Abstract

Introduction

Glucocorticoids are commonly used to treat immunoglobulin G4-related disease (IgG4-RD), but there is limited real-world evidence describing glucocorticoid-related toxicities in this population. This study assessed glucocorticoid use and toxicities during the first year after diagnosis among patients with IgG4-RD.

Methods

The IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus database was used to identify adults with IgG4-RD using a validated algorithm. Patients were stratified according to glucocorticoid use during the 12-month study period following the first observed IgG4-RD-related diagnosis (index date): low glucocorticoid use (prednisone equivalent daily dose [PEDD] < 5 mg/day) or high glucocorticoid use (PEDD ≥ 5 mg/day). Incident glucocorticoid-related toxicities were assessed during the study period and incidence was compared between groups using Chi-square tests.

Results

Among 295 patients with IgG4-RD, 150 (50.8%) had low glucocorticoid use, and 145 (49.2%) had high glucocorticoid use during the study period. In each glucocorticoid group, mean PEDD was highest in the 3 months post-index and subsequently decreased. At 12 months post-index, 24.7% of the low glucocorticoid use group and 60.7% of the high glucocorticoid use group were receiving glucocorticoids. The high glucocorticoid use group had a significantly higher mean (± standard deviation) number of incident glucocorticoid-related toxicities (1.8 ± 1.7 vs. 1.2 ± 1.3) and more frequently had ≥ 3 glucocorticoid-related toxicities (29.0% vs. 13.3%; both p < 0.01) compared to the low glucocorticoid use group. Specifically, cardiovascular- (29.0% vs. 18.7%), gastrointestinal- (29.7% vs. 16.0%), and infection-related (31.0% vs. 17.3%) toxicities were significantly more common in the high glucocorticoid use group than the low glucocorticoid use group (all p < 0.05).

Conclusions

In this retrospective, claims-based analysis, high glucocorticoid use was seen in half of patients with IgG4-RD during the first year following diagnosis. Patients with high glucocorticoid use experienced significantly more incident glucocorticoid-related toxicities than those with low use during this first year.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40744-025-00763-9.

Keywords: Clinical burden, Glucocorticoid, Immunoglobulin-G4-related disease, Toxicity

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Immunoglobulin G4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is a rare, relapsing, immune-mediated condition that can cause irreversible organ damage at affected sites. |

| Glucocorticoids are the standard first-line treatment for IgG4-RD, but they are associated with numerous toxicities and high relapse rates. |

| Given the lack of real-world studies evaluating glucocorticoid-related toxicities in IgG4-RD, this study assessed the use of glucocorticoids and the incidence of glucocorticoid-related toxicities during the first year after diagnosis among patients with IgG4-RD in the United States. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| In this real-world study, high glucocorticoid use was seen in half of patients with IgG4-RD during the first year following diagnosis, with nearly two-thirds of these patients using glucocorticoids at 12 months post-diagnosis. |

| Patients using high doses of glucocorticoids experienced significantly more incident glucocorticoid-related toxicities than those using low doses of glucocorticoids during this first year, highlighting the unmet need for effective and well-tolerated non-steroidal treatments to reduce exposure to glucocorticoids. |

Introduction

Immunoglobulin G4-related disease (IgG4-RD) is a rare, relapsing condition with an estimated prevalence of 5.3 cases per 100,000 commercially insured individuals in the United States (US) in 2019 [1–3]. IgG4-RD is characterized as an autoimmune disease that can cause fibroinflammatory lesions in multiple organs [1, 2]. Organs commonly affected include the pancreas and biliary tract, major salivary glands, orbits, and lacrimal glands, lungs, kidneys, and retroperitoneum [1, 4]. Given the heterogeneous and indolent nature of IgG4-RD, symptoms are often non-specific and can go unrecognized for months or years, sometimes until irreversible organ damage has already occurred [2].

As many patients already have symptomatic disease at the time of diagnosis, treatment is typically warranted to prevent further organ damage and induce clinical remission [5, 6]. Glucocorticoids are the most commonly used first-line treatment of IgG4-RD, with a consensus management statement recommending a high dose of glucocorticoids for 2–4 weeks, followed by a gradual taper to discontinuation over 3–6 months [5]. While glucocorticoids are effective at high doses, with the first prospective study in IgG4-RD demonstrating an overall response rate of 93.2% [7], the majority of patients experience a relapse within 3 years of diagnosis, often during glucocorticoid tapering or following discontinuation [8]. Moreover, patients with severe disease (e.g., affecting multiple organs) may be less likely to achieve complete remission with standard courses of glucocorticoids [6]. Non-steroidal agents like conventional disease-modifying anti-rheumatic drugs (e.g., azathioprine, mycophenolate mofetil) and rituximab may be considered, but evidence supporting their efficacy is limited [5, 6]. Thus, patients are often treated with prolonged or repeated courses of glucocorticoids.

Further complicating the management of IgG4-RD is the risk of toxicities associated with glucocorticoid use [5]. In particular, nearly half of the patients treated with glucocorticoids in the prospective IgG4-RD study experienced glucose intolerance [7]. The link between glucocorticoid use and toxicity is well-documented in other immune-mediated conditions [9–11], with common toxicities including hypertension, cardiac arrhythmia, gastrointestinal bleeding, infections, osteoporosis, and cataracts [12]. A small clinical trial by Wu et al. found that patients with IgG4-RD receiving high doses of prednisone (i.e., 0.8–1.0 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks) experienced more glucocorticoid toxicities than those receiving medium doses (i.e., 0.5–0.6 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks) [13]. Additionally, the clinical presentation of IgG4-RD is often complicated by the occurrence of comorbidities associated with IgG4-related pancreatitis, including diabetes mellitus and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency, which may increase their risk of glucocorticoid toxicities [2]. However, there are limited real-world studies characterizing glucocorticoid exposure and related toxicities among patients with IgG4-RD, including those with pancreatic and/or biliary manifestation. Therefore, this study was conducted to assess the use of glucocorticoids and incidence of glucocorticoid-related toxicities during the first year after diagnosis among patients with IgG4-RD, including among a subgroup of patients with pancreatic and/or biliary manifestation.

Methods

Data Source

Claims data from January 2011 to June 2022 from the IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus database were used. The IQVIA database includes fully adjudicated medical and pharmacy claims data and is representative of the commercially insured US population under 65 years of age. Information available in the database includes inpatient and outpatient diagnoses and procedures, prescription fills and outpatient-administered treatments, dates of service, costs, demographic variables (i.e., age, gender, geography), plan type, and monthly indicators of health plan enrollment. To protect privacy rights, the database publication guidelines require any cell sizes with N < 5 to be suppressed.

The study was considered exempt research under 45 CFR § 46.104(d)(4) as it involved only the secondary use of data that were de-identified in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), specifically, 45 CFR § 164.514.

Study Design and Patient Selection

In this retrospective cohort study, commercially insured adults (≥ 18 years) with IgG4-RD were identified using a validated algorithm developed by Wallace et al. [14], since International Classification of Disease (ICD) codes were not available for IgG4-RD at the time of the study. The index date was defined as the first observed IgG4-RD-related diagnosis code used to fulfill the algorithm requirements. The baseline period was defined as the 12 months prior to the index date, and the study period included the 12 months following the index date. Patients were required to have continuous health plan enrolment during both the baseline and study periods.

The cohort was stratified into two mutually exclusive groups based on glucocorticoid use during the study period: (1) “low glucocorticoid use” group, consisting of patients with a mean prednisone equivalent daily dose (PEDD) of < 5 mg, including patients with no glucocorticoid use; and (2) “high glucocorticoid use” group, consisting of patients with a mean PEDD of ≥ 5 mg. PEDD was assessed based on observed prescription fills of all relevant systemic (i.e., oral, intravenous, injected) glucocorticoids (i.e., prednisone, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, and dexamethasone). Only glucocorticoids received in a pharmacy setting (i.e., prescription fills) were included in the analysis because pharmacy data contain the necessary information to assess PEDD (i.e., quantity and strength). Glucocorticoids received in a medical setting (i.e., outpatient, inpatient, or emergency department) were not included in the analysis since PEDD could not be reliably assessed without complete data on dosage [15–17]. PEDD was calculated per patient as cumulative prednisone equivalent dose during the study period divided by 365 days [15–17]. The daily threshold of 5 mg was based on prior literature assessing glucocorticoid burden and toxicity in rheumatic conditions and discussions with experts [15, 16].

Study Measures and Statistical Analysis

Patient demographic characteristics (i.e., age, sex, region of residence, primary health plan type) were described on the index date and clinical characteristics (i.e., glucocorticoid use, IgG4-RD-related treatments, manifestations of IgG4-RD, specialists involved in care, Charlson Comorbidity Index [CCI], IgG4-RD-related comorbidities) were assessed during the study period. IgG4-RD-related treatments included the glucocorticoids described above and non-steroidal immunosuppressants (i.e., azathioprine, methotrexate, mycophenolic acid, mycophenolate mofetil, rituximab, and its biosimilars). National Drug Codes were used to identify all treatments, and Healthcare Common Procedure Coding System codes were also used to identify rituximab and its biosimilars. Patients were considered to have a manifestation of IgG4-RD (i.e., pancreatic, biliary, sialadenitis, lacrimal, retroperitoneum, mesenteritis, orbit, aortitis) if they had ≥ 1 corresponding ICD-9/10 code for that manifestation during the study period, as previously defined by Wallace et al. [14] Billing provider codes for medical services were used to identify specialists involved in care. Patients were considered to have an IgG4-RD-related comorbidity if they had ≥ 2 corresponding ICD-9/10 codes on different dates at least 30 days apart.

Incident glucocorticoid-related toxicities were described separately for each group during the study period and were defined as toxicities with ≥ 1 diagnosis code during the study period and no diagnosis during the baseline period. Glucocorticoid-related toxicities were reported individually and by organ system (i.e., cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, infections, metabolic/endocrine, musculoskeletal, neuropsychiatric, ophthalmologic) and were informed by prior literature and discussions with experts [9, 18].

Means, medians, and standard deviations (SDs) were reported for all continuous variables; frequency counts and percentages were reported for all categorical variables. The rates of incident glucocorticoid-related toxicities were compared between the low and high glucocorticoid use groups using Chi-square tests, with unadjusted p values reported. All analyses were conducted using the Statistical Analysis System (SAS) Enterprise Guide, Version 7.1 (SAS, Cary, NC, USA).

Subgroup Analysis

All analyses were replicated among a subgroup of the overall cohort of patients with IgG4-RD that had ≥ 1 diagnosis for a pancreatic and/or biliary manifestation during the study period, as defined above.

Results

Patient Demographic Characteristics

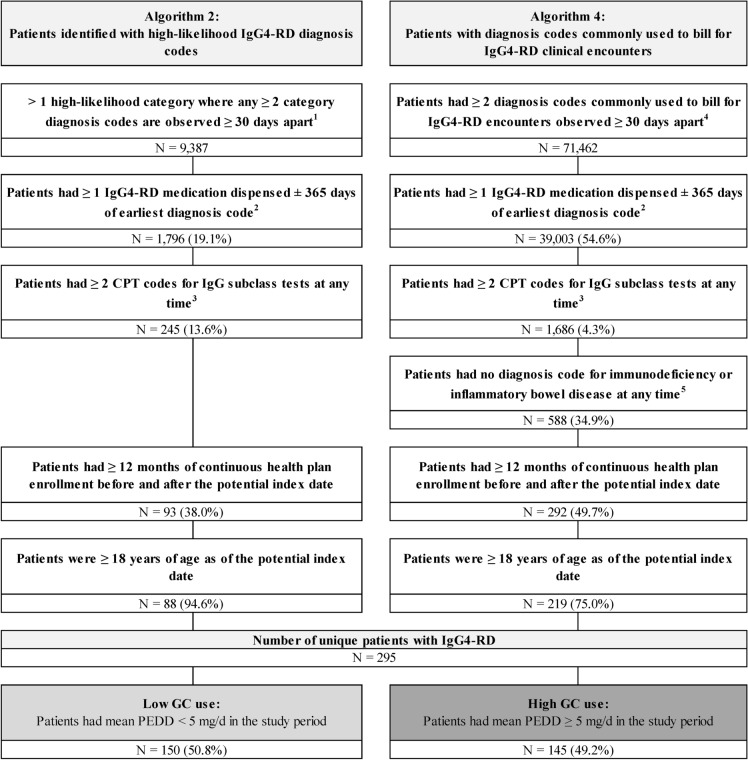

Among 295 patients with IgG4-RD included in the study, 150 (50.8%) had low glucocorticoid use (mean PEDD < 5 mg) and 145 (49.2%) had high glucocorticoid use (mean PEDD ≥ 5 mg) during the study period (Fig. 1). Patient demographic characteristics were generally similar between the two groups (Table 1), except for sex (low glucocorticoid use: 55.3% female; high glucocorticoid use: 45.5% female). Mean ± SD age was 48.9 ± 12.7 and 50.8 ± 12.4 years in the low glucocorticoid use and high glucocorticoid use groups, respectively.

Fig. 1.

Sample selection. CPT Common Procedural Terminology, d day, GC glucocorticoid, ICD International Classification of Diseases, IgG4-RD immunoglobulin G4-related disease, mg milligram, N number, PEDD prednisone equivalent daily dose. 1. High-likelihood diagnosis codes are based on the list available in Wallace et al. [14]. 2. IgG4-RD medications are based on the list available in Wallace et al. [14]. 3. The CPT code used to identify IgG subclass test was 82,787. 4. Diagnosis codes commonly used to bill for IgG4-RD encounters were D89.89 and D89.9

Table 1.

Patient demographic characteristics

| Patient characteristics1 | Low GC use | High GC use |

|---|---|---|

| N = 150 | N = 145 | |

| Age, mean ± SD [median] | 48.9 ± 12.7 [53.0] | 50.8 ± 12.4 [54.0] |

| Female, N (%) | 83 (55.3%) | 66 (45.5%) |

| Region of residence, N (%) | ||

| South | 56 (37.3%) | 60 (41.4%) |

| Midwest | 45 (30.0%) | 39 (26.9%) |

| Northeast | 25 (16.7%) | 24 (16.6%) |

| West | 24 (16.0%) | 21 (14.5%) |

| Unknown | < 5 | < 5 |

| Primary health plan type, N (%) | ||

| Preferred Provider Organization | 107 (71.3%) | 107 (73.8%) |

| Health Maintenance Organization | 23 (15.3%) | 23 (15.9%) |

| Point of Service | 10 (6.7%) | 9 (6.2%) |

| Consumer-Directed Health Care | < 5 | 5 (3.4%) |

| Indemnity/Traditional | 5 (3.3%) | < 5 |

| Other/Unknown | < 5 | < 5 |

GC glucocorticoid, N number, SD standard deviation

1Patient characteristics were assessed as of the index date

Glucocorticoid Use and Clinical Characteristics

Across the 12-month study period, mean ± SD PEDD was 1.4 ± 1.5 mg in the low glucocorticoid use group and 12.0 ± 6.3 mg in the high glucocorticoid use group (Table 2). For both groups, mean ± SD PEDD was highest in the 3 months following the index date (low glucocorticoid use: 2.6 ± 4.0 mg; high glucocorticoid use: 21.4 ± 14.7 mg) and subsequently decreased throughout the study period (low glucocorticoid use: 1.4 ± 2.5 mg during months 4–6, 1.0 ± 2.6 mg during months 7–9, 0.9 ± 2.1 mg from months 10–12; high glucocorticoid use: 12.7 ± 11.0 mg during months 4–6, 7.4 ± 9.0 mg during months 7–9, 7.0 ± 9.1 mg during months 10–12). At 12 months post-index date, fewer patients in the low glucocorticoid use group (24.7%) than the high glucocorticoid use group (60.7%) were receiving glucocorticoids. In contrast, use of ≥ 1 non-steroidal IgG4-RD-related immunosuppressants was similar between the two groups (low glucocorticoid use: 49.3%; high glucocorticoid use: 50.3%; Table 2) during the study period.

Table 2.

Patient clinical characteristics

| Clinical characteristics1 | Low GC use | High GC use | |

|---|---|---|---|

| N = 150 | N = 145 | ||

| PED summary | |||

| Patients with any GC use2, N (%) | 103 (68.7%) | 145 (100.0%) | |

| Number of GC prescription fills, mean ± SD [median] | 1.8 ± 2.2 [1.0] | 6.4 ± 3.6 [6.0] | |

| PEDD (mg), mean ± SD [median] | 1.4 ± 1.5 [1.1] | 12.0 ± 6.3 [9.8] | |

| Cumulative PED (mg), mean ± SD [median] | 528.6 ± 549.4 [393.8] | 4366.1 ± 2294.6 [3571.6] | |

| Cumulative days of supply, mean ± SD [median] | 43.0 ± 76.0 [20.5] | 195.6 ± 124.5 [169.0] | |

| IgG4-RD treatments, N (%) | 136 (90.7%) | 145 (100.0%) | |

| GC | 103 (68.7%) | 145 (100.0%) | |

| Prednisone | 84 (56.0%) | 139 (95.9%) | |

| Dexamethasone | 16 (10.7%) | 13 (9.0%) | |

| Methylprednisolone | 27 (18.0%) | 15 (10.3%) | |

| Prednisolone | < 5 | < 5 | |

| Non-steroidal | 74 (49.3%) | 73 (50.3%) | |

| Azathioprine | 19 (12.7%) | 33 (22.8%) | |

| Methotrexate | 23 (15.3%) | 5 (3.4%) | |

| Mycophenolate mofetil | 8 (5.3%) | 19 (13.1%) | |

| Rituximab | 29 (19.3%) | 32 (22.1%) | |

| Mycophenolic acid | < 5 | < 5 | |

| Manifestation of IgG4-RD, N (%) | |||

| Pancreas | 29 (19.3%) | 68 (46.9%) | |

| Biliary | 25 (16.7%) | 57 (39.3%) | |

| Sialadenitis | 8 (5.3%) | 12 (8.3%) | |

| Lacrimal | < 5 | 7 (4.8%) | |

| Retroperitoneum | < 5 | < 5 | |

| Mesenteritis | < 5 | < 5 | |

| Orbit | < 5 | < 5 | |

| Aortitis | < 5 | < 5 | |

| Top 5 most frequent specialists involved in care3, N (%) | |||

| Internal medicine | 48 (32.0%) | 48 (33.1%) | |

| Gastroenterology | 39 (26.0%) | 49 (33.8%) | |

| Rheumatology | 37 (24.7%) | 37 (25.5%) | |

| Ophthalmology | 24 (16.0%) | 31 (21.4%) | |

| Cardiology | 22 (14.7%) | 28 (19.3%) | |

| CCI, mean ± SD [median] | 1.7 ± 1.9 [1.0] | 2.2 ± 2.1 [2.0] | |

| Comorbidities, N (%) | |||

| Hypertension | 34 (22.7%) | 59 (40.7%) | |

| Hyperlipidemia | 32 (21.3%) | 34 (23.4%) | |

| Gastro-esophageal reflux | 23 (15.3%) | 21 (14.5%) | |

| Malignant neoplasms | 18 (12.0%) | 19 (13.1%) | |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | 17 (11.3%) | 34 (23.4%) | |

| Muscle weakness | 13 (8.7%) | 7 (4.8%) | |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 9 (6.0%) | 10 (6.9%) | |

| Chronic kidney disease | 8 (5.3%) | 10 (6.9%) | |

| Congestive heart failure | 6 (4.0%) | 6 (4.1%) | |

| Glaucoma | 5 (3.3%) | < 5 | |

| Exocrine pancreatic insufficiency | < 5 | 12 (8.3%) | |

| Any pneumonia | < 5 | < 5 | |

| Osteoporosis | < 5 | 10 (6.9%) | |

| Atrial fibrillation | < 5 | 6 (4.1%) | |

| Cataract | < 5 | < 5 | |

| Hyperglycemia | < 5 | < 5 | |

| Stroke (cerebral infarction) | < 5 | < 5 | |

CCI Charlson Comorbidity Index, GC glucocorticoid, IgG4-RD immunoglobulin G4-related disease, mg milligram, N number, PEDD prednisone equivalent daily dose, SD standard deviation

1Clinical characteristics were assessed during the study period

2Glucocorticoids used in PEDD calculations included systemic (oral, injection, or intravenous) prednisone, prednisolone, methylprednisolone, and dexamethasone. Medical claims were not used since dose could not be reliably assessed (i.e., only pharmacy claims contained required strength and quantity information)

3Specialist involved in care was defined as the billing provider, as reported in IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus, observed in any outpatient visit claim(s) for each patient

Relative to the low glucocorticoid use group, patients in the high glucocorticoid use group had descriptively more frequent pancreatic (46.9% vs. 19.3%) and biliary (39.3% vs. 16.7%) manifestations and higher rates of certain comorbidities, such as hypertension (40.7% vs. 22.7%), type 2 diabetes mellitus (23.4% vs. 11.3%), and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (8.3% vs. < 3.3%). Additionally, mean ± SD CCI was numerically higher in the high glucocorticoid use group than the low glucocorticoid use group (2.2 ± 2.1 vs. 1.7 ± 1.9).

Incident Toxicities

During the study period, the high glucocorticoid use group had a significantly higher mean ± SD number of incident glucocorticoid-related toxicities (1.8 ± 1.7 vs. 1.2 ± 1.3; p < 0.01) and more frequently had ≥ 3 incident glucocorticoid-related toxicities (29.0% vs. 13.3%; p < 0.01) compared to the low glucocorticoid use group (Table 3). Specifically, cardiovascular-related (29.0% vs. 18.7%; p = 0.04), gastrointestinal-related (29.7% vs. 16.0%; p < 0.01), and infection-related (31.0% vs. 17.3%; p < 0.01) toxicities were significantly more common in the high glucocorticoid use group than the low glucocorticoid use group (Table 3). Among infection-related toxicities, sepsis was particularly and significantly more common among patients in the high glucocorticoid use group than the low glucocorticoid use group (7.6% vs. < 3.3%; p < 0.01). Other incident glucocorticoid-related toxicities that were significantly more common in the high glucocorticoid use group included type 2 diabetes mellitus (8.3% vs. < 3.3%; p = 0.01) and osteoporosis (9.0% vs. < 3.3%; p < 0.01).

Table 3.

Incident GC-related toxicities

| Incident GC-related toxicities1 | Low GC use | High GC use | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N = 150 | N = 145 | |||

| Any incident GC-related toxicity, N (%) | 99 (66.0%) | 108 (74.5%) | 0.11 | |

| Number of distinct GC-related toxicities2, mean ± SD [median] | 1.2 ± 1.3 [1.0] | 1.8 ± 1.7 [2.0] | < 0.01 | |

| No GC-related toxicities | 51 (34.0%) | 37 (25.5%) | 0.11 | |

| 1 GC-related toxicity | 49 (32.7%) | 33 (22.8%) | 0.06 | |

| 2 GC-related toxicities | 30 (20.0%) | 33 (22.8%) | 0.56 | |

| ≥ 3 GC-related toxicities | 20 (13.3%) | 42 (29.0%) | < 0.01 | |

| Cardiovascular, N (%) | 28 (18.7%) | 42 (29.0%) | 0.04 | |

| Cardiac arrhythmias | 8 (5.3%) | 11 (7.6%) | 0.43 | |

| Hypertension | 8 (5.3%) | 16 (11.0%) | 0.07 | |

| Myocardial infarction | < 5 | 7 (4.8%) | 0.1 | |

| Dyslipidemia | 15 (10.0%) | 17 (11.7%) | 0.63 | |

| Gastrointestinal, N (%) | 24 (16.0%) | 43 (29.7%) | < 0.01 | |

| Nausea and vomiting | 17 (11.3%) | 28 (19.3%) | 0.06 | |

| Gastrointestinal ulcers and bleeds | 11 (7.3%) | 20 (13.8%) | 0.07 | |

| Infections, N (%) | 26 (17.3%) | 45 (31.0%) | < 0.01 | |

| Fungal infections | 11 (7.3%) | 14 (9.7%) | 0.47 | |

| Urinary tract infection | 6 (4.0%) | 13 (9.0%) | 0.08 | |

| Pneumonia | < 5 | 10 (6.9%) | 0.16 | |

| Sepsis | < 5 | 11 (7.6%) | < 0.01 | |

| Metabolic/endocrine, N (%) | 17 (11.3%) | 27 (18.6%) | 0.08 | |

| Type 2 diabetes mellitus | < 5 | 12 (8.3%) | 0.01 | |

| Obesity | 14 (9.3%) | 16 (11.0%) | 0.63 | |

| Musculoskeletal, N (%) | 24 (16.0%) | 27 (18.6%) | 0.55 | |

| Osteoporosis | < 5 | 13 (9.0%) | < 0.01 | |

| Myopathy, paralysis, and other muscle weakness | 17 (11.3%) | 14 (9.7%) | 0.64 | |

| Neuropsychiatric, N (%) | 39 (26.0%) | 27 (18.6%) | 0.13 | |

| Anxiety | 11 (7.3%) | 20 (13.8%) | 0.07 | |

| Ophthalmologic, N (%) | 7 (4.7%) | 10 (6.9%) | 0.41 | |

| Cataract | 7 (4.7%) | 10 (6.9%) | 0.41 | |

GC glucocorticoid, N number, SD standard deviation

1Individual toxicities with a frequency of < 5 in both groups are not displayed (i.e., bipolar disorder, depression, fractures, herpes zoster, metabolic syndrome, migraine, osteonecrosis, psychosis, sleep disturbances, tuberculosis)

2Number of distinct GC-related toxicities was defined as the count of GC-related toxicities for which a patient had ≥ 1 claim with the respective diagnosis code(s)

Subgroup Analysis

Among the overall cohort of 295 patients with IgG4-RD included in the main analysis, 110 were classified as having pancreatic and/or biliary manifestations (Supplementary Table 1). Of these patients, 36 (32.7%) were classified into the low glucocorticoid use group and 74 (67.3%) into the high glucocorticoid use group. Notably, a descriptively higher proportion of patients with pancreatic and/or biliary manifestations had high glucocorticoid use relative to the overall cohort (67.3% vs. 49.2%).

Patients with pancreatic and/or biliary manifestations appeared to have a descriptively larger comorbidity burden than the overall cohort, particularly in terms of hyperlipidemia (low glucocorticoid use: 36.1%; high glucocorticoid use: 35.1%), type 2 diabetes mellitus (low glucocorticoid use: 19.4%; high glucocorticoid use: 32.4%), and exocrine pancreatic insufficiency (low glucocorticoid use: < 13.9%; high glucocorticoid use: 16.2%; Supplementary Table 2).

Relative to the overall cohort, patients with pancreatic or biliary manifestations in both the low and high glucocorticoid use groups generally had more incident glucocorticoid-related toxicities, particularly cardiovascular-related (low glucocorticoid use: 27.8%; high glucocorticoid use: 32.4%), gastrointestinal-related (low glucocorticoid use: 33.3%; high glucocorticoid use: 40.5%), and infection-related toxicities (low glucocorticoid use: 25.0%; high glucocorticoid use: 33.8%; Supplementary Table 3). While there was a trend towards higher rates in the high glucocorticoid use group, the differences between the two groups were not statistically significant.

Discussion

In this real-world analysis, approximately half of all patients with IgG4-RD used a mean prednisone-equivalent dose of ≥ 5 mg/day of glucocorticoids during the first year after diagnosis. Patients with high glucocorticoid use had more frequent pancreatic and biliary manifestations and a larger comorbidity burden relative to those with low glucocorticoid use. Compared with patients with low glucocorticoid use, those with high glucocorticoid use had significantly higher rates of incident glucocorticoid-related toxicities and were significantly more likely to have multiple toxicities in the year after IgG4-RD diagnosis. The most commonly reported incident glucocorticoid-related toxicities during the study period were cardiovascular-, gastrointestinal-, and infection-related toxicities. Lastly, patients with pancreatic or biliary manifestations had indicators of a higher comorbidity burden, more frequently had high glucocorticoid use, and had a greater glucocorticoid-related toxicity burden relative to the overall cohort of patients with IgG4-RD.

There is limited prior literature describing glucocorticoid-associated toxicities among patients with IgG4-RD and comparing the incidence of toxicities among patients with low vs. high glucocorticoid use. In a randomized controlled trial of 40 patients with IgG4-RD, Wu et al. found that glucocorticoid toxicities were more commonly observed among patients receiving high doses of prednisone (25.0%; 0.8–1.0 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks) than those receiving medium doses (10.0%; 0.5–0.6 mg/kg/day for 4 weeks), though no statistical comparison was conducted [13]. Glucocorticoid toxicities observed in that trial included extremity cramps, acid regurgitation, respiratory infections, and elevated blood glucose [13], the latter two of which aligned with the significantly higher rates of infections and type 2 diabetes mellitus among patients with high glucocorticoid use observed in the current study. While the trends reported by Wu et al. are consistent with the present findings, comparability may be limited by the varying dosage-based definitions used for the glucocorticoid use stratifications [13], as well as the inherent differences between clinical trials and real-world analyses. Nevertheless, the current study provides a first real-world account of toxicities among patients with IgG4-RD receiving glucocorticoids and confirms trends previously observed in the clinical trial setting. These findings highlight that the benefits of prescribing glucocorticoids to patients with IgG4-RD in clinical practice should be weighed against the risk of associated toxicity.

In this study, infection-related and gastrointestinal-related toxicities, which typically have an acute onset [12], were the most commonly observed toxicities among patients with high glucocorticoid use and were significantly more frequent compared to patients with low glucocorticoid use. In contrast, glucocorticoid toxicities that typically have a chronic onset, such as osteoporosis and cataracts [12], were less commonly observed. As such, it should be noted that these study findings provide a short-term assessment of glucocorticoid toxicities, and that the full safety burden of glucocorticoid use among patients with IgG4-RD is likely underestimated in this study, as chronic toxicities may take longer than 1 year to manifest. Notably, one-quarter of patients with low glucocorticoid use and almost two-thirds of the patients with high glucocorticoid use were receiving glucocorticoids at 12 months post diagnosis, which are likely to contribute to later-onset glucocorticoid-related toxicities that were not captured in this study.

Non-steroidal immunosuppressive agents like azathioprine, methotrexate, and mycophenolate mofetil can be considered in combination with glucocorticoids to reduce glucocorticoid toxicities, but there is limited scientific evidence supporting their efficacy in patients with IgG4-RD [5, 6]. One recent small clinical trial suggests that in patients treated with non-steroidal immunosuppressive agents and minimal glucocorticoid use (mean PEDD ≤ 5 mg), with clinically quiescent disease for at least 1 year, maintenance of the non-steroidal immunosuppressive agent while withdrawing glucocorticoids may be a suitable strategy to reduce the risk of IgG4-RD flares [19]. In addition, preliminary data has suggested that rituximab may be effective when glucocorticoids and non-steroidal immunosuppressive agents fail to induce remission [20]. Importantly, the use of non-steroidal IgG4-RD-related immunosuppressants in the present study was similar between the patients with low and high glucocorticoid use, suggesting that currently available treatment options have limited potential to reduce glucocorticoid use. These findings highlight the unmet need for effective and tolerable non-steroidal agents to provide adequate disease management while reducing exposure to glucocorticoids and the associated risks of toxicities.

Of note, the anti-CD19 monoclonal antibody inebilizumab was recently shown to reduce the risk of IgG4-RD disease flares by 87% compared to placebo (hazard ratio, 0.13; p < 0.001), with a significantly higher proportion of patients with flare-free, glucocorticoid-free complete remission (59% vs. 22%, respectively; odds ratio, 4.96; p < 0.001), in the phase 3, randomized, double-blind clinical trial MITIGATE [21]. Given patients treated with inebilizumab required lower exposure to glucocorticoids to induce and maintain remission in this trial, inebilizumab may represent a promising, glucocorticoid-sparing therapy for IgG4-RD [21].

The need for effective non-steroidal therapies may be particularly important for patients with IgG4-RD involving the pancreas and/or biliary tract, who we found to have greater glucocorticoid use, a larger burden of comorbidities, and higher incidence of glucocorticoid-related toxicities than the overall population of patients with IgG4-RD. This observation suggests that the clinical burden of glucocorticoid use may be intensified among this subgroup of patients, which may be due to a combination of elevated glucocorticoid use to manage pancreatic/biliary symptoms and potential synergy with underlying conditions that increase the risk of glucocorticoid toxicities [12]. Indeed, many patients with pancreatic involvement already have substantial exocrine or endocrine pancreatic insufficiency at the time of diagnosis or treatment initiation, which may predispose them to certain glucocorticoid toxicities like glucose intolerance [6, 22]. Therefore, these patients may particularly benefit from effective non-steroidal treatments to limit cumulative glucocorticoid exposure.

Limitations

The study findings should be considered within the context of certain limitations. Because an ICD code was not available for IgG4-RD at the time of study conduct, a validated algorithm was used to identify patients; as such, the date of diagnosis identified by the algorithm may not have been the true clinical diagnosis date. In addition, ICD codes used to identify manifestations of IgG4-RD may not always be recorded for reimbursement purposes, which may have resulted in the underreporting of clinical manifestations. Further, given the reason for treatment was not available in the claims data, it could not be confirmed if the treatments considered in this study were received specifically to manage IgG4-RD. Similarly, reasons for incident toxicity diagnoses and information related to disease relapse were not available in the claims data. Identification of incident glucocorticoid-related toxicities was based on diagnosis codes; therefore, it could not be confirmed that the incident diagnosis was due to glucocorticoid use. Because we did not control for confounding, factors like disease severity and underlying health may have impacted the results. Therefore, further research is warranted to confirm the causal relationship between level of glucocorticoid use and rate of associated toxicities in patients with IgG4-RD, as well as to assess the impact of different treatment strategies on relapse rates using appropriate data sources. Additionally, the study included commercially insured patients only and thus these findings may not be representative of patients with other types of insurance or without insurance coverage. For example, patients with Medicare coverage, who are generally older, may be more likely to experience glucocorticoid-related toxicities such as osteoporosis and cataracts, or worsening of underlying problems, such as diabetes. Accordingly, the present study may underestimate the overall burden of glucocorticoid-related toxicities. Lastly, as with all retrospective database studies, coding errors, data omissions, and rule-out diagnoses may have been present.

Conclusions

In this retrospective, claims-based analysis, high glucocorticoid use was seen in half of all patients with IgG4-RD during the first year following diagnosis, with nearly two-thirds of these patients using glucocorticoids at 12 months. Patients with high glucocorticoid use had more comorbidities and experienced significantly more incident glucocorticoid-related toxicities than those with low glucocorticoid use during this first year. Notably, the use of non-steroidal IgG4-RD immunosuppressants was similar between patients with low and high glucocorticoid use. Therefore, the identification of effective and well-tolerated glucocorticoid-sparing treatment options may allow for reduced glucocorticoid exposure in patients with IgG4-RD, with the subsequent potential to improve patient outcomes and reduce the clinical burden of this disease.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

Medical writing assistance was provided by professional medical writer, Christine Tam, MWC, an employee of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Amgen Inc, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript. Support for this assistance was funded by Amgen Inc.

Author Contributions

Zachary S. Wallace, Jenny Y. Park, Elizabeth Serra, Patrick Gagnon-Sanschagrin, Annie Guérin, Kristina Patterson, Haridarshan Patel, and Vikesh K. Singh have made substantial contributions to the conception or design of the study, or the acquisition, analysis, or interpretation of data, drafting the manuscript and revising it critically for important intellectual content, and have provided final approval of this version to be published and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

Funding

This study, manuscript, and Rapid Service Fee were funded by Amgen Inc.

Data Availability

The findings of this study are based on information licensed from IQVIA: IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus for the period 1/1/2011–6/30/2022 reflecting estimates of real-world activity. All rights reserved. Data access requests may be submitted via https://www.iqvia.com/locations/united-states.

Declarations

Conflict of interest

Zachary S. Wallace has received consulting fees from Amgen Inc and is now an employee of Amgen, but this study was conducted prior to his employment at Amgen. Jenny Y. Park, Kristina Patterson, and Haridarshan Patel are employees and stockholders of Amgen Inc. Elizabeth Serra, Patrick Gagnon-Sanschagrin, and Annie Guérin are employees of Analysis Group, Inc., a consulting company that has provided paid consulting services to Amgen Inc, which funded the development and conduct of this study and manuscript. Vikesh K. Singh has provided paid consulting services to Amgen, Panafina, and Ariel Precision Medicine.

Ethical Approval

The study was considered exempt research under 45 CFR § 46.104(d)(4) as it involved only the secondary use of data that were de-identified in compliance with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA), specifically, 45 CFR § 164.514.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: Part of the material in this manuscript was presented at the European Alliance of Associations for Rheumatology (EULAR) 2024 Congress, held June 12–15 in Vienna, Austria, as a poster presentation, and at the United European Gastroenterology Week, held October 12–15, 2024 in Vienna, Austria, as an oral presentation.

References

- 1.Floreani A, Okazaki K, Uchida K, et al. IgG4-related disease: Changing epidemiology and new thoughts on a multisystem disease. J Transl Autoimmun. 2021;4: 100074. 10.1016/j.jtauto.2020.100074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Perugino CA, Stone JH. IgG4-related disease: an update on pathophysiology and implications for clinical care. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2020;16(12):702–14. 10.1038/s41584-020-0500-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wallace ZS, Miles G, Smolkina E, et al. Incidence, prevalence and mortality of IgG4-related disease in the USA: a claims-based analysis of commercially insured adults. Ann Rheum Dis. 2023;82(7):957–62. 10.1136/ard-2023-223950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wallace ZS, Naden RP, Chari S, et al. The 2019 American College of Rheumatology/European League Against Rheumatism classification criteria for IgG4-related disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2020;72(1):7–19. 10.1002/art.41120. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Khosroshahi A, Wallace ZS, Crowe JL, et al. International consensus guidance statement on the management and treatment of IgG4-related disease. Arthritis Rheumatol. 2015;67(7):1688–99. 10.1002/art.39132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tanaka Y, Stone JH. Perspectives on current and emerging therapies for immunoglobulin G4-related disease. Mod Rheumatol. 2023;33(2):229–36. 10.1093/mr/roac141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Masaki Y, Matsui S, Saeki T, et al. A multicenter phase II prospective clinical trial of glucocorticoid for patients with untreated IgG4-related disease. Mod Rheumatol. 2017;27(5):849–54. 10.1080/14397595.2016.1259602. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lanzillotta M, Mancuso G, Della-Torre E. Advances in the diagnosis and management of IgG4-related disease. BMJ. 2020;16(369): m1067. 10.1136/bmj.m1067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen HL, Shen LJ, Hsu PN, et al. Cumulative burden of glucocorticoid-related adverse events in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus: findings from a 12-year longitudinal study. J Rheumatol. 2018;45(1):83–9. 10.3899/jrheum.160214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johnson S, Katyal N, Narula N, et al. adverse side effects associated with corticosteroid therapy: a study in 39 patients with generalized myasthenia gravis. Med Sci Monit. 2021;28(27): e933296. 10.12659/MSM.933296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Luis M, Freitas J, Costa F, et al. An updated review of glucocorticoid-related adverse events in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2019;18(7):581–90. 10.1080/14740338.2019.1615052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Noetzlin S, Breville G, Seebach JD, et al. Short-term glucocorticoid-related side effects and adverse reactions: a narrative review and practical approach. Swiss Med Wkly. 2022;3(152): w30088. 10.4414/smw.2022.w30088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wu Q, Chang J, Chen H, et al. Efficacy between high and medium doses of glucocorticoid therapy in remission induction of IgG4-related diseases: a preliminary randomized controlled trial. Int J Rheum Dis. 2017;20(5):639–46. 10.1111/1756-185X.13088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wallace ZS, Fu X, Cook C, et al. Derivation and validation of algorithms to identify patients with immunoglobulin-G4-related disease using administrative claims data. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2022;4(4):371–7. 10.1002/acr2.11405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.DerSarkissian M, Gu YM, Duh MS, et al. Clinical and economic burden in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus during the first year after initiating oral corticosteroids: a retrospective us database study. ACR Open Rheumatol. 2023;5(6):318–28. 10.1002/acr2.11550. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kabadi S, Yeaw J, Bacani AK, et al. Healthcare resource utilization and costs associated with long-term corticosteroid exposure in patients with systemic lupus erythematosus. Lupus. 2018;27(11):1799–809. 10.1177/0961203318790675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schultz NM, Penson DF, Wilson S, et al. Adverse events associated with cumulative corticosteroid use in patients with castration-resistant prostate cancer: an administrative claims analysis. Drug Saf. 2020;43(1):23–33. 10.1007/s40264-019-00867-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Yasir M, Goyal A, Sonthalia S. Corticosteroid adverse effects: National Library of Medicine; 2023 [cited 2024 June 3, 2023]. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK531462/

- 19.Peng L, Nie Y, Zhou J, et al. Withdrawal of immunosuppressants and low-dose steroids in patients with stable IgG4-RD (WInS IgG4-RD): an investigator-initiated, multicentre, open-label, randomised controlled trial. Ann Rheum Dis. 2024;83(5):651–60. 10.1136/ard-2023-224487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel U, Saxena A, Patel D, et al. Therapeutic uses of rituximab and clinical features in immunoglobulin G4-related disease: a systematic review. Cureus. 2023;15(9): e45044. 10.7759/cureus.45044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Stone JH, Khosroshahi A, Zhang W, et al. Inebilizumab for treatment of IgG4-related disease. N Engl J Med. 2024. 10.1056/NEJMoa2409712. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lanzillotta M, Campochiaro C, Mancuso G, et al. Clinical phenotypes of IgG4-related disease reflect different prognostic outcomes. Rheumatology (Oxford). 2020;59(9):2435–42. 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The findings of this study are based on information licensed from IQVIA: IQVIA PharMetrics® Plus for the period 1/1/2011–6/30/2022 reflecting estimates of real-world activity. All rights reserved. Data access requests may be submitted via https://www.iqvia.com/locations/united-states.