Abstract

Precision psychiatry aims to improve routine clinical practice by integrating biological, clinical, and environmental data. Many studies have been performed in different areas of research on major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia. Neuroimaging and electroencephalography findings have identified potential circuit-level abnormalities predictive of treatment response. Protein biomarkers, including IL-2, S100B, and NfL, and the kynurenine pathway illustrate the role of immune and metabolic dysregulation. Circadian rhythm disturbances and the gut microbiome have also emerged as critical transdiagnostic contributors to psychiatric symptomatology and outcomes. Moreover, advances in genomic research and polygenic scores support the perspective of personalized risk stratification and medication selection.

While challenges remain, such as data replication issues, prediction model accuracy, and scalability, the progress so far achieved underscores the potential of precision psychiatry in improving diagnostic accuracy and treatment effectiveness.

Keywords: major depression, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, personalized medicine, biomarkers

INTRODUCTION

Precision psychiatry is emerging as a transformative approach aiming to deliver personalized, accurate, and effective treatments.1-5 It represents a departure from the traditional one-size-fits-all and trial-and-error approaches, which have long struggled to capture the complexity, heterogeneity, and dynamic nature of psychiatric disorders. Instead, precision psychiatry aims to integrate data from neuroimaging, molecular biomarkers, and genetic profiles to clinical assessments, digital phenotypes, and real-time measures into predictive models and decision-making aids.

Similarly to other areas of medicine, precision psychiatry leverages recent advances in research evidence and computational methods, including machine learning, natural language processing, and systems biology approaches.6 Over the past decade, large-scale consortia and biobanks have furnished unprecedented volumes of genetic, imaging, and clinical data, enabling the detection of biomarkers.7-10 Similarly, the use of electronic health records, wearables, smartphone applications, and digital phenotyping tools has provided real-time data on mood fluctuations, sleep patterns, physical activity, and social interactions, all of which contribute to more detailed phenotyping of the patient time course within real-world contexts.11-13

Nevertheless, precision psychiatry still faces several challenges: harmonization and integration of diverse data sources, robustness and reproducibility of predictive models, and translation of theoretical findings into clinically useful tools. In recent decades, many biomarkers have failed independent replication or have proven challenging to implement in routine clinical settings. Ethical and regulatory considerations also need attention, given that personalization efforts must face privacy concerns, potential data collection and analysis biases, and the uneven global distribution of healthcare resources and digital infrastructures. Furthermore, patient engagement and acceptability of new technologies must be carefully addressed, as individuals may react differently to continuous data monitoring or the use of artificial intelligence in guiding treatment.

This narrative review is an initiative of the CINP Global Networking Community for Precision Psychiatry. It aims to provide a general overview of the potential biomarkers applicable to precision psychiatry, emphasizing their clinical and research relevance. While this work is not exhaustive and focuses on offering a broad perspective and some examples rather than detailed descriptions, which are available in other relevant literature,1-4 it emphasizes the need for initiatives like the CINP GNC on precision psychiatry for advancing the field by fostering collaboration and supporting innovative research.

Clinical Features

The integration of biological markers into psychiatric diagnosis and treatment offers the potential for enhanced precision. Yet, it is improbable that this will achieve the level of diagnostic accuracy observed in other medical fields, such as oncology. This limitation stems from the complexity and heterogeneity of psychiatric disorders, whose risk is modulated by genetic, environmental, and psychosocial factors that vary among individuals.1,4,14,15 Clinical evaluation remains vital, complementing biological insights with individualized patient assessments.

Clinicians already apply elements of precision psychiatry during patient history collection and interviews, gathering clinical details that guide treatment. However, subjective judgment and the lack of universal guidelines often lead to inconsistent outcomes.16-18

Symptom profiles, such as depression manifesting in diverse patterns, complicate treatment matching.19 For example, activating antidepressants may suit somnolence, while sedative agents benefit anxiety-related insomnia.20 However, when the clinician combines the many possible symptom profiles with the dozens of available drugs, it becomes clear how complex this combination pathway is. Surprisingly, there are very few studies and indications regarding the most appropriate matching of the symptom profiles with pharmacodynamic profiles. A small pilot study using these symptomatological criteria in identifying antidepressant treatment classes suggests that this approach is particularly effective in achieving a relative level of precision psychiatry at the clinical level.21 This is a field of investigation that needs further development.

In addition, drug tolerability significantly influences adherence, as intolerable side effects lead to discontinuation.22 Balancing efficacy with tolerability is underdeveloped in clinical practice. Additionally, previous treatment responses and family history provide predictive value, as relatives’ responses may indicate shared genetic factors.23

The complexity of precision psychiatry is amplified by drug interactions, necessitating individualized approaches integrating symptomatology, tolerability, and treatment history.24

Therapeutic drug monitoring (TDM) is of potential support enabling individualized dosing by quantifying drug concentrations in blood and considering interindividual pharmacokinetic variability due to age, disease, drug interactions, and genetic polymorphisms.25,26 Many psychiatric and neurologic drugs may show over 20-fold interpatient variability in blood concentrations at the same dose. Main indications for TDM include non-response at standard doses, suspected non-adherence, polypharmacy, vulnerable populations (eg, children, elderly, pregnant women), and known metabolic abnormalities. Therapeutic drug monitoring is best applied under steady-state conditions and requires integration into clinical workflows to avoid misinterpretation. Therapeutic drug monitoring is particularly well-supported for tricyclic antidepressants, lithium, anticonvulsants, and antipsychotics such as clozapine, but it may also be beneficial for other antidepressants.27 However, in specific cases, many other psychotropic drugs may benefit from TDM, and it is usually reported in the drug label.

The challenge of applying precision psychiatry in routine clinical settings therefore largely stems from the high complexity of managing these numerous interrelated factors.28 Addressing this complexity may be feasible with decision-support software capable of synthesizing multidimensional data and generating probabilistic treatment recommendations. Indeed, recent reports suggest that recent large language models may outperform medical diagnostic skills,29 though the large number of available tools and their still embryonic development suggest caution.30 However, such tools could soon assist clinicians by integrating clinical and biological data, enabling them to make evidence-based, individualized treatment decisions consistently and efficiently.31

Neuroimaging Techniques (Magnetic Resonance Imaging Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging, Positron Emission Tomography)

Extensive research has explored neuroimaging biomarkers. However, although studies reveal differences in brain volumes and connectivity across patients and responders, biomarkers predictive at the individual level remain scarce, and definitive markers guiding tailored psychiatric treatments remain elusive. Promising studies identify predictors of treatment response in schizophrenia (SCZ) and mood disorders, including structural integrity and functional connectivity.32 For example, Drysdale and colleagues identified 4 depression subtypes characterized by distinct patterns of abnormal functional connectivity and clinical symptom profiles.33 Task-based and resting-state dysfunction profiles in major depression (MDD) and anxiety predict responses to behavioral and pharmacological interventions.34 In SCZ, gray matter volume and functional connectivity have been proposed as predictors of treatment response, including clozapine, Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (TMS), and electroconvulsive therapy, though further validation in larger samples is needed.35 Using cognitive and electrophysiological data, biotype-based classification identifies psychotic patient subgroups based on differences in brain volumes and neurocognitive measures, achieving better discrimination than traditional categories, enabling the identification of psychotic patient subgroups distinguished by differences in brain volumes and neurocognitive measures, and achieving greater between-group discrimination than traditional diagnostic categories.32,36

The biotype approach has also shown promise in neurological disorders. In Parkinson’s disease, biotypes linked to subcortical brain volume differences predict disease progression over 5 years.37 Similarly, Alzheimer’s disease subtypes identified via resting-state functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) correlate with distinct cognitive symptoms and biomarkers, including cerebrospinal fluid Aβ1-42 and the ApoE4 genotype.

In MDD, a recent paper reported very promising results.38 A precision functional mapping with a longitudinal analysis of individuals scanned up to 62 times over 1.5 years showed a 2-fold expansion in the cortical area occupied by the salience network among individuals with depression, that was stable over time, unaffected by mood states and present even in children before depressive symptoms develop. Further, connectivity changes in frontostriatal circuits may predict anhedonia and anxiety fluctuations.

Biomarker identification is also essential for novel treatments. A pharmacoBOLD approach proposed ketamine response biomarkers, showing strong activation in the dorsal anterior cingulate cortex and anterior insula with high cross-site consistency.39

Finally, machine learning-based biotype classification offers a promising alternative to traditional diagnostic categories and may improve patient classification by identifying biotypes over traditional diagnostic categories. For instance, a trial using κ-opioid receptor antagonism demonstrated increased ventral striatum activation during reward anticipation, linking neuroimaging biomarkers to clinical outcomes.40

Electroencephalography in Precision Psychiatry

Electroencephalography (EEG) is a noninvasive neurophysiological technique that records brain activity with high temporal precision, making it highly suitable for precision psychiatry. Unlike functional neuroimaging methods such as fMRI or positron emission tomography, EEG is cost-effective, scalable, and can be easily applied in research, clinical trials, and clinical settings.41,42 Recent advancements in computational analyses, including machine learning and network-based approaches, have allowed EEG to emerge as a valuable tool for patient stratification, treatment prediction, and biomarker discovery in psychiatric disorders such as major depressive disorder42 and SCZ.43,44 One well-established biomarker in depression seems to be the pretreatment resting-state frontal alpha asymmetry. For example, patients with depression who responded to fluoxetine exhibited increased EEG alpha power and alpha asymmetry, indicating reduced cortical activity and greater left hemisphere activity, which may serve as predictors of favorable response to selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRI) treatment in major depressive disorder.45 The Antidepressant Treatment Response biomarker, a neurophysiologic biomarker that predicts antidepressant treatment outcomes by analyzing EEG features from the frontal brain regions before and after 1 week of treatment, has demonstrated its potential in predicting both the likelihood and speed of achieving sustained remission during 13 weeks of escitalopram treatment in patients with unipolar major depression.46 In SCZ, EEG markers such as mismatch negativity (MMN) and P300 event-related potentials (ERPs) have been proposed as indicators of cognitive dysfunction and disease progression. MMN, a component of the auditory ERP, reflects automatic sensory processing deficits and has been consistently found to be reduced in SCZ, correlating with cognitive impairment and functional outcomes.47 Similarly, a reduction in the amplitude of the P300 component has been linked to impaired attentional processing and working memory deficits in SCZ.48 These findings support the utility of EEG as a stratification tool to identify subgroups of patients with distinct neurophysiological profiles. More recently, Najafzadeh et al.49 applied adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system classification to resting-state EEG signals and demonstrated near-perfect accuracy in distinguishing SCZ patients from healthy controls. Their analysis identified specific EEG features, such as alpha activity in the occipital region and theta and delta activity in frontal regions, as critical discriminatory markers. Similarly, Kim et al.50 investigated EEG microstate features and found that they provided superior classification accuracy compared to conventional EEG features. Electroencephalography-based biomarkers have been also investigated as predictors of antipsychotic response, with several studies focusing on oscillatory activity, connectivity patterns, and machine learning approaches. A relatively recent systematic review51highlighted reduced alpha power and increased theta activity to be associated with poor treatment response, while specific connectivity alterations, particularly in frontotemporal regions, may differentiate responders from non-responders. Additionally, machine learning models incorporating EEG features have shown the potential in predicting treatment outcomes with moderate accuracy.51

Protein Biomarkers

Recent advancements in biomarker research highlight the role of proteins in precision psychiatry, particularly in neuroplasticity, immune responses, and neurotransmission. Although still far from clinical utility, examples of proteins such as interleukin (IL)-2, S100B, and NfL are promising diagnostic and treatment tools.

A recent phase II trial explored low-dose IL-2 as an add-on to standard antidepressants in treating major depressive disorder and bipolar disorder (BD), providing evidence for this combination therapy.52 Interleukin 2 treatment expanded Tregs, Th2, and naïve CD4+/CD8 + cells, with early immune shifts predicting depression improvement. Patients receiving IL-2 showed sustained symptom reduction and a lower relapse risk.53 Interleukin 2 may also support neuroplasticity, potentially via the PI3K-GSK-3β pathway.54,55 Immune-modulating approaches, especially targeting T cells, could be valuable for MDD and BD, refining treatment selection and enhancing personalized care.

Further, 100 calcium-binding protein B (S100B), primarily secreted by astrocytes, indicates glial activation and blood-brain barrier integrity.56 Elevated S100B levels have been observed in SCZ, MDD, BD, autism spectrum disorder, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, though findings remain inconsistent.57 Elevated S100B levels are linked to better responses to antidepressants in MDD.58,59 In SCZ, S100B levels were higher in drug-naïve patients, suggesting a link between glial activation and treatment effects.60 These findings support S100B as a promising biomarker for predicting treatment response, though its neuroprotective roles warrant further study.

Neurofilament light chain (NfL), a marker of neuroaxonal injuries,61 has been studied in various psychiatric disorders. Elevated NfL levels in psychiatric disorders, such as 1.2 to 2.5 times higher than normative values, reflect active biological processes but lack specificity for particular diagnoses.62 In SCZ, elevated NfL levels correlate with worse outcomes, while decreased NfL post-treatment does not relate to antipsychotic dosage.63 The potential of NfL as a state-dependent biomarker could enhance patient stratification and monitoring.64 The strong correlation between blood and cerebrospinal fluid measurements65 positions it as a promising biomarker in psychiatric practice.

In conclusion, examples of proteins like IL-2, S100B, and NfL, hold promise for precision psychiatry, offering insights into immune responses, neuroplasticity, and neurodegeneration. With further research and advancements in proteomics, these biomarkers could lead to more tailored and effective treatments in clinical practice.

Immunology

It is well documented that chronic inflammation plays a pivotal role in the pathogenesis and perpetuation of various mental illnesses,66,67 raising the transdiagnostic relevance of the immune system in mental illness. It is important to emphasize that this concerns a specific group of patients66 rather than all. In particular, stress-associated psychiatric disorders (for example, anxiety and depression) are associated with systemic inflammation, especially with monocytosis, neutrophilia, lymphocytopenia, and an upregulation of proinflammatory processes in peripheral areas.68 The current research focus is on inflammatory processes, particularly in the context of MDD, SCZ, and BD; however, there is still comparatively little knowledge about other diseases.67

Current Immune Markers Across Psychiatric Disorders

It is well documented that aberrant cytokine levels occur in major psychiatric disorders, including MDD, SCZ, and BD. These levels are observed both in the acute phase and in the chronic course of the illness. In particular, IL-6, tumor necrosis factor alpha, and high-sensitive C-reactive protein levels are elevated transdiagnostically66-69 in the acute phases of major psychiatric disorders. Furthermore, IL-6 is also elevated transdiagnostically in the chronic course of these illnesses. Interleukin-1β appears to be transdiagnostically decreased in the acute and chronic phases of illness.66,67,69 Interleukin 8 demonstrates disorder-specific effects, suggesting that it could be employed as a biomarker for differential diagnosis and specific treatments. The lymphocyte and monocyte system also appear to be crucial in pathophysiology. The presence of monocytosis, neutrophilia, and lymphocytopenia is characteristic of depressive disorders.68 In bipolar samples, there is evidence of imbalanced ratios and an altered function of T helper (Th) 1, Th2, Th17 cells, and regulatory T cells.68 Additionally, SCZ patients exhibit increased lymphocyte and monocyte levels.70

Immunomodulation Induced by Various Biological Systems

More recent studies have concentrated on the complement system, abnormalities in the blood-brain barrier, and the gut-brain axis involving the vagus nerve and the kynurenine pathway (KP), particularly in the context of MDD and SCZ.71 The bidirectional gut-brain axis is of particular importance in the context of depressive disorders and offers potential for the development of new treatments.72,73 It seems that there is a reciprocal interaction between stress and the microbiome. The microbiome has also been observed to activate the immune response in the gut following stress and may potentially contribute to the development of depression-like states. Additionally, there is evidence suggesting an association between the microbiome and other psychiatric disorders, including SCZ, BD, and anxiety disorders.74 In the field of BD, Jones et al.75 identified purinergic, mitochondrial, inflammatory, immune, kynurenine, and hormonal pathways as significant inflammatory mediators in their review. The authors describe a dynamic and multi-layered field of research, which shows developments in many different directions. While the fundamentals have already been investigated to a considerable extent, the findings remain heterogeneous, and the translation of this knowledge into practice is still in its infancy. Earlier characterization of patients regarding their inflammatory state and specific interventions that address individual immune abnormalities represent promising avenues for therapeutic intervention. It has been demonstrated that established forms of treatment, including antidepressants, antipsychotics, lithium, and ketamine, exert an influence on immunological processes that are pertinent to the etiology of mental illness. Additionally, exercise and dietary modifications have been identified as promising interventions. Further research is required in the area of nutritional supplements in order to make reliable recommendations.

The current evidence base on specific immunomodulatory substances does not yet allow for any specific recommendations to be made in clinical practice. However, in the context of depression, Simon et al.76proposed that celecoxib should be given precedence over minocycline and omega-3 fatty acids. As a caution, they also emphasize that no definitive clinical recommendation can yet be made. Xu et al.77 proposed the concomitant administration of N-acetylcysteine (NAC) for the treatment of BD. Furthermore, Fond et al.78 recommend NAC and polyunsaturated fatty acids for treating SCZ.

Taken together, more and more immune signatures across the adaptive and innate immune system have been discovered in the recent past which points to an immunological underpinning of major psychiatric disorders in a transdiagnostic way. Moreover, treatments have been investigated for clinical usefulness in terms of efficacy and safety with much development underway in clinical studies. Both markers of the immune system and treatments targeting the immune system are suggestive that immune targets and biomarkers could play a role in Personalized Psychiatry. Patients with such immune signatures and suitability for immune-targeting treatments could present a subgroup that may be identified for such personalized treatment approaches.

The Kynurenine Pathway of Tryptophan Metabolism

The KP is a key metabolic route of tryptophan degradation linked to the pathophysiology of various psychiatric disorders.79,80 We have previously discussed the intricate roles of stress and inflammation in the pathophysiology of various psychiatric disorders, highlighting their significant contributions to clinical symptoms, manifestations, and neuropsychopharmacology. In this context, KP metabolites emerge as pivotal intermediaries at the intersection of these critical factors.79,80 Dysregulation of the KP, which encompasses the metabolism of tryptophan to kynurenine and its downstream metabolites, has been implicated in the modulation of neuroinflammation and stress response. Kynurenine pathway metabolites, including kynurenine, kynurenic acid, and quinolinic acid, influence neuroinflammation, neurotransmitter systems, and neuronal excitability.79-81 Dysregulated KP activity reflects inflammatory and stress-related processes, contributing to psychiatric symptoms and offering potential biomarkers for disease severity and treatment response, thereby enhancing the precision of personalized interventions.

A meta-analysis revealed altered KP metabolites across MDD, BD, and SCZ, including reduced tryptophan, elevated kynurenine-to-tryptophan ratios, and distinct metabolite patterns.82 Mood disorders show reduced kynurenic acid, while SCZ displays unchanged peripheral kynurenic and quinolinic acid levels.82 Notably, the potential influence of demographic factors, such as age and sex, particularly in BD, on KP metabolites, was highlighted. Given the significant heterogeneity in the data, future research should focus on identifying sub-populations more susceptible to alterations in the KP, paving the way for precision medicine approaches in the treatment of these mental disorders. In an exploratory study in BD, higher kynurenine and quinolinic acid levels correlate with poor lithium response as measured by the Alda scale,83 and in MDD, reduced kynurenic acid predicts better escitalopram response.84 These findings underscore the relevance of KP metabolites, particularly KYNA, in personalized treatment.

In SCZ, treatment-resistant cases exhibited heightened KP activity compared to first-line responders. The kynurenic acid/quinolinic acid ratio correlated with symptom severity in first-line responders but not in treatment-resistant cases, suggesting intrinsic NMDA receptor dysfunction in the latter group, potentially addressed by clozapine.85 This indicates the potential of KP metabolites as biomarkers for SCZ treatment response, promoting the need for SCZ classification based on biological profiles. Such biomarker-driven classification could guide targeted treatments and help refine the pharmacological approaches for personalized management in SCZ, particularly for the treatment-resistant form, where NMDA receptor-targeted therapies may hold promise.

Kynurenine pathway dysregulation also plays a role in comorbidities like aggression, suicidal behaviors, cognitive impairments, pain, and metabolic disturbances, as explored in other reviews.79,80,86-90

Emerging evidence highlights the influence of gut microbiota on the KP, with significant implications for mood and behavior.86,91 Altered microbiota profiles in SCZ correlate with disruptions in gamma aminobutyric acid (GABA) and tryptophan metabolism, linking these changes to clinical symptoms and cognitive impairments.92 Gut microbiota diversity also predicts treatment response in depression, emphasizing the interplay between inflammation, microbiota, and the KP in shaping psychiatric outcomes.93,94 Understanding these dynamics could inform novel interventions, including microbiota-targeted therapies and psychedelics, although the evidence is still limited.86

Circadian Rhythms

The circadian system regulates critical biological processes, including the sleep-wake cycle, hormone secretion, and brain activity, all influencing mood and behavior.95-98 Sleep-circadian disturbances are common across psychiatric disorders, suggesting circadian dysregulation as a transdiagnostic phenomenon and a predictor of psychopathology.98-104 For instance, circadian disturbances in youth seeking early intervention predict progression to mood, anxiety, or psychotic disorders.105 In BD, eveningness preference and disrupted social rhythms characterize at-risk individuals and those with early-stage illness, with preexisting circadian disturbances increasing the risk of BD onset by 40%.101,106 On the other hand, these findings offer tentative support for views that circadian dysrhythmias may play a role in the development of BD and act as triggers for mood episodes.96,107 However, the relationship between circadian disruptions and mood disorders remains unclear. It is uncertain whether circadian disruptions predispose individuals to mood disorders, arise due to them, or share underlying physiological mechanisms.98,99

The circadian system is increasingly recognized as a key target for personalized treatments in mood disorders, with evidence linking circadian dysfunction to poor clinical outcomes, including heightened depressive severity and misaligned rhythms.102,108 Evening chronotype, in particular, has been associated with worse symptom severity, suicidality, and treatment resistance in MDD, as well as more severe clinical features and comorbidities in BD.109-111

Sleep disturbances in BD are pervasive including insomnia, hypersomnia, reduced need for sleep, and irregular sleep schedules.112,113 Circadian rhythm dysfunctions, such as irregular sleep-wake cycles, eveningness chronotype, and abnormal melatonin secretion, are prominent in BD and may serve as state and trait markers.106,107 These disruptions are linked to poorer quality of life, heightened suicide risk, and impaired cognitive function.114 Manic states are associated with circadian abnormalities, including advanced circadian phases and increased melatonin secretion.115,116 Notably, circadian activity rhythms correlate with mood episode relapses.107,117,118 Poor sleep quality and disturbances during euthymia predict worse residual symptoms and earlier mood episode recurrence, even after adjusting for baseline mood symptoms.119 Clinically, individuals with an evening chronotype exhibit more severe symptoms, earlier onset, and more comorbidities, including anxiety and substance use disorders, as well as increased rapid cycling and prior suicide attempts.104,120 An 18-month prospective study of euthymic BD patients linked evening chronotype to worse anxiety and increased mood episodes, suggesting a poor prognosis.106 Evening chronotype is also associated with disordered eating behaviors, including binge eating, bulimia, nocturnal eating, and unhealthy dietary patterns, alongside higher body mass index (BMI) and lower scores on healthy eating scales.121 This indicates the role of circadian dysfunction in dietary behaviors observed in BD. Additionally, the evening chronotype correlates with higher rates of hypertension, migraine, asthma, and obstructive sleep apnea.120

Circadian rhythm dysfunctions may predict mood disorders and episode relapses. Treatments targeting sleep disturbances and circadian rhythm dysfunction—combined with pharmacological, psychosocial, and chronobiological approaches—effectively prevent relapse.122 The molecular circadian clock, regulating sleep-wake cycles, is often dysfunctional in mood disorders. Genetic polymorphisms in circadian genes influence susceptibility and treatment responses. Lithium, a circadian synchronizer, shows greater efficacy in BD patients with morning chronotypes and may shift circadian phases.106,123-125 Many mood stabilizers affect circadian rhythms, with phase-advancing interventions potentially benefiting bipolar depression and phase-delaying effects alleviating mania, though evidence in humans is limited.126 Advancements in neuroimaging and computational approaches are identifying subtypes of sleep impairment and brain circuit dysfunctions, enabling personalized interventions. Disrupted networks, such as the default mode and negative affective networks, provide potential targets.3 Pharmacological treatments like orexin antagonists and melatonergic agonists, alongside chronotherapeutic approaches—including bright light therapy, dark therapy, sleep deprivation strategies, and behavioral interventions like cognitive behavioral therapy for insomnia tailored to bipolar disorders and interpersonal social rhythm therapy—are extensively used.127 Emerging therapies addressing inflammation, the gut-brain axis, antioxidants, the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA) axis, and synaptic modulation offer new potential for managing the interplay of sleep, circadian rhythms, and mood disorders.128 Digital phenotyping and wearable technologies further enhance the precision of interventions.3 Future research should evaluate the circadian effects of medications, refine treatment subtypes, and integrate chronobiology into study designs to maximize translational impact.

Genomics

The advent of genome-wide analysis (GWAS) has significantly changed the landscape of diagnosis and treatment of psychiatric disorders.129 Genome-wide analysis studies provide insights under the common disease-common variant framework by identifying single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with traits (eg, diagnosis, treatment response, psychometric measures). Although associated SNPs may not be direct risk variants, instead, in linkage disequilibrium with them, GWAS highlights genomic regions essential for refining the genetic architecture.129 These studies have confirmed the polygenicity of psychiatric disorders, revealed pleiotropy (where one gene influences multiple traits), and facilitated risk stratification using polygenic risk scores (PRS).2,130 Despite gaps in integrating genetic findings into neurobiological,2 genomic data inform prediction tools for precision psychiatry, particularly in multimodal modeling.131 Genomic data integration is becoming increasingly valuable in precision psychiatry, particularly in diagnostic processes, risk prediction, and treatment response.

Although clinical utility remains limited,132 genomic research is beginning to influence psychiatric diagnostics.133 Polygenic risk scores are particularly useful for stratifying individuals based on their genetic risk of developing psychiatric disorders. Still, they are more effective when incorporated into multimodal models that consider other risk factors.134 Recent studies suggest that psychiatric disorders may be classified using genomic data.135 Specifically, this systematic review found strong correlations (88.6%) between disorders based on SNPs, gene expression, and neuroimaging, with a significant portion of diagnostic overlap attributed to genomic factors.135 Another study using data from a large Danish population cohort from the Integrative Psychiatric Research Consortium predicted psychiatric diagnoses with good accuracy, especially for severe disorders like SCZ.136 Additionally, genetic associations between psychotic disorders and cannabis use have been explored, revealing that PRS for cannabis phenotypes improved predictions for psychotic disorders.137

Regarding treatment response, traits related to pharmacological responses, such as lithium response, are heritable and polygenic.138 Genome-wide analysis has identified association signals linked to favorable lithium response,139-141 and analyses suggest that PRS for SCZ and MDD are linked to poorer lithium response.142 Genomic data have also been used to classify patients with BD as responders or non-responders to lithium, with promising results when restricting analysis to a prospectively followed cohort.143 However, genomic data were not able to reliably distinguish clinical examples of lithium responders and non-responders.144 Promising results have been reported also for MDD145 and SCZ.146

In high-risk populations, PRS for BD were found to be elevated in youth with BD,147 and applying this PRS to a validated risk calculator improved diagnostic performance in a high-risk cohort.148

The use of cytochrome P450 (CYP) gene variants, particularly CYP2D6, CYP2D19, and CYP3A4/5, is probably the most established genetic tool for optimizing pharmacotherapy within precision psychiatry. These enzymes are responsible for metabolizing a substantial proportion of psychotropic drugs, with CYP2D6 and CYP2D19 playing a central role in the metabolism of several antipsychotics and antidepressants. Genetic polymorphisms can lead to wide interindividual variability in metabolic activity, ranging from poor to ultrarapid metabolizers, thereby impacting plasma drug levels, therapeutic response, and side-effect profiles.25 The food and drug administration (FDA) and european medicines agency (EMA) have integrated pharmacogenetic information into drug labels for many psychotropics, though formal requirements for testing remain limited.149,150 CYP2D6 genotyping is especially relevant when dose-dependent toxicity is a concern, as in the case of pimozide, where testing is required above specific dose thresholds. However, the clinical utility of genotyping is complicated by phenoconversion, when enzyme activity is altered by co-administered drugs, potentially overriding genetic predictions.26 Additionally, other genes like NFIB have been shown to modulate CYP2D6 expression and influence drug metabolism independently of genotype.151 While CYP3A4 and CYP3A5 also contribute to the metabolism of antipsychotics such as quetiapine and loxapine, their functional impact is often modulated by environmental factors and less directly linked to actionable genotype information. The major guidelines (Clinical Pharmacogenetics Implementation Consortium, Dutch Pharmacogenetics Working Group) offer pharmacogenetic-informed dosing recommendations, but widespread implementation in psychiatry is hampered by limited evidence on clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness.152-154 Overall, CYP genotyping provides valuable pharmacokinetic insight, particularly in difficult-to-treat patients, but should be interpreted in conjunction with TDM and clinical assessment to ensure optimal, individualized treatment decisions25

In summary, advancing genomic approaches for diagnostic and predictive purposes in psychiatry is promising, pointing to clinical implementation of precision psychiatry, similar to other fields of medicine.155

CONCLUSIONS

This review provides an integrated overview of precision psychiatry, illustrating advancements across multiple domains and offering examples from various fields. This aligns with the growing initiatives of collaborative research, such as the CINP GNC Precision Psychiatry, to drive the field forward. The evidence presented (Table 1) underscores the complexity of psychiatric disorders and highlights progress in clinical phenotyping, symptom-based approaches, neuroimaging, protein biomarkers, immunological markers, genomic analyses, gut microbiome interactions, and circadian rhythm assessments. Each area contributes valuable insights for more accurate prediction, prevention, and intervention strategies.

Table 1.

Selected biomarkers and their potential applications in precision psychiatry.

| Domain | Potential biomarkers | Application in precision psychiatry |

|---|---|---|

| Neuroimaging | MRI, fMRI, PET parameters | Identifies structural and functional abnormalities, predicts treatment response, and aids patient stratification. |

| Neurophysiology | EEG | Transdiagnostic outcome predictors and classification biomarkers. |

| Protein biomarkers | IL-2, S100B, NfL | Tracks neuroinflammation, glial activation, and neuroaxonal injury; monitors treatment effects and prognosis. |

| Genetics | GWAS, polygenic scores, SNPs | Predicts susceptibility, aids diagnosis, and guides pharmacogenomics-based treatment selection. |

| Epigenetics | DNA methylation, histone modifications, non-coding RNAs | Explores gene-environment interactions, stress responses, and susceptibility to mood and sleep disturbances. |

| Circadian rhythms | Chronotypes, melatonin, sleep-wake patterns | Targets circadian disruptions for mood stabilization, relapse prevention, and treatment timing optimization. |

| Kynurenine pathway | Kynurenic acid, quinolinic acid, and other tryptophan metabolites | Biomarkers for inflammation, neurotransmitter imbalance, stress response, and treatment resistance. |

| Gut-brain axis | Microbiome profiles, metabolomics, gut-derived neuroactive compounds | Links gut microbiota to inflammation, mood regulation, and psychiatric symptomatology; explores probiotic therapy. |

| Clinical symptomatology | Symptom-based clustering, drug tolerability profiles | Matches treatment options with individual profiles, improving precision in pharmacological and psychotherapeutic care. |

| Digital phenotyping | Continuous monitoring of daily activity, mood, and physiological parameters via wearables or smartphone-based apps | Captures real-time behavioral data, improves phenotyping, and monitors treatment response dynamically. |

Abbreviations: EEG, electroencephalography; fMRI, functional magnetic resonance imaging; GWAS, genome-wide analysis; PET, positron emission tomography; SNPs, single nucleotide polymorphisms.

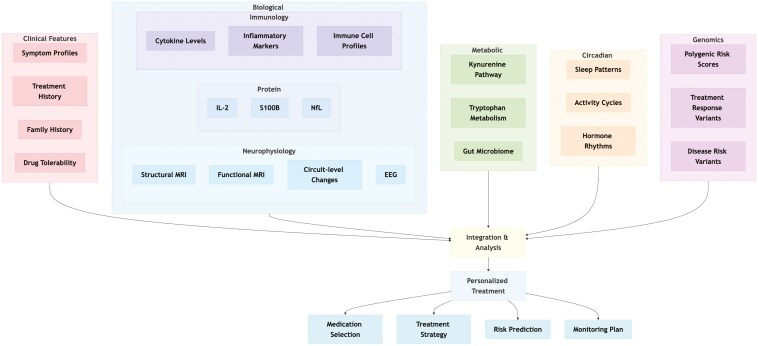

A key message emerging from the review is that no single marker or modality can fully capture the intricate nature of psychiatric conditions. Instead, a multidisciplinary and multimodal approach is essential (Figure 1). For instance, neuroimaging studies have revealed potential biotypes and subgroups of patients with distinct brain structure and connectivity patterns, which challenge traditional diagnostic categories and suggest that circuit-based phenotypes could predict treatment responses to interventions such as TMS or novel therapies. Although some challenges are still present, including standardization of protocols, replication of findings across diverse populations, and integration with multimodal data, EEG biomarkers represent one promising tool for moving precision psychiatry into clinical practice. In particular, alterations in oscillatory activity and connectivity, such as reduced alpha power and increased theta activity, have been linked to poor treatment response, while machine learning approaches incorporating EEG features have shown improved potential in predicting clinical outcomes.

Figure 1.

Integrated framework for precision psychiatry across key domains. This conceptual diagram illustrates the multifaceted approach to precision psychiatry, highlighting the six main domains that contribute to personalized treatment strategies. Clinical features (pink), biological markers (blue) including neurophysiology, protein biomarkers, and immunology, metabolic pathways (green), circadian rhythms (orange), and genomics (purple) all converge in an integrative analysis that informs personalized treatment decisions. These treatment recommendations can be categorized into medication selection, treatment strategy, risk prediction, and monitoring plans.

Similarly, research into protein biomarkers like IL-2, S100B, and NfL highlights the potential of molecular signals for guiding treatment selection and prognosis. While these protein markers have not yet achieved widespread clinical utility, further validation could enable their integration with clinical data to inform treatment decisions.

Additionally, immune processes and dysregulated metabolic pathways, such as the KP, deepen our understanding of the biological dynamics underlying psychiatric disorders. Immune-based treatments, such as those targeting IL-2, indicate the feasibility of addressing specific inflammatory processes. At the same time, alterations in tryptophan metabolites highlight how neuroinflammation and excitatory-inhibitory imbalances may influence treatment outcomes. These findings show the need to move beyond traditional neurotransmitter-based hypotheses.

Circadian rhythm disturbances and sleep impairments add another layer to this complex picture. Their transdiagnostic nature and association with treatment response suggest that interventions like light therapy, chronotherapy, and tailored pharmacological agents could effectively complement the management of mood disorders.

Genomic insights, driven by large-scale genome-wide association studies, are revealing the polygenic and pleiotropic nature of psychiatric disorders. Although genomic data are primarily a research tool, they have significant potential to improve risk stratification, inform pharmacological choices, and eventually contribute to refined diagnostic classifications when combined with other biomarkers and environmental factors.

Precision psychiatry does not represent a single breakthrough but rather a convergence of multiple research fields.2-4,31,131,156-160 However, reliance on biomarkers only may be misleading in specific cases.161 By integrating clinical features, neuroimaging, proteomics, immunology, microbiome research, chronobiology, and genomics into a comprehensive analytic framework, and by leveraging advances in computational modeling and machine learning, precision psychiatry is poised to transform clinical practice. While numerous challenges remain, including replication, scalability, ethical considerations, and patient acceptability, the progress offers an encouraging perspective for improving routine clinical care.

Acknowledgments

Bernhard T. Baune and Alessandro Serretti received support from Psych-STRATA, a project funded from the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation program under Grant Agreement No. 101057454.

Contributor Information

Stefano Comai, Department of Pharmaceutical and Pharmacological Sciences, University of Padua, Padua, Italy; Department of Biomedical Sciences, University of Padua, Padua, Italy; Department of Psychiatry, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada; IRCSS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy.

Mirko Manchia, Unit of Psychiatry, Department of Medical Sciences and Public Health, University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy; Department of Pharmacology, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Nova Scotia, Canada.

Marta Bosia, IRCSS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy.

Alessandro Miola, Department of Neuroscience, University of Padova, Padua, Italy.

Sara Poletti, IRCSS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy.

Francesco Benedetti, IRCSS San Raffaele Scientific Institute, Milan, Italy.

Sofia Nasini, Department of Pharmaceutical and Pharmacological Sciences, University of Padua, Padua, Italy.

Raffaele Ferri, Oasi Research Institute-IRCCS, Troina, Italy.

Dan Rujescu, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, Medical University Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Marion Leboyer, Université Paris-Est Créteil (UPEC), Translational Neuropsychiatry Laboratory (INSERM U955 IMRB), Département de Psychiatrie (DMU IMPACT, AP-HP, Hôpital Henri Mondor), Fondation FondaMental, ECNP Immuno-NeuroPsychiatry Network, 94010 Créteil, France.

Julio Licinio, SUNY Upstate Medical University, Syracuse, NY, United States.

Bernhard T Baune, Department of Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, University of Münster, Münster, Germany; Department of Psychiatry, Melbourne Medical School, University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia; The Florey Institute of Neuroscience and Mental Health, The University of Melbourne, Parkville, VIC, Australia.

Alessandro Serretti, Oasi Research Institute-IRCCS, Troina, Italy; Department of Medicine and surgery, Kore University of Enna, Enna, Italy.

Author contributions

Marta Bosia (Conceptualization [equal], Methodology [equal], Project administration [equal], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Alessandro Miola (Conceptualization [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Sofia Nasini (Methodology [equal], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Julio Licinio (Conceptualization [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Bernhard T. Baune (Conceptualization [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Alessandro Serretti (Conceptualization [lead], Methodology [lead], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [lead]), Stefano Comai (Conceptualization [equal], Methodology [equal], Supervision [equal], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Mirko Manchia (Conceptualization [equal], Data curation [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Sara Poletti (Conceptualization [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Francesco Benedetti (Conceptualization [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Raffaele Ferri (Conceptualization [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), Dan Rujescu (Methodology [equal], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal]), and Marion Leboyer (Conceptualization [equal], Methodology [equal], Writing—original draft [equal], Writing—review & editing [equal])

Funding

None declared.

Conflicts of interest

A.S. is or has been a consultant to or has received honoraria or grants unrelated to the present work from: Abbott, AbbVie, Angelini, Astra Zeneca, Clinical Data, Boheringer, Bristol Myers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GlaxoSmithKline, Innova Pharma, Italfarmaco, Janssen, Lundbeck, Naurex, Pfizer, Polifarma, Sanofi, Servier, Taliaz. B.B. received honoraria for serving as a consultant or on advisory boards unrelated to the present work for Angelini, AstraZeneca, Biogen, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Janssen, LivaNova, Lundbeck, Medscape, Neurotorium, Novartis, Otsuka, Pfizer, Recordati, Roche, Rovi, Sanofi, Servier, Teva. D.R. served as a consultant for Janssen, received honoraria from Gerot-Lannacher, Janssen, and Pharmagenetix, received travel support from Angelini and Janssen, and served on advisory boards of AC Immune, Roche, and Rovi. S.C. has received grant support from MGGM LLC, and consultant fees from Neuroarbor LLC and MGGM LLC, companies affiliated with Relmada Therapeutics, and from Dompè farmaceutici S.p.A. M.M. has received honoraria unrelated to the present work from Angelini, Lundbeck, Fidia, Rovi, Viatris, Johnson and Johnson.

The remaining authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

Data availability

No data are reported.

References

- 1. Serretti A. Precision psychiatry. Braz J Psychiatry. 2022;44:115–116. https://doi.org/ 10.1590/1516-4446-2021-1997 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Gandal MJ, Leppa V, Won H, Parikshak NN, Geschwind DH.. The road to precision psychiatry: translating genetics into disease mechanisms. Nat Neurosci. 2016;19:1397–1407. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nn.4409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Goldstein-Piekarski AN, Holt-Gosselin B, O’Hora K, Williams LM.. Integrating sleep, neuroimaging, and computational approaches for precision psychiatry. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2020;45:192–204. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41386-019-0483-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Fernandes BS, Williams LM, Steiner J, et al. The new field of “precision psychiatry.”. BMC Med. 2017;15:80. https://doi.org/ 10.1186/s12916-017-0849-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Serretti A. The interplay of psychopharmacology and medical conditions. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2023;38:365–368. https://doi.org/ 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Collins FS, Varmus H.. A new initiative on precision medicine. N Engl J Med. 2015;372:793–795. https://doi.org/ 10.1056/NEJMp1500523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Trubetskoy V, Pardiñas AF, Qi T, et al. Indonesia Schizophrenia Consortium Mapping genomic loci implicates genes and synaptic biology in schizophrenia. Nature. 2022;604:502–508. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41586-022-04434-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Ching CRK, Hibar DP, Gurholt TP, et al. ENIGMA Bipolar Disorder Working Group What we learn about bipolar disorder from large-scale neuroimaging: findings and future directions from the ENIGMA Bipolar Disorder Working Group. Hum Brain Mapp. 2022;43:56–82. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/hbm.25098 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Fabbri C, Mutz J, Lewis CM, Serretti A.. Stratification of individuals with lifetime depression and low wellbeing in the UK Biobank. J Affect Disord. 2022;314:281–292. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jad.2022.07.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Electronic address: andrew.mcintosh@ed.ac.uk, Major Depressive Disorder Working Group of the Psychiatric Genomics Consortium. Trans-ancestry genome-wide study of depression identifies 697 associations implicating cell types and pharmacotherapies. Cell. 2025;188:640– 652. . https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.cell.2024.12.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Kas MJH, Jongs N, Mennes M, et al. Digital behavioural signatures reveal trans-diagnostic clusters of schizophrenia and Alzheimer’s disease patients. Eur Neuropsychopharmacol. 2024;78:3–12. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.euroneuro.2023.09.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Taliaz D, Serretti A.. Investigation of psychoactive medications: challenges and a practical and scalable new path. CNS Neurol Disord Drug Targets. 2022;22:1267–1274. https://doi.org/ 10.2174/1871527321666220628103843 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Sealock JM, Tubbs JD, Lake AM, et al. Cross-EHR validation of antidepressant response algorithm and links with genetics of psychiatric traits. medRxiv. 2024:2024.09.11.24313478. https://doi.org/ 10.1101/2024.09.11.24313478 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Serretti A. The Present and future of precision medicine in psychiatry: focus on clinical psychopharmacology of antidepressants. Clin Psychopharmacol Neurosci. 2018;16:1–6. https://doi.org/ 10.9758/cpn.2018.16.1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Esposito CM, Barkin JL, Ceresa A, Buoli M.. Does the comorbidity of borderline personality disorder affect the response to treatment in bipolar patients? Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2024;39:51–58. https://doi.org/ 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000489 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Yatham LN, Kennedy SH, Parikh SV, et al. Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) and International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) 2018 guidelines for the management of patients with bipolar disorder. Bipolar Disord. 2018;20:97–170. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/bdi.12609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Kennedy SH, Lam RW, McIntyre RS, et al. CANMAT Depression Work Group Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) 2016 Clinical Guidelines for the management of adults with major depressive disorder: section 3. pharmacological treatments. Can J Psychiatry. 2016;61:540–560. https://doi.org/ 10.1177/0706743716659417 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Taylor DM, Barnes TRE, Young AH.. The Maudsley Prescribing Guidelines in Psychiatry. John Wiley & Sons; 2021. https://play.google.com/store/books/details?id=QGM4EAAAQBAJ [Google Scholar]

- 19. Fried EI, Nesse RM.. Depression is not a consistent syndrome: an investigation of unique symptom patterns in the STAR*D study. J Affect Disord. 2015;172:96–102. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jad.2014.10.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chekroud AM, Gueorguieva R, Krumholz HM, et al. Reevaluating the efficacy and predictability of antidepressant treatments: a symptom clustering approach. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017;74:370–378. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0025 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Murawiec S, Krzystanek M.. Symptom cluster-matching antidepressant treatment: a case series pilot study. Pharmaceuticals (Basel). 2021;14:526. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/ph14060526 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Masand PS. Tolerability and adherence issues in antidepressant therapy. Clin Ther. 2003;25:2289–2304. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/s0149-2918(03)80220-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Franchini L, Serretti A, Gasperini M, Smeraldi E.. Familial concordance of fluvoxamine response as a tool for differentiating mood disorder pedigrees. J Psychiatr Res. 1998;32:255–259. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/S0022-3956(98)00004-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Serretti A. Modulating factors in mood disorders treatment. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2024;39:47–50. https://doi.org/ 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000534 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hiemke C, Bergemann N, Clement HW, et al. Consensus guidelines for therapeutic drug monitoring in neuropsychopharmacology: update 2017. Pharmacopsychiatry. 2018;51:e1. https://doi.org/ 10.1055/s-0037-1600991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Hart XM, Gründer G, Ansermot N, et al. Optimisation of pharmacotherapy in psychiatry through therapeutic drug monitoring, molecular brain imaging and pharmacogenetic tests: focus on antipsychotics. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2024;25:451–536. https://doi.org/ 10.1080/15622975.2024.2366235 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cellini L, De Donatis D, Zernig G, et al. Antidepressant efficacy is correlated with plasma levels: mega-analysis and further evidence. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2022;37:29–37. https://doi.org/ 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000386 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Kautzky A, Dold M, Bartova L, et al. Refining prediction in treatment-resistant depression: results of machine learning analyses in the TRD III sample. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79:16m11385. https://doi.org/ 10.4088/JCP.16m11385 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Goh E, Gallo R, Hom J, et al. Large language model influence on diagnostic reasoning: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2440969. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.40969 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Chen D, Huang RS, Jomy J, et al. Performance of multimodal artificial intelligence chatbots evaluated on clinical oncology cases. JAMA Netw Open. 2024;7:e2437711. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2024.37711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Baune BT, Minelli A, Carpiniello B, et al. An integrated precision medicine approach in major depressive disorder: a study protocol to create a new algorithm for the prediction of treatment response. Front Psychiatry. 2023;14:1279688. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fpsyt.2023.1279688 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Clementz BA, Sweeney JA, Hamm JP, et al. Identification of distinct psychosis biotypes using brain-based biomarkers. Am J Psychiatry. 2016;173:373–384. https://doi.org/ 10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.14091200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Drysdale AT, Grosenick L, Downar J, et al. Resting-state connectivity biomarkers define neurophysiological subtypes of depression. Nat Med. 2017;23:28–38. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nm.4246 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Tozzi L, Zhang X, Pines A, et al. Personalized brain circuit scores identify clinically distinct biotypes in depression and anxiety. Nat Med. 2024;30:2076–2087. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41591-024-03057-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Aydin O, Unal Aydin P, Arslan A.. Development of neuroimaging-based biomarkers in psychiatry. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2019;1192:159–195. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/978-981-32-9721-0_9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Guimond S, Gu F, Shannon H, et al. A diagnosis and Biotype comparison across the psychosis spectrum: investigating volume and shape amygdala-hippocampal differences from the B-SNIP study. Schizophr Bull. 2021;47:1706–1717. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/schbul/sbab071 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Wang L, Cheng W, Rolls ET, et al. Association of specific biotypes in patients with Parkinson disease and disease progression. Neurology. 2020;95:e1445–e1460. https://doi.org/ 10.1212/WNL.0000000000010498 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Lynch CJ, Elbau IG, Ng T, et al. Frontostriatal salience network expansion in individuals in depression. Nature. 2024;633:624–633. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41586-024-07805-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Javitt DC, Carter CS, Krystal JH, et al. Utility of imaging-based biomarkers for glutamate-targeted drug development in psychotic disorders: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75:11–19. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.3572 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Krystal AD, Pizzagalli DA, Smoski M, et al. A randomized proof-of-mechanism trial applying the “fast-fail” approach to evaluating κ-opioid antagonism as a treatment for anhedonia. Nat Med. 2020;26:760–768. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41591-020-0806-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. McLoughlin G, Makeig S, Tsuang MT.. In search of biomarkers in psychiatry: EEG-based measures of brain function. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2014;165B:111–121. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/ajmg.b.32208 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Simmatis L, Russo EE, Geraci J, Harmsen IE, Samuel N.. Technical and clinical considerations for electroencephalography-based biomarkers for major depressive disorder. NPJ Ment Health Res. 2023;2:18. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s44184-023-00038-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Jafari M, Sadeghi D, Shoeibi A, et al. Empowering precision medicine: AI-driven schizophrenia diagnosis via EEG signals: a comprehensive review from 2002–2023. Appl Intell. 2024;54:35–79. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s10489-023-05155-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Ranjan R, Sahana BC, Bhandari AK.. Deep learning models for diagnosis of schizophrenia using EEG signals: emerging trends, challenges, and prospects. Arch Comput Methods Eng. 2024;31:2345–2384. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s11831-023-10047-6 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Bruder GE, Sedoruk JP, Stewart JW, et al. Electroencephalographic alpha measures predict therapeutic response to a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor antidepressant: pre- and post-treatment findings. Biol Psychiatry. 2008;63:1171–1177. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biopsych.2007.10.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cook IA, Hunter AM, Gilmer WS, et al. Quantitative electroencephalogram biomarkers for predicting likelihood and speed of achieving sustained remission in major depression: a report from the biomarkers for rapid identification of treatment effectiveness in major depression (BRITE-MD) trial. J Clin Psychiatry. 2013;74:51–56. https://doi.org/ 10.4088/JCP.10m06813 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Light GA, Näätänen R.. Mismatch negativity is a breakthrough biomarker for understanding and treating psychotic disorders. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110:15175–15176. https://doi.org/ 10.1073/pnas.1313287110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Jeon YW, Polich J.. Meta-analysis of P300 and schizophrenia: patients, paradigms, and practical implications. Psychophysiology. 2003;40:684–701. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/1469-8986.00070 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Najafzadeh H, Esmaeili M, Farhang S, Sarbaz Y, Rasta SH.. Automatic classification of schizophrenia patients using resting-state EEG signals. Phys Eng Sci Med. 2021;44:855–870. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s13246-021-01038-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Kim K, Duc NT, Choi M, Lee B.. EEG microstate features for schizophrenia classification. PLoS One. 2021;16:e0251842. https://doi.org/ 10.1371/journal.pone.0251842 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. De Pieri M, Rochas V, Sabe M, Michel C, Kaiser S.. Pharmaco-EEG of antipsychotic treatment response: a systematic review. Schizophrenia (Heidelberg, Germany) 2023;9:85. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41537-023-00419-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Poletti S, Zanardi R, Mandelli A, et al. Low-dose interleukin 2 antidepressant potentiation in unipolar and bipolar depression: safety, efficacy, and immunological biomarkers. Brain Behav Immun. 2024;118:52–68. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.bbi.2024.02.019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Sforzini L, Worrell C, Kose M, et al. A Delphi-method-based consensus guideline for definition of treatment-resistant depression for clinical trials. Mol Psychiatry. 2022;27:1286–1299. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41380-021-01381-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Machado-Vieira R, Soeiro-De-Souza MG, Richards EM, Teixeira AL, Zarate CA Jr. Multiple levels of impaired neural plasticity and cellular resilience in bipolar disorder: developing treatments using an integrated translational approach. World J Biol Psychiatry. 2014;15:84–95. https://doi.org/ 10.3109/15622975.2013.830775 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Manji HK, Quiroz JA, Sporn J, et al. Enhancing neuronal plasticity and cellular resilience to develop novel, improved therapeutics for difficult-to-treat depression. Biol Psychiatry. 2003;53:707–742. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/s0006-3223(03)00117-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Donato R, Cannon BR, Sorci G, et al. Functions of S100 proteins. Curr Mol Med. 2013;13:24–57. https://doi.org/ 10.2174/156652413804486214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kozlowski T, Bargiel W, Grabarczyk M, Skibinska M.. Peripheral S100B protein levels in five major psychiatric disorders: a systematic review. Brain Sci. 2023;13:1334. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/brainsci13091334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ambrée O, Bergink V, Grosse L, et al. S100B serum levels predict treatment response in patients with melancholic depression. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2015;19:pyv103. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/ijnp/pyv103 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Navinés R, Oriolo G, Horrillo I, et al. High S100B levels predict antidepressant response in patients with major depression even when considering inflammatory and metabolic markers. Int J Neuropsychopharmacol. 2022;25:468–478. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/ijnp/pyac016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Zhang XY, Xiu MH, Song C, et al. Increased serum S100B in never-medicated and medicated schizophrenic patients. J Psychiatr Res. 2010;44:1236–1240. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jpsychires.2010.04.023 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Petzold A. Neurofilament phosphoforms: surrogate markers for axonal injury, degeneration and loss. J Neurol Sci. 2005;233:183–198. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jns.2005.03.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Zetterberg H, Skillbäck T, Mattsson N, et al. Alzheimer’s Disease Neuroimaging Initiative Association of cerebrospinal fluid neurofilament light concentration with Alzheimer disease progression. JAMA Neurol. 2016;73:60–67. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamaneurol.2015.3037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Popovic D, Schiltz K, Dobrowolny H, et al. Serum levels of neurofilament light-chain (NfL), a biomarker of axonal and synaptic damage, predict 5-year outcome in acutely ill schizophrenia patients. J. Affect. Disord. Rep. 2023;12:100568. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jadr.2023.100568 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Leckey CA, Coulton JB, Giovannucci TA, et al. CSF neurofilament light chain profiling and quantitation in neurological diseases. Brain Commun. 2024;6:fcae132. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/braincomms/fcae132 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Alagaratnam J, von Widekind S, De Francesco D, et al. Correlation between CSF and blood neurofilament light chain protein: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Neurol Open. 2021;3:e000143. https://doi.org/ 10.1136/bmjno-2021-000143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Goldsmith DR, Rapaport MH, Miller BJ.. A meta-analysis of blood cytokine network alterations in psychiatric patients: comparisons between schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and depression. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:1696–1709. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/mp.2016.3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Zhang Y, Wang J, Ye Y, et al. Peripheral cytokine levels across psychiatric disorders: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2023;125:110740. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2023.110740 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Chan KL, Poller WC, Swirski FK, Russo SJ.. Central regulation of stress-evoked peripheral immune responses. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2023;24:591–604. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41583-023-00729-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Miller BJ, Goldsmith DR.. Evaluating the hypothesis that schizophrenia is an inflammatory disorder. Focus (Am Psychiatr Publ). 2020;18:391–401. https://doi.org/ 10.1176/appi.focus.20200015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Orbe EB, Benros ME.. Immunological biomarkers as predictors of treatment response in psychotic disorders. J Pers Med. 2023;13:1382. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/jpm13091382 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Feng T, Tripathi A, Pillai A.. Inflammatory pathways in psychiatric disorders: the case of schizophrenia and depression. Curr Behav Neurosci Rep. 2020;7:128–138. https://doi.org/ 10.1007/s40473-020-00207-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Borgiani G, Possidente C, Fabbri C, et al. The bidirectional interaction between antidepressants and the gut microbiota: are there implications for treatment response? Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2024;40:3–26. https://doi.org/ 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000533 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Cussotto S, Colle R, David DJ, Corruble E.. When antidepressants meet the gut microbiota: implications and challenges. Int Clin Psychopharmacol. 2025;40:46–48. https://doi.org/ 10.1097/YIC.0000000000000558 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Medina-Rodriguez EM, Cruz AA, De Abreu JC, Beurel E.. Stress, inflammation, microbiome and depression. Pharmacol Biochem Behav. 2023;227-228:173561. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pbb.2023.173561 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. Jones GH, Vecera CM, Pinjari OF, Machado-Vieira R.. Inflammatory signaling mechanisms in bipolar disorder. J Biomed Sci. 2021;28:45. https://doi.org/ 10.1186/s12929-021-00742-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Simon MS, Arteaga-Henríquez G, Fouad Algendy A, Siepmann T, Illigens BMW.. Anti-inflammatory treatment efficacy in major depressive disorder: a systematic review of meta-analyses. Neuropsychiatr Dis Treat. 2023;19:1–25. https://doi.org/ 10.2147/NDT.S385117 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Xu H, Du Y, Wang Q, et al. Comparative efficacy, acceptability, and tolerability of adjunctive anti-inflammatory agents on bipolar disorder: a systemic review and network meta-nalysis. Asian J Psychiatr. 2023;80:103394. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.ajp.2022.103394 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Fond G, Mallet J, Urbach M, et al. Adjunctive agents to antipsychotics in schizophrenia: a systematic umbrella review and recommendations for amino acids, hormonal therapies and anti-inflammatory drugs. BMJ Ment Health. 2023;26:e300771. https://doi.org/ 10.1136/bmjment-2023-300771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Comai S, Bertazzo A, Brughera M, Crotti S.. Tryptophan in health and disease. Adv Clin Chem. 2020;95:165–218. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/bs.acc.2019.08.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Pocivavsek A, Schwarcz R, Erhardt S.. Neuroactive kynurenines as pharmacological targets: new experimental tools and exciting therapeutic opportunities. Pharmacol Rev. 2024;76:978–1008. https://doi.org/ 10.1124/pharmrev.124.000239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. Schwarcz R, Bruno JP, Muchowski PJ, Wu HQ.. Kynurenines in the mammalian brain: when physiology meets pathology. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2012;13:465–477. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nrn3257 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. Marx W, McGuinness AJ, Rocks T, et al. The kynurenine pathway in major depressive disorder, bipolar disorder, and schizophrenia: a meta-analysis of 101 studies. Mol Psychiatry. 2021;26:4158–4178. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41380-020-00951-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Fellendorf FT, Manchia M, Squassina A, et al. Is poor lithium response in individuals with bipolar disorder associated with increased degradation of tryptophan along the kynurenine pathway? Results of an exploratory study. J Clin Med. 2022;11:2517. https://doi.org/ 10.3390/jcm11092517 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Erabi H, Okada G, Shibasaki C, et al. Kynurenic acid is a potential overlapped biomarker between diagnosis and treatment response for depression from metabolome analysis. Sci Rep. 2020;10:16822. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41598-020-73918-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Sapienza J, Agostoni G, Dall’Acqua S, et al. The kynurenine pathway in treatment-resistant schizophrenia at the crossroads between pathophysiology and pharmacotherapy. Schizophr Res. 2024;264:71–80. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.schres.2023.12.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Campanale A, Inserra A, Comai S.. Therapeutic modulation of the kynurenine pathway in severe mental illness and comorbidities: a potential role for serotonergic psychedelics. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2024;134:111058. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2024.111058 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Bryleva EY, Brundin L.. Kynurenine pathway metabolites and suicidality. Neuropharmacology. 2017;112:324–330. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neuropharm.2016.01.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Oxenkrug GF. Metabolic syndrome, age-associated neuroendocrine disorders, and dysregulation of tryptophan-kynurenine metabolism. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2010;1199:1–14. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2009.05356.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Stone TW, Darlington LG.. The kynurenine pathway as a therapeutic target in cognitive and neurodegenerative disorders. Br J Pharmacol. 2013;169:1211–1227. https://doi.org/ 10.1111/bph.12230 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Savitz J. The kynurenine pathway: a finger in every pie. Mol Psychiatry. 2020;25:131–147. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41380-019-0414-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Gheorghe CE, Martin JA, Manriquez FV, et al. Focus on the essentials: tryptophan metabolism and the microbiome-gut-brain axis. Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2019;48:137–145. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.coph.2019.08.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Wang Z, Yuan X, Zhu Z, et al. Multiomics analyses reveal microbiome-gut-brain crosstalk centered on aberrant gamma-aminobutyric acid and tryptophan metabolism in drug-naïve patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Schizophr Bull. 2024;50:187–198. https://doi.org/ 10.1093/schbul/sbad026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Madan A, Thompson D, Fowler JC, et al. The gut microbiota is associated with psychiatric symptom severity and treatment outcome among individuals with serious mental illness. J Affect Disord. 2020;264:98–106. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jad.2019.12.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Thompson DS, Fu C, Gandhi T, et al. Differential co-expression networks of the gut microbiota are associated with depression and anxiety treatment resistance among psychiatric inpatients. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry. 2023;120:110638. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.pnpbp.2022.110638 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Takahashi JS, Hong HK, Ko CH, McDearmon EL.. The genetics of mammalian circadian order and disorder: implications for physiology and disease. Nat Rev Genet. 2008;9:764–775. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/nrg2430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. McClung CA. How might circadian rhythms control mood? Let me count the ways. Biol Psychiatry. 2013;74:242–249. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.02.019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Patke A, Young MW, Axelrod S.. Molecular mechanisms and physiological importance of circadian rhythms. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2020;21:67–84. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41580-019-0179-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Walker WH 2nd, Walton JC, DeVries AC, Nelson RJ.. Circadian rhythm disruption and mental health. Transl Psychiatry. 2020;10:28. https://doi.org/ 10.1038/s41398-020-0694-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Jones SG, Benca RM.. Circadian disruption in psychiatric disorders. Sleep Med Clin. 2015;10:481–493. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.jsmc.2015.07.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Baglioni C, Nanovska S, Regen W, et al. Sleep and mental disorders: a meta-analysis of polysomnographic research. Psychol Bull. 2016;142:969–990. https://doi.org/ 10.1037/bul0000053 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Scott J, Etain B, Miklowitz D, et al. A systematic review and meta-analysis of sleep and circadian rhythms disturbances in individuals at high-risk of developing or with early onset of bipolar disorders. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2022;135:104585. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2022.104585 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Hickie IB, Crouse JJ.. Sleep and circadian rhythm disturbances: plausible pathways to major mental disorders? World Psychiatry. 2024;23:150–151. https://doi.org/ 10.1002/wps.21154 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Hertenstein E, Feige B, Gmeiner T, et al. Insomnia as a predictor of mental disorders: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Sleep Med Rev. 2019;43:96–105. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.smrv.2018.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Zou H, Zhou H, Yan R, Yao Z, Lu Q.. Chronotype, circadian rhythm, and psychiatric disorders: recent evidence and potential mechanisms. Front Neurosci. 2022;16:811771. https://doi.org/ 10.3389/fnins.2022.811771 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Iorfino F, Scott EM, Carpenter JS, et al. Clinical stage transitions in persons aged 12 to 25 years presenting to early intervention mental health services with anxiety, mood, and psychotic disorders. JAMA Psychiatry. 2019;76:1167–1175. https://doi.org/ 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2019.2360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Melo MCA, Abreu RLC, Linhares Neto VB, de Bruin PFC, de Bruin VMS.. Chronotype and circadian rhythm in bipolar disorder: a systematic review. Sleep Med Rev. 2017;34:46–58. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.smrv.2016.06.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Takaesu Y, Inoue Y, Ono K, et al. Circadian rhythm sleep-wake disorders predict shorter time to relapse of mood episodes in euthymic patients with bipolar disorder: a prospective 48-week study. J Clin Psychiatry. 2018;79:17m11565. https://doi.org/ 10.4088/JCP.17m11565 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Emens J, Lewy A, Kinzie JM, Arntz D, Rough J.. Circadian misalignment in major depressive disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2009;168:259–261. https://doi.org/ 10.1016/j.psychres.2009.04.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]