Abstract

Objective

The present study aimed to synthesize flavone hybrids with 3-methoxy substitution and an N-heterocyclic ring at the 4ʹ position of the flavone B ring and test their effectiveness against cancer.

Method

Molecular docking of 3-methoxy flavone was studied on ER-α and EGFR. By cyclizing chalcones, various flavonol derivatives were synthesized and 3-methoxy flavones were produced by flavonol methylation. 3-methoxy flavone derivatives substituted with various heterocyclic rings like morpholine, piperidine, N-methyl piperazine, pyrrolidine, triazole, imidazole, and benzimidazole were synthesized. 1HNMR, 13CNMR, IR, and mass spectra verified all compound’s structures. 3-methoxy flavone derivatives evaluated for their anticancer potential by MTT assay and SRB assay on breast cancer (MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231). The molecular dynamics simulation was also studied for active compounds on the human estrogen receptor alpha and epidermal growth factor receptor.

Results

3-methoxy flavone derivatives were successfully synthesized and evaluated by spectroscopic studies. The MTT assay on MCF-7 cell lines revealed significant cytotoxic activity of compounds Ciii and Civ by expressing IC50 values of 13.08 ± 1.80 and 20.3 ± 1.47 µg/ml, respectively. The SRB assay on MDA-MB-231 showed a potent response by compounds Cii, Cv & Cvi with IC50 values of 5.54 ± 1.57, 5.44 ± 1.66 and 8.06 ± 1.83 µg/ml, respectively. Overall results showed the effective substitution of 3-methoxy flavone was N-methyl piperazine and piperidine in all cell lines, while triazole substitution was effective in MDA-MB-231 cells. Molecular dynamics study proved the stability of synthesized compounds’ ligands-protein complexes. The structure–activity relationship of flavone derivatives suggests the electron donating group increases the anticancer activity of derivatives in MDA-MB-231, while the same is not reflected in MCF-7 cell lines.

Conclusion

This study provides a foundation for designing flavone derivatives with N-heterocyclic ring incorporation as anticancer medicines.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12672-025-02491-6.

Keywords: 3-Methoxy flavone, Flavonol, Breast cancer, MCF-7, MDA-MB-231

Introduction

Worldwide, cancer has become one of the major causes of death and a prime obstacle in increasing life expectancy [1]. The NCRP records in India reveal varying percentage of individuals with advanced stages of various cancer types. Breast: 57.6%, cervix: 60.0%, Head and neck: 66.6% and stomach: 50.8%. It also observed a gender-based record of distant metastasis in lung cancer, with 44.0% occurring in males and 47.6% in females [2]. Both males and females are prone to developing malignancies. In females, common malignancies occur in the breast, cervix, and lung, while in males prostate and colon cancers are common [3]. With growing incidences of cancer, it is important to put efforts into developing novel anticancer therapy that can selectively target cancerous cells and effectively inhibit the proliferation of cancerous cells. Many epidemiological studies proved the importance of the inclusion of flavonoid-rich fruits and vegetables in reducing the risk of chronic diseases, including cancer. Researchers were drawn to natural agents for their potential to target cancer due to their chemical diversity, lack of side effects, easy availability and affordability [4]. Flavonoids are polyphenolic secondary metabolites ubiquitously present in colored fruits and vegetables. Green leafy vegetables and colored fruits have a rich source of flavonoids. Plants such as yellow onion, parsley, aubergines, blackberries, apples, curly kale, cherry tomatoes, curly kale, and tea are rich in flavonoids [5].

Flavonoids are valuable secondary metabolite due to their important medicinal properties; including their potential to inhibit cancer. Flavonoids have beneficial properties including suppression of cell cycle, inhibition of cancer cell growth, induction of apoptosis and antioxidant activity all of which significantly reducing cancer progression and metastasis [6]. Conventional anticancer agents cause systemic toxicity. Combining flavonoid therapy with other chemotherapeutic agents can reduce the dose and toxicity associated with conventional therapy. Researchers extensively studied different flavonoids from various plants to explore their anticancer potential. They also studied the anticancer potential of synthetic flavones [7]. Figure 1 enlists the different flavonoids specifically have anticancer potential in treating breast cancer. These are quercetin, luteoline, kaempferol, morin, nobiletin, apigenin and baicalin. These flavonoids participate in cellular processes like cell cycle progression, programmed cell death, proliferation and angiogenesis. In addition to this flavonoids have antioxidant activity which allows their use in many diseases [8, 9]. The C ring of flavone structure, chemically known as pyran ring, has two crucial functions for anticancer potential: double bonds and carbonyl [10]. While exploring the anticancer potential of flavone derivatives, we observed that some aminoflavone and methoxyflavone compounds demonstrated good activity against breast cancer [11–13]. An amino group is present at 3 or 4 or both 3 and 4 position in the B ring of an amino-flavone. Like flavonoids, these amino-flavone demonstrated their anticancer potential by multi-targeting various pathways [14].

Fig. 1.

Basic structure of flavonoid and some important flavonoids used in breast cancer

Polyphenolic compounds like flavonoids have shown immense promise as cytoprotective agents in cancer cell line studies. Flavonoids have substantial anticancer potential against breast cancer. Fortunately, flavonoids fail to demonstrate anticancer action in living organism. The flavonoids have many hydroxyl groups (quercetin, kampferol, apigenin, morin, luteolin etc.) at different positions, in which 5 and 7 positions are the most common. Due to the presence of hydroxyl group, they extensively undergo phase II metabolism. The bioavailability of polyhydroxy flavonoids decreases due to their rapid metabolism; therefore, they fail to express anticancer potential in vivo. When the hydroxyl groups of the polyphenolic flavonoids are capped with a methoxy group, they dramatically improve oral bioavailability, due to resistance to metabolism. The metabolic stability, oral bioavailability and chemo-preventive characteristics of flavonoids were greatly improved by methylating their hydroxyl groups. The natural polymethoxy flavonoid observed in citrus species mentioned in Fig. 1 is nobiletin. The various studies conducted on nobiletin prove its potency in breast cancer. According review on methoxylated flavones, published by Walle, it was suggested that flavonoids with fewer methoxy group and no hydroxyl groups have been much less studied [15]. Therefore, in the present research work, we have synthesized flavonoids with less methoxy and no hydroxyl groups.

Literature revealed the importance of flavonoids in treating breast cancer [9]. Risk of breast cancer is increased in women who have high level of estrogen. Among the two major types of estrogen receptor, estrogen receptor α (ER-α) and estrogen receptor β (ER-β), ER-α abnormally expressed in breast cancer patient. Indeed, the inhibition of ER-α has become a major strategy in preventing and treating breast cancer, especially in cases where the cancer is estrogen receptor positive [16]. Another type of breast cancer is triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC), which lacks the expression of estrogen, progesterone and human epidermal growth factor. When it comes to TNBC breast cancer, is regarded as challenging and aggressive subtype. TNBC may exhibit overexpression of epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) [17, 18]. Flavonoid subclasses have proved their anticancer potential on hormone related breast cancer and triple negative breast cancer [19, 20]. Modifying the structure of flavonoids is a promising strategy to develop new molecules with improved anti-cancer properties against breast cancer with reduction in potential side effects.

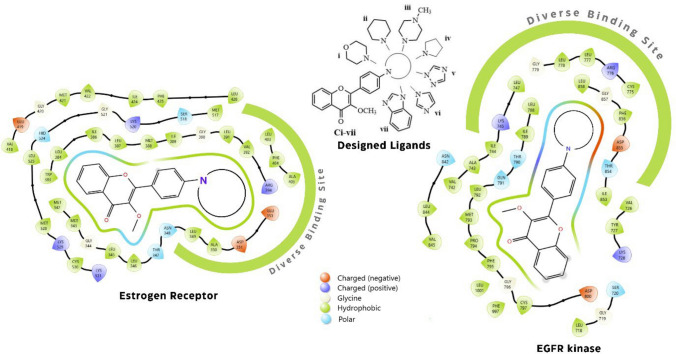

Nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds are crucial in medicines due to their several significant pharmacological actions. N-containing heterocyclic compounds potentiate the anticancer effect by acting through different mechanism [21]. Heterocyclic compounds have demonstrated encouraging anti-breast cancer potential [22–24]. Dietary flavonoids avoid the risk of breast cancer, as well as epidemiological studies have proved their remarkable anticancer potential against breast cancer [9]. Aminoflavone (amino substitutions basically present on the 3 or 4 position of B ring of flavone) induces apoptosis in breast cancer cells [25]. As mentioned above, nitrogen-containing heterocyclic compounds potentiate anticancer effect; therefore, if nitrogen of aminoflavone introduced into heterocyclic ring, it may potentiate the anticancer activity of the flavone derivative. Figure 2 shows the designing of the 3-methoxy flavone derivatives with their possible interactions with estrogen and EGFR receptor binding pocket.

Fig. 2.

Rational behind Design of 3-methoxy flavone derivative with N-heteroaryl substitution

By considering the importance of aminoflavones and methoxyflavones, in this research work, we have synthesized flavone hybrids that have 3-methoxy substitution and amino nitrogen as a part of the heteroaryl ring. The 4th position of the B ring of the 3-methoxy flavone is substituted with a variety of heteroaryl rings, including morpholine, piperidine, pyrrolidine, benzimidazole, imidazole, triazole, and piperazine, and we tested them against breast cancer. The novel 3-methoxy flavone derivative’s binding interactions were studied on the ER-α and EGFR receptor. Since the MCF-7 cell line is known to express high amounts of ER-α, it is a useful model that is frequently utilized in studies of hormone related breast cancer. The same cell lines are used to study action of flavone derivatives to target hormone related breast cancer [19]. ER negative cell line, MDA-MB-231 overexpress EGFR receptor. The synthesized flavone derivatives were studied on the MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines.

Materials and methods

Reagents and chemicals required for the present study were procured from Loba-Chem, Spectrochem, and Sigma-Aldrich by considering their availability. The digital melting point equipment was used to determine melting points. Shimadzu IRAffinity-1S Spectrometer was used to obtain FTIR spectra in the range 4000–450 cm−1. The mass spectra were detected using a XEVO G2-XS QTOF mass spectrometer. Bruker Avance Neo 500 MHz spectrometers were used to record 1H and 13C NMR spectra.

Prediction of ADME

The Lipinski rule of five (Ro5) was used to assess the drug-likeness of each of the seven 3-methoxy flavone derivatives. This rule is used to evaluate drug-likeness of molecules based on their physicochemical properties. The aim is to figure out favorable pharmacokinetic properties. The important Lipinski rule of five parameters includes molecular weight, lipophilic character, hydrogen bond donor, hydrogen bond acceptor, and rotatable bond. The free web program SwissADME is designed to predict various pharmacokinetic and drug-likeness properties of chemical compounds. The information obtained from the program can be useful in early stages of drug discovery and development.

Molecular docking

This research paper explains the interaction of synthesized 3-methoxy flavone derivatives in the binding pocket of the human estrogen receptor alpha (ER-α) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR). ER-α and EGFR, target protein cocrystallized structures, were captured from protein data bank. PDB:2IOG, having resolution 1.60A° and PDB:3W2S, having resolution 1.90A°, were selected for the computational study. For selected PDB:2IOG and PDB:3W2S, the control ligand identified were IOG and W2R. A series of flavone derivatives, standard ligands and the anticancer drug 5-fluorouracil were docked in the binding site of the target protein. The structural optimization and minimization of proteins were performed using CHIMERA v1.16 [26], incorporating force fields for both standard (AMBER ff14SB) and nonstandard residues (AM1-BCC); consequently, all nonstandard residues, like water molecules & cocrystal ligands, and unnecessary chains have been removed from the proteins. AutoDockTools 1.5.6 [27], Chimera 1.11, and Maestro Version 12.7.161 were employed for grid Generation and validation. Grid parameters were obtained using orientation of the cocrystal ligand or the CASTp [28] server if protein in Apo state. Ligands structures were drawn in chemdraw imported into MarvinSketch, where they underwent 2D and 3D cleaning. Cleaned Structures were then subjected to the MMFF94 force field for minimization, and the lowest energy conformer was selected for further study in MOL2 format. After obtaining the ligands and proteins, their structures were converted to pdbqt format, using an in-house bash script made using AutoDock tools 1.5.6 for ligand and ADFRsuit for proteins, in which all the rotatable bonds of ligands were allowed to rotate freely, and the receptor were considered rigid. For docking studies, we used the AutoDock Vina 1.2.3 [29]. The spacing between the grid points was kept 0.375˚A. The grid box was centered on the active site of the target with allowing the program to search for additional places of probable interactions between the ligands and the receptor. Other configurations were considered default. The XYZ coordinates as a table no. 3 other parameters like CPU were set for 23, exhaustiveness was 32, the number of modes was 9 and the energy range was set for 3. Redockings were performed with the same configurations of the previously performed dockings. Results obtained after Autodock Vina processing were subjected to make a complex using Biovia Discovery Studio visualizer.

Synthesis

The cyclization of chalcones Ai-vii yielded 3-hydroxy flavone Bi-vii and on methylation of 3-hydroxy flavone yield 3-methoxy flavone Ci-vii derivatives as depicted in Fig. 3. We used the same method described in our previous study to synthesize chalcones derivatives [30, 31].

Fig. 3.

Scheme of synthesis of 3-methoxy flavone Ci-vii derivatives

General procedure for synthesis of 3-hydroxy flavone (Flavonol) derivatives (Bi-vii)

Dissolution of finely powdered (0.01 mol) chalcone was done by sonicating it in a mixture of ethanol (60 ml) and 20% aqueous sodium hydroxide (30 ml). Sonication was continued until the lumps of chalcone were completely dispersed in solution. The reaction mixture was cooled by keeping it in a freezing mixture of salt and ice. 30% hydrogen peroxide (10 ml) was added dropwise in a chilled reaction mixture with constant stirring. We continued adding hydrogen peroxide for 30 min. The stirring was continued for a further 3 h at room temperature. Then the reaction mixture was kept in the refrigerator overnight. The product was isolated by adding chilled 5N hydrochloric acid. The product was recrystallized from ethanol [32].

General procedure for synthesis of 3-methoxy flavone derivatives (Ci-vii)

0.01 mol of flavonol (Bi-vii), synthesized in the previous step, was dispersed in dry acetone (250 ml). Dimethyl sulphate (0.02 mol) and dry potassium carbonate (0.03 mol) were added consecutively. The mixture was refluxed for 24 h with stirring. The progress of reaction was monitored by TLC. After completion of the reaction, acetone evaporated under reduced pressure. The obtained residue was diluted with water. The precipitate was filtered and recrystallized from the methanol-chloroform (8:2) mixture [33, 34].

Biological evaluation

Anti-tumor activity against human cancer cell lines

3-methoxy flavone derivatives’ anticancer potential was tested on MCF-7 (ER+ve breast cancer cell lines) and MDA-MB-231 (triple negative breast cancer cell lines). MTT assay was performed on MCF-7 cells while SRB assay was performed on MDA-MB-231 cells.

MTT assay

In 96-well microtiter plate, MCF-7 cells were grown at density of 1 × 104 cells/ml at ambient temperature and atmosphere (37 °C and 5% CO2) for 24 h. For seeding, 100 μl diluted cell suspension was added in 100 μl culture medium. Solutions of compounds were made by dissolving them in DMSO. Different concentrations were made by diluting the solution. After 24 h of incubation, different concentrations of sample solutions were added in triplicate into microtiter plate. Following the addition of sample solution, the plate was incubated for 24 h at ambient temperature 37 °C and atmosphere 5% CO2. After incubation, the medium was removed, 20 μl of MTT reagent was added and kept again for 4 h of incubation with the same atmospheric condition mentioned. The purple color was developed due to formation of formazan. DMSO was added to dissolve the formazan. The colour intensity was measured by microplate reader Benespera E21 at wavelength of 550 nm [35].

SRB assay

100 µl of cell suspension of 5000 cells was added to each well of 96 microtiter plate. Further, the plate was incubated for 24 h at 37 °C, 5% CO2, 95% air, and 100% relative humidity. A stock solution of flavone derivatives was prepared by dissolving them in DMSO. Sample solutions were diluted to make different concentrations. 10 µl of these different sample solutions were added to respective microtiter well. After addition of sample solution, the plates were incubated for next 48 h. After incubation the fixation of cells was done by cold trichloroacetic acid. Further, the cells were properly washed and dried. Sulforhodamine B (SRB) solution in 1% acetic acid was added in each well and kept at room temperature for 20 min. Optical density was measured at 510 nm [36].

Molecular dynamics simulation

The docking complexes of 2IOG (Human estrogen receptor alpha) in the Apo state (2IOG_Apo), with the cocrystal ligand IOG (2IOG_IOG), the biological activity standard 5-fluorouracil (2IOG_5-Fluorouracil), and test compounds ciii and civ (2IOG_Ciii and 2IOG_Civ), alongside 3W2S (EGFR kinase) in the Apo state (3W2S_Apo), with the cocrystal ligand (3W2S_2WR), the biological activity standard 5-fluorouracil (3W2S_5-Fluorouracil), and test compounds Cii, Cv, and Cvi (3W2S_Cii, 3W2S_Cv, and 3W2S_Cvi) were analyzed using molecular dynamics simulations on Desmond 2020. The system was established utilizing the OPLS-2005 force field and the explicit solvent model incorporating SPC water molecules within a periodic border solvation box measuring 10 × 10 × 10. To replicate the environment of living creatures, 0.15 M NaCl solutions were incorporated into the system to neutralize the charge. The protein–ligand complexes were retrained after the system was equilibrated with an NVT ensemble for 10 ns. Subsequently, following the prior phase, an NPT ensemble was employed for a brief equilibration and minimization run lasting 12 ns. The Nose–Hoover chain coupling method was employed to build the NPT ensemble, maintaining a temperature of 27 °C, a relaxation period of 1.0 ps, and a pressure of 1 bar across all simulations. The time interval was established at 2 femtoseconds. We utilized a barostat approach for pressure regulation, incorporating a relaxation period of 2 ps, as per the Martyna–Tuckerman–Klein chain coupling system. Long-range electrostatic interactions were computed via the particle mesh Ewald method, utilizing a Coulomb interaction radius of 9 Å. All bonded forces of the trajectory were calculated using the RESPA integrator with a time step of 2 fs. The 2IOG_Apo, 2IOG_IOG, 2IOG_5-Fluorouracil, 2IOG_Ciii, 2IOG_Civ, 3W2S_Apo, 3W2S_2WR, 3W2S_5-Fluorouracil, 3W2S_Cii, 3W2S_Cv, and 3W2S_Cvi underwent a final manufacturing run lasting 100 ns. The final production run was executed at a pace of 100 ns per unit. To assess the consistency of the MD, we calculated the root mean square deviation (RMSD), radius of gyration (Rg), root mean square fluctuation (RMSF), and the number of hydrogen bonds (H-bonds). The stability was monitored using simulations.

Analysis of binding free energy

The molecular mechanics and generalized Born surface area approach, known as MM-GBSA, was employed to calculate the binding free energies of 2IOG_IOG, 2IOG_5-Fluorouracil, 2IOG_Ciii, 2IOG_Civ, 3W2S_2WR, 3W2S_5-Fluorouracil, 3W2S_Cii, 3W2S_Cv, and 3W2S_Cvi. The Python script thermal mmgsba.py, in conjunction with the VSGB solvation model and the OPLS_2005 force field, was employed to compute the MM-GBSA binding free energy using a one-step sample size across the final fifty frames of the simulation trajectory. The separate energy components of columbic, covalent, hydrogen bonding, van der Waals interactions, self-contact, lipophilicity, and ligand–protein solvation were combined through the principle of additivity to calculate the binding free energy of MM-GBSA (kcal/mol). To ascertain the cost of Gbind, input the subsequent numbers into the specified equation:

| 1 |

where ΔG_bind represents the binding free energy, ΔG_MM denotes the disparity between the free energies of ligand–protein complexes and the total energies of the isolated protein and ligand, ΔG_Solv indicates the difference in the G_SA solvation energies of the ligand-receptor complex and the aggregate of the solvation energies of the receptor and ligand in their unbound states, ΔG_SA signifies the difference in surface area energies for the protein and ligand.

Results and analysis

Table 1 summarizes the ADME properties of the 3-methoxy flavon derivatives. The intended derivatives Ci-CVii adhere to Lipinski’s rule of five and have acceptable ADME parameter values. It suggests that these compounds may have favorable characteristics for further development as potential drugs.

Table 1.

ADME prediction of Ci-Cvii

| Compound | Mol. Wt | Number of HBD | Number of HBA | MR | Log Po/w | Log S (ESOL) | Solubility (mg/ml) | Lipinski rule |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ci | 321.37 | 0 | 4 | 100.14 | 3.23 | − 4.40 | 1.34E−02 | Yes; 0 violation |

| Cii | 335.40 | 0 | 3 | 103.86 | 3.51 | − 5.16 | 2.34E−03 | Yes; 0 violation |

| Ciii | 350.41 | 0 | 4 | 110.67 | 3.46 | − 4.58 | 9.31E−03 | Yes; 0 violation |

| Civ | 320.38 | 0 | 3 | 96.49 | 3.65 | − 5.73 | 6.03E−04 | Yes; 0 violation |

| Cv | 319.31 | 0 | 5 | 89.33 | 2.84 | − 4.22 | 5.99E−05 | Yes; 0 violation |

| Cvi | 318.33 | 0 | 4 | 91.53 | 2.87 | − 4.22 | 5.99E−05 | Yes; 0 violation |

| Cvii | 368.38 | 0 | 4 | 57.26 | 3.32 | − 5.45 | 1.32E−03 | Yes; 0 violation |

Mol. Wt. Molecular weight, HBD hydrogen bond donor, HBA hydrogen bond acceptor, MR molar refractivity, Log Po/w octanol/water partition coefficient, Log S aqueous solubility

Table 2 displays the results of the docking study of 3-methoxy flavone derivatives in the binding pocket of the ER-α and EGFR receptors. 5-Flurouracil, when compared with the other flavone derivatives, exhibited higher binding energy at both receptors. The designed compounds docking scores were found similar to those of the control ligand IOG and 2WR of ER-α and EGFR, respectively. The binding energy of the IOG was found to be − 12.84 kcal/mol for ER-α. The compound Cii, complexed in binding site of ER-α observed lowest binding energy − 10.14 kcal/mol. Similarly, in EGFR receptor docking, Cvi and Cvii expressed a docking score of 9.42 kcal/mol, while control ligand 2WR expressed a docking score of − 11.48 kcal/mol.

Table 2.

Docking results of compounds Ci-Cvii on human estrogen receptor alpha (ER-α) and epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR)

| Compound code | 2IOG | 3W2S | Binding interactions of ligands with 2IOG | Binding interactions of ligands with 3W2S | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Binding energy kcal/mol | H Bonding | Pi-alkyl interactions | H Bonding | Pi-alkyl interactions | ||

| Ci | − 9.51 | − 9.17 | – | Met343, Leu525, Leu346, Phe404, Leu391, Ala350 | – | Leu777, Leu788, Leu844, Ala743, Leu718 |

| Cii | − 10.14 | − 9.04 | – | Leu387, Leu391, Phe404, Ala350, Leu346, A525, Met343, Met528 | – | Leu788, Leu777, Ala743, Leu844, Leu718 |

| Ciii | − 8.65 | − 8.18 | – | Val418, Met421, Leu525, Ala350, Leu391 | – | Ala743, Leu844, Val726 |

| Civ | − 9.22 | − 9.37 | – | Leu391, Ala350, Leu346, Leu525, Met343, Cys530, Leu387, Phe404 | – | Leu788, Leu777, Ala743, Leu844, Leu718 |

| Cv | − 9.75 | − 8.93 | Arg394 | Ala350, Leu346, Leu525, Met343 | – | Leu788, Leu718, Ala743, Val726, Leu718, Leu844 |

| Cvi | − 9.63 | − 9.42 | – | Leu346, Ala350, Leu391, Leu525, Met343 | – | Leu777, Leu788, Val726, Ala343, Leu844, Leu718 |

| Cvii | − 9.22 | − 9.42 | – | Val418, Met421, Leu525, Leu346, Leu391, Leu387 | – | Leu718, Leu844, Val726, Ala743, leu777, Leu788 |

| IOG | − 12.84 | NA | Glu353, Leu387, Arg394 | Leu536, Leu354, Ala350, Phe425, Leu346, Leu391, Met421, Val418 | NA | NA |

| 2WR | NA | − 11.48 | NA | NA | Arg841, Lys745, Met793, Gly857, Phe856 | Phe723, Ala859, Met766, Val726, Leu788, Ala743 |

| 5-FU | − 4.88 | − 5.07 | Ala350, Glu353, Arg394 | Leu391 | Asp855, Phe856 | Leu777 |

5-flurouracil used as a positive control; 2IOG, target for estrogen receptor alpha (ER-α); 3W2S, target for epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR); IOG, standard cocrystalized ligand of 2IOG; 2WR, standard cocrystalized ligand of 3W2S

In the docking study, we investigated comparative structural binding and conformational analysis of proteins 2IOG and 3W2S with cocrystal ligands and synthesized compounds. Figure 4A presents the 3D structure of protein 2IOG with compound Cii, represented by the pink and cocrystal ligand IOG represented by orange color, while Fig. 4B represents the 3D structure of protein 3W2S with Cvi (pink color) and cocrystal ligand 2WR (orange color) fits snugly within the active site, indicating a strong ligand–protein interaction. This is further supported by the 2D interaction diagram on the right, where various amino acids make critical interactions with the ligand. These interactions primarily involve hydrogen bonding and hydrophobic interactions, essential for the stability of the ligand–protein complex. Notably, the spatial arrangement of these residues around the ligand suggests a tight and specific binding, which indicates that compounds and cocrystal ligands interact with the same binding site of the protein, which is a crucial factor for the compound’s biological property.

Fig. 4.

Comparative binding interaction analysis of overlay of best-interacting ligand with protein. A Structural overlay of compound Cii with protein 2IOG on cocrystal ligand IOG with 2IOG, B Structural overlay of compound Cvi with protein 3W2S on cocrystal ligand 2WR with 3W2S

Synthesis of chalcone was carried out by base-catalyzed Claisen-Schmidt condensation of 2-hydroxyacetophenone and substituted benzaldehyde of N-heterocyclic compounds. Substituted benzaldehyde of N-heterocyclic compounds was obtained by Nucleophilic aromatic substitution (SNAr) of haloarenes with amines. To produce flavonol, chalcone was cyclized in the presence of alkaline hydrogen peroxide. Finally, on methylation of flavonol, we had synthesized 3-methoxy flavone. The output of various structure elucidation techniques is mentioned below.

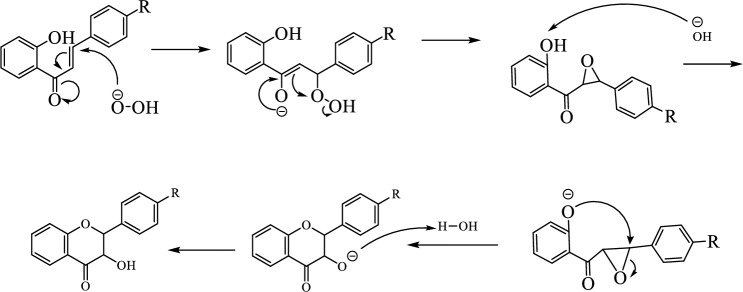

Mechanism behind synthesis of 3-methoxy flavones derivatives

Step 1: Synthesis of 3-hydroxy flavone (flavonol) derivatives (Bi-vii)

This is the Algar–Flynn–Oyamada (AFO) reaction, in which a chalcone undergoes oxidative cyclization to form a flavonol. Hydrogen peroxide acts as an oxidizing agent, and sodium hydroxide acts as a base. NaOH deprotonates chalcone, which facilitates nucleophilic attack necessary for further cyclization. The alpha hydrogen adjacent to the carbonyl group is acidic. Under the basic condition, chalcones undergo deprotonation and form the corresponding conjugate base (enolate ion). The enolate is resonance-stabilized. Negative charge delocalized into the carbonyl oxygen makes it more nucleophilic. The nucleophilic oxygen in the enolate attacks the electrophilic oxygen of H2O2, leading to the formation of a peroxy-oxygen bond, known as a peroxide intermediate. The peroxy intermediate undergoes cyclization, where the oxygen atom from the peroxy group attaches to the adjacent carbon to form a three-membered epoxide ring. Cyclization occurs due to the strain and instability of the peroxy intermediate, which favours stable epoxide formation. Epoxide is reactive. The next step involves the abstraction of a proton from phenolic OH to form the most stable phenoxide ion. The phenoxide ion undergoes a nucleophilic attack on the epoxide, resulting in the ring opening of the epoxide and the formation of a new bond between the oxygen of the phenoxide and the carbocation generated from the epoxide.

Formation of Peroxide Anion: NaOH deprotonates H2O2, forming the peroxide anion (OOH⁻), a stronger nucleophile than H2O2 itself.

Attack of peroxide, formation of epoxide through nucleophilic attack and rearrangement to Flavone

Step-II Synthesis of 3-methoxyflavone derivatives (Ci-vii)

In the second step, 3-hydroxyflavones are converted to 3-hydroxyflavones using carbonate and dimethyl sulphate in acetone. Dimethyl sulfate is a highly reactive methylating agent used to methylate phenols, amines, and thiols. The hydroxyl group of chromone is deprotonated by potassium carbonate, forming the oxide ion, which is a more nucleophilic species. The nucleophile attacks one of the methyl groups of dimethyl sulfate, a good methylating agent. This is bimolecular nucleophilic substitution where the oxide ion attacks the sulfur atom, displacing one of the methoxy groups. Acetone, as a polar aprotic solvent, promotes the SN2 Reaction faster than the other. Finally, a methyl ether derivative is formed, which is less reactive.

3-Methoxy-2-(4-morpholinophenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one (Ci)

Yellow solid, yield: 80%, mp: 143–147 °C, IR (KBr, cm−1): 2980 (C–H sp2), 2841 (C–H sp3), 2964 (C–H sp3), 1602(C=O), 1514 (C = C Ar), 1448 (C=C Ar), 1381(C–N), 1193(C–O), 746(C-H bending) (Figure S1a); 1HNMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.30 (t, 4H, J = 4.95 Hz, H-2ʺ & 6ʺ), δ 3.88 (t, 4H, J = 4.95 Hz, H-3ʺ & 5ʺ), 3.89 (s, 3H, H- OCH3), 6.97 (d, 2H, J = 7.15 Hz, H-3ʹ & 5ʹ), 7.37 (t, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz, H-6), 7.50 (d, 1H, J = 8.35 Hz, H-8), 7.63 (t, 1H, J = 7.75 Hz, H-7), 8.1 (d, 2H, J = 7.1 Hz, H-2' & 6'), 8.25 (d, 1H, J = 7.9 Hz, H-5) (Figure S1b); 13CNMR (400 MHz, CDCl3): δ 47.88 (C-2ʺ & 6ʺ), 59.8 (C-OCH3), 66.65 (C-3ʺ & 5ʺ), 114.04 (C-3ʹ & 5ʹ), 117.81 (C-8), 121.71 (C-1ʹ), 124.24 (C-6), 125.72 (C-5), 129.86 (C-2ʹ & 6ʹ), 133.10 (C-7), 140.62 (C-3), 152.05 (C-4ʹ), 155.11 (C-2), 155.81 (C-8a), 174.80 (C-4) (Figure S1c); ESI MS ES+ (m/z): 338.20 [M+H]+, Anal. Calcd. for C20H19NO4, 337.1314 (Figure S1d).

3-Methoxy-2-(4-(piperidin-1-yl)phenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one (Cii)

Yellow solid, yield: 68%, mp: 100–104 °C, IR (KBr, cm−1): 2927 (C–H), 2864 (C–H), 2858 (C–H), 1595 (C=O), 1510 (C=C Ar), 1448 (C=C Ar), 1365 (C–N), 1193 (C–O), 744 (C-H bending) (Figure S2a); 1HNMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 1.70 (s, 6H, J = 4.5 Hz, H-3ʺ, 4ʺ & 5ʺ), 3.35 (s, 4H, J = 5.1 Hz, H-2ʺ & 6ʺ), 3.89 (s, 3H, H-OCH3), 6.97 (d, 2H, J = 8.75 Hz, H-3ʹ & 5ʹ), 7.36 (t, 1H, J = 7.45 Hz, H-6), 7.50 (d, 1H, J = 8.3 Hz, H-8), 7.63 (t, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz, H-7), 8.07 (d, 1H, J = 8.75 Hz, H-2ʹ & 6ʹ), 8.25 (d, 2H, J = 7.85 Hz, H- 5) (Figure S2b). 13CNMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 23.80 (C-4ʺ), 24.75 (C- 3ʺ & 5ʺ), 47.71 (C-2ʺ & 6ʺ), 59.05 (C-OCH3), 113.58 (C-3ʹ & 5ʹ), 118.02 (C-8), 123.41 (C-4a), 124.54 (C-6), 124.63 (C-5), 129.33 (C-2ʹ & 6ʹ), 133.38 (C-7), 139.30 (C-3), 146.34 (C-2), 152.50 (C-4ʹ), 154.32 (C-2), 155.23 (C-8a), 173.10 (C-4) (Figure S2c); TOF MS ES+ (m/z): 336.1353 [M+H]+, Anal. Calcd. for C21H21NO3, 335.1521 (Figure S2d).

3-Methoxy-2-(4-(4-methylpiperazin-1-yl)phenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one (Ciii)

Yellow crystalline solid, yield: 65%, mp: 173–176 °C, IR (KBr, cm−1): 3039 (C–H sp2), 2783 (C–H sp3), 1606 (C=O), 1521 (C=C Ar), 1460 (C=C Ar), 1384 (C–N), 1244 (C–O), 763 (C–H bending) (Figure S3a); 1HNMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.47 (s, 3H, H-CH3), 3.67 (d, 4H, H-3ʺ & 5ʺ), 3.78 (s, 4H, H-2ʺ & 6ʺ), 3.89 (s, 3H, H-OCH3), 7.04 (d, 2H, J = 9.5 Hz, H-3ʹ & 5ʹ), 7.39 (t, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz, H-6), 7.52 (d, 1H, J = 9.35 Hz, H-8), 7.66 (d, 1H, J = 7.1 Hz, H-7), 8.10 (d, 1H, J = 7.55 Hz, H-5), 8.12 (d, 2H, J = 9.05 Hz, H-2ʹ & 6ʹ) (Figure S3b); 13CNMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ, 45.04 (C-2ʺ & 6ʺ), 50.87 (C-3ʺ & 5ʺ), 53.98 (C-4ʺ), 59.8 (C-OCH3), 113.1 (C-3ʹ & 5ʹ), 118.2 (C-8), 123.43 (C-4a), 124.0 (C-6), 124.96 (C-5), 130.4 (C-2ʹ & 6ʹ), 133.4 (C-7), 140.1 (C-3), 154.8 (C-2), 155.4 (C-8a), 171.9 (C-4) (Figure S3c); ESI MS ES+ (m/z): 351.47 [M+H]+, Anal. Calcd. for C21H22N2O3, 350.1630 (Figure S3d).

3-Methoxy-2-(4-(pyrrolidin-1-yl)phenyl)-4H-chromen-4-one (Civ)

Orange crystalline solid, yield: 61%, mp: 185–187 °C, IR (KBr, cm−1): 3074 (C–H sp2), 2960 (C–H sp3), 2841 (C–H sp3), 1598 (C=O), 1516 (C=C Ar), 1448 (C=C Ar), 1355 (C–O), 756 (C-H bending) (Figure S4a);; 1HNMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 2.04 (s, 4H, H-3ʺ & 4ʺ), 3.37 (s, 4H, H-2ʺ & 5ʺ), 3.89 (s, 3H, H-OCH3), 6.64 (d, 2H, J = 9.00 Hz, H-3ʹ & 5ʹ), 7.36 (t, 1H, J = 7.35 Hz, H- 6), 7.54 (d, 1H, J = 8.4 Hz, H-8), 7.63 (t, 1H, J = 7.7 & 8.05 Hz, H-7), 8.17 (d, 2H, J = 8.9 Hz, H-2ʹ & 6ʹ), 8.22 (d, 1H, J = 8.0 Hz, H-5) (Figure S4b); 13CNMR (500 MHz, DMSO): 25.2 (C-3ʺ & 4ʺ), 47.8 (C-2ʺ & 5ʺ), 59.8 (C-OCH3), 113.0 (C-3ʹ & 5ʹ), 118.2 (C-8), 123.45 (C-4a), 124.1 (C-6), 130.4 (C-2ʹ & 6ʹ), 134.1 (C-7), 140.0 (C-3), 152.7 (C-4ʹ), 154.8 (C-2), 155.4 (C-8a), 171.9 (C-4) (Figure S4c); TOF MS ES+ (m/z): 322.12 [M+ H]+, Anal. Calcd. for C20H19NO3, 321.1365 (Figure S4d).

2-(4-(1H-1,2,4-Triazol-1-yl)phenyl)-3-methoxy-4H-chromen-4-one (Cv)

Dark yellow solid, yield: 71%, mp: 134–137 °C, IR (KBr, cm−1): 3115 (C–H sp2), 2914 (C–H sp3), 2850 (C–H sp2), 1614 (C=O), 1517 (C=C Ar), 1473 (C=C Ar), 1396 (C–N), 1217(C–O), 750 (Figure S5a); 1HNMR (500 MHz, DMSO): 3.99 (s, 1H, H-OCH3), 7.49 (s, 1H, J = 7.3 Hz, H-6), 7.81 (s, 2H, J = 6.45 Hz, H-7 & 8), 8.10 (m, 3H, J = 7.8 & 8.55 Hz, H-5, 2ʹ & 6ʹ), 8.30 (s, 1H, H-3ʺ), 8.27 (d, 2H, J = 7.65 & 8.8 Hz, 3ʹ & 5ʹ), 8.42 (s, 1H, J = 7.8 Hz, H-3ʺ), 9.44 (s, 1H, J = 7.5 Hz, H-5ʺ) (Figure S5b); 13CNMR (500 MHz, DMSO): 59.62 (C-OCH3), 118.32 (C-8), 119.01 (C-3ʹ & 5ʹ), 123.41 (C-4a), 124.68 (C-6), 124.80 (C-5), 129.39 (C-2ʹ & 6ʹ), 121.18 (C-1ʹ), 134.02 (C-7), 137.91 (C-3), 142.46 (C-5ʺ), 152.53 (C-3''), 153.61 (C-2), 154.57 (C-8a), 173.07 (C-4) (Figure S5c);; TOF MS ES+ (m/z): 320.0753 [M+H]+, Anal. Calcd. for C18H13N3O3, 319.0957 (Figure S5d).

2-(4-(1H-Imidazol-1-yl)phenyl)-3-methoxy-4H-chromen-4-one (Cvi)

Light yellow solid, yield: 69%, mp: 122–125 °C, IR (KBr, cm−1): 3107 (C–H sp2), 1610 (C=O), 1550 (C=C Ar), 1473 (C=C Ar), 1325 (C–N), 1213 (C–O), 756 (C–H bending) (Figure S6a); 1HNMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.99 (s, 1H, H-OCH3), 7.48 (m, 2H, J = 6.75 Hz, H-6 & 5ʺ), 7.82 (s, 1H, H-4ʺ), 7.93 (d, 2H, J = 8.55 Hz, H-2ʹ & 6ʹ), 8.06 (m, 2H, J = 7.35 & 7.7 Hz, H-8 & 2ʺ), 8.14 (t, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz, H-7), 8.00 (s, 1H, H-2ʺ), 8.39 (d, 2H, J = 8.5 Hz, H-3ʹ & 5ʹ), 8.47 (d, 1H, J = 8.35 Hz, H-5) (Figure S6b); 13CNMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 23.80 (C-4ʺ), 59.6 (C-OCH3), 118.4 (C-5), 118.7 (C-8), 120.5 (C-3ʹ & 5ʹ), 123.41 (C-4a), 124.6 (C-6), 124.63 (C-5), 130.4 (C-2ʹ & 6ʹ), 132.3 (C-4ʺ), 135.0 (C-2ʺ), 133.8 (C-7), 139.7 (C-3), 152.50 (C-4ʹ), 154.5 (C-2), 154.4 (C-8a), 173.0 (C-4) (Figure S6c);; TOF MS ES+ (m/z): 319.07 [M+H]+, Anal. Calcd. for C19H14N2O3, 318.1004 (Figure S6d).

2-(4-(1H-Benzo[d]imidazol-1-yl)phenyl)-3-methoxy-4H-chromen-4-one (Cvi)

Light yellow solid, yield: 79%, mp:—147–150 °C, λmax: 350, IR (KBr, cm−1): 3064 (C–H sp2), 2987 (C–H sp2), 2920 (C–H sp3), 1653 (C=O), 1595 (C=C Ar), 1454 (C=C Ar), 1371 (C–N), 1192 (C–O), 746 (Figure S7a); 1HNMR (500 MHz, CDCl3): δ 3.91 (s, 1H, H-OCH3), 6.11 (s, 1H, H-5ʺ), 6.32 (s, 1H, H-6ʺ), 7.01 (s, 1H, H-4ʺ), 7.10 (t, 1H, J = 7.4 Hz, H-6), 7.17 (d, 2H, J = 7 Hz, H-2ʹ & 6ʹ), 7.37 (m, 2H, J = 7.5 & 8.6 Hz, H-7 & 8), 7.53 (d, 1H, J = 7.6 Hz, H-7ʺ), 7.65 (d, 1H, J = 7.05 Hz, H-5), 8.07 (d, 2H, J = 8.07 Hz, H-3ʹ & 5ʹ), 8.25 (s, 1H, H-2ʺ) (Figure S7b); 13CNMR (500 MHz, DMSO): δ 59.62 (C-OCH3), 118.38 (C-8), 120.67 (C-2ʹ & 6ʹ), 121.21 (C-5ʺ), 121.51 (C-1ʹ), 124.64 (C-6), 124.75 (C-5), 129.11 (C-2ʹ & 6ʹ), 130.24 (C-1ʹ), 130.35 (C-4ʺ), 133.76 (C-7), 136.66 (C-2ʺ), 136.65 (C-3), 138.70 (C-4ʹ), 143.93 (C-2), 154.46 (C-8a), 172.91 (C-4) (Figure S7c); ESI MS ES+ (m/z): 369.09 [M+H]+, Anal. Calcd. for C23H16N2O3, 368.1161 (Figure S7d).

The 3-methoxy flavone Ci-vii derivatives were tested for their ability to kill cancer cells in vitro against breast cancer cell lines. The MTT technique was used to conduct cytotoxic research on MCF-7 cell lines, and the SRB method was used to conduct a cytotoxic study on MBA-MB-231 cell lines using 5-flurouracil as the positive control (Figures S8 & S9). Table 3 presents the overall findings of an anticancer investigation. IC50 values were determined by GraphPad Prism 9 and represented as mean ± standard error of mean (SEM) across triplicate experiment. Although compounds had shown excellent activity against MDA-MB-231, 3-methoxy flavone derivatives were observed less effective against the MCF-7 cell line. Compound Ciii showed significant cytotoxic effects against MCF-7 cell lines, with IC50 values of 13.08 ± 1.80 µg/ml, in comparison to the positive control, 5-flurouracil, which has an IC50 value of 20.90 ± 1.82 µg/ml. In the case of MDA-MB-231 cell lines, 5-flurouracil was found to be more active than all the synthesized 3-methoxy flavones, expressing the IC50 value of 1.31 ± 1.35 μg/ml. The compound Cv was found to be ineffective against MCF-7 cell lines but to be extremely effective against MDA-MB-231 cell lines, with IC50 values of 5.44 ± 1.66 µg/ml. Compound Ci showed poor inhibition of cell growth. In both the examined cell lines, compound Ci demonstrated only little capacity to inhibit cell growth.

Table 3.

In-vitro cytotoxic activity of compounds Ci-Cvii on MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines

| Compound code | In-vitro cytotoxic activity | |

|---|---|---|

| MCF-7 | MDA-MB-231 | |

| IC50 μg/ml | ||

| Ci | 263.00 ± 1.23 | 109.00 ± 1.26 |

| Cii | 93.20 ± 1.62 | 5.54 ± 1.57 |

| Ciii | 13.08 ± 1.80 | 23.78 ± 1.80 |

| Civ | 20.30 ± 1.47 | 30.57 ± 1.59 |

| Cv | 753.30 ± 1.16 | 5.44 ± 1.66 |

| Cvi | 105.30 ± 1.60 | 8.06 ± 1.83 |

| Cvii | 89.75 ± 1.50 | 46.23 ± 1.86 |

| 5-FU | 20.92 ± 1.82 | 1.31 ± 1.35 |

LC50 and IC50 values are presented as the mean ± SEM of at least three different experiment, IC50, half-maximal inhibitory concentration; MCF-7; ER + Breast cancer cell lines, MDA-MB-231, Triple negative breast cancer cell lines; 5-FU, 5-flurouracil used as a positive control

MDS was conducted on the proteins 2IOG and 3W2S in both their apo and ligand-bound states. RMSD, an indicator of stability and flexibility of protein confirmation throughout the simulation, ranges from 1.71 A° to 3.40 A° for the 2IOG_Apo, 2IOG_IOG, 2IOG_5-Flurouracil, 2IOG_Ciii, 2IOG_Civ, 3W2S_Apo, 3W2S_2WR, 3W2S_5-Flurouracil, 3W2S_Cii, 3W2S_Cv & 3W2S_Cvi. The computational study of hydrogen bonding interactions of synthesized compounds with respective their respective targets, 2IOG and 3W2S, observed a lower average number of hydrogen bonds than cocrystal ligands and 5-fluorouracil. Binding free energy analysis of 2IOG showed − 95.69 ± 4.77, − 64.35 ± 2.63, − 43.25 ± 1.05 and − 62.35 ± 2.63 kcal/mol binding free energy for IOG, 5-fluorouracil, Ciii and Civ respectively, while binding free energy analysis of 3W2S showed − 326.47 ± 9.41, − 255.61 ± 10.24, − 287.05 ± 11.22, − 285.27 ± 15.58, and − 287.83 ± 14.54 kcal/mol binding free energy for 2wr, 5-fluorouracil, Cii, Cv, and Cvi respectively. The MDS results showed that compounds Ciii and Civ bind stably to 2IOG while Cii, Cv and Cvi bind effectively to 3W2S, forming persistent protein–ligand complexes.

Discussion

The designed 3-methoxy flavone derivatives have drug-like characteristics. The targets used for the docking study are ER-α and EGFR to find the treatment option for hormone-dependent and hormone-independent breast cancer. ER-α and EGFR are overexpressed in MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 cell lines, respectively. The hormone-related breast cancer is mostly caused by the high level of estrogen in premenopausal women. The flavonoids have antiestrogenic potential and they can displace natural estrogen, 17-β-estradiol from the binding site of ER-α. 17-β-Estradiol competitive binding assays of natural and synthetic flavonoids on MCF-7 cell lines proved that flavonoids are competitive inhibitors of ER-α [37, 38]. Natural flavonoids have shown growth inhibition of MDA-MB-231 cell lines by targeting EGFR [39]. Heterocyclic rings are a major structural characteristic of most of the anticancer drugs and recent studies on heterocyclic substitution of these important rings on biologically important moieties; demonstrate the promising activity against breast cancer [40].

The characteristic C=O absorption band was visible in the IR spectrum of 3-methoxy flavon at 1650–1595 cm−1. The presence of methoxy group protons caused a prominent peak in the 1HNMR spectra of the compounds around δ 3.89–4.00. The unsaturated protons of triazole, imidazole, and benzimidazole migrated to the downfield region while saturated protons of morpholine, piperidine, N-methyl piperazine, and pyrrolidine were visible in the up-field zone. Flavone B rings protons 2' and 3' were coupled with 6' and 5' proton, respectively, and their presence was detected by two sharp doublets observed from δ 7.5 to 8.5. The results from 13CNMR spectra were comparable to the titled compounds. Mass spectroscopy of all synthesized compounds expressed [M+H]+ as a molecular ion peak with 100% abundance in mass spectra. Data obtained by all the spectroscopic techniques confirmed the synthesis of 3-methoxy flavone derivatives.

In the case of cancer, it is generally accepted that medications that modulate several targets may be more effective than drugs that just affect one target. Therefore, it is possible to control many targets concurrently with various mechanisms by using a single entity like flavone that can affect several targets in a multifactorial condition. Flavone is a phytoestrogen that can activate estrogen receptors, inhibit aromatase enzyme, modulate selective estrogen receptor, and inhibit 17β-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase [41]. 1,2,4 triazole substitution plays an important role in the activity of letrozole and anastrozole in breast cancer. In this study, we attempted 1,2,4 triazole substitution on the flavone ring; however the hybrid was found to be particularly active against non-hormone related breast cancer (MDA-MB-231), but ineffective against hormone related (estrogen positive) breast cancer cell lines (MCF-7). Other N-heterocyclic substitutions on flavone like piperidine, N-methyl piperazine, imidazole, benzimidazole and pyrrolidine, showed anticancer activity against tested cell lines. Flavone substituted with saturated rings like N-methyl piperazine, piperidine and pyrrolidine were found to be more active than the flavone substituted with unsaturated rings of benzimidazole and imidazole.

Overall results of anticancer activity revealed the importance of N-methyl piperazine ring substitution on 3-methoxy flavone, as this compound was found active in both cell lines. A 1,2,4-triazole substitution on 3-methoxy flavone was effective against MDA-MB-231 cell lines but not against MCF-7 cell lines. The methoxy flavones formed by morpholine substitution was the least active, while piperidine, pyrrolidine, imidazole, and benzimidazole substitutions on methoxy flavones showed moderate activity.

Simulations based on molecular dynamics (MD) and experiments were employed to investigate the stability and convergence of the Cα-backbone of 2IOG and 3W2S, both in their apo form and ligand-bound states. The Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) was calculated to gauge the deviations from the initial structure, providing insight into the flexibility and stability of the protein conformations. The Average RMSD for the 2IOG_Apo, 2IOG_IOG, 2IOG_5-Flurouracil, 2IOG_Ciii, 2IOG_Civ, 3W2S_Apo, 3W2S_2wr, 3W2S_5-Flurouracil, 3W2S_Cii, 3W2S_Cv & 3W2S_Cvi are 2.70, 2.47, 3.34, 3.26, 3.40, 2.06, 2.14, 2.04, 1.76, 2.23, 1.74 Å respectively, which provide quantitative data on the conformational stability of a protein–ligand system. Lower RMSD values generally indicate a more stable protein structure, while higher RMSD values suggest more significant conformational changes throughout the simulation. In Fig. 5-A1 the apo form of 2IOG shows moderate stability and serves baseline to evaluate the effect of ligand binding on the protein structure. The IOG seems to stabilize the 2IOG more than its apo form, indicated by lower average RMSD. 2IOG_5-Flurouracil shows relatively higher RMSD suggesting 5-fluorouracil may induce more flexibility or a significant conformational change in the protein. The test compounds Ciii and Civ show average RMSD values close to that of 5-fluorouracil, indicating that they cause a similar degree of structural variability and potentially have a similar binding mode or effect on the protein’s dynamics. While the Fig. 5-A2 showed that Apo form of 3W2S is quite stable, exhibiting relatively low RMSD values suggests a compact and consistent protein structure throughout the simulation. 3W2S_2wr shows a slight increase in RMSD from apo form suggesting that this compound does bind and slightly alter the conformation; it maintains stability comparable to the apo form. 3W2S_5-Flurouracil appears to stabilize the protein structure almost as well as when the protein is in its unbound state, indicating a very favorable interaction. Remarkably, the synthesized compounds Cii and Cvi showed an even lower RMSD than the apo form, suggesting an exceptional stabilization effect on the protein structure, while compound Cv shows stability not much different from the apo form. The MD simulations revealed that both standard and synthesized ligands have distinct effects on the conformational stability of the 2IOG protein. While IOG appears to stabilize the protein structure, 5-fluorouracil and the synthesized ligands increase the protein’s flexibility. The data suggest that the synthesized compounds Cii and Cvi could form very stable complexes with protein 3W2S, possibly more so than the standard 5-fluorouracil. This enhanced stability may indicate a strong affinity and specificity for the binding site, making these compounds promising candidates for further drug development and therapeutic applications. The minimal increase in RMSD for compound cv compared to the apo form suggests that it has a negligible destabilizing effect on 3W2S and maintains a stable protein conformation. This could inform further investigations into ligand binding dynamics.

Fig. 5.

MD simulation analysis of 100 ns trajectories of (A1) RMSD of Cα backbone of 2IOG_Apo (Black), 2IOG_IOG (Red), 2IOG_5-Fluorouracil (Green), 2IOG_ciii (Blue), 2IOG_civ (Pink); (A2) RMSD of Cα backbone of 3W2S_Apo (Black), 3W2S_2wr (Red), 3W2S_5-Fluorouracil (Green), 3W2S_cii (Blue), 3W2S_cv (Pink) & 3W2S_cvi (Cyan); (B1) RMSF of Cα backbone of 2IOG_Apo (Black), 2IOG_IOG (Red), 2IOG_5-Fluorouracil (Green), 2IOG_ciii (Blue), 2IOG_civ (Pink); (B2) RMSF of Cα backbone of 3W2S_Apo (Black), 3W2S_2wr (Red), 3W2S_5-Fluorouracil (Green), 3W2S_cii (Blue), 3W2S_cv (Pink) & 3W2S_cvi (Cyan); (C1) The radius of gyration (Rg) of Cα backbone of 2IOG_Apo (Black), 2IOG_IOG (Red), 2IOG_5-Fluorouracil (Green), 2IOG_ciii (Blue), 2IOG_civ (Pink); (C2) The radius of gyration (Rg) of Cα backbone of 3W2S_Apo (Black), 3W2S_2wr (Red), 3W2S_5-Fluorouracil (Green), 3W2S_cii (Blue), 3W2S_cv (Pink) & 3W2S_cvi (Cyan); (D1) Formation of hydrogen bonds in 2IOG_IOG (Red), 2IOG_5-Fluorouracil (Green), 2IOG_ciii (Blue), 2IOG_civ (Pink); (D2) Formation of hydrogen bonds in 3W2S_2wr (Red), 3W2S_5-Fluorouracil (Green), 3W2S_cii (Blue), 3W2S_cv (Pink) & 3W2S_cvi (Cyan)

Root Mean Square Fluctuation (RMSF) analysis was performed to evaluate and compare the flexibility of protein residues (2IOG & 3W2S) in their Apo form (Apo) and with various ligand-bound forms by plotting a graph of RMSF against residue numbers to map fluctuations across the protein structure and results are mentioned in Fig. 5B1, B2 In 2IOG, fluctuations peaked at residues 158–162 and 271–273 particularly in the presence of 5-fluorouracil, indicating potential sites of increased flexibility or binding interactions. Protein 3W2S displayed more pronounced fluctuations across the board, with the apo form showing comparable flexibility to some ligand-bound forms. The ligand-bound forms of 3W2S exhibited variable patterns, suggesting that different ligands influence the protein dynamics distinctly.

Figure 5C1 shows a graph of the radius of gyration (Rg) over time for 2IOG & 3W2S) in their Apo form and with various ligand-bound forms. The Rg provides insight into the folding state of the protein; a smaller radius of gyration typically suggests a more compact structure, while a larger Rg suggests an unfolded or extended conformation. The protein 2IOG_Apo maintains a relatively lower and more stable Rg, suggesting it may have a more stable or compact structure in the apo (unbound) form. 2IOG_5-fluorouracil has more variability in its Rg, indicating conformational changes due to binding with 5-fluorouracil. Figure 5C2 shows similar trends but with generally higher Rg values, which could indicate that the 3W2S complexes have a more extended conformation compared to the 2IOG complexes. The 3W2S_2WR and 3W2S_5-fluorouracil show significant spikes in Rg, which suggest transient unfolding events or interactions with the ligands that cause the protein to adopt more extended conformations. From the protein–ligand interactions, it has been found that regions of the highest Rg value are not involved in the binding site.

Figure 5D1, D2 shows the number of hydrogen bonds formed over time of 100 ns (ns) for different compounds with 2IOG and 3W2S. It is observed that the 2IOG_5-fluorouracil and 3W2S_5-fluorouracil conditions consistently maintained a higher number of hydrogen bonds throughout the simulation period compared to other variants. The average number of H-bonds for complexes like 2IOG_IOG, 2IOG_5-fluorouracil, 2IOG_Ciii, 2IOG_Civ, 3W2S_2WR, 3W2S_5-fluorouracil, 3W2S_Cii, 3W2S_Cv and 3W2S_Cvi were found to be 1.38, 1.60, 0.04, 0, 4.76, 2.91, 0.5, 0.66 and 0.2 respectively. The computational analysis of hydrogen bonding interactions for the compounds 2IOG and 3W2S, under different conditions, revealed distinct patterns in the average number of hydrogen bonds over the simulation period of 100 ns. For compound 2IOG, the variant 2IOG_IOG exhibited an average of 1.38 hydrogen bonds, whereas the 2IOG_5-fluorouracil condition showed a slightly higher average of 1.60 hydrogen bonds. Notably, the 2IOG_ciii and 2IOG_Civ conditions demonstrated significantly fewer hydrogen bonds, with averages of 0.04 and 0, respectively. In contrast, compound 3W2S showed a higher propensity for hydrogen bond formation under the 3W2S_2wr condition, averaging 4.76 bonds. The 3W2S_5-fluorouracil condition presented a moderately high average of 2.91 hydrogen bonds. The remaining variants, 3W2S_Cii, 3W2S_Cv, and 3W2S_Cvi, were observed to have lower averages of 0.5, 0.66, and 0.2 hydrogen bonds, respectively. The variance in the average number of hydrogen bonds across different conditions suggests a strong dependency on the specific interactions dictated by the molecular structure of the compound variants and their environmental context. The 2IOG and 3W2S variants with 5-fluorouracil both exhibited a higher-than-average number of hydrogen bonds, implying that 5-fluorouracil may enhance hydrogen bonding capacity in these settings. The chemical properties of 5-fluorouracil, known to act as a pyrimidine analogue interfering with nucleic acid synthesis, could facilitate additional hydrogen bonding with specific amino acid residues or nucleotides within the compound structures.

In contrast, the notably low average number of hydrogen bonds for conditions 2IOG_Ciii and 2IOG_Civ, as well as 3W2S_Cii, 3W2S_cv, and 3W2S_Cvi, could reflect a less favorable interaction landscape for hydrogen bonding within these systems or a possible destabilizing effect of the modifications or environmental changes represented by these conditions.

Molecular mechanics generalized born surface area (MM-GBSA) calculations

Utilizing the MD simulation trajectory, the binding free energy along with other contributing energy in form of MM-GBSA is determined for 2IOG_IOG, 2IOG_5-fluorouracil, 2IOG_ciii, 2IOG_civ, 3W2S_2wr, 3W2S_5-fluorouracil, 3W2S_cii, 3W2S_cv, 3W2S_cvi complexes. The results (Table 4) suggested that the maximum contribution to ΔGbind in the stability of the simulated complexes was due to ΔGbindCoulomb, ΔGbindvdW, ΔGbindHbond and ΔGbindLipo, while ΔGbindCovalent and ΔGbindSolvGB contributed to the instability of the corresponding complexes. In 2IOG, the cocrystal ligand shows comparatively lower binding free energies than other complexes while compound civ shows considerable binding energy like standard compound 5-Flurouracil (Table 4). In 3W2S, the cocrystal ligand shows comparatively lower binding free energies than other complexes while compounds cii, cv and cvi show better binding than 5-Flurouracil. These results supported the potential of ciii & civ towards 2IOG, while compounds cii, cv, and cvi towards 3W2S as well as efficiency in binding and the ability to form stable protein–ligand complexes. The energy component analysis of molecular binding interactions is mentioned in the Fig. 6.

Table 4.

Binding free energy components for 2IOG_IOG, 2IOG_5-fluorouracil, 2IOG_ciii, 2IOG_civ, 3W2S_2wr, 3W2S_5-fluorouracil, 3W2S_cii, 3W2S_cv, 3W2S_cvi

| Energies (kcal/mol) | 2IOG | 3W2S | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| IOG | 5-fluorouracil | Ciii | Civ | 2wr | 5-fluorouracil | Cii | Cv | Cvi | |

| ΔGbind | − 95.69 ± 4.77 | − 64.35 ± 2.63 | − 43.25 ± 1.05 | − 62.35 ± 2.63 | − 326.47 ± 9.41 | − 255.61 ± 10.24 | − 287.05 ± 11.22 | − 285.27 ± 15.58 | − 287.83 ± 14.54 |

| ΔGbindCoulomb | − 15.83 ± 15.18 | − 7.14 ± 0.75 | 17.47 ± 10.67 | − 6.14 ± 0.75 | − 333.28 ± 18.29 | − 419.98 ± 21.61 | − 331.13 ± 22.04 | − 393.86 ± 25.74 | − 312.85 ± 27.77 |

| ΔGbindCovalent | 0.43 ± 2.21 | 2.95 ± 1.50 | 2.08 ± 0.40 | 0.95 ± 1.50 | 11.28 ± 3.18 | 1.62 ± 6.23 | 3.34 ± 5.04 | 10.24 ± 6.15 | 10.98 ± 5.28 |

| ΔGbindHbond | − 1.33 ± 0.16 | − 14.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | − 14.02 ± 1.31 | − 9.89 ± 2.43 | − 13.99 ± 1.62 | − 14.85 ± 0.98 | − 15.06 ± 1.79 |

| ΔGbindLipo | − 40.35 ± 2.37 | − 11.10 ± 0.90 | − 13.97 ± 0.50 | − 21.10 ± 0.90 | − 77.74 ± 3.41 | − 61.46 ± 2.71 | − 64.03 ± 2.84 | − 67.48 ± 3.30 | − 70.87 ± 1.70 |

| ΔGbindSolvGB | 34.18 ± 14.51 | 16.32 ± 1.39 | − 5.04 ± 10.22 | 16.32 ± 1.39 | 339.03 ± 16.53 | 436.11 ± 14.17 | 349.08 ± 20.25 | 404.09 ± 25.61 | 321.33 ± 22.54 |

| ΔGbindvdW | − 72.06 ± 3.72 | − 51.83 ± 2.34 | − 43.79 ± 0.89 | − 51.83 ± 2.34 | − 249.97 ± 6.02 | − 201.19 ± 6.15 | − 227.22 ± 5.79 | − 221.74 ± 12.52 | − 217.25 ± 4.47 |

Fig. 6.

Energy component analysis for molecular binding interactions

Structure–activity relationship

To delve deeper into the SAR study of synthesized compounds (Ci-vii), we focus on electronic effects imparted by substituents at the 4ʹ position of the B ring of flavones. This influences cytotoxic activities against MCF-7 and MDA-MB-231 breast cancer cell lines by examining the interplay of electron-donating, withdrawing, and other chemical characteristics of substituents.

Substituent effects on cytotoxic activity

Compound Ci (Piperidinyl) exhibits the highest IC50 value among the series for MCF-7 cells and moderate for MDA-MB-231 as Piperidinyl is a saturated, electron-donating group, increases electron density on the flavone core through inductive effects, which might hinder binding with the estrogen receptor (ER) overexpressed in MCF-7 cells. Compound Civ (Pyrrolidinyl) shows moderate activity against both cell lines, as pyrrolidinyl is less bulky and donates electrons through sigma bonds, leading to potentially increasing the hydrophilicity of the molecule, which might limit its ability to interact effectively within the hydrophobic binding sites of ER or EGFR. Compound Cii (Methyl-piperazinyl): displays strong activity against MDA-MB-231 and moderate against MCF-7. A methyl group on piperazine adds both electron-donating and withdrawing effects. Piperazine itself can act as an electron-withdrawing group due to the nitrogen's electronegativity, potentially stabilizing the flavone’s interaction with EGFR, more prominent in MDA-MB-231. Compound Cv (Triazolyl) is highly effective against MDA-MB-231 but ineffective against MCF-7. Triazole is a strong electron-withdrawing group due to multiple nitrogens, which could enhance the electrophilic character of the flavone, increasing its interaction with nucleophilic sites on EGFR. Compound Cvi (Imidazolyl) and Cvii (Benzimidazolyl) show better activity against MDA-MB-231 than MCF-7. These heterocycles are strong electron-withdrawing groups, enhancing the compound’s ability to bind to overexpressed proteins in triple-negative breast cancer cell lines like MDA-MB-231.

Mechanism implications based on functional groups

Electron-donating groups generally increase the electron density of the aromatic system, making the flavone nucleus less susceptible to electrophilic attack but potentially more amenable to interactions with proton donors or positively charged residues within biological targets. Electron-withdrawing groups pull electron density away from the flavone nucleus, making it more electrophilic and potentially increasing the compound's reactivity towards nucleophiles, which could enhance binding to negatively charged or polar sites on biological targets.

Conclusion

In the current study, 3-methoxy flavone derivatives containing various N-heterocyclic moieties at the 4ʹ position of B ring of the flavone ring were synthesized. The flavonol was methylated by using dimethyl sulphate which follows SN2 reaction mechanism. The structures of all the derivatives were confirmed by spectroscopic studies. All compounds exhibit drug likeness properties. In cell line studies, 3-methoxy flavone derivatives showed considerable activity on MDA-MB-231. The derivatives were found less effective on MCF-7 cell line as compared to MDA-MB-231. Morpholine substitution on flavone was found ineffective while N-methyl piperazine and piperidine substitutions were found most effective against all cells. Triazole substitution on 3-methoxy flavone was inactive against MCF-7 cell lines but highly active against and MDA-MB-231 cell lines. Docking studies of these compounds on 2IOG and 3W2S showed the lower binding energy than the standard drug 5-fluorouracil but slightly higher than the co-crystallized ligands of the targets, 2IOG and 3W2S. Molecular dynamics not only suggested the potential of compounds 3-methoxy flavone derivatives towards 2IOG and 3W2S but also proves the efficiency in binding and the ability to form stable protein–ligand complexes. Flavone ring is substituted with saturated and unsaturated heterocyclic rings. These heterocyclic rings affect the electron density of the flavone ring. Structure activity relationship suggested beneficial effect of unsaturated heterocyclic rings in cytotoxic activity on MBA-MB-231 cell lines.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

The authors are grateful to LSHGCT Gahlot Institute of Pharmacy for providing the necessary research facilities.

Author contributions

BSF—conceptualization, writing—original draft, formal analysis. Writing—review & editing, and validation SYC—conceptualization, writing—original draft, writing—review & editing, formal analysis and validation RVL—conceptualization, writing—original draft, formal analysis and validation RPB—investigation, writing—original draft, formal analysis and validation PSU—Investigation, writing—original draft, Formal analysis and validation SSP—investigation, writing—original draft, formal analysis and validation SM—Investigation, writing—original draft, formal analysis and validation DEU—conceptualization, writing—original draft, formal analysis and validation MEAZ—Formal analysis. Writing—review & editing, and validation EUA—formal analysis. Writing—review & editing, and validation.

Funding

The author(s) declare no financial support was received for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Data availability

All used data are within the manuscript.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Somadatta Y. Chaudhari, Email: somu.chaudhari@gmail.com

Daniel Ejim Uti, Email: daniel.ejimuti@kiu.ac.ug.

Magdi E. A. Zaki, Email: mezaki@imamu.edu.sa

References

- 1.Bray F, Laversanne M, Weiderpass E, Soerjomataram I. The ever-increasing importance of cancer as a leading cause of premature death worldwide. Cancer. 2021;127(16):3029–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mathur P, Sathishkumar K, Chaturvedi M, Das P, Sudarshan KL, Santhappan S, et al. Cancer statistics, 2020: report from national cancer registry programme. India JCO Glob Oncol. 2020;6:1063–75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Danihelová M, Veverka M, Šturdík E, Jantová S. Antioxidant action and cytotoxicity on HeLa and NIH-3T3 cells of new quercetin derivatives. Interdiscip Toxicol. 2013;6(4):209–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Veeramuthu D, Raja WR, Al-Dhabi NASI. Flavonoids: anticancer properties. In: Flavonoids: from biosynthesis to human health. InTech; 2012. p. 287–303. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Diwan AD, Panche ANCSR. Flavonoids: an overview. J Nutr Sci. 2016;5:1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kopustinskiene DM, Jakstas V, Savickas A, Bernatoniene J. Flavonoids as anticancer agents. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):1–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Meher RK, Mir SA, Singh K, Mukerjee N, Nayak B, Kumer A, Zughaibi TA, Khan MS, Tabrez S. Decoding dynamic interactions between EGFR‐TKD and DAC through computational and experimental approaches: A novel breakthrough in lung melanoma treatment. Journal of Cellular and Molecular Medicine. 2024 May;28(9):e18263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wendlocha D, Krzykawski K, Mielczarek-Palacz A, Kubina R. Selected flavonols in breast and gynecological cancer: a systematic review. Nutrients. 2023;15(13):2938. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Park MY, Kim Y, Ha SE, Kim HH, Bhosale PB, Abusaliya A, et al. Function and application of flavonoids in the breast cancer. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23(14):1–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Plochmann K, Korte G, Koutsilieri E, Richling E, Riederer P, Rethwilm A, et al. Structure-activity relationships of flavonoid-induced cytotoxicity on human leukemia cells. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2007;460(1):1–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cushman M, Zhu H, Geahlen RL, Kraker AJ. Synthesis and biochemical evaluation of a series of aminoflavones as potential inhibitors of protein-tyrosine kinases p56lck, EGFr, and p60v-src. J Med Chem. 1994;37(20):3353–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Akama T, Ishida H, Shida Y, Kimura U, Gomi K, Saito H. Design and synthesis of potent antitumor 5, 4′-diaminoflavone derivatives. J Med Chem. 1997;2623(97):1894–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beutler JA, Hamel E, Vlietinck AJ, Haemers A, Rajan P, Roitman JN, et al. Structure-activity requirements for flavone cytotoxicity and binding to tubulin. J Med Chem. 1998;41(13):2333–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moorkoth S, Srinivasan KK, Gopalan Kutty N, Joseph A, Naseer M. Synthesis and evaluation of a series of novel imidazolidinone analogues of 6-aminoflavone as anticancer and anti-inflammatory agents. Med Chem Res. 2013;22(10):5066–75. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Walle T. Methoxylated flavones, a superior cancer chemopreventive flavonoid subclass? Semin Cancer Biol. 2007;17(5):354–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Suganya J, Radha M, Naorem DL, Nishandhini M. In silico docking studies of selected flavonoids—natural healing agents against breast cancer. Asian Pacific J Cancer Prev. 2014;15(19):8155–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Armstrong DK, Kaufmann SH, Ottaviano YL, Furuya Y, Buckley JA, Isaacs JT, et al. Epidermal growth factor-mediated apoptosis of MDA-MB-468 human breast cancer cells. Cancer Res. 1994;54(20):5280–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Park EJ, Min HY, Chung HJ, Hong JY, Kang YJ, Hung TM, et al. Down-regulation of c-Src/EGFR-mediated signaling activation is involved in the Honokiol-induced cell cycle arrest and apoptosis in MDA-MB-231 human breast cancer cells. Cancer Lett. 2009;277(2):133–40. 10.1016/j.canlet.2008.11.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pouget C, Lauthier F, Simon A, Fagnere C, Basly JP, Delage C, et al. Flavonoids: Structural requirements for antiproliferative activity on breast cancer cells. Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 2001;11(24):3095–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chinnikrishnan P, Aziz Ibrahim IA, Alzahrani AR, Shahzad N, Sivaprakasam P, Pandurangan AK. The role of selective flavonoids on triple-negative breast cancer: an update. Separations. 2023;10(3):207. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Akhtar J, Khan AA, Ali Z, Haider R, Yar MS. European Journal of Medicinal Chemistry Structure-activity relationship (SAR) study and design strategies of nitrogen-containing heterocyclic moieties for their anticancer activities. Eur J Med Chem. 2017;125(125):143–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Majed AA, Al-Duhaidahawi D, Omran AH, Abbas S, Abid SD, Hmood YA. Synthesis, molecular docking of new amide thiazolidine derived from isoniazid and studying their biological activity against cancer cells. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2024;42(24):13485–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Omran HA, Majed AA, Hussein K, Abid DS, Abdel-Maksoud MA, Elwahsh A, et al. Anti-cancer activity, DFT and molecular docking study of new BisThiazolidine amide. Results Chem. 2024;12: 101835. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Majed AA, Abid DS. Synthesis of some new thiazolidine and 1,3,4-oxadiazole derived from L-cysteine and study of their biological activity as antioxidant and breast cancer. Lett Appl NanoBioScience. 2022;12(3):82. [Google Scholar]

- 25.McLean L, Soto U, Agama K, Francis J, Jimenez R, Pommier Y, et al. Aminoflavone induces oxidative DNA damage and reactive oxidative species-mediated apoptosis in breast cancer cells. Int J Cancer. 2008;122(7):1665–74. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Pettersen EF, Goddard TD, Huang CC, Couch GS, Greenblatt DM, Meng EC, et al. UCSF Chimera—a visualization system for exploratory research and analysis. J Comput Chem. 2004;25(13):1605–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Morris GM, Huey R, Lindstrom WMFS, Belew RK, Goodsell DSAJO. Software news and updates gabedit—a graphical user interface for computational chemistry softwares. J Comput Chem. 2009;30(16):174–82. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tian W, Chen C, Lei X, Zhao J, Liang J. CASTp 3.0: computed atlas of surface topography of proteins. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018;46(W1):W363–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eberhardt J, Santos-Martins D, Tillack AF, Forli S. AutoDock Vina 1.2.0: new docking methods, expanded force field, and python bindings. J Chem Inf Model. 2021;61(8):3891–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fegade B, Jadhav S. Design, synthesis and molecular docking study of N-heterocyclic chalcone derivatives as an anti-cancer agents. Int J Pharm Sci Drug Res. 2022;14(01):78–84. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Fegade BS, Jadhav S. Synthesis, molecular docking, and anticancer activity of N-heteroaryl substituted flavon derivatives. Lett Drug Des Discov. 2023;20(12):2055–69. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Reddy Kotha R, Kulkarni GR, Garige AK, Goud Nerella S, Garlapati A. Synthesis and cytotoxic activity of new chalcones and their flavonol derivatives. Med Chem (Los Angeles). 2017;7(11):353–60. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Moorkoth S. Synthesis and anti-cancer activity of novel thiazolidinone analogs of 6-aminoflavone. Chem Pharm Bull. 2015;63(12):974–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Desideri N, Mastromarino P, Conti C. Synthesis and evaluation of antirhinovirus activity of 3-hydroxy and 3-methoxy 2-styrylchromones. Antivir Chem Chemother. 2003;14(4):195–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tim M. Rapid colorimetric assay for cellular growth and survival: application to proliferation and cytotoxicity assays. J Immunol Methods. 1983;65(1–2):55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Skehan P, Storeng R, Scudiero D, Monks A, Mcmahon J, Vistica D, et al. New colorimetric cytotoxicity assay for anticancer-drug screening. J Natl Cancer Inst. 1990;82(13):1107–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Collins-burow BM, Burow ME, Duong BN, Mclachlan JA, Collins-burow BM, Burow ME, et al. Estrogenic and antiestrogenic activities of flavonoidphytochemicals through estrogen receptorbinding-dependent and -independent mechanisms estrogenic and antiestrogenic activities of flavonoid phytochemicals through estrogen receptor binding-dependent and. Nutr Cancer. 2009;38(2):37–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Fegade BS, Jadhav SB, Chaudhari SY, Tandale TD, Shantaram Uttekar P, Tabrez S, et al. Synthesis and computational insights of flavone derivatives as potential estrogen receptor alpha (ER-α) antagonist. J Biomol Struct Dyn. 2023;42(24):1–10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Guo M, Wang M, Deng H, Zhang X, Wang ZY. A novel anticancer agent Broussoflavonol B downregulates estrogen receptor (ER)-α36 expression and inhibits growth of ER-negative breast cancer MDA-MB-231 cells. Eur J Pharmacol. 2013;714(1–3):56–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mahdi ZH, Alsalim TA, Abdulhussein HA, Majed AA, Abbas S. Synthesis, molecular docking, and anti-breast cancer study of 1-H-indol-3-carbohydrazide and their derivatives. Results Chem. 2024;11: 101762. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Thakor V, Kher J, Bhayani F, Atodaria B, Noolvi M. Synthesis and anticancer activity of flavone derivatives against estrogen dependent cancers by rational approach. PharmaTutor. 2014;2(2):33–43. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All used data are within the manuscript.