Abstract

Three new cobalt complexes of the general formula [Co(II)(L)(CH3CN) ]2+, where L is one of three pentadentate nitrogen‐donor ligands based on the N4Py framework, have been synthesized and characterized. The capacity of the three complexes to effect photocatalytic proton reduction has been examined. Their photocatalytic activities in the presence of [Ru(bpy)3]2+, acting as a photosensitizer, and ascorbic acid, acting as a sacrificial electron donor, were screened in a water/acetonitrile mixture. The photochemical mechanism, as revealed by nanosecond time‐resolved transient absorption spectroscopy, involves reaction of the excited sensitizer with ascorbic acid to yield [Ru(bpy)3]+ as a primary photogenerated reductant, capable of electron transfer to the cobalt catalyst(s). Under the experimental conditions used, partial decomposition of both the sensitizer and the catalyst is the main deactivation channel for photocatalysis. Optimization of reaction conditions indicated that the use of more reducing iridium or copper‐based photosensitizers had a beneficial effect on the catalytic performance. The effect of the different ligands on the catalytic activities of the corresponding cobalt complexes have been investigated by DFT calculations.

Keywords: Hydrogen evolution, Photocatalysis, Co(II) complexes, N5-donor ligands

Cobalt(II) complexes of three related pentadentate ligands have been investigated as photoelectrochemical catalysts for proton reduction/hydrogen gas evolution in the presence of ruthenium, iridium, or copper‐based photosensitizers. Potential mechanisms for hydrogen evolution have been investigated by time‐resolved transient absorption spectroscopy and computational modelling.

Introduction

The development of clean and sustainable energy production is necessary to ameliorate the environmental impact of the present use of fossil fuels. In particular, the development of active and stable catalysts for the hydrogen evolution reaction (HER) has been a subject of intense study in order to improve the efficiency of photocatalytic hydrogen evolution. [1] The most studied catalysts are based on earth‐abundant materials such as cobalt, nickel and iron because of their low cost and high activities.[ 2 , 3 ] Among the reported catalysts for H2 evolution, cobalt complexes with pentadentate nitrogen‐donor ligands have gained much attention because of their stabilities in electro‐ and photocatalytic production of hydrogen.[ 4 , 5 ]

Since the pentadentate 2,6‐bis(1,1‐bis(2‐pyridyl)ethyl)pyridine ligand (PY5Me2, Figure 1) was first prepared in the 1980s, [6] several Co(II) complexes of related pentapyridine ligands have been studied for electrocatalytic and photocatalytic proton reduction.[ 7 , 8 , 9 , 10 , 11 , 12 , 13 ] Chang and coworkers [14] identified [Co(II)(OH2)(PY5Me2)]2+ as an active and long‐lived catalyst for hydrogen production from neutral water, and a [Co catalyst]/[Ru(bpy)3]2+/ascorbic acid photocatalytic system was found to produce hydrogen with a TON of 290 over a period of 13 h under blue LED light irradiation. [15] Scandola and coworkers [16] carried out a directly related investigation on [Co(II)(OH2)(PY5OMe2)]2+ using the same photosensitizer and sacrificial electron donor, and found that the ruthenium photosensitizer reacts with ascorbic acid to generate a reductant that reduces the cobalt complex at a bimolecular rate that is on the order of 109 M−1 s−1.

Figure 1.

Structures of N4Py, Py5Me2 and derivatives, DPA‐bpy and DIQ‐bpy.

Aiming to facilitate the multielectron catalytic HER activity of [Co(II)(OH2)(PY5Me2)]2+, Jurss et al. [17] incorporated potentially redox non‐innocent pyrazine moieties in axial or equatorial positions of the Py5Me2 framework. The lower lying π* orbital of pyrazine relative to pyridine was expected to enhance π back bonding to the ligand and thus shift the cobalt reduction potential to more positive values while facilitating ligand reduction. The resultant complex [Co(II)(OH2)(eq‐PY4PZMe2)]2+ was found to catalyze proton reduction under visible light irradiation at pH=5.5 in ascorbic acid solution with a TON of approximately 450 over an 8 h reaction period. [17]

Tuning catalytic performances of molecular cobalt complexes by modulation of the redox potentials and acidity of Co centers via ligand modifications has been the subject of several studies. Zhao and coworkers [18] developed a five‐coordinate cobalt(II) complex of a pentadentate ligand ([Co(II)(DPA‐bpy)]2+) that can catalyze production of H2 with high efficiency in purely aqueous solution by both electrochemical and photochemical approaches. In order to investigate the electronic effect of the ligand on the catalytic properties, Zhao and coworkers replaced the pyridyl groups of [Co(DPA‐bpy)]2+ with isoquinolines and prepared the analogous complexes [Co(DIQ‐bpy)]2+. [19] The univalent cobalt ion that is formed in the photocatalytic process (vide infra) is better stabilized by the isoquinoline groups of the DIQ‐bpy ligand than by the pyridines of DPA‐bpy under otherwise identical conditions. Recently, Zhao, Webster et al. [20] demonstrated a dramatically enhanced catalytic performance of [Co(DPA‐Bpy)2+] for hydrogen evolution by extending the conjugation of the bpy moiety.

Wang and coworkers [9] and Blackman, Collomb and coworkers [21] have studied photocatalytic hydrogen evolution in aqueous solution (water reduction) using a series of [Co(III)(N4Py)(X)]n+ complexes as catalysts (N4Py=N,N‐bis(2‐pyridylmethyl)‐N‐bis (2‐pyridyl)methylamine (Figure 1); X=monodentate ligand, e. g. halide, OH−, H2O, NCMe), [Ru(bpy)3]2+ as a photosensitizer, and ascorbic acid as a sacrificial electron donor. The mechanism(s) of water reduction were studied by time‐resolved nanosecond transient absorption spectroscopy. [21] It was found that the nature of the monodentate ligand on the Co(III) complex was not important for the catalytic efficiency (vide infra). [21] In aqueous solution, the Co(III) complexes are reduced by ascorbate under the photocatalytic conditions to form [Co(II) (N4Py)(HA)]+ (HA=ascorbate) along with some [Co(II)(N4Py)(OH2)]2+. The photosensitizer reduces [Co(II)(N4Py)(HA)]+ to the (probably pentadentate) Co(I) complex [Co(I)(N4Py)]+ which may be considered the active species in the catalytic proton reduction (see further discussion below). [21] In a recent study, Moonshiram and coworkers used transient absorption spectroscopy and nanosecond time‐resolved X‐ray absorption spectroscopy to study photocatalytic hydrogen evolution from pure water using Co(III) complexes of three cyclic tetradentate nitrogen‐donor ligands, [Ru(bpy)3]2+, and ascorbic acid.

Building on the established properties of Co(II) (rather than Co(III)) complexes of pentadentate ligands towards catalytic HER and the above‐mentioned studies on cobalt complexes with the N4Py ligand, this study further investigates the influence of variations in stereoelectronic effects within a given ligand framework on catalytic HER effected by Co(II) complexes. We studied three Co(II) complexes of pentadentate ligands based on the N4Py framework, where one or two terminal pyridyl substituents have been replaced by quinoline or N‐methylbenzimidazolyl moieties (vide infra, Figures 2 and 3). The complexes were investigated as catalysts for proton reduction under visible light irradiation. The electronic effects of the three ligands on the cobalt ion have been assessed by UV‐Vis spectrophotometry and electrochemical measurements, and modeled by density functional theory (DFT) calculations. The primary photochemical processes in the photocatalytic system have been probed by time‐resolved spectroscopic analyses and possible pathways for hydrogen evolution have been modeled computationally.

Figure 2.

Pentadentate nitrogen‐donor ligands used in this study.

Figure 3.

Schematic structures of the cationic complexes [Co(II)(L1 )(CH3CN)]2+ (1), [Co(II)(L2 )(CH3CN)]2+ (2) and [Co(II)(L3 )(CH3CN)]2+ (3).

Results and Discussion

Synthesis and Characterization of Ligands and Complexes

Three known pentadentate N5‐donor ligands based on the N4Py framework were used, viz. [N,N‐bis(2‐quinolylmethyl)‐N‐bis(2‐pyridyl)methylamine](L1 ), [N,N‐bis(1‐ methyl‐2‐benzimidazolylmethyl)‐N‐bis(2‐pyridyl)methylamine] (L2 ), and [N‐(1‐methyl‐2‐benzimidazolyl)methyl‐N‐(2‐pyridyl)methyl‐N‐bis(2‐pyridyl)methylamine](L3 ) (Figure 2).

The corresponding Co(II) complexes, [Co(II)(L1 )(CH3CN)](ClO4)2 (1 ⋅ (ClO4)2), [Co(II)(L2 )(CH3CN)](ClO4)2 (2 ⋅ (ClO4)2), and [Co(II)(L3 )(CH3CN)](ClO4)2 (3 ⋅ (ClO4)2) (Figure 3) were synthesized by reaction of 1 equiv. of L1 /L2 /L3 with 1 equiv. of Co(ClO4)2⋅6H2O in a minimum amount of dry acetonitrile at ambient temperature. All complexes were isolated as air‐stable solids. The three new cobalt complexes were characterized by IR and UV‐Vis spectroscopies, cyclic voltammetry, high‐resolution mass spectrometry (HRMS) and single crystal X‐ray studies of 1 and 2.

The IR spectra (Figure S1, Supplementary Information) of the three complexes are virtually identical and indicate a strong structural resemblance between the three complexes. As shown in Figure 4, the UV‐visible spectra of complexes 1–3 in acetonitrile solution show weak absorptions around 500 nm at room temperature with different molar absorptivities (cf. Experimental Section). The weak and broad absorption around 500 nm is a common feature for d‐d transitions of Co(II) complexes in acetonitrile. We tentatively assign the absorptions to the 4T2(F) ← 4T1 lowest energy transition for an S=3/2 octahedral Co(II) ion, or a compound absorption consisting of 4T2(F) ← 4T1 and 4T1(P) ←4T1(F) transitions. [21] The UV‐Vis spectra constitute indirect measurements of the ligand field strengths, and by this measure the relative ligand field strengths are 2>3>1.

Figure 4.

UV‐Vis absorption spectra of complexes 1 (485 nm, ϵ=61.5 M−1 cm−1), 2 (449 nm, ϵ=84.5 M−1 cm−1) and 3 (459 nm, ϵ=122.1 M−1 cm−1) in acetonitrile.

Cyclic Voltammetry

Cyclic voltammetry was used to determine the redox potentials of the Co(II)/Co(I) and Co(III)/Co(II) couples for complexes 1–3. Cyclic voltammograms for the three complexes are shown in Figure 5 and the observed redox potentials are listed in Table 1. Further cyclic voltammograms recorded at different scan rates are presented in the Supplementary Information (Figures S5–S7). While the Co(II)/Co(I) couple is well‐behaved for all three complexes with apparent chemical reversibility and electrochemical quasi‐reversibility (Δep=89 mV (1); 108 mV (2); 99 mV (3)) this is not the case for the corresponding Co(III)/Co(II) couples, which all display chemical and electrochemical irreversibility/quasi‐reversibility. In particular, the Co(II)/Co(III) oxidation wave is broad and poorly defined, while the return wave is more well‐behaved. The broad oxidation feature remains in the voltammograms of all three cobalt complexes regardless of the scan rate (100–900 mVs−1, Figures S5–S7). This suggests that a chemical transformation occurs upon oxidation to the Co(III) oxidation state. This observation is in contrast to the electrochemical behavior by a number of [Co(II)(N4Py)(X)]n+ complexes (n=1, 2; X=monodentate ligand) that were generated by bulk electrolysis of their corresponding Co(III) complexes; for these Co(II) complexes, the Co(II)/Co(I) and Co(III)/Co(II) couples displayed similar (quasi‐reversible) behaviour. [21] The reasons for the electrochemical differences between those Co(II)(N4Py) complexes and the complexes described here are unclear. Nevertheless, the well‐behaved Co(II)/Co(I) redox couples found for 1–3 are of direct relevance to the potential active catalytic species and can be directly related to the effective ligand field strengths exerted by L1‐L3, which by this measure also rank in the order 2>3>1.

Figure 5.

Cyclic voltammograms of 1 mM solutions of complexes 1, 2, and 3 in acetonitrile (cf. Table 1). Supporting electrolyte, 0.1 M (NBu4)PF6; glassy carbon electrode; scan rate=100 mVs−1. The initial scan direction was to negative potentials.

Table 1.

Redox potentials (E1/2)‐for complexes 1–3. Potentials are referenced to the Fc/Fc+ couple.

|

Complex |

E1/2 (V vs Fc/Fc+) |

|

|---|---|---|

|

CoIII/II (V) |

CoII/I (V) |

|

|

1 |

0.59 |

−1.47 |

|

2 |

0.45 |

−1.73 |

|

3 |

0.20 |

−1.64 |

Crystal and Molecular Structures

Single crystals of [Co(II)(CH3CN)(L1)](ClO4)2 (1 ⋅ (ClO4)2) and [Co(II)(CH3CN)(L2)](ClO4)2 (2 ⋅ (ClO4)2) were obtained through vapor diffusion of ethyl acetate into acetonitrile solutions of either complex to yield dark brown crystals suitable for X‐ray diffraction. Relevant crystallographic data for the cationic complexes 1 and 2 are summarized in Table S1 (Supporting information). The molecular structures (Figure 6(a), (b)) show that the Co(II) ions adopt distorted octahedral coordination geometries with five positions occupied by the pentadentate ligand and sixth (axial) position occupied by a solvent molecule (acetonitrile). For the cationic complexes, the central amine nitrogen of the ligand backbone is coordinated trans to the coordinated acetonitrile molecule while the other four coordination sites of the pyridine and nitrogen donor groups (two quinolines for 1; two (methyl)benzimidazoles for 2 and one quinoline and one (methyl)benzimidazole for 3, respectively) constitute an equatorial plane. As shown in Table S2, the range of the Co−L bond lengths (2.0973(15)–2.1738(15) Å 1; 2.057(2)–2.194(3) Å 2) are indicative of both complexes containing high‐spin (S=3/2) Co(II) ions. [22] Furthermore, the Co−N bond lengths are in the range of the expected values for the two pyridines (2.1389(16) and 2.1530(15) Å for 1; 2.152(2) and 2.131(2) Å for 2, respectively), the two quinolines and methyl benzimidazole moieties (2.1738(15) and 2.1685(15) Å for 1; 2.059(2) and 2.077(2) Å for 2, respectively), and for the (solvent) acetonitrile molecule (2.0973(15) Å for 1; 2.057(2) Å for 2, respectively).

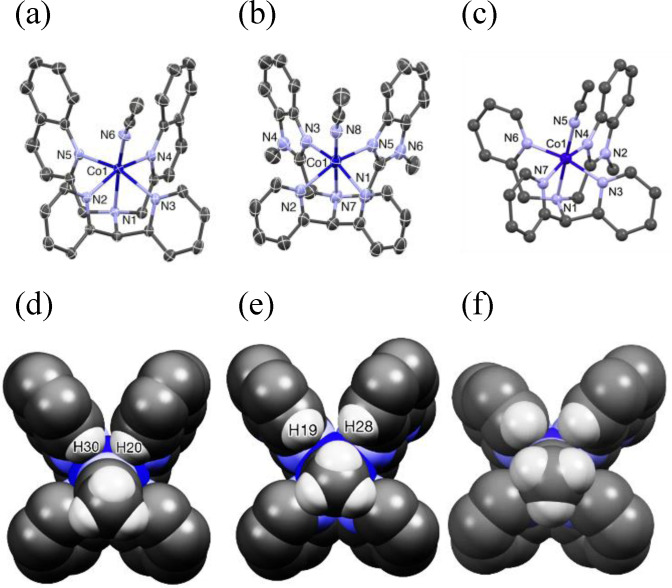

Figure 6.

Mercury plots, showing parts of the atom labelling schemes for (a) the molecular structure of [Co(II)(CH3CN)(L1 )]2+ (1), (b) the molecular structure of [Co(II)(CH3CN)(L2 )]2+ (2) (c) the computationally optimized molecular structure of [Co(II)(CH3CN)(L1 )]2+ (3). Thermal ellipsoids for 1 and 2 are drawn at 50 % probability level; hydrogen atoms and counterions have been omitted for clarity. Selected bond distances (Å) and bond angles (°) of complexes are listed in Table S2. It may be noted that complex 3 is chiral with stereogenic centers at Co1 and N3, but a racemic mixture is expected. (d–f) Space‐filling plots of complexes 1, 2 and 3, respectively, looking down the NCMe−Co axes, illustrating parts of the steric interactions in the complexes.

As shown in Table S3, the differences in bond lengths between complexes 1 and 2 that are discussed above are likely to arise from the steric and electronic effects of the heterocycles in L1 and L2 that replace two of the pyridine donors of the N4Py framework. The basicity of the heterocycles increases from quinoline to pyridine to benzimidazole, and this effect on the bond lengths of the equatorial ligands is in part reflected by the short benzimidazole Co−N bond lengths of 2.059(2) and 2.077(2), average 2.068(2) Å, in 2 and longer quinoline Co−N bond lengths of 2.1738(15) and 2.1685(15), average 2.1711(15) Å, in 1, but, as is discussed below, the influence of steric effects is expected to predominate on these bond lengths. The steric effect is best demonstrated in the crystal structure of 1, which shows that atoms H20 and H30 of the two quinolines are on average only about 2.48 Å away from the N atom of acetonitrile (Figures 6d and S2). For comparison, the corresponding H19 and H28 atoms (Figure 6e) of the benzimidazole donors are much farther away, ca 2.97 Å from the N atom of acetonitrile. As a consequence, the quinoline H would appear to exert a steric effect that results in a tilt of the Co‐NCH3CN unit in 1 away from the axial line by 15.1°; similar tilts of monodentate ligands have been observed in crystal structures of octahedral Mn(II), [24] Fe(II), [25] Fe(IV), [26] Cu(II) [27] and Zn(II) [27] complexes of L1 . The Nam‐Co‐NCH3CN angle observed for 2 is closer to that of a linear arrangement, namely 174.90(9)°. The computed structure for complex 3 indicates that the steric effect of L3 with respect to the Nam‐Co‐NCH3CN angle is similar to that of L2 , with this angle being 177.9° for the computed structure. Figures 6d–f illustrate the steric interactions of the ligands with the axial acetonitrile ligand. We infer that the steric effects in complex 1 are responsible for its longer Co−N bond lengths and outweigh the electronic effects of quinolines. [26] This also means that the steric influences of the ligands affect the ligand field strength; again, an ordering of 2>1 is found.

Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution

A comparison of the photocatalytic activities of cobalt complexes 1–3 with related catalysts reported in the literature is not straightforward. This is due to the necessity to consider the activities within the constraints of the entire hydrogen evolving system, which is strictly dependent on the experimental conditions used ‐ in particular the pH, concentrations of the reactants, solvent medium, and the photon flux. A number of studies[ 8 , 21 , 22 , 28 ] have found that the optimum pH value (4.0) for H2 production matches the pKa1 value of 4.03 for the sacrificial electron donor ascorbic acid (H2A), [29] creating an effective buffer system. Figure 7(a) shows the dependence of the photocatalytic H2 evolution on the concentration of [Ru(bpy)3]2+ with catalyst 1 at pH 4. In this system, the best photosensitizer concentration for H2 production (highest TON) was determined to be 130 μM. Increasing the concentration of 1 from 0 μM to 130 μM results in growth of the H2 production from 0 μmol to 27.6 μmol during 5 h of irradiation under visible light emulating the solar spectrum (Figure 7(b)). The photocatalytic hydrogen evolution experiments in this study were finally carried out with 130 μM [Ru(bpy)3]2+, 0.125 M ascorbic acid and 130 μM of catalyst (1–3) at pH 4 in 10 mL of a water/acetonitrile mixture solution (1 : 1 v/v) (Figure 7 (c) and (d)).

Figure 7.

Hydrogen production of (a) different [Ru(bpy)3]2+ concentration with 130 μM catalyst 1 and (b) different concentrations of catalyst 1 with 130 μM [Ru(bpy)3]2+ in 10 mL in an acetonitrile:water solution (1 : 1) at pH 4 containing 0.125 M ascorbic acid, (c) hydrogen production by 130 μM of catalysts 1–3 in 10 mL an acetronitrile/water solution (1 : 1) at pH 4 containing 130 μM [Ru(bpy)3]2+, 0.125 M ascorbic acid (averages of three different experiments), (d) maximum turnover numbers (TON) observed for the three different cobalt catalysts 1–3.

The hydrogen evolution effected by 1–3 (vide infra) is less than that reported for similar compounds [21] but that may (at least in part) be ascribed to different experimental conditions used, for example the low concentration of ascorbic acid in the present study. The hydrogen production detected for the three cobalt catalysts levels off after approximately 5 hours of irradiation (Figure 7(c) and (d)). Overall, an average H2 production of between 20.1 and 27.6 μmol, with average TONs between 16.1 and 25.2 depending on the catalyst, is detected. The 1 ⋅ (ClO4)2 catalyst shows the best hydrogen production among this class of cobalt complexes with up to 27.6 μmol of H2 produced after 5 h of irradiation and the TON for 1 ⋅ (ClO4)2 is also the best among the three catalysts, while the other two cobalt catalysts performed similarly.

Ligand Influence on the Photocatalytic Activity of the Cobalt Complexes

We found that the tilt of the acetonitrile ligand away from the Co−Namine axis in the structures of 1–3, as determined by X‐ray crystallography and computational modelling, Co−N distances, Co(II)/Co(I) reduction potentials and UV‐Vis absorptions are all consistent with relative ligand field strengths in the order 2>3>1 (Table S4). This relative order does not correlate directly with the observed photocatalytic proton reduction activities (cf. Figure 7 (c)), where the TOFs vary with time. However, it may be noted that the complex with the weakest ligand field (1) shows the best overall photocatalytic performance. Furthermore, the observed ligand field strengths and their steric origins relate to the six‐coordinate Co(II) complexes and might not be directly translatable to potential five‐coordinate Co(I) complexes (vide infra). However, the ligand field will influence the Lewis basicity of the Co ion and it may thus be inferred that this basicity will decrease in the same order as the ligand field strength. Thus, a five‐coordinate Co(I) complex of L2 might be expected to be most prone to react with a proton (oxonium ion), while a Co(III) hydride complex of L1 might be expected to be most prone to undergo a homolytic Co−H bond cleavage ‐ see discussion below.

Intermolecular Electron Transfer – Mechanistic Insights

The photoinduced intermolecular electron transfer steps in the [Ru(bpy)3]2+/catalyst/H2A system have been explored by nanosecond transient absorption (TA) spectroscopy. The spectroscopic experiments were performed under catalytic reaction conditions, i. e. the same concentrations of photosensitizer, catalyst and sacrificial donor in a water/acetonitrile mixture (1 : 1, pH=4) that were used in the catalytic experiments. Upon excitation of the [Ru(bpy)3]2+ photosensitizer at 450 nm, the ns TA spectra of the system with/without a catalyst display identical spectral features (see Figures S1–4). Figure 8(a) and (b) show examples of the ns TA data in the absence and presence of catalyst 2, respectively. At a delay of 20 ns, the TA spectrum is characteristic for a triplet metal‐to‐ligand charge transfer (3MLCT) state of [Ru(bpy)3]2+, i. e. a sharp positive band at 370 nm, a ground‐state bleach at 400–500 nm and a very weak absorption in the visible region. [30] With increasing delay times, i. e. between 20 and 600 ns, the band at 370 nm and hence the 3MLCT state of *[Ru(bpy)3]2+, i. e. [Ru(III)(bpy)2(bpy)⋅−]2+, decreases. At the same time a new band appears at around 500 nm (Figure 8(a), (b) and (c)), which is indicative of the reduced photosensitizer, i. e. [Ru(II)(bpy)2(bpy)⋅−]+.[ 1 , 18 ] The emergence of [Ru(II)(bpy)2(bpy)⋅−]+, due to reductive quenching of the 3MLCT state of the photosensitizer, is characterized by a time constant (inverse first order rate constant) of 120 ns irrespective of the presence of a catalyst (Figure 8 (c) and Figure S1b–4b). Time‐resolved emission (see Figure S1c–4c) shows that in the presence of a catalyst the typical 3MLCT phosphorescence of *[Ru(bpy)3]2+ at 620 nm decays mono‐exponentially with a time constant of 120 ns. This indicates that reductive quenching of the 3MLCT state of the excited [Ru(bpy)3]2+ by the sacrificial donor (k q=4 107 M−1 s−1) is the initial step of the photocatalytic process. Similar observations have been previously reported by Wang et al. [9] and Lo et al. [21] for related Co(III)(N4Py) systems. Furthermore, literature reports the generally quite high yield of this diffusion‐controlled reaction to be ca. 70 %. [4]

Figure 8.

Nanosecond transient absorption (TA) spectra of the solution containing 0.13 mM [Ru(bpy)3]2+, 110 mM ascorbic acid and (a) without a Co(II) catalyst and (b) with 0.13 mM catalyst 2 upon excitation at 450 nm in aerated water/acetonitrile mixture (1 : 1 v/v) at pH 4. (c) Comparison of the normalized kinetics with the corresponding fit at 360 nm (top) and 500 nm (bottom). (d) Global fit results of the ns TA data shown in (b).

At about 600 ns after photoexcitation, the initial spectral changes due to formation of [Ru(II)(bpy)2(bpy)⋅−]+ are complete and the resultant differential absorption signal decays to zero within 400 μs (Figure 8 (a)–(c)). Irrespective of the actual catalyst, the absorption features of [Ru(II)(bpy)2(bpy)⋅−]+ decay bi‐exponentially (Figure 8 (c), (d) and Figures S1–4). In the absence of a Co(II) catalyst, the experimentally observed time constants are 9 and 54 μs (Figure S1b). A bi‐exponential decay in the absence of a catalyst was also observed by Lo et al., [21] The authors rationalized this finding by charge recombination between [Ru(II)(bpy)2(bpy)⋅−]+ and different oxidized forms of ascorbate (i. e. HA⋅ radical and the dehydroascorbic acid A). [21] In the presence of a catalyst, the decay of [Ru(II)(bpy)2(bpy)⋅−]+ becomes slightly faster, i. e. the characteristic time‐constants are determined to be 5 and 30 μs for catalyst 2 (Figure 8 (d); for catalysts 1 and 3, see Figures S2b and S4b). This finding points to the fact that intermolecular electron transfer from [Ru(II)(bpy)2(bpy)⋅−]+ to the catalyst presents an additional decay channel for the reduced photosensitizer. However, we have to conclude that this intermolecular electron transfer is not the sole and dominating reaction channel as the addition of the catalyst accelerates the decay of [Ru(II)(bpy)2(bpy)⋅−]+ only modestly. This is in agreement with the findings by Lo et al. mentioned above, and by Scandola et al., who showed that dehydroascorbic acid (A) quenches [Ru(II)(bpy)2(bpy)⋅−]+. [21] The experimentally determined time constants in the absence and presence of the catalyst allow us to roughly estimate the characteristic electron transfer times from reduced [Ru(bpy)3]+ to the catalysts to be 117 μs, 67 μs and 85 μs for 1, 2 and 3, respectively (Table S6, see Supporting Information for details). The slow intermolecular electron transfer and low stability of the Co(I) species might thus account for the moderate activity for proton reduction. [18] It may be noted that these results are consistent with Blackman's work on the related Co(III)(N4Py) system. [21] In that study, a bi‐modal decay of the reduced photosensitizer, [Ru(II)(bpy)2(bpy)⋅−]+, with characteristic time constants of 9 and 30 μs were observed in the presence of [Co(N4Py)(OH2)]3+ (0.2 mM; 0.1 mM for [Ru(bpy)3]2+) and an excess of the sacrificial donor ascorbate (1 M), in water/acetonitrile mixture (1 : 1, pH 4). [21] The slow intermolecular electron transfer and low stability of the Co(I) species were posited to account for the moderate activity for proton reduction. [21]

Possible Mechanism(s) for the Photocatalytic Evolution of H2

On the basis of the photophysical data and previous photophysical and computational studies on other photocatalytic systems for hydrogen evolution involving related molecular Co(II) and Co(III) catalysts,[ 18 , 21 , 31 , 32 , 33 , 34 , 35 , 36 , 37 , 38 , 39 ] we propose that the photocatalytic cycle begins with the reduction of *[Ru(bpy)3]2+ by ascorbate to afford the reduced state [Ru(bpy)3]+ and the neutral radical HA⋅ (Scheme 1). The HA⋅ species is known to deprotonate easily to form the radical anion A⋅− that disproportionates in acidic aqueous solution to give HA− (A2−) and two‐electron oxidized dehydroascorbic acid A. Reduced [Ru(bpy)3]+ possesses a sufficiently negative potential to reduce the Co(II) catalysts 1–3 to the Co(I) oxidation state, and that reduced species enters the catalytic cycle for H2 evolution (Scheme 1). The reduced Co(I) complexes can react with a proton under acidic conditions to generate Co(III) hydride complexes. [21]

Scheme 1.

Schematic summary of the primary photochemical processes and a possible catalytic HER cycle occurring upon light irradiation of the photolysis mixture containing [Ru(bpy)3]2+, cobalt catalyst (1–3), and ascorbic acid (bpy=2,2’‐bipyridine).

As previously discussed, studies on [Co(III)(N4Py)(X)]n+ by Wang and coworkers [9] and Blackman, Collomb and coworkers [21] gave conflicting results – Wang and coworkers obtained results that suggest partial decoordination of the pentadentate ligand in the formation of the Co(III)‐hydride complex, whereas the catalytic results obtained by the latter group strongly implicated dissociation of the apical ligand to form a five‐coordinate Co(I) complex that can react with a proton. As discussed by Blackman, Collomb and coworkers [21] the resultant six‐coordinate Co(III) hydride complex may react in different ways. One possibility is a reaction with a second Co(III) hydride complex, resulting in a bimolecular coupling reaction involving homolytic cleavage of the Co(III)−H bonds to generate H2 and the corresponding Co(II) species. The latter may in turn react with HA− to form [Co(II)(AH)(N5‐ligand)]+, as schematically depicted in the catalytic cycle in Scheme 1. A second possibility (not depicted) is the reaction of the Co(III) hydride complex with a proton (oxonium ion) in a coupling reaction that generates H2 via heterolytic cleavage of the Co(III)−H bond; however, there should be a significant electrostatic barrier for the initial association of the two cations. A third possibility is that the Co(III)−H complex is reduced to its Co(II)−H analogue by the photosensitizer, followed by reaction with an oxonium ion to produce H2, as proposed for a number of cobalt‐based catalytic systems (Scheme 1). [21] The relatively low activity of hydrogen production may be explained by low stability of the Co(I) species that are formed and that constitute the gateway to the catalytic cycle.

In order to assess the viability of these different pathways leading to dihydrogen formation, they were computationally modelled by DFT calculations. Initially, the structures of the Co(III) hydride derivatives of complexes 1–3, i. e. [Co(III)(LN)(H)]2+ (LN=L1 ‐L3 ), were optimized (Figure S14). Next, the reactions of the three Co(III)−H complexes with (i) an oxonium ion (heterolytic Co(III)−H bond cleavage) or (ii) a second Co(III)−H molecule (modelling homolytic cleavage) were studied (Scheme 1 and Figure 9a). In the case of the heterolytic pathway, a two‐step reaction was identified; first hydrogen formation and coordination ([Co(III)(LN)(H2)]2+) and finally hydrogen release ([Co(III)(LN)]2+ + H2). Both reaction steps were calculated as uphill processes (ca. 7–10 kcal/mol and ca. 10–14 kcal/mol, respectively) and the estimated backward reaction towards [Co(III)(LN)(H)]2+ is almost barrierless (ca. 0.2–0.4 kcal/mol as estimated from a ([Co(III)(LN)(H2)]2+ + H3O+ energy potential scan, see Figure 9(b)). In the case of the homolytic pathway, two Co(III)−H complexes were oriented so that the two hydride ligands were pointing towards each other and sequentially optimized. The energy of the linear transit was further explored to identify the activation energy cost. In addition to an unfavorable electrostatic interaction between the two dicationic cobalt complexes, a significant steric barrier is also observed in the activation energies (13–14 kcal/mol for L3 and L2 and 21 kcal/mol for the bulkier L1 ligand) despite the favorable reaction energy towards dihydrogen formation. In all cases, the approach of the two cobalt species towards each other requires a rotation of approximately 140–160 degrees of one complex relative to the other in order to minimize steric interactions (graphical representation in the Supporting Information). Finally, reaction of the complexes [Co(II)(LN)(H)] + (LN=L1 ‐L3 ) – formed by photoreduction of the Co(III) hydride complexes (vide supra, and Figure 9a) – with an oxonium ion were also modelled. Reduction to form the Co(II) hydride complex leads to the weakening of the Co−H bond, as observed from the calculated νCo(II)‐H vibration frequencies (the energy diminished from νCo(III)‐H ca. 2000 cm−1 to νCo(II)‐H ca. 1300 cm−1), thus favoring a heterolytic pathway. It was found that such a reaction was a highly downhill process of ca. 50 kcal/mol for all three Co(II) hydride complexes (Figure 9(b)), leading to facile formation of dihydrogen. Thus, the barrier to hydrogen evolution by this pathway is essentially limited by the barrier to photoreduction of the Co(III) hydride precursors. In summary, the three possible hydrogen formation pathways are competing processes highly dependent on the system conditions, e. g. strong photoredox species, cobalt catalyst concentrations or acidity conditions. The higher hydrogen yield observed for [Co(II)(L1 )]2+ compared to the [Co(II)(L1 )]2+ and [Co(II)(L1 )]2+ catalysts may be attributed to the less negative Co(III/II) reduction potential of the [Co(III)(LN )(H)]2+ species, promoting the heterolytic pathway through protonation of [Co(II)(LN )(H)]+.

Figure 9.

(a) Reaction energy diagram for hydrogen formation catalysed by [Co(II)(L1 )]2+. (b) Comparison of reaction energy profiles for complexes 1, 2, and 3. Vertical arrows correspond to one‐electron redox reactions of the catalysts 1 – 3 referenced against the ferrocene potential (Fc+/Fc). Dashed lines designate the homolytic cleavage reaction pathways. All energies are referenced to the corresponding monomer and dimer hydride species [Co(III)(LN)(H)]2+ (LN=L1‐L3). All calculations were performed at the B3LYP/6–31+G(d)/CPCM(water) level of theory.

Optimization of Photocatalytic Hydrogen Evolution

As outlined above, the photocatalytic reactions employing Co(II) complexes 1–3 may be directly related to the analogous studies on Co(III)(N4Py) complexes [21] as the same photosensitizer ([Ru(bpy)3]2+) and sacrificial electron donor (ascorbic acid/ascorbate) were used. However, the turnover numbers that were achieved were low (vide supra). For this reason, it was decided to explore the photocatalytic conditions (solvent mixture, photosensitizer, sacrificial electron donor) more widely, using the two best‐performing catalysts ‐ which are also the two complexes that differ the most in terms of redox potentials/electronic effect, i. e. [Co(II)(L1)(CH3CN)]2+ (1) and [Co(II)(L2)(CH3CN)]2+ (2) – in order to maximize the TON.

We chose a larger water/acetonitrile ratio (4 : 1; 8 : 2 mL) to facilitate metal protonation, while maintaining the same photosensitizer and sacrificial electron donor concentrations (and thus a similar redox potential). The ratio of photosensitizer to cobalt complex was increased to 10 : 1 with the aim of increasing the (steady‐state) concentration of the key Co(I) catalytic intermediate and thus potentially increasing the catalytic rate. Under these conditions, the TON increased approximately 6 and 7‐fold for complexes 1 (TON 100±14, 26±1 μmol of H2) and 2 (TON 160±17, 38±4 μmol of H2), respectively, using royal blue LEDs as an irradiation source (450±20 nm at ca. 0.3 W cm2, see Table S7, Supporting Information, for further experimental details). As in the previous reaction conditions, the rate of H2 evolution was found to be higher for cobalt complex 1, which is most easily reduced (cf. Table 1). In contrast, under basic conditions, the behaviour is different. When using the more reducing photosensitizers [Ir(ppy)2(bpy)](PF6) (ppy=2‐phenylpyridine) (PSIr ) or [Cu(Batho‐SO3 −)(Xantphos)Na] (PSCu(SO3) , Batho‐SO3 −=4,7‐Diphenyl‐2,9‐dimethyl‐phenantroline‐1,10‐disulfonate, Xantphos=4,5‐Bis(diphenylphosphino)‐9,9‐dimethylxanthene) in combination with Et3N as electron donor, the amount of detected hydrogen dropped significantly (less than 30 TON). Since both photosensitizers are more reducing than [Ru(bpy)3]+ (Table 2), a higher catalytic activity could be expected ‐ as previously observed for similar systems.[ 13 , 40 , 41 ] However, at the basic pH (ca 11) imposed by the sacrificial donor triethylamine, the low catalytic activity could be explained by the protonation of Co(I) to form the Co(III)‐H intermediate, or the subsequent H2 evolution step, being compromised.

Table 2.

Redox potentials in acetonitrile for the employed photo‐sensitizers.

To improve the quantity of available protons while maintaining a high redox potential, we tested the photocatalytic activity of both cobalt complexes employing PSCu(SO3) and Et3N, but in pure water. Photocatalytic hydrogen evolution in pure water is still rare due to low catalyst stabilities, but also due to poor solubilities of photosensitizers and catalysts in water. However, cobalt complexes 1 and 2 are soluble at concentrations higher than millimolar in water. We selected PSCu(SO3) as photosensitizer because the two disulfonate groups of the ligand confer high solubility in water. To our delight, the catalysts were not only active for photocatalytic hydrogen formation but the amount of hydrogen formed increased approximately 3‐fold relative to that found in the water: acetonitrile mixture (4 : 1). Thus, values of TONs higher than 400 were obtained for both cobalt catalysts. In the case of complex 2, a ca. four‐fold increase in catalytic rate was also observed (Figure 10). More interestingly, the relative H2 formation rates between 1 and 2 were reversed relative to those obtained under the less reducing conditions, i. e. 2 gave higher H2 production rates than 1 (Figure 10). These results are consistent with the redox values reported for the photosensitizers (Table 2) and for complexes 1 and 2 (Table 1). The redox potential of the complexes and the identified relative ligand field strengths suggest that the driving force for the protonation of cobalt (I), and the reactivity of the subsequent cobalt hydride, should be larger for complex 2 than 1. This is the case when using the highly reducing PSCu(SO3) . With a redox potential of −2.04 V, the reduced species of the photosensitizer can reduce both cobalt(II) complexes to cobalt(I) (−1.47 and −1.73 V, for 1 and 2 respectively, cf. Table 1). In contrast, PSRu (−1.71 V) is sufficiently reducing to ensure an effective one electron reduction of complex 1 to the corresponding cobalt (I) species, but any reduction of complex 2 by PSRu will be incomplete, in agreement with the inverted reaction rate.

Figure 10.

Comparison between TONs of hydrogen produced with catalyst 1 (25 μM, black lines) and photosensitizers [Ru(bpy)3](PF6)2 (PSRu , 250 μM, solid lines) in a water and acetonitrile mixture solution (4 : 1) at pH 5.5 containing 0.3 M ascorbic acid/ascorbate (1 : 1) and PSCu(SO3) (250 μM, dotted lines) in pure water with Et3N (0.2 mL) as electron donor, and catalyst 2 (250 μM, red lines) under the same condition. Solid lines represent the averages of two different experiments, with error bars depicting the variability.

Summary and Conclusions

Three new Co(II) complexes (1–3) of the general formula [CoII(CH3CN)(L1 )]2+ (L=L1‐L3 , N5‐donor ligands based on based on the N4Py framework) have been investigated as catalysts for light‐driven hydrogen evolution in a water/acetonitrile solution around pH 4.0 with the presence of ascorbic acid (H2A) and [Ru(bpy)3]2+ photosensitizer. The catalytic activities of these complexes were found to be relatively moderate under the experimental conditions employed. These modest catalytic activities may be due to low stabilities of the Co(I) species that are formed in the photocatalytic processes. The photocatalytic performance could be significantly improved by using more reducing photosensitizers that provide better capacity for generation of the posited reduced Co(I) intermediates. Good photocatalytic H2 generation in pure water could be achieved when the water‐soluble photosensitizer [Cu(Batho‐SO3 −)(Xantphos)Na] was employed and triethylamine was used as a sacrificial electron donor.

Computational modelling indicates that upon reaction of a Co(I) species with a proton (oxonium ion) to form a Co(III) hydride species, further reaction of Co(III)−H to form hydrogen gas can occur via both a bimolecular coupling reaction (reaction with a second Co(III)−H molecule) involving homolytic cleavage of the Co(III)−H bond or a reaction with a second oxonium ion, i. e. protonation of the hydride and heterolytic cleavage of the Co(III)−H bond. For all three complexes, the activation energies for these two pathways are of similar magnitudes, but the transition state for the bimolecular pathway (homolytic Co(III)−H bond cleavage) lies consistently higher than the transition state for the pathway requiring protonation of the hydride and heterolytic cleavage of the Co(III)−H bond. On the other hand, in the event that photoreduction of a Co(III)−H species to form a corresponding Co(II)−H complex takes place, the subsequent heterolytic reaction with an oxonium ion to form H2 is essentially a barrier‐less reaction.

Experimental Section

Materials and Physical Measurements

Commercial grade chemicals were used without further purification and HPLC grade solvents were used as received. All syntheses and manipulations were performed with standard laboratory equipment. NMR spectra were recorded using a Varian Inova 500 MHz spectrometer with standard settings for 1H and 13C nuclei, using deuterated chloroform and acetonitrile as solvents, and referenced to the residual signal of the solvent. Peaks are reported as singlet (s), doublet (d), doublet of doublets (dd), triplet (t) and multiplet (m or unresolved), coupling constants are given in Hz. Fourier‐transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR) was recorded by using an Agilent Cary 630 FTIR Spectrometer. Mass spectrometry was performed on a Waters QTOF XEVO−G2 spectrometer using calibrant as CsI. Results are denoted as cationic mass peaks; unit is the mass/charge ratio. Electrochemical measurements were performed using a PalmSense 4 potentiostat and processed with PSTrace 5.8 software.

Synthesis

Ligands L1 –L3 were synthesized by previously published methods.[ 23 , 27 ] Further details of these syntheses are described in the Supplementary Information.

Preparation of Complexes 1–3

Caution! Although no problems were encountered during the course of this work, extreme care should be exercised in handling potentially explosive perchlorate salts. The same synthetic procedure was used for the preparation of all three complexes. A solution of the pentadentate ligand in 2 mL of acetonitrile was combined with a solution of Co(ClO4)2⋅6H2O in 1 mL of acetonitrile (L1 (100 mg, 0.214 mmol): Co(ClO4)2⋅6H2O (55 mg, 0.15 mmol); L2 (100 mg, 0.211 mmol): Co(ClO4)2⋅6H2O (55 mg, 0.15 mmol); L3 (90 mg, 0.214 mmol): Co(ClO4)2⋅6H2O (78.3 mg, 0.214 mmol))in a 50 ml round‐bottom flask. The resultant mixture was allowed to stir for 1 h at room temperature under inert atmosphere and the red reaction mixture was concentrated to ∼2 mL upon slow evaporation. The resultant concentrated acetonitrile solution was placed into an ethyl acetate bath inside a desiccator for slow diffusion and stored for two days to obtain single crystals. The resulting crystals were washed with ethyl acetate, dried under vacuum for further analysis. [Co(II)(CH3CN)2(L1 )](ClO4)2 (1 ⋅ (ClO4)2). HRMS: m/z=625.0938; calcd for [1‐MeCN+ ClO4 −]+ 625.0927 (mw=766.45; Ɛ=65.36 M−1 cm−1(λmax=485 nm)). [Co(II)(CH3CN)2(L2 )](ClO4)2 (2 ⋅ (ClO4)2). HRMS: m/z=631.1154; calcd for [2‐MeCN+ ClO4 −]+ 631.1145 (mw=772.46; Ɛ=71.81 M−1 cm−1 (λmax=449 nm)). [Co(II)(CH3CN)2(L3 )](ClO4)2 (3 ⋅ (ClO4)2). HRMS: m/z=578.0884; calcd for [3‐MeCN+ ClO4 −]+ 578.0880 (mw=719.4; Ɛ=79.43 M−1 cm−1 (λmax=459 nm)).

Electrochemistry

A solution of 0.1 M n‐Bu4NPF6 in anhydrous acetonitrile (Fisher Chemical, HPLC Grade) was used as electrolyte in all cyclic voltammetry experiments. All voltammograms were obtained using a three‐electrode cell under N2 atmosphere with a 3 mm diameter glassy carbon working electrode, the counter electrode was a platinum wire electrode, and the reference electrode was an Ag/AgCl electrode. All potentials are quoted against the ferrocene/ferrocenium (Fc/Fc+) potential.

X‐Ray Structure Determinations

The crystals of 1 ⋅ (ClO4)2 and 2 ⋅ (ClO4)2 were immersed in cryo‐oil, mounted in a MiTeGen loop, and measured at a temperature of 120 K on a Rigaku Oxford Diffraction Supernova diffractometer using Cu Kα (λ=1.54184 Å) radiation. The CrysAlisPro [36] program package was used for cell refinements and data reduction. Multi‐scan absorption correction (CrysAlisPro [36] ) was applied to the intensities before structure solutions. The structure of 1 ⋅ (ClO4)2 was solved with SHELXS [37] and the structure was refined with SHELXL. [38] Hydrogen atoms were positioned geometrically and constrained to ride on their parent atoms with Uiso=1.2–1.5 Ueq(parent atom). The structure of 2 ⋅ (ClO4)2 was solved by a charge flipping method using the SUPERFLIP [37] software. Structural refinements were carried out using SHELXL‐2014. [38] The oxygen atoms O7, O8, and O9 in one of the ClO4 − anions were disordered over two sites with occupancy ratio of 0.54/0.46. Cl−O distances in this disordered moiety were restrained to be similar and the Uij components of the oxygen atoms were restrained so that their Uij components approximate to isotropic behavior. The H2O hydrogen atoms were located from the difference Fourier map but constrained to ride on their parent oxygen with Uiso=1.5 Ueq (parent atom). Other hydrogen atoms were positioned geometrically and constrained to ride on their parent atoms, with C−H=0.95–0.1.00 Å, and Uiso=1.2–1.5 Ueq(parent atom). Relevant crystallographic data are collated in Table S1 (Supplementary Information). Cambridge Structural Database entries CCDC 2405896 (1 ⋅ (ClO4)2) and CCDC 2405895 (2 ⋅ (ClO4)2) contain the crystallographic data, which can be obtained free of charge from the Cambridge Crystallographic Data Centre via www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk/data_request/cif.

Photocatalysis Experiments

The visible light driven H2 evolution experiments were performed at room temperature. A suitable amount of cobalt catalyst (1–3) was added, together with the sacrificial electron donor ascorbic acid (H2A) and [Ru(bpy)3]Cl2 into a 10 mL water/acetonitrile mixture (1 : 1 v/v) in a homemade photocatalysis reactor. The reaction was carried out under irradiation by a 300 W Xenon lamp (Excelitas Technologies, PE300BFM). Bubbles emerging from the solution could be directly observed soon after turning on the light. The production of H2 was monitored with headspace sampling on an Agilent‐7820 A Gas Chromatograph using a molecular sieve column (5 Å), thermal conductivity detector, and argon carrier gas.

Nanosecond Transient Absorption Spectroscopy

Nanosecond transient absorption (ns TA) spectra were collected by applying pump pulses centered at 450 nm. The excitation pulses were produced by a Continuum OPO Plus pumped by a Continuum Surelite Nd:YAG laser system (pulse duration 5 ns, repetition rate 10 Hz). The probe light was provided by a 75 W xenon arc lamp. Spherical concave mirrors were used to focus the probe beam onto the samples and then send the beam to the monochromator (Acton, Princeton Instruments) to be subsequently detected by a photomultiplier tube (Hamamatsu R928). The signal was amplified and processed by a commercially available detection system (Pascher Instruments AB). For the ns TA measurements, the power of the pump pulses was kept at 0.3 mJ and the spectra were recorded using a short pass filter (425 nm) and a long pass filter (475 nm) to eliminate the pump scattering. The ns TA spectra were recorded in a mode that involved automatic subtraction of the emission signal for [Ru(bpy)3]2+ (at around 600 nm) from the data during the data collection. Time‐resolved emission spectra were collected with the use of a long pass filter (475 nm) and a reduced power of the pump was used (0.05 mJ). All measurements were performed in 1 cm path length fluorescence cuvettes. The optical density of the solution at the excitation wavelength (450 nm) at the given concentration was ca. 0.25.

Computational Details

For modelling of reaction pathways, all stationary points were calculated with Density Functional Theory (DFT) method using Gaussian16 software, version C.01. [42] The hybrid B3LYP functional and empirical dispersion corrections within Grimme's D3 approach were imposed in all calculations.[ 43 , 44 ] Geometry relaxation for all the chemical structures and atoms were calculated with the 6–31+G(d) basis set using a CPCM solvent model to account for solvent effects (water dielectric constant). The superfine grid was used for all calculations. Both doublet and quartet multiplicities were calculated for the Co(II) complexes, while Co(III) complexes were treated as singlets. The oxonium ion in both heterolytic hydrogen formation pathways was modelled as a oxonium‐water dimer for ion stability reasons. [Co(III)(L1 )(H2)]3+ + (H2O)2 and [Co(II)(LN )(H)]3+ + (H2O)2 relaxed geometries were unachievable at the present level of calculation and used model. Instead, a minimum energy path scan at the B3LYP−D3/6–31+G*/(water) level of theory was performed by tracking [Co(III)(L1 )(H)]3+ and H3O+ H−H distances and sequentially estimating the [Co(III)(L1 )(H2)]3+ + (H2O)3 minimum energy as well as reaction activation barriers. [Co(II)(LN )(H)]3+ + (H2O)2 is calculated as the sum of two independent energy calculations, [Co(II)(LN )(H)]3+ and (H2O)2. Estimation of the energy barrier in the Co(III)‐H homolytic cleavage, which involves change of multiplicity, was also performed by relaxed H−H scans at the doublet and quartet multiplicities.

Conflict of Interests

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

1.

Supporting information

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Acknowledgments

C.L. and Y.L. thank the China Scholarship Council for predoctoral fellowships. This research was supported by the grant CRC/TRR 234 CataLight (project number 364549901, projects A1 and Z2) funded by the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG) (to B.D.I.) and by a grant from the Sten K Johnson Foundation (to E.N.). P.P. acknowledges support from the Swedish Research Council (VR‐2021–05313), the Swedish e‐Science initiative eSSENCE, as well as the Swedish Supercomputing facilities NSC and LUNARC.

Li C., Li Y., Luo Y., Michaliszyn K., Bolaño Losada I., Hossain M. K., Elantabli F., Guo M., Hizbullah L., Tocher D. A., Haukka M., Persson P., Lloret-Fillol J., Dietzek-Ivanšić B., Nordlander E., Chem. Eur. J. 2025, e202404499. 10.1002/chem.202404499

Contributor Information

Petter Persson, Email: Petter.Persson@compchem.lu.se.

Julio Lloret‐Fillol, Email: jlloret@iciq.es.

Benjamin Dietzek‐Ivanšić, Email: benjamin.dietzek@leibniz-ipht.de.

Ebbe Nordlander, Email: ebbe.nordlander@chemphys.lu.se.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

References

- 1. Esswein A. J., Nocera D. G., Chem. Rev. 2007, 107, 4022–4047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Dalle K. E., Warnan J., Leung J. J., Reuillard B., Karmel I. S., Reisner E., Chem. Rev. 2019, 119, 2752–2875. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Tong L., Duan L., Zhou A., Thummel R. P., Coord. Chem. Rev. 2020, 402, 213079. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Zee D. Z., Chantarojsiri T., Long J. R., Chang C. J., Acc. Chem. Res. 2015, 48, 2027–2036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Wang P., Liang G., Webster C. E., Zhao X., Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2020, 2020, 3534–3547. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Canty A. J., Minchin N. J., Skelton B. W., White A. H., J. Chem. Soc. Dalt. Trans. 1986, 2205–2210. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shan B., Baine T., Ma X. A. N., Zhao X., Schmehl R. H., Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 4853–4859. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Rodenberg A., Orazietti M., Probst B., Bachmann C., Alberto R., Baldridge K. K., Hamm P., Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 646–657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Xie J., Zhou Q., Li C., Wang W., Hou Y., Zhang B., Wang X., Chem. Commun. 2014, 50, 6520–6522. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Lucarini F., Pastore M., Vasylevskyi S., Varisco M., Solari E., Crochet A., Fromm K. M., Zobi F., Ruggi A., Chem. - A Eur. J. 2017, 23, 6768–6771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. del Moral O. G., Call A., Franco F., Moya A., Nieto-Rodríguez J. A., Frias M., Fierro J. L. G., Costas M., Lloret-Fillol J., Alemán J., Mas-Ballesté R., Chem. - A Eur. J. 2018, 24, 3305–3313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Droghetti F., Lucarini F., Molinari A., Ruggi A., Natali M., Dalt. Trans. 2022, 51, 10658–10673. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Call A., Codol Z., Acuña-Parés F., Lloret-Fillol J., Chem. Eur. J. 2014, 20, 6171–6183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Sun Y., Bigi J. P., Piro N. A., Tang M. L., Long J. R., Chang C. J., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 9212–9215. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Nippe M., Khnayzer R. S., Panetier J. A., Zee D. Z., Olaiya B. S., Head-Gordon M., Chang C. J., Castellano F. N., Long J. R., Chem. Sci. 2013, 4, 3934–3945. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deponti E., Luisa A., Natali M., Iengo E., Scandola F., Dalt. Trans. 2014, 43, 16345–16353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Jurss J. W., Khnayzer R. S., Panetier J. A., El Roz K. A., Nichols E. M., Head-Gordon M., Long J. R., Castellano F. N., Chang C. J., Chem. Sci. 2015, 6, 4954–4972. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Singh W. M., Baine T., Kudo S., Tian S., Ma X. A. N., Zhou H., Deyonker N. J., Pham T. C., Bollinger J. C., Baker D. L., Yan B., Webster C. E., Zhao X., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2012, 8, 5941–5944. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Vennampalli M., Liang G., Katta L., Webster C. E., Zhao X., Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 10094–10100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Wang P., Liang G., Reddy M. R., Long M., Driskill K., Lyons C., Donnadieu B., Bollinger J. C., Webster C. E., Zhao X., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2018, 140, 9219–9229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Lo W. K. C., Castillo C. E., Gueret R., Fortage J., Rebarz M., Sliwa M., Thomas F., McAdam C. J., Jameson G. B., McMorran D. A., Crowley J. D., Collomb M.-N., Blackman A. G., Inorg. Chem. 2016, 55, 4564–4581. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Khnayzer R. S., Thoi V. S., Nippe M., King A. E., Jurss J. W., El Roz K. A., Long J. R., Chang C. J., Castellano F. N., Energy Environ. Sci. 2014, 7, 1477–1488. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mitra M., Nimir H., Demeshko S., Bhat S. S., Malinkin S. O., Haukka M., Lloret-Fillol J., Lisensky G. C., Meyer F., Shteinman A. A., Browne W. R., Hrovat D. A., Richmond M. G., Costas M., Nordlander E., Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 7152–7164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Massie A. A., Denler M. C., Cardoso L. T., Walker A. N., Hossain M. K., Day V. W., Nordlander E., Jackson T. A., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2017, 56, 4178–4182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Rana S., Biswas J. P., Sen A., Clémancey M., Blondin G., Latour J. M., Rajaraman G., Maiti D., Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 7843–7858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Rasheed W., Draksharapu A., Banerjee S., Young V. G., Fan R., Guo Y., Ozerov M., Nehrkorn J., Krzystek J., Telser J., Que L., Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2018, 130, 9531–9535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lo W. K. C., McAdam C. J., Blackman A. G., Crowley J. D., McMorran D. A., Inorg. Chim. Acta 2015, 426, 183–194. [Google Scholar]

- 28. Gueret R., Castillo C. E., Rebarz M., Thomas F., Sliwa M., Chauvin J., Dautreppe B., Pécaut J., Fortage J., Collomb M. N., Inorg. Chem. 2019, 58, 9043–9056. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Li C., Rahaman A., Lin W., Mourad H., Meng J., Honarfar A., Abdellah M., Guo M., Richmond M. G., Zheng K., Nordlander E., ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 3252–3260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Damrauer N. H., Cerullo G., Yeh A., Boussie T. R., Shank C. V., McCusker J. K., Science 1998, 11, 621–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Lewandowska-Andralojc A., Baine T., Zhao X., Muckerman J. T., Fujita E., Polyansky D. E., Inorg. Chem. 2015, 54, 4310–4321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kayanuma M., Stoll T., Daniel C., Odobel F., Fortage J., Deronzier A., Collomb M. N., Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys. 2015, 17, 10497–10509. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Solis B. H., Hammes-Schiffer S., Inorg. Chem. 2011, 50, 11252–11262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Solis B. H., Hammes-Schiffer S., J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2011, 133, 19036–19039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Muckerman J. T., Fujita E., Chem. Commun. 2011, 47, 12456–12458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Bhattacharjee A., Chavarot-Kerlidou M., Andreiadis E. S., Fontecave M., Field M. J., Artero V., Inorg. Chem. 2012, 51, 7087–7093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Jiang Y. K., Liu J. H., Int. J. Quantum Chem. 2012, 112, 2541–2546. [Google Scholar]

- 38. Bhattacharjee A., Andreiadis E. S., Chavarot-Kerlidou M., Fontecave M., Field M. J., Artero V., Chem. - A Eur. J. 2013, 19, 15166–15174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Solis B. H., Yu Y., Hammes-Schiffer S., Inorg. Chem. 2013, 52, 6994–6999. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Call A., Franco F., Kandoth N., Fernández S., González-Béjar M., Pérez-Prieto J., Luis J. M., Lloret-Fillol J., Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 2609–2619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Call A., Lloret-Fillol J., Chem. Commun. 2018, 54, 9643–9646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Prier C. K., Rankic D. A., McMillan D. W. C., Chem. Rev. 2013, 113, 5322–5363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Cai R., Yan W., Bologna M. G., de Silva K., Ma Z., Finklea H. O., Petersen J. L., Li M., Shi X., Org. Chem. Front. 2015, 2, 141–144. [Google Scholar]

- 44. Zhang X., Cibian M., Call A., Yamauchi K., Sakai K., ACS Catal. 2019, 9, 11263–11273. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

As a service to our authors and readers, this journal provides supporting information supplied by the authors. Such materials are peer reviewed and may be re‐organized for online delivery, but are not copy‐edited or typeset. Technical support issues arising from supporting information (other than missing files) should be addressed to the authors.

Supporting Information

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.