Abstract

Urinary tract infection (UTI) is one of the most common infections worldwide, increasing the incidence of antibiotic resistance and creating demand for alternative antimicrobial agents. Propolis, a natural antimicrobial agent, has been used in ancient folk medicine. This study evaluates the effectiveness of ethanolic extract of propolis (EEP) alone and in combination with honey against multidrug-resistant (MDR) uropathogens and also investigates the chemical composition of Egyptian propolis, which may be a potential therapeutic approach against MDR uropathogens. EEP was prepared, followed by column chromatographic fractionation using four different solvent systems. The ethyl acetate fraction was further fractionated through vacuum liquid chromatography (VLC). The antimicrobial activity of the EEP, propolis fractions, honey, and EEP-Honey mixture was studied, and the fraction with the best antimicrobial activity was analyzed by GC-MS and HPLC. The results indicated that EEP showed antimicrobial activity against the five MDR uropathogens with varying potential, while honey showed no activity against these pathogens. In comparison, the EEP-Honey mixture exhibited good antimicrobial synergy, with the MIC value decreasing by approximately 4–8 folds. In propolis fractionation, ethyl acetate was the best solvent for extracting antimicrobial substances from EEP, and fraction 5 (F5) was the most active fraction, with inhibition zone diameters of 30.33, 29.00, 21.58, 25.33, and 27.67 mm against MDR P. aeruginosa, E. coli, K. pneumoniae, S. saprophyticus, and C. albicans, respectively. GC-MS analysis of the F5 fraction revealed the presence of phenolics, flavonoids, terpenoids, acids, and alkaloids. In addition, HPLC polyphenol analysis identified 14 phenolic acids and flavonoid compounds with concentrations ranging from 117.36 to 5657.66 µg/g. Overall, the current findings highlighted the promising antimicrobial synergy of the EEP-Honey mixture against MDR urinary pathogens. The phytochemical analysis of propolis also identified potential bioactive compounds responsible for its biological and pharmaceutical properties.

Keywords: Uropathogens, Propolis, Antimicrobial activity, EEP, Ethanolic extract of propolis, Active fraction, GC-MS, HPLC

Subject terms: Antimicrobials, Microbiology techniques, Chromatography

Introduction

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are among the most well-known community and hospital-associated microbial infections, affecting more than 150 million people annually worldwide1,2. They are among the most frequent complications in critical care patients2,3. Generally, antibiotics are prescribed as empiric therapy even as the result of urine culture, and this approach has probably contributed to the increase in antibiotic resistance worldwide4. Thus, the improper use of antibiotics may delay effective treatment and participate in the emergence of multidrug-resistant (MDR) microbes5,6. The World Health Organization (WHO) and other researchers have emphasized the urgent need for novel antimicrobial approaches to combat infectious diseases7–9.

Propolis, or bee glue, is a naturally occurring sticky material that belongs to the family of bee products9,10. The word “propolis” originates from two ancient Greek words: pro- means “in front of” or “at the entrance,” and polis means “city” or “community,” collectively referring to a substance used to defend the hive10,11. Propolis is collected by worker bees from the resinous secretions of a variety of plant species, such as pine, poplar, alder, conifer, beech, and birch, and then mixed with enzymatic and salivary bee secretions to form bee glue12,13.

Propolis has been used in folk medicine since ~ 300 BC and is reported to have several biological activities, including antibacterial, fungicidal9,14, antiviral, immunomodulator15,16, anti-inflammatory17, antioxidant17,18, and antitumor19. Furthermore, a previous study has demonstrated the good effect of propolis in increasing the growth rate of some types of probiotic bacteria20.

Indeed, the raw propolis consists of 45 to 55% plant resin, 25 to 35% beeswax, 5 to 10% aromatic and essential oil, 5% pollen, and 5% other natural constituents21. Propolis also contains various sorts of secondary plant metabolites, such as phenolic acids, tannins, terpenoids, alkaloids, and flavonoids, which are responsible for several bioactivities and differ in concentrations depending on the season, plant sources, and geographical origins9,22,23. It has many targeted sites with strong activity, attributed to its phenolic constituents, so it can potentially increase the effectiveness of other antimicrobial agents and act synergistically24. The current study aimed to investigate the antimicrobial activity of the crude ethanolic extract of propolis (EEP), its synergistic effects when combined with honey, and the chemical composition of propolis responsible for its antimicrobial properties.

Materials and methods

Preparation of propolis extract, honey, and their mixture

A raw Egyptian propolis sample was obtained from the Abd El-Raheam apiary located in Marsa Matrouh, Egypt, and stored in a sterile glass container in the refrigerator, away from sunlight, until extraction. It was extracted with 70% ethanol (1:10, w/v), according to Helmy et al.9. The sample was incubated under agitation for seven days at 37 °C, protected from light, followed by centrifugation for 10 min. The supernatant was dried at 40 °C until ethanol evaporation occurred to obtain the pure propolis extract in powder form. This powder was weighed and dissolved in 1% DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich) to obtain EEP at a concentration of 100 mg/ml.

An Egyptian Citrus honey sample was obtained from the Egyptian Ministry of Agriculture, Giza, Egypt, and stored in a sterile glass container at room temperature. It was prepared in a 50% (v/v) concentration by adding an equal volume of honey to an equal volume of sterile distilled water in a sterile test tube. The honey solution was mixed by stirring with a vortex.

A mixture of EEP and honey (EEP-Honey) was prepared (1:1 v/v) to get a mixture of the final concentration (100 mg EEP/ 50% honey) to study the antimicrobial synergism between propolis and honey.

Tested uropathogens

Five MDR uropathogens were used in the current study, including one yeast isolate: fluconazole-resistant Candida albicans, one strain of Gram-positive bacteria: oxacillin and mecillinam-resistant Coagulase Negative (CON) Staphylococcus saprophyticus, and 3 Gram-negative MDR bacteria included extended-spectrum beta-lactamases (ESBL) Klebsiella pneumoniae, as well as MDR E. coli and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which resisted to ceftazidime, cefepime, aztreonam, ciprofloxacin, piperacillin, imipenem, and gentamicin.

All urinary pathogens were provided by the Clinical Microbiology Laboratory of Cleopatra Hospital, Cairo, Egypt, from urine and catheter specimens whose patients were suffering from UTIs. These pathogens were identified according to the VITEK 2 system. VITEK 2 (bioMérieux) is an automated, highly accurate microbial identification system based on phenotypic identification methods. This system accommodates colorimetric reagent cards that are automatically incubated and interpreted. Four reagent cards are used for the identification of different microorganisms: (GN) for Gram–negative bacteria; (GP) for Gram–positive cocci and non-spore-forming bacilli; (BCL) for Gram–positive spore-forming bacilli; and (YST) for yeasts and yeast-like microorganisms. Each reagent card contains 64 wells, each containing an individual test substrate for measuring different metabolic activities25.

Antimicrobial activity of EEP, Propolis fractions, and honey

Agar well diffusion method

Antimicrobial activities of EEP, propolis fractions, honey, and DMSO were determined by the agar well diffusion method on Mueller-Hinton agar (Oxoid, UK) for bacteria and on 2% glucose-supplemented Mueller-Hinton agar for Candida spp26. This test was carried out in the Biotechnology Lab, Faculty of Science, Al-Azhar University for Girls, Cairo, Egypt, according to the National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards27.

Each uropathogen was freshly prepared and cultured on nutrient agar at 35–37 °C overnight. An inoculum of 1.5 × 108 CFU/ml (equivalent to 0.5 McFarland) was prepared in sterile saline (0.85%) and swabbed over the surface of the prepared Mueller-Hinton agar plate. EEP and propolis fractions were prepared at a 100 mg/ml concentration. Wells were prepared in each plate using a sterile cork borer with a diameter of 8 mm and a volume of 100 µl of EEP, propolis fractions, honey (50% v/v), and DMSO (negative control) were dropped in each well. Also, cefotaxime (CTX 30), ciprofloxacin (CIP 5), and fluconazole 25 µg discs were used as positive controls, the zone of inhibition was measured, and results were interpreted according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute28. The plates were placed in the refrigerator for 1–2 h to allow the extracts to diffuse into the medium9. Then, the plates were incubated at 35–37 °C for 18–24 h, and the inhibition zone diameters (IZDs) were measured in mm. The experiment was performed in duplicate, and the mean ± standard error (SE) of the results was calculated.

Minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC) determination

The MIC value of EEP was evaluated using the broth microdilution method in the Regional Center for Mycology and Biotechnology, Cairo, Egypt, according to Helmy et al.9 study. At 96 well microtiter plates (BioTek, Winooski, VT, USA), an inoculum of each uropathogen suspension (1.5 × 108 CFU/ml) was incubated with broth containing different concentrations of EEP (0.12–125 mg/ml) for 24 h at 37 °C. The MIC value was estimated by visual and spectroscopic methods by absorbance measurement at 620 nm. Control tubes without uropathogen (negative controls) and without EEP (positive controls) were used. The experiment was performed in duplicate, and the MIC ± standard error (SE) of the results was calculated.

Antimicrobial synergism of the EEP-Honey mixture

Antimicrobial synergy testing of the EEP-Honey mixture against MDR uropathogens was performed using the agar well diffusion method and MIC determination, as previously described in the above sections. However, in determining the MIC, different concentrations of the EEP-Honey mixture were prepared (1:1 v/v) below the MIC value of EEP, and these mixtures were screened against MDR uropathogens as described above. The synergism was defined when the MIC value of the EEP-Honey mixture reduced the MIC value of EEP alone29, as all urinary pathogens were resistant to honey.

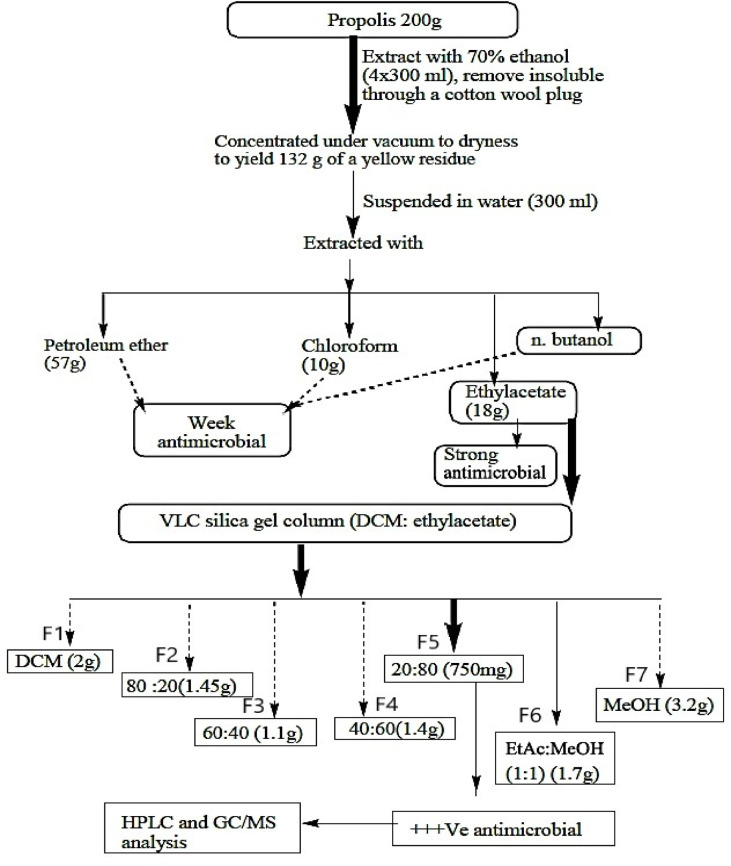

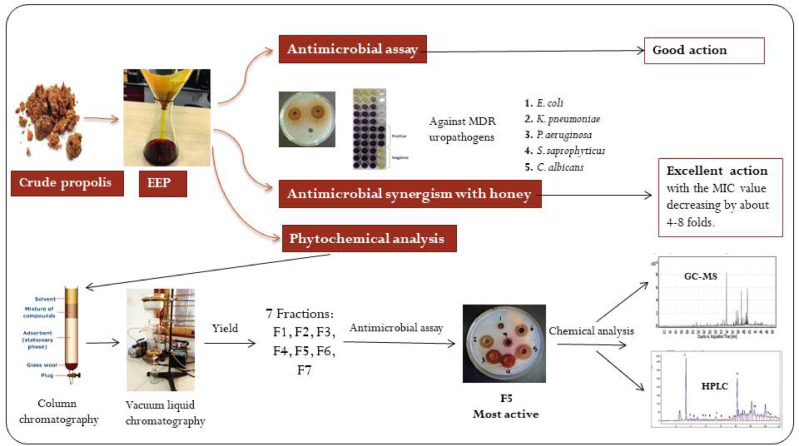

Phytochemical analysis of propolis extract

Phytochemical analysis of propolis was performed at the Faculty of Pharmacy at Al-Azhar University for boys in Cairo, Egypt, according to Afsar et al.30, with some modifications, Fig. 1. About 200 g of propolis was extracted with 70% ethanol to obtain EEP. The dried EEP was re-suspended in 300 ml of water and subjected to successive liquid-liquid extraction using petroleum ether, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and n-butanol solvent systems, and their antimicrobial activities were studied. The ethyl acetate fraction (the highest in the antimicrobial activity) was subjected to further fractionation through vacuum liquid chromatography (VLC) on silica gel column and eluted with dichloromethane (DCM), dichloromethane (DCM): ethyl acetate (80:20, 60:40, 40:60, and 20:80 v/v), ethyl acetate (EtAc): methanol (MeOH) (1:1), and methanol (MeOH) to afford seven fractions in powder form, named (F1-F7) Fig. 1. The antimicrobial activity of the seven purified fractions was studied against MDR uropathogens, and the fraction with the highest antimicrobial activity was analyzed by gas-chromatography mass-spectrometry (GC-MS) and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC).

Fig. 1.

Propolis fractionation and purification of the most active antimicrobial substance. VLC: vacuum liquid chromatography, DCM: dichloromethane, EtAc: ethyl acetate, MeOH: methanol, GC-MS: gas chromatography-mass spectrometry, HPLC: high-performance liquid chromatography, +++ ve: strong positive activity, F1- F7: fraction 1- fraction 7.

Characterization of the most active propolis fraction

The most active fraction (F5) with the highest antimicrobial activity was analyzed by GC-MS and HPLC polyphenol analysis to predict the empirical chemical structure, molecular formula, and nomenclature of the most active compounds.

GC-MS analysis of propolis active fraction (F5)

The GC-MS system (Agilent Technologies) was equipped with a gas chromatograph (7890B) and mass spectrometer detector (5977 A) at Central Laboratories Network, National Research Centre; Cairo, Egypt. The active propolis fraction (F5) derivatizations were carried out using trimethylsilyl (TMS) derivatization and based on the optimized protocol described by Villas-Bôas et al.31. In summary, dried samples were re-suspended in 20 µL of pyridine and 100 µL of N-Methyl-N-(trimethylsilyl) trifluoroacetamide (MSTFA) and incubated in a dry block heater at 70 °C for 60 min. The GC was equipped with an HP-5MS column (30 m x 0.25 mm internal diameter and 0.25 µm film thickness). Analyses were carried out using helium as the carrier gas at a flow rate of 1.0 ml/min at a splitless injection volume of 2 µl and the following temperature program: 50 °C for 10 min; rising at 8 °C/min to 300 °C and held for 10 min. The injector and detector were held at 280 °C and 220 °C, respectively. Mass spectra were obtained by electron ionization (EI) at 70 eV using a spectral range of 50–550 m/z and a solvent delay of 10 min. The mass temperature was 230 °C and Quad 150 °C. Identification of different constituents was determined by comparing the spectrum fragmentation pattern with those stored in Wiley and NIST Mass Spectral Library data.

HPLC analysis of propolis active fraction (F5)

HPLC polyphenol analysis of the most active fraction was carried out using an Agilent 1260 series. The separation was carried out using a Kromasil C18 column (4.6 mm x 250 mm i.d., 5 μm). The mobile phase consisted of water (A) and 0.05% trifluoroacetic acid in acetonitrile (B) at a flow rate of 1 ml/min. The mobile phase was programmed consecutively in a linear gradient as follows: 0 min (82% A); 0–5 min (80% A); 5–8 min (60% A); 8–12 min (60% A); 12–15 min (85% A) and 15–16 min (82% A). The injection volume was 10 µl for each of the sample solutions (15 mg/ml). The column temperature was maintained at 35 °C. Polyphenol compounds were assayed by external standard calibration at 280 nm. HPLC analysis was carried out in the Central Laboratories Network, National Research Centre, Cairo, Egypt32.

Data analysis

Data were presented as mean, and standard error (SE) was determined. Data were normally distributed, and statistical analysis was performed using ANOVA one-way LSD tests. The software package CoStat for Windows version 6.45 was used for data analysis. A P value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant for all analyses.

Results

Antimicrobial activity of EEP and its synergistic action with honey

In this study, the antimicrobial activity of EEP and its synergistic action with honey was determined by recording their IZDs and MIC values on MDR uropathogens. DMSO (negative control) was considered an inert solvent and didn’t report any inhibitory action on all MDR uropathogens. Also, cefotaxime (CTX 30), ciprofloxacin (CIP 5), and fluconazole 25-µg discs were used as positive controls and didn’t report inhibitory action on all MDR uropathogens since IZD less than 12 mm —for most antibiotics— was considered as resistant according to the Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute breakpoints. Honey has not recorded any antimicrobial action, while EEP showed an inhibitory effect with variable action on all MDR uropathogens. Indeed, EEP showed higher activity against C. albicans and S. saprophyticus with IZDs of 21.67 and 21.33 mm and MIC values of 3.51 and 3.90 mg/ml, respectively, followed by P. aeruginosa, K. pneumonia, and E. coli with IZDs of 15.00, 13.83, and 12.58 mm, respectively, and MIC value ranged between 14.66 and 31.25 mg/ml; as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Antimicrobial activity of positive and negative controls, EEP, honey, and EEP-Honey mixture against MDR uropathogens.

| pathogen | Mean IZD (mm) ± SE | MIC (mg/ml) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CTX 30 | CIP 5 | Flu 25 | DMSO | EEP (100 mg/ml) |

Honey (50%) |

EEP + Honey | EEP | EEP + Honey | |

| E. coli | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 8.00 ± 0.58 | NA | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 12.85c, B ± 0.67 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 16.58c, A ± 0.17 | 31.25a, A ± 1.52 | 7.81c, B ± 0.64 |

| K. pneumoniae | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 9.33 ± 0.67 | NA | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 13.83bc, B ± 0.44 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 20.67b, A ± 0.58 | 15.63b, A ± 0.87 | 3.9c, B ± 0.51 |

| P. aeruginosa | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | NA | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 15.00b, B ± 0.58 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 21.33b, A ± 0.33 | 14.66b, A ± 0.45 | 1.95bc, B ± 0.19 |

| S. saprophyticus | 7.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | NA | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 21.33a, B ± 0.58 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 25.67a, A ± 0.33 | 3.90c, A ± 0.37 | 0.98b, B ± 0.21 |

| C. albicans | NA | NA | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 21.67a, B ± 0.33 | 0.00 ± 0.00 | 26.00a, A ± 0.67 | 3.51c, A ± 0.72 | 0.95b, B ± 0.48 |

SE = Standard error, CTX 30: Cefotaxime, CIP 5: Ciprofloxacin, Flu 25: Fluconazole, NA: Not applicable.

Different small letters indicate significant differences within the same column (p-value < 0.05).

Different capital letters indicate significant differences (p-value < 0.05) between columns in the same test.

A p-value < 0.05 was set as representing statistical significance for all analyses.

When propolis was mixed with honey, the mixture (EEP-Honey) showed a significant increase in its IZD in the range of 16.58–26.00 mm and a decrease in its MIC values compared to EEP alone against MDR uropathogens, as a good synergistic action was recorded. The results of the synergistic effect in Table 1 indicated that MDR Gram-negative uropathogens showed a decrease in their MIC value from 14.66 to 31.25 mg/ml in EEP to 1.95–7.81 mg/ml in the EEP-Honey mixture. Moreover, MDR S. saprophyticus and fluconazole-resistant C. albicans showed a decrease in the MIC values from 3.90 to 3.51 mg/ml in EEP to 0.98 and 0.95 mg/ml in the EEP-Honey mixture, respectively, when treated with (EEP-Honey) mixture.

The p-values indicated that the EEP-Honey treatment option had a significantly greater antimicrobial effect than EEP alone across all tested pathogens. Thus, the statistical analysis suggests that honey enhances the antimicrobial properties of EEP, making EEP + Honey mixture a more effective treatment option.

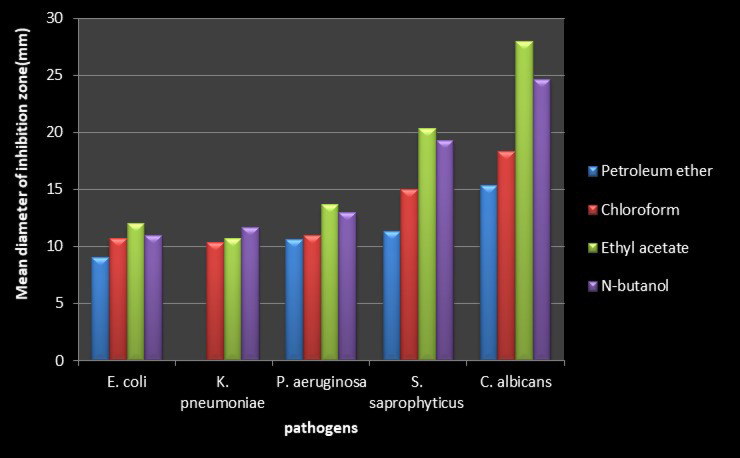

Antimicrobial activity of the extracted substances from EEP using different solvent systems

The data in Table 2; Fig. 2 indicated that, among all four solvent systems (petroleum ether, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and n-butanol), ethyl acetate was the best solvent for extracting the antimicrobial substance from EEP against MDR uropathogens (p-value < 0.05), except for K. pneumonia, followed by n-butanol, as it gave higher activity on this pathogen.

Table 2.

Effect of different solvent systems on the antimicrobial activity of EEP against MDR uropathogens.

| pathogen | Mean diameter of inhibition zone(mm) ± SE | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Petroleum ether | Chloroform | Ethyl acetate | N-butanol | |

| E. coli | 9.00c ± 0.67 | 10.67b ± 0.67 | 12.00a ± 0.00 | 11.00ab ± 0.00 |

| K. pneumoniae | 0.00c ± 0.00 | 10.33b ± 0.58 | 10.88ab ± 0.33 | 11.67a ± 0.67 |

| P. aeruginosa | 10.58b ± 0.17 | 11.00b ± 0.17 | 13.67a ± 0.67 | 13.00a ± 0.10 |

| S. saprophyticus | 11.33c ± 0.33 | 15.00b ± 0.00 | 20.33a ± 0.88 | 19.33a ± 0.58 |

| C. albicans | 15.33d ± 0.67 | 18.33c ± 0.33 | 28.00a ± 0.58 | 24.67b ± 0.33 |

Different small letters indicate significant differences (p-value < 0.05) between columns in the same test, representing the effect of the different solvent systems on the antimicrobial activity of EEP against each uropathogen. A p-value < 0.05 was set as representing statistical significance for all analyses.

Fig. 2.

Effect of different solvent systems on antimicrobial activity of EEP against MDR uropathogens.

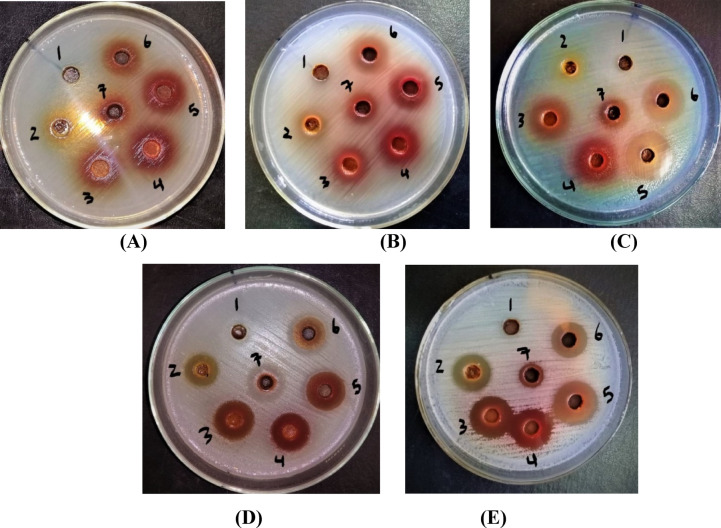

Antimicrobial activity of the fractions produced from VLC of Ethyl acetate EEP fraction

Using a VLC silica gel column, the ethyl acetate EEP fraction was separated into seven further fractions named F1, F2, F3, F4, F5, F6, and F7. Results in Table 3 and Plate 1 declared that the antimicrobial activity of the seven fractions was ordered as follows: F5 > F6 > F4 > F3 > F7 > F2 > F1. Fraction 5 (F5) that was eluted with dichloromethane (DCM): ethyl acetate (20:80) was the most active and gave significant antimicrobial activity among other fractions, with IZD of 30.33, 29.00, 27.67, 25.33, and 21.58 mm against the MDR P. aeruginosa, E. coli, C. albicans, S. saprophyticus, and K. pneumoniae, respectively. The p-values indicated Fraction 5 (F5) had a significantly greater antimicrobial effect than other fractions across all tested pathogens.

Table 3.

Antimicrobial activity of the fractions produced from VLC of ethyl acetate EEP fraction against MDR uropathogens.

| Propolis Fractions | pathogens | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli | K. pneumoniae | P. aeruginosa | S. saprophyticus | C. albicans | |

| Mean diameter of inhibition zone(mm) ± SE | |||||

| F1 | 10.33f ± 0.33 | 0.00e ± 0.00 | 0.00e ± 0.00 | 10.58d ± 0.17 | 11.00e ± 0.58 |

| F2 | 12.00e ± 0.58 | 12.00d ± 0.00 | 13.33d ± 0.33 | 20.33b ± 0.67 | 20.00c ± 0.00 |

| F3 | 14.67cd ± 0.33 | 13.33cd ± 0.33 | 15.00c ± 0.00 | 24.00a ± 0.00 | 23.67b ± 0.67 |

| F4 | 15.33c ± 0.67 | 14.00c ± 0.33 | 15.33c ± 0.33 | 22.00b ± 0.58 | 23.00b ± 0.00 |

| F5 | 29.00a ± 0.00 | 21.58a ± 1.17 | 30.33a ± 0.33 | 25.33a ± 0.67 | 27.67a ± 0.33 |

| F6 | 27.33b ± 0.33 | 18.00b ± 0.67 | 24.00b ± 0.00 | 20.67b ± 0.33 | 21.33c ± 0.58 |

| F7 | 14.00d ± 0.00 | 13.00cd ± 0.10 | 15.33c ± 0.33 | 13.58c ± 0.17 | 14.67d ± 0.33 |

Different small letters indicate significant differences within the same column (p-value < 0.05). A p-value < 0.05 was set as representing statistical significance for all analyses.

Plate 1.

Plate’s photos reveal the antimicrobial activity of the fractions produced from VLC of ethyl acetate EEP fraction on MDR (A): E. coli, (B): K. pneumonia, (C): P. aeruginosa, (D): CON S. saprophyticus, and (E): C. albicans. Numbers from 1 to 7 indicated fraction numbers.

Characterization and identification of the most active Propolis fraction

Fraction 5 (F5) was the most active fraction and gave significant antimicrobial activity among other fractions and was consequently subjected to (GC-MS) and (HPLC) polyphenol analysis.

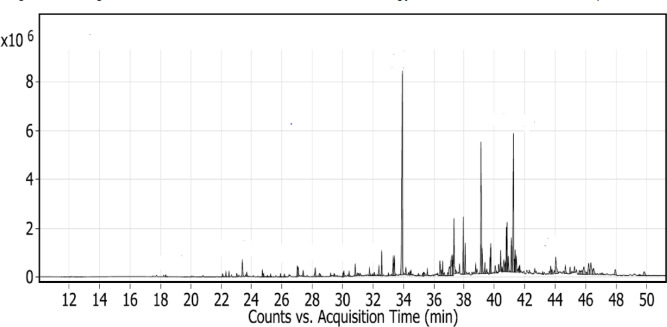

GC-MS analysis

The GC-MS analysis of the most active fraction allowed the detection of ninety compounds in different concentrations (99.1%), including phenolics, flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, and organic acids, as shown in Table 4; Fig. 3. The major compounds present in the most active fraction of the propolis (F5) were identified as caffeic acid dimethyl ether (14.63%, compound 33, RT 33.925), monopalmitoylglycerol (9.79%, compound 54, RT 38.76), and 1,6-dihydroxy-8-methoxy-3-methylanthraquinone (9.12%, compound 69, RT 41.244), which contributed to the biological activity of propolis.

Table 4.

Results of GC/MS analysis of the most active fraction of propolis.

| Compound No. | Retention Time (RT) | compound | Formula | Area Sum % |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 18.338 | Butoxyethanol | C6H14O2 | 0.16 |

| 2 | 22.092 | Silanol | SiH4O | 0.24 |

| 3 | 22.309 | Cyclohexanediol | C6H12O2 | 0.27 |

| 4 | 22.515 | Trans-cyclohexanediol | C6H12O2 | 0.24 |

| 5 | 23.025 | Benzeneacetic acid | C8H8O2 | 0.28 |

| 6 | 23.391 | Acetin | C5H10O4 | 1.37 |

| 7 | 24.713 | Disiloxane, 1,3-bis(1,1 dimethylethyl) | C12H30OSi2 | 0.38 |

| 8 | 24.793 | Resorcinol | C6H6O2 | 0.22 |

| 9 | 25.05 | Butoxyacetate | C10H20O3 | 0.15 |

| 10 | 25.256 | 2-Aminoisobutyric acid | H2N-C(CH3)2-COOH | 0.18 |

| 11 | 25.909 | Oxyvaleric acid | CH3(CH2)3COOH | 0.2 |

| 12 | 26.155 | Kojic acid | C6H6O4 | 0.2 |

| 13 | 27.013 | Cinnamic acid | C9H8O2 | 0.72 |

| 14 | 27.076 | Pyrogallol | C6H6O3 | 0.59 |

| 15 | 27.396 | Tyrosol | C8H10O2 | 0.32 |

| 16 | 28.192 | -4-Hydroxybenzoic acid | C7H6O3 | 0.56 |

| 17 | 28.472 | Dodecenoic acid | C12H22O2 | 0.28 |

| 18 | 29.204 | Dimethoxybenzene | C8H10O2 | 0.18 |

| 19 | 29.433 | 10-Undecynoic acid | C11H18O2 | 0.15 |

| 20 | 30.017 | Phloretic acid | C9H10O3 | 0.22 |

| 21 | 30.074 | 4-Methox benzoic acid | C8H8O3 | 0.41 |

| 22 | 30.417 | Azelaic acid | C9H16O4 | 0.33 |

| 23 | 30.824 | Protocatechoic acid | C7H6O4 | 0.7 |

| 24 | 30.95 | p-methoxy Cinnamic acid | C10H10O3 | 0.19 |

| 25 | 31.07 | Falcarinol | C17H24O | 0.2 |

| 26 | 31.762 | 2,4-Dihydroxyacetophenone | C8H8O3 | 0.47 |

| 27 | 32.077 | Hydroxydihydrosafrole | C10H12O3 | 0.25 |

| 28 | 32.386 | Caffeic acid | C9H8O4 | 0.65 |

| 29 | 32.569 | Gallic acid | C7H6O5 | 1.16 |

| 30 | 33.015 | Ninhydrin | C9H6O4 | 0.16 |

| 31 | 33.324 | Dimethyl caffeic acid | C11H12O4 | 1.4 |

| 32 | 33.404 | Palmitic Acid | C16H32O2 | 1.29 |

| 33 | 33.925 | Caffeic acid dimethyl ether | C11H12O5 | 14.63 |

| 34 | 34.16 | beta.-Cholestane-alpha.,7.alpha.,12.alpha.,24.alpha.,25-pentol | C27H44O5 | 0.37 |

| 35 | 34.429 | Benzothiophene-3-carbonitrile, 4,5,6,7-tetrahydro-2-(4-tert-butylbenzylidenamino | C9H10O2S | 0.18 |

| 36 | 34.492 | 1,3-Bis(pentamethyldisilanyloxy)propane | C17H20O6S2 | 0.31 |

| 37 | 34.989 | Beta- Eudesmol | C15H26O | 0.17 |

| 38 | 35.316 | 13-Octadecenoic acid | C18H34O2 | 0.23 |

| 39 | 35.35 | alpha.-D-Glucopyranoside | C7H14O6 | 0.29 |

| 40 | 35.573 | Stearic acid | C17H35CO2H | 0.37 |

| 41 | 36.408 | Heneicosanoic acid | C21H42O2 | 1.06 |

| 42 | 36.494 | 5-dimethyl-6,8-dioxooctahydro-1 H-1,4-methanoinden-1-yl)propanoate | C13H22O2 | 0.42 |

| 43 | 36.586 | − (3a,5-dimethyl-6,8-dioxooctahydro-1 H-1,4-methanoinden-1-yl)propanoate | C16H30O2 | 0.75 |

| 44 | 36.689 | Vanillic acid | C8H8O4 | 0.29 |

| 45 | 36.918 | 1-ethyl-2-benzimidazolyl (2-methoxyphenyl) | C11H14O3 | 0.2 |

| 46 | 37.021 | 9-Octadecenamide | C18H35NO | 1.14 |

| 47 | 37.158 | Urocanic Acid | C6H6N2O2 | 2.42 |

| 48 | 37.244 | Silane, diethyl(3-methylbutoxy)octadecyloxy | C5H11Cl3Si | 1.31 |

| 49 | 37.33 | t-Butyldimethyl(10-octylundec-10-enyloxy) silane | C25H52OSi | 3.63 |

| 50 | 37.45 | 15-Isopropenyl-oxacyclopentadecan-2-one | C20H38O2Si | 0.24 |

| 51 | 37.696 | Hexakis(fluorodimethylsilyl)benzebe | C18H36F6Si6 | 0.5 |

| 52 | 37.942 | 1,4-benzenediacetonitrile, .alpha.,.alpha.‘-bis[[4-(diethylamino)-2-methoxyphenyl]methylene | C34H38N4O2 | 3.22 |

| 53 | 38.068 | Linoleic acid (LA) | C18H32O2 | 1.65 |

| 54 | 38.76 | Monopalmitoylglycerol | C19H38O4 | 9.79 |

| 55 | 39.184 | 3,7,11,15-tetramethylhexadecan-1,3-diol | C20H42O2 | 1.51 |

| 56 | 39.361 | Erythro-Pentonic acid, 2-deoxy-3,4,5-tris-OH | C17H42O5 | 0.65 |

| 57 | 39.487 | 1-Monoferuloylglycerol | C13H16O6 | 0.26 |

| 58 | 39.75 | 5,8,11-Eicosatriynoic acid | C20H28O2 | 2.43 |

| 59 | 40.048 | Tofisopam | C22H26N2O4 | 0.7 |

| 60 | 40.271 | Arachidonic acid | C20H24O2 | 0.48 |

| 61 | 40.397 | Silane, diethyloctyloxytetradecyloxy | C26H56O2Si | 1.02 |

| 62 | 40.494 | 2-Monostearin | C21H42O4 | 0.23 |

| 63 | 40.614 | 1-Monooleoylglycerol | C21H40O4 | 1.07 |

| 64 | 40.706 | Genistein | C15H10O5 | 0.55 |

| 65 | 40.774 | Catechine | C15H14O6 | 2.33 |

| 66 | 40.826 | Glycerol monostearate | C21H42O4 | 2.63 |

| 67 | 40.917 | D-Glucopyranuronic acid | C6H10O7 | 0.99 |

| 68 | 41.106 | [(2-{3,4-Bisoxy]phenyl}- oxy]-3,4-dihydro-2 H-chromen-7-yl-oxysilane | C30H54O6Si5 | 1.74 |

| 69 | 41.244 | 1,6-Dihydroxy-8-methoxy-3-methylanthraquinone | C16H12O5 | 9.12 |

| 70 | 41.318 | (4-(1-(3,5-Dimethyl-4phenyl)-1,3-dimethylbutyl)-2,6-dimethylphenoxysilane | C28H46O2Si2 | 0.6 |

| 71 | 41.358 | [(2-{3,4-Bisoxy]phenyl}-3,5-bis-3,4-dihydro-2 H-chromen-7-yl)oxy](trimethyl)silane | C30H54O6Si5 | 1.21 |

| 72 | 41.427 | 17.alpha.-Methyltestosterone | C20H30O2 | 1.14 |

| 73 | 41.621 | 4-Androsten-4-ol-3,17-dionel | C19H26O3 | 0.32 |

| 74 | 41.661 | Monoketal adduct | C29H32O5 | 0.39 |

| 75 | 42.296 | Saponarin | C27H30O15 | 0.24 |

| 76 | 43.172 | 3,5-Dihydroxybenzyl alcohol | C7H8O3 | 0.15 |

| 77 | 43.698 | delta.(1)-Tetrahydrocannabinolic acid | C22H30O4 | 0.54 |

| 78 | 43.784 |

17-(1,5-Dimethylhexyl)-10,13-dimethyl-3-styrylhexadecahydrocyclopenta[a] phenanthren-2-one |

C35H52O | 0.43 |

| 79 | 44.036 | -unknown | 1.91 | |

| 80 | 44.665 | 1,2,8-Trihydroxy-3-methoxy-6-methylanthraquinone | C16H12O6 | 0.66 |

| 81 | 44.974 | Monoolein | C21H40O4 | 0.48 |

| 82 | 45.592 | Homogentisic acid | C8H8O4 | 0.4 |

| 83 | 45.712 | 2,4-Imidazolidinedione, 5- oxy]phenyl]-3-methyl-5-phenyl | C16H16N2O4 | 0.54 |

| 84 | 45.884 | Naringenin | C15H12O5 | 1.48 |

| 85 | 46.205 | 2-Oxabicyclo[3.3.0]octa-3,7-dien-6-one, 3-acetyl-4-methyl-1,5,7,8-tetrakis | C22H42O7 | 2.99 |

| 86 | 46.519 | 6-[Nonadecenyl]salicylic acid | C26H42O3 | 0.89 |

| 87 | 47.074 | Octasiloxane, hexadecamethyl | C16H50O7 | 0.27 |

| 88 | 47.944 | 2-Monomyristin | C17H34O4 | 0.65 |

| 89 | 49.552 | Heptasiloxane, tetradecamethyl ester | C14H42O7Si7 | 0.16 |

| 90 | 49.855 | 1-Monolinoleoylglycerol | C27H54O4 | 0.65 |

| Total | 99.1 |

Fig. 3.

GC/MS analysis of the most active fraction of propolis.

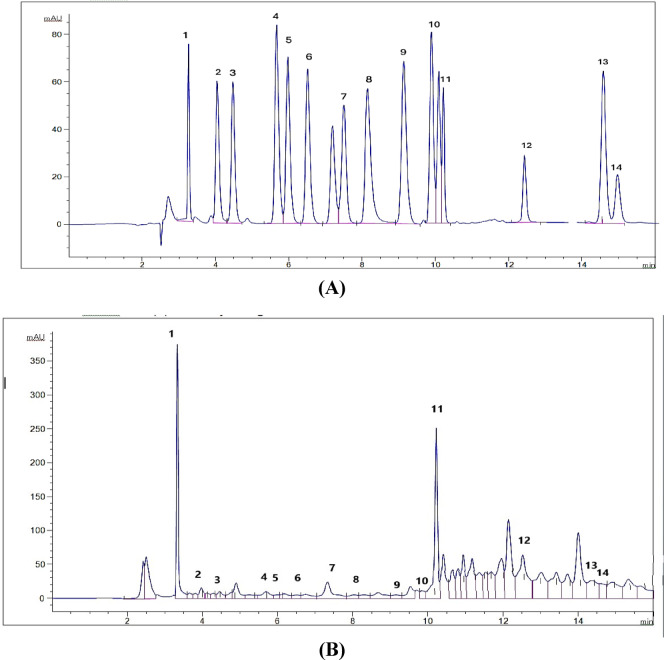

HPLC analysis

HPLC polyphenol analysis of the most active fraction (F5) in propolis revealed the presence of 14 phenolic acids and flavonoid compounds in the range of 117.36–5657.66 µg/g. These compounds included 4 flavonoids (catechin, naringenin, taxifolin, and kaempferol) and 10 phenolic acids (gallic acid, chlorogenic acid, catechin, methyl gallate, caffeic acid, syringic acid, pyrocatechol, ellagic acid, coumaric acid, vanillin, and cinnamic acid). The biological activity of the propolis fraction contributed to the most abundant compounds, which included naringenin (5657.66 µg/g), gallic acid (5217.66 µg/g), taxifolin (5192.48 µg/g), pyrocatechol (2182.90 µg/g), and kaempferol (1029.27 µg/g), as shown in Table 5; Fig. 4.

Table 5.

Results of HPLC analysis of fraction 5.

| Peak No. | Retention time (RT) | Concentration (µg/g) | Identified compounds | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | Test | |||

| 1. | 3.263 | 3.334 | 5217.66 | Gallic acid |

| 2. | 4.046 | 3.970 | 594.05 | Chlorogenic acid |

| 3. | 4.475 | 4.460 | 1183.75 | Catechin |

| 4. | 5.668 | 5.694 | 194.71 | Methyl gallate |

| 5. | 5.974 | 5.993 | 121.32 | Coffeic acid |

| 6. | 6.513 | 6.504 | 153.70 | Syringic acid |

| 7. | 7.193 | 7.328 | 2182.90 | Pyrocatechol |

| 8. | 8.147 | 8.301 | 336.62 | Ellagic acid |

| 9. | 9.139 | 9.149 | 117.36 | Coumaric acid |

| 10. | 9.894 | 9.848 | 154.83 | Vanillin |

| 11. | 10.218 | 10.223 | 5657.66 | Naringenin |

| 12. | 13.431 | 13.019 | 5192.48 | Taxifolin |

| 13. | 14.332 | 14.590 | 322.58 | Cinnamic acid |

| 14. | 14.715 | 14.907 | 1029.27 | Kaempferol |

Fig. 4.

HPLC chromatogram of (A) reference standards polyphenol compounds and (B) fraction 5 in propolis with identified marker compounds. 1: gallic acid, 2: chlorogenic acid, 3: catechin, 4: methyl gallate, 5: coffeic acid, 6: syringic acid, 7: pyrocatechol, 8: ellagic acid, 9: coumaric acid, 10: vanillin, 11: naringenin, 12: taxifolin, 13: cinnamic acid, and 14: kaempferol.

Discussion

Propolis (bee glue) is as old as honey and has been used by humans as a traditional medicine since antiquity. There are many records recommending its utilization in medication by the ancient Egyptians, Persians, and Romans33. The results of the in vitro antimicrobial assay indicated that EEP inhibited the growth of Gram-positive CON S. saprophyticus bacteria and Candida albicans yeast better than Gram-negative P. aeruginosa, K. pneumonia, and E. coli bacteria. This is explained by the presence of the outer membrane in the Gram-negative bacteria14,34. The low sensitivity of E. coli toward propolis has also been reported by many researchers, as this bacterium showed either very low sensitivity or a total lack of sensitivity to propolis35,36. Moreover, a previous study by Taher37 supported our results and reported that MDR K. pneumoniae was sensitive to Iraq EEP with an average inhibition zone of 12.6 mm at a concentration of 100 mg/ml, while another study by Al-Ani et al.22 found P. aeruginosa displayed high resistance to European propolis, which is in contrast to our results. In the current study, the MIC value of EEP on C. albicans and S. saprophyticus was 3.51 and 3.90 mg/ml, respectively, while against P. aeruginosa, K. pneumonia, and E. coli were in the range of 14.66–31.25 mg/ml, which were higher than a previous study of ours on Turkish propolis that reported MIC values in the range of 0.185-3.50 mg/ml on K. pneumonia, P. aeruginosa, S. aureus, and C. albicans9. On the other hand, previous studies have concluded that natural honey can inhibit the growth of some pathogenic bacteria with varying inhibition degrees9,38,39, while honey in our study showed no effect on the isolated pathogens, which may be due to the extreme resistance of urinary pathogens to antibiotics.

The addition of propolis to honey resulted in an increase in IZDs of EEP from 12.85 to 21.67 mm to 16.58–26.00 mm in the EEP-Honey mixture as well as a decrease in the MIC values of EEP from 3.51 to 31.25 mg/ml to 0.95–7.81 mg/ml in the EEP-Honey mixture, where significant synergy has been recorded. Basically, the antimicrobial synergism of propolis and honey may be related to the synergistic effect of their various flavonoids and phenolic compounds, which have been supported by previous studies24,29,40. In line with our findings, another study by Hamouda et al.41 reported the good antimicrobial effect of Egyptian fennel honey and EEP against 19 strains of methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA), where honey and EEP showed a synergistic effect when added together (MIC = 7.84 mg/ml).

Propolis fractionation was performed using a three-step sequential extraction: first with 70% ethanol, followed by the use of four solvent systems (petroleum ether, chloroform, ethyl acetate, and n-butanol), where ethyl acetate was the best solvent for the extraction of the antimicrobial substance from EEP. These results were supported by the study of Bouaroura et al.42 using Algerian propolis, as the ethyl acetate extract displayed increased contents of antimicrobial substances. Further, findings in the Chen et al.43 study reported the ethyl acetate fraction showed the highest total phenolic and flavonoid contents, which have potential antioxidant and antimicrobial activity, compared to the n-butanol fraction, chloroform fraction, and petroleum ether fractions. The standard protocols for chemical fractionation and bioactivity-guided chemical analysis were used to identify the bioactive ethyl acetate fraction, as it contained the highest polyphenol contents44. The third step was carried out using a VLC silica gel column, as the ethyl acetate EEP fraction was separated into seven further fractions named F1, F2, F3, F4, F5, F6, and F7, on which the pure F5 fraction gave the best antimicrobial activity against MDR uropathogens and was subsequently analyzed by GC-MS and HPLC.

The GC-MS analysis of the F5 fraction revealed the presence of 90 chemical compounds at different concentrations, including phenolic acids, flavonoids, terpenoids, alkaloids, steroids, organic acids, fatty acids, hydrocarbon esters, ketones, and sugars. These compounds act synergistically and are responsible for the therapeutical and pharmacological properties of propolis12,45. Polyphenol compounds (phenolic acids and flavonoids) are considered the main antimicrobial and bioactive antioxidant components in propolis9,46. In our study, caffeic acid esters are strong bactericidal agents and inhibit bacterial growth by disrupting membrane permeability or through oxidative stress mechanisms47,48. Also, 1,6-Dihydroxy-8-methoxy-3-methylanthraquinone and monopalmitoylglycerol were reported in propolis in Kurek-Górecka et al.48 and Shi et al.49. studies with anti-inflammatory properties. Further, 4-hydroxycinnamic acid is a derivative of cinnamic acid and disrupts the outer membrane of Gram-negative bacteria, causing cytoplasmic leakage50.

The HPLC analysis of the most active propolis fraction (F5) resulted in the presence of 14 polyphenol compounds, including naringenin, gallic acid, taxifolin, pyrocatechol, kaempferol, catechin, chlorogenic acid, methyl gallate, coffeic acid, syringic acid, ellagic acid, coumaric acid, vanillin, and cinnamic acid, which contributed to the antimicrobial activities of propolis. Previous studies on African, Asian, and European propolis concluded that propolis contains predominantly polyphenols such as naringenin, galangin, pinocembrin, apigenin, pinobanksin, quercetin, cinnamic acid and its esters, aromatic acids and their esters, kaempferol, chrysin, p-coumaric acid, cinnamyl caffeate, cinnamylidene acetic acid, and caffeic acid46,51,52. The composition of propolis varies depending on the plant’s origin, geographical location, and collection seasons9,22.

The high concentration of naringenin and taxifolin flavonoids in our study may be the main reason for the significant inhibitory effect of F5 fraction against MDR uropathogens, especially P. aeruginosa (IZD = 30.33 mm), where Vandeputte et al.53 and Shariati et al.54 studies reported the inhibitory effect of naringenin and taxifolin on the expression of various quorum sensing (QS) controlled genes in P. aeruginosa and thus reduce the virulence factors of pathogenic bacteria. Furthermore, naringenin possesses anti-staphylococcal activity55,56 and antibacterial properties against E. coli56. Likewise, some phenolic acids, such as cinnamic acid and its derivatives, have anti-QS activity and inhibit bacteria by damaging the cell membrane, inhibiting ATPases, cell division, and biofilm formation57. Also, other phenolic acids like ferulic, caffeic, and chlorogenic acids are effective in preventing bacterial adhesion58,59; while gallic acid inhibits efflux pump mechanisms in MDR Staphylococcus spp. and E. coli strains. The mixture of phenolic catechin and vanillic acids possesses antioxidant and antimicrobial synergy and is effective in preventing cell adhesion and biofilm formation in uropathogenic E. coli compared to single compounds or nitrofurantoin antibiotics60. Accordingly, the combination of many active components in propolis and their presence in various proportions prevents the occurrence of bacterial resistance48,61,62. Finally, the design of the study and the important findings were presented as a schematic drawing in Fig. 5.

Fig. 5.

A Schematic drawing illustrating the design of the study and the important findings.

Conclusion

Over recent years, the increasing empiric treatment with antibiotics in UTIs and the emergence of MDR urinary pathogens have stimulated the use of traditional medicine and attempts to improve it for therapeutic use, such as propolis, honey, and their mixtures. In the current study, propolis inhibited all MDR uropathogens, while honey did not. Interestingly, the combination of propolis and honey showed a great synergistic effect with a significant increase in the antimicrobial activity of propolis, which was expressed by reducing the MIC value of EEP for all uropathogens by approximately 4–8 folds. Propolis fractionation was carried out, as ethyl acetate was the best solvent to extract the antimicrobial substances from EEP. The ethyl acetate EEP fraction was further fractionated using a VLC silica gel column to get seven fractions, of which the F5 fraction was the most active with the best antimicrobial activity against MDR uropathogens and was analyzed by GC-MS and HPLC. HPLC analysis of the polyphenols in the F5 fraction of propolis revealed the presence of 14 phenolic acids and flavonoid compounds, where the most abundant compounds were naringenin, gallic acid, taxifolin, and pyrocatechol. GC-MS analysis indicated the presence of many constituents in different concentrations, including phenolic acids, flavonoids, terpenoids, and alkaloids, which are responsible for the biological and pharmaceutical properties of propolis. Thus, the combination of many active ingredients in propolis and their presence in various proportions prevents bacterial resistance.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to express their deep and sincere gratitude to Dr. Heba Sayed Mostafa, Associate Professor of Food Science, Faculty of Agriculture, Cairo University, Egypt, for her assistance in the statistical analysis process that supported the significance of the observed differences in the results.

Abbreviations

- CON

Coagulase negative

- EEP

Ethanolic extract of propolis

- ESBL

Extended spectrum β-lactam antibiotic

- F1

F7:Fraction 1:fraction 7

- GC-MS

Gas chromatography-mass spectrometry

- HPLC

High-performance liquid chromatography

- IZD

Inhibition zone diameter

- MDR

Multidrug-resistant

- MIC

Minimum inhibitory concentration

- MRSA

Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus

- RT

Retention time

- SE

Standard error

- UTI

Urinary tract infection

- VLC

Vacuum liquid chromatography

Author contributions

NMS, MMA, and AAE developed and supervised the work. AKH, NMS, MMA, and AAE designed the study. MMA performed the MIC test. AAE performed the phytochemical analysis of propolis. AKH collected the uropathogens, performed the antimicrobial and synergy experimental work, analyzed and interpreted the data, and wrote the first draft of the manuscript. NMS reviewed and editing the initial and final drafts of the manuscript. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

Open access funding provided by The Science, Technology & Innovation Funding Authority (STDF) in cooperation with The Egyptian Knowledge Bank (EKB).

Data availability

All information created or analyzed during the present study are included in the manuscript.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable. This manuscript does not refer to or imply the use of any animal or human data or tissues.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.McLellan, L. K. & Hunstad, D. A. Urinary tract infection: pathogenesis and outlook. Trends Mol. Med.22 (11), 946–957. 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.09.003 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Mlugu, E. M., Mohamedi, J. A., Sangeda, R. Z. & Mwambete, K. D. Prevalence of urinary tract infection and antimicrobial resistance patterns of uropathogens with biofilm forming capacity among outpatients in Morogoro, Tanzania: a cross-sectional study. BMC Infect. Dis.23 (1), 660. 10.1186/s12879-023-08641-x (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Galiczewski, J. M. & Shurpin, K. M. An intervention to improve the catheter associated urinary tract infection rate in a medical intensive care unit: direct observation of catheter insertion procedure. Intensive Crit. Care Nurs.40, 26–34. 10.1016/j.iccn.2016.12.003 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Waller, T. A., Pantin, S. A., Yenior, A. L. & Pujalte, G. G. Urinary tract infection antibiotic resistance in the united States. Prim. Care: Clin. Office Pract.45 (3), 455–466. 10.1016/j.pop.2018.05.005 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li, W. et al. Rapid identification and antimicrobial susceptibility testing for urinary tract pathogens by direct analysis of urine samples using a MALDI-TOF MS-based combined protocol. Front. Microbiol.10, 458039. 10.3389/fmicb.2019.01182 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Helmy, A. K., Sidkey, N. M., El-Badawy, R. E. & Hegazi, A. G. Emergence of microbial infections in some hospitals of Cairo, Egypt: studying their corresponding antimicrobial resistance profiles. BMC Infect. Dis.23 (1), 424. 10.1186/s12879-023-08397-4 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization (WHO). Antibacterial Agents in Clinical Development: an Analysis of the Antibacterial Clinical Development Pipeline, Including Tuberculosis (World Health Organization, 2017). https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/258965WHO/EMP/IAU/2017.12.

- 8.D’Andrea, M. M., Fraziano, M., Thaller, M. C. & Rossolini, G. M. The urgent need for novel antimicrobial agents and strategies to fight antibiotic resistance. Antibiotics8 (4), 254. 10.3390/antibiotics8040254 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Helmy, A. K., Hegazi, A. G. & Sidkey, N. M. Antimicrobial activity of some honeybee products on Multidrug-Resistant secondary microbial infection from COVID-19 patients. Egypt J. Hosp. Med.92 (1). 10.21608/EJHM.2023.313899 (2023).

- 10.Bankova, V. Chemical diversity of propolis and the problem of standardization. J. Ethnopharmacol.100 (1–2), 114–117. 10.1016/j.jep.2005.05.004 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tosic, S., Stojanovic, G., Mitic, S., Pavlovic, A. & Alagic, S. Mineral composition of selected Serbian propolis samples. J. Apic. Sci.61 (1), 5–15. 10.1515/jas-2017-0001 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anjum, S. I. et al. Composition and functional properties of propolis (bee glue): A review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci.26 (7), 1695–1703. 10.1016/j.sjbs.2018.08.013 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Irigoiti, Y. et al. The use of propolis as a functional food ingredient: A review. Trends Food Sci. Technol.115, 297–306. 10.1016/j.tifs.2021.06.041 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sa-Eed, A. et al. In vitro antimicrobial activity of crude propolis extracts and fractions. FEMS Microbes. 410.1093/femsmc/xtad010 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Yosri, N. et al. Anti-viral and Immunomodulatory properties of propolis: chemical diversity, Pharmacological properties, preclinical and clinical applications, and in Silico potential against SARS-CoV-2. Foods10 (8), 1776. 10.3390/foods10081776 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Negri, G. et al. Antiviral activity of red propolis against herpes simplex virus-1. Brazilian J. Pharm. Sci.60, e23746. 10.1590/s2175-97902024e23746 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Abduh, M. Y., Shafitri, T. R. & Elfahmi, E. Chemical profiling, bioactive compounds, antioxidant, and anti-inflammatory activities of Indonesian propolis extract produced by Tetragonula laeviceps. Heliyon10 (19). 10.1016/j.heliyon.2024.e38736 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 18.Nichitoi, M. M. et al. Polyphenolics profile effects upon the antioxidant and antimicrobial activity of propolis extracts. Sci. Rep.11 (1), 20113. 10.1038/s41598-021-97130-9 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Shaker, S. A. et al. Propolis-loaded nanostructured lipid carriers halt breast cancer progression through miRNA-223 related pathways: an in-vitro/in-vivo experiment. Sci. Rep.13 (1), 15752. 10.1038/s41598-023-42709-7 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Saddiq, A. A. & Danial, E. N. Effect of Propolis as a food additive on the growth rate of the beneficial bacteria. Main Group Chem.13 (3), 223–332. 10.3233/MGC-140135 (2014). [Google Scholar]

- 21.Santos-Buelga, C. & González-Paramás, A. M. Bee products-chemical and biological properties. Chemical Composition of Honey. Springer 43–82 https://link.springer.com/book/10.1007/978-3-319-59689-1 (2017).

- 22.Al-Ani, I., Zimmermann, S., Reichling, J. & Wink, M. Antimicrobial activities of European propolis collected from various geographic origins alone and in combination with antibiotics. Medicines5 (1), 2. 10.3390/medicines5010002 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.El Menyiy, N., Bakour, M., El Ghouizi, A., El Guendouz, S. & Lyoussi, B. Influence of geographic origin and plant source on physicochemical properties, mineral content, and antioxidant and antibacterial activities of Moroccan Propolis. Int. J. Food Sci.2021 (1), 5570224. 10.1155/2021/5570224 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Salatino, A. Perspectives for uses of propolis in therapy against infectious diseases. Molecules27 (14), 4594. 10.3390/molecules27144594 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pincus, D. H. Microbial identification using the bioMérieux Vitek® 2 system. Encyclopedia of Rapid Microbiological Methods. Bethesda, MD: Parenteral Drug Association. 1–32 https://store.pda.org/tableofcontents/ermm_v2_ch01.pdf (2006).

- 26.Barry, A. et al. Quality control limits for fluconazole disk susceptibility tests on Mueller-Hinton agar with glucose and methylene blue. J. Clin. Microbiol.41 (7), 3410–3412. 10.1128/jcm.41.7.3410-3412.2003 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.National Committee for Clinical Laboratory Standards (NCCLS). Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests of bacteria that Grow Aerobically: Approved Standard M100-S12 (NCCLS, 2002).

- 28.Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute. Performance standards for antimicrobial susceptibility testing. 30th ed. CLSI supplement M100. Wayne, PA: CLSI. Available from: https://www.nih.org.pk/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/CLSI-2020.pdf (2020).

- 29.Noori, A. L., Al-Ghamdi, A., Ansari, M. J., Al-Attal, Y. & Salom, K. Synergistic effects of honey and propolis toward drug multi-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, Escherichia coli and Candida albicans isolates in single and polymicrobial cultures. Int. J. Med. Sci.9 (9), 793. 10.7150/ijms.4722 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Afsar, T. et al. Bioassay-guided isolation and characterization of lead antimicrobial compounds from Acacia Hydaspica plant extract. AMB Express. 12 (1), 156. 10.1186/s13568-022-01501-y (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Villas-Bôas, S. G., Noel, S., Lane, G. A., Attwood, G. & Cookson, A. Extracellular metabolomics: a metabolic footprinting approach to assess fiber degradation in complex media. Anal. Biochem.349 (2), 297–305. 10.1016/j.ab.2005.11.019 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Abdel-Aziz, A. W., Elwan, N. M., Shaaban, R. S., Osman, N. S. & Mohamed, M. A. HighPerformance liquid chromatographyfingerprint analyses, in vitro cytotoxicity, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of the extracts of Ceiba speciosa growing in Egypt. Egypt. J. Chem.64 (4), 1831–1843. 10.21608/ejchem.2021.58716.3267 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kuropatnicki, A. K., Szliszka, E. & Krol, W. Historical aspects of propolis research in modern times. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med.2013 (1), 964149. 10.1155/2013/964149 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Alegun, O., Pandeya, A., Cui, J., Ojo, I. & Wei, Y. Donnan potential across the outer membrane of gram-negative bacteria and its effect on the permeability of antibiotics. Antibiotics10 (6), 701. 10.3390/antibiotics10060701 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kujumgiev, A. et al. Antibacterial, antifungal and antiviral activity of propolis of different geographic origin. J. Ethnopharmacol.64 (3), 235–240. 10.1016/s0378-8741(98)00131-7 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gonzalez, B. E. et al. Severe Staphylococcal sepsis in adolescents in the era of community-acquired methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Pediatrics115 (3), 642–648. 10.1542/peds.2004-2300 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Taher, N. M. Synergistic effect of Propolis extract and antibiotics on Multi-Resist Klebsiella Pneumoniae strain isolated Fom wound. Adv. Life Sci. Technol.43. https://core.ac.uk/reader/234687340 (2016).

- 38.Johnston, M., McBride, M., Dahiya, D., Owusu-Apenten, R. & Nigam, P. S. Antibacterial activity of Manuka honey and its components: an overview. AIMS Microbiol.4 (4), 655. 10.3934/microbiol.2018.4.655 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Prudence, I. A., Celestin, M. P., Hiberte, M., Josue, I. & Eric, S. The effect of honey on Bacteria isolated from urinary tract infections among patients attending ruhengeri referral hospital. J. Drug Delivery Ther.14 (4), 10–13. 10.22270/jddt.v14i4.6104 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Vică, M. L. et al. Antibacterial activity of propolis extracts from the central region of Romania against neisseria gonorrhoeae. Antibiotics10 (6), 689. 10.3390/antibiotics10060689 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hamouda, S. M., Abd El Rahman, M. F., Abdul-Hafeez, M. M. & Gerges, A. E. Egyptian fennel honey and/or propolis against MRSA harboring both MecA & IcaA genes. Int. J. Complement. Altern. Med.11, 180–185. 10.15406/ijcam.2018.11.00392 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bouaroura, A. et al. Phytochemical investigation of phenolic constituents and in vitro evaluation of antioxidant activity of five Algerian Propolis. Curr. Bioact. Compd.17 (8), 79–87. 10.2174/1573407216999201231200041 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Chen, X., He, X., Sun, J. & Wang, Z. Phytochemical composition, antioxidant activity, α-glucosidase and acetylcholinesterase inhibitory activity of Quinoa extract and its fractions. Molecules27 (8), 2420. 10.3390/molecules27082420 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Elnakady, Y. A. et al. Characteristics, chemical compositions and biological activities of propolis from Al-Bahah, Saudi Arabia. Sci. Rep.7 (1), 41453. 10.1038/srep41453 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Mouhoubi-Tafinine, Z., Ouchemoukh, S. & Tamendjari, A. Antioxydant activity of some Algerian honey and propolis. Ind. Crops Prod.88, 85–90. 10.1016/j.indcrop.2016.02.033 (2016). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nada, A. A. et al. Synergistic effect of potential alpha-amylase inhibitors from Egyptian propolis with acarbose using in Silico and in vitro combination analysis. BMC Complement. Med. Ther.24 (1), 65. 10.1186/s12906-024-04348-x (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Collins, W., Lowen, N. & Blake, D. J. Caffeic acid esters are effective bactericidal compounds against Paenibacillus larvae by altering intracellular oxidant and antioxidant levels. Biomolecules9 (8), 312. 10.3390/biom9080312 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Kurek-Górecka, A. et al. Comparison of the antioxidant activity of propolis samples from different geographical regions. Plants11 (9), 1203. 10.3390/plants11091203 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Shi, H. et al. Isolation and characterization of five glycerol esters from Wuhan propolis and their potential anti-inflammatory properties. J. Agric. Food Chem.60 (40), 10041–10047. 10.1021/jf302601m (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Guzman, J. D. Natural cinnamic acids, synthetic derivatives and hybrids with antimicrobial activity. Molecules19 (12), 19292–19349. 10.3390/molecules191219292 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Huang, S., Zhang, C. P., Wang, K., Li, G. Q. & Hu, F. L. Recent advances in the chemical composition of propolis. Molecules19 (12), 19610–19632. 10.3390/molecules191219610 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Machado, C. S., Finger, D., Caetano, I. K. & Torres, Y. R. Multivariate GC-MS data analysis of the apolar fraction of brown propolis produced in Southern Brazil. J. Apic. Res.14, 1–2. 10.1080/00218839.2023.2212487 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vandeputte, O. M. et al. The Flavanone naringenin reduces the production of quorum sensing-controlled virulence factors in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PAO1. Microbiology157 (7), 2120–2132. 10.1099/mic.0.049338-0 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Shariati, A. et al. Inhibitory effect of natural compounds on quorum sensing system in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a helpful promise for managing biofilm community. Front. Pharmacology.15, 1350391 10.3389/fphar.2024.1350391 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 55.do Nascimento, T. G. et al. Comprehensive multivariate correlations between climatic effect, metabolite-profile, antioxidant capacity and antibacterial activity of Brazilian red propolis metabolites during seasonal study. Sci. Rep.9 (1), 18293 10.1038/s41598-019-54591-3 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Dantas, D. M. et al. Naringenin as potentiator of Norfloxacin efficacy through Inhibition of the NorA efflux pump in Staphylococcus aureus. Microb. Pathog.10750410.1016/j.micpath.2025.107504 (2025). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 57.Vasconcelos, N. G., Croda, J. & Simionatto, S. Antibacterial mechanisms of cinnamon and its constituents: A review. Microb. Pathog.120, 198–203. 10.1016/j.micpath.2018.04.036 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Borges, A., Saavedra, M. J. & Simões, M. The activity of ferulic and Gallic acids in biofilm prevention and control of pathogenic bacteria. Biofouling28 (7), 755–767. 10.1080/08927014.2012.706751 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gupta, P., Song, B., Neto, C. & Camesano, T. A. Atomic force microscopy-guided fractionation reveals the influence of cranberry phytochemicals on adhesion of Escherichia coli. Food Funct.7 (6), 2655–2666. 10.1039/C6FO00109B (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Bernal-Mercado, A. T. et al. Comparison of single and combined use of Catechin, Protocatechuic, and vanillic acids as antioxidant and antibacterial agents against uropathogenic Escherichia coli at planktonic and biofilm levels. Molecules23 (11), 2813. 10.3390/molecules23112813 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Pamplona-Zomenhan, L. C., Pamplona, B. C., Silva, C. B., Marcucci, M. C. & Mimica, L. M. Evaluation of the in vitro antimicrobial activity of an ethanol extract of Brazilian classified propolis on strains of Staphylococcus aureus. Brazilian J. Microbiol.42, 1259–1264. 10.1590/S1517-83822011000400002 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.De Rossi, L., Rocchetti, G., Lucini, L., & Rebecchi, A. Antimicrobial potential of polyphenols: mechanisms of action and microbial responses-a narrative review. Antioxidants14 (2), 200 10.3390/antiox14020200 (2025). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All information created or analyzed during the present study are included in the manuscript.