Abstract

Acute kidney injury (AKI) is a common and serious complication resulting from ischemia and hypoxia, leading to significant morbidity and mortality. Autophagy, a cellular process for degrading damaged components, plays a crucial role in kidney protection. The unfolded protein response pathway, particularly the inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1α)/X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) signaling cascade, is implicated in regulating autophagy during renal stress. To elucidate the role of the IRE1α/XBP1 pathway in autophagy during hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) and ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) injury, renal tubular epithelial cells (TECs) were subjected to H/R conditions, and I/R injury was induced in mice. The expression of autophagy-related and endoplasmic reticulum stress markers (IRE1α, XBP1, GRP78, Beclin1, LC3I/II, and P62) was assessed using immunoblotting and immunofluorescence. Additionally, the impacts of IRE1α overexpression and pharmacological agents, IXA6 (IRE1α agonist), and STF083010 (IRE1α inhibitor) were evaluated on autophagy regulation. H/R injury significantly increased mitochondrial damage and the formation of autophagic vesicles in TECs. Key markers of autophagy were elevated in response to H/R and I/R injury, with activation of the IRE1α/XBP1 pathway enhancing autophagic processes. IXA6 treatment improved renal function and reduced injury in I/R models, while STF083010 exacerbated kidney damage. The IRE1α/XBP1 pathway is a critical regulator of autophagy in renal TECs during ischemic stress, suggesting that pharmacological modulation of this pathway may offer therapeutic avenues for preventing or mitigating AKI. Enhanced understanding of these mechanisms may lead to novel strategies for kidney disease management.

Keywords: Autophagy, Ischemia-reperfusion, Endoplasmic reticulum stress, XBP1s, Chronic kidney disease

Highlights

-

•

Inositol-requiring enzyme 1/X-box binding protein 1 signaling enhances autophagy during ischemic kidney injury.

-

•

Autophagy protects renal tubular epithelial cells from ischemia stress.

-

•

IXA6 improves kidney function; STF083010 worsens damage in ischemia/reperfusion models.

-

•

Targeting inositol-requiring enzyme 1/X-box binding protein 1 may provide new strategies against acute kidney injury.

-

•

Study reveals potential for new therapies in kidney disease management.

Introduction

Ischemia-reperfusion (I/R) injury is a common cause of target organ damage, leading to various significant diseases, including myocardial infarction, hypovolemic shock, thromboembolism, and acute kidney injury (AKI). In the kidneys, I/R injury is a major contributor to acute renal failure, potentially resulting in functional deterioration or loss of the organ. The transient occlusion of renal blood vessels is followed by a reperfusion phase, during which the release of reactive oxygen species and nitrogenous compounds induces further tissue damage.1 This condition often occurs in several clinical scenarios, such as kidney transplantation, trauma, and sepsis. Studies have shown that renal I/R can result in multiple pathological changes, including inflammatory responses, oxidative stress, intracellular calcium overload, activation of the renin-angiotensin system, and microcirculatory disturbances, all of which contribute to tubular injury. Given the high morbidity and mortality associated with AKI, it is crucial to actively investigate the underlying molecular mechanisms to develop new therapeutic strategies aimed at reducing acute mortality from I/R and preventing the progression of AKI to chronic renal failure.

The endoplasmic reticulum (ER), an essential organelle responsible for protein synthesis, folding, and transport along with Ca2+ storage, is vulnerable to stress (ERS) under adverse conditions such as nutrient deficiency, hypoxia, oxidative stress, or calcium overload. This leads to the accumulation of unfolded proteins.2 Subsequently, during ERS, the accumulation of unfolded proteins triggers the transcriptional activation of multiple chaperone genes and the initiation of the ER-associated degradation (ERAD) system. The ERAD system functions to transfer and eliminate misfolded proteins via proteasomal degradation. This process is known as the unfolded protein response (UPR). Key transmembrane receptor proteins involved in UPR in mammalian cells include activating transcription factor 6, inositol-requiring enzyme 1 (IRE1α), and protein kinase-like ER kinase.3 Under resting conditions, these receptors are inactive as they are bound to glucose-regulated protein 78 (GRP78)/immunoglobulin-binding protein. When unfolded proteins accumulate in the ER, immunoglobulin-binding protein dissociates from the receptors to bind the unfolded proteins, activating them. The oligomerization and autophosphorylation of IRE1 stimulate its endoribonuclease activity, leading to the splicing of X-box binding protein 1 (XBP1) mRNA and the subsequent translation into spliced XBP1 (XBP1s).4 XBP1s triggers the autophagic response in endothelial cells by promoting the formation of autophagosomes and the expression of Beclin1 and LC3-βII. Beclin1 plays a crucial role in the initial phase of autophagosome formation, and experimental evidence indicates that upregulation of Beclin1 expression can stimulate autophagy in mammalian cells.5

XBP1s is a critical mediator of ERS. In most contexts, XBP1s function as a protective factor within the ER, regulating multicellular biological functions and participating in the expression of signal transduction genes, redox homeostasis, cell growth, and differentiation, as well as carbohydrate metabolism. A decrease in XBP1s mRNA levels leads to prolonged ERS. During chronic or irreversible ERS, the inactivation of XBP1s may increase cellular susceptibility to death.6 XBP1s exhibit antiapoptotic properties in renal tubular epithelial cells (TECs).7 For example, in hypoxic-ischemic encephalopathy, the blockade of XBP1 results in increased ERS and substantial activation of IRE1, which negatively impacts protein translation and ultimately leads to cellular inflammation.8

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved, lysosome-dependent degradation process that encompasses the breakdown of large biomolecules, such as proteins, glycogen, lipids, and nucleotides, as well as organelles including mitochondria and peroxisomes. It plays a vital role in maintaining cellular homeostasis and survival under stress conditions, such as I/R injury. Three major types of autophagy exist: macroautophagy, microautophagy, and chaperone-mediated autophagy. Macroautophagy is the most extensively studied and involves several sequential steps, including initiation, vesicle elongation, autophagosome maturation, and fusion with lysosomes. In the final phase, the contents of the autophagosome are degraded by lysosomal acid hydrolases, and lysosomal contents are released to facilitate metabolic cycling. Ample evidence suggests that autophagy is involved in the pathogenesis of ischemic diseases and provides protective effects in renal tissues.9 Additionally, both in vitro hypoxia and in vivo I/R injury models highlight autophagy as a crucial protective mechanism.10

Protein misfolding and ERS are prominent features observed in various renal diseases, including primary glomerulonephritis, genetically associated glomerular diseases, diabetic nephropathy, and AKI.11 In these conditions, the ER membrane encapsulates unfolded or misfolded proteins, leading to the formation of numerous autophagosomes. These autophagosomes subsequently fuse with lysosomes, facilitating the degradation of damaged proteins and organelles, thereby inhibiting apoptosis and alleviating excessive ERS.12 Recent studies have reported a significant involvement of ERS in the development of renal fibrosis, with ERS-related proteins being highly expressed in renal fibroblasts.13

I/R events frequently precipitate ER dysfunction and concomitant ERS. ERS induces IRE1 oligomerization and autophosphorylation, which in turn activates its endoribonuclease function to cleave XBP1 mRNA and give rise to spliced XBP1s. Research has demonstrated that the transfection of intestinal epithelial cells with lentiviral XBP1 significantly enhances the expression of autophagy-related genes, including ATG7, Beclin1, and LC3-II, thereby increasing the number of autophagic vesicles and suppressing inflammatory responses.14, 15

In this study, we aim to investigate the role of excessive ERS following I/R injury in the activation of IRE1α, leading to increased expression of active XBP1s. This, in turn, promotes the expression of GRP78, which regulates Beclin1 expression, enhances autophagy, and ultimately exerts a protective effect against renal damage.

Results

Ultrastructural and molecular analysis of mitochondrial dysfunction and autophagy in TECs following H/R and I/R injury

When examining the ultrastructure of the cells in the hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) groups under transmission electron microscopy (TEM), it was observed that the mitochondria (m) were moderately swollen, some mitochondrial matrices had become lighter, and the cristae had blurred, diminished, and disappeared. There were numerous autophagic vesicles in the cytoplasm. However, in the H/R 12 h group, there were numerous swollen mitochondria, a few of the mitochondrial matrices were faint, and the cristae were blurred, which increased the number of autophagic vesicles in the cytoplasm (Figure 1(a)). The renal TECs of the I/R 3 d and I/R 7 d mice exhibited an increased number of autophagic vesicles and enhanced mitochondrial damage (mitochondrial swelling and loss of mitochondrial cristae), compared to Sham mice (Figure 1(b)). These results suggested that enhance autophagy level occurs in the H/R-induced cells model and I/R-induced mice model. Furthermore, compared with normoxia (Nor), H/R induced a significant increase in the expression of IRE1α, XBP1, XBP1s, LC3I/II, GRP78, Beclin1 and markers of kidney injury Kim1, and the expression of P62 was downregulated, as tested by immunofluorescence and Western Blot in HK-2 cells (Figure 1(c) and (d)). Histograms on the right show the relative protein expression by western blot (Figure 1(e)). These results indicate that H/R and I/R significantly enhance autophagy and contribute to mitochondrial damage in renal TECs.

Fig. 1.

Mitochondrial alterations and autophagic activity in renal tubular epithelial cells (TECs) under hypoxia/reoxygenation (H/R) and ischemia/reperfusion (I/R) conditions. (a) Transmission electron microscopy images of TECs subjected to H/R reveal moderate mitochondrial swelling and disruption of cristae architecture, along with a marked increase in cytoplasmic autophagic vesicles at 6 and 12 h compared to normoxia (Nor) conditions. Red arrows indicate autophagic vesicles, bar = 5 µm (n = 3 experiments). (b) Transmission electron microscopy images of TECs from I/R mice at 3 and 7 days postinjury show enhanced mitochondrial damage and increased autophagic vesicle accumulation compared to sham-operated controls (Sham). Bar = 1 µm (n = 3 independent experiments). (c) Immunofluorescence analysis shows significant upregulation of IRE1α, XBP1, XBP1s, LC3I/II, GRP78, Beclin1, and Kim1, accompanied by a downregulation of P62 expression in HK-2 cells following H/R injury compared to normoxic controls (Nor). Magnification: 400×. Bar = 20 µm. (d) Western blot analysis the proteins expression of IRE1α, XBP1, XBP1s, LC3I/II, GRP78, P62, Beclin1, and Kim1. (e) Histograms depict relative protein levels quantified from western blot analyses, **P < 0.01. Each experiment was repeated three times. Abbreviations used: GRP78, glucose-regulated protein 78; IRE1α, inositol-requiring enzyme 1; XBP1, X-box binding protein 1.

Regulation of autophagy by the IRE1α/XBP1 signaling pathway in TECs

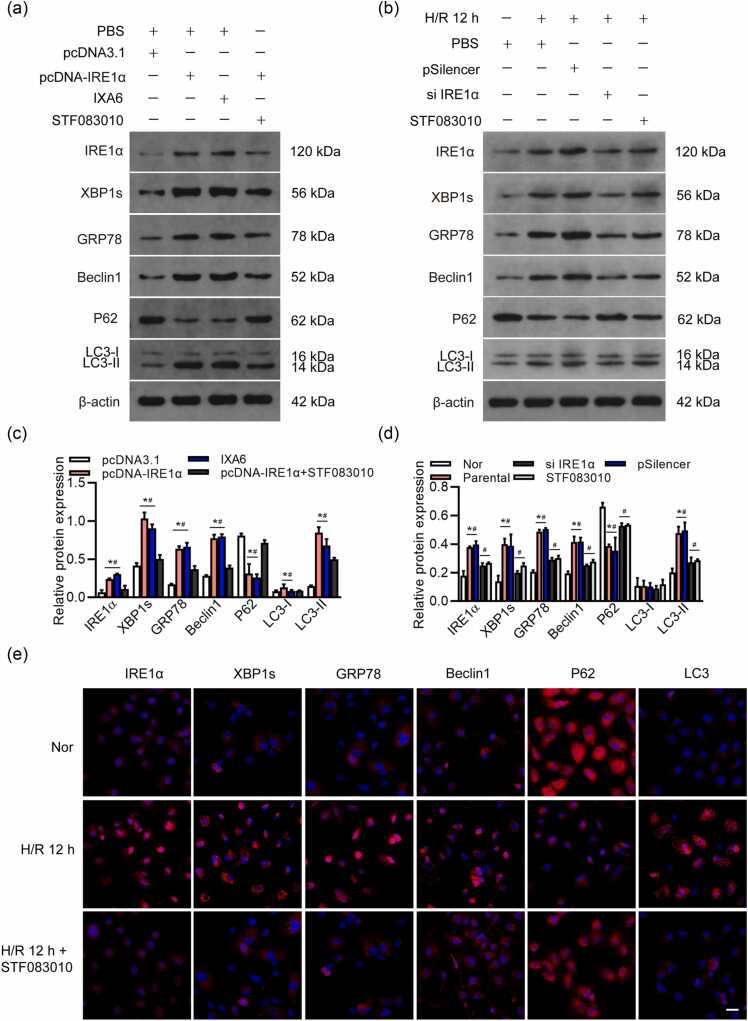

To assess whether the IRE1α/XBP1 pathway was a key pathway of autophagy, we examined the HK-2 cells in the following groups: those with IRE1α overexpression (transfected with pcDNA-IRE1α), those treated with IXA6 (an agonist of the IRE1α/XBP1 pathway that can induce IRE1α ribonuclease activity), and those with IRE1α overexpression and cotreated with STF083010. We confirmed that overexpression of IRE1α significantly enhanced GRP78 and autophagy-related proteins Beclin1 and LC3I/II and downregulated P62, and pathway inhibitor STF083010 reduced the expression of IRE1α/XBP1 and downregulated GRP78 and autophagy-related proteins Beclin1 and LC3I/II, upregulation of P62. Overexpressing of IRE1α, combined with inhibition of IRE1α/XBP1 (using STF083010), can alleviate autophagy-associated phenotypes caused by upregulation of IRE1α alone (Figure 2(a)). Si IRE1α or STF083010 alleviates the I/R-induced increase of IRE1α, XBP1s, GRP78, Beclin1 expression and decrease of P62 expression in HK-2 cells (Figure 2(b)). Histograms show the relative protein expression by western blot (Figure 2(c) and (d)). These data suggest that IRE1α/XBP1s might be involved in the cellular events elicited by the exposure of TECs to H/R stimulation, including autophagy progression. To assess the effect of IRE1α/XBP1s on autophagy in TECs, HK-2 cells were treated with STF083010 to silence IRE1α/XBP1s pathway, the expression of IRE1α, XBP1s, GRP78, Beclin1, and LC3 were decreased under H/R 12 h, and the expression of P62 was upregulated under H/R 12 h, as tested by immunofluorescence (Figure 2(e)).

Fig. 2.

Effects of IRE1α/XBP1 overexpression and inhibition on autophagy in HK-2 cells. (a) Western blot analysis of IRE1α, XBP1s, GRP78, Beclin1, P62, and LC3I/II levels in HK-2 cells overexpressing of IRE1α and treated with IXA6 (IRE1α inhibitor) and/or STF083010 (IRE1α inhibitor). (b) Silencing of IRE1α or treatment with STF083010 attenuates the I/R-induced upregulation of IRE1α, XBP1s, GRP78, and Beclin1, alongside a reduction in P62 levels in HK-2 cells, as assessed by western blot. (c) and (d) Histograms provide quantitative analysis of relative protein expression levels determined by western blotting, *P < 0.05 compared with the pcDNA3.1/Nor, #P < 0.05, compared to the pcDNA-IRE1α+STF083010/STF083010. (e) Immunofluorescence analysis of IRE1α, XBP1s, GRP78, Beclin1, P62, and LC3 expression in HK-2 cells under normoxia (Nor) or H/R conditions at 12 h (H/R 12 h). Each experiment was repeated three times. Magnification: 400×. Bar = 20 µm. Abbreviations used: GRP78, glucose-regulated protein 78; H/R, hypoxia/reoxygenation; I/R, ischemia/reperfusion; IRE1α, inositol-requiring enzyme 1; XBP1, X-box binding protein 1.

The role of GRP78 as a downstream target of the IRE1α/XBP1 pathway in modulating autophagy in HK-2 cells

To confirm that the IRE1α/XBP1s pathway induces autophagy through its downstream target gene GRP78, HK-2 cells were treated with STF083010 while overexpressing XBP1. This treatment significantly reduced the pcDNA-XBP1-induced increase in GRP78 levels, as well as the expression of autophagy-related genes Beclin1 and LC3I/II under normoxic conditions (Figure 3(a) and (b)). Traditionally, TEM is considered the "gold standard" for detecting the induction of autophagy. To visualize autophagosome formation directly, we utilized TEM to examine the autophagic ultrastructure in cells treated with pcDNA-XBP1, STF083010, or IXA6. Interestingly, we observed several large, single-membrane autophagic vacuoles. However, we found a significant decrease in the number of autophagic vacuoles in cells treated with STF083010 or with both pcDNA-XBP1 and STF083010, compared to those treated with pcDNA-XBP1 or IXA6 alone (Figure 3(c) and (d)).

Fig. 3.

Effects of XBP1 overexpression and IRE1α inhibition on GRP78 and autophagy-related gene expression in HK-2 cells. (a) HK-2 cells were treated with IXA6 (IRE1α agonist), STF-083010 (IRE1α inhibitor), and/or pcDNA-XBP1 under normoxic conditions. Western blot analysis was performed to assess the protein levels of IXBP1s, GRP78, Beclin1, P62, and LC3I/II. (b) Histogram d represents the relative protein levels quantified from western blot analyses. Data are presented as mean ± scanning electron microscopy (SEM) from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared to the control group. (c) and (d) PcDNA-XBP1-infected, and/or STF-083010-infected, IXA6-treated, or vehicle cells (pcDNA 3.1) at 48 h were processed and analyzed for the formation of autophagosomes or autolysosomes via electron transmission microscopy. Red arrows indicate autophagic vacuoles. Scale bar: 20 and 8 µm. Abbreviations used: GRP78, glucose-regulated protein 78; IRE1α, inositol-requiring enzyme 1; XBP1, X-box binding protein 1.

Functional role of autophagy in renal injury following I/R in mice

To investigate the functional role of autophagy in kidney injury, we examined the induction of autophagy in the kidney after injury induced by I/R-AKI in mice. We first determined the expression of two autophagy-related proteins, Beclin1 and LC3, in renal cortex of kidneys at 1, 3, and 7 days after I/R-AKI and compared it with sham-operated kidneys. As shown in Figure 4(a), the levels of IRE1α, XBP1s, GRP78, autophagy-related proteins Beclin1 and LC3I/II, and the kidney injury marker Kim1 were elevated in the kidneys at 3 and 7 days after I/R-AKI, while P62 levels were significantly reduced during the same period. Histograms on the right illustrate the relative protein expression as determined by western blot (Figure 4(b)). Immunohistochemical staining demonstrated that I/R treatment upregulated the expression of IRE1α, XBP1s, GRP78, Beclin1, and LC3 in the renal tubules of mice at 7 days post-I/R. Inhibition of the IRE1α/XBP1 pathway by STF083010 alleviated the elevated expression of these proteins (Figure 4(c)). Furthermore, STF083010 treatment exacerbated kidney injury by suppressing autophagy in I/R mice, as evidenced by a reduction in the percentage of healthy tubules observed in hematoxylin and eosin staining and increased levels of BUN and SCR levels (Figure 4(d)-(f)). To investigate the role of autophagy in I/R-AKI, IXA6 was administered intraperitoneally to mice following 7 days of I/R (Figure 4(c)). IXA6 further enhanced autophagy induced by I/R, significantly alleviated tubule injury, and improved renal function (Figure 4(d)-(f)). These findings highlight the critical role of autophagy in ameliorating renal injury following I/R events.

Fig. 4.

Autophagy activation and its impact on kidney injury in I/R-AKI model. (a) Western blot analysis of renal cortex samples shows increased expression of IRE1α, XBP1s, GRP78, and autophagy-related proteins (Beclin1 and LC3I/II) at 3 and 7 days post-I/R-AKI compared to sham-operated kidneys, alongside a significant decrease in P62 levels. (b) Histograms illustrate the relative protein expression quantified from western blot data. Sham, n = 8; I/R, n = 8. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05 compared to the sham group. (c) H&E staining showed the morphology of the renal cortex, and immunohistochemical staining revealed significant upregulation of IRE1α, XBP1s, GRP78, Beclin1, and LC3, as well as downregulation of P62 in renal tubules of I/R mice at 7 days compared to the sham group. Treatment with STF083010 inhibited this pathway, leading to reduced expression of these markers and increased of P62. Sham, n = 8; I/R, n = 8. Bar = 50 µm. (d-f) Histological analysis (H&E staining) demonstrated that STF083010 exacerbated kidney injury, as evidenced by a reduced percentage of healthy tubules and elevated levels of BUN and SCR in I/R mice. In contrast, post-I/R injection of IXA6 further promoted autophagy, significantly mitigated renal tubule injury, and improved renal function, as indicated by decreased BUN and SCR levels. Sham, n = 8; I/R, n = 8. Data are presented as mean ± SEM from three independent experiments. *P < 0.05. Abbreviations used: GRP78, glucose-regulated protein 78; H&E, hematoxylin and eosin; I/R, ischemia/reperfusion; IRE1α, inositol-requiring enzyme 1; XBP1, X-box binding protein 1.

Discussion

The present study provides compelling evidence that H/R injury initiates a cascade of cellular events, primarily characterized by the induction of autophagy in renal TECs, leading to subsequent renal injury. Our ultrastructural analysis of cells from H/R conditions revealed distinct mitochondrial abnormalities, including swelling, diminished cristae, and a substantial accumulation of autophagic vesicles. These findings highlight a critical adaptive response of TECs to environmental stress, indicated by the increased autophagy as the cells attempt to mitigate mitochondrial dysfunction and maintain cellular homeostasis. In particular, our data suggest that during the initial phases of injury, enhanced levels of autophagy serve to recycle damaged cellular components, potentially protecting against progressive injury. However, prolonged H/R exposure correlates with further mitochondrial damage and greater autophagic activity, suggesting a dual role where excessive autophagy may contribute to cell death if deregulated.

A substantial body of evidence indicates that autophagy is involved in the development of ischemic diseases and plays a protective role in the kidneys.16 Autophagy has been shown to exert protective effects against the senescence of renal proximal tubule cells and acute ischemic injury,17 as well as against kidney damage caused by heavy metals.18 Furthermore, leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 can protect against AKI by activating podocyte autophagy.19 The correlation between autophagy and kidney injury is underscored by our findings of increased expression of key autophagy and endoplasmic reticulum stress-related markers, including IRE1α, XBP1, GRP78, Beclin1, and LC3I/II, in response to H/R injury. The decline in P62 expression also reinforces the notion of enhanced autophagic flux under these conditions. The results demonstrate that the cellular response to oxidative stress involves robust autophagic machinery aimed at facilitating the degradation of damaged organelles and proteins. Interestingly, our in vivo experiments involving I/R injury further validated these findings, as TECs from I/R mice exhibited similar alterations in autophagic markers, emphasizing the universality of this response across different injury models.

Among the classic UPR pathways, the IRE1α/XBP1 signaling pathway is well-established as being involved in a wide range of pathophysiological processes, including neurodegeneration, inflammation, metabolic disorders, organ ischemia and injury, and tumorigenesis.8, 20, 21, 22, 23 Critical to our understanding of the molecular mechanisms mediating autophagy in TECs is the IRE1α/XBP1 pathway. Our experimentation utilizing IRE1α overexpression and pathway agonist IXA6 confirmed that activation of this pathway directly promotes autophagy. The significant upregulation of GRP78-a well-known chaperone involved in regulating the UPR and other autophagy-related proteins (i.e., Beclin1 and LC3I/II) upon IRE1α activation indicates that this pathway is essential for executing the autophagic response in TECs during H/R injury. The small-molecule IRE1α inhibitor 4μ8c binds to K599 (in the kinase domain) and K907 (in the RNase domain) of the IRE1α protein via Schiff-base formation, thereby inhibiting both the kinase and RNase activities of IRE1α. In contrast, STF083010 specifically restricts its reactivity to K907.24 Conversely, inhibition of the IRE1α pathway using STF083010 resulted in the downregulation of these protective markers and an increase in P62, demonstrating a disrupted autophagic response. Collectively, these data point to the IRE1α/XBP1 pathway as a crucial signaling cascade that not only facilitates autophagic degradation but also roles in maintaining cellular integrity during acute kidney stress.

ERS represents an adaptive response of the UPR that can lead to cell death if not properly regulated.25 As a key protein in one of the three major UPR signaling pathways, IRE1α can induce the splicing of XBP1 mRNA to generate its transcriptionally active form, XBP1s, which then translocates to the nucleus to activate UPR-related genes and components involved in ERAD. Normally, the N-terminus of IRE1α interacts with GRP78, a chaperone belonging to the heat shock protein family. When the endoplasmic reticulum is stressed, GRP78 is released and binds to unfolded or misfolded proteins.26, 27 This study aimed to investigate the role of the IRE1α/XBP1 pathway in autophagy associated with I/R-induced AKI. Under stressful conditions, GRP78 conduces the transcriptional activity of XBP1s, which activates the expression of autophagy-related genes. Our data support the notion that overexpression of GRP78 enhances the autophagic process, while its repression increases P62 levels, indicative of impaired degradation processes. This relationship elucidates a complex interplay between the UPR and autophagy, highlighting the significance of GRP78 as a feedback regulator within the cellular response to injury.

Investigating the functional role of autophagy in the context of renal I/R injury provides further insights into potential therapeutic avenues. Treatment with IXA6 not only induced autophagy in the renal tubules but also alleviated renal injury observed in I/R-AKI models. The upregulation of autophagic markers following IXA6 treatment and the restoration of renal function underscores the potential of harnessing autophagy for renal protection. In stark contrast, blocking the IRE1α/XBP1s pathway resulted in exacerbated kidney injury, characterized by a decrease in healthy tubule percentage and heightened levels of BUN and SCR. These findings suggest that therapeutic strategies aimed at modulating autophagic flux via the IRE1α/XBP1s signaling pathway could serve as a novel approach to mitigate AKI.

In summary, our research elucidates the dual role of autophagy in renal TECs during hypoxia and reoxygenation injury, a crucial aspect of renal pathology. The enhanced autophagic response observed in response to H/R and I/R injuries serves as a protective mechanism; however, prolonged or excessive activation can lead to cellular dysfunction and injury. The IRE1α/XBP1 pathway emerges as a pivotal regulator of this process, mediating the autophagic response through the downstream activation of GRP78 and other autophagy-related proteins. The therapeutic potential of this pathway is evidenced by the beneficial effects of enhancing its activity in mitigating renal injury. Future studies should aim to further dissect the intricate signaling networks involved and evaluate the long-term outcomes of targeting autophagy in various models of renal injury, ultimately paving the way for innovative treatment strategies in AKI.

Conclusions

Overall, the integration of cellular stress responses, such as autophagy and UPR signaling, is vital for the preservation of renal function under conditions of ischemia. Understanding these relationships enhances our comprehension of renal pathophysiology and could lead to the identification of novel biomarkers and therapeutic targets for kidney disease management. Continued exploration in this area may yield significant advancements in the treatment of acute kidney injuries and improve the prognosis for patients suffering from renal ailments exacerbated by such ischemic injuries.

Materials and methods

Cells

Cell culture

HK-2 human proximal TECs were maintained in Dulbecco's modified eagle medium (DMEM) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum and penicillin/streptomycin (100 µg/mL) at 37 °C in a 5% CO2 environment. Routine testing confirmed that the cells were free from mycoplasma contamination.

H/R model

To establish the H/R model, HK-2 cells underwent a 12-h incubation in a hypoxic chamber (94% N2, 1% O2, and 5% CO2) without nutrients (glucose-free, serum-free). Following this, the cells were transferred to fresh medium for reoxygenation periods of 6, 12, and 24 h under normoxic conditions (95% air and 5% CO2). The control group was consistently maintained in a nutrient-rich, normoxic environment.

Cell treatments

The IRE1α/XBP-1s inhibitor STF083010 (30 µM for 12 h, Selleck, China) was administered 12 h prior to H/R treatment, with phosphate - buffered saline (PBS) serving as the control. HK-2 cells were transduced with lentivirus encoding a modified short hairpin RNA targeting GFP (control, Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd.) or pcDNA-IRE1α (Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd.) to generate pSilencer 3.1 (scrambled shRNA) and si IRE1α. Transduced cells were selected using 0.75 µg/mL puromycin (Sigma-Aldrich). For overexpression of IRE1α and XBP1, HK-2 cells were transfected with pcDNA-IRE1α or pCMV6-XBP1 (both from Shanghai Genechem Co., Ltd.) using Lipofectamine® 2000 (Life Technology) and harvested 24 h post transfection.

Animal studies

Animal rearing and breeding

Male C57BL/6J mice (18–22 g) were sourced from the Fourth Military Medical University Laboratory Animal Center (Xi’an, China) and housed in an animal facility maintained at 21–25 °C with 55–70% relative humidity, on a 12-h light-dark cycle. All animal experimental procedures were approved by the Animal Care and Use Committee of Northwest University and adhered to the National Institutes of Health Guidelines for Laboratory Animal Care.

Renal I/R-AKI models in vivo

Renal ischemia-induced AKI was modeled using an I/R injury protocol in male mice aged 8–10 weeks (n = 6–8 per group). Mice were divided into five groups: Sham, I/R 1 day, I/R 3 days, I/R 7 days, and I/R 7 days + STF083010. Renal I/R was induced after anesthetizing the mice intraperitoneally with pentobarbital sodium (50 mg/kg). Mice were positioned prone on a heated surface with an absorbent pad, and a midline dorsal incision (∼1.5 cm) was made. The bilateral flank muscle and fascia were incised to exteriorize the kidneys. Ischemia was induced by clamping the right renal pedicle for 30 min with nontraumatic clamps. The sham group underwent the same surgical procedure without ischemia. After 24 h, the mice were sacrificed, and blood samples and kidneys were collected.

In I/R 7 days + STF083010 group, mice received daily intraperitoneal injections of STF083010 (30 mg/kg, MedChemExpress), starting 1 h after the I/R operation. Following treatment, all groups were sacrificed, and blood was collected for serum creatinine (Scr) and blood urea nitrogen (BUN) analysis. Isolated serum samples were stored at −80 °C for future analysis, while kidney tissues were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for histological examination. Remaining kidney tissues were preserved at −80 °C for protein analysis.

Histology and histopathology

Kidney tissues were fixed in 10% neutral buffered formalin and embedded in paraffin. Sections measuring 5 µm were prepared for hematoxylin and eosin staining (Leica). The degree of renal injury was assessed through morphometric analysis of tubular damage and interstitial fibrosis. To evaluate tubular damage following I/R, eight random visual fields at 400× magnification were selected from each slide, and the number of healthy tubules was counted manually using Adobe Photoshop's counting tool. Healthy tubules were identified based on their dimensions, structural integrity, nucleus-to-cytoplasm ratio, and the condition of the brush border and basal membrane, resembling those of normal renal tubules. For quantifying the percentage of healthy tubules in the I/R model, the same eight fields were analyzed using grid intersection analysis in Adobe Photoshop. Representative images were captured with a Leica DM 1000 LED microscope and an MC120 HD Microscope Camera using Las V4.4 Software.

Western blot analysis

HK-2 cells and kidney samples from both sham and I/R-AKI groups were excised and homogenized. The following antibodies were utilized for western blotting: anti-β-actin (Wuhan Doctor De Biological Engineering Co., LTD, BM0627, 1:1000), anti-rabbit GRP78 (Abcam, ab108615, 1:500), anti-mouse P62 (Abcam, ab56416, 1:500), anti-rabbit LC3I/II (14/16 kDa) (Cell signaling technology, 12741T, 1:500), anti-rabbit IRE1α (Novus, NB100–2324, 1:300), anti-rabbit XBP1 (Abcam, ab37152, 1:500), anti-rabbit XBP1s (Cell signaling technology, 40435, 1:500), anti-rabbit Beclin1 (Abcam, ab210498, 1:500), and anti-rabbit Kim1 (is also known as Tim1) (Abcam, ab47635, 1:400). Equal amounts of protein were separated by Sodium dodecyl sulfate - polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS)-PAGE and transferred to Polyvinylidene Fluoride (PVDF) membranes. The membranes were blocked with 5% skim milk at room temperature for 2 h and then incubated overnight at 4 °C with the primary antibody. Following this, membranes were incubated with either anti-mouse (#7076S, Cell Signaling Technology) or anti-rabbit secondary antibodies (#7074S, Cell Signaling Technology) for 1 h at room temperature. The blots were developed in a dark room using autoradiography film (Denville Scientific, Inc.) and quantified using densitometry with Image J Analysis software (National Institutes of Health).

Immunohistochemistry and immunofluorescence

Formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded kidney Section (5 µm thick) were deparaffinized, rehydrated, and subjected to antigen retrieval at 98 °C for 10 min in 10 mM citrate buffer (pH 6). The tissue sections were then incubated with 4% CWFS gelatin (Aurion) in TBS or PBS for 1 h before being incubated overnight with the primary antibodies. The primary antibodies used included anti-mouse P62 (Abcam, ab56416, 1:300), anti-rabbit LC3I/II (14/16 kDa) (Cell signaling technology, 12741 T, 1:100), anti-rabbit IRE1α (Novus, NB100–2324, 1:100), anti-rabbit XBP1 (Abcam, ab37152, 1:200), anti-rabbit XBP1s (Cell signaling technology, 40435, 1:200), anti-rabbit GRP78 (Abcam, ab108615, 1:250), anti-rabbit Beclin1 (Abcam, ab210498, 1:300), and anti-rabbit Kim1 (is also known as Tim1) (Abcam, ab47635, 1:300), following the manufacturer’s instructions. For other stainings, sections were treated with biotinylated goat anti-rabbit and streptavidin HRP (Biocare Medical) for 10 min each. Counterstaining was performed using hematoxylin, and DAB positivity was analyzed in eight visual fields at 400× magnification.

For immunocytochemistry, HK-2 cells on coverslips were fixed with 100% methanol for 5 min at −20 °C, followed by blocking in a buffer (0.1% Tween, 1% BSA, 10% normal goat serum, and 0.3 M glycine in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature. The cells were then incubated overnight at 4 °C with primary antibodies. The following day, cells were treated with Alexa Fluor594-conjugated anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen, 1:250) or Cy3-conjugated anti-rabbit IgG (Wuhan Doctor De Biological Engineering Co., Ltd., 1:200) and DAPI (Beyotime Biotechnology, C1002) for nuclear staining. Representative images were captured using a Demo Axio Observer.Z1 motorized inverted microscope equipped with an Axiocam 506 monochrome camera and ZEN software (Zeiss). To ensure that printed images accurately reflected the high-resolution screens, color brightness was adjusted uniformly across all images using Adobe Photoshop.

Statistical analysis

Quantitative results from three independent experiments were analyzed using GraphPad Prism version 8.0 (GraphPad Software, Inc., San Diego, CA, USA). Data are presented as mean ± standard deviation. Comparisons of quantitative results were performed using Student’s t-tests or one-way analysis of variance with Tukey’s post hoc tests. Statistical significance was determined at P < 0.05.

Ethics statement

All animal experimental procedures were performed in accordance with the animal use protocol approved by the Animal Care and User Committee of Northwest University (approval number: KY20183109-1).

Funding and support

This study was supported by the Natural Science Foundation of Shaanxi Province (2023-JC-YB-701) and the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 81900676).

Author contributions

All authors contributed to the study conception and design. Ting Liu and Lu Li: conceived and designed the study. Meixia Meng and Ming Gao: carried out experiments. Jinhua Zhang: analyzed the data. Yuan Zhang and Yukun Gan: made the figures. Yangjie Dang and Limin Liu: drafted and revised the paper; all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Liu Limin: Writing – review & editing, Validation, Supervision, Funding acquisition. Dang Yangjie: Writing – review & editing, Supervision. Gan Yukun: Visualization. Zhang Yuan: Visualization, Supervision, Conceptualization. Zhang Jinhua: Software, Formal analysis. Gao Ming: Methodology, Formal analysis. Meng Meixia: Methodology, Data curation. Li Lu: Writing – original draft, Conceptualization. Liu Ting: Writing – review & editing, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Declarations of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Contributor Information

Yangjie Dang, Email: dangyangjie1991@163.com.

Limin Liu, Email: liulimin@nwu.edu.cn.

Data availability statement

No data were used for the research described in the article.

References

- 1.Huang J., Chan K.W.Y. Editorial for "Multi-Parametric MRI for Evaluating Variations in Renal Structure, Function, and Endogenous Metabolites in an Animal Model With Acute Kidney Injury Induced by Ischemia Reperfusion". J Magn Reson Imaging. 2024;60:256–257. doi: 10.1002/jmri.30104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu J., Xue W., Xiang H., et al. Cathelicidin PR-39 peptide inhibits hypoxia/reperfusion-induced kidney cell apoptosis by suppression of the endoplasmic reticulum-stress pathway. Acta Biochim Biophys Sin. 2016;48:714–722. doi: 10.1093/abbs/gmw060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ishibashi T., Morita S., Kishimoto S., et al. Nicotinic acetylcholine receptor signaling regulates inositol-requiring enzyme 1 alpha activation to protect beta-cells against terminal unfolded protein response under irremediable endoplasmic reticulum stress. J Diabetes Investig. 2020;11:801–813. doi: 10.1111/jdi.13114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zhao D., Yang J., Han K., et al. The unfolded protein response induced by Tembusu virus infection. BMC Vet Res. 2019;15:34. doi: 10.1186/s12917-019-1859-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tian P.G., Jiang Z.X., Li J.H., Zhou Z., Zhang Q.H. Spliced XBP1 promotes macrophage survival and autophagy by interacting with Beclin-1. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2015;463:518–523. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2015.05.104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Song J., Zhao W., Lu C., Shao X. Spliced X-box binding protein 1 induces liver cancer cell death via activating the Mst1-JNK-mROS signaling pathway. J Cell Physiol. 2020;235:9378–9387. doi: 10.1002/jcp.29678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ferre S., Deng Y., Huen S.C., et al. Renal tubular cell spliced X-box binding protein 1 (Xbp1s) has a unique role in sepsis-induced acute kidney injury and inflammation. Kidney Int. 2019;96:1359–1373. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2019.08.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cai Q., Shen L., Zhang X., Zhang Z., Wang T. The IRE1-XBP1 axis regulates NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated microglia activation in hypoxic ischemic encephalopathy. Crit Rev Immunol. 2025;45:55–64. doi: 10.1615/CritRevImmunol.2025025868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li H., Wang S., An S., Gao B., Wu D., Li Y. Hydrogen sulphide reduces renal ischemia-reperfusion injury by enhancing autophagy and reducing oxidative stress. Nephrology. 2024;29:645–654. doi: 10.1111/nep.14034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhang S., Xia W., Duan H., Li X., Qian S., Shen H. Ischemic preconditioning alleviates mouse renal ischemia/reperfusion injury by enhancing autophagy activity of proximal tubular cells. Kidney Dis. 2022;8:217–230. doi: 10.1159/000521850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Habshi T., Shelke V., Kale A., Anders H.J., Gaikwad A.B. Role of endoplasmic reticulum stress and autophagy in the transition from acute kidney injury to chronic kidney disease. J Cell Physiol. 2023;238:82–93. doi: 10.1002/jcp.31322. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ricciardi C.A., Gnudi L. Endoplasmic reticulum stress in chronic kidney disease. New molecular targets from bench to the bedside. G Ital Nefrol. 2019;36(6) vol6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guo S., Tong Y., Li T., et al. Endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated cell death in renal fibrosis. Biomolecules. 2024;14(8):919. doi: 10.3390/biom14020289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Adolph T.E., Tomczak M.F., Niederreiter L., et al. Paneth cells as a site of origin for intestinal inflammation. Nature. 2013;503:272–291. doi: 10.1038/nature12721. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Z.H., Jiang J., Dai W.G., et al. MicroRNA-674-5p induced by HIF-1α targets XBP-1 in intestinal epithelial cell injury during endotoxemia. Cell Death Discovery. 2020;6:70. doi: 10.1038/s41420-020-0290-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Zhong Y., Sun D., Yao Y., et al. Autophagy and mitochondrial dynamics contribute to the protective effect of diosgenin against 3-MCPD induced kidney injury. Chem Biol Interact. 2022;355 doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2022.109850. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Isaka Y., Kimura T., Takabatake Y. The protective role of autophagy against aging and acute ischemic injury in kidney proximal tubular cells. Autophagy. 2011;7:1085–1087. doi: 10.4161/auto.7.9.16990. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Avila-Rojas S.H., Lira-Leon A., Aparicio-Trejo O.E., Reyes-Fermin L.M., Pedraza-Chaverri J. Role of autophagy on heavy metal-induced renal damage and the protective effects of curcumin in autophagy and kidney preservation. Medicina. 2019;55(7) doi: 10.3390/medicina55050081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Wang J.P., Yan J.P., Xiao R.L., Li R.S. Leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 is protective during acute kidney injury through its activation of autophagy in podocytes. Environ Toxicol. 2022;37:2947–2956. doi: 10.1002/tox.23329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cabral-Miranda F., Tamburini G., Martinez G., et al. Unfolded protein response IRE1/XBP1 signaling is required for healthy mammalian brain aging. EMBO J. 2022;41 doi: 10.15252/embj.2022111952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Li Z., Xu T., Peng L., et al. Polystyrene nanoplastics aggravate lipopolysaccharide-induced apoptosis in mouse kidney cells by regulating IRE1/XBP1 endoplasmic reticulum stress pathway via oxidative stress. J Cell Physiol. 2023;238:151–164. doi: 10.1002/jcp.32963. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Barua D., Gupta A., Gupta S. Targeting the IRE1-XBP1 axis to overcome endocrine resistance in breast cancer: Opportunities and challenges. Cancer Lett. 2020;486:29–37. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2020.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Peng J., Qin C., Ramatchandirin B., et al. Activation of the canonical ER stress IRE1-XBP1 pathway by insulin regulates glucose and lipid metabolism. J Biol Chem. 2022;298 doi: 10.1016/j.jbc.2022.102283. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cross B.C., Bond P.J., Sadowski P.G., et al. The molecular basis for selective inhibition of unconventional mRNA splicing by an IRE1-binding small molecule. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109:E869–E878. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1117788109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Naama M., Bel S. Autophagy-ER stress crosstalk controls mucus secretion and susceptibility to gut inflammation. Autophagy. 2023;19:3014–3016. doi: 10.1080/15548627.2023.2279608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shin W.J., Ha D.P., Machida K., Lee A.S. The stress-inducible ER chaperone GRP78/BiP is upregulated during SARS-CoV-2 infection and acts as a pro-viral protein. Nat Commun. 2022;13:6551. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-34357-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Liu Z., Liu G., Ha D.P., Wang J., Xiong M., Lee A.S. ER chaperone GRP78/BiP translocates to the nucleus under stress and acts as a transcriptional regulator. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2023;120 doi: 10.1073/pnas.2303448120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data were used for the research described in the article.