Abstract

Cytochrome P450 1B1 (CYP1B1) metabolizes endogenous and xenobiotic substrates, including steroids and fatty acids. It is implicated in the metabolism of compounds essential for eye development and is a causative gene in primary congenital glaucoma (PCG). However, CYP1B1’s role in PCG and related eye disorders and neurobehavioral function is poorly understood. To investigate the role of Cyp1b1 this study used a novel CRISPR-Cas9 generated Cyp1b1 mutant zebrafish (Danio rerio) line. Behavioral, metabolomic, and transcriptomic analyses were performed to determine the molecular and behavioral consequences of the mutant Cyp1b1. Further we aimed to distinguish a visual defect from other neurological effects. Larval mutant zebrafish were hyperactive during the vision-based larval photomotor response assay but behaved normally in the sound-based larval startle response assay. Adult mutants exhibited normal locomotion but altered interactions with other fish. In vision and hearing-based assays, mutant fish showed altered behavior to visual stimuli and reduced auditory responses. Mass spectrometry-based metabolomics analysis revealed 26 differentially abundant metabolites in the eye and 49 in the brain between the genotypes, with perturbed KEGG pathways related to lipid, nucleotide, and amino acid metabolism. RNA sequencing identified 95 differentially expressed genes in the eye and 45 in the brain. Changes in arachidonic and retinoic acid abundance were observed and potentially modulated by altered expression of CYP 1, 2, and 3 family enzymes. While these findings could not point to specific ocular defects over other neurobehavioral phenotypes, behavioral assays and omics analyses highlighted the role of Cyp1b1 in maintaining metabolic homeostasis and the behavioral consequences due to its loss.

Keywords: Cytochrome P450, Untargeted metabolomics, Mutliomics, Zebrafish, CYP1B1, Eye disorders

1. Introduction

1.1. CYP1B1

Cytochrome P450 1B1 (CYP1B1) is a member of the CYP superfamily: heme enzymes involved in the oxidative metabolism of a broad range of endogenous and xenobiotic compounds. In humans CYP1 family members are in part transcriptionally regulated by the aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AHR) and are known to activate a variety of carcinogens including polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) (Murray et al., 2001). Additionally, CYP1B1 metabolizes endogenous bioactive compounds including steroids, fatty acids, and retinol. It is thought to be involved in the metabolism of estradiol, arachidonic acid, retinoic acid, and melatonin (Li et al., 2017). CYP1B1’s hydrophobic N-terminal region anchors it to the endoplasmic reticulum while the C-terminal region contains a conserved Cys loop region containing the cysteine ligand which is responsible for heme binding. Substrate recognition sites (SRSs) span the length of the protein and face the substrate binding pocket (Achary et al., 2006; Itoh et al., 2010). CYP1B1 is mainly expressed extrahepatically throughout the body in the bone marrow, brain, breast, intestine, kidney, prostate, and ocular tissues. During human fetal development CYP1B1 is expresses in the hindbrain, neural crest, and eyes. Early expression of CYP1B1 in humans coupled with its role in steroid and fatty acid metabolism suggests that CYP1B1 is important for proper development and maintenance of metabolic homeostasis (Song et al., 2022), although CYP1B1 mutant rodent models exhibit no gross abnormal phenotypes (Gonzalez and Kimura, 2001).

1.2. CYP1B1 and primary cogenital glaucoma

In the eye CYP1B1 is primarily expressed in the ciliary body, iris, cornea, trabecular meshwork, and retina. Loss-of-function mutations in the human CYP1B1 are the primary gene mutations linked to autosomal recessive primary congenital glaucoma (PCG) (Song et al., 2022). While rare, PCG is the most common form of glaucoma in infants with more than 80% of cases observed in the first year of life (Vasiliou and Gonzalez, 2008). PCG mainly presents with developmental defects of the trabecular meshwork and Schlemm’s canal. Defects in their structure leads to poor aqueous fluid drainage and an increase in intraocular pressure (IOP) causing cell death in the retina and optic nerve leading to permanent vision loss (Falero-Perez et al., 2018). CYP1B1’s role in PCG disease etiology is supported by evidence of CYP1B1’s strong expression in the eye and the prevalence of CYP1B1 mutations in PCG. Further, Cyp1b1 may be an important source of retinoic acid as it has been shown to metabolize its synthesis (Chavarria-Soley et al., 2008; Kaur et al., 2011). Retinoic acid is a molecule involved in developmental signaling in tissues such as the eye and brain. (Cunningham and Duester, 2015). However, a detailed mechanism of CYP1B1’s role in PCG progression remains unknown.

1.3. Zebrafish Cyp1b1

There have been several studies that demonstrate Cyp1b1 null mice develop abnormalities of the eye similar to PCG like reduced retinal vasculature, trabecular meshwork defects, and collagen loss. Further CYP1B1 protein was observed in the ciliary epithelium corneal epithelium and retina in WT mice (Choudhary et al., 2007; Falero-Perez et al., 2019; Teixeira et al., 2015). The present study sought to use cyp1b1 null zebrafish (Danio rerio) to investigate metabolic and behavioral differences due to the conserved nature of eye development pathways. Additionally, zebrafish have high fecundity and rapid ex-utero development making them ideal organisms for rapid physiological screening (Hill et al., 2005). 71.4% of human genes have at least one zebrafish ortholog demonstrating highly conserved genetics compared to mammals (Howe et al., 2013).

While humans have three members of the CYP1 family (CYP1A1, CYP1A2, and CYP1B1), zebrafish have five (Cyp1a, Cyp1b1, Cyp1c1, Cyp1c2, and Cyp1d1) (Goldstone et al., 2009). The two mammalian CYP1A genes are the result of tandem duplication in tetrapods, while fish typically have a single cyp1a gene (Goldstone and Stegeman, 2006). Zebrafish cyp1b1 shares synteny with and is highly similar to the single CYP1B1 gene found in all vertebrates and contains the six conserved SRS domains and Cys loop found in human CYP1B1 (Itoh et al., 2010). However, the zebrafish cyp1b1 gene consists of two total exons while human CYP1B1 is expressed as three (two coding) exons (Goldstone et al., 2010; Tang et al., 1996). In humans the CYP1C gene was likely lost while CYP1D1 was pseudogenized (Goldstone et al., 2009; Jonsson et al., 2011; Uno et al., 2023; Uno et al., 2011).

The CYP1 family’s diversification suggests that while there might be overlap in substrate specificity, each enzyme likely evolved to fulfill distinct physiological roles. The varied presence of Cyp1c and Cyp1d enzymes suggests functional adaptations or expression differences in species with these functional enzymes, with the result that their Cyp1b1 may not directly parallel the functions of CYP1B1 in rodents or humans, especially in specialized tissues like the eye (Scornaienchi et al., 2010). While the presence of Cyp1c and Cyp1d enzymes in zebrafish adds complexity to interpreting knockout studies for rodent and human comparisons, it also offers a unique opportunity to uncover novel aspects of the CYP1 family’s role in eye development. By knocking out Cyp1b1 in zebrafish, we aim to uncover its specific role in the development of ocular diseases. While there might be some functional overlap with Cyp1a, Cyp1c, and Cyp1d isoforms, the unique contribution of Cyp1b1 will be highlighted through this targeted approach.

A previous study, Alexandre-Moreno et al., 2021, targeted Cyp1b1’s exon one in zebrafish using CRISPR/Cas9. The study reports that crispants displayed changes in egg volume, early developmental delays, and abnormal cranial and jaw morphology at 6 days post fertilization (dpf). Adult mutants also presented craniofacial defects. However, adult mutant eye morphology, including glaucoma related tissues like the anterior chamber angles and the cornea, was similar to the wildtype (WT). The study did not characterize behavior or metabolomics in adults or larvae and while RNA-seq was performed using 7dpf larvae it was not performed with adult tissues (Alexandre-Moreno et al., 2021).

The line used in the present study (named wh5) was generated using CRISPR Cas9. WT Cyp1b1 is 526 amino acids (aa) long while the wh5 mutant Cyp1b1 is truncated at 388aa by an early stop codon. Behavioral assays were performed to look for loss of visual acuity or altered response to visual stimuli and investigate potential causes using omics analysis. Multiple behavioral assays were performed at the larval and adult life stages including those that test visual and sensory acuity. The larval photomotor response (LPR) assay and larval startle response (LSR) assay were performed. Adult behavior tests were performed including the shoaling, free swim, and sideview assays. Metabolomic and transcriptomic analyses were performed on adult eyes and brain to investigate system wide molecular changes. Eyes and brains were chosen due to their importance in vision and behavior. Ultra-performance liquid chromatography high resolution mass spectrometry (UPLC-HRMS) based untargeted metabolomics were performed to investigate the abundance of potential Cyp1b1 metabolites in WT and mutant zebrafish. RNA-sequencing was performed to investigate differentially expressed genes (DEGs) between the genotypes. Metabolomic and RNA-seq data were analyzed individually and in a joint pathway analysis to elucidate perturbed pathways in these tissues.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Creation and generation of a Cyp1b1 Wh5 mutant zebrafish line

2.1.1. Design, assembly, and preparation of single-guide RNA

Three separate single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) were generated. Each targeted a central region of cyp1b1’s exon 2, chosen to bracket the cysteine ligand responsible for heme prosthetic group binding. Even in the presence of accidentally generated alternatively spliced gene products, the lack of the cysteine ligand will not result in a functional P450 protein.

sgRNAs were synthesized from double-stranded DNA templates generated by PCR described in Salanga et al., 2020 and adapted from Bassett et al., 2013 (Bassett et al., 2013; Salanga et al., 2020). Briefly, for each sgRNA target site, target-specific forward primers with 5’ T7 polymerase sites and a universal reverse primer (0.5 μM each) were combined in a 100 μL reaction also containing 200 nM dNTPS (N0447, New England Biolabs (NEB), Ipswich, MA), 0.02 U/μL Q5 DNA Polymerase (M0491, NEB, Ipswich, MA), and 1X Q5 Reaction Buffer (B9027, NEB, Ipswich, MA). Amplification was confirmed by visualizing 1/10th of each reaction on 2% agarose gel stained with SYBR safe DNA stain (S33102, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). PCR products were then purified using a QIAquick PCR cleanup kit (28106, Qiagen, Hilden, Germany), following the product instructions. In vitro RNA synthesis was performed using a MAXIscript T7 Transcription kit (AM1312, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) and 250 ng of purified PCR product as the template in a 25 μL reaction volume. The assembled reaction was incubated at 37°C for 5 hours, then 1 μL turboDNAse (AM2238, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was added and the mixture incubated for an additional 15 min at 37°C. The reaction was stopped and purified by adding 10 μL 3M sodium acetate pH 5.2, 1 μL glycol (tracer), and 67 μL H2O, then performing a phenol-chloroform phase extraction and ethanol precipitation, the dried RNA pellets were resuspended in 15 μL H2O. To confirm sgRNA synthesis, 1/15th of the product was visualized on a 2% agarose gel stained with SYBR safe DNA stain. Single guide RNA concentration was determined by nanodrop absorbance.

2.1.2. Embryo injection

Single guide RNAs were pooled to a final concentration of approximately 42 ng/μL per RNA (250 ng/μL combined concentration) and mixed with Cas9 recombinant protein (CP-01, PNA Bio Inc., Newbury Park, CA) and water to achieve a final concentration of 500 ng/μL. Injection volumes of 1–2 nL (125–250 ng pooled sgRNA + 1–2 μg Cas9 protein) were delivered immediately ventral to the blastodisc of 1-cell AB strain zygotes using a PV-820 pneumatic microinjector (World Precision Instruments (WPI), Sarasota, FL), and injection needles pulled from borosilicate capillary tubes (TW100F-4, WPI, Sarasota, FL) using a P-30 vertical pipette puller (Sutter Instruments, Novato, CA).

2.1.3. Founder screening

Five F0 putative crispants were sacrificed at 24 hpi (hours post-injection), and genomic DNA was isolated using DNAzol following the manufacturer’s protocol (J60637AH, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA). Endpoint PCR using primers was performed, and the appearance of shortened amplicons relative to control indicated some editing occurred for all five crispant extracts. See primers used in supplementary materials.

Once potential founder fish that had been injected as embryos were adults, they were outcrossed with wildtype AB zebrafish. The offspring were genotyped to ensure that the mutation had been carried through the line. A founder fish was selected by visibly identifying PCR product bands that had moved further down a gel following electrophoresis of the amplified PCR product. Mutations were confirmed using Sanger sequencing (Eurofins Genomics, Louisville, KY), and have been deposited with Zfin (zfin.org/) as wh5. Although the mutations result in a premature stop codon, it is possible that a truncated protein could be created. However, as the coding region for the cysteine ligand is missing from the genome, no protein producing a P450 can be translated, which should result in the complete loss of Cyp1b1 activity.

2.2. Genotyping

Genotyping was performed using PCR. Adult zebrafish fin clips, larvae, or embryos were digested in 40 μL of 50 mM NaOH at 95°C for 15 min. 4 μL of 1M Tris was added to the lysate followed by 100 μL of water. The lysate was then spun down on a micro centrifuge for 5 min. Master mix was prepared as follows using a KOD Hot Start DNA Polymerase kit (71086, Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA): 2.5 μL of 10X PCR Buffer, 1.0 μL of 25 mM MgSO4, 2.5 μL of dNTP Mix (2 mM), 15 μL of H2O, 0.75 μL of both primers (Eurofins Genomics, Louisville, KY), and 0.5 μL of KOD Hot Start DNA Polymerase (1.0 U/μl). 2 μL of the gDNA lysate was added to the master mix. Initial denaturation was performed at 95°C for 2min followed by 35 cycles of amplification (95°C for 20 s, 60°C for 10 s, 70°C for 10 s) followed by 70°C for 5 min. WT vs mutant bands can be resolved on a gel following electrophoresis. See primers used in supplementary materials.

2.2.1. Fish husbandry

The wh5 Cyp1b1 mutant line was shipped from Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute (Falmouth, MA) to the Sinnhuber Aquatic Research Laboratory (SARL) at Oregon State University (Corvallis, OR) in 2019. They were maintained according to Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee protocols (IACUC-2021–0166). Fish received from the AB background were crossed with Tropical 5D fish at SARL to increase genetic diversity and decrease background malformation. Adult fish were raised in recirculating filtered water supplemented with Instant Ocean salts in densities of approximately 30 fish/6 L tank at 28°C under a 14/10 h light/dark cycle. Adult zebrafish were fed GEMMA Micro 300 or 500 (Skretting, Inc., Fontaine les Vervins, France) twice a day, and larval and juvenile zebrafish were fed GEMMA Micro 75 and 150, respectively, 3 times a day (Barton et al., 2016). One male and one female fish were placed in spawning baskets (Techniplast S.p.A., Buguggiate, Italy) separated by a gate which was removed at 08:00 the morning of spawning. Alternatively, 20–30 fish of each sex were placed in an iSpawn-s (Techniplast S.p.A., Buguggiate, Italy) separated by a gate which was removed at 08:00 the morning of spawning. The embryos were subsequently collected, staged, and maintained in embryo medium (EM) in a 28°C incubator (Westerfield, 2007). The EM formula was as follows: 15mM NaCl, 0.5mM KCl, 1mM MgSO4, 0.15mM KH2PO4, 0.05mM Na2HPO4, and 0.7mM NaHCO3 (Mandrell et al., 2012).

2.2.2. Larval morphological and behavior assessments

2.2.2.1. Larval photomotor response (LPR).

LPR is used to assess photoinduced larval locomotor activity at 120 hours post feralization (hpf). Swimming activity in larvae is typically low under bright light, but three to ten times higher in the dark. Impacts to brain and visual pathways can be assessed using LPR. The assay has been used in the past to assess normal development in CRISPR generated mutant lines (Dasgupta et al., 2022). Fish were spawned as described above and embryos with chorions intact were loaded into 96-well plates (Corning Inc., Corning, NY). Zebrafish embryos hatch at ~72 hpf. Each plate was split between half WT and mutant embryos. At 120 hpf plates were placed into Viewpoint Zebraboxes (ViewPoint Behavior Technology, Lyons, France) and the assay was performed. ViewPoint Zebrabox software was used to track each larva during the 24 min assay which includes a 3 min period of light followed by a 3 min period of dark. The positional information of each larva was sampled once every 6 s and the raw data files were analyzed using a custom R script. Total movement during the first light and dark period was calculated and the genotypes’ responses were compared using one-way ANOVA (p ≤ 0.05) (Knecht et al., 2017). 180 larvae of each genotype were run through this assay.

2.2.2.2. Larval startle response (LSR).

The LSR assay assesses neurobehavioral development by monitoring larval zebrafishes’ reaction to an auditory stimulus and can be integrated into the final 2 min of the LPR assay. Following the end of the LPR assay a single 600 Hz vibrational stimulus is used to startle the larvae under visible light. The movement of the larvae is tracked by the ViewPoint Zebrabox software. Area under the curve was used to describe the response to the audio stimulus. Area under the curve is determined by plotting time (sec) vs movement (mm) and calculating the geometric area under the curve formed. This is done to consider not just the behavior during the startle, but behavior leading up to and following it. The genotypes’ responses were compared using one-way ANOVA (p ≤ 0.05) (Dasgupta et al., 2022; Dasgupta et al., 2020). 180 larvae of each genotype were run through this assay.

2.2.2.3. Larval morphological assessment.

At 24 hpf and at 120 hpf following LPR and LSR embryonic and larval zebrafish morphological phenotype was assessed using 9 morphology endpoints as binary outcomes (Truong et al., 2022).

2.3. Adult behavior assessments

2.3.1. Shoaling

The shoaling assay assesses social interaction. 16 and 12 groups (two males, two females) of WT and mutant fish, respectively, were evaluated. Each group was placed into a 1.7 L (26 × 5 × 12 cm) tank and recorded for 30 min while swimming uninterrupted. The movement of each fish was tracked using PhenoRack software (ViewPoint Behavior Technology, Lyons, France). Three endpoints were assessed by sampling every 30 s. Inter-individual distance (IID) measures the average distance between all fish while swimming. Nearest-neighbor distance (NND) measures the average distance between the two nearest fish while swimming. Finally, the average speed of the fish was measured. The first 25 min of the assay are used to acclimate the fish. Only the final 5 min are used in the statistical analysis. Statistical analysis was performed using one-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey post-hoc test (p ≤ 0.05) (Knecht et al., 2017; Rericha et al., 2022).

2.3.2. Free swim

The free swim assay assesses locomotion. A single fish is placed into the same tank used for the shoaling assay. The assay duration, acclimation period, and sampling duration are the same as the shoaling assay. 32 male and 30 female WT fish and 32 male and 24 female mutant fish were tested. Distance travelled by each fish was assessed by sampling position every 30 s using PhenoRack software. Statistical analysis was performed using two-way ANOVA considering genotype and sex followed by a Tukey post-hoc test (p ≤ 0.05) (Knecht et al., 2017; Rericha et al., 2022).

2.3.3. Predator and startle response (Sideview Assay)

The zebrafish visual imaging system (zVIS or sideview) is used to assess adult zebrafishes’ visual acuity and behavior by displaying prerecorded video on a digital monitor. It also assesses the reaction to a series of auditory stimuli. Each sideview unit can hold eight (10 × 10 × 13 cm) tanks. One side of each tank is flanked by an LCD computer monitor. Each tank houses an individual fish which is tracked by a camera mounted above. Positional information of each fish was collected by PhenoRack software sampling once per second. 37 male and 24 female WT fish and 33 male and 24 female mutant fish were tested. The 37 min assay includes a 20 min acclimation period, a 5 min predator response assay, and a 2 min startle response. During the predator portion of the assay a predator fish is displayed on the monitors. The analysis of the predator was performed as follows. The tank, as viewed from above, was divided into a near zone, the 1/3 closest to the monitor, and a far zone, the 2/3 of the tank furthest from the monitor. The percent time in each zone was measured the minute before and during the duration of the video. Statistical analysis was performed using three-way ANOVA considering genotype, sex, and video status (before or during video duration). This was followed by a Tukey post-hoc test (p ≤ 0.05). The startle response consisted of 10 consecutive vibrations every 20 s generated using an electronic vibrational unit. The startle response assessed two endpoints: habituation to the first five vibrations and the mean distance traveled by each genotype. Statistical analysis was performed using three-way ANOVA followed by a Tukey post-hoc test (p ≤ 0.05) (Knecht et al., 2017; Rericha et al., 2022). Fish were returned to their standard housing following the assay.

2.4. UPLC-HRMS-based metabolomics

2.4.1. Eye and brain dissections

The ten-adult zebrafish of each sex and genotype used in the dissection were also run through the behavior assays. 1.5 mL screw cap Rhino Tubes (TUBE1R5-S, Next Advance Inc., Troy, NY) were prefilled with 300 mg of 0.5 mm zirconium oxide lysis beads (ZROB05, Next Advance Inc., Troy, NY) and weighed following preparation. Each zebrafish was euthanized by submersion in an ice bath for 3 min then weighed and measured. The entire brain was dissected and placed into the prepared Rhino tube, the cap was closed tightly, the tube was reweighed to get the accurate mass of each brain, and the sample was flash frozen in liquid nitrogen. Pairs of eyes were dissected immediately after the brain and prepared in the same way. Samples were stored at −80°C until further processing. Statistical analysis of weight and length between genotypes was performed using one-way ANOVA (p ≤ 0.05).

2.4.2. Metabolite extraction

On the day of metabolite extraction an 80:20 methanol:water mixture (Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) was added to the prepared sample (300 μL for eye, 200 μL for brain). Samples were not allowed to thaw and were immediately homogenized using a Precellys 24 homogenizer (Bertin Technologies SAS, Montigny-le-Bretonneux, France) set to three 15 s cycles at 5500 rpm. Homogenate (200 μL for eye, 150 μL for brain) was transferred to clean 1.5 mL vials (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) and stored at −20°C overnight. The following day the samples were centrifuged at 13,000 g for 15 min at 4°C. Supernatant was recovered (150 μL for eye, 100 μL for brain) and transferred to LCMS vials with inserts (MicroSolv, Greater Wilmington, NC). 1 mg/mL verapamil (Sigma-Aldrich, Burlington, MA) was added (5 μL for eye, 3 μL for brain) to each vial as an internal standard. Solvent blanks (80:20 methanol:water) and quality control pooled samples (5 μL of each sample) were prepared for both the eye and brain samples.

2.4.3. UPLC-HRMS analysis

We analyzed the fish brain and eye metabolomes with an ultra-high performance reverse phase liquid chromatography system (Sciex ExionLC AD, AB Sciex LLC, Framingham, MA) coupled to a high-resolution mass spectrometer (Sciex ZenoTOF 7600, AB Sciex LLC, Framingham, MA). For chromatographic separation we used a phenyl-3 stationary phase column (Inertsil Phenyl-3, 4.6 × 150 mm; GL Sciences Inc., Tokyo, Japan) and analytical conditions were adapted from Garcia-Jaramillo et al., 2020 (Garcia-Jaramillo et al., 2020). Column temperature was maintained at 50°C with a flow rate of 0.6 mL/min. The mobile phases selected for LC analysis were 100% water containing 0.1% formic acid (solution A) and 100% methanol containing 0.1% formic acid (solution B). The flow gradient was held at 5% B for 1 min, then a 10 min linear gradient from 5–30% B was performed, followed by a 12 min linear gradient to 98% B. The flow gradient was held at 98% B for 12 min, followed by a 2 min linear gradient back to 5% B. The flow gradient was held at 5% B for the remaining 8 min. Injection volume was 5 μL and each sample was sampled once. We randomized samples, performed auto-calibration mass every 5 samples, and analyzed a pooled quality control and an instrument blank every 10 samples. Data was acquired in the information-dependent acquisition (IDA) mode, and in both positive and negative electrospray ionization (ESI) modes. Spray voltage was 5500 V and −4500 V for positive and negative ion modes, respectively. Gas pressure and temperature was kept at 45 PSI and 500°C, respectively.

2.4.4. Data processing

MS-Dial software (Tsugawa et al., 2015) (RIKEN, Yokohama City, Japan) was used to process the raw LCMS data. Metabolites were identified by matching our data to our in house curated spectral metabolites library (IROA Technologies LLC, Ann Arbor, MI), which contained information for over 1,000 metabolites, following suspect screening described in recently published work (Axton et al., 2019; Garcia-Jaramillo et al., 2020).

About 7,300 and 11,200 chemical features were detected in positive ESI mode in eye and brain samples, respectively. In addition, 3,300 and 5,800 chemical features were detected in the negative ESI mode for the eye and brain samples, respectively. 96% of these features were filtered out based on lack of MS2 data or a good spectral match. The remaining annotated features from both the positive and negative ESI modes were then categorized according to the Schymanski levels of identification (Schymanski et al., 2014). Schymanski et al., 2014 defines four possible levels for feature identification confidence and describes the minimum data requirements for each. Annotated compounds were combined, and duplicates removed. Only compounds with a level 1 or 2 of confidence were used for pathway and multi-omics analyses, and only endogenous metabolites were considered. Following Schymanski et al., 2014, features with level 1 confidence are considered confirmed compounds and have MS, MS2 spectra and retention times (RT) matching a reference standard (in our case, the IROA spectral metabolites library). Features with level 2 confidence are considered probable structures and have matching MS and MS2 spectra, but no RT match. These features were accompanied by their peak intensity values for each sample.

The MetaboAnalyst v6.0 web interface (Xia et al., 2009) (Xia Lab, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec) was used to process the annotated feature peak intensities for each compound in .csv format. Initially the statistical analysis (one factor) module was used to generate the PCA plots, fold changes, and statistical significance values for the annotated features. The peak intensity table was directly uploaded to MetaboAnalyst v6.0 and the dataset was normalized using a log base 10 transformation and Pareto scaling. A Wilcoxon rank-sum test was performed using the built in false discover rate (FDR) method to determine which features were differentially abundant using a mutant vs WT comparison. Features with FDR p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Pathway analysis was performed using the pathway analysis module in the MetaboAnalyst v6.0 web interface. The peak intensity table was directly uploaded to MetaboAnalyst v6.0. Transformation and scaling applied above was repeated and the zebrafish KEGG pathway library was selected. Global test and relative-betweenness centrality were selected for enrichment method and topology analysis, respectively. Results with FDR p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Raw data and methods are publicly available under Metabolomics Workbench study ID ST003386. Annotated compound lists/peak intensities are available in the supplemental materials.

2.5. RNA sequencing

2.5.1. Eye and brain dissections

The five-adult zebrafish of each sex and genotype used in the dissection were also run through the behavior assays. For eye samples 1.5 mL screw cap Rhino tubes were prefilled with 900 mg of 0.5 mm zirconium oxide lysis beads. For brain sample 800 mg of 1 mm zirconium oxide lysis beads (ZROB10, Next Advance Inc., Troy, NY) were used. Both types of sample tubes were prefilled with 400 μL RNA lysis buffer (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA). Each zebrafish was euthanized by submersion in an ice bath for 3 min then weighed and measured. The entire brain was dissected and placed into the prepared Rhino tube and caps were closed tightly. Pairs of eyes were dissected immediately after the brain and homogenized using a Bullet Blender Storm Pro (Next Advance Inc., Troy, NY) at speed 6 for 2 min. An additional 300 μL of lysis buffer was added and briefly vortexed to mix. The 40 samples were stored at −80°C until further processing. Statistical analysis of weight and length between genotypes was performed using one-way ANOVA (p ≤ 0.05).

2.5.2. RNA extraction

RNA extraction was performed using the Zymo Quick-RNA Miniprep kit (R1054, Zymo Research, Irvine, CA). The extraction was performed according to the kit instructions with an in-column DNase 1 digestion step performed for 15 min. RNA quantity and quality measurements (RIN score >8) were taken using an Agilent 4150 TapeStation System (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA).

2.5.3. NGS sequencing

Samples were submitted to Oregon State University’s Center for Genome Research and Biocomputing (CGRB, Corvallis, OR) for library preparation and sequencing. Library prep was performed using the NEBNext UltraExpress RNA Library Prep Kit for Illumina with a Poly(A) mRNA isolation kit (NEB, Ipswich, MA). The 40 samples were loaded on an Illumina P3 flow cell (1.2 billion, 100 bp, paired end reads) (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA) and sequencing was performed using an Illumina NextSeq 2000 sequencer (Illumina Inc., San Diego, CA).

2.5.4. Read alignment

Following sequencing raw fastq files were shared with North Carolina State University’s Bioinformatics Research Center (BRC, Raleigh, NC) where they were processed for data analysis. The raw sequencing reads were quality trimmed and adapters were removed using fastp (v. 0.21.0) with the default settings (Chen et al., 2018). The average number of reads (x106) for the samples after trimming was 32.6, with the minimum read number being 24.1, and the maximum read number being 51.9. The reads were mapped to the GRCz11 primary assembly using the STAR aligner (v. 2.7.9a) (Dobin et al., 2013). The Lawson Lab published a zebrafish annotation (Lawson et al., 2020) and both the genome assembly file and the annotation gtf file (v. 4.3.2) were downloaded from their website (https://www.umassmed.edu/lawson-lab/reagents/zebrafish-transcriptome). The arguments used in the mapping step included –alignIntronMin 15, –alignIntronMax 250000 and –quantMode GeneCounts. The average percentage of uniquely mapped reads for the samples was 90.0%, with the minimum percentage being 85.4% and the maximum percentage being 94.3%. The gene count matrix included 36,351 genes for the 40 samples.

2.5.5. Wildtype and mutant sample validation

To investigate the penetrance of the CRISPR/Cas9 induced mutation we checked whether WT reads were expressed in WT samples and mutant reads were expressed in mutant samples using the following analysis. The differences in read mapping in the edited region of the Cyp1b1 gene between the WT and the mutant samples was examined using the samtools (v 1.13) mpileup tool. The number of bases that aligned to the CYP1B1 gene from 42,015,406 bp - 42,015,408 bp on Chromosome 13 was counted (Danecek et al., 2021). This corresponds to the location of the 389th aa. In the reference genome, the aa is a serine composed of “TCC”. In the mutant samples, it is expected that these three bp would correspond to an early stop codon. The input files for the samtools mpileup tool included the alignment bam file for each sample that was generated using the STAR aligner, the reference genome, and the region of interest. The resulting counts were in pileup format and only those bases that matched the reference on the forward strand or the reverse strand were included in the count. This meant that WT reads would be counted while mutant reads would not, thus mutant samples should all have counts equal to zero.

2.5.6. Differential gene expression analysis

DESeq2 (v. 1.32.0) was used to explore the overall clustering of the brain and eye samples (Love et al., 2014). The design formula for the DESeqDataSet object was design = ~ Sex + Group, where the groups included mutant brain, WT brain, mutant eye, and WT eye. Genes with a count < 10 across all samples were removed. The filtered gene matrix included 30,921 genes. The variance stabilizing transformation (blind = FALSE) was applied to the data and used for the generation of the PCA (including all filtered genes), MDS and heatmap plots. Sample10 (brain, wildtype, male) was an outlier in all three plots. In addition, Sample3 (brain, wildtype, female) appeared to be an outlier on the heatmap. From PCA and MDS plots generated separately for the brain and eye samples, it could be seen that both samples appeared to be outliers on the brain sample plots.

Further DEG analysis was performed using the NetworkAnalyst v3.0 web interface (Zhou et al., 2019) (Xia Lab, McGill University, Montreal, Quebec). The gene count matrix less the two outlier samples was directly uploaded to the web interface as a .csv file. Of the 36,351 features in the table 25,411 (69%) could be matched to gene-level (Entrez) expression. Low abundance features (counts < 4) and low variance features (variance percentile rank < 15) were removed, and the data was normalized using a log2(counts/million) transformation. DESeq2 was selected as the statistical method with mutant vs WT comparisons being made. Features with an adjusted p-value ≤ 0.05 and log2(fold change) ≥ |1| were considered DEGs. Figures such as ridgeline plots implemented all genes in the pathways not just DEGs using log2(FC) values. Data analysis and figures could then be viewed and saved using NetworkAnalyst v3.0. Raw and processed data and methods are publicly available under NCBI Geo accession #GSE272589. Gene count matrix/DEG tables are also available in the supplemental materials.

2.6. Multi-omics analysis

2.6.1. Data processing

The MetaboAnalyst v6.0 pathway analysis module was used to perform the multi-omics analysis. The joint pathway analysis tab was selected. Genes and metabolites that had p-values ≤ 0.05, as described in the above methods, were added to their respective categories along with their log2(FC) values. All pathways (integrated) was selected for the pathway database implementing both metabolic and transcriptomic KEGG pathways from metabolic and gene-only regulatory pathways. Hypergeometric test, degree centrality, and combine queries were selected for enrichment analysis, topology measure, and integration method, respectively. Data analysis and figures could then be viewed and saved using MetaboAnalyst v6.0. Results with FDR p-values ≤ 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Wh5 mutant zebrafish line

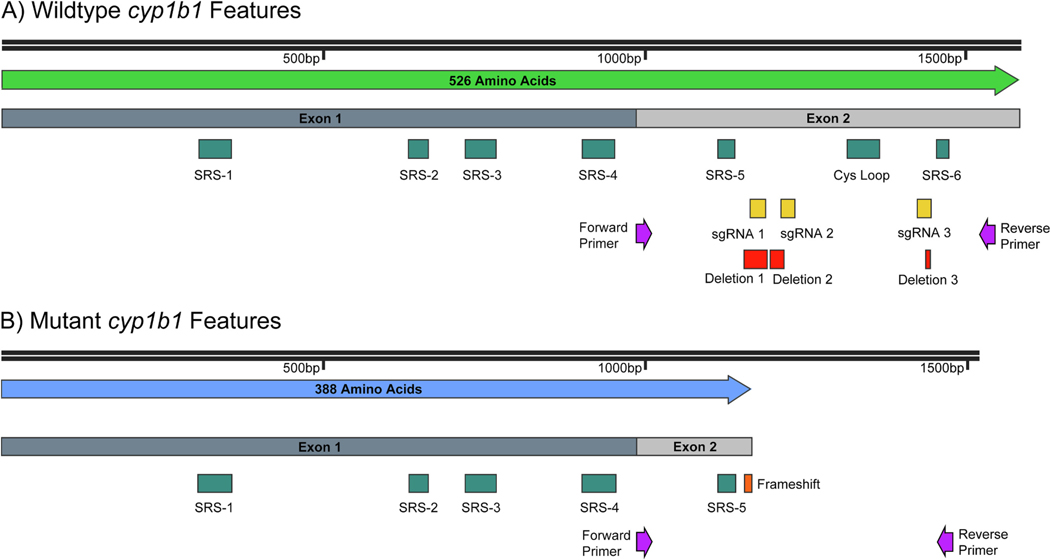

The CRISPR Cas9 procedure and founder selection generated a mutant line with three separate deletions in cyp1b1’s exon 2. Each deletion was produced near its respective sgRNA target sequence. Deletion one is 37 bp long, deletion 2 is 21 bp long, and deletion 3 is 8 bp long. Deletion 1 results in a frameshift mutation and an early stop codon in exon 2. This led to the loss of the Cys loop, cysteine ligand, and SRS-6 (Fig. 1). Without heme-binding functionality any translated mutant Cyp1b1 is rendered null.

Fig. 1.

A) Wildtype Cyp1b1 exon structure, substrate recognition sites (SRSs), and the cysteine ligand containing Cys loop are shown. Additionally, forward & reverse primer location, sgRNA target sites, and deletion positions against the WT coding sequence are shown. B) Mutant Cyp1b1 exon structure is shown. Additionally, forward & reverse primer location and frameshift mutation position proceeding the early stop codon against the mutant coding sequence are shown. The Cys loop containing the heme-binding cysteine ligand and SRS-6 are lost.

3.2. Larval phenotyping and behavioral assessments

3.2.1. Mutant larvae are hyperactive during portions of the LPR assay

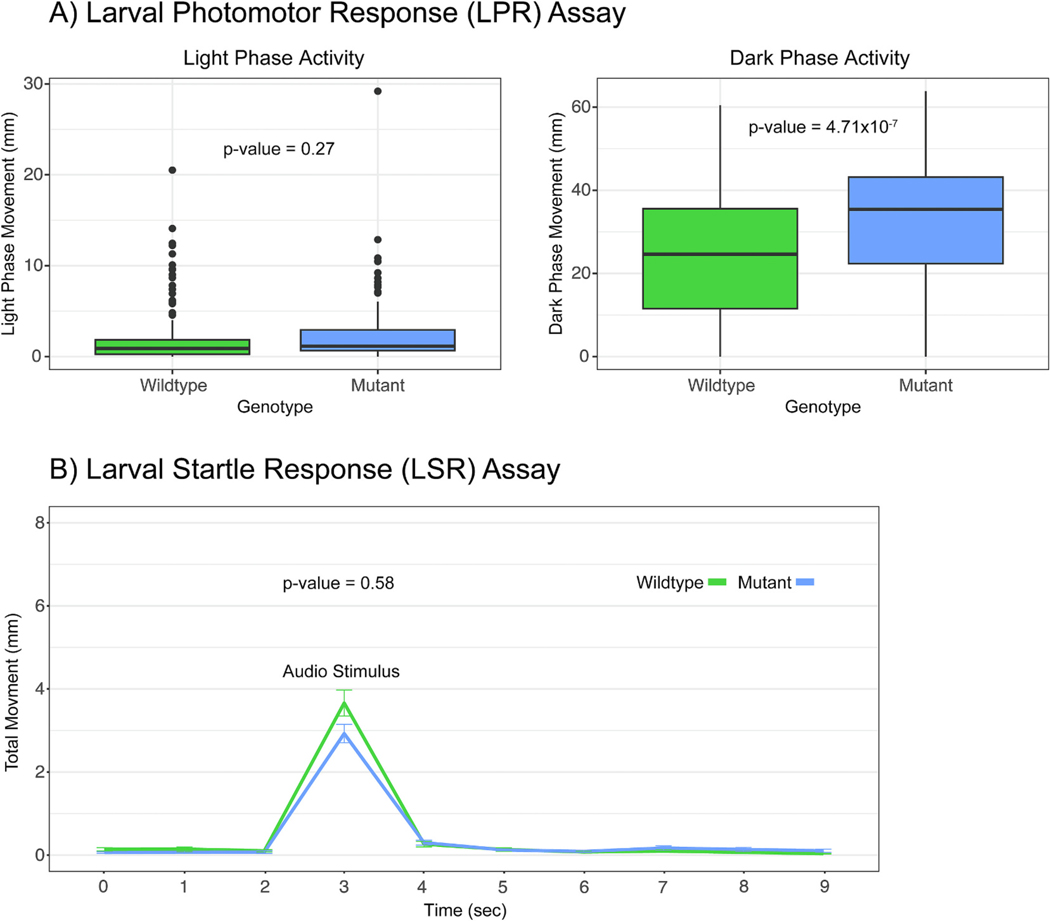

One of the goals of this study was to demonstrate that zebrafish lacking functional Cyp1b1 protein present an ocular defect, specifically a loss of visual acuity or altered response to visual stimulus. Behaviorally this phenotype was hypothesized to present as a loss of visual acuity and reduced reaction to visual stimuli. Compared to the WT control Cyp1b1 mutant larval zebrafish were hyperactive during the dark phase of the LPR assay. However, during the light phase of the assay Cyp1b1 mutants did not behave significantly different compared to the control (Fig. 2A). Although this altered response in the absence of light could be due to defects in larval photoreceptors this alone does not rule out neurobehavioral defects that could be at play.

Fig. 2.

A) Box plots of the larval photomotor response (LPR) assay. The movement in mm during the first light phase is shown in the left figure while movement in the first dark phase is shown in the right figure. CYP1B1 mutant 5dpf larvae did not behave differently during the light phase of the assay but were hyperactive during the dark portion of the assay. P-values = 0.27 and 4.71×10−7, n = 180, one-way ANOVA. The data within the interquartile range (IQR) was represented by the box, the whiskers represented data 1.5 times the IQR, and any data point beyond that appears as a dot. B) Larval startle response (LSR) assay plotted as time in sec vs total movement in mm. Zebrafish are subjected to an audio stimulus at 3 seconds and should move in response. Response is calculated as area under the curve for the entire period shown. CYP1B1 mutant 5dpf larvae did not behave significantly different during the LSR assay. P-value = 0.58, n = 180, one-way ANOVA.

To potentially rule out neurobehavioral effects the LSR assay is performed as it tests larval response to a non-visual audio stimulus. In this assay larval zebrafish did not behave significantly different compared to the control as measured by area under the curve (Fig. 2B). This points to early defects in phototransduction pathways affecting larval response to light/dark stimulus rather than a neurological cause. Further, larval zebrafish showed no gross morphological defects or additional mortality at 24 and 120hpf.

3.3. Adult behavior assessments

3.3.1. Mutant adults display differential behavior in the presence of zebrafish and a predator

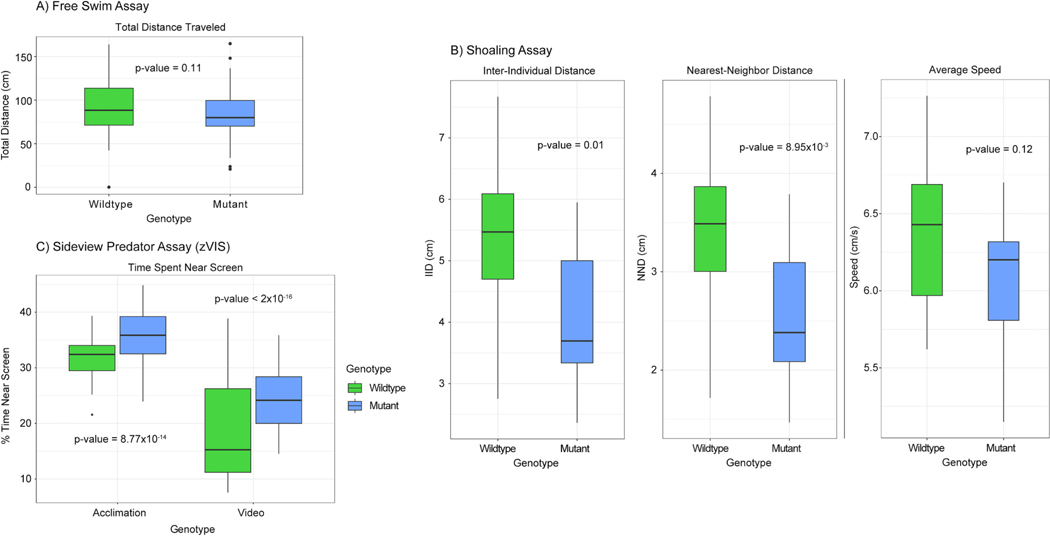

There was no statistically significant difference between the genotypes when measuring total distance traveled during the free swim assay (Fig. 3A). However, Cyp1b1 mutants displayed significantly lower IID and NND compared to the control meaning they remained closer to each other on average. The average speed of the genotypes was not significantly different which is consistent with the finding in the free swim assay (Fig. 3B). These finding suggest that the overall locomotion of the fish was unchanged by the loss of function mutation while changes in NND and IID suggests that mutant zebrafish have a visual or neurobehavioral phenotype linked to this mutation.

Fig. 3.

A) Box plot of the free swim assay. A single fish is placed in the tank and allowed to swim without interruption while its movement is tracked. The total distance swam is displayed on the y-axis and measured in cm. There was no significant difference between the genotypes when measuring total distance traveled. P-value = 0.11, n = 62 WT and 56 mutant, one-way ANOVA. For all the following box plots the data within the interquartile range (IQR) was represented by the box, the whiskers represented data 1.5 times the IQR, and any data point beyond that appears as a dot. B) Box plots of the shoaling assay. Four fish (two male and two female) are placed in the tank and allowed to swim without interruption while movement is tracked. Three metrics of behavior are tracked: inter-individual distance (IID-the average distance between all fish in cm), nearest-neighbor distance (NND-the average distance between the two nearest fish in cm), and average speed measured in cm/s. A significant difference in both IID and NND was observed between genotypes. No significant difference was observed when measuring average speed. P-value = 0.01, 8.95×10−3, and 0.12, n = 16 WT and 12 mutant, one-way ANOVA. C) Box plot of the sideview predator assay (zVIS). A single fish is placed in a tank near a computer screen. During the acclimation period no image is displayed on the screen, but during the video period a natural predator of the zebrafish is shown. The movement of the fish is tracked during both periods and percent time spent in the 1/3 of the tank nearest the screen is calculated as % time near screen. Mutant zebrafish performed differently during both the acclimation and the video portion of the assay spending more time closer to the screen when compared to the wildtype. P-value = 8.77×10−14 and < 2×10−16, n = 61 WT and 57 mutant, three-way ANOVA.

During the sideview predator assay both the WT control and the mutants moved away from the screen. However, the mutants only spent 31% less time in the portion of the tank close to the screen while the control spent 43% less time there. Further, the genotype’s behavioral differences were statistically significant in both the minute before and during the predator video (Fig. 3C). Although this suggests that mutant zebrafish have less of a response to the visual stimulus, altered behavior before the video plays is also contradictory to the hypothesis that behavioral differences are due to visual deficits only.

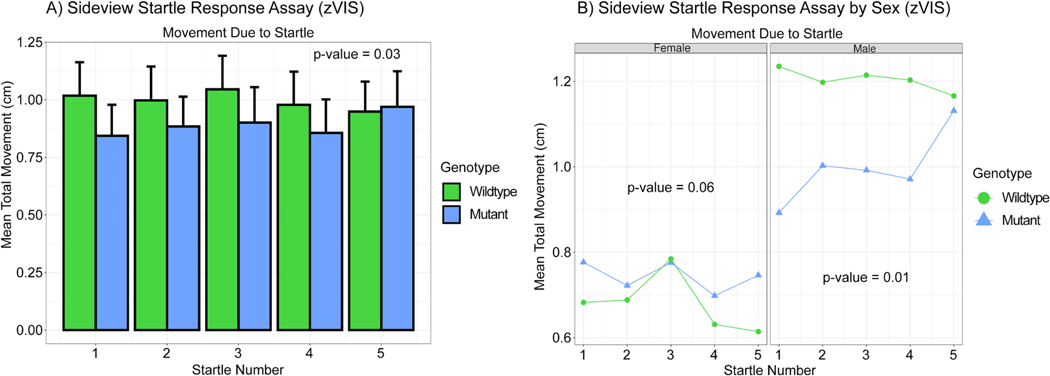

The results of the sideview startle response assay are also contradictory to this hypothesis. During the sideview startle response assay mutant adult zebrafish behaved statistically different compared to the wildtype control and did not move as much in response to the stimulus (Fig. 4A). When looking at males and females separately we found that males from each genotype responded significantly different while the females did not (Fig. 4B). Using a Tukey’s post hoc test it did not appear that either the control or the mutants habituated to the taps as no taps were significantly different from each other in a one-to-one comparison.

Fig. 4.

A) Bar graph of the sideview startle response assay (zVIS). This assay takes place following the sideview predator assay. A single fish’s movement in tracked during 10 consecutive mechanical vibrations every 20 s. Mean total movement during each of the taps is calculated and measured in cm. The first five taps are displayed. There was a significant difference between the genotypes when measuring mean total movement due to the startle (vibration). P-value = 0.03, n = 61 WT and 57 mutant, two-way ANOVA. B) Line graph of sideview startle response assay by sex (zVIS). There was a significant difference between the sexes when measuring mean total movement due to the startle (vibration). P-value = 1.82×10−5, n = 61 WT and 57 mutant, three-way ANOVA. When analyzed alone females did not exhibit statistically significant changes in behavior while males did. P-value = 0.06 and 0.01, two-way ANOVA.

A reason for this difference is potentially explained by changes in male neural development versus female zebrafish. The differences in startle response between female and male Cyp1b1 mutant zebrafish might be significantly influenced by estrogen’s involvement in eye and brain development, particularly since estrogen, like retinoic acid and arachidonic acid, is metabolized by Cyp1b1. Altered estrogen levels due to mutant Cyp1b1 could disrupt the metabolic balance of retinoic acid and arachidonic acid which are crucial for eye and brain development, potentially leading to altered developmental pathways affecting vision, neurobehavioral function, and hearing. A hormonal imbalance might explain why females exhibit consistent startle response between genotype compared to males. Such insights are pivotal for understanding the broad physiological roles of Cyp1b1, as disruptions in its activity due to genetic mutations can have cascading effects on both direct structural integrity of ocular and neural tissues and indirect hormonal regulation impacting behavioral phenotype. This complex interplay highlights the need to consider how alterations in hormone metabolism could influence developmental processes and behavior in a sex-specific manner. However, with the behavioral assays performed, we were unable to demonstrate that zebrafish lacking functional Cyp1b1 protein demonstrate behavioral deficits solely due to loss of visual acuity. Neurobehavioral deficits independent of vision could not be ruled out.

3.4. Adult zebrafish eye, brain, and body measurements

3.4.1. Differences in tissue mass occur in a sex-specific manner

Fish mass and length did not vary between genotype (p = 0.82 and 0.83 respectively, n = 60). Fish eyes also did not vary between genotypes with mean WT and mutant eye mass equal to 12.8mg and 12.2mg, respectively (p = 0.378, n = 40). However, when performing a Tukey post-hoc test there was a statistically significant difference in the mass of the eye between WT males and females (11.4mg vs 14.2mg, p = 0.008, n = 40), but not mutant males and females (11.6mg vs 12.8mg, p = 0.473, n = 40).

There was a statistically significant difference in the mass of the brain between the genotypes with mean WT and mutant brain mass equal to 6.8mg and 8.1mg, respectively (p = 1.71×10−3, n = 40). Further when adding an interaction variable between genotype and sex in a two-way ANOVA the effect was significant (p = 0.01, n = 40). When performing a Tukey post-hoc test the only significant pairwise comparison (other than male vs female) was between WT and mutant males (p = 4.22×10−4, n = 40). This demonstrates that males were driving the difference between genotypes with mean brain mass equal to 6.1mg and 8.4mg in the WT and mutant, respectively. In females mean brain mass was 7.5mg and 7.8mg in the WT and mutant. These finding support the observation that behavioral changes may be occurring in a sex-specific manner.

3.5. Metabolomics

3.5.1. Shared and tissue specific changes in metabolite abundance observed

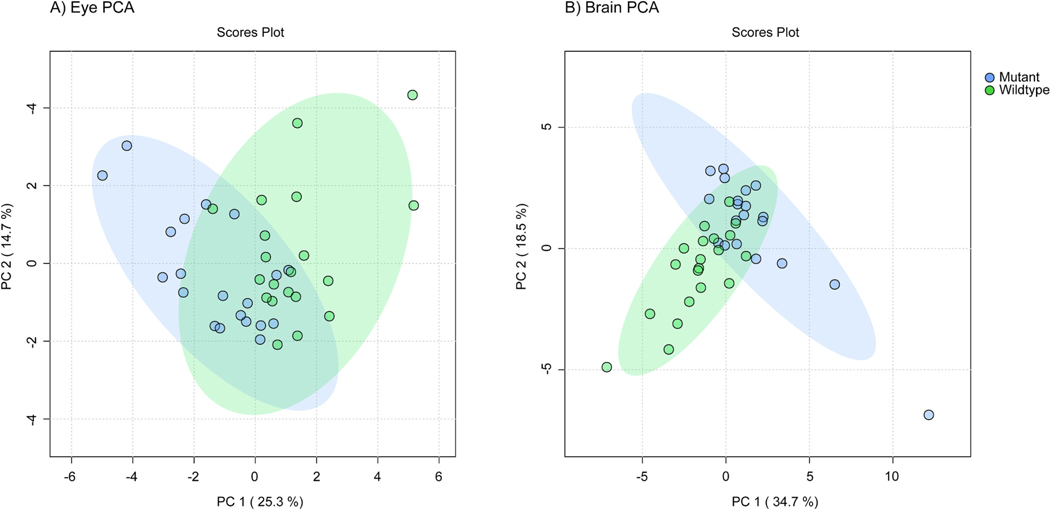

Principal component analysis (PCA) was performed on the metabolomics data from the eye and brain. Samples from either genotype clustered together but the 95% confidence interval ellipses overlapped with each other (Fig. 5).

Fig. 5.

Principal component analysis (PCA) plot based on untargeted metabolomics features from wildtype and mutant adult zebrafish A) eye and B) brain samples. 95% confidence interval ellipses represented by shading. There was modest separation between the WT and mutant samples.

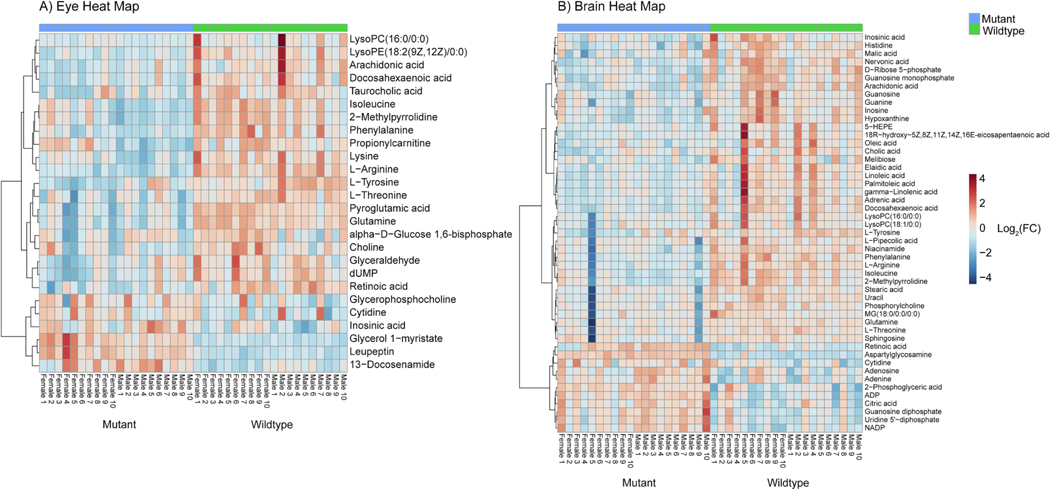

26 and 49 biologically relevant metabolites were found to be in differential abundance in the eye and the brain, respectively. 13 were shared between the organs while the remaining metabolites were unique to each organ. Heatmaps featuring metabolites in differential abundance in each organ were generated (Fig. 6).

Fig. 6.

Heat map of the features in differential abundance between wildtype and mutant adult zebrafish A) eye and B) brain samples (p-value < 0.05 FDR, n = 20, non-parametric t-test). Features ordered via hierarchal clustering using Ward’s method and the key displays log2(fold change). 26 and 49 biologically relevant metabolites were found to be in differential abundance in the eye and brain, respectively.

Of the 26 significant compounds in the eye 46 percent were annotated with a level 1 of confidence (MS, MS2 and RT match) and 54 percent were annotated with a level 2 of confidence (MS and MS2 but no RT match) according to Schymanski et al., 2014. The highest proportion of compounds in the eye were amino acids or related compounds making up 38 percent of the data. Second was fatty acid and lipid related compounds making up 19 percent of the data. This is followed by nucleic acid related compounds with 12 percent featuring one purine and two pyrimidines. The remainder of the data is made up of sugars, vitamins, and other miscellaneous metabolites.

Of the 49 significant compounds in the brain 69 percent were annotated with a level 1 of confidence (MS2 and RT match) and 31 percent were annotated with a level 2 of confidence (MS2 but no RT match) according to Schymanski et al., 2014. 38 percent of these compounds were fatty acid or lipid related compounds. 24 percent of the compounds were nucleic acid related compounds featuring ten purines and two pyrimidines. Finally, amino acids and related compounds made up 16 percent of the data with the remainder made up of sugars, vitamins, and other miscellaneous metabolites.

In the eye absence of Cyp1b1 leads to decreased levels of metabolites associated with amino acid (e.g., isoleucine, phenylalanine) and lipid metabolism (e.g., LysoPC, taurocholic acid), suggesting it helps degrade or modulate these compounds. Conversely, in mutant cells, the accumulation of metabolites linked to disrupted phospholipid and fatty acid metabolism (e.g., glycerophosphocholine, glycerol-1-myristate, 13-docosenamide) and nucleotide synthesis (e.g., cytidine, inosinic acid) further confirms its broad regulatory influence across these essential pathways.

In the brain, mutant Cyp1b1 was associated with elevated levels of metabolites critical for energy metabolism, including ADP, GDP, UDP, NADP, and citric acid, suggesting a compensatory response to disrupted metabolic regulation. These findings underscore the enzyme’s involvement in energy transfer, nucleotide synthesis, and the citric acid cycle.

In both organs arachidonic acid and retinoic acid appeared in the list of differentially abundant compounds pointing to the enzyme’s role in inflammatory response and cellular signaling regulation. Retinoic acid levels decreased in mutant eye cells but were elevated in mutant brain cells. The observed accumulation of retinoic acid in mutant brains suggests less effective compensatory responses, potentially due to differential regulation of enzymes involved in arachidonic acid metabolism, which could also impact inflammatory and vascular pathways. We speculate that distinct cytochrome P450 enzymes exhibit tissue-specific roles in retinoic acid metabolism, influencing compensatory mechanisms that are crucial for maintaining appropriate levels of this metabolite in each tissue. In the eye, enzymes such as Cyp26a1, Cyp26b1, Cyp26c1, and Cyp27c1 efficiently degrade retinoic acid, supporting essential visual functions and the visual cycle. Additionally, the metabolism of arachidonic acid by enzymes like Cyp2j20 and Cyp4v2, which also metabolize all-trans-retinol and all-trans-retinoic acid, influences retinoic acid pathways through their ω-hydroxylase activity on fatty acids. This activity is crucial not only for retinoid metabolism but also for the production of eicosanoids that may affect inflammation and vascular functions in ocular tissues (Pikuleva, 2023). Alternatively, brain may upregulate other retinoic acid-metabolizing enzymes, like CYP26B1, leading to retinoic acid accumulation, whereas the eye lacks such compensatory flexibility.

The combination of these enzymes’ activities underscores a sophisticated regulatory network that influences visual acuity, chromophore availability in photoreceptors, photosensitivity, and potentially inflammatory responses, through the metabolism of both retinoic acid and arachidonic acid. This highlights how visual information and ocular health are intricately processed under various lighting and physiological conditions, underscoring the importance of CYP-mediated metabolism in maintaining both ocular health and proper neurological functions. Further, tissue-specific enzymatic activity underscores why compensatory mechanisms might vary between the brain and eye, affecting retinoic acid homeostasis in distinct ways. This complex interplay, especially the pathological implications of CYP1B1 mutations and their effects on both retinoic acid and arachidonic acid pathways, continues to be crucial for understanding and potentially mitigating disorders like glaucoma.

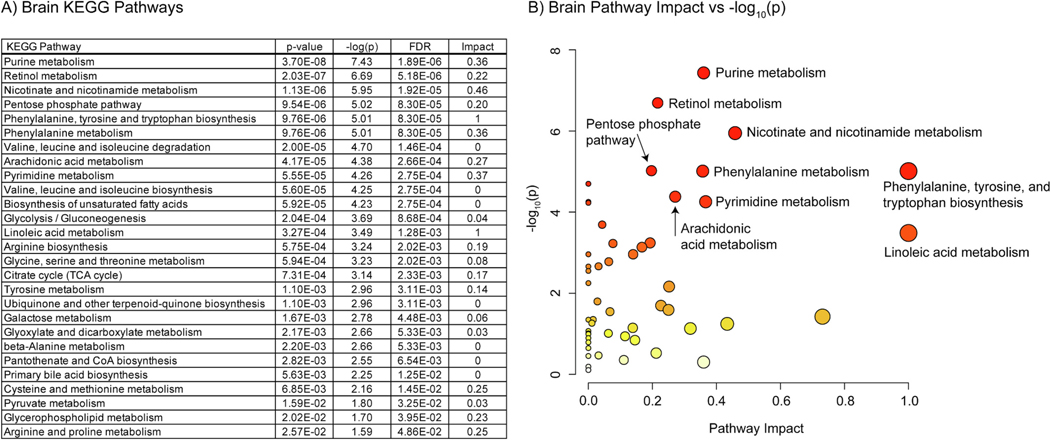

3.5.2. Metabolomics pathway analysis mirrors changes in metabolite abundance

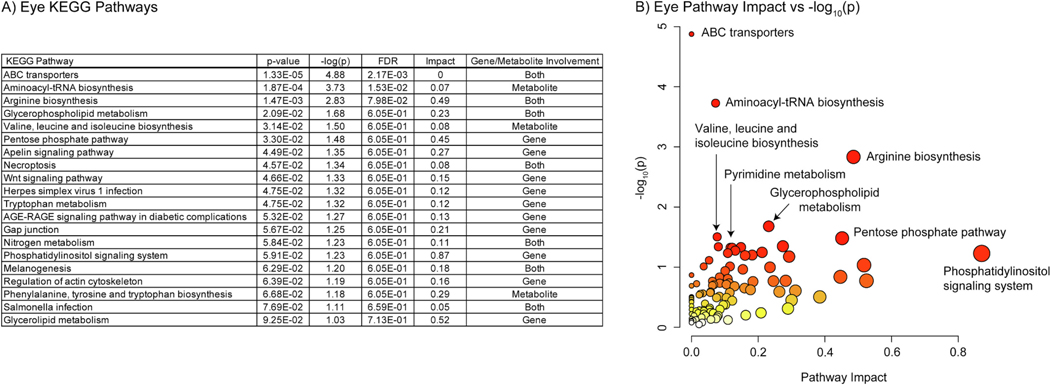

The pathway analysis tool in metaboanalyst was used to map the metabolite feature data to kegg pathways by directly uploading the peak intensity table to the web interface. Plots of pathway impact vs -log10(p) were generated accompanied by tables of the data (Fig. 7 and 8). Pathway impact is a measure of how many metabolites from the analysis appeared in a KEGG pathway. A higher number represents a larger number of metabolites represented in a pathway. -log10(p) is a transformation of the raw p-value to a non-decimal value where a larger number represents greater statistical significance.

Fig. 7.

A) Table of the 23 significantly perturbed KEGG pathways in the eye (p-value < 0.05 FDR, n=20, weighted z-test). B) Plot of KEGG pathway impact score vs pathway -log10(p). Pathway impact is represented by size (larger size = greater impact) while -log10(p) is represented by color (white = low and red = high).

Fig. 8.

A) Table of the 27 significantly perturbed KEGG pathways in the brain (p-value < 0.05 FDR, n=20, weighted z-test). B) Plot of KEGG pathway impact score vs pathway -log10(p). Pathway impact is represented by size (larger size = greater impact) while -log10(p) is represented by color (white = low and red = high).

In the eye 23 KEGG pathways were found to be enriched at 0.05 confidence level with an FDR method. These included multiple pathways responsible for amino acid metabolism and biosynthesis. In the eye lysine, arginine, glutamine, phenylalanine, tyrosine, threonine, and isoleucine were found to be in differential abundance. All had negative log2(FC) values. “Pyrimidine metabolism” and “Purine metabolism” were also altered. The differential metabolite analysis found one purine and two pyrimidines in differential abundance. Inosinic acid and cytidine had positive log2(FC) values while dUMP had a negative value. “Arachidonic acid metabolism” and “Retinol metabolism” were also present, driven by negative log2(FC) values of arachidonic acid and retinoic acid features. Many high confidence pathways with low pathway impact scores were driven by one or two metabolites. For example, “Biotin metabolism” was driven solely by lower lysine levels in the mutant. When compared to the brain several pathways with moderate pathway impact were unique to the eye. These included “Alanine, aspartate, and glutamate metabolism”, “Glutathione metabolism”, and “Glycerolipid metabolism”.

The same analysis in the brain found 27 KEGG pathways enriched at 0.05 confidence level with an FDR method. 16 of these pathways were shared with the eye data including most of the amino acid metabolism and biosynthesis pathways, “Purine metabolism” and “Pyrimidine metabolism”, Retinol metabolism”, and “Arachnoid acid metabolism”. Amino acids arginine, phenylalanine, isoleucine, histidine, tyrosine, threonine, and glutamine all had negative log2(FC) values. Only amino acid derivative aspartylglycosamine had a positive log2(FC) value equal to 2.94. All nucleic acid related compounds had negative log2(FC) values beside ADP and GDP. Arachidonic acid had a negative log2(FC) value like the eye data, however retinoic acid had a positive value of 1.35. Unique to the brain, pathways involved in “Linoleic acid metabolism”, “Pentose phosphate pathway”, “Nicotinate and nicotinamide metabolism”, and the “Citrate cycle (TCA cycle)” were enriched with moderate pathway impact.

The metabolomics pathway analysis further supports observations made from the metabolite analysis and heatmaps figures. Pathways related to amino acids (e.g., “Phenylalanine metabolism, “Valine, leucine, and isoleucine degradation”), nucleotide synthesis (e.g., “Purine metabolism”, “Pyrimidine metabolism”), and “Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids” were perturbed by the loss of Cyp1b1 in both organs. In the eye lipid metabolism related pathways (e.g., “Glycerolipid metabolism”, “Glycerophospholipid metabolism”) were affected. In the brain pathways related to energy metabolism (e.g., “Pentose phosphate pathway”, “Glycolysis/Gluconeogenesis”, “Citrate cycle (TCA cycle)”) were perturbed. These differences were driven by the significance of compounds and their direction of change between tissues. This is further highlighted by the differences in retinoic acid abundance between eyes and brain. While retinoic acid is in differential abundance in both tissues its log2(FC) value is negative in the eye and positive in the brain. Overall, these finding further support the observations made after reviewing the heat maps including potential conserved and tissue specific functions of Cyp1b1. Moreover, the pathway analysis tool helps frame observations from the untargeted metabolomics in context by placing observed compounds into a network with related metabolites.

3.6. RNA sequencing

3.6.1. Mutant samples express mutant cyp1b1 mRNA

We leveraged the RNA-seq data to characterize the penetrance of the CRISPR/Cas9 induced mutation. WT and mutant sample reads with “T” at 42,015,406 bp, “C” at 42,015,407 bp, and “C” at 42,015,408 bp were counted and alignments could be viewed using the Integrative Genomics Viewer (IGV) (Robinson et al., 2011). All WT samples except sample 10 had a count of at least one for each of the three positions, and no other variants were identified at these positions. Sample 10 did not have any reads that map to this location, although mapped reads do exist a few hundred bp up and downstream of this region. This is likely due to poor read coverage in this area. Sample 10 was one of the two samples that was removed as an outlier.

For mutant samples “TGA” stop codons were present in all samples at 42,015,406 – 42,015,408 bp. Only one of the mutant samples (sample 20) had bases that matched to the reference genome sequence of “TCC” at this location. Only one read contained the “TCC” codon while every other read included the “TGA” stop codon. This sample did not appear as an outlier in any of the analyses performed so it was not removed from the data set.

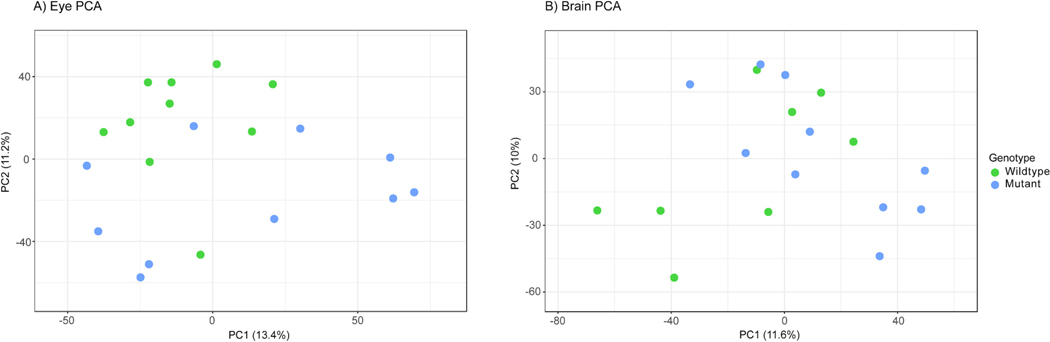

3.6.2. DEG analysis does not fully explain behavioral phenotypes

In addition to the metabolomics analysis characterizing differences in metabolic competency in adult zebrafish eyes and brains, RNA sequencing was performed on the same sample types correlating changes in metabolism to known gene pathways altered by the absence of Cyp1b1. The initial synthesis of this data was performed using a PCA of sequencing data from adult eye and brain samples. Replicates from either genotype appeared to group poorly (Fig. 9).

Fig. 9.

Principal component analysis (PCA) plot based on RNA sequencing of wildtype and mutant adult zebrafish A) eye and B) brain samples. There was little separation between the WT and mutant samples.

The analysis performed with NetworkAnalyst found 95 DEGs in the eye and 45 DEGs in the brain. Transcripts with adjusted p-values ≤ 0.05 and log2(FC) ≥ |1| were considered to be DEGs. When comparing the DEGs in each tissue only six (si:dkeyp-2e4.3, eys, si:ch73–106g13.1, LOC100536937, hcar1–3, and fancl) were present in both organs suggesting a context specific effect from null cyp1b1.

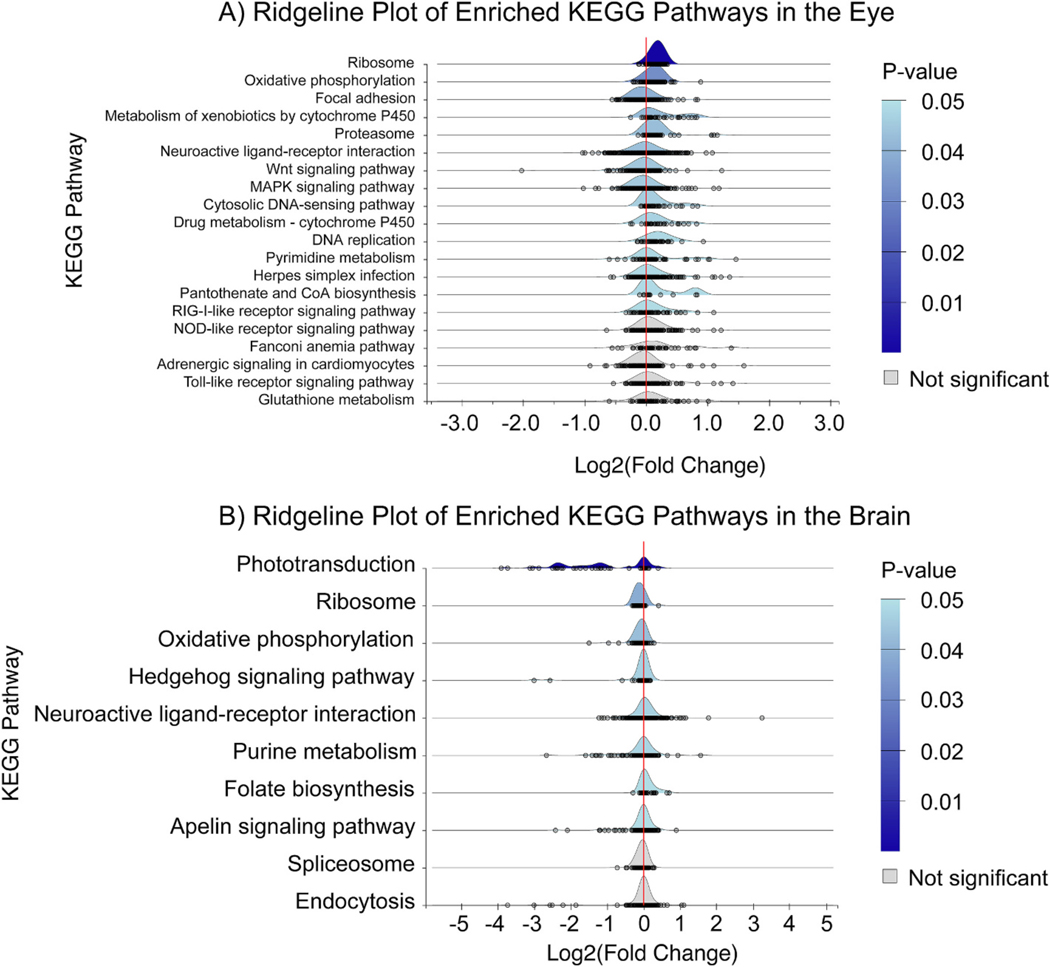

NetworkAnalyst was used to generate ridgeline plots of KEGG terms enriched using the built-in gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) for the eye and brain (Fig. 10). This analysis considered fold changes of all genes in the analysis not just those that were considered DEGs. The plots are ordered by raw p-value and represent the distribution of fold changes for genes present in each pathway in a mutant vs wildtype comparison. Individual genes are displayed at grey circles under each ridgeline.

Fig. 10.

A) KEGG pathways enriched using gene set enrichment analysis of mutant vs wildtype eyes (raw p-values with 0.05 cutoff, n=10, GSEA). Each point under the curve represents an individual gene and its fold change. There were 15 perturbed pathways when considering raw p-value, however only the top two were significant when considering adj. p-value. B) KEGG pathways enriched using a gene set enrichment analysis of mutant vs wildtype brains (raw p-values with 0.05 cutoff, n= 10 & 8 respectively, GSEA). Each point under the curve represents an individual gene and its fold change. There were eight perturbed pathways when considering raw p-value, however only the top three were significant when considering adj. p-value.

The eye had 15 perturbed pathways at a 0.05 confidence level using the raw p-value. However, when using adjusted p-value only two KEGG pathways were significant at a 0.05 confidence level: “Ribosome” (5.45×10−9) and “Oxidative phosphorylation” (7.93×10−3). The “Ribosome” KEGG term appears to be driven primarily by increased fold changes in ribosomal proteins that function in the mitochondria or the rest of the cell. The “Oxidative phosphorylation” KEGG term appears to be driven primarily by increased fold changes in ATP synthase subunits, NADH:ubiquinone oxidoreductase subunits, and cytochrome c oxidase subunits. The third highest enriched pathway, “Focal adhesion”, was not significant using adjusted p-value (0.07). According to KEGG for “Focal adhesion” (dre04510) term is defined by the interaction between transmembrane proteins and cytoskeletal elements. Some of these interactions facilitate structural links between these proteins while others control signaling pathways such as protein kinases and phosphatases. Further, signaling events initiated by these interactions are a prerequisite for changes in cell shape, motility, and gene expression. Further down the list of KEGG pathways are terms such as “Metabolism of xenobiotics by cytochrome P450” and “Drug metabolism – cytochrome P450” which are both shifted in the positive direction. The most abundant genes in these pathways are glutathione S-transferases. This may suggest that transcription of other phase I and II metabolizing enzymes increases in an attempt to compensate for the loss of Cyp1b1, perhaps as a result of the loss of metabolism of an endogenous AHR ligand.

The brain had 9 perturbed pathways at a 0.05 confidence level using the raw p-value. Using adjusted p-value three KEGG pathways were significant at a 0.05 confidence level: “Phototransduction” (7.86×10−18), “Ribosome” (4.21×10−3), and “Oxidative phosphorylation” (0.02). The “Phototransduction” pathway was driven by large fold changes of genes that are mostly known to be expressed in the eye, especially the retina. These including guanylate cyclase activators, g protein-coupled receptor kinases, and guanine nucleotide binding proteins. This is contrary to what might be expected in the brain samples but is explained when looking at gene counts in both tissues. In eye samples, high transcript counts are observed, ranging from thousands to tens of thousands per gene which are consistent across different replicates. In contrast, brain samples exhibited lower transcript counts, typically in the range of tens to hundreds per gene which varied widely across different replicates. The “Ribosome” KEGG term appears to be driven primarily by increased fold changes in ribosomal proteins that function in the mitochondria or the rest of the cell similar to what was seen in the eye. However, in the brain the overall fold changes of these genes are in the negative direction. This is also observed with the “Oxidative phosphorylation” KEGG term indicating a potential role for Cyp1b1 in the tissue-specific regulation of ribosomal components and oxidative phosphorylation events in the brain and eye.

Focusing on the hypothesis that nonfunctional Cyp1b1 results in a visual deficit the transcriptomic data may suggest that while lack of Cyp1b1 does disrupt normal transcriptional regulation it may primarily elicit its effect through metabolism which is the common belief for PCG and related eye disorders.

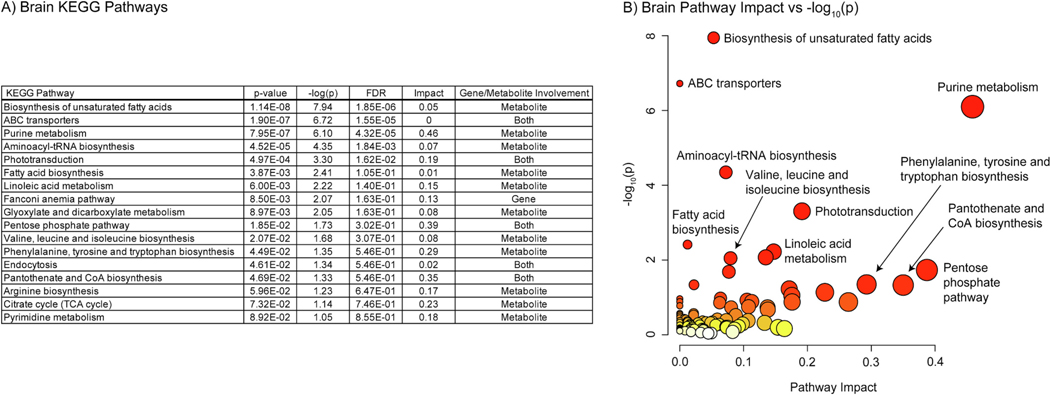

3.7. Multi-omics integration

3.7.1. Effectiveness of multi-omics analysis relies on presence of metabolites

The joint pathway analysis tool in MetaboAnalyst was used to map the metabolite feature data and gene expression data to KEGG pathways by uploading significantly perturbed genes and metabolites along with their respective log2(FC) values to the web interface. Like in the metabolomics pathway analysis plots of pathway impact vs -log10(p) were generated accompanied by tables of the same data (Figs. 11 and 12). The tables provided in the figures also describe whether there were genes, metabolites, or both represented in the respective pathway.

Fig. 11.

A) Table of KEGG pathways in the eye with raw p-value < 0.1 (n=20, weighted z-test). B) Plot of KEGG pathway impact score vs pathway -log10(p). Pathway impact is represented by size (larger size = greater impact) while -log10(p) is represented by color (white = low and red = high). There were 11 perturbed pathways when considering raw p-value, however only two were significant when using an FDR method.

Fig. 12.

A) Table of KEGG pathways in the brain with raw p-value < 0.1 (n=20, weighted z-test). B) Plot of KEGG pathway impact score vs pathway -log10(p). Pathway impact is represented by size (larger size = greater impact) while -log10(p) is represented by color (white = low and red = high). There were 14 perturbed pathways when considering raw p-value, however only five were significant when using an FDR method.

Only two pathways in the eye were significant using a 0.05 p-value threshold with an FDR method: “ABC transporters” (2.17×10−3) and “Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis” (0.02). The “ABC transporters” term was driven by negative log2(FC) values of multiple amino acids as well as abcb5. Adenosine and abca4b were present as well, but with positive log2(FC) values. “Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis” was solely driven by negative log2(FC) values of amino acids. No tRNA synthetases or tRNAs were present in the pathway. 9 additional pathways were significant when considering a 0.05 raw p-value cutoff and were mostly driven by genes only. Pathways in this category include three of those seen in the metabolomics pathway analysis: “Arginine biosynthesis”, “Glycerophospholipid metabolism”, and “Valine, leucine, and isoleucine biosynthesis”.

Five pathways in the brain were significant using a 0.05 p-value threshold with an FDR method: “Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids” (1.85×10−6), “ABC transporters” (1.55×10−5), “Purine metabolism” (4.32×10−5), “Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis” (1.84×10−3), and “Phototransduction” (0.016). “Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids” was driven solely by negative log2(FC) values of fatty acids present in the analysis. As in the eye the “ABC transporters” term was driven by negative log2(FC) values of multiple amino acids and a positive log2(FC) value for abcc1. “Purine metabolism” was driven by an impressive array of metabolites, however no gene interaction was present in the pathway. Again, “Aminoacyl-tRNA biosynthesis” was solely driven by negative log2(FC) values of amino acids and no tRNA synthetases or tRNAs were present in the pathway. “Phototransduction” was driven mostly by the same gene families that were seen in the RNA sequencing analysis in addition to a negative log2(FC) value for GMP. Nine additional pathways were significant when considering a 0.05 raw p-value cutoff and were mostly driven by metabolites only or metabolite gene interactions in contrast to the eye analysis. Pathways in this category include six of those seen in the metabolomics pathway analysis: “Linoleic acid metabolism”, “Pentose phosphate pathway”, “Valine, leucine and isoleucine biosynthesis”, “Phenylalanine, tyrosine and tryptophan biosynthesis”, “Pantothenate and CoA biosynthesis”, and “Glyoxylate and dicarboxylate metabolism”.

The joint pathway analysis in Cyp1b1 mutant zebrafish highlights the significant role of the “ABC transporter” pathway in maintaining cellular homeostasis by regulating the transport of molecules like amino acids across cell membranes, evident in both the eye and brain. This pathway’s modulation might be compensating for the metabolic imbalances caused by the absence of Cyp1b1, influencing key developmental and physiological processes that affect both visual and neurological functions. Additionally, the brain shows a notable importance in the “Biosynthesis of unsaturated fatty acids,” suggesting a critical role in maintaining brain health and possibly adapting to altered lipid profiles. In contrast, the eye demonstrates significant changes in “Glycerolipid metabolism” and “Glycerophospholipid metabolism,” crucial for membrane composition and signaling functions essential for visual processing. These pathway differences are pivotal in understanding the distinct metabolic responses that contribute to the organ-specific functionality and phenotypic alterations observed in the wh5 line.

The multi-omics analysis gave high confidence to KEGG pathways that included both metabolite and gene interaction in the pathway and analysis. However, for most pathways, confidence was lower compared to analysis of metabolites alone. This analysis used only metabolites and transcripts that were found to be significantly altered using adjusted p-value where the individual metabolomics and transcriptomics analysis implemented all features while considering fold change and p-value. Further, the analysis may favor metabolites over genes as the eye data included twice as many genes and half the number of metabolites compared the brain dataset. Ultimately, only two pathways were significantly enriched in the eye data where the brain data had five enriched pathways. Based on the data from the metabolomics and RNA sequencing we believe that phenotypic changes observed in the Cyp1b1 mutant line are largely driven by changes in Cyp1b1 metabolites potentially making this type of multiomics integration less effective.

3.7.2. Estrogen may play a protective roll via modulation of P450s

The interaction between estrogen and retinoic acid metabolism likely influences neurodevelopmental processes, driving the observed differences in eye and brain mass between male and female mutants. These observations suggest that broader hormonal and metabolic imbalances, particularly in males, may underlie both ocular and neurobehavioral defects in CYP1B1 mutants, consistent with the known sex-specific effects of estrogen metabolism and ocular health observed in human studies (Ogueta et al., 1999; Qureshi, 1995).

These findings are further corroborated by sex-specific behavioral differences observed during the sideview assay, particularly in male zebrafish, which may indicate dysregulation of estrogen metabolism. Estrogen, known to be metabolized by CYP1B1, plays a critical role in ocular health, with human studies showing that reductions in estrogen—such as those occurring post-menopause—are associated with an increased risk of primary open-angle glaucoma (POAG) (Fotesko et al., 2022; Nuzzi et al., 2018). Estrogen’s protective effects, including its regulation of intraocular pressure (IOP) and neuroprotection of retinal ganglion cells, may be diminished in the absence of CYP1B1, contributing to both ocular and neurodevelopmental phenotypes (Pasquale and Kang, 2011; Pasquale et al., 2013).

To further develop the hypothesis that dysregulation of estrogen metabolism is involved in the broader metabolic and behavioral changes observed in the mutant zebrafish we looked at cytochrome P450s that were present in the RNA-seq data set. We found that one CYP in the brain and six in the eye were significantly perturbed in these tissues. We also found that retinoic acid was less abundant in mutant vs WT eyes but more abundant in mutant vs WT brains.

In the brain, the observed accumulation of retinoic acid following Cyp1b1 knockout suggests insufficient catabolism of retinoic acid. The significant downregulation of Cyp2p10 (adj. p-value = 0.0109) and near-significant downregulation of Cyp3c3 (adj. p-value = 0.059) in the brain suggest that these enzymes play a compensatory catabolic role in regulating retinoic acid levels in the absence of Cyp1b1. The brain appears to rely on these pathways to degrade excess retinoic acid, and their downregulation may lead to an accumulation of retinoic acid that cannot be efficiently processed. This imbalance highlights the brain’s vulnerability to retinoic acid buildup, which could result in neurotoxicity. Without sufficient compensatory upregulation of other retinoic acid-catabolizing enzymes such as Cyp1a, the brain is left unable to properly manage retinoic acid homeostasis, which could disrupt neurodevelopmental processes.

In contrast, in the eye, a more anabolic response is observed, attempting to preserve retinoic acid levels through the compensatory upregulation of enzymes involved in retinoic acid synthesis following the loss of Cyp1b1. Cyp1a (adj. p-value = 0.035) and Cyp3c1 (adj. p-value = 0.012) are significantly upregulated in the eye, indicating an increased anabolic role in retinoic acid metabolism. These enzymes likely compensate for the loss of Cyp1b1 by supporting the synthesis of retinoic acid, which is crucial for ocular development and differentiation. However, despite these compensatory mechanisms, retinoic acid levels in the mutant zebrafish eye remain low, suggesting that the compensatory upregulation is insufficient to fully restore retinoic acid homeostasis. The reduced retinoic acid levels may contribute to the development of ocular diseases, as retinoic acid is critical for retinal development and function.

Additionally, the significant downregulation of Cyp2p6 (adj. p-value = 0.0097) and Cyp2ad2 (adj. p-value = 0.049) in the eye suggests a metabolic shift that might reflect decreased degradation of retinoic acid and estrogens. In humans, CYP2A family members like CYP2A6 are known to metabolize both retinoic acid and estrogens into less active forms. Therefore, their downregulation in the Cyp1b1 mutant zebrafish eye could be a compensatory response, allowing higher levels of retinoic acid and active estrogens to persist. While this does not appear to fully compensate for the loss of Cyp1b1, some compensation would benefit ocular health by supporting retinoic acid signaling, essential for retinal development, while maintaining higher levels of protective estrogens that may prevent conditions like glaucoma.

A particularly important finding in the eye is the significant downregulation of Cyp17a1 (adj. p-value = 0.0002), an enzyme involved in the anabolic synthesis of estrogens. Estrogen plays a protective role in ocular health, particularly in preventing glaucoma. The reduced expression of Cyp17a1 in the eye likely reflects a trade-off, where the tissue reduces estrogen biosynthesis to focus on retinoic acid metabolism. This metabolic shift could explain the more severe phenotype observed in male zebrafish, who have lower baseline estrogen levels and may be more susceptible to eye pathologies when estrogen synthesis is further compromised. In contrast, females, with higher baseline estrogen levels, may be better equipped to buffer against these changes.

The coordinated regulation of these CYP enzymes reveals distinct anabolic and catabolic processes that act as compensatory mechanisms in response to the loss of Cyp1b1 in the brain and eye. The brain’s failure to upregulate compensatory catabolic enzymes such as Cyp2p10 and Cyp3c3 leads to retinoic acid accumulation, reflecting a breakdown in retinoic acid degradation pathways. Meanwhile, the eye actively shifts toward anabolic processes, increasing retinoic acid synthesis via Cyp1a and Cyp3c1 while reducing estrogen production through Cyp17a1 downregulation. Despite these compensatory efforts, the low retinoic acid levels in the eye of Cyp1b1 mutant zebrafish could drive disease mechanisms and impair retinal development. These findings underscore the tissue-specific roles of P450 enzymes in retinoic acid and estrogen metabolism, offering new insights into the metabolic trade-offs that occur during ocular development and disease prevention, particularly in the context of Cyp1b1 mutations.

We further investigated the LCMS data using Sciex OS software (AB Sciex LLC, Framingham, MA) by looking for eight different estrogens that could be relevant for our hypothesis. Two were included in the IROA spectral metabolites library meaning that MS, MS2, and RT could be matched, and a level one of confidence could be gained for the peak annotation. The remaining metabolites could at most be annotated with a level two of confidence since there was no refence standard run through our instrument. Unfortunately, all eight of the estrogens investigated did not have discernable peaks above background or lacked MS2 data needed to annotate the peaks. In the future a more targeted analysis will be required to investigate the possibility of coupled changes in retinoic acid and estrogen abundance in the eye and brain.

The integration of multi-omics data with behavioral assays provides key insights into how these metabolic disruptions manifest at a functional level. Metabolomic and transcriptomic data suggest that disruptions in retinoic acid and estrogen metabolism affect both ocular function and neurodevelopmental pathways, consistent with the visual and neurobehavioral deficits observed in Cyp1b1 mutant zebrafish.

4. Conclusion