Abstract

Background

Women with suspected ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA) are often challenging to manage. We aimed to understand mechanisms and treatable pathways of refractory angina.

Methods

The Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation – Coronary Vascular Dysfunction (NCT00832702) recruited women between 2008 and 2015. In a pre-defined subgroup (n = 198) with repeat cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) at 1-year, we investigated severity of angina (Seattle Angina Questionnaire-7) in relation to risk factors, baseline invasive coronary function testing, and CMRI parameters. Refractory angina was defined as SAQ-7 score < 75 at baseline and < 10-point improvement at 1-year.

Results

Women with refractory angina (n = 60, 30 %), compared to those without, had lower incomes, and higher proportion of hypertension and nitrate use at 1-year (p < 0.05). They also had significantly lower baseline coronary blood flow (CBF) response to acetylcholine (p < 0.01). Myocardial perfusion reserve index was not different at baseline or follow-up. At 1-year, changes in SAQ domain scores significantly differed between groups, with persistent lack of improvement in physical limitation, disease perception, angina stability, and angina frequency (p < 0.05) in the refractory group. In an age-adjusted regression model, hypertension (OR 4.48; 95 % CI 1.23–16.25; p = 0.02) and abnormal CBF (OR 3.34; 95 % CI 1.04–10.72; p = 0.04) were associated with refractory angina.

Conclusions

Refractory angina is common in women with INOCA. Hypertension and endothelial-dependent microvascular dysfunction are independently associated with a 4- and 3-fold increase in refractory angina at 1-year, respectively. These findings may identify potential treatment targets to reduce angina burden in INOCA.

Keywords: Refractory angina, INOCA, SAQ, CMRI

1. Background

Ischemia with no obstructive coronary artery disease (INOCA) is a challenging clinical condition that predominately affects women [1]. As much as 70 % of women presenting for invasive coronary angiography have normal or non-obstructive coronary arteries (<50 % diameter stenosis), with many often being told they have non-cardiac symptoms [2]. Notably, INOCA is increasingly described in men, whereby up to 50 % of men undergoing clinically indicated coronary angiography have normal or non-obstructive coronary disease, and are less likely to be treated [3].

Despite having no significant epicardial obstructive coronary artery disease (CAD), INOCA patients often continue to have a high burden of symptoms that contribute to reduced quality of life and increased use of health care resources from repeated evaluations and hospitalizations [4]. Refractory anginal symptoms are associated with long-term anxiety, depression, and impaired physical functioning [5]. Furthermore, in the multicenter cohort study of the original Women's Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE)(NCT00000554), women with INOCA and persistent chest pain at 1-year follow-up had double the rates of major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE), including non-fatal myocardial infarctions (MI), strokes, congestive heart failure, and cardiovascular death, compared to those without persistent chest pain [6].

Currently, treatment options for patients with refractory angina include beta and alpha-beta blockers, vasodilators, such as nitrates or calcium channel blockers (CCB), ranolazine, and novel therapeutics that include ivabradine, enhanced external counter-pulsation (EECP), or spinal cord stimulation [1,7]. The efficacy of these therapies for treatment pathways have been incompletely evaluated and the pathophysiology contributing to persistent symptoms in women with INOCA remains poorly understood [8,9]. Therefore, we sought to phenotype those with refractory angina to understand potential treatable pathway mechanisms.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

The recruitment of participants for the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute–sponsored WISE-CVD study (NCT00832702) occurred between 2008 and 2015 and included eligible women older than 18 years with symptoms and/or signs of suspected myocardial ischemia undergoing clinically-indicated coronary angiography. Details of the study design and complete methodology has been described elsewhere [10]. Briefly, major exclusion criteria included pregnancy, contraindications to cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (CMRI) or invasive coronary function testing (CFT), significant structural heart disease (cardiomyopathy, valvular, or congenital heart disease), recent MI, language barrier to questionnaire testing, or comorbidities that would compromise follow-up. Women with recent or planned coronary angioplasty or coronary artery bypass grafting were also excluded. Institutional review board approval was obtained at each individual participating site (Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles; and University of Florida, Gainesville).

2.2. Data collection procedures

Standardized questionnaires were used to gather information about baseline medical history, demographics, physical examination, and the Duke Activity Status Inventory (DASI), where higher DASI scores to a maximum 58.2 indicated higher functional class [11]. Hypertension was defined as a systolic blood pressure ≥ 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure > 90 mmHg, or a self-reported history of hypertension. Responses to the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) were collected at baseline and 1-year follow-up visits. The SAQ and shortened version, SAQ-7, are validated tools for assessment of angina [12,13]. The SAQ measures five domains of quality of life in patients with CAD, including physical limitation, angina stability, angina frequency, treatment satisfaction, and disease perception; the SAQ-7 captures physical limitation, angina frequency, and disease perception. Values are totaled from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating better quality of life, and a change of 10 points in any of the domains is considered clinically relevant [14]. Previous validation studies have shown for clinical interpretation, the SAQ summary score can be categorized into ranges of 0 to 24 (very poor to poor health status), 25 to 49 (poor to fair), 50 to 74 (fair to good), and 75 to 100 (good to excellent), with a change of 10 points in any of the subscales considered to be clinically important [12,14,15]. For this study, refractory angina was defined as an SAQ-7 score < 75 at baseline (indicating at least mild to moderate angina) and a change of <10 points at 1-year follow-up, reflecting a lack of clinically important improvement. This definition aligns with previously established SAQ score categorizations and thresholds for clinical relevance [14,16,17].

2.3. CMRI protocol and analysis

In a pre-defined subgroup, 198 participants underwent both CMRI scans at baseline and 1-year follow-up, as previously described [10]. Briefly, scans were performed in the supine position on a 1.5T MRI (Magnetom Avanto, Siemens Healthcare, Erlangen, Germany) with ECG gating, using a standardized protocol to assess left ventricular (LV) morphology, function, and first-pass contrast-enhanced myocardial perfusion imaging [10]. CMRI analysis using commercially available software (CAASc MRV 3.3, Pie Medical Imaging B.V., The Netherlands) provided measures of global myocardial perfusion reserve index (MPRI) of short-axis images in the basal, mid, and distal slices [18]. MPRI threshold of <1.84 identifies the presence of coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD), as demonstrated previously [18].

2.4. Invasive coronary function testing

In a pre-defined subgroup, participants underwent invasive coronary angiography and CFT via the femoral approach to evaluate different phenotypes of vascular function, as previously described [10]. Briefly, a Doppler guidewire placed in the proximal left anterior descending coronary artery and intracoronary injections of adenosine (18 and 36 μg) was used to induced hyperemia. Coronary flow reserve (CFR) was calculated with values <2.5 indicating non-endothelial dependent microvascular dysfunction. Coronary blood flow (CBF) and coronary artery diameter response to intracoronary infusions of acetylcholine (36 μg) was used to assess microvascular and macrovascular endothelial-dependent function, respectively. Endothelial-dependent microvascular dysfunction was defined as a blunted CBF of ≤50 % in response to acetylcholine. Abnormal endothelial-dependent macrovascular coronary function was defined as ≤0 % (no change or constriction of vessel) in epicardial coronary artery diameter in response to a maximum dose of acetylcholine. Coronary macrovascular non-endothelial function (smooth muscle function) was tested using 200 μg of intracoronary nitroglycerin, whereby coronary diameter response to ≤20 % dilation was abnormal.

2.5. Statistical analysis

Reported values were summarized as mean (standard deviation [SD]) for continuous variables or percentages for categorical variables. Changes in collected parameters at 1-year are summarized as percent change from baseline. Tests for categorical variables between those with and without refractory angina were chi-squared tests. In circumstances where variables had low counts, Fisher's Exact test was used. For continuous variables, t-tests were performed, unless the distributions were non-normal, in which case Wilcoxon rank sum test was used. A multivariable logistic regression model was made with the outcome of refractory angina and explanatory variable of abnormal CBF response (<50 %), adjusted for age, household income, history of hypertension, DASI score, baseline nitrates use and MPRI. Unadjusted logistic regression was also used with abnormal CBF as the outcome and each SAQ domain as explanatory variables. Significance level was defined as p < 0.05 for all tests.

3. Results

3.1. Baseline measurements

Table 1 shows the baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of the 198 women with suspected INOCA. Overall, there was high prevalence of refractory angina in this population, with one-third of the women reported having refractory angina. The breakdown by race and ethnicity between White/non-Hispanics and Non-White of the cohorts are shown, which did not differ by the presence of refractory angina (p = 0.1258). Compared to those without refractory angina, women with refractory angina were significantly more hypertensive, had lower incomes, lower DASI scores, and had greater nitrate use at one year (42 % vs 26 %). There was no significant difference in baseline medications (including calcium channel blockers, beta blockers, nitrates, ranolazine, ace inhibitors (ACE—I) or angiotensin receptor blockers (ARB), statins, or low dose aspirin), and the proportion of women on two or more antianginal medications after one year remained similar.

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of participants with refractory and non-refractory angina (n = 198).

| Clinical Characteristic | Refractory Angina (n = 60) | Non-Refractory Angina (n = 138) | P-Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 53.5 (10.4) | 54.9 (10.4) | 0.39 |

| Hypertension (%) | 49 | 33 | 0.04 |

| Baseline systolic blood pressure | 132.4 (19.3) | 129.2 (21.0) | 0.32 |

| Baseline diastolic blood pressure | 68.9 (10.9) | 63.2 (13.7) | 0.001 |

| Dyslipidemia (%) | 22 | 18 | 0.51 |

| Diabetes (%) | 9 | 12 | 0.62 |

| Smoking history (%) | 39 | 44 | 0.64 |

| Postmenopausal | 75 | 70 | 0.49 |

| BMI | 29.7 (7.3) | 28.2 (6.9) | 0.09 |

| DASI score | 4.8 (4.1) | 8.0 (5.1) | <0.0001 |

| Income <$50,000 (%) | 42 | 26 | 0.02 |

| $50,000 < Income <$99,000 | 32 | 27 | |

| $100,000 < Income | 25 | 47 | |

| Race and Ethnicity | 0.60 | ||

| White/non-Hispanic | 42 (70.0) | 102 (74) | |

| Non-White | 18 (30) | 36 (26) |

Values are mean (SD) or (%).

Fig. 1 shows the baseline results of the pre-defined subgroup of women who underwent CFT. Women with refractory angina more often had microvascular endothelial dysfunction, of which 74 % (20 of 27) had an increase in CBF ≤50 % in response to ACh, compared to 42 % (34 of 82) of those with non-refractory angina (p < 0.01). There were no significant differences in the proportion of women with non-endothelial dependent microvascular dysfunction (29 % [9/31] vs 35 % [32/92]); abnormal macrovascular endothelial coronary function (49 % [16/33] vs 47 % [42/89]), or abnormal coronary macrovascular non-endothelial function (70 % [23/33] vs 64 % [58/90]). Further, while the majority of these women with refractory angina had more abnormal CFT pathways, there was no significant association between the number of abnormal CFT pathways and refractory angina.

Fig. 1.

Baseline measurements of the pre-defined subgroup of women who underwent coronary function testing (n = 198), comparing those with refractory angina vs without (non-refractory angina). CFR: coronary flow reserve; CBF: coronary blood flow; ACH: Acetylcholine; NTG: nitroglycerine.

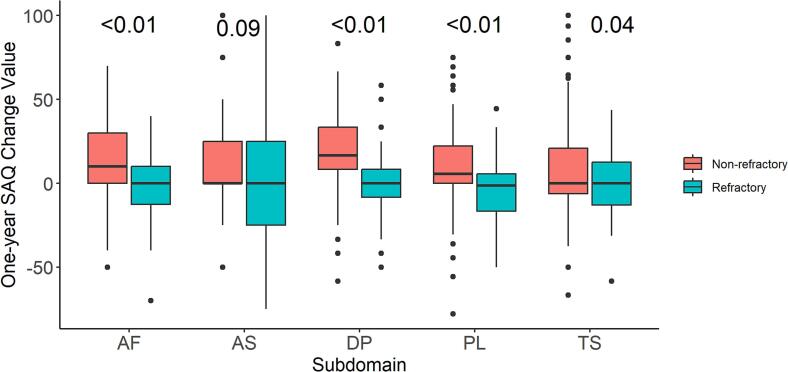

3.2. Interval change in SAQ and CMRI measurements

The absolute change from baseline to 1-year follow-up in SAQ subscale scores are shown in Fig. 2 and overall demonstrated change in each of the SAQ domains for women with refractory angina compared to those with non-refractory angina were significant for all, but angina stability. Women with non-refractory angina demonstrated the greatest improvement in subscales of disease perception (18.6 ± 24 change), followed by angina frequency (13.3 ± 24.6 change), and physical limitation (9.7 ± 23 change).

Fig. 2.

Absolute change in Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ) domain scores from baseline to follow-up in patients without vs with refractory angina. Positive values indicate improvement and negative values indicate worsening of the SAQ domain. AF: angina F = frequency; AS: angina stability; DP: disease perception; PL: physical limitation; TS: treatment satisfaction.

There was no significant difference in the baseline or 1-year follow-up CMRI parameters in those with refractory vs without refractory angina, including no significant difference in LV ejection fraction [65.9 % (9.0) vs 68.0 % (6.8); p = 0.15], LV end-diastolic volume [120.8 ml (23.5) vs 122.7 ml (25.3); p = 0.87]; LV end-systolic volume [41.8 ml (16.5) vs 39.7 ml (13.4); p = 0.62]; LV mass [94.1 g (17.5) vs 92.0 g (16.3); p = 0.33]; or MPRI [1.7 ml (0.5) vs 1.9 ml (0.5); p = 0.16] (data not shown).

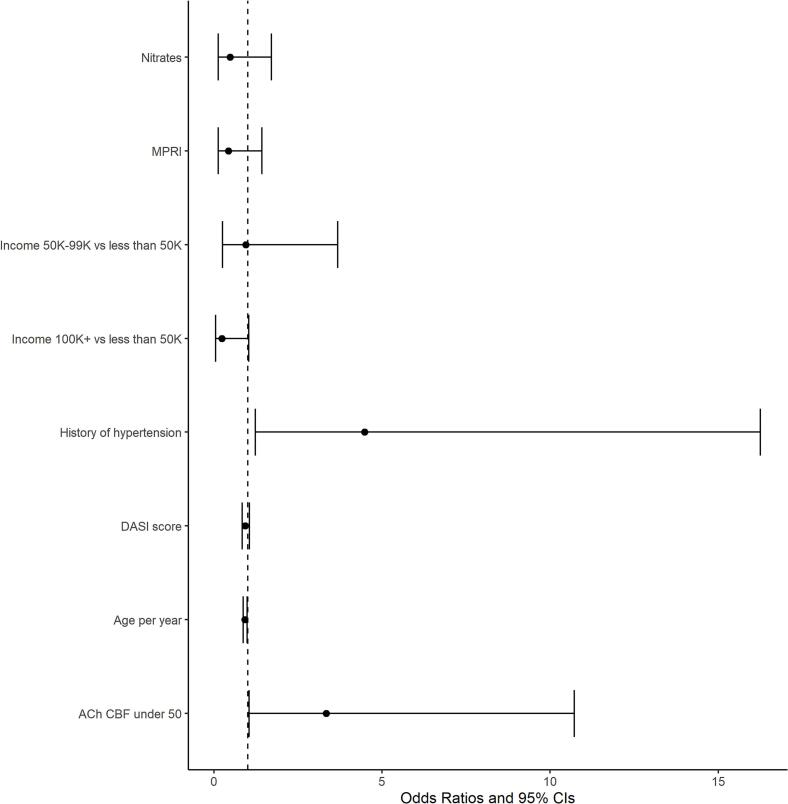

3.3. Predictors of refractory angina

In a multivariable logistic regression modelling, the presence of hypertension (odds ratio [OR] 4.48; 95 % confidence interval (CI) 1.23–16.25; p = 0.02) and abnormal CBF response (OR 3.34; 95 % CI 1.04–10.72; p = 0.04) were significantly associated with refractory angina (Fig. 3). A model with an interaction to test whether the combination of hypertension and abnormal CBF response was different from one factor alone did not show a significant difference in the odds ratio for refractory angina (p = 0.4121).

Fig. 3.

Multivariable logistic regression of predictors of refractory angina based on baseline characteristics among women with coronary function testing (n = 94).

MPRI: Myocardial perfusion reserve index; K: increments of thousand US dollars, DASI: Duke Activity Status Inventory; ACh CBF under 50: CBF of ≤50 % in response to acetylcholine.

In addition, age-adjusted logistic regression modelling demonstrated that a lack of improvement or change in the SAQ domain of physical limitation predicted abnormal CBF response (OR 0.93, 95 % CI 0.88–0.98, p = 0.006). There were no significant associations between abnormal CBF response and remaining domains of the SAQ, including angina stability, angina frequency, treatment satisfaction, or disease perception.

4. Discussion

In this multicenter study involving women with INOCA we found a significant burden of disease, with one-third of participants continuing to exhibit refractory angina at 1-year follow-up. Women with refractory angina had significantly lower functional status, lower incomes, higher proportion of hypertension, and greater nitrate use at 1-year. The majority of individuals with refractory angina have more abnormal CFT pathways. Importantly compared to women with non-refractory symptoms, baseline CBF response to ACh provocation was lower in women with refractory angina, with nearly 75 % demonstrating evidence of abnormality. Hypertension and blunted CBF response of ≤50 % to ACh independently predicted a ∼ 4-fold increased risk for refractory angina at 1-year follow-up. These findings suggest mechanistic roles for hypertension and endothelial-dependent microvascular dysfunction and identify potential treatment targets to reduce angina burden in INOCA.

Additionally, using SAQ-7, we demonstrate a lack of improvement in the subdomain of physical limitation was associated with the presence of endothelial-dependent microvascular dysfunction (abnormal CBF) at 1-year follow-up. Furthermore, while the changes between baseline and 1-year were significantly different between those with refractory and non-refractory angina in the remaining SAQ subdomains, these were not associated with abnormal baseline CBF measurements. SAQ subdomain use may be useful to evaluate persistent symptoms in this population, which often remains challenging in the clinical setting.

4.1. Underlying pathophysiology of INOCA

INOCA is a broad term that emphasizes the significance of coronary syndromes beyond obstructive epicardial CAD, with multiple incompletely understood mechanisms. We and others have described that coronary vasomotor dysfunction is common in patients with INOCA, with over three quarters having microvascular and/or vasospastic angina [1,19,20]. Clinically, INOCA is difficult to diagnose, as there are no convenient modalities that can assess the coronary microvasculature. When compared to the reference standard of invasive CFT, traditional non-invasive stress tests have only 41 % sensitivity and 57 % specificity to predict coronary vasomotor dysfunction [21]. This is likely due to limitations in the different non-invasive imaging modalities, as well as complex disease pathways that can contribute to coronary vasomotor dysfunction, including non-endothelial dependent micro/macrovascular dysfunction, endothelial-dependent micro/macrovascular dysfunction, and micro/macrovascular coronary vasospasm [[22], [23], [24]].

In recent years, CMRI techniques have been successfully used to evaluate physiological surrogates of the microvasculature with contrast-enhanced first-pass myocardial perfusion imaging [18]. Using adenosine to induce hyperemia, semi-quantitative measurements of the MPRI have been validated to evaluate the vasodilating capacity of small vessels [18]. We have previously demonstrated in symptomatic subjects with no obstructive CAD, but evidence of coronary microvascular dysfunction, that changes in angina, as measured by SAQ-7, correlated with changes in MPRI, indicating that symptoms are related to ischemia in this population [25].

In our current study, between women with refractory angina and those without, as well as between baseline and 1-year follow-up scans, there was no significant difference in MPRI. This may be due to the use of adenosine as a pharmacological stress agent, which predominately evaluates only the pathway of non-endothelial dependent vascular relaxation through direct stimulation of smooth muscle cells [10].

Although the absolute differences in blood pressure between groups were modest—driven primarily by diastolic BP—hypertension was significantly more prevalent among women with refractory angina and remained independently associated with persistent symptoms in multivariable analysis. This finding is consistent with prior studies in patients with angina and no obstructive coronary artery disease (ANOCA), which have reported a higher prevalence of hypertension in those with vasomotor dysfunction compared to those without (39 % vs. 7 %, p = 0.02) [26], suggesting a potential mechanistic role for elevated blood pressure. We have also previously shown that coronary microvascular function improves with ACE-I therapy in women with INOCA, and that this is associated with a reduction in anginal symptoms [27]. Additionally, many commonly prescribed antianginal therapies—such as beta-blockers, calcium channel blockers, and nitrates—have blood pressure–lowering effects, supporting the relevance of hemodynamic modulation in symptom management.

Despite these associations, we acknowledge that the blood pressure differences observed in our cohort were small, with wide standard deviations that limit the ability to draw definitive conclusions about clinical impact. The management of refractory angina in INOCA is inherently complex and likely involves multiple, overlapping mechanisms beyond blood pressure control alone. To further investigate therapeutic strategies in INOCA, the ongoing WARRIOR trial (NCT03417388) is evaluating whether intensive medical therapy—including statins, aspirin, and an ACE-inhibitor or ARB—compared to usual care, can reduce major adverse cardiovascular events in women with this condition [28,29].

Finally, the most striking result of our study is that the majority of women with refractory angina had evidence of endothelial-dependent microvascular dysfunction, which may represent an underlying vasospastic mechanism. This aligns with growing recognition that a substantial proportion of patients with ANOCA have epicardial or microvascular spasm, for which endothelial dysfunction may be a key pathophysiological driver. In a prospective study of 111 patients with ANOCA who underwent invasive coronary function testing, coronary vasomotor dysfunction was identified in 86 % of participants, with the vast majority (97 %) having either epicardial or microvascular spasm, while isolated impaired microvascular dilatation to adenosine was rare, occurring in only 3 % of cases [26]. These findings may explain why there was a specific relationship between refractory angina and endothelial-dependent microvascular dysfunction in our study population, and not the other pathways.

The pathogenesis of coronary vasospasm, while not fully elucidated, is thought to be due to an interplay between endothelial-dependent dysfunction and vascular smooth muscle cell hyperreactivity [30]. In healthy endothelium, acetylcholine stimulates the release of nitric oxide, mediating vascular smooth muscle relaxation and increased blood flow. However, at high doses or in patients with endothelial-dependent dysfunction, acetylcholine directly stimulates vascular smooth muscle cell, causing vasoconstriction that can precipitate epicardial and/or microvascular spasm [30]. Studies have shown that women with suspected INOCA have elevated rates of repeat angiography triggered by refractory symptoms, and were four times more likely than men to be readmitted within 180 days with acute coronary syndrome/angina [1]. This further suggests that coronary vasospasm may be the predominant endotype for women with refractory angina, despite having normal findings on routine diagnostic investigations, as vasospasm is both a recognized etiology for INOCA and its acute counterpart, myocardial infarction with no obstructive coronary arteries (MINOCA) [31,32]. Although vasospasm was not formally tested in our cohort, we address this limitation and acknowledge that further studies are needed to confirm this mechanistic pathway.

4.2. Limitations

At the time of this study, high dose acetylcholine provocation for coronary vasospasm was not used as part of the CFT protocol. Therefore, we cannot the confirm the presence of coronary vasospasm in this cohort. Additionally, the relatively small sample size likely limited the statistical power to find a significant difference in MPRI between women with refractory angina and those without. Clinically, however, there are mixed endotypes for INOCA, with patients shown to have abnormalities in both endothelial and non-endothelial dependent pathways [19]. Larger sample sizes would allow for deeper phenotyping of patients with refractory angina.

Furthermore, while our multivariable regression analysis identified statistically significant predictors of refractory angina, the wide confidence intervals observed for these associations reflect a level of uncertainty in the effect size estimates. This may be due to the sample size constraints in the subgroup analyses. As such, our findings should be considered hypothesis-generating and warrant confirmation in larger, prospective studies.

5. Conclusions

There is a relatively high burden of refractory angina in a large proportion of women with suspected INOCA at 1-year follow-up. Women with refractory angina are more likely to have abnormal coronary blood flow response to acetylcholine provocation, suggesting a mechanistic role for endothelial-dependent microvascular dysfunction as a treatment target. Ongoing research is needed to test the hypothesis that statin and ACE-I/ARB treatment can improve quality of life through reduction of refractory angina, as well as reduce major adverse cardiac events.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Judy M. Luu: Writing – review & editing, Writing – original draft. Janet Wei: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Chrisandra Shufelt: Writing – review & editing. Anum Asif: Writing – review & editing. Benita Tjoe: Writing – review & editing. Galen Cook-Wiens: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Eileen M. Handberg: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. Puja K. Mehta: Writing – review & editing. Jenna Maughan: Writing – review & editing. Daniel S. Berman: Writing – review & editing. Louise E.J. Thomson: Writing – review & editing. Carl J. Pepine: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization. C. Noel Bairey Merz: Writing – review & editing, Visualization, Validation, Supervision, Software, Resources, Project administration, Investigation, Funding acquisition, Conceptualization.

Ethical statement

The study was performed under an Institutional Review Board approved protocol in accordance with guidelines for human subjects in research. All patient subjects provided informed consent to participate in this study. All authors attest that this work is original and not under consideration for publication elsewhere.

Funding sources

Aspects of this work were supported by funding from the National Institute of Aging (No. R21 AG077715-01A1) and via contracts from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institutes, Nos. N01-HV-68161, N01-HV-68162, N01-HV-68163 and N01-HV-68164, and grants from the Gustavus and Louis Pfeiffer Research Foundation, Denville, New Jersey, The Women's Guild of Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles, California, The Ladies Hospital Aid Society of Western Pennsylvania, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania and QMED, Inc., Laurence Harbor, New Jersey. This work is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, the National Institutes of Health, or the US Department of Health and Human Services.

Declaration of competing interest

The author is an Editorial Board Member/Editor-in-Chief/Associate Editor/Guest Editor for [American Heart Journal Open: Research and Practice] and was not involved in the editorial review or the decision to publish this article.

The authors declare the following financial interests/personal relationships which may be considered as potential competing interests: Dr. C. Noel Bairey Merz serves as Board of Director for iRhythm, fees paid through CSMC from Abbott Diagnostics and SHL Telemedicine. Dr. Janet Wei served on an advisory board for Abbott Vascular. CJP serves as the Editor-in-Chief of AHJO.

References

- 1.Bairey Merz C.N., Pepine C.J., Walsh M.N., Fleg J.L. Ischemia and No Obstructive Coronary Artery Disease (INOCA): developing evidence-based therapies and research agenda for the next decade. Circulation. 2017;135(11):1075–1092. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.024534. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jespersen L., Hvelplund A., Abildstrøm S.Z., et al. Stable angina pectoris with no obstructive coronary artery disease is associated with increased risks of major adverse cardiovascular events. Eur. Heart J. 2012;33(6):734–744. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Maddox T.M., Ho P.M., Roe M., Dai D., Tsai T.T., Rumsfeld J.S. Utilization of secondary prevention therapies in patients with nonobstructive coronary artery disease identified during cardiac catheterization: insights from the National Cardiovascular Data Registry Cath-PCI registry. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2010;3(6):632–641. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.906214. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaw L.J., Bairey Merz C.N., Pepine C.J., et al. Insights from the NHLBI-sponsored Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study: part I: gender differences in traditional and novel risk factors, symptom evaluation, and gender-optimized diagnostic strategies. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2006;47(3, Supplement):S4-s20 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.01.072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jespersen L., Abildstrøm S.Z., Hvelplund A., Prescott E. Persistent angina: highly prevalent and associated with long-term anxiety, depression, low physical functioning, and quality of life in stable angina pectoris. Clin. Res. Cardiol. 2013;102(8):571–581. doi: 10.1007/s00392-013-0568-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Johnson B.D., Shaw L.J., Pepine C.J., et al. Persistent chest pain predicts cardiovascular events in women without obstructive coronary artery disease: results from the NIH-NHLBI-sponsored Women’s Ischaemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) study. Eur. Heart J. 2006;27(12):1408–1415. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehl040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gallone G., Baldetti L., Tzanis G., et al. Refractory angina: from pathophysiology to new therapeutic nonpharmacological technologies. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020;13(1):1–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2019.08.055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ford T.J., Stanley B., Good R., et al. Stratified medical therapy using invasive coronary function testing in angina: the CorMicA trial. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2018;72(23, Part A):2841-2855 doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Jansen Tijn P.J., Konst Regina E., Annemiek de Vos, et al. Efficacy of diltiazem to improve coronary vasomotor dysfunction in ANOCA. JACC Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2022;15(8):1473–1484. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmg.2022.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Quesada O., AlBadri A., Wei J., et al. Design, methodology and baseline characteristics of the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation-Coronary Vascular Dysfunction (WISE-CVD) Am. Heart J. 2020;220:224–236. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2019.11.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hlatky M.A., Boineau R.E., Higginbotham M.B., et al. A brief self-administered questionnaire to determine functional capacity (the Duke Activity Status Index) Am. J. Cardiol. 1989;64(10):651–654. doi: 10.1016/0002-9149(89)90496-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kimble L.P., Dunbar S.B., Weintraub W.S., et al. The Seattle angina questionnaire: reliability and validity in women with chronic stable angina. Heart Dis. 2002;4(4):206–211. doi: 10.1097/00132580-200207000-00002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan P.S., Jones P.G., Arnold S.A., Spertus J.A. Development and validation of a short version of the Seattle angina questionnaire. Circ. Cardiovasc. Qual. Outcomes. 2014;7(5):640–647. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.114.000967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Spertus J.A., Winder J.A., Dewhurst T.A., et al. Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire: a new functional status measure for coronary artery disease. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 1995;25(2):333–341. doi: 10.1016/0735-1097(94)00397-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spertus J.A., Jones P.G., Maron D.J., et al. Health-status outcomes with invasive or conservative care in coronary disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020;382(15):1408–1419. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1916370. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Guimarães W.V.N., Nicz P.F.G., Garcia-Garcia H.M., et al. Seattle angina pectoris questionnaire and Canadian Cardiovascular Society angina categories in the assessment of total coronary atherosclerotic burden. Am. J. Cardiol. 2021;152:43–48. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2021.04.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Spertus J.A., Jones P., McDonell M., Fan V., Fihn S.D. Health status predicts long-term outcome in outpatients with coronary disease. Circulation. 2002;106(1):43–49. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000020688.24874.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thomson L.E.J., Wei J., Agarwal M., et al. Cardiac magnetic resonance myocardial perfusion reserve index is reduced in women with coronary microvascular dysfunction. A National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute-sponsored study from the Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation. Circ. Cardiovasc. Imaging. 2015;8(4) doi: 10.1161/circimaging.114.002481. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ford T.J., Yii E., Sidik N., et al. Ischemia and no obstructive coronary artery disease: prevalence and correlates of coronary vasomotion disorders. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2019;12(12) doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.119.008126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ford T.J., Corcoran D., Berry C. Stable coronary syndromes: pathophysiology, diagnostic advances and therapeutic need. Heart. 2018;104(4):284–292. doi: 10.1136/heartjnl-2017-311446. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cassar A., Chareonthaitawee P., Rihal C.S., et al. Lack of correlation between noninvasive stress tests and invasive coronary vasomotor dysfunction in patients with nonobstructive coronary artery disease. Circ. Cardiovasc. Interv. 2009;2(3):237–244. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.108.841056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Chen C., Wei J., AlBadri A., Zarrini P., Bairey Merz C.N. Coronary microvascular dysfunction - epidemiology, pathogenesis, prognosis, diagnosis, risk factors and therapy. Circ J. 2016;81(1):3–11. doi: 10.1253/circj.CJ-16-1002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.AlBadri A., Bairey Merz C.N., Johnson B.D., et al. Impact of abnormal coronary reactivity on long-term clinical outcomes in women. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol. 2019;73(6):684–693. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.11.040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ford T.J., Ong P., Sechtem U., et al. Assessment of vascular dysfunction in patients without obstructive coronary artery disease: why, how, and when. JACC Cardiovasc. Interv. 2020;13(16):1847–1864. doi: 10.1016/j.jcin.2020.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bairey Merz C.N., Handberg E.M., Shufelt C.L., et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of late Na current inhibition (ranolazine) in coronary microvascular dysfunction (CMD): impact on angina and myocardial perfusion reserve. Eur. Heart J. 2016;37(19):1504–1513. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehv647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Konst R.E., Damman P., Pellegrini D., et al. Vasomotor dysfunction in patients with angina and nonobstructive coronary artery disease is dominated by vasospasm. Int. J. Cardiol. 2021;333:14–20. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2021.02.079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pauly D.F., Johnson B.D., Anderson R.D., et al. In women with symptoms of cardiac ischemia, nonobstructive coronary arteries, and microvascular dysfunction, angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibition is associated with improved microvascular function: a double-blind randomized study from the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute Women’s Ischemia Syndrome Evaluation (WISE) Am. Heart J. 2011;162(4):678–684. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2011.07.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Handberg E.M., Merz C.N.B., Cooper-Dehoff R.M., et al. Rationale and design of the Women’s Ischemia Trial to Reduce Events in Nonobstructive CAD (WARRIOR) trial. Am. Heart J. 2021;237:90–103. doi: 10.1016/j.ahj.2021.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Women'’s IschemiA TRial to Reduce Events In Non-ObstRuctive CAD - Full Text View - Clinicaltrials.gov Accessed February 23, 2023. https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03417388

- 30.Hubert A., Seitz A., Pereyra V.M., Bekeredjian R., Sechtem U., Ong P. Coronary artery spasm: the interplay between endothelial dysfunction and vascular smooth muscle cell hyperreactivity. Eur Cardiol. 2020;15 doi: 10.15420/ecr.2019.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lindahl B., Baron T., Erlinge D., et al. Medical therapy for secondary prevention and long-term outcome in patients with myocardial infarction with nonobstructive coronary artery disease. Circulation. 2017;135(16):1481–1489. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.116.026336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Barr P.R., Harrison W., Smyth D., Flynn C., Lee M., Kerr A.J. Myocardial infarction without obstructive coronary Artery Disease is Not a Benign Condition (ANZACS-QI 10) Heart Lung Circ. 2018;27(2):165–174. doi: 10.1016/j.hlc.2017.02.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]