Abstract

Introduction

The TITAN study examined changes in productivity, ability to work, and quality of life (QoL) before and after treatment with the high-efficacy therapy natalizumab (TYSABRI®) in patients with multiple sclerosis (MS) in France.

Methods

Patients, aged ≥ 18 and < 65 years with relapsing-remitting MS, either naïve to natalizumab or with ≤ 1 prior natalizumab infusion, with paid employment, were evaluated for productivity (number of working hours) in the 12 months prior to and after natalizumab initiation. Changes in annualized relapse rate and Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score were assessed. Changes in work status, working ability, physical and psychologic functioning, and QoL were also evaluated.

Results

Of 185 enrolled patients, the primary analysis population comprised 162 patients with a mean (SD) age of 36.8 (9.6) years and a baseline mean (SD) EDSS score of 1.9 (1.4). Annual mean (SD) productivity (n = 160) decreased from 1284.4 (503.3) h before natalizumab to 1208.0 (575.3) h (p = 0.05) in the year after natalizumab initiation. Significant improvement was seen in overall activity impairment at 6, 12, and 18 months of natalizumab treatment (p < 0.001). Decreases in annualized relapse rate (p < 0.0001) and EDSS score (p < 0.05) were observed during this period. In addition, treatment-related improvements were observed in presenteeism (reduced work efficiency), overall work impairment, and absenteeism (p < 0.05); significant improvements in psychological and physical impact (p ≤ 0.01) of MS were reported.

Conclusions

These findings suggest that early treatment with natalizumab may improve the work function of patients with MS, thereby decreasing the economic burden of the disease and improving patient quality of life.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40120-025-00725-x.

Keywords: COVID-19, MSIS-29, Relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis, Work productivity, WPAI-MS

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Multiple sclerosis (MS) negatively impacts work productivity for both people with MS and their caregivers. Treatment with the high-efficacy disease-modifying therapy, natalizumab, may improve work productivity and the ability to work for people with MS |

| What did the study ask?/What was the hypothesis of the study? |

| This observational, open-label, multicenter study assessed the impact of natalizumab treatment on the ability to work and productivity of employed people with MS in France |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Overall work impairment and overall activity impairment decreased with natalizumab treatment, and people with MS on natalizumab reported reduced physical and psychologic impact of MS |

| These findings suggest that early treatment with natalizumab may improve the work function of patients with MS, thereby decreasing the economic burden of the disease and improving patient QoL |

Introduction

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is the leading progressive neurologic condition in young people of working age [1, 2]. In a survey of patients with MS in France, 81% reported that MS negatively impacted work productivity [3]. Impairments in patient and/or caregiver work productivity (absenteeism and presenteeism [reduced work efficiency]) were reported to account for over half of the indirect and non-medical costs of MS in the US [2, 4]. Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) have been shown to positively impact the working ability of patients with MS, with high-efficacy DMTs having a greater impact [5].

One high-efficacy DMT is natalizumab (TYSABRI®; Biogen), a monoclonal antibody against α4-integrin [6]. The efficacy of natalizumab in treating relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) has been documented in both clinical trial data [7, 8] and real-world studies [9–11]. Unlike other DMTs, natalizumab has a rapid onset of clinical and radiologic efficacy, with improvements noted as early as 1 month after treatment initiation [12, 13]. Likewise, patients have reported improved quality of life (QoL) as early as 3 months after natalizumab initiation [14].

In several studies of patients with MS in Europe, treatment with natalizumab was shown to be beneficial to work productivity [15–20]. In patients with MS in France, studies have shown that natalizumab is an efficacious treatment [21]; however, data regarding productivity and ability to work for natalizumab-treated patients in France are lacking.

TITAN, an observational, open-label, multicenter, comparative study, was undertaken to assess the impact of natalizumab on the ability to work and productivity of employed patients with RRMS in France. Here, we report results from the TITAN study, including changes in productivity, ability to work, and QoL before and after natalizumab treatment.

Methods

Study Design

Enrolled patients, aged ≥ 18 and < 65 years, with a diagnosis of RRMS, either naïve to natalizumab or with ≤ 1 prior natalizumab infusion, were included if they had a paid full-time (in France, 35 h per week) or part-time job, including patients on short-term (< 6 months) sick leave. Patients who planned cessation of work for the upcoming year for reasons other than MS (e.g., parental leave, retirement, or sabbatical) or were part of an interventional study protocol for another medication were excluded from the TITAN study. All patients gave informed consent to participate.

Patients were followed for 18 months after natalizumab initiation. Retrospective and prospective data were collected from patient medical files and via computer-assisted telephone interviews with patients and caregivers (Supplementary Table S1). In computer-assisted telephone interviews (Supplementary Methods), patients reported the following information: start and end dates of work periods, percentage of time employed during work periods (100% was considered full time), number of hours worked per week (according to 100% contract, smoothed for self-employed people), start and end dates of therapeutic half-time, proportion of time worked during therapeutic half-time, whether the therapeutic half-time was linked to MS, start and end dates of sick leave, and whether the sick leave was related to MS. An ad hoc questionnaire (Supplementary Methods) on patients’ professional activities during the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic was completed by the patients and used in sensitivity analyses of productivity outcomes.

The TITAN study was approved by the French Consultative Committee on Data Processing in Health Research, approved by the French Expert Committee on Health Research, Studies, and Evaluations (Comité Consultatif sur le Traitement de l’Information en matière de Recherche dans le domaine de la Santé [CCTIRS]), and authorized by the French Data Protection Commission. The study was conducted in accordance with local French laws, including the French Data Protection Act (Informatique et Libertés) and French Expert Committee on Health Research, Studies, and Evaluations (Comité d’Expertise pour les Recherches, les Etudes et les Evaluations dans le domaine de la Santé [CEREES]).

Endpoints

The primary endpoint was the change in productivity with natalizumab, defined as the difference between the number of hours worked in the 12-month period before and the 12-month period after natalizumab initiation. Secondary endpoints included productivity in the 6-month period after treatment initiation and the 18-month period after treatment initiation.

Patient-reported secondary endpoints included change in the ability to work, measured with the Work Productivity and Activity Impairment–Multiple Sclerosis (WPAI-MS) questionnaire [22], and change in the QoL, measured via the Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29) [23] and the 3-Level EuroQol–5 dimensions (EQ-5D-3L) index score [24, 25]. The WPAI-MS, MSIS-29, and EQ-5D-3L were administered at baseline and at 6, 12, and 18 months after natalizumab initiation.

Clinician-assessed secondary endpoints included changes in annualized relapse rate (ARR) and the Expanded Disability Status Scale (EDSS) score. Relapse rates were calculated from physician case reports for the 12-month period preceding natalizumab initiation and after 6, 12, and 18 months of treatment. EDSS scores were assessed at treatment initiation and 6, 12, and 18 months after initiation.

Statistical Analysis

All analyses at 12 months were carried out in patients with corresponding data at baseline (defined as the 12-month period before natalizumab initiation or the last assessment before natalizumab initiation) and 12-month assessments. Patient characteristics, employment, and work productivity at baseline and at each assessment point were summarized descriptively (e.g., mean, standard deviation, minimum, maximum, median). The number of hours worked was calculated for each period of activity in theoretical working time [(number of hours/week and paid leave) minus (time on sick leave over the period)]. Annualized values for productivity are reported for all treatment periods.

Comparisons before and after natalizumab initiation were made using paired data tests. For paired quantitative variables, the data were evaluated for normal distribution with a graphic examination and a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Student’s t test for paired data was used to test for changes in the mean. For analysis of subgroups based on the change in EDSS score over the course of treatment, worsening was defined as an increase in the EDSS score: ≥ 1.5 compared with a baseline score of 0.0, ≥ 1.0 compared with a baseline score of 1.0–5.5, or ≥ 0.5 compared with a baseline score of ≥ 6.0. An improvement was defined as a decrease in the EDSS score of ≥ 1.0 compared with a baseline score of ≥ 2.0.

Results

Participants

Between 14 June 2017 and 23 December 2019, 185 patients were prospectively enrolled at 30 investigator sites throughout France (Supplementary Tables S2 and S3). The primary analysis population comprised 162 patients who completed telephone interviews at baseline and 12 months (Supplementary Fig. S1). Of these patients, 155 (95.7%) continued with follow-up for 18 months.

Patients included in the primary analysis had a mean (SD) age of 36.8 (9.6) years, and 76.5% were female (Table 1). The mean (SD) EDSS scores at diagnosis and at natalizumab initiation were 1.4 (1.3) and 1.9 (1.4), respectively. Most patients (80.6%) experienced relapses in the 12 months before natalizumab initiation, with just under half of patients (48.1%) reporting only one relapse in that period. Over two-thirds (68.3%) of patients had received treatment for MS in the prior 12 months.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of the primary analysis population

| Characteristics | Total (N = 162) |

|---|---|

| Female sex, n (%) | 124 (76.5) |

| Age at baseline, years, mean (SD) | 36.8 (9.6) |

| Presence of ≥ 1 comorbidity, n (%) | 33 (20.4) |

| Duration of MS at baseline, years, mean (SD) | 5 (5.7) |

| EDSS score at diagnosis,a mean (SD) | 1.4 (1.3) |

| EDSS score at baseline,b mean (SD) | 1.9 (1.4) |

| Number of relapses in the 12 months prior to inclusion, n (%)c | |

| 0 | 31 (19.4) |

| 1 | 77 (48.1) |

| 2 | 39 (24.4) |

| 3 and more | 13 (8.1) |

| At least one MS treatment in the 12 months prior to inclusion,d n (%) | 110 (68.3) |

EDSS Expanded Disability Status Scale, MS multiple sclerosis

aMean (SD) calculated from patients with EDSS data at diagnosis (n = 112)

bMean calculated from patients with EDSS data at baseline (n = 157)

cPercentages calculated per the number of patients with data (n = 160)

dPercentages calculated per the number of patients with data (n = 161)

At enrollment, all patients had a paid job. At the first phone interview, 98.8% of patients remained employed, with most patients (81.3%) having a contract for permanent employment (Table 2). Patients were salaried in the private (58.0%) or public (34.4%) sector. Over three-quarters (77.7%) of patients reported working full time. The mean (SD) number of weekly hours worked was 33.6 (8.1) h. Two-thirds of patients (66.0%) reported ≥ 1 period of sick leave during the year preceding natalizumab initiation, with only 1 period of sick leave for 66 patients, 2 for 24 patients, and ≥ 3 for 17 patients.

Table 2.

Baseline employment of the primary analysis population

| Type of employment | Total (N = 162) |

|---|---|

| Paid job, n (%) | 158 (98.8)a |

| Professional category, n (%)b | |

| Craftsman, shopkeeper, entrepreneur | 8 (5.1) |

| Intermediate occupation | 3 (1.9) |

| Executive, engineer, liberal profession | 36 (22.9) |

| Employee | 108 (68.8) |

| Worker | 2 (1.3) |

| Employee type, n (%)b | |

| Private sector employee | 91 (58.0) |

| Public sector employee | 54 (34.4) |

| Self-employed | 9 (5.7) |

| Other | 3 (1.9) |

| Type of contract, n (%)c | |

| Open-ended contract | 117 (81.3) |

| Fixed-term contract | 19 (13.2) |

| Other (temporary worker, intermittent) | 8 (5.6) |

| Number of worked hours (per week), mean (SD)b | 33.6 (8.1) |

aAt enrollment all patients had a paid job

bPercentages calculated per the number of employed patients with data (n = 157)

cPercentages calculated per the number of employed patients with data (n = 144)

Of the 155 patients with detailed infusion data, the mean (SD) number of infusions was 15.9 (4.6). At treatment initiation, one-third of patients (54/162) had a physician’s sick leave note for receiving the monthly infusion of natalizumab, whereas 23.5% (38/162) adapted their working hours, and 41.4% (67/162) received their infusions during non-worked days (compensated or uncompensated leave). Through 18 months of follow-up, 29 patients reported discontinuation of natalizumab; the most frequently reported reasons for discontinuation included planned pregnancy (31.0%), adverse events (17.2%), increased risk of progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (17.2%), and John Cunningham virus-positive serology (17.2%).

Annual Productivity and Sick Leave

Productivity (number of hours worked) in the 12 months before and after initiation of natalizumab was assessed in the 160 patients with productivity data. The mean (SD) productivity in the 12 months before natalizumab initiation was 1284.4 (503.3) h. Mean (SD) productivity in the 12 months after natalizumab initiation decreased to 1208.0 (575.3) h (p = 0.05; Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Work productivity 12 months before and after natalizumab initiation. A Twelve months before and 12 months after natalizumab initiation and B mean annual productivity before natalizumab initiation (n = 160), after natalizumab initiation in the pre-COVID-19 period (n = 160), and after natalizumab initiation during the COVID-19 period (n = 49). COVID-19 coronavirus disease 2019

In patients who completed 12 months of uninterrupted treatment with natalizumab (n = 149), annual mean (SD) productivity before natalizumab initiation was 1297.5 (491.4) h. The mean (SD) productivity decreased to 1208.9 (578.3) h at 12 months of treatment (p = 0.04).

Because of potential confounding of results by the COVID-19 pandemic, an ad hoc analysis was conducted to evaluate productivity between natalizumab initiation and the date of the first COVID-19-related lockdown in France (15 March 2020) and during the lockdown until the 12-month assessment point. Annual mean (SD) productivity between natalizumab initiation and the beginning of lockdown was 1224.9 (576.3) h (n = 160), whereas annual mean (SD) productivity during the lockdown through 12 months after natalizumab initiation was 808.3 (669.4) h (n = 49; Fig. 1B).

An exploratory analysis examined annual productivity in subgroups of patients based on changes in EDSS score from baseline to the 12-month assessment (n = 133) during natalizumab treatment (Table 3). For patients with stable EDSS scores (n = 101) at 12 months of treatment, mean (SD) annualized productivity decreased by 76.9 (483.5) h. For patients with EDSS worsening (n = 9) at 12 months, mean (SD) annualized productivity was reduced by 315 (441.2) h. In contrast, for patients with EDSS improvement (n = 21) at 12 months, mean (SD) annualized productivity increased by 190.7 (562.6) h.

Table 3.

Work productivity before or after natalizumab in subgroups based on the change in EDSS score

| No change (n = 103) | Deterioration of EDSS (n = 9) | Improvement in EDSS (n = 21) | Primary population (N = 162) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline productivity, hours | ||||

| n | 102 | 9 | 21 | 160 |

| Mean (SD) | 1346.4 (509.3) | 1155.4 (586.1) | 1163.9 (536.5) | 1284.4 (503.3) |

| Productivity at 12 months, hours | ||||

| n | 102 | 9 | 21 | 160 |

| Mean (SD) | 1272.5 (560.2) | 840.4 (660.3) | 1354.6 (546.1) | 1208 (575.3) |

| Change in productivity at 12 months, hours/year | ||||

| n | 101 | 9 | 21 | 159 |

| Mean (SD) | − 76.9 (483.5) | − 315.0 (441.2) | 190.7 (562.6) | − 78.2 (500.3) |

Twenty-nine of 162 patients had no data on the change in EDSS score (2 missing EDSS scores at baseline, 26 missing at 12 months, and 1 missing at baseline and 12 months)

EDSS Expanded Disability Status Scale

In the primary analysis population, productivity was assessed at 6 months and 18 months after natalizumab initiation. Mean (SD) annual productivity decreased from 1284.4 (503.3) h to 1236.9 (580.8) h at 6 months after natalizumab initiation (n = 160; p < 0.0001). Of the 155 patients who completed follow-up at 18 months, 153 patients had data at natalizumab initiation and at 18-month follow-up. The mean (SD) annual productivity significantly decreased from 1282.4 (510.7) h to 1195 (573.3) h (p < 0.001). In the ad hoc analysis between natalizumab initiation and the start of the lockdown, annual mean (SD) productivity was 1206.7 (581.6) h (n = 153), whereas from the lockdown to the 18-month assessment, annual mean (SD) productivity was 965.2 (661.8) h (n = 76).

A sensitivity analysis examined the change in mean annual productivity in the subset of patients with sick leave related to MS in the year before treatment. Mean (SD) annual productivity was stable in these patients (1298 [504.3] h before natalizumab initiation and 1247.1 [573.8] h after 12 months of treatment; p = 0.17). At 12 months, the proportion of patients having ≥ 1 period of sick leave was equivalent to the proportion with any sick leave at baseline (64.2% vs. 66% at baseline); however, the proportion of patients with ≥ 3 periods of sick leave increased (19.1% vs. 10.5% at baseline).

Work Productivity and Activity Impairment

Immediately before natalizumab initiation, patients reported a mean (SD) of 25.3% (42.1) absenteeism (time missed from work), 25.2% (28.5) presenteeism (reduced work efficiency), 26.4% (29.1) overall work impairment, and 37% (31.1) overall activity impairment via the WPAI-MS questionnaire. At every timepoint after natalizumab initiation, decreases in impairment (i.e., improvements) were seen in absenteeism, presenteeism, overall work impairment, and overall activity impairment (Fig. 2). Compared with timepoints before natalizumab initiation, patients reported significant improvements in all WPAI outcomes at 6 months after treatment initiation. At 12 months, improvement was noted in overall activity impairment (26.3% [27.8], p < 0.001)—in absenteeism, presenteeism, and overall work impairment. At 18 months after natalizumab initiation, significant improvements were reported in all WPAI outcomes except absenteeism.

Fig. 2.

WPAI-reported changes in work impairment before and after natalizumab treatment. p values calculated using Student’s t-tests for paired series. WPAI-MS Work Productivity and Activity Impairment-Multiple Sclerosis

Quality of Life

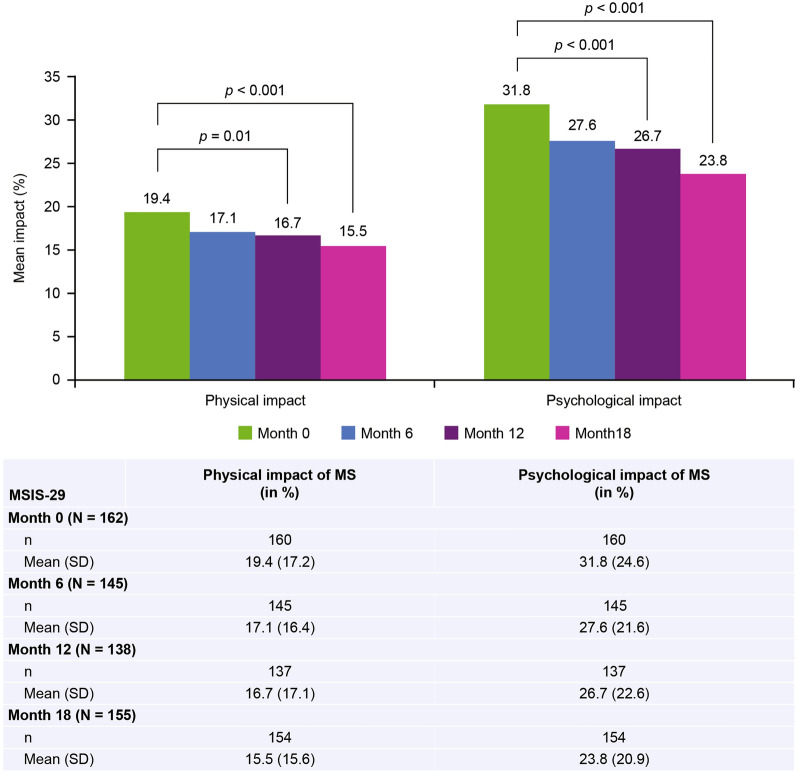

At baseline, the mean (SD) psychologic impact score of RRMS as assessed by the MSIS-29 was 31.8 (24.6). At 12 and 18 months of treatment, the mean (SD) psychologic impact score decreased (improved) to 26.7 (22.6) and 23.8 (20.9), respectively (p < 0.001 for both timepoints). At baseline, the mean (SD) physical impact score of RRMS as assessed by the MSIS-29 was 19.4 (17.2) and decreased to 16.7 (17.1; p = 0.01) at 12 months of treatment and to 15.5 (15.6; p < 0.001) at 18 months of treatment (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Change in physical and psychologic impact of MS after treatment with natalizumab (MSIS-29). MS multiple sclerosis, MSIS-29 Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale

Quality of life (QoL) was also assessed with the EQ-5D-3L. The mean (SD) EQ-5D-3L index score was 0.8 (0.2) before natalizumab initiation (n = 160) and remained stable at 0.8 (0.2) at six (n = 144) and 12 months (n = 138) of natalizumab treatment (p = 0.26 at 12 months). No significant change in the EQ-5D-3L index was observed through 18 months of follow-up (n = 153), with a mean (SD) at 18 months of 0.7 (0.2; p = 0.13).

Clinical Outcomes

The ARR decreased from a mean (SD) of 1.2 (0.9) before natalizumab initiation to 0.0 (0.2) at 6 months, 0.1 (0.3) at 12 months, and 0.1 (0.5) at 18 months into natalizumab treatment (p < 0.0001 for all; Fig. 4). The mean (SD) EDSS at inclusion (n = 157) was 1.9 (1.4) and decreased, following natalizumab treatment, to 1.6 (1.4) at 6 months (n = 146; p = 0.001). EDSS was significantly lower at baseline compared to at 12 months of treatment (1.6 [1.4], n = 135; p = 0.002) and at 18 months of treatment (1.7 [1.5], n = 131; p = 0.02). Among patients for whom change could be calculated, most had no change from their baseline EDSS score at 6 months (79.3% [115/145]), 12 months (77.4% [103/133]), and 18 months (77.5% [100/129]). At 18 months, 14.7% (19/129) of patients had improvement in EDSS scores from baseline, whereas 7.8% (10/129) of patients showed worsening of EDSS scores.

Fig. 4.

Change in ARR before and after natalizumab treatment. Baseline ARR was calculated for the 12 months prior to natalizumab initiation. ARR at month 6 and month 18 were adjusted to annual rates. ARR annualized relapse rate

Discussion

Although the annual productivity either decreased or was maintained for French patients with RRMS who received natalizumab in the TITAN study, significant improvements were observed in working ability and in the patient-reported physical and psychologic impact of MS. These improvements were seen within 6 months of natalizumab initiation. Likewise, patient functioning improved and stabilized with significant decreases from baseline in both ARR and mean EDSS scores at 6, 12, and 18 months.

The decrease in work productivity initially observed during this study was complicated by the COVID-19 lockdown in France. In patients who had follow-up visits 12 months before the COVID-19 lockdown (n = 105), stable annual work productivity was observed following natalizumab treatment. However, work productivity after the lockdown was substantially decreased, suggesting that this reduction in productivity at 12 months (observed in the primary endpoint analysis) may be related to the lockdown—impacted by limited access to outpatient care, and not natalizumab treatment.

A significant decrease in mean work productivity was observed at 6 months after natalizumab initiation. Most patients completed the 6-month follow-up before the onset of the COVID-19 lockdown; therefore, the change in productivity observed at 6 months cannot be solely explained by the lockdown.

The patterns of productivity observed in the TITAN study may reflect the baseline characteristics of enrolled patients. Whereas 54.9% of French patients with MS reported working full time [26], in the TITAN study, 77.7% of patients reported working full time. Patients in TITAN had high baseline annual work productivity, possibly contributing to a ceiling effect. TITAN patients were at an early stage of their disease, with low EDSS scores (mean 1.9 at baseline) and few relapses in the year before natalizumab initiation. The high level of function of enrolled patients may have limited room for improvement in work productivity hours. In the exploratory analysis, when patients were stratified by change in EDSS score, increased productivity was observed in patients with improved EDSS scores over the first year of natalizumab treatment, suggesting that change in productivity may reflect response to natalizumab.

In the TITAN study, patients with sick leave at baseline reported stable productivity after natalizumab initiation. This may be explained by the lower level of disability in patients in the TITAN study (mean EDSS score, 1.9) compared with patients in a previous study examining the work productivity of patients in Sweden (mean EDSS score, 2.9) [16]. In the Wickstrom et al. study, those with sick leave in the year before natalizumab (mean EDSS score, 3.3) reported increased productivity in the year after natalizumab initiation. In contrast, those without sick leave prior to treatment (mean EDSS score, 2.5) reported no increase in working hours but reported improvements in mental ability and decreased fatigue after natalizumab initiation. In patients with a lower level of disability, change in working ability may be a more sensitive measure of treatment efficacy than change in productivity. Furthermore, while improvements in EDSS may contribute to better work performance, other factors such as cognitive or fatigue-related symptoms (which are not captured by EDSS) could potentially impair productivity [27].

In TITAN, significant decreases in presenteeism (i.e., improvements in working ability) were reported. Presenteeism is a prevalent problem in MS. In prior studies, approximately half of working patients with RRMS or clinically isolated syndrome reported work impairment with presenteeism, reporting presenteeism as a problem at three times the rate of absenteeism [28, 29]. Glanz et al. reported significant associations of presenteeism with increased fatigue, depression, anxiety, and reduced QoL [28]. Although TITAN did not assess fatigue in patients with MS, previous studies have reported improvement in fatigue after natalizumab treatment [30–33].

Consistent with other studies examining WPAI and MSIS-29, natalizumab-treated patients in the TITAN study also reported significant improvements in overall activity impairment and overall work impairment as well as in the physical and psychologic impact of MS. Patients with MS in Italy reported natalizumab-associated improvements in all WPAI domains, with significant improvements in absenteeism, overall work impairment, and physical and psychologic impact of MS [19]. Likewise, a 4-year study of patients treated with natalizumab reported significant improvements in overall activity impairment and MSIS-29 physical and psychologic scales [11]. The current study assessed natalizumab-associated changes in work and patient-reported outcomes at 6 months after natalizumab initiation. Improvements in the physical and psychologic impact of MS assessed with MSIS-29 have previously been reported at 3 months after natalizumab initiation [34].

Limitations of this study include the open-label, single-armed nature of the research and the lack of a comparator group. Another limitation is the possibility of a ceiling effect in measuring work productivity in patients in the early stages of MS. However, these patients constitute a small subset of those receiving natalizumab in France [35]. Additionally, retrospective and prospective data collection was limited by the availability of records and the accuracy of patient reports. Assessment of work productivity was made using patient-provided data from computer-assisted telephone interviews. Patients were encouraged to use the AMELI website (a French online health insurance portal), which provides an accurate record of the patient’s periods of sick leave, to overcome bias associated with this type of data collection (e.g., memory bias or desirability bias). Lastly, this study was complicated by the disruption of work activities during the COVID-19 lockdown period.

Though natalizumab treatment has typically been given to patients with higher EDSS scores than those seen in the patients in this study [36, 37], the knowledge that earlier treatment with natalizumab benefits patient function and work ability may result in the use of natalizumab in populations with less baseline disability. This observation aligns with recent findings that earlier natalizumab treatment results in better outcomes than later treatment initiated with natalizumab [38].

Conclusions

A small but significant decrease in productivity, partially attributed to the COVID-19 lockdown, was observed in the year following natalizumab initiation. Notably, within 6 months of natalizumab initiation, patients in France reported improved work function, as noted by decreases in absenteeism, presenteeism, overall work impairment, and overall activity impairment. Patients also reported decreased impact of MS on their physical and psychologic function. These improvements were maintained at 18 months of follow-up. These findings suggest that early treatment with natalizumab may improve the work function of patients with MS, thereby decreasing the economic burden of the disease and improving patient QoL.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank all patients and neurologists who took part in the study. All named authors meet the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors criteria for authorship of this manuscript and take responsibility for the integrity of the work as a whole.

Medical Writing/Editorial Assistance

Under the direction of the authors, medical writing and editorial support for the development of this manuscript was provided by Holly Engelman, PhD, of Ashfield MedComms, an Inizio Company; editorial support was provided by Cara Farrell of Excel Scientific Solutions. The authors had full editorial control of the manuscript and provided their final approval of all content. Biogen reviewed and provided feedback on the manuscript to the authors. The authors provided final approval of all content.

Author Contributions

Patrick Vermersch: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—review & editing. Arnaud Kwiatkowski: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—review & editing. Jérôme de Sèze: Writing—review & editing. Alain Créange: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—review & editing. Nathalie Texier: Conceptualization, Formal Analysis, Visualization, Writing—review & editing. Sophie Fantoni-Quinton: Conceptualization, Writing—review & editing. Marilyn Gros: Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Marta Ruiz: Conceptualization, Project administration, Writing—original draft, Writing—review & editing. Christine Lebrun-Frenay: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing—review & editing.

Funding

This study was supported by Biogen. Biogen will also be funding the journal’s Rapid Service Fee.

Data Availability

Individual participant data collected during the trial may be shared after anonymization and on approval of the research proposal. Biogen commits to sharing patient-level data, study-level data, CSRs, and protocols with qualified scientific researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal. Biogen reviews all data requests internally based on the review criteria and in accordance with our Clinical Trial Transparency and Data Sharing Policy. Deidentified data and documents will be shared under agreements that further protect against participant reidentification. To request access to data, please visit https://vivli.org/.

Declarations

Conflict of Interest

Patrick Vermersch: personal compensation for consulting from AB Science, Biogen, BMS-Celgene, Imcyse, Merck, Novartis, Roche, Sanofi, and Teva. Honoraria and support for meetings from Biogen, Janssen, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi. Research grants from Merck, Sanofi, and Roche. Arnaud Kwiatkowski: personal compensation for consulting from Biogen, Merck, Novartis. Honoraria from Biogen, Merck, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi; for meetings from Biogen, Janssen, Novartis, Roche, and Sanofi; for participation in advisory board from Novartis. Alain Créange: grants or contracts from Alexion, Biogen, BMS, Merck, Novartis, and Roche. Honoraria and support for meetings from Alexion, Biogen, and Novartis. Payment for expert testimony from Merck. Marilyn Gros and Marta Ruiz: employees of and may hold stock and/or stock options in Biogen. Nathalie Texier, Jérôme de Sèze, Christine Lebrun-Frenay and Sophie Fantoni-Quinton have nothing to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The TITAN study was approved by the French Consultative Committee on Data Processing in Health Research; approved by the French Expert Committee on Health Research, Studies, and Evaluations (Comité Consultatif sur le Traitement de l’Information en matière de Recherche dans le domaine de la Santé [CCTIRS]); and authorized by the French Data Protection Commission. The study was conducted in accordance with local French laws, including the French Data Protection Act (Informatique et Libertés) and French Expert Committee on Health Research, Studies, and Evaluations (Comité d’Expertise pour les Recherches, les Etudes et les Evaluations dans le domaine de la Santé [CEREES]).

Footnotes

Prior Presentation: 6-month interim analysis: JNLF 2021 Virtual Meeting; May 26–28, 2021. 12-month primary analysis: ECTRIMS 2021 Virtual Meeting; October 13–15, 2021.

References

- 1.Dobson R, Giovannoni G. Multiple sclerosis—a review. Eur J Neurol. 2019;26(1):27–40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bebo B, Cintina I, LaRocca N, et al. The economic burden of multiple sclerosis in the United States: estimate of direct and indirect costs. Neurology. 2022;98(18):e1810–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lebrun-Frenay C, Kobelt G, Berg J, et al. New insights into the burden and costs of multiple sclerosis in Europe: results for France. Mult Scler. 2017;23(2_suppl):65–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Battaglia MA, Bezzini D, Cecchini I, et al. Patients with multiple sclerosis: a burden and cost of illness study. J Neurol. 2022;269(9):5127–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen J, Taylor BV, Blizzard L, et al. Effects of multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapies on employment measures using patient-reported data. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2018;89(11):1200–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Biogen Inc. TYSABRI (natalizumab) [prescribing information]. 2023. https://www.tysabri.com/content/dam/commercial/tysabri/pat/en_us/pdf/tysabri_prescribing_information.pdf. Accessed Apr 2023.

- 7.Polman CH, O’Connor PW, Havrdova E, et al. A randomized, placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(9):899–910. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Miller DH, Soon D, Fernando KT, et al. MRI outcomes in a placebo-controlled trial of natalizumab in relapsing MS. Neurology. 2007;68(17):1390–401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Butzkueven H, Kappos L, Wiendl H, et al. Long-term safety and effectiveness of natalizumab treatment in clinical practice: 10 years of real-world data from the Tysabri Observational Program (TOP). J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2020;91(6):660–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Perumal J, Balabanov R, Su R, et al. Natalizumab in early relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis: a 4-year, open-label study. Adv Ther. 2021;38(7):3724–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Perumal J, Balabanov R, Su R, et al. Improvements in cognitive processing speed, disability, and patient-reported outcomes in patients with early relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis treated with natalizumab: results of a 4-year, real-world, open-label study. CNS Drugs. 2022;36(9):977–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Miller DH, Khan OA, Sheremata WA, et al. A controlled trial of natalizumab for relapsing multiple sclerosis. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(1):15–23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kappos L, O’Connor PW, Polman CH, et al. Clinical effects of natalizumab on multiple sclerosis appear early in treatment course. J Neurol. 2013;260(5):1388–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Stephenson JJ, Kern DM, Agarwal SS, et al. Impact of natalizumab on patient-reported outcomes in multiple sclerosis: a longitudinal study. Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Olofsson S, Wickstrom A, Häger Glenngård A, Persson U, Svenningsson A. Effect of treatment with natalizumab on ability to work in people with multiple sclerosis: productivity gain based on direct measurement of work capacity before and after 1 year of treatment. BioDrugs. 2011;25(5):299–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wickstrom A, Nyström J, Svenningsson A. Improved ability to work after one year of natalizumab treatment in multiple sclerosis. Analysis of disease-specific and work-related factors that influence the effect of treatment. Mult Scler. 2013;19(5):622–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wickström A, Dahle C, Vrethem M, Svenningsson A. Reduced sick leave in multiple sclerosis after one year of natalizumab treatment. A prospective ad hoc analysis of the TYNERGY trial. Mult Scler. 2014;20(8):1095–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kreimendahl F, Rychlik RP, Patel S, Gleissner E, Becker V. Working ability and monetarily valued productivity of patients with multiple sclerosis treated with natalizumab. Value Health. 2014;17(7):A400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Capra R, Morra VB, Mirabella M, et al. Natalizumab is associated with early improvement of working ability in relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis patients: WANT observational study results. Neurol Sci. 2021;42(7):2837–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Achtnichts L, Zecca C, Findling O, et al. Correlation of disability with quality of life in patients with multiple sclerosis treated with natalizumab: primary results and post hoc analysis of the TYSabri ImPROvement study (PROTYS). BMJ Neurol Open. 2023;5(1): e000304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bigaut K, Fabacher T, Kremer L, et al. Long-term effect of natalizumab in patients with RRMS: TYSTEN cohort. Mult Scler. 2021;27(5):729–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reilly MC, Zbrozek AS, Dukes EM. The validity and reproducibility of a work productivity and activity impairment instrument. Pharmacoeconomics. 1993;4(5):353–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hobart J, Lamping D, Fitzpatrick R, Riazi A, Thompson A. The Multiple Sclerosis Impact Scale (MSIS-29) a new patient-based outcome measure. Brain. 2001;124(5):962–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):337–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chevalier J, de Pouvourville G. Valuing EQ-5D using time trade-off in France. Eur J Health Econ. 2013;14(1):57–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bouleau A, Dulong C, Schwerer CA, et al. The socioeconomic impact of multiple sclerosis in France: results from the PETALS study. Mult Scler J Exp Transl Clin. 2022;8(2):1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Schiavolin S, Leonardi M, Giovannetti AM, et al. Factors related to difficulties with employment in patients with multiple sclerosis: a review of 2002–2011 literature. Int J Rehabil Res. 2013;36(2):105–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glanz BI, Dégano IR, Rintell DJ, et al. Work productivity in relapsing multiple sclerosis: associations with disability, depression, fatigue, anxiety, cognition, and health-related quality of life. Value Health. 2012;15(8):1029–35. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Chen J, Taylor B, Palmer AJ, et al. Estimating MS-related work productivity loss and factors associated with work productivity loss in a representative Australian sample of people with multiple sclerosis. Mult Scler. 2019;25(7):994–1004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Putzki N, Yaldizli O, Tettenborn B, Diener HC. Multiple sclerosis associated fatigue during natalizumab treatment. J Neurol Sci. 2009;285(1–2):109–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Iaffaldano P, Viterbo RG, Paolicelli D, et al. Impact of natalizumab on cognitive performances and fatigue in relapsing multiple sclerosis: a prospective, open-label, two years observational study. PLoS ONE. 2012;7(4): e35843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Svenningsson A, Falk E, Celius EG, et al. Natalizumab treatment reduces fatigue in multiple sclerosis. Results from the TYNERGY trial; a study in the real life setting. PLoS ONE. 2013;8(3):e58643. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilken J, Kane RL, Sullivan CL, et al. Changes in fatigue and cognition in patients with relapsing forms of multiple sclerosis treated with natalizumab: the ENER-G study. Int J MS Care. 2013;15(3):120–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kamat SA, Rajagopalan K, Stephenson JJ, Agarwal S. Impact of natalizumab on patient-reported outcomes in a clinical practice setting: a cross-sectional survey. Patient. 2009;2(2):105–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Outteryck O, Ongagna JC, Brochet B, et al. A prospective observational post-marketing study of natalizumab-treated multiple sclerosis patients: clinical, radiological and biological features and adverse events. The BIONAT cohort Eur J Neurol. 2014;21(1):40–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Melin A, Outteryck O, Collongues N, et al. Effect of natalizumab on clinical and radiological disease activity in a French cohort of patients with relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis. J Neurol. 2012;259(6):1215–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.van Pesch V, Sindic CJ, Fernández O. Effectiveness and safety of natalizumab in real-world clinical practice: review of observational studies. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2016;149:55–63. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ontaneda D, Mowry EM, Newsome SD, et al. Benefits of early treatment with natalizumab: a real-world study. Mult Scler Relat Disord. 2022;68: 104216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Individual participant data collected during the trial may be shared after anonymization and on approval of the research proposal. Biogen commits to sharing patient-level data, study-level data, CSRs, and protocols with qualified scientific researchers who provide a methodologically sound proposal. Biogen reviews all data requests internally based on the review criteria and in accordance with our Clinical Trial Transparency and Data Sharing Policy. Deidentified data and documents will be shared under agreements that further protect against participant reidentification. To request access to data, please visit https://vivli.org/.