Abstract

Although pathological complete response (pCR) and major pathological response (MPR) rates of neoadjuvant immunotherapy combined with chemotherapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) trials remain suboptimal, emerging evidence highlights the synergistic potential of combining low-dose radiotherapy with immunotherapy to promote the efficacy of immunotherapy. This phase II, open-label, single-arm, multicenter trial (NCT05343325) enrolled 28 patients with untreated stage III-IVB HNSCC (NeoRTPC02). Patients received neoadjuvant low-dose radiotherapy, the programmed death-1 (PD-1) inhibitor tislelizumab, albumin-bound paclitaxel, and cisplatin for two cycles, followed by radical resection ~4 weeks after treatment completion. The primary endpoint, pCR rate, was achieved in 14 of 23 patients (60.9%; 23/28, 82.1% of the total cohort underwent surgery). Secondary endpoints included MPR rate (21.7%, 5/23), R0 resection rate (100%), and objective response rate (64.3%; 18/28). Treatment-related adverse events were manageable, with grade 3 or 4 treatment-related adverse events occurring in 10 (35.7%) patients. No surgical delays were observed. Single-cell RNA sequencing revealed remodeling of the HNSCC tumor microenvironment, which may correlate with improved clinical outcomes. This trial met the pre-specified primary endpoint, demonstrating a high pCR rate with promising efficacy and manageable toxicity in locally advanced HNSCC.

Subject terms: Head and neck cancer, Tumour immunology, Phase II trials, Cancer immunotherapy

Neoadjuvant cancer therapeutic strategy has been explored in phase I/II clinical studies for head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Here this group reports a single-arm, phase II clinical trial evaluating the neoadjuvant radiotherapy plus PD-1 inhibitor tislelizumab combined with paclitaxel and cisplatin, followed by radical surgical resection on 28 patients with untreated stage III-IVB head and neck squamous cell carcinoma.

Introduction

Locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) accounts for a significant proportion of HNSCC cases, with an estimated 70-80% of patients first diagnosed at this stage1. Unfortunately, despite standard treatment options, such as radical resection with adjuvant chemotherapy or radiochemotherapy, mortality rates continue to rise. Immunotherapy has emerged as a potential breakthrough in addressing this therapeutic impasse.

Programmed death receptor 1 (PD-1) antibody, a PD-1 inhibitor, is a key player in immunotherapy, given that Programmed cell death-Ligand 1 (PD-L1) is expressed in 50–60% of patients with HNSCC2. The Checkmate 141 and KEYNOTE-048 studies established the efficacy of PD-1 antibodies in recurrent metastatic HNSCC3,4. With the approval of PD-1 inhibitors as first-line therapy for recurrent/metastatic HNSCC based on the study of KEYNOTE-048, the application of immunotherapy in HNSCC has gained widespread acceptance. However, although immunotherapy can induce durable systemic responses, it is only effective in ~15% patients with HNSCC5.

HNSCC is a relatively immunodeficient tumor with an immunosuppressive microenvironment, including dysfunctional tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and enrichment of regulatory T cells and tumor-associated macrophages. These factors lead to immune evasion and a low response rate to immunotherapy, highlighting the need for combination therapies to improve efficacy6,7. Studies indicate synergistic antitumor effects when combining chemotherapeutic agents (paclitaxel, carboplatin, gemcitabine) with PD-1 inhibitors8. Moreover, the combination of PD-1 inhibitors and chemotherapy shows significant efficacy against various cancers with minimal overlapping adverse reactions9. Neoadjuvant treatment combining immunotherapy with docetaxel and cisplatin achieves a 48% pathological response rate in locally advanced HNSCC10. Our group previously performed a phase Ib clinical study exploring the safety and efficacy of combined immunotherapy with toripalimab, gemcitabine, and cisplatin chemotherapy as neoadjuvant treatment for locally advanced HNSCC11. The results showed that the major pathological response rate after surgery was 45%. Thus, these findings highlight the promising application of immunotherapy and chemotherapy combination in locally advanced HNSCC.

In recent years, the landscape of neoadjuvant immunotherapy for resectable locally advanced HNSCC has evolved significantly. In some phase 2 studies (NCT02296684 and NCT02641093) and KEYNOTE-689 (NCT03765918) neoadjuvant and adjuvant pembrolizumab demonstrated protential efficacy and acceptable safety in patients with resectable LA HNSCC12–14. Many studies have reported that neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy significantly improves the overall response and pathologic response. In some phase II trials for locally advanced HNSCC, the pathologic complete response rate reached about 17%-42%11,15,16, including a 30%-41.4%17,18 pathologic complete response rate in patients with locally advanced resectable OSCC. Nevertheless, there is still a lack of phase 3 randomized trial data of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy in HNSCC.

Low-dose radiotherapy (LDR) reprogrammed immune-desert tumors by inducing M1 macrophage polarization, chemokine production, and effector T cell recruitment19. LDR activates innate and adaptive immune responses, controlling tumor growth and reversing immune suppression. It enhances natural killer cell infiltration and reduces transforming growth factor-β levels20. Notably, LDR counters immunosuppressive tumor environments by manipulating tumor stromal cells and redirecting immune cells toward them19. Therefore, LDR effectively enhances the antitumor effects of immunotherapy.High-dose radiotherapy (HDR) primarily exerts its effect through direct tumor cytotoxicity, while also mediating important immunomodulatory effects such as activating dendritic cells, releasing danger signals, and upregulating cytokines, which promote immune responses and enhance T cell function21–24. In contrast, low-dose radiotherapy (LDR) can safely target the entire body system, reprogramming the tumor microenvironment (TME), inducing M1 macrophage polarization, and promoting T cell infiltration, while avoiding the high toxicity associated with HDR. LDR enhances immune therapy effectiveness by transiently inflaming tumors and mobilizing both innate and adaptive immune mechanisms20,25,26. Therefore, LDR and HDR each play unique roles in cancer treatment, with LDR providing a safer and longer lasting option for synergizing with immunotherapy.

Previous clinical studies have reported the outcomes of the combination of LDR and chemotherapy as a neoadjuvant treatment for patients with HNSCC27,28. A study found that two cycles neoadjuvant treatment with LDR (0.5 Gy twice a day on days 1, 2, 8, and 15) in combination with weekly paclitaxel plus every-3-week carboplatin achieved a complete response (CR) rate of 62.5% on imaging, with a median overall survival (OS) of 107.2 months29,30. This research provides valuable insights into the feasibility of using specific LDR regimes and doses in combination with chemotherapy for HNSCC.

In this work, we show that neoadjuvant low-dose radiotherapy (LDR) combined with tislelizumab, albumin-bound paclitaxel, and cisplatin achieves a high pCR rate in patients with resectable, locally advanced HNSCC. Our findings suggest that this combination therapy may improve clinical outcomes while maintaining a manageable safety profile.

Results

Patients

From April 29, 2022, to March 27, 2024, 37 patients were assessed for eligibility, and 28 patients were enrolled after signing an informed consent form and were thus included in the modified intention-to-treat (ITT) population. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics are shown in Table 1. The median age of the patients was 52.9 years, and the predominant location of the primary tumor site was the oral cavity (75.0%, 21/28). In addition, 14 (50.0%) patients had T4 tumors, and 21 (75.0%) patients presented lymph node metastasis. All patients were newly diagnosed with stage III-IVB HNSCC before enrollment, and the most frequent clinical stage was IVA (67.9%, 19/28), which is typical of previous studies11.

Table 1.

Patient characteristics

| Demographic variables | Patients (N = 28) |

Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 52.9 ± 9.7 | - |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 26 | 92.9 |

| Female | 2 | 7.1 |

| Smoker | ||

| Never | 11 | 39.3 |

| Current or former | 17 | 60.7 |

| Alcohol abuse | ||

| No | 17 | 60.7 |

| Yes | 11 | 39.3 |

| Tumor Site | ||

| Oropharynx | 4 | 14.3 |

| Larynx | 2 | 7.1 |

| Hypopharynx | 1 | 3.6 |

| Oral Cavity | 21 | 75.0 |

| T category | ||

| T1 | 0 | 0.0 |

| T2 | 3 | 10.7 |

| T3 | 11 | 39.3 |

| T4 | 14 | 50.0 |

| N category | ||

| N0 | 7 | 25.0 |

| N1 | 4 | 14.3 |

| N2 | 15 | 53.6 |

| N3 | 2 | 7.1 |

| PD-L1 (CPS) | ||

| CPS = 0 | 5 | 17.9 |

| 0 < CPS < 1 | 3 | 10.7 |

| 1 < CPS < 19 | 13 | 46.4 |

| CPS > 20 | 7 | 25 |

| HPV (p16) | ||

| Negative | 15 | 53.6 |

| Positive | 13 | 46.4 |

| AJCC stage (The eighth edition) | ||

| III | 6 | 21.4 |

| IVA | 19 | 67.9 |

| IVB | 3 | 10.7 |

Abbreviations: AJCC, American Joint Committee on Cancer.

Treatment characteristics

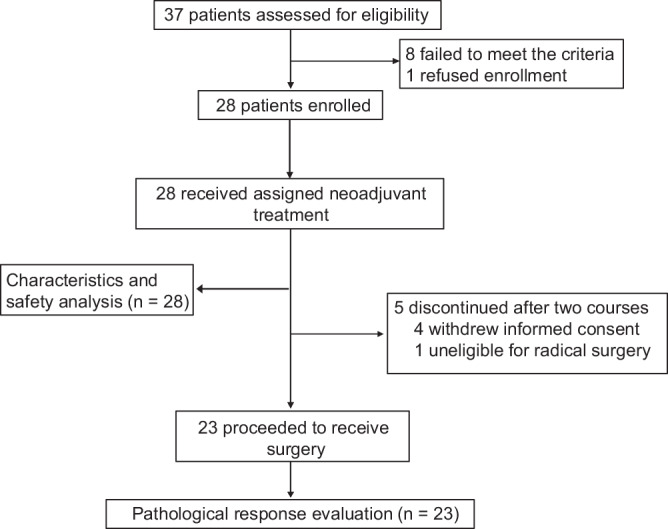

All 28 patients in the modified ITT population received two cycles neoadjuvant treatment, of whom 23 patients finally underwent surgery and achieved radical tumor resection. Five of 28 failed to undergo radical surgical resection: one declined further surgery or radical radiotherapy due to significant tumor regression and complete symptom remission, two resisted surgery and opted for radical radiotherapy, one was lost to follow-up after two cycles, and one was deemed ineligible for complete resection by the surgeon and proceeded with radical radiotherapy after Multi-Disciplinary Treatment (Fig. 1). The median time between the last neoadjuvant treatment and surgery was 38.3 days (95%CI, 33.7–42.9), and no surgery-associated morbidity or mortality was observed. No patients had surgical delays. Among the 23 patients who underwent radical resection, 18 received postoperative radiotherapy, 2 received postoperative chemoradiotherapy, and 3 were only monitored with follow-up without further antitumor treatment. All withdrawn participants received radical chemoradiotherapy to regress residual tumors following neoadjuvant treatment (Supplementary Fig. 1).

Fig. 1. Clinical trial flow chart.

In the study, 37 patients were assessed for eligibility, 28 patients were enrolled and included, and 23 patients underwent radical surgical resection.

Response and survival

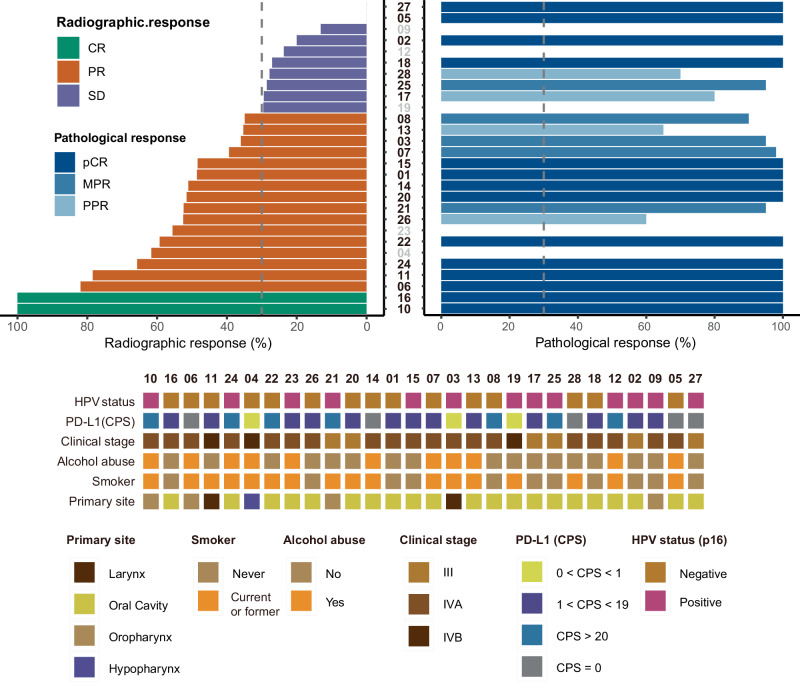

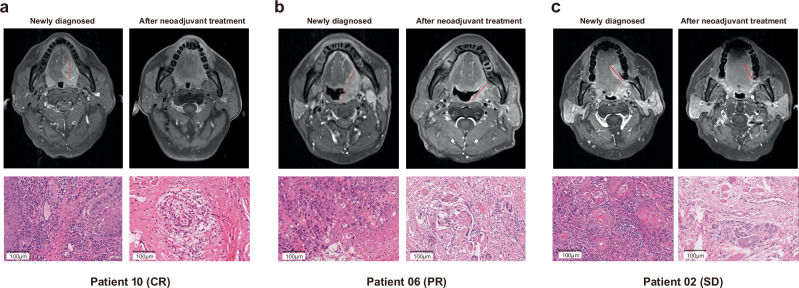

Among all patients receiving two cycles neoadjuvant treatment and MRI scan evaluation, 18 of 28 (64.3%) participants exhibited an ORR radiographically as per RECIST 1.1. Of these, two (7.1%) had a complete response (CR), and 16 (57.1%) had a partial response (PR). All the other patients presented stable disease. No progressive disease was observed during neoadjuvant therapy (Figs. 2 and 3). Patients who underwent radical surgery had an R0 resection rate of 100%. Of the 23 patients whose tumors were pathologically evaluable for the primary endpoint, 14 (60.9%) achieved pCR in the primary tumor and lymph node, five (21.7%) had MPR, and four (17.4%) had PPR, respectively. The pathological profiles of evaluable patients after surgical resection are summarized in Fig. 2. Additionally, pCR of pathological response was detected in four patients with SD of radiographic response. The radiographic response of SD was also detected as PPR or MPR of pathological response in some patients. Additionally, patients with an ORR did not have a correlation with a pathological response (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b). As shown by patients 02, 06 and 10, all the three participants had a pCR after evaluating the surgical resected tissue, while the radiographic responses were CR, PR and SD. Regardless of radiographic response, patients with pCR observed pathological features including interstitial fibrous tissue hyperplasia, infiltration of multinucleated giant cells, tissue cells and chronic inflammatory cells (including lymphocyte and plasma cells infiltration), and no residual tumor inside the tumor bed (Fig. 4a–c).

Fig. 2. Waterfall plot of characteristic of radiographic response (n = 28) and pathological response (n = 23) profiles.

Each column indicates one patient, ranking from highest to lowest rate of radiographic response. Corresponding sequence numbers of patients are labeled below. The dashed horizontal line denotes 30% radiographic response, indicating the cutoff points for PR and SD (Left). Each column indicates one patient. Two dashed horizontal lines denote 50% and 90% pathological response, indicating the cutoff points for NPR and PPR, PPR and MPR. Gray vertical axes represent patients who did not undergo surgery (Right). Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

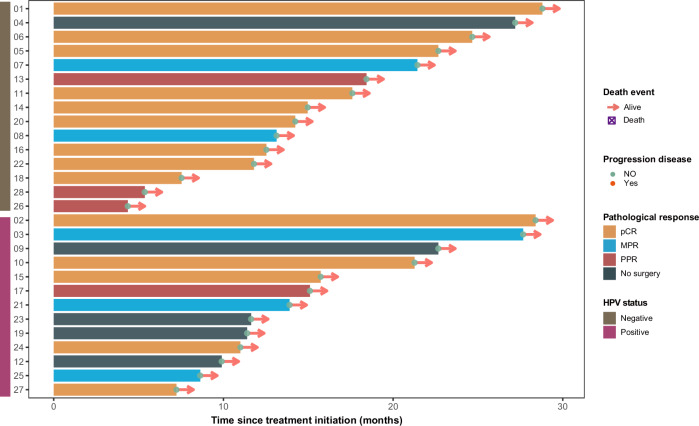

Fig. 3. Swimming plot of overall survival for individual patients (n = 28).

Each bar indicates one patient. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

Fig. 4. Magnetic resonance images (T1 enhanced sequence images) and H&E staining images (20×) of primary site tumor before and after two courses of neoadjuvant therapy.

a The number 10 patient with a pCR of pathological response and a CR of radiographic response. b The number 06 patient with a pCR of pathological response and a PR of radiographic response. c The number 02 patient with a pCR of pathological response and a SD of radiographic response. Scale bar = 100 μm. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

In the evaluable cohort of 23 patients, there were 9 HPV-positive (p16-positive) patients and 14 HPV-negative (p16-negative) patients. Among the 9 p16-positive patients, 5 (55.56%) achieved pCR, while 9 of the 14 p16-negative patients (64.29%) achieved pCR. In terms of MPR, 3 out of 9 p16-positive patients (33.33%) achieved MPR, while 2 out of 14 p16-negative patients (14.29%) achieved MPR. This suggests that while p16 status may influence some response types, the overall differences in pCR and MPR are relatively small. Interestingly, the PPR rate was higher in p16-negative patients (21.43%) compared to p16-positive patients (11.11%) (Table 2). Collectively, these findings demonstrate limited intergroup differences in pathological responses between p16-positive and p16-negative subgroups. The 3-year progression-free survival (PFS) rate and OS rate have not yet been fully elucidated. By September 2024, no case of non-progressive disease (NPR) had occurred. The median follow-up time from the first day of treatment is 14.1 months, ranging from 4.4 months to 28.8 months (Fig. 3). Data on the 1-year and 3-year OS and PFS rates will be presented in subsequent publications Table 3.

Table 2.

Treatment Response by p16 Status in the Evaluable Cohort

| HPV status (p16) | pCR (n,%) | MPR (n,%) | PPR (n,%) | Total patients (n) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | 5 (55.6%) | 3 (33.3%) | 1 (11.1%) | 9 |

| Negative | 9 (64.3%) | 2 (14.3%) | 3 (21.4%) | 14 |

Table 3.

Treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs) identified by investigators

| Grade 1 | Grade 2 | Grade 3 | Grade 4 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No | % | No | % | No | % | No | % | |

| All patients with an event | 27 | 96.4 | 18 | 64.2 | 10 | 35.7 | 2 | 7.1 |

| Anorexia | 9 | 32.1 | 2 | 7.1 | 1 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Nausea | 7 | 25.0 | 1 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Vomiting | 1 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Fatigue | 3 | 10.7 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Constipation | 1 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Diarrhea | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Rash | 2 | 7.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Dizziness | 1 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Alopecia | 6 | 21.4 | 9 | 32.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Oral mucositis | 0 | 0.0 | 1 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Dermatitis radiation | 1 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| White blood cell decreased | 5 | 17.9 | 5 | 17.9 | 5 | 17.9 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Neutropenia | 7 | 25.0 | 6 | 21.4 | 6 | 21.4 | 2 | 7.1 |

| Creatinine increased | 5 | 17.9 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Anemia | 14 | 50.0 | 2 | 7.1 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Alanine aminotransferase increased | 1 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Aspartate aminotransferase increased | 1 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Blood bilirubin increased | 1 | 3.6 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Hyperuricemia | 6 | 21.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

| Hyperglycemia | 6 | 21.4 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 | 0 | 0.0 |

Safety

A total of 28 patients who received a two-cycle neoadjuvant regime of LDR and tislelizumab combined with albumin-bound paclitaxel and cisplatin were included in the study population for safety analysis. Overall, 27 (96.4%) patients suffered from treatment-related adverse events (TRAEs), and 10 of 28 (35.7%) patients had grade 3-4 AEs. The most common grade 3 adverse events occurred in 10 cases, primarily involving neutropenia and decreased white blood cell count. The only grade 4 adverse event observed was neutropenia, which occurred in 2 patients. Consequently, the dose of cisplatin was adjusted, following the judgment of the investigators and subsequent approval from the medical ethics committees. Details of this adjustment have been provided in the protocol. The most common grade 1 or 2 AEs was anemia, which happened in 16 (57.1%) patients. In the grade 1 adverse events, those occurring at a frequency exceeding 20% included anorexia (9/28, 32.1%), nausea (7/28, 25.0%), alopecia (6/28 21.4%), hyperuricemia (6/28, 21.4%), and hyperglycemia (6/28, 21.4%). None of the AEs reported during the neoadjuvant treatment resulted in surgical delay, or death.

Biomarker analysis

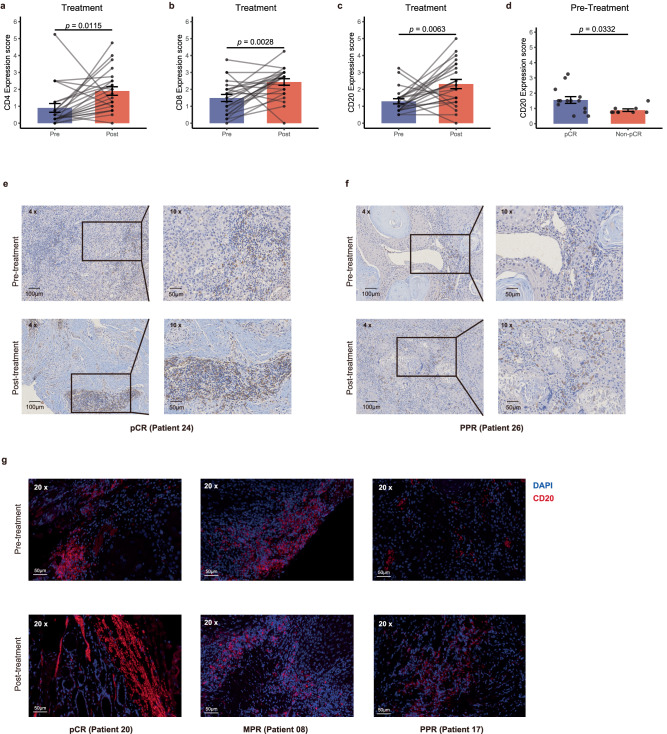

To explore the immunologic correlates of neoadjuvant treatment and pathological response, we performed immunohistochemistry and multiplex immunofluorescence on paired pretreatment biopsies and surgical resection specimens from the participants. We found that the expression of CD4 (p = 0.0115), CD8 (p = 0.0028) and CD20 (p = 0.0063) increased after the combination neoadjuvant treatment (Fig. 5a–c, e, f). And the immunohistochemistry results showed that the pretreatment levels of CD20 in patients with pCR was significantly higher than those with Non-pCR (MPR + PPR) (p = 0.0332) (Fig. 5d, f). And there was no significant difference in the pretreatment levels of CD4 and CD8 between pCR and non-pCR groups (Supplementary Fig. 3a, b). These results were also verified by detecting the expression of CD20 using multiplex immunofluorescence in three patients with pCR, MPR and PPR, respectively (Fig. 5g).

Fig. 5. Biomarker analyzes of treatment and pathological.

a–c Bar plots to show the expression of CD4, CD8 and CD20 in tissues before and after neoadjuvant treatment (n = 46). Statistical significance was determined using two-sided paired t-tests. d Bar plots showing the pretreatment levels of CD20 in tumor tissues (n = 23). Data are presented as mean values ± standard error of the mean (SEM). Error bars represent the SEM. Statistical significance was determined using a two-sided Wilcoxon rank-sum test. e, f The CD20 expression in tissues before and after treatment of patients with pCR and PPR. Scale bar, 100 μm and 50 μm. g This representative figure shows multiplex immunofluorescence (CD20 in red, DAPI in blue) demonstrating the spatial distribution across pathological response groups post-treatment: pCR (left), MPR (middle), and PPR (right) (Scale bar=50 μm). Top: Pre-treatment. Bottom: Post-treatment. Source data are provided as a Source Data file.

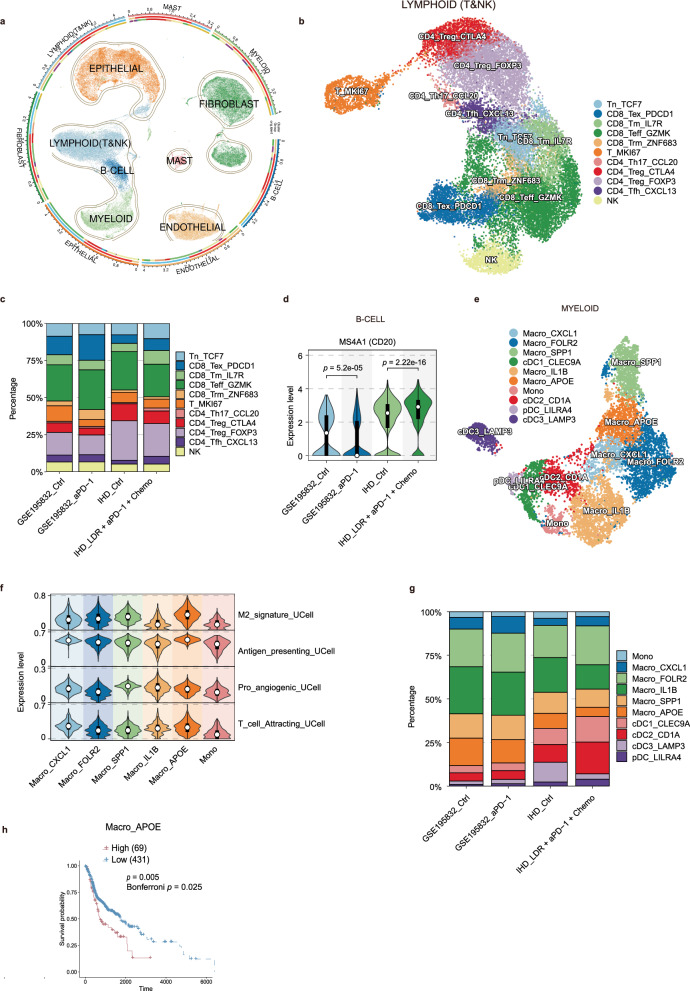

Single-cell RNA sequencing (scRNA-seq) reveals LDR combined with immunotherapy plus chemotherapy by activating adaptive immunity and modulating myeloid cell populations to remodel the HNSCC TME

To gain insights into the mechanisms by which LDR combined with immunotherapy and chemotherapy as a neoadjuvant treatment modulates the tumor microenvironment (TME) in HNSCC, we collected paired pre- and post-treatment biopsy tissues from three patients with advanced HNSCC who underwent treatment with LDR in combination with tislelizumab, albumin-bound paclitaxel, and cisplatin (a total of 6 samples). Subsequently, single-cell RNA sequencing was performed using the 10x Genomics platform. Additionally, we obtained data from 4 paired advanced HNSCC patients before and after nivolumab treatment from the single-cell RNA sequencing cohort GSE195832 (a total of 8 samples). After undergoing the quality control processes described in the Materials section, a total of 90,520 cells from 14 patient samples were selected for further analysis, including GSE195832_control (Ctrl) (4 samples), GSE195832_aPD-1 (4 samples), in-house dataset Ctrl (IHD_Ctrl) (3 samples), and IHD_LDR + aPD-1 + Chemo (3 samples) (Supplementary Fig. 4a, b).Harmony was then employed for batch correction and dimensionality reduction, followed by clustering analysis. Based on the expression of marker genes, the cells were annotated into seven distinct cell types, including epithelial cells (EPITHELIAL, highly expressing EPCAM, KRT19, PROM1, ALDH1A1, CD24), B lymphocytes (B-CELL, highly expressing CD19, MS4A1, CD79A), myeloid cells (MYELOID, highly expressing CD68, CD163, CD14), fibroblasts (FIBROBLAST, highly expressing FGF7, MME), endothelial cells (ENDOTHELIAL, highly expressing PECAM1, VWF), mast cells (MAST, highly expressing KIT) and T lymphocytes/NK cells (LYMPHOID & NK, highly expressing CD3D, CD3E, CD8A, CD8B, CD4 or highly expressing FGFBP2, FCG3RA, CX3CR1) (Fig. 6a, and Supplementary Fig. 4c–f).

Fig. 6. The immune cell landscape in HNSCC patients receiving neoadjuvant treatment with LDR combined with αPD-1 and chemotherapy.

a UMAP plot depicting all cells from HNSCC patients, with each cell type indicated by a different color. b UMAP plot showing the subpopulations of T lymphoid cells and NK cells from HNSCC patients, also color-coded by cell type. c Cell Type Infiltration Percentage Stacked Bar Chart shows the percentage distribution of CD8+ T cell subpopulations. d Violin plot that shows treatment group differences in MS4A1 expression within B cells. Violin plots depict the distribution of expression levels, with the top and bottom edges indicating the maximum and minimum values, respectively, white dots representing median values, and black bars showing the interquartile range (IQR, 25th to 75th percentiles). Statistical significance was determined using a two-sided Kruskal-Wallis test followed by Dunn’s post-hoc test (****p < 0.0001). e UMAP plot of myeloid cell subpopulations from HNSCC patients, color-coded by cell type. f Violin plot illustrating the functional characteristic scores across monocyte-macrophage subpopulations. Violin plots depict the distribution of expression levels, with top and bottom edges indicating the maximum (100th percentile) and minimum (0th percentile) values, respectively, white dots representing median values (50th percentile), and black bars showing the interquartile range (IQR, 25th to 75th percentiles). g Cell Type Infiltration Percentage Stacked Bar Chart shows the percentage distribution of myeloid cell subpopulations. h Kaplan-Meier curve that demonstrates the correlation between the infiltration of Macro_APOE and the overall survival (OS) of TCGA-HNSC patients (n = 500). Statistical significance was determined using a two-sided log-rank test, with Bonferroni correction (α = 0.05/5 = 0.01) for multiple comparisons.

Prior studies have demonstrated that LDR in combination with tislelizumab and chemotherapy, as a neoadjuvant treatment, can reprogram immunologically deserted tumors by modulating immune cells19. In our analysis, we focused on T cells, B cells, and myeloid cells to further elucidate the immunological shifts induced by this treatment regimen. Through subclustering of T and NK cells, we identified a total of 11 distinct cellular clusters (Fig. 6b, and Supplementary Fig. 5a–c). The comparison of cell infiltration revealed a significant increase in the proportion of CD8+IL7R+ effector memory T cells (CD8_Tm_IL7R) in the IHD_LDR + aPD-1 + Chemo group compared to the IHD_Ctrl group, while no similar change was observed between the GSE195832_aPD-1 and GSE195832_Ctrl groups, suggesting that LDR combination therapy may enhance anti-tumor immunity by increasing effector memory T-cell infiltration (Fig. 6c, and Supplementary Fig. 5d, e). Notably, we further analyzed the expression of the B-cell activation marker MS4A1 (CD20) across the four groups, finding that CD20 expression was significantly reduced in the GSE195832_aPD-1 group compared to the GSE195832_Ctrl group, whereas it was markedly elevated in the IHD_LDR + aPD-1 + Chemo group compared to the IHD_Ctrl group (Fig. 6d), aligning with previous immunohistochemistry and multiplex immunofluorescence results. A study on LUAD (lung adenocarcinoma) showed that 1 Gy of LDRT could enhance tertiary lymphoid structures (TLS) formation, and combining LDRT with anti-PD-1 therapy not only increased the number of TLS but also improved their maturity, significantly enhancing antitumor effects compared to single treatments31. This upregulation is consistent with previous findings that LDR co-administration can stimulate adaptive immune responses19. This refined analysis underscores the potential of LDR combined with immunotherapy and chemotherapy to reshape the tumor microenvironment by enhancing the activity and infiltration of specific immune cell populations, thereby potentially improving treatment outcomes in patients with advanced HNSCC.

Given the capacity of LDR to induce M1 macrophage polarization and reshape immunologically deserted tumors19, we conducted a subclustering analysis of myeloid cells, which yielded 10 distinct subpopulations (Fig. 6e, and Supplementary Fig. 6a–c). Utilizing the R package Ucell, we characterized the functional attributes of each subset based on macrophage-associated pathways and compared the infiltration patterns across groups. Our findings indicated that the APOE+ macrophages (Macro_APOE) subset, identified as M2 macrophages with the highest scores (Fig. 6f), is associated with immunosuppressive macrophages. Notably, the infiltration of APOE+ macrophages was significantly reduced in the IHD_LDR + aPD-1 + Chemo group compared to the IHD_Ctrl group (Fig. 6g, and Supplementary Fig. 6d, e). Subsequently, using this scRNA-seq cohort as a training set, we employed the deconvolution algorithm CIBERSORTx to estimate the infiltration abundance of macrophage clusters in the The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA)-Head and Neck Cancer (HNSC) cohort and calculated the relationship between their infiltration levels and prognosis. The results showed that high infiltration of APOE+ macrophages was associated with poor outcomes in HNSCC. Similarly, high infiltration of IL1B+ macrophages (Macro_IL1B), and SPP1+ macrophages (Macro_SPP1) was also associated with poor prognosis in HNSCC, whereas high infiltration of FOLR2+ macrophages (Macro_FOLR2) was linked to favorable prognosis. In contrast, high infiltration of monocytes (Mono) showed no statistically significant association with prognosis. CXCL1+ macrophages (Macro_CXCL1) were minimally infiltrated or absent in the majority of TCGA-HNSC patients (Fig. 6h, Supplementary Fig. 6f). Mechanistically, previous studies have suggested that APOE+ macrophages are a key factor in the failure of immune checkpoint inhibitor (ICI) treatment in patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC)32. SPP1 has been extensively reported to promote tumor progression and immune therapy resistance across various cancers. Additionally, in the pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma (PDAC) microenvironment, a conserved IL-1β+ TAM subpopulation is enriched in inflammatory response and immune suppression genes33. Studies have suggested that interactions between FOLR2+ tissue-resident macrophages and CD8+ T cells contribute to a better prognosis in breast cancer34.

In the IHD_LDR + aPD-1 + Chemo group, we observed a significant increase in the infiltration of DC cells, particularly the CD1A+ cDC2 cells (cDC2_CD1A), compared to the IHD_Ctrl group (Fig. 6g, and Supplementary Fig. 6d, e). Recent studies suggest that LDR enhances PD-L1 blockade efficacy by remodeling dendritic cells within the myeloid compartment35. These findings suggest that LDR combination therapy may reshape the TME and enhance anti-tumor immunity by reducing immunosuppressive macrophages and increasing dendritic cell infiltration. These findings further highlight the crucial role of myeloid cells in the tumor microenvironment, and LDR may improve immune responses by modulating the composition of myeloid cell remodeling, offering strategies for immunotherapy.

In summary, our findings suggest that the combination of LDR with tislelizumab and chemotherapy as a neoadjuvant treatment reshapes the tumor microenvironment in HNSCC by enhancing adaptive immune responses and modulating myeloid cell populations. Specifically, this regimen increases the infiltration of CD8+IL7R+ memory T cells. Additionally, the treatment may suppresses the infiltration of immunosuppressive APOE+ macrophages while promoting the infiltration of the CD1A+ cDC2 cells, which may enhance anti-tumor immunity. These changes highlight the potential of LDR combined with immunotherapy and chemotherapy to optimize the tumor microenvironment and improve treatment outcomes in HNSCC patients.

Discussion

This study evaluates the application of LDR combined with tislelizumab, albumin-bound paclitaxel, and cisplatin as a neoadjuvant therapeutic strategy in patients with resectable, locally advanced HNSCC, which could provide new insights into optimizing treatment approaches for this population. pCR and MPR are well-established predictors of improved survival36. Therefore, pCR was selected as the primary endpoint. In our study, the primary endpoint of pCR was achieved at a rate of 60.9% (14/23), and 21.7% (5/23) of patients had a major pathological response, indicating that more than 80% of patients markedly benefited from neoadjuvant therapy with LDR and immunochemotherapy. The addition of LDR to neoadjuvant immunochemotherapy resulted in a well-tolerated safety profile, no perioperative mortality, and no delay in planned surgery. Grade 3-4 TRAEs were observed in 35.7% (10/28) of the patients after the study treatment, which was manageable.

In recent years, significant progress has been made in neoadjuvant immunotherapy for resectable locally advanced HNSCC. Several phase II-III clinical trials, including NCT02296684, NCT02641093, and KEYNOTE-68912–14, have demonstrated promising efficacy and safety for pembrolizumab as both neoadjuvant and adjuvant treatment, with pCR rates ranging from 17% to 42%11,15,16, and 30%–41.4%17,18 in patients with resectable oral squamous cell carcinoma (OSCC). Although the survival benefits of neoadjuvant chemotherapy in locally advanced head and neck tumors remain inconclusive, this treatment approach still shows significant potential, particularly in organ preservation and treatment deintensification. The pCR rate after conventional chemotherapy regimens (such as docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil) is 13.4%37, while adding checkpoint inhibitors increases the pCR rate to 16.7%–37.0%11,16, highlighting the potential of neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy in locally advanced HNSCC. Another trial using three cycles of camrelizumab, nab-paclitaxel, and cisplatin achieved a pCR rate of 55.6% and a pCR/MPR rate of 63.0%, which is higher than historical data38. However, our study surpassed these previous results, with a pCR rate exceeding 60% and a pCR/MPR rate exceeding 80%. Notably, our study employed only two cycles of neoadjuvant therapy, fewer than the three cycles used in the aforementioned trial. This demonstrates that the combination of LDR with immunochemotherapy offers a more effective, innovative, and promising approach for neoadjuvant treatments.

HPV infection has been established as a significant carcinogenic factor in HNSCC, with infected patients typically demonstrating improved survival outcomes. Nevertheless, the extent to which HPV status influences the efficacy of immunotherapy remains a subject of ongoing investigation. The KEYNOTE-012 trial revealed a differential response, with HPV-positive patients exhibiting a 24% ORR compared to 16% in HPV-negative cases among recurrent or metastatic HNSCC patients. However, subsequent large-scale studies (KEYNOTE-040, KEYNOTE-04) demonstrated comparable ORR rates across HPV statuses, with no statistically significant differences in median PFS or OS.Recent clinical investigations have provided new insights into this area. A notable study presented at the 2024 ASCO Annual Meeting evaluated 27 patients with HPV-positive oropharyngeal squamous cell carcinoma who underwent neoadjuvant treatment with sintilimab combined with platinum-based doublet chemotherapy. This regimen yielded remarkable outcomes, with a MPR rate of 96.0% (24/27 patients) and a pCR rate of 52.0% (13/27 patients). Complementary findings were reported in Nature Communications, documenting a pCR rate of 55.6% following neoadjuvant immunochemotherapy, though only one-third of the cohort comprised HPV-positive oral cancer cases. In our clinical cohort, the differences in pCR and MPR between p16-positive and p16-negative patients were not significant. These differences may be influenced by the limited sample size and possibly by the enhancing effect of LDR on pathological responses in p16-negative patients. Although p16 status may have some impact on pathological response, the overall differences between p16-positive and p16-negative patients are not substantial. This clinical evidence highlights the need for further research to elucidate the complex interplay between HPV status and treatment outcomes in HNSCC.

Imaging is a standard method for evaluating therapeutic response38. The correlation between pathological remission and radiographic response following neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy, as well as their prognostic value, remains unclear. Some previous results showed a significant correlation between radiographic response and pathological response17,38, while other studies have reported opposing results11,39. However, in our study, the correlation between pathological and radiographic responses was not consistent. Among 23 patients, 60.9% (14/23) achieved pCR, but only 8.7% (2/23) had a radiographically complete response (CR). Additionally, four patients showed stable disease on imaging but achieved pCR in pathological assessment after surgery. Several factors may contribute to the observed discrepancies between radiographic and pathological responses. First, the interval between imaging assessment and surgical resection may allow for tumor progression or regression. Second, current imaging modalities have inherent limitations in detecting microscopic residual disease, potentially leading to an overestimation of complete response. Third, the heterogeneous nature of tumor response to neoadjuvant therapy may result in sampling errors during pathological evaluation. Our study demonstrated that radiographic response did not correlate with pathological response, confirming that pathological response is the gold standard for neoadjuvant therapy40. Interestingly, we observed discordance between the pathological response of metastatic lymph nodes and primary sites, similar to a previous study11. In two patients, positive lymph nodes showed pCR or partial pathological response (PPR) in the primary site, suggesting different mechanisms of cancer development and treatment resistance.

LDR enhances immunotherapy by driving T-cell inflammation19. Two cycles of LDR combined with chemotherapy achieved a 28% radiographic CR in locally advanced HNSCC27. Subsequent phase II trial validated the safety and efficacy of LDR plus chemotherapy29. However, the pathological response is adopted as a surrogate endpoint for neoadjuvant therapy trials rather than a radiographic response. Here, the radiographic CR rate may have been lower than the above results; however, we obtained a higher pCR rate of 60.9%. Presently, high-dose radiation has also been added to neoadjuvant therapy30,41–43. However, adjuvant radiotherapy is usually required after surgery in patients with locally advanced HNSCC, and the high-dose radiation in neoadjuvant therapy restricts adjuvant treatment strategies. Furthermore, LDR has no limitations of postsurgical adjuvant radiotherapy and is more applicable and promising than high-dose radiation in neoadjuvant therapy.

Additionally, our study showed that the immune biomarker of CD4, CD8 and CD20 increased after neoadjuvant LDR plus immunochemotherapy. That confirms that the study regime can activate immune infiltration in the tumor bed, which is consistent with previous reports14,38,44–46. Further examination found that the higher pretreatment levels of CD20 correlated with pathological response of pCR. Moreover, existing studies have shown that LDR enhances tumor sensitivity to immunotherapy by inducing M1 macrophage polarization and recruiting stem cell-like CD8+ Tpex cells through the CXCL10/CXCR3 axis44. In contrast, our own single-cell RNA sequencing analysis of head and neck cancer patients suggests that the combination of low-dose radiotherapy (LDR) with immunochemotherapy may stimulate adaptive immune responses and could increase the infiltration of CD8+IL7R+ memory T cells. Furthermore, this treatment regimen appears to suppress the infiltration of immunosuppressive APOE+ macrophages while potentially promoting the infiltration of the CD1A+ cDC2 cells, which might contribute to enhanced anti-tumor immunity. These observations may provide insights into the possible mechanisms by which LDR could augment the efficacy of immunochemotherapy. Therefore, LDR significantly enhances the antitumor effects of immunotherapy.

Although TRAEs occurred in all patients, the rate of grade 3-4 TRAEs was 35.7%, which was somewhat higher than that reported in previous clinical trials of neoadjuvant chemotherapy and immunochemotherapy for HNSCC11,16,37. Most grade 3-4 TRAEs were neutropenia and decreased white blood cell count, likely due to weekly chemotherapy without granulocyte colony-stimulating factor. These results show the manageable safety of LDR with chemoimmunotherapy in locally advanced HNSCC.

Although the primary endpoint results were striking, there are some limitations. First, the sample size of the present trial was small, which limits our ability to explore the potential impact of other covariates. Second, we lacked an analysis of dynamic changes in biomarkers and treatment efficacy, which we will demonstrate in a future publication. Third, the translation from short-term to long-term survival remains unclear. Finally, the single-cell sequencing results lack validation through basic experimental approaches, requiring further investigation.

In conclusion, the results of our study suggest that neoadjuvant LDR with tislelizumab combined with albumin-bound paclitaxel and cisplatin in resectable locally advanced HNSCC has an encouraging pathological response and a manageable safety profile. Despite the aforementioned limitations, we still consider the findings representative of patients with locally advanced HNSCC and provide a promising strategy for neoadjuvant therapy. We have also registered and started a phase II clinical trial to evaluate the safety and efficacy of LDR combined with cadonilimab (both anti-PD-1 and anti-CTLA-4) plus chemotherapy as a neoadjuvant treatment for resectable, locally advanced HNSCC (Chinese Clinical Trial Registry, ChiCTR2400084430). In the future, a randomized phase III trial to verify the utility, safety, and overall survival benefits of the trial regimen is warranted.

Methods

Study design and participants

This study (NeoRTPC02, ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT05343325) was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Tenth Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University (Dongguan People’s Hospital, Dongguan, China) and the Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University (Zhuhai, China). All procedures involving human participants complied with relevant ethical regulations, including the Declaration of Helsinki and International Conference on Harmonization Guidelines on Good Clinical Practice (ICH-GCP). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants (n = 28) prior to enrollment (April 29, 2022, to March 27, 2024), including consent for the publication of deidentified medical data. The last patient was enrolled on March 27, 2024. The study design and conduct were authorized by the aforementioned ethics committees, ensuring compliance with regulations governing human research participants. No monetary compensation was provided, but all study drugs were supplied free of charge to participants.

This investigator-initiated, multicenter, open-label, single-arm, phase 2 clinical trial of LDR, tislelizumab, combined with albumin-bound paclitaxel and cisplatin in resectable locally advanced HNSCC was performed at two sites in China: the Tenth Affiliated Hospital of Southern Medical University and the Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-Sen University.

Eligible patients were 18–70 years of age with untreated and clinical stage III-IVB (T3-4N0M0 or T1-4N1-3M0, as defined by the American Joint Committee on Cancer, eighth edition) HNSCC. Demographic data including gender (self-reported per patient) was collected, though was not considered in trial design and study treatment. The resectability of all tumors was demonstrated by experienced surgeons and oncologists at a multidisciplinary conference. Other inclusion criteria included at least one measurable disease per RECIST version 1.1, Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of 0–1, and adequate marrow and organ function. Patients were excluded if they had allergies to any study drug, active autoimmune disease, another malignancy within the previous 5 years, or were pregnant or nursing women. Full inclusion and exclusion criteria were applied for the study.

Procedures

Patients were administered two 21-day cycles of treatment prior to surgical resection, including low-dose radiotherapy (LDR), tislelizumab, albumin-bound paclitaxel, and cisplatin. Radiotherapy was delivered at 1 Gy per fraction on days 1, 2, 8, and 15 of each cycle using intensity-modulated radiotherapy (IMRT) with a simultaneous integrated boost technique, with a prescribed dose of 8 Gy to the planning target volume (PTV) in 8 fractions. The PTV was defined as the gross tumor volume (GTV) plus a 3-mm margin, with the GTV encompassing the primary tumor and metastatic lymph nodes determined by clinical examination, MRI, and PET-CT. The maximum dose to the spinal cord planning organ-at-risk volume (PRV) was limited to 300 cGy, with doses to other organs at risk kept as low as possible. Tislelizumab (200 mg, day 1, Q3W), albumin-bound paclitaxel (100 mg/m2, days 1, 8, and 15, Q3W), and cisplatin (25 mg/m2, days 1, 8, and 15, Q3W)were administered as scheduled. Notably, the originally planned dose of cisplatin was 30 mg/m2 per time, and due to the adverse hematologic events of the first two participants (who had grade 3-4 hematologic events), the final dose was changed to 25 mg /m2 in every chemotherapy treatment in the modified protocol, which the Medical Ethics Committee approved.

All patients underwent pretreatment biopsy, enhanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the head and neck, positron emission tomography-computed tomography (or enhanced computed tomography and emission computed tomography), and other laboratory blood tests at staging and assessing eligibility. After two cycles neoadjuvant treatment, ~20 days later, MRI and physical examination were scheduled by radiologists and experienced surgeons to evaluate the tumor response and feasibility of surgery. All patients underwent planned radical surgical resection ~4 weeks after the last day of chemotherapy (day 15) of the second cycle of treatment. Subsequently, postsurgical MRI and excisional biopsy were conducted to evaluate the radiographic and pathological responses. Postoperative adjuvant treatment, while permitted, was not mandatory and was recommended by a multidisciplinary team based on the subjects’ condition, including clinical stage, radiographic and pathological responses, surgical resection margins, and lymph node pathological positivity rate.

All patients underwent physical examinations and laboratory tests before each treatment, and adverse events (AEs) were assessed in accordance with the National Cancer Institute’s Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0. AEs were monitored within 30 days after surgical resection or 90 days after the first dose of tislelizumab. Patients were scheduled to delay or interrupt treatment if they had a severe AE (grade 3–4), and treatment was resumed when the criteria for treatment resumption were met. The dose of tislelizumab could not be reduced.

Pathological response was assessed by at least two expert pathologists, evaluating the percentage of residual viable tumor (RVT) in the primary tumor after surgical resection for each patient. The pathological response is defined and graded based on the percentage of RVT in the resected tumor bed. All specimens were sectioned parallel every 5-10 mm, carefully examined for lesions on each section, and the three-dimensional dimensions of the residual tumor or fibrous tumor bed were measured. Lesions were sampled according to the principle of taking one block per 1 cm. Both the resected primary tumors and lymph nodes underwent routine hematoxylin-eosin (H&E) staining to estimate the RVT percentage in each sample, followed by histopathological examination. Based on the RVT percentage, the pathological response was classified into four grades: pathological complete response (pCR), where RVT in the primary tumor bed and draining lymph nodes is 0%; major pathological response (MPR), where RVT in the primary tumor bed is ≤10%; partial pathological response (PPR), where RVT in the primary tumor bed is > 10% and ≤50%; no pathological response (NPR), where RVT in the primary tumor bed is > 50%. In cases where residual viable tumor could not be identified under the microscope, especially when the tumor size was ≤3 cm, pathologists would sample the entire tumor bed and submit it for re-examination.

Outcomes

The primary endpoint was pCR, which was defined as the absence of residual viable tumors in the resected tumor tissue, including primary site and lymph node. The secondary endpoints were MPR, objective response rate (ORR; assessed per RECIST version 1.1), and R0 resection rate. The safety endpoints were AEs, no surgical delay. The toxicity profile was assessed between 30 and 90 days following surgical cresection and the initial dose of tislelizumab. Surgical delay was defined as the date of surgical resection because TRAEs exceeded the scheduled date by more than 4 weeks. The exploratory endpoints were the 3-year progression-free survival (defined as the time from the first dose of neoadjuvant treatment until disease progression, recurrence, death, or last day of follow-up) and 3-year overall survival (defined as the time from the first dose of neoadjuvant treatment until death or last day of follow-up), which were not possible because of insufficient follow-up time. Data on survival have not matured sufficiently and will be published later.

Immunohistochemistry and multiplex immunofluorescence

The expression of CD4, CD8, and CD20 was assessed via immunohistochemistry (IHC) on paraffin-embedded tumor tissue sections collected before neoadjuvant therapy and after surgical resection. Tissue sections were baked at 65 °C for 2–4 h, deparaffinized using eco-friendly deparaffinization solutions (I and II, 20 min each), and rehydrated through a graded ethanol series (100%, 95%, 90%, 80%, and 75%, 3 min each), followed by PBS rinsing. Antigen retrieval was performed by microwave heating in citrate buffer (pH 6.0) or Tris-EDTA buffer (pH 9.0) at high power for 15 min, with subsequent natural cooling to room temperature. Endogenous peroxidase activity was blocked with 3% H2O2 for 10 min, and nonspecific binding sites were blocked with 5% bovine serum albumin (BSA; Beyotime QuickBlock) for 1 h. Primary antibodies targeting CD4 (Proteintech, Cat# 67786-1, 1:1000), CD8 (Proteintech, Cat# 66868-1, 1:10,000), and CD20 (Proteintech, Cat# 60271-1, 1:10,000) were diluted and incubated overnight at 4 °C. After warming to room temperature, sections were incubated with HRP-conjugated secondary antibodies (1:500 dilution) for 1 h, followed by nuclear counterstaining with DAPI for 5 min. Chromogenic detection was achieved using DAB solution (KFBIO; A:B = 19:1), with reaction termination via PBS upon optimal signal development under microscopic monitoring. Sections were counterstained with hematoxylin for 5-10 min, rinsed under running water, dehydrated through a graded ethanol series, cleared in xylene, and mounted with neutral resin. Scanning of the slices was done using a Kscanner (KFBIO, Ningbo Kongfong Biotech International). CD4, CD8, and CD20 levels were quantified based on positive cell intensity (0-3) and area (0-4)47,48. Staining intensity was graded as follows: 0 (negative), 1 (weak), 2 (moderate), and 3 (strong). Cells were scored according to staining percentage: 0 (0% staining), 1 (1%-24% staining), 2 (25%-49% staining), 3 (50%-74% staining), and 4 (75%-100% staining). Four pathologists evaluated immunoreactive scores of four representative regions of interest (ROIs) under 200× magnification. ROI scores were calculated using the formula: ∑(intensity grade × corresponding area).

Multiplex immunofluorescence was performed by Shanghai KR Pharmtech, Inc., Ltd. (Shanghai, China) using the same experimental steps. After staining CD20 protein, whole slide scans at 20× magnification were conducted with the KR-HT5 system (KR Pharmtech, Inc.) and analyzed using inForm 2.4.0 software.

Single-cell transcriptomic data acquisition

Raw sequencing data for the HNSCC single-cell cohorts (GSE195832) were retrieved from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database, a repository supported by the National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI).

Additionally, human tissue samples were procured from three HNSCC patients at Dongguan People’s Hospital and the Fifth Affiliated Hospital of Sun Yat-sen University, with single-cell RNA sequencing performed in collaboration with Shanghai Personal Biotechnology (Shanghai, China). Tissues were processed in a sterile RNase-free environment using calcium-free and magnesium-free 1× PBS on ice. The tissue was minced into 0.5 mm² pieces and washed with 1× PBS to remove non-target tissues such as blood and fat. Subsequently, the tissue was dissociated into single cells using a dissociation solution containing 0.35% collagenase IV, 2 mg/ml papain, and 120 Units/ml DNase I at 37 °C with shaking at 100 rpm for 20 minutes. The enzymatic digestion was halted by adding 1× PBS supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS), followed by gentle pipetting using a Pasteur pipette 5–10 times.

The resulting cell suspension was filtered through a 70–30 µm stacked cell strainer and centrifuged at 300 g for 5 minutes at 4 °C. The cell pellet was resuspended in 100 µl of 1× PBS containing 0.04% BSA and treated with 1 ml of red blood cell lysis buffer (MACS 130-094-183, 10×) for 2–10 minutes at room temperature or on ice to lyse residual red blood cells. After centrifugation at 300 g for 5 minutes at room temperature, the suspension was resuspended in 100 µl of Dead Cell Removal MicroBeads (MACS 130-090-101) and passed through the Miltenyi Dead Cell Removal Kit to eliminate dead cells. This step was repeated twice, with the cell pellet resuspended in 1× PBS containing 0.04% BSA and centrifuged at 300 g for 3 minutes at 4 °C.

Cell viability was assessed using the trypan blue exclusion method, ensuring that the viability was above 85%. The single-cell suspension was counted using a hemocytometer or Countess II Automated Cell Counter, and the concentration was adjusted to 700–1200 cells/µl.

For single-cell sequencing, 5000 single cells were captured using the 10X Genomics Chromium Single-Cell 3’ kit (V3) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. cDNA amplification and library construction were performed following the standard protocol. Libraries were sequenced on an Illumina NovaSeq 6000 sequencing system with a paired-end multiplexing run of 150 bp, conducted by LC-Bio Technology Co., Ltd. (Hangzhou, China), ensuring a minimum sequencing depth of 20,000 reads per cell.

Acquisition of bulk transcriptomic data

We acquired transcriptomic expression values, patient clinical information, and survival data for Head and Neck Cancer (HNSC) from The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) project. These data were sourced from the UCSC Xena database, a rich repository for cancer genomics data. The mRNA expression values we downloaded were presented in Transcripts Per Kilobase Million (TPM), a normalized measure that takes into account gene length and sequencing depth. All subsequent analyzes were performed using R, version 4.3.1, to ensure the computational biology workflows were both robust and reproducible.

Initial processing and quality control of single-cell RNA-Seq (scRNA-seq) datasets

Raw sequencing data were processed using CellRanger version 4.0.0, a software suite developed by 10x Genomics. This step encompassed alignment, quantification, basic filtering, and quality control to generate preliminary gene expression matrices based on the human reference genome GRCh3849. Subsequent quality control and analysis were conducted using the R package Seurat version 4.4.0. High-quality cells were selected by applying the following filters: (i) cells expressing between 500 and 6000 genes, (ii) cells with mitochondrial gene UMI counts constituting less than 20% of the total UMI counts, and (iii) genes detected in at least three cells. (iv) a filter with an UMI threshold greater than 500. We also used the R package DoubletFinder to remove doublets. Following these quality control measures, a total of 90520 high-quality cells were identified and advanced to further analysis.

Downstream analysis of single-cell RNA-seq datasets

The analysis began with the normalization of gene expression counts using the NormalizeData function. To identify the most biologically significant genes, the FindVariableFeatures function was employed, selecting the top 2000 most variable genes across the cells. This selection is essential for capturing the heterogeneity within the dataset.

We then performed principal component analysis (PCA) following gene expression normalization with the ScaleData function. PCA is a dimensionality reduction technique that simplifies the data while retaining the maximum variance, facilitating the visualization of complex, high-dimensional data.

To address batch effects and ensure that biological signals were not obscured by technical variations, we applied the Harmony algorithm across samples. Harmony is a powerful tool for harmonizing multi-batch single-cell RNA sequencing data by aligning the expression profiles of cells from different batches.

Clustering was conducted at a resolution of 0.6, a parameter chosen to balance the trade-off between granularity and biological relevance. The resulting cell clusters were visualized using Uniform Manifold Approximation and Projection (UMAP), a technique that captures both global and local data structures in a lower-dimensional space.

Finally, cell-type annotation was performed by mapping the cells to known cell-type specific marker genes, categorizing them into eight distinct cell types: epithelial cells, B cells, macrophages, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, T cells, and NK cells. This annotation step is crucial for providing biological context to the unsupervised clustering results.

CIBERSORTx deconvolution analysis of immune cell infiltration

To computationally evaluate the immune cell infiltration within the TME of the TCGA-HNSC cohort, which corresponds to our single-cell RNA-seq data on head and neck cancer immunotherapy responses, we employed the online tool CIBERSORTx50. Utilizing a reference signature matrix derived from our single-cell RNA-seq dataset, we inferred the relative proportions of various immune cell types within the TCGA-HNSC cohort.

To determine the correlation between immune cell infiltration and patient survival time in the TCGA-HNSC cohort, we performed Kaplan-Meier survival analysis to assess survival differences between groups. Patients were categorized into high and low infiltration groups based on the optimal cut-off points for immune infiltration levels, which were calculated using the surv_cutpoint function from the R survminer package. The cut-off points were derived from the estimates obtained from CIBERSORTx (optimal cut-off point: Macro_IL1B: 0.01769533, Macro_APOE: 0.22886989, Mono: 0.61644567, Macro_SPP1: 0.15839030, Macro_FOLR2: 0.08724371). The log-rank test was then used to compare the survival curves between the high and low infiltration groups, and p-values were calculated to evaluate whether immune cell infiltration levels were significantly associated with patient survival outcomes.

Statistical analysis

The NeoRTPC02 trial is a phase II study evaluating the efficacy of LDR (tislelizumab with albumin-bound paclitaxel and cisplatin) to achieve pCR in newly diagnosed locally advanced HNSCC patients using Simon’s two-stage minimax design. A previous study reported a 13.4% pCR rate with neoadjuvant docetaxel, cisplatin, and 5-FU. The null hypothesis for neoadjuvant albumin-bound paclitaxel and cisplatin was a 10% pCR rate. A clinically relevant pCR rate of 35% was assumed for neoadjuvant LDR, tislelizumab, albumin-bound paclitaxel, and cisplatin. With a one-sided α of 5%, 80% power, and 10% dropout rate, 25 participants were planned. The first stage enrolled 10 patients, and the second stage proceeded if at least 1 achieved pCR. A promising outcome was defined as more than 5 patients achieving pCR. Of 37 patients assessed for eligibility, 9 were excluded (8 failed to meet inclusion criteria; 1 refused enrollment), and 28 were included in the modified intention-to-treat population. Among these, 5 did not undergo surgery: 2 achieved PR on imaging, with 1 declining further intervention due to significant tumor regression and symptom remission, and 1 opting for radical radiotherapy; 3 had SD, with 1 refusing surgery and choosing radiotherapy, 1 lost to follow-up after two cycles, and 1 deemed unsuitable for complete resection upon surgical reevaluation, proceeding to radiotherapy. This single-arm, open-label study did not use randomization or blinding.

Point estimates and 95% confidence intervals for pCR, MPR, ORR, and R0 resection rates were descriptively estimated using the Clopper-Pearson method. AE and nonsurgical delay rates were summarized by frequency counts and percentages. Paired t-tests analyzed pathologically immunoreactive scores, while McNemar’s test examined the correlation between ORR and pathological response.

For the comparison of MS4A1 expression across different treatment groups, we first performed the Kruskal-Wallis test to assess overall differences. For post-hoc pairwise comparisons, Dunn’s Test was used, and Bonferroni correction was applied to adjust for multiple comparisons.

For CIBERSORTx-derived immune cell infiltration in the TCGA-HNSC cohort, Kaplan-Meier survival analysis assessed the association between subtype infiltration levels (e.g., Macro_APOE, Macro_IL1B, Mono) and overall survival. Patients were divided into high and low infiltration groups using optimal cut-off points (surv_cutpoint, R package survminer). Two-sided log-rank tests compared survival curves, with Bonferroni correction (α = 0.05/5 = 0.01) applied to adjust for multiple comparisons across subtypes.

Statistical analyzes utilized PASS 15.0, SPSS 25.0, and R 4.3.1 with relevant software packages.

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Supplementary information

Description of Addtional Supplementary Files

Source data

Acknowledgements

We thank all the participants and their families for supporting these studies. We also thank all other investigators and the investigational site members involved in the study, as well as BeiGene (Beijing) Co., Ltd., which provided tislelizumab. The study was supported by Beijing Xisike Clinical Oncology Research Foundation (Grant Y-Young2022—0225). Role of Sponsorship The study sponsors, represented by their respective representatives, played a role in the design of the study, the collection, analysis, and interpretation of the data, as well as the writing of the report. The corresponding author had complete access to all the data in the study and held the final responsibility for the decision to submit the report for publication. The study was supported by Beijing Xisike Clinical Oncology Research Foundation (Grant Y-Young2022—0225, Z.L.1). Meeting Presentation: This study was presented in part of the ASCO 2023 Meeting as a poster (#6078) and the CSTRO 2023 Meeting in the mini oral session.

Author contributions

Zhigang Liu (Z.L.1) conceived the study and had full access to all data of the study. Z.L.1, D.W., G.L., M.Y.and Z.Z. contributed equally to this work. G.L., Z.Z., and G.Z. were responsible for the analysis and interpretation of data. D.W., Jianpeng Li (J.L.1), M.Y., L.X., R.J., Y.Z., L.H., Y.P., X.L., Jun Lai (J.L.2), Y.X., L.L., Z.W., Zhutian Liu (Z.L.2), Q.Y., and X.H. contributed to data acquisition. G.L. and Z.L. 1 were responsible for drafting the article. Y.L., Q.L., L.N., Jiao Lei (J.L.3), Zhijie Liu (Z.L.3), and W.J. contributed to critical revisions of the manuscript. All authors read and contributed to the final version of the manuscript and approved its submission for publication.

Peer review

Peer review information

Nature Communications thanks the anonymous reviewer(s) for their contribution to the peer review of this work. A peer review file is available.

Data availability

Due to confidentiality agreements, patient-related information cannot be disclosed. The study protocol and statistical analysis plan will be made available as a supplementary note in the supplementary information file. Qualified researchers who wish to access deidentified participant data must submit a proposal to the corresponding author, outlining the reasons for their application. The leading clinical site and sponsor will review the applications to determine their compliance with the confidentiality agreements and will respond within 8 weeks. A data access agreement with the sponsor is required before sharing any data. The single-cell RNA-seq raw data generated in this study have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive for Human (GSA-Human) database under accession code HRA010554 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/submit/hra/subHRA015433/finishedOverview). These data are available under restricted access to protect participant confidentiality; access can be obtained by submitting a request via the GSA-Human platform, reviewed by the study sponsor and ethics committee within 8 weeks, with a signed data access agreement. The study protocol and statistical analysis plan are provided in the Supplementary Information. The TCGA-HNSC RNA-seq data used in this study are available in the UCSC Xena database (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/). The single-cell RNA-seq data used in this study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession code GSE195832. Source data are provided with this paper.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Zhigang Liu, Dong Wang, Guanjun Li, Muhua Yi, Zhaoyuan Zhang.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41467-025-59865-1.

References

- 1.Shield, K. D. et al. The global incidence of lip, oral cavity, and pharyngeal cancers by subsite in 2012. CA Cancer J. Clin.67, 51–64 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yang, B. et al. Progresses and perspectives of anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibody therapy in head and neck cancers. Front Oncol.8, 563 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferris, R. L. et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N. Engl. J. Med375, 1856–1867 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burtness, B. et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): a randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet394, 1915–1928 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ribas, A. & Wolchok, J. D. Cancer immunotherapy using checkpoint blockade. Science359, 1350–1355 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Solomon, B., Young, R. J. & Rischin, D. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: genomics and emerging biomarkers for immunomodulatory cancer treatments. Semin. cancer Biol.52, 228–240 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mandal, R. et al. The head and neck cancer immune landscape and its immunotherapeutic implications. JCI insight1, e89829 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Galluzzi, L., Zitvogel, L. & Kroemer, G. Immunological mechanisms underneath the efficacy of cancer therapy. Cancer Immunol. Res.4, 895–902 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Topalian, S. L., Taube J. M. & Pardoll D. M. Neoadjuvant checkpoint blockade for cancer immunotherapy. Science367, eaax0182 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.Hecht, M. et al. Safety and efficacy of single cycle induction treatment with cisplatin/docetaxel/ durvalumab/tremelimumab in locally advanced HNSCC: first results of CheckRad-CD8. J. Immunother. Cancer8, e00137 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Huang, X. et al. Neoadjuvant toripalimab combined with gemcitabine and cisplatin in resectable locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (NeoTGP01): an open label, single-arm, phase Ib clinical trial. J. Exp. Clin. Cancer Res.41, 300 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Wise-Draper, T. M. et al. Phase II clinical trial of neoadjuvant and adjuvant pembrolizumab in resectable local-regionally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Clin. Cancer Res.: Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res.28, 1345–1352 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Klochikhin, A. et al. Abstract PO-002: Pembrolizumab as neoadjuvant and adjuvant therapy in combination with standard of care in resectable, locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: Phase 3 KEYNOTE-689. Clin. Cancer Res. 29, PO-002 (2023).

- 14.Uppaluri, R. et al. Neoadjuvant and adjuvant pembrolizumab in resectable locally advanced, human papillomavirus-unrelated head and neck cancer: a multicenter, phase II trial. Clin. Cancer Res26, 5140–5152 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zinner R, et al. Neoadjuvant nivolumab (N) plus weekly carboplatin (C) and paclitaxel (P) in resectable locally advanced head and neck cancer. 38, 6583–6583 (2020).

- 16.Zhang, Z. et al. Neoadjuvant chemoimmunotherapy for the treatment of locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: a single-arm phase 2 clinical trial. Clin. Cancer Res.: Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res.28, 3268–3276 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huang, Y. et al. Neoadjuvant immunochemotherapy for locally advanced resectable oral squamous cell carcinoma: a prospective single-arm trial (Illuminate Trial). Int. J. Surg. (Lond., Engl.)109, 2220–2227 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tang, Q. et al. Camrelizumab in combination with doxorubicin, cisplatin, ifosfamide, and methotrexate in neoadjuvant treatment of resectable osteosarcoma: a prospective, single-arm, exploratory phase II trial. Cancer Med.13, e70206 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Herrera, F. G. et al. Low-dose radiotherapy reverses tumor immune desertification and resistance to immunotherapy. Cancer Discov.12, 108–133 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Barsoumian, H.B. et al. Low-dose radiation treatment enhances systemic antitumor immune responses by overcoming the inhibitory stroma. J. Immunother. Cancer8, e000537 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Twyman-Saint Victor, C. et al. Radiation and dual checkpoint blockade activate non-redundant immune mechanisms in cancer. Nature520, 373–377 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Deng, L. et al. STING-dependent cytosolic DNA sensing promotes radiation-induced type I interferon-dependent antitumor immunity in immunogenic tumors. Immunity41, 843–852 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Deng, L. et al. Irradiation and anti-PD-L1 treatment synergistically promote antitumor immunity in mice. J. Clin. Investig.124, 687–695 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Demaria, S. et al. Immune-mediated inhibition of metastases after treatment with local radiation and CTLA-4 blockade in a mouse model of breast cancer. Clin. Cancer Res.: Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res.11, 728–734 (2005). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kunos, C. A. et al. Low-dose abdominal radiation as a docetaxel chemosensitizer for recurrent epithelial ovarian cancer: a phase I study of the gynecologic oncology group. Gynecologic Oncol.120, 224–228 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ngoi, N. Y. L. et al. Phase 1 study of low-dose fractionated whole abdominal radiation therapy in combination with weekly paclitaxel for platinum-resistant ovarian cancer (GCGS-01). Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys.109, 701–711 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arnold, S. M. et al. Low-dose fractionated radiation as a chemopotentiator of neoadjuvant paclitaxel and carboplatin for locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: results of a new treatment paradigm. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol., Biol., Phys.58, 1411–1417 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gleason, J. F. Jr. et al. Low-dose fractionated radiation with induction chemotherapy for locally advanced head and neck cancer: 5 year results of a prospective phase II trial. J. Radiat. Oncol.2, 35–42 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Arnold, S. M. et al. Using low-dose radiation to potentiate the effect of induction chemotherapy in head and neck cancer: results of a prospective phase 2 trial. Adv. Radiat. Oncol.1, 252–259 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Leidner, R. et al. Neoadjuvant immunoradiotherapy results in high rate of complete pathological response and clinical to pathological downstaging in locally advanced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. J. Immunother. Cancer9, e002485 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 31.Wang, D. et al. Low-dose radiotherapy promotes the formation of tertiary lymphoid structures in lung adenocarcinoma. Front. Immunol.14, 1334408 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, C. et al. Pan-cancer single-cell and spatial-resolved profiling reveals the immunosuppressive role of APOE+ macrophages in immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy. Adv. Sci. (Weinh., Baden.-Wurtt., Ger.)11, e2401061 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Caronni, N. et al. IL-1β(+) macrophages fuel pathogenic inflammation in pancreatic cancer. Nature623, 415–422 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Nalio Ramos, R. et al. Tissue-resident FOLR2(+) macrophages associate with CD8(+) T cell infiltration in human breast cancer. Cell185, 1189–1207.e1125 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen, J. et al. Low-dose irradiation of the gut improves the efficacy of PD-L1 blockade in metastatic cancer patients. Cancer cell43, 361–379.e310 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Pataer, A. et al. Histopathologic response criteria predict survival of patients with resected lung cancer after neoadjuvant chemotherapy. J. Thorac. Oncol.7, 825–832 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhong, L. P. et al. Randomized phase III trial of induction chemotherapy with docetaxel, cisplatin, and fluorouracil followed by surgery versus up-front surgery in locally advanced resectable oral squamous cell carcinoma. J. Clin. Oncol.31, 744–751 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu, D. et al. Neoadjuvant chemo-immunotherapy with camrelizumab plus nab-paclitaxel and cisplatin in resectable locally advanced squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: a pilot phase II trial. Nat. Commun.15, 2177 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ferrarotto, R. et al. Pilot phase II trial of neoadjuvant immunotherapy in locoregionally advanced, resectable cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck. Clin. Cancer Res.: Off. J. Am. Assoc. Cancer Res.27, 4557–4565 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hellmann, M. D. et al. Pathological response after neoadjuvant chemotherapy in resectable non-small-cell lung cancers: proposal for the use of major pathological response as a surrogate endpoint. Lancet Oncol.15, e42–50 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Altorki, N. K. et al. Neoadjuvant durvalumab with or without stereotactic body radiotherapy in patients with early-stage non-small-cell lung cancer: a single-centre, randomised phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol.22, 824–835 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Shen, P., Qiao, B., Jin, N. & Wang, S. Neoadjuvant immunoradiotherapy in patients with locally advanced oral cavity squamous cell carcinoma: a retrospective study. Invest N. Drugs40, 1282–1289 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Darragh, L. B. et al. A phase I/Ib trial and biological correlate analysis of neoadjuvant SBRT with single-dose durvalumab in HPV-unrelated locally advanced HNSCC. Nat. cancer3, 1300–1317 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Li, S. et al. Low-dose radiotherapy combined with dual PD-L1 and VEGFA blockade elicits antitumor response in hepatocellular carcinoma mediated by activated intratumoral CD8(+) exhausted-like T cells. Nat. Commun.14, 7709 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wang, J. et al. Exploring low-dose radiotherapy to overcome radio-immunotherapy resistance. Biochimica et. Biophysica Acta Mol. basis Dis.1869, 166789 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vos, J. L. et al. Neoadjuvant immunotherapy with nivolumab and ipilimumab induces major pathological responses in patients with head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Commun.12, 7348 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Guo, Z. et al. TELO2 induced progression of colorectal cancer by binding with RICTOR through mTORC2. Oncol. Rep.45, 523–534 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ni, C. et al. ACOT4 accumulation via AKT-mediated phosphorylation promotes pancreatic tumourigenesis. Cancer Lett.498, 19–30 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stuart, T. et al. Comprehensive integration of single-cell data. Cell177, 1888–1902.e1821 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Newman, A. M. et al. Determining cell type abundance and expression from bulk tissues with digital cytometry. Nat. Biotechnol.37, 773–782 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Description of Addtional Supplementary Files

Data Availability Statement

Due to confidentiality agreements, patient-related information cannot be disclosed. The study protocol and statistical analysis plan will be made available as a supplementary note in the supplementary information file. Qualified researchers who wish to access deidentified participant data must submit a proposal to the corresponding author, outlining the reasons for their application. The leading clinical site and sponsor will review the applications to determine their compliance with the confidentiality agreements and will respond within 8 weeks. A data access agreement with the sponsor is required before sharing any data. The single-cell RNA-seq raw data generated in this study have been deposited in the Genome Sequence Archive for Human (GSA-Human) database under accession code HRA010554 (https://ngdc.cncb.ac.cn/gsa-human/submit/hra/subHRA015433/finishedOverview). These data are available under restricted access to protect participant confidentiality; access can be obtained by submitting a request via the GSA-Human platform, reviewed by the study sponsor and ethics committee within 8 weeks, with a signed data access agreement. The study protocol and statistical analysis plan are provided in the Supplementary Information. The TCGA-HNSC RNA-seq data used in this study are available in the UCSC Xena database (https://xenabrowser.net/datapages/). The single-cell RNA-seq data used in this study are available in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database under accession code GSE195832. Source data are provided with this paper.