Abstract

There is an intricate connection between physical activity, bone health, and the susceptibility to stress fractures and overuse injuries. Physical activity has a positive impact on bone strength while a sedentary lifestyle can lead to a heightened risk for injury. The rise of early sports specialization has led to a substantial increase in overuse injuries, particularly in individual sports.

Bone Stress Injuries (BSI) represent a category of overuse injuries closely linked to single sport specialization. BSI involves a spectrum of altered bone mechanics, ranging from edema of periosteum, endosteum, and bone; potentially leading to partial or full cortical breaks. This condition is prevalent in high-level athletes and encompasses stress reactions and fractures, resulting from an imbalance between injury creation and repair. Up to 20% of adolescents are affected, with the tibia being the most common location, predominantly occurring in athletes aged 15 to 25. A holistic approach integrating both physical and nutritional aspects is warranted to ensure sustained musculoskeletal health across diverse pediatric and adolescent groups and athletic endeavors.

Key Concepts

-

(1)

Early and single sports specialization has a substantial impact on overuse injuries.

-

(2)

Bone stress injuries are common in high-level athletes resulting from an imbalance between creation and repair of injury.

-

(3)

Relative energy deficiency in sports (REDS) is related to a higher risk for recurrent Bone Stress Injuries.

-

(4)

Athletes that are lacking vitamin D are found to have an increased risk for stress fractures.

Keywords: Bone health, Overuse, Adolescent stress injuries

Introduction

It is well known that a sedentary lifestyle with poor nutrition and a lack of safe sun exposure is known to decrease bone mass and physical activity is known to have a positive effect on bone. Paradoxically an overdose of activity or activity done poorly can lead to bone injury. For example, baseball players with limited hip flexion and internal rotation are at risk for elbow injury [1]. Limited hip ROM causes improper trunk rotation putting more stress on the elbow. There is a relationship between low back pain and hamstring tightness, where increased tightness was associated with more severe back pain [2]. In injured football players, poor posture, kyphosis, abducted scapulae, and lordosis were associated with back and lower extremity injuries [3].

Core weakness is another risk factor for injury of the extremity and back. A strong core can reduce injury, enhance performance, and improve bone health [4], [5]. Training core muscles contribute to controlled and functional movements required for good form. Children participating in core exercises in the gym had increased muscular endurance, movement capability, and flexibility [6], [7].

Bone remodels according to activity/stress (Wolff’s Law). It takes 3 to 6 weeks for bones to remodel stronger in response to activity [8], [9], [10]. This concept validates the importance of exercise in bone health. For example, walking, running, and strength training in adults have been demonstrated to increase bone and attenuate loss, as well as decrease fracture and fall risk [9], [10]. In children, exercise plus calcium supplements results in increased bone accrual [11].

Overuse injuries and bone stress injuries

Overuse injuries are of particular concern in the pediatric/adolescent population, as this population is at higher risk than their adult counterparts due to their musculoskeletal immaturity [12]. In addition, there has been a shift over the past 20 years with increased sports participation, and it is not uncommon for present-day children to specialize in one sport at a young age. Early Sports Specialization is defined as intensive training or competition in organized sport by children younger than 12 years of age for more than 8 months per year. The focus on a single sport has been subdivided into a 3-point system that defines low, moderate, and highly specialized athletes [13], [14], [15]. A study by Pasulka et al. [16] investigated whether there was a difference in individual versus team-based sports and concluded that individual sports devotees had the highest prevalence of Early Sports Specialization and overuse injuries with tennis being ranked the highest followed by baseball/softball and volleyball [15]. The knee remains one of the most common overuse injury sites, especially in highly specialized athletes. This is caused by repetitive loading of the joint accompanied by a lack of rest in between activities and can lead to injuries involving the apophysis and physis. In the US, there are an estimated 2.5 million sport-related adolescent knee injuries per year and approximately half of them can be attributed to overuse [12], [17], [18].

Bone Stress Injuries (BSI) describe a range of altered bone mechanics including periostitis, followed by the inflammation of the tissue surrounding the bone to edema of the periosteum, endosteum, and bone itself (stress reaction), and potentially partial or full cortical breaks.

BSI are common in high-level athletes resulting from an imbalance between the creation and repair of injury. It is the result of bone’s inability to withstand stress applied in a rhythmic, repeated, subthreshold manner [8], [19]. BSIs affect up to 20% of adolescents, the tibia is the most common location accounting for 19% to 54% of total BSI, and occur most frequently in athletes between the ages of 15 to 25 [20]. The impact of this injury can be quite profound on junior level athletes causing time loss from training and competition and can even limit participation in physical activity permanently.

Upper extremity BSI

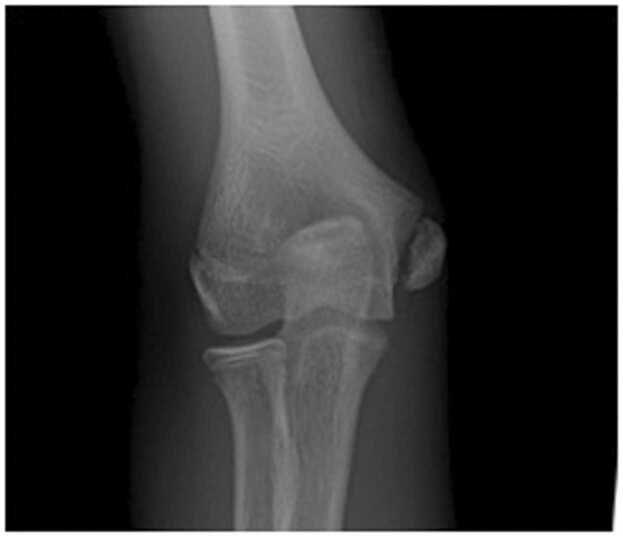

Overhead sports can cause overuse injuries, and elbow BSIs commonly occur in youth baseball pitchers, reported at 0.86 per 10,000 athletes. Whereas overuse injuries in the skeletally mature athlete consist mainly of flexor-pronator tendinitis and ulnar collateral ligament injuries, the medial epicondyle is most susceptible for overuse injuries in the skeletally immature athlete. This results in medial epicondylar apophysitis, also known as Little League Elbow (Fig. 1) [21].

Figure 1.

Distal humerus medial epicondyle avulsion fracture in a 13-year-old male baseball pitcher.

While symptoms are variable, most report vague and progressive elbow pain as well as decreasing pitch velocity and accuracy. In more severe cases, patients may experience sudden onset of pain and/or feel an acute pop. Hang et al. reported that radiographic evidence of medial epicondylar apophyseal hypertrophy was found in 94% of competitive skeletally immature baseball players. Interestingly, nearly half of the players with physical fragmentation or separation were asymptomatic [22]. To prevent overuse injuries, several organizations have published pitching guidelines. This is dependent on the child’s age, for recommended number of maximum daily pitches (Table 1): [23].

Table 1.

Pitch count limits and required rest recommendations.

| Age | Daily max pitches in games | Required days of rest based on daily amount of pitches |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 days | 1 day | 2 days | 3 days | 4 days | ||

| 7-8 | 50 | 1-20 | 21-35 | 36-50 | N/A* | N/A* |

| 9-10 | 75 | 1-20 | 21-35 | 36-50 | 51-65 | 66+ |

| 11-12 | 85 | 1-20 | 21-35 | 36-50 | 51-65 | 66+ |

| 13-14 | 95 | 1-20 | 21-35 | 36-50 | 51-65 | 66+ |

| 15-16 | 95 | 1-30 | 31-45 | 46-60 | 61-75 | 76+ |

| 17-18 | 105 | 1-30 | 31-45 | 46-60 | 61-80 | 81+ |

Not applicable to children between 7 and 8 years as no more than 50 daily pitches are allowed.

In addition, the elbow is also at risk for injury in gymnasts, athletes participating in racquet sports, as well as other throwing sports [24].

Little League Shoulder or proximal humeral epiphysitis, has also been associated with overhead sports. Overuse leads to the widening of the proximal humeral physis or epiphysiolysis (Fig. 2).

Figure 2.

Little League Shoulder in a 15-year-old male baseball pitcher as seen with the widening of the proximal humerus growth plate.

Sabick et al. hypothesized that throwing too many pitches can alter the anatomy and can lead to chronic deformation of the proximal humeral epiphyseal cartilage leading to humeral retroversion or proximal humeral epiphysiolysis [3]. Mair et al. reported that 55% of asymptomatic and 62% of symptomatic patients had radiographic evidence of physeal widening in the study population of skeletally immature male baseball players between the ages of 8 to 15 [25].

The treatment recommendation for shoulder and elbow overuse injuries should initially consist of rest followed by physical therapy [26].

Lower extremity BSI

BSIs of the lower extremity are commonly found among distance runners, ballet dancers, gymnasts, and athletes participating in soccer, lacrosse, and basketball [27]. BSIs that are at high risk for poor healing include the superior cortex of the femoral neck, patella, anterior cortex of the tibial diaphysis, medial malleolus, talus, navicular, proximal metadiaphysis of the fifth metatarsal, and great toe sesamoids. This increased risk of injury is due to increased tensile forces and/or relative hypovascularity of these bones [28]. In addition, Changstrom et al. showed in a national study of high school sports found that females will undergo stress fractures at 2 times the rate of males [29].

Female athletes presenting with what used to be called the female athlete triad and is now called Relative Energy Deficiency in Sports (RED-S) to include both males and females are at higher risk for recurrent BSI. Children with RED-S take in less calories than expended during activities, which negatively affects multiple systems in the body [29]. According to the International Olympic Committee, RED-S is defined as impaired physiological function including, but not limited, to metabolic rate, menstrual function, bone health, immunity, protein synthesis, and cardiovascular health caused by relative energy deficiency. This can lead to an increased injury risk with the resulting increase in stress fractures [30].

Several classification systems have been described in the past to stratify risk factors for BSI into low-risk and high-risk [28], [31]. More recently, Kaeding and Miller [32] proposed a grading system for the severity of BSIs, combining both clinical and radiographic factors (Table 2).

Table 2.

Kaeding-Miller classification of bone stress injuries.

| Grade | Pain | Radiographic findings (CT, MRI, Bone Scan, XR) |

|---|---|---|

| I | - | Imaging Evidence of Stress Fracture, no fracture line |

| II | + | Imaging Evidence of Stress Fracture, no fracture line |

| III | + | Nondisplaced fracture line |

| IV | + | Displaced Fracture (≥2 mm) |

| V | + | Nonunion |

Clinical presentation and imaging

Patients with BSI can present with increased pain, sensitivity, and swelling typically in the lower extremities. Pain is generally worse when body weight is shifted to the affected lower extremity. Radiographic evaluation begins with x-rays, but they have poor sensitivity in the early stages. Healing on x-ray is usually visible after 2 to 6 weeks and is seen as a thickening of the cortex. MRI is recommended when clinical suspicion is high despite unclear or normal radiographic findings (Fig. 3). Stress fractures in the anterior cortex of the tibial diaphysis are a unique type of stress fracture and are caused by hypovascularity and continuous muscular tension from the posterior leg. These fractures are also unique from an imaging standpoint as they can be visualized as the “Dreaded Black Line” seen on MRI. Analysis of this entity reveals resorption cavities lined with active osteoblasts and immature bone [33], [34].

Figure 3.

Tibial stress fracture visible on plain radiograph and MRI.

Treatment

Patients can return to play when they have 10 to 14 days of no pain at the stress fracture site, no fracture is seen or a healed fracture is seen on x-ray, the patient has completed physical therapy to work on strengthening and increased flexibility, and the patient has optimized vitamin supplementation for better bone health [35].

Recent options for biological enhancement of nonunions of stress fractures have been described and include the use of concentrated bone marrow aspirate, autologous platelet-rich technologies, injectable bone graft substitutes, subchondral calcium phosphate bone substitutes and pulsed parathyroid hormone [19]. Unfortunately, the use of these treatments is not based upon good studies that prove effectiveness, especially within the pediatric/adolescent population; future studies need to be conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of these treatments.

The role of vitamin D in bone stress injuries

Several studies have investigated the role of vitamin D and its relationship to BSI [36], [37]. Vitamin D is a fat-soluble vitamin and functions as a precursor steroid for several metabolic and biological processes. In its active form,1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D, it regulates bone formation through genomic and nongenomic mechanisms [38], [39], [40], [41], [42]. In the athletic population, even though not fully established, the ideal level has been suggested to be 40 to 50 ng/mL as studies have shown that the risk of stress fractures can increase in levels of 30 ng/mL or less [43]. Numerous studies have described 25(OH)D3 deficiency in athletes and its multifactorial nature [44], [45], [46], [47]. Athletes that are lacking 25(OH)D3 were found to have an increased risk for stress fractures [48].

Summary

There is an intricate relationship between physical activity, bone health, and the risk of stress fractures and overuse injuries. Pediatric and adolescent athletes are particularly vulnerable to stress and overuse injuries because of their skeletal immaturity, emphasizing the impact of early sports specialization on overuse injury prevalence. Parents, coaches, and clinicians should advocate for a holistic approach encompassing both physical and nutritional aspects tailored to the well-being of athletes at various stages of development.

Declarations of competing interests

The author declares the following financial interests/personal relationships: Paid consultant for Bioretec and WishBone Medical. The author has stock with Pfizer and Doximity. The author declares no conflict of interest related to the publication of this manuscript, including financial, consultant, institutional, or other relationships that may lead to bias or a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Saito M., Kenmoku T., Kameyama K., Murata R., Yusa T., Ochiai N., et al. Relationship between tightness of the hip joint and elbow pain in adolescent baseball players. Orthop J Sports Med. 2014;2(5) doi: 10.1177/2325967114532424. 2325967114532424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rizzoli R., Bianchi M.L., Garabedian M., McKay H.A., Moreno L.A. Maximizing bone mineral mass gain during growth for the prevention of fractures in the adolescents and the elderly. Bone. 2010;46(2):294–305. doi: 10.1016/j.bone.2009.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.AWS W. Sports injuries in footballers related to defects of posture and body mechanics. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 1995;35(4):289–294. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kibler W.B., Press J., Sciascia A. The role of core stability in athletic function. Sports Med. 2006;36(3):189–198. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200636030-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.MacDonald J., Stuart E., Rodenberg R. Musculoskeletal low back pain in school-aged children: a review. JAMA Pedia. 2017;171(3):280–287. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2016.3334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oliver GD A-BH, Dougherty C.P. Implementation of a core stability program for elementary school children. Athlet Train Sports Care. 2010;2(6):261–266. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gorham L.S., Jernigan T., Hudziak J., Barch D.M. Involvement in sports, hippocampal volume, and depressive symptoms in children. Biol Psychiatry Cognit Neurosci Neuroimaging. 2019;4(5):484–492. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2019.01.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bennell K., Matheson G., Meeuwisse W., Brukner P. Risk factors for stress fractures. Sports Med. 1999;28(2):91–122. doi: 10.2165/00007256-199928020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen J.H., Liu C., You L., Simmons C.A. Boning up on Wolff's Law: mechanical regulation of the cells that make and maintain bone. J Biomech. 2010;43(1):108–118. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2009.09.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Telleria J.J.M., Ready L.V., Bluman E.M., Chiodo C.P., Smith J.T. Prevalence of vitamin D deficiency in patients with talar osteochondral lesions. Foot Ankle Int. 2018;39(4):471–478. doi: 10.1177/1071100717745501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Burrows M. Exercise and bone mineral accrual in children and adolescents. J Sports Sci Med. 2007;6(3):305–312. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.DiFiori J.P., Benjamin H.J., Brenner J.S., et al. Overuse injuries and burnout in youth sports: a position statement from the American Medical Society for Sports Medicine. Br J Sports Med. 2014;48(4):287–288. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2013-093299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fabricant P.D., Lakomkin N., Sugimoto D., Tepolt F.A., Stracciolini A., Kocher M.S. Youth sports specialization and musculoskeletal injury: a systematic review of the literature. Phys Sport. 2016;44(3):257–262. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2016.1177476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaPrade R.F., Agel J., Baker J., Brenner J.S., Cordasco F.A., Côté J., et al. AOSSM early sport specialization consensus statement. Orthop J Sports Med. 2016;4(4) doi: 10.1177/2325967116644241. 2325967116644241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Popkin C.A., Bayomy A.F., Ahmad C.S. Early sport specialization. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2019;27(22):995–1000. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-18-00187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pasulka J., Jayanthi N., McCann A., Dugas L.R., LaBella C. Specialization patterns across various youth sports and relationship to injury risk. Phys Sport. 2017;45(3):344–352. doi: 10.1080/00913847.2017.1313077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sweeney E., Rodenberg R., MacDonald J. Overuse knee pain in the pediatric and adolescent athlete. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2020;19(11):479–485. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Watkins J., Peabody P. Sports injuries in children and adolescents treated at a sports injury clinic. J Sports Med Phys Fit. 1996;36(1):43–48. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Miller T.L., Kaeding C.C., Rodeo S.A. Emerging options for biologic enhancement of stress fracture healing in athletes. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(1):1–9. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Nussbaum E.D., King C., Epstein R., Bjornaraa J., Buckley P.S., Gatt C.J., Jr. Retrospective review of radiographic imaging of tibial bony stress injuries in adolescent athletes with positive mri findings: a comparative study. Sports Health. 2023;15(2):244–249. doi: 10.1177/19417381221109537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lansdown D.A., Rugg C.M., Feeley B.T., Pandya N.K. Single sport specialization in the skeletally immature athlete: current concepts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(17):752–758. doi: 10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hang D.W., Chao C.M., Hang Y.S. A clinical and roentgenographic study of Little League elbow. Am J Sports Med. 2004;32(1):79–84. doi: 10.1177/0095399703258674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Baseball M.L. Guidelines for youth and adolescent pitchers. https://www.mlb.com/pitch-smart/pitchingguidelines. Accessed 10th October 2023.

- 24.Magra M., Caine D., Maffulli N. A review of epidemiology of paediatric elbow injuries in sports. Sports Med. 2007;37(8):717–735. doi: 10.2165/00007256-200737080-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mair S.D., Uhl T.L., Robbe R.G., Brindle K.A. Physeal changes and range-of-motion differences in the dominant shoulders of skeletally immature baseball players. J Shoulder Elb Surg. 2004;13(5):487–491. doi: 10.1016/j.jse.2004.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Heyworth B.E., Kramer D.E., Martin D.J., Micheli L.J., Kocher M.S., Bae D.S. Trends in the presentation, management, and outcomes of little league shoulder. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6):1431–1438. doi: 10.1177/0363546516632744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McInnis K.C., Ramey L.N. High-risk stress fractures: diagnosis and management. PM R. 2016;8(3 Suppl):S113–S124. doi: 10.1016/j.pmrj.2015.09.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Boden B.P., Osbahr D.C., Jimenez C. Low-risk stress fractures. Am J Sports Med. 2001;29(1):100–111. doi: 10.1177/03635465010290010201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Papageorgiou M., Dolan E., Elliott-Sale K.J., Sale C. Reduced energy availability: implications for bone health in physically active populations. Eur J Nutr. 2018;57(3):847–859. doi: 10.1007/s00394-017-1498-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mountjoy M., Sundgot-Borgen J.K., Burke L.M., Ackerman K.E., Blauwet C., Constantini N., et al. IOC consensus statement on relative energy deficiency in sport (RED-S): 2018 update. Br J Sports Med. 2018;52(11):687–697. doi: 10.1136/bjsports-2018-099193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Boden B.P., Osbahr D.C. High-risk stress fractures: evaluation and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2000;8(6):344–353. doi: 10.5435/00124635-200011000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kaeding C.C., Miller T. The comprehensive description of stress fractures: a new classification system. J Bone Jt Surg Am. 2013;95(13):1214–1220. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.L.00890. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kiel J.K.K.. Stress Reaction and Fractures. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507835/. Accessed 15th October 2023.

- 34.Minkowitz B., Nadel L., McDermott M., Cherna Z., Ristic J., Chiu S., et al. Obtaining vitamin D levels in children with fractures improves supplementation compliance. J Pedia Orthop. 2019;39(6):436–440. doi: 10.1097/BPO.0000000000001363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Astur D.C., Zanatta F., Arliani G.G., Moraes E.R., Pochini Ade C., Ejnisman B. Stress fractures: definition, diagnosis and treatment. Rev Bras Ortop. 2016;51(1):3–10. doi: 10.1016/j.rboe.2015.12.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lawley R., Syrop I.P., Fredericson M. Vitamin D for improved bone health and prevention of stress fractures: a review of the literature. Curr Sports Med Rep. 2020;19(6):202–208. doi: 10.1249/JSR.0000000000000718. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Davey T., Lanham-New S.A., Shaw A.M., Hale B., Cobley R., Berry J.L., et al. Low serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D is associated with increased risk of stress fracture during Royal Marine recruit training. Osteoporos Int. 2016;27(1):171–179. doi: 10.1007/s00198-015-3228-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Christakos S., Ajibade D.V., Dhawan P., Fechner A.J., Mady L.J. Vitamin D: metabolism. Rheum Dis Clin N Am. 2012;38(1):1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.rdc.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilson-Barnes S.L., Hunt J.E.A., Williams E.L., et al. Seasonal variation in vitamin D status, bone health and athletic performance in competitive university student athletes: a longitudinal study. J Nutr Sci. 2020;9 doi: 10.1017/jns.2020.1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Jones G. Metabolism and biomarkers of vitamin D. Scand J Clin Lab Invest Suppl. 2012;243:7–13. doi: 10.3109/00365513.2012.681892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Wang T.T., Tavera-Mendoza L.E., Laperriere D., Libby E., Burton MacLeod N., et al. Large-scale in silico and microarray-based identification of direct 1,25-dihydroxyvitamin D3 target genes. Mol Endocrinol. 2005;19(11):2685–2695. doi: 10.1210/me.2005-0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Knechtle B., Jastrzebski Z., Hill L., Nikolaidis P.T. Vitamin D and stress fractures in sport: preventive and therapeutic measures-a narrative review. Medicine. 2021;57(3):223. doi: 10.3390/medicina57030223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Shimasaki Y., Nagao M., Miyamori T., Aoba Y., Fukushi N., Saita Y., et al. Evaluating the risk of a fifth metatarsal stress fracture by measuring the serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D levels. Foot Ankle Int. 2016;37(3):307–311. doi: 10.1177/1071100715617042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.El Asmar M.S., Naoum J.J., Arbid E.J. Vitamin k dependent proteins and the role of vitamin k2 in the modulation of vascular calcification: a review. Oman Med J. 2014;29(3):172–177. doi: 10.5001/omj.2014.44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sikora-Klak J., Narvy S.J., Yang J., Makhni E., Kharrazi F.D., Mehran N. The effect of abnormal vitamin D levels in athletes. Perm J. 2018;22 doi: 10.7812/TPP/17-216. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Williams K., Askew C., Mazoue C., Guy J., Torres-McGehee T.M., Jackson Iii J.B. Vitamin D3 supplementation and stress fractures in high-risk collegiate athletes—a pilot study. Orthop Res Rev. 2020;12:9–17. doi: 10.2147/ORR.S233387. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Butscheidt S., Rolvien T., Ueblacker P., Amling M., Barvencik F. [Impact of Vitamin D in Sports: Does Vitamin D Insufficiency Compromise Athletic Performance?]. Sportverletz Sportschaden. Jan 2017;31(1):37–44. Bedeutung von Vitamin D im Sport: Reduziert ein Mangel die Leistungsfahigkeit? doi:10.1055/s-0042–121748. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 48.Angeline M.E., Gee A.O., Shindle M., Warren R.F., Rodeo S.A. The effects of vitamin D deficiency in athletes. Am J Sports Med. 2013;41(2):461–464. doi: 10.1177/0363546513475787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]