Abstract

Background

Some patients with melanoma experience disease progression during immunotherapy (IO) and may benefit from novel combinations of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). We report results from exploratory biomarker analyses to characterize the responses of patients with advanced melanoma to treatment with nivolumab (anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD-1)) and relatlimab (anti-lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3)) combination therapy in RELATIVITY-020 (NCT01968109).

Methods

Tumor biopsies collected at baseline and ≤4 weeks after treatment initiation were evaluated for % LAG-3-positive and % CD8-positive immune cells and % programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) expression on tumor cells. Baseline biomarker expression was compared among patients with IO-refractory melanoma based on last prior therapy and IO-resistance type, and between patients with IO-refractory and IO-naïve melanoma. Change in biomarker expression after treatment was evaluated in patients with IO-refractory and IO-naïve melanoma. Immune-related gene expression was compared among resistance groups and by the last prior treatment.

Results

Among patients with IO-refractory melanoma (N=505), elevated baseline LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 expression (p≤0.01, p≤0.05, p≤0.001, respectively) was observed in patients whose last prior therapy was IO versus non-IO, and in those who responded (complete/partial per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors V.1.1) to nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy versus those who did not (stable/progressive disease). Inflammation-related gene expression was significantly higher (p<0.05) in patients with secondary versus primary resistance to prior IO treatment, and in those whose last prior therapy was IO versus non-IO. IO-refractory patients whose tumors responded to nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy had higher inflammation-related gene expression than non-responders (p<0.05); proliferation and hypoxia-related gene expression were enriched in non-responders. During treatment with nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy, LAG-3 expression increased significantly in patients with IO-refractory (p≤0.01) and IO-naïve melanoma (p≤0.001), and PD-L1 and CD8 increased significantly (p≤0.01 and p≤0.05, respectively) in patients with IO-naïve melanoma.

Conclusions

Nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy can modulate the tumor microenvironment in patients with both IO-refractory and IO-naïve melanoma. Further research is needed to identify patients who will most benefit from anti-LAG-3/PD-(L)1 agents, and to elucidate the mechanisms of action of, and resistance to, this combination therapy in patients with advanced melanoma.

Trial registration number

Keywords: Combination therapy, Gene expression profiling - GEP, Immune Checkpoint Inhibitor, Biomarker

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Some patients with melanoma experience disease progression during immunotherapy (IO) and may benefit from novel combinations of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs). While resistance to programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1) and programmed cell death-1 inhibitors has been associated with the upregulation of immune checkpoints such as lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3) and cytotoxic T-lymphocyte-associated antigen 4 on T cells, modulation of the tumor microenvironment and changes in serum biomarkers in response to new ICI combination therapies have not been well characterized.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

In this study, exploratory biomarker analyses were performed to characterize the responses of patients with advanced melanoma to treatment with nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy using targeted cohorts from RELATIVITY-020. Comparing baseline tumor biomarker and gene expression among IO-refractory patients grouped by most recent prior therapy showed that LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 expression was elevated in patients whose most recent prior treatment was IO versus targeted therapy, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy. On-treatment increases in LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 expression were seen in both IO-refractory patients and patients who received nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy as first-line therapy. Together, our results suggest that the tumor microenvironment may be modulated by nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy despite earlier disease progression on IO.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE, OR POLICY

Our study identifies key biologic pathways and types of prior cancer treatments that help to explain why patients with advanced melanoma, whose tumors were refractory to prior immune checkpoint blockade, may benefit from nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy. Additional research is needed to identify biologic pathways or treatment histories that distinguish patients with primary versus secondary resistance or reveal mechanistic differences between responses among patients receiving IO as first-line therapy versus second-line or later treatment.

Introduction

Some patients with melanoma experience progressive disease despite treatment with programmed cell death-1/programmed cell death-ligand 1 (PD-(L)1) inhibitors.1,3 Characterizing the responses of the tumor microenvironment (TME) in this patient population to novel combinations of immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) may help to guide patient stratification and improve patient outcomes.

Treatment with PD-(L)1 inhibitors is associated with upregulation of immune checkpoints such as lymphocyte-activation gene 3 (LAG-3) and cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4 (CTLA-4) on T cells, creating a potential mechanism of resistance to immunotherapy (IO).4 5 In a study of patients with metastatic melanoma treated sequentially with anti-CTLA-4 followed by anti-programmed cell death-1 (PD-1) agents (n=46), adaptive immune profiles in early on-treatment tumor biopsies were predictive of response versus non-response to immune checkpoint blockade therapy.6 Using a 12-marker immunohistochemistry (IHC) panel, on-treatment tissue samples collected within 3.2 months of anti-CTLA-4 therapy showed increased levels of T cells and PD-L1, followed by decreased PD-L1 levels 3 months post-treatment. Assessment of tumor biopsy samples collected within 1.4 months of anti-PD-1 treatment initiation showed that patients who received PD-1 blockade after progression on anti-CTLA-4 therapy had increased levels of T cells, PD-L1, and LAG-3. Recent research on immunophenotyping in patients with metastatic melanoma showed that combination treatment with the PD-1 inhibitor nivolumab and the LAG-3 inhibitor relatlimab resulted in simultaneous activation of cytotoxic T cells and adaptive natural killer (NK) cells, both cell types with elevated LAG-3 expression.7 The stimulatory effect of this combination therapy was greater in responders, who had higher levels of cytotoxic T cells and NK cells than non-responders.

Relatlimab is a monoclonal antibody that inhibits LAG-3 and is available in a fixed-dose combination with nivolumab for the treatment of patients with previously untreated metastatic or unresectable melanoma,8 9 based on the progression-free survival benefit versus nivolumab monotherapy demonstrated in the RELATIVITY-047 trial.10 RELATIVITY-020 (NCT01968109) is a phase 1/2a study evaluating the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of relatlimab administered alone and in combination with nivolumab in patients with solid tumors, including patients with advanced melanoma. The results from Part D showed that nivolumab in combination with relatlimab had durable clinical benefit in a proportion of heavily pretreated patients with advanced melanoma, over half of whom had received two or more lines of therapy.1 The observed objective response rate (ORR) per Response Evaluation Criteria in Solid Tumors (RECIST) V.1.1 by blinded independent central review (BICR) in evaluable patients who had progressed during or within 3 months of treatment with 1 anti-PD-1–containing regimen prior to nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy (n=351) was 12% (95% CI, 8.8% to 15.8%). Responses occurred regardless of baseline LAG-3 and PD-L1 expression in the TME but were enriched among patients with tumors expressing LAG-3 and PD-L1.1

To better understand subgroups of patients who may derive increased benefit from nivolumab and relatlimab, we performed exploratory IO biomarker analyses using data from Parts C and D of RELATIVITY-020. We conducted post hoc analyses in patients with advanced melanoma to investigate the on-treatment effects of nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy on IO biomarkers, specifically LAG-3, tumor cell (TC) PD-L1, and CD8. These analyses included both IO-naïve patients and those who had received prior treatment with IO. In addition, we compared baseline biomarker expression between IO-naïve and IO-refractory disease, and investigated whether baseline biomarker levels were associated with prior therapy modality or type of resistance to IO. We also conducted RNA sequencing (RNA-seq) of tumor tissues to characterize immune gene signatures associated with IO resistance, and to evaluate gene expression profiles with respect to the type of most recent prior therapy. The overall study objective was to determine, based on inflammatory biomarker expression, whether tumors that were resistant to prior anti–PD-(L)1 treatment may be sensitive to subsequent IO regimens, and whether this sensitivity depends on the type of prior treatment or lack of previous exposure to IO therapies.

Methods

Trial design

RELATIVITY-020 (NCT01968109) was a phase 1/2a study evaluating the safety, tolerability, and efficacy of relatlimab administered alone and in combination with nivolumab in patients with advanced solid tumors. Details on the trial design can be found in the Supplement (online supplemental file 2). Patients enrolled in RELATIVITY-020 Parts C and D1 who had histologically or cytologically confirmed advanced (metastatic and/or unresectable) melanoma were selected for the current analyses (online supplemental figure S1).

In the Part C dose-expansion phase, eligible patients included those for whom the RELATIVITY-020 treatment regimen was the first line of treatment (1L patients; n=66), and, in a separate cohort, patients with disease that had progressed on prior treatment with anti-PD-(L)1-containing regimens, with or without an anti-CTLA-4-containing regimen (IO-refractory patients, n=151). All patients were administered 240 mg nivolumab+80 mg relatlimab every 2 weeks by sequential infusion.

Part D1 was an extended expansion phase in which eligible patients had received 1 line of prior anti-PD-1-containing treatment (with or without anti-CTLA-4) and had documented disease progression within 3 months of the final dose of anti-PD-1 therapy. Patient cohorts and methods of drug delivery are described in Ascierto et al,1 and the study design is shown in online supplemental figure S1.

Assessment of treatment response

Tumor response was evaluated using RECIST V.1.111 per BICR. Patients with a best overall response (BOR) of complete response (CR) or partial response (PR) were classified as responders; patients whose BOR did not meet the criteria for CR or PR were classified as non-responders. ORR was defined as the number of responders divided by the total number of patients.

Patients with melanoma that was refractory to prior anti-PD-(L)1 therapy and whose most recent prior therapy was IO were classified by type of resistance (primary vs secondary). Resistance was categorized using modified Society for Immunotherapy of Cancer criteria12 as limited information regarding characteristics of response to prior IO was collected in the study; for example, information on confirmatory scans or duration of stable disease (SD) was not captured. Primary resistance was defined as having a best response of progressive disease (PD) or SD, and a time to progression of less than 6 months, after at least 6 weeks of treatment. Secondary resistance was defined as the best response of CR, PR, or SD, and a time to progression of more than 6 months, after at least 6 weeks of treatment.

Tumor tissue collection and IHC

For each patient, baseline tumor tissue for biomarker assessment was obtained either from an archival sample collected within 3 months of enrollment or from a fresh pretreatment biopsy. LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 levels in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tumor samples from patients were evaluated by IHC at baseline and within 4 weeks of treatment. LAG-3 and CD8 IHC were performed as described previously.10 13 LAG-3 expression was assessed as the percentage of positive immune cells among all nucleated cells within the tumor and invasive margin, using mouse antibody clone 17B4.14 CD8 was scored as the percentage of CD8-positive cells relative to total nucleated cells using a pathologist-supervised digital image analysis algorithm.13 TC PD-L1 expression was assessed using the Dako PD-L1 IHC 28–8 pharmDx assay (Agilent Technologies Inc., Santa Clara, California, USA) and was quantified as the percentage of PD-L1–expressing TCs divided by all TCs.

Serum assessment of soluble LAG-3

Free soluble LAG-3 (sLAG-3) was measured in baseline serum samples by electrochemiluminescence (Meso Scale Discovery, Rockville, Maryland, USA), which uses a custom biotinylated monoclonal antibody targeting LAG-3, as described previously.1

RNA sequencing

RNA samples were processed by Q2 Solutions (Morrisville, North Carolina, USA) using the Illumina TruSeq RNA Access method (Illumina Inc., San Diego, California, USA), which is a hybridization-based protocol to enrich for coding RNAs from total RNA-seq libraries. First-strand complementary DNA (cDNA) synthesis was primed from total RNA using random primers, followed by the generation of second-strand cDNA with deoxyuridine triphosphate used in place of deoxythymidine triphosphate in the master mix. Double-stranded cDNA then underwent end-repair, A-tailing, and ligation of adapters that included index sequences. The resulting molecules were amplified via PCR, their yield and size distribution determined, and their concentrations normalized in preparation for the enrichment step. Libraries were enriched for the messenger RNA fraction by positive selection using a cocktail of biotinylated oligonucleotides corresponding to coding regions of the genome. Targeted library molecules were then captured via the hybridized biotinylated oligonucleotide probe using streptavidin-conjugated beads. After two rounds of hybridization/capture reactions, the enriched library molecules were amplified by PCR. Normalized libraries were pooled and sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencing-by-synthesis platform, with a sequencing protocol of 50 bp paired-end sequencing and a total read depth of 50 M reads per sample.

Exploratory biomarker analyses

Several exploratory biomarker analyses were conducted. IO-refractory patients were grouped according to their most recent type of prior therapy: IO, targeted therapy, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, or “Other/Not applicable (NA)”, as shown in table 1. The decision to include radiotherapy as part of this systemic therapy grouping strategy was based on the abscopal effect of radiotherapy (ie, tumor regression outside of the irradiated field).15 16 Baseline biomarker expression by IHC (LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8) and by immunoassay (sLAG-3) was then compared among patients from Parts C and D1 who had been previously exposed to IO based on their most recent prior therapy. Differential gene expression of baseline tumor samples based on RNA-seq was also evaluated in IO-refractory patients from Parts C and D1 to determine whether immune-related gene expression differed among patients depending on their most recent prior therapy. The gene sets targeted for this analysis have been previously described.17,38

Table 1. Types of most recent prior therapies received by patients with melanoma in cohorts from Parts C and D1*.

| Most recent line of prior therapy, n (%) | Prior therapy category† | Part C (n=151) | Part D1 (n=354) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Anti-PD-(L)1 monotherapy | Prior IO | 96 (63.6) | 210 (59.3) |

| Anti-CTLA-4 monotherapy | Prior IO | 11 (7.3) | 20 (5.6) |

| IO combo | Prior IO | 11 (7.3) | 35 (9.9) |

| IO combo+chemotherapy | Prior IO | 1 (0.7) | 0 (0) |

| Radiotherapy | Radiotherapy | 9 (6.0) | 30 (8.5) |

| Targeted therapy | Targeted therapy | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Chemotherapy+targeted therapy | Targeted therapy | 10 (6.6) | 20 (5.6) |

| Chemotherapy only | Chemotherapy | 7 (4.6) | 23 (6.5) |

| Other/NA | Other/NA | 6 (4.0) | 15 (4.2) |

Excludes treatment-naïve (1L) patients.

Category used for group comparisons in the current analysis.

Combo, combination anti-PD-(L)1 and anti-CTLA-4 therapy; CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4; IO, immunotherapy; NA, not applicable; PD-(L)1, programmed death (ligand)-1.

Next, baseline IHC biomarker expression was evaluated by resistance type (primary vs secondary resistance) in IO-refractory patients from Parts C and D1 who had received anti-PD-(L)1 regimens as the most recent prior therapy. LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 IHC expression was compared between patients who had experienced primary versus secondary resistance, and RNA-seq was performed to characterize gene signatures, including inflammatory and stromal signatures, associated with resistance status.

Third, baseline levels of target biomarkers measured by IHC were compared between IO-refractory and 1L patients using the patient cohorts from Part C of RELATIVITY-020. On-treatment changes in biomarker levels were also evaluated to determine whether the TME in IO-refractory and 1L patients was modulated by nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy.

A fourth analysis using baseline LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 IHC data from IO-refractory patients in Parts C and D1, baseline soluble LAG-3 data from IO-refractory patients in Part D1, and RNA-seq data from patients in Part D1 was conducted to determine whether baseline levels of biomarkers or gene signatures differentially associate with responders versus non-responders to nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy.

Statistical approach

Descriptive statistics were used in all analyses, and all data sets and results were internally validated by a team of statisticians. Group comparisons included a pooled approach in which patients from Parts C and D1 were combined, as the various dosing regimens have been shown to have no appreciable effect on the safety and efficacy of nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy.1 Group comparisons were tested using the Wilcoxon test without multiple comparison correction, and linear mixed effect modeling was used to assess paired differences within patient treatment groups.

Throughout the study, IHC expression levels of LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 were treated as continuous variables, allowing for more exploratory and expanded statistical approaches to be used than those available for binarized variables. However, given that binary variables are conventionally used in biomarker studies, we also defined tumor positivity for PD-L1, LAG-3, and CD8 expression using a 1% cut-off when evaluating tumor response. Consequently, all IHC-based biomarkers were analyzed as both binary and continuous variables across the study.

RNA-seq analysis was limited to the Part D1 cohort to avoid batch effects in the analysis. Immune-related gene signatures chosen for evaluation have been published elsewhere.1735 36 39,42 For each signature derived from RNA-seq, the signature scores were calculated by Z-scoring the expression values for each gene in the signature, then calculating the median score value across all genes for each sample. The signature scores for each sample were then determined by the median of the z-score scaled expression of each gene.

Results

The types of most recent prior therapy received by IO-refractory patients with melanoma in Parts C and D1 of RELATIVITY-020 are shown in table 1. The majority of patients had received IO (anti-PD-(L)1 monotherapy, anti-CTLA-4 monotherapy, combination IO, or combination IO plus chemotherapy) as their most recent prior therapy. A smaller proportion of patients had received targeted therapy, with or without chemotherapy, as their most recent line of prior therapy. The remaining patients had been treated either with chemotherapy or radiotherapy alone as their most recent line of therapy or were classified as “Other/NA”. The percentage of patients with evaluable samples for each biomarker, grouped by most recent prior treatment, is shown in online supplemental table S1. At least 50% of patients had evaluable samples for LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8. Less than 50% of patients had evaluable samples for sLAG-3 and RNA-seq.

Baseline biomarker expression by most recent prior therapy

In the pooled analysis of patients in Parts C and D1, IO-refractory patients whose most recent prior line of therapy was IO had significantly higher baseline expression (assessed by IHC) of LAG-3 (p≤0.01), PD-L1 (p≤0.05), and CD8 (p≤0.001) than those whose most recent prior line was targeted therapy, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy (figure 1A). Compared with LAG-3 and PD-L1, CD8 expression was most variable in patients whose most recent line of therapy was non-IO. Similar results were observed when Parts C and D1 were evaluated individually or when prior PD-(L)1 was separated from prior CTLA-4 as most recent therapy; baseline LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 IHC expression levels were significantly higher (p≤0.05 to p≤0.01) in IO-refractory patients whose most recent prior line of therapy was IO than in patients whose most recent prior treatment was targeted therapy, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy (online supplemental figure S2).

Figure 1. Tumor biomarker expression levels by most recent prior therapy at baseline (A) and in responders compared with non-responders (B). Boxes extend from the first to third quartiles, the middle line shows the median biomarker level, and the whiskers extend to the most extreme data point that is no more than 1.5 times the IQR from the box. ***p≤0.001; **p≤0.01; *p≤0.05. P values compare biomarker levels between the CR/PR and SD/PD groups using the Wilcoxon test without multiple comparison correction. aTrend association, p≤0.10. CR, complete response; IHC, immunohistochemistry; IO, immunotherapy; IO-last, patients whose most recent prior therapy was IO; LAG-3, lymphocyte-activation gene 3; NA, not applicable; ND, not determined; NE, non-evaluable; NIVO, nivolumab; NN, non-CR/non-PD; ns, not significant; PD, progressive disease; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; PR, partial response; RELA, relatlimab; SD, stable disease; TC, tumor cell.

Among IO-refractory patients treated with nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy whose most recent prior therapy was IO compared with non-IO, a BOR of CR or PR was seen in 46/384 (ORR 12.0%) and 12/121 (ORR 9.9%) patients, respectively. Evaluating ORRs by LAG-3 and PD-L1 positivity, ORRs were higher for patients whose tumors were positive versus negative (≥1% expression vs <1%) for LAG-3, whether the most recent prior therapy was IO (15.9% vs 4.4%) or non-IO (13.2% vs 7.1%; online supplemental figure S3A). ORRs were also higher for patients with PD-L1-positive tumors (≥1% expression vs <1%) whose most recent prior therapy was IO versus non-IO (15.0% vs 8.4%), but comparable among patients with PD-L1-positive and PD-L1-negative tumors whose most recent prior therapy was non-IO (10.0% vs 10.9%). ORRs were also higher in patients whose tumors were positive for LAG-3 or PD-L1 expression, whether the most recent prior IO was anti-PD-L1 or anti-CTLA-4; within this group, the highest ORRs were observed in patients who received an anti-CTLA-4 containing regimen (LAG-3+, 22.5%; PD-L1+, 17.9%; online supplemental figure S3B).

When patients whose most recent line of prior therapy was IO were grouped by response to nivolumab and relatlimab combination treatment, baseline TME expression of LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 was significantly higher in responders than in non-responders (p≤0.01, p≤0.05, and p≤0.001, respectively; figure 1B, online supplemental figure S2). Differential expression of biomarkers between responders and non-responders was not observed for patients who received targeted therapy, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy as their most recent prior therapy.

In contrast to the TME biomarkers, no significant differences in sLAG-3 levels in peripheral blood samples were observed between the different lines of most recent prior therapy in IO-refractory patients (online supplemental figure S4A, table S2). Similarly, baseline sLAG-3 levels were not significantly different between nivolumab and relatlimab responders and non-responders across the prior therapy groups (online supplemental figure S4B, table S3).

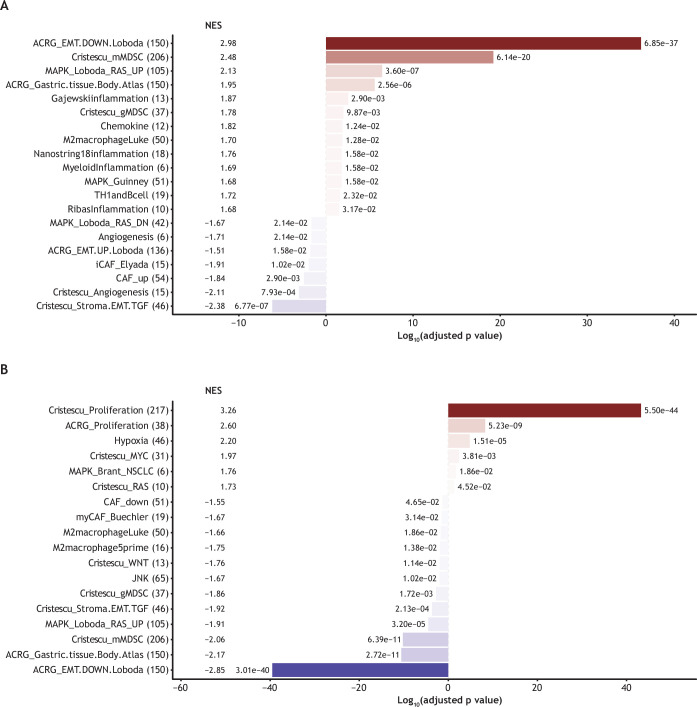

Gene expression by a most recent line of therapy

Gene expression profiles varied among IO-refractory patients whose most recent line of therapy was IO, targeted therapy, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy. A summary of treated patients and RNA-evaluable samples is provided in the online supplemental table S4. IO was associated with enriched inflammation-related signaling, suggesting myeloid cell involvement, whereas non-IO regimens (such as targeted therapy and chemotherapy) were associated with signatures representing carcinoma-associated fibroblasts, angiogenesis, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition (p≤0.01 for all signatures; figure 2A). In addition, different gene signatures were enriched in tumors previously treated with PD-(L)1-only regimens (eg, gene signatures for proliferation, hypoxia, and the Myc pathway) compared with tumors previously treated with anti-CTLA-4-containing regimens, for which gene signatures representing epithelial–mesenchymal transition, myeloid cells/macrophages, Wnt, and stromal/carcinoma-associated fibroblasts were higher (p≤0.05 for all signatures; figure 2B).

Figure 2. Summary of enriched gene sets by most recent prior treatment. For each gene signature name, the number of genes in the signature is shown in parentheses. (A) Enriched gene sets for prior IO (red shaded bars) versus non-IO (blue shaded bars); (B) enriched gene sets for prior anti-PD-1 therapy (red shaded bars) versus anti-CTLA-4 therapy (blue shaded bars). In this analysis, we tested the differentially expressed genes between the most recent prior therapy types after accounting for sex, age, ECOG performance score, disease stage, melanoma subtype, sequencing batch, and the number of expressed genes within each sample. CTLA-4, cytotoxic T lymphocyte antigen-4; ECOG, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group; IO, immunotherapy; NES, normalized enrichment score; p.adj, adjusted p value; PD-1, programmed cell death-1.

Baseline biomarker expression in primary and secondary IO resistance

Baseline biomarker expression, measured by IHC, was assessed in IO-refractory patients with anti-PD-(L)1 as their most recent line of prior therapy and compared between groups with primary versus secondary resistance to the prior anti-PD-(L)1 therapy. The numbers of patients whose most recent prior therapy was anti-PD-(L)1 and who were classified as having primary resistance, secondary resistance, unknown resistance, or inadequate exposure for Parts C and D1 are given in online supplemental table S5. In the pooled analysis, 50.3% of patients in Parts C and D1 were classified as having primary resistance to prior anti-PD-(L)1 therapy, and 38.2% were classified as having secondary resistance.

Expression of LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 by IHC was similar in tumors with primary versus secondary resistance to prior anti-PD-(L)1 therapy (figure 3A). The ORR with nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy among patients with primary versus secondary resistance to prior anti-PD-(L)1 therapy was 11% versus 14%, respectively. RNA-seq analyses revealed that inflammatory gene signatures were significantly (p<0.05) reduced in tumors with primary resistance compared with tumors with secondary resistance, unknown resistance, or inadequate exposure (figure 3B). Signatures of tertiary lymphoid structures and B cells were elevated in secondary resistance tumors. There were no differences in stromal and extracellular matrix signatures in primary versus secondary resistance groups.

Figure 3. Baseline tumor IHC markers (A) and RNA gene signatures (B) by type of resistance to prior anti-PD-(L)1 therapy. Primary resistance was defined as the best response of PD or SD with time to progression <6 months after ≥6 weeks of treatment. Secondary resistance was defined as the best response of CR/PR or SD with time to progression >6 months after ≥6 weeks of treatment. The signature score was determined by the median of the Z-scaled expression of each gene from the signature. Boxes extend from the first to third quartiles, the middle line shows the median biomarker level, and the whiskers extend to the most extreme data point that is no more than 1.5 times the IQR from the box. ****p≤0.0001; ***p≤0.001; **p≤0.01; *p≤0.05. P values compare biomarker levels between primary and secondary IO resistance groups by the Wilcoxon test without multiple comparison correction. aThe length of time between progression on prior anti-PD(L)-1 therapy and collection of baseline tumor samples was not determined. bBaseline tumors may not represent the TME at the time of progression. BMS, Bristol Myers Squibb; CAF, cancer-associated fibroblasts; CR, complete response; EMT, epithelial to mesenchymal transition; IFN-γ, interferon gamma; IHC, immunohistochemistry; IO, immunotherapy; IO-rf, refractory to prior immunotherapy; LAG-3, lymphocyte-activation gene 3; ns, not significant; PD, progressive disease; PD-(L)1, programmed death (ligand)-1; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; TC, tumor cell; TLS, tertiary lymphoid structures; TME, tumor microenvironment.

Baseline TME biomarker expression in 1L and IO-refractory patients

Baseline TME biomarker expression was assessed in, and compared between, 1L and IO-refractory patients using the patient cohort from Part C of RELATIVITY-020. Despite a higher response to the combination of nivolumab and relatlimab in 1L versus IO-refractory patients (ORR 47% vs 11%), baseline expression levels of the IO biomarkers LAG-3, PD-L1, or CD8 by IHC did not differ between 1L and IO-refractory patients, even when the analysis was limited to IO-refractory patients whose most recent prior line of therapy was IO (figure 4). For patients with biomarker-evaluable samples, the ORRs for the 1L and IO-refractory groups were 49% versus 12% (LAG-3), 51% versus 11% (PD-L1), and 48% versus 10% (CD8). Comparing IO-refractory patients who had any type of most recent prior therapy with IO-refractory patients who had IO as their most recent line of therapy, ORRs were 12% versus 11% (LAG-3), 11% versus 11% (PD-L1), and 10% versus 8% (CD8).

Figure 4. Baseline TME expression of LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 in patients from Part C of RELATIVITY-020 including 1L, IO-refractory, and IO-refractory patients whose most recent prior line of therapy was anti-PD-(L)1. Expression levels measured by Mosaic assay. Positivity was determined by image analysis or visual assessment following assay guidelines. Biomarker levels were compared between 1L and IO-rf groups by the Wilcoxon test without multiple comparison correction. Boxes extend from the first to third quartiles, the middle line shows the median biomarker level, and the whiskers extend to the most extreme data point that is no more than 1.5 times the IQR from the box. 1L, patients with treatment-naïve melanoma who received nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy as their first line of therapy; IO, immunotherapy; IO-rf, refractory to prior immunotherapy; LAG-3, lymphocyte-activation gene 3; ns, not significant; PD-(L)1, programmed death (ligand)-1; TC, tumor cell; TME, tumor microenvironment.

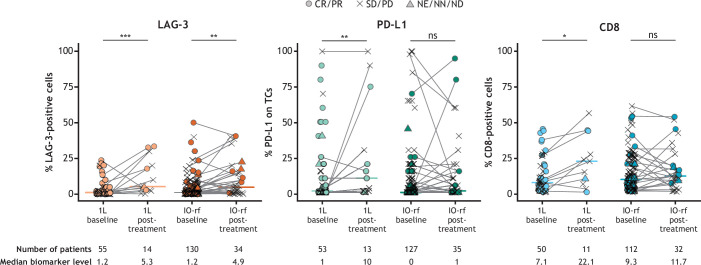

Pre-treatment and post-treatment change in TME biomarker expression in 1L and IO-refractory patients

Using the patient cohort from Part C of RELATIVITY-020, the change in IHC-assessed TME biomarker expression between baseline and on-treatment with nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy was determined for 1L and IO-refractory patients. Significant on-treatment increases in LAG-3 expression were observed in both 1L (p≤0.001) and IO-refractory patients (p≤0.01), with greater increases observed in 1L patients (log2-fold change 1.462 vs 0.731; table 2, figure 5). Significant on-treatment increases in PD-L1 and CD8 expression (p≤0.01 and p≤0.05, respectively) were observed only in 1L patients; however, increased PD-L1 expression was observed in some patients in the IO-refractory group following treatment with nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy.

Table 2. On-treatment fold change in TME biomarker expression in 1L and IO-refractory patients.

| Biomarker | Cohort | Paired samples (n) | Unpaired samples (n) | Log2-fold change | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LAG-3 | 1L | 13 | 43 | 1.462 | ≤0.001 |

| IO-rf | 34 | 96 | 0.731 | ≤0.01 | |

| PD-L1 | 1L | 12 | 42 | 1.51 | ≤0.01 |

| IO-rf | 34 | 94 | 0.429 | ns | |

| CD8 | 1L | 10 | 41 | 0.951 | ≤0.05 |

| IO-rf | 25 | 94 | 0.177 | ns |

IO, immunotherapy; IO-rf, refractory to prior immunotherapy; 1L, patients with treatment-naïve melanoma who received nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy as their first line of therapy; LAG-3, lymphocyte-activation gene 3; ns, not significant; PD-L1, programmed death ligand 1; TME, tumor microenvironment.

Figure 5. On-treatment changes in TME biomarker expression in 1L and IO-refractory patients by response to nivolumab and relatlimab. 1L, patients with treatment-naïve melanoma who received nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy as their first line of therapy; CR, complete response; IO-rf, refractory to prior immunotherapy; LAG-3, lymphocyte-activation gene 3; NA, not applicable; ND, not determined; NE, not evaluable; NN, non-CR/non-PD; ns, not significant; PD, progressive disease; PR, partial response; SD, stable disease; TC, tumor cell; TME, tumor microenvironment.

Gene expression profiles by treatment response

Baseline gene expression profiles associated with responders and non-responders to nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy in RELATIVITY-020 were evaluated in IO-refractory patients from Part D1. Compared with non-responders, responders to combination therapy had higher levels of inflammation-related signatures, including those representing myeloid-derived suppressor cells and M2 macrophages; by contrast, non-responders had higher (p≤0.05) levels of signatures for cell proliferation, and hypoxia (online supplemental figure S5A). In select gene sets, responders had higher levels of inflammation signatures (p≤0.05), Th1 helper and B cells (p≤0.01), chemokine signatures (p≤0.01), and CD8+ T cells (p≤0.05) at baseline, whereas in non-responders, mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK) (p≤0.05) and Myc signatures (p≤0.05) were more pronounced (online supplemental figure S5B).

Discussion

Expression of the immune biomarkers LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 in the TME was significantly higher in IO-refractory patients whose most recent prior line of therapy was immune checkpoint blockade than in patients whose most recent prior line was targeted therapy, radiotherapy, or chemotherapy. These results align with previous reports that immune checkpoint blockade can induce the expression of inflammatory biomarkers,4 5 more robustly than other standard therapies, such as chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or targeted therapies, and thus may have a greater impact on immune modulation within tumors. Upregulation of certain pro-inflammatory cytokines appears to enhance ICI efficacy. For example, immune checkpoint blockade has been shown to induce intratumoral interferon gamma (IFN-γ) production, in turn enhancing ICI treatment efficacy by promoting tumor antigen presentation to CD8+ cytotoxic T lymphocytes; increasing the function of tumor-infiltrating immune cells, such as cytotoxic T lymphocytes, Th1 cells, and macrophages; suppressing regulatory T-cell function; and altering stromal cell function.43 The importance of IFN-γ in treatment efficacy is further supported by an observed association between IFN-γ pathway gene mutations and tumor resistance to ICIs.43

We observed lower levels of LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 expression in IO-refractory tumors from patients most recently treated with targeted therapies compared with those most recently treated with IO, supporting previous research suggesting that targeted therapies may make the TME of IO-refractory tumors less sensitive to further IO.44 However, some IO-refractory patients whose most recent line of therapy was non-IO still responded to nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy, suggesting that baseline biomarker expression alone is not sufficient to predict response to this therapy. Moreover, the higher levels of LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 expression and numerically higher ORR (12.0% vs 9.9%, respectively) observed in patients whose most recent prior therapy was IO versus non-IO suggest that patients who experience disease progression while on anti-PD-(L)1 or anti-CTLA-4 therapies may benefit from subsequent treatment with nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy, which would take advantage of an inflamed TME with no intervening non-IO regimens.

In contrast to the significant differences in baseline tumoral LAG-3 expression by therapy group and response category, baseline peripheral sLAG-3 levels were similar among IO-refractory patients whose most recent line of therapy was IO versus chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or targeted therapy, and among responders versus non-responders to nivolumab and relatlimab. Thus, an association between LAG-3 expression and patient response is more apparent from tumor expression of LAG-3 than from circulating LAG-3 levels. The explanation for this discrepancy remains unknown, owing in part to gaps in knowledge about LAG-3 biology. Although best known for its ability to mediate T-cell inhibition, the signaling mechanism by which LAG-3 acts is not well understood; however, cell surface shedding has been shown to impact LAG-3 expression and inhibitory activity, with increased T-cell suppression in situations where LAG-3 cannot be cleaved.45 While it is known that the disintegrin and metalloprotease domain-containing protein-10 (ADAM10) and ADAM17 cleave the peptide connecting LAG-3 to the cell membrane and release the monomeric soluble form of LAG-3,45 this sLAG-3 is not known to have any biological activity.46 47 It is also not known for how long individual sLAG-3 molecules are retained in the circulation, or the rate at which they are cleared.

Assessment of differential gene expression patterns based on the most recent line of therapy demonstrated that IO is associated with signatures for myeloid cells, while non-IO is associated with stromal factors. Evaluation of gene expression in prior CTLA-4-containing regimens versus non-CTLA-4 IO revealed that both macrophages and stromal factors were associated with prior CTLA-4 IO, rather than anti-PD-(L)1 therapy only.

The similarity of expression of LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 among tumors with primary versus secondary resistance to prior anti-PD-(L)1 therapy implies that there is no clear association between these biomarkers and prior primary or secondary resistance status, and that the LAG-3 pathway may be equally associated with both types of resistance. However, variance in immune-infiltration gene-expression signatures between primary and secondary IO-resistant tumors, such as lower levels of multiple signatures of inflammation in primary resistance samples than in secondary resistance samples, indicates that the resistance subgroups may have distinct TMEs and IO sensitivities that are detectable when more sensitive gene-expression methods are employed over IHC approaches. These results suggest that immunological features of the TME differ between types of ICI resistance, and that studies comparing these features in primary versus secondary resistance to individual immunotherapeutic agents are warranted.

Although levels of IO biomarkers were higher in tumor samples from IO-refractory patients who had IO as their most recent prior therapy than in tumor samples from IO-refractory patients who had non-IO treatment as their most recent therapy, the baseline expression of IO biomarkers was similar in 1L and IO-refractory patients in this study. This suggests that it is unlikely that the variation in treatment response between IO-naïve patients and those with previous IO experience can be fully attributed to differences in expression levels of any of the three individual biomarkers as measured by IHC.

Significant on-treatment increases in LAG-3 expression in both 1L and IO-refractory patients should enable patients who progressed on prior IO to be responsive to the T-cell promoting activity of relatlimab in combination with nivolumab. These results are consistent with a previous analysis of data from RELATIVITY-020 that showed activation of cytotoxic T cells and adaptive NK cells, both LAG-3–expressing cell types, in nivolumab and relatlimab-treated patients with melanoma who were naïve or refractory to prior IO.7 By contrast, PD-L1 and CD8 levels were significantly modulated by nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy only in 1L patients and not in IO-refractory patients, which suggests that LAG-3+ cells within the TME are modulated differently by nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy after prior IO exposure, compared with CD8+ and PD-L1+ TCs within the TME in these patients. This also suggests that LAG-3, CD8, and TC PD-L1 are not interchangeable pharmacodynamic inflammatory biomarkers in IO-refractory patients with advanced melanoma.

Evaluation of baseline gene expression signatures associated with responders showed that several myeloid cell signatures existed, including those representing myeloid-derived suppressor cells, M2 macrophages, and dendritic cells. While some of these signatures may be associated with immune-suppressive cell types, these data could suggest that these signatures are modulated to more favorable phenotypes by prior exposure to IO. By contrast, the many MAPK and proliferation signatures dominating the tumors of non-responders could be due to a higher proliferative capacity of TCs (mitotic index) themselves or, alternatively, other inhibitory stromal cell types. Single-cell approaches would be needed to further resolve the cell types that these signatures are coming from.

The study had some limitations. Information on the duration of time between progression on the most recent prior therapy and the collection of baseline tumor samples in RELATIVITY-020 was not available for a subset of patients in the most recent prior therapy cohort, and it also varied among patients; therefore, the baseline tumor samples may not have been representative of the TME at the time of progression on most recent prior therapy. We also may not have the entire picture of the TME, as not all metastatic sites were equally accessible to biopsy, and primary tumors were not available to evaluate potential changes in phenotypes over time as patients switched from one treatment regimen to another. It is also plausible that some patients who received targeted therapy in later lines had more advanced disease, and that some tumors had been irradiated, as radiotherapy-treated patients were included in the study. There were limited on-treatment samples available for evaluating changes in biomarker levels from baseline to on-treatment between the patients who responded to therapy and those who did not. Finally, the sample sizes were small, particularly for the subgroups of IO-refractory patients whose most recent line of therapy was non-IO; thus, differences in biomarker levels between tumors with primary versus secondary resistance in patients with non-IO as their last line of therapy could not be explored. Samples were also limited for the 1L group, and no sLAG-3 data were available for the 1L group of Part C. Because of the small sample sizes, the results of this study should be interpreted with caution, and additional integrated analysis incorporating the relationship between multiple biomarkers was not feasible. However, future studies with greater statistical power to test associations between biomarker combinations and therapy regimens or outcomes could provide greater insight into which biomarkers may best guide IO treatment decisions for patients with melanoma.

In summary, we conducted exploratory analyses to evaluate baseline and on-treatment immune biomarker expression in the TME of 1L and IO-refractory patients with melanoma in RELATIVITY-020. IO-refractory patients whose most recent prior therapy was IO had elevated tumorous expression of LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 compared with patients whose most recent prior treatment was non-IO, which could mechanistically explain why the former group may be more responsive to treatment with nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy. Additionally, baseline TME expression of LAG-3, PD-L1, and CD8 in patients whose most recent line of therapy was IO was significantly higher in responders to nivolumab and relatlimab than in non-responders. Gene expression signatures associated with immune cell infiltration differed between tumors with primary versus secondary resistance and may reflect distinct TMEs and IO sensitivities in these subgroups. Significant on-treatment increases from baseline in LAG-3 expression in both 1L and IO-refractory patients suggest that the TME of both subgroups is modulated by nivolumab and relatlimab, with greater effects observed in 1L patients. These results provide insight into potentially useful predictive biomarkers and may influence future study designs that test biomarker utility for patient selection; however, considering the retrospective nature of these analyses, more prospective data may be needed to help design such studies and to inform on combinations to overcome IO-resistance. Results from ongoing clinical research are also needed to better understand which patients may derive maximal clinical benefit from inhibition of the LAG-3 and PD-1 pathways and to confirm the mechanisms of action and resistance to nivolumab and relatlimab combination therapy in patients with IO-refractory melanoma.

Supplementary material

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the patients, their families, and all investigators involved in this study. In addition, the authors thank Bin Li for initial contributions to the analyses plan while employed at BMS. Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Sandra Page, PhD, and Laura McArdle, BA, of Spark (a division of Prime, New York, USA), supported by Bristol Myers Squibb, according to Good Publication Practice guidelines.48 The sponsor was involved in the study design and collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. However, ultimate responsibility for opinions, conclusions, and data interpretation lies with the authors.

Footnotes

Funding: This study was sponsored by Bristol Myers Squibb.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Ethics approval: This study was conducted in accordance with Good Clinical Practice as defined by the International Conference on Harmonization and in accordance with the ethical principles underlying European Union Directive 2001/20/EC and the United States Code of Federal Regulations, Title 21, Part 50 (21CFR50). The protocol was approved by each study site’s independent ethics committee or institutional review board prior to study initiation. The institutional review board of the principal investigator was Comitato Etico Fondazione Pascale, IRCCS, Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori, IRB number 79/15. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

Data availability free text: Bristol Myers Squibb will honor legitimate requests for clinical trial data from qualified researchers with a clearly defined scientific objective. Data-sharing requests will be considered for Phase II–IV interventional clinical trials that are completed on or after January 1, 2008. In addition, primary results must have been published in peer-reviewed journals and the medicines or indications approved in the USA, EU, and other designated markets. Sharing is also subject to protection of patient privacy and respect for the patient’s informed consent. Data considered for sharing may include non-identifiable patient-level and study-level clinical trial data, full clinical study reports, and protocols. Requests to access clinical trial data may be submitted using the enquiry form at https://vivli.org/ourmember/bristol-myers-squibb/.

Data availability statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.

References

- 1.Ascierto PA, Lipson EJ, Dummer R, et al. Nivolumab and Relatlimab in Patients With Advanced Melanoma That Had Progressed on Anti-Programmed Death-1/Programmed Death Ligand 1 Therapy: Results From the Phase I/IIa RELATIVITY-020 Trial. J Clin Oncol. 2023;41:2724–35. doi: 10.1200/JCO.22.02072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jessurun CAC, Vos JAM, Limpens J, et al. Biomarkers for Response of Melanoma Patients to Immune Checkpoint Inhibitors: A Systematic Review. Front Oncol. 2017;7:233. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2017.00233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Larkin J, Chiarion-Sileni V, Gonzalez R, et al. Combined Nivolumab and Ipilimumab or Monotherapy in Untreated Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:23–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1504030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kates M, Nirschl TR, Baras AS, et al. Combined Next-generation Sequencing and Flow Cytometry Analysis for an Anti-PD-L1 Partial Responder over Time: An Exploration of Mechanisms of PD-L1 Activity and Resistance in Bladder Cancer. Eur Urol Oncol. 2021;4:117–20. doi: 10.1016/j.euo.2019.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Saleh R, Toor SM, Khalaf S, et al. Breast Cancer Cells and PD-1/PD-L1 Blockade Upregulate the Expression of PD-1, CTLA-4, TIM-3 and LAG-3 Immune Checkpoints in CD4+ T Cells. Vaccines (Basel) 2019;7:149. doi: 10.3390/vaccines7040149. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chen P-L, Roh W, Reuben A, et al. Analysis of Immune Signatures in Longitudinal Tumor Samples Yields Insight into Biomarkers of Response and Mechanisms of Resistance to Immune Checkpoint Blockade. Cancer Discov. 2016;6:827–37. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-15-1545. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huuhtanen J, Kasanen H, Peltola K, et al. Single-cell characterization of anti-LAG-3 and anti-PD-1 combination treatment in patients with melanoma. J Clin Invest. 2023;133:e164809. doi: 10.1172/JCI164809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bristol Myers Squibb OPDUALAG™ (nivolumab and relatlimab) 2024. [13-Aug-2024]. https://packageinserts.bms.com/pi/pi_opdualag.pdf Available. Accessed.

- 9.European Medicines Agency Opdualag: EPAR - product information. 2022. [18-Apr-2024]. https://www.ema.europa.eu/en/medicines/human/EPAR/opdualag#product-info Available. Accessed.

- 10.Tawbi HA, Schadendorf D, Lipson EJ, et al. Relatlimab and Nivolumab versus Nivolumab in Untreated Advanced Melanoma. N Engl J Med. 2022;386:24–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2109970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Eisenhauer EA, Therasse P, Bogaerts J, et al. New response evaluation criteria in solid tumours: revised RECIST guideline (version 1.1) Eur J Cancer. 2009;45:228–47. doi: 10.1016/j.ejca.2008.10.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kluger HM, Tawbi HA, Ascierto ML, et al. Defining tumor resistance to PD-1 pathway blockade: recommendations from the first meeting of the SITC Immunotherapy Resistance Taskforce. J Immunother Cancer. 2020;8:e000398. doi: 10.1136/jitc-2019-000398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Szabo PM, Pant S, Ely S, et al. Development and Performance of a CD8 Gene Signature for Characterizing Inflammation in the Tumor Microenvironment across Multiple Tumor Types. J Mol Diagn. 2021;23:1159–73. doi: 10.1016/j.jmoldx.2021.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson L, McCune B, Locke D, et al. Development of a LAG-3 immunohistochemistry assay for melanoma. J Clin Pathol. 2023;76:591–8. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2022-208254. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Buchwald ZS, Wynne J, Nasti TH, et al. Radiation, Immune Checkpoint Blockade and the Abscopal Effect: A Critical Review on Timing, Dose and Fractionation. Front Oncol. 2018;8:612. doi: 10.3389/fonc.2018.00612. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ngwa W, Irabor OC, Schoenfeld JD, et al. Using immunotherapy to boost the abscopal effect. Nat Rev Cancer. 2018;18:313–22. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2018.6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ayers M, Lunceford J, Nebozhyn M, et al. IFN-γ-related mRNA profile predicts clinical response to PD-1 blockade. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:2930–40. doi: 10.1172/JCI91190. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Buechler MB, Pradhan RN, Krishnamurty AT, et al. Cross-tissue organization of the fibroblast lineage. Nature. 2021;593:575–9. doi: 10.1038/s41586-021-03549-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coppola D, Nebozhyn M, Khalil F, et al. Unique ectopic lymph node-like structures present in human primary colorectal carcinoma are identified by immune gene array profiling. Am J Pathol. 2011;179:37–45. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cristescu R, Nebozhyn M, Zhang C, et al. Transcriptomic Determinants of Response to Pembrolizumab Monotherapy across Solid Tumor Types. Clin Cancer Res. 2022;28:1680–9. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-21-3329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Dry JR, Pavey S, Pratilas CA, et al. Transcriptional pathway signatures predict MEK addiction and response to selumetinib (AZD6244) Cancer Res. 2010;70:2264–73. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-1577. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Elyada E, Bolisetty M, Laise P, et al. Cross-Species Single-Cell Analysis of Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma Reveals Antigen-Presenting Cancer-Associated Fibroblasts. Cancer Discov. 2019;9:1102–23. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-19-0094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ghelani A, Bates D, Conner K, et al. Defining the Threshold IL-2 Signal Required for Induction of Selective Treg Cell Responses Using Engineered IL-2 Muteins. Front Immunol. 2020;11:1106. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.01106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guinney J, Ferté C, Dry J, et al. Modeling RAS phenotype in colorectal cancer uncovers novel molecular traits of RAS dependency and improves prediction of response to targeted agents in patients. Clin Cancer Res. 2014;20:265–72. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-13-1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Gupta A, Towers C, Willenbrock F, et al. Dual-specificity protein phosphatase DUSP4 regulates response to MEK inhibition in BRAF wild-type melanoma. Br J Cancer. 2020;122:506–16. doi: 10.1038/s41416-019-0673-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hodi FS, Wolchok JD, Schadendorf D, et al. TMB and Inflammatory Gene Expression Associated with Clinical Outcomes following Immunotherapy in Advanced Melanoma. Cancer Immunol Res. 2021;9:1202–13. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-20-0983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Insua-Rodríguez J, Pein M, Hongu T, et al. Stress signaling in breast cancer cells induces matrix components that promote chemoresistant metastasis. EMBO Mol Med. 2018;10:e9003. doi: 10.15252/emmm.201809003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liberzon A, Birger C, Thorvaldsdóttir H, et al. The Molecular Signatures Database (MSigDB) hallmark gene set collection. Cell Syst. 2015;1:417–25. doi: 10.1016/j.cels.2015.12.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Loboda A, Nebozhyn M, Klinghoffer R, et al. A gene expression signature of RAS pathway dependence predicts response to PI3K and RAS pathway inhibitors and expands the population of RAS pathway activated tumors. BMC Med Genomics. 2010;3:26. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-3-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Loboda A, Nebozhyn MV, Watters JW, et al. EMT is the dominant program in human colon cancer. BMC Med Genomics. 2011;4:9. doi: 10.1186/1755-8794-4-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.McDermott DF, Huseni MA, Atkins MB, et al. Clinical activity and molecular correlates of response to atezolizumab alone or in combination with bevacizumab versus sunitinib in renal cell carcinoma. Nat Med. 2018;24:749–57. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0053-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Middleton G, Yang Y, Campbell CD, et al. BRAF-Mutant Transcriptional Subtypes Predict Outcome of Combined BRAF, MEK, and EGFR Blockade with Dabrafenib, Trametinib, and Panitumumab in Patients with Colorectal Cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:2466–76. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3579. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nshizirungu JP, Bennis S, Mellouki I, et al. Reproduction of the Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) and Asian Cancer Research Group (ACRG) Gastric Cancer Molecular Classifications and Their Association with Clinicopathological Characteristics and Overall Survival in Moroccan Patients. Dis Markers. 2021;2021:9980410. doi: 10.1155/2021/9980410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Pek M, Yatim SMJM, Chen Y, et al. Oncogenic KRAS-associated gene signature defines co-targeting of CDK4/6 and MEK as a viable therapeutic strategy in colorectal cancer. Oncogene. 2017;36:4975–86. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Siemers NO, Holloway JL, Chang H, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies genetic correlates of immune infiltrates in solid tumors. PLoS ONE. 2017;12:e0179726. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0179726. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Spranger S, Bao R, Gajewski TF. Melanoma-intrinsic β-catenin signalling prevents anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2015;523:231–5. doi: 10.1038/nature14404. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Tokunaga R, Nakagawa S, Sakamoto Y, et al. 12-Chemokine signature, a predictor of tumor recurrence in colorectal cancer. Int J Cancer. 2020;147:532–41. doi: 10.1002/ijc.32982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zhou X, Li W, Yang J, et al. Tertiary lymphoid structure stratifies glioma into three distinct tumor subtypes. Aging (Albany NY) 2021;13:26063–94. doi: 10.18632/aging.203798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Bagaev A, Kotlov N, Nomie K, et al. Conserved pan-cancer microenvironment subtypes predict response to immunotherapy. Cancer Cell. 2021;39:845–65. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2021.04.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cabrita R, Lauss M, Sanna A, et al. Tertiary lymphoid structures improve immunotherapy and survival in melanoma. Nature. 2020;577:561–5. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1914-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Doering TA, Crawford A, Angelosanto JM, et al. Network analysis reveals centrally connected genes and pathways involved in CD8+ T cell exhaustion versus memory. Immunity. 2012;37:1130–44. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.08.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gao J, Navai N, Alhalabi O, et al. Neoadjuvant PD-L1 plus CTLA-4 blockade in patients with cisplatin-ineligible operable high-risk urothelial carcinoma. Nat Med. 2020;26:1845–51. doi: 10.1038/s41591-020-1086-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ivashkiv LB. IFNγ: signalling, epigenetics and roles in immunity, metabolism, disease and cancer immunotherapy. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18:545–58. doi: 10.1038/s41577-018-0029-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Haas L, Elewaut A, Gerard CL, et al. Acquired resistance to anti-MAPK targeted therapy confers an immune-evasive tumor microenvironment and cross-resistance to immunotherapy in melanoma. Nat Cancer. 2021;2:693–708. doi: 10.1038/s43018-021-00221-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Andrews LP, Somasundaram A, Moskovitz JM, et al. Resistance to PD1 blockade in the absence of metalloprotease-mediated LAG3 shedding. Sci Immunol. 2020;5:eabc2728. doi: 10.1126/sciimmunol.abc2728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Li N, Workman CJ, Martin SM, et al. Biochemical analysis of the regulatory T cell protein lymphocyte activation gene-3 (LAG-3; CD223) J Immunol. 2004;173:6806–12. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.173.11.6806. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Aggarwal V, Workman CJ, Vignali DAA. LAG-3 as the third checkpoint inhibitor. Nat Immunol. 2023;24:1415–22. doi: 10.1038/s41590-023-01569-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.DeTora LM, Toroser D, Sykes A, et al. Good Publication Practice (GPP) Guidelines for Company-Sponsored Biomedical Research: 2022 Update. Ann Intern Med. 2022;175:1298–4. doi: 10.7326/M22-1460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.