Abstract

Introduction

Adult growth hormone deficiency (GHD) is an endocrine disorder associated with increased morbidity and poor quality of life. The purpose of this study was to describe the clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and prevalence of individuals at risk for adult GHD and individuals with confirmed adult GHD in the United States (US).

Methods

Using Veradigm Network electronic health records linked to claims, this study identified adults with a high likelihood of adult GHD based on having ≥ 1 of the following between January 1, 2017 and December 31, 2021: diagnosis of hypopituitarism or ≥ 1 related condition, such as Cushing disease, ≥ 3 pituitary hormone deficiencies other than GHD, ≥ 3 pituitary hormone treatments other than growth hormone (GH), or ≥ 1 prescription for GH. Index date was the earliest qualifying event. Individuals were stratified by GH level on or before index date: confirmed adult GHD (< 3 ng/mL), at risk for adult GHD (no test result), ruled-out (≥ 3 ng/mL).

Results

US prevalence of adult GHD was estimated to be between 0.2 (confirmed) and 37.0 (confirmed + at-risk) per 100,000. Among 268 individuals with confirmed adult GHD and 54,310 at risk for adult GHD, mean age was 50 years old, and a majority were female. GH treatment was initiated in 9.7% of confirmed individuals and 3.1% of those at risk for adult GHD. Among confirmed and at-risk individuals, prevalence of endocrine-related conditions was higher in treated individuals, whereas prevalence of several metabolic and cardiovascular comorbidities was higher in those untreated. Only 32.2% of individuals who initiated treatment during the follow-up period were persistent until the end of follow-up.

Conclusions

Our findings report US prevalence of adult GHD and suggest that adult GHD is commonly underdiagnosed in the US. Factors contributing to low rates of adult GHD diagnosis and treatment warrant further research.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s12325-025-03188-6.

Keywords: Adult GHD, Prevalence, Adherence, Persistence, Comorbidities

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Adult growth hormone deficiency (GHD) is a rare endocrine disorder that may be underdiagnosed and undertreated in the United States (US) |

| The purpose of this study was to improve upon an existing algorithm for identifying patients with adult GHD in real-world data by adding laboratory testing data and then to describe the clinical characteristics, treatment patterns, and prevalence of individuals at risk for adult GHD and individuals with confirmed adult GHD in the US |

| What was learned from the study? |

| This study estimated the prevalence of adult GHD to be between 0.2 and 37.0 cases per 100,000 individuals. |

| Less than 10% of individuals with confirmed adult GHD were treated with growth hormone, while adherence to and persistence on medication was low. In a multivariable analysis, comorbid cardiovascular disease, endocrine disease, and pituitary tumors were among the factors associated with a lower likelihood of receiving growth hormone treatment. |

Introduction

Adult growth hormone deficiency (GHD) is a rare endocrine disorder characterized by inadequate growth hormone (GH) secretion during adulthood [1]. Adult GHD manifests with a range of clinical symptoms, including fatigue, decreased muscle mass, increased body fat, and alterations in bone remodeling and lipid metabolism [1–3]. These symptoms can result in complications such as fractures, cardiovascular disease, development of non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, and poor quality of life [4–7].

While some cases of adult GHD stem from the persistence of GHD that initially presented during childhood, most cases are newly acquired during adulthood as a result of damage to the pituitary gland or the hypothalamus [1]. Regardless of etiology, the primary treatment for GHD is replacement therapy using subcutaneous injections of recombinant human GH [8, 9]. Consistent use of GH therapy is associated with lower rates of fracture along with improvements in cardiovascular risk factors, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease progression, and quality of life [3, 5, 10–12]. However, most adults with GHD are not treated with GH for a variety of reasons, including the complexity of making the diagnosis, the cost of treatment, insurance coverage, and the historical need for daily injections [13]. Recently developed long-acting GH therapies may help improve patient adherence by reducing injection frequency to once weekly and by addressing issues of needle avoidance and needle fatigue [14].

Unlike childhood-onset GHD, which is characterized by a flattening of the growth curve, clinical features of adult GHD are nonspecific and can resemble aspects of normal aging and other conditions, such as metabolic syndrome, obscuring recognition and subsequent diagnosis [2]. As a result, many cases of adult GHD are never diagnosed at all or are not correctly diagnosed [15]. While the true prevalence has been difficult to estimate with certainty, the prevalence of adult GHD is generally suspected to be 2–3 per 10,000 based on the prevalence of pituitary adenomas and childhood-onset GHD persisting into adulthood [16–18].

While a few registry studies describe adults with GHD [3, 10], data from other real-world sources are limited due to the challenges in identifying patients, as there is no diagnosis code in use in the United States that is specific to adult GHD. This study aimed to fill that gap by using a modified, published algorithm to identify treated and untreated individuals with biochemically confirmed adult GHD or individuals who are at risk for adult GHD and to describe their demographic and clinical characteristics and compare these to controls without GHD [19]. The treatment patterns of GH therapy and estimates of the prevalence of adult GHD in the United States (US) are also described.

Methods

Data Source

This study leveraged electronic health record (EHR) data sourced from the Veradigm Network EHR linked to healthcare claims data from inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy encounters in the US between January 1, 2016, and December 31, 2022. The linked dataset captures detailed healthcare information for over 170 million unique patients across the US during the study period. The dataset includes individuals insured through commercial, Medicaid, and Medicare Advantage plans. The dataset was licensed for use in this publication.

The EHR data provided insights into care received at contributing outpatient facilities, such as data recorded during a primary care visit with a participating physician. This may have included current diagnoses, medical history, vital signs, laboratory results, procedures, and vaccination records. The claims data were sourced from insurance claims and provided insights into the healthcare services provided, the diagnoses supporting the use of those services, and the cost of those services. Because care received in inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy settings was captured, the claims data provided a thorough view of the care received during a period of continuous enrollment in a health insurance plan. Both EHR and claims data captured demographic data as part of routine data collection.

The linked dataset only contained de-identified data as per the de-identification standard defined in Section §164.514(a) of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) Privacy Rule. The process by which the data were de-identified is attested to through a formal determination by a qualified expert as defined in Section §164.514(b) (1) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Because this study used only de-identified patient records, it was no longer subject to the HIPAA Privacy Rule and was therefore exempt from institutional review board approval and obtaining informed consent according to US law. This study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and only used de-identified data.

Study Cohort Construction

The initial study population was selected by adapting an algorithm developed by Yuen et al. to identify individuals with a high likelihood of adult GHD in a claims dataset [19]. Specifically, Yuen et al. defined individuals who met at least one of the following four criteria during the patient selection window to have a high-likelihood of adult GHD: (1) at least one diagnosis code for hypopituitarism or related condition, such as Cushing disease, (2) at least 3 diagnosis codes for unique pituitary hormone deficiencies other than GHD, (3) at least 3 types of treatment with pituitary (or target gland) hormones other than GH and no diagnosis codes from exclusion list A, or (4) a record of GH treatment and no diagnosis codes from exclusion list B. Because Yuen et al. were not able to validate their algorithm due to the limitations of the data source used in their study, we modified their algorithm to include laboratory values to confirm adult GHD. Based on additional clinical considerations, we made a few other changes to the algorithm, particularly the inclusion of certain clinical codes to identify conditions, all of which are noted in Supplementary Table 1. The code sets and medication lists used in patient selection are listed in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Diagnosis codes used in patient selection

| Category | Conditions | ICD-10-CM | ICD-9-CM |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hypopituitarism | Hypopituitarism | E230 | 2532, 2533 |

| Adult GHD-related condition | Malignant neoplasm of pineal gland | C753 | 1944 |

| Multifocal and multisystemic (disseminated) Langerhans-cell histiocytosis | C960 | 2025 | |

| Benign neoplasm of pineal gland | D354 | 2274 | |

| Neoplasm of uncertain behavior of craniopharyngeal duct | D444 | 2370 | |

| Neoplasm of uncertain behavior of pineal gland | D445 | 2371 | |

| Acromegaly and pituitary gigantism | E220 | 2530 | |

| Drug induced hypopituitarism | E231 | 2537 | |

| Hypothalamic dysfunction, not elsewhere classified | E233 | 2539 | |

| Other disorders of pituitary gland | E236 | 2534, 2538 | |

| Disorder of pituitary gland, unspecified | E237 | ||

| Pituitary dependent Cushing disease | E240 | ||

| Other Cushing syndrome | E248 | ||

| Cushing syndrome, unspecified | E249 | 2550 | |

| Septo-optic dysplasia of brain | Q044 | ||

| Other specified congenital anomalies of brain | 7424 | ||

| Personal history of irradiation, presenting hazards to health | V153 | ||

| Pituitary hormone deficiencies | Diabetes insipidus | E232 | 2535 |

| Secondary amenorrhea | N911 | ||

| Secondary oligomenorrhea | N914 | ||

| Benign neoplasm of pituitary gland | D352 | 2273 | |

| Galactorrhea not associated with childbirth | N643 | ||

| Unspecified adrenocortical insufficiency | E2740 | ||

| Glucocorticoid deficiency | 25, 541 | ||

| Exclusion list A | Dermatitis and eczema | L20-L30 | |

| Psoriasis | L40 | ||

| Lichen planus | L43 | ||

| Bullous pemphigoid | L120 | ||

| Other hypothyroidism | E03 | 243 | |

| Primary adrenocortical insufficiency | E271 | ||

| Adrenogenital disorder, unspecified | E259 | 2552 | |

| Autoimmune hepatitis | K754 | 57, 142 | |

| Inflammatory polyarthropathies | M05-M14 | ||

| Noninfective enteritis and colitis | K50-K52 | ||

| Atrophy of vulva | N90.5 | 6241 | |

| Other inflammatory conditions of skin and subcutaneous tissue | 690–698 | ||

| Arthropathies and related disorder | 710–719 | ||

| Exclusion list B | Acromegaly and pituitary gigantism | E220 | 2530 |

| Pituitary-dependent Cushing's disease | E240 | ||

| Drug-induced Cushing's syndrome | E242 | ||

| Ectopic adrenocorticotropic hormone syndrome | E243 | ||

| Alcohol-induced pseudo-Cushing's syndrome | E244 | ||

| Other Cushing's syndrome | E248 | ||

| Cushing's syndrome, unspecified | E249 | 2550 |

GHD growth hormone deficiency, ICD-9-CM International Classification of Disease, Ninth Edition, Clinical Modification, ICD-10-CM International Classification of Disease, Tenth Edition, Clinical Modification

For this study, we used a patient selection window of January 1, 2017, to December 31, 2021. We defined the index date as the earliest date in the patient selection window on which an individual qualified for study inclusion. Individuals with a high likelihood of adult GHD were required to be 18 years old on the index date and have at least 12 months of continuous enrollment in claims data and EHR activity prior to and following the index date. The baseline period was defined as the 12 months preceding the index date, and the follow-up period was defined as the 12 months following and inclusive of the index date. The use of continuous enrollment ensured that we were capturing all inpatient, outpatient, and pharmacy healthcare encounters that were billed to insurance during the baseline and follow-up periods, and a 12-month baseline and follow-up period were used so that the study reflected annualized healthcare usage by individuals. The study design is outlined in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1.

Study design. GH growth hormone

Adult GHD Cohort Stratification

Adults who met the above criteria for a high likelihood of adult GHD were then stratified into 2 groups, confirmed adult GHD or at risk for adult GHD, depending on the availability and results of GH laboratory test results in the EHR. Individuals with a confirmatory GH laboratory result (< 3 ng/mL) anytime on or before the index date were assigned to the confirmed adult GHD cohort. Individuals without a GH laboratory result were included in the at-risk-for adult GHD cohort, and individuals with a GH test result that ruled out a diagnosis of GHD were excluded from the confirmed adult GHD or at-risk-for adult GHD cohorts. The confirmed and at-risk cohorts were further stratified by receipt of GH treatment. Individuals with any record of GH treatment in the baseline or follow-up period were considered treated, while the remaining individuals were considered untreated. Descriptive comparisons were made between these groups to better understand the differentiating characteristics of each subgroup.

Control Cohort

We constructed a control cohort by identifying all individuals with any EHR activity or claims enrollment during the patient selection window who did not meet any criteria of having a high likelihood of adult GHD. These individuals were then assigned a random index date during the patient selection window using a random number generator that generated a uniform distribution of dates between January 1, 2017, and December 31, 2021 [20]. It was required that individuals were 18 years old or older on the index date and had at least 12 months of continuous enrollment in claims data and EHR activity prior to and following the index date. Individuals with any evidence of a diagnosis of hypopituitarism or related conditions, a diagnosis of any pituitary hormone deficiency, treatment with GH, treatment with other pituitary (or target gland) hormones or vasopressin, or GH testing during the baseline or follow-up period were excluded. The final control cohort was identified by direct matching (3:1) on age and gender to individuals with a high likelihood of adult GHD.

Demographic Characteristics

We analyzed demographic characteristics, including age, sex, race, and US geographic region, on the index date.

Clinical Characteristics

Body mass index (BMI) was captured from the EHR using the value captured closest to the index date. The following clinical characteristics were analyzed during the 12-month baseline period: Deyo–Charlson comorbidity index (CCI) [21], endocrine-related conditions (adrenal insufficiency, diabetes insipidus, hypogonadism, hypopituitarism, hypothyroidism, and pituitary tumor), other conditions of interest [acromegaly, cardiovascular disease, Cushing syndrome, endocrine/metabolic disorders (diabetes mellitus, hyperlipidemia, and obesity), fractures, kidney disease, liver disease, mental health conditions, osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, respiratory disease, and sleep disorders]. Medication usage was also captured in the baseline period and included antidiabetic medications, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications, systemic corticosteroids, medications for mental health, and hormones.

Treatment Patterns

The use of GH therapies (daily injections and/or long-acting GH products) was measured in the baseline and follow-up periods. GH treatment patterns were assessed among the subset of treated individuals (across the confirmed and at-risk groups) who initiated treatment in the follow-up period and whose treatment was captured in claims, as claims data indicate that a prescription was filled, not just that the treatment was prescribed. Among these individuals, adherence was defined as the proportion of days covered (PDC) during the 12-month follow-up period. PDC was calculated as days’ supply (with days’ supply truncated upon refill) divided by the number of days between the start of GH therapy and the end of the follow-up period. An individual was considered adherent if their PDC was ≥ 0.8, meaning they had medication on hand for at least 80% of the days between their first prescription and the end of follow-up. Discontinuation was defined as having a gap in therapy of at least 60 days. Treated individuals who did not discontinue during follow-up were defined as persistent. Treatment patterns were measured from the initiation of treatment to the end of the follow-up period.

Laboratory Testing

Laboratory results in EHR during the baseline and follow-up periods were documented among individuals with confirmed adult GHD. GH test results in the baseline period, along with insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) results in the baseline and follow-up periods, were reported.

Prevalence Estimates

In order to estimate the US prevalence rate of adult GHD, 5-year weights were calculated for individuals with EHR activity during the study timeframe (1/1/2017–12/31/2021) [22]. Weights were calculated based on the 2021 Census population estimates using the following weighting factors: sex (male/female), age group (in 5-year increments), and US geography (by state) [23]. Race was excluded as a factor due to the large population of unknown race in the data source. Weights were applied to all individuals in the at-risk and confirmed adult GHD cohorts. Prevalence rates were estimated by summing these weights for each category of interest, then dividing by the corresponding categorical US adult population count.

Data Analysis

Patient characteristics are reported descriptively. For continuous variables, mean and standard deviation (SD) are reported, and for categorical variables, counts and percentages are reported. For laboratory tests with results reported as continuous measures, the median and interquartile range (IQR) are also reported.

Two multivariable models were developed to better understand this population. The first model used logistic regression to examine the likelihood of receiving GH treatment during the follow-up period among individuals with confirmed adult GHD or at risk for adult GHD who were not treated during the baseline period. The second model used logistic regression to examine the likelihood of being in the confirmed adult GHD cohort versus the at-risk-for adult GHD cohort. Both models included the demographic, clinical, and baseline medication variables listed in the study measures subsection as model covariates. The first model also used cohort as the primary predictor of interest. Results are reported as odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI).

All data analysis was conducted using SAS v.9.4 (Cary, NC, USA).

Results

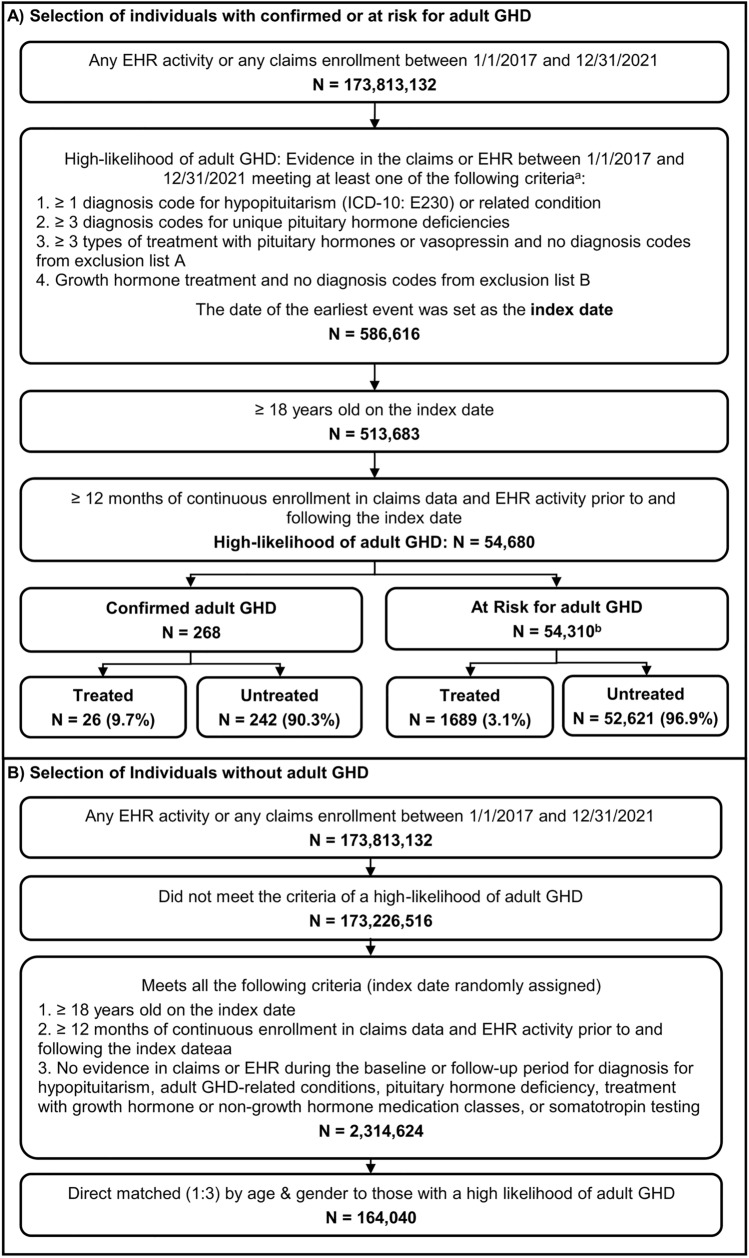

From a population of 54,680 individuals who met the modified Yuen et al. criteria for a high likelihood of adult GHD and had 12 months of baseline and follow-up data, 268 individuals with laboratory-confirmed adult GHD and 54,310 individuals at risk for adult GHD were identified, while 102 individuals were excluded due to a test result that ruled out a diagnosis of adult GHD (Fig. 2). Among these 54,578 individuals, 26 (9.7% of 268) individuals with confirmed adult GHD and 1689 (3.1% of 54,310) individuals at risk for adult GHD received GH treatment.

Fig. 2.

Selection of (A) individuals with confirmed or at risk for adult growth hormone deficiency (GHD) and (B) controls without adult GHD. EHR electronic health records; ICD-10 International Classification of Disease, Tenth Edition. aCode sets and medication lists used to assess these criteria are listed in Table 1 and Supplementary Table 2. b102 individuals who had a laboratory result that ruled out a diagnosis of adult GHD were excluded from the analysis

Over 90% of individuals with confirmed adult GHD or at risk for adult GHD qualified for study inclusion due to a diagnosis code for hypopituitarism or related conditions (Table 2). While adults with ≥ 3 pituitary deficiencies (not including GH) have a high likelihood of also having GH deficiency [24], only 2.1% of individuals with ≥ 3 diagnosis codes for unique pituitary hormone deficiencies other than GHD in the dataset received GH treatment. When restricted to individuals with confirmed adult GHD, this rose to 21.4%.

Table 2.

Selection criteria

| Confirmed adult GHD | At risk for adult GHD | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All individuals | Treated | Untreated | All individuals | Treated | Untreated | |

| n = 268 | n = 26 | n = 242 | n = 54,310 | n = 1689 | n = 52,621 | |

| Criteria #1: ≥ 1 diagnosis code for hypopituitarism or related condition | 246 (91.8%) | 13 (50.0%) | 233 (96.3%) | 50,212 (92.5%) | 521 (30.8%) | 49,691 (94.4%) |

| Criteria #2: ≥ 3 diagnosis codes for unique pituitary hormone deficiencies | 14 (5.2%) | 3 (11.5%) | 11 (4.5%) | 911 (1.7%) | 16 (0.9%) | 895 (1.7%) |

| Criteria #3: ≥ 3 types of treatment with other pituitary (or target gland) hormones or vasopressin and no diagnosis codes from exclusion list Aa | 2 (0.7%) | 1 (3.8%) | 1 (0.4%) | 2174 (4.0%) | 13 (0.8%) | 2161 (4.1%) |

| Criteria #4: Growth hormone treatment and no diagnosis codes from exclusion list Ba | 12 (4.5%) | 12 (46.2%) | 0 (0.0%) | 1177 (2.2%) | 1177 (69.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

GHD growth hormone deficiency

aCode sets and medication lists used to assess these criteria are listed in Supplementary Table 2

Baseline Characteristics

Individuals with confirmed adult GHD or at risk for adult GHD had a mean age of ~ 50 years old, and the majority were female and white (Table 3). Treated individuals tended to be younger than untreated individuals [confirmed, mean (SD): 46.7 (15.9) years vs. 48.9 (14.5) years; at-risk: 45.9 (14.3) years vs. 50.6 (15.0) years] although the effect size is small. Among individuals with confirmed adult GHD, the gender distribution was similar between the treated and untreated subgroups. However, among individuals at risk for adult GHD, a majority of treated individuals were male, whereas a majority of untreated individuals were female. The mean BMI was > 28 in all subgroups.

Table 3.

Demographic and physical characteristics

| Confirmed adult GHD | At risk for adult GHD | Controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All individuals | Treated | Untreated | All individuals | Treated | Untreated | All individuals | |

| n = 268 | n = 26 | n = 242 | n = 54,310 | n = 1689 | n = 52,621 | n = 164,040 | |

| Age, mean (SD) | 48.6 (14.6) | 46.7 (15.9) | 48.9 (14.5) | 50.4 (15.0) | 45.9 (14.3) | 50.6 (15.0) | 50.4 (15.0) |

| Female Sex, n (%) | 166 (61.9%) | 16 (61.5%) | 150 (62.0%) | 31,915 (58.8%) | 786 (46.5%) | 31,129 (59.2%) | 96,405 (58.8%) |

| Race, n (%) | |||||||

| White | 177 (66.0%) | 16 (61.5%) | 161 (66.5%) | 31,978 (58.9%) | 1098 (65.0%) | 30,880 (58.7%) | 86,765 (52.9%) |

| Black | 15 (5.6%) | 1 (3.8%) | 14 (5.8%) | 5432 (10.0%) | 89 (5.3%) | 5343 (10.2%) | 18,977 (11.6%) |

| Asian | 13 (4.9%) | 0 (0.0%) | 13 (5.4%) | 2835 (5.2%) | 91 (5.4%) | 2744 (5.2%) | 12,127 (7.4%) |

| Other | 45 (16.8%) | 5 (19.2%) | 40 (16.5%) | 8490 (15.6%) | 220 (13.0%) | 8270 (15.7%) | 26,189 (16.0%) |

| Unknown/not reported | 18 (6.7%) | 4 (15.4%) | 14 (5.8%) | 5575 (10.3%) | 191 (11.3%) | 5384 (10.2%) | 19,982 (12.2%) |

| US geographic region, n (%) | |||||||

| Northeast | 41 (15.3%) | 3 (11.5%) | 38 (15.7%) | 8074 (14.9%) | 195 (11.6%) | 7879 (15.0%) | 26,298 (16.0%) |

| Midwest | 40 (14.9%) | 2 (7.7%) | 38 (15.7%) | 10,813 (19.9%) | 330 (19.5%) | 10,483 (19.9%) | 36,245 (22.1%) |

| South | 92 (34.3%) | 13 (50.0%) | 79 (32.6%) | 18,520 (34.1%) | 510 (30.2%) | 18,010 (34.2%) | 47,727 (29.1%) |

| West | 95 (35.4%) | 8 (30.8%) | 87 (36.0%) | 16,107 (29.7%) | 653 (38.7%) | 15,454 (29.4%) | 53,308 (32.5%) |

| Other/unknown | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 796 (1.5%) | 1 (0.1%) | 795 (1.5%) | 462 (0.3%) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 29.9 (6.8) | 29.5 (5.7) | 30.0 (6.9) | 30.4 (6.3) | 28.4 (6.4) | 30.5 (6.3) | 28.9 (6.0) |

GHD growth hormone deficiency, SD standard deviation, US United States

Overall, 60.1% of confirmed adult GHD individuals and 44.2% of individuals at risk for adult GHD had a diagnosis of an endocrine-related condition in the baseline period, and endocrine-related conditions were more common among treated individuals than among untreated individuals (Fig. 3). Pituitary tumors were most common among untreated individuals with confirmed adult GHD compared to treated confirmed, treated at-risk, or untreated at-risk individuals (36.4% vs. 10.1–26.9%). In contrast, other investigated endocrine-related conditions were most common among treated individuals with confirmed adult GHD compared to other subgroups: adrenal insufficiency (38.5% vs. 4.9–11.8%), diabetes insipidus (19.2% vs. 1.3–4.9%), hypogonadism (30.8% vs. 17.0–26.2%), hypopituitarism (73.1% vs. 6.0–36.8%), and hypothyroidism (61.5% vs. 28.4–36.8%).

Fig. 3.

Baseline prevalence of endocrine-related conditions. GHD growth hormone deficiency

Confirmed and at-risk adult GHD individuals had higher baseline rates of conditions associated with adult GHD compared to controls without adult GHD (Table 4). For example, 45.1% of individuals with confirmed adult GHD and 52.1% of individuals at risk for adult GHD had a diagnosis of cardiovascular disease compared to 34.2% of the control cohort. Similar trends were observed in other conditions, such as hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and fractures. Cardiovascular disease, hyperlipidemia, obesity, mental health conditions, and several other adult GHD-associated conditions were more common among untreated cohorts than among the respective treated cohorts.

Table 4.

Baseline clinical characteristics

| Confirmed adult GHD | At risk for adult GHD | Controls | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| All individuals | Treated | Untreated | All individuals | Treated | Untreated | All individuals | |

| n = 268 | n = 26 | n = 242 | n = 54,310 | n = 1689 | n = 52,621 | n = 164,040 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index (Mean, SD) | 1.3 (1.9) | 0.8 (1.2) | 1.4 (2.0) | 1.7 (2.3) | 1.7 (2.6) | 1.7 (2.3) | 0.8 (1.6) |

| Conditions associated with adult GHD (n, %) | |||||||

| Acromegaly | 27 (10.1%) | 0 (0.0%) | 27 (11.2%) | 389 (0.7%) | 4 (0.2%) | 385 (0.7%) | 0 (0.0%) |

| Cardiovascular diseasea | 121 (45.1%) | 9 (34.6%) | 112 (46.3%) | 28,317 (52.1%) | 611 (36.2%) | 27,706 (52.7%) | 56,080 (34.2%) |

| Cushing syndrome | 9 (3.4%) | 2 (7.7%) | 7 (2.9%) | 879 (1.6%) | 21 (1.2%) | 858 (1.6%) | 2 (0.0%) |

| Endocrine/metabolic disordersb | 171 (63.8%) | 14 (53.8%) | 157 (64.9%) | 34,948 (64.3%) | 843 (49.9%) | 34,105 (64.8%) | 69,255 (42.2%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 63 (23.5%) | 6 (23.1%) | 57 (23.6%) | 14,323 (26.4%) | 258 (15.3%) | 14,065 (26.7%) | 27,064 (16.5%) |

| Hyperlipidemia | 124 (46.3%) | 9 (34.6%) | 115 (47.5%) | 25,619 (47.2%) | 615 (36.4%) | 25,004 (47.5%) | 50,031 (30.5%) |

| Obesity | 84 (31.3%) | 5 (19.2%) | 79 (32.6%) | 18,802 (34.6%) | 338 (20.0%) | 18,464 (35.1%) | 30,265 (18.4%) |

| Fractures | 19 (7.1%) | 3 (11.5%) | 16 (6.6%) | 3089 (5.7%) | 105 (6.2%) | 2984 (5.7%) | 4532 (2.8%) |

| Kidney disease | 17 (6.3%) | 3 (11.5%) | 14 (5.8%) | 4843 (8.9%) | 77 (4.6%) | 4766 (9.1%) | 7808 (4.8%) |

| Liver disease | 43 (16.0%) | 1 (3.8%) | 42 (17.4%) | 7860 (14.5%) | 191 (11.3%) | 7669 (14.6%) | 10,908 (6.6%) |

| Mental health conditionsc | 120 (44.8%) | 8 (30.8%) | 112 (46.3%) | 23,483 (43.2%) | 701 (41.5%) | 22,782 (43.3%) | 37,031 (22.6%) |

| Osteoarthritis | 35 (13.1%) | 3 (11.5%) | 32 (13.2%) | 7531 (13.9%) | 184 (10.9%) | 7347 (14.0%) | 8445 (5.1%) |

| Osteoporosis | 26 (9.7%) | 2 (7.7%) | 24 (9.9%) | 3440 (6.3%) | 94 (5.6%) | 3346 (6.4%) | 4113 (2.5%) |

| Respiratory disordersd | 30 (11.2%) | 2 (7.7%) | 28 (11.6%) | 7961 (14.7%) | 180 (10.7%) | 7781 (14.8%) | 9500 (5.8%) |

| Sleep disorders | 73 (27.2%) | 6 (23.1%) | 67 (27.7%) | 16,021 (29.5%) | 451 (26.7%) | 15,570 (29.6%) | 17,239 (10.5%) |

GHD growth hormone deficiency, SD standard deviation

aAtrial fibrillation, cerebrovascular disease, heart failure, hypertensive disorder, ischemic heart disease, peripheral vascular disease, pulmonary embolism, or venous thrombosis

bDiabetes mellitus, eating disorders, hyperlipidemia, metabolic syndrome X, or obesity

cAnxiety, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, bipolar disorder, or depression

dAcute respiratory disease, chronic obstructive lung disease, or pneumonia

Overall, 69.2% of treated individuals with confirmed adult GHD and 43.8% of treated individuals at risk for adult GHD had evidence of GH treatment during the baseline period (Fig. 4). Baseline use of other pituitary (or target gland) hormones, such as estrogen, was more common among GH-treated individuals than individuals not treated with GH, whereas baseline use of anti-diabetic medications was more common among untreated individuals among both confirmed and at-risk adult GHD individuals.

Fig. 4.

Baseline medicationsa. GHD growth hormone deficiency. aAmong patients with confirmed adult GHD or at-risk of adult GHD who did or did not receive growth hormone treatment at some point during the baseline or follow-up period

GH Testing and IGF-1 Values

In order to qualify for the confirmed adult GHD cohort, individuals were required to have a GH level < 3 ng/mL, confirming the diagnosis of adult GHD, at some point on or prior to the index date; however, only 39.9% of those test results were captured during the 12-month baseline period. For those with test results during the 12-month baseline period, the mean (SD) GH value was 0.60 (0.99) ng/mL (Table 5).

Table 5.

Somatotropin and insulin-like growth factor-1 (IGF-1) testing results

| Confirmed adult GHD | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| All individuals | Treated | Untreated | |

| n = 268 | n = 26 | n = 242 | |

| Laboratory testing in the baseline period | |||

| Growth hormone, ng/mL (n, %) | 107 (39.9%) | 15 (57.7%) | 92 (38.0%) |

| Mean, SD | 0.60 (0.99) | 0.32 (0.64) | 0.64 (1.03) |

| Median, IQR | 0.2 (0.00–0.85) | 0.1 (0.00–0.25) | 0.2 (0.00–0.93) |

| Insulin-like growth factor-1, ng/ml (n, %) | 98 (36.6%) | 14 (53.8%) | 84 (34.7%) |

| Mean, SD | 165.5 (121.7) | 117.7 (61.6) | 173.4 (127.5) |

| Median, IQR | 131 (93.5–227.8) | 101 (84.3–141.3) | 141 (95.8–231.3) |

| Insulin-like growth factor-I, SDS (n, %) | 33 (12.3%) | 6 (23.1%) | 27 (11.2%) |

| Absolute value ≤ 2 | 25 (75.8%) | 5 (83.3%) | 20 (74.1%) |

| Absolute value > 2 | 8 (24.2%) | 1 (16.7%) | 7 (25.9%) |

| Laboratory testing in the follow-up period | |||

| Insulin-like growth factor-1, ng/ml (n, %) | 72 (26.9%) | 13 (50.0%) | 59 (24.4%) |

| Mean, SD | 138.8 (103.1) | 135.6 (74.8) | 139.5 (108.9) |

| Median, IQR | 124 (65.0–181.8) | 126 (98.0–153.0) | 123 (60.1–185.0) |

| Insulin-like growth factor-1, SDS (n, %) | 22 (8.2%) | 6 (23.1%) | 16 (6.6%) |

| Absolute value ≤ 2 | 17 (77.3%) | 5 (83.3%) | 12 (75.0%) |

| Absolute value > 2 | 5 (22.7%) | 1 (16.7%) | 4 (25.0%) |

GHD growth hormone deficiency, IQR interquartile range, SD standard deviation, SDS standard deviation score

IGF-1 test results in the baseline and follow-up period were available for a subset of individuals, and their results tended to fall within the reference range for healthy individuals.

GH Treatment Patterns

Adherence to daily injections of GH was low among individuals with confirmed adult GHD or at risk for adult GHD who initiated treatment during the follow-up period (Table 6). A majority of individuals had a PDC < 0.5, and only 25.9% met the criteria for “adherent” (PDC ≥ 0.8). Only 32.2% of individuals who initiated treatment during the follow-up period were persistent until the end of the follow-up period. Among those who were non-persistent, the mean (SD) time to discontinuation was 75.5 (85.1) days. While a long-acting GH formulation (approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for pediatric GHD) was included in the treatment patterns analysis in case it was prescribed off-label, no individuals in this dataset received a long-acting formulation during the study period.

Table 6.

Recombinant human growth hormone treatment patterns among those who initiated treatment during the follow-up period

| Confirmed or at risk for adult GHD | |

|---|---|

| n = 509 | |

| Adherence | |

| Proportion of days covered (PDC), mean (SD) | 0.42 (0.36) |

| Median | 0.32 |

| PDC categories, n (%) | |

| 0–0.49 | 300 (58.9%) |

| 0.50–0.59 | 20 (3.9%) |

| 0.60–0.69 | 30 (5.9%) |

| 0.70–0.79 | 27 (5.3%) |

| 0.80–0.89 | 49 (9.6%) |

| 0.90–1.00 | 83 (16.3%) |

| Persistence | |

| Persistent on treatment, n (%) | 164 (32.2%) |

| Days to discontinuationa mean (SD) | 75.5 (85.1) |

GHD growth hormone deficiency, SD standard deviation

aAmong those who discontinued (n = 345)

Results of Multivariable Analysis

In the analysis of the likelihood of receiving GH treatment, the OR (95% CI) of receiving treatment was 2.11 (1.02–4.36) for individuals with confirmed adult GHD relative to individuals at risk for adult GHD (Supplementary Table 3). Other baseline factors significantly associated with higher odds [OR (95% CI)] of receiving GH treatment were residing in the Western (relative to the Southern) part of the US [1.29 (1.10–1.51)], BMI < 25 kg/m2 (relative to a BMI of 30–39.9 kg/m2) [BMI < 18.5: 2.43 (1.52–3.87); BMI 18.5–24.9: 1.70 (1.35–2.13)], higher baseline CCI [1.19 (1.15–1.23)], diabetes insipidus [1.65 (1.03–2.66)], receipt of other pituitary (or target gland) hormone replacement therapies [2.53 (2.19–2.94)], and concomitant adult GHD medications [1.53 (1.22–1.92)]. Baseline factors significantly associated with a lower likelihood of receiving GH treatment were Black race (relative to white) [0.70 (0.52–0.94)] and comorbidities of pituitary tumors [0.44 (0.32–0.60)], cardiovascular disease [0.63 (0.54–0.75)], endocrine/metabolic disorders [0.62 (0.54–0.75)], kidney disease [0.51 (0.37–0.81)], liver disease [0.79 (0.64–0.98)], osteoporosis [0.55 (0.37–0.81)], or respiratory disorders [0.76 (0.61–0.96)].

In an analysis of the likelihood of having confirmed adult GHD rather than being at risk for adult GHD, baseline diagnoses associated with a higher likelihood of confirmed AGHD included adrenal insufficiency [1.74 (1.15–2.63)], hypopituitarism [1.70 (1.17–2.46)], pituitary tumors [3.73 (2.84–4.90)], acromegaly [8.64 (5.53–13.49)], and osteoporosis [1.60 (1.03–2.50]; Supplementary Table 4). Factors associated with a lower likelihood of confirmed adult GHD included Black race (relative to white) [0.55 (0.32–0.95)] and BMI not reported (relative to a BMI of 30–39.9 kg/m2) [0.24 (0.16–0.35)].

US Prevalence Estimates

We estimated the US prevalence of confirmed adult GHD to be 0.2 per 100,000 and the combined prevalence of confirmed adult GHD and at risk for adult GHD to be 37 per 100,000 (Table 7). The combined prevalence was higher among females than males (40.1 vs. 33.7 per 100,000 individuals) and peaked among those aged 45–54 years (60.2 per 100,000) (Fig. 5).

Table 7.

Estimated United States prevalence of adult growth hormone deficiency (GHD)

| Prevalence (per 100,000) | |

|---|---|

| Confirmed adult GHD | 0.2 |

| At risk for adult GHD | 36.8 |

| Combined (confirmed + at risk) | 37.0 |

| Combined adult GHD prevalence by sex | |

| Female | 40.1 |

| Male | 33.7 |

Fig. 5.

Estimated US prevalence of adult growth hormone disorder (GHD) across age groups

Discussion

This study of 54,310 individuals at risk for adult GHD and 268 individuals with biochemically confirmed adult GHD presents a broad picture of the US population who could benefit from a thorough endocrine evaluation and, potentially, GH replacement therapy. During the study period, only 3.1% of individuals at risk for adult GHD and 9.7% of individuals with confirmed adult GHD received GH treatment. At baseline, untreated confirmed and at-risk individuals had a higher prevalence of many comorbidities compared to the respective treated individuals, including a higher prevalence of cardiovascular disease (confirmed: Δ11.7%, and at risk: Δ16.5%), obesity (Δ13.4% and Δ15.1%), diabetes mellitus (Δ0.5% and Δ11.5%), and hyperlipidemia (Δ12.9% and Δ11.1%). In contrast, treated individuals with confirmed AGHD had the highest prevalence of many endocrine-related conditions, suggesting that this subset of individuals received a full endocrine work-up. In the multivariable analysis, individuals with comorbidities such as pituitary tumors, cardiovascular disease, kidney disease, and liver disease had significantly lower odds of receiving GH treatment. Taken together, these findings suggest that in some individuals, competing comorbidities may take priority in terms of treatment compared to treatment of adult GHD.

Before applying continuous enrollment criteria, 513,683 individuals who met the criteria for a high likelihood of adult GHD were identified. This represented roughly 0.3% of the population of the Veradigm Linked Claims data source with activity during the study period, and is consistent with the 0.5% of the Marketscan data source reported by Yuen et al. [19]. After applying the enrollment restrictions and weighted adjustments based on age, sex, and geography, prevalence estimates in this study ranged from 0.2 per 100,000 for confirmed adult GHD up to 37.0 per 100,000 for confirmed or at-risk adult GHD. These estimates potentially represent lower and upper bounds for the true prevalence of adult GHD in the US. The rate using confirmed individuals is likely an underestimate because laboratory results are only available for a subset of the suspected population, whereas the rate using confirmed and at-risk individuals is likely an overestimate because it is unlikely that everyone identified as at-risk for adult GHD actually has adult GHD. The prevalence range identified in this study is consistent with prior publications on European populations, which have reported incidence estimates of 1 to 4 per 100,000 and prevalence estimates of 29 to 45.5 per 100,000 [25, 26].

GH therapy has been FDA-approved for adult GHD since 1996 in the US [27, 28]. Despite recommendations from major society guidelines for GH treatment in adult GHD individuals without contra-indications [8, 9, 29], only 9.7% of individuals with confirmed adult GHD received GH treatment during the study period in this analysis. For additional context, we evaluated the incidence of GH treatment among individuals at risk for adult GHD and among those with ≥ 3 pituitary deficiencies and found them to be 3.1% and 2.1%, respectively. This is despite 7.0% of individuals at risk for adult GHD having a diagnosis of hypopituitarism and previous research demonstrating that patients with ≥ 3 pituitary deficiencies have a very high likelihood of adult GHD with an accuracy of 95% [24]. The multivariable analysis found that males were more likely to receive treatment, whereas Black individuals were less likely to receive treatment. Interestingly, these sex and race differences are consistent with those observed in an earlier study of individuals with childhood-onset GHD [30].

Finally, adherence to and persistence of GH treatment were low, with only 25% of individuals remaining adherent (PDC ≥ 0.8) and a large proportion (68%) discontinuing GH treatment during follow-up. The average time to discontinuation was 75.5 days. Compared to a prior retrospective analysis of individuals with childhood-onset GHD, adherence and persistence were lower among adults than among those under 18 years of age [30]. Lower adherence among adults compared to children has also been observed in studies of daily injections of GH administered via the Easypod device, which enables objective measurement of adherence [31].

One challenge of studying adult GHD using EHR and claims data is that there is no diagnosis code used in the US that is specific to the condition. While adult GHD may fit under the broader category of hypopituitarism, which has a specific diagnosis code, hypopituitarism encompasses a spectrum of pituitary deficiencies that may or may not include GHD [32]. Notably, only 18.7% of individuals with biochemically confirmed adult GHD in this study had a baseline diagnosis of hypopituitarism, but this increased to 73.1% when restricted to the subset of confirmed adult GHD individuals who received GH treatment. Similarly, 7.0% of the overall at-risk population and 36.8% of the treated at-risk population had a diagnosis of hypopituitarism. However, they did not have GH test results, so a diagnosis of adult GHD could not be confirmed. Without a definitive diagnosis code for adult GHD, laboratory results provide essential confirmation of the diagnosis to facilitate building a small but clean study cohort from the larger population of individuals with a likelihood of adult GHD according to the modified claims-based algorithm.

Future work should focus on refining the patient selection algorithm and understanding the root cause of underdiagnosis, undertreatment, low adherence, high discontinuation, and any relationship between these factors. Possible reasons for undertreatment include the complexity of the diagnostic process, prioritization of treating other comorbidities, difficulty in measuring the quality-of-life benefits of treatment over time, and varying physician perspectives around the role of GH replacement therapy in the treatment of adult GHD [12, 33]. Physicians may also have concerns related to tumor recurrence among individuals with a history of cancer [34].

Strengths and Limitations

The strengths of this study include the use of a large geographically distributed US population that is sampled from all 50 states. In addition, the use of a linked database containing both EHR and claims data ensures that both the clinical richness from EHR sources and the comprehensive view of patient care provided by claims data during a period of continuous enrollment is available. In particular, as the algorithm developed by Yuen et al. has not been validated against a gold standard [19], the availability of laboratory results data allowed us to confirm the adult GHD diagnosis in a subset of individuals. Furthermore, the stratification of patient cohorts into at-risk versus confirmed and treated versus untreated gives a more complete understanding of adult GHD and treatment management.

This study has limitations which should be considered when interpreting the results, including considerations common to all studies using routinely collected healthcare data, such as data entry errors, missing data, and coding issues. Limitations include the fact that the adult GHD diagnosis could not be confirmed in a majority of individuals due to low rates of GH testing and low availability of test results. For this reason, our estimation of the prevalence of confirmed adult GHD is likely an underestimate, and we included the prevalence of at-risk adult GHD to provide potential upper and lower bounds for the prevalence estimates.

In addition, less than 5% of reported GH test results were documented with Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC) specific to a GH stimulation test. The vast majority were documented using the nonspecific LOINC code 2963-7 [somatotropin (mass/volume) in serum or plasma], which can be used for both stimulation tests and random sample tests. The overreliance in real-world clinical practice on less specific codes, even when more specific codes are available, has been documented in a range of clinical specialties [35–37]. In this study, the impact would be misclassification of at-risk individuals as confirmed individuals and a narrowing of the difference between the two groups.

Another limitation is that treatment patterns could only be measured for the subset of individuals with claims records of GH treatment, as EHR data capture the initial prescribing event but do not capture prescription fills and refills as those take place at the pharmacy. The treatment pattern results were based on formulations requiring daily injections. The availability of new long-acting formulations may impact patient adherence and persistence. Furthermore, the results may not be applicable to countries other than the US and may not extend to the full US population because the dataset included only insured individuals, whether through commercial, Medicaid, or Medicare Advantage plans; however, 92% of people in the US had health insurance in 2022 [38]. As the dataset captured a convenience sample of the US population, there may be unobserved selection bias.

There are also limitations to the prevalence analysis. Specifically, as race is poorly captured in the EHR, race was not included as a weighting factor, and this may impact the accuracy of the weights. Second, state of residence was used as the geographic factor rather than the 5-digit zip code as this level of granularity is not available due to de-identification standards. Finally, factors such as educational attainment and income level could not be included in the weighting as these variables were not available in the dataset.

Conclusions

This analysis of a large, insured population in the US found that most individuals with confirmed adult GHD remain untreated, and that adherence and persistence were low among treated individuals. Furthermore, substantially higher proportions of clinical conditions related to metabolic and cardiovascular function were observed among the untreated cohort (across the confirmed and at-risk groups), supporting the need for improved diagnosis and management of this disease. Future research should explore the factors driving underdiagnosis and undertreatment, including whether adherence and persistence measures are influenced by the availability of long-acting GH formulations.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author Contribution

Andrew R. Hoffman, Subhara Raveendran, Janna Manjelievskaia, Allison S. Komirenko, Machaon Bonafede, Paul Miner, and Alden R. Smith contributed to the conceptualization of the study. Isabelle Winer and Jennifer Cheng were responsible for data handling and formal analysis of the data. Jessamine P. Winer-Jones wrote the first draft of the manuscript and was responsible for data visualization. All authors contributed to the development of the methodology implemented in the study, interpretation of the results, and writing and revising of the manuscript. All authors approved the final submitted version of the manuscript.

Funding

This study was funded by Ascendis Pharma, Inc. Palo Alto, CA, USA. The journal’s Rapid Service and Open Aceess Fees were also funded by Ascendis Pharma, Inc.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study were used under license from Veradigm. Due to data use agreements and its proprietary nature, restrictions apply regarding the availability of the data. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.

Data Availability

The data that support the findings of this study were used under license from Veradigm. Due to data use agreements and its proprietary nature, restrictions apply regarding the availability of the data. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.

Code Availability

The data that support the findings of this study were used under license from Veradigm. Due to data use agreements and its proprietary nature, restrictions apply regarding the availability of the data. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Dr. Andrew R. Hoffman has received compensation for consulting services provided to Ascendis Pharma, Inc. This work was not done as part of Dr. Andrew R. Hoffman’s Stanford duties and responsibilities. Janna Manjelievskaia, Isabelle Winer, Jennifer Cheng, Machaon Bonafede, and Jessamine P. Winer-Jones are employees of Veradigm, which received funding from Ascendis Pharma to conduct this study. Subhara Raveendran, Allison S. Komirenko, Paul Miner, and Alden R. Smith are employees of Ascendis Pharma.

Ethics/Ethical Approval

The linked dataset used in this study contained only de-identified data as per the de-identification standard defined in Section §164.514(a) of the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act of 1996 (HIPAA) Privacy Rule. The process by which the data were de-identified is attested to through a formal determination by a qualified expert as defined in Section §164.514(b) (1) of the HIPAA Privacy Rule. Because this study used only de-identified patient records, it was no longer subject to the HIPAA Privacy Rule and was therefore exempt from institutional review board approval and obtaining informed consent according to US law. This study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki and only used de-identified data.

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: A portion of this work has been previously presented at the ENDO 2023, June 15–18, Chicago, IL. Citation: Hoffman AR, Raveendran S, Manjelievskaia J, Komirenko A, Bonafede M, Winer I, et al. Prevalence of comorbidities among treated and untreated adults with suspected growth hormone deficiency. J Endocr Soc. 2023;7(Supplement_1), bvad114.1344.

References

- 1.Melmed S. Pathogenesis and diagnosis of growth hormone deficiency in adults. New Engl J Med. 2019;380(26):2551–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cuneo RC, Salomon F, McGauley GA, Sönksen PH. The growth hormone deficiency syndrome in adults. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 1992;37(5):387–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Biller BMK, Höybye C, Ferran JM, Kelepouris N, Nedjatian N, Olsen AH, et al. Long-term effectiveness and safety of GH replacement therapy in adults ≥60 years: data from NordiNet® IOS and ANSWER. J Endocr Soc. 2023;7(6):bvad054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chanson P. The heart in growth hormone (GH) deficiency and the cardiovascular effects of GH. Ann Endocrinol (Paris). 2021;82(3–4):210–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nishizawa H, Iguchi G, Murawaki A, Fukuoka H, Hayashi Y, Kaji H, et al. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease in adult hypopituitary patients with GH deficiency and the impact of GH replacement therapy. Eur J Endocrinol. 2012;167(1):67–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kołtowska-Haggstrom M, Hennessy S, Mattsson AF, Monson JP, Kind P. Quality of life assessment of growth hormone deficiency in adults (QoL-AGHDA): comparison of normative reference data for the general population of England and Wales with results for adult hypopituitary patients with growth hormone deficiency. Horm Res. 2005;64(1):46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vestergaard P, Jørgensen JOL, Hagen C, Hoeck HC, Laurberg P, Rejnmark L, et al. Fracture risk is increased in patients with GH deficiency or untreated prolactinomas—a case–control study. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2002;56(2):159–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Yuen KCJ, Biller BMK, Radovick S, Carmichael JD, Jasim S, Pantalone KM, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology guidelines for management of growth hormone deficiency in adults and patients transitioning from pediatric to adult care. Endocr Pract. 2019;25(11):1191–232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ho KKY, 2007 GH Deficiency Consensus Workshop Participants. Consensus guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of adults with GH deficiency II: a statement of the GH Research Society in association with the European Society for Pediatric Endocrinology, Lawson Wilkins Society, European Society of Endocrinology, Japan Endocrine Society, and Endocrine Society of Australia. Eur J Endocrinol. 2007;157(6):695–700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Weber MM, Gordon MB, Höybye C, Jørgensen JOL, Puras G, Popovic-Brkic V, et al. Growth hormone replacement in adults: Real-world data from two large studies in US and Europe. Growth Horm IGF Res. 2020;50:71–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mo D, Fleseriu M, Qi R, Jia N, Child CJ, Bouillon R, et al. Fracture risk in adult patients treated with growth hormone replacement therapy for growth hormone deficiency: a prospective observational cohort study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2015;3(5):331–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Burman P, Broman JE, Hetta J, Wiklund I, Erfurth EM, Hagg E, et al. Quality of life in adults with growth hormone (GH) deficiency: response to treatment with recombinant human GH in a placebo-controlled 21-month trial. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80(12):3585–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Yuen KCJ, Llahana S, Miller BS. Adult growth hormone deficiency: clinical advances and approaches to improve adherence. Expert Rev Endocrinol Metab. 2019;14(6):419–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Yuen KCJ, Miller BS, Boguszewski CL, Hoffman AR. Usefulness and potential pitfalls of long-acting growth hormone analogs. Front Endocrinol [Internet]. 2021. 10.3389/fendo.2021.637209. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hoffman AR, Mathison T, Andrews D, Murray K, Kelepouris N, Fleseriu M. Adult growth hormone deficiency: diagnostic and treatment journeys from the patients’ perspective. J Endocr Soc. 2022;6(7):bvac077. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Daly AF, Beckers A. The epidemiology of pituitary adenomas. Endocrinol Metab Clin N Am. 2020;49(3):347–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fernandez A, Karavitaki N, Wass JAH. Prevalence of pituitary adenomas: a community-based, cross-sectional study in Banbury (Oxfordshire, UK). Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2010;72(3):377–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Feldt-Rasmussen U, Klose M. Adult growth hormone deficiency-clinical management. In: Levy M, Korbonits M, editors. Pituitary disease and neuroendocrinology [Internet]. South Dartmouth (MA): MDText.com, Inc.; 2022 [cited 2023 Oct 18]. (Endotext). http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK425701/.

- 19.Yuen KCJ, Birkegard AC, Blevins LS, Clemmons DR, Hoffman AR, Kelepouris N, et al. Development of a novel algorithm to identify people with high likelihood of adult growth hormone deficiency in a US healthcare claims database. Int J Endocrinol. 2022;2022:7853786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Kadakia A, Brady BL, Dembek C, Williams GR, Kent JM. The incidence and economic burden of extrapyramidal symptoms in patients with schizophrenia treated with second generation antipsychotics in a Medicaid population. J Med Econ. 2022;25(1):87–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Quan H, Li B, Couris CM, Fushimi K, Graham P, Hider P, et al. Updating and validating the Charlson Comorbidity Index and score for risk adjustment in hospital discharge abstracts using data from 6 countries. Am J Epidemiol. 2011;173(6):676–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Wasser T, Wu B, Ycas JW, As P, Tunceli O. Applying weighting methodologies to a commercial database to project US Census demographic data. 2015;3(3):33–8.

- 23.United States Census Bureau. Census Bureau Tables [Internet]. https://data.census.gov/table. Accessed 6 Dec 2023.

- 24.Hartman ML, Crowe BJ, Biller BMK, Ho KKY, Clemmons DR, Chipman JJ, et al. Which patients do not require a GH stimulation test for the diagnosis of adult GH deficiency? J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;87(2):477–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stochholm K, Gravholt CH, Laursen T, Jørgensen JO, Laurberg P, Andersen M, et al. Incidence of GH deficiency—a nationwide study. Eur J Endocrinol. 2006;155(1):61–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Regal M, Páramo C, Sierra SM, Garcia-Mayor RV. Prevalence and incidence of hypopituitarism in an adult Caucasian population in northwestern Spain. Clin Endocrinol (Oxf). 2001;55(6):735–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Center for Drug Evaluation and Research. Approval package for humatrope [Internet]. Rockville, MD: Food and Drug Administration; 1997 Mar. Report No.: 019640/S018. https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/97/020280s008.pdf. Accessed 10 Dec 2024.

- 28.Webb SM, Strasburger CJ, Mo D, Hartman ML, Melmed S, Jung H, et al. Changing patterns of the adult growth hormone deficiency diagnosis documented in a decade-long global surveillance database. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2009;94(2):392–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Molitch ME, Clemmons DR, Malozowski S, Merriam GR, Vance ML, Endocrine Society. Evaluation and treatment of adult growth hormone deficiency: an Endocrine Society clinical practice guideline. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2011;96(6):1587–609. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kaplowitz P, Manjelievskaia J, Lopez-Gonzalez L, Morrow CD, Pitukcheewanont P, Smith A. Economic burden of growth hormone deficiency in a US pediatric population. J Manag Care Spec Pharm. 2021;27(8):1118–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mancini A, Vergani E, Bruno C, Giavoli C, Spaziani M, Isidori AM, et al. The adult growth hormone multicentric retrospective observational study: a 24-month Italian experience of adherence monitoring via Easypod™ of recombinant growth hormone treatment in adult GH deficiency. Front Endocrinol (Lausanne). 2023;14:1298775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schneider HJ, Aimaretti G, Kreitschmann-Andermahr I, Stalla GK, Ghigo E. Hypopituitarism. Lancet. 2007;369(9571):1461–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jørgensen JOL, Johannsson G, Barkan A. Should patients with adult GH deficiency receive GH replacement? Eur J Endocrinol. 2021;186(1):D1-15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boguszewski MCS, Boguszewski CL, Chemaitilly W, Cohen LE, Gebauer J, Higham C, et al. Safety of growth hormone replacement in survivors of cancer and intracranial and pituitary tumours: a consensus statement. Eur J Endocrinol. 2022;186(6):P35-52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sabatino MJ, Burroughs PJ, Moore HG, Grauer JN. Spine coding transition from ICD-9 to ICD-10: not taking advantage of the specificity of a more granular system. N Am Spine Soc J. 2020;1(4): 100035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Hellman JB, Lim MC, Leung KY, Blount CM, Yiu G. The impact of conversion to International Classification of Diseases, 10th revision (ICD-10) on an academic ophthalmology practice. Clin Ophthalmol. 2018;18(12):949–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Coleman BC, Goulet JL, Higgins DM, Bathulapalli H, Kawecki T, Ruser CB, et al. ICD-10 coding of musculoskeletal conditions in the Veterans Health Administration. Pain Med. 2021;22(11):2597–603. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Keisler-Starkey K, Bunch LN, Lindstrom RA. Health insurance coverage in the United States: 2022 [Internet]. Washington, DC.: United States Census Bureau; 2023 Aug p. P60–281. https://www.census.gov/content/dam/Census/library/publications/2023/demo/p60-281.pdf.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study were used under license from Veradigm. Due to data use agreements and its proprietary nature, restrictions apply regarding the availability of the data. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.

The data that support the findings of this study were used under license from Veradigm. Due to data use agreements and its proprietary nature, restrictions apply regarding the availability of the data. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.

The data that support the findings of this study were used under license from Veradigm. Due to data use agreements and its proprietary nature, restrictions apply regarding the availability of the data. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.