Abstract

Innovative approaches to teaching genetics are essential for improving student engagement and comprehension in this challenging field. Laboratory‐based instruction enhances engagement with the subject while fostering the development of practical competencies and deepening comprehension of theoretical concepts. However, constraints on time and financial resources limit the feasibility of conducting extended laboratory sessions that incorporate cutting‐edge genetic techniques. This study evaluated a hybrid teaching method that combined face‐to‐face (F‐2‐F) laboratory sessions with an online simulation to instruct undergraduates on gene editing and DNA sequencing. A Unity‐based simulation was developed to complement traditional F‐2‐F laboratory sessions, allowing students to practice DNA sequencing techniques in a low‐stakes environment. The simulation was integrated into a course‐based undergraduate research experience (CURE) focused on CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing in yeast. Student performance, engagement, and perceptions were assessed through laboratory assignments, access logs, and surveys. Students who engaged with the simulation prior to F‐2‐F sessions and those who engaged with the simulation over multiple days performed significantly better in assessments. Survey results indicated that most students found the simulation realistic and relevant and reported enhanced learning of DNA sequencing principles. Student confidence in DNA sequencing knowledge increased significantly after using the simulation. Student feedback highlighted benefits such as improved procedural understanding, stress reduction, and increased preparedness for F‐2‐F sessions. This approach addresses logistical challenges of traditional laboratory education while providing students with authentic, repeatable experiences in complex techniques. Our findings demonstrate the potential of integrating simulations with F‐2‐F instruction to enhance undergraduate education in genetics and molecular biology.

Keywords: CRISPR, DNA sequencing, genetics, hybrid teaching methods, simulation‐based learning, undergraduate

1. INTRODUCTION

Genetics is the study of genes, the inheritance of traits, and how variation in DNA sequence impacts the expression of these traits. Genetics is generally considered to be a difficult subject for undergraduates, 1 while laboratory‐based classes have been found to stimulate student interest in the subject and improve both scientific skills and understanding of theoretical content. 2 , 3 However, many genetics laboratory techniques are complex, time intensive, and expensive, making them difficult to include in the limited time available for undergraduate teaching. 4 To introduce novel experimental techniques in a time‐ and cost‐efficient manner in the genetics laboratory classes for 2nd‐year students at the University of South Australia (UniSA) we implemented a hybrid face‐to‐face (F‐2‐F) and online simulation as part of a semester‐long genetics laboratory course.

Simulations have been increasingly utilized to enhance learning outcomes in STEM disciplines 5 , 6 as well as subjects focused on patient care. 7 Simulations engage students through interactive, multisensory experiences and provide valuable learning opportunities that may be impractical in real‐world environments due to constraints related to cost, space, and time. 8 The hybrid online and F‐2‐F teaching method for laboratory classes has been previously used to teach the laboratory basics of enzyme kinetics, 9 monoclonal antibody production, 8 and the fundamentals of antibiotic testing 10 to undergraduate students with great success.

With the emergence of gene editing technologies such as the CRISPR/Cas9 technology 11 in the scientific and popular literature, we chose this topic to test the efficacy of a hybrid F‐2‐F and authentic simulation‐based approach on student learning of DNA sequencing. We took advantage of the course‐based undergraduate research experience (CURE), which involves students in a course addressing a research question of interest to the scientific community, 12 , 13 , 14 to develop a set of related experiments to assist in understanding gene editing. CUREs have been found to effectively engage students in research early in their academic journey and allow for equitable participation by all students. Participation in CUREs has been shown to lead to improved research skills, self‐efficacy, and interest in careers in science. 15 , 16

Our short‐CURE used CRISPR/Cas9 to generate mutations in yeast based on a previously published protocol. 17 Students used CRISPR/Cas9 to create double‐strand breaks in the CAN1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which were then repaired by non‐homologous end joining, resulting in insertions or deletions that generated frameshift mutations. CAN1 codes for an arginine transporter, which typically allows the transport of arginine from the environment into yeast cells. Selection for mutations in CAN1 is performed by growing yeast on media containing canavanine. Canavanine is a non‐proteinogenic amino acid, structurally related to L‐arginine, and is toxic to yeast cells. In strains with a functional CAN1, canavanine is imported through the CAN1 transporter and causes cell death. Cells in which CAN1 has been edited will not import canavanine and hence will grow and form colonies. Yeast genomic DNA is then isolated, and CAN1 is amplified by PCR. The PCR products are then sequenced using Sanger sequencing to determine the nature of the mutation generated.

1.1. Learning objectives

1.1.1. The learning objectives for this set of experiments are as follows

Aligning with Bloom's taxonomy, 18 after completing the laboratory class, students will:

Understand the mechanism of action of CRISPR/Cas9.

Understand the fundamentals of DNA sequencing.

Analyze and interpret DNA sequence alignments to evaluate CRISPR‐induced mutations.

Understand how changes in amino acid sequence alter protein structure and function based on the induced mutation.

Identify errors in the experimental process and predict how errors can impact experimental results.

Sanger or chain termination sequencing is a well‐established technique and is still commonly used for the generation of short, targeted sequences. We have previously used Sanger sequencing in laboratory classes; however, several issues made us hesitant to introduce it into the gene editing short‐CURE. Sanger sequencing is relatively expensive for undergraduate laboratory classes with limited budgets. 19 Depending on how the sample is prepared and the steps undertaken in the laboratory, the cost per reaction can exceed $10 USD. Successful completion of sequencing reactions requires precision in handling small volumes of reagents, and we found the failure rate of student reactions was up to 70%. Furthermore, the time involved in generating sequence results is often prohibitive for undergraduate laboratory classes. In many cases, the reactions are prepared in class and then need to be sent offsite for capillary electrophoresis.

Determining the nature of the mutation induced in the experiments is essential for an understanding of the mechanism of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing. To overcome the drawbacks of Sanger sequencing in the undergraduate laboratory, an authentic Unity‐based simulation was developed that addressed the sequencing stage of this series of experiments. Some of the benefits of this approach include the reduced cost of the experiments, unnecessary repetition of similar experimental techniques, and the ability to generate authentic end‐user data based on the actions undertaken by the student, that is, generation of errors associated with procedural errors. The simulation was designed to provide a realistic view of sequencing data that is typically generated by students in F‐2‐F laboratory classes and to allow students to generate quality DNA sequences through careful execution of experimental steps. When mistakes are made by the student, the experimental results reflect these errors, allowing students to experience the consequences of poor experimental technique in a ‘safe’ setting, while also facilitating unlimited opportunities to repeat the data generation and analysis.

The impact of the hybrid approach on student learning was assessed through the analysis of student perceptions and student performance in the laboratory assignment. Student performance improved with engagement with the simulation before the F‐2‐F class and with multiple uses of the simulation. We suggest this approach can be used with all genetics or molecular biology students and is freely available for any educator.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Student cohort

In 2023, a total of 67 students were enrolled in Genetics (BIOL 2016) at UniSA. Genetics is a 2nd‐year core course taken primarily by Bachelor of Laboratory Medicine and Bachelor of Biomedical Sciences students. Key demographic information of this combined student cohort is presented in Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Demographics of Genetics students in 2023.

| Student number | 67 |

|---|---|

| Gender | 26 Male |

| 41 Female | |

| International | 11 Yes |

| 56 No | |

| GPA (Maximum of 7, ± SEM) | 5.18 ± 1.08 |

2.2. Preparation of gene editing and DNA sequencing simulation

A modification of a laboratory module that uses CRISPR/Cas9 to generate mutations in yeast 17 was developed at UniSA. The laboratory series can be considered a short Course Undergraduate Research Experience as the students complete a mini research project from Week 2 through to completion in Week 7. Students used CRISPR/Cas9 to create double‐strand breaks in the CAN1 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae, which were then repaired by non‐homologous end joining, resulting in insertions or deletions that generated frameshift mutations. Briefly, the Saccharomyces cerevisiae strain BY4741 (MATa his3Δ1 leu2Δ0 met15Δ0 ura3Δ0) was transformed with two plasmids as previously described. The Cas9 plasmid (Addgene #43804) has a galactose‐inducible promoter that controls the expression of the Cas9 gene and a leucine selectable marker. The CAN1 gRNA plasmid (Addgene #43803) contains the gRNA for CAN1 and an uracil selectable marker, URA3.

In Week 2 of the 13‐week semester, students activate the expression of Cas9 that has been introduced on a plasmid using a galactose‐inducible promoter (Figure 1a). In Week 3, cells are plated on canavanine to select for cells containing an edited CAN1. Students extract DNA from edited colonies in Week 4 and use PCR to amplify a portion of CAN1 from both edited and control strains. In Week 6, PCR products are run on an agarose gel, and products are gel purified in preparation for DNA sequencing.

FIGURE 1.

Experimental plan and introduction of the DNA sequencing simulation. (a) Flow chart outlining the timeline and steps undertaken by the students in the gene editing laboratory classes. The DNA simulation is introduced in Week 7 and was predicted to take 15–20 min to complete. (b) Flow chart detailing the timeline and steps undertaken by students (online simulation, F‐2‐F laboratory class, interactive oral assessment) and teaching staff (email/news forum, lecture demonstration, assessment of results, interactive oral assessment) for the DNA sequencing simulation.

The DNA sequencing simulation was developed using Unity, a cross‐platform game engine. The simulation was implemented in Week 7 of the course, focusing on DNA sequencing concepts. Drawing from the sequence variations documented by de Waal et al. 17 in their gene editing experiments, we created a database of potential DNA sequence changes. To enhance the learning experience, we implemented a randomization algorithm that generates unique DNA sequences for different samples, ensuring students work with diverse data sets. The simulation interface allows students to set up the sequencing reaction, run the sequencing PCR, clean up the reaction, run the sequencer, and analyze the resulting chromatograms. The software was initially hosted on the university's learning management system for enrolled students but has since been made freely available at https://labdatagen.com/DNAseq/, where interested educators can access the simulation.

2.3. Implementation of the simulation

Students were informed of the simulation in Week 6 in a F‐2‐F lecture, e‐mail communication, and online course forum (Figure 1b). A short ‘walkthrough’ style video was produced and provided to students, as well as step‐by‐step written instructions. All students were encouraged to use the simulation in advance of attending the laboratory class in Week 7. Since the data generated by the simulation was required for the successful completion of the mini‐CURE series, the simulation was also available to students while in the F‐2‐F laboratory class in Week 7. Students who undertook the simulation in class were offered assistance with generating the required data.

2.4. Student feedback

On completion of the simulation, students were asked to complete a Likert‐style questionnaire. The questions related to their experience using the simulation, its ease of use, and confidence in their understanding of DNA sequencing. Two open‐response questions related to whether simulations should be used in other courses and the best and most challenging aspects of the simulation. Thematic analysis of open response questions was performed as previously described. 20 The corresponding author reviewed the comments, identified themes, and then determined the number of times similar comments were received. These were then reviewed by the third author.

2.5. Analysis of student performance

Student performance in the Week 7 laboratory assessment was used to evaluate the effectiveness of the simulation. Each week, students are assessed on their experimental success (whether the experiment has worked as designed) and interpretation of experimental results, understanding of the theoretical foundation of the experiments, and technical troubleshooting. Assessment takes the form of a short interactive oral assessment (viva) which allows for individual assessment of students. Student performance was also analyzed based on the number of times and days that the student accessed the simulation.

2.6. Statistical analysis

Week 7 laboratory results for each student were pooled, and the statistics were calculated using GraphPad Prism (Version 10.2.3). Results from student questionnaires were analyzed similarly.

Studies have shown that for five‐point Likert‐style items, either parametric t‐tests or non‐parametric Mann–Whitney tests are suitable to assess differences between groups. Mann–Whitney tests were used to compare groups, with a p‐value of <0.05 considered to be significant. 21

2.7. Ethics approval

Ethical clearance for this study was obtained by the UniSA Human Research Ethics Committee (# 204123).

3. RESULTS

3.1. Unity‐based DNA sequencing simulation

The simulation was designed to generate genuine data that would be produced by the CRISPR/Cas9 gene‐editing of CAN1 in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Possible mutations were based on those identified by de Waal et al. 17 and were randomly generated based on appropriate experimental techniques. The user interface of the simulation replicates a typical laboratory bench (Figure 2a). Students are required to calculate the correct volumes of reagents based on the provided experimental protocol. The students must then choose the correct virtual micropipette and set it appropriately to dispense the volumes required for the reactions. Once the reaction is prepared, the chain‐termination PCR, sequencing clean‐up, electrophoresis, and gel analysis are performed with time acceleration. A unique chromatogram based on the DNA sequence is then generated by the simulation (Figure 2b).

FIGURE 2.

Image of DNA sequencing screen and results. (a) Image showing the workspace generated by the simulation. (b) Data output showing good‐quality sequencing data. (c) Poor‐quality sequencing data due to the addition of two primers rather than a single primer. (d) Poor‐quality sequencing data due to the addition of too little template DNA.

The simulation was designed to allow students to generate quality DNA sequences through careful execution of experimental steps. When mistakes are made by the student, the experimental results reflect these errors. For example, Sanger sequencing reactions require the addition of a single oligonucleotide primer. If two primers are added to the reaction, multiple sequencing products are generated, and the resulting chromatogram will display overlapping and mixed peaks and ambiguous results (Figure 2c). Another common mistake is the miscalculation of template DNA concentration. If an insufficient amount of template DNA is added to the sequencing reaction, weak signal strength would be observed on the chromatogram (Figure 2d). Other common experimental errors and their consequences were considered in the design of the simulation, including the use of excess quantities of template DNA (resulting in ‘noisy’ chromatograms or truncated sequences), inappropriate primer amounts (leading to ‘noisy’ chromatograms), utilization of multiple template DNA samples (producing ‘double’ sequences on the chromatogram), and failures in sequencing clean‐up (resulting in poorly resolved sequences).

The simulation was hosted on the course teaching homepage and made available in Week 6 of the semester, one week before the laboratory classes based on DNA sequencing. Results from the simulation were required to be completed by the laboratory class in Week 7, so all students engaged with the simulation. However, when the students first accessed and how often the students accessed the simulation varied. Approximately 65% of the students accessed the simulation before their laboratory class in Week 7, while the remainder (35%) waited for the F‐2‐F laboratory class to engage with the simulation. The length of time spent by students on the simulation could not be accurately captured. However, based on conversations with students and teaching staff, successful completion of the simulation took between 15 and 30 min. The number of occasions on which the students accessed the simulation was recorded. Approximately 24% of the students accessed the simulation once, 56% accessed the simulation twice, and 20% accessed the simulation three or more times.

Student success in the F‐2‐F laboratory class was associated with both when and how often the students engaged with the simulation. The students were grouped into those who had or had not accessed the simulation before the laboratory class. Students within both groups were also compared based on GPA to ensure they were at a similar academic level. Students who engaged with the simulation before the F‐2‐F laboratory class performed significantly better than students who waited until the F‐2‐F laboratory class to access the simulation (p < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney test) (Figure 3a). There were no significant differences in marks for the laboratory class based on the total number of times students accessed the simulation (data not shown). However, there was an improvement in student performance based on the number of days that the simulation was accessed. Students who accessed the simulation on a total of three or more days performed better in the assessment than students who accessed the simulation on two days (p = 0.001, Kruskal‐Wallis test) or one day (p = 0.0002, Kruskal‐Wallis test) (Figure 3b).

FIGURE 3.

Student performance in Week 7 laboratory class based on the use of the simulation. (a) Students who engaged with the simulation before the F‐2‐F laboratory class (before class) performed significantly better than students who waited until the F‐2‐F laboratory class to access the simulation (in class) (p < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney test). (b) Students who accessed the simulation on a total of three or more days performed better in the assessment than students who accessed the simulation on two days (p = 0.001, Kruskal‐Wallis test) or one day (p = 0.0002, Kruskal‐Wallis test).

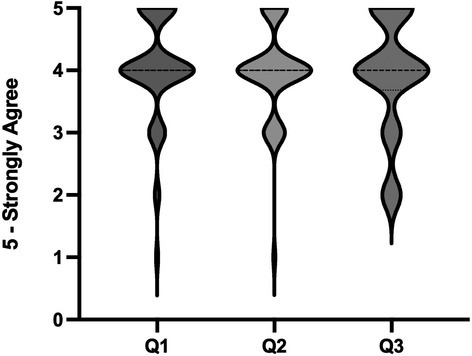

After completing the simulation, all students were invited to complete a short, anonymous questionnaire. As this was deployed in class, 58 (85%) of the students completed the questionnaire. Most students strongly agreed or agreed (SA/A) that the simulation was realistic and made learning more relevant (81% SA/A, mean 3.982/5 ± 0.097), easy to use (83% SA/A, mean 4.035/5 ± 0.110), and enhanced their learning of principles (76% SA/A, mean 3.912/5 ± 0.124) (Figure 4). When students were asked to self‐evaluate their knowledge of DNA sequencing, 67% of students said they were confident or very confident prior to the use of the simulation. After using the simulation, there was a significant increase in student confidence (p < 0.0001, Mann–Whitney U test), with 85% of students reporting being confident or very confident (Figure 5).

FIGURE 4.

Students were asked to complete an anonymous survey after completion of the simulation. A numerical score was assigned to each response: 1‐strongly disagree; 2‐disagree; 3‐neutral; 4‐agree; and 5‐strongly agree. The survey statements included Q1: I found the DNA sequencing simulation easy to use; Q2 – The graphics appeared realistic and made the learning more relevant; Q3: The simulation enhanced my learning of principles of DNA sequencing and made the concepts clear to me.

FIGURE 5.

Students were asked to complete an anonymous survey after completion of the simulation including the following two statements: 1 – BEFORE the simulation, how confident were you in your understanding of DNA sequencing?; 2 – AFTER the simulation, how confident were you in your understanding of DNA sequencing? Mann–Whitney U test, ****p < 0.0001.

Based on the student feedback on the free text questions, a thematic analysis was performed the major themes identified are shown below.

Assists understanding and procedural knowledge.

The students indicated that the simulation greatly enhanced their understanding of processes as well as the procedural steps involved. For example, the steps required to process a sample both before and after DNA sequencing. In this case, the same steps used in a true F‐2‐F setting were replicated in the simulation. As a result, the skills learned in the simulation could be immediately applied to the laboratory session.

-

2

Allows for prior preparation.

A key benefit of simulations is that they allow students to preview and prepare for the exact steps to be undertaken in the F‐2‐F laboratory session. This allows students to develop an understanding of the experimental protocol without the pressure and time constraints of the F‐2‐F session.

-

3

Prior preparation reduces stress and increases confidence.

The opportunity to prepare before attending has the added benefit of reducing the stress felt by students when in a F‐2‐F session. This stress can arise due to student comfort levels of operating within a real laboratory setting, being required to complete a task, typically for the first time, being required to generate accurate data that directly impacts an assessment, and the time pressure of a timetabled class. Furthermore, the ability to prepare in advance and preview the steps to be undertaken has enhanced individual student confidence in performing the future steps in class.

-

4

Results are generated quickly.

In a traditional F‐2‐F session, procedures typically take an extended period of time. As a result, any procedural errors made by the student will limit the ability to repeat any time‐consuming tasks, such as PCR amplification. Hence, any errors made will impact the data generated, which can affect the grade associated with the task. This is then linked to the stress felt by the students. The ability to generate data also allows students to repeat testing as required, but also to trial varying parameters within a setting to then learn the potential effects on the results, further aiding their understanding and stimulating their curiosity.

-

5

Unlimited resources and no time limit.

Typically, defined amounts of reagents are provided to students, in many cases due to their cost, but also to teach students the skill to limit wastage of materials. In the online setting, this limitation is removed, but it can also be enforced with limited volumes being made available in the settings to teach students the ability to operate within these defined limits.

-

6

Good link between online and F‐2‐F of hands‐on skills.

As noted above, the online simulation allows for prior preparation and assessment of the required processes. But the simulation was also seen as a useful aid for the F‐2‐F session where the hands‐on skills are developed. These kinesthetic skills can only be effectively delivered in this context, such as the ability to deliver very small volumes when preparing a PCR master mix. Indeed, this was a key underlying principle of this approach, using an online simulation to deliver the laboratory content and data generation linked to an F‐2‐F setting where these hands‐on skills could be further developed. In this case, the online simulation was not designed to replace the learning of hands‐on skills but to complement their development and reduce the cognitive load in learning a new technique.

-

7

Allows exploration of the impact of mistakes.

As noted above regarding limited reagents, students must also operate within a limited time frame. At UniSA, most laboratory classes are 4 h in length. However, given that reactions can take hours to complete, any errors produced impact the remaining time, and the requirement to complete multiple aspects within the same experimental laboratory all reduce the time availability. As a result, the simulation was designed with the ability to artificially accelerate time, removing this real‐world limitation. In addition, students can complete the simulation at any time that fits with their schedule and other teaching and learning constraints. Students took advantage of this flexibility, with 74% of students accessing the simulation twice or more and choosing to access the simulation into the late night and early morning.

Some challenges and areas for improvement were also identified.

Technical Issues and Performance: Some users reported lag, freezes, and crashes, indicating a need for performance optimization. There were multiple mentions of the simulation being tedious and fiddly, with a specific need for easier clicking mechanics and improved graphics/visibility. Tablet compatibility was also highlighted; however, students were advised that the current version of the simulation was not designed for use on a tablet.

Learning, Understanding and Guidance: Challenges with understanding results and identifying mistakes were noted, along with a learning curve when first using the simulation. Despite most students agreeing that the instructions provided made the simulation easy to use, some students mentioned the need for better, clearer instructions and step‐by‐step guidance, including built‐in tutorials. A short video and basic written instructions were provided to students; however, for future use, a more detailed instruction manual will be provided.

Functionality and Features: Improvements in the representation of pipetting amounts, the ability to save progress, and options for refreshing the simulation were suggested. However, the simulation was designed with these considerations in mind to increase authenticity. For example, when preparing a DNA sequencing reaction in the laboratory, there are no opportunities to ‘save’ the experiment and come back to it later. These comments demonstrate a disconnect between an online and a real‐world setting.

4. DISCUSSION

The findings of this study align with and extend the existing literature on the effectiveness of simulations in science education. In the sciences, simulations have been demonstrated to enhance conceptual comprehension and elucidate interconnections between complex ideas while simultaneously fostering the development of inquiry skills, problem‐solving capabilities, and decision‐making proficiencies in learners. 22 , 23 Extensive research has also been conducted in the domain of medical education wherein simulations have been employed to enhance the diagnostic competencies and psychomotor skills of aspiring physicians, nurses, and emergency response personnel. 24 , 25 Our results corroborate these findings, particularly in the context of genetics and molecular biology education. The observed improvements in student performance and confidence are consistent with studies that have demonstrated the benefits of simulations in reducing cognitive load and allowing for repeated practice in a low‐stakes environment. 8 , 9 Furthermore, our hybrid approach, combining simulation with F‐2‐F laboratory sessions, addresses a gap in the literature noted by Diwakar et al., 4 who emphasized the need for integrating virtual labs with traditional instruction. The positive student feedback on stress reduction and increased preparedness aligns with research by Lasater, 7 who found that simulations can enhance student confidence and clinical judgment in nursing education. Our study extends these findings to the field of genetics, demonstrating that simulations can effectively bridge the gap between theoretical knowledge and practical application in complex molecular biology techniques. This research contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting the integration of simulations in science education, particularly in areas where hands‐on experience with advanced techniques may be limited by practical constraints.

The results of our study demonstrate a statistically significant improvement in performance among students who utilized the simulation prior to F‐2‐F laboratory sessions compared to those who did not. This enhancement in performance suggests that the simulation serves as an effective preparatory tool for hands‐on laboratory work, enabling students to familiarize themselves with experimental procedures and underlying concepts. While no correlation was observed between the frequency of simulation access and laboratory assessment performance, students who engaged with the simulation on multiple occasions across different days exhibited improved performance. The ability to practice repeatedly and make errors in a risk‐free environment likely contributes to this enhanced learning, as students can refine their techniques and troubleshoot problems without the temporal and material constraints typically associated with real‐world laboratory work.

Another advantage of multiple uses of the simulation is that it was specifically designed to leverage student errors as a means of demonstrating consequences and thereby enhancing understanding of DNA sequencing mechanisms. Common experimental errors and their repercussions were integrated into the simulation, including the use of improper quantities of template DNA (resulting in poor amplification, ‘noisy’ chromatograms, or truncated sequences), inappropriate primer amounts (leading to ‘noisy’ chromatograms), utilization of multiple primers or template DNA samples (producing ‘double’ sequences on the chromatogram), and failures in sequencing clean‐up (resulting in poorly resolved sequences). Through analysis of the sequences generated by the simulation, students are afforded the opportunity to troubleshoot their experimental techniques and immediately reiterate the experiment, thereby reinforcing their learning and comprehension of the subject matter.

One of the key pedagogical strengths of the simulation lies in its authentic reproduction of common technical errors in Sanger sequencing and their downstream effects on data quality. Rather than simply preventing mistakes, the simulation was specifically designed to allow students to make errors and observe their consequences in a risk‐free environment. For example, when students add insufficient template DNA to the sequencing reaction, the resulting chromatograms show characteristically weak signal strength, just as would occur in an actual sequencing run. Similarly, the addition of excessive template DNA leads to noisy chromatograms or truncated sequences, while the use of improper primer concentrations results in poor‐quality sequence data with multiple overlapping peaks. The simulation even replicates more complex error scenarios, such as when multiple primers or template DNA samples are accidentally mixed, producing double sequences that mirror the confusing chromatogram patterns seen in real failed sequencing runs. These built‐in error states serve multiple pedagogical purposes: they help students develop troubleshooting skills by connecting specific procedural mistakes to their characteristic data signatures; they reinforce proper laboratory technique by demonstrating the concrete consequences of procedural errors; and perhaps most importantly, they allow students to learn from their mistakes without the material waste, time delays, or assessment penalties that would accompany similar errors in a physical laboratory setting. This “safe failure” environment encourages experimentation and deeper engagement with the technical aspects of sequencing, as students can freely test hypotheses about how different variables affect sequencing outcomes. 26

The favorable student responses to the simulation substantiate its efficacy as an instructional instrument. The student feedback highlighted several salient advantages of the simulation. Most students perceived the simulation as realistic, easy to use, and beneficial for their learning. These findings bear significance, as realism in simulations has been positively correlated with student engagement, 27 while perceived ease of use has been positively correlated with the usefulness of simulations. 28

Furthermore, the simulation significantly boosted student confidence in their knowledge of DNA sequencing, indicating that the simulation not only provided theoretical knowledge but also built student confidence in their practical skills. This boost in confidence is crucial, as it can lead to greater engagement and persistence in the subject matter, potentially fostering a deeper interest in genetics and related fields. 29

The thematic analysis of free‐text responses underscored the simulation's role in improving procedural understanding, allowing for better preparation, reducing stress, and enhancing confidence. Students appreciated the opportunity to practice and make mistakes in a low‐stakes environment, which is crucial for mastering complex laboratory techniques. 30 This flexibility provided by the simulation serves as a pivotal factor in catering to the diverse schedules and learning tempos of students, thereby promoting a deeper understanding of the material. One of the key benefits reported by students was the reduction in stress associated with laboratory sessions. The opportunity to engage with the simulation before attending the F‐2‐F class allowed students to prepare and become familiar with the experimental procedures, reducing the anxiety often associated with performing new and complex tasks under time constraints. This prior preparation not only helped in reducing stress but also in decreasing the cognitive load during the actual laboratory sessions, enabling students to focus more on the hands‐on aspects of the experiments.

The hybrid approach also addresses the logistical challenges associated with traditional laboratory teaching. Sanger sequencing, while a fundamental technique, is costly and time‐consuming, making it impractical for frequent use in undergraduate classes with limited budgets. By incorporating an authentic simulation, we were able to eliminate these barriers, providing students with the opportunity to learn and practice DNA sequencing without the associated expenses and time delays. The simulation's ability to accelerate experimental processes further maximizes the use of limited laboratory time, allowing for a more efficient and comprehensive educational experience. The use of this hybrid approach allowed us to compress the experiments proposed by de Waal and colleagues 17 to fit the course timetable and budget. While the use of virtual or online laboratory classes has increased since the pandemic, 31 , 32 the hybrid approach that we describe here has not been well documented in the literature.

The integration of simulations to complement F‐2‐F laboratory sessions also offers significant flexibility for teaching staff. By adjusting the simulation parameters, our designed simulation can be adapted for various DNA sequencing experiments in a teaching laboratory setting. Additionally, similar simulations can be developed to replicate other time‐ and resource‐intensive experimental protocols, such as PCR, quantitative PCR (qPCR), and other molecular techniques.

Despite the positive outcomes, there are areas for improvement. Technical issues such as occasional lag, freezes, and crashes were reported by some students, indicating a need for further optimization of the simulation software. It should be noted that most of these issues were reported by students who waited until the F‐2‐F laboratory session to engage with the simulation. The time pressure of a classroom environment may have contributed to the perception of technical issues or frustration with the user interface. Additionally, while the simulation effectively complemented the hands‐on laboratory sessions, it is essential to ensure that it does not replace the critical tactile and kinesthetic experiences that are vital for developing practical laboratory skills. Future studies could explore the long‐term impact of hybrid teaching methods on student retention and success in advanced genetics courses and research careers.

This study demonstrates that combining F‐2‐F laboratory sessions with computer simulations can effectively enhance the teaching and learning of complex scientific techniques, such as gene editing and DNA sequencing. The hybrid approach not only improves student performance and confidence but also addresses the logistical challenges of traditional laboratory education. By providing a scalable and efficient model for teaching, this method holds promise for broader application in science education, ultimately contributing to the development of well‐prepared and competent future scientists.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

Open access publishing facilitated by University of South Australia, as part of the Wiley ‐ University of South Australia agreement via the Council of Australian University Librarians.

Vedova CD, Denyer G, Costabile M. Combining face‐to‐face laboratory sessions and a computer simulation effectively teaches gene editing and DNA sequencing to undergraduate genetics students. Biochem Mol Biol Educ. 2025;53(3):286–296. 10.1002/bmb.21895

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

REFERENCES

- 1. Smith MK, Knight JK. Using the genetics concept assessment to document persistent conceptual difficulties in undergraduate genetics courses. Genetics. 2012;191(1):21–32. 10.1534/genetics.111.137810 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Brame CJ, Pruitt WM, Robinson LC. A molecular genetics laboratory course applying bioinformatics and cell biology in the context of original research. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2008;7(4):410–421. 10.1187/cbe.08-07-0036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Peteroy‐Kelly MA, Marcello MR, Crispo E, Buraei Z, Strahs D, Isaacson M, et al. Participation in a year‐long CURE embedded into major Core genetics and cellular and molecular biology laboratory courses results in gains in foundational biological concepts and experimental design skills by novice undergraduate researchers. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2017;18(1):18.1.1. 10.1128/jmbe.v18i1.1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Diwakar S, Achuthan K, Nedungadi P, Nair B. Biotechnology virtual labs: facilitating laboratory access anytime‐anywhere for classroom education. Innov Biotechnol. 2012;379–398. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Bonde MT, Makransky G, Wandall J, Larsen MV, Morsing M, Jarmer H, et al. Improving biotech education through gamified laboratory simulations. Nat Biotechnol. 2014;32(7):694–697. 10.1038/nbt.2955 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. D'Angelo C, Rutstein D, Harris C, Bernard R, Borokhovski E, Haertel G. Simulations for STEM learning: systematic review and meta‐analysis. SRI Int. 2014;5(23):1–5. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lasater K. Clinical judgment development: using simulation to create an assessment rubric. J Nurs Educ. 2007;46(11):496–503. 10.3928/01484834-20071101-04 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Costabile M, Turkanovic J. A guided interactive simulation as a tool to teach the classical approach of monoclonal antibody (MAb) production to undergraduate immunology students. J Biolog Educ. 2024;58(1):130–143. 10.1080/00219266.2022.2026804 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Costabile M, Timms H. Developing an online simulation to teach enzyme kinetics to undergraduate biochemistry students: an academic and educational designer perspective, teaching innovation unit. US: IGI Global; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Mahdi L, Denyer G, Caruso C, Costabile M. Introducing first‐year undergraduate students the fundamentals of antibiotic sensitivity testing through a combined computer simulation and face‐to‐face laboratory session. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2022;23(2):e00041‐22. 10.1128/jmbe.00041-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Jiang F, Doudna JA. CRISPR–Cas9 structures and mechanisms. Annu Rev Biophys. 2017;46:505–529. 10.1146/annurev-biophys-062215-010822 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Anderson TR. Bridging the educational research‐teaching practice gap. Biochem Mole Biol Educ. 2007;35(6):471–477. 10.1002/bmb.20135 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Corwin LA, Graham MJ, Dolan EL. Modeling course‐based undergraduate research experiences: an agenda for future research and evaluation. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2015;14(1):es1. 10.1187/cbe.14-10-0167 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Rasche ME. Outcomes of a research‐driven laboratory and literature course designed to enhance undergraduate contributions to original research. Biochem Mole Biol Educ. 2004;32(2):101–107. 10.1002/bmb.2004.494032020313 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Auchincloss LC, Laursen SL, Branchaw JL, Eagan K, Graham M, Hanauer DI, et al. Assessment of course‐based undergraduate research experiences: a meeting report. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2014;13(1):29–40. 10.1187/cbe.14-01-0004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Shortlidge EE, Bangera G, Brownell SE. Each to their own CURE: faculty who teach course‐based undergraduate research experiences report why you too should teach a CURE. J Microbiol Biol Educ. 2017;18(2):18.2.29. 10.1128/jmbe.v18i2.1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. de Waal E, Tran T, Abbondanza D, Dey A, Peterson C. An undergraduate laboratory module that uses the CRISPR/Cas9 system to generate frameshift mutations in yeast. Biochem Mole Biol Educ. 2019;47(5):573–580. 10.1002/bmb.21280 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Adams NE. Bloom's taxonomy of cognitive learning objectives. J Med Libr Assoc. 2015;103(3):152–153. 10.3163/1536-5050.103.3.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Men AE, Wilson P, Siemering K, Forrest S. Sanger DNA Sequencing. In: Next Generation Genome Sequencing, Janitz M, editors. Weinheim: Wiley‐VCH; 2008. p. 1–11. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Sullivan GM, Artino AR Jr. Analyzing and interpreting data from Likert‐type scales. Journal of Graduate Medical Education. 2013;5(4):541–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Chernikova O, Heitzmann N, Stadler M, Holzberger D, Seidel T, Fischer F. Simulation‐based learning in higher education: a meta‐analysis. Rev Educ Res. 2020;90(4):499–541. 10.3102/0034654320933544 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Wu Y‐T, Anderson OR. Technology‐enhanced stem (science, technology, engineering, and mathematics) education. J Comput Educ. 2015;2(3):245–249. 10.1007/s40692-015-0041-2 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Cook DA. How much evidence does it take? A cumulative meta‐analysis of outcomes of simulation‐based education. Med Educ. 2014;48(8):750–760. 10.1111/medu.12473 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hegland PA, Aarlie H, Strømme H, Jamtvedt G. Simulation‐based training for nurses: systematic review and meta‐analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2017;54:6–20. 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.04.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Henry MA, Shorter S, Charkoudian L, Heemstra JM, Corwin LA. FAIL is not a four‐letter word: a theoretical framework for exploring undergraduate Students' approaches to academic challenge and responses to failure in STEM learning environments. CBE Life Sci Educ. 2019;18(1):ar11. 10.1187/cbe.18-06-0108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Berro EA, Dane FC, Knoesel J. Exploring the relationships among realism, engagement, and competency in simulation. Teach Learn Nurs. 2023;18(4):e241–e245. 10.1016/j.teln.2023.07.010 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Padilha JM, Machado PP, Ribeiro AL, Ramos JL. Clinical virtual simulation in nursing education. Clin Simul Nurs. 2018;15:13–18. 10.1016/j.ecns.2017.09.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Tinto V. Exploring the character of student persistence in higher education: the impact of perception, motivation, and engagement. In: Reschly AL, Christenson SL, editors. Handbook of research on student engagement. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2022. p. 357–379. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Shepherd TD, Garrett‐Roe S. Low‐stakes, growth‐oriented testing in large‐enrollment general chemistry 1: formulation, implementation, and statistical analysis. J Chem Educ. 2024;101(8):3097–3106. 10.1021/acs.jchemed.3c00993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Byukusenge C, Nsanganwimana F, Tarmo AP. Effectiveness of virtual Laboratories in Teaching and Learning Biology: a review of literature. Int J Learn Teach Educ Res. 2022;21(6):1–17. 10.26803/ijlter.21.6.1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Zhou C. Lessons from the unexpected adoption of online teaching for an undergraduate genetics course with lab classes. Biochem Mole Biol Educ. 2020;48(5):460–463. 10.1002/bmb.21400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.