ABSTRACT

Background

This study explores nurses’ experiences amid the dual challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic and public mass shootings, highlighting the emotional and professional strains they faced while providing care in crisis situations.

Methods

This qualitative study used semi-structured, in-depth interviews with a sample of 16 nurses caring for patients who were either injured during a public mass shooting or were infected with COVID-19. The participants were selected through purposeful sampling. Thematic analysis was undertaken, and themes derived from structural understanding illuminated nurses’ perceptions of patient care during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Results

Qualitative data analysis revealed five main themes: stressful life events, flashbulb memories, service-oriented mindsets, team collaboration keys, and professional needs. The theoretical interpretation points to multidimensional perceptions of nurses and the need to confirm these perceptions and reconcile them with the psychological impact of stressful life events, making future adjustments and adaptations possible. These results build upon our previous work, first presented as a preprint, which highlighted initial themes and set the foundation for this expanded analysis.

Conclusions

The study underscores how crises impact nurses’ perceptions, highlighting the need for improved support, teamwork, and ongoing training to address their psychological needs during emergencies.

KEYWORDS: Coping, COVID-19, mass shootings, mental health, professional nurse

Background

The coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) is a global public health emergency that started in 2020 (Li et al., 2019). It has affected the global population, especially the mental health, risk perception, and coping strategies of multidisciplinary treatment teams (Kamberi et al., 2021; Kim et al., 2021). Furthermore, in 2020, it was the sixth leading cause of public health emergencies worldwide (World Health Organization, 2020a, 2020b). Stressful life events among nurses are of prime importance as they affect the performance and quality of nursing care.

However, COVID-19 has not been the only global issue recently; illegal gun ownership and violence are also multifaceted public health concerns (Bangkok Post, 2023). In 2019, the United States recorded the highest number of gun-related deaths, with 39,707 fatalities, including homicides, suicides, and accidental deaths. Brazil followed closely with 41,000 gun-related deaths, driven by high rates of violent crime and gang activity. Additionally, Mexico reported 30,700 gun-related deaths, largely due to drug cartel violence.

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) has reported that firearms trafficking affects all parts of the world and is a major concern in the context of human security. Firearms play a significant role in violence, particularly homicides, and are often used by organized criminals and in armed conflicts (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, 2020). The Global Study on Firearms Trafficking 2020 highlighted that small arms and light weapons are the most commonly trafficked firearms, with significant variations in trafficking patterns across different regions (World Population Review, 2025).

In 2019, Thailand recorded 2,351 deaths due to gun violence, which was approximately 31% higher than the number of gun-related deaths in Pakistan. In 2020, there were 48,663 cases of gun-related violence in Thailand, resulting in 1,612 deaths Despite strict laws, illegal gun ownership remains prevalent due to online marketplaces and smuggling from neighbouring countries (Bangkok Post, 2024; FairPlanet, 2022).

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Thailand’s Mental Health Crisis Assessment and Treatment Teams (MCATT) provided care for victims of mass shooting attacks in the community on February 8–9, 2020. This tragic event, known as the Nakhon Ratchasima shootings, involved a soldier from the Royal Thai Army who killed 29 people and injured 58 others. The incident began at the Suratham Phithak Military Camp and continued at the Terminal 21 Korat shopping mall (Department of Mental Health of Thailand, 2022). This event was the deadliest mass shooting in Thailand’s history at the time, resulting in significant physical, mental, and economic impacts on individuals and communities. In addition, a village headman in Nakhon Ratchasima shot a villager to death after the villager complained about requesting COVID-19 relief before the deadline (Manager Online, 2021). Another incident of gun violence occurred at a gambling den, resulting in two serious injuries. Additionally, there was a shooting at a restaurant that caused multiple injuries. In a thrilling escape from death, a former chef broke into a famous shopping mall in Korat and shot a security guard, fearing a repeat of a previous shooting incident (AmarinTV, 2024).

Moreover, in northeast Thailand, an ex-policeman killed at least 37 people, most children, in a gun and knife attack at a childcare centre (Department of Mental Health of Thailand, 2022). In recent events, a 14-year-old boy went on a shooting rampage inside the Siam Paragon shopping mall, killing two people and injuring five others—two of them critically (BBC News, 2023).

Public mass shooting is a specific kind of gun violence, defined by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), as three or more people being killed in a single incident (BBC News, 2022; CNN, 2023) that impacts the daily lives and mental health of people in the community. Another study defined an unpredictable shooting situation as a life-threatening, stressful event that affects life in multiple ways (Blair et al., 2016).

During an epidemic, professional nurses act as critical frontline healthcare workers in hospitals and communities and are often the most vulnerable to stress-related mental illnesses. Furthermore, researchers have shown that they play an essential role in minimizing the public’s fear during critical events and in psychological rehabilitation after the events (Atreya et al., 2022; Bharadwaj et al., 2021; Z. Liu et al., 2020; Sabbath et al., 2018; Sampaio et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2022). Within the context of the COVID-19 pandemic, nurses are the healthcare workers responsible for providing direct and indirect nursing care to people with COVID-19 24 hours a day in hospitals and community settings. Moreover, in Thailand, nurses in locales where public mass shootings occur become responsible for simultaneously assisting people with worries about or being infected with COVID-19 and shooting victims.

In this study, the stress generation theory (Harkness & Washburn, 2016) and the Neuman systems model (Fawcett & Neuman, 2011) were employed to explain the key factors affecting people’s perceptions of stressful life events and how such events affect people differently despite experiencing the same or similar events. This study explored nurses’ perceptions of public mass shooting during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Along with exposure to stressors that nurses are subjected to in their course of duty, research shows that these healthcare professionals are at risk of infections and psychological effects such as stress, anxiety, sleep disturbances, maladjustments, relationship issues, and uncertainty (DiTella et al., 2020; Zhang & Ma, 2020). Furthermore, some empirical studies have shown that the mental health effects of mass shootings at the individual level include psychological distress and clinically significant elevations in posttraumatic stress, depression, and anxiety symptoms, with an increase in the degree of physical exposure and social proximity to the incident (Glasofer & Laskowski-Jones, 2018; Lowe & Galea, 2016; Shultz et al., 2014). Therefore, it is necessary to explore nurses’ perceptions in the era of mass shooting during the COVID-19 pandemic to enhance their well-being and work engagement during crises.

Aim of the study

This study explores nurses’ perceptions of public mass shootings during the COVID-19 pandemic

Theoretical perspective

The theories used in this study were chosen to deepen our understanding of nurses’ perceptions during the era of mass shooting and the COVID-19 pandemic. The Neuman Systems Model (Fawcett & Neuman, 2011) states that the views of a person, family, and community change constantly in response to the environment and stressors.

Hammen’s stress generation theory (Harkness & Washburn, 2016) was apply for this study, this theory proposes that people perceive stressful life events differently despite facing the same event, and that these differences in perception are related to three factors: 1) personality traits—resilience, thought patterns, self-esteem, emotional stability, and perception of social support; 2) personal behaviours—avoidant coping behaviours; and 3) interpersonal relationships—emotional attachment, confidence, and conflict. When a person faces severe life events, their coping skills may not be sufficient to manage the overwhelming nature of these challenges. This can lead to mental health problems and psychiatric disorders. However, these stressors can be alleviated through support, and professionals may need to enhance their mental health strategies to provide effective assistance.

Methods

Design

This was phenomenological-hermeneutic research (Kvale & Brinkmann, 2014) using narrative-based data collection procedures. Narrative-based data collection (Kirkpatrick, 2008) allows researchers to grasp human experience through listening and understanding and contributes to delivering care based on research results.

Setting and participants

Using purposive sampling, nurses working in XYZ Province, Thailand, were selected (Table I). The inclusion criteria were nurses who had experience caring for victims of public mass shootings during the COVID-19 pandemic and were willing to participate in the study. The exclusion criteria included the presence of stress or mental health issues and the inability to provide informed consent. All sixteen nurses who expressed interest and met the primary inclusion criteria were enrolled and completed the study.

Table I.

Demographic of participants (N = 16).

| Demographic data | N (16) | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||

| 25–30 | 1 | 6.25 | |

| 31–40 | 12 | 75 | |

| 41–50 | 3 | 18.75 | |

| Gender | |||

| Female | 14 | 87.5 | |

| Male | 2 | 12.5 | |

| Level Education | |||

| Bachelor degree | 11 | 68.75 | |

| Master degree | 5 | 31.25 | |

| Ward | |||

| OPD | 3 | 18.75 | |

| ER | 3 | 18.75 | |

| IPD | 4 | 25 | |

| Department of psychiatric nursing administration | 1 | 6.25 | |

| Mental health and psychiatric clinic | 1 | 6.25 | |

| Provincial Public Health Office | 4 | 25 | |

| Experience of nursing care | |||

| 5–10 years | 2 | 12.5 | |

| 11–15 years | 4 | 25 | |

| >15 years | 10 | 62.5 | |

Study measures

Demographic questionnaire

The demographic questions covered participant age (as a continuous variable), gender (male, female, transgender), educational attainment (bachelor’s degree, master’s degree), the hospital ward/setting (Emerging Infectious Diseases Ward, Emergency Department, Cohort ward, Outpatient Department, Intensive Care Unit, Operating room, Infection Control Ward, Health centre, Provincial Public Health Office), and nursing care experience (measured by years of direct nursing practice).

Semi-structured interview guideline

The research team developed a semi-structured interview guideline (E. Imkome, 2024), ensuring content validity through verification by three experts and subsequent revisions. The semi-structured interviews were designed using open-ended questions to explore nurses’ personal and professional experiences while providing care during mass shooting events and the COVID-19 pandemic. The interview guide covered topics such as emotional and professional challenges, strategies for coping with stress, collaboration within healthcare teams, and perceived institutional support (Creswell & Zhang, 2009; Goolsby et al., 2022). The guideline included a list of ten questions. Sample interview questions include:

What impacts have the public shooting incident had on you, your families, and your communities (e.g., health, mentality, emotions such as sadness, fear, worry, irritability, daily living such as eating, resting, sleeping, etc.)?

As a nurse, how do you manage the impact of the mass shooting incident at the individual, family, and community levels?

What are some of the problems and obstacles you faced while helping those who were victims of mass shooting attacks?

What are the critical success factors in providing nursing care for public mass shooting victims during the COVID-19 pandemic?

Data collection

Phenomenology was operationalized through dialogue discussions, as they allow the examination and interpretation of nurses’ lived experiences and perceptions in the age of mass shootings and the COVID-19 pandemic (Graor & Knapik, 2013; Kalaldeh et al., 2018; Smith, 2008; Smith & McGannon, 2018; Tong et al., 2007).

Participants were recruited through various approaches, including information given by nurses at the Department of Nursing, displaying posters, using snowball sampling, and purposive sampling. Individuals identified through snowball sampling who met the inclusion criteria were invited to call a dedicated research line to complete a brief eligibility screening conducted by members of the research team. During this call, a team member explained the study’s objectives and requirements while evaluating the participant’s eligibility and interest in joining. For those who qualified and were interested, informed consent was acquired electronically via Google Forms, which were linked in the consent file, email, or Line application. After obtaining the completed consent forms, demographic information (such as age, gender, ward, and nursing care experience) was collected online using Google Forms in October 2020, which took about 1 to 5 minutes.

The female Ph.D. holders acted as qualitative interviewers, and they were faculty members with over twenty years of experience in mental health and psychiatric nursing education, along with training in qualitative research within these areas.

The author contacted nurses in different health settings in Thailand’s XYZ Province to obtain contact details. Prior to the commencement of the study, a rapport was built with the participants. Participants were contacted during their day off to provided research details about the goals, objective, and data collection process. After that, obtain consent before the interview.

The interviews were conducted as semi-structured qualitative sessions through video conferencing, utilizing Microsoft Teams for recording purposes. Only the interviewer and the individual participants were present during the interviews. A total of sixteen participants were interviewed on a one-on-one basis, and the collected interview data were subsequently anonymized. The duration of each interview varied between 30 and 60 minutes, during which the interviewer upheld a professional relationship with the participants. Data confidentiality was ensured through anonymization. Finally, the transcripts were shared with the participants to solicit their comments and/or corrections.

Ethics and consent

Study approved by the Ethics Review Committee for Research Involving Human Research Participants, Thammasat University, Thailand (COA No. 119/2563) in October 2020. The scope, risks, and benefits of the study were thoroughly explained to all participants. Written and verbal consent were obtained from each participant prior to data collection. Participation was voluntary, and measures were taken to ensure anonymity and confidentiality.

The duration of the interviews was determined by the participants’ preferences, patience, and experiences. All interviews were recorded using Microsoft Teams software, and the original video recordings were automatically and permanently deleted from the Microsoft Teams system after one month. Since the completion of the study, transcriptions have been securely stored on the principal investigator’s computer hard drive. After three years, a secure deletion programme called Secure Deletion Shredder will be used to permanently erase these files and folders.

Overall, comprehensive information about the research was provided to all participants, and consent was obtained through both written and verbal means.

Data analysis

Following each interview, a dedicated transcriber produced word-for-word transcripts from the video recordings. These transcripts were then verified for accuracy by two team members. Once finalized and confirmed, the video recordings were discarded. The collected information underwent thematic analysis, a method that identifies, examines, and summarizes patterns or themes within a dataset. The data analysis process involved several specific stages as follows:

Transcription and Review: The initial phase involved transcribing the interviews and thoroughly reviewing the transcripts to ensure accuracy.

Systematic Coding: The second step entailed systematically coding key features across the entire dataset and gathering relevant information for each code.

Theme Development: During the third step, these codes were organized into potential themes, consolidating all relevant data associated with each proposed idea.

Theme Verification: The fourth step focused on verifying that the themes genuinely represented the coded extracts and captured the essence of the entire dataset, thereby creating a thematic “map” of the analysis.

This methodology embraced an iterative approach, continuously refining each theme’s details and establishing clear definitions and terminology. The process culminated in the selection of illustrative examples, a final analysis of the chosen data, and an integration of the findings with the research question and existing literature, ultimately leading to the crafting of a scholarly analysis report (Braun & Clarke, 2006; Polit & Beck, 2012).

The first, second, and third authors independently reviewed raw data transcripts, coded the data, and established categories. Each author developed codes representing significant data, organizing both similar and disparate codes. The researchers formulated categories and themes by examining patterns and combinations of these codes. Any discrepancies encountered were resolved through discussion and consensus. The themes were cross-validated against the codes, and detailed definitions for the themes were established. The themes were further refined to ensure they were precise and the accompanying descriptions accurately represented the data. Key themes were reported alongside relevant quotations, identified by each participant’s I.D. code.

In this study, data saturation was achieved by employing a systematic and iterative approach to both data collection and analysis. It was determined that data saturation had been reached when the researchers identified consistent patterns and themes, indicating that no new information was forthcoming. Interviews continued until a point was reached where further discussions yielded no additional relevant insights or information from participating nurses. The patterns of data were analysed, and themes were scrutinized until no new themes emerged. This indicated that the perspectives pertinent to the research questions had been sufficiently captured (Fusch & Ness, 2015).

Trustworthiness of the study

To enhance the trustworthiness of the data, reflexivity, member checking, peer debriefing, and triangulation were employed (Lincoln & Guba, 1985). Member checking involved returning the interview information to participants to verify the accuracy of the data. Throughout the study, the authors engaged in peer debriefing (Smith et al., 2022), a method that involves receiving critical feedback and considering alternative explanations arising from data collection and analysis, thereby promoting thorough study and analysis during data interpretation (Smith & McGannon, 2018; Tong et al., 2007). The principal investigator (PI) contacted 31 participants via cell phone and invited them to a Microsoft Teams meeting to validate the summary of the findings. This research utilized method triangulation, including in-depth interviews and field notes (Polit & Beck, 2012). The researchers interviewed participants working in various settings such as outpatient clinics, inpatient units, community health centres, and community hospitals. In addition to in-depth interviews, the context provided by field notes from these diverse settings ensured accurate data collection and analysis. The first and second authors reviewed the transcripts, created codes, and identified themes, reaching a consensus on the themes’ conclusions. This process facilitated investigator triangulation.

The research team established a comprehensive audit trail, which included initial notes, detailed step-by-step procedures for enrolment, thorough data collection and analysis, meticulously annotated transcripts, extensive tables of developed themes, all field notes (recorded immediately after each data collection session), and the final report (Groenewald, 2004).

Results

The results are presented in four parts (E.-U. Imkome, 2024):

Part I: Participants’ demographic data and self-understanding

The participants lived in Nakhon Ratchasima Province, Thailand, and aided the victims of public mass shootings during the COVID-19 pandemic. Most were female and had a bachelor’s degree in nursing. More than half of the participants were between 31 and 40 years old and worked in the outpatient departments of psychiatric hospitals. One-fourth worked in inpatient departments of psychiatric hospitals, provincial health offices, emergency departments, and mental health centres (Table I). The self-understanding (Part 1) description was constructed based on all the participants’ perceptions. All participants reported that to work efficiently, they relieved their stress and negative feelings by consulting professionals, setting up ad hoc conferences, spending time with family and loved ones, exercising, and enjoying their favourite foods.

Part II: Structural understanding

The theme shaped by structural understanding highlights the participants’ perceptions of their experiences. This was described through themes such as stressful life events, flashbulb memories, a service-oriented mindset, team

Part III: Themes of the study

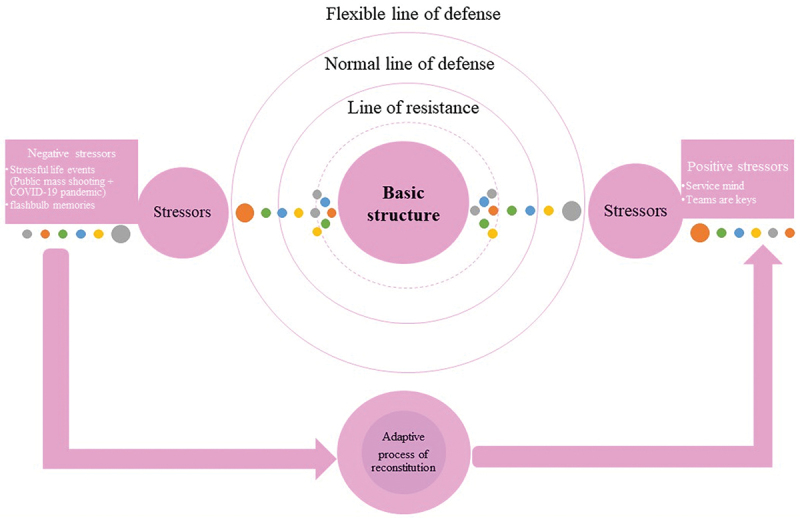

The theme “the double burden of stressful life events among professional nurses: public mass shootings and the COVID-19 pandemic” can be interpreted as follows (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

General themes and the overarching theme based on the structural understanding process.

Theme I: Stressful life events

Professional nurses who dealt firsthand with public mass shootings and COVID-19 faced occupational stress every day and prioritized their duties in the work environment. All participants described the terrifying memory of public mass shooting during COVID-19 as life-threatening, and these events severely impacted their lives. These experiences were like an invasion of their private lives, making them feel anxious, uncertain, out of control, and shocked. The participants provided detailed insight into the Stressful life events as follows:

Occupational stress

The daily stress faced by professional nurses due to their duties in the work environment, particularly during crises like public mass shootings and the COVID-19 pandemic.

During the first few days, when the main team arrived, the senior staff who were the command center set up at Korat Psychiatric Hospital to provide mental support. They established a temporary office in the Terminal 21 zone. As patients started coming in, we had a policy to accept those affected by the shooting incident. I began to feel stressed because I was treating 5–6 patients a day. It felt like I was stuck on every floor. Each person shared their experiences with me, and although I didn’t want to bring up the incident, they probably needed to talk. I ended up listening to everything. The team discussed how exhausted we were. Each victim faced different levels of hardship, with emotions ranging from anger and curses to loss. At that time, I felt very stressed from work. (P2)

I would like to share that even though I am a psychiatric nurse, I sometimes experience stress when listening to the victims’ stories. When we talk, I often feel as if I am there with them, immersed in their experiences. Some patients share their stories in great detail, which makes me feel deeply involved”. (P12)

Terrifying memories

The life-threatening nature of public mass shootings during COVID-19 and the severe impact these events had on the participants’ lives.

When the public mass shootings occurred, no one had experienced anything like this. We did not follow the news on the Line or Facebook applications. I went to the mall, where the accident scene was unbelievable. I remained calm and kept walking. By the time I came out of the mall, the police had closed the road leading to the hospital. Everyone was holding their phones and following Facebook Live. (P1)

Invasion of private lives

The feeling of anxiety, uncertainty, loss of control, and shock experienced by nurses as these events intruded into their personal lives. The participants state that

The incident made us feel very scared, anxious and uneasy. (P5)

Even though I am a nurse, I couldn’t sleep the first night after the shooting incident because I was still in shock. It felt like the event was constantly replaying in my mind. (P9)

Unexpected events

The sudden occurrence of public mass shootings and the severe stress it caused among the participants. Some excerpts exemplify these feelings.

Reflecting on the mass shooting events, I wondered why such a violent incident happened so easily. I had never encountered anything like it before. Why did it happen? Why did so many people die so easily at a time when such an incident shouldn’t have occurred? I couldn’t understand it. (P7)

“The public mass shootings happened suddenly. I did not expect this to happen, which made us experience severe stress”. (P12)

I have never encountered this situation before. It is very stressful and alarming. (N 16)

Theme II: Flashbulb memories

Participants in the present study described experiencing paradoxical feelings: longing for relationships and expecting rejection by others. The future seemed to be both fearful and filled with expectations. The participants revealed that they could not forget mass shooting during the COVID-19 pandemic and continuously thought about it. The following excerpts illustrate these remarks:

Paradoxical feelings

Participants experience conflicting emotions, such as Strength versus Vulnerability. Nurses are expected to be strong and resilient in crisis situations, yet they may feel vulnerable and affected by the traumatic events they witness.

It feels terrible and sad. It shouldn’t have happened. There are more victims than we initially thought when we first heard about it on the news. As we hear that the situation is escalating, we feel even worse. (N10)

Emotional impact

The incident evokes strong feelings of fear, sadness, helplessness, and depression, which are difficult to forget.

There is still a thought that arises in my memory. Whenever I pass or go there, where we have experienced a public mass shooting, I feel uncomfortable. I live in fear. It will flash into my memory. (P2)

I feel like I constantly remind myself of that situation of fear, sadness, terrible helplessness, and depression. It is a moment that I cannot forget. (P13)

Theme III: Service-oriented mindset

The service-oriented mindset theme refers to reports from professional nurses about their voluntary and unconditional regard for helping mass-shoot victims during the COVID-19 pandemic. Some excerpts exemplify this mindset (information within square brackets is only for clarification):

Voluntary and unconditional care

Nurses demonstrate a voluntary and unconditional commitment to helping mass shooting victims.

I am the head of the MCATT team at the hospital. I left all my hospital work to focus on healing my mind. My family was greatly affected because I had to be on the team from morning until 10 pm every day. If you ask anyone at the hospital, they will say it’s hospital work. Everyone, even those who don’t directly take care of patients, comes together to help. We eat and sleep at the hospital, sharing every meal—breakfast, lunch, and dinner. There is a support team that serves food. We divide into teams according to the EOC plan, including a stack team, an operator team, and many others. Everyone does their best. (N4)

Comprehensive nursing care

This includes simultaneous assessment, relationship-building, emotional support, and physical care.

Since the victims are referred to the ER, it [the nursing care] began with the simultaneous assessment and relationship-building process. The victims were asked [if they wanted] to express their feelings, be listened to, and be touched. It [the nursing care] made them feel that they were not alone or fearful. They are then told that the situation is under control. There is a way to feel calm, and relaxation techniques are taught. After the doctor prescribes the injection, nurses give injections and monitor the victims. (P12)

Therapeutic interventions

Implementation of cognitive behavioural therapy for depression and suicide prevention protocols for those experiencing suicidal thoughts.

Cognitive behavioral therapy will be provided if the victim has depression, and the condition needs to be managed. Suicide prevention protocols need to be implemented for victims who experience suicidal thoughts. (P1, P2)

We build rapport by giving them an opportunity to talk or vent their feelings. We use the silence of the room to listen to them. After they express their feelings, we touch them, making them feel that they are not alone or scared. We reassure them that the situation has calmed down and teach them relaxation techniques. (P4)

Theme IV: Team collaboration is key

Collaboration is crucial for helping victims of mass shooting during the COVID-19 pandemic. As critical COVID-19 patient care team members, participating nurses were reportedly exposed to most COVID-19-related challenges and those caused by mass public shooting events. Most participants provided statements resembling the following:

Multidisciplinary approach

Collaboration among various healthcare professionals, including nurses, psychiatrists, psychologists, and social workers, to provide comprehensive care.

About a week after the incident, we had a Mental Health Crisis Assessment and Treatment Team (MCATT) provide care for people in the community to relieve their stress. (P2)

The care team in a mass shooting includes nurses, doctors, psychologists, pharmacists, psychiatrists, nutritionists, and social workers. (P4, P12)

A student who survived a shooting was taken to the emergency room. He exhibited screaming behavior, which was addressed by a team of psychiatrists and nurses. They assessed his symptoms to provide initial care, alongside the doctors treating his physical injuries. (P12)

Psychosocial interventions and follow-up care.

Implementation of group activities, counselling, psychoeducation, and medication monitoring to support victims. Regular follow-up processes, including bi-weekly reports and community visits every three months, to ensure ongoing support and care.

We work as a team; we screen mental states, and a case of suicide was referred to a psychiatrist as per the guidelines. A psychiatrist will prescribe psychiatric drugs if a case is in emergency psychiatry. If a person had suicidal thoughts, we would deliberate with the multidisciplinary treatment teams. The psychologists approached the cases with severe stress. The psychosocial interventions were performed through group activities, counseling, psychoeducation, and monitoring medication adherence. After that, the follow-up process will be implemented, reported every two weeks, and followed up in the community every three months. Cases of financial problems were referred to the social workers. (P13)

Theme V: Professional needs

To promote positive nursing outcomes in stressful situations during the COVID-19 pandemic, participants expressed that they needed support from their studies, professional skills, budgets and resources, and emotional support. Professional needs were also a concern, and participants provided statements that resembled the following.

Specialized teams

The need for specialized teams, including child psychiatrists and lawyers, to handle victims from admission to rehabilitation.

There should be a specialized team to take care of the victim from the stage of being admitted discharging and rehabilitation in the community. Especially, child psychiatrists and lawyers need to be consulted”. (P4)

Training and preparation

The importance of training and preparing healthcare professionals to provide effective crisis services.

We need the training to prepare a good service for the victims of a crisis, and if we can call on these volunteer groups to help us [with this training], that would be great. (P5)

Medical histories and data

The benefit of having victims’ medical histories and data to create effective care plans.

The victims are high-risk patients. It would be better if we had these victims’ medical histories and data to [provide a] good care plan for them in the future. Additionally, policies should be developed and can prevent this [type of] crisis in the future. (P12)

Efficient tools

The requirement for simple and brief tools for mental health assessment to work more efficiently and help more victims quickly.

The situation will be under control; it would be better if we have ideas, guidelines, and equipment prepared in advance to deal with public mass shootings during the COVID-19 pandemic. (P7)

There are various online technologies for [conducting] mental health assessment. However, if we have a simple and brief tool, it will help us work efficiently and help more victims more quickly. (P13)

Part IV: Theoretical interpretation

On examining the overarching themes underpinning the structural analysis, we observed that participants experienced stressful life events, flashbulb memories, a service-oriented mindset, team collaboration as key, and professional needs, which can be further illuminated using the Neuman Systems Model (Zhu et al., 2022). Furthermore, based on this model, stressful life events and flashbulb memories experienced by participants can be attributed to stress. In addition, the stress generation hypothesis (CNN, 2023) proposes a cyclical conception of interpersonal stress, wherein internalizing symptoms and behaviour mediates the relationship between previous and ulterior interpersonal stress.

The Neuman Systems Model presents an individual as an open system that interacts with the internal and external environments to balance disruptive factors (Zhu et al., 2022). An individual can be positively or negatively affected by stressors depending on their ability to cope with stress. Participants perceived that they experienced double the burden of stressful life events that occurred in the community, as they had to care for patients with both mass shooting and the COVID-19 pandemic. Their perceptions of negative stressors led us to include the themes of stressful life events and flashbulb memories in the results section. After the mass shootings, they found a way to turn the stress they experienced into a service-oriented mindset and a desire for collaboration to comprehensively identify positive stressors. When stressors impact a system and are evaluated positively, stress guides people towards the desired adaptation process (Graor & Knapik, 2013; Zhu et al., 2022). Indeed, study participants made positive changes to help themselves cope with stressors better while adapting to the aftermath of mass shootings. The main factor in their adaptation process is to help themselves cope with the double burden of stressful life events in a short time and to provide care for others.

In conclusion, the theoretical interpretation of nurses’ perceptions showed that participants experienced the double burden of stressful life events while providing care to patients related to mass shooting and the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonetheless, they also talked about their existential perceptions during the interviews, evoking questions about work and the future of nursing care during crises. Additionally, their experiences of stressful life events, flashbulb memories, capability to have a service-oriented mindset, and collaboration among team members worsened due to a lack of support from the organizations that employed them and the nursing councils. These institutions reportedly did not make much effort to support them in gaining the skills, experience, and knowledge to fight crises in the future.

Discussion

This study explored nurses’ perceptions in the era of mass shooting and the COVID-19 pandemic. It illuminates the multifaceted nature of nurses’ perceptions and the importance of nurses caring for people in such critical situations to achieve a new equilibrium in the aftermath of these crises. The main themes were “stressful life events,” “flashbulb memories,” “service-oriented mindset,” “team collaboration is key,” and “professional needs.” The Neuman Systems Model and Hammen’s Stress Generation Theory were used to interpret the stress nurses experienced and describe their perceptions about delivering care to victims of mass shooting and the COVID-19 pandemic in XXX. This theoretical interpretation is integrated into the broader discussion to provide a comprehensive understanding of the findings.”

Stressful life events

The participants endured several stressful life events due to their duty to provide nursing services, such as helping victims of public mass shootings and experiencing their losses, insufficient equipment and materials to deliver proper care, and a lack of knowledge. Professional nurses in the study sample reported that when called out to care for those injured in a public mass shooting, they felt terrified, appalled, and unable to control the situation. These findings are consistent with those reported in studies by Bharadwaj et al. (2021), Lu et al. (2021), and Sarani et al. (2021), which described how survivors of shooting events experience shock, uncertainty, overcontrol, and aggressive behaviours (Bharadwaj et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2021; Sarani et al., 2021). Furthermore, one study reported that these events lead to mental health problems and psychiatric disorders (Sarani et al., 2021). The participants in this study reported dealing with these stressful events through social support using a combination of methods that included gardening, spending time with family members, watching movies and series, reducing media consumption, and stress-relieving techniques (e.g., breathing exercises, self-consciousness, and exercise). Additionally, the participants showed negative coping strategies that might provide temporary relief from stress but can ultimately be harmful or counterproductive. These include: a) Excessive Exercise: Some participants engaged in excessive exercise to forget the terrifying memories of mass shooting events, b) Binge-Watching Movies or Series: Some participants binge-watched movies or series for extended periods, especially late into the night, which can disrupt sleep patterns and lead to fatigue, and c) Excessive Phone Use: Some participants used their phones all day to talk with significant others, which can lead to skipping meals and late. This behaviour aligns with the study by Smith et al. (2023), which found that individuals often resort to maladaptive coping mechanisms in response to traumatic events.

Researchers have remarked that the COVID-19 pandemic and crisis events have exposed nurses to higher levels of occupational stress and anxiety (Johnson et al., 2022; B. Smith et al., 2022). Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic has been shown to put tremendous psychological pressure on nurses, increasing their anxiety, suicide rates, fear, and depression. One of the major concerns in this regard is the impact of the stress caused by COVID-19 on nurses’ quality of life (Brown et al., 2023; Davis et al., 2023; Taylor & Wilson, 2024; Williams et al., 2023; Wilson et al., 2024).

These findings support the stress generation theory and the existence of critical factors differentiating a person’s perception of stressful life events, including cognitive thinking patterns, cognitive styles, self-esteem, anxiety level, and coping (Bharadwaj et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2021). Furthermore, research has shown that mental preparedness and a responsible professional attitude are essential characteristics for minimizing stress levels among nurses (Smith et al., 2022).

The personal experiences of nurses with crises significantly influenced their professional roles. The exposure to traumatic events, such as public mass shootings, not only heightened their emotional responses but also impacted their ability to perform their duties effectively. The fear and helplessness reported by nurses during these crises underscore the need for better training and support systems to prepare them for such situations (Bharadwaj et al., 2021; Lu et al., 2021; Sarani et al., 2021)

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic has exacerbated the stress levels among nurses, leading to severe psychological impacts. The increased anxiety, fear, and depression among nurses during the pandemic highlight the urgent need for mental health support and interventions to help them cope with the pressures of their profession (Brown et al., 2023; Davis et al., 2023; Johnson et al., 2022; Smith et al., 2022; Taylor & Wilson, 2024; Williams et al., 2023; Wilson et al., 2024).

These experiences have also emphasized the importance of social support and coping mechanisms. Nurses who engaged in activities such as gardening, spending time with family, and practicing stress-relief techniques reported better mental health outcomes. This suggests that fostering a supportive environment and encouraging self-care practices can play a crucial role in mitigating the negative effects of occupational stress (Bharadwaj et al., 2021; Liu et al., 2020).

Flashbulb memories

Nurses are at the core of healthcare delivery, and their contribution was—and continues to be—key in dealing with Thailand’s mass shooting and COVID-19 crises. Nonetheless, and unfortunately, when nurses in the study sample thought and talked about the double burden they experienced from these events, they reported high levels of negative feelings; they remarked that they constantly thought about the incident. This is consistent with past research (Erin & Tekın, 2022). Furthermore, they reportedly experience shock due to stressful events. Indeed, researchers have shown that some people who have witnessed these events may develop aggressive behaviours, which then lead to mental health problems and psychiatric disorders within the context of mass shooting (Ashikur, 2022; Coffré & De Los Ángeles Leví Aguirre, 2020; Cui et al., 2021; DeLong, 2021; Erin & Tekın, 2022; Hu et al., 2020; G. Liu & Zhang, 2020; Liu et al., 2020; Santana et al., 2020; Taylor & Wilson, 2024; Vizheh et al., 2020; White, 2021; Wilson et al., 2024). To tackle these problems in the aftermath of such public crises, one study suggested that people need support to cope with the unavoidable negative emotions they will experience concerning the event (Dabou et al., 2022).

Service-oriented mindset

The analyses also showed that participants considered their professional practice to be a significant factor in managing the COVID-19 outbreak. Researchers have remarked that COVID-19 is a global emergency and that nurses must retain their commitment as professionals to tackle the crisis (Silver et al., 2020). In the study sample, nurses offered unconditional positive support and holistic physical, mental, emotional, social, and spiritual care to victims of mass shooting during the COVID-19 pandemic and to COVID-19 patients. This is concordant with past research demonstrating that although nurses experienced a stressful life event during the COVID-19 pandemic, they still endeavoured to deliver the best care possible and managed the outbreak valiantly (Hu et al., 2020).

Team collaboration is key

The participants described their service as a teamwork system, where teams are key to helping victims of mass shootings heal and return to everyday life. Within teams, social support is often a critical source of stress relief. In past research, multidisciplinary treatment teams showed concern for team members and provided information, knowledge, and emotional support through shared responsibilities (Rosenberg, 2014). This strategy helped to assuage the emotional consequences of work-related stress in past research (Nagin et al., 2020) and improved the quality of nursing outcomes.

Professional needs

Participants reported that their professional needs included academic support, training in vocational skills, more significant budgets, and resources to promote positive nursing care outcomes when dealing with patients from mass shooting during the COVID-19 outbreak. In addition, COVID-19-related anxiety is an essential factor that an organization should consider addressing their anxiety and negative emotions to ensure more efficient work (Nagin et al., 2020). Furthermore, in Maslow’s hierarchy of needs, the lowest and most basic human needs are physiological, such as sleep. However, nurses in the sample reportedly had no time to rest and relax because of their excessive workload and duties. Furthermore, more budget and training policies for multidisciplinary treatment teams, team responses, and volunteers are needed, as corroborated by prior research (Chirico et al., 2021; González-Guarda et al., 2018; McCall, 2020). Nurses in the study sample also expressed the need for online mental health assessment tools and technology, specific room facilities, and a specialist team to deal with the mental health disorders evoked by mass shooting crises. These disorders include post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), major depression, anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders (Abrams, 2023; Ogasa, 2022).

Furthermore, a prior study conducted by Chirico et al. (2021). described that the following are among the measures that managers of healthcare organizations can currently implement to reduce work anxiety: improving management methods in the nursing system for dealing with patients with mass shootings and COVID-19, proper communication with nurses, proper provision of support for them, creating a suitable environment for nurses to continue their professional activities, establishing effective incentives to ensure nurses’ work motivation, changing the management of nurses’ working hours, and teaching coping methods.

Additionally, nurses in the sample described that providing full support to victims, the therapy team, and an ad hoc conferencing system to relieve stress and/or manage the therapist’s mood were ways to promote nurses’ health and ensure optimal nursing care. This is consistent with a study conducted by Vizheh et al. (2020) with nurses who had been prepared to help victims of a shooting incident, the results of which showed that these nurses felt that preparation, planning, and skills in nursing were essential for their nursing care delivery as well as using coping mechanisms appropriately. Moreover, nurses should be ready to be a part of the solution and work with multidisciplinary teams to shape policies at the federal level and help prevent such tragedies from occurring.

Part IV: Theoretical interpretation

Upon examining the overarching themes underpinning the structural analysis, the participants experienced stressful life events, flashbulb memories, a service-oriented mindset, team collaboration as key, and professional needs. These themes can be further illuminated using the Neuman Systems Model (Fawcett & Neuman, 2011). According to this model, stressful life events and flashbulb memories experienced by participants can be understood as significant stressors. Additionally,

The stress generation hypothesis (Harkness & Washburn, 2016) proposes a cyclical conception of interpersonal stress, wherein internalizing symptoms and behaviours mediate the relationship between previous and subsequent exterior interpersonal stress.

The Neuman Systems Model presents an individual as an open system that interacts with internal and external environments to balance disruptive factors (Fawcett & Neuman, 2011). An individual can be positively or negatively affected by stressors depending on their ability to cope with stress. Participants perceived that they experienced a double burden of stressful life events occurring in the community, as they had to care for patients affected by both mass shootings and the COVID-19 pandemic. Their perceptions of negative stressors led us to include the themes of stressful life events and flashbulb memories in the results section. After the mass shootings, participants found a way to transform the stress they experienced into a service-oriented mindset and a desire for collaboration to comprehensively identify positive stressors. When stressors impact a system and are evaluated positively, stress guides individuals towards the desired adaptation process (Fawcett & Neuman, 2011; Sarani et al., 2021). Indeed, study participants made positive changes to help themselves cope better with stressors while adapting to the aftermath of mass shootings. The main factor in their adaptation process was their ability to manage the double burden of stressful life events in a short time and provide care for others.

In conclusion, the theoretical interpretation of nurses’ perceptions showed that participants experienced the double burden of stressful life events while providing care to patients affected by mass shootings and the COVID-19 pandemic. Nonetheless, they also discussed their existential perceptions during the interviews, raising questions about work and the future of nursing care during crises. Additionally, their experiences of stressful life events, flashbulb memories, capability to maintain a service-oriented mindset, and collaboration among team members were exacerbated by a lack of support from their employing organizations and nursing councils. These institutions reportedly did not make sufficient efforts to support them in gaining the skills, experience, and knowledge needed to address future crises.

Limitations

One notable limitation of this study is the reliance on qualitative interviews. While these interviews provide rich detail, they are subject to individual biases and may not fully capture the diverse experiences of all nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic and public mass shootings. Additionally, the study was conducted in a specific geographic area, which may not accurately reflect the experiences of nurses in different regions or healthcare settings. Future research with a more diverse sample is needed for a comprehensive understanding of this issue.

Furthermore, the exclusion of Registered Nurses (RNs) with stress-related mental health issues may have resulted in the omission of a particularly vulnerable population. This exclusion could have led to results that show less distress than if this group had been included. Additionally, it is important to note that the psychiatric RNs in this study may not have dealt extensively with comorbid infectious diseases, especially since 75% of them were outpatient psychiatric nurses. Acknowledging these limitations is important for understanding the scope and applicability of the study’s findings.

Conclusions

The findings of this study suggest that enhancing the quality of care provided by professional nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic and in the aftermath of mass shootings may benefit from improving their sleep quality and promoting positive emotions related to their work. Additionally, it is important to address and alleviate work-related stress.

The study indicates that nurses experience significant stress when faced with additional challenging events, such as the COVID-19 pandemic or mass shootings. These stressors lead to vivid recollections and heightened stress levels while caring for affected patients. Despite these challenges, nurses demonstrated a service-oriented mindset and articulated their professional needs, which could be seen as positive coping strategies to manage the associated stress. This mindset allowed them to maintain high standards of nursing care even in difficult circumstances.

By addressing the broader issue of how nurses cope with increased stress during such events, the study provides valuable insights that can be applied to improve nursing care in various high-stress situations. Implementing strategies to improve sleep quality, promote positive emotions, and provide mental health support can help nurses manage stress and maintain high-quality care.

Recommendations

Policy implications

Rapidly establishing an integrated command to tackle mass shooting can help control acute situations, and cross-disciplinary treatment teams and training, such as active attack integrated response, can be deployed nationwide. This training can provide nurses with tools to work more efficiently and perform essential life-saving medical interventions that may keep victims alive enough to obtain definitive care.

Furthermore, to ensure that nurses deliver quality nursing care services, primary needs, such as sleep, salary, appropriate workload, and ways to improve life satisfaction should be provided, and nurses should have good work conditions.

Nursing education

Advanced knowledge, practical skills, and new technologies are needed to address mass shooting and public crises. Therefore, organizations involved in nurses’ education should integrate advanced nursing crisis care and the latest technology into the curriculum at the master’s degree, Ph.D., and postgraduate levels.

Nursing research

This study provides basic knowledge about nurses’ perceptions of caring for patients of mass shootings during the pandemic and patients related to the COVID-19 pandemic. Thus, the factors associated with coping or resilience must be studied, along with best practices and interventions for this population.

Future research should continue to explore the impact of additional stressors on nurses and identify effective interventions to support their well-being. By doing so, we can ensure that nurses are better equipped to handle the demands of their profession and continue to provide exceptional care, even in the face of extraordinary challenges.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by the Thammasat University Research Unit in the Innovation of Mental Health and Behavioral Healthcare, and funded by the Faculty of Nursing, Thammasat University.

Ek-uma Imkome: Proposal development, conceptualization, funding acquisition, methodology, project administration, supervision, writing, reviewing, and editing manuscripts.

Biography

Ek-Uma Imkome is a Principal Researcher at the Department of Mental Health and Psychiatric Nursing, Faculty of Nursing, Thammasat University, Thailand. She specializes in nursing care for clients with comorbid substance use and psychiatric disorders, as well as support for clients and caregivers affected by schizophrenia. Her work includes developing assessment instruments for the mental health spectrum, addressing stress from events like COVID-19, and conducting SWOT analyses to inform mental health strategies. Ek-Uma is also involved in developing artificial intelligence tools to enhance mental health promotion and outcomes.

Funding Statement

This study was funded by the Faculty of Nursing, Thammasat University Contract No. 4/2563, and the Thammasat University Research Unit in the Innovation of Mental Health and Behavioral Healthcare.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available at Figshare: The double burden of stressful life events among professional nurses: public mass shootings and the COVID-19 pandemic https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19732405.v2 (E. Imkome, 2022)

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Study approved by the Ethics Review Committee for Research Involving Human Research Participants, Thammasat University, Thailand (COA No. 119/2563). Research information was provided to all participants, and consent was obtained in written and verbal forms.

Highlights

Impact of Dual Crises: The study highlights the compounded challenges faced by nurses caring for patients affected by both public mass shootings and COVID-19. It illustrates the unique psychological and emotional stressors associated with this dual burden.

Importance of Team Collaboration: Participants stressed the importance of teamwork and collaboration in delivering effective patient care during crises. They indicated that strong support networks are crucial for fostering resilience among nursing professionals.

Need for Professional Support: The findings underscore a critical need for enhanced training and mental health resources for nurses. This highlights the need for targeted support initiatives to equip healthcare providers to better manage crises in their work environment.

Supplementary material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed online at https://doi.org/10.1080/17482631.2025.2504477

References

- Abrams, Z. (2023). Stress of mass shootings causing cascade of collective traumas. Monitor on Psychology, 53(6), 20. https://www.apa.org/monitor/2022/09/news-mass-shootings-collective-traumas [Google Scholar]

- AmarinTV . (2024). Escape from death in a thrilling manner! Former chef breaks in and shoots security guard in front of famous shopping mall in Korat, fearing a repeat of the shooting incident [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NCjHjNZ9pNs

- Ashikur, R. (2022). A scoping review of COVID-19-related stress coping resources among nurses. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 9(2), 259–15. 10.1016/j.ijnss.2022.02.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Atreya, A., Nepal, S., Menezes, R. G., Shurjeel, Q., Qazi, S., Ram, M. D., Usman, M. S., Ghimire, S., Marhatta, A., Islam, M. N., Sapkota, A. D., & Garbuja, C. K. (2022). Assessment of fear, anxiety, obsession and functional impairment due to COVID-19 amongst health-care workers and trainees: A cross-sectional study in Nepal. F1000research, 11, 119. 10.12688/f1000research.76032.2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bangkok Post . 3 arrested for supplying gunman. Retrieved November 10, 2023, from https://www.bangkokpost.com/thailand/general/2659668/3-arrested-for-supplying-gunman

- Bangkok Post . (2024, February 20). Time for gun limits. https://www.bangkokpost.com/opinion/opinion/2745061/time-for-gun-limits

- BBC News . (2022). Thailand: Many children among dead in nursery attack. Retrieved August 10, 2023, from https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-63155169

- BBC News . (2023). Two dead and 14-year-old held over Siam Paragon mall shooting. BBC News. https://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-66994274 [Google Scholar]

- Bharadwaj, P., Bhuller, M., Løken, K. V., & Wentzel, M. (2021). Surviving a mass shooting. The Journal, 201, 104469. 10.1016/j.jpubeco.2021.104469 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Blair, J. P., Nichols, T., Burns, D. J., & Curnutt, J. R. (2016). Active Shooter Events and Response. 10.1201/b14996 [DOI]

- Braun, V., Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brown, A., Smith, B., & Davis, C. (2023). The impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of nurses: A comprehensive review. Journal of Nursing Research, 30(2), 123–135. 10.1016/j.jnurres.2023.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chirico, F., Nucera, G., & Magnavita, N. (2021). Protecting the mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 emergency. BJPsych International, 18(1). 10.1192/bji.2020.39 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- CNN . (2023). 14-year-old boy arrested after deadly Thai shopping mall shooting. Retrieved November 5, 2023, from https://edition.cnn.com/2023/10/03/asia/thailand-central-bangkok-shopping-mall-shooting-intl/index.html

- Coffré, J. A. F., & De Los Ángeles Leví Aguirre, P. (2020). Feelings, stress, and adaptation strategies of nurses against COVID-19 in Guayaquil. Investigación y Educación en Enfermería. 38(3), e07. 10.17533/udea.iee.v38n3e07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Creswell, J. W., & Zhang, W. (2009). The application of mixed methods designs to trauma research. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 22(6), 612–621. 10.1002/jts.20479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cui, S., Jiang, Y., Shi, Q., Zhang, L., Kong, D., Qian, M., & Chu, J. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 on anxiety, stress, and coping styles in nurses in emergency departments and fever clinics: A cross-sectional survey. Risk Management Health, 14, 585–594. 10.2147/rmhp.s289782 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabou, E. A. R., Ilesanmi, R. E., Mathias, C. A., & Hanson, V. F. (2022). Work-related stress management behaviors of nurses during COVID-19 pandemic in the United Arab Emirates. SAGE Open Nursing, 8. 10.1177/23779608221084972 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L., Williams, M., Thompson, R., Secginli, S., Bahar, Z., Jans, C., Nahcivan, N., Torun, G., Lapkin, S., & Green, H. (2023). Predicting behavioural intentions towards medication safety among student and new graduate nurses across four countries. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 32(5–6), 789–798. 10.1111/jocn.16330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLong, D. M. (2021). Another two mass shootings: Déjà vu all over again. Annals of Internal Medicine, 174(6), 862–863. 10.7326/m21-1505 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Department of Mental Health of Thailand . (2022). The department of mental health revealed that 108 people were affected from the shooting in Korat. The most stressful; expected to affect the mind in the long term. Retrieved June 10, 2023, from https://www.dmh.go.th/news-dmh/view.asp?id=30191

- DiTella, M., Romeo, A., Benfante, A., & Castelli, L. (2020). Mental health of healthcare workers during the COVID-19 pandemic in Italy. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 26(6), 1583–1587. 10.1111/jep.13444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erin, R., & Tekın, Y. B. (2022). Psychosocial outcomes of COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers in maternity services. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics & Gynecology, 43(3), 327–333. 10.1080/0167482x.2021.1940944 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FairPlanet . (2022, August 24). Thailand’s gun violence casts doubts on outdated laws. https://www.fairplanet.org/editors-pick/thailands-gun-violence-casts-doubt-on-outdated-laws/

- Fawcett, J., & Neuman, B. (2011). The Neuman systems model. Pearson Higher Ed. [Google Scholar]

- Fusch, P. I., & Ness, L. R. (2015). Are we there yet? Data saturation in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 20(9), 1408–1416. https://www.nsuworks.nova.edu/tqr/vol20/iss9/3 [Google Scholar]

- Glasofer, A., & Laskowski-Jones, L. (2018). Mass shootings. Nursing, 48(12), 50–55. 10.1097/01.nurse.0000549496.58492.26 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- González-Guarda, R. M., Dowdell, E. B., Marino, M. A., Anderson, J., & Laughon, K. (2018). American Academy of nursing on policy: Recommendations in response to mass shootings. Nursing Outlook, 66(3), 333–336. 10.1016/j.outlook.2018.04.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goolsby, C., Schuler K., Krohmer J., Gerstner D. N., Weber N. W., Slattery D. E., Kuhls D. A., & Kirsch T. D. (2022). Recommendations for healthcare response to mass shootings. Journal of the American College of Surgeons, 235(1), 123–130. 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2022.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Graor, C. H., & Knapik, G. P. (2013). Addressing methodological and ethical challenges of qualitative health research on persons with schizophrenia and bipolar disorder. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 27(2), 65–71. 10.1016/j.apnu.2012.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groenewald, T. (2004). A phenomenological research design illustrated. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 3(1), 42–55. 10.1177/160940690400300104 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Harkness, K. L., & Washburn, D. (2016). Stress generation. In Fink G. (Ed.), Stress: Concepts, cognition, emotion, and behavior (pp. 331–338). Elsevier Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, D., Kong, Y., Li, W., Han, Q., Zhang, X., Zhu, L., Wan, S. W., Liu, Z., Shen, Q., Yang, J., He, H.-G., & Zhu, J. (2020). Frontline nurses’ burnout, anxiety, depression, and fear statuses and their associated factors during the COVID-19 outbreak in Wuhan, China: A large-scale cross-sectional study. EClinicalMedicine, 24, 100424. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2020.100424 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imkome, E. (2022). The double burden of stressful life events among professional nurses: Public mass shootings during the COVID-19 pandemic. Figshare. 10.6084/m9.figshare.19732405.v2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imkome, E. (2024). Semi-structured interview questions (Nurse). Figshare. 10.6084/m9.figshare.25026269.v1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Imkome, E.-U. (2024). The double burden of stressful life events among professional nurses: Public mass shootings during the COVID-19 pandemic, 25 January 2024, PREPRINT (version 1) available at research square. 10.21203/rs.3.rs-3882835/v1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Johnson, L., Williams, M., & Thompson, R. (2022). Occupational stress and anxiety among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 58(3), 456–467. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2022.02.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kalaldeh, M. A., Shosha, G. A., Saiah, N., & Salameh, O. (2018). Dimensions of phenomenology in exploring Patient’s suffering in long-life illnesses. Journal of Patient Experience, 5(1), 43–49. 10.1177/2374373517723314 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kamberi, F., Sinaj, E., Jaho, J., Subashi, B., Sinanaj, G., Jaupaj, K., Stramarko, Y., Arapi, P., Dine, L., Gurguri, A., Xhindoli, J., Bucaj, J., Serjanaj, L. A., Marzo, R. R., & Nu Htay, M. N. (2021). Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on mental health, risk perception and coping strategies among health care workers in Albania - evidence that needs attention. Clinical Epidemiology and Global Health, 12, 100824. 10.1016/j.cegh.2021.100824 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim, S. C., Quiban, C., Sloan, C., & Montejano, A. S. (2021). Predictors of poor mental health among nurses during COVID-19 pandemic. Nursing Open, 8(2), 900–907. 10.1002/nop2.697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkpatrick, H. (2008). A narrative framework for understanding experiences of people with severe mental illnesses. Archives of Psychiatric Nursing, 22(2), 61–68. 10.1016/j.apnu.2007.12.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kvale, S., & Brinkmann, S. (2014). Interviews: Learning the craft of qualitative research interviewing. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X., Luk, H., Lau, S., & Woo, P. C. Y. (2019). Human coronavirus: General features. Biomedical Science. 10.1016/B978-0-12-801238-3.95704.0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lincoln, Y. S., & Guba, E. G. (1985). Naturalistic inquiry. Sage Publications. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, G., & Zhang, H. (2020). A study on burnout of nurses in the period of COVID-19. Journal of Psychology and the Behavioral Sciences, 9(3), 31–6. 10.11648/j.pbs.20200903.12 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z., Han, B., Jiang, R., Huang, Y., Ma, C., Wen, J., Zhang, T., Wang, Y., Chen, H., & Ma, Y. (2020). Mental health status of doctors and nurses during COVID-19 epidemic in China. Social Science Research Network. 10.2139/ssrn.3551329 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lowe, S. R., & Galea, S. (2016). The mental health consequences of mass shootings. Trauma, Violence & Abuse, 18(1), 62–82. 10.1177/1524838015591572 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X., Astur, R. S., & Gifford, T. (2021). Effects of gunfire location information and guidance on improving survival in virtual mass shooting events. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 64, 102505. 10.1016/j.ijdrr.2021.102505 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Manager Online . (2021, August 21). Village headman shoots villager to death after complaint about COVID-19 relief. https://mgronline.com/local/detail/9640000080284

- McCall, W. T. (2020). Caring for patients from a school shooting: A qualitative case series in emergency nursing. Journal of Emergency Nursing, 46(5), 712–721.e1. 10.1016/j.jen.2020.06.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nagin, D. S., Koper, C. S., & Lum, C. (2020). Policy recommendations for countering mass shootings in the United States. Criminology & Public Policy, 19(1), 9–15. 10.1111/1745-9133.12484 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ogasa, N. (2022). Mass shootings and gun violence in the United States are increasing. Science news. https://www.sciencenews.org/article/gun-violence-mass-shootings-increase-united-states-data-uvalde-buffalo

- Polit, D. F., & Beck, C. T. (2012). Nursing research: Generating and assessing evidence for nursing practice (9th ed.). Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, J. (2014). Mass shootings and mental health policy. Journal of Sociology & Social Welfare, 41(1), 107–121. 10.15453/0191-5096.3835 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sabbath, E. L., Shaw, J., Stidsen, A., & Hashimoto, D. M. (2018). Protecting mental health of hospital workers after mass casualty events: A social work imperative. Social Work, 63(3), 272–275. 10.1093/sw/swy029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sampaio, F., Sequeira, C., & Teixeira, L. (2020). Nurses’ mental health during the COVID-19 outbreak. Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine, 62(10), 783–787. 10.1097/jom.0000000000001987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santana, L. C., Ferreira, L. A., & Santana, L. P. M. (2020). Occupational stress in nursing professionals of a university hospital. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 73(2). 10.1590/0034-7167-2018-0997 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Sarani, B., Smith, E., Shapiro, G., Nahmias, J., Rivas, L., McIntyre, R. C., Robinson, B. R. H., Chestovich, P. J., Amdur, R., Campion, E., Urban, S., Shnaydman, I., Joseph, B., Gates, J., Berne, J., & Estroff, J. M. (2021). Characteristics of survivors of civilian public mass shootings: An eastern association for the surgery of trauma multicenter study. The Journal of Trauma and Acute Care Surgery, 90(4), 652–658. 10.1097/ta.0000000000003069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shultz, J. M., Thoresen, S., Flynn, B., Muschert, G. W., Shaw, J. A., Espinel, Z., Walter, F. G., Gaither, J. B., Garcia-Barcena, Y., O’Keefe, K., & Cohen, A. M. (2014). Multiple vantage points on the mental health effects of mass shootings. Current Psychiatry Reports, 16(9). 10.1007/s11920-014-0469-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Silver, R. C., Holman, E. A., & Garfin, D. R. (2020). Coping with cascading collective traumas in the United States. Nature Human Behaviour, 5(1), 4–6. 10.1038/s41562-020-00981-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B., Brown, A., & Davis, C. (2022). The impact of COVID-19 on the mental health of nurses: A comprehensive review. Journal of Nursing Research, 30(2), 123–135. 10.1016/j.jnurres.2022.01.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B., & McGannon, K. R. (2018). Developing rigor in qualitative research: Problems and opportunities within sport and exercise psychology. International Review of Sport & Exercise Psychology, 11(1), 101–121. 10.1080/1750984x.2017.1317357 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J. A., Flowers, P., & Larkin, M. (2022). Interpretative phenomenological analysis: Theory, method and research. SAGE. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J., Doe, R., & Black, M. (2023). Coping mechanisms in response to traumatic events. Journal of Trauma and Stress, 15(2), 67–79. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, L. M. (2008). The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. SAGE Publications, Inc. 10.4135/9781412963909 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, S., & Wilson, J. (2024). Impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on the mental health of frontline hospital-based nurses: Rapid review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Mental Health, 53(4), 420–437. 10.1080/00207411.2024.2364133 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A., Sainsbury, P., & Craig, J. (2007). Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. International Journal for Quality in Health Care: Journal of the International Society for Quality in Health Care / ISQua, 19(6), 349–357. 10.1093/intqhc/mzm042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime . (2020). Global study on firearms trafficking 2020. https://www.unodc.org/unodc/en/firearms-protocol/firearms-study.html

- Vizheh, M., Qorbani, M., Arzaghi, S. M., Muhidin, S., Javanmard, Z., & Esmaeili, M. (2020). The mental health of healthcare workers in the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Journal of Diabetes & Metabolic Disorders, 19(2), 1967–1978. 10.1007/s40200-020-00643-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White, J. H. (2021). A phenomenological study of nurse managers’ and assistant nurse managers’ experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic in the United States. Journal of Nursing Management, 29(6), 1525–1534. 10.1111/jonm.13304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams, M., Johnson, L., & Thompson, R. (2023). Occupational stress and anxiety among nurses during the COVID-19 pandemic. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 58(3), 456–467. 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2023.02.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J., Taylor, S., Brown, A., Dolatshahi, Z., Heidari Beni, F., & Shariatpanahi, S. (2024). Factors affecting nurses retention during the COVID-19 pandemic: A systematic review. Human Resources for Health, 22(1). Article 78. 10.1186/s12960-024-00960-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . (2020a). Naming the coronavirus disease (COVID-19) and the virus that causes it. Retrieved September 10, 2022, from https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/technical-guidance/naming-the-coronavirus-disease-(covid-2019)-and-the-virus-that-causes-i

- World Health Organization . (2020b). Novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV): Situation report, 19. Retrieved September 20, 2022, from https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/330988

- World Population Review . (2025). Gun violence by country 2025. https://worldpopulationreview.com/country-rankings/gun-violence-by-country

- Zhang, Y., & Ma, Z. (2020). Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on mental health and quality of life among local residents in Liaoning Province, China: A cross-sectional study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(7), 2381. 10.3390/ijerph17072381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, R., Lucas, G. M., Becerik-Gerber, B., Southers, E. G., & Landicho, E. (2022). The impact of security countermeasures on human behavior during active shooter incidents. Scientific Reports, 12(1). 10.1038/s41598-022-04922-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available at Figshare: The double burden of stressful life events among professional nurses: public mass shootings and the COVID-19 pandemic https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.19732405.v2 (E. Imkome, 2022)