interventions among breast cancer survivors with lymphedema. Contemp Clin Trials. 2017. 10.1016/j.cct.2017.07.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 84.Bail JR, Fruge AD, Cases MG, De Los Santos JF, Locher JL, Smith KP, et al. A home-based mentored vegetable gardening intervention demonstrates feasibility and improvements in physical activity and performance among breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2018. 10.1002/cncr.31559. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 85.Scott E, Daley AJ, Doll H, Woodroofe N, Coleman RE, Mutrie N, et al. Effects of an exercise and hypocaloric healthy eating program on biomarkers associated with long-term prognosis after early-stage breast cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer Causes Control : CCC. 2013. 10.1007/s10552-012-0104-x. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 86.Thorsen L, Skovlund E, Strømme SB, Hornslien K, Dahl AA, Fosså SD. Effectiveness of physical activity on cardiorespiratory fitness and health-related quality of life in young and middle-aged cancer patients shortly after chemotherapy. J Clin Oncol. 2005. 10.1200/JCO.2005.04.106. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 87.Ho M, Ho JWC, Fong DYT, Lee CF, Macfarlane DJ, Cerin E, et al. Effects of dietary and physical activity interventions on generic and cancer-specific health-related quality of life, anxiety, and depression in colorectal cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surv: Res Pract. 2020. 10.1007/s11764-020-00864-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 88.Vallance JK, Nguyen NH, Moore MM, Reeves MM, Rosenberg DE, Boyle T, et al. Effects of the ACTIVity And TEchnology (ACTIVATE) intervention on health-related quality of life and fatigue outcomes in breast cancer survivors. Psycho-Oncology. 2020. 10.1002/pon.5298. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 89.Wang LF, Eaglehouse YL, Poppenberg JT, Brufsky JW, Geramita EM, Zhai S, et al. Effects of a personal trainer-led exercise intervention on physical activity, physical function, and quality of life of breast cancer survivors. Breast cancer (Tokyo, Japan). 2021. 10.1007/s12282-020-01211-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 90.Park J-H, Lee J, Oh M, Park H, Chae J, Kim D-I, et al. The effect of oncologists' exercise recommendations on the level of exercise and quality of life in survivors of breast and colorectal cancer: a randomized controlled trial. Cancer. 2015. 10.1002/cncr.29400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 91.Brown JC, Damjanov N, Courneya KS, Troxel AB, Zemel BS, Rickels MR, et al. A randomized dose-response trial of aerobic exercise and health-related quality of life in colon cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology. 2018. 10.1002/pon.4655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 92.Blair CK, Harding E, Wiggins C, Kang H, Schwartz M, Tarnower A, et al. A home-based mobile health intervention to replace sedentary time with light physical activity in older cancer survivors: randomized controlled pilot trial. JMIR Cancer. 2021. 10.2196/18819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 93.Galiano-Castillo N, Cantarero-Villanueva I, Fernández-Lao C, Ariza-García A, Díaz-Rodríguez L, Del-Moral-Ávila R, et al. Telehealth system: a randomized controlled trial evaluating the impact of an internet-based exercise intervention on quality of life, pain, muscle strength, and fatigue in breast cancer survivors. Cancer. 2016. 10.1002/cncr.30172. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 94.Golsteijn RHJ, Bolman C, Volders E, Peels DA, de Vries H, Lechner L. Short-term efficacy of a computer-tailored physical activity intervention for prostate and colorectal cancer patients and survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Behav Nutr Phys Act. 2018. 10.1186/s12966-018-0734-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 95.Holtdirk F, Mehnert A, Weiss M, Mayer J, Meyer B, Brode P, et al. Results of the Optimune trial: a randomized controlled trial evaluating a novel Internet intervention for breast cancer survivors. PLoS One. 2021. 10.1371/journal.pone.0251276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 96.McNeil J, Brenner DR, Stone CR, O'Reilly R, Ruan Y, Vallance JK, et al. Activity tracker to prescribe various exercise intensities in breast cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019. 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001890. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 97.Willems RA, Bolman CAW, Mesters I, Kanera IM, Beaulen AAJM, Lechner L. Short-term effectiveness of a web-based tailored intervention for cancer survivors on quality of life, anxiety, depression, and fatigue: randomized controlled trial. Psycho-oncology. 2017. 10.1002/pon.4113. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 98.Vallance JK, Courneya KS, Plotnikoff RC, Dinu I, Mackey JR. Maintenance of physical activity in breast cancer survivors after a randomized trial. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2008. 10.1249/mss.0b013e3181586b41. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 99.Singleton AC, Raeside R, Partridge SR, Hyun KK, Tat-Ko J, Sum SCM, et al. Supporting women’s health outcomes after breast cancer treatment comparing a text message intervention to usual care: the EMPOWER-SMS randomised clinical trial. J Cancer Surviv. 2022. 10.1007/s11764-022-01209-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 100.Kim SH, Shin MS, Lee HS, Lee ES, Ro JS, Kang HS, et al. Randomized pilot test of a simultaneous stage-matched exercise and diet intervention for breast cancer survivors. Oncol Nurs Forum. 2011. 10.1188/11.ONF.E97-E106. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 101.Mardani A, Pedram Razi S, Mazaheri R, Haghani S, Vaismoradi M. Effect of the exercise programme on the quality of life of prostate cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Pract (John Wiley & Sons, Inc.). 2021. 10.1111/ijn.12883 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 102.McGowan EL, North S, Courneya KS. Randomized controlled trial of a behavior change intervention to increase physical activity and quality of life in prostate cancer survivors. Annals Behav Med: a Publication Soc Behav Med. 2013. 10.1007/s12160-013-9519-1. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 103.Short CE, James EL, Girgis A, D'Souza MI, Plotnikoff RC. Main outcomes of the Move More for Life Trial: a randomised controlled trial examining the effects of tailored-print and targeted-print materials for promoting physical activity among post-treatment breast cancer survivors. Psycho-oncology. 2015. 10.1002/pon.3639. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 104.Vallerand JR, Rhodes RE, Walker GJ, Courneya KS. Feasibility and preliminary efficacy of an exercise telephone counseling intervention for hematologic cancer survivors: a phase II randomized controlled trial. J Cancer Surviv: Res Pract. 2018. 10.1007/s11764-018-0675-y. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 105.von Gruenigen VE, Gibbons HE, Kavanagh MB, Janata JW, Lerner E, Courneya KS, et al. A randomized trial of a lifestyle intervention in obese endometrial cancer survivors: quality of life outcomes and mediators of behavior change. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2009. 10.1186/1477-7525-7-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 106.Kim JY, Lee MK, Lee DH, Kang DW, Min JH, Lee JW, et al. Effects of a 12-week home-based exercise program on quality of life, psychological health, and the level of physical activity in colorectal cancer survivors: a randomized controlled trial. Support Care Cancer : official J Multinat Assoc Support Care Cancer. 2019. 10.1007/s00520-018-4588-0. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 107.Morey MC, Snyder DC, Sloane R, Cohen HJ, Peterson B, Hartman TJ, et al. Effects of home-based diet and exercise on functional outcomes among older, overweight long-term cancer survivors: RENEW: a randomized controlled trial. JAMA. 2009. 10.1001/jama.2009.643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 108.Reeves MM, Terranova CO, Winkler EAH, McCarthy N, Hickman IJ, Ware RS, et al. Effect of a remotely delivered weight loss intervention in early-stage breast cancer: randomized controlled trial. Nutrients. 2021. 10.3390/nu13114091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 109.Ligibel JA, Meyerhardt J, Pierce JP, Najita J, Shockro L, Campbell N, et al. Impact of a telephone-based physical activity intervention upon exercise behaviors and fitness in cancer survivors enrolled in a cooperative group setting. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2012. 10.1007/s10549-011-1882-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 110.Reeves M, Winkler E, McCarthy N, Lawler S, Terranova C, Hayes S, et al. The Living Well after Breast Cancer TM Pilot Trial: a weight loss intervention for women following treatment for breast cancer. Asia Pac J Clin Oncol. 2017. 10.1111/ajco.12629. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 111.Chang Y-L, Tsai Y-F, Hsu C-L, Chao Y-K, Hsu C-C, Lin K-C. The effectiveness of a nurse-led exercise and health education informatics program on exercise capacity and quality of life among cancer survivors after esophagectomy: a randomized controlled trial. Int J Nurs Stud. 2020. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2019.103418. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 112.Rogers LQ, Hopkins-Price P, Vicari S, Pamenter R, Courneya KS, Markwell S, et al. A randomized trial to increase physical activity in breast cancer survivors. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009. 10.1249/MSS.0b013e31818e0e1b. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 113.Livingston PM, Salmon J, Courneya KS, Gaskin CJ, Craike M, Botti M, et al. Efficacy of a referral and physical activity program for survivors of prostate cancer [ENGAGE]: rationale and design for a cluster randomised controlled trial. BMC Cancer. 2011. 10.1186/1471-2407-11-237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]