Highlights

-

•

Simultaneous quantification of glucagon and oxyntomodulin in plasma.

-

•

Distributable calibration materials were developed.

-

•

New antibodies are available for assay development in other laboratories.

-

•

P800 blood collection tubes maintained analyte stability better than EDTA tubes.

-

•

Type 1 diabetes patients on insulin pumps have lower plasma glucagon concentrations.

Keywords: Glucagon, Oxyntomodulin, Liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry, Diabetes, Antibody enrichment

Abstract

Introduction

Glucagon and oxyntomodulin are peptide hormones differentially released from proglucagon that function in regulating blood glucose. Their overlapping amino acid sequences make the development of specific immunoassays difficult, but the specificity of liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry can be used to distinguish the peptides. We aimed to develop a sensitive and specific mass spectrometric assay that uses non-proprietary reagents and normal-flow liquid chromatography in the simultaneous quantification of both analytes.

Methods

Bulk plasma proteins were precipitated in ethanol/ammonium hydroxide. Analytes were enriched using monoclonal antibodies generated in-house and analyzed using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. A glucagon calibration material was sourced commercially and characterized for purity and concentration by high-performance liquid chromatography-ultraviolet detection and amino acid analysis. Single-point calibration was used to minimize between-day variability.

Results

The novel antibodies performed acceptably (peptide recovery 45–59 %). The assay was precise (<13 %CV) and linear over the range of 1.3–14.7 pM and 1.1–13.7 pM for glucagon and oxyntomodulin, respectively. The glucagon calibration material concentration was determined to be 1.596 mg/g. Tube-type studies supported the use of protease inhibitor tubes at the time of blood draw. Patients with type 1 diabetes had lower concentrations of glucagon when maintained on an insulin pump, but not with injectable insulin.

Conclusion

We have validated a method with a highly detailed standard operating procedure. We have characterized calibration materials to help maintain accuracy and achieve between-day and between-laboratory harmonization. The assay will be beneficial in better understanding α-cell health and glycemic control in diabetes and other diseases.

1. Introduction

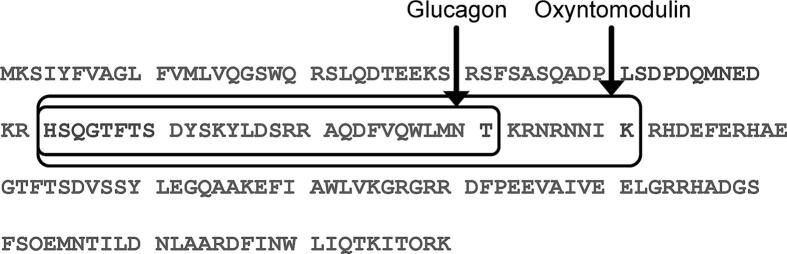

Glucagon and oxyntomodulin are bioactive peptides proteolytically derived from proglucagon, which is a 160 amino acid pro-hormone. It is differentially cleaved in the pancreas, intestines, and brain into a set of overlapping peptides that have different biological effects depending on their site of expression (Fig. 1) [1]. Along with insulin and many other counter regulatory hormones, glucagon and oxyntomodulin help maintain euglycemia [2], [3]. Glucagon has many effector cells throughout the body, but is also known to stimulate insulin secretion and regulate insulin degradation [4]. Oxyntomodulin, primarily secreted from the gut, also stimulates insulin secretion and can induce weight loss, presumably via glucagon and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptors [5], [6]. Sensitive and specific assays to quantify both glucagon and oxyntomodulin would be helpful in understanding α-cell health, in clinical studies of diabetes pathophysiology, and in the development of novel therapeutics [5], [6], [7].

Fig. 1.

Amino acid sequence of proglucagon. The sequences of glucagon and oxyntomodulin within the 160 amino acid proglucagon prohormone are highlighted by rectangles.

There have been many immunoassays developed for glucagon and several for oxyntomodulin, the majority of which are, or have been, distributed commercially [8], [9], [10]. Importantly, due to the overlapping sequences that these peptide hormones have with one another, as well as with other peptide hormones in blood, there can be significant issues with cross-reactivity [8], [11], [12], which can result in misleading conclusions in clinical research, particularly in physiologic states when related hormones are present at altered concentrations [11], [13], [14], [15]. Although not always as sensitive, liquid chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry (LC-MS) or tandem mass spectrometry (LC-MS/MS) can significantly improve the specificity of hormone analyses [16]. As a result, there have been several mass spectrometric (MS) assays developed to meet the needs of investigators for analyte specificity [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22], [23]. These assays have certain shortcomings that limit their widespread application to large clinical research studies. For example, to achieve the required sensitivity, several rely on nanoflow (<1 μL/min) or microflow (1–50 μL/min) liquid chromatography, which limits throughput and/or robustness. Others lack the sensitivity required for clinical studies involving human plasma (i.e., sensitive to 1–2 pM) [17], require large sample volumes that are difficult to acquire from mice or large clinical studies, [17], [18], [20], [22] or do not include oxyntomodulin in the analysis [21], [18], [19]. One of the most promising assays described so far uses an antibody to enrich glucagon and oxyntomodulin from plasma, but requires a larger sample volume (400 μL) and needs microflow chromatography for sufficient sensitivity [20]. Further, the antibody used in the assay is proprietary and in limited supply.

In this study, we aimed to develop a novel assay for both analytes with sufficient sensitivity for clinical research and clinical care [i.e., target lower limit of the measuring interval (LLMI) of 1–2 pM]. The new assay uses 200 μL of plasma, publicly available (non-commercial) antibodies, and other reagents and supplies that are available in many high-complexity clinical laboratories (e.g., normal-flow chromatography and a triple quadrupole mass spectrometer). To achieve the required sensitivity, we combined two steps of matrix simplification based on prior work: protein precipitation and immunoaffinity enrichment [20], [21], [22]. The resulting assay had sufficient sensitivity, linearity, and precision to be used in research studies in clinical cohorts. We generated a well-characterized glucagon calibration material to ensure accuracy. In addition, our publicly available monoclonal antibodies and a detailed standard operating procedure should allow other laboratories to adopt the assay for their own use. The well-characterized calibration material could also be used in other assays to evaluate metrological traceability [24]. Our pilot study in type 1 diabetic patients demonstrated the utility of the assay to evaluate α-cell health in clinical studies.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Standard operating procedure (SOP)

A detailed SOP is presented in the Supplemental Material, which includes lists of equipment, chemicals, and supplies and descriptions of quality control materials, system suitability material, and LC-MS/MS settings. A brief description of the method is provided here.

2.2. Reagents

Glucagon was purchased from Anaspec (Fremont, CA, Cat. No. AS-22457) and oxyntomodulin from Phoenix Pharmaceuticals (Burlingame, CA, Cat. No. 028–22), each of which was dissolved in dimethylsufloxide (DMSO) to 2 mg/mL and stored in aliquots at –80 °C. Stable isotope-labeled glucagon and oxyntomodulin internal standards (IS) were purchased from New England Peptide (Gardner, MA, Cat. No. BP22-092 and BP22-094, respectively). Glucagon IS was 13C-labeled at two phenylalanine (F^) residues (HSQGTF^TSDYSKYLDSRRAQDF^VQWLMNT) and oxyntomodulin IS was 13C- and 15N-labeled at one lysine (K^) and one arginine (R^) residue (HSQGTFTSDYSK^YLDSRRAQDFVQWLMNTKR^NRNNIA). An LC-MS/MS quality control peptide from thyroglobulin was 13C-labeled at one leucine (L^) residue (FSPDDSAGASALL^R, abbreviated FSP) and was purchased from Anaspec. A protease inhibitor mixture (DPP4-Plus) was generated by combining DPP-4 inhibitor (DPP4-010, Millipore Sigma, MO) and a protease inhibitor cocktail (P2714, Millipore Sigma) and added to plasma (10 μL DPP4-Plus per 1 mL of plasma).

2.3. Human samples.

De-identified leftover clinical plasma samples were obtained from the clinical laboratories at the University of Washington Medical Center, which was reviewed by the Human Subjects Division of the University of Washington and determined to be non-human subjects research (STUDY000011691). Plasma samples were also obtained from participants (after giving informed consent) via the University of Washington Nutrition Obesity Research Center (N = 29). Institutional Review Board (IRB)/ Ethics Committee approval for the collection and use of specimens was obtained from the Human Subjects Division of the University of Washington (STUDY00011972). No participants were on glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists, DPP-4 inhibitors, or amylin/IAPP mimics.

2.4. Antibodies

Monoclonal antibodies to glucagon and oxyntomodulin were developed in collaboration with the Fred Hutchinson Antibody Technology Core. Mice were immunized to peptides HSQGTFTSDYSK, SKYLDSRRAQDFVQWLMNT, and AQDFVQWLMNT. The two hybridoma cell line clones selected and used in this assay (4B1g and 26Hf) have been deposited in the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank at the University of Iowa for research use.

2.5. Characterization of glucagon calibration material.

Amino acid analysis of the glucagon calibration material was performed using a modification of a protocol from the National Institute of Standards and Technology [25], [26], which quantified four stable amino acids liberated during the hydrolysis reaction (i.e., alanine, valine, leucine, phenylalanine) at 130 °C for 46 h under acidic conditions (8 N HCl). Calibration was achieved using certified amino acid reference materials (Sigma, MA, USA) and amino acids were quantified using LC-MS/MS on a Xevo TQ-S mass spectrometer equipped with an I-Class UHPLC system (Waters, MA, USA) and a PrimeSep 100 mixed-mode column (2.1x250 mm, 3 µm, 100 Å, SIELC Technologies, IL, USA) developed with a water-acetonitrile gradient containing trifluoroacetic acid (see details in Supplemental Material) and TargetLynx software. Mass confirmation of the glucagon calibration material was achieved using LC-MS on the same analytical platform operating in full scan mode with an Acquity UPLC HSS T3 analytical column (186003538, Waters) developed with a water-methanol gradient containing 0.2 % formic acid at 0.3 mL per minute (gradient and MS conditions are in Supplemental Tables 1 and 2). Using the same chromatographic column and gradient, the purity of the glucagon calibration material was determined by HPLC and ultra-violet spectroscopy (280 nm) with a Prominence HPLC equipped with a Nexera SPD-40 UV–Vis detector and Lab Solutions software (Shimadzu, Kyoto, Japan). Glucagon in DMSO was diluted with water to 0.5 mg/mL prior to injection (10 μL).

2.6. Sample preparation.

Plasma samples were prepared by protein precipitation and immunoaffinity enrichment (Supplemental Fig. 1). While on ice, an aliquot of 200 μL plasma was supplemented with 10 μL IS and alkalinized with 100 μL 5 % ammonium hydroxide. Proteins were precipitated with 900 μL ethanol and incubated at –20 °C before centrifugation. The supernatant (1 mL) was then evaporated in a vacuum concentrator for at least 10 h until fully dried. Pellets were reconstituted with 100 μL 90 mM ammonium bicarbonate/10 % acetonitrile/water and then incubated for 45 min with 400 μL phosphate buffered saline (PBS, 138 mM sodium chloride, 10 mM sodium phosphate, 2.7 mM potassium chloride)-0.1 % CHAPS and antibody-conjugated beads. Using a side magnet, beads were washed four times with 200 μL PBS-0.1 % CHAPS and then peptides eluted with 50 μL of an acidified organic solvent containing 20 % DMSO. Isotope-labeled thyroglobulin FSP peptide was added prior to injection onto the LC-MS/MS for system suitability quality assurance.

2.7. LC-MS/MS analysis

Eluates were analyzed using a Xevo TQS equipped with an Acquity UPLC system, an HSS T3 VanGuard Pre-column (2.1 × 5 mm, 1.8 μm), and an HSS T3 C18 analytical column (2.1 x 50 mm, 1.8 μm), which was developed over 8.5 min using a 10 to 95 % water-methanol gradient containing 2 % DMSO and 0.1 % formic acid. For glucagon (average mass of unlabeled peptide: 3482.8 Da; labeled peptide: 3500.7 Da), the transitions MH4+4 b25+3, b26+3, and b27+3 were monitored and for oxyntomodulin (average mass of unlabeled peptide: 4449.9 Da; labeled peptide: 4467.8 Da), MH7+7 y11+2 with two 0.01 m/z offset echo transitions. Specific m/z are listed in Supplemental Materials. Representative chromatograms at the LLMI are presented in Supplemental Fig. 1. Isotope-labeled FSP was monitored as a system suitability control to help ensure and troubleshoot instrument performance of the LC-MS/MS system (i.e., any peptide with known characteristics could be used to evaluate retention time and peak shape).

2.8. Calibrators and quality control materials

Leftover de-identified K2-EDTA-anticoagulated human plasma (>72 h at room temperature) was analyzed for residual glucagon and oxyntomodulin and served as a null matrix once confirmed negative. In some cases, three cycles of freezing and thawing were used to eliminate remaining glucagon and oxyntomodulin, which are unstable to freeze-thaws in EDTA-anticoagulated plasma. Calibrators and quality control materials were generated by supplementing null matrix with DPP4-Plus and adding glucagon and oxyntomodulin. To compare multiple- vs. single-point calibration, calibrators were prepared by volumetrically spiking leftover de-identified K2-EDTA-anticoagulated human plasma to 0, 1, 2.5, 5 and 15 pM of glucagon and oxyntomodulin and stored at −80 °C until use. Quality control materials and calibrators were then analyzed in triplicate on each of three days. Analyte concentrations in the quality control materials were calculated from observed peak area ratios by using a linear regression calibration function across the five calibrators or the 15 pM calibrator as a single-point calibrator.

2.9. Data reduction

Chromatographic peaks were integrated using Skyline Daily [27], [28]. Validation data have been deposited in PanoramaWeb (https://panoramaweb.org/TaMADOR_Glucagon.url) [29]. Peak areas for selected MRMs were exported from Skyline and then summed and analyzed in Excel. Peak area ratios were calculated by dividing the unlabeled peak area by the isotope-labeled peak area. This was done for each analyte in each sample, quality control material, and single point calibrator. The concentration of each analyte in the samples and quality control materials was determined by dividing the observed peak area ratio by the mean peak area ratio of the three single point calibrator replicates in each batch and multiplying by the analyte concentration in the single point calibrator.

2.10. Validation

The performance characteristics determined during method validation included imprecision, LLMI, linearity, and stability (see details in Supplemental Materials).

3. Results

3.1. Method development

We aimed to develop a workflow that could be easily adopted by other laboratories for the simultaneous quantification of glucagon and oxyntomodulin in plasma samples, which could help to characterize islet α-cell health and the contribution of gut-derived hormones on glucose regulation during the development, progression, and treatment of diabetes. Due to the overlapping sequences of the two analytes (Fig. 1), we quantified their intact forms, rather than proteotypic peptides after proteolysis. We attempted to replicate previous approaches that used protein precipitation and solid-phase extraction or immunoaffinity precipitation by themselves, but were unable to achieve the sensitivity needed for acceptable limits of detection using a low sample volume (≤200 μL of plasma), normal-flow liquid chromatography (>50 μL/min), and triple quadrupole tandem mass spectrometry (i.e., a reasonable sample volume to expect from murine or large clinical research studies and the most common instrument configuration in clinical laboratories). Our efforts in using commercially available antibodies to enrich analytes were also unsuccessful (data not shown). The final method combined protein precipitation, immunoaffinity peptide enrichment with in-house antibodies, and LC-MS/MS (Supplemental Fig. 2). In order to facilitate transfer to other laboratories, we developed a detailed SOP (Supplemental Material). We found that the addition of 10% DMSO to a previously described elution solvent [20] increased the recovery of glucagon and oxyntomodulin 3- and 2-fold, respectively (data not shown). To compare multiple- and single-point calibration, we compared the variability observed when calculating the concentrations of quality control materials in triplicate on each of three days using either a 5-point calibration curve or the top calibrator as a single-point calibrator. The observed variability was lower for the single-point calibration approach (Table 1), which was consistent with previous studies [30], [31], [32], [33], [34] and led to our decision to use spiked pooled leftover analyte-negative human plasma with added DPP4-Plus as a single-point calibrator for the assay.

Table 1.

Comparison of multiple-point and single-point calibration.a

| Glucagon |

Oxyntomodulin |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | Concentration (pM) | Multiple calibrators (%CV) | Single-point (%CV) | Concentration (pM) | Multiple calibrators (%CV) | Single-point (%CV) |

| Low | 3.1 | 29.4 % | 14.8 % | 0.5 | 189.2 % | 27.1 % |

| Medium | 11.4 | 6.8 % | 6.6 % | 9.2 | 7.3 % | 7.2 % |

| High | 21.8 | 6.5 % | 7.7 % | 20.2 | 5.1 % | 5.1 % |

Three quality control materials were analyzed in triplicate along with five calibrators analyzed in triplicate on each of three days. Concentrations of analytes in the quality control materials were calculated using either the calibration curve (i.e., linear regression) or the single-point calibrator (calculated as the peak area ratio of the quality control material divided by the peak area ratio of the single-point calibrator multiplied by the concentration of the single-point calibrator). Imprecision was calculated from the sum-of-squares using the average within-day %CV and average between-day %CV.

3.2. Comparison with previously described monoclonal antibody

To achieve sufficient sensitivity in lower volume samples, we developed new murine monoclonal antibodies directed toward glucagon and oxyntomodulin. In order to evaluate the quality of the novel antibodies, a combination of 5 µg of monoclonal antibody 4B1g and 5 μg of monoclonal antibody 2H6f was used to purify internal standard that had been spiked into a pooled human plasma matrix, which was subsequently protein precipitated with ethanol in an alkaline environment. The recovered peptides were compared to an appropriate amount of pure internal standard peptides to calculate percent recovery. The combination of antibodies recovered 59 % and 45 % of the spiked glucagon and oxyntomodulin, respectively, compared with 40 % and 20 % using 10 μg of a previously described monoclonal antibody [20], indicating that the new antibodies in combination perform at least as well as the other antibody in the assay (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Monoclonal antibody comparison. Isotope-labeled internal standard glucagon and oxyntomodulin internal standards were added to protease-inhibited analyte-negative plasma. On different days, samples were processed using protein precipitation and immunoaffinity enrichment with either comparator monoclonal antibody (mAb) or both of the new University of Washington (UW) mAb (4B1g and 2H6f). The chromatographic peak areas of the enriched internal standards were compared with pure isotope-labeled proteins to calculate recoveries (N = 12 for comparator mAb and N = 9 for UW mAb).

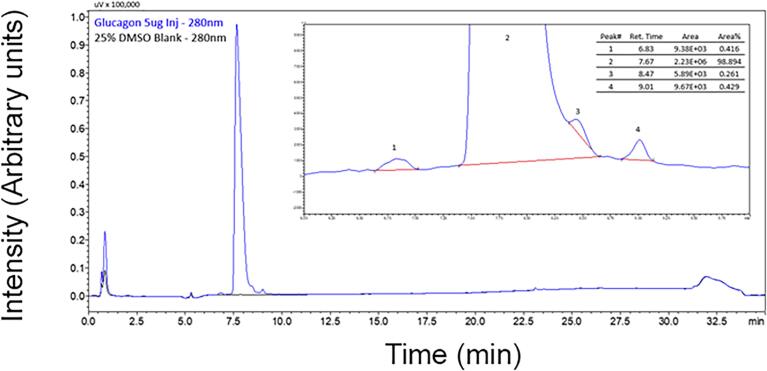

3.3. Characterization of a glucagon calibration material

Due to the lack of concordance between available glucagon immunoassays, we aimed to generate a well-characterized pure calibration material to help achieve accuracy within our own laboratory and to enable other laboratories to achieve metrological traceability to the International System of Units (SI units). Synthetic glucagon was procured from a commercial vendor and separated into aliquots. Purity of the glucagon calibration material was determined to be 98.894 % using HPLC-UV (Fig. 3). The average mass was confirmed by reversed-phase.

Fig. 3.

Purity assessment. Absorbance traces from the HPLC-UV analysis (280 nm) of equal volumes of the glucagon calibration material (blue) and the DMSO blank matrix (black) are illustrated. (Inset) Peak areas were determined by using manually assigned baselines (red). (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

LC-MS (precursor scan) to be 3,483 Da ([M + 3H]3+ = 1162 m/z). The concentration of the glucagon calibration material was determined by amino acid analysis using a reference method adapted from the National Institute of Standards and Technology [25], [26], [33]. After acid hydrolysis, four stable amino acids (i.e., alanine, valine, leucine, and phenylalanine) were quantified in five aliquots in triplicate, in five different assays, over four days (Fig. 4 and Supplemental Table 3). The concentration assigned was 1.596 mg/g and was not adjusted to account for the slight impurities observed by HPLC-UV. Aliquots of this material were used to produce secondary single-point calibrators and quality control materials.

Fig. 4.

Amino acid analysis. Five aliquots of the glucagon calibration material were analyzed in triplicate in each of five batches over four days. Mean concentrations ± SD (N = 15) are illustrated for each amino acid (alanine, Ala; valine, Val; leucine, Leu; phenylalanine, Phe). Solid line represents the overall mean of the measured concentration across the four amino acids across all five batches and dotted lines represent ± 2 SD (N = 60).

3.4. Method validation

Imprecision of the assay was estimated by analyzing five replicates on each of five days of each of two different spiked pooled analyte-negative EDTA-anticoagulated plasma samples supplemented with DPP4-Plus (i.e., blank matrix). One sample emulated analyte concentrations in healthy fasting individuals (3.5 pM) and the other post-prandial (11.5 pM). Based on the sum of squares [35], the total variability was estimated to be ≤11 %CV for both analytes at both concentrations (Table 2). These estimates were supported by the observed variability over 61 batches (9.6–13.0 %CV and 9.5–11.3 %CV for glucagon and oxyntomodulin, respectively).

Table 2.

Assay imprecision.a

| Glucagon |

Oxyntomodulin |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [pM] b | CVTotalc | [pM] b | CVTotalc | ||

| Pre-validation | Low Pool | 3.63 | 11.0 % | 3.59 | 10.9 % |

| High Pool | 11.81 | 7.5 % | 11.81 | 6.4 % | |

| Validation | Low Pool | 3.59 | 13.0 % | 3.48 | 11.3 % |

| High Pool | 11.66 | 9.6 % | 11.50 | 9.5 % | |

During pre-validation, two plasma samples, each spiked with glucagon and oxytomodulin, were analyzed in quintuplicate on each of five days. During and after validation, the same two spiked plasma samples were analyzed in duplicate on each of 61 days.

The mean concentration observed for each sample is listed (N = 25 for pre-validation and N = 122 for validation).

Using the sum of squares, total imprecision (CVTotal) was estimated for each sample in the pre-validation experiment by using the mean between-day and mean within-day variability: CVTotal = (CVB2 + CVW2)0.5. The imprecision calculated during and subsequent to validation used all 122 measurements.

The LLMI was determined by analyzing a series of spiked blank matrix samples (0.5 to 5 pM glucagon and oxyntomodulin). Samples were tested in triplicate on each of three separate days and the LLMI was estimated by interpolating the concentration at which the imprecision was equal to 20 %CV using a power function (0.9 and 0.7 pM for glucagon and oxyntomodulin, respectively; Fig. 5A,C). Based on the observed concentrations and imprecision, the lowest concentrations that met predefined criteria (recovery between 80–120 % and imprecision < 20 %CV) were 1.1 pM and 1.0 pM for glucagon and oxyntomodulin, respectively (Fig. 5B,D and Supplemental Table 4).

Fig. 5.

Determination of the LLMI. Protease-inhibited analyte-negative pooled plasma was spiked gravimetrically with six concentrations of analytes. Aliquots were frozen and tested in triplicate on three separate days to determine imprecision and bias. The imprecision observed at each concentration is illustrated for (A) glucagon and (C) oxyntomodulin and the best fit line was determined using a power function (dotted line). Measured concentrations were compared with expected concentrations for (B) glucagon and (D) oxyntomodulin, with the line of identity illustrated as a dotted line. Error bars are SD (N = 9).

Linearity was confirmed across the range of 1.3 to 14.7 pM for glucagon and 1.1 to 13.7 pM for oxyntomodulin by analyzing two dilutional series prepared at ratios of 3:1, 1:1, and 1:3 for each series. The series were generated by mixing either a human plasma pool or a spiked human plasma pool (i.e., a different pool of human plasma) with negative matrix and each sample was analyzed in triplicate, one series per day (Fig. 6). All admixtures met predefined criteria (recovery between 80–120 % and imprecision <20 %CV, Supplemental Table 5). As per CLSI EP06, deviation from linearity between quadratic and cubic regression models and the respective linear regression model was <6 % at each concentration.

Fig. 6.

Linearity. (A) A patient pool spiked with high concentrations of analytes (open circles) and a patient pool with lower concentrations of analyte (closed circles) were mixed in ratios of 3:1, 1:1 and 1:3 with analyte-negative plasma pool (i.e., analyte concentrations below the LLMI). The samples were analyzed in triplicate and the results are plotted as mean ± SD for (B) glucagon and (C) oxyntomodulin. Dotted lines represent the lines of identity. Panel A was developed in Biorender.

Analyte stability was assessed in plasma samples and in prepared samples. Analytes were stable in stored protease-inhibited plasma (i.e., <15 % loss of analyte) when incubated at room or refrigerated temperature for less than three hours or stored frozen for up to nine days (Supplemental Fig. 3). Two types of prepared samples were evaluated, one in autosampler vials as a liquid at the end of preparation, ready for injection onto the LC-MS/MS, and the other as dried pellets after protein precipitation. There was no apparent effect of incubating prepared liquid samples at 4 °C for 24 h or after freezing at –80 °C for two days to two weeks (Supplemental Fig. 4). There was also no effect of maintaining dried pellets after protein precipitation at –80 °C for up to two weeks.

Potential interference due to common matrix effects was evaluated using spike-recovery experiments with left-over clinical samples from the clinical laboratory. Although there was no interference due to chronic kidney disease, liver disease, or hyperlipidemia (i.e., elevated creatinine, bilirubin, or triglyceridemia, respectively), there was reduced recovery of analytes due to hemolysis, with less than 80 % recovery of spiked analyte from samples with ≥0.23 g/dL hemoglobin (Supplemental Fig. 5).

A comparison of spiked plasma and serum samples demonstrated a statistically significant difference in recovery between the sample types (p = 0.042 for glucagon and p < 0.001 for oxyntomodulin), consistent with analyte degradation in serum samples (Supplemental Fig. 6). When comparing the results from samples drawn into standard EDTA-anticoagulated blood collection tubes with or without the subsequent addition of DPP4-Plus, we observed a reduction in the observed concentrations of analytes when compared with P800 tubes [mean (IQR): –14.8 % (19.2 %) and –8.7 % (21.0 %) for glucagon in EDTA and EDTA/DPP4-Plus; –13.8 % (33.2 %) and –12.4 % (42.2 %) for oxyntomodulin in EDTA and EDTA/DPP4-Plus, respectively], supporting the use of protease-containing blood collection tubes for these analytes (Fig. 7A,B).

Fig. 7.

Analysis of participant samples. (A,B) Tube-type study for glucagon and oxyntomodulin (N = 29) comparing results from P800 blood collection tubes with EDTA-anticoagulated tubes (closed circles) or EDTA-anticoagulated tubes with DPP4-Plus protease inhibitors added (open circles). Dotted lines represent the lines of identity. (C-H) Comparison of results from P800 tubes (C,F), EDTA-anticoagulated tubes (D,G), and EDTA-anticoagulated tubes with protease inhibitors (E,H) for samples drawn from fasting participants with type 1 diabetes. Healthy controls are illustrated (black circles, N = 11) in comparison with patients with type 1 diabetes using injectable insulin (gray circles, N = 4) or an insulin pump (open circles, N = 14). Boxes denote the bounds of the first and third quartile along with the median in the middle. The range (excluding outliers) is shown as whiskers.

3.5. Glucagon in type 1 diabetes

As a pilot study, we investigated the fasting plasma concentration of glucagon and oxyntomodulin in participants with type 1 diabetes. For samples collected in P800 tubes, we observed lower concentrations of glucagon in patients with diabetes receiving insulin via an insulin pump compared with healthy controls (p = 0.039), but there was no difference when diabetic participants were treated with injectable insulin (Fig. 7C-H). The difference between participants with diabetes and those without was not statistically significant when comparing results from EDTA-anticoagulated plasma with DPP4-Plus, but was significant in EDTA plasma without inhibitors (p = 0.036). There was no correlation between duration of diabetes or body mass index. There were no statistically significant differences for oxyntomodulin, although there was a trend toward reduced concentrations in type 1 diabetes in all tube types.

4. Discussion

In our efforts to achieve the sensitivity required for the useful measurement of glucagon and oxyntomodulin, we tested multiple sample preparation methods, including protein precipitation, solid-phase extraction, and immunoaffinity enrichment. The combination of protein precipitation and immunoaffinity enrichment was successful, but only with a non-distributable antibody [20], which led us to make our own antibodies. Our new assay makes it possible to simultaneously quantify both analytes in plasma samples with the linearity, robustness, and sensitivity needed for human studies [36], [37], [38], [39], [40]. The use of LC-MS/MS overcomes many of the commonly encountered issues with immunoassays, particularly the lack of specificity inherent for analytes with identical amino acid sequences [16]. The method also overcomes the drawbacks of other LC-MS/MS methods that required larger sample volumes and/or less robust instrumentation [17], [18], [19], [20], [21], [22].

Biomedical science has long suffered from a lack of reproducibility between laboratories [41]. An inability to transfer knowledge and workflows among investigators is commonly cited as the most important reason for these discrepancies [42]. In addition, the poor quality (poor specificity, in particular) of many commercially manufactured immunoassays has also been blamed [43]. As part of the TaMADOR Consortium, we aim to generate transferable workflows that can be replicated in clinical laboratories so that findings in clinical research can have an immediate impact, should the biomarker be needed for clinical care [31]. To this end, we have developed a highly detailed SOP and distributable monoclonal antibodies that can be obtained by interested researchers from the Iowa Hybridoma Bank. We have also generated a well-characterized glucagon calibration material that can be used to harmonize results between laboratories adopting our method. Importantly, manufacturers could use this calibrator to ensure the metrological traceability of their commercial assays to SI units.

Proglucagon is relatively conserved in evolution. Indeed, glucagon and oxyntomodulin are identical in humans, mice, and rats. As a result, our assay should also be usable in murine models to study the biochemistry and physiology of these vital hormones in development and disease. This is particularly important given the fundamental knowledge that we have gained from animal studies of proglucagon-derived hormones [1], [44].

During development, we also discovered more information about glucagon and oxyntomodulin stability ex vivo. Based on studies with proteotypic peptides, early recommendations for peptide storage and handling focused on relatively low concentrations of acetonitrile and formic acid to stabilize peptides in liquid form [45]. It is important to remember that proteotypic peptides are often selected because they are stable in common workflows and chromatograph and ionize well during LC-MS/MS analysis [46]. But, when analyzing many endogenous biomarkers, we are faced with the reality that the biomarker cannot be proteolyzed before analysis, either because the peptide is too short or because proteolysis would discard important information. As a result, additional effort is often required to prevent adsorption or other loss of these non-ideal analytes during sample preparation. Newer recommendations take this information into account [47]. In our work, we identified DMSO as an effective additive during the peptide elution step. We also demonstrated the importance of having multiple protease inhibitors in blood collection tubes to enhance recovery of analyte. Although previous assays have used P800 tubes in their studies [20], [21], our data provide documentation of the benefit of these devices over standard tubes or the addition of inhibitors a few minutes after phlebotomy. Our data also demonstrate the importance of proper handling, especially processing or freezing samples within three hours after blood collection. This is in contrast to previous observations that demonstrated no preanalytical issues, although they used a less specific assay [48]. It is unclear if glucagon and oxyntomodulin are lost to adsorption, non-specific protein binding, chemical modification, or proteolysis, but proper preanalytical handling is clearly crucial for the generation of useful data in clinical research or clinical care.

The secretion of glucagon from α-cells is required for the maintenance of blood glucose concentrations during fasting [1], [49]. A drop in glucose and insulin concentrations stimulates glucagon release, which subsequently increases plasma glucose via hepatic glucose production. In patients with type 1 diabetes who have lost insulin secretion from their β-cells, the glucagon response to hypoglycemia is impaired, contributing to hypoglycaemia [50]. The inverse is also true, i.e., in patients without insulin from their β-cells, glucagon is not properly suppressed, contributing to hyperglycemia [40]. Previous studies have demonstrated that fasting glucagon is either the same or higher in patients with type 1 diabetes [36], [38], [40]. It was, therefore, surprising to observe significantly lower plasma levels of glucagon in patients with type 1 diabetes in our study. Considering that all of the participants with reduced glucagon concentrations were on closed-loop insulin pumps, rather than injectable insulin, our data suggest that better glycemic control with more consistent insulin infusion leads to lower plasma glucagon concentrations in patients with type 1 diabetes.

In addition to transferring our workflow to other laboratories, we aim to improve throughput by adapting the assay to 96-well plates. This will likely require changes in reagent volumes and incubation temperatures [51], but will result in an assay that can be more effectively deployed in larger clinical studies in the future.

5. Conclusions

In summary, we have developed a new method for the quantification of glucagon and oxyntomodulin in plasma along with a detailed SOP, publicly available monoclonal antibodies, and distributable calibration materials. These resources will facilitate future investigation into the role of these peptide hormones in glucose homeostasis and in the development, progression, and treatment of diabetes.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Jessica O. Becker: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Validation, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Sara K. Shijo: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Investigation. Huu-Hien Huynh: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Katrina L. Forrest: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal analysis. Michael J. MacCoss: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Michelle A. Emrick: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration. Elisha Goonatilleke: Writing – review & editing, Methodology, Investigation. Andrew N. Hoofnagle: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft, Visualization, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Funding

This work was funded by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health (U01DK121289 ANH, U01DK137097 ANH/MJM), the University of Washington Nutrition Obesity Research Center (P30DK035816), and the University of Washington Diabetes Research Center (P30DK017047).

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Michael J. MacCoss is a paid consultant for Thermo Fisher Scientific. The remaining authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper..

Acknowledgement

The authors thank Michael Lassman and Anita Lee for providing monoclonal antibodies to help with method development and for comparison studies.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jmsacl.2025.04.002.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Sandoval D.A., D'Alessio D.A. Physiology of proglucagon peptides: role of glucagon and GLP-1 in health and disease. Physiol. Rev. 2015;95:513–548. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00013.2014. PMID 25834231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Janah L., Kjeldsen S., Galsgaard K.D., Winther-Sorensen M., Stojanovska E., Pedersen J., Knop F.K., et al. Glucagon receptor signaling and glucagon resistance. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20:3314. doi: 10.3390/ijms20133314. PMID 31284506. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jiang G., Zhang B.B. Glucagon and regulation of glucose metabolism. Am. J. Physiol. Endocrinol. Metab. 2003;284:E671–E678. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00492.2002. PMID 1262632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gray S.M., Goonatilleke E., Emrick M.A., Becker J.O., Hoofnagle A.N., Stefanovski D., He W., et al. High doses of exogenous glucagon stimulate insulin secretion and reduce insulin clearance in healthy humans. Diabetes. 2024;73:412–425. doi: 10.2337/db23-0201. PMID 38015721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Shankar S.S., Shankar R.R., Mixson L.A., Miller D.L., Pramanik B., O'Dowd A.K., Williams D.M., et al. Native oxyntomodulin has significant glucoregulatory effects independent of weight loss in obese humans with and without type 2 diabetes. Diabetes. 2018;67:1105–1112. doi: 10.2337/db17-1331. PMID 29545266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pocai A. Action and therapeutic potential of oxyntomodulin. Mol. Metab. 2014;3:241–251. doi: 10.1016/j.molmet.2013.12.001. PMID 24749050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lafferty R.A., O'Harte F.P.M., Irwin N., Gault V.A., Flatt P.R. Proglucagon-derived peptides as therapeutics. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fendo.2021.689678. PMID 34093449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bak M.J., Albrechtsen N.W., Pedersen J., Hartmann B., Christensen M., Vilsboll T., Knop F.K., et al. Specificity and sensitivity of commercially available assays for glucagon and oxyntomodulin measurement in humans. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2014;170:529–538. doi: 10.1530/EJE-13-0941. PMID 24412928. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kobayashi M., Maruyama N., Yamamoto Y., Togawa T., Ida T., Yoshida M., Miyazato M., et al. A newly developed glucagon sandwich ELISA is useful for more accurate glucagon evaluation than the currently used sandwich ELISA in subjects with elevated plasma proglucagon-derived peptide levels. J. Diabetes Investig. 2023;14:648–658. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13986. PMID 36729958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Umberger T.S., Ming W., Cox J.M., Konrad R.J., Siegel R.W. Development of a selective, sensitive and robust oxyntomodulin dual monoclonal antibody immunoassay. Bioanalysis. 2022;14:1229–1239. doi: 10.4155/bio-2022-0084. PMID 36378599. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wewer Albrechtsen N.J., Hartmann B., Veedfald S., Windelov J.A., Plamboeck A., Bojsen-Moller K.N., Idorn T., et al. Hyperglucagonaemia analysed by glucagon sandwich ELISA: nonspecific interference or truly elevated levels? Diabetologia. 2014;57:1919–1926. doi: 10.1007/s00125-014-3283-z. PMID 24891019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brunner M., Moser O., Raml R., Haberlander M., Boulgaropoulos B., Obermayer-Pietsch B., Svehlikova E., et al. Assessment of two different glucagon assays in healthy individuals and type 1 and type 2 diabetes patients. Biomolecules. 2022;12 doi: 10.3390/biom12030466. PMID 35327658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kramer C.K., Zinman B., Choi H., Connelly P.W., Retnakaran R. Impact of the glucagon assay when assessing the effect of chronic liraglutide therapy on glucagon secretion. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2017;102:2729–2733. doi: 10.1210/jc.2017-00928. PMID 28472325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wewer Albrechtsen N.J., Veedfald S., Plamboeck A., Deacon C.F., Hartmann B., Knop F.K., Vilsboll T., et al. Inability of some commercial assays to measure suppression of glucagon secretion. J. Diabetes Res. 2016;2016 doi: 10.1155/2016/8352957. PMID 26839899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yoshizawa Y., Hosojima M., Kabasawa H., Tanabe N., Miyachi A., Hamajima H., Mieno E., et al. Measurement of plasma glucagon levels using mass spectrometry in patients with type 2 diabetes on maintenance hemodialysis. Kidney Blood Press. Res. 2021;46:652–656. doi: 10.1159/000518027. PMID 34515141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hoofnagle A.N., Wener M.H. The fundamental flaws of immunoassays and potential solutions using tandem mass spectrometry. J. Immunol. Methods. 2009;347:3–11. doi: 10.1016/j.jim.2009.06.003. PMID 19538965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Farre-Segura J., Fabregat-Cabello N., Calaprice C., Nyssen L., Peeters S., Le Goff C., Cavalier E. Development and validation of a fast and reliable method for the quantification of glucagon by liquid chromatography and tandem mass spectrometry. Clinica Chimica Acta; Int. J. Clin Chem. 2021;512:156–165. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2020.11.004. PMID 33181149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Howard J.W., Kay R.G., Jones B., Cegla J., Tan T., Bloom S., Creaser C.S. Development of a UHPLC-MS/MS (SRM) method for the quantitation of endogenous glucagon and dosed GLP-1 from human plasma. Bioanalysis. 2017;9:733–751. doi: 10.4155/bio-2017-0021. PMID 28488894. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Katahira T., Kanazawa A., Shinohara M., Koshibu M., Kaga H., Mita T., Tosaka Y., et al. Postprandial plasma glucagon kinetics in type 2 diabetes mellitus: comparison of immunoassay and mass spectrometry. J. Endocr. Soc. 2019;3:42–51. doi: 10.1210/js.2018-00142. PMID 30560227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee A.Y., Chappell D.L., Bak M.J., Judo M., Liang L., Churakova T., Ayanoglu G., et al. Multiplexed quantification of proglucagon-derived peptides by immunoaffinity enrichment and tandem mass spectrometry after a meal tolerance test. Clin. Chem. 2016;62:227–235. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.244251. PMID 26430077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Miyachi A., Kobayashi M., Mieno E., Goto M., Furusawa K., Inagaki T., Kitamura T. Accurate analytical method for human plasma glucagon levels using liquid chromatography-high resolution mass spectrometry: comparison with commercially available immunoassays. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2017;409:5911–5918. doi: 10.1007/s00216-017-0534-0. PMID 28801845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Renuse S., Benson L.M., Vanderboom P.M., Ruchi F.N.U., Yadav Y.R., Johnson K.L., Brown B.C., et al. (13)C(15)N: glucagon-based novel isotope dilution mass spectrometry method for measurement of glucagon metabolism in humans. Clin. Proteomics. 2022;19:16. doi: 10.1186/s12014-022-09344-2. PMID 35590248. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Holst J.J., Wewer Albrechtsen N.J. Methods and guidelines for measurement of glucagon in plasma. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019;20 doi: 10.3390/ijms20215416. PMID 31671667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Thienpont L.M., Van Uytfanghe K., Rodriguez Cabaleiro D. Metrological traceability of calibration in the estimation and use of common medical decision-making criteria. Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2004;42:842–850. doi: 10.1515/CCLM.2004.138. PMID 15327021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bunk D.M., Lowenthal M.S. Isotope dilution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry for quantitative amino acid analysis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2012;828:29–38. doi: 10.1007/978-1-61779-445-2_3. PMID 22125133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bunk D.M., Lowenthal M.S. Isotope dilution liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry for quantitative amino acid analysis. Methods Mol. Biol. 2019;2030:143–151. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-9639-1_12. PMID 31347116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.MacLean B., Tomazela D.M., Shulman N., Chambers M., Finney G.L., Frewen B., Kern R., et al. Skyline: an open source document editor for creating and analyzing targeted proteomics experiments. Bioinformatics. 2010;26:966–968. doi: 10.1093/bioinformatics/btq054. PMID 20147306. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Pino L.K., Searle B.C., Bollinger J.G., Nunn B., MacLean B., MacCoss M.J. The skyline ecosystem: informatics for quantitative mass spectrometry proteomics. Mass Spectrom. Rev. 2020;39:229–244. doi: 10.1002/mas.21540. PMID 28691345. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sharma V., Eckels J., Schilling B., Ludwig C., Jaffe J.D., MacCoss M.J., MacLean B. Panorama public: a public repository for quantitative data sets processed in skyline. Mol. Cell. Proteomics. 2018;17:1239–1244. doi: 10.1074/mcp.RA117.000543. PMID 29487113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cox H.D., Lopes F., Woldemariam G.A., Becker J.O., Parkin M.C., Thomas A., Butch A.W., et al. Interlaboratory agreement of insulin-like growth factor 1 concentrations measured by mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. 2014;60:541–548. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2013.208538. PMID 24323979. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Foulon N., Goonatilleke E., MacCoss M.J., Emrick M.A., Hoofnagle A.N. Multiplexed quantification of insulin and C-peptide by LC-MS/MS without the use of antibodies. J. Mass Spectrom. Adv. Clin. Lab. 2022;25:19–26. doi: 10.1016/j.jmsacl.2022.06.003. PMID 35734440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huynh H.H., Forrest K., Becker J.O., Emrick M.A., Miller G.D., Moncrieffe D., Cowan D.A., et al. A targeted liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry method for simultaneous quantification of peptides from the carboxyl-terminal region of type III procollagen, biomarkers of collagen turnover. Clin. Chem. 2022;68:1281–1291. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvac119. PMID 35906802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Huynh H.H., Kuch K., Orquillas A., Forrest K., Barahona-Carrillo L., Keene D., Henderson V.W., et al. Metrologically traceable quantification of 3 apolipoprotein E isoforms in cerebrospinal fluid. Clin. Chem. 2023;69:734–745. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvad056. PMID 37279935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Moncrieffe D., Cox H.D., Carletta S., Becker J.O., Thomas A., Eichner D., Ahrens B., et al. Inter-laboratory agreement of insulin-like growth factor 1 concentrations measured intact by mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. 2020;66:579–586. doi: 10.1093/clinchem/hvaa043. PMID 32232452. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Grant R.P., Hoofnagle A.N. From lost in translation to paradise found: enabling protein biomarker method transfer by mass spectrometry. Clin. Chem. 2014;60:941–944. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2014.224840. PMID 24812416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Borghi V.C., Wajchenberg B.L., Albuquerque R.H. Evaluation of a sensitive and specific radioimmunoassay for pancreatic glucagon in human plasma and its clinical application. Clinica Chimica Acta; Int. J. Clin. Chem. 1984;136:39–48. doi: 10.1016/0009-8981(84)90245-6. PMID 6692564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cooperberg B.A., Cryer P.E. Beta-cell-mediated signaling predominates over direct alpha-cell signaling in the regulation of glucagon secretion in humans. Diabetes Care. 2009;32:2275–2280. doi: 10.2337/dc09-0798. PMID 19729529. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Jauch-Chara K., Hallschmid M., Schmid S.M., Oltmanns K.M., Peters A., Born J., Schultes B. Plasma glucagon decreases during night-time sleep in type 1 diabetic patients and healthy control subjects. Diabet. Med. 2007;24:684–687. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-5491.2007.02116.x. PMID 17381498. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Sjoberg S., Ahren B., Bolinder J. Residual insulin secretion is not coupled to a maintained glucagon response to hypoglycaemia in long-term type 1 diabetes. J. Intern. Med. 2002;252:342–351. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2796.2002.01043.x. PMID 12366607. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Unger R.H., Aguilar-Parada E., Muller W.A., Eisentraut A.M. Studies of pancreatic alpha cell function in normal and diabetic subjects. J. Clin. Invest. 1970;49:837–848. doi: 10.1172/JCI106297. PMID 4986215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Begley C.G., Ellis L.M. Drug development: raise standards for preclinical cancer research. Nature. 2012;483:531–533. doi: 10.1038/483531a. PMID 22460880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Prinz F., Schlange T., Asadullah K. Believe it or not: how much can we rely on published data on potential drug targets? Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011;10:712. doi: 10.1038/nrd3439-c1. PMID 21892149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Rifai N., Watson I.D., Miller G. Commercial immunoassays in biomarkers studies: researchers beware! Clin. Chem. Lab. Med. 2013;51:249–251. doi: 10.1515/cclm-2013-0015. PMID 23382316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bethea M., Bozadjieva-Kramer N., Sandoval D.A. Preproglucagon products and their respective roles regulating insulin secretion. Endocrinology. 2021;162 doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqab150. PMID 34318874. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hoofnagle A.N., Whiteaker J.R., Carr S.A., Kuhn E., Liu T., Massoni S.A., Thomas S.N., et al. Recommendations for the generation, quantification, storage, and handling of peptides used for mass spectrometry-based assays. Clin. Chem. 2016;62:48–69. doi: 10.1373/clinchem.2015.250563. PMID 26719571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Paulovich A.G., Whiteaker J.R., Hoofnagle A.N., Wang P. The interface between biomarker discovery and clinical validation: the tar pit of the protein biomarker pipeline. Proteomics Clin. Appl. 2008;2:1386–1402. doi: 10.1002/prca.200780174. PMID 20976028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Maurer J., Grouzmann E., Eugster P.J. Tutorial review for peptide assays: an ounce of pre-analytics is worth a pound of cure. J. Chromatogr. B, Analyt. Technol. Biomed. Life Sci. 2023;1229 doi: 10.1016/j.jchromb.2023.123904. PMID 37832388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Cegla J., Jones B.J., Howard J., Kay R., Creaser C.S., Bloom S.R., Tan T.M. The preanalytical stability of glucagon as measured by liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry and two commercially available immunoassays. Ann. Clin. Biochem. 2017;54:293–296. doi: 10.1177/0004563216675648. PMID 27705885. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Cryer P.E. Minireview: glucagon in the pathogenesis of hypoglycemia and hyperglycemia in diabetes. Endocrinology. 2012;153:1039–1048. doi: 10.1210/en.2011-1499. PMID 22166985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Singer-Granick C., Hoffman R.P., Kerensky K., Drash A.L., Becker D.J. Glucagon responses to hypoglycemia in children and adolescents with IDDM. Diabetes Care. 1988;11:643–649. doi: 10.2337/diacare.11.8.643. PMID 3065002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huynh H.H., Barahona-Carrillo L., Moncrieffe D., Cowan D.A., Forrest K., Becker J.O., Emrick M.A., et al. A novel high-throughput immunoaffinity LC-MS/MS assay for P-III-NP and other fragments of type III procollagen in human serum. Drug Test. Anal. 2024 doi: 10.1002/dta.3814. PMID 39462787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.