ABSTRACT

Background

Painful intervertebral disc (IVD) degeneration (IVDD) involves chronic inflammation. Developing translational immunomodulatory strategies for IVDD is a priority with tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNFα) signaling an important target. TNFα binds to 2 receptors (TNFRs), with TNFR1 signaling promoting catabolism and apoptosis and TNFR2 signaling promoting anabolism and proliferation.

Methods

This study developed translational strategies to evaluate and modulate TNFR1 and TNFR2 signaling in rat in vivo and in vitro IVDD models. We used blocking antibodies, the TNFR2‐activator Atsttrin, and small molecule inhibitors of TNFR1 to discern distinct TNFR1 and TNFR2‐effects on annulus fibrosus (AF) and nucleus pulposus (NP) cells and to identify effective strategies for modulating specific TNFRs.

Results

TNFR1 was significantly increased with IVDD in vivo in the NP while TNFR2 was unaffected with very faint staining. TNFR1‐specific small molecule inhibitors were effective in reducing catabolic effects of TNFα, highlighting the efficacy of this small molecule strategy for TNFR1 signaling modulation. Meanwhile, TNFR1 and TNFR2 inhibition in vitro was not effective with blocking antibodies on NP or AF cells, likely due to species‐specificity of available blocking antibodies. Further, TNFR2 activation with Atsttrin was similarly ineffective, likely due to extremely low TNFR2 levels in both AF and NP cells.

Conclusions

TNFα receptor‐specific signaling is important in rat IVDD in vivo and in vitro. TNFR1 inhibition was more effective with small molecules than using blocking antibodies. Low levels of TNFR2 in rat AF and NP cells and lack of efficacy of TNFR2‐activator Atsttrin suggest native AF and NP cells have little capacity for TNFR2‐dependent IVD repair.

Keywords: Atsttrin, Cell Culture, ErythrosineB, inflammation, intervertebral disc degeneration, Physcion‐8‐O‐β‐D‐monoglucoside, small molecules, tumor necrosis factor alpha

TNFα receptor‐specific signaling is important in rat IVDD in vivo and in vitro. TNFR1 inhibition was more effective with small molecules than with blocking antibodies. Low levels of TNFR2 in rat AF and NP cells, and the lack of efficacy of TNFR2‐activator Atsttrin, suggest that native AF and NP cells have little capacity for TNFR2‐dependent IVD repair.

1. Introduction

Low back pain is a leading cause of global disability, estimated at approximately 64.9 million years lived with disability [1]. Low back and neck pain also had the greatest health care expenditure among 154 conditions evaluated in 2016, with an estimated $134.5 billion in the US [2]. Back pain includes complex and often interacting pain syndromes, including nociceptive pain, neuropathic pain, and neuroplastic pain, and these pain syndromes are often initiated or fail to resolve due to pathologies of the intervertebral disc (IVD) [3]. IVD degeneration (IVDD) is the most common diagnosis in back pain patients, affecting 40% of individuals aged 40 years or older and 80% of individuals aged 80 or older [4]. IVDD involves defects that cause pain and disability from loss of structural integrity and chronic inflammation due to poor IVD healing. IVDD can affect both annulus fibrosus (AF) and nucleus pulposus (NP) regions of the IVD including diminished anabolic production of extracellular matrix (ECM) proteins and enhanced catabolic and matrix breakdown [5]. There is a need for improved strategies to limit the catabolic shift of IVDD that is often attributed to chronic pro‐inflammatory conditions [6, 7, 8].

Chronic inflammation with TNFα signaling is a hallmark of painful IVDD [8, 9]. TNFα is highly expressed in IVDD and is a key cytokine involved in the inflammatory response, apoptosis, and cell proliferation [10]. There are many members of the TNFα receptor superfamily enabling diverse cellular and biological functions; however, TNFα can only bind two receptors [11]. TNFα is capable of binding as a trimer through two receptors in the IVD: TNFα receptor 1 (TNFR1) and TNFα receptor 2 (TNFR2). Most cell types express TNFR1, and it is therefore considered the primary binding site of TNFα, mediating its proinflammatory effects. TNFR2, however, is not found in all cell types, and its presence in immune cells, endothelial cells, and chondrocytes suggests importance in IVDD and IVD cells [12]. TNFR1 signaling involves the cytoplasmic death domain, which causes either apoptosis via caspase‐family signaling or cell survival via NF‐κB signaling [10]. TNFR2 lacks a cytoplasmic death domain and therefore promotes cell proliferation and survival through the PI3K/Akt pathway [10]. Consistent with these differing roles, TNFR1 deletion decreased IVDD severity in mice while TNFR2 deletion increased IVDD severity [12].

Developing TNFα inhibition strategies remains challenging with variable success in the literature. Broad‐acting TNFα inhibitors (e.g., infliximab, etanercept, and adalimumab) are widely used in the treatment of autoimmune disorders marked by inflammation and have been successful in decreasing pain levels significantly in conditions such as rheumatoid arthritis [13], Crohn's disease [14], and psoriasis [15]. Nevertheless, TNFα inhibition trials demonstrate widely varying efficacy among patient populations, and 60% of patients with rheumatoid arthritis do not reach a threshold of 50% improvement or experience recurrent pain after treatment [16]. Furthermore, in discogenic pain and radiculopathy patients, etanercept was also ineffective in lowering pain and disability scores [17]. However, some clinical trials and animal studies show efficacy in treating discogenic back pain [6, 18, 19], highlighting a need for greater clarity on TNFα‐signaling. We believe broad‐acting TNFα inhibitors show mixed results and limited efficacy for clinical spinal applications since they bind to soluble TNFα and therefore inhibit both catabolic remodeling processes in TNFR1 signaling and reparative processes in TNFR2 signaling. This concept is supported by the findings that TNFR1 knockout mice showed improved IVD repair following injury. Together, the literature shows a need for studies that deepen understanding of the effects of TNFR1 and TNFR2 inhibition in the IVD with a view towards translation.

Several options exist in the literature for TNFR1 and TNFR2 modulation. Previous studies in human cells and in mice have validated specific neutralizing antibodies for human and mouse TNFR1 and TNFR2 [20, 21]. Nevertheless, relatively few blocking antibodies are available commercially for TNFR1 and TNFR2. Atsttrin, an engineered protein that acts as a TNFR2 activator, inhibited TNFα‐mediated catabolism in in vivo mouse and rat models of osteoarthritis by selectively enhancing TNFR2 activity and blocking TNFR1 [22]. In the IVD, Atsttrin was used in one study to demonstrate the potential for inhibiting inflammatory processes in mouse IVD in vivo and human NP cells in vitro (Ding et al., 2017), warranting further investigation of Atsttrin as a TNFR2 activator and TNFR1 inhibitor in the IVD. Small molecules also show promise blocking TNFR1, with some discovered in silico and others showing efficacy in vitro [23, 24, 25]. Physcion‐8‐O‐β‐D‐monoglucoside (PMG) is a naturally derived compound identified through screening to have a strong affinity for TNFR1 and an ability to prevent TNFα‐induced apoptosis in cell lines [23]. ErythrosineB (EryB) is an FDA‐approved food coloring also identified through screening to be an inhibitor of the TNFR1‐TNFα complex by preventing TNFR1‐TNFα protein–protein interaction and has showed efficacy in preventing TNFα induced TNFR1 downstream signaling in cell lines [25]. Neither compound has been previously investigated regarding the IVD.

Literature therefore highlights 2 key gaps. First, while TNFα signaling is of major significance in IVDD, there is limited research on distinct TNFR1 and TNFR2 responses in IVD cells. Second, there is a general lack of translational strategies for TNFR1‐ and TNFR2‐specific inhibition in IVD cells. Our studies addressed these research needs using a rat IVDD model for tissue and cell experiments and analyses, since rats are commonly used in IVD research and rat IVD puncture models to induce discogenic pain are well established [26, 27, 28]. This study had three aims: (1) use an in vivo rat AF puncture injury model to evaluate the effects of IVDD on TNFR1 and TNFR2 levels; (2) use in vitro rat AF and NP cell models to determine the relative importance of TNFR1 and TNFR2 responses to a TNFα challenge; (3) use in vitro rat AF and NP cell models to develop translational strategies for selective TNFR1‐ and TNFR2‐specific inhibition using blocking antibodies, the TNFR2 agonist Atsttrin, and small molecules PMG and EryB. We hypothesized we would identify a translational strategy to selectively inhibit TNFR1 and activate TNFR2, and demonstrate that TNFR1 inhibition protects IVD cells from a pro‐inflammatory challenge while TNFR2 activation promotes IVD cell repair.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Histochemical Analyses of IVDs of Rat In Vivo Discogenic Pain Model

With IACUC approval, skeletally mature Sprague–Dawley rats aged 5–6 months (Charles River; Wilmington, MA) underwent either a control (Sham) surgery or AF puncture injury surgery of L3/4, L4/5, and L5/6 lumbar IVDs as described in another study [27]. Sham surgery included an anterior abdominal incision through the skin and peritoneal membrane and exposure of the L3/4, L4/5, and L5/6 IVDs with no annular needle puncture. AF puncture injury animals used the same exposure approach, but IVDs were punctured with a 26G needle and delivered 2.5 μL of 0.1 ng/μL TNFα. After 6 weeks, motion segments were fixed, decalcified, paraffin‐embedded, and sagittally sectioned at 5 μm thickness. Immunohistochemistry methods, as described [6, 29], were used to assess TNFR1 and TNFR2. Sections were stained for receptor positivity using polyclonal TNFR1 antibody (ab111119, Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) at a dilution of 1:400 and monoclonal TNFR2 antibody (bsm‐52938r, Bioss, Massachusetts, USA) at a dilution of 1:100; TNFR2 IHC was confirmed with an additional antibody (ab109322, Abcam) (1:800 dilution). Rat brain and bone marrow tissue were used for positive IHC controls, and TNFR1 and TNFR2 antibody titrations were selected to have similar staining intensity in the positive controls and no staining on the negative controls (Figure S1). DAB chromogen labeled secondaries were used for all primary antibodies; sections were counterstained with Toluidine Blue. TNFR1 and TNFR2 IHC was performed on separate but adjacent tissue sections. Digital slide images were obtained by scanning IHC slides using the NanoZoomer S210 (Hamamatsu, Shizuoka, Japan). A region of interest (ROI) was obtained for the AF and NP of each IVD (Figure S2). Quantification of TNFR immunopositivity was performed using manual cell counting or HALO Image Analysis Platform (v3.6.4134.137, Indica Labs, Albuquerque, NM, USA). Color deconvolution was conducted on images via the HALO Brightfield algorithm to separate chromogenic DAB from toluidine blue counterstain. The HALO Multiplex IHC module was used to set a threshold to identify positive and negative staining within the defined regions of interest, quantify total, positive, and negative cells, and calculate percentage of positive and negative cells, or percent (%) immunopositivity. HALO analysis quantified immunopositivity for TNFR1 and TNFR2 (Abcam). TNFR2 (Bioss) immunostaining was more punctate and reliable to manually count in IVD regions.

2.2. Rat AF and NP Cell Isolation and In Vitro Cell Culture

For all in vitro experiments, AF and NP cells were isolated from caudal IVDs of 5–6 month skeletally mature Sprague–Dawley rats (Charles River; Wilmington, MA). NP and AF tissue was manually dissected and separated; tissue from eight to 10 IVDs was collected from each rat. AF and NP tissue was finely minced before being incubated in digestion media (DMEM + 1% Pen‐Strep + 0.1% Amphotericin B + 0.2% Ascorbic Acid + 400 units/mL Collagenase II). Tissues were placed on a rotator at 37°C for 4–6 h. Once digests were fully dissolved, an equal volume of complete culture media (DMEM + 10% Fetal Bovine Serum + 1% Pen‐Strep + 0.1% AmpB + 0.2% AA) was added and mixed with a 21G needle and syringe to break up clumps. Digests were filtered through a 70 μm cell strainer and spun in a centrifuge at 800 × G speed for 10 min at room temperature. Cells were placed in culture (37°C, 5% CO2, normoxia) and expanded for 1 passage prior to further use. Cell culture methods were similar to that described in a previous study [29].

2.3. Fluorescent Immunostaining of Caspase‐3

Rat AF and NP cells were grown on 12‐well chamber slides (Ibidi, Grafelfing, Germany) at an initial seeding density of 5000 cells/cm [2]. Cells were subject to TNFα challenge (10 ng/mL) for 24 h. After treatment, cells were fixed, permeabilized, and stained with ɑCleaved Caspase‐3 primary antibody at a 1:1000 dilution (rabbit polyclonal ɑCleaved Caspase‐3; Abcam, Cambridge, United Kingdom) and secondary antibody at a 1:400 dilution (Cy5‐conjugated affinipure donkey ɑrabbit; Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA, USA). Negative control wells received secondary antibody and Biocare Medical rabbit negative control drops (Pacheco, CA, USA). Cells were counterstained using DAPI. Images were captured at 10× on a Zeiss Axio Imager fluorescence microscope. ImageJ EzColocalization plugin was used to quantify colocalization of DAPI and Cy5 (Caspase‐3) using Pearson's correlation coefficient [30].

2.4. TNFR Activity Modulating Treatments

In the first set of experiments, specific antibodies were tested for inhibition of TNFR1 and TNFR2. Four experimental groups were prepared: Basal (complete culture media only), TNFα (10 ng/mL), anti‐TNFR1 (10 μg/mL) + TNFα (10 ng/mL), and anti‐TNFR2 (10 μg/mL) + TNFα (10 ng/mL). R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN, USA) recombinant TNFR1 neutralizing antibody (MAB225) and recombinant TNFR2 neutralizing antibody (MAB726) were used for anti‐TNFR1 and anti‐TNFR2 conditions. In the second set of experiments, Atsttrin was used to concurrently inhibit TNFR1 and activate TNFR2. Experimental groups included: Basal (complete culture media only), TNFα (10 ng/mL), and Atsttrin (0.2 μg/mL) + TNFα (10 ng/mL). In the third set of experiments, small‐molecule modulators were used to inhibit TNFR1. Experimental groups included: Basal (complete culture media only), TNFα (10 ng/mL), EryB (10 μg/mL) + TNFα (10 ng/mL), and PMG (40 μg/mL) + TNFα (10 ng/mL).

2.5. RNA Extraction and qRT‐PCR

After 24 h, treated cells were lysed and RNA was extracted and purified using RNeasy Micro Kit (QIAGEN, Hilden, Germany). RNA concentration was measured using NanoDrop (Fisher Scientific, Hampton, NH, USA). RNA was converted to cDNA using the SuperScript VILO cDNA Synthesis Kit (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). cDNA was then used for qRT‐PCR via the Applied Biosystems 7900HT System (Waltham, MA, USA). Gene expression levels were measured relative to expression of the housekeeping gene Gapdh. Fold change was calculated using the 2−ΔΔCT method. All primers are PrimeTime qPCR primers from Integrated DNA Technologies (Coralville, IA, USA). RNA was also submitted for RNA Sequencing to Genewiz (Azenta Life Sciences). Genewiz performed library preparation by rRNA depletion, sequencing which consisted of 30 million reads per sample (Illumina NovaSeq 6000), alignment, and analyses including principal component analysis and differential gene expression.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

For AF puncture injury and histology, four biological replicates were stained for the sham condition, and six biological replicates were stained for the injury condition. Differences in AF and NP regions between sham and injured conditions for TNFR1 and TNFR2 staining were analyzed in GraphPad Prism (v10) using a parametric two‐way ANOVA with repeated measures, with p < 0.05 considered significant. For ɑCleaved Caspase‐3 staining, three to four biological replicates with two technical replicates were assessed for basal and TNFα‐challenged conditions. Data points represent separate biological replicates, column bars indicate mean, and error bars portray one standard deviation. Statistical significance was analyzed in GraphPad Prism (La Jolla, CA, USA) using a paired Student's t‐test with p < 0.05 considered significant. RNA isolation and gene expression analyses were performed on four to seven biological replicates with two technical replicates for each condition and cell type. Differences in gene expression of Tnfrsf1a and Tnfrsf1b between Basal and TNFα were analyzed using a two‐way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test, with p < 0.05 considered significant. Relative Tnfrsf1a and Tnfrsf1b expression was calculated as fold change normalized to Gapdh (2−ΔCT), and the effect of TNFα on Tnfrsf1a and Tnfrsf1b expression was calculated as fold change normalized to basal (2−ΔΔCT). Differences in gene expression with antibody, Atsttrin, or small molecule inhibitor treatments were analyzed using the Kruskal‐Wallis test with Dunn's post hoc test with p < 0.05 considered significant. Differences in gene expression for 24‐ and 96‐h conditions were analyzed with two‐way ANOVA with Tukey's post hoc test, with p < 0.05 considered significant. All data was tested for normality using the Shapiro–Wilk test.

3. Results

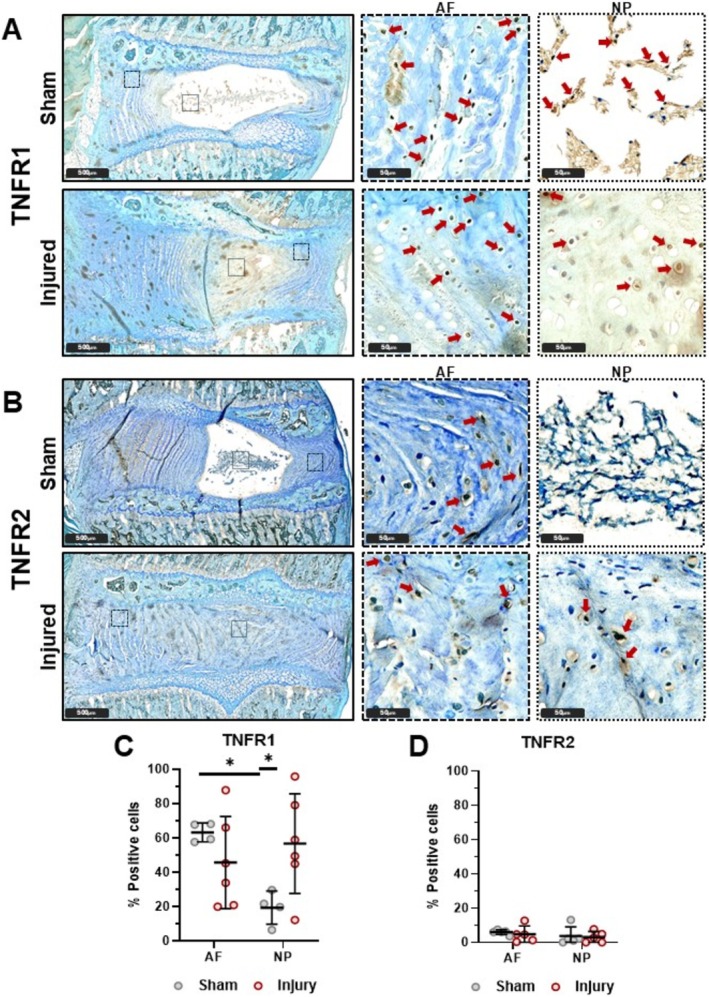

3.1. TNFR1 Is Increased With IVDD in Rats In Vivo, With More TNFR1 Than TNFR2

TNFR1 and TNFR2 levels were assessed on 5–6‐month‐old Sham and Injured rats evaluated 6 weeks post‐injury using immunohistochemistry. TNFR1 immunostaining was dark and present at greater quantities in the AF than in the NP region of the IVD in sham conditions (Figure 1A,C). IVD Injury significantly increased TNFR1 levels in the NP region and caused a more variable response in the AF region. There were no significant differences in TNFR2 levels between IVD regions or injury conditions (Figure 1B,D). A lower percent immunopositivity was observed with TNFR2 compared to TNRF1, and TNFR2 staining was faint compared to TNFR1 (although staining intensity was not quantified). TNFR2 staining was confirmed using a second TNFR2 antibody (Abcam, Figure S3) where staining was even more faint, and percent positivity was not affected by tissue type or injury (Figure S3), although overall percent positivity was greater than for the Bioss TNFR2 antibody (Figure 1). Together, we concluded that TNFR1 was present in abundance in AF and NP cells and TNFR1 levels appear to be responsive to injury. Meanwhile, TNFR2 is in low abundance in IVD cells and does not respond to IVD injury.

FIGURE 1.

TNFR1 is greater in AF than in NP and is affected by injury in NP. Sham (n = 4 AF, n = 4 NP) and injured (n = 6 AF, n = 6 NP) rat lumbar IVDs with TNFR1 (A, C) and TNFR2 (B, D) IHC with TolBlue counterstain. TNFR1 is greater in AF than in NP for Sham. TNFR1 is greater in Injury than Sham in NP. TNFR2 is lowly expressed and is not affected by IVD region or injury condition. (4‐6 biological donors; *p < 0.05).

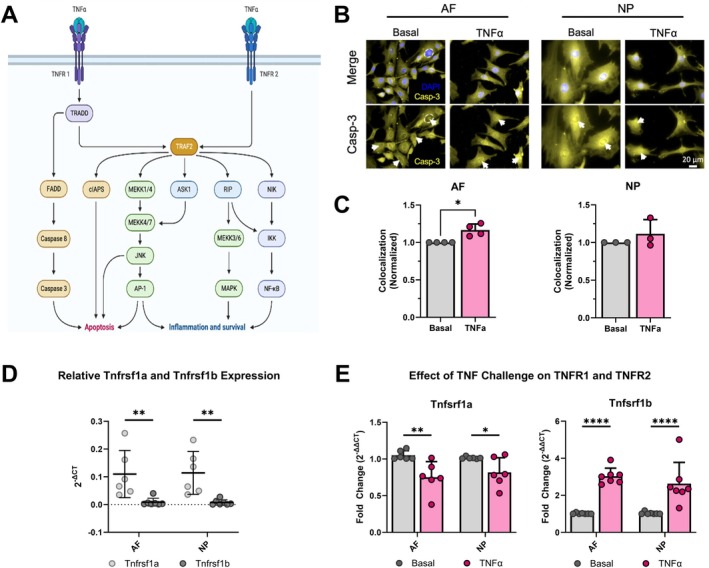

3.2. TNFα‐Challenge Activates TNFR1 Signaling and Modulates Tnfrsf1a and Tnfrsf1b Expression in Rat AF and NP Cells In Vitro

TNFR1 signaling was investigated by staining for ɑCleaved Caspase‐3, involved in TNFR1‐mediated apoptosis, in NP and AF cells in vitro. ɑCleaved Caspase‐3 nuclear colocalization was significantly increased with TNFα challenge in AF cells (Figure 2B,C), indicating TNFα signaling through TNFR1, and with greater TNFR1 signaling in AF cells than NP cells. Expression of Tnfrsf1a and Tnfrsf1b was further assessed on cells in vitro, and the strongest finding was that Tnfrsf1a is much more highly expressed than Tnfrsf1b in both AF and NP regions in basal cells (Figure 2D). Interestingly, TNFα challenge significantly altered both Tnfrsf1a and Tnfrsf1b expression in that Tnfrsf1a was downregulated while Tnfrsf1b was upregulated in both AF and NP cells (Figure 2E). However, Tnfrsf1a expression was still significantly higher than Tnfrsf1b even with TNFα challenge.

FIGURE 2.

TNFα challenge activates TNFR1 signaling with increased cleaved Caspase‐3 and modulates TNFR1 and TNFR2 expression. (A) TNFα receptors (TNFR1 and TNFR2) and their respective signaling pathways (created using the TNFα Pathway template on BioRender). Rat AF and NP cells in vitro subject to 24‐h TNFα challenge werer measured for, (B) Caspase‐3 (yellow) colocalized with DAPI (blue) to identify apoptotic cells (white arrows) quantified on ImageJ; (C) Caspase‐3 expression within the nucleus increased for AF but not for NP (n = 3–4). (D) qRT‐PCR (2−ΔCT) of TNFα receptor expression (Tnfrsf1a: n = 6; Tnfrsf1b: n = 7) in AF and NP under basal conditions (normalized to Gapdh). (E) qRT‐PCR (2−ΔΔCT) of TNFα receptor expression (Tnfrsf1a: n = 6; Tnfrsf1b: n = 7) in AF and NP under basal and TNFα conditions (normalized to Gapdh and basal). (B, C) (3 technical replicates; 3‐4 biological donors; *p < 0.05). (D, E) (3 technical replicates; 6‐7 biological donors; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

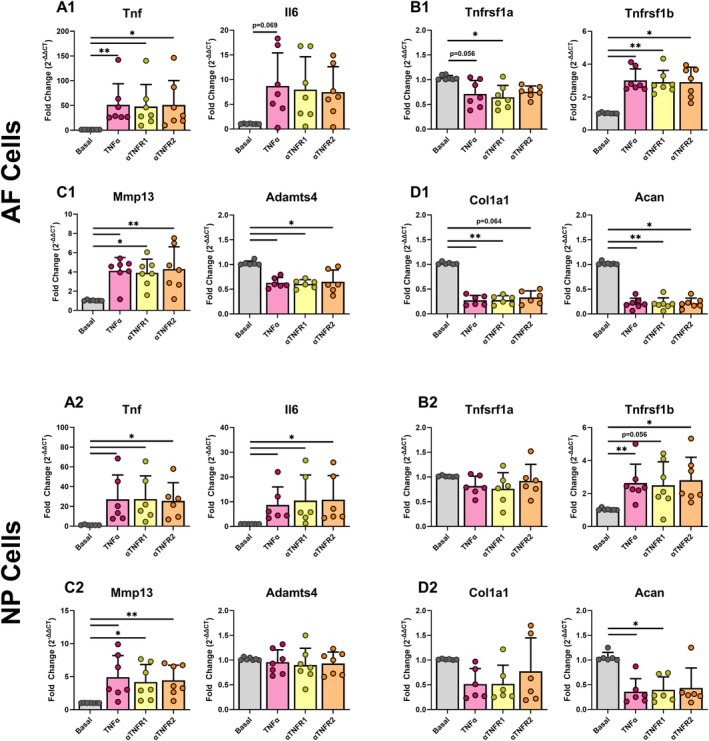

3.3. TNFα Caused a Pro‐Inflammatory and Catabolic Shift in AF and NP Cells With No Effects of TNFR1 or TNFR2 Antibody Blocking

Gene expression was measured for inflammatory cytokines (Tnf, Il6), TNFα receptors (Tnfrsf1a, Tnfrsf1b), catabolic ECM genes (Mmp13, Adamts4), and anabolic ECM genes (Col1a1, Acan) using qRT‐PCR in AF and NP cells (Figure 3). As expected, TNFα caused a pro‐inflammatory and catabolic shift in AF and NP cells, exemplified by the upregulation of catabolic ECM genes (Tnf, Il6, Mmp13) and the downregulation of anabolic ECM genes (Col1a1, Acan) in the TNFα group. However, antibody blocking produced no significant effect on any gene investigated in AF cells compared to cells treated with TNFα alone. Because antibody blocking was shown to be effective in chondrocytes, we also evaluated NP cells that are considered a more chondrocyte‐like cell type. Similarly, NP cells exhibited a pro‐inflammatory and catabolic shift in gene expression patterns with no effects of antibody blocking.

FIGURE 3.

TNFα caused a pro‐inflammatory and catabolic shift in AF cells and NP cells with no effects of TNFR1 or TNFR2 antibody blocking. Gene expression of (A1, A2) pro‐inflammatory cytokines, (B1, B2) TNFα receptors, (C1, C2) catabolic, and (D1, D2) anabolic extracellular matrix markers in control and antibody conditions for AF (top) and NP (bottom) cells (3 technical replicates; 7 biological donors; normalized to Gapdh and basal; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

To assess whether the ineffectiveness of antibodies was due to an inability to properly bind within the 24‐h time frame, we also performed an extended duration study to 96 h (Figure S5). All experimental groups contain the same concentrations as those in the 24‐h treatment (Basal, TNFα, anti‐TNFR1, anti‐TNFR2). The extended culture study showed similar findings as the 24‐h study, involving increased pro‐inflammatory cytokines with a catabolic shift following TNFα treatment, but no effects of blocking antibodies.

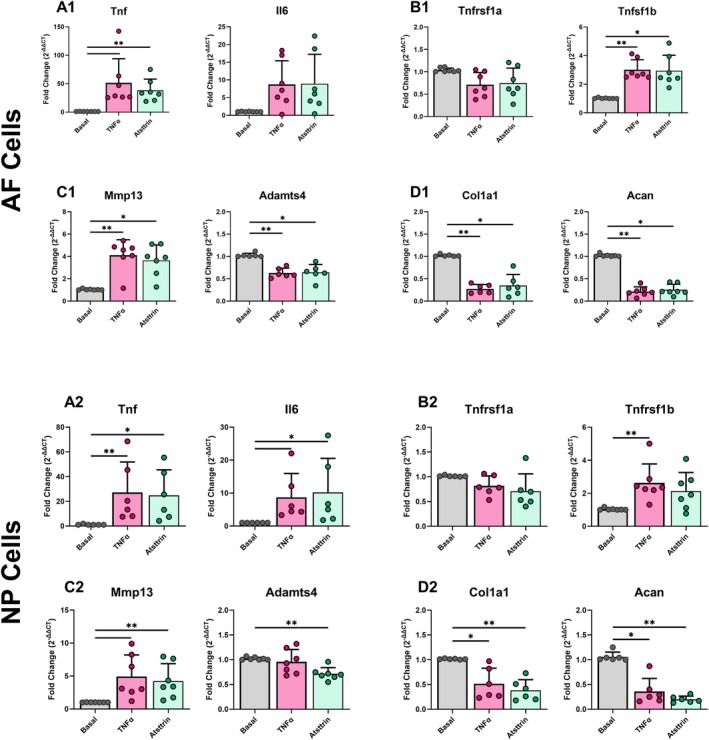

3.4. Atsttrin Had No Effect on Rat AF or NP Cells Subjected to a TNFα Challenge

Atsttrin is a TNFR2 activator known to be effective in chondrocytes and capable of promoting TNFR2 while inhibiting TNFR1 activity in cells of multiple species. Therefore, we next applied Atsttrin to rat AF and NP cells to evaluate its effect in shifting cells to a TNFR2‐driven response. We selected 0.2 μg/mL Atsttrin for all experiments for consistency with studies on human chondrocytes, human NP cells, and mouse astrocytes that were effective using 0.2 μg/mL of Atsttrin [22, 31, 32].

Expression of the same genes as the antibody blocking experiments was assessed using qRT‐PCR on Basal, TNFα, and TNFα + Atsttrin conditions in AF and NP cells. TNFα caused the expected pro‐inflammatory and catabolic shift in AF and NP cells with upregulation of inflammatory and catabolic ECM genes (Tnf, Mmp13) and the downregulation of anabolic ECM genes (Col1a1, Acan) in the TNFα group (Figure 4). Atsttrin, however, produced no significant effects on AF or NP cells as compared to the TNFα group (Figure 4). Similarly to the antibody blocking experiments, we also treated cells with Atsttrin for an extended 96‐h treatment. Extended culture time was not found to affect Atsttrin treatment, with Atsttrin again showing no difference in gene expression versus TNFα alone (Figure S6). Additionally, bulk single‐cell sequencing was performed on cells treated with TNFα or TNFα + Atsttrin. TNFα‐treated cells were found to have significantly altered gene expression compared to basal cells, including upregulation of proinflammatory cytokines and chemokines, while TNFα + Atsttrin was found to have no significantly differentially expressed genes compared to cells treated with TNFα alone (Figure S7).

FIGURE 4.

TNFα caused a pro‐inflammatory and catabolic shift in AF and NP cells with no effect of Atsttrin, suggesting little/no effect of TNFR2 activation on NP or AF cells. Gene expression of (A1, A2) pro‐inflammatory cytokines, (B1, B2) TNFα receptors, (C1, C2) catabolic, and (D1, D2) anabolic extracellular matrix markers in control and Atsttrin treated conditions for AF (top) and NP (bottom) cells (3 technical replicates; 7 biological donors; normalized to Gapdh and basal; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01).

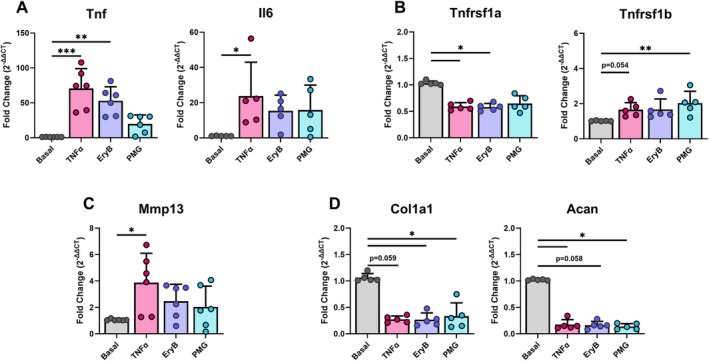

3.5. PMG Prevents the Effects of TNFα on AF Cell Inflammatory and Catabolic Gene Expression but Not Anabolic Gene Expression

Expression of the same genes as the antibody blocking and Atsttrin experiments were assessed using qRT‐PCR on Basal, TNFα, and TNFα + Small‐Molecule‐Modulator conditions in (either PMG or EryB) AF cells. As expected, TNFα caused a pro‐inflammatory and catabolic shift in AF cells, exemplified by the upregulation of catabolic ECM genes (Tnf, Mmp13) and the downregulation of anabolic ECM genes (Col1a1, Acan) in the TNFα group (Figure 5). Both small molecules, PMG and EryB, showed anti‐TNFα effects, decreasing pro‐inflammatory and catabolic genes, Tnf and Mmp13, with effects more pronounced for PMG than EryB (Figure 5). Interestingly, neither PMG nor EryB rescued the decreased anabolic gene expression caused by TNFα.

FIGURE 5.

Small molecule inhibition of TNFR1 partially rescued rat AF and NP cells from TNFα challenge. Gene expression of (A) pro‐inflammatory cytokines, (B) TNFα receptors, (C) catabolic, and (D) anabolic extracellular matrix markers in control and EryB or PMG treated conditions for AF cells (3 technical replicates; 4‐5 biological donors; normalized to Gapdh and basal; *: p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

4. Discussion

The importance of TNFα signaling in IVDD and the distinct roles of TNFR1 and TNFR2 motivated this translational study on selective TNFR inhibition. This study evaluated the relative abundance of TNFR1 and TNFR2 in IVD cells, and the effects of differential inhibition and activation of TNFRs using rat in vivo and in vitro models. In vivo and in vitro studies showed that TNFR1 levels responded to IVDD and TNFα, and that TNFR1 inhibition could rescue IVD cell responses in support of our hypothesis. However, TNFR2 levels were extremely low in AF and NP cells, and Atsttrin delivery had no effect on IVD cell responses, suggesting TNFR2 levels were too low to have an effective response in IVD cells in vitro. Neither TNFR1 nor TNFR2 blocking antibodies altered AF or NP cell response to TNFα challenge, highlighting technical and biological challenges with selective TNFR1 and TNFR2 modulation. Small molecule blocking of TNFR1 was successful in rescuing AF cell responsiveness to TNFα challenge, in partial support of our hypothesis, and demonstrated that small molecules were more effective in the selective TNFR1 approach.

Considering the importance of TNFα signaling in IVDD, there are relatively few studies on relative TNFR1 and TNFR2 levels in the IVD. Our results and the literature point to increased TNFR1‐signaling dominating TNFα‐mediated IVDD in rats, but also point to dynamic control of TNFR1 and TNFR2 expression levels. An increase in TNFR1‐signaling in IVDD conditions is the most likely conclusion when considering longer‐term protein responses, blocking studies, and the literature, even though Tnfrsf1a expression levels were decreased after 24‐h TNFα challenge here. Specifically, this study showed TNFR1 levels were increased in NP regions of IVDs in vivo 6 weeks following injury, and ɑCleaved Caspase‐3 was increased in AF cells in vitro following TNFα challenge, which both point to increased TNFR1‐signaling. Most strongly, small molecule inhibition of TNFR1 in AF cells in vitro rescued cells from TNFα challenge, further highlighting the importance of TNFR1 signaling in IVDD conditions. The TNFR1‐signaling in this study is similar to the literature showing increased TNFR1 in IHC in human IVDD conditions [29, 33, 34, 35]. Increased TNFR1 signaling is also consistent with human NP cells under LPS‐induced IVDD, or IVDD conditioned‐media challenge where TNFR1 gene and protein expression were both increased [29, 36]. Furthermore, TNFR1 inhibition has strong effects in limiting IVDD since TNFR1‐CRISPRi modulation to inhibit TNFR1‐signaling in a rat in vivo model improved IVDD and pain response [37], and TNFR1−/− mice had reduced degeneration and decreased apoptosis following IVD puncture injury [12]. Increased TNFR1‐signaling after injury is also consistent with osteoarthritic chondrocytes showing upregulated TNFR1 gene expression compared to non‐osteoarthritic cells [38].

This study and the literature suggest TNFR2 levels in IVD cells are too low to mount a TNFR2‐mediated repair response in IVD cells. Specifically, in vivo IHC showed lower TNFR2 immunopositivity (5%–10%) compared to TNFR1 (50%–70% AF, 10%–30% NP). Additionally, our in vitro study determined Tnfrsf1a levels to be > 10‐fold larger than Tnfrsf1b in both AF and NP regions in control tissue (assuming similar reaction efficiencies in the qPCR analyses). Therefore, Tnfrsf1b expression levels in AF and NP cells in vitro remained very low even though they were somewhat increased with TNFα challenge. Furthermore, when activating TNFR2 signaling with Atsttrin, there was no reduction in pro‐inflammatory or catabolic genes or recovery of anabolic genes. We believe the lack of effect of Atsttrin (in both inhibiting TNFR1 and activating TNFR2) is due to the limited TNFR2 levels in IVD cells, since Atsttrin was shown to lose efficacy in TNFR2−/− mice [12]. Our Atsttrin studies also demonstrated high rigor since Atsttrin lacked efficacy in both AF and NP cells at 24 and 96 h. However, this study is also limited since we did not detect effects of TNFR2 modulation, and therefore we can only infer that rat AF and NP cells lack sufficient TNFR2 to enable a biologically detectable effect. Atsttrin was effective in osteoarthritis animal models and chondrocytes [39], suggesting chondrocytes may have greater TNFR2 expression and signaling than AF and NP cells. TNFR2 signaling may remain important for IVD in vivo healing, since IVDD severity and apoptosis increased following IVD puncture in TNFR2−/− mice [12]. We believe this finding to be associated with high TNFR2 responsiveness in immune and other cell populations known to contain higher levels of TNFR2 than IVD cells [29].

Lack of efficacy of TNFR1 and TNFR2 antibody blocking in the simplified in vitro rat IVD cell culture system used in this study points to challenges with antibody blocking strategies for IVD repair. Lack of antibody blocking at 24 h was also confirmed at 96 h to allow for more time for blocking antibodies to bind. Selective receptor blocking with TNFR1 and TNFR2 antibodies also had no significant effect on AF or NP cells under TNFα challenge for any time point. The antibodies used in this experiment are antibodies validated to be reactive in humans and were used in this study since commercially available neutralizing antibodies for TNFR1 and TNFR2 that are reactive to rats were not found. Reactivity to rat has not been validated for these antibodies, though some literature suggests efficacy in mice [20, 21]. Murine TNFR1 and TNFR2 are only approximately 60%–70% identical to human TNFRs [40], suggesting binding with rat was worth pursuing in this study. Yet, the homology between murine and human TNFα receptors does not ensure the locations of their homologies are evenly distributed, which is an element that would be required for antibody blocking. TNFR1 is most highly conserved in the extracellular domain while TNFR2 is most highly conserved in the intracellular domain [40]. Therefore, lack of conservation in the extracellular domain may induce species specificity of blocking antibodies. Furthermore, species variation exists in the TNFα molecule itself, which shares 69% sequence identity and 85% homology between murine and human, and can also limit antibody blocking strategies [41]. The TNFR1 blocking antibody in this study partially rescued hAF cells from degenerative conditions with a less catabolic phenotype and upregulated genes involved in cell division [29], suggesting species specificity. The antibody concentration used to block TNFR1 and TNFR2 in our in vitro study (10 μg/mL) was also effective in modulating TNFα effects in human AF cells [29], human rheumatoid arthritis synoviocytes [42], bronchial epithelial cells [43], and T cells [44]. This study is limited since we did not pursue antibody binding affinity studies or antibody pretreatment studies, yet when comparing with the literature, we felt results motivated a need for an alternative approach and that the lack of efficacy of TNFR1 and TNFR2 blocking antibodies in this study strongly suggests species specificity, highlighting challenges applying antibody blocking studies in preclinical models of different species.

The small molecules EryB and PMG were both effective in inhibiting TNFR1 signaling in rat AF cells in this study. PMG had the largest effect in rescuing TNFα‐induced inflammation and catabolism, and such findings are similar to broad‐acting TNFα inhibitors such as infliximab [45]. Interestingly, TNFR1 inhibition was not capable of rescuing an anabolic phenotype, which is likely because IVDD conditions play a substantial role in reducing cell metabolism rates and activating the TNFR1‐associated Death Domain to drive apoptosis and senescence [29, 46, 47]. We conclude that small molecules have the most compelling results for translational studies because of the lack of species specificity, and their small size enables rapid transport and uptake by cells.

This study and the literature strongly suggest that TNFR2 may not be present in high enough quantities in AF cells to mount an effective TNFR2‐mediated reparative response. Gansau et al. similarly implicated low levels of TNFR2 in human AF cells as a factor limiting TNFR2‐affecting treatment strategies, and similarly showed TNFR2 blocking antibody and Atsttrin had negligible effects on human AF cells challenged with IVDD conditioned media [29]. We did not identify small molecules capable of TNFR2 activation but used Atsttrin as our TNFR2 activator, which has a molecular weight of 16.94 kDa [32] and is therefore slightly larger than most small molecules (~0.9 kDa), yet remains ~5–10× smaller than most blocking antibodies and is not considered species‐specific. Since Atsttrin functions in multiple species but had no effects on rat AF or NP cells in this study, we concluded there remains too little TNFR2 in rat AF and NP cells for TNFR2 activation to have a strong effect in vitro. IHC in this study also demonstrated very low TNFR2 immunostaining levels, which did not increase after injury, suggesting rat IVDD in vivo was driven predominantly by TNFR1 signaling without shifting to TNFR2‐mediated repair. The negative TNFR2 results and low TNFR2 percent positivity (Figure 1) motivated validation with an additional assay. TNFR2 IHC using a primary antibody from a different vendor similarly showed no effects of tissue type or injury on TNFR2 staining and had even fainter TNFR2 immunostaining, although percent positivity was higher (Figure S3). Together, TNFR2 IHC findings using two different primary antibodies suggest very low TNFR2 levels in IVD cells. Furthermore, our gene expression findings provide a more direct quantitative comparison and identified Tnfrsf1b levels to be 10–100‐fold lower than Tnfrsf1a. Taken together, this paper and the literature suggest that AF and NP cells have very low TNFR2 levels, with no suggestion that IVD cells are capable of mounting a TNFR2‐mediated response sufficient to promote effective repair.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, this study used a rat model system to identify relative contributions of TNFR1 and TNFR2 to degenerative conditions and to advance translational strategies for selective TNFR1 and TNFR2 receptor blocking in IVDD. We identified that TNFR2 levels were substantially lower than TNFR1 in AF and NP cells in rats, and were not responsive to Atsttrin treatment to suggest limited capacity for native IVD cells to mount a TNFR2‐mediated repair response, although it is likely that TNFR2 positive immune (or other cells) play important roles in IVD healing responses in vivo. We also demonstrated that selective TNFR1 and TNFR2 inhibition is technically challenging because of the species specificity of blocking antibodies and the limited TNFR2 levels in both AF and NP cells. We found small molecule blocking of TNFR1 with the small molecule PMG was the most effective strategy for selective TNFR1 inhibition, which rescued IVD cells from catabolic and pro‐inflammatory TNFα challenge. We therefore conclude that small molecule strategies were more effective than antibody approaches in controlling IVD cell responses to TNFα‐mediated IVDD. However, neither TNFR1 inhibition nor Atsttrin–TNFR2 activation could restore anabolic metabolism, suggesting that additional immunomodulatory strategies and cells are required to promote repair following TNFα‐induced IVDD.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: T.D.J., J.G., and J.C.I. Study design: T.D.J., J.G., S.O.Y., J.M., and J.C.I. Resource acquisition: T.D.J., S.O.Y., J.G., J.M., and J.C.I. Performed experiments: T.D.J., S.O.Y., J.G., J.M., and D.L. Analyzed and interpreted the results, and prepared the figures: T.D.J., S.O.Y., J.G., J.M., D.L., and J.C.I. Funding acquisition: J.C.I. Project administration: T.D.J., and J.C.I. Supervision: T.D.J., J.G., and J.C.I. Writing – original draft: S.O.Y., T.D.J., and J.C.I. Writing – review and editing, approval: T.D.J., S.O.Y., J.G., J.M., D.L., and J.C.I.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Supporting information

Table S1. jsp270070‐sup‐0001‐Supinfo.

Table S2. jsp270070‐sup‐0001‐Supinfo.

Figure S1. Positive staining controls in rat brain and bone marrow for TNFR1 (A) and TNFR2 (B) IHC, serum negative control in brain (C).

Figure S2. (A) Example of lumbar spine with IHC staining TNFR2 with Toluidine Blue as a counterstain that was slide scanned. The black box shows a zoomed image from one sham IVD at level L4/5 and annotated for ROI used for quantification. Example of an ROI for AF (red) and NP (green) regions. These ROIs were used for quantification of IHC positivity.

Figure S3. IHC of TNFR2 using monoclonal TNFR2 antibody (ab109322, Abcam) (1:800 dilution) in control (A) and experimental tissue (B, C). No difference in TNFR2 immunopositivity was noted between tissues or injury conditions (C) in agreement with previous TNFR2 IHC (Figure 1). Overall, staining intensity was very faint with this antibody, although the rate of immunopositivity was higher.

Figure S4. H2O2 treated AF cell positive control (A) and negative staining control (B) for Casp3 ICC.

Figure S5. TNFR1 and TNFR2 blocking antibodies had similar effects at 24 and 96 h in both rat AF and NP cells indicating that longer‐duration antibody exposure did increase their efficacy modulating TNFα responses. (Top) Experimental design for 96 h blocking study. Gene expression of (A1, A2) pro‐inflammatory cytokines, (B1, B2) TNFα receptors, (C1, C2) catabolic, and (D1, D2) anabolic extracellular matrix markers in basal and 24 or 96 h antibody conditions for AF (top) and NP (bottom) cells (3 technical replicates; n = 3 biological donors; normalized to Gapdh and basal; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

Figure S6. Atsttrin had similar effects at 24 and 96 h in both rat AF and NP cells. Atsttrin efficacy was not dependent on cell type or culture duration as assessed with qRT‐PCR for (A1, A2) pro‐inflammatory cytokines, (B1, B2) TNFα receptors, (C1, C2) catabolic, and (D1, D2) anabolic extracellular matrix markers in basal and 24 or 96 h antibody conditions for AF (top) and NP (bottom) cells (3 technical replicates; 3 biological donors; normalized to Gapdh and Basal; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

Figure S7. RNA sequencing shows effects of TNFα but not Atsttrin and AF cell transcriptome. (A) PCA shows distinct separation of Basal cells from TNFα and TNFα + Atsttrin treated cells. (B) Differential gene expression analysis showed a large number of significantly different genes between Basal and TNFα treated cells; however, no differentially expressed genes were observed between TNFα and TNFα + Atsttrin treated cells.

Acknowledgments

Thank you to Dr. Minghui Wang for guidance on RNA‐Seq analyses. Thank you to Dr. Chuanju Liu and Dr. Wenyu Fu for providing the Atsttrin used here as well as their guidance on the design and interpretation of Atsttrin experiments and results.

Funding: This work was supported by National Institute of Arthritis and Musculoskeletal and Skin Diseases, R01AR078857, R01AR080096.

Timothy D. Jacobsen and S. Olga Yiantsos contributed equally to this work.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the Supporting Information. Data and code for RNA‐seq analysis will be made available upon manuscript acceptance.

References

- 1. Wu A., March L., Zheng X., et al., “Global Low Back Pain Prevalence and Years Lived With Disability From 1990 to 2017: Estimates From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017,” Annals of Translational Medicine 8, no. 6 (2020): 299, 10.21037/atm.2020.02.175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. de Luca K., Tavares P., Yang H., et al., “Spinal Pain, Chronic Health Conditions and Health Behaviors: Data From the 2016–2018 National Health Interview Survey,” International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 20, no. 7 (2023): 5369, 10.3390/ijerph20075369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Mosley G. E., Evashwick‐Rogler T. W., Lai A., and Iatridis J. C., “Looking Beyond the Intervertebral Disc: The Need for Behavioral Assays in Models of Discogenic Pain,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1409, no. 1 (2017): 51–66, 10.1111/nyas.13429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Medical Advisory S , “Artificial Discs for Lumbar and Cervical Degenerative Disc Disease ‐Update: An Evidence‐Based Analysis,” Ontario Health Technology Assessment Series 6, no. 10 (2006): 1–98. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Oichi T., Taniguchi Y., Oshima Y., Tanaka S., and Saito T., “Pathomechanism of Intervertebral Disc Degeneration,” JOR Spine 3, no. 1 (2020): e1076, 10.1002/jsp2.1076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Evashwick‐Rogler T. W., Lai A., Watanabe H., et al., “Inhibiting Tumor Necrosis Factor‐Alpha at Time of Induced Intervertebral Disc Injury Limits Long‐Term Pain and Degeneration in a Rat Model,” Journal of Orthopaedic Research 1, no. 2 (2018): e1014, 10.1002/jsp2.1014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Heggli I., Teixeira G. Q., Iatridis J. C., Neidlinger‐Wilke C., and Dudli S., “The Role of the Complement System in Disc Degeneration and Modic Changes,” JOR Spine 7, no. 1 (2024): e1312, 10.1002/jsp2.1312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Purmessur D., Walter B. A., Roughley P. J., Laudier D. M., Hecht A. C., and Iatridis J., “A Role for TNFalpha in Intervertebral Disc Degeneration: A Non‐Recoverable Catabolic Shift,” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 433, no. 1 (2013): 151–156, 10.1016/j.bbrc.2013.02.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Risbud M. V. and Shapiro I. M., “Role of Cytokines in Intervertebral Disc Degeneration: Pain and Disc Content,” Nature Reviews Rheumatology 10, no. 1 (2014): 44–56, 10.1038/nrrheum.2013.160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Wang C., Yu X., Yan Y., et al., “Tumor Necrosis Factor‐Alpha: A Key Contributor to Intervertebral Disc Degeneration,” Acta Biochimica et Biophysica Sinica 49, no. 1 (2017): 1–13, 10.1093/abbs/gmw112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. MacEwan D. J., “TNF Ligands and Receptors–A Matter of Life and Death,” British Journal of Pharmacology 135, no. 4 (2002): 855–875, 10.1038/sj.bjp.0704549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wang S., Sun G., Fan P., Huang L., Chen Y., and Chen C., “Distinctive Roles of Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor Type 1 and Type 2 in a Mouse Disc Degeneration Model,” Journal of Orthopaedic Translation 31 (2021): 62–72, 10.1016/j.jot.2021.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Ma X. and Xu S., “TNF Inhibitor Therapy for Rheumatoid Arthritis,” Biomedical Reports 1, no. 2 (2013): 177–184, 10.3892/br.2012.42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Colombel J. F., Sandborn W. J., Reinisch W., et al., “Infliximab, Azathioprine, or Combination Therapy for Crohn's Disease,” New England Journal of Medicine 362, no. 15 (2010): 1383–1395, 10.1056/NEJMoa0904492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Papp K. A., Tyring S., Lahfa M., et al., “A Global Phase III Randomized Controlled Trial of Etanercept in Psoriasis: Safety, Efficacy, and Effect of Dose Reduction,” British Journal of Dermatology 152, no. 6 (2005): 1304–1312, 10.1111/j.1365-2133.2005.06688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smolen J. S. and Weinblatt M. E., “When Patients With Rheumatoid Arthritis Fail Tumour Necrosis Factor Inhibitors: What Is the Next Step?,” Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases 67, no. 11 (2008): 1497–1498, 10.1136/ard.2008.098111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cohen S. P., Wenzell D., Hurley R. W., et al., “A Double‐Blind, Placebo‐Controlled, Dose‐Response Pilot Study Evaluating Intradiscal Etanercept in Patients With Chronic Discogenic Low Back Pain or Lumbosacral Radiculopathy,” Anesthesiology 107, no. 1 (2007): 99–105, 10.1097/01.anes.0000267518.20363.0d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Sainoh T., Orita S., Miyagi M., et al., “Single Intradiscal Administration of the Tumor Necrosis Factor‐Alpha Inhibitor, Etanercept, for Patients With Discogenic Low Back Pain,” Pain Medicine 17, no. 1 (2016): 40–45, 10.1111/pme.12892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Tobinick E. and Davoodifar S., “Efficacy of Etanercept Delivered by Perispinal Administration for Chronic Back and/or Neck Disc‐Related Pain: A Study of Clinical Observations in 143 Patients,” Current Medical Research and Opinion 20, no. 7 (2004): 1075–1085, 10.1185/030079903125004286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Garcin G., Paul F., Staufenbiel M., et al., “High Efficiency Cell‐Specific Targeting of Cytokine Activity,” Nature Communications 5 (2014): 3016, 10.1038/ncomms4016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Neumann S., Bidon T., Branschadel M., Krippner‐Heidenreich A., Scheurich P., and Doszczak M., “The Transmembrane Domains of TNF‐Related Apoptosis‐Inducing Ligand (TRAIL) Receptors 1 and 2 Co‐Regulate Apoptotic Signaling Capacity,” PLoS One 7, no. 8 (2012): e42526, 10.1371/journal.pone.0042526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Wei J. L., Fu W., Ding Y. J., et al., “Progranulin Derivative Atsttrin Protects Against Early Osteoarthritis in Mouse and Rat Models,” Arthritis Research and Therapy 19, no. 1 (2017): 280, 10.1186/s13075-017-1485-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Cao Y., Li Y. H., Lv D. Y., et al., “Identification of a Ligand for Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor From Chinese Herbs by Combination of Surface Plasmon Resonance Biosensor and UPLC‐MS,” Analytical and Bioanalytical Chemistry 408, no. 19 (2016): 5359–5367, 10.1007/s00216-016-9633-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Chen S., Feng Z., Wang Y., et al., “Discovery of Novel Ligands for TNF‐α and TNF Receptor‐1 Through Structure‐Based Virtual Screening and Biological Assay,” Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling 57, no. 5 (2017): 1101–1111, 10.1021/acs.jcim.6b00672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Ganesan L., Margolles‐Clark E., Song Y., and Buchwald P., “The Food Colorant Erythrosine Is a Promiscuous Protein‐Protein Interaction Inhibitor,” Biochemical Pharmacology 81, no. 6 (2011): 810–818, 10.1016/j.bcp.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Glaeser J. D., Tawackoli W., Ju D. G., et al., “Optimization of a Rat Lumbar IVD Degeneration Model for Low Back Pain,” JOR Spine 3, no. 2 (2020): e1092, 10.1002/jsp2.1092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Mosley G. E., Wang M., Nasser P., et al., “Males and Females Exhibit Distinct Relationships Between Intervertebral Disc Degeneration and Pain in a Rat Model,” Scientific Reports 10 (2020): 15120, 10.1038/s41598-020-72081-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Xia D., Yan M., Yin X., et al., “A Novel Rat Tail Needle Minimally Invasive Puncture Model Using Three‐Dimensional Printing for Disk Degeneration and Progressive Osteogenesis Research,” Frontiers in Cell and Development Biology 9 (2021): 587399, 10.3389/fcell.2021.587399. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Gansau J., Grossi E., Rodriguez L., et al., “TNFR1‐Mediated Senescence and Lack of TNFR2‐Signaling Limit Human Intervertebral Disc Cell Repair in Back Pain Conditions,” 2024, 10.1101/2024.02.22.581620. bioRxiv. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30. Stauffer W., Sheng H., and Lim H. N., “EzColocalization: An ImageJ Plugin for Visualizing and Measuring Colocalization in Cells and Organisms,” Scientific Reports 8, no. 1 (2018): 15764, 10.1038/s41598-018-33592-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Ding H., Wei J., Zhao Y., Liu Y., Liu L., and Cheng L., “Progranulin Derived Engineered Protein Atsttrin Suppresses TNF‐Alpha‐Mediated Inflammation in Intervertebral Disc Degenerative Disease,” Oncotarget 8, no. 65 (2017): 109692–109702, 10.18632/oncotarget.22766. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Liu K., Wang Z., Liu J., et al., “Atsttrin Regulates Osteoblastogenesis and Osteoclastogenesis Through the TNFR Pathway,” Communications Biology 6, no. 1 (2023): 1251, 10.1038/s42003-023-05635-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Andrade P., Visser‐Vandewalle V., Philippens M., et al., “Tumor Necrosis Factor‐α Levels Correlate With Postoperative Pain Severity in Lumbar Disc Hernia Patients: Opposite Clinical Effects Between Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptor 1 and 2,” Pain 152, no. 11 (2011): 2645–2652, 10.1016/j.pain.2011.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Bachmeier B. E., Nerlich A. G., Weiler C., Paesold G., Jochum M., and Boos N., “Analysis of Tissue Distribution of TNF‐Alpha, TNF‐Alpha‐Receptors, and the Activating TNF‐Alpha‐Converting Enzyme Suggests Activation of the TNF‐Alpha System in the Aging Intervertebral Disc,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1096 (2007): 44–54, 10.1196/annals.1397.069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Phillips K. L., Chiverton N., Michael A. L., et al., “The Cytokine and Chemokine Expression Profile of Nucleus Pulposus Cells: Implications for Degeneration and Regeneration of the Intervertebral Disc,” Arthritis Research and Therapy 15, no. 6 (2013): R213, 10.1186/ar4408. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Lv F., Yang L., Wang J., et al., “Inhibition of TNFR1 Attenuates LPS Induced Apoptosis and Inflammation in Human Nucleus Pulposus Cells by Regulating the NF‐KB and MAPK Signalling Pathway,” Neurochemical Research 46, no. 6 (2021): 1390–1399, 10.1007/s11064-021-03278-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Stover J. D., Trone M. A. R., Weston J., et al., “Therapeutic TNF‐Alpha Delivery After CRISPR Receptor Modulation in the Intervertebral Disc,” 2023, 10.1101/2023.05.31.542947. bioRxiv. [DOI]

- 38. Westacott C. I., Atkins R. M., Dieppe P. A., and Elson C. J., “Tumor Necrosis Factor‐Alpha Receptor Expression on Chondrocytes Isolated From Human Articular Cartilage,” Journal of Rheumatology 21, no. 9 (1994): 1710–1715. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Wei J., Wang K., Hettinghouse A., and Liu C., “Atsttrin Promotes Cartilage Repair Primarily Through TNFR2‐Akt Pathway,” Frontiers in Cell and Development Biology 8 (2020): 577572, 10.3389/fcell.2020.577572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Tartaglia L. A. and Goeddel D. V., “Two TNF Receptors,” Immunology Today 13, no. 5 (1992): 151–153, 10.1016/0167-5699(92)90116-O. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Smith R. A., Kirstein M., Fiers W., and Baglioni C., “Species Specificity of Human and Murine Tumor Necrosis Factor. A Comparative Study of Tumor Necrosis Factor Receptors,” Journal of Biological Chemistry 261, no. 32 (1986): 14871–14874. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zrioual S., Ecochard R., Tournadre A., Lenief V., Cazalis M. A., and Miossec P., “Genome‐Wide Comparison Between IL‐17A‐ and IL‐17F‐Induced Effects in Human Rheumatoid Arthritis Synoviocytes,” Journal of Immunology 182, no. 5 (2009): 3112–3120, 10.4049/jimmunol.0801967. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. McAllister F., Henry A., Kreindler J. L., et al., “Role of IL‐17A, IL‐17F, and the IL‐17 Receptor in Regulating Growth‐Related Oncogene‐Alpha and Granulocyte Colony‐Stimulating Factor in Bronchial Epithelium: Implications for Airway Inflammation in Cystic Fibrosis,” Journal of Immunology 175, no. 1 (2005): 404–412, 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.404. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Rossol M., Meusch U., Pierer M., et al., “Interaction Between Transmembrane TNF and TNFR1/2 Mediates the Activation of Monocytes by Contact With T Cells,” Journal of Immunology 179, no. 6 (2007): 4239–4248, 10.4049/jimmunol.179.6.4239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Walter B. A., Purmessur D., Likhitpanichkul M., et al., “Inflammatory Kinetics and Efficacy of Anti‐Inflammatory Treatments on Human Nucleus Pulposus Cells,” Spine 40, no. 13 (2015): 955–963, 10.1097/BRS.0000000000000932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Silwal P., Nguyen‐Thai A. M., Mohammad H. A., et al., “Cellular Senescence in Intervertebral Disc Aging and Degeneration: Molecular Mechanisms and Potential Therapeutic Opportunities,” Biomolecules 13, no. 4 (2023): 686, 10.3390/biom13040686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Novais E. J., Diekman B. O., Shapiro I. M., and Risbud M. V., “p16(Ink4a) Deletion in Cells of the Intervertebral Disc Affects Their Matrix Homeostasis and Senescence Associated Secretory Phenotype Without Altering Onset of Senescence,” Matrix Biology 82 (2019): 54–70, 10.1016/j.matbio.2019.02.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1. jsp270070‐sup‐0001‐Supinfo.

Table S2. jsp270070‐sup‐0001‐Supinfo.

Figure S1. Positive staining controls in rat brain and bone marrow for TNFR1 (A) and TNFR2 (B) IHC, serum negative control in brain (C).

Figure S2. (A) Example of lumbar spine with IHC staining TNFR2 with Toluidine Blue as a counterstain that was slide scanned. The black box shows a zoomed image from one sham IVD at level L4/5 and annotated for ROI used for quantification. Example of an ROI for AF (red) and NP (green) regions. These ROIs were used for quantification of IHC positivity.

Figure S3. IHC of TNFR2 using monoclonal TNFR2 antibody (ab109322, Abcam) (1:800 dilution) in control (A) and experimental tissue (B, C). No difference in TNFR2 immunopositivity was noted between tissues or injury conditions (C) in agreement with previous TNFR2 IHC (Figure 1). Overall, staining intensity was very faint with this antibody, although the rate of immunopositivity was higher.

Figure S4. H2O2 treated AF cell positive control (A) and negative staining control (B) for Casp3 ICC.

Figure S5. TNFR1 and TNFR2 blocking antibodies had similar effects at 24 and 96 h in both rat AF and NP cells indicating that longer‐duration antibody exposure did increase their efficacy modulating TNFα responses. (Top) Experimental design for 96 h blocking study. Gene expression of (A1, A2) pro‐inflammatory cytokines, (B1, B2) TNFα receptors, (C1, C2) catabolic, and (D1, D2) anabolic extracellular matrix markers in basal and 24 or 96 h antibody conditions for AF (top) and NP (bottom) cells (3 technical replicates; n = 3 biological donors; normalized to Gapdh and basal; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

Figure S6. Atsttrin had similar effects at 24 and 96 h in both rat AF and NP cells. Atsttrin efficacy was not dependent on cell type or culture duration as assessed with qRT‐PCR for (A1, A2) pro‐inflammatory cytokines, (B1, B2) TNFα receptors, (C1, C2) catabolic, and (D1, D2) anabolic extracellular matrix markers in basal and 24 or 96 h antibody conditions for AF (top) and NP (bottom) cells (3 technical replicates; 3 biological donors; normalized to Gapdh and Basal; *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001).

Figure S7. RNA sequencing shows effects of TNFα but not Atsttrin and AF cell transcriptome. (A) PCA shows distinct separation of Basal cells from TNFα and TNFα + Atsttrin treated cells. (B) Differential gene expression analysis showed a large number of significantly different genes between Basal and TNFα treated cells; however, no differentially expressed genes were observed between TNFα and TNFα + Atsttrin treated cells.

Data Availability Statement

All data are available in the main text or the Supporting Information. Data and code for RNA‐seq analysis will be made available upon manuscript acceptance.