Abstract

Introduction

Research investigating the differences in determinants affecting the quality of life (QoL) in patients with acute ischemic stroke (AIS) of varying severities remains limited, and how these factors influence QoL remains unclear. The aim of this study was to address this critical issue, refining treatments to enhance long-term QoL and optimize resource use.

Methods

In this multicenter prospective study conducted in China, patients with AIS were assessed using the EuroQol-5 Dimension (EQ-5D) questionnaire at admission and 1 year later. Univariate and multivariate analyses were conducted to identify QoL determinants. Motor function-related outcomes (MFRO) and non-motor function-related outcomes (NMFRO) were defined based on the EQ-5D questionnaire to explore how factors influence outcomes through mediation analysis.

Results

The study included 8598 patients with AIS (median age 64 years; 65.7% male), 3927 of whom had minor stroke severity (National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] scores ≤ 3). The median QoL score improved from 0.597 at admission to 1.000 after 1 year. Compared to patients with minor stroke, more patients with non-minor stroke had non-motor function-related problems (NMFRP) at admission (78.2% vs. 56.6%). Age, stroke history, QoL at admission, infection, hospitalization costs, and discharge outcomes were found to be factors influencing QoL in both cohorts. In the non-minor stroke cohort, analysis revealed that additional factors include diabetes mellitus, geographical region, speech impairment, and thrombolysis, while in the minor stroke cohort, hypertension, coronary heart disease, cancer, prolonged length of stay, and hemorrhage were found to be relevant factors. The impact of most factors on QoL was mediated by MFRO, while the effects of age, speech impairment, and geographical region were also mediated by NMFRO. Hospitalization costs beyond 15,000 China Yuan (CNY) did not improve QoL for the patients with non-minor stroke, with a threshold of 10,000 CNY for the patients with minor stroke.

Conclusions

Over half of the patients in the study population had NMFRP, necessitating greater medical attention. Patients with different stroke severities had distinct QoL determinants. Age, speech impairment, and geographical region may exert an impact partly mediated through NMFRO. Higher hospitalization costs did not consistently improve QoL beyond a certain threshold.

Trial Registration

ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02470624.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s40120-025-00743-9.

Keywords: Acute ischemic stroke, Determinants, Quality of life, Social economy, Non-motor function related problems

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| The factors influencing quality of life (QoL) in patients with different stroke severities remain unclear. Also, the role of non-motor function-related problems (NMFRP) in affecting these determinants has yet to be fully elucidated |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Over half of the patients in the study population experienced NMFRP, warranting greater attention |

| QoL determinants differed by stroke severity, with age, speech impairment, and geographical region partially mediated through NMFRP |

| Higher hospitalization costs did not consistently enhance QoL beyond a certain threshold |

Introduction

Stroke is one of the most common causes of death and disability worldwide, resulting in macroeconomic losses estimated at 2.059 trillion US dollars, approximately 1.66% of the global gross domestic product. Among stroke categories, ischemic stroke (IS) accounts for 85–87% of all cases, causing macroeconomic losses of 964 billion US dollars worldwide—nearly half of the total stroke-related economic impact [1–3].

Previous studies have often used mobility and disability as metrics to evaluate the prognosis of IS, as assessed especially using the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score and Barthel Index (BI), which focus primarily on motor function-related outcomes (MFRO) [4, 5]. However, these scales often fail to represent the full effect of disease due to the ceiling effects of these scales and the non-motor function-related outcomes (NMFRO) of IS [4]. Therefore, outcome evaluation based on quality of life (QoL) was established to address these limitations, with previous studies reporting that QoL could be influenced by factors such as age, sex, race, Medicaid recipients, income, smoking, diabetes mellitus (DM), atrial fibrillation (AF), stroke history, stroke severity, visual field defects, and extremity weakness [4, 6–14]. However, some limitations remain in these studies, such as short-term clinical outcomes often being limited to no more than 3 months [4, 7, 9–11], cross-sectional observational study design [12], a few research centers with a limited number of participants [4, 9, 12, 13], and the inclusion of various stroke types, such as hemorrhagic stroke being included in the analysis [6, 8, 10–12, 14], all of which severely diminish the robustness of conclusions. QoL analyses based on data from the Chinese population are even scarcer. Minor stroke, defined as a National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale [NIHSS] score ≤ 3 in terms of severity, constitutes the majority of IS cases [15, 16]. However, the factors influencing QoL in patients with minor stroke, and how these differ from those in patients with more severe stroke, have yet to be explored in large cohort studies. Furthermore, it remains unclear whether these factors influence QoL through MFRO or NMFRO and what the proportions of their specific contribution are.

Systematically exploring the factors influencing IS and understanding how these factors affect QoL may serve as a cornerstone for refining treatments, enhancing patient well-being, and improving cost-effectiveness while optimizing resource utilization. In this study, we aimed to identify the factors of QoL in patients with acute IS (AIS) across various stroke severities and to explore how these factors influence QoL through either MFRO or NMFRO.

Methods

Study Design

The Chinese Acute Ischemic Stroke Treatment Outcome Registry (CASTOR) trial was a multicenter, prospective clinical trial that enrolled 10,002 patients with AIS from 80 hospitals across 44 cities in mainland China. The study protocol has been described in detail elsewhere [17]. All participating hospitals were required to have a neurology ward admitting > 100 patients with stroke annually. Included patients had to meet the following criteria: (1) age ≥ 18 years; (2) diagnosis of AIS, as confirmed by computed tomography (CT) or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) between May 2015 and October 2017; and (3) admission to a hospital within 7 days of AIS onset. Patients with primary hemorrhagic stroke were excluded from the study. Additionally, due to the considerable impact of thrombectomy on stroke outcomes and the limited number of patients undergoing thrombectomy in this study, this patient population was excluded from the analysis to ensure the robustness of our conclusions [18]. All treatments and diagnoses followed the recommendations of the Chinese Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Acute Ischemic Stroke [19]. Prior to the study's commencement, the research staff responsible for outcome measurement underwent training on data collection tools, assessments, and reporting procedures. All data were gathered utilizing electronic Case Report Forms and an online Electronic Data Capture system, consistent with the prevailing clinical practices. Throughout the study, the sponsor and a third-party Contract Research Organization conducted regular site audit visits to verify compliance with study documentation, reporting procedures, and the study protocol. All data management and supervision had to adhere to the Standard Operating Procedures for Good Clinical Practice Guidelines [17].

Ethical Approval and Informed Consent

The study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02470624) was a multicenter study approved by a centralized independent institutional review board (Ethical Board of Peking University First Hospital; Ethical Number: 2015[922]; Master of the Ethical Board: Prof. Xiaohui Guo), with additional local institutional review board approvals obtained where requested (per institute) [17]. The participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidelines were strictly followed, and the privacy of the participants was rigorously safeguarded.

Explanatory Variables

All participants underwent standard assessments, which included the following: demographics (age and sex); medical history (stroke, including IS and hemorrhagic stroke; hypertension; DM; coronary heart disease [CHD], defined as any history of heart attack, myocardial infarction, angina, or CHD; AF; cancer); hospital characteristics (level and geographic region); and clinical features. Clinical features included the NIHSS score at admission; length of stay (LOS); intensive care unit (ICU) admission; in-hospital complications, including infection (urinary tract infection, lung infection, and other locations) and hemorrhage (gastrointestinal hemorrhage, urinary tract hemorrhage, dermal ecchymosis, and hemorrhagic transformation of IS); hospitalization costs (degree 1: ≤ 10,000 China Yuan [CNY]; degree 2: 10,001–15000 CNY; degree 3: > 15,000 CNY); and functional outcomes at discharge (good outcome: mRS score ≤ 2) [4, 20–22]. Geographic regions in China were categorized into the eastern area, the northeastern area, the central area, and the western area according to regional economic development level [20]. Minor stroke severity was defined as a NIHSS score ≤ 3. Data on stroke symptoms were collected, and the involvement of three functional domains (speech, motor, and sensory impairments) was determined based on the NIHSS score [23]. Prolonged length of stay (PLOS) was defined as LOS exceeding 14 days, based on the median LOS reported in previous studies [24–26].

The EuroQol five-dimensions (EQ-5D) questionnaire was used to assess patients’ QoL according to protocol [17]. The score at admission was referred to as the baseline for adjusting QoL. The primary outcome was the score 1 year after admission. The assessment methods were primarily consistent with those used in previous studies, and the EuroQol five-dimensions-three-level (EQ-5D-3L) version was chosen as the questionnaire scale because it has already been developed for Chinese utility values [17, 27–30]. The EQ-5D questionnaire includes the mobility, self-care, activity, pain/discomfort, and anxiety/depression dimensions with 3 levels (level 1: no problems/symptom-free; level 2: some problems; level 3: extreme problems) for each dimension, defining 243 possible health states. These five dimensions are combined to determine an index value (QoL score) ranging from - 0.59 (state worse than death) to 0 (state equal to death) to 1 (perfect state of health) [31]. The domains of mobility, self-care, and usual activities were used to evaluate MFRO, and the domains of pain/discomfort and anxiety /depression were used to evaluate NMFRO. The value of each domain was used to quantify MFRO and NMFRO [17, 27–30]. The QoL at admission was evaluated through a face-to-face interview, and the QoL at 1 year after admission was evaluated by telephone interview.

Statistical Analysis

Continuous variables are reported as the mean ± standard deviation or median with interquartile range, and were analyzed using Student’s t-test or the Wilcoxon rank-sum test, depending on the distribution. Categorical variables are expressed as frequencies (percentages) and were analyzed using the chi-squared test. A multivariate analysis was conducted with a multiple linear regression model employing the “backward” method. The stepwise procedure included all covariates mentioned above, with significance levels set at p < 0.05 for inclusion and p > 0.1 for exclusion [10, 20, 32, 33]. Multicollinearity was evaluated by variance inflation factor. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using multivariable analysis with a multiple linear regression model employing the “input” method to ensure the robustness of the results. Subgroup analyses were performed, stratified by patient gender. Mediation analysis was carried out using model 4 from Hayes' PROCESS v3.5, drawing on 5000 bootstrap samples to establish a 95% confidence interval [34–36]. The sums of motor function-related and non-motor function-related domains were calculated as mediators to evaluate how QoL factors exert their impact through influencing MFRO and NMFRO. All QoL factors identified through multivariate analysis were included in the mediation analysis. A p value of 0.05 (two-tailed) was considered to be indicative of significance. All statistical analyses were performed with the IBM SPSS 26.0 software package (SPSS IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA).

Results

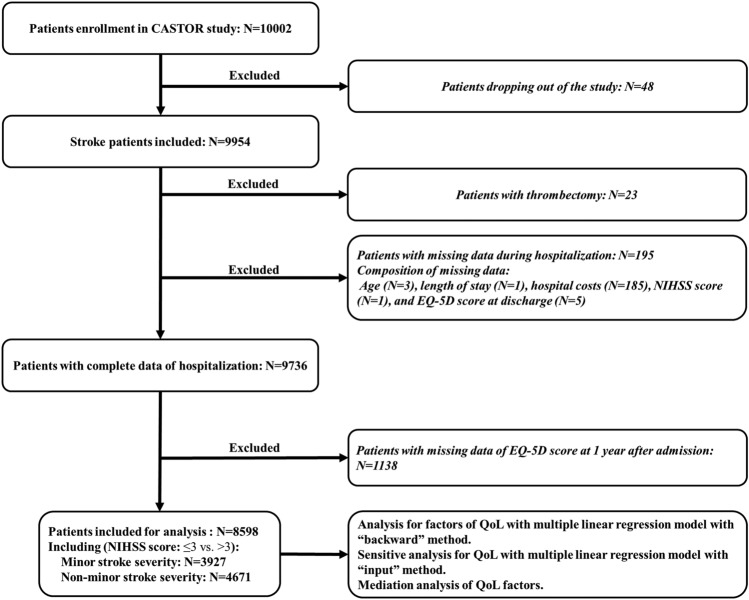

Of the 10,002 patients initially screened for eligibility, 8598 patients were included in the final analysis after exclusion (Fig. 1). The median age of the overall cohort was 64.0 (IQR 56.0–73.0) years, and 5648 (65.7%) participants were male. A total of 193 patients (2.2%) died during the study period. As shown in Table 1, 3927 (45.7%) patients were assessed with minor stroke severity, and 4671 (54.3%) patients were assessed with non-minor stroke severity. Compared with the minor stroke cohort, patients with non-minor stroke were more likely to be female, older, and to have a medical history of stroke, CHD, and/or AF. They also tended to be hospitalized in tertiary hospitals; have speech, motor, and sensory impairments; experience longer hospital stays; have higher rates of ICU admission, in-hospital infection, and hemorrhage; and have higher hospitalization costs, worse QoL at admission, and worse functional outcome at discharge. (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

Flowchart for study inclusion. EQ-5D EuroQol five-dimensions questionnaire, NIHSS National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale, QoL quality of life

Table 1.

Basic characteristics of the minor stroke and non-minor stroke cohorts

| Variables | Minor stroke cohort (n = 3927) | Non-minor stroke cohort (n = 4671) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Male sex, n (%) | 2670 (68.0%) | 2978 (63.8%) | < 0.001 |

| Older age (≥ 65 years), n (%) | 1805 (46.0%) | 2364 (50.6%) | < 0.001 |

| Medical history | |||

| - Stroke, n (%) | 863 (22.0%) | 1206 (25.8%) | < 0.001 |

| - Hypertension, n (%) | 2505 (63.8%) | 3037 (65.0%) | 0.236 |

| - Diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 1005 (25.6%) | 1206 (25.8%) | 0.811 |

| - CHD, n (%) | 506 (12.9%) | 705 (15.1%) | 0.003 |

| - Atrial fibrillation, n (%) | 116 (3.0%) | 252 (5.4%) | < 0.001 |

| - Cancer, n (%) | 113 (2.9%) | 106 (2.3%) | 0.075 |

| Geographical region, n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| - The eastern area | 1782 (45.4%) | 2162 (46.3%) | |

| - The northeastern area | 1114 (28.4%) | 1116 (23.9%) | |

| - The central area | 792 (20.2%) | 1094 (23.4%) | |

| - The western area | 239 (6.1%) | 299 (6.4%) | |

| Tertiary hospital, n (%) | 3534 (90.0%) | 4341 (92.9%) | < 0.001 |

| QoL at admission, median (ICR) | 0.783 (0.604, 0.887) | 0.411 (0.114, 0.597) | < 0.001 |

| Speech impairment, n (%) | 1269 (32.3%) | 3643 (78.0%) | < 0.001 |

| Motor impairment, n (%) | 2390 (60.9%) | 4582 (98.1%) | < 0.001 |

| Sensory impairment, n (%) | 672 (17.1%) | 1744 (37.3%) | < 0.001 |

| Prolonged length of stay (> 14 days), n (%) | 704 (17.9%) | 1629 (34.9%) | < 0.001 |

| ICU, n (%) | 83 (2.1%) | 228 (4.9%) | < 0.001 |

| Intravenous thrombolysis, n (%) | 107 (2.7%) | 275 (5.9%) | < 0.001 |

| In-hospital complications, n (%) | |||

| - Infection | 156 (4.0%) | 425 (9.1%) | < 0.001 |

| - Hemorrhage | 52 (1.3%) | 112 (2.4%) | < 0.001 |

| Hospitalization costs (CNY), n (%) | < 0.001 | ||

| - Degree 1 (≤ 10,000) | 1140 (29.0%) | 826 (17.7%) | |

| - Degree 2 (10,001–15000) | 1162 (29.6%) | 998 (21.4%) | |

| - Degree 3 (> 15,000) | 1625 (41.4%) | 2847 (61.0%) | |

| Good outcome at discharge (mRS score ≤ 2), n (%) | 3638 (92.6%) | 2499 (53.5%) | < 0.001 |

| QoL 1 year after admission, median (ICR) | 1.000 (0.875, 1.000) | 0.862 (0.610, 1.000) | < 0.001 |

CHD coronary heart disease, CNY China Yuan, ICU intensive care unit, IQR interquartile range, mRS modified Rankin Scale, QoL quality of life

aComparison between minor and non-minor stroke cohorts

The distribution of each domain in the different cohorts is presented in Fig. 2A, B. Compared to patients assessed with minor stroke severity, a higher proportion of patients assessed with non-minor stroke severity exhibited non-motor function-related problems (NMFRP) at admission (total: 78.2% vs. 56.6%; pain and discomfort: 65.7% vs. 44.8%; anxiety or depression: 65.8% vs. 39.0%). Throughout the entire follow-up period, NMFRO accounted for a significantly greater proportion of the QoL decline in the minor stroke severity cohort compared to the non-minor stroke severity cohort, indicating that NMFRO had a more pronounced impact on the minor stroke severity cohort (at admission: 38.3% vs. 27.0%; at 1 year after admission: 27.5% vs. 21.8%). During the follow-up period, improvements in NMFRO were more pronounced compared to improvements MFRO in both cohorts (Fig. 2C, D).

Fig. 2.

Changes in EQ-5D score during the follow-up. A, B Distribution of each domain in the two cohorts (minor stroke severity cohort and non-minor stroke severity cohort). C, D Mean penalty scores across EQ-5D domains were calculated for each cohort during follow-up, with higher scores reflecting greater impairment in the respective domain. The color-coded percentages represent the relative reduction in penalty points between time intervals, with larger values indicating more substantial improvements in domain-specific health status. EQ-5D EuroQol five-dimensions questionnaire

Given the significant variations between the patient cohorts with minor and non-minor stroke severity, respectively, we further examined the factors influencing QoL across these cohorts to gain deeper insights into strategies for improving QoL (Table 1). The results of the univariate and multivariable analyses of QoL across the different cohorts are presented in Fig. 3 and Electronic Supplementary Material (ESM) Table S1. Across the different cohorts, patients with poorer QoL were generally older, had a history of stroke, and had experienced complications from infections. These patients also tended to have a lower QoL at admission and poorer outcomes at discharge. Higher hospitalization costs did not consistently improve QoL beyond a certain threshold. These thresholds may be 10,000 CNY for the minor stroke severity cohort and 15,000 CNY for the non-minor stroke severity cohort. In the non-minor stroke severity cohort, patients with poorer QoL were more likely to have diabetes mellitus and speech impairments, and they were less likely to have received intravenous thrombolysis. In the cohort with minor stroke severity, patients with poorer QoL were more likely to have hypertension, CHD, cancer, PLOS, and hemorrhage complications. Geographical region had an influence on QoL in the non-minor stroke severity cohort but not in the minor stroke severity cohort. There was no significant multicollinearity in these models (ESM Table S2). The sensitivity analysis yielded similar results (ESM Table S3). In the subgroup analyses stratified by gender, several determinants—including age, QoL at admission, speech impairment, intravenous thrombolysis, in-hospital infection, and outcome at discharge—exhibited consistent patterns across both male and female cohorts, aligning with the findings observed in the overall cohort comprising both genders (ESM Tables S4, S5).

Fig. 3.

Determinants of quality of life with multivariable analysis grouped by stroke severity. A good outcome was considered to be a modified Rankin scale score ≤ 2. CHD Coronary heart disease, CNY China Yuan, PLOS prolonged length of stay, QoL quality of life.

To further explore how these factors affect QoL in terms of MFRO and NMFRO, we conducted a mediation analysis. The results are presented in Table 2. Nearly all factors impacted patients' QoL from the MFRO perspective, with the proportion of each contribution ranging from 68.4% to 88.8%, indicating a dominant role. However, NMFRO partially mediated the influence of age on QoL, with a higher contribution observed in the non-minor stroke severity cohort. The effect of graphical region on QoL in the non-minor cohort was mainly mediated through NMFRO. Speech impairment and hospitalization costs affected the QoL in patients with non-minor stroke severity through both MFRO and NMFRO pathways.

Table 2.

Mediation analysis for quality of life factors in the minor stroke and non-minor stroke cohorts

| Variables | Mediator | Mediation effect (95% confidence interval)a | Proportion of mediationa |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-minor stroke cohort | |||

| Older age (≥ 65 years) | MFRO | − 0.046 (− 0.057, − 0.035) | 77.4% |

| NMFRO | − 0.013 (− 0.018, − 0.009) | 22.6% | |

| Medical history | |||

| - Stroke | MFRO | − 0.023 (− 0.036, − 0.010) | 82.1% |

| NMFRO | − 0.004 (− 0.010, 0.002) | – | |

| - Diabetes mellitus | MFRO | − 0.017 (− 0.029, − 0.004) | 76.7% |

| NMFRO | − 0.005 (− 0.011, 0.000) | – | |

| Geographical region | |||

| - The central area | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| - The eastern area | MFRO | – | – |

| NMFRO | – | – | |

| - The northeastern area | MFRO | 0.008 (− 0.005, 0.021) | – |

| NMFRO | 0.017 (0.011, 0.022) | 63.7% | |

| - The western area | MFRO | – | – |

| NMFRO | – | – | |

| QoL at admission | MFRO | 0.086 (0.065, 0.105) | 73.0% |

| NMFRO | 0.032 (0.022, 0.041) | 26.9% | |

| Speech impairment | MFRO | − 0.025 (− 0.037, − 0.013) | 72.1% |

| NMFRO | − 0.009 (− 0.014, − 0.004) | 26.1% | |

| Intravenous thrombolysis | MFRO | 0.051 (0.031, 0.071) | 88.8% |

| NMFRO | 0.006 (− 0.004, 0.016) | – | |

| In-hospital complications | |||

| - Infection | MFRO | − 0.064 (− 0.086, − 0.041) | 87.0% |

| NMFRO | − 0.010 (− 0.021, 0.000) | – | |

| Hospitalization costs (CNY) | |||

| - Degree 3 (> 15,000) | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| - Degree 1 (≤ 10,000) | MFRO | 0.009 (− 0.005, 0.023) | – |

| NMFRO | 0.009 (0.003, 0.015) | 46.1% | |

| - Degree 2 (10,001–15000) | MFRO | 0.020 (0.007, 0.032) | 68.4% |

| NMFRO | 0.009 (0.003, 0.014) | 29.5% | |

| Good outcome at discharge | MFRO | 0.156 (0.143, 0.169) | 80.6% |

| NMFRO | 0.035 (0.030, 0.041) | 18.3% | |

| Minor stroke cohort | |||

| Older age (≥ 65 years) | MFRO | − 0.022 (− 0.029, − 0.014) | 77.7% |

| NMFRO | − 0.006 (− 0.010, − 0.002) | 20.9% | |

| Medical history | |||

| - Stroke | MFRO | − 0.021 (− 0.031, − 0.011) | 84.5% |

| NMFRO | − 0.004 (− 0.009, 0.001) | – | |

| - Hypertension | MFRO | − 0.009 (− 0.016, − 0.003) | 75.8% |

| NMFRO | − 0.003 (− 0.007, 0.001) | – | |

| - CHD | MFRO | − 0.009 (− 0.023, 0.004) | – |

| NMFRO | − 0.004 (− 0.010, 0.003) | – | |

| - Cancer | MFRO | − 0.023 (− 0.050, 0.002) | – |

| NMFRO | − 0.006 (− 0.020, 0.007) | – | |

| QoL at admission | MFRO | 0.061 (0.041, 0.083) | 69.9% |

| NMFRO | 0.023 (0.012, 0.034) | 25.7% | |

| PLOS (> 14 days) | MFRO | − 0.008 (− 0.018, 0.003) | – |

| NMFRO | − 0.005 (− 0.011, 0.000) | – | |

| In-hospital complications | |||

| - Infection | MFRO | − 0.029 (− 0.056, − 0.004) | 81.5% |

| NMFRO | − 0.008 (− 0.021, 0.004) | – | |

| - Hemorrhage | MFRO | − 0.038 (− 0.088, 0.008) | – |

| NMFRO | − 0.012 (− 0.039, 0.011) | – | |

| Hospitalization costs (CNY) | |||

| - Degree 3 (> 15,000) | Reference | Reference | Reference |

| - Degree 1 (≤ 10,000) | MFRO | 0.010 (0.003, 0.017) | 74.4% |

| NMFRO | 0.003 (− 0.001, 0.007) | – | |

| - Degree 2 (10,001–15000) | MFRO | – | – |

| NMFRO | – | – | |

| Good outcome at discharge | MFRO | 0.156 (0.132, 0.181) | 78.7% |

| NMFRO | 0.042 (0.029, 0.056) | 21.4% | |

CHD Coronary heart disease, CNY China Yuan, MFRO motor function-related outcome, NMFRO non-motor function-related outcome, PLOS prolonged length of stay, QoL quality of life

a–, Cells with '-' indicate no data due to no significance

Discussion

In this report on our large-scale, multicenter, prospective cohort study, we have presented the characteristics and determinants of QoL 1 year after admission across patient cohorts with varying stroke severity and explored how these factors affected QoL. More than half of patients in the study population have NMFRP. The impact of these NMFRP was significantly greater on the QoL of patients with severe stroke, resulting in substantial deductions, while it was relatively more pronounced on the QoL of patients with minor stroke severity, leading to a higher percentage of deductions attributed to these symptoms. The cohort with minor stroke severity exhibited several differences in determinants of QoL compared to the non-minor stroke severity cohort. In addition, higher hospitalization costs did not consistently improve QoL beyond a certain threshold, which varied by stroke severity. Nearly all factors affected QoL primarily through the mediation of MFRO, while a considerable impact of age, speech impairment, geographical region, and hospitalization costs was mediated by NMFRO. All of these results could serve as a basis for enhancing medical efficiency and improving the QoL of patients.

Determinants Impacting Patients' QoL

Previous studies have explored QoL determinants in patients with minor IS/transient ischemic attack (TIA) or very low QoL, while differences among patients with different stroke severities have rarely been explored [4, 11]. In terms of enhancing patient QoL and improving medical efficiency, it is beneficial to pay attention to distinctive characteristics of stroke and to implement targeted interventions. For example, we found that the QoL of patients in the minor stroke severity cohort may not benefit from PLOS, a finding that was not observed in the non-minor stroke severity cohort. This result is in line with findings reported in previous studies [37]. One potential mechanism for this effect may be that a longer LOS increases the possibility of in-hospital complications, especially pneumonia [37, 38]. A LOS of no more than 14 days for patients with minor stroke severity may benefit patients' QoL and improve medical efficiency. Another noteworthy finding of our study is that intravenous thrombolysis exerted a notable favorable impact on the non-minor stroke severity cohort, but not on the minor stroke severity cohort. A recent clinical trial also reported that dual antiplatelet therapy was not inferior to alteplase for patients with non-disabling minor stroke, with the assessment relying on functional indices [5]. Given the nature of that study, reaching a strong conclusion was challenging, necessitating a well-structured randomized clinical trial to comprehensively examine the impact of intravenous thrombolysis on QoL in individuals with minor stroke severity. Additionally, our findings indicate that geographic region influences the QoL only in patients with severe symptoms, suggesting that cross-regional treatment may be unnecessary for minor stroke cases. The unevenness of medical developments and care across China's vast regions drives patients to seek cross-regional care, exacerbating strains on healthcare resources and economic burden. Encouraging local treatment for mild cases could alleviate these pressures without adversely affecting QoL. The QoL of both patients with non-minor and minor stroke are adversely affected by in-hospital infections. A recent study found that women aged > 85 years with AIS have poorer outcomes, with in-hospital infections significantly contributing to adverse prognosis [39], potentially indicating gender-related variations in the impact of infection on QoL that warrant further investigation. Our subgroup analysis revealed that in-hospital infections adversely affected the QoL in both genders, with a more pronounced impact observed on male patients across both the minor and non-minor stroke cohorts. Future well-designed studies with robust methodologies are warranted to further elucidate gender-specific disparities in factors influencing QoL among patients with AIS.

Non-motor Function-Related Problems

Motor function-related outcomes have been used in prognostic indexes to evaluate patient outcomes in many studies [40, 41]; however, AIS not only impairs patients’ MFRO but also has a great influence on their NMFRO. In a 2-year follow-up study, the adjusted hazard rates for depression among patients with stroke, in comparison to the general reference population, were 8.53 within the first 3 months, 3.84 between 3 months and 1 year, and 1.82 during the second year [42]. Our study revealed that half of the patients experienced NMFRP upon admission, significantly impacting their QoL, as evidenced by a substantial accumulation of penalty points in non-motor function-related domains. Moreover, a previous study reported that patients with AIS with severe symptoms were more likely to develop depression [42]. Our study also yielded similar results. Compared to the patients in the minor stroke severity cohort, those in the non-minor stroke severity cohort experienced worse NMFRO while the impact of NMFRP was relatively more pronounced in the minor stroke cohort, a finding which has never been reported to date. Compared to MFRO, improving NMFRO is more feasible and could significantly enhance the overall QoL in patients with minor stroke severity.

Another result of the present study was that some factors affected QoL mediated by NMFRO. The adverse effect of older age on QoL was partially mediated by NMFRO, with this mediation effect being more pronounced in the non-minor stroke severity cohort. The authors of a previous study reached a similar conclusion and indicated that age and stroke severity are risk factors for depression after stroke [42]. Based on our study results, elderly patients with more severe strokes, compared to those with strokes of minor severity, were more likely to experience non-motor function-related issues, including depression, underscoring the need for heightened attention to these concerns. Additionally, we found that the cohort with more severe stroke was more likely to experience speech impairment, a finding not reported in previous studies. This result may be partially attributed to the impact of speech impairment on NMFRO due to communication barriers. More studies were needed to explore the impact of speech impairment on patients' NMFRP. Taken together, all of these results underscore the importance of patients' NMFRP and the necessity of related treatments. Therefore, future research should investigate NMFRP and evaluate the cost-effectiveness of interventions targeting NMFRO. This approach could lead to more effective improvements in QoL for patients with stroke without imposing a substantial economic burden on society.

The Effects of Hospitalization Costs on QoL

Hospitalization costs significantly influenced the QoL of the patient. The authors of previous studies have reported that socioeconomic factors such as income level, employment status, and social support level were linked to the QoL of patients with stroke [8, 13, 43, 44]. However, hospitalization costs, which are directly related to the national health economic burden, have rarely been explored. In the present study, we observed that hospitalization costs did not consistently lead to improvements in QoL beyond 15,000 CNY within the non-minor stroke severity cohort; for the minor stroke severity cohort, this threshold value was 10,000 CNY. These findings could provide evidence for the pricing and payment setting for AIS in the national health insurance system with the spread of diagnostic-related group (DRG) pricing and payment policy reforms in China, with the aim to improve medical efficiency and to reduce the overall healthcare expenditures of the nation [45].

Limitations

There are several limitations to this study. First, the study was based on the Chinese population, and the conclusions drawn by the authors needed to be further verified in other populations and countries. Second, this study focused on factors during hospitalization; however, data on the discharge destination, a factor which may affect QoL, were not collected. The authors of a previous study reported that the proportion of patients with stroke whose discharge destination was their home reached up to 87% in China [46]. Therefore, the influence of discharge destination on our results was limited [24]. Third, previous studies have identified that neuroanatomical factors (including infarction location) and etiological characteristics (such as the TOAST [Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment] classification) significantly influence AIS outcomes, although these factors were not assessed in the current study [47]. Future well-designed studies are warranted to further elucidate the potential influence of these factors.

Conclusions

In summary, this study explored the determinants of long-term QoL and reported the differences in determinants across cohorts with varying stroke severity. Some factors impact QoL mediated by NMFRO and NMFRO require more attention. Higher hospitalization costs did not consistently result in QoL improvement beyond a certain threshold value. These findings offer insights into understanding the effects of these factors on QoL and provide a foundation for precision medical strategies aimed at improving patient QoL and optimizing the allocation of medical resources.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

Members of the CASTOR study are listed in the ESM. We thank all study participants and the staff in the CASTOR study.

Author Contributions

Yuxuan Lu, Yining Huang, Weiping Sun, and Haiqiang Jin have full access to all of the data in the study and take responsibility for the integrity of the work. Concept: Yuxuan Lu, Weiping Sun, Yining Huang, and Haiqiang Jin. Design: Yuxuan Lu and Haiqiang Jin. Definition of intellectual content: Yuxuan Lu, Weiping Sun, Yining Huang, and Haiqiang Jin. Literature search: Yuxuan Lu. Clinical studies: Yuxuan Lu, Weiping Sun, Yining Huang, Zhaoxia Wang, Zhiyuan Shen, Wei Sun, Ran Liu, Fan Li, Junlong Shu, Qing Peng, Jingjing Jia, Peng Sun, Yijun Song, and Haiqiang Jin. Data acquisition: Yuxuan Lu, Weiping Sun, Yining Huang, and Haiqiang Jin. Data analysis: Yuxuan Lu and Haiqiang Jin. Statistical analysis: Yuxuan Lu and Haiqiang Jin. Manuscript preparation: Yuxuan Lu. Manuscript editing: Haiqiang Jin. Manuscript review: Haiqiang Jin.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 82071306 and No. 81971115). The CASTOR study was funded by Techpool Bio-Pharma Co., Ltd. The Journal’s Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors.

Data Availability

The data of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.

Declarations

Conflicts of interest

Yuxuan Lu, Weiping Sun, Yining Huang, Zhaoxia Wang, Zhiyuan Shen, Wei Sun, Ran Liu, Fan Li, Junlong Shu, Qing Peng, Jingjing Jia, Peng Sun, Yijun Song and Haiqiang Jin have nothing to disclose.

Ethical Approval

The study (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT02470624) was a multicentre study approved by a centralized independent institutional review board (Ethical Board of Peking University First Hospital; Ethical Number: 2015[922]; Master of the Ethical Board: Prof. Xiaohui Guo), with additional local institutional review board approvals obtained where requested (per institute). The participants provided written informed consent to participate in this study. In accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, Good Clinical Practice guidelines were strictly followed, and the privacy of the participants was rigorously safeguarded.

Footnotes

The members of CASTOR Investigators are present in the Electronic Supplementary Material.

Contributor Information

Haiqiang Jin, Email: jhq911@bjmu.edu.cn.

CASTOR Investigators:

Xiaomu Wu, Zhiyu Nie, Xiangzhe Liu, Junfeng Shi, Li Ding, Dai Huang, Ning Wang, Ruiyou Guo, Xuerong Qiu, Jun Wu, Yan Liu, Lianbo Gao, Xingjuan Zhao, Yuhui Han, Xinling Meng, Xuhai Gong, Jie Han, Yongbo Zhang, Jinzhao Wang, Shuhong Ju, Zhilin Jiang, Shuyan Zhang, Deyang Li, Wenwei Yun, Xueqiang Hu, Juming Yu, Junyan Liu, Zhiyun Wang, Deqin Geng, Yukai Wang, Peiyuan Lv, Danhong Wu, Yangtai Guan, Cuilan Wang, Qingchun Gao, Xuejun Zhang, Hongmei Liu, Tao Gong, Shujuan Tian, Shuijiang Song, Shaoshi Wang, Haiqing Song, Zuneng Lu, Xiaoxiang Peng, Qi Fang, Wendan Tao, Shilie Wang, Ping Zhang, Xiaojie Wang, Qiang Zhang, Weishu Xue, Liping Wei, Weiliang Luo, Yuling Jin, Juan Feng, Xinyan Wu, Yongzhong Lin, Hongbing Nie, Wei Liu, Hui Cao, Qi Tan, Yude Zhang, Youqing Deng, Guangxian Nan, Lishu Wan, Xiaoping Yin, Wenyan Zhuo, and Bingzhen Cao

References

- 1.Saini V, Guada L, Yavagal DR. Global epidemiology of stroke and access to acute ischemic stroke interventions. Neurology. 2021;97(20 Suppl 2):S6-16. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000012781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ding Q, Liu S, Yao Y, Liu H, Cai T, Han L. Global, regional, and national burden of ischemic stroke, 1990–2019. Neurology. 2022;98(3):e279. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000013115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gerstl JVE, Blitz SE, Qu QR, et al. Global, regional, and national economic consequences of stroke. Stroke. 2023;54(9):2380–9. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.123.043131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sangha RS, Caprio FZ, Askew R, et al. Quality of life in patients with TIA and minor ischemic stroke. Neurology. 2015;85(22):1957–63. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000002164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Chen H, Cui Y, Zhou Z, Zhang H, Wang L, Wang W, et al. Dual antiplatelet therapy vs alteplase for patients with minor nondisabling acute ischemic stroke. JAMA. 2023;329(24):2135. 10.1001/jama.2023.7827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Delcourt C, Hackett M, Wu Y, et al. Determinants of quality of life after stroke in China. Stroke. 2011;42(2):433–8. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.596627. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Romano JG, Gardener H, Campo-Bustillo I, et al. Predictors of outcomes in patients with mild ischemic stroke symptoms: MaRISS. Stroke. 2021;52(6):1995–2004. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.032809. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kapral MK, Fang J, Chan C, et al. Neighborhood income and stroke care and outcomes. Neurology. 2012;79(12):1200–7. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e31826aac9b. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsalta-Mladenov M, Andonova S. Health-related quality of life after ischemic stroke: impact of sociodemographic and clinical factors. Neurol Res. 2021;43(7):553–61. 10.1080/01616412.2021.1893563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naess H, Waje-Andreassen U, Thomassen L, Nyland H, Myhr K. Health-related quality of life among young adults with ischemic stroke on long-term follow-up. Stroke. 2006;37(5):1232–6. 10.1161/01.STR.0000217652.42273.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Sprigg N, Selby J, Fox L, Berge E, Whynes D, Bath PMW. Very low quality of life after acute stroke. Stroke. 2013;44(12):3458–62. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramos-Lima MJM, Brasileiro IDC, de Lima TL, Braga-Neto P. Quality of life after stroke: impact of clinical and sociodemographic factors. Clinics (Sao Paulo). 2018;73:e418. 10.6061/clinics/2017/e418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kim SR, Yoo S, Kim HY, Kim G. Predictive model for quality of life in patients 1 year after first stroke. J Cardiovasc Nurs. 2021;36(5):E60-70. 10.1097/JCN.0000000000000814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luengo-Fernandez R, Gray AM, Bull L, Welch S, Cuthbertson F, Rothwell PM. Quality of life after TIA and stroke: ten-year results of the Oxford Vascular Study. Neurology. 2013;81(18):1588–95. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182a9f45f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Reeves M, Khoury J, Alwell K, et al. Distribution of National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale in the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky Stroke Study. Stroke. 2013;44(11):3211–3. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.113.002881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hurford R, Wolters FJ, Li L, Lau KK, Küker W, Rothwell PM. Prognosis of asymptomatic intracranial stenosis in patients with transient ischemic attack and minor stroke. JAMA Neurol. 2020;77(8):947. 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sun W, Ou Q, Zhang Z, Qu J, Huang Y. Chinese acute ischemic stroke treatment outcome registry (CASTOR): protocol for a prospective registry study on patterns of real-world treatment of acute ischemic stroke in China. BMC Complem Altern Med. 2017;17(1):357. 10.1186/s12906-017-1863-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Jovin TG, Chamorro A, Cobo E, et al. Thrombectomy within 8 hours after symptom onset in ischemic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2015;372(24):2296–306. 10.1056/NEJMoa1503780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chinese Society Of Neurology Chinese Stroke Scale. Chinese guidelines of diagnosis and treatment for acute ischemic stroke (2014). Chin J Neurol. 2015;48(4):246–57. 10.3760/cma.j.issn.1006-7876.2015.04.002. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lu Y, Sun W, Shen Z, et al. Regional differences in hospital costs of acute ischemic stroke in China: analysis of data from the chinese acute ischemic stroke treatment outcome registry. Front Public Health. 2021;9:783242. 10.3389/fpubh.2021.783242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 21.Langhorne P, Stott DJ, Robertson L, et al. Medical complications after stroke: a multicenter study. Stroke. 2000;31(6):1223–9. 10.1161/01.str.31.6.1223. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Indredavik B, Rohweder G, Naalsund E, Lydersen S. Medical complications in a comprehensive stroke unit and an early supported discharge service. Stroke. 2008;39(2):414–20. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.489294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rajashekar D, Wilms M, MacDonald ME, et al. Lesion-symptom mapping with NIHSS sub-scores in ischemic stroke patients. Stroke Vasc Neurol. 2022;7(2):124–31. 10.1136/svn-2021-001091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Huang Y, Wang J, Wei JW, et al. Age and gender variations in the management of ischaemic stroke in China. Int J Stroke. 2010;5(5):351–9. 10.1111/j.1747-4949.2010.00460.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bettger JP, Li Z, Xian Y, et al. Assessment and provision of rehabilitation among patients hospitalized with acute ischemic stroke in China: findings from the China National Stroke Registry II. Int J Stroke. 2017;12(3):254–63. 10.1177/1747493017701945. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma Y, Liu Y, Fu HM, et al. Evaluation of admission characteristics, hospital length of stay and costs for cerebral infarction in a medium-sized city in China. Eur J Neurol. 2010;17(10):1270–6. 10.1111/j.1468-1331.2010.03007.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Joundi RA, Rebchuk AD, Field TS, et al. Health-related quality of life among patients with acute ischemic stroke and large vessel occlusion in the ESCAPE trial. Stroke (1970). 2021;52(5):1636–42. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.120.033872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Liu GG, Wu H, Li M, Gao C, Luo N. Chinese time trade-off values for EQ-5D health states. Val Health. 2014;17(5):597–604. 10.1016/j.jval.2014.05.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rabin R, de Charro F. EQ-5D: a measure of health status from the EuroQol Group. Ann Med. 2001;33(5):337–43. 10.3109/07853890109002087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ojanguren I, Morell F, Ramón MA, et al. Long-term outcomes in chronic hypersensitivity pneumonitis. Allergy. 2019;74(5):944–52. 10.1111/all.13692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Thomalla G, Fiehler J, Subtil F, et al. Endovascular thrombectomy for acute ischaemic stroke with established large infarct (TENSION): 12-month outcomes of a multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet Neurol. 2024;23(9):883–92. 10.1016/S1474-4422(24)00278-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jensen M, Sehner S, Cheng B, et al. Patient-reported quality of life after intravenous alteplase for stroke in the WAKE-UP trial. Neurology. 2023;100(2):e154–62. 10.1212/WNL.0000000000201375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mol B, van Munster KN, Bogaards JA, et al. Health-related quality of life in patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis: a longitudinal population-based cohort study. Liver Int. 2023;43(5):1056–67. 10.1111/liv.15542. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Guetz B, Bidmon S. The impact of social influence on the intention to use physician rating websites: moderated mediation analysis using a mixed methods approach. J Med Internet Res. 2022;24(11):e37505. 10.2196/37505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Liao M, Xie Z, Ou Q, Yang L, Zou L. Self-efficacy mediates the effect of professional identity on learning engagement for nursing students in higher vocational colleges: a cross-sectional study. Nurs Educ Today. 2024;139: 106225. 10.1016/j.nedt.2024.106225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sfeir M, Rahme C, Obeid S, Hallit S. The mediating role of anxiety and depression between problematic social media use and bulimia nervosa among Lebanese university students. J Eat Disord. 2023;11(1):52. 10.1186/s40337-023-00776-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Chang WH, Sohn MK, Lee J, et al. Predictors of functional level and quality of life at 6 months after a first-ever stroke: the KOSCO study. J Neurol. 2016;263(6):1166–77. 10.1007/s00415-016-8119-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ingeman A, Andersen G, Hundborg HH, Svendsen ML, Johnsen SP. In-hospital medical complications, length of stay, and mortality among stroke unit patients. Stroke. 2011;42(11):3214–8. 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.610881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Torres-Riera S, Arboix A, Parra O, García-Eroles L, Sánchez-López M. Predictive clinical factors of in-hospital mortality in women aged 85 years or more with acute ischemic stroke. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2025;54(1):11-9. 10.1159/000536436. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Wang Y, Wang Y, Zhao X, et al. Clopidogrel with aspirin in acute minor stroke or transient ischemic attack. New Engl J Med. 2013;369(1):11–9. 10.1056/NEJMoa1215340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Song H, Wang Y, Ma Q, et al. Efficacy and safety of recombinant human prourokinase in the treatment of acute ischemic stroke within 4.5 hours of stroke onset. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(7):e2325415. 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.25415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jørgensen TSH, Wium-Andersen IK, Wium-Andersen MK, et al. Incidence of depression after stroke, and associated risk factors and mortality outcomes, in a large cohort of Danish patients. JAMA Psychiat. 2016;73(10):1032. 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2016.1932. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Haacke C, Althaus A, Spottke A, Siebert U, Back T, Dodel R. Long-term outcome after stroke. Stroke. 2006;37(1):193–8. 10.1161/01.STR.0000196990.69412.fb. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Marshall IJ, Wang Y, Crichton S, McKevitt C, Rudd AG, Wolfe CD. The effects of socioeconomic status on stroke risk and outcomes. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(12):1206–18. 10.1016/S1474-4422(15)00200-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Yu L, Lang J. Diagnosis-related Groups (DRG) pricing and payment policy in China: where are we? Hepatobil Surg Nutr. 2020;9(6):771–3. 10.21037/hbsn-2020-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Q, Yang Y, Saver JL. Discharge destination after acute hospitalization strongly predicts three month disability outcome in ischemic stroke. Restor Neurol Neuros. 2015;33(5):771–5. 10.3233/RNN-150531. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Arboix A, Arbe G, Garcia-Eroles L, Oliveres M, Parra O, Massons J. Infarctions in the vascular territory of the posterior cerebral artery: clinical features in 232 patients. BMC Res Notes. 2011;4:329. 10.1186/1756-0500-4-329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data of this study are available from the corresponding author, upon reasonable request.