Key Points

-

•

3D silk-based bone marrow niches and flow chambers direct the generation of compartmentalized erythropoietic niches.

-

•

Spatiotemporal control of ex vivo erythropoiesis determines erythrocyte membrane and cytoplasm remodeling through autophagy.

Visual Abstract

Abstract

The pursuit of ex vivo erythrocyte generation has led to the development of various culture systems that simulate the bone marrow microenvironment. However, these models often fail to fully replicate the hematopoietic niche's complex dynamics. In our research, we use a comprehensive strategy that emphasizes physiological red blood cell (RBC) differentiation using a minimal cytokine regimen. A key innovation in our approach is the integration of a 3-dimensional (3D) silk-based scaffold engineered to mimic both the physical and chemical properties of human bone marrow. This scaffold facilitates critical macrophage-RBC interactions and incorporates fibronectin functionalization to support the formation of erythroblastic island (EBI)–like niches. We observed diverse stages of erythroblast maturation within these niches, driven by the activation of autophagy, which promotes organelle clearance and membrane remodeling. This process leads to reduced surface integrin expression and significantly enhances RBC enucleation. Using a specialized bioreactor chamber, millions of RBCs can be detached from the EBIs and collected in transfusion bags via dynamic perfusion. Inhibition of autophagy through pharmacological agents or α4 integrin blockade disrupted EBI formation, preventing cells from completing their final morphological transformations, having them trapped in the erythroblast stage. Our findings underscore the importance of the bone marrow niche in maintaining the structural integrity of EBIs and highlight the critical role of autophagy in facilitating organelle clearance during RBC maturation. RNA sequencing analysis further confirmed that these processes are uniquely supported by the 3D silk scaffold, which is essential for enhancing RBC production ex vivo.

Introduction

Obtaining mature, enucleated red blood cells (RBCs) ex vivo remains a significant hurdle. One of the major challenges is the absence of comprehensive bone marrow (BM) models that accurately replicate the complex microenvironment in which erythropoiesis occurs.1 Recent advancements have resulted in the creation of consistent protocols capable of producing large quantities of cultured human reticulocytes (Rtics). These approaches predominantly use static systems, characterized by complex multistep culture methods, involving the selective addition or omission of specific components and growth factors, mixed at varying concentrations.1, 2, 3 Dynamic culture methods have also been explored to enhance the production of RBCs.4 Diverse bioreactor systems, including stirred tank bioreactors,5 spinner flasks,6 and roller bottles7 have been proposed for scalability. Beyond the effects of shear forces resulting from the movement of blood cells and fluids, the architecture and composition of the BM niche play a pivotal role in molding the processes of blood cell production.8,9 Erythropoiesis is sustained by the formation of distinct structures called erythroblastic islands (EBIs).10,11 EBIs feature a central macrophage surrounded by differentiating erythroid progenitors dispersed throughout the marrow.12,13 It has been extensively described that macrophages contribute to erythropoiesis and furnish iron for heme synthesis to developing erythroblasts.14, 15, 16, 17 Elvarsdóttir et al introduced a 3-dimensional (3D) system that enables longitudinal studies of maturing erythroid cells, with a specific emphasis on the formation of EBIs and enucleated Rtics.18 However, the simultaneous replication of the intricate 3D structure and function of EBIs remains unsolved, and methods to construct, modulate, and assess RBC production ex vivo are underdeveloped.

Silk fibroin, a complex protein derived from the silk fibers of Bombyx mori, is widely used in tissue engineering due to its biocompatibility, controllable degradability, and tunable mechanical properties. Furthermore, silk fibroin possesses several important traits, such as the capacity for incorporating bioactive substances and cells, flexibility, water stability due to its self-assembly, and customizable strength.19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25 This study aimed to exploit silk fibroin as a biomaterial to replicate key features of the BM niche to support the establishment of erythropoietic clusters, resembling native EBIs and facilitating the production of enucleated RBCs. A key advantage of this system was the ability to noninvasively observe and analyze the formation and maturation of EBIs, along with a nondestructive method for harvesting enucleated RBCs into transfusion bags. Through this approach, we demonstrated that the generation of enucleated RBCs within EBI-like structures involves adhesion to fibronectin, interaction with macrophages, cytoplasmic organelle clearance, membrane receptor remodeling, and eventual RBC enucleation ex vivo. RNA sequencing analysis further revealed that the 3D silk model, compared with 2D cultures, triggered distinct cellular responses, including the upregulation of genes involved in autophagic pathways, which drive terminal RBC maturation. By providing an instructive, silk-based microenvironment, we simplified the culture protocol, creating an easy-to-use system that streamlines human RBC production. This approach enhances scalability, reproducibility, and accessibility for a wide range of medical and laboratory applications.

Materials and methods

Human RBC differentiation

Human hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) were obtained from healthy donors after informed consent, in accordance with the Istituto di Ricovero e Cura a Carattere Scientifico Policlinico San Matteo Foundation of Pavia and the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. CD34+ HSPCs were selected by an immune-magnetic bead selection kit (CD34 MicroBead Kit; Miltenyi Biotec)26 and cultured in the presence of Stem Span medium (STEMCELL Technologies) supplemented with 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% l-glutamine (Euroclone), 10 ng/mL interleukin-3, 20 ng/mL erythropoietin (PeproTech), and 1600 ng/mL holo-transferrin (Merck Life Science) for 3 weeks. Starting from day 3 of the culture, the concentration of holo-transferrin increased to 800 μg/mL.

Samples were cocultured with macrophages derived from CD14+ monocytes isolated from the same sample using an immune-magnetic bead selection kit (CD14 MicroBeads; Miltenyi Biotec).27,28 Macrophages were expanded in RPMI 1640 medium (Euroclone), supplemented with fetal bovine serum (Gibco), 1% penicillin-streptomycin, 1% l-glutamine, and 50 ng/mL macrophage colony-stimulating factor (PeproTech), before being seeded into the silk scaffolds. Macrophage-HSPC coculture was performed at a ratio of 1:4 (1 × 105 macrophages/4 × 105 HSPCs per scaffold).

In some experiments, samples were treated with 10 μM (final concentration) 1-naphthyl PP1, 1 μM (final concentration) SBI-0206965, or anti-α4 antibody (clone 9F10).29 Incubation started on day 7 of culture.

Silk bone marrow fabrication, assembly, and perfusion

Silk fibroin aqueous solution was obtained from B mori silkworm cocoons according to previously published literature.30 To reproduce the spongy architecture and composition of the BM niche, the silk solution (8% weight-to-volume ratio) was mixed with human fibronectin (Merck Life Science) to a final concentration of 25 μg/mL and dispensed into a molding chamber. Alternatively, fibronectin was coated directly onto the silk scaffolds.23 NaCl particles (Fisher Scientific) having a 500-μm diameter were selected using a sifter (Fisher Scientific) and then sifted into the solution.30 The scaffolds were placed at room temperature for 48 hours and finally soaked in distilled water to leach out the NaCl particles. The scaffolds were sterilized and rinsed in the culture medium before cell seeding.

The dynamic perfusion of the silk BM scaffold was performed at 70 μL/min by using a peristaltic pump (ShenChen Flow Rate Peristaltic Pump; LabV1) connected to a bioreactor chamber manufactured using 3D stereolithography (SLA) printing technology. The chamber was designed using Computer-aided design software (Fusion 360) to generate Standard Triangulation Language files that were then exported to the SLA 3D printer Form 3B (Formlabs) for fabrication. The chamber consists of a single well, measuring 20 mm (L) × 5 mm (W) × 5 mm (H), with 3 independent inlets of 3-mm diameter and 3 outlet channels converging into 1 main drainage to allow collection into transfusion bags. The printing was performed using the Biomed Clear biocompatible resin, cured in layers of 100 μm. The resulting bioreactor chamber was washed with isopropyl alcohol to remove unpolymerized resin and then cured in a UV oven for 1 hour. Preliminary perfusion studies have been conducted using peripheral blood RBCs. The analyses before and after perfusion were conducted using SYSMEX XN-1000.

Flow cytometry

For the analysis of erythroid differentiation, samples collected at different days of differentiation were suspended in phosphate-buffered saline and stained with stemness-related markers (CD34, CD117, CD45, and HLA; Becton Dickinson), erythroid-associated markers (CD36 and CD71 from Abcam; CD235 from Life Technologies), integrins (α2, α4, α5, and β1 from eBioscience), BioTracker 488 Nuclear Stain (1:1000), or 100 ng/mL Hoechst (Merck Millipore) at room temperature in the dark for 30 minutes (supplemental Table 1 includes all antibody details). A minimum of 104 events was acquired using a FACSLyric (Becton Dickinson). Trucount tubes (Becton Dickinson) were used to count RBCs. Offline data analysis was performed using the Kaluza software package (Beckman Coulter). The gating strategy for RBCs was established based on human peripheral blood RBCs’ forward scatter (FSC) and side scatter (SSC) patterns, identified as CD36–CD71–CD235+ cells (supplemental Figure 1; Figure 4B).

Figure 4.

Tailored perfusion approach for the collection of ex vivo–produced RBCs. (A) SEM showing the presence of biconcave enucleated RBCs (i-iv), at the periphery of EBIs (white arrows indicate biconcave RBCs; scale bar, 100 μm [panel Ai]; scale bar, 10 μm [panel Avi], scale bar, 20 μm [panel Av]); the bioreactor (v-vi) was connected to gas-permeable tubes to allow the medium to flow inside the silk scaffold. (B) Flow cytometry analysis shows no major differences between ex vivo–cultured RBCs and those obtained from human peripheral blood. (C) Analysis of mean corpuscular hemoglobin (MCH) performed with the Drabkin reagent using RBC from peripheral blood or from the ex vivo 3D culture (p = not significant). (D) Flow cytometry analysis of nuclear staining performed with BioTracker 488. The red histogram corresponds to CD36–CD71–CD235a+ cells; the pink histogram corresponds to the representative gating of nucleated CD71+CD35+ cells at an early stage of differentiation, which have been used as reference controls. (E) Parallel samples (i) have been imaged by epifluorescence microscopy (red, CD235; green, nuclei; scale bar, 5 μm); peripheral blood RBCs have been used as reference control (ii); SEM analysis (iii-iv) of collected RBCs; cells show morphological features of native RBCs, including the biconcave discoidal shape (scale bar, 2 μm [panel Eiii]; scale bar, 3 μm [panel Eiv]); transmission electron microscopy (v-vii) of collected RBCs. Enucleated cells show few small mitochondria and some residual glycogen deposits (scale bar, 1 μm [panel Ev]; scale bar, 500 nm [panel Evi]; scale bar, 1 μm [panel Evii]). Gly, glycogen; M, mitochondria.

Statistics

Values are expressed as mean ± standard deviation or median and range. Box and whiskers plots depict the upper and lower values (lowest and highest horizontal line, respectively), and lower/upper quartiles with median value (box). Student t test or 1-way analysis of variance followed by Bonferroni posttest was used to analyze experiments. P value < .05 was considered statistically significant. All experiments were independently repeated 3 times, unless specified otherwise.

Results

Design, fabrication, and characterization of the silk bone marrow model

The BM niche is a highly specialized microenvironment that orchestrates localized erythropoiesis through physical, cellular, and chemical factors.31,32 We adopted a comprehensive approach replicating these key dynamics to create a model that best supports physiological RBC differentiation. The extracellular matrix composition of the native BM plays a critical role in hematopoiesis, forming a distinct environment (Figure 1A). Our analysis of human and murine BM biopsies revealed that fibronectin fibers are distributed throughout the marrow space, particularly near erythroid nests and extensively within EBIs (Figure 1B-C). Drawing inspiration from this natural microenvironment, we developed 3D silk-based scaffolds designed to guide specific cellular interactions and development. The niche model was fabricated using a salt-leaching method, in which a silk fibroin solution mixed with salt particles and human fibronectin was patterned in a molding chamber (Figure 1D). A 3-day production process yielded sterile silk-fibronectin 3D constructs (Figure 1D-E). Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) analysis showed distinct microniches within the scaffold, with uniformly distributed pores of variable diameters replicating the spongy architecture of the marrow (Figure 1F-H). Confocal imaging confirmed that fibronectin was predominantly localized on the surface of the silk scaffolds (Figure 1I). The scaffold supported rapid absorption of human peripheral blood RBCs, ensuring uniform distribution without affecting cell morphology (Figure 1J). Hydraulic conductivity, measured using the Darcy coefficient, revealed significant permeability, which is critical for simulating the natural perfusion of RBCs from the BM into circulation (Figure 1K). The 3D silk BM model was housed in a customized flow chamber designed to mimic the bloodstream, featuring a central core linked to gas-permeable tubing, 3 inlet ports for medium perfusion, and 3 outlet channels converging into a single drainage point for collection into transfusion bags (Figure 1L-M). The system was validated by perfusing human RBCs, with postperfusion analysis showing comparable cell shape, size, and physiological parameters, indicating preserved cellular integrity (supplemental Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Manufacturing of the silk bone marrow model. (A) Schematic representation of erythropoiesis inside the bone marrow, where EBIs originate and give rise to Rtics that finally mature inside the blood vessels. (Bi-ii) E-cadherin and fibronectin immunostaining of a human bone marrow biopsy paraffin section (scale bar, 250 μm) (i-ii); the analysis of sequential sections shows E-cadherin–positive erythroid nest next to CD68+ macrophages, all immersed in a matrix of fibronectin fibrils (scale bar, 25 μm) (iii-iv). (C) Confocal microscopy analysis of mouse bone marrow biopsy (i-ii); cross-section analysis (iii) shows that fibronectin is interspersed within and around the EBI (red, Ter119; green, fibronectin; blue, nuclei; scale bar, 10 μm). (D) Schematic illustration of silk bone marrow model production starting from B. mori cocoons. The scaffold is prepared by dispensing an aqueous silk solution, mixed with salt particles and fibronectin. After leaching out the salt, the resulting porous scaffold can be sterilized and stored at 4°C until use. (E) Silk fibroin constructs mimicking the spongy structure of the bone marrow (scale bar, 5 mm). (F-G) SEM of silk scaffold (scale bar, 300 μm). The pores are highlighted in green. (H) Distribution of pore diameter frequencies. (I) Confocal microscopy analysis of silk-fibronectin scaffold (yellow, fibronectin; gray, silk; scale bar, 100 μm). (J) RBCs from human peripheral blood were perfused inside the scaffold to test the system's efficiency. The spongy model supported the distribution of RBCs throughout the niches of the scaffold (scale bar, 10 μm). (K) Calculation of the Darcy coefficient demonstrated effective hydraulic conductance. (L) Computer-aided design modeling of the perfusion flow chamber. The device includes 3 main inlet ports that provide the diffusion of the medium inside the central core, which is the lodgment for the silk bone marrow scaffold and one outlet port connected to a collection bag. (M) Flow chamber realized with a biocompatible resin (scale bar, 5 mm), housing the silk scaffold. The system can be perfused by a peristaltic pump. A, cross-sectional area; FNC, fibronectin; L, length; p, pressure.

Tracking erythropoiesis within the silk bone marrow

We used a simplified culture regimen with minimal erythropoietin and interleukin-3 concentrations, deliberately excluding stem cell–associated cytokines to promote physiological differentiation of HSPCs rather than expansion. Additionally, we cocultured HSPCs with macrophages, which are known to play a critical role in erythropoiesis by supplying iron and ferritin to maturing erythroblasts and by phagocytosing expelled nuclei at the end of differentiation. This approach aimed to replicate natural cell-cell interactions found in the BM.33,34 Our culture method was straightforward, involving the initial seeding of HSPCs into the silk-fibronectin scaffold, followed by a differentiation period of up to 21 days (Figure 2A). This streamlined protocol reduces the complexity and variability often associated with in vitro erythropoiesis models. Moreover, the silk scaffold allowed for direct visualization of RBC development without compromising its structural integrity, facilitating systematic analysis throughout the differentiation process. We observed the spontaneous formation of 143 ± 38 cellular nests per mm3 within the silk scaffold, closely resembling EBI-like clusters. As the culture progressed, cells within these foci underwent significant remodeling, transitioning from a CD71+CD235– phenotype to a CD71+CD235+ phenotype and eventually to CD71lowCD235+ RBCs (Figure 2B-C). Mature CD235+ RBCs were found clustered around and adjacent to cocultured macrophages (Figure 2D-E), a pattern similar to that observed in native human and murine BM specimens (Figure 2E; supplemental Figure 2A-B). The silk BM niche also supported substantial volumetric growth of the EBI-like clusters, with a marked increase in size during the later stages of differentiation, as quantified using automated image segmentation analysis (Figure 2F; supplemental Figure 2C-D). Flow cytometry confirmed the progression from stemness to lineage-specific markers, including CD36, CD71, and CD235, with peripheral blood RBCs used as reference controls (supplemental Figures 3 and 4). On day 7, we observed a predominant population of FSChigh-SSChigh-CD36+-CD71high-CD235low progenitors, which we defined as the “young” cell population (Figure 2G-I). By day 14, a main population of FSCmid-SSCmid-CD36low-CD71+-CD235+ cells emerged, representing the “middle” cell population (Figure 2G-I). From day 21 onward, cell size and cytoplasmic complexity decreased, with a concurrent increase in cell maturation. This was indicated by the presence of FSClow-SSClow-CD36–-CD71low-CD235high cells, referred to as the “old” cell population, which marked the final stage of RBC maturation (Figure 2G-I).

Figure 2.

Development of EBI-like niches inside the silk bone marrow model. (A) Schematic representation of cell culture workflow. (B) Confocal microscopy analysis of the silk bone marrow model during the culture. The image shows RBCs spontaneously aggregating in cellular nests reminiscent of EBIs (red, CD235a; green, CD71; blue, nuclei; scale bar, 20 μm). (C) Statistical analysis of the percentage of CD71+ and CD235a+ cells into the islets at different days of culture (n = 3; ∗P < .05). (D) Confocal microscopy images showing enucleated RBCs localized at the periphery of the erythropoietic island next to cocultured macrophages (red, CD235a; green, CD68; blue, nuclei/silk; red arrow, enucleated RBC; green arrow, macrophage; scale bar, 10 μm). (Ei-ii) May-Grunwald Giemsa staining of EBI-like niches obtained in the co-culture (scale bar, 5 μm). (E) Hematoxylin and eosin staining (i-ii) of human bone marrow specimen showing the presence of the erythron (scale bar, 25 μm; the white arrows indicate the infiltrating macrophage); SEM (v) of macrophage-RBC coculture inside the scaffold (red arrow, enucleated RBC; green arrow, macrophage; scale bar, 10 μm). (F) Statistical analysis of the volume of the EBIs at different days of culture, as assessed by automated image segmentation analysis (n = 100; P < .01). (G) Gating strategy for flow cytometry analyses based on FSC and SSC settings. The “young” population corresponds to FSChighSSChigh events, the “middle” population corresponds to FSCmidSSCmid events, and the “old” population corresponds to FSClowSCClow events. (H) Percentage of cells analyzed in the different gates. The “old” population is enriched at the end of the culture (n = 15; ∗∗P < .01; ∗P < .05). (I) Analysis of the MFI for CD36, CD71, and CD235a in the “old,” “middle,” and “young” populations (n = 15; ∗P < .05). MFI, mean fluorescence intensity.

Deciphering RBC maturation ex vivo

The gradual and effective maturation of EBIs and associated membrane remodeling are essential for ensuring optimal cellular responsiveness to cytokine signals, hemoglobin accumulation, and iron incorporation. In our model, we observed the regulated expression of key iron-handling proteins, including transferrin receptor 1 and ferritin, which indicated a fully functional machinery for iron uptake and storage (supplemental Figure 5A,C). Hemoglobin subunits α, β, and γ were all expressed, and a ∼500-fold increase in hemoglobin subunit α production was quantified (supplemental Figure 5B-D), accompanied by the presence of iron deposits within the cytoplasm (supplemental Figure 5E). Orthogonal section analysis revealed stage-dependent localization of band 3, a membrane protein anchoring the cytoskeleton. Larger, CD235low/– cells exhibited low or absent band 3 expression, whereas smaller, CD235high RBCs showed a fully positive band 3 signal (supplemental Figure 5F). Additionally, maturing RBCs expressed adhesion molecules, including integrins, which are crucial for recognizing fibronectin and mediating erythroblast-macrophage interactions, thus guiding distinct temporal steps in erythropoiesis.17,33,35 We found that maturing RBCs within the silk niche progressively lost expression of integrins α2, α4, α5, and β1 (supplemental Figure 6A). Specifically, the FSClow-SSClow-CD71low-CD235+ “old” cell population showed significantly reduced integrin expression compared with the FSChigh/mid-SSChigh/mid-CD71+ “young” and “middle” populations (supplemental Figure 6A). Notably, the α4β1 integrin axis played a critical role in early erythroblast development by facilitating cell adhesion, signaling, and the establishment of cell-cell and cell-microenvironment interactions, which are essential for commitment to terminal maturation, and studies in α4 conditional knockout mice demonstrate an impaired response to erythropoietic stress.35, 36, 37 EBI formation was disrupted when cells were treated with an anti-α4 antibody within the silk BM model (supplemental Figure 6B). This treatment impaired spatial organization and resulted in defective maturation of the “old” cell population compared with the untreated control (supplemental Figure 6C). The maturation status of erythroblasts is also reflected in nucleus size, chromatin localization and condensation, and the depletion of subcellular organelles. Electron micrograph analysis during differentiation revealed significant alterations in cell size and ultrastructure (Figure 3). Proerythroblasts were characterized by a higher nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio (Figure 3A-B), which gradually shifted as chromatin condensed and cytoplasm decreased, transforming into basophilic erythroblasts (Figure 3C-D) and subsequent polychromatic erythroblasts (Figure 3E). Orthochromatic erythroblasts (OrthoEs) displayed densely pyknotic nuclei, electron-dense chromatin, and a significantly reduced nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio compared with earlier stages (Figure 3F-G). Proerythroblasts showed abundant endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria (Figure 3B). A progressive decline in mitochondria number was observed starting from basophilic erythroblasts to polychromatic erythroblasts and OrthoEs. Significant mitochondrial loss and the presence of dark granules, identified as glycogen deposits, in OrthoEs and Rtics (Figure 3F-I) hinted at a preparatory shift from oxidative metabolism to glycolysis as RBCs mature.38 These findings aligned with recent transcriptomic and proteomic data showing that peripheral blood Rtics and RBCs do express glycogen synthase and phosphorylase.39,40

Figure 3.

Transmission electron microscopy reveals changes in cell ultrastructure. (A-B) Transmission electron microscopy images showing proerythroblasts (ProEs) with a high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio and abundant endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria (scale bar, 2 μm [panel A]; scale bar, 500 nm [panel B]). (C-E) ProEs progressively condense chromatin and loses cytoplasm, thus transforming into basophilic erythroblasts (BasoEs) and polychromatic erythroblasts (PolyEs), with a significant decrease in mitochondria content (scale bar, 2 μm). (F-H) OrthoE appears with pyknotic nuclei, electron-dense chromatin, a reduced nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, and few mitochondria. The typical presence of dark granules, identified as glycogen deposits, is visible (scale bar, 1 μm). (I) OrthoE progressively loses all mitochondria and switches to one of the final stages of RBC maturation represented by Rtics, marked by glycogen granules (scale bar, 1 μm). ER, endoplasmic reticulum; Gly, glycogen; M, mitochondria; N, nucleus.

Harvesting RBCs via EBI perfusion

SEM of the 3D culture revealed the distinct localization of enucleated Rtics, identified by their biconcave discoid shape, predominantly at the periphery of EBIs (Figure 4Ai-iv). We proceeded to harvest the more mature cells by perfusing the system. The scaffold was placed in a custom-designed flow chamber, in which culture medium was perfused through the system, mimicking blood flow, and collected in gas-permeable bags at the outlet (Figure 4Av-vi). Flow cytometry analysis showed that the physical properties and maturation profile of the collected cells were comparable with those of RBCs from adult peripheral blood (Figure 4B). The number of mature CD36–CD71–CD235+ RBCs was determined using a Trucount bead standard, yielding an average of (4.6 × 106) ± (0.5 × 106) RBCs per scaffold. Perfusion of multiple scaffolds resulted in a proportional increase in RBC yield, demonstrating the scalability and efficiency of the model. Hemoglobin content in the ex vivo–collected RBCs was similar to peripheral blood RBCs, as quantified using the Drabkin method (Figure 4C). The mean corpuscular volume of the ex vivo RBCs (98 ± 12 fL) was slightly, although not significantly, larger than that of native RBCs, consistent with the early developmental stage of newly formed RBCs, which continue to remodel their membrane composition and volume during circulation.41, 42, 43 Nuclear staining with a live-cell imaging dye indicated that 84% ± 6% of ex vivo–produced RBCs were enucleated (Figure 4D-Ei), compared with 100% enucleated cells in peripheral blood (Figure 4Eii). These findings were confirmed using Hoechst staining (data not shown). SEM revealed morphological features typical of physiological erythropoiesis (Figure 4Eiii-iv), including the characteristic biconcave discoid shape of mature enucleated RBCs. Ultrastructural analysis of ex vivo–collected RBCs showed the presence of a few small mitochondria and residual glycogen deposits (Figure 4Ev-vii).

Controlling autophagy supports erythropoiesis in the silk bone marrow model

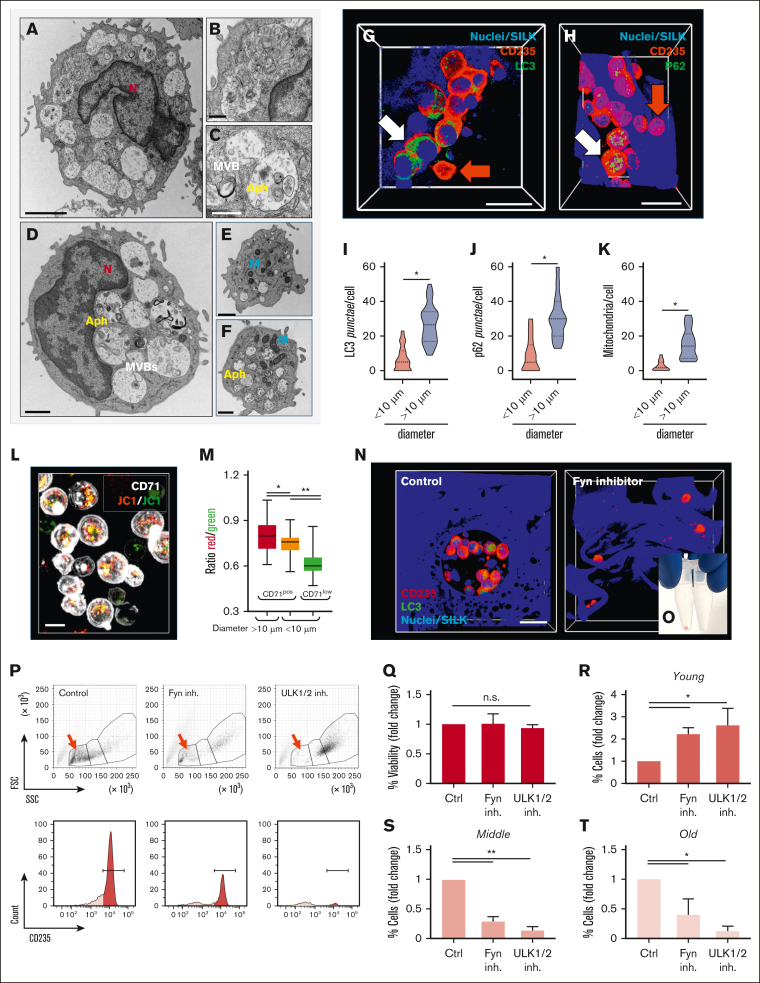

To provide a detailed molecular analysis of cells cultured in the 3D silk BM tissue model compared with 2D plastic plates, cultured with the same medium composition, we performed RNA sequencing. Differential gene expression (DEG) analysis was used to identify significant changes in gene expression between the 3D and 2D cultures during both early- and late-stage differentiation. The results visualized using volcano plots compare gene expression profiles under various conditions: “early 3D” vs “early 2D”; “late 3D” vs “late 2D”; “late 2D” vs “early 2D”; and “late 3D” vs “early 3D” (Figure 5A). These plots, along with heat map clustering of DEGs (Figure 5B), identified a significantly larger set of differentially expressed genes during the late stages of erythropoiesis in the 3D model than in the 2D cultures, with changes beginning at the early differentiation stage. This clustering supports the idea that specific gene sets are coordinately regulated throughout erythroblast maturation in the silk BM model. To gain deeper insight into the biological processes influenced by these DEGs, we performed gene ontology analysis. Pathways related to autophagy, endocytosis, and lysosomal function were significantly enriched among the upregulated genes, highlighting a crucial role for autophagy in erythropoiesis within the 3D silk scaffold (Figure 5C). In contrast, cell cycle–related pathways were downregulated during late-stage maturation in the 3D environment compared with both early-stage maturation and the 2D culture, indicating a regulated shift from proliferation to final maturation. This transition underscores the importance of erythroblasts exiting the cell cycle to efficiently undergo terminal differentiation in the 3D system. Furthermore, the analysis of reads per kilobase of transcript per million mapped reads of genes related to autophagy/mitophagy (eg, ATGs, UCHL1, ULK1, ULK2, FYN, DRAM1, DRAM2, and VDAC) and vesicle/membrane trafficking (eg, SNX18, SNX33, SPTBN1, TBC1D12, TBC1D14, and TFEB) provided quantitative insights into their controlled regulation during erythropoiesis in the 3D model (Figure 5D). Efficient clearance and recycling of intracellular organelles, membranes, and surface proteins, such as receptors and integrins, are driven by the formation of endosomes, multivesicular bodies (MVBs), and activation of autophagy.38,43, 44, 45, 46, 47 Erythroblasts from the silk BM model frequently showed abundant MVBs, characterized by electron-translucent vacuoles containing nanometer-sized vesicles, and autophagosomes, identified as double-membraned vesicles engulfing cellular material for degradation, indicating robust membrane trafficking during maturation (Figure 6A-D). Interestingly, enucleation did not entirely halt autophagic activity, because small autophagosomes were occasionally observed in Rtics, which had already undergone significant cytoplasmic and organelle loss (Figure 6E-F). This suggests that autophagy might continue after RBCs leave EBIs to complete their maturation in circulation. Quantification of LC3B+ and p62+ punctae in the cytoplasm, markers of autophagy induction, revealed heterogeneity in autophagic activity within these structures. Larger cells exhibited significantly more LC3B+ and p62+ punctae than smaller cells (Figure 6G-J). Enucleated CD235+ RBCs displayed fewer LC3B and p62 signals, suggesting a dynamic, maturation-driven reduction in autophagy activity. Notably, fewer mitochondria were observed in smaller RBCs than larger ones (Figure 6K), and mitochondrial depolarization, a trigger and consequence of autophagy induction, was confirmed using the JC-1 dye, which showed peak depolarization in small CD71low RBCs (Figure 6L-M). To explore the role of autophagy in RBC maturation within the silk niche, we performed pharmacological inhibition of autophagy using 2 distinct approaches. Inhibition of Fyn, an Src family kinase critical for autophagy and erythropoiesis in mice,48 or ULK1/2, essential kinases for autophagy initiation,49 led to impaired EBI formation. Treated samples lacked the typical clustering of erythroblasts, with minimal LC3B punctae detected (Figure 6N). Treated RBCs also showed reduced hemoglobin content, as evidenced by their pale appearance compared with controls, indicating defective iron uptake (Figure 6O). Accordingly, both inhibitors caused a marked impairment in erythropoiesis, with cells predominantly arrested in the immature “young” stage throughout the 3-week culture and only a few mature CD235high RBCs detected in the “middle” and “old” populations (Figure 6P-T).

Figure 5.

Comparative analysis of differential gene expression and pathway enrichment between 2D and 3D cultures at early and late stages of erythrocyte development. (A) Volcano plots illustrating the differential gene expression analysis across different comparisons: early 3D vs early 2D, late 3D vs late 2D, late 2D vs early 2D, and late 3D vs early 3D (total n = 8). Each dot represents a gene, with the red dots indicating significantly upregulated genes (adjusted P value < .05 and |log2FoldChange| >.5) and blue dots indicating significantly downregulated genes based on the same thresholds. Nonsignificant genes are shown in gray. (B) Heat map of hierarchical clustering showing the expression profiles of DEGs across various conditions. Red and blue blocks on the left represent groups of genes that are significantly upregulated or downregulated, respectively, with the color intensity reflecting the expression levels (scaled as z scores). (C) Gene ontology (GO) enrichment analysis for upregulated and downregulated pathways. The dot size represents the ratio of differentially expressed genes to the total genes in each GO term, whereas the color intensity indicates the statistical significance of the enrichment (−log10 P value adjusted). (D) Heat map depicting the average expression levels of selected genes across different conditions. Color intensity represents the scaled expression (z scores) of each gene, with the color bar indicating the scale range. DN, downregulated; L2FC, Xlog2 fold change; UP, upregulated.

Figure 6.

Autophagic activation during RBC maturation supports the maturation of EBI-like niches. (A-C) Transmission electron microscopy analyses of MVBs and Aphs in basophilic erythroblasts (BasoEs) and polychromatic erythroblasts (PolyEs) (3A scale bar, 2 μm [Figure 3A]; scale bar, 500 nm [Figure 3B]; scale bar, 500 nm [Figure 3C]). (D-F) OrthoE and Rtics also show content of double-membrane vesicles (scale bar, 1 μm [panel D]; scale bar, 1 μm [panel E]; scale bar, 500 nm [panel F]). (G-H) Confocal microscopy images showing CD235a cells positive to LC3B and p62 (red, CD235a; green, LC3B/p62; blue, nuclei per silk; white arrow, double positive cells; red arrow, CD235+ cells; scale bar, 10 μm [Figure 3G]; scale bar, 20 μm [Figure 3H]). Statistical analyses of LC3B+ (I) and p62+ punctae (J) and mitochondria content (K) (n = 100; ∗P < .05). (L) Confocal microscopy analysis showing JC1 staining in CD71low and CD71+ cells (red, JC1 aggregate form; green, JC1 monomeric form; white, CD71; scale bar, 10 μm). (M) Red-to-green ratio analysis shows that depolarization mainly occurs in small CD71low cells (n = 180; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01). (N) Confocal microscopy analyses of the silk bone marrow model during the culture in the presence or not of 10 μM 1-naphthyl PP1 (Fyn inhibitor). Images show cellular nests enriched in CD235a+LC3B+ cells in control conditions, while under treatment with 1-naphthyl PP1 CD235a+LC3B– cells are mainly distributed as single cells inside the silk scaffolds (red, CD235a; green, LC3B; blue, silk/nuclei; scale bar, 25 μm). (O) The loss of the typical red appearance of cells from samples treated with Fyn inhibitor demonstrates ineffective iron uptake with respect to controls. (P) As demonstrated by flow cytometry gating, inhibition of autophagy leads to a depletion of cells in the “old” population gate (red arrow) with respect to the control. Analyses show an evident downregulation of CD235a expression of the “old” population treated with Fyn and ULK1/2 inhibitors. (Q) Analysis of cell viability under different treatments (n = 3; p = not significant). Flow cytometry analyses show that (R) the “young” population evidence an increase of the total amount of cells in the presence of inhibitors with respect to the control (n = 3; ∗P < .05). By contrast the (S) “middle” and the (T) “old” populations evidence a reduced cell number in the presence of inhibitors with respect to the control (n = 3; ∗P < .05; ∗∗P < .01). Aph, autophagosome; Ctrl, control; inh., inhibitor; M, mitochondria; N, nucleus; n.s., not significant.

Discussion

To investigate the multistep maturation process of human RBCs in the BM, we developed a silk-based 3D scaffold that replicates the physical and chemical attributes of the BM microenvironment. Central to our approach is reproducing the spongy structure of BM niches and functionalizing them with fibronectin. This strategy was inspired by the observation that in vivo fibronectin fibers are interspersed within EBIs, supporting their integrity and facilitating RBC maturation. The α4β1 integrin is responsible for fibronectin recognition and binding.17,33,35 α4 integrin is a marker of early stages of erythropoiesis, because its expression decreases during maturation, whereas the expression of CD235a and band 3 increases.3

In our silk BM model, EBIs formed naturally through the interaction of HSPCs and macrophages. Macrophages play crucial roles in RBC maturation by supplying iron for heme synthesis and delivering ferritin to developing erythroblasts.33,34 Additionally, they support maturation into Rtics by phagocytosing expelled nuclei at the end of differentiation.17,33 It is known that both RBCs and macrophages express adhesion molecules involved in maintaining EBI integrity, including α4β1 integrin on erythroblast surface and CD163 on macrophages.17,33 Disruption of α4β1 axis leads to erythropoietic abnormalities and reduced EBI formation.36,37,50 Human CD34+ HSPCs with silenced α4 subunit showed an acceleration of erythroid differentiation, likely due to antiproliferative signals in early progenitors, and significantly impaired enucleation.51 Our findings highlight the critical role of the fibronectin-silk niche in preserving EBI structure, thereby facilitating RBC maturation. We have confirmed that mature CD71–CD235+ RBCs downregulate the expression of surface integrins,3 leading to the loss of cell adhesion to fibronectin and macrophages. This facilitates their recovery into the medium flow and collection into transfusion bags. We acknowledge that using in vitro–derived macrophages is a limitation of our study, because they may not fully capture the heterogeneity of the native BM niche. However, our newly developed protocol offers a proof of concept for generating EBI-like structures. In support of this claim, EBIs maintained their structural integrity under perfusion, whereas maturing enucleated RBCs gradually detached and entered the flow.

During erythropoiesis, the efficient removal of intracellular organelles, membranes, and surface proteins, such as transferrin receptors and integrins, is facilitated by MVBs and the activation of autophagy, a critical cellular process.44, 45, 46, 47,52,53 Disruption of autophagy can lead to defective erythropoiesis in vivo, as evidenced by prior studies.48,54 However, the role of autophagy in RBC maturation within EBIs remains largely uncharacterized. In cancer cell models, gene expression profiles related to autophagy have been shown to differ significantly between 2D and 3D culture environments, influenced by factors such as extracellular matrix adhesion and integrin trafficking, which regulate autophagy.55, 56, 57 This distinction is crucial, because the activation of autophagy during various stages of erythropoiesis appears to be context dependent. For example, rapamycin-mediated inhibition of mammalian target of rapamycin reduces erythroid colony formation during the commitment and proliferation phase but promotes enucleation and mitochondrial clearance by enhancing autophagy during the maturation phase.58 Furthermore, Ulk1–/– mice, which lack a key autophagy-initiating kinase, display elevated Rtic counts in peripheral blood, indicating impaired mitochondrial and ribosomal clearance and a diminished ability to mature into erythrocytes.59 Collectively, these findings emphasize the need for precise temporal and environmental control of autophagy activation to ensure the orderly progression of erythropoiesis. In our study, we observed increased autophagosome formation and the presence of MVBs in the cytoplasm of erythroblasts, with autophagy markers LC3 and p62 predominantly localized in larger erythroblasts. In contrast, Rtics and small, enucleated RBCs showed minimal autophagy activity, reflecting their near-complete loss of organelles. Pharmacological inhibition of autophagy disrupted EBI formation, leading to impaired RBC maturation, with cells arrested at the erythroblast stage and unable to undergo the final morphological changes required for full maturation. These findings highlight the essential role of autophagy in facilitating RBC maturation and enucleation in an ex vivo environment. By replicating the physiological attributes of the BM niche, our silk-based scaffold promotes autophagy and enhances ex vivo RBC production (Figure 7). In conclusion, our study demonstrates that this physiologically relevant tissue model effectively supports human erythropoiesis and highlights the potential of tailored 3D systems to enhance the study and understanding of hematopoietic processes.

Figure 7.

Schematic representation of mechanisms of RBC production into the silk bone marrow model. The 3D bone marrow model consists of a silk-based spongy scaffold with interconnected pores, resembling the microcirculation of the native tissue. This design facilitates perfusion into customized flow chambers. The scaffold is functionalized with fibronectin, promoting cell adhesion during maturation. Hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells from human adults, along with macrophages, are cocultured in the presence of erythropoietin and transferrin to establish erythropoietic niches that support RBC differentiation. During maturation, erythroblasts activate autophagy, facilitating cell membrane remodeling and organelle loss. Reduced expression of surface integrins toward the end of maturation enables easy recovery of enucleated RBCs into the medium flow, simulating bloodstream circulation. Samples can be efficiently collected in transfusion bags for downstream analysis. Figure generated with BioRender.com.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Centro Grandi Strumenti of the University of Pavia; Amanda Oldani, Patrizia Vaghi, and Alberto Azzalin for technical assistance with confocal microscopy and flow cytometry; Alessandro Malara for technical assistance with bone marrow mouse biopsy preparation; Giulia Della Rosa for technical assistance in the calculation of the Darcy coefficient; and Achille Iolascon, Immacolata Andolfo, and Roberta Russo for scientific advice and reagent supply. The graphical abstract was generated with BioRender.com.

This work was supported by Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC), Milan, Italy (investigator grant numbers 18700 and 20125, and AIRC 5x1000 project number 21267; A.B. and L.M.); European Innovation Council (EIC) Transition Project SilkPlatelet (project number 101058349; A.B.); EIC Transition Project SILKink (project number 101113073; A.B.); Cancer Research UK, Undación Científica–Asociación Española Contra el Cáncer; AIRC under the International Accelerator Award Program (project numbers C355/A26819 and 22796; L.M.); and Italian Ministry of University and Research (PRIN 2022-project number 2022P9RM9M; A.B.).

Authorship

Contribution: C.A.D.B. designed research studies, conducted experiments, acquired and analyzed data, prepared figures, and wrote the manuscript; F.C. conducted experiments, acquired and analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript; S.M. and M.L. conducted experiments, acquired the data, and edited the manuscript; S.D. analyzed bioinformatic data and edited the manuscript; V.C. conducted experiments and edited the manuscript; G.B., U.G., and D.T. acquired the data; C.D.F. and C.P. provided blood samples; M.C. provided scientific support; P.B., D.L.K., and G.M. provided scientific and technical support, analyzed the data, and edited the manuscript; L.M. provided scientific support and blood samples; and A.B. conceived the idea, supervised the project, designed research studies, analyzed the data, and wrote the manuscript.

Footnotes

RNA sequencing data sets generated in this article have been publicly deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus database (accession number GSE289025).

Additional materials and methods are described in the supplemental File. Data supporting the results of this study are available within the study. All data sets generated are available on request from the corresponding author, Alessandra Balduini (alessandra.balduini@unipv.it and alessandra.balduini@tufts.edu).

The full-text version of this article contains a data supplement.

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Di Buduo CA, Aguilar A, Soprano PM, et al. Latest culture techniques: cracking the secrets of bone marrow to mass-produce erythrocytes and platelets ex vivo. Haematologica. 2021;106(4):947–957. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2020.262485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pellegrin S, Severn CE, Toye AM. Towards manufactured red blood cells for the treatment of inherited anemia. Haematologica. 2021;106(9):2304–2311. doi: 10.3324/haematol.2020.268847. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hu J, Liu J, Xue F, et al. Isolation and functional characterization of human erythroblasts at distinct stages: implications for understanding of normal and disordered erythropoiesis in vivo. Blood. 2013;121(16):3246–3253. doi: 10.1182/blood-2013-01-476390. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kweon S, Kim S, Baek EJ. Current status of red blood cell manufacturing in 3D culture and bioreactors. Blood Res. 2023;58(S1):S46–S51. doi: 10.5045/br.2023.2023008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bayley R, Ahmed F, Glen K, McCall M, Stacey A, Thomas R. The productivity limit of manufacturing blood cell therapy in scalable stirred bioreactors. J Tissue Eng Regen Med. 2018;12(1):e368–e378. doi: 10.1002/term.2337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sivalingam J, SuE Y, Lim ZR, et al. A scalable suspension platform for generating high-density cultures of universal red blood cells from human induced pluripotent stem cells. Stem Cell Rep. 2021;16(1):182–197. doi: 10.1016/j.stemcr.2020.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Zhang Y, Wang C, Wang L, et al. Large-scale ex vivo generation of human red blood cells from cord blood CD34+ cells. Stem Cells Transl Med. 2017;6(8):1698–1709. doi: 10.1002/sctm.17-0057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ward CM, Ravid K. Matrix mechanosensation in the erythroid and megakaryocytic lineages. Cells. 2020;9(4) doi: 10.3390/cells9040894. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ivanovska IL, Shin JW, Swift J, Discher DE. Stem cell mechanobiology: diverse lessons from bone marrow. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25(9):523–532. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2015.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bessis M. Erythroblastic island, functional unity of bone marrow. Rev Hematol. 1958;13(1):8–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rhodes MM, Kopsombut P, Bondurant MC, Price JO, Koury MJ. Adherence to macrophages in erythroblastic islands enhances erythroblast proliferation and increases erythrocyte production by a different mechanism than erythropoietin. Blood. 2008;111(3):1700–1708. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-098178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Seu KG, Papoin J, Fessler R, et al. Unraveling macrophage heterogeneity in erythroblastic islands. Front Immunol. 2017;8:1140. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2017.01140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Li W, Wang Y, Zhao H, et al. Identification and transcriptome analysis of erythroblastic island macrophages. Blood. 2019;134(5):480–491. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019000430. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanspal M, Hanspal JS. The association of erythroblasts with macrophages promotes erythroid proliferation and maturation: a 30-kD heparin-binding protein is involved in this contact. Blood. 1994;84(10):3494–3504. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fabriek BO, Polfliet MM, Vloet RP, et al. The macrophage CD163 surface glycoprotein is an erythroblast adhesion receptor. Blood. 2007;109(12):5223–5229. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-08-036467. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Chow A, Huggins M, Ahmed J, et al. CD169+ macrophages provide a niche promoting erythropoiesis under homeostasis and stress. Nat Med. 2013;19(4):429–436. doi: 10.1038/nm.3057. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chasis JA, Mohandas N. Erythroblastic islands: niches for erythropoiesis. Blood. 2008;112(3):470–478. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-03-077883. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Elvarsdóttir EM, Mortera-Blanco T, Dimitriou M, et al. A three-dimensional in vitro model of erythropoiesis recapitulates erythroid failure in myelodysplastic syndromes. Leukemia. 2020;34(1):271–282. doi: 10.1038/s41375-019-0532-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kluge JA, Li AB, Kahn BT, Michaud DS, Omenetto FG, Kaplan DL. Silk-based blood stabilization for diagnostics. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113(21):5892–5897. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1602493113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Di Buduo CA, Lunghi M, Kuzmenko V, et al. Bioprinting soft 3D models of hematopoiesis using natural silk fibroin-based bioink efficiently supports platelet differentiation. Adv Sci. 2024;11(18) doi: 10.1002/advs.202308276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Omenetto FG, Kaplan DL. New opportunities for an ancient material. Science. 2010;329(5991):528–531. doi: 10.1126/science.1188936. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Di Buduo CA, Abbonante V, Tozzi L, Kaplan DL, Balduini A. Three-dimensional tissue models for studying ex vivo megakaryocytopoiesis and platelet production. Methods Mol Biol. 2018;1812:177–193. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4939-8585-2_11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Di Buduo CA, Wray LS, Tozzi L, et al. Programmable 3D silk bone marrow niche for platelet generation ex vivo and modeling of megakaryopoiesis pathologies. Blood. 2015;125(14):2254–2264. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-08-595561. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Di Buduo CA, Soprano PM, Tozzi L, et al. Modular flow chamber for engineering bone marrow architecture and function. Biomaterials. 2017;146:60–71. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tozzi L, Laurent PA, Di Buduo CA, et al. Multi-channel silk sponge mimicking bone marrow vascular niche for platelet production. Biomaterials. 2018;178:122–133. doi: 10.1016/j.biomaterials.2018.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Di Buduo CA, Soprano PM, Miguel CP, Perotti C, Del Fante C, Balduini A. A gold standard protocol for human megakaryocyte culture based on the analysis of 1,500 umbilical cord blood samples. Thromb Haemost. 2021;121(4):538–542. doi: 10.1055/s-0040-1719028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Kang TW, Kim HS, Lee BC, et al. Mica nanoparticle, STB-HO eliminates the human breast carcinoma cells by regulating the interaction of tumor with its immune microenvironment. Sci Rep. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep17515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shin TH, Kim HS, Kang TW, et al. Human umbilical cord blood-stem cells direct macrophage polarization and block inflammasome activation to alleviate rheumatoid arthritis. Cell Death Dis. 2016;7(12) doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Malara A, Gruppi C, Pallotta I, et al. Extracellular matrix structure and nano-mechanics determine megakaryocyte function. Blood. 2011;118(16):4449–4453. doi: 10.1182/blood-2011-04-345876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rockwood DN, Preda RC, Yücel T, Wang X, Lovett ML, Kaplan DL. Materials fabrication from Bombyx mori silk fibroin. Nat Protoc. 2011;6(10):1612–1631. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Takaku T, Malide D, Chen J, Calado RT, Kajigaya S, Young NS. Hematopoiesis in 3 dimensions: human and murine bone marrow architecture visualized by confocal microscopy. Blood. 2010;116(15):e41–e55. doi: 10.1182/blood-2010-02-268466. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Hernández-Barrientos D, Pelayo R, Mayani H. The hematopoietic microenvironment: a network of niches for the development of all blood cell lineages. J Leukoc Biol. 2023;114(5):404–420. doi: 10.1093/jleuko/qiad075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.de Back DZ, Kostova EB, van Kraaij M, van den Berg TK, van Bruggen R. Of macrophages and red blood cells; a complex love story. Front Physiol. 2014;5:9. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2014.00009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leimberg MJ, Prus E, Konijn AM, Fibach E. Macrophages function as a ferritin iron source for cultured human erythroid precursors. J Cell Biochem. 2008;103(4):1211–1218. doi: 10.1002/jcb.21499. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Eshghi S, Vogelezang MG, Hynes RO, Griffith LG, Lodish HF. Alpha4beta1 integrin and erythropoietin mediate temporally distinct steps in erythropoiesis: integrins in red cell development. J Cell Biol. 2007;177(5):871–880. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200702080. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sadahira Y, Yoshino T, Monobe Y. Very late activation antigen 4-vascular cell adhesion molecule 1 interaction is involved in the formation of erythroblastic islands. J Exp Med. 1995;181(1):411–415. doi: 10.1084/jem.181.1.411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Scott LM, Priestley GV, Papayannopoulou T. Deletion of alpha4 integrins from adult hematopoietic cells reveals roles in homeostasis, regeneration, and homing. Mol Cell Biol. 2003;23(24):9349–9360. doi: 10.1128/MCB.23.24.9349-9360.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Dussouchaud A, Jacob J, Secq C, et al. Transmission electron microscopy to follow ultrastructural modifications of erythroblasts upon ex vivo human erythropoiesis. Front Physiol. 2021;12 doi: 10.3389/fphys.2021.791691. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Gautier EF, Leduc M, Cochet S, et al. Absolute proteome quantification of highly purified populations of circulating reticulocytes and mature erythrocytes. Blood Adv. 2018;2(20):2646–2657. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2018023515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.An X, Schulz VP, Li J, et al. Global transcriptome analyses of human and murine terminal erythroid differentiation. Blood. 2014;123(22):3466–3477. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-01-548305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Minetti G, Bernecker C, Dorn I, et al. Membrane rearrangements in the maturation of circulating human reticulocytes. Front Physiol. 2020;11:215. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2020.00215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Minetti G, Dorn I, Köfeler H, Perotti C, Kaestner L. Insights from lipidomics into the terminal maturation of circulating human reticulocytes. Cell Death Discov. 2025;11(1):79. doi: 10.1038/s41420-025-02318-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Minetti G, Achilli C, Perotti C, Ciana A. Continuous change in membrane and membrane-skeleton organization during development from proerythroblast to senescent red blood cell. Front Physiol. 2018;9:286. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.00286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Grosso R, Fader CM, Colombo MI. Autophagy: a necessary event during erythropoiesis. Blood Rev. 2017;31(5):300–305. doi: 10.1016/j.blre.2017.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Harding C, Heuser J, Stahl P. Receptor-mediated endocytosis of transferrin and recycling of the transferrin receptor in rat reticulocytes. J Cell Biol. 1983;97(2):329–339. doi: 10.1083/jcb.97.2.329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Johnstone RM. The Jeanne Manery-Fisher memorial lecture 1991. Maturation of reticulocytes: formation of exosomes as a mechanism for shedding membrane proteins. Biochem Cell Biol. 1992;70(3-4):179–190. doi: 10.1139/o92-028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Zhang J, Wu K, Xiao X, et al. Autophagy as a regulatory component of erythropoiesis. Int J Mol Sci. 2015;16(2):4083–4094. doi: 10.3390/ijms16024083. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Beneduce E, Matte A, De Falco L, et al. Fyn kinase is a novel modulator of erythropoietin signaling and stress erythropoiesis. Am J Hematol. 2019;94(1):10–20. doi: 10.1002/ajh.25295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Petherick KJ, Conway OJ, Mpamhanga C, et al. Pharmacological inhibition of ULK1 kinase blocks mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR)-dependent autophagy. J Biol Chem. 2015;290(18):11736. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C114.627778. 11383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hamamura K, Matsuda H, Takeuchi Y, Habu S, Yagita H, Okumura K. A critical role of VLA-4 in erythropoiesis in vivo. Blood. 1996;87(6):2513–2517. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Ulyanova T, Cherone JM, Sova P, Papayannopoulou T. α4-Integrin deficiency in human CD34+ cells engenders precocious erythroid differentiation but inhibits enucleation. Exp Hematol. 2022;108:16–25. doi: 10.1016/j.exphem.2022.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Stolla MC, Reilly A, Bergantinos R, et al. ATG4A regulates human erythroid maturation and mitochondrial clearance. Blood Adv. 2022;6(12):3579–3589. doi: 10.1182/bloodadvances.2021005910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Betin VM, Singleton BK, Parsons SF, Anstee DJ, Lane JD. Autophagy facilitates organelle clearance during differentiation of human erythroblasts: evidence for a role for ATG4 paralogs during autophagosome maturation. Autophagy. 2013;9(6):881–893. doi: 10.4161/auto.24172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sylakowski K, Wells A. ECM-regulation of autophagy: the yin and the yang of autophagy during wound healing. Matrix Biol. 2021;100-101:197–206. doi: 10.1016/j.matbio.2020.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bingel C, Koeneke E, Ridinger J, et al. Three-dimensional tumor cell growth stimulates autophagic flux and recapitulates chemotherapy resistance. Cell Death Dis. 2017;8(8) doi: 10.1038/cddis.2017.398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Kenific CM, Wittmann T, Debnath J. Autophagy in adhesion and migration. J Cell Sci. 2016;129(20):3685–3693. doi: 10.1242/jcs.188490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vlahakis A, Debnath J. The interconnections between autophagy and integrin-mediated cell adhesion. J Mol Biol. 2017;429(4):515–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2016.11.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Liu Q, Luo L, Ren C, et al. The opposing roles of the mTOR signaling pathway in different phases of human umbilical cord blood-derived CD34+ cell erythropoiesis. Stem Cells. 2020;38(11):1492–1505. doi: 10.1002/stem.3268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kundu M, Lindsten T, Yang CY, et al. Ulk1 plays a critical role in the autophagic clearance of mitochondria and ribosomes during reticulocyte maturation. Blood. 2008;112(4):1493–1502. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-02-137398. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.