Abstract

Introduction

Cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic diseases, collectively known as cardio-renal-metabolic (CRM) disease, interact and exacerbate each other, creating serious clinical and economic burdens. Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) are important therapeutic agents in managing CRM disease. Despite proven clinical benefits, the economic benefits of SGLT2i in the management of CRM diseases remain unclear.

Methods

We developed Markov models representing the natural progression of disease for two populations: a type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) population and non-diabetic chronic kidney disease (non-DM CKD) population. These models incorporated key complications, including heart failure, myocardial infarction, stroke, CKD (for the T2DM population), and end-stage renal disease. A systematic literature search was conducted to determine input parameters. For each model, we estimated the 10-year medical costs, quality-adjusted life years (QALY), and incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) for SGLT2i treatment compared with conventional treatment. A probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) and scenario analyses with conservative assumptions were performed.

Results

In the base-case analysis, SGLT2i treatment was estimated to increase QALY by 0.177 (7.090 vs 6.913 QALY; T2DM population) and 0.457 (6.980 vs 6.523 QALY; non-DM CKD population), and increase total medical costs by Japanese yen (JPY) 99,060 (JPY 762,524 vs 663,463; T2DM population) and JPY 229,810 (JPY 3,378,873 vs 3,149,063; non-DM CKD population), compared with conventional treatment. The ICER was JPY 559,175/QALY in the T2DM population and JPY 503,123/QALY in the non-DM CKD population. The PSA revealed that the probability of ICER being below the threshold value of JPY 5,000,000/QALY was 100% in the T2DM population and 98.7% in the non-DM CKD population, and the ICERs were below this threshold in all scenario analyses.

Conclusion

SGLT2i treatment was demonstrated to be cost-effective in both the T2DM population and the non-DM CKD population, suggesting the potential of SGLT2i to offer significant clinical and economic benefits in the comprehensive management of CRM diseases.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-025-03157-z.

Keywords: Cardio-renal-metabolic (CRM) diseases, Cardiovascular disease, Chronic kidney disease, Cost-effectiveness, Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors, Type 2 diabetes mellitus

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? | |

| The clinical and economic burdens of cardio-renal-metabolic (CRM) diseases have become significant and are likely to increase in aging societies. | |

| Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i) are an important treatment option for CRM diseases, with proven efficacy for diabetes mellitus (DM), heart failure, and chronic kidney disease (CKD). | |

| The objective of this study was to assess the cost-effectiveness of SGLT2i for the treatment of CRM diseases using a health economic model, including pathological interactions in CRM diseases. | |

| What was learned from the study? | |

| SGLT2i treatment was estimated to increase quality-adjusted life years (QALY) while increasing total medical costs, resulting in incremental cost-effectiveness ratios of Japanese yen (JPY) 559,175/QALY in the type 2 DM population and JPY 503,123/QALY in the non-DM CKD population, both of which were lower than the threshold of JPY 5,000,000/QALY. | |

| These findings provide novel evidence that SGLT2i are an important treatment option with both clinical and economic benefits in CRM diseases. |

Introduction

Cardiovascular, renal, and metabolic diseases, collectively referred to as cardio-renal-metabolic (CRM) disease [1], are a growing global health concern because of their high morbidity and mortality. Moreover, the pathological interactions and mutual exacerbations among CRM diseases are accelerating the overall disease burden. Type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM) is a strong risk factor for chronic kidney disease (CKD) and cardiovascular disease (CVD) [2, 3]. The pathological interaction between CKD and CVD is recognized as cardiorenal (CR) syndrome [4], and the presence of CKD independently increases the risk of CVD, including heart failure (HF), regardless of diabetes status [5, 6]. In addition to the poor prognosis associated with these conditions, patients with advanced-stage CKD or HF experience severe symptoms that can impair daily activities and reduce their quality of life [7, 8], further compounding the burden.

Besides their clinical burden, the high prevalence of CRM diseases also imposes a substantial societal economic burden. For example, dialysis accounts for 5% of the total medical costs in Japan [9], and USD 1187 million is spent annually on people with HF [10]. These costs are anticipated to increase as the number of affected patients increases in aging societies. Therefore, there is an urgent economic need for cost-effective treatments for CRM diseases.

Sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors (SGLT2i), originally developed for the treatment of diabetes, reduce the incidence of cardiovascular and renal events in people with T2DM [11]. Randomized controlled trials have demonstrated the efficacy of SGLT2i for the prevention of cardiovascular and renal outcomes in people with HF as well as those with CKD, with or without diabetes [12, 13]. SGLT2i are approved for the treatment of HF and/or CKD in many regions and are recognized as a standard therapeutic option to improve the prognosis of CRM diseases [14]. Furthermore, SGLT2i treatment has been shown to be cost-effective in Japan for the management of T2DM, CKD, and HF individually [15–19]. However, these previous models have not comprehensively targeted CRM diseases as a whole or accounted for their pathological interactions, limiting our understanding of the cost-effectiveness of SGLT2i in the Japanese population. In addition, precise estimates are required to support widespread implementation, particularly in aging societies such as Japan where healthcare expenditure is rising rapidly.

In the present study, we constructed a health economic model that incorporated the disease transition between CRM diseases as well as the increased risk of CVD in patients with CKD. With this model, we estimated the cost-effectiveness of SGLT2i for the treatment of CRM diseases in the Japanese T2DM population and non-diabetes mellitus (DM) CKD population. The aim of this study was to investigate whether SGLT2i treatment would be cost-effective for the management of CRM diseases in Japan.

Methods

Model Description

This study separately modeled a T2DM population and a non-DM population. The distribution of age and sex in the T2DM population was based on the published literature of the Shizuoka Kokuho database using data from April 2012 to September 2018 [20]. The Shizuoka Kokuho database is an administrative claims database of residents in Shizuoka Prefecture, Japan, and includes health insurance claim data. The database contains data on Shizuoka residents covered under municipal government health insurance programs, namely National Health Insurance (covering 22.3% of residents aged < 75 years) and the Late-Stage Medical Care System for the Elderly (covering all residents aged ≥ 75 years). For the non-DM population, we focused on the population with CKD, for which SGLT2i treatment is indicated. The distribution of age and sex in the non-DM CKD population was based on Japanese patients in the EMPA-KIDNEY trial, a randomized controlled trial that assessed the efficacy and safety of SGLT2i [21].

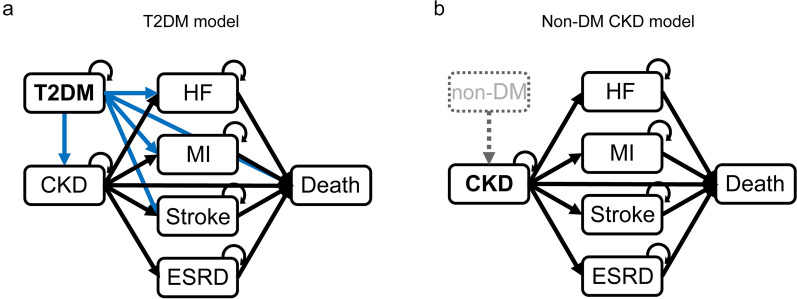

A population-based Monte Carlo simulation was conducted to incorporate different demographic patterns. Two models, for T2DM (Fig. 1a) and non-DM CKD (Fig. 1b) populations, were constructed. Each model comprised the following three states: stable (without complications), post-complication (after developing a complication), and death. CKD (for the T2DM model only), end-stage renal disease (ESRD), HF, myocardial infarction (MI), and stroke were considered complications. All diseases except for CKD were considered independent; i.e., a patient who developed one disease did not manifest with another disease. The cycle length was 1 month, and the time horizon in the base-case analysis was 10 years. The state transition model was constructed using TreeAge Pro 2022 (TreeAge Software, Inc.), which predicts costs and outcomes.

Fig. 1.

Model structure. The T2DM (a) and non-DM CKD (b) models were constructed. All complications except for CKD were considered independent (i.e., a patient who developed one disease did not manifest another disease). CKD chronic kidney disease, ESRD end-stage renal disease, HF heart failure, MI myocardial infarction, non-DM non-diabetes mellitus, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus

Incidence and mortality rates (Table 1), intervention effects of SGLT2i (Table 2), and utilities/disutilities (Table 3) were extracted through a systematic literature review (SLR).

Table 1.

Incidence and mortality rates

| Disease | Incidence rate {95% CI}, per 100 p-y | CKD-dependent increase, HR {95% CI}s | Mortality rate, per 100 p-y | Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2DM population | ||||

| T2DM | – | – | 1.57 | [3] |

| CKD | 1.58 {1.56–1.61} | – | 2.40 | [3] |

| ESRD | 1.33 {1.30–1.36} | – | 4.98 | [22, 23] |

| MI | 0.21 {0.20–0.22} | 1.72 {1.42–2.08} | 1.92 | [2, 3] |

| Stroke | 1.11 {1.09–1.13} | 1.54 {1.41–1.68} | 1.92 | [2, 3] |

| HF | 2.07 {2.04–2.10} | 2.23 {2.11–2.36} | 3.26 | [2, 3] |

| Non-DM CKD population | ||||

| CKD | – | – | 2.79 | [3] |

| ESRD | 1.22 {1.20–1.24} | – | 2.79 | [3, 22] |

| MI | 0.11 {0.10–0.11} | 1.86 {1.01–3.44} | 1.79 | [3, 24] |

| Stroke | 0.86 {0.85–0.88} | 1.13 {0.86–1.48} | 1.57 | [3, 24] |

| HF | 1.32 {1.30–1.33} | 1.94 {1.49–2.53} | 3.32 | [3, 25] |

CI confidence interval, CKD chronic kidney disease, ESRD end-stage renal disease, HF heart failure, HR hazard ratio, MI myocardial infarction, non-DM non-diabetes mellitus, p-y person-years, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus

Table 2.

SGLT2i effects on clinical events

| T2DM population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| State | T2DM | With CKD | With HF | Source |

| SGLT2i effect, HR {95% CI} | SGLT2i effect, HR {95% CI} | SGLT2i effect, HR {95% CI} | ||

| Clinical event | ||||

| CKD | 0.81 {0.75–0.88} | – | – | [26]a |

| ESRD | – | 0.69 {0.51–0.95} | – | [27] |

| MI | 0.84 {0.62–1.14} | 0.58 {0.31–1.07} | – | [26]a, [27] |

| Stroke | 0.59 {0.51–0.69} | 0.54 {0.28–1.03} | – | [26]a, [27] |

| HF | 0.84 {0.75–0.93} | 0.61 {0.39–0.96} | – | [26]a, [27] |

| Death | 0.69 {0.61–0.79} | 0.89 {0.63–1.26} | 0.78 {0.63–0.97} | [26]a, [27, 28] |

| Non-DM CKD population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | CKD | With HF | Source |

| SGLT2i effect, HR {95% CI} | SGLT2i effect, HR {95% CI} | ||

| Clinical event | |||

| ESRD | 0.56 {0.36–0.87} | [29] | |

| MI | 0.83 {0.55–1.25} | [30] | |

| Stroke | 1 | Assumption | |

| HF | 0.31 {0.10–0.94} | [30] | |

| Death | 0.52 {0.29–0.93} | 0.88 {0.70–1.12} | [28, 29] |

CI confidence interval, CKD chronic kidney disease, ESRD end-stage renal disease, HF heart failure, HR hazard ratio, MI myocardial infarction, non-DM non-diabetes mellitus, SGLT2i sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus

aData were obtained by ad hoc analysis. Details of the method are provided in the Supplementary Materials

Table 3.

Utility and disutility

| Disease | T2DM population | Non-DM CKD population | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Utility or disutilitya, (SD) [SE] | Source | Utility, (SD) {95% CI} | Source | |

| T2DM | 0.95 (0.09) | [31] | – | – |

| CKD | 0.90 (0.13) | [31] | 0.901 {0.873–0.929} | [33] |

| ESRD | 0.78 (0.18) | [31] | 0.836 {0.779–0.893} | [33] |

| MI | 0.055 [0.006] | [32] | 0.79 {0.73–0.86} | [34] |

| Stroke | 0.164 [0.030] | [32] | 0.66 (0.21) | [35] |

| HF | 0.101 [0.031] | [32] | 0.8 (0.2) | [36] |

CI confidence interval, CKD chronic kidney disease, ESRD end-stage renal disease, HF heart failure, MI myocardial infarction, non-DM non-diabetes mellitus, SD standard deviation, SE standard error, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus

aDisutility values in the table are shown in italic text

This study is based on previously conducted studies and published literature and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals. Therefore, no ethical approval was required.

Intervention Strategies

Treatment with SGLT2i was compared with conventional treatment for the management of CRM or CR disease. For the T2DM population, patients initiated antidiabetic medication with either SGLT2i treatment (assuming an equal probability of the six SGLT2i) or conventional treatment (where other glucose-lowering drugs were used at the rate reflecting the Japanese clinical settings having a variety of the first-line drug: dipeptidyl peptidase 4 inhibitors in 63.5% of patients, biguanides in 9.3%, α-glucosidase inhibitors in 5.1%, sulfonylureas in 4.9%, SGLT2i in 2.6%, and thiazolidinediones in 1.8%) [20]. Once an SGLT2i-treated patient developed CKD, the SGLT2i was switched to one with an indication for CKD or CKD with T2DM (assuming an equal probability between dapagliflozin 10 mg and canagliflozin 100 mg). Patients who developed HF with SGLT2i treatment were switched to an SGLT2i with an indication for HF (assuming an equal probability of dapagliflozin 10 mg and empagliflozin 10 mg). For the non-DM CKD population, SGLT2i-treated patients initiated dapagliflozin 10 mg, and when the patient developed HF, the medication was switched to an SGLT2i with an indication for HF in the same manner as for the T2DM population. SGLT2i were assumed to be prescribed in addition to conventional medications for CKD or HF. Each treatment strategy was maintained until ESRD or death.

Model Input Data

Relevant evidence on the Japanese population from 2012 to 2022 in the PubMed, EMBASE, and ICHUSHI databases was searched, and the details of the SLR are described in the Supplementary Materials (PRISMA flowchart in Fig. S1, and eligibility criteria in Tables S1, S2, and S3). Model input data were obtained from the SLR unless described otherwise. Because no studies that reported CKD-dependent increases in the risk of CVD in a Japanese non-DM population were found, these parameters were obtained from articles that included patients with DM or non-Japanese patients [24, 25]. When multiple relevant articles were obtained, the one with a closer match to the target population/states and sufficient sample size was preferentially selected. In addition, we selected the literature that could provide more input parameters, considering consistency of data.

Although several studies reporting the effects of SGLT2i in Japanese patients with T2DM were found, off-label use of SGLT2i and other glucose-lowering drugs cannot be ruled out in these studies. Thus, to exclude potential off-label use, we conducted an ad hoc analysis of the largest database research found through the SLR (described in the Supplementary Materials, with patient disposition shown in Fig. S2, and patient characteristics shown in Table S4) [26].

The effect size of SGLT2i on clinical events in patients with CKD or HF, respectively, was obtained from CREDENCE [27] and DAPA-CKD [29, 30] or from DAPA-HF [28]. On the basis of previous reports, we assumed that SGLT2i did not affect the risk of stroke in patients without DM with CKD [37, 38].

The utility values for the Japanese non-DM population were not found through the SLR and were thus obtained from the CHEQOL Quality of Life (QOL) database (http://cheqol.com/database/index.php) [33, 35, 36] or studies including non-Japanese individuals [34]. Age- or sex-dependent increases in the risks of developing complications were also incorporated into the Monte Carlo simulation (Table S5).

Treatment costs other than for ESRD were obtained by analyzing Japanese real-world data [3]. Total treatment costs for the initial phase (first year after the first diagnosis) and maintenance phase (subsequent 2 years) were summarized for each disease. Further details of the analysis are provided in the Supplementary Materials (patient disposition shown in Fig. S3). The treatment cost for ESRD was set at Japanese yen (JPY) 350,000 per month based on previous literature [9, 39].

Treatment costs were incorporated into the model as an annual cost (Table 4). For antidiabetic medication in the SGLT2i treatment, the average daily cost of SGLT2i available for T2DM in Japan was used (Table 5). For antidiabetic medication in the conventional treatment, the daily cost was calculated on the basis of the reported usage rate of oral glucose-lowering drugs in Japan [20]. For HF, CKD with T2DM, or CKD without T2DM in the SGLT2i treatment, the average daily cost of SGLT2i available for each indication in Japan was used (Table 5). Costs of conventional medications were assumed to be included in the treatment cost for each disease.

Table 4.

Treatment cost

| Disease | T2DM population | Non-DM CKD population | Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean [SE], JPY | Mean [SE], JPY | ||

| ESRD (monthly) | 350,000 | 350,000 | |

| [Lower: − 25%, Upper: + 25%] | [Lower: − 25%, Upper: + 25%] | [9, 39] | |

| HF (annual) | |||

| Initial phase | 459,646 | 409,758 | [3]a |

| [19,258] | [17,904] | ||

| Maintenance phase | 197,581 | 136,110 | [3]a |

| [26,771] | [20,361] | ||

| MI (annual) | |||

| Initial phase | 607,862 | 549,080 | [3]a |

| [63,478] | [66,712] | ||

| Maintenance phase | 279,161 | 323,463 | [3]a |

| [65,518] | [219,987] | ||

| Stroke (annual) | |||

| Initial phase | 403,205 | 350,957 | [3]a |

| [16,381] | [14,366] | ||

| Maintenance phase | 207,297 | 125,560 | [3]a |

| [23,896] | [11,806] | ||

| CKD (annual) | |||

| Initial phase | 419,974 | 403,570 | [3]a |

| [18,101] | [21,480] | ||

| Maintenance phase | 200,138 | 190,245 | [3]a |

| [16,120] | [41,514] | ||

CKD chronic kidney disease, ESRD end-stage renal disease, HF heart failure, JPY Japanese yen, MI myocardial infarction, non-DM non-diabetes mellitus, SE standard error, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus

aData were obtained by ad hoc analysis. Details of the method are provided in the Supplementary Materials

Table 5.

Medication cost

| Cost per day, JPY | |

|---|---|

| SGLT2i treatment | |

| T2DM | 174.6 |

| CKD with T2DM | 217.0 |

| CKD without DM | 264.9 |

| HF | 222.9 |

| Conventional treatment | |

| T2DM | 112.5 |

As of November 2022

CKD chronic kidney disease, DM diabetes mellitus, HF heart failure, JPY Japanese yen, SGLT2i sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus

Sensitivity Analyses

A one-way sensitivity analysis was performed to investigate the effect of each parameter in the analysis. The net monetary benefit (NMB) was used to represent the results, in which the number of incremental quality-adjusted life years (QALY) was converted into an incremental monetary benefit using the willingness-to-pay of JPY 5,000,000/QALY gained. A probabilistic sensitivity analysis (PSA) with approximately 1,000,000 iterations was performed to explore the impact of joint uncertainty in all modeled parameters. Appropriate statistical distributions were assigned to each model input. For each input value, the chosen distribution was parameterized on the basis of the available information (including standard deviation and confidence intervals).

Several scenario analyses with conservative approaches were conducted, including (1) no effect of SGLT2i on death, (2) no effect of SGLT2i on HF onset in patients with CKD, (3) no maintenance cost for the treatment of complications other than ESRD, (4) antidiabetic medication cost reduced by half in conventional treatment, (5) time horizon set to 5 years, and (6) time horizon set to 20 years.

In addition, two exploratory analyses were conducted in the T2DM population, assuming (1) all individuals concomitantly had CKD, and (2) two-fold and five-fold higher incidence rates for CKD.

Results

Base-Case Results

We estimated the cost-effectiveness of SGLT2i vs conventional treatment over a 10-year time horizon, using the two Markov models for simulating the T2DM or non-DM CKD population considering the development of complications (Fig. 1). In the T2DM population, the costs of SGLT2i treatment and conventional treatment were JPY 762,524 and JPY 663,463, respectively. SGLT2i treatment improved QALY by 0.177 and life years (LY) by 0.162, compared with conventional treatment (7.090 vs 6.913 QALY, and 7.546 vs 7.383 LY). The incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER) of SGLT2i treatment was JPY 559,175/QALY (Table 6). In the non-DM CKD population, the costs of SGLT2i treatment and conventional treatment were JPY 3,378,873 and JPY 3,149,063, respectively. Both QALY and LY were improved with SGLT2i treatment compared with conventional treatment (6.980 vs 6.523 QALY, and 7.893 vs 7.445 LY), resulting in an ICER in the SGLT2i treatment of JPY 503,123/QALY (Table 6).

Table 6.

Base-case results

| T2DM population | Non-DM CKD population | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT2i treatment | Conventional treatment | Difference | SGLT2i treatment | Conventional treatment | Difference | |

| Discounted (2%) | ||||||

| Cost, JPY | 762,524 | 663,463 | 99,060 | 3,378,873 | 3,149,063 | 229,810 |

| QALY | 7.090 | 6.913 | 0.177 | 6.980 | 6.523 | 0.457 |

| LY | 7.546 | 7.383 | 0.162 | 7.893 | 7.445 | 0.448 |

| ICER | 559,175 | 503,123 | ||||

| Undiscounted | ||||||

| Cost, JPY | 843,172 | 737,232 | 105,939 | 3,716,540 | 3,481,734 | 234,806 |

| QALY | 7.750 | 7.549 | 0.201 | 7.642 | 7.124 | 0.518 |

| LY | 8.250 | 8.066 | 0.184 | 8.647 | 8.139 | 0.508 |

| ICER | 527,527 | 453,488 | ||||

Difference is SGLT2i treatment − Conventional treatment

ICER incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, JPY Japanese yen, LY life years, non-DM non-diabetes mellitus, QALY quality-adjusted life years, SGLT2i sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus

In the cost analysis, although SGLT2i treatment incurred higher total costs, it had reduced treatment costs for all complications in the T2DM population compared with conventional treatment (Fig. 2a). In the non-DM CKD population, SGLT2i treatment increased CKD and stroke treatment costs as well as SGLT2i medication costs, but decreased treatment costs for ESRD, HF, and MI (Fig. 2b).

Fig. 2.

Breakdown of costs. The breakdown of costs in the base-case analysis in the T2DM (a) and non-DM CKD (b) models. CKD chronic kidney disease, ESRD end-stage renal disease, HF heart failure, JPY Japanese yen, MI myocardial infarction, non-DM non-diabetes mellitus, SGLT2i sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus

Compared with conventional treatment, with SGLT2i treatment, there were 379 and 972 fewer deaths per 10,000 persons in the T2DM population and the non-DM CKD population, respectively (Table 7). In the T2DM population, SGLT2i also reduced the development of all complications compared with the conventional treatment. In the non-DM CKD population, SGLT2i reduced the incidence of all complications except for stroke.

Table 7.

Incidence of events in the base-case analysis

| Clinical event | T2DM population | Non-DM CKD population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT2i treatment | Conventional treatment | Difference | SGLT2i treatment | Conventional treatment | Difference | |

| All-cause death | 1009 | 1388 | − 379 | 1308 | 2281 | − 972 |

| CKD | 1148 | 1331 | − 183 | – | – | – |

| HF | 867 | 1018 | − 151 | 328 | 896 | − 569 |

| MI | 81 | 95 | − 14 | 130 | 140 | − 10 |

| Stroke | 320 | 519 | − 198 | 554 | 481 | 73 |

| ESRD | 41 | 65 | − 24 | 538 | 857 | − 319 |

Incidence of events per 10,000 persons over the 10-year horizon in the base-case analysis is shown. Difference is SGLT2i treatment − Conventional treatment

CKD chronic kidney disease, ESRD end-stage renal disease, HF heart failure, MI myocardial infarction, non-DM non-diabetes mellitus, SGLT2i sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus

Sensitivity Analyses

Figure 3 shows the tornado diagram of the top 16 variables in the one-way sensitivity analysis. The incremental NMB values were positive in all the analyses. The effects of SGLT2i on death or ESRD, and the utility scores for diseases, had a strong influence on the incremental NMB in both the T2DM population (Fig. 3a) and the non-DM CKD population (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Tornado diagram from one-way sensitivity analyses. The tornado plot shows the uncertainty in ICER for each input variable in the T2DM (a) and non-DM CKD (b) models. The maximum and minimum ICERs for each variable are shown as incremental NMB at the end of each bar. The results for variables with higher impact (top 16) on the ICER are shown. CKD chronic kidney disease, ESRD end-stage renal disease, EV equivalent variation, HF heart failure, ICER incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, MI myocardial infarction, NMB net monetary benefit, non-DM non-diabetes mellitus, QOL quality of life, SGLT2i sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus

The ICER scatter plot in the T2DM population shows that, in 24.4% of iterations, SGLT2i treatment was dominant (i.e., less costly and more effective regarding QALY increases), and SGLT2i was cost-effective (i.e., more costly and more effective regarding QALY increases) in 75.6% of the iterations (Fig. 4a). In the non-DM CKD population, 98.7% of iterations were dominant (21.5%) or cost-effective (77.2%) for SGLT2i treatment (Fig. 4b). The cost-effectiveness acceptability curve also indicated that the SGLT2i treatment is cost-effective at the threshold of JPY 5,000,000/QALY in both populations (Fig. S4).

Fig. 4.

ICER scatter plot from probabilistic sensitivity analysis. The scatterplot shows the incremental costs and QALY of the SGLT2i treatment compared with the conventional treatment in the Monte Carlo simulations in the T2DM (a) and non-DM CKD (b) models. The dotted line represents the WTP threshold of JPY 5,000,000/QALY. Green dots represent iterations with ICER values below the threshold, while red dots represent iterations with ICER values above the threshold. CKD chronic kidney disease, ICER incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, JPY Japanese yen, non-DM non-diabetes mellitus, QALY quality-adjusted life years, SGLT2i sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus, WTP willingness-to-pay

In the scenario where SGLT2i has no effect on death or on HF onset in patients with CKD, the ICER values were higher than the base-case results in both populations (Table 8). When no maintenance costs other than ESRD were assumed, the ICER value increased in the T2DM population (JPY 683,938/QALY) but decreased in the non-DM CKD population (JPY 246,045/QALY). When the cost of antidiabetic medication was halved, the ICER value increased to JPY 1,374,493/QALY in the T2DM population. The ICER values in analyses with 5-year and 20-year time horizons were JPY 1,347,017/QALY and JPY 194,268/QALY, respectively, in the T2DM population, and JPY 1,758,533/QALY and JPY 67,620/QALY, respectively, in the non-DM CKD population. In all six scenarios, the ICER values were well below the threshold of JPY 5,000,000/QALY.

Table 8.

Scenario analysis

| Scenario | T2DM population | Non-DM CKD population | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SGLT2i treatment | Conventional treatment | Difference | SGLT2i treatment | Conventional treatment | Difference | |

| Scenario 1: No effect of SGLT2i on death | ||||||

| Cost, JPY | 746,957 | 664,950 | 82,007 | 3,210,561 | 3,143,153 | 67,407 |

| QALY | 6.958 | 6.916 | 0.042 | 6.591 | 6.523 | 0.068 |

| ICER | 1,938,923 | 998,090 | ||||

| Scenario 2: No effect of SGLT2i on HF onset in patients with CKD | ||||||

| Cost, JPY | 773,034 | 664,950 | 108,084 | 3,355,834 | 3,143,153 | 212,681 |

| QALY | 7.085 | 6.916 | 0.170 | 6.932 | 6.523 | 0.409 |

| ICER | 636,889 | 519,572 | ||||

| Scenario 3: No maintenance treatment cost for diseases other than ESRD | ||||||

| Cost, JPY | 615,550 | 492,401 | 123,150 | 2,144,877 | 2,029,069 | 115,807 |

| QALY | 7.096 | 6.916 | 0.180 | 6.989 | 6.519 | 0.471 |

| ICER | 683,938 | 246,045 | ||||

| Scenario 4: Antidiabetic medication cost reduced by half in conventional treatment | ||||||

| Cost, JPY | 760,793 | 513,137 | 247,656 | – | – | |

| QALY | 7.096 | 6.916 | 0.180 | |||

| ICER | 1,374,493 | |||||

| Scenario 5: Time horizon set to 5 years | ||||||

| Cost, JPY | 377,622 | 304,824 | 72,798 | 1,772,662 | 1,525,925 | 246,737 |

| QALY | 4.131 | 4.077 | 0.054 | 3.978 | 3.837 | 0.140 |

| ICER | 1,347,017 | 1,758,533 | ||||

| Scenario 6: Time horizon set to 20 years | ||||||

| Cost, JPY | 1,347,777 | 1,261,663 | 86,114 | 6,009,362 | 5,929,450 | 79,912 |

| QALY | 10.324 | 9.881 | 0.443 | 10.745 | 9.563 | 1.182 |

| ICER | 194,268 | 67,620 | ||||

Difference is SGLT2i treatment − Conventional treatment

CKD chronic kidney disease, ESRD end-stage renal disease, HF heart failure, ICER incremental cost-effectiveness ratio, JPY Japanese yen, non-DM non-diabetes mellitus, QALY quality-adjusted life years, SGLT2i sodium–glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor, T2DM type 2 diabetes mellitus

Exploratory Analyses in the T2DM Population

In the T2DM with CKD population, SGLT2i was dominant, with higher increases in QALY compared with conventional treatment (6.388 vs 6.248) and reduced total costs (JPY 3,109,838 vs JPY 3,286,059) (Table S6).

In an exploratory analysis that assumed a two-fold higher CKD incidence rate, SGLT2i treatment resulted in similar costs (JPY 899,903 vs JPY 849,268) and increased QALY (7.055 vs 6.878) compared with conventional treatment, with an ICER of JPY 285,725/QALY (Table S7). When assuming a five-fold higher incidence rate, the SGLT2i treatment was also dominant (Table S7).

Discussion

Rigorous cost-effectiveness assessments are needed to overcome cost barriers for new medications with proven clinical benefits. In this study, we performed a clinically relevant analysis by integrating CRM interactions into the model and conducting SLR for our input parameters. We demonstrated that treatment with SGLT2i is highly cost-effective for patients with CRM diseases, with favorable ICER values of JPY 559,175/QALY in the T2DM population and JPY 503,123/QALY in the non-DM CKD population. In both populations, SGLT2i treatment incurred higher total costs but had a greater gain in QALY, which was attributed to a reduction in complications as well as mortality. In the non-DM CKD population, the increased incidence of stroke with SGLT2i treatment may be explained by our model settings, which assumed that SGLT2i had no effect on stroke while preventing the other complications. The PSA indicated that all or most cases were dominant or below the threshold of JPY 5,000,000/QALY for SGLT2i treatment, showing the robustness of the base-case analysis. Overall, our results suggest that SGLT2i, having cardiorenal and mortality benefits, could be an excellent therapeutic option for the treatment of CRM diseases.

In all scenarios tested in our analyses, ICER values were well below the threshold of JPY 5,000,000/QALY, suggesting that our findings may be applicable in a wide range of situations. These analyses provide additional insights into the cost-effectiveness of SGLT2i in different clinical circumstances and with different prescribing options. When assuming that SGLT2i treatment had no effect on death, the ICER values were worse than those of the base-case results in both the T2DM and the non-DM CKD populations, demonstrating the positive economic effects of improved mortality with SGLT2i treatment, which have been proven in clinical trials such as the DAPA-CKD and DAPA-HF trials [12, 13]. This finding was also supported by our one-way sensitivity analysis, which revealed that mortality benefits were ranked as the third or fourth most influential variables in the T2DM population and the most influential variable in the non-DM CKD population. As ICER values improved over a longer analytic time horizon, SGLT2i may have a greater economic impact with longer-term prescription, which is consistent with a recent study [18].

Despite the apparent benefit of early diagnosis and treatment to improve clinical outcomes, people with CKD, especially in the early stages, are often undiagnosed [40, 41]. For the incidence rate of CKD in the T2DM population, we could not find literatures in which CKD was precisely defined using laboratory values, and used the literature in which CKD was defined on the basis of the International Classification of Diseases 10th Revision codes [3]. Thus, the incidence is likely an underestimate in the present study. When the diagnosis rate increased by two-fold and five-fold, ICER values were improved over the base case, including a lower treatment cost with SGLT2i treatment vs conventional treatment. This suggests that the appropriate early diagnosis and management of CKD can further increase the value of SGLT2i, where they can help to prevent ESRD as well as CKD-triggered CVD.

Several SGLT2i cost-effectiveness studies have been conducted in various geographical regions and disease areas, and consistently report an acceptable ICER value [42–44]. In Japan, the cost-effectiveness analysis of SGLT2i has been conducted individually for specific CRM diseases (T2DM, HF, and CKD). The ICER value of empagliflozin was reported to be JPY 415,849/QALY in patients with T2DM [15] and USD 24,046/QALY in patients with HF with reduced ejection fraction [16]. For dapagliflozin, the ICER value was USD 13,723/QALY in patients with CKD [18]. Furthermore, we previously found that initiating antidiabetic therapy with SGLT2i reduced the incidence of cardiovascular and renal complications and reduced total clinical costs compared with conventional therapy in patients with T2DM [32]. Thus, previous studies have consistently shown a health economic benefit of SGLT2i in the Japanese population. However, no study has included a comprehensive assessment that incorporates the interaction between CRM diseases, which is an important consideration for the clinical care of these patients. The clinical benefits of SGLT2i have been demonstrated for patients with T2DM, HF, and CKD [11–13], and guidelines now recommend SGLT2i treatment as the standard medication for these diseases to manage each disease as well as the interaction between CRM diseases [45, 46]. For example, the Japan Diabetes Society’s proposed algorithm for pharmacotherapy in T2DM states that the cardiovascular and renal benefits of SGLT2i should be considered when selecting antidiabetic medications [47]. These updates in clinical practice have led to a growing need for evaluating the cost-effectiveness of SGLT2i as a medication to totally manage CRM diseases. In our analysis, we have demonstrated the cost-effectiveness of SGLT2i for the comprehensive management of these diseases, which may further facilitate the implementation of SGLT2i in clinical practice.

The model in our present study accounted for interactions between CRM diseases. Nonetheless, there are a few pathologically important factors that remain to be considered. Incidence of CVD is a risk factor for the onset and progression of CKD [48, 49]. While our model incorporated the disease transition from T2DM or CKD to CVD, we did not consider the transition from CVD to CKD. In addition, CKD stages and proteinuria should also be considered because the progression through CKD stages substantially increases the risks for CVD as well as ESRD and mortality [50, 51]. The efficacy of SGLT2i has been demonstrated in patients with HF irrespective of DM or CKD status [12]; however, our analysis did not evaluate the non-DM HF population without CKD. Further improvements will be made to our model to allow for additional clinically relevant assessments.

This study has several limitations. First, the data on the treatment cost were obtained from a relatively small dataset. Second, the direct non-healthcare costs and productivity costs for people with CVD and ESRD were not included. Third, the CKD diagnosis rate was low in clinical settings, raising the possibility that the present study might not have fully evaluated the cost-effectiveness of SGLT2i. Although we included analyses with different CKD diagnosis rates, further investigations are needed using data where patients with CKD are appropriately diagnosed. Fourth, while the comprehensive and systematic selection of input data through SLR is a strength in our study, some data on the incidence rate and the SGLT2i effects include the non-Japanese population because of a lack of available articles and may not fully reflect the parameters in the Japanese population. Fifth, the database we used for the age and sex distribution of the T2DM population in our model does not adequately cover residents under 75 years of age. However, the distribution values used in this study are similar to those in another large database study [52], suggesting a minimal impact on the generalizability of our results.

Conclusion

Our simulation model that incorporated interactions of CRM diseases demonstrated that SGLT2i treatment was cost-effective compared with conventional treatment in both the T2DM and the non-DM CKD populations. Our findings suggest the substantial clinical and economic benefits of SGLT2i treatment for CRM diseases in the Japanese healthcare system.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Medical Writing, Editorial, and Other Assistance

The authors wish to thank Hannah Read, PhD, of Edanz, Japan, for providing editorial support, which was funded by AstraZeneca K.K., Japan, through EMC K.K., Japan, in accordance with Good Publication Practice guidelines (http://www.ismpp.org/gpp-2022). The authors thank Shinichiro Kato and Asuka Ozaki from AstraZeneca K.K. for supporting the data interpretation and manuscript development.

Author Contributions

Ataru Igarashi, Hisateru Tachimori, Keiko Maruyama-Sakurai, Yasumasa Segawa, Hiroyuki Takagi, Hiroki Akiyama, Naohiko Imai, Shun Kohsaka, and Hiroaki Miyata contributed to the conception and design of the study. Ataru Igarashi developed the simulation model and analyzed the data. All authors contributed to the interpretation of the data. Hiroyuki Takagi drafted the manuscript. All authors critically revised the manuscript for important intellectual content and gave final approval of the version to be published.

Funding

Open Access funding provided by The University of Tokyo. This work, including the rapid service fee and the open access fee, was supported by the Japan Science and Technology Agency Program on Open Innovation Platform with Enterprises, Research Institute and Academia (JST-OPERA) (grant number JPMJOP1842) and by AstraZeneca K.K., Osaka, Japan.

Data Availability

All data used in the present study are available in this article or in the cited articles.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Ataru Igarashi has received lecture fees from Astellas Pharma Inc., Bayer Yakuhin, Ltd., Eli Lilly Japan K.K., Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation, MSD Co., Ltd., Novartis Pharma K.K., and Ono Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd.; and belongs to the endowed department sponsored by Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Hisateru Tachimori belongs to the endowed department sponsored by Takeda Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. Hiroyuki Takagi and Hiroki Akiyama are full-time employees of AstraZeneca K.K. Shun Kohsaka has received research funding from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science and Pfizer, and has received consulting fees from Novartis and Bristol Myers Squibb, outside of the submitted work. Hiroaki Miyata has received research funding from AstraZeneca K.K. and Mitsubishi Tanabe Pharma Corporation. Keiko Maruyama-Sakurai, Yasumasa Segawa, and Naohiko Imai have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Ethical Approval

This study is based on previously conducted studies and published literature and does not contain any new studies with human participants or animals.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation Some of the results from this study were presented at the 60th European Renal Association Congress (June 15–18, 2023, Milan, Italy) and at the 54th Western Regional Meeting of the Japanese Society of Nephrology (October 5–6, 2024, Himeji, Japan).

References

- 1.Kadowaki T, Maegawa H, Watada H, et al. Interconnection between cardiovascular, renal and metabolic disorders: a narrative review with a focus on Japan. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2022;24:2283–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Birkeland KI, Bodegard J, Eriksson JW, et al. Heart failure and chronic kidney disease manifestation and mortality risk associations in type 2 diabetes: a large multinational cohort study. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22:1607–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kadowaki T, Komuro I, Morita N, Akiyama H, Kidani Y, Yajima T. Manifestation of heart failure and chronic kidney disease are associated with increased mortality risk in early stages of type 2 diabetes mellitus: analysis of a Japanese real-world hospital claims database. Diabetes Ther. 2022;13:275–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rangaswami J, Bhalla V, Blair JEA, et al. American Heart Association Council on the Kidney in Cardiovascular Disease and Council on Clinical Cardiology. Cardiorenal syndrome: Classification, pathophysiology, diagnosis, and treatment strategies: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2019;139:e840–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jankowski J, Floege J, Fliser D, Böhm M, Marx N. Cardiovascular disease in chronic kidney disease: pathophysiological insights and therapeutic options. Circulation. 2021;143:1157–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nayor M, Larson MG, Wang N, et al. The association of chronic kidney disease and microalbuminuria with heart failure with preserved vs reduced ejection fraction. Eur J Heart Fail. 2017;19:615–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Di Tanna GL, Urbich M, Wirtz HS, et al. Health state utilities of patients with heart failure: a systematic literature review. Pharmacoeconomics. 2021;39:211–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Noto S, Miyazaki M, Takeuchi H, Saito S. Relationship between hemodialysis and health-related quality of life: a cross-sectional study of diagnosis and duration of hemodialysis. Ren Replace Ther. 2021;7:62. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hanafusa N, Fukagawa M. Global dialysis perspective: Japan. Kidney360. 2020;1:416–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Kanaoka K, Okayama S, Nakai M, et al. Hospitalization costs for patients with acute congestive heart failure in Japan. Circ J. 2019;83:1025–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wiviott SD, Raz I, Bonaca MP, et al. DECLARE–TIMI 58 Investigators. Dapagliflozin and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:347–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McMurray JJV, Solomon SD, Inzucchi SE, et al. DAPA-HF Trial Committees and Investigators. Dapagliflozin in patients with heart failure and reduced ejection fraction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:1995–2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, et al. DAPA-CKD Trial Committees and Investigators. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1436–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Akiyama H, Nishimura A, Morita N, Yajima T. Evolution of sodium-glucose co-transporter 2 inhibitors from a glucose-lowering drug to a pivotal therapeutic agent for cardio-renal-metabolic syndrome. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1111984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kaku K, Haneda M, Sakamaki H, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of empagliflozin in Japan based on results from the Asian subpopulation in the EMPA-REG OUTCOME trial. Clin Ther. 2019;41:2021–40.e11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Liao CT, Yang CT, Kuo FH, et al. Cost-effectiveness evaluation of add-on empagliflozin in patients with heart failure and a reduced ejection fraction from the healthcare system’s perspective in the Asia-Pacific region. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021;8:750381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kodera S, Morita H, Nishi H, Takeda N, Ando J, Komuro I. Cost-effectiveness of dapagliflozin for chronic kidney disease in Japan. Circ J. 2022;86:2021–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McEwan P, Davis JA, Gabb PD, et al. Dapagliflozin in chronic kidney disease: Cost-effectiveness beyond the DAPA-CKD trial. Clin Kidney J. 2024;17:sfae025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Maruyama-Sakurai K, Tachimori H, Saito E, et al. Cost-effectiveness of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in the treatment of diabetic nephropathy in Japan. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2024;26:5546–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kohsaka S, Kumamaru H, Nishimura S, et al. Incidence of adverse cardiovascular events in type 2 diabetes mellitus patients after initiation of glucose-lowering agents: a population-based community study from the Shizuoka Kokuho database. J Diabetes Investig. 2021;12:1452–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.EMPA-KIDNEY Collaborative Group. Design, recruitment, and baseline characteristics of the EMPA-KIDNEY trial. Nephrol Dial Transplant. 2022;37:1317–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fukuma S, Ikenoue T, Shimizu S, et al. and on behalf of BiDANE: Big Data Analysis of Medical Care for the Older in Kyoto. Quality of care in chronic kidney disease and incidence of end-stage renal disease in older patients: A cohort study. Med Care. 2020;58:625–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Iwase M, Ide H, Ohkuma T, et al. Incidence of end-stage renal disease and risk factors for progression of renal dysfunction in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes: the Fukuoka Diabetes Registry. Clin Exp Nephrol. 2022;26:122–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohsawa M, Tanno K, Itai K, et al. Comparison of predictability of future cardiovascular events between chronic kidney disease (CKD) stage based on CKD epidemiology collaboration equation and that based on modification of diet in renal disease equation in the Japanese general population–Iwate KENCO Study. Circ J. 2013;77:1315–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kottgen A, Russell SD, Loehr LR, et al. Reduced kidney function as a risk factor for incident heart failure: the atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) study. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2007;18:1307–15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Komuro I, Kadowaki T, Bodegård J, Thuresson M, Okami S, Yajima T. Lower heart failure and chronic kidney disease risks associated with sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitor use in Japanese type 2 diabetes patients without established cardiovascular and renal diseases. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2021;23(Suppl 2):19–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mahaffey KW, Jardine MJ, Bompoint S, et al. Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes mellitus and chronic kidney disease in primary and secondary cardiovascular prevention groups. Circulation. 2019;140:739–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Petrie MC, Verma S, Docherty KF, et al. Effect of dapagliflozin on worsening heart failure and cardiovascular death in patients with heart failure with and without diabetes. JAMA. 2020;323:1353–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wheeler DC, Stefánsson BV, Jongs N, et al. DAPA-CKD Trial Committees and Investigators. Effects of dapagliflozin on major adverse kidney and cardiovascular events in patients with diabetic and non-diabetic chronic kidney disease: a prespecified analysis from the DAPA-CKD trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021;9:22–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.McMurray JJV, Wheeler DC, Stefánsson BV, et al. DAPA-CKD Trial Committees and Investigators. Effect of dapagliflozin on clinical outcomes in patients with chronic kidney disease, with and without cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2021;143:438–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ishii H, Takamura H, Nishioka Y, et al. Quality of life and utility values for cost-effectiveness modeling in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Ther. 2020;11:2931–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Igarashi A, Maruyama-Sakurai K, Kubota A, et al. Cost-effectiveness analysis of initiating type 2 diabetes therapy with a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor versus conventional therapy in Japan. Diabetes Ther. 2022;13:1367–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tajima R, Kondo M, Kai H, et al. Measurement of health-related quality of life in patients with chronic kidney disease in Japan with EuroQol (EQ-5D). Clin Exp Nephrol. 2010;14:340–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Betts MB, Rane P, Bergrath E, et al. Utility value estimates in cardiovascular disease and the effect of changing elicitation methods: a systematic literature review. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Izumi R, Noto S, Sano T, Suzuki T. Changes in health-related quality of life and concordance of proxy responses in convalescent rehabilitation wards: assessment of stroke patients using the EQ-5D-5L. Nihon Rinsho Sagyo Ryoho Kenkyu [Jpn J Clin Occupat Ther]. 2021;8:31–6 (in Japanese). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Watanabe-Fujinuma E, Origasa H, Bamber L, et al. Psychometric properties of the Japanese version of the Kansas City Cardiomyopathy Questionnaire in Japanese patients with chronic heart failure. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2020;18:236. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sinha B, Ghosal S. Sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2i) reduce hospitalization for heart failure only and have no effect on atherosclerotic cardiovascular events: a meta-analysis. Diabetes Ther. 2019;10:891–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Salah HM, Al’Aref SJ, Khan MS, et al. Effect of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors on cardiovascular and kidney outcomes-Systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized placebo-controlled trials. Am Heart J. 2021;232:10–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Tsuji S, Ishikawa T, Morii Y, et al. Cost-effectiveness of a continuous glucose monitoring mobile app for patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: analysis simulation. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22:e16053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Tangri N, Moriyama T, Schneider MP, et al. Prevalence of undiagnosed stage 3 chronic kidney disease in France, Germany, Italy, Japan and the USA: results from the multinational observational REVEAL-CKD study. BMJ Open. 2023;13:e067386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Tanaka T, Maruyama S, Chishima N, et al. Population characteristics and diagnosis rate of chronic kidney disease by eGFR and proteinuria in Japanese clinical practice: an observational database study. Sci Rep. 2024;14:5172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McEwan P, Bennett H, Khunti K, et al. Assessing the cost-effectiveness of sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors in type 2 diabetes mellitus: a comprehensive economic evaluation using clinical trial and real-world evidence. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2020;22:2364–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Isaza N, Calvachi P, Raber I, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dapagliflozin for the treatment of heart failure with reduced ejection fraction. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2114501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.McEwan P, Darlington O, Miller R, et al. Cost-effectiveness of dapagliflozin as a treatment for chronic kidney disease: a health-economic analysis of DAPA-CKD. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2022;17:1730–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.McDonagh TA, Metra M, Adamo M, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. Focused Update of the 2021 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:3627–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Marx N, Federici M, Schütt K, et al. ESC Scientific Document Group. ESC Guidelines for the management of cardiovascular disease in patients with diabetes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:4043–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Bouchi R, Kondo T, Ohta Y, et al. JDS Committee on Consensus Statement Development. A consensus statement from the Japan Diabetes Society: a proposed algorithm for pharmacotherapy in people with type 2 diabetes. J Diabetes Investig. 2023;14:151–64. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.George LK, Koshy SKG, Molnar MZ, et al. Heart failure increases the risk of adverse renal outcomes in patients with normal kidney function. Circ Heart Fail. 2017;10:e003825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Elsayed EF, Tighiouart H, Griffith J, et al. Cardiovascular disease and subsequent kidney disease. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167:1130–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Tanaka K, Watanabe T, Takeuchi A, et al; CKD-JAC Investigators. Cardiovascular events and death in Japanese patients with chronic kidney disease. Kidney Int. 2017;91:227–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maruyama S, Tanaka T, Akiyama H, et al. Cardiovascular, renal and mortality risk by the KDIGO heatmap in Japan. Clin Kidney J. 2024;17:sfae228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ohsugi M, Eiki J, Iglay K, et al. Comorbidities and complications in Japanese patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus: retrospective analyses of J-DREAMS, an advanced electronic medical records database. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2021;178:108845. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data used in the present study are available in this article or in the cited articles.