Abstract

Social media have become a new context for adolescent identity development. However, it is challenging to build a thorough understanding of how social media and identity development are related because studies refer to different facets of social media engagement and use diverse concepts related to identity. This review synthesizes research on the relationships between quantity and quality of social media use and different dimensions of identity development, including identity exploration and commitment, self-concept clarity, and identity distress. The search conducted across four databases yielded 4,467 records, of which 32 studies were included in the analysis, comprising 19,658 adolescents with a mean age of 16.43 years (SD = 1.81) and an age range of eight to 26 years. Active participation in social media, rather than the amount of time spent on it, was associated with more identity exploration. Authenticity on social media, not idealized self-presentation, correlated with higher self-concept clarity. Additionally, adolescents who engaged in comparisons on social media demonstrated higher levels of identity exploration and identity distress. Overall, it seems to matter more for identity development what young people do on social media than how much time they spend on it.

Keywords: Adolescents, Identity development, Self-concept, Identity distress, Social media

Introduction

Social media have become an integral part of adolescents’ daily lives who spend a significant amount of time online, often assuming dual roles as creators of self-generated content and consumers of content produced by others (Kolotouchkina et al., 2023). This engagement on social media platforms has attracted considerable research interest, including in what online activity means for identity development (e.g., Fullwood et al., 2016; Noon, 2020; Sebre & Miltuze, 2021). Unfortunately, a comprehensive understanding of existing findings on social media and its relationship to identity development is challenged by the lack of a unifying concept of social media engagement employed in research. Similarly, different identity concepts have been studied, which impedes straightforward conclusions about how engagement in social media and identity development are associated. Aiming to synthesize existing work, this study comprehensively reviews studies on the relationship between social media use and identity development by differentiating between quantity (e.g., time spent on social media) and quality (e.g., comparisons, self-presentation) of social media use, and by systematically exploring their associations with several important facets of identity development, namely commitment, exploration, self-concept clarity, and identity distress.

Adolescents form their identity through ongoing interactions between commitment and exploration. Commitments, which embody choices about one’s identity (Klimstra et al., 2010), are crucial not only for promoting identity certainty but also for fostering a coherent and stable self-concept. Self-concept clarity refers to a coherent and consistent self that is shaped by one’s committed values, beliefs, goals, and relationships and how these commitments integrate across different life domains (Schwartz et al., 2017). The alignment and stability provided by the integration of commitments are fundamental to promoting optimal adolescent development. For instance, commitments were linked to lower levels of anxiety and depression (Morsunbul et al., 2014), higher academic success (Pop et al., 2016), and self-concept clarity was associated with higher relationship satisfaction (Lewandowski Jr et al., 2010), positive self-esteem (Wu et al., 2010) and open communication with parents (Van Dijk et al., 2014). Moreover, if current commitments no longer adequately represent one’s identity, this can undermine self-concept clarity, leading to distress and potentially indicating the need for (further) identity exploration and revision (Schwartz et al., 2017).

Identity exploration involves a deep assessment of current commitments and questioning them to either revise or replace them with new ones. An analysis of current commitments is thought to be beneficial for maintaining one’s identity; whereas, reconsidering those commitments can potentially lead to identity uncertainty, which may have negative outcomes such as depressive and anxiety symptoms (Crocetti et al., 2008), lower academic achievement (Pop et al., 2016), and lower self-esteem (Crocetti et al., 2010). Furthermore, adolescents may experience identity distress, which can range from mild anxiety to severe symptoms in different life domains, such as long-term goals, friendships, and moral values, due to uncertainty about the self (Berman, 2020). Not unsurprisingly, individuals with identity distress reported higher levels of exploration (Berman et al., 2009) and lower levels of commitment (Sica et al., 2014). Identity distress has also been linked to internalizing and externalizing problems (Hernandez et al., 2006).

The process of identity development, which encompasses identity exploration and commitment and ideally results in a stable self-concept, with identity distress as the less favorable outcome, has been rooted in the relationships with family, peers, and school (Kroger, 2006), with research also largely focusing on these contexts. However, contemporary young people have expanded their social contexts through social media (Nesi et al., 2020). This expansion offers users various modes of interaction, either one-directional or multi-directional, where they can consume and create content, and receive feedback. Additionally, users can – to some extent –control and shape who has access to their content or profile. When studying effects of social media on adolescent development, researchers have primarily focused on measuring the amount of time young individuals spend on social media platforms. Time spent on social media has been linked to depression (Brunborg & Burdzovic Andreas, 2019), lower well-being (Huang, 2017), and a range of behavioral and emotional problems (Riehm et al., 2019). With respect to identity development, excessive time spent on social media was associated with low self-concept clarity (Sharif & Khanekharab, 2017) and disengagement from active identity exploration (Imperato et al., 2022). That said, findings are inconclusive and not all studies find associations between time spent on social media and identity exploration and commitment (e.g., Cyr et al., 2015; Fullwood et al., 2016). These mixed findings raise questions about the extent to which time spent on social media relates to facets of identity development and whether this conceptualization of social media engagement is sufficient.

In detail, engagement with social media comes in great diversity with feasibly differential associations with identity development but this is not captured when only time spent on social media is considered. This diversity includes various ways of self-presentation and seeking feedback on one’s presented persona, discussing concrete topics or sharing everyday issues, but also comparing abilities and opinions. Associations between forms – or quality – of engagement and facets of identity development have been studied and have shown, for instance, that individuals who compare their abilities on social media have lower self-concept clarity (Yang et al., 2018a) and higher identity distress (Yang et al., 2020) whereas editing profiles, sharing posts or blogs (Livingstone, 2008), and presenting oneself in different ways (Chittenden, 2010) or as someone else (Schmitt et al., 2008) are all indicative of identity exploration.

To date, no systematic review has addressed how different forms of social media engagement relate to adolescent identity development. Previous reviews suggested that social media enable identity exploration and various ways of self-presentation among adolescents (Shapiro & Margolin, 2014; Wängqvist & Frisén, 2016). However, these reviews addressed not only social media and personal identity development but also included other online contexts and group identities, which differs from the exclusive focus on social media and identity development in our current review. Finally, a recent systematic review examined the link between social media use and identity development (Senekal et al., 2023). Nonetheless, their conclusions might not fully capture this relationship, partly due to the broad approach in covering various concepts related to social media use (e.g., cyberbullying, online communication) and identity development (e.g., body image, self-esteem, self-concept clarity, and identity processing style).

Current Study

Young people’s engagement on social media has quantitative and qualitative dimensions that are both associated with facets of identity development in different ways. However, this distinction has not been systematically applied in previous work. To overcome this limitation and to allow for a systematic understanding of how social media and identity development - both of crucial relevance for adolescent development - are related and what gaps in knowledge prevent comprehensive understanding, a synthesis of existing research is urgently needed. To this end, this systematic review of original qualitative and quantitative studies on adolescents’ social media engagement differentiates between quantity, that is time spent on special media and quality, that is, what young people do on social media, and identity development, including commitment and exploration, and its associated constructs self-concept and identity distress.

Method

Search Strategy

This review adhered to the updated reporting guidelines established by the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis (Page et al., 2021). The search was conducted in November 2022 on ERIC, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, and SocINDEX using the following terms: (identity) AND (“digital media” or internet or “social media” OR “social network” OR TikTok OR Snapchat OR Facebook OR YouTube OR weblog OR blog OR vlog OR Myspace OR Weibo OR Douyin OR QQ OR Kuashou OR Reddit OR Quora OR Instagram) AND (“young people” OR adolesc* OR teenagers OR “young adults” OR teen or youth OR student). Concrete platform names were selected based on their global popularity (Statista, 2022). Platforms that previously functioned as social media were also used as search terms to ensure that relevant studies published earlier were not overlooked. The search encompassed titles, abstracts, and keywords of articles. The search results were imported into Zotero to remove duplicate items, book chapters, dissertations, and conference studies. Subsequently, title and abstract screening were performed using Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., 2016).

Eligibility Criteria

Studies were included if they fulfilled the following criteria: (1) pertained to adolescents with a mean age between nine and 19 years, or those with an age range from nine to 19; (2) assessed exploration and commitment, self-concept clarity, and identity distress as correlates of social media; (3) original research was qualitative or quantitative; (4) were published in a peer-reviewed journal; and (5) were in English.

Studies were excluded if they did not meet the inclusion criteria, including those in which: (1) participants were recruited based on a clinical diagnosis (e.g., depression, diabetes); (2) studies examined platforms initially developed purely as messenger services such as WhatsApp, Telegram, and WeChat; (3) studies assessed general internet use or utilization of any communication devices such as mobile phones, tablets, or computers; (4) studies examined online gambling, addiction, purchases, or learning; and (5) studies focused on social identities (e.g., sexual, religious, ethnic, gender, civic, national, or professional identities) instead of aspects of identity development, including commitment and exploration, self-concept clarity, and identity distress.

Quality Assessment

The quality of eligible studies was assessed via assessment tools for qualitative and quantitative research. The National Institutes of Health Quality Assessment Tool for Observational Cohort and Cross-Sectional Studies was modified and used to evaluate the quality of quantitative studies. (NIH 2014). Specifically, our assessment included items related to study design, study population, sample size, independent and dependent variables, and follow-up rate. Other items were excluded because our systematic review did not include cohort studies. As a result, a quantitative study could receive a maximum score of six (best quality). The Critical Appraisal Skills Programme Qualitative Studies Checklist was used to assess the quality of qualitative studies (CASP 2018). Although the tool consists of ten items, two items concerning ethical issues and the value of the research were excluded, as these aspects were not considered when assessing the quality of the quantitative studies. Therefore, a qualitative study could receive a maximum score of eight (best quality).

Results

Data Extraction

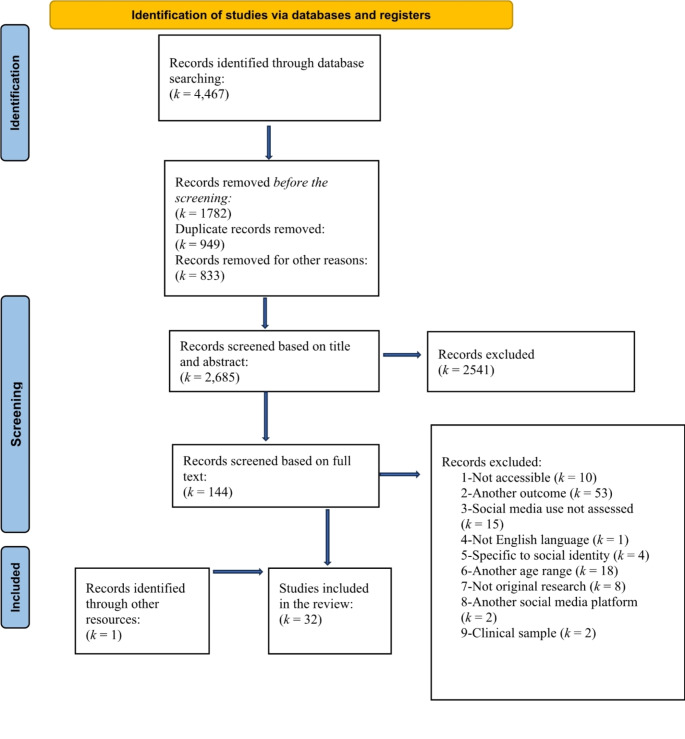

The search generated k = 4,467 hits, all of which were loaded into Zotero. Duplicate items and non-peer-reviewed studies such as book chapters, dissertations, and conference studies were removed in Zotero, resulting in k = 2,685 for title and abstract screening. Following this, titles and abstracts were screened using Rayyan (Ouzzani et al., 2016), which resulted in k = 144 studies that remained for full-text screening.

To ensure reliability, the second author screened 20% of randomly selected abstracts and titles, resulting in an 84% overlap with the first author’s selections. When authors disagreed, studies were discussed until consensus was reached. One study was identified through a reference cited in another study that was included for full-text screening. Ultimately, data were extracted from k = 32 out of k = 145 studies (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA flow diagram showing the process of study selection for inclusion in the systematic review

Sample Characteristics

This review encompasses both qualitative k = 12 and quantitative k = 20 studies. The overall sample is N = 19,658 adolescents with a mean age of 16.43 years (SD = 1.81), ranging from eight to 26 years. The primary age range was set at nine to 19 years, but some studies included participants outside this range. However, the mean age in these studies was neither smaller than nine nor bigger than 19. The overall calculated mean age of 16.43 years (SD = 1.81) comes from studies that reported only the mean age of their participants.

The majority of studies were conducted in the US (k = 9), followed by the UK (k = 5), Singapore (k = 3), China (k = 2), Australia (k = 1), Malaysia (k = 1), Canada (k = 1), Ireland (k = 1), Malta (k = 1), Italy (k = 1), and Bermuda (k = 1). Four studies gathered data from multiple countries, and two studies did not report the country in which the studies were conducted (Guzzetti & Gamboa, 2005; Pelling & White, 2009).

Summary of Included Studies

Details about sample sizes, measures of social media and identity development, design and analytic procedure of the studies are presented in the table (see Tables 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6). The studies examined engagement on Facebook (k = 4), personal blogs/weblogs (k = 2), Instagram (k = 2), online journals (k = 1), Myspace (k = 1), and Ask.fm (k = 1). Thirteen studies did not name any social media platforms, eight included multiple platforms.

Table 1.

Studies on identity commitment (k = 4)

| Study | Country | Sample SiSSize |

Sample Characteristics | Design | Method | Social Media Platforms | Social Media Measure | Identity Measure | Analysis Procedure and Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyr et al. (2015) | USA | N = 268 |

Mean age = 16.21 69% Female |

CS | Pen and paper survey | Not specified | Technology Usage Scale (Cyr et al., 2015), developed for study purpose of study. | Ego Identity Process Questionnaire (Balistreri et al., 1995) | Correlation analysis revealed no significant association. |

| Imperato et al. (2022) | Italy | N = 354 |

Mean age = 16.18 SD = 1.58 80% Female |

CS | Pen and paper survey | Not specified | Internet Addiction (Ferraro et al., 2007), adapted for purpose of study, and adolescents’ self-reports on time spent on social media. | Utrecht Management of Identity Commitments Scale (Crocetti et al., 2010) | Correlation analysis revealed that both of the two tested associations were significantly negative. |

| Noon (2020) | UK | N = 177 |

Mean age = 15.45 SD = 1.67 55% Female |

CS | Pen and paper survey |

Social Media Social Comparison Scale (Yang et al., 2018a) |

Utrecht Management of Identity Commitments Scale (Crocetti et al., 2010) | Multivariate multiple regression revealed one of the two tested associations was significantly positive. | |

| Noon et al. (2021) |

Romania and Serbia |

N = 1085 |

Mean age = 18.87 SD = 2.57 78% Female |

CS |

Not reported |

Social Media Social Comparison Scale (Yang et al., 2018a) |

Utrecht Management of Identity Commitments Scale (Crocetti et al., 2010) |

Hierarchical regression analysis revealed that one of the two tested associations was significantly positive. |

Abbreviations: CS: cross-sectional

Table 2.

Quantitative studies on exploration (k = 6)

| Study | Country | Sample Size Sie |

Sample Characteristics | Design | Method | Social Media Platforms | Social Media Measure | Identity Measure | Analysis Procedure and Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyr et al. (2015) | USA | N = 268 |

Mean age = 16.21 69% Female |

CS | Pen and paper survey | Not specified | Technology Usage Scale (Cyr et al., 2015), developed for study. |

Ego Identity Process Questionnaire (Balistreri et al., 1995) |

Correlation analyses revealed no significant associations. |

| Imperato et al. (2022) | Italy | N = 354 |

Mean age = 16.18 SD = 1.58 80% Female |

CS | Pen and paper survey | Not specified |

Internet Addiction Test (Ferraro et al., 2007), adapted for purpose of study, and adolescents’ self-reports on time spent on social media. |

Utrecht Management of Identity Commitments Scale (Crocetti et al., 2010) |

Correlation analyses revealed that one of the four tested associations was significantly negative, while the other was significantly positive. |

| Manzi et al. (2018) | Italy and Chile | N = 712 |

Mean age = 16.40 SD = 2.03 52% Female |

CS | Pen and paper survey | Facebook use was measured by two items. | Identity exploration was measured by two items. | Correlation analysis indicated that six of the eight tested associations were significantly positive. | |

| Noon (2020) | UK | N = 177 |

Mean age = 15.45 SD = 1.67 55% Female |

CS | Pen and paper survey | Social Media Social Comparison Scale (Yang et al., 2018a) |

Utrecht Management of Identity Commitments Scale (Crocetti et al., 2010) |

Multivariate multiple regression revealed that three of the four tested associations were significantly positive. | |

| Noon et al. (2021) | Romania and Serbia | N = 1085 |

Mean age = 18.87 SD = 2.57 78% Female |

CS |

Not reported |

Social Media Social Comparison Scale (Yang et al., 2018a) |

Utrecht Management Of Identity Commitments Scale (Crocetti et al., 2010) |

Hierarchical regression analysis revealed that three of the four tested associations were significantly positive. | |

| Schmitt et al. (2008) | USA | N = 500 | Aged 8–17 | CS | Phone interview |

Personal homepages and blogs |

A survey questionery on technology use. | A survey questionery about self presentation and online interaction. | ANOVA revealed that young people who created homepages were more likely to pretend to be someone other than they were, compared to those who did not create homepages. |

Abbreviations: CS: cross-sectional

Table 3.

Qualitative studies on identity exploration (k = 6)

| Study | Country | Sample Size |

Sample Characteristics | Method | Social Media Platforms | Analysis Procedure and Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chittenden (2010) |

USA, Canada, New Zealand |

N = 10 |

Aged 14–18 100% Female |

Open- ended questions asked via email, |

Fashion blogs |

Qualitative data analysis revealed that fashion blogs allow adolescents to present themselves by playing different looks and styles as part of their identity exploration. |

| Farrugia et al. (2019) | Malta | N = 22 |

Aged 11–16 45.45% Female |

Focus group discussion and interviews |

Ask.fm | Thematic analysis revealed that adolescents engage in self-presentation on Ask.fm by answering questions and reflecting on feedback, which helps them explore their identities. |

| Greenhow and Robelia (2009) | USA | N = 11 |

Aged 17–19 72.73% Female |

Semi-structured interview, Think aloud, Content analysis, |

MySpace | The thematic analysis revealed that MySpace was a platform for young people to try out different roles and play with their profile looks as part of their identity exploration. |

| Kennedy and Lynch (2016) | Ireland | N = 16 |

Aged 9–16 69% Female |

Focus group interview |

Not specified |

Thematic analyses revealed that adolescents presented themselves by creating fake ages or avatars and presenting their edited versions to explore their identities. |

| Lichy et al. (2022) | UK | N = 16 |

Aged 8–12 50% Male |

Interview |

Not specified |

The data were analysed using axial coding. Social media platforms provide an environment for presenting oneself as someone else, facilitating identity exploration. |

| Livingstone (2008) | UK | N = 16 |

Aged 13–16 50% Female |

Open ended individual interviews |

MySpace, Facebook, Bebo, Piczo |

Thematic analyses revealed that social media helps individuals explore their identity by providing flexibility to revise and edit their profiles. |

| Mazur and Kozarian (2010) | USA | Not applicable | 124 blogs were examined, each of which was owned by individuals aged between 15 and 19 | Content analyses |

LiveJournal, DeadJournal, Xanga, Open Diary, Myspace, Friendster |

Data were analyzed by thematic analysis. Blog entries reflected confusion of the authors about themselves, which was 7% in all entiries. Blogs were a place where adolescents explored who they were and who they wanted to become. |

Table 4.

Quantitative studies on self-concept clarity (k = 12)

| Study | Country | Sample SiSSize |

Sample Characteristics | Design | Method | Social Media Platforms | Social Media Measure | Identity Measure | Analysis Procedure and Findings |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Davis (2013) | Bermuda | N = 2079 |

Mean age = 15.4 57% Female |

CS | Pen and paper, digital survey |

Youtube |

Digital media use scales (e.g., Courtois et al., 2009; Leung, 2007), adapted for purpose of study. | Self-Concept Clarity Scale (Campbell et al., 1996) | Structural equation model indicated that one tested association was significantly negative. | |

| Fullwood et al. (2016) | UK | N = 148 |

Mean age = 15.50 SD = 1.87 61% Femaale |

CS |

Pen and paper survey |

Intensity Scale (Ellison et al., 2007) Online Self Scale (Fullwood et al., 2016) developed for purpose of study. |

Self-Concept Clarity Scale (Campbell et al., 1996) | Correlation analysis of five tested associations indicated no association for two, two were significantly negative, and one was significantly positive. | ||

| Ho et al. (2017) | Singapore | N = 4920 |

Mean age = 14.41 SD = 2.72 57% Female |

CS |

Pen and paper survey |

Not specified | Excessive Social Media Use Scale (Caplan, 2010), adapted for purpose of study. | Self Identity Scale (Callero, 1985), adapted for purpose of study. | Hierarchical regression analysis revealed one tested association was significantly positive. | |

| Lee et al. (2017) | Singapore | N = 4920 |

Mean age = 14.73 51% Female |

CS |

Pen and paper survey |

Not specified |

SNS Habit Strength Scale (Larose et al., 2003), adapted for purpose of study. |

Self Identity Scale (Callero, 1985), adapted for purpose of study. |

Covariance structure model revealed that one tested association was significantly positive. | |

| Pelling & White (2009) | Not reported | N = 233 |

Mean age = 19.22 SD = 2.03 64% Female |

CS | Both online and pen and pencil survey | Not specified | Self-report of participants on how often they visit social networking sites. | Self Identity Scale (Terry et al., 1999), adapted for purpose of study. | Hierarchical regression analysis indicated that one tested association was significantly positive. | |

| Sharif & Khanekharab (2017) | Malaysia | N = 501 |

Mean age = 19.68 SD = 1.65 56% Female |

CS | Online survey | Not specified |

Excessive SNS Usage Scale (Mueller et al., 2011), adapted for purpose of study. |

Self-Concept Clarity Scale (Campbell et al., 1996) | The structural equation model revealed that one tested association was significantly positive. | |

| Yang and Brown (2016) | USA | N = 218 |

Mean age = 18.07 SD = 0.33 64% Female |

L | Online survey |

Audience Supportive Feedback Scale (Yang & Brown, 2016) developed for purpose of study. |

Self-Concept Clarity Scale (Campbell et al., 1996) | Path analysis revealed no significant associations. | ||

| Yang et al. (2017) | USA | N = 219 |

Mean Age = 18.29 SD = 0.75 74% Female |

CS | Online survey |

Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, Facebook, Other |

Facebook self-presentation scale (Yang & Brown, 2016), adapted for purpose of study. |

Erikson Psychosocial Stage Inventory (Rosenthal et al., 1981) |

Correlation analysis of the four tested associations indicated no association for one, one was significantly negative and two were significantly positive. | |

| Yang et al. (2018a) | USA | N = 219 |

Mean age = 18.29 SD = 0.75 74% Female |

L | Online survey |

Instagram, Twitter, Snapchat, Facebook, Other |

Social Media Social Comparison Scale (Yang et al., 2018a), adapted for purpose of study. |

Erikson Psychosocial Stage Inventory (Rosenthal et al.1981) |

Correlation analysis indicated five of eight tested associations were significantly negative. | |

| Yu and Shek (2021) | China | N = 1896 |

Mage = 13.19 52% Male |

CS | Pen and paper survey | Not specified |

Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale (e.g., Andreassen et al., 2017; Lin et al., 2017), adapted for purpose of study. |

Chinese Positive Youth Development Scale (Shek et al., 2007) |

Correlation analysis indicated that one tested association was significantly negative. | |

| Wang et al. (2021) | China | N = 473 |

Mean age = 14.63 SD = 1.57 61% Male |

CS | Pen and paper survey | Not specified | Adolescents’ Mobile Social Media Usage Behaviour Scale (Wang & Lei 2015), adapted for purpose of study. |

Self-Identity Scale (Tan et al., 1977) |

Correlation analysis indicated one tested association was significantly positive. | |

| Zheng et al. (2011) | Singapore | N = 101 |

Mean age = 14.77 SD = 1.47 73% Female |

CS | Online survey |

MysSpace Other |

Demographic Information Questionnaire | Adolescent Online Social Communication Questionnaire | Hierarchical regression analysis revealed no association. | |

Abbreviations: CS: cross-sectional; L: longitudinal

Table 5.

Qualitative studies on self-concept clarity (k = 6)

| Study | Country | Sample Size |

Sample Characteristics | Method | Social Media Platforms | Analysis Procedure and Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bell (2019) | UK | N = 35 |

Aged 13–17 60% Female |

Semi-structured interview and focus group discussion |

Not specified | Data were analyzed by thematic analysis. The amount of likes that adolescents received on their social media content as a way of self-presentation reinforced their self-concept. |

| Guzzetti & Gamboa, 2005 | Not reported | N = 2 |

Age not reported/ adolescents 100% Female |

Semi-structured interview, observations, and open-ended response questionnaire |

Live Journal | Data were analyzed using constant comparison. Online journaling, with features like immediate feedback and shared reflections, can reciprocally shape and reinforce one’s self-concept. |

| Pangrazio (2019) | Australia | N = 13 | Aged 15–19 | Interviews, online questionnaire, online observations, and group discussions on workshops | Data were analyzed through thematic analysis. Facebook is a place where adolescents present themselves; however, when they present their edited versions, it creates confusion about who they are and who they present. | |

| Richardson (2016) | Canada | N = 150 | Not reported/ adolescents |

Online Survey Focus Group Study, Interview |

Not specified | Data were analysed by thematic analysis. Presenting their true self on social media reinforced adolescents’ self-concepts, while false presentation created confusion. |

| Schmitt et al. (2008) | USA | Not applicable | 48 blogs were examined, each of which was owned by individuals aged between 8 and 17 |

Qualitative content analyses |

Personal homepages and Blogs | Data were analysed by thematic analysis. The home page is a space where adolescents present and express themselves, which facilitates their self-concept. |

| Subrahmanyam et al. (2009) |

US, Canada, Australia, UK, Singapore, Brunei, Indonesia, Malaysia, New Zealand, |

Not applicable | 195 blogs were examined, each of which was owned by individuals aged between 14 and 18 |

Qualitative content analyses |

Xanga, LiveJournal, Blog-City, Blog Drive, Journal Space, Blogsearchengine.com, Blurty, DeadJournal, Open Diary |

Data were analysed by thematic analysis. Only 10% of the entries addressed teenagers’ self-concept. Blogs can help reinforce an individual’s self-concept by allowing them to present themselves in the blogosphere and receive feedback. |

Table 6.

Studies on identity distress (k = 3)

| Study | Country | Sample Size Siz |

Sample Characteristics | Design | Method | Social Media Platforms | Social Media Measure | Identity Measure | Analysis Procedure and Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cyr et al. (2015) | USA | N = 268 |

Mean age = 16.21 69% Female |

CS |

Pen and paper survey |

Social networking sites |

Technology Usage Scale (Cyr et al., 2015b), developed for study purpose of study. |

Identity Distress Survey (Berman et al., 2004) |

Correlation analysis indicated one tested association was significantly negative. |

| Yang et al. (2018b) | USA | N = 219 |

Mean age = 18.29 SD = 0.75 74% Female |

L |

Online survey |

Snapchat Other |

Social Media Social Comparison Scale (Yang et al., 2018a) |

Identity Distress Survey (Berman et al., 2004) |

Correlation analysis indicated two of the four tested associations were significantly positive. |

| Yang et al. (2020) | USA | N = 219 |

Mean Age = 18.29 SD = 0.75 74% Female |

L | Not reported |

Not specified |

Social Media Social Comparison Scale (Yang et al., 2018a) |

Identity Distress Survey (Berman et al., 2004) |

Correlation analysis revealed one of the three tested associations was significantly positive. |

Abbreviations: CS: cross-sectional; L: longitudinal

Studies examined the link between social media engagement quantity (i.e., how much time someone had spent on social media), commitment (k = 2), exploration (k = 2), self-concept clarity (k = 6), and identity distress (k = 2). Associations between social media engagement quality (i.e., what adolescents do on social media), and aspects of identity development were also assessed, concerning commitment (k = 2), exploration (k = 10), self-concept clarity (k = 13), and identity distress (k = 1).

Studies employed various instruments, including newly developed or modified scales, to measure time spent on social media. Further, adolescents were asked to self-report the amount of time they spent on social media platforms. To assess social comparison on social media as a form of engagement, all studies employed the Social Media Social Comparison Scale (Yang et al., 2018a) (k = 5). Self-presentation strategies and receiving feedback on social media were measured using various methods in quantitative studies and through interviews, content analysis, and focus group discussions.

Regarding outcomes, commitment and exploration were measured by the Ego Identity Process Questionnaire in one study (Balistreri et al., 1995), but the most frequently used scale was the Utrecht Management of Identity Commitments Scale (Crocetti et al., 2010) (k = 3). Self-concept clarity was assessed by various instruments, with the most used being the Self-Concept Clarity Scale (Campbell et al., 1996) (k = 4). All studies that measured identity distress used the Identity Distress Survey (Berman et al., 2004) (k = 3).

Quality Assessment

Regarding the quality assessment of quantitative studies, none received a score on the item concerning the follow-up rate as the majority of the studies were cross-sectional, and the longitudinal studies had a loss to follow-up rate higher than 20%; thus, none achieved the maximum score of six. Only one study justified its sample size (Davis, 2013); hence, the remaining studies did not receive points on this item. All studies provided their sample information and formulated a research question. Three studies defined identity development as a part of being a social media user (Ho et al., 2017; Lee et al., 2017; Pelling & White, 2009), which might bias the findings by over-attributing identity development to social media use. Additionally, while one study did not clearly define identity development (Schmitt et al., 2008), two studies did not explicitly conceptualize social media use (Pelling & White, 2009; Schmitt et al., 2008). Despite the limitations of included studies, the overall quality was considered satisfactory (see Table 7).

Table 7.

Quality assessment of included quantitative studies using the national institutes of health quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies

| Study | Was the objective clearly or research question clearly stated? | Was the study population clearly specified and defined? | Was sample size justification, power description, or variance and effect estimate provided? | Were the social media variables clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? | Were identity development variables clearly defined, valid, reliable, and implemented consistently across all study participants? | Was loss to follow-up after baseline 20% or less? | Quality rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Cyr et al., 2015) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| (Davis, 2013) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 5 |

| (Fullwood et al., 2016) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| (Ho et al., 2017) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| (Imperato et al., 2022) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| (Lee et al., 2017) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| (Manzi et al., 2018) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| (Noon, 2020) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| (Noon et al., 2021) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| (Pelling & White, 2009) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| (Schmitt et al., 2008) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| (Sharif & Khanekharab, 2017) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| (Wang et al., 2021) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| (Yang & Brown, 2016) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| (Yang et al., 2017) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| (Yang et al., 2018a) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| (Yang et al., 2018b) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| (Yang et al., 2020) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| (Yu & Shek, 2021) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| (Zheng et al., 2011) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

None of the qualitative studies received a score of eight, for different reasons, such as lack of rigorous data analysis, reporting of appropriateness of research design, and the relationship between researcher and participants. All studies explained the appropriateness of their qualitative research methodology and recruitment strategies, whereas one study failed to detail its recruitment approach (Richardson, 2016). Two studies did not clearly articulate their research questions (Lichy et al., 2022; Richardson, 2016). The majority of the studies did not address the relationship between researchers and participants, except for two (Chittenden, 2010; Guzzetti & Gamboa, 2005). While the majority provided depth description of data analysis process, three did not (Chittenden, 2010; Lichy et al., 2022; Livingstone, 2008). Only six studies explicitly stated their results. Notwithstanding the limitations of the studies, the overall quality was deemed satisfactory (see Table 8).

Table 8.

Quality assessment of included quantitative studies using the critical appraisal skills programme qualitative studies checklist

| Study | Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | Was the research design appropriate to address the aim of the research? | Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to aims of the research? | Was the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | Is there a clear statement of findings? | Quality Rating |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Bell, 2019) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| (Chittenden, 2010) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 5 |

| (Farrugia et al., 2019) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| (Greenhow & Robelia, 2009) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| (Guzzetti & Gamboa, 2005) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 7 |

| (Kennedy & Lynch, 2016) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 6 |

| (Lichy et al., 2022) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| (Livingstone, 2008) | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 5 |

| (Mazur & Kozarian, 2010) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| (Pangrazio, 2019) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 7 |

| (Richardson, 2016) | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| (Schmitt et al., 2008) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

| (Subrahmanyam et al., 2009) | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 6 |

Social Media Use and Commitment

Two studies examined the association between time spent on social media and identity commitment, with mixed findings. One study revealed no significant association between time spent on social media and commitment (Cyr et al., 2015), while another study indicated that adolescents who spent excessive or normal amount of time on social media tended to quit their commitments (Imperato et al., 2022).

Two studies focused on comparisons on social media and identity commitments. While one study reported that adolescents who compared their abilities were more certain about themselves (Noon, 2020), another study indicated that those who compared opinions were more confident about who they were (Noon et al., 2021). The age differences between these two studies could explain this variance; the first study involved younger adolescents, while the second included older adolescents. This suggests that while younger adolescents may present themselves as capable, older adolescents may present themselves as knowledgeable. Nevertheless, a general conclusion on the link between the comparison of abilities and opinions on social media and identity commitment cannot be drawn due to the cross-sectional nature of the research and the limited number of studies.

Social Media Use and Exploration

Two studies investigated the link between time spent on social media and identity exploration, yielding mixed outcomes that precluded a conclusive finding. While one study found no association between time spent on social media and exploration (Cyr et al., 2015), another study reported that individuals who spent excessive amounts of time on social media were more likely to have identity uncertainty (Imperato et al., 2022).

Six studies examined the relationship between different ways of self-presentation and identity exploration. Studies suggested that adolescents presenting themselves by playing with different looks (Chittenden, 2010), testing different roles (Greenhow & Robelia, 2009) and answering questions about who they were (Farrugia et al., 2019), and pretending to be someone else (Kennedy & Lynch, 2016; Lichy et al., 2022; Schmitt et al., 2008) tended to explore their identities. Four studies suggested that adolescents who edited their profiles, shared posts or content, and created blog entries were more likely to engage in identity exploration (Greenhow & Robelia, 2009; Livingstone, 2008; Manzi et al., 2018; Mazur & Kozarian, 2010). In summary, social media use seems to be important for identity exploration among those who actively participate.

Two studies examined the relationship between the comparison of abilities and opinions and exploration. One study showed that adolescents who compared their abilities were more likely to analyze and reconsider those abilities (Noon, 2020), while another study found that those who compared their opinions analyzed and questioned those opinions (Noon et al., 2021). In summary, ability and opinion comparison may be associated with identity confusion, which is also beneficial for engaging in further exploration and making new commitments. Unfortunately, due to the cross-sectional nature of the research and the small number of studies, it is difficult to reach a broad conclusion on this relationship.

Social Media Use and Self-Concept Clarity

Six studies addressed time spent on social media and self-concept clarity, with mixed results. Two studies found no significant correlation between time spent on social media and self-concept clarity (Fullwood et al., 2016; Zheng et al., 2011). In contrast, two studies indicated that adolescents who used social media excessively had an unclear self-concept (Sharif & Khanekharab, 2017; Yu & Shek, 2021). Two studies found that those who spent excessive time on social media had a clear self-concept (Ho et al., 2017; Pelling & White, 2009). Given the mixed results, it is difficult to draw definitive conclusions about the relationship between time spent on social media and self-concept clarity.

A short-term longitudinal study examined the correlation between comparison on social media and self-concept clarity, showing that individuals who compared their abilities tended to feel unclear about themselves, as evidenced by both longitudinal and cross-sectional associations. There was a negative relationship between opinion comparison and self-concept clarity when measures were taken approximately five months after the initial assessment (Yang et al., 2018a). This suggests that both forms of comparison are related to unclear self-concepts, with opinion comparisons possibly occurring after ability comparisons. It is difficult to make a general statement about this relationship as the number of studies is limited.

Four studies showed that adolescents who presented their true selves in a way that matched their in-person version had a clear self-concept (Fullwood et al., 2016; Richardson, 2016; Schmitt et al., 2008; Yang et al., 2017). In contrast, those who presented an idealized self that was inconsistent with their offline persona were less clear about how they felt about themselves (Davis, 2013; Fullwood et al., 2016; Pangrazio, 2019; Richardson, 2016; Yang et al., 2017). The evidence indicates that when individuals present themselves in a manner that aligns with their authentic selves, it fosters self-concept clarity.

Two studies showed that adolescents who regularly used social media, shared content, and engaged in recreational behaviors were more likely to be sure who they were (Lee et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2021). Four studies focused on the relationship between getting feedback on social media and self-concept clarity, yielding mixed results. Three qualitative studies found that those who got feedback from their audience reinforced their self-concept clarity (Bell, 2019; Guzzetti & Gamboa, 2005; Subrahmanyam et al., 2009). Nevertheless, one short-term longitudinal study did not reveal a significant correlation between getting feedback on social media and self-concept clarity ( Yang & Brown, 2016).

Social Media Use and Identity Distress

Three studies examined the link between social media use and identity distress. One study found that people who spent time on social media had identity-related distress (Cyr et al., 2015), whereas another study did not reveal any significant relationship, either cross-sectional or longitudinal, between excessive use of social media and identity distress (Yang et al., 2020). Only one short-term longitudinal study reported a cross-sectional association; people who compared their abilities were likely to experience identity distress (Yang et al., 2018b). Consequently, establishing a definitive relationship between time spent on social media and identity distress is difficult due to mixed results. Nevertheless, ability comparison may be a potential correlate of identity distress.

Discussion

Social media have become an indispensable part of adolescents’ lives, and the relationship between social media engagement and adolescent development, including identity development, has been the focus of many studies. However, a comprehensive understanding of the interplay between social media and identity development is challenging due to heterogeneity in conceptualizing and assessing social media use and the different facets of identity development. Therefore, the empirical literature was reviewed to identify whether systematic associations between aspects of social media engagement and identity development can be derived, with a specific focus on associations between the quantity and quality of social media engagement and components of identity development, including commitment and exploration, self-concept clarity, and identity distress.

Overall, our synthesis of the research suggests that it is not the amount of time spent on social media that is critical, but rather the activities undertaken during this time that seem to play a role for aspects of identity development. Our findings are in line with findings that appearance comparison on social media was associated with body dissatisfaction (Fioravanti et al., 2022), and particular types of engagement, such as comparisons, active or passive use, were associated with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and psychological distress (Keles et al., 2020), where actual activities were more salient than the amount of time spent engaging in social media. For example, an adolescent interested in science might reinforce their identity by watching videos about chemistry on platforms such as YouTube. Such passive engagement in consuming content is simultaneously an active process of identity exploration and reinforcement for the individual, or vice versa. Simply quantifying screen time or time spent on social media does not adequately capture the nuances of social media use. By understanding what users are doing on these platforms, deeper insights into how social media use relates to facets of identity development are possible.

Our findings also suggest that self-presentation strategies are common among adolescents on social media. These strategies include playing with appearance to present an ideal self, impersonating others, and creating fictitious profiles, all of which can be part of one’s identity exploration (Chittenden, 2010; Greenhow & Robelia, 2009; Kennedy & Lynch, 2016; Schmitt et al., 2008) That said, taking up different identities in social media contexts might also hinder achieving self-concept clarity. That is, adolescents who present a fictitious version of themselves that differs from their authentic self tend to have lower self-concept clarity (Davis, 2013; Fullwood et al., 2016; Pangrazio, 2019; Richardson, 2016; Yang et al., 2017). In contrast, adolescents who present their true selves on social media tend to have a clear self-concept (Fullwood et al., 2016; Schmitt et al., 2008; Richardson, 2016; Yang et al., 2017), suggesting stronger commitments. As conclusions about a direction of effects cannot be drawn, it might also be the case that those with clearer self-concept are more confident to be who they actually are on social media. To fully understand adolescents’ self-presentation strategies on social media and their relation to identity development, it would be informative to examine adolescents’ motives for social media use because the reasons why one engages in fictitious self-presentation might vary. Adolescents may create alternate profiles in which they pretend to be older to overcome age restrictions, to bully without being recognized in the real world, or simply for amusement. In other words, presenting oneself in a manipulated way on social media may go beyond mere identity exploration, while presenting one’s true self is an indication of strong commitments.

Research on the relationship between comparing abilities and opinions on social media and aspects of identity development is limited, and our review includes only a few studies, suggesting some possible age effects. Younger adolescents who compared their abilities tended to re-evaluate their identity commitments in order to make new commitments or strengthen existing ones (Noon, 2020). Older adolescents experienced this when they compared their opinions (Noon et al., 2021). In other words, younger adolescents were more likely to present themselves by their abilities, while older adolescents tended to define themselves through their opinions on social media. However, firm temporal conclusions cannot be drawn due to the cross-sectional nature of these studies, which prevents observing changes over time.

A few limitations were encountered while conducting this review. Considering the field of identity development, most of the research has focused on a single aspect of identity development in the context of social media. For example, while many of the studies included in this review focus on exploration (k = 12), only few studies focus on commitment (k = 4). Given this narrow focus of current research, it remains unclear whether exploration ultimately results in commitment and what role social media plays in that regard. Future research should examine identity development as a whole process in the context of social media. Furthermore, the terms identity, self, self-identity, and self-concept have been used interchangeably, leading to conceptual ambiguity. It is important to distinguish that self or self-concept encompasses different identities in different domains and should not be considered synonymous with identity in future research.

In the context of social media research, the amount of time individuals spend on these platforms has been categorized using terms such as “excessive,” “problematic,” or “compulsive.” However, it is important to recognize that a higher quantity of time spent, based on individuals’ self-reports, on social media does not inherently indicate problematic use (O’Day & Heimberg, 2021). Similarly, the frequency of checking social media accounts does not necessarily equate to compulsive behavior. Determining what constitutes “excessive” use of social media might vary according to individual circumstances. It is recommended that future research should shift its focus from quantifying time spent on social media to examining the specific activities that adolescents are engaging in on these platforms. Understanding the nature and context of these activities will provide a more nuanced and comprehensive perspective on what is usual, excessive, or problematic use of social media.

Current research has largely focused on mainstream social media platforms that were popular in the late 2000s, throughout the 2010s and in early 2020s such as Facebook and Instagram. However, there is a significant shift towards newer platforms among young people, and the popularity and use of each platform change more rapidly than in the past. These newer platforms offer different opportunities for engagement. For example, young people on TikTok participate in video challenges, a mode of interaction that is not common on older platforms (Ahlse et al., 2020). YouTube offers extensive educational content (Orús et al., 2016), which can reinforce young people’s identities within educational domains. BeReal encourages users to share real-time, unedited photos to promote authenticity (Siepen, 2023), while Snapchat is known for its variety of filters that allow users to present an idealized self (Cruz, 2019). Although these platforms share some characteristics, each offers unique opportunities for engagement. As a result, it is important to update social media research frequently to track trends among adolescents and the new forms of interactions on the platforms and understand the impact of those on adolescent identity development.

In addition to the limitations of the field, this review has its own constraints. First, the studies included in this review are predominantly cross-sectional, which prevents tracking developmental processes over time and establishing a causal relationship between social media use and identity development. Furthermore, the scope of this review is limited by the specific search terms used, the databases selected, and the time frame for article retrieval, which may have excluded relevant studies. Only studies published in English were included, excluding potentially important articles in other languages as well as unpublished dissertations and book chapters. Finally, the quality assessment criteria were adapted for this review, so it is not possible to directly compare the quality scores with those of other studies.

Conclusion

This systematic review aimed to enrich the field of identity development research by synthesizing existing evidence on the role of social media use in adolescent identity development. Taken together, it is apparent that it is the activities adolescents engage in on social media that are associated with identity development, not the amount of time spent on social media. Further, authentic self-presentation is more common among adolescents with greater self-concept clarity, while fictitious self-presentation is related to identity exploration. Unfortunately, given the cross-sectional nature of most studies, it remains unclear whether social media use affects identity development in adolescence, whether the adolescent identity development process influences social media use, or whether these associations are perhaps bidirectional. Consequently, there is a need for well-designed longitudinal studies to capture the temporal direction of this relationship. Lastly, measuring only the time spent on social media limits the understanding of the relationship between social media engagement and identity development. Future research should focus on adolescents’ activities, interactions, and the content they engage with on social media to provide a more complete picture of this relationship.

Acknowledgements

The authors gratefully acknowledge the generous support provided by the following institutions. Hamide Avci received a PhD scholarship from the Ministry of National Education of the Republic of Turkey. Laura Baams was supported by the research program Innovational Research Incentives Scheme Veni (016.Veni.195.099), which is financed by the 10.1007/s40894-024-00251-1 Dutch Research Council (NWO). Tina Kretschmer was supported by a European Research Council Starting Grant (Grant Agreement Number 757364) and European Research Council Consolidator Grant (Grant Agreement Number 101087395).

Authors’ contribution

HA participated in conceiving of the study, conducted the search, screening, and eligibility assessments for all studies, performed data extraction and bias assessments, drafted and edited the manuscript; LB was involved in conceiving of the study, supervised the analyses and writing process, reviewed and edited the manuscript; TK took part in conceiving of the study, conducted the title and abstract screening for 20% of the studies, supervised the analyses and writing process, reviewed and edited the manuscript. All authors approved of the final manuscript as submitted.

Declarations

Competing Interests

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Declaration of the Use of Generative AI and AI-Assisted Technologies

During the preparation of this work, HA used Chat GPT 4.0 to assist with editing grammar and correcting spelling mistakes. After using this tool, LB and TK reviewed and edited the content as needed, and the authors take full responsibility for the content of the publication.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- Ahlse, J., Nilsson, F., & Sandström, N. (2020). It’s time to TikTok: Exploring Generation Z’s motivations to participate in #Challenges (Bachelor’s thesis). Jönköping University. https://urn.kb.se/resolve?urn=urn:nbn:se:hj:diva-48708

- Andreassen, C. S., Pallesen, S., & Griffiths, M. D. (2017). The relationship between addictive use of social media, narcissism, and self-esteem: Findings from a large national survey. Addictive Behaviors, 64, 287–293. 10.1016/j.addbeh.2016.03.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balistreri, E., Busch-Rossnagel, N. A., & Geisinger, K. F. (1995). Development and preliminary validation of the ego identity process questionnaire. Journal of Adolescence, 18(2), 179–192. 10.1006/jado.1995.1012 [Google Scholar]

- Bell, B. T. (2019). You take fifty photos, delete forty-nine and use one: A qualitative study of adolescent image-sharing practices on social media. International Journal of Child-Computer Interaction, 20, 64–71. 10.1016/j.ijcci.2019.03.002 [Google Scholar]

- Berman, S. L. (2020). I identity distress. In S. Hupp, & J. D. Jewell (Eds.), The encyclopedia of child and adolescent development (pp. 1–11). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.

- Berman, S. L., Montgomery, M. J., & Kurtines, W. M. (2004). The development and validation of a measure of identity distress. Identity, 4(1), 1–8. 10.1207/S1532706XID0401_1 [Google Scholar]

- Berman, S. L., Weems, C. F., & Petkus, V. F. (2009). The prevalence and incremental validity of identity problem symptoms in a high school sample. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 40(2), 183–195. 10.1007/s10578-008-0117-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brunborg, G. S., & Burdzovic Andreas, J. (2019). Increase in time spent on social media is associated with modest increase in depression, conduct problems, and episodic heavy drinking. Journal of Adolescence, 74(1), 201–209. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2019.06.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Callero, P. L. (1985). Role-identity salience. Social Psychology Quarterly, 48(3), 203. 10.2307/3033681 [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, J. D., Trapnell, P. D., Heine, S. J., Katz, I. M., Lavallee, L. F., & Lehman, D. R. (1996). Self-concept clarity: Measurement, personality correlates, and cultural boundaries. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 70(1), 141–156. 10.1037/0022-3514.70.1.141 [Google Scholar]

- Caplan, S. E. (2010). Theory and measurement of generalized problematic internet use: A two-step approach. Computers in Human Behavior, 26(5), 1089–1097. 10.1016/j.chb.2010.03.012 [Google Scholar]

- Chittenden, T. (2010). Digital dressing up: Modelling female teen identity in the discursive spaces of the fashion blogosphere. Journal of Youth Studies, 13(4), 505–520. 10.1080/13676260903520902 [Google Scholar]

- Courtois, C., Mechant, P., De Marez, L., & Verleye, G. (2009). Gratifications and seeding behavior of online adolescents. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 15(1), 109–137. 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2009.01496.x [Google Scholar]

- Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (2018). CASP qualitative checklist. CASP UK. https://casp-uk.net/casp-tools-checklists

- Crocetti, E., Rubini, M., Luyckx, K., & Meeus, W. (2008). Identity formation in early and middle adolescents from various ethnic groups: From three dimensions to five statuses. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 37(8), 983–996. 10.1007/s10964-007-9222-2 [Google Scholar]

- Crocetti, E., Schwartz, S. J., Fermani, A., & Meeus, W. (2010). The Utrecht-Management of Identity commitments scale (U-MICS): Italian validation and cross-national comparisons. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 26(3), 172–186. 10.1027/1015-5759/a000024 [Google Scholar]

- Cruz, A. (2019). Let’s take a selfie! Living in a Snapchat beauty filtered world: The impact it has on women’s beauty perceptions (Electronic theses and dissertations No. 6471). University of Central Florida. https://stars.library.ucf.edu/etd/6471

- Cyr, B. A., Berman, S. L., & Smith, M. L. (2015). The role of communication technology in adolescent relationships and identity development. Child & Youth Care Forum, 44(1), 79–92. 10.1007/s10566-014-9271-0 [Google Scholar]

- Davis, K. (2013). Young people’s digital lives: The impact of interpersonal relationships and digital media use on adolescents’ sense of identity. Computers in Human Behavior, 29(6), 2281–2293. 10.1016/j.chb.2013.05.022 [Google Scholar]

- Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook friends: Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 12(4), 1143–1168. 10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x [Google Scholar]

- Farrugia, L., Lauri, M. A., Borg, J., & O’Neill, B. (2019). Have you asked for it? An exploratory study about Maltese adolescents’ use of askFm. Journal of Adolescent Research, 34(6), 738–756. 10.1177/0743558418775365 [Google Scholar]

- Ferraro, G., Caci, B., D’Amico, A., & Blasi, M. D. (2007). Internet addiction disorder: An Italian study. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10(2), 170–175. 10.1089/cpb.2006.9972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fioravanti, G., Bocci Benucci, S., Ceragioli, G., & Casale, S. (2022). How the exposure to beauty ideals on social networking sites influences body image: A systematic review of experimental studies. Adolescent Research Review, 7(3), 419–458. 10.1007/s40894-022-00179-4 [Google Scholar]

- Fullwood, C., James, B. M., & Chen-Wilson, C. H. J. (2016). Self-concept clarity and online self-presentation in adolescents. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking, 19(12), 716–720. 10.1089/cyber.2015.0623 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhow, C., & Robelia, B. (2009). Informal learning and identity formation in online social networks. Learning Media and Technology, 34(2), 119–140. 10.1080/17439880902923580 [Google Scholar]

- Guzzetti, B., & Gamboa, M. (2005). Online journaling: The informal writings of two adolescent girls. Research in the Teaching of English, 40(2), 168–206. 10.58680/rte20054494 [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez, L., Montgomery, M. J., & Kurtines, W. M. (2006). Identity distress and adjustment problems in at-risk adolescents. Identity, 6(1), 27–33. 10.1207/s1532706xid0601_3 [Google Scholar]

- Ho, S. S., Lwin, M. O., & Lee, E. W. J. (2017). Till logout do us part? Comparison of factors predicting excessive social network sites use and addiction between Singaporean adolescents and adults. Computers in Human Behavior, 75, 632–642. 10.1016/j.chb.2017.06.002 [Google Scholar]

- Huang, C. (2017). Time spent on social network sites and psychological well-being: A meta-analysis. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 20(6), 346–354.nd Social Networking, 20(6), 346–354. 10.1089/cyber.2016.0758 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Imperato, C., Mancini, T., & Musetti, A. (2022). Exploring the role of problematic social network site use in the link between reflective functioning and identity processes in adolescents. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction. 10.1007/s11469-022-00800-6 [Google Scholar]

- Keles, B., McCrae, N., & Grealish, A. (2020). A systematic review: The influence of social media on depression, anxiety and psychological distress in adolescents. International Journal of Adolescence and Youth, 25(1), 79–93. 10.1080/02673843.2019.1590851 [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, J., & Lynch, H. (2016). A shift from offline to online: Adolescence, the internet and social participation. Journal of Occupational Science, 23(2), 156–167. 10.1080/14427591.2015.1117523 [Google Scholar]

- Klimstra, T. A., Hale, I. I. I., Raaijmakers, W. W., Branje, Q. A. W., S. J. T., & Meeus, W. H. J. (2010). Identity formation in adolescence: Change or stability? Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 39(2), 150–162. 10.1007/s10964-009-9401-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolotouchkina, O., Rangel, C., & Gómez, P. N. (2023). Digital media and younger audiences. Media and Communication, 11(4), 124–128. 10.17645/mac.v11i4.7647 [Google Scholar]

- Kroger, J. (2006). Identity development: Adolescence through adulthood. SAGE.

- Larose, R., Lin, C., & Eastin, M. (2003). Unregulated internet usage: Addiction, habit, or deficient self-regulation? Media Psychology, 5(3), 225–253. 10.1207/S1532785XMEP0503_01 [Google Scholar]

- Lee, E. W. J., Ho, S. S., & Lwin, M. O. (2017). Extending the social cognitive model—examining the external and personal antecedents of social network sites use among Singaporean adolescents. Computers in Human Behavior, 67, 240–251. 10.1016/j.chb.2016.10.030 [Google Scholar]

- Leung, L. (2007). Stressful life events, motives for internet use, and social support among digital kids. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 10(2), 204–214. 10.1089/cpb.2006.9967 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LewandowskiJr., G. W., Nardone, N., & Raines, A. J. (2010). The role of self-concept clarity in relationship quality. Self and Identity, 9(4), 416–433. 10.1080/15298860903332191 [Google Scholar]

- Lichy, J., McLeay, F., Burdfield, C., & Matthias, O. (2022). Understanding pre-teen consumers social media engagement. International Journal of Consumer Studies. 10.1111/ijcs.12821 [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C. Y., Broström, A., Nilsen, P., Griffiths, M. D., & Pakpour, A. H. (2017). Psychometric validation of the Persian Bergen Social Media Addiction Scale using classic test theory and Rasch models. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 6(4), 620–629. 10.1556/2006.6.2017.071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Livingstone, S. (2008). Taking risky opportunities in youthful content creation: Teenagers’ use of social networking sites for intimacy, privacy and self-expression. New Media & Society, 10(3), 393–411. [Google Scholar]

- Manzi, C., Coen, S., Regalia, C., Yévenes, A. M., Giuliani, C., & Vignoles, V. L. (2018). Being in the social: A cross-cultural and cross-generational study on identity processes related to Facebook use. Computers in Human Behavior, 80, 81–87. 10.1016/j.chb.2017.10.046 [Google Scholar]

- Mazur, E., & Kozarian, L. (2010). Self-presentation and interaction in blogs of adolescents and young emerging adults. Journal of Adolescent Research, 25(1), 124–144. 10.1177/0743558409350498 [Google Scholar]

- Morsunbul, U., Crocetti, E., Cok, F., & Meeus, W. (2014). Brief report: The Utrecht-Management of Identity commitments Scale (U‐MICS): Gender and age measurement invariance and convergent validity of the Turkish version. Journal of Adolescence, 37(6), 799–805. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2014.05.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mueller, A., Mitchell, J. E., Peterson, L. A., Faber, R. J., Steffen, K. J., Crosby, R. D., & Claes, L. (2011). Depression, materialism, and excessive internet use in relation to compulsive buying. Comprehensive Psychiatry, 52(4), 420–424. 10.1016/j.comppsych.2010.09.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institutes of Health (2014). Quality assessment tool for observational cohort and cross-sectional studies. National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health-topics/study-quality-assessment-tools

- Nesi, J., Telzer, E. H., & Prinstein, M. J. (2020). Adolescent development in the digital media context. Psychological Inquiry, 31(3), 229–234. 10.1080/1047840X.2020.1820219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Noon, E. J. (2020). Compare and despair or compare and explore? Instagram social comparisons of ability and opinion predict adolescent identity development. Cyberpsychology: Journal of Psychosocial Research on Cyberspace, 14(2). 10.5817/CP2020-2-1

- Noon, E. J., Schuck, L. A., Guțu, S. M., Şahin, B., Vujović, B., & Aydın, Z. (2021). To compare, or not to compare? Age moderates the relationship between social comparisons on instagram and identity processes during adolescence and emerging adulthood. Journal of Adolescence, 93(1), 134–145. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.10.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Day, E. B., & Heimberg, R. G. (2021). Social media use, social anxiety, and loneliness: A systematic review. Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 3, 100070. 10.1016/j.chbr.2021.100070 [Google Scholar]

- Orús, C., Barlés, M. J., Belanche, D., Casaló, L., Fraj, E., & Gurrea, R. (2016). The effects of learner-generated videos for YouTube on learning outcomes and satisfaction. Computers & Education, 95, 254–269. 10.1016/j.compedu.2016.01.007 [Google Scholar]

- Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan—a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5(1). 10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Page, M. J., Moher, D., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., et al. (2021). PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. Bmj, n160. 10.1136/bmj.n160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pangrazio, L. (2019). Technologically situated: The tacit rules of platform participation. Journal of Youth Studies, 22(10), 1308–1326. 10.1080/13676261.2019.1575345 [Google Scholar]

- Pelling, E. L., & White, K. M. (2009). The theory of planned behavior applied to young people’s use of social networking web sites. CyberPsychology & Behavior, 12(6), 755–759. 10.1089/cpb.2009.0109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pop, E. I., Negru-Subtirica, O., Crocetti, E., Opre, A., & Meeus, W. (2016). On the interplay between academic achievement and educational identity: A longitudinal study. Journal of Adolescence, 47, 135–144. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2015.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson, J. M. (2016). Online iDentity formation and the high school theatre trip. McGill Journal of Education / Revue des Sciences de l’éducation De McGill, 51(2), 771–786. 10.7202/1038602ar [Google Scholar]

- Riehm, K. E., Feder, K. A., Tormohlen, K. N., Crum, R. M., Young, A. S., Green, K. M., et al. (2019). Associations between time spent using social media and internalizing and externalizing problems among US youth. JAMA Psychiatry, 76(12), 1266–1273. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal, D. A., Gurney, R. M., & Moore, S. M. (1981). From trust on intimacy: A new inventory for examining Erikson’s stages of psychosocial development. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 10(6), 525–537. 10.1007/BF02087944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, K. L., Dayanim, S., & Matthias, S. (2008). Personal homepage construction as an expression of social development. Developmental Psychology, 44(2), 496–506. 10.1037/0012-1649.44.2.496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schwartz, S. J., Meca, A., & Petrova, M. (2017). Who am I and why does it matter? Linking personal identity and self-concept clarity. In J. Lodi-Smith & K. G. DeMarree (Eds.), Self-concept clarity (pp. 145–164). Springer International Publishing. 10.1007/978-3-319-71547-6_8

- Sebre, S. B., & Miltuze, A. (2021). Digital media as a medium for adolescent identity development. Technology Knowledge and Learning, 26(4), 867–881. 10.1007/s10758-021-09499-1 [Google Scholar]

- Senekal, J. S., Groenewald, R., Wolfaardt, G., Jansen, L., C., & Williams, K. (2023). Social media and adolescent psychosocial development: A systematic review. South African Journal of Psychology, 53(2), 157–171. 10.1177/00812463221119302 [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro, L. A. S., & Margolin, G. (2014). Growing up wired: Social networking sites and adolescent psychosocial development. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 17(1), 1–18. 10.1007/s10567-013-0135-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharif, S. P., & Khanekharab, J. (2017). Identity confusion and materialism mediate the relationship between excessive social network site usage and online compulsive buying. Cyberpsychology Behavior and Social Networking, 20(8), 494–500. 10.1089/cyber.2017.0162 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shek, D. T. L., Siu, A. M. H., & Tak, Y. L. (2007). The Chinese positive youth development scale: A validation study. Research on Social Work Practice, 17(3), 380–391. 10.1177/1049731506296196 [Google Scholar]

- Sica, L. S., Sestito, A., L., & Ragozini, G. (2014). Identity coping in the first years of university: Identity diffusion, adjustment, and identity distress. Journal of Adult Development, 21(3), 159–172. 10.1007/s10804-014-9188-8 [Google Scholar]

- Siepen, A. (2023). Constructing liveness on social media to establish authenticity: BeReal, a case study (Master’s thesis). Utrecht University. https://studenttheses.uu.nl/handle/20.500.12932/43969

- Statista (2022). Global social networks ranked by number of users 2022. Statista. Retrieved July 18, 2022, from https://www.statista.com/statistics/272014/global-social-networks-ranked-by-number-of-users/

- Subrahmanyam, K., Garcia, E. C. M., Harsono, L. S., Li, J. S., & Lipana, L. (2009). In their words: Connecting on-line weblogs to developmental processes. The British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 27(Pt 1), 219–245. 10.1348/026151008x345979 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, A. L., Kendis, R. J., Porac, J., & Fine, J. T. (1977). A short measure of eriksonian ego identity. Journal of Personality Assessment, 41(3), 279–284. 10.1207/s15327752jpa4103_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terry, D. J., Hogg, M. A., & White, K. M. (1999). The theory of planned behaviour: Self-identity, social identity and group norms. British Journal of Social Psychology, 38(3), 225–244. 10.1348/014466699164149 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Van Dijk, M. P. A., Branje, S., Keijsers, L., Hawk, S. T., Hale, W. W., & Meeus, W. (2014). Self-concept clarity across adolescence: Longitudinal associations with open communication with parents and internalizing symptoms. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 43(11), 1861–1876. 10.1007/s10964-013-0055-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W., & Lei, L. (2015). The structure and characteristics of adolescents’ mobile social media usage. Psychological Research Psychologische Forschung, 8(5), 57–63. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, W., Qian, G., Wang, X., Lei, L., Hu, Q., Chen, J., & Jiang, S. (2021). Mobile social media use and self-identity among Chinese adolescents: The mediating effect of friendship quality and the moderating role of gender. Current Psychology: A Journal for Diverse Perspectives on Diverse Psychological Issues, 40(9), 4479–4487. 10.1007/s12144-019-00397-5 [Google Scholar]

- Wängqvist, M., & Frisén, A. (2016). Who am I online? Understanding the meaning of online contexts for identity development. Adolescent Research Review, 1(2), 139–151. 10.1007/s40894-016-0025-0 [Google Scholar]

- Wu, J., Watkins, D., & Hattie, J. (2010). Self-concept clarity: A longitudinal study of Hong Kong adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 48(3), 277–282. 10.1016/j.paid.2009.10.011 [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C., & Brown, B. B. (2016). Online self-presentation on Facebook and self-development during the college transition. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 45(2), 402–416. 10.1007/s10964-015-0385-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C., Holden, S. M., & Carter, M. D. K. (2017). Emerging adults’ social media self-presentation and identity development at college transition: Mindfulness as a moderator. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 52, 212–221. 10.1016/j.appdev.2017.08.006 [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C., Holden, S. M., & Carter, M. D. K. (2018a). Social media social comparison of ability (but not opinion) predicts lower identity clarity: Identity processing style as a mediator. Journal of Youth & Adolescence, 47(10), 2114–2128. 10.1007/s10964-017-0801-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C., Holden, S. M., Carter, M. D. K., & Webb, J. J. (2018b). Social media social comparison and identity distress at the college transition: A dual-path model. Journal of Adolescence, 69, 92–102. 10.1016/j.adolescence.2018.09.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C., Carter, M. D. K., Webb, J. J., & Holden, S. M. (2020). Developmentally salient psychosocial characteristics, rumination, and compulsive social media use during the transition to college. Addiction Research & Theory, 28(5), 433–442. 10.1080/16066359.2019.1682137 [Google Scholar]

- Yu, L., & Shek, D. T. L. (2021). Positive youth development attributes and parenting as protective factors against adolescent social networking addiction in Hong Kong. Frontiers in Pediatrics. 10.3389/fped.2021.649232 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, R. Z., Cheok, A., & Khoo, E. (2011). Singaporean adolescents’ perceptions of online social communication: An exploratory factor analysis. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 45(2), 203–221. 10.2190/EC.45.2.e [Google Scholar]