Abstract

Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis (EDKA) is a type of DKA whose incidence has increased in recent years because of the widespread use of sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors in diabetes treatment. However, the concomitant occurrence of a thyroid storm is uncommon, easily misdiagnosed and missed, and has a high risk of death. This report described the case of a 46-year-old woman with type 2 diabetes mellitus who used a sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitor to manage her blood glucose levels. Before undergoing hysteroscopic surgery for a uterine mass, she developed EDKA and thyroid storm after experiencing nausea, vomiting, and a high fever with persistent tachycardia. This report summarizes and analyzes the clinical characteristics, diagnosis, and treatment process and outcomes to accumulate clinical experience and improve clinicians' understanding of this acute and life-threatening disease. Timely and appropriate treatment may help reduce the incidence of morbidity and mortality associated with EDKA and thyroid storm.

Keywords: sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i), euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis (EDKA), thyroid storms, diagnosis and treatment

Introduction

Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis (EDKA) is an acute complication of diabetes mellitus, characterized by patients presenting with anion gap metabolic acidosis, positive blood or urinary ketones, and typically blood glucose levels <13.9 mmol/L (<250.2 mg/dL) (normal reference value 3.9-6.1 mmol/L; 70-110 mg/dL) [1]. EDKA may result from several factors, including inadequate insulin secretory reserve, type 1 diabetes mellitus, and using medications, such as sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitors (SGLT2is) [2, 3]. SGLT2is lower blood glucose levels by inhibiting glucose reabsorption in the proximal tubules and increasing urinary glucose excretion [2]. Additionally, SGLT2is inhibit insulin secretion, promote glucagon secretion, and increase ketone body production, thereby triggering EDKA [4]. Clinically, EDKA presents similarly to regular DKA; however, it is more challenging to diagnose because of lower blood glucose levels. Thyroid storm (TS) is an acute complication of hyperthyroidism, which mostly develops from untreated or uncontrolled Graves disease and has a high fatality rate. TS and EDKA are acute endocrine gland complications. Diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA) is a known trigger for TS, and TS development can lead to severe DKA by increasing insulin resistance [5]. The coexistence of these conditions exacerbates endocrine disruption, rendering patient conditions unusually critical. In this study, we reviewed a case admitted to our hospital in June 2024.

Case Presentation

A 46-year-old woman with a 5-year history of type 2 diabetes mellitus, managed with oral dapagliflozin and shenqi jiangtang tablets but not regularly monitoring her blood glucose, was found to have a growing uterine fibroid over the past year. She was hospitalized in preparation for hysteroscopic surgery after an ultrasound showed that the uterine cavity occupancy was larger than before. A month earlier, she was also diagnosed with an enlarged goiter and abnormal thyroid function: TSH <0.01 μIU/mL (<0.01 mIU/L) (normal reference value 0.3-3.6 μIU/mL; 0.3-3.6 mIU/L). Recently, she experienced anxiety, poor appetite, palpitations, lethargy, and fatigue. On the day of admission, she suffered from nausea, vomiting, chest tightness, and shortness of breath, leading to her transfer to the endocrinology department for further treatment.

Diagnostic Assessment

The patient's vital signs were height: 160 cm; weight: 60 kg; body mass index: 23.4 kg/m2; waist circumference: 90 cm; hip circumference: 99 cm; waist-to-hip ratio: 0.9; body temperature: 38.3 °C; pulse: 170 beats/min; respiratory rate: 24 beats/min; and blood pressure: 150/74 mm Hg. The patient was conscious but showed signs of depression and shortness of breath, with a flushed face and moist skin. Notable findings included grade II thyroid enlargement, an audible vascular murmur, and finger tremors. Heart rate was regular at 170 beats/min.

Laboratory examination revealed the following. Fasting blood glucose: 7.68 mmol/L (138.39 mg/dL) (normal reference value 3.9-6.1 mmol/L; 70-110 mg/dL); glycated hemoglobin: 7.7% (normal reference value 4.8%-6.0%); β-hydroxybutyric acid: 85.37 mg/dL (8.20 mmol/L) (normal reference value 0.31-3.12 mg/dL; 0.03-0.3 mmol/L); uric acid: 430.5 µmol/L (7.24 mg/dL) (normal reference value 155-357 µmol/L; 2.61-6.00 mg/dL); carbon dioxide: 18.8 mmol/L (normal reference value 23-29 mmol/L); and brain natriuretic peptide: 189 pg/mL (54.62 pmol/L)(normal reference value 0-100 pg/mL; 0-28.90 pmol/L, double antibody Garcin immunoenzymatic assay). The diabetes autoantibodies (ICA, IAA, IA-2A, and GAD65) were negative. Urinalysis showed ketones 3+, glucose 3+; arterial blood gas analysis showed pH 7.051 (normal reference value 7.35-7.45), partial pressure of carbon dioxide 30.1 mm Hg (normal reference value 35-45 mm Hg), partial pressure of oxygen 161 mm Hg (normal reference value 80-100 mm Hg), bicarbonate 8.3 mmol/L (normal reference value 21.4-27.3 mmol/L), oxygen saturation 99.2%, lactate 1.80 mmol/L; thyroid function: TSH 0.006 μIU/mL (0.006 mIU/L) (normal reference value 0.3-3.6 μIU/mL; 0.3-3.6 mIU/L), free triiodothyronine (fT3) 23.52 pg/mL (36.221 pmol/L) (normal reference value 2.2-4.2 pg/mL; 3.388-6.468 pmol/L), free tetraiodothyronine (fT4) 9.953 ng/dL (129.389 pmol/L) (normal reference value 0.8-1.7 ng/dL; 10.4-22.1 pmol/L), total triiodothyronine (tT3) 521 ng/dL (8.023 nmol/L) (normal reference value 76.3-220.8 ng/dL; 1.175-3.4 nmol/L), total tetraiodothyronine (tT4) 33.74 µg/dL (438.62 nmol/L) (normal reference value 4.5-12.6 µg/dL; 58.5-163.8 nmol/L), thyrotropin receptor antibody 9.02 IU/L (normal reference value 0-1.75 IU/L), antithyroglobulin antibody 170.1 IU/mL (normal reference value 5-100 IU/mL), antithyroperoxidase antibody 11.08 IU/mL (normal reference value 1-16 IU/mL), and thyroglobulin >500 ng/mL (>1 nmol/L) (normal reference value 0.9-54 ng/mL; 0.002-0.108 nmol/L). Thyroid ultrasound showed abundant color flow signal in both lobes, diffuse thyroid changes, and a right lobe nodule (L60 × 18 × 23 mm, R60 × 21 × 25 mm, nodule TR4:8 × 6.5 × 7 mm). Blood routine, C-reactive protein, calcitoninogen, blood sedimentation, liver function, coagulation function, electrolytes, lipids, renal function, tumor indicators (AFP, CEA, CA125, CA199, CA724, and SCCA), and cardiac enzyme profiles were approximately normal.

The patient was diagnosed with TS, type 2 DKA (nonhyperglycemic), diffuse toxic goiter (Graves disease), and uterine cavity occupancy.

Treatment

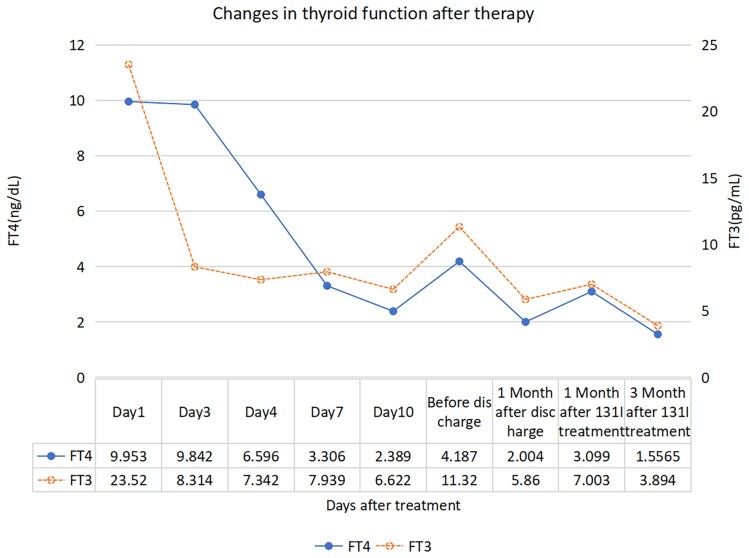

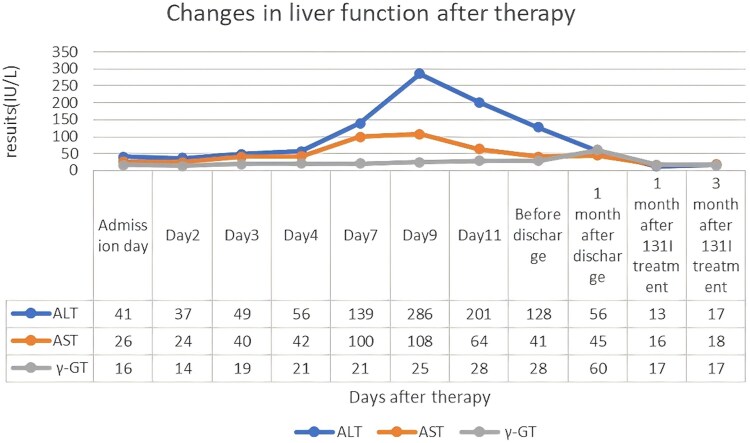

SGLT2i was immediately deactivated, and the patient immediately received oxygen inhalation, electrocardiography, oxygen saturation monitoring, aggressive rehydration, low-dose insulin to lower glucose, 100 mL of 5% sodium bicarbonate to correct acidosis, and oral propranolol hydrochloride (30 mg/dose, every 8 hours) to control ventricular rate. Omeprazole was used to inhibit acidity and protect the stomach against stress ulcers, while IV hydrocortisone (100 mg, every day) was used to enhance the body's stress response, inhibit TH release, and reduce the conversion of T4 to T3. She received propylthiouracil (300 mg initially and 300 mg 4 hours later) to inhibit neohormone synthesis and block peripheral T4 to T3 conversion. Additionally, she was given oral huganning tablets (1.4 g, 3 times per day). The main ingredients of huganning tablets are sedum sarmentosum, polygonum cuspidatum, salvia, and ganoderma. These can improve the ischemic and hypoxic state of liver cells by improving microcirculation and increasing the blood perfusion to the liver, and at the same time has the effects of an antioxidant and free radical scavenging to promote the metabolism and repair of liver cells, and it has a better therapeutic effect on the liver injury caused by hyperthyroidism [6]. On day 2, the patient's fever subsided, and the acidosis was basically corrected. On day 3, the patient's liver function was abnormal and progressively worsened, after which propylthiouracil was discontinued and replaced with methimazole. On day 7, owing to the patient's severe hepatic impairment oral, antithyroid medication was discontinued and replaced with methimazole cream (5 mg twice per day). Before discharge, the patient's liver function was rechecked and found to be better than before. Elective iodine-131 treatment was recommended. Changes in TH levels and liver function after treatment are detailed in Table 1, and the trends are shown in Figs. 1 and 2.

Table 1.

Laboratory analysis of thyroid and liver function before and after treatment

| Parameter | Values | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Time | Admission day | Before discharge | 3 months after iodine-131 treatment | Normal reference range |

| TSH | 0.006 μIU/mL 0.006 mIU/L |

< 0.004 μIU/mL < 0.004 mIU/L |

0.016 μIU/mL 0.016 mIU/L |

0.3-3.6 μIU/mL 0.3-3.6 mIU/L |

| FT3 | 23.52 pg/mL 36.221 pmol/L |

11.32 pg/mL 17.433 pmol/L |

3.894 pg/mL 6.0 pmol/L |

2.2-4.2 pg/mL 2.80-7.10 pmol/L |

| FT4 | 9.953 ng/dL 129.389 pmol/L |

4.187 ng/dL 54.431 pmol/L |

1.5565 ng/dL 20.235 pmol/L |

0.8-1.7 ng/dL 10.4-22.1 pmol/L |

| TT3 | 521 ng/dL 8.023 nmol/L |

− | − | 76.3-220.8 ng/dL 1.175-3.4 nmol/L |

| TT4 | 33.74 µg/dL 438.62 nmol/L |

− | − | 4.5-12.6 µg/dL 58.5-163.8 nmol/L |

| TgAb | 170.1 IU/mL | − | − | 5-100 IU/mL |

| Tg | > 500.0 ng/mL > 1 nmol/L |

− | − | 0.9-54 ng/mL 0.002-0.108 nmol/L |

| ALT | 41 U/L 41 IU/L |

128 U/L 128 IU/L |

17 U/L 17 IU/L |

7-40 U/L 7-40 IU/L |

| AST | 26 U/L 26 IU/L |

41 U/L 41 IU/L |

18 U/L 18 IU/L |

13-35 U/L 13-35 IU/L |

| γ-GT | 16 U/L | 28 U/L | 17 U/L | 7-45 U/L |

| 16 IU/L | 28 IU/L | 17 IU/L | 7-45 IU/L |

Abbreviations: –, not detected; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; FT3, free triiodothyronine; FT4, free thyroxine; Tg, thyroglobulin; TgAb, thyroglobulin antibody; TT3, total triiodothyronine; TT4, total thyroxine; γ-GT, γ-glutamyl transferase.

Figure 1.

This line graph demonstrates the changing trends of the patient's thyroid hormones after treatment. In the graph, the abscissa represents the time after treatment, and the ordinate represents the levels of thyroid hormones. The solid line represents free thyroxine (FT4), and the dashed line represents free triiodothyronine (FT3). This graph indicates that our treatment has a significant effect on improving the patient's thyroid hormone levels, suggesting that close monitoring of thyroid hormone changes is of great significance for evaluating the treatment efficacy. FT3, free triiodothyronine 1 pg/mL is about equal to 1.536 pmol/L. FT4, free thyroxine 1 ng/dL is about equal to 12.87 pmol/L. Reference range: FT3 2.2-4.2 pg/mL (2.80-7.10 pmol/L), FT4 0.8-1.7 ng/dL (10.4-22.1 pmol/L).

Figure 2.

This line graph shows the changing trends of the patient's liver function after treatment. In the graph, the abscissa represents the time after treatment, and the ordinate represents the levels of liver function. The blue line represents alanine aminotransferase (ALT), the orange line represents aspartate aminotransferase (AST), and the gray line represents γ-glutamyl transferase (γ-GT). This graph indicates whether the patient's liver function is affected by medications during the treatment period, suggesting that closely monitoring the changes in liver function is of great significance for the selection and adjustment of medications. ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; γ-GT, γ-glutamyl transferase. Reference range: ALT 7-40 IU/L, AST 13-35 IU/L, γ-GT 7-45 IU/L.

Outcome and Follow-up

The patient was discharged and continued using methimazole cream while taking oral hepatoprotective medications. One month after discharge, the patient's thyroid function and liver function were rechecked and found to be significantly better than before, and her condition was more stable. And then, she received oral iodine-131: 7.7 mCi (150 µCi/g) in the nuclear medicine clinic. Thyroid function and liver function were found to be essentially near normal on review 3 months after the patient received treatment (Table 1).

Discussion

SGLT2i is a class of novel drugs used to treat diabetes mellitus. The hypoglycemic mechanism involves the inhibition of glucose reabsorption by SGLT2 in the kidneys, which facilitates glucose excretion in the urine and consequently lowers blood glucose levels [4]. Approximately more than 30% of patients with SGLT2i-associated DKA exhibit lower or normal blood glucose levels [7]. SGLT2i induces ketogenesis by increasing glucagon levels, promoting lipolysis, and enhancing ketone body production [8]. Decreased insulin levels, which are regulated by blood glucose, along with a decrease in the serum insulin-to-glucagon ratio, result in a reduced ability of insulin to counteract lipolysis, which causes an increase in ketone body production [9]. Additionally, SGLT2i can increase acetoacetate reabsorption in renal tubules, elevate serum ketone bodies [10], and directly act on sodium-coupled monocarboxylate transporter-2, leading to increased ketone reabsorption [11]. SGLT2i can also cause osmotic diuresis and decreased glomerular filtration rate, resulting in hypovolemia and impaired ketone body clearance. This can result in significant ketonemia and acidosis [12]. SGLT2i resulted in a 3.7-fold increased risk of DKA in patients compared with other drugs [13]. Compared with DKA, EDKA has an insidious onset, with patients experiencing low blood glucose, polydipsia, and mild dehydration, making it difficult to detect in its early stages [14].

Thyroid function is closely related to glycometabolism, and normal thyroid function is required to maintain glycemic stability [15]. When hyperthyroidism is present, significant levels of thyroid hormones are released, accelerating glucose absorption by the small intestinal mucosa, increasing hepatic glycogen breakdown, and decreasing glycogen synthesis. Simultaneously, sympathetic nerve excitability increases, increasing catecholamine sensitivity, inhibiting insulin release and pushing the body into a high metabolic state. This causes further elevation of blood glucose and promotes adipose tissue decomposition and oxidation, resulting in the generation of large amounts of ketone bodies, which predisposes patients to DKA [16]. In clinical practice, determining the sequence in which TS and EDKA occur is difficult. However, it is usually assumed that uncontrolled hyperthyroidism leads to DKA, which induces TS [17].

We searched for articles on EDKA in patients taking SGLT2i since 2015, and there were 128 cases of EDKA. Most of the patients were female (73, 57%), and the most common clinical symptoms were gastrointestinal (nausea and vomiting 56%, abdominal pain 18.8%) and respiratory (dyspnea 30.5%). Only 2 of the cases were nondiabetic, and the majority were type 2 diabetic (109, 85.2%). Most of the patients had other comorbidities, including hypertension (32, 25%), heart disease (28, 21.9%), and dyslipidemia (26, 20.3%). The most frequently involved type of SGLT-2i was empagliflozin (57, 44.5%), and most patients (104, 81.2%) had identifiable predisposing factors, with the more common triggers being perioperative (43, 3.6%), infections (31, 24.2%), and fasting (30, 23.4%) (Table 2). Only 1 article reported a case of EDKA combined with TS. A 65-year-old man with type 2 diabetes who had been on an SGLT2i for more than 12 months presented with nausea, vomiting, fatigue, increased lethargy, and diarrhea and was diagnosed with EDKA and TS [18].

Table 2.

An examination of the clinical features of SGLT2i-associated EDKA since 2015

| Parameter | Number of patients, n = 128 |

|---|---|

| Age (± SD), y | 52.2 (14.2) |

| Gender, n (%) | Females, 73 (57%) |

| Males, 55 (43%) | |

| Type of diabetes, n (%) | Type 1, 17 (13.3%) Type 2, 109 (85.2%) |

| Nondiabetic, 2 (1.5%) | |

| Clinical presentation, n (%) | Nausea/vomiting, 72 (56.3%) Breathlessness, 39 (30.5%) Altered mental status, 31 (24.2%) Fatigue, 32 (25%) Diuresis, 8 (6.3%) Weight loss, 4 (3.1%) Abdominal pain, 24 (18.8%) Others, 12 (9.4%) |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | Diabetes, 126 (98.4%) Hypertension, 32 (25%) Dyslipidemia, 26 (20.3%) Heart disease, 28 (21.9%) Pancreatitis, 9 (7%) Thyroid disease, 11 (8.6%) Cancer, 7 (5.5%) Others, 34 (26.6%) |

| SGLT-2 inhibitor involved, n (%) | Empagliflozin, 57 (44.5%) Canagliflozin, 25 (19.5%) Dapagliflozin, 43 (33.6%) Ipragliflozin, 2 (1.6%) Tofogliflozin, 1 (0.8%) |

| Identifiable triggering factor, n (%) | Present, 104 (81.2%) |

| Triggering factor, n (%) | Alcohol use, 5 (3.9%) Perioperative, 43 (33.6%) Reduced carbohydrate/ketogenic diet, 11 (8.6%) Reduced insulin dosages, 9 (7%) Pancreatitis, 7 (5.5%) Infection, 31 (24.2%) Trauma, 2 (1.6%) Cancer, 2 (1.6%) Heart disease, 10 (7.8%) Thyroid disease, 1 (0.8%) Reduced caloric intake/fasting, 30 (23.4%) Others, 3 (2.3%) |

| Days for symptoms to improve (± SD) | 2 (2) d |

| Outcome, n (%) | Alive, 125 (97.7%) Death, 3 (2.3%) |

Abbreviations: EDKA, euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis; SGLT2i, sodium-glucose transport protein 2 inhibitor.

In summary, EDKA is not hyperglycemic and has an insidious onset, making it easy to miss in clinical settings. Therefore, clinicians should be vigilant for EDKA in patients with diabetes, metabolic acidosis symptoms, and positive blood and urine ketones. First, EDKA can trigger TS. Second, patients with EDKA who present with persistent tachycardia, difficulty controlling heart rate with medications, or impaired consciousness should be evaluated for possible comorbid TS [15]. Third, if EDKA complicates TS, the causative factors, including SGLT2i use, infection, or dietary modification, should be addressed, and both conditions should be treated simultaneously. Early rehydration, low-dose insulin therapy, electrolyte balance, and management of antithyroid crises are important to improve patient outcomes [19].

The safe use of SGLT2 inhibitors in DKA is unclear. High-risk patients, such as those with low insulin production, dietary limits, risk of dehydration, sudden insulin reduction, increased insulin needs due to illness or surgery, and type 1 diabetes, face a higher risk of ketoacidosis on SGLT2is. The Food and Drug Administration advises stopping these drugs at least 3 days before surgery to reduce ketosis risk [20-22]. Additionally, starting low-dose long-acting insulin is recommended before surgery [23]. SGLT2i can be resumed postsurgery once a normal diet is reestablished. Patients should maintain sufficient carbohydrate and fluid intake during SGLT2i use to prevent ketosis. Before restarting SGLT2i after stopping due to EDKA, evaluate the EDKA triggers and assess the benefits and risks [24].

Learning Points

This article highlights a rare case of diabetic ketoacidosis with thyroid crisis, rarely documented, noting that ketoacidosis can occur without hyperglycemia and that both conditions may trigger each other.

We recommend considering SGLT2 inhibitors and thyroid crisis as potential triggers for nonhyperglycemic ketoacidosis. Even with normal blood glucose levels, the risk of ketoacidosis should not be overlooked. Appropriate laboratory tests, like anion gap, β-hydroxybutyric acid, blood and urinary ketones, and carbon dioxide partial pressure, should be conducted as needed.

This will help to identify cases of SGLT2 inhibitor-induced euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis combined with thyroid crisis and provide timely intervention.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the patient and her family for allowing their case history to be published.

Contributor Information

Ning Bai, Department of Endocrinology, Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan University, Wuxi, Jiangsu Province 214000, China.

Nan Wang, Wuxi School of Medicine, Jiangnan University, Wuxi, Jiangsu Province 214122, China.

Ya Chen, Department of Endocrinology, Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan University, Wuxi, Jiangsu Province 214000, China.

Jian Zhu, Department of Endocrinology, Affiliated Hospital of Jiangnan University, Wuxi, Jiangsu Province 214000, China.

Contributors

All authors made individual contributions to the authorship. N.B. and N.W. were involved in the diagnosis and management of the patient, as well as in drafting the manuscript and submitting it. Y.C. and J.Z. provided significant contributions to revising and improving the manuscript. All authors reviewed and approved the final draft.

Funding

This study was supported by Wuxi “Double Hundred” Young and Middle-aged Medical and Healthcare Talents Cultivation Program (BJ2023047).

Disclosures

The authors report no conflicts of interest. All data presented in this case report were obtained from the patient's medical records during hospitalization in the Jiangnan University Hospital. The patient provided written informed consent for the use of their medical information for research and publication purposes. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and all relevant ethical regulations.

Informed Patient Consent for Publication

Signed informed consent was obtained directly from the patient.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of some or all data generated or analyzed during this study to preserve patient confidentiality or because they were used under license. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.

References

- 1. Ji LW. Concerns about non-hyperglycemic ketoacidosis induced by sodium-glucose transporter protein 2 inhibitors. J Adverse Drug React. 2021;23:281‐284. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Chen SP, Li M, Liu YF, et al. Research progress of non-hyperglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis. Chin Emerg Med. 2022;42:697‐700. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Kietaibl A-T, Fasching P, Glaser K, Petter-Puchner AH. New diabetic medication sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors can induce euglycemic ketoacidosis and mimic surgical diseases: a case report and review of literature. Front Surg. 2022;9:828649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Modi A, Agrawal A, Morgan F. Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis: a review. Curr Diabetes Rev. 2017;13(3):315‐321. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Li SJ. Progress of clinical research on diabetes mellitus and thyroid disease. Diabetes Clin. 2014;8(9):428. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Song JM. Evaluation on the clinical application of huganning tablets. Eval Anal Drug Use Hosp China. 2013;13(02):105‐107. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Bonora BM, Avogaro A, Fadini GP. Sodium-glucose co-transporter-2 inhibitors and diabetic ketoacidosis: an updated review of the literature. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20(1):25‐33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Kampmeyer D, Sayk F. Euglycemic ketoacidosis—rare condition on the rise. Dtsch Med Wochenschr. 2021;146(19):1265‐1269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Ogawa W, Sakaguchi K. Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis induced by SGLT2 inhibitors: possible mechanism and contributing factors. J Diabetes Investig. 2016;7(2):135‐138. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Blau JE, Tella SH, Taylor SI, Rother KI. Ketoacidosis associated with SGLT2 inhibitor treatment: analysis of FAERS data. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2017;33(8):e2924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Mandal AK, Mount DB. The molecular physiology of uric acid homeostasis. Annu Rev Physiol. 2015;77(1):323‐345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Sampani E, Sarafidis P, Papagianni A. Euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis as a complication of SGLT-2 inhibitors: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment. Expert Opin Drug Saf. 2020;19(6):673‐682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Dutta S, Kumar T, Singh S, Ambwani S, Charan J, Varthya SB. Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis associated with SGLT2 inhibitors: a systematic review and quantitative analysis. J Family Med Prim Care. 2022;11(3):927‐940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Menghoum N, Oriot P, Hermans MP. Clinical and biochemical characteristics and analysis of risk factors for euglycaemic diabetic ketoacidosis in type 2 diabetic individuals treated with SGLT2 inhibitors: a review of 72 cases over a 4.5-year period. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2021;15(6):102275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wang YY, Pan X, Zhu XH, Sun K, Li TT, Jiang DM. Multiple organ failure caused by thyroid storm and diabetes ketoacidosis following radioactive iodine-131 treatment: a case report. J Qiqihar Univ Med. 2023;44(16):1542‐1545. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Deng Y, Zheng W, Zhu J. Successful treatment of thyroid crisis accompanied by hypoglycemia, lactic acidosis, and multiple organ failure. Am J Emerg Med. 2012;30(9):2094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Potenza M, Via MA, Yanagisawa RT. Excess thyroid hormone and carbohydrate metabolism. Endocr Pract. 2009;15(3):254‐262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Strawn KD, Davis KW. The interconnectedness of euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis with concomitant thyroid storm: a case report. Cureus. 2024;16(4):e58696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Muneer M, Akbar I. Acute metabolic emergencies in diabetes: DKA, HHS and EDKA. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2021;1307:85‐114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Handelsman Y, Henry RR, Bloomgarden ZT, et al. American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology position statement on the association of sglt-2 inhibitors and diabetic ketoacidosis. Endocr Pract. 2016;22(6):753‐762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Pace DJ, Dukleska K, Phillips S, Gleason V, Yeo CJ. Euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis due to sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor use in two patients undergoing pancreatectomy. J Pancreat Cancer. 2018;4(1):95‐99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Pujara S, Ioachimescu A. Prolonged ketosis in a patient with euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis secondary to dapagliflozin. J Investig Med High Impact Case Rep. 2017;5(2):2324709617710040. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Bteich F, Daher G, Kapoor A, Charbek E, Kamel G. Post-surgical euglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis in a patient on empagliflozin in the intensive care unit. Cureus. 2019;11(4):e4496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Xue XK, Guo WH, Li HM. SGLT-2 inhibitor to non-hyperglycemic diabetic ketoacidosis in a case and literature review. Paper presented at: Proceedings of the Seventh National Rehabilitation and Clinical Pharmacy Academic Exchange Conference(I); 2024, Nanjing, Jiangsu, China.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Restrictions apply to the availability of some or all data generated or analyzed during this study to preserve patient confidentiality or because they were used under license. The corresponding author will on request detail the restrictions and any conditions under which access to some data may be provided.