ABSTRACT

Adenosine kinase (ADK, EC: 2.7.1.20) is an evolutionarily ancient ribokinase, which acts as a metabolic regulator by transferring a phosphoryl group to adenosine to form AMP. The enzyme is of interest as a therapeutic target because its inhibition is one of the most effective means to raise the levels of adenosine and hence adenosine receptor activation. For these reasons, ADK has received significant attention in drug discovery efforts in the early 2000s for indications such as epilepsy, chronic pain, and inflammation; however, the report of adverse events regarding cardiovascular and hepatic function as well as instances of microhemorrhage in the brain of preclinical models prevented further development efforts. Recent findings emphasize the importance of compartmentalization of the adenosine system reflected by two distinct isoforms of the enzyme, ADK‐S and ADK‐L, expressed in the cytoplasm and the cell nucleus, respectively. Newly identified adenosine receptor independent functions of adenosine as a regulator of biochemical transmethylation reactions, which include DNA and histone methylation, identify ADK‐L as a distinct therapeutic target for the regulation of the nuclear methylome. This newly recognized role of ADK‐L as an epigenetic regulator points toward the potential disease‐modifying properties of the next generation of ADK inhibitors. Continued efforts to develop therapeutic strategies to separate nuclear from extracellular functions of adenosine would enable the development of targeted therapeutics with reduced adverse event potential. This review will summarize recent advances in the discovery of novel ADK inhibitors and discuss their potential therapeutic use in conditions ranging from epilepsy to cancer.

Keywords: adenosine kinase, cancer, drug discovery, epigenetics, epilepsy, metabolism

1. Introduction

The purine ribonucleoside adenosine has early evolutionary origins [1, 2] and assumes a key role as a regulator of metabolic activity [3]. Its physiological functions fall into two broad categories: it acts as a central component of several biochemical pathways [4] and it acts as an endogenous ligand of four types of G‐protein coupled adenosine receptors (A1R, A2AR, A2BR, A3R) [5] (Figure 1). Given its multiple functions as a metabolite and signaling molecule, its levels need to be under tight metabolic control. Major sources of adenosine formation include the degradation of ATP, ADP, and AMP into adenosine via a sophisticated network of extracellular and intracellular nucleotidases including CD39 and CD73 (extracellular) and 5'‐nucleotidase (intracellular) [4] (Figure 2). A second major source of adenosine is the cleavage of S‐adenosylhomocysteine (SAH), a product of the transmethylation pathway (see below) into adenosine and homocysteine through SAH hydrolase. The production of adenosine needs to be counterbalanced through its metabolic clearance, which is controlled by two enzymes: Adenosine deaminase (EC 3.5.4.4) is a high‐capacity, low‐affinity enzyme (K m for adenosine of 0.1 mM and an apparent V max for NH3 formation 1.5 μmol per minute per milligram of protein) that deaminates adenosine into inosine as a first step of the purine degradation pathway. Adenosine kinase (EC 2.7.1.20) is a low‐capacity, high‐affinity enzyme (K m for adenosine of 0.2–0.4 μM and an apparent V max of 2.2 μmol of AMP formed per minute per milligram of protein) that phosphorylates adenosine into AMP and thus replenishes the AMP/ADP/ATP pool [6, 7]. Due to its high affinity for adenosine, under physiological conditions, ADK assumes a role as the key metabolic regulator of adenosine [6, 7]. Therefore, ADK has emerged as an important therapeutic target to raise tissue levels of adenosine in conditions such as epilepsy, chronic pain, and inflammation [8, 9, 10, 11, 12]. The human Adk gene has a remarkable size of 546 kb with a coding sequence of only about 1.1 kb encoding two alternatively spliced isoforms of ADK with sequence‐derived molecular masses of 38.7 (ADK‐S) and 40.5 kDa (ADK‐L), which differ in their N‐terminal 21 amino acids [13]. In the following, the different functions of ADK and their implications and opportunities for drug development will be discussed.

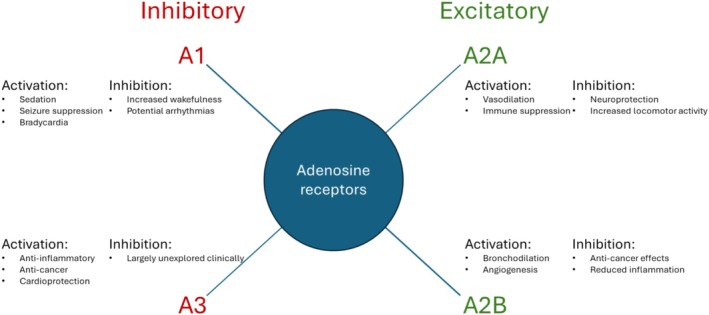

FIGURE 1.

Main functions of adenosine receptors. A1 and A3 receptors mediate the inhibitory roles of adenosine, whereas A2A and A2B receptors mediate the excitatory/stimulatory roles of adenosine. A selection of clinically relevant effects achieved by receptor activation or inhibition is shown.

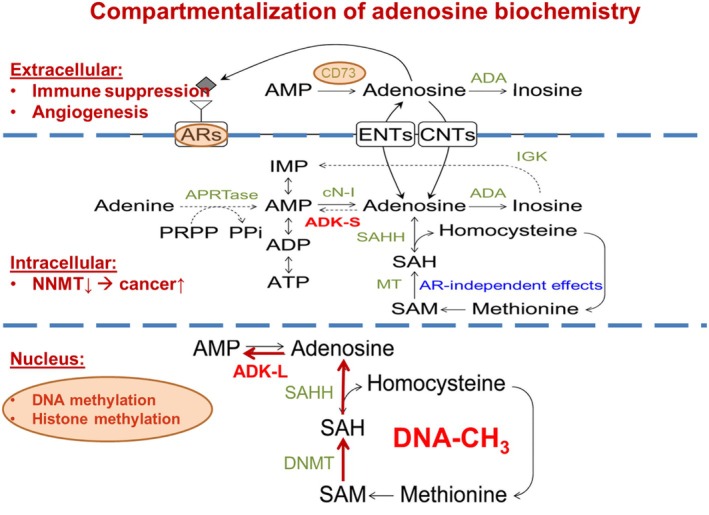

FIGURE 2.

Compartmentalization of the adenosine system and major adenosine generating and consuming pathways. Extracellular purine turnover affects adenosine receptor (AR) activation, which plays important roles in immune suppression and angiogenesis, and includes adenosine‐producing (ecto‐5′‐nucleotidase/CD73) and ‐removing pathways (adenosine deaminase, ADA). Extra‐ and intracellular levels of adenosine are exchanged via equilibrative (ENT) and concentrative (CNT) nucleoside transporters. Intracellular adenosine metabolism depends on the cytoplasmic form of adenosine kinase (ADK‐S), and the enzymes ADA, cytosolic nucleotidase (cN‐I), and adenine phosphoribosyl transferase (APRTase). Hydrolysis of S‐adenosylhomocysteine (SAH) can be a major source for adenosine and homocysteine (HCy) by SAH hydrolase (SAHH), while S‐adenosylmethionine (SAM) serves as the donor of a methyl group in the transmethylation reactions catalyzed by methyltransferases (MT). One of the methyltransferases potentially affected by this mechanism is nicotinamide N‐methyltransferase (NNMT) whose inhibition has been linked to cancer. In the cell nucleus, adenosine is part of the transmethylation pathway, which adds methyl groups to DNA (DNA‐CH3) with DNA methyltransferase (DNMT). The nuclear form of adenosine kinase (ADK‐L) drives the flux of methyl groups through the pathway leading to increased DNA and histone methylation. For the sake of clarity, only the most important enzymes are mentioned.

2. Adenosine Kinase (ADK)

2.1. ADK—Regulator of Energy Homeostasis

Due to its link to ATP and energy homeostasis, adenosine has been termed a “retaliatory metabolite” [3]. This concept makes sense from an evolutionary perspective. One of the most important challenges at the origin of life was the development of a simple regulatory system that adjusts energy demands to energy supplies. Thus, any drop in ATP, reflecting an energy crisis, would produce more adenosine, which then acts globally to suppress processes that consume energy. In line with this principle, adenosine promotes sleep and stops epileptic seizures. From an energetic standpoint, an epileptic seizure manifests as a physiological state of excessive energy consumption, resulting in a robust increase in adenosine, which acts as the brain's endogenous seizure terminator as a means to conserve energy [6, 7, 14, 15]. ADK, as a key regulator of adenosine, has early evolutionary origins that trace back to bacterial ribokinases before the advent of the adenosine receptors [16, 17]. Thus, an early substrate cycle between adenosine and AMP catalyzed by 5'‐nucleotidase and ADK might have formed an evolutionarily ancient system for the regulation of ambient levels of adenosine [18]. Ongoing substrate cycling would enable minor changes in ADK activity to rapidly translate into major changes in adenosine concentration.

Several mechanisms contribute to the unique properties of ADK to act as a regulator of energy homeostasis. Based on the catalyzed reaction: adenosine + ATP ➔ AMP + ADP, the enzyme binds all energy metabolites and is directly regulated by its substrates ATP, ADP, AMP, and adenosine [6, 7]. Importantly, ADK is inhibited by its own substrate adenosine. This implies that once adenosine levels reach a certain threshold, the enzyme shuts down, enabling it to further potentiate a rapid adenosine response when needed. Studies on Leishmania ADK have revealed an interesting regulatory mechanism [19]. In Leishmania, the enzyme exists as an active monomer, stabilized by a cyclophilin, and an inactive aggregate, which can either feed into a degradation pathway or be brought back to the active monomeric form through interaction with the cyclophilin. Importantly, ADP induces aggregate formation and inactivation of the enzyme [19]. Thus, any energy crisis leading to a drop in ATP will result in the formation of more ADP and thereby promote aggregation and rapid inactivation of the enzyme and the accumulation of adenosine. Through this unique mechanism and the inhibitory properties of adenosine, ADK is uniquely suited to rapidly adjust energy demands to energy supplies.

An additional mechanism through which ADK is linked to energy homeostasis is through AMPK, which serves to monitor the cellular energy charge and which is able to act as a switch to regulate ATP concentrations under conditions of energy stress, which reduce ATP levels [20]. Because ATP levels are 100 000 fold higher than adenosine levels, AMPK responds primarily to a drop in ATP [21]. However, extracellular adenosine can also act as a substrate for AMPK activation, following its intracellular transport and phosphorylation by ADK [22]. The adenosine analog AICAR (5‐aminoimidazole‐4‐carboxamide ribonucleoside) is a well characterized activator of AMPK. Its intracellular uptake through nucleoside transporters is followed by phosphorylation through ADK to form zeatin riboside‐5‐monophosphate (ZMP), which mimics the stimulatory action of AMP on AMPK [23]. This mechanism is of translational interest because AICAR is known to exhibit protective effects on the vasculature and vasorelaxation through activation of AMPK. It was recently shown that this process requires ADK and the formation of AMPK‐activating ZMP [24]. Thus, ADK has a dual role in fine‐tuning energy homeostasis.

(i) Directly through the regulation of adenosine and (ii) through modulation of AMPK.

2.2. ADK—Regulator of Transmethylation

Transmethylation involves the transfer of a methyl group from S‐adenosylmethionine (SAM) to a highly diverse group of acceptor molecules, including, for example, phosphatidylethanolamine, dopamine, and DNA. The resulting product SAH is cleaved by SAH hydrolase into homocysteine and adenosine. Importantly, the thermodynamic equilibrium of the SAH hydrolase reaction lies on the side of SAH formation. Thus, the reaction can only proceed if the products homocysteine and adenosine are effectively removed. Homocysteine feeds back into the methionine cycle catalyzed by methionine synthase, whereas adenosine is effectively phosphorylated by ADK and moved back into the adenosine cycle (Figure 3). Reduced activity of methionine synthase or ADK results in the accumulation of SAH, which acts as an inhibitor of methyltransferases [25]. A key role of ADK as a regulator of transmethylation reactions is supported by findings in gene knockout models and in human mutations of the Adk gene. The genetic disruption of the Adk gene in mice and in plants led to remarkably similar defects in the transmethylation pathway, resulting in developmental abnormalities and stunted growth in mice and plants, and in hepatic steatosis in mice [25, 26]. Similarly, humans with mutations in the Adk gene presented with transmethylation defects, stunted growth, and developmental abnormalities [27]. Thus, the chronic therapeutic long‐term use of ADK inhibitors could cause hypermethioninemia and cause liver pathology. A recent case report suggested therapeutic benefits of methionine restriction in a patient with inborn ADK deficiency [28]. Because ADK is an essential enzyme for the maintenance of transmethylation reactions, its expression is tightly linked to methylation. Thus, the liver, which is the major transmethylation organ of the body and which is responsible for the production of methylated lipids, such as the methylation of phosphatidylethanolamine to phosphatidylcholine, is also the organ with the highest expression levels of ADK. In the cell nucleus, ADK‐L plays a newly identified role as a regulator of DNA methylation [29, 30]. DNA methylation is an important component of the cell cycle. During the S‐phase, all newly formed DNA needs to be methylated, a process which requires a high flux rate of methylation reactions during a brief time span. Therefore, one role of ADK‐L in the nucleus is to support DNA methylation in replicating cells. In support of this recently identified function of ADK, ADK‐L expression in the brain is restricted only to dividing and plastic cells, whereas mature neurons, which no longer divide, do not express ADK‐L [31, 32, 33, 34]. Therefore, ADK‐L emerges as a novel therapeutic target for the regulation of DNA methylation [30, 35].

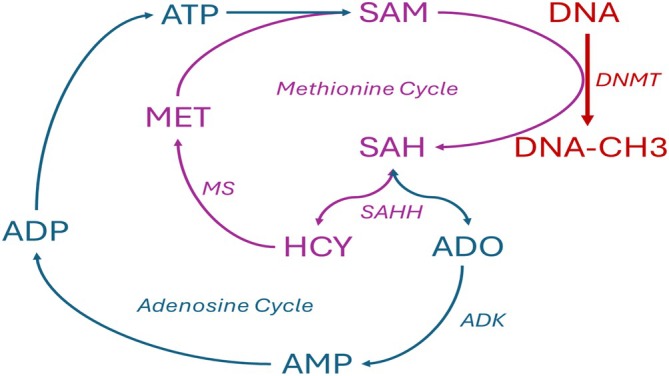

FIGURE 3.

DNA methylation catalyzed by DNA methyltransferases (DNMT) is biochemically linked to the methionine and adenosine cycles. Methyl groups are supplied by S‐adenosylmethionine (SAM), which after the donation of a methyl group to DNA, is converted into S‐adenosylhomocysteine (SAH). The SAH hydrolase (SAHH) reaction which can cleave SAH into adenosine (ADO) and homocysteine (HCY) is bidirectional, with the thermodynamic equilibrium on the site of SAH formation. SAH, in turn, is an inhibitor of DNMTs. The SAH reaction can proceed only toward cleavage and permit DNA methylation if the products ADO and HCY are effectively removed. SAH feeds into the methionine cycle and is converted by methionine synthase (MS) converts HCY into methionine (MET), which upon reaction with ATP, replenishes the pool of SAM. ADO is removed by adenosine kinase (ADK), which feeds adenosine back into the adenosine cycle, which replenishes ATP via AMP and ADP.

2.3. ADK—Regulator of Extracellular Adenosine

Extra‐ and intracellular levels of adenosine are equilibrated through ubiquitous equilibrative (ENT) and concentrative (CNT) nucleoside transporters [36]. Therefore, intracellular ADK is enabled to play a major role in regulating extracellular levels of adenosine and hence adenosine receptor activation [4]. Accordingly, increasing ADK‐S expression in the brain of mice through transgenic or viral tools was shown to reduce the tissue tone of adenosine and thereby trigger seizures through reduced activation of inhibitory A1Rs and to increase the susceptibility to neuronal injury [37, 38, 39, 40, 41, 42]. Conversely, the ADK inhibitor 5‐iodotubercidin (5‐ITU) suppressed epileptic seizures in mice, a therapeutic effect that could be reversed by blocking the A1R with 8‐cyclopentyl‐1,3‐dipropylxanthine (DPCPX) [43]. In line with these findings, it was shown that ADK expression in astrocytes is primarily responsible for the regulation of basal synaptic adenosine levels and seizure activity, whereas activity‐dependent adenosine release in the hippocampus was not under the control of ADK [37]. This makes sense because mature neurons normally do not express ADK [33, 34], a likely prerequisite that permits activity‐dependent adenosine release by neurons [44]. Together, these findings are in line with a compartmentalization of the adenosine system into distinct pools of adenosine: a global tissue tone of adenosine, controlled by astroglial ADK, that provides tonic network inhibition through activation of A1Rs, and an independent synaptic pool of adenosine that permits plasticity changes on the individual synaptic level through activation of pre‐and postsynaptic A2ARs [45].

2.4. ADK—A Tale of Two Isoforms

Compartmentalization of the adenosine system is further refined by the existence of two distinct isoforms of ADK derived from the same unique Adk gene through alternative splicing and alternative promoter use [46]. The short isoform ADK‐S is located in the cytoplasm, whereas the long isoform ADK‐L differs only by the attachment of a 21 amino acid N‐terminal nuclear localization signal that directs ADK‐L expression to the cell nucleus [46]. This compartmentalization of ADK expression allows ADK‐S to regulate intra‐ and extracellular levels of adenosine and hence adenosine receptor activation, whereas intranuclear ADK‐L plays a specific role in the regulation of nuclear transmethylation pathways, which affect DNA and histone methylation [4, 6, 7]. In line with the compartmentalization of ADK expression, transgenic mice expressing the cytoplasmic isoform ADK‐S in the brain, in the absence of ADK‐L, were characterized by an adenosine deficiency phenotype and seizures due to reduced activation of A1Rs [47]. Conversely, overexpression of ADK‐L was shown to increase global DNA methylation [30].

3. Role of ADK in the Brain

Adenosine is a broad modulator of brain activity whereby adenosine‐based activation of A1 receptors provides an inhibitory environment which increases seizure thresholds and which is neuroprotective [48]. This inhibitory environment permits enhanced salience for A2A receptor mediated excitatory function on the synaptic level, which is of importance for plasticity phenomena [45]. The role of adenosine in the brain has most extensively been studied within the context of epilepsy, stroke, and sleep [48]. It is now well recognized that epilepsy is a disorder with metabolic derangements that affect energy homeostasis and utilization [49]. As outlined above, adenosine and its regulating enzyme ADK play a major role in maintaining an energy balance and for these reasons, metabolic derangements in epilepsy are associated with maladaptive overexpression of ADK, resulting in chronic adenosine deficiency and seizures in the epileptic brain [49]. Consequently, metabolic interventions including restoration of normal ADK function are of interest for the treatment and prevention of epilepsy [49]. ADK, as a major regulator of ambient adenosine, is also implicated in the regulation of sleep, and mice with increased expression of ADK in the brain have profound sleep alterations [50]. In line with these findings, ADK inhibitors are sedative and have sleep inducing properties.

3.1. ADK—Target for Drug Development

Extracellular adenosine provides a broad range of benefits through activation of ARs. Those include seizure suppression, neuroprotection, anti‐inflammatory activity, and pain control [51]. Because intracellular ADK regulates extracellular adenosine and because several pathologies, including epilepsy and neurodegenerative conditions, are characterized by maladaptive overexpression of ADK [52], there is a strong rationale for the development of ADK inhibitors to enhance extracellular adenosine in a site‐ and event‐specific manner [9, 10]. In line with this rationale, the early 2000s have seen widespread drug discovery and development efforts to establish ADK inhibitors as a novel therapeutic approach for the treatment of epilepsy, chronic pain, and inflammatory conditions [8, 10, 53]. Although the first generation of ADK inhibitors was highly efficacious in preclinical studies of the indications mentioned above, further drug development efforts were halted due to risks of adverse events, including liver toxicity and microhemorrhage foci in the brain [54]. It is important to point out that past drug discovery efforts were based on screens to identify compounds that increase extracellular adenosine and enhance adenosine receptor signaling. This strategy created an implicit bias for the identification of compounds exerting their biological activities primarily through inhibition of ADK‐S. In addition, the therapeutic indications of epilepsy, chronic pain, and inflammation would require sustained long‐term treatment, which increases the risk of chronic toxicities and adverse events.

3.2. ADK‐Based Therapeutics in Epilepsy

Adenosine acts as the brain's endogenous anticonvulsant and seizure terminator; seizures normally stop because seizures lead to the generation and release of adenosine, which attenuates neurotransmission through presynaptic and postsynaptic adenosine A1Rs [14, 15, 55]. In line with this protective role of adenosine, adenosine augmentation therapies (AATs) constitute a rational approach for seizure control [56], an approach first demonstrated in vivo through the implantation of adenosine‐releasing polymers into the brain ventricles of kindled rats [57]. In addition, ADK is pathologically upregulated in the epileptic brain; therefore, ADK has been identified as a target for the prediction and prevention of epileptogenesis in mice [58, 59, 60, 61]. Recent advances in our understanding of the role of the two different ADK isoforms in health and disease have led to renewed interest in the identification of novel ADK inhibitors [35, 62]. Several new findings discussed here are expected to broaden the potential future use of ADK‐based therapeutics.

Whereas past drug development efforts had focused on the chronic use of ADK inhibitors as symptomatic treatments, new research suggests that the transient short‐term use of ADK inhibitors has lasting disease‐modifying properties. Thus, a transient dose of the nonselective ADK inhibitor 5‐ITU (1.6 mg/kg i.p. b.i.d.) given for only 5 days beginning 3 days after an epilepsy‐triggering status epilepticus in mice led to > 95% seizure reduction in 59% of the 5‐ITU treated mice as evaluated 5 to 8 weeks after the transient dose of 5‐ITU [63]. These data demonstrate lasting disease‐modifying beneficial effects of transient ADK blockade, which are likely based on an epigenetic mechanism [30]. Several studies support the role of epigenetic mechanisms in the etiology of epilepsy development [64, 65, 66, 67, 68]. In line with these findings, epigenetic reprogramming through transient intervention has been shown to exert lasting disease‐modifying effects [30, 64]. For example, the polD1 gene was found to be hypermethylated in a rat model of temporal lobe epilepsy, whereas a transient treatment with adenosine for only 10 days yielded a lasting reversal of the DNA methylation status at distinct methylation sites identified by reduced representation bisulfite sequencing [30]. These findings imply that transient side effects of ADK inhibitors such as sedation might be acceptable if long‐term benefit is to be expected.

Because lasting disease modifying effects of adenosine are based on an epigenetic mechanism governed by ADK‐L [30] and because cardiovascular and sedative side effects of adenosine can be linked to increased activation of adenosine receptors [4], there is a strong rationale for the development of ADK inhibitors that target DNA and histone methylation by blocking ADK‐L [35]. Novel inhibitors with preferential inhibition of ADK‐L over ADK‐S are expected to capitalize on desired epigenetic reprogramming while minimizing adenosine receptor mediated side effects. Preferential inhibition, as opposed to target selectivity, would be sufficient to shift the equilibrium between desired effects (mediated by both isoforms) and side effects (linked to ADK‐S) toward increased benefits with reduced side effect potential.

Accordingly, as noted above, a lead compound—MRS4203—was identified whose synthesis prioritizes the south over the north configuration of (N)‐methano‐carba‐7‐deaza‐adenosine analogs of the ADK inhibitor 5‐ITU [35]. It was found to exert potent ADK inhibition with a maximal inhibitory concentration (IC50) value of 88 nmol/L and, interestingly, at a concentration of 26 nmol/L, greater than one‐half of global DNA methylation was reduced in ADK‐L genetically engineered cells which do not express ADK‐S (unpublished findings). A pertinent advantage is the side effect profile of the newly modeled drug compared to its parent molecule. Initial findings suggest that MRS4203, when compared to the non‐selective parent molecule 5‐ITU, was not associated with major sedative side effects. While more work is needed to understand the pharmacokinetics, metabolism, drug interactions, toxicity, efficacy, and tolerability of MRS4203, its preferential activity on ADK‐L might be the basis for the avoidance of adverse effects associated with ADK‐S inhibition, such as sedation and cardiovascular side effects. The molecular and structural basis for preferential activity on either ADK‐S or ADK‐L is currently unknown; however, the complexity of the nuclear pore might provide a filter for drug penetration into the nucleus by certain compounds [69, 70, 71, 72, 73]. In addition, in vivo ADK is known to form tight associations with other proteins. These protein–protein interactions play a role in the regulation of enzyme activity [19, 74]. Differences in cytosolic versus nuclear protein interaction partners may explain different kinetic properties of the enzyme isoforms in vivo. An alternative to the use of small molecule inhibitors is antisense oligonucleotides (ASOs), which can use sequence‐derived motifs to confer target selectivity.

3.3. Lessons Learnt From the Clinical Use of Metabolic Therapies

Because ADK inhibitors are currently not in clinical use, it is not possible to gain clinical insights into the potential benefits of ADK manipulation. However, metabolic therapies, which are in widespread clinical use, might provide answers. Metabolic therapies work through a combination of various mechanisms, which converge in lasting disease‐modifying properties through metabolic and epigenomic reprogramming [49]. Metabolic therapies are best known through the use of the high‐fat, low‐carbohydrate ketogenic diet (KD), which has been in use for the treatment of epilepsy for more than 100 years and which is currently experiencing a surge in use to treat multiple conditions including psychiatric conditions, diabetes, and cancer [75, 76]. Importantly, clinical reports show that a transient use of KD therapy in children with epilepsy can yield lasting seizure freedom after discontinuation of the diet [77, 78, 79]. Likewise, rodent models of epilepsy have demonstrated lasting disease‐modifying effects of KD therapy mediated through an epigenetic mechanism [64, 80]. In line with these findings, multiple studies have shown that KD therapy elevates adenosine [47, 80, 81, 82, 83, 84] and reduces adenosine kinase expression [47]. Together, these findings support the hypothesis that lasting disease‐modifying effects after discontinuation of KD therapy in the clinic can best be explained through an epigenetic mechanism mobilized by an increase in adenosine.

3.4. Lessons Learnt From Neurostimulation

Neurostimulation strategies using implanted devices are increasingly used in the clinic to treat a variety of conditions including epilepsy, Parkinson's disease, and psychiatric conditions. Among these therapies, deep brain stimulation [85, 86, 87, 88] and vagus nerve stimulation (VNS) [89, 90, 91] are used most frequently. Converging lines of evidence suggest that neurostimulation triggers the release of adenosine [92, 93, 94]. Interestingly, genetic variations of the Adk gene have been identified as a predictable biomarker for the efficacy of VNS treatment. It was found that following VNS treatment, all patients in the study population with minor allele homozygosity in certain Adk single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) [homozygous rs11001109 (AA) and rs946185 (AA); minor allele rs7899674 (CG + GG)] achieved at least 50% seizure reduction while 40% of the patients achieved seizure freedom [95]. Interestingly, the same SNP in the Adk gene was identified as a predictor for increased risk of developing posttraumatic epilepsy after a brain injury [96]. While these discoveries highlight a pertinent role of ADK for electrical neuromodulation approaches, they support the notion that the enzyme is intricately involved in the pathogenesis of epilepsy.

3.5. Lessons Learnt From Gene Therapy

Gene therapy involving RNA‐based therapeutic agents including anti‐sense oligonucleotides (ASOs) is limited in their propensity to cross the blood–brain barrier [97, 98, 99]. Recently, a novel anti‐epileptic drug delivery strategy to target ADK has been proposed, which involves a nucleic acid‐based nano‐antiepileptic compound (tFNA‐ADKASO@AS1) whose moieties consist of a tetrahedral framework nucleic acid (tFNA), incorporating an antisense oligonucleotide targeting ADK (ADKASO) and a peptide designed to target A1 receptors in astrocytes (AS1) [100]. Through this approach by silencing astroglial ADK, it was possible to therapeutically augment endogenous adenosine while still maintaining a favorable neuro‐toxic profile in addition to superior blood‐brain barrier penetration. Strikingly, in mice with kainic acid‐induced epilepsy, this strategy resulted in a robust reduction in recurrent spontaneous epileptic spike frequency and the attenuation of unregulated mossy fiber sprouting. Additional studies are needed to evaluate the long‐term translational benefits of this novel gene therapeutic approach.

4. The Role of Adenosine and ADK in Cancer

Because of its early evolutionary origin, it is not surprising that adenosine and its dysfunction are implicated in a broad spectrum of pathologies. Commonalities between adenosine dysfunction in epilepsy, Alzheimer's disease, and Parkinson's disease have already been mentioned, but adenosine also plays a well‐recognized role in apparently disparate conditions, such as cancer. Both epilepsy and cancer present as plasticity disorders, in which cells assume a more premature, more plastic state, which enables aberrant neurogenesis (in epilepsy) or cell proliferation (in cancer) and in general a more plastic behavior of cells that enables morphological restructuring of the brain (in epilepsy) and metastasis (in cancer). In the following, we will discuss the implication of the extracellular and intranuclear adenosine system in cancer.

The adenosine system plays a well‐recognized role in cancer biology, where extracellular adenosine contributes to the suppression of immune functions in the tumor microenvironment and stimulates angiogenesis. For these reasons, extracellular adenosine‐producing enzymes and A2AR antagonists are promising therapeutic targets as immune checkpoint regulators [101, 102]. However, as indicated above, the adenosine system is highly compartmentalized, and intracellular ADK contributes to the regulation of extracellular adenosine levels. Gaps in knowledge that impede the development of effective adenosine‐based therapeutics include a lack of distinction between adenosine receptor‐dependent and ‐independent effects of adenosine and the current focus on extracellular adenosine without consideration of intracellular metabolism and compartmentalization [4]. Adenosine plays three distinct roles in cancer biology [4, 103].

Extracellular adenosine, regulated by extracellular adenosine‐producing enzymes such as CD39 and CD73, as well as by intracellular metabolism through ADK (Figure 2) acts as an important immune checkpoint regulator [104]. Tumor cells produce and release copious amounts of adenosine into the tumor microenvironment and thereby block immune function and promote angiogenesis via increased activation of the A2AR. Therefore, therapeutic strategies that reduce adenosine production, increase adenosine metabolism, or block A2AR activation have therapeutic merit [41, 105, 106, 107]. Because increases in adenosine‐producing CD73 and enhanced A2AR signaling are considered potent suppressors of anti‐tumor responses [108], multiple phase I and II clinical trials are underway to study the therapeutic effectiveness of CD73 antibodies and small molecule A2AR blockers [4, 103, 109]. With the goal to restore immune functionality and to facilitate antitumor immunity, CD73 is commonly targeted with antibodies, for example, with the monoclonal antibody oleclumab (MEDI9447) which has been used in multiple clinical trials for a variety of advanced solid cancers including breast cancer [110, 111, 112, 113, 114, 115, 116, 117, 118, 119]. The second most common approach for blocking the ADO pathway is inhibitors of the A2ARs, an approach that yielded multiple clinical trials [4, 103, 109]. While data from both approaches are still limited, adenosine pathway blockers appear to be well tolerated and show moderate efficacy in a subset of patients. While the results are encouraging, they also indicate possible avenues for improved responses, which could be realized by targeting the ADO system more comprehensively by including the manipulation of intracellular adenosine metabolism via ADK. In line with a role of adenosine in cancer biology, ADK appears to be dysregulated at least in several types of cancer [120, 121]. Based on this rationale, ADK emerges as a target for the development of novel cancer therapeutics. For example, a therapeutic increase in ADK‐S, as could be achieved by an ADK‐S gene therapy, would turn a cancer cell into a metabolic sink for adenosine by driving the influx of adenosine from the extracellular space into the cell [103]. This strategy could theoretically deprive a cancer of its ability to suppress immune functions while limiting its potential for angiogenesis. Thus, in hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) it was shown that adenosine accumulation through effects of hypoxia‐inducible factor 1 (HIF‐1) in response to the hypoxic tumor microenvironment could promote liver cancer development [122]. The increase in adenosine concentration was associated with an increase in immunosuppressive effects on T cells and myeloid cells, which play a protective anti‐inflammatory and pro‐immunogenic role [102]. Consequently, in HCC, it has been reported that mice treated with adenosine receptor antagonists and anti‐PD‐1 (programmed cell death protein 1) monoclonal antibodies experienced prolonged survival [122].

A beneficial effect of extracellular adenosine from a therapeutic standpoint is the promotion of apoptosis [123, 124]. Thus, extracellular adenosine has the capability to combine detrimental (suppression of immune function, promotion of angiogenesis) with beneficial (induction of apoptosis) effects, which need to be considered for therapy development. With respect to the pro‐apoptotic function of adenosine, it was shown that adenosine suppressed the growth of SW620 and SW480 cells through G2/M phase arrest while inducing apoptosis [125]. It was further shown that adenosine can trigger cell death in colon cancer cells via the tumor necrosis factor pathway [125]. This finding suggests that ADK inhibitors as cancer therapeutics might be beneficial by promoting adenosine‐induced apoptosis. Various studies have reported a role of adenosine in inducing apoptosis in breast cancer cell lines [126, 127] Tsuchiya et al. found that an MCF‐7 human breast cancer cell line treated with the ADK inhibitor ABT‐702 showed adenosine‐induced apoptosis in a receptor‐independent manner [127]. It was shown that adenosine by itself could trigger the intrinsic apoptotic pathway after its transportation from the extracellular to the intracellular compartment. Apoptosis in MCF‐7 cells was associated with the accumulation of apoptosis‐inducing factor (AIF)‐homologous mitochondrion‐associated inducer of death (AMID) in the nucleus through a caspase‐independent mechanism [127]. More recent investigations on the effect of ADK in breast cancer, however, have shown that while ADK downregulation could potentially suppress breast cancer cell proliferation and viability, the two different isoforms of ADK may play different roles in tumorigenesis and cancer development [120].

Adenosine concentrations in the cell nucleus depend on adenosine production during the S‐phase of the cell cycle and on metabolic clearance through ADK‐L. Therefore, ADK‐L acts as a regulator of the cell cycle and modulator of DNA and histone methylation modifications [4, 30, 103, 128, 129]. The epigenetics of cancer, which includes changes in DNA and histone methylation signatures, as well as their interplay, plays a key role in driving the high proliferative rate of cancer cells [11, 130, 131, 132, 133, 134, 135]. A direct role for ADK‐L in the regulation of cell growth and differentiation is supported by findings in the brain. In the adult brain, ADK‐L is only expressed in cells capable of dividing and regenerating, whereas mature (non‐dividing neurons) cease to express ADK‐L [6, 7, 34]. During brain development (i.e., during a transition from growth and plasticity to terminal differentiation) there is a coordinated shift from ADK‐L to ADK‐S expression [33, 34]. We propose that high levels of ADK‐L promote cell proliferation and maintenance of a de‐differentiated cell fate. Therefore, small molecule drugs or antisense oligonucleotides designed to target ADK‐L have potential as possible therapeutics for cancer.

5. Adenosine and ADK in Inflammation

An inflammatory micro‐environment can promote tumorigenesis through increased production of reactive oxygen species (ROS) which can have a debilitating effect on mismatch repair enzymes [136]. In chronic inflammatory vasculopathies such as atherosclerosis, the role of ADK inhibition has been explored. In an experiment investigating the role of ADK homeostasis in foam cell formation and subsequent development of atherosclerotic plaques, it was discovered that mice lacking ADK in myeloid cells had a reduced propensity to form plaques through epigenetic regulation of cholesterol flux [137]. In acute inflammatory conditions like acute kidney injury, secondarily mediated by hypoxia following ischemia–reperfusion, the degree of acute tubular necrosis was directly proportional to the extent of ADK expression [138]. It was posited that ADK inhibition could ameliorate ischemia reperfusion‐induced kidney injury by increasing tissue adenosine levels while reducing oxidative stress [138]. Likewise, in conditions such as diabetic nephropathy, diabetic retinopathy, and ischemic cerebrovascular disease, the protective role of ADK inhibitors in increasing adenosine levels has been described [129, 139, 140]. Most recently, in a mouse model of calcium chloride and angiotensin II‐induced abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) it was reported that the ADK inhibitor ABT702 displayed a protective role [141]. A virus‐induced ADK knockdown in human vascular smooth muscle cells led to decreased expression of inflammatory genes involved in an AAA through an adenosine‐receptor‐independent mechanism [141]. These findings point to the wide‐ranging role of adenosine and ADK inhibitors in the inflammatory process, which includes adenosine receptor‐independent epigenetic mechanisms.

6. Conclusions and Outlook

It has become clear that the adenosine system is highly compartmentalized into extracellular, intracellular, and intranuclear compartments. Increasing extracellular adenosine and the resulting activation of adenosine receptors is of therapeutic value for the treatment of symptoms in epilepsy, pain, and inflammation; however, adenosine receptors can also mediate side effects of therapeutic adenosine augmentation (Figure 1). A novel concept is the consideration of additional adenosine receptor independent functions of adenosine as a biochemical metabolite, most notably as a product of methylation reactions, which include DNA methylation. These findings add to the complexity of the adenosine system, offer novel therapeutic strategies in the realm of disease modification, but also pose new challenges. The ubiquitous nature of adenosine metabolism and signaling offers wide‐ranging therapeutic implications for multiple organ systems and disease states (Figure 4). Being a central node of the evolutionary ancient adenosine system, ADK has recently received increased attention as a therapeutic target for a wide range of conditions ranging from epilepsy to cancer. Gaps in knowledge and a lack of distinction between the different compartments of adenosine (extracellular, intracellular, intranuclear) impeded the development of effective therapeutics in the past. Novel tools such as gene therapy or antisense oligonucleotide might be able to target the adenosine system more effectively in a cell‐type selective or cellular compartment selective manner. One proposed strategy to separate intracellular from extracellular effects of adenosine would be the combination of an ADK inhibitor with an adenosine transport inhibitor with the goal to trap the increased adenosine inside the cell, without affecting extracellular adenosine.

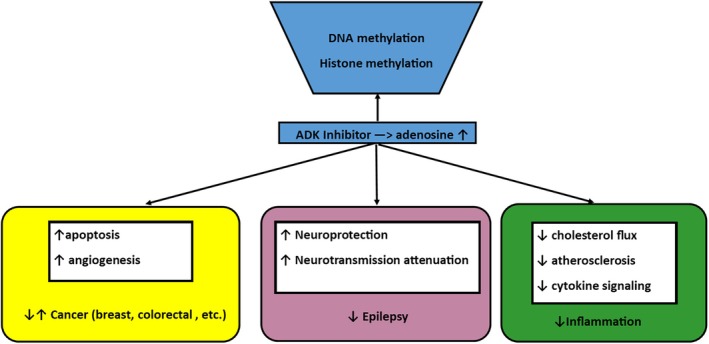

FIGURE 4.

Simplified diagram showing the role of adenosine and ADK inhibitors in various disease states (ADK = adenosine kinase).

Gaps for the future clinical translation of ADK based therapeutics include: (i) With the exception of metabolic therapies and strategies to target the adenosine pathway in cancer, there is a paucity of supporting clinical data available; (ii) although mixed ADK inhibitors with preferential activity on ADK‐L are expected to be therapeutically beneficial, from a medicinal chemistry perspective, it will be challenging to develop a selective inhibitor for each of the isoforms of ADK; (iii) although some of the target genes affected by therapeutic adenosine augmentation or by metabolic strategies have been identified, a deeper understanding of the epigenetic landscape affected by therapeutic manipulations is needed. The development of therapeutics to reconstruct metabolic mechanisms in disease is a new frontier in therapy development that offers treatment of intractable conditions in a more holistic manner.

Author Contributions

Detlev Boison: conceptualization, writing, and reviewing of manuscript. Uchenna Peter‐Okaka: writing and reviewing of manuscript.

Consent

The authors have nothing to report.

Conflicts of Interest

Detlev Boison is co‐founder and CDO of PrevEp Inc. Uchenna Peter‐Okaka declares that he has no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

This work was funded through grants NS127846 and NS065957 from the NIH and through contract W81XWH2210638 from the US Department of the Army.

Communicating Editor: Ron A Wevers

Funding: This work was funded through grants NS127846 and NS065957 from the NIH and through contract W81XWH2210638 from the US Department of the Army.

References

- 1. Oro J., “Mechanism of Synthesis of Adenine From Hydrogen Cyanide Under Possible Primitive Earth Conditions,” Nature 191 (1961): 1193–1194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Oro J. and Kimball A. P., “Synthesis of Purines Under Possible Primitive Earth Conditions. I. Adenine From Hydrogen Cyanide,” Archives of Biochemistry and Biophysics 94 (1961): 217–227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Newby A. C., “Adenosine and the Concept of Retaliatory Metabolites,” Trends in Biochemical Sciences 9 (1984): 42–44. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Boison D. and Yegutkin G. G., “Adenosine Metabolism: Emerging Concepts for Cancer Therapy,” Cancer Cell 36 (2019): 582–596. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fredholm B. B., Ijzerman A. P., Jacobson K. A., Linden J., and Muller C. E., “International Union of Basic and Clinical Pharmacology. LXXXI. Nomenclature and Classification of Adenosine Receptors ‑ An Update,” Pharmacological Reviews 63 (2011): 1–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Boison D., “Adenosine and Seizure Termination: Endogenous Mechanisms,” Epilepsy Currents 13 (2013): 35–37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Boison D., “Adenosine Kinase: Exploitation for Therapeutic Gain,” Pharmacological Reviews 65 (2013): 906–943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Erion M. D., Wiesner J. B., Rosengren S., Ugarkar B. G., Boyer S. H., and Tsuchiya M., “Therapeutic Potential of Adenosine Kinase Inhibitors as Analgesic Agents,” Drug Development Research 50 (2000): S14–S16. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Kowaluk E. A., Bhagwat S. S., and Jarvis M. F., “Adenosine Kinase Inhibitors,” Current Pharmaceutical Design 4 (1998): 403–416. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kowaluk E. A. and Jarvis M. F., “Therapeutic Potential of Adenosine Kinase Inhibitors,” Expert Opinion on Investigational Drugs 9 (2000): 551–564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Huang W. Y., Hsu S. D., Huang H. Y., et al., “MethHC: A Database of DNA Methylation and Gene Expression in Human Cancer,” Nucleic Acids Research 43 (2015): D856–D861. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Wiesner J. B., Ugarkar B. G., Castellino A. J., et al., “Adenosine Kinase Inhibitors as a Novel Approach to Anticonvulsant Therapy,” Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 289 (1999): 1669–1677. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. McNally T., Helfrich R. J., Cowart M., et al., “Cloning and Expression of the Adenosine Kinase Gene From Rat and Human Tissues,” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 231 (1997): 645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Dragunow M., “Adenosine and Seizure Termination,” Annals of Neurology 29 (1991): 575. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. During M. J. and Spencer D. D., “Adenosine: A Potential Mediator of Seizure Arrest and Postictal Refractoriness,” Annals of Neurology 32 (1992): 618–624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Park J. and Gupta R. S., “Adenosine Kinase and Ribokinase ‑ The RK Family of Proteins,” Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences 65 (2008): 2875–2896. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Park J. and Gupta R. S., “Adenosine Metabolism, Adenosine Kinase, and Evolution,” in Adenosine: A Key Link Between Metabolism and Central Nervous System Activity, ed. Boison D. and Masino M. A. (Springer, 2013), 23–54. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bontemps F., Van den Berghe G., and Hers H. G., “Evidence for a Substrate Cycle Between AMP and Adenosine in Isolated Hepatocytes,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 80 (1983): 2829–2833. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Sen B., Chakraborty A., Datta R., Bhattacharyya D., and Datta A. K., “Reversal of ADP‐Mediated Aggregation of Adenosine Kinase by Cyclophilin Leads to Its Reactivation,” Biochemistry 45 (2006): 263–271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Kahn B. B., Alquier T., Carling D., and Hardie D. G., “AMP‐Activated Protein Kinase: Ancient Energy Gauge Provides Clues to Modern Understanding of Metabolism,” Cell Metabolism 1 (2005): 15–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Boison D., Chen J. F., and Fredholm B. B., “Adenosine Signalling and Function in Glial Cells,” Cell Death and Differentiation 17 (2010): 1071–1082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Aymerich I., Foufelle F., Ferre P., Casado F. J., and Pastor‐Anglada M., “Extracellular Adenosine Activates AMP‐Dependent Protein Kinase (AMPK),” Journal of Cell Science 119 (2006): 1612–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Merrill G. F., Kurth E. J., Hardie D. G., and Winder W. W., “AICA Riboside Increases AMP‐Activated Protein Kinase, Fatty Acid Oxidation, and Glucose Uptake in Rat Muscle,” American Journal of Physiology 273 (1997): E1107–E1112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Pyla R., Hartney T. J., and Segar L., “AICAR Promotes Endothelium‐Independent Vasorelaxation by Activating AMP‐Activated Protein Kinase via Increased ZMP and Decreased ATP/ADP Ratio in Aortic Smooth Muscle,” Journal of Basic and Clinical Physiology and Pharmacology 33 (2022): 759–768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Boison D., Scheurer L., Zumsteg V., et al., “Neonatal Hepatic Steatosis by Disruption of the Adenosine Kinase Gene,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 99 (2002): 6985–6990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Moffatt B. A., Stevens Y. Y., Allen M. S., et al., “Adenosine Kinase Deficiency Is Associated With Developmental Abnormalities and Reduced Transmethylation,” Plant Physiology 128 (2002): 812–821. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Bjursell M. K., Blom H. J., Cayuela J. A., et al., “Adenosine Kinase Deficiency Disrupts the Methionine Cycle and Causes Hypermethioninemia, Encephalopathy, and Abnormal Liver Function,” American Journal of Human Genetics 89 (2011): 507–515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Almuhsen N., Guay S. P., Lefrancois M., et al., “Clinical Utility of Methionine Restriction in Adenosine Kinase Deficiency,” JIMD Reports 61 (2021): 52–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Wahba A. E., Fedele D., Gebril H., et al., “Adenosine Kinase Expression Determines DNA Methylation in Cancer Cell Lines,” ACS Pharmacology & Translational Science 4 (2021): 680–686. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Williams‐Karnesky R. L., Sandau U. S., Lusardi T. A., et al., “Epigenetic Changes Induced by Adenosine Augmentation Therapy Prevent Epileptogenesis,” Journal of Clinical Investigation 123, no. 8 (2013): 3552–3563, 10.1172/JCI65636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Gebril H., Wahba A., Zhou X., et al., “Developmental Role of Adenosine Kinase in the Cerebellum,” eNeuro 8 (2021): ENEURO.0011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Gebril H. M., Rose R. M., Gesese R., et al., “Adenosine Kinase Inhibition Promotes Proliferation of Neural Stem Cells After Traumatic Brain Injury,” Brain Communications 2 (2020): fcaa017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Kiese K., Jablonski J., Boison D., and Kobow K., “Dynamic Regulation of the Adenosine Kinase Gene During Early Postnatal Brain Development and Maturation,” Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 9 (2016): 99, 10.3389/fnmol.2016.00099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Studer F. E., Fedele D. E., Marowsky A., et al., “Shift of Adenosine Kinase Expression From Neurons to Astrocytes During Postnatal Development Suggests Dual Functionality of the Enzyme,” Neuroscience 142 (2006): 125–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Toti K. S., Osborne D., Ciancetta A., Boison D., and Jacobson K. A., “South (S)‐ and North (N)‐Methanocarba‐7‐Deazaadenosine Analogues as Inhibitors of Human Adenosine Kinase,” Journal of Medicinal Chemistry 59 (2016): 6860–6877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Young J. D., Yao S. Y., Baldwin J. M., Cass C. E., and Baldwin S. A., “The Human Concentrative and Equilibrative Nucleoside Transporter Families, SLC28 and SLC29,” Molecular Aspects of Medicine 34 (2013): 529–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Etherington L. A., Patterson G. E., Meechan L., et al., “Astrocytic Adenosine Kinase Regulates Basal Synaptic Adenosine Levels and Seizure Activity but Not Activity‐Dependent Adenosine Release in the Hippocampus,” Neuropharmacology 56 (2009): 429–437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Fedele D. E., Gouder N., Güttinger M., et al., “Astrogliosis in Epilepsy Leads to Overexpression of Adenosine Kinase Resulting in Seizure Aggravation,” Brain 128 (2005): 2383–2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Li T., Lan J. Q., Fredholm B. B., Simon R. P., and Boison D., “Adenosine Dysfunction in Astrogliosis: Cause for Seizure Generation?,” Neuron Glia Biology 3 (2007): 353–366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Shen H. Y., Sun H., Hanthorn M. M., et al., “Overexpression of Adenosine Kinase in Cortical Astrocytes and Focal Neocortical Epilepsy in Mice,” Journal of Neurosurgery 120 (2014): 628–638. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Petruk N., Tuominen S., Akerfelt M., et al., “CD73 Facilitates EMT Progression and Promotes Lung Metastases in Triple‐Negative Breast Cancer,” Scientific Reports 11 (2021): 6035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Pignataro G., Simon R. P., and Boison D., “Transgenic Overexpression of Adenosine Kinase Aggravates Cell Death in Ischemia,” Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism 27 (2007): 1–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Fedele D. E., Koch P., Scheurer L., et al., “Engineering Embryonic Stem Cell Derived Glia for Adenosine Delivery,” Neuroscience Letters 370 (2004): 160–165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Lovatt D., Xu Q., Liu W., et al., “Neuronal Adenosine Release, and Not Astrocytic ATP Release, Mediates Feedback Inhibition of Excitatory Activity,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 109 (2012): 6265–6270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Cunha R. A., “Adenosine as a Neuromodulator and as a Homeostatic Regulator in the Nervous System: Different Roles, Different Sources and Different Receptors,” Neurochemistry International 38 (2001): 107–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Cui X. A., Singh B., Park J., and Gupta R. S., “Subcellular Localization of Adenosine Kinase in Mammalian Cells: The Long Isoform of AdK Is Localized in the Nucleus,” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 388 (2009): 46–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Masino S. A., Li T., Theofilas P., et al., “A Ketogenic Diet Suppresses Seizures in Mice Through Adenosine A1 Receptors,” Journal of Clinical Investigation 121, no. 7 (2011): 2679–2683, 10.1172/JCI57813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Boison D., “Adenosine as a Modulator of Brain Activity,” Drug News & Perspectives 20, no. 10 (2007): 607–611, 10.1358/dnp.2007.20.10.1181353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rho J. M. and Boison D., “The Metabolic Basis of Epilepsy,” Nature Reviews. Neurology 18 (2022): 333–347. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Palchykova S., Winsky‐Sommerer R., Shen H.‐Y., Boison D., Gerling A., and Tobler I., “Manipulation of Adenosine Kinase Affects Sleep Regulation in Mice,” Journal of Neuroscience 30 (2010): 13157–13165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Chen J. F., Eltzschig H. K., and Fredholm B. B., “Adenosine Receptors as Drug Targets ‑ What Are the Challenges?,” Nature Reviews. Drug Discovery 12 (2013): 265–286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Boison D. and Aronica E., “Comorbidities in Neurology: Is Adenosine the Common Link?,” Neuropharmacology 97 (2015): 18–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. McGaraughty S., Cowart M., Jarvis M. F., and Berman R. F., “Anticonvulsant and Antinociceptive Actions of Novel Adenosine Kinase Inhibitors,” Current Topics in Medicinal Chemistry 5 (2005): 43–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Boison D. and Jarvis M. F., “Adenosine Kinase: A Key Regulator of Purinergic Physiology,” Biochemical Pharmacology 187 (2021): 114321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Lado F. A. and Moshe S. L., “How Do Seizures Stop?,” Epilepsia 49 (2008): 1651–1664. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Boison D., “Adenosine Augmentation Therapies (AATs) for Epilepsy: Prospect of Cell and Gene Therapies,” Epilepsy Research 85 (2009): 131–141. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Boison D., Scheurer L., Tseng J. L., Aebischer P., and Mohler H., “Seizure Suppression in Kindled Rats by Intraventricular Grafting of an Adenosine Releasing Synthetic Polymer,” Experimental Neurology 160 (1999): 164–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Aronica E., Sandau U. S., Iyer A., and Boison D., “Glial Adenosine Kinase ‐ A Neuropathological Marker of the Epileptic Brain,” Neurochemistry International 63 (2013): 688–695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Aronica E., Zurolo E., Iyer A., et al., “Upregulation of Adenosine Kinase in Astrocytes in Experimental and Human Temporal Lobe Epilepsy,” Epilepsia 52 (2011): 1645–1655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Gouder N., Scheurer L., Fritschy J.‐M., and Boison D., “Overexpression of Adenosine Kinase in Epileptic Hippocampus Contributes to Epileptogenesis,” Journal of Neuroscience 24 (2004): 692–701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Li T., Ren G., Lusardi T., et al., “Adenosine Kinase Is a Target for the Prediction and Prevention of Epileptogenesis in Mice,” Journal of Clinical Investigation 118, no. 2 (2008): 571–582, 10.1172/JCI33737. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Kose M., Schiedel A. C., Bauer A. A., et al., “Focused Screening to Identify New Adenosine Kinase Inhibitors,” Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry 24 (2016): 5127–5133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Sandau U. S., Yahya M., Bigej R., Friedman J. L., Saleumvong B., and Boison D., “Transient Use of a Systemic Adenosine Kinase Inhibitor Attenuates Epilepsy Development in Mice,” Epilepsia 60 (2019): 615–625. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Kobow K., Kaspi A., Harikrishnan K. N., et al., “Deep Sequencing Reveals Increased DNA Methylation in Chronic Rat Epilepsy,” Acta Neuropathologica 126 (2013): 741–756. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Martins‐Ferreira R., Leal B., Chaves J., et al., “Epilepsy Progression Is Associated With Cumulative DNA Methylation Changes in Inflammatory Genes,” Progress in Neurobiology 209 (2022): 102207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Miller‐Delaney S. F., Bryan K., Das S., et al., “Differential DNA Methylation Profiles of Coding and Non‐Coding Genes Define Hippocampal Sclerosis in Human Temporal Lobe Epilepsy,” Brain 138, no. 3 (2015): 616–631, 10.1093/brain/awu373. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Mohandas N., Loke Y. J., Hopkins S., et al., “Evidence for Type‐Specific DNA Methylation Patterns in Epilepsy: A Discordant Monozygotic Twin Approach,” Epigenomics 11 (2019): 951–968. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68. Wang L., Fu X., Peng X., et al., “DNA Methylation Profiling Reveals Correlation of Differential Methylation Patterns With Gene Expression in Human Epilepsy,” Journal of Molecular Neuroscience 59 (2016): 68–77. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69. Bley C. J., Nie S., Mobbs G. W., et al., “Architecture of the Cytoplasmic Face of the Nuclear Pore,” Science 376 (2022): eabm9129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70. Fontana P., Dong Y., Pi X., et al., “Structure of Cytoplasmic Ring of Nuclear Pore Complex by Integrative Cryo‐EM and AlphaFold,” Science 376 (2022): eabm9326. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71. Jiang D., “Building the Nuclear Pore Complex,” Science 376 (2022): 1172–1173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72. Schwartz T. U., “Solving the Nuclear Pore Puzzle,” Science 376 (2022): 1158–1159. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73. Zhu X., Huang G., Zeng C., et al., “Structure of the Cytoplasmic Ring of the Xenopus laevis Nuclear Pore Complex,” Science 376 (2022): eabl8280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74. Sen B., Venugopal V., Chakraborty A., et al., “Amino Acid Residues of Leishmania Donovani Cyclophilin Key to Interaction With Its Adenosine Kinase: Biological Implications,” Biochemistry 46 (2007): 7832–7843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75. deCampo D. M. and Kossoff E. H., “Ketogenic Dietary Therapies for Epilepsy and Beyond,” Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care 22, no. 4 (2019): 264–268, 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000565. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76. Freeman J. M. and Kossoff E. H., “Ketosis and the Ketogenic Diet, 2010: Advances in Treating Epilepsy and Other Disorders,” Advances in Pediatrics 57 (2010): 315–329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77. Caraballo R., Vaccarezza M., Cersosimo R., et al., “Long‐Term Follow‐Up of the Ketogenic Diet for Refractory Epilepsy: Multicenter Argentinean Experience in 216 Pediatric Patients,” Seizure 20 (2011): 640–645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78. Schoeler N. E., Ridout D., Neal E. G., et al., “Maintenance of Response to Ketogenic Diet Therapy for Drug‐Resistant Epilepsy Post Diet Discontinuation: A Multi‐Centre Case Note Review,” Seizure 121 (2024): 78–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79. Taub K. S., Kessler S. K., and Bergqvist A. G., “Risk of Seizure Recurrence After Achieving Initial Seizure Freedom on the Ketogenic Diet,” Epilepsia 55 (2014): 579–583. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80. Lusardi T. A., Akula K. K., Coffman S. Q., Ruskin D. N., Masino S. A., and Boison D., “Ketogenic Diet Prevents Epileptogenesis and Disease Progression in Adult Mice and Rats,” Neuropharmacology 99 (2015): 500–509. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81. M. Kawamura, Jr. , Ruskin D. N., Geiger J. D., Boison D., and Masino S. A., “Ketogenic Diet Sensitizes Glucose Control of Hippocampal Excitability,” Journal of Lipid Research 55 (2014): 2254–2260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82. M. Kawamura, Jr. , Ruskin D. N., and Masino S. A., “Metabolic Autocrine Regulation of Neurons Involves Cooperation Among Pannexin Hemichannels, Adenosine Receptors, and KATP Channels,” Journal of Neuroscience 30 (2010): 3886–3895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83. Kovacs Z., D'Agostino D. P., Dobolyi A., and Ari C., “Adenosine A1 Receptor Antagonism Abolished the Anti‐Seizure Effects of Exogenous Ketone Supplementation in Wistar Albino Glaxo Rijswijk Rats,” Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience 10, no. 235 (2017): 235, 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84. Socala K., Nieoczym D., Pierog M., and Wlaz P., “Role of the Adenosine System and Glucose Restriction in the Acute Anticonvulsant Effect of Caprylic Acid in the 6 Hz Psychomotor Seizure Test in Mice,” Progress in Neuro‐Psychopharmacology & Biological Psychiatry 57 (2015): 44–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85. Fisher R., Salanova V., Witt T., et al., “Electrical Stimulation of the Anterior Nucleus of Thalamus for Treatment of Refractory Epilepsy,” Epilepsia 51 (2010): 899–908. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86. Hamani C., Andrade D., Hodaie M., Wennberg R., and Lozano A., “Deep Brain Stimulation for the Treatment of Epilepsy,” International Journal of Neural Systems 19 (2009): 213–226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87. Hodaie M., Wennberg R., Dostrovsky J., and Lozano A., “Chronic Anterior Thalamus Stimulation for Intractable Epilepsy,” Epilepsia 43 (2002): 603–608. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88. Theodore W. and Fisher R., “Brain Stimulation for Epilepsy,” Lancet Neurology 3 (2004): 111–118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89. Englot D. J., Chang E. F., and Auguste K. I., “Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Epilepsy: A Meta‐Analysis of Efficacy and Predictors of Response,” Journal of Neurosurgery 115 (2011): 1248–1255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90. Milby A. H., Halpern C. H., and Baltuch G. H., “Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Epilepsy and Depression,” Neurotherapeutics 5 (2008): 75–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91. Uthman B. M., “Vagus Nerve Stimulation for Seizures,” Archives of Medical Research 31 (2000): 300–303. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92. Bekar L., Libionka W., Tian G. F., et al., “Adenosine Is Crucial for Deep Brain Stimulation‐Mediated Attenuation of Tremor,” Nature Medicine 14 (2008): 75–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93. Boison D., “Deep Brain Stimulation in the Dish: Focus on Mechanisms,” Epilepsy Currents 14 (2014): 201–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94. Gimenes C., Motta Pollo M. L., Diaz E., Hargreaves E. L., Boison D., and Covolan L., “Deep Brain Stimulation of the Anterior Thalamus Attenuates PTZ Kindling With Concomitant Reduction of Adenosine Kinase Expression in Rats,” Brain Stimulation 15 (2022): 892–901. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95. Zhang Y., Wang X., Tang C., et al., “Genetic Variations of Adenosine Kinase as Predictable Biomarkers of Efficacy of Vagus Nerve Stimulation in Patients With Pharmacoresistant Epilepsy,” Journal of Neurosurgery 136 (2022): 726–735. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96. Diamond M. L., Ritter A. C., Jackson E. K., et al., “Genetic Variation in the Adenosine Regulatory Cycle Is Associated With Posttraumatic Epilepsy Development,” Epilepsia 56 (2015): 1198–1206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97. Cossum P. A., Sasmor H., Dellinger D., et al., “Disposition of the 14C‐Labeled Phosphorothioate Oligonucleotide ISIS 2105 After Intravenous Administration to Rats,” Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 267 (1993): 1181–1190. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98. Khorkova O. and Wahlestedt C., “Oligonucleotide Therapies for Disorders of the Nervous System,” Nature Biotechnology 35 (2017): 249–263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99. Morris G., O'Brien D., and Henshall D. C., “Opportunities and Challenges for microRNA‐Targeting Therapeutics for Epilepsy,” Trends in Pharmacological Sciences 42 (2021): 605–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100. Zhu J., Qiu W., Wei F., et al., “Reactive A1 Astrocyte‐Targeted Nucleic Acid Nanoantiepileptic Drug Downregulating Adenosine Kinase to Rescue Endogenous Antiepileptic Pathway,” ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces 15 (2023): 29876–29888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101. Antonioli L., Blandizzi C., Pacher P., and Hasko G., “Immunity, Inflammation and Cancer: A Leading Role for Adenosine,” Nature Reviews. Cancer 13 (2013): 842–857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102. Vijayan D., Young A., Teng M. W. L., and Smyth M. J., “Targeting Immunosuppressive Adenosine in Cancer,” Nature Reviews. Cancer 17 (2017): 765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103. Yegutkin G. G. and Boison D., “ATP and Adenosine Metabolism in Cancer: Exploitation for Therapeutic Gain,” Pharmacological Reviews 74 (2022): 797–822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104. Ohta A., “A Metabolic Immune Checkpoint: Adenosine in Tumor Microenvironment,” Frontiers in Immunology 7, no. 109 (2016): 109, 10.3389/fimmu.2016.00109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105. Allard B., Turcotte M., and Stagg J., “Targeting CD73 and Downstream Adenosine Receptor Signaling in Triple‐Negative Breast Cancer,” Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets 18 (2014): 863–881. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106. Eltzschig H. K., Sitkovsky M. V., and Robson S. C., “Purinergic Signaling During Inflammation,” New England Journal of Medicine 367 (2012): 2322–2333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107. Ohta A., Gorelik E., Prasad S. J., et al., “A2A Adenosine Receptor Protects Tumors From Antitumor T Cells,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 103 (2006): 13132–13137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108. Beavis P. A., Stagg J., Darcy P. K., and Smyth M. J., “CD73: A Potent Suppressor of Antitumor Immune Responses,” Trends in Immunology 33 (2012): 231–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109. Thompson E. A. and Powell J. D., “Inhibition of the Adenosine Pathway to Potentiate Cancer Immunotherapy: Potential for Combinatorial Approaches,” Annual Review of Medicine 72 (2021): 331–348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110. Barlesi F., Cho B. C., Goldberg S. B., et al., “PACIFIC‐9: Phase III Trial of Durvalumab + Oleclumab or Monalizumab in Unresectable Stage III Non‐Small‐Cell Lung Cancer,” Future Oncology 20 (2024): 2137–2147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111. Bendell J., LoRusso P., Overman M., et al., “First‐In‐Human Study of Oleclumab, a Potent, Selective Anti‐CD73 Monoclonal Antibody, Alone or in Combination With Durvalumab in Patients With Advanced Solid Tumors,” Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 72 (2023): 2443–2458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112. Buisseret L., Loirat D., Aftimos P., et al., “Paclitaxel Plus Carboplatin and Durvalumab With or Without Oleclumab for Women With Previously Untreated Locally Advanced or Metastatic Triple‐Negative Breast Cancer: The Randomized SYNERGY Phase I/II Trial,” Nature Communications 14 (2023): 7018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113. Coveler A. L., Reilley M. J., Zalupski M., et al., “A Phase Ib/II Randomized Clinical Trial of Oleclumab With or Without Durvalumab Plus Chemotherapy in Patients With Metastatic Pancreatic Ductal Adenocarcinoma,” Clinical Cancer Research 30 (2024): 4609–4617. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114. Falchook G. S., Reeves J., Gandhi S., et al., “A Phase 2 Study of AZD4635 in Combination With Durvalumab or Oleclumab in Patients With Metastatic Castration‐Resistant Prostate Cancer,” Cancer Immunology, Immunotherapy 73 (2024): 72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115. Herbst R. S., Majem M., Barlesi F., et al., “COAST: An Open‐Label, Phase II, Multidrug Platform Study of Durvalumab Alone or in Combination With Oleclumab or Monalizumab in Patients With Unresectable, Stage III Non‐Small‐Cell Lung Cancer,” Journal of Clinical Oncology 40 (2022): 3383–3393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116. Kim D. W., Kim S. W., Camidge D. R., et al., “CD73 Inhibitor Oleclumab Plus Osimertinib in Previously Treated Patients With Advanced T790M‐Negative EGFR‐Mutated NSCLC: A Brief Report,” Journal of Thoracic Oncology 18 (2023): 650–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117. Kondo S., Iwasa S., Koyama T., et al., “Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Antitumour Activity of Oleclumab in Japanese Patients With Advanced Solid Malignancies: A Phase I, Open‐Label Study,” International Journal of Clinical Oncology 27 (2022): 1795–1804. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118. Mirza M. R., Tandaric L., Henriksen J. R., et al., “NSGO‐OV‐UMB1/ENGOT‐OV30: A Phase II Study of Durvalumab in Combination With the Anti‐CD73 Monoclonal Antibody Oleclumab in Patients With Relapsed Ovarian Cancer,” Gynecologic Oncology 188 (2024): 103–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119. Segal N. H., Tie J., Kopetz S., et al., “COLUMBIA‐1: A Randomised Study of Durvalumab Plus Oleclumab in Combination With Chemotherapy and Bevacizumab in Metastatic Microsatellite‐Stable Colorectal Cancer,” British Journal of Cancer 131 (2024): 1005–1013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120. Shamloo B., Kumar N., Owen R. H., et al., “Dysregulation of Adenosine Kinase Isoforms in Breast Cancer,” Oncotarget 10 (2019): 7238–7250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121. Zhulai G., Oleinik E., Shibaev M., and Ignatev K., “Adenosine‐Metabolizing Enzymes, Adenosine Kinase and Adenosine Deaminase, in Cancer,” Biomolecules 12 (2022): 418. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122. Cheu J. W.‐S., Chiu D. K.‐C., Kwan K. K.‐L., et al., “Hypoxia‐Inducible Factor Orchestrates Adenosine Metabolism to Promote Liver Cancer Development,” Science Advances 9 (2023): eade5111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123. Nagaya H., Gotoh A., Kanno T., and Nishizaki T., “A3 Adenosine Receptor Mediates Apoptosis in In Vitro RCC4‐VHL Human Renal Cancer Cells by Up‐Regulating AMID Expression,” Journal of Urology 189 (2013): 321–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124. Soleimani A., Bahreyni A., Roshan M. K., et al., “Therapeutic Potency of Pharmacological Adenosine Receptors Agonist/Antagonist on Cancer Cell Apoptosis in Tumor Microenvironment, Current Status, and Perspectives,” Journal of Cellular Physiology 234 (2019): 2329–2336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125. Yu S., Hou D., Chen P., et al., “Adenosine Induces Apoptosis Through TNFR1/RIPK1/P38 Axis in Colon Cancer Cells,” Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 460 (2015): 759–765. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126. Hashemi M., Karami‐Tehrani F., Ghavami S., Maddika S., and Los M., “Adenosine and Deoxyadenosine Induces Apoptosis in Oestrogen Receptor‐Positive and ‐Negative Human Breast Cancer Cells via the Intrinsic Pathway,” Cell Proliferation 38 (2005): 269–285. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127. Tsuchiya A., Kanno T., Saito M., et al., “Intracellularly Transported Adenosine Induces Apoptosis in [Corrected] MCF‐7 Human Breast Cancer Cells by Accumulating AMID in the Nucleus,” Cancer Letters 321 (2012): 65–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128. Xu Y., Wang Y., Yan S., et al., “Regulation of Endothelial Intracellular Adenosine via Adenosine Kinase Epigenetically Modulates Vascular Inflammation,” Nature Communications 8 (2017): 943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129. Xu Y., Wang Y., Yan S., et al., “Intracellular Adenosine Regulates Epigenetic Programming in Endothelial Cells to Promote Angiogenesis,” EMBO Molecular Medicine 9 (2017): 1263–1278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130. Casciello F., Windloch K., Gannon F., and Lee J. S., “Functional Role of G9a Histone Methyltransferase in Cancer,” Frontiers in Immunology 6 (2015): 487, 10.3389/fimmu.2015.00487. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131. Du J., Johnson L. M., Jacobsen S. E., and Patel D. J., “DNA Methylation Pathways and Their Crosstalk With Histone Methylation,” Nature Reviews. Molecular Cell Biology 16 (2015): 519–532. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132. Gokul G. and Khosla S., “DNA Methylation and Cancer,” Sub‐Cellular Biochemistry 61 (2013): 597–625. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133. Jin B. and Robertson K. D., “DNA Methyltransferases, DNA Damage Repair, and Cancer,” Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology 754 (2013): 3–29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134. Mentch S. J. and Locasale J. W., “One‐Carbon Metabolism and Epigenetics: Understanding the Specificity,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1363 (2016): 91–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135. Zahnow C. A., Topper M., Stone M., et al., “Inhibitors of DNA Methylation, Histone Deacetylation, and Histone Demethylation: A Perfect Combination for Cancer Therapy,” Advances in Cancer Research 130 (2016): 55–111, 10.1016/bs.acr.2016.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136. Colotta F., Allavena P., Sica A., Garlanda C., and Mantovani A., “Cancer‐Related Inflammation, the Seventh Hallmark of Cancer: Links to Genetic Instability,” Carcinogenesis 30 (2009): 1073–1081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137. Zhang M., Zeng X., Yang Q., et al., “Ablation of Myeloid ADK (Adenosine Kinase) Epigenetically Suppresses Atherosclerosis in ApoE(−/−) (Apolipoprotein E Deficient) Mice,” Arteriosclerosis, Thrombosis, and Vascular Biology 38 (2018): 2780–2792. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138. Cao W., Wan H., Wu L., et al., “Adenosine Kinase Inhibition Attenuates Ischemia Reperfusion‐Induced Acute Kidney Injury,” Life Sciences 256 (2020): 117972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139. Elsherbiny N. M., Ahmad S., Naime M., et al., “ABT‐702, an Adenosine Kinase Inhibitor, Attenuates Inflammation in Diabetic Retinopathy,” Life Sciences 93 (2013): 78–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140. Pye C., Elsherbiny N. M., Ibrahim A. S., et al., “Adenosine Kinase Inhibition Protects the Kidney Against Streptozotocin‐Induced Diabetes Through Anti‐Inflammatory and Anti‐Oxidant Mechanisms,” Pharmacological Research 85 (2014): 45–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141. Xu J., Liu Z., Yang Q., et al., “Adenosine Kinase Inhibition Protects Mice From Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm via Epigenetic Modulation of VSMC Inflammation,” Cardiovascular Research 120 (2024): 1202–1217. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]