Abstract

Background

Patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) are often pretreated with unfractionated heparin (UFH) before a primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI). UFH pretreatment is intended to lessen the thrombotic burden, but there have been conflicting study findings on its safety and efficacy. We assessed the risks and benefits of UFH pretreatment with a retrospective analysis of registry data from the STEMI network of a German metropolitan region.

Methods

Data from patients with STEMI referred for PPCI from 2005 to 2020 were evaluated with an adjusted outcome analysis, including propensity score matching (PSM). The endpoints included the patency of the infarct-related artery (IRA) after PPCI, in-hospital mortality, access-site bleeding, and the peak creatine kinase (CK) level.

Results

We assessed data from 4632 patients with STEMI: 4420 (95.4%) were pretreated with UFH, and 212 (4.6%) were not. After PSM of 511 vs. 187 patients, the adjusted odds ratios for the various endpoints were (pretreatment vs. no pretreatment, with 95% confidence intervals): for impaired flow of the IRA, 1.01 [0.59; 1.74]; for in-hospital mortality, 1.46 [0.88; 2.42]; and for access-site bleeding, 0.59 [0.14; 2.46]. The peak creatine kinase levels were similar in the two groups (median, 1248.0 vs. 1376.5 U/L, estimated difference –134 [-611; 341]).

Conclusion

UFH pretreatment was less frequently performed in STEMI patients who had undergone cardiopulmonary resuscitation. UFH pretreatment was not associated with increased access-site bleeding, nor was it found to have significantly higher efficacy with respect to the relevant endpoints. The risks and benefits of UFH pretreatment should be weighed individually in each case, as evidence from high-quality clinical trials is lacking. Data from the existing literature suggest that no pretreatment is an option to be considered, as are certain alternative antithrombotic strategies.

ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) requires rapid diagnosis and structured treatment to minimize the ischemic interval (1, 2). Primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PPCI) or fibrinolysis are central treatment options and need to be considered at first medical contact (FMC). Projected time frames determine decision-making regarding reperfusion strategy (1, 2). Adjunctive antithrombotic therapy is a cornerstone and is indicated as soon as the diagnosis is established—even in prehospital settings (1, 2). In this regard, the current European STEMI guideline recommends the administration of acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) and unfractionated heparin (UFH) in patients suitable for PPCI (1, 2). In contrast, the American STEMI guideline does not explicitly recommend UFH pretreatment; instead, UFH should be used during the time of PPCI to regulate the activated clotting time (3).

To date, UFH pretreatment of patients with STEMI has been associated with improved patency of the infarct-related artery (IRA) prior to PPCI, but this has not translated into beneficial mid- and long-term clinical outcomes (4–6).

In the absence of adequately structured randomized controlled trials, evaluations of robust observational data are needed to weigh UFH pretreatment against peri-interventional administration. An analysis of a guideline-conform infarction network in a metropolitan region was carried out to address the risks and benefits of UFH pretreatment.

Material and methods

This retrospective multicenter registry analysis included all STEMI patients treated between 1 January 2005 and 30 December 2020 in Cologne, Germany. The structure of the Cologne Infarction Network (Kölner Infarkt Modell, KIM) has been described (7–9). All treated persons with STEMI assigned to PPCI after FMC and complete information on anticoagulatory pretreatment were eligible.

Pretreatment with ASA and heparin and the timing thereof were at the treating physician’s discretion, but pretreatment was encouraged by a contemporary position paper (10). Pretreatment with UFH was the standard of care for KIM, and the administration of 5000 units is the most common strategy in Germany (10). The measured outcomes were:

I) IRA flow after percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) (defined by the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction [TIMI] classification, limitation: TIMI < 3 [11])

II) In-hospital mortality

III) Access-site bleeding

IV) Maximum creatine kinase (CK) level as surrogate for infarct size (12)

Propensity score matching (PSM) was used to adjust the groups. Because the characteristics “resuscitation” and “prior use of oral anticoagulants” (OAC) might have influenced both the decision regarding UFH pretreatment (13, 14) and the outcomes, subgroups were formed post hoc and again adjusted using PSM. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) were estimated. Further details of the methods are provided in the eMethods.

eMethods.

Material and methods

This retrospective multicenter registry study included all patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) treated between 1 January 2005 and 30 December 2020 in Cologne, Germany. The structure of the Cologne Infarction Network (Kölner Infarkt Modell, KIM) has been described (7–9). KIM is a co-operation among all of Cologne’s 16 acute-care hospitals and the fire department over an area of 400 km2 with a total of 1.1 million inhabitants. Seven of the 16 hospitals run percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) services 24 h a day, 7 days a week. Patients with STEMI triaged to PCI for whom complete information on prior anticoagulant treatment were available were included for analysis.

Treatment plan

Patients with STEMI who called the emergency number and whose first medical contact was with the emergency services were transferred directly after diagnosis to the cardiac catheterization laboratory of a PCI center. Patients who presented personally to non-PCI centers were immediately transferred to a PCI center. STEMI diagnosis required typical clinical symptoms in combination with ST-segment elevation in at least two contiguous leads (gender-, age-, and lead-specific thresholds were defined in accordance with current guidelines) or assumed new-onset left bundle branch block (LBBB) on a 12-lead electrocardiogram (1). In the case of STEMI, emergency service personnel usually notified an emergency physician. Pretreatment with UFH or acetylsalicylic acid (ASA) was at the emergency physician’s discretion. UFH pretreatment was not mandatory, but was recommended in a contemporary position paper (10). Consequently pretreatment with UFH was the strategy selected in the majority of cases, and administration of 5000 units is the usual practice in Germany (10). The decision on how treatment should proceed (e.g., PCI, peri-interventional administration of heparin) was at the discretion of the treating interventional cardiologists, within the framework of the current guidelines (2).

Prehospital fibrinolysis was not recommended in the KIM registry with dense care structures, and was just a bailout strategy (e.g., in the event of refractory cardiac arrest in STEMI).

Measured parameters and outcomes

Patient characteristics were extracted from the patients’ medical records, The following parameters were documented: age, sex, prehospital treatment data, hospital treatment, procedural data, inpatient treatment. Patients were then stratified according to whether they had received UFH pretreatment. The measured outcomes were:

I) Post-PCI flow through the infarct-related artery (IRA) (defined by the Thrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction [TIMI] classification, impairment TIMI < 3 [11])

II) In-hospital mortality

III) Access-site bleeding

IV) Maximum creatine kinase (CK) level as surrogate for infarct size (12). CK was measured after arrival at the hospital or immediately after PCI and then daily until discharge.

Propensity scores

In this non-randomized retrospective study, propensity score matching (PSM) was used to adjust the groups and restrict confounding. The covariates considered were age, sex, ASA as long-term medication, oral anticoagulants (OAC) as long-term medication, type of first medical contact (FMC), symptom-to-FMC time, ECG phenotype (STEMI/LBBB), use of vasopressors, intubation, culprit vessel, and stent implantation.

Complete cases were identified in 75% of data sets. Multiple imputations (m = 25) were carried out, including 10 iterations and resulting in 25 complete data sets. The following parameters were considered for imputations: age, sex, type of infarction, use of vasopressors, intubation, ASA as long-term medication, OAC as long-term medication, type of FMC, symptom-to-FMC time, culprit vessel, and stent implantation. Outcome variables and variables with = 20% missing data were excluded from imputation. Propensity scores were determined using logistic regression with UFH pretreatment (yes/no) as the dependent variable in each data set. Next, propensity scores from all data sets were averaged for each patient following Rubin’s rule, resulting in one single propensity score per person. The logit was then calculated and used as the basis for further analysis.

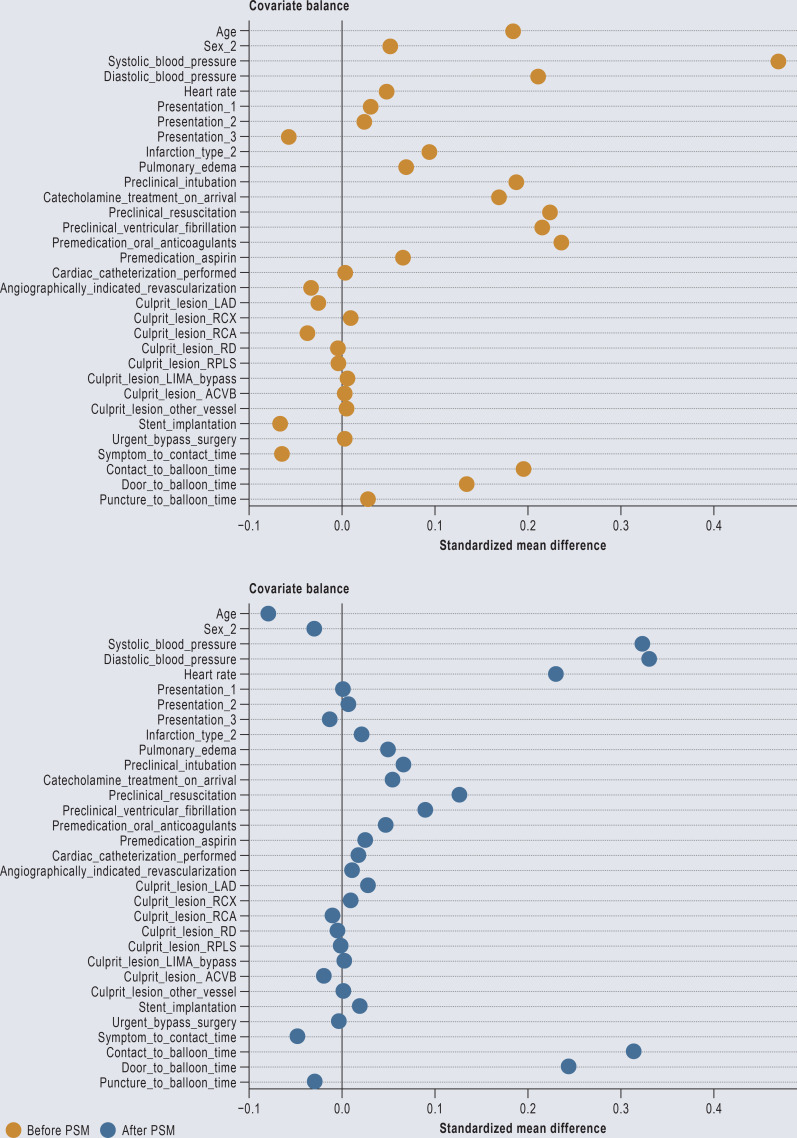

Each patient without UFH pretreatment was propensity score-matched with a maximum of three patients who had received UFH pretreatment (1:3) using the nearest neighbor method (with a caliper of 0.2 × standard deviation of the logit propensity score). As a result, we obtained a subset of 187 patients without and 511 matched patients with UFH pretreatment (Figure). The balances of covariates between the groups before and after matching were assessed using the standardized mean differences (SMD) (< 0.1 was defined as negligible). Because the characteristics resuscitation and OAC might have contributed to pretreatment decision (13, 14) and the patients’ outcome, post-hoc subgroup analyses were performed. In the subgroups: a) resuscitated persons, b) non-resuscitated persons, c) patients with OAC, and d) patients without OAC, PSM was carried out as detailed above and an adjusted analysis performed.

Statistical analysis

The data points were expressed in terms of mean values (± standard deviation), median (interquartile range), or frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were assessed for normal distribution using box plots and histograms, and Student’s t-test or the Mann–Whitney U-test were used accordingly in the unmatched cohort. Fisher’s exact test and the chi-square test were used to assess categorical variables in the unmatched cohort. Odds ratios (OR) and 95% confidence intervals were calculated in the unmatched cohort, with UFH pretreatment defined as reference. In the case of continuous variables, a mixed linear regression model was used. In the regression analyses the matching of pairs (assignment) was included as stratum variable to adjust for random effects. Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS Statistics Version 27.0.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and R Version 4.3.1 (MatchIt, cobalt and mice package; Survival package).

The registry study complies with the tenets of the Declaration of Helsinki. The local ethics review board approved the KIM registry (decision no. 06–064), and written informed consent to participate in the registry was obtained from all patients. The study was reported in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice, and a detailed STROBE statement is provided (eSupplement).

Unadjusted cohort

A total of 4768 patients were included in the KIM registry. Of these, 4632 were eligible for the present analysis: 4420 (95.4%) with and 212 (4.6%) without UFH pretreatment (Figure). The patients’ characteristics are presented in the eTable. There were relevant differences: patients without pretreatment were older and more often presented with pulmonary edema or ventricular fibrillation. Furthermore, they more frequently required resuscitation, intubation, or vasopressor treatment. Patients without pretreatment were more likely to be taking long-term OAC or ASA and had higher systolic blood pressure and a shorter interval from symptom onset to first contact.

Figure.

Flow chart

KIM, Kölner Infarkt Modell (Cologne Infarction Network); UFH, unfractionated heparin

eTable. Characteristics and procedural data.

| Overall cohort | Unmatched cohort | Main cohort after PSM | |||||

| UFH pretreatment | No pretreatment | SMD | UFH pretreatment | No pretreatment | SMD | ||

| Characteristics | |||||||

| Participants, n (%) | 4768 | 4420 | 212 | 511 | 187 | ||

| Age, median (years) | 63.0 (IQR 21) | 63.0 (IQR 21) | 67.0 (IQR 21) | 0.18 | 65.0 (IQR 21) | 65.0 (IQR 20) | −0.08 |

| Male, n (%) | 3433 (73.6) | 3228 (73.9) | 144 (68.6) | 0.05 | 334 (72.3) | 169 (74.8) | −0.03 |

| Systolic blood pressure, median (mm Hg) | 140.0 (IQR 42) | 140.0 (IQR 40) | 152.0 (IQR 37) | 0.47 | 138.0 (IQR 41) | 152.0 (IQR 36) | 0.32 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, median (mm Hg) | 81.0 (IQR 26) | 81.0 (IQR 26) | 90.0 (IQR 20) | 0.21 | 80.0 (IQR 23) | 90.0 (IQR 20) | 0.33 |

| Heart rate, median (per minute) | 80.0 (IQR 24) | 80.0 (IQR 24) | 89.5 (IQR 27) | 0.05 | 81.0 (IQR 33) | 90.0 (IQR 24) | 0.23 |

| FMC – Emergency medical service – Non-PCI center – PCI center |

3265 (69.8) 844 (18.0) 571 (12.2) |

3027 (69.4) 781 (17.9) 551 (12.6) |

146 (72.6) 41 (20.4) 14 (7.0) |

0.03 0.02 −0.06 |

361 (72.1) 102 (20.4) 38 (7.6) |

129 (72.9) 35 (19.8) 13 (7.3) |

0.00 0.01 −0.01 |

| ECG at FMC – STEMI – LBBB |

4219 (92.5) 344 (7.5) |

4090 (92.8) 319 (7.2) |

115 (83.3) 23 (16.7) |

0.09 |

430 (84.3) 80 (15.7) |

103 (86.6) 16 (13.4) |

0.02 |

| Pulmonary edema, n (%) | 372 (8.4) | 351 (8.2) | 20 (15.4) | 0.07 | 70 (14.3) | 18 (15.9) | 0.05 |

| Intubation, n (%) | 546 (11.8) | 474 (11) | 59 (29.8) | 0.19 | 141 (28.7) | 38 (21.7) | 0.07 |

| Vasopressors, n (%) | 540 (11.7) | 471 (11) | 55 (27.9) | 0.17 | 134 (27.2) | 35 (20.1) | 0.06 |

| Resuscitation, n (%) | 463 (14.6) | 401 (13.5) | 50 (36.0) | 0.23 | 109 (30.0) | 34 (28.1) | 0.13 |

| Ventricular fibrillation, n (%) | 152 (14.6) | 132 (13.9) | 11 (35.4) | 0.22 | 38 (31.9) | 6 (25.0) | 0.09 |

| OAC in prior daily medication | 483 (11.8) | 444 (11.1) | 39 (34.8) | 0.24 | 110 (26.0) | 24 (24.7) | 0.05 |

| ASA in prior daily medication | 1143 (27.7) | 1104 (27.6) | 38 (34.2) | 0.07 | 150 (35.3) | 30 (31.3) | 0.03 |

| Procedural data | |||||||

| Immediate coronary angiography, n (%) | 4560 (99.0) | 4248 (98.9) | 193 (99.5) | 0.01 | 479 (98.8) | 170 (100) | 0.02 |

| Culprit vessel identified, n (%) | 3999 (88.9) | 3727 (89.0) | 161 (85.6) | −0.03 | 395 (84.0) | 144 (86.7) | 0.01 |

| Culprit vessel, (%) | |||||||

| – LAD | 1805 (38.3) | 1680 (38.3) | 210 (35.7) | −0.03 | 186 (36.8) | 69 (37.3) | 0.03 |

| – RCX | 588 (12.5) | 540 (12.3) | 28 (13.3) | 0.01 | 65 (12.9) | 22 (11.9) | 0.01 |

| – RCA | 1570 (33.3) | 1480 (33.7) | 63 (30.0) | −0.04 | 152 (30.1) | 58 (31.4) | −0.01 |

| – RD | 153 (3.2) | 141 (3.2) | 6 (2.9) | 0.00 | 15 (3.0) | 6 (3.2) | 0.00 |

| – RPLS | 147 (3.1) | 125 (2.8) | 5 (2.4) | 0.00 | 14 (2.8) | 4 (2.2) | 0.00 |

| – LIMA graft | 15 (0.3) | 12 (0.3) | 2 (0.1) | 0.01 | 0 (0) | 1 (0.5) | 0.00 |

| – SVG | 58 (1.2) | 54 (1.2) | 3 (1.4) | 0.00 | 8 (1.6) | 2 (1.1) | −0.02 |

| – Other | 110 (2.3) | 101 (2.3) | 6 (2.9) | 0.01 | 13 (2.6) | 5 (2.7) | 0.00 |

| Stent implantation, n (%) | 3710 (82.3) | 3459 (82.4) | 143 (75.7) | −0.07 | 353 (74.9) | 129 (77.2) | 0.02 |

| Urgent CABG | 157 (3.5) | 147 (3.5) | 7 (3.8) | 0.00 | 19 (4.1) | 5 (3.1) | 0.00 |

| Symptom-to-FMC time, median (minutes) | 100.0 (IQR 270) | 105.0 (IQR 288) | 60.0 (IQR 236) | −0.06 | 60.0 (IQR 220) | 90.0 (IQR 274) | −0.05 |

| FMC-to-balloon time, median (minutes) | 86.0 (IQR 40) | 85.0 (IQR 41) | 101.0 (IQR 46) | 0.20 | 93.0 (IQR 47) | 101.5 (IQR 43) | 0.32 |

| Door-to-balloon time, median (minutes) | 48.0 (IQR 36) | 48.0 (IQR 35) | 51.0 (IQR 42) | 0.13 | 44.0 (IQR 36) | 53.5 (IQR 42) | 0.24 |

| Puncture-to-balloon time, median (minutes) | 20.0 (IQR 14) | 20.0 (IQR 14) | 20.5 (IQR 22) | 0.03 | 20.0 (IQR 15) | 20.0 (IQR 22) | −0.03 |

ASA, acetylsalicylic acid; CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; ECG, electrocardiogram; FMC, first medical contact; IQR, interquartile range; LAD: left anterior descending artery; LBBB, left bundle branch block; LIMA, left internal mammary artery; OAC, oral anticoagulants; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; PSM, propensity score matching; RCA, right coronary artery; RCX, circumflex artery; RD, diagonal branch; RPLS, ramus posterolateralis; SMD, standardized mean difference; STEMI, ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction; SVG: saphenous vein graft; UFH, unfractionated heparin

Impaired post-PCI flow in the IRA (TIMI < 3) was detected in 13.3% of pretreated patients and in 19.4% of those without pretreatment (OR 0.63 [0.43; 0.93]). The respective rates of in-hospital mortality were 8.9% and 19.5% (OR 0.40 [0.28; 0.57]). Access-site bleeding occurred in 0.9% of pretreated patients and 1.4% of those without pretreatment (OR 0.65 [0.2; 2.11]). The median maximum CK levels were 1118.0 and 1376.5 U/L, respectively.

Propensity score matching

Overall, 698 patients from the unadjusted cohort could be matched by PSM, 511 with and 187 without UFH pretreatment (Table 1). The groups were well balanced with regard to the logit of the propensity score and its distribution (eFigures 1 and 2).

Table 1. Patient characteristics after propensity matching of the main cohort.

| UFH pretreatment | No pretreatment | SMD | |

| Participants, n (%) | N = 511 | N = 187 | |

| Age, median (years) | 65.0 (IQR 21) | 65.0 (IQR 20) | −0.08 |

| Male, n (%) | 334 (72.3) | 169 (74.8) | −0.03 |

| Systolic blood pressure, median, (mm Hg) | 138.0 (IQR 41) | 152.0 (IQR 36) | 0.32 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, median (mm Hg) | 80.0 (IQR 23) | 90.0 (IQR 20) | 0.33 |

| Heart rate, median (per minute) | 81.0 (IQR 33) | 90.0 (IQR 24) | 0.23 |

| FMC – Emergency medical service – Non-PCI center – PCI center |

361 (72.1) 102 (20.4) 38 (7.6) |

129 (72.9) 35 (19.8) 13 (7.3) |

0.00 0.00 −0.01 |

| Pulmonary edema, n (%) | 70 (14.3) | 18 (15.9) | 0.05 |

| Intubation, n (%) | 141 (28.7) | 38 (21.7) | 0.07 |

| Vasopressors, n (%) | 134 (27.2) | 35 (20.1) | 0.06 |

| Resuscitation, n (%) | 109 (30.0) | 34 (28.1) | 0.13 |

| Ventricular fibrillation, n (%) | 38 (31.9) | 6 (25.0) | 0.09 |

| OAC in prior daily medication | 110 (26.0) | 24 (24.7) | 0.05 |

| ASA in prior daily medication | 150 (35.3) | 30 (31.3) | 0.03 |

| Symptom-to-FMC time, median (minutes) | 60.0 (IQR 220) | 90.0 (IQR 274) | −0.05 |

| FMC-to-balloon time, median (minutes) | 93.0 (IQR 47) | 101.5 (IQR 43) | 0.32 |

| Door-to-balloon time, median (minutes) | 44.0 (IQR 36) | 53.5 (IQR 42) | 0.24 |

| Puncture-to-balloon time, median (minutes) | 20.0 (IQR 15) | 20.0 (IQR 22) | −0.03 |

ASA, Acetylsalicylic acid; FMC, first medical contact; IQR, interquartile range, OAC, oral anticoagulants; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SMD, standardized mean difference; UFH, unfractionated heparin

eFigure 1.

Standardized mean difference for continuous variables and mean difference for categorical variables before (orange) and after (blue) propensity score matching (PSM)

eFigure 2.

Density of propensity scores in the group pretreated with unfractionated heparin (green) and the not pretreated group (red) before and after matching

The findings of quantitative analysis are shown in Table 2. Impaired post-PCI flow in the IRA (TIMI < 3) was present in 18.3% of pretreated patients and 16.9% of those without pretreatment (OR 1.01 [0.59; 1.74]). The respective in-hospital mortality rates were 17.3% and 15.1% (OR 1.46 [0.88; 2.42]). Access-site bleeding occurred in 1.0% of pretreated patients and 1.6% of those without pretreatment (OR 0.59 [0.14; 2.46]). The maximum CK levels of the two groups were comparable (Table 3).

Table 2. Outcome analysis following propensity score matching in main cohort and subgroups.

| UFH pretreatment | No pretreatment | OR* [95% CI] | |

| PSM main cohort | N = 511 | N = 187 | |

| Post-PCI IRA flow (TIMI < 3), % | 18.3 | 16.9 | 1.01 [0.59; 1.74] |

| In-hospital mortality, % | 17.3 | 15.1 | 1.46 [0.88; 2.42] |

| Access-site bleeding, % | 1.0 | 1.6 | 0.59 [0.14; 2.46] |

| PSM subgroup: resuscitated patients | n = 79 | n = 35 | |

| Post-PCI IRA flow (TIMI < 3), % | 22.6 | 22.1 | 1.13 [0.42; 3.05] |

| In-hospital mortality, % | 49.4 | 48.6 | 1.07 [0.49; 2.34] |

| Access-site bleeding, % | 1.4 | 0 | Not applicable |

| PSM subgroup: non-resuscitated patients | n = 184 | n = 71 | |

| Post-PCI IRA flow (TIMI < 3), % | 16.4 | 16.4 | 1.00 [0.40; 2.47] |

| In-hospital mortality, % | 6.1 | 10.1 | 0.49 [0.17; 1.37] |

| Access-site bleeding, % | 1.7 | 4.3 | Not applicable |

| PSM subgroup: patients with OAC | n = 65 | n = 27 | |

| Post-PCI IRA flow (TIMI < 3), % | 26.3 | 9.1 | 5.39 [0.65; 44.61] |

| In-hospital mortality, % | 15.4 | 22.2 | 0.68 [0.22; 2.15] |

| Access-site bleeding, % | 1.6 | 3.8 | Not applicable |

| PSM subgroup:patients without OAC | n = 162 | n = 64 | |

| Post-PCI IRA flow (TIMI < 3), % | 10.5 | 15.5 | 0.67 [0.26; 1.77] |

| In-hospital mortality, % | 9.3 | 21.0 | 0.51 [0.2; 1.32] |

| Access-site bleeding, % | 0.6 | 1.6 | Not applicable |

*UFH pretreatment as reference category

CI: Confidence interval; IQR: interquartile range; IRA: infarct-related artery; OAC, oral anticoagulants; OR: odds ratio; PCI: percutaneous coronary intervention; PSM, propensity score matching; TIMI: thrombolysis in myocardial infarction; UFH: unfractionated heparin

Table 3. Infarct size following propensity score matching in main cohort and subgroups.

| UFH pretreatment | No pretreatment | Calculated difference [95% CI] (UFH pretreatment as reference category) | |

| PSM cohort | N = 511 | N = 187 | |

| Maximum CK, U/L: median (IQR) | 1248 (2426) | 1376.5 (2365) | −134 U/L [−611; 341] |

| PSM subgroup: resuscitated patients | n = 79 | n = 35 | |

| Maximum CK, U/L: median (IQR) | 2889 (3416) | 3350 (7251) | −51 U/L [−2571; 2469] |

| PSM subgroup: non-resuscitated patients | n = 184 | n = 71 | |

| Maximum CK, U/L: median (IQR) | 872.5 (1790) | 1060 (2481) | −175 U/L [−745; 396] |

| PSM subgroup: patients with OAC | n = 65 | n = 27 | |

| Maximum CK, U/L: median (IQR) | 813 (1785) | 520 (1672) | 769 U/L [−344; 1882] |

| PSM subgroup: patients without OAC | n = 162 | n = 64 | |

| Maximum CK, U/L: median (IQR) | 1293 (2213) | 1421 (2337) | −519 U/L [−1242; 203] |

CI, Confidence interval; CK, creatine kinase; IQR, interquartile range; UFH, unfractionated heparin

Subgroup analyses

“Resuscitation” and “prior oral anticoagulation” were numerically and clinically the most significant differences. In particular, resuscitated STEMI patients were less likely to receive UFH pretreatment (96.7% vs. 88.9%, p < 0.001). Notably, patients pretreated with UFH had lower in-hospital mortality rates in all subgroups except resuscitation. The detailed results of subgroup analysis can be found in Tables 2 and 3. Access-site bleeding occurred so infrequently that regression analysis could not be performed. For the remaining evaluations, interpretation of the OR and CI revealed similar treatment outcomes across the groups.

Discussion

This retrospective registry study is the first to analyze the risks and benefits of UFH pretreatment and its interaction with flow in the IRA following PCI in STEMI. A high proportion of patients included in the study were resuscitated. Adjusted analysis on the basis of PSM showed the following:

Patients with STEMI who required intubation, vasopressor treatment, or resuscitation were less likely to received UFH pretreatment despite their higher thrombotic burden.

Patients without pretreatment had a higher prevalence of prior long-term OAC treatment.

UFH pretreatment was not associated with IRA flow following PCI.

The risk of in-hospital mortality was lower after UFH pretreatment, in patients on long-term OAC treatment, and in those without resuscitation; it was not lower among resuscitated patients.

UFH pretreatment was not associated with an elevated risk of access-site bleeding.

The conventional use of UFH as pretreatment and during PPCI in STEMI has been questioned before (1, 4, 15, 16). In contextualizing the present observations, it should be noted that UFH pretreatment was the standard of care in KIM and was carried out in 92.7% of patients. This was in line with the contemporary European and German recommendations (1, 10). In contrast, international observational studies documented much lower rates of UFH pretreatment in STEMI. In the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR), only one third received UFH pretreatment (5). Similarly, only 30% of patients with STEMI in the Australian Victorian Cardiac Outcomes Registry (VCOR) received UFH pretreatment (6). Observational studies in Northern Europe, Scotland, and the Netherlands, however, documented UFH pretreatment rates of 40–50% in patients with STEMI (4, 17, 18). This variance reflects important structural differences and may help to explain the differences in observed outcomes (Box 1).

Box. Impact on daily practice.

Resuscitated patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) and those on oral anticoagulants were less frequently pretreated with unfractionated heparin (UFH) before percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI).

The pretreatment was not associated with increased rates of access-site bleeding. In-hospital mortality was lower in non-resuscitated patients with pretreatment. In contrast, survival was worse in resuscitated patients with pretreatment. The main driver of mortality in this vulnerable group of patients was likely the resuscitation event itself rather than the pretreatment with UFH. Infarction size—measured by the peak level of creatine kinase (CK)—tended to be consistently lower in pretreated patients, with the exception of one subgroup. In patients with STEMI and prior oral anticoagulants, peak CK was higher among those with pretreatment. However, limitations here were small sample size and variance. Alternatives to the administration of UFH, including no pretreatment or the use of other anticoagulants, should be evaluated in future randomized clinical trials.

The IRA flow before PCI is a well explored independent prognostic factor following myocardial infarction (19) and has been used as a primary outcome in multiple analyses of UFH pretreatment in STEMI (4–6, 17, 18, 20, 21). IRA flow prior to PCI was consistently more favorable in pretreated patients (4–6, 17, 18, 20, 21).

Reduced IRA flow after PCI is associated with a poorer prognosis following myocardial infarction (22). Little is known about whether and how UFH pretreatment in STEMI interacts with slow-flow or no-reflow (TIMI flow < 3) after PCI. In a non-controlled small case series reported by Chung et al., UFH pretreatment resulted in a higher rate of TIMI 3 flow following PCI (complete perfusion of the IRA) than in patients who did not receive pretreatment (93 vs. 81%) (20). In contrast, Zijlstra et al. did not detect differences in IRA patency following PCI on unadjusted analysis of patients with either early in-hospital or delayed UFH pretreatment (TIMI = 3: 92% versus 90%) (17). This is in line with the adjusted observations in our registry study after PSM analysis and considering the characteristic “resuscitation”. The mechanisms by which UFH pretreatment may impact on slow-flow or no-reflow remain speculative. They may lower the thrombotic burden and thus improve IRA patency following UFH pretreatment (4, 20). However, the underlying pathology (plaque erosion, plaque rupture), adjunctive antithrombotic treatment, lesion characteristics, lesion preparation, and stent strategy are other potential drivers. The role of UFH pretreatment and its mechanisms of action require further prospective investigation with adjustment for these influences.

UFH pretreatment was found not to reduce in-hospital mortality in the vast majority of previous studies, most of which reported 30-day mortality (4–6, 17, 20). Only in two of these non-randomized observational studies was adjustment by matching performed (5, 6). To date, only two other non-controlled case series have shown a mortality benefit for UFH-pretreated patients, but there were serious imbalances (e.g., in the prevalence of cardiogenic shock) between the cohorts (18, 21). In the present analysis, the OR for in-hospital mortality tended to be lower in pretreated patients who had been resuscitated, both with and without OAC. The CI were wide, however, probably indicating either variance or a lack of statistical power. Analysis larger registries might add value in this respect. In the group of resuscitated patients and in the main PSM analysis—in which around 30% of patients were resuscitated—the OR was higher for pretreatment with UFH. We hypothesize that this result may be driven by resuscitation itself as a confounder for survival. Prospective validation of this hypothesis is pending.

Overall, resuscitated patients with STEMI were less likely to receive UFH pretreatment. Compared with patients not requiring resuscitation, they had a 6.0–7.6 times higher in-hospital mortality rate, and a 1.6–1.9-fold rate of reduced IRA flow following PCI. This group of patients had a demonstrably worse prognosis and higher thrombotic burden. These findings are concordant with recent German registry data from FITT-STEMI (23). One might conclude the existence of a paradox: namely, the most vulnerable patients with STEMI are those in whom UFH pretreatment is least frequently administered—as already described in previous analyses (6, 22). We have also observed this deficiency of care in patients with STEMI who have survived cardiac arrest (14). However, the reasons for less frequent administration of UFH to resuscitated persons remain speculative. Potentially, concerns about resuscitation-induced trauma, prioritization of other treatments, and misclassification of ECG findings as non-STEMI may be contributory factors. Prior daily medication with OAC may also have influenced the treating physicians’ judgment. We have previously demonstrated in a scenario-based survey among German emergency physicians that OAC decrease the rate of UFH pretreatment in STEMI (13). Correspondingly, the present registry study showed a higher rate of OAC in the group without pretreatment (34.8% versus 11.1%). The withholding of UFH pretreatment in orally anticoagulated patients with STEMI has been described before, but in those analyses only 2.2–3.0% of patients were taking OAC (4, 6, 14). In summary, the reasons for the individual judgement remain uncertain in retrospective analysis and require further investigation.

The CK level is regularly recorded in KIM and correlates with infarct size (12). However, measurements were performed at longer intervals in KIM than in the studies cited. Consequently, the peak level may have been underestimated in the present research.

So far only one other study investigating UFH pretreatment in STEMI has reported CK data (20). The authors observed no difference in CK levels between patients with and without pretreatment and concluded a comparable infarct size (20). The present study showed consistently lower peak CK levels after UFH pretreatment, with the sole exception of the subgroup of patients with OAC, among whom peak CK was lower in those without pretreatment. However, peak CK was much lower in the subgroup of all patients with OAC than in the other subgroups. This implies the possible existence of unmeasured bias in this subgroup.

Neither the present study nor prior studies with broadly defined bleeding outcomes found relevant differences detected significant differences between patients with STEMI who received pretreatment and those who did not (4–6, 17, 20, 21). Particularly, access-site bleeding was rare overall in the present analysis. Paradoxically, patients without administration of heparin had higher access-site bleeding rates. The reasons for this also remain speculative, but the selected access site (radial versus femoral, not frequently registered in KIM) and the use of other antithrombotic substances may have contributed. The HEAP trial showed that in patients with STEMI even a higher dose of UFH before treatment (300 units per kilogram body weight) does not result in more bleeding complications than alternative strategies (no UFH or 5000 units of heparin) (24). This might be related to the advantageous controllability of UFH by monitoring the activated clotting time and the possibility of antagonization.

In summary, pretreatment with UFH is not associated with significant potential harm considering the low prevalence of bleeding events.

Limitations

The KIM registry is based on prespecified patient characteristics. For example, data on cardiovascular risk factors or chronic diseases prior to STEMI were not documented. PSM was performed to adjust for the resulting confounding bias in the best possible way. Moreover, the reasons for deciding against the “usual UFH pretreatment” could not be clarified in a retrospective registry analysis. A further limitation is that UFH dose and the time from administration to cardiac catheterization and were not documented. This implies performance bias.

Increased bleeding complications are a potential adverse consequence of UFH treatment. However, the registry and data structure permitted only the assessment of access-site bleeding. The real bleeding event rate was therefore underestimated. The registry does not record other strategies for anticoagulant treatment—including the administration of glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors—that might have the risk of both bleeding and ischemia. Moreover, heparin-induced thrombocytopenia was not documented.

Furthermore, the infarction network KIM exists in a metropolitan setting. These findings are not immediately applicable to rural areas with presumably longer transportation times and thus extended ischemic intervals. In such settings, UFH pretreatment before hospital admission might be beneficial.

Conclusion

With regard to the chosen safety and efficacy outcomes, the results of assessment of UFH pretreatment versus no pretreatment in patients with STEMI were robust in all of the selected adjusted PSM analyses. In the absence of higher quality evidence, the risks and benefits of UFH pretreatment in STEMI should be weighed up individually. Future randomized controlled trials should evaluate strategies involving no pretreatment or alternative antithrombotic options.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank the patients and the participating physicians. We are grateful to Tim Becker, Khalid Salem, and Greta Sommer for data extraction and to Petra Daniels for her unflagging commitment to KIM.

Funding

The KIM registry is funded by the Elisabeth and Rudolf Hirsch Trust.

Data availability statement

The data are available upon reasonable request from the authors.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

SMM has received travel expenses from Bayer Vital AG.

SH has received travel expenses from Eli Lilly and research grants from the German Heart Foundation.

JMS has received research grants from Boston Scientific, Edwards Lifesciences and Medtronic. He was proctor for Medtronic and Boston Scientific, and is a member of the advisory boards of Abbott, Abiomed, Boston Scientific, Boehringer Ingelheim and Medtronic. He has received lecture fees or travel expenses from Abbott, Abiomed, Astra Zeneca, Bayer, Boehringer Ingelheim, Boston Scientific, Bristol Myers Squibb, Edwards Lifesciences, Medtronic, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Pfizer, Shockwave Medical, and Zoll

SB has received lecture fees from Abbott, Edwards, AstraZeneca and JenaValve as well as research grants from Abbott and AstraZeneca

The remaining authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.Byrne RA, Rossello X, Coughlan JJ, et al. 2023 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute coronary syndromes. Eur Heart J. 2023;44:3720–3826. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehad191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ibanez B, James S, Agewall S, et al. 2017 ESC Guidelines for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation: The Task Force for the management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) Eur Heart J. 2018;39:119–177. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehx393. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.O‘Gara PT, Kushner FG, Ascheim DD, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines. Circulation. 2013;127 doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182742cf6. e362-425. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Karlsson S, Andell P, Mohammad MA, et al. Editor‘s Choice- Heparin pre-treatment in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction and the risk of intracoronary thrombus and total vessel occlusion. Insights from the TASTE trial. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2019;8:15–23. doi: 10.1177/2048872617727723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Emilsson OL, Bergman S, Mohammad MA, et al. Pretreatment with heparin in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction: a report from the Swedish Coronary Angiography and Angioplasty Registry (SCAAR) EuroIntervention. 2022;18:709–718. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-D-22-00432. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bloom JE, Andrew E, Nehme Z, et al. Pre-hospital heparin use for ST-elevation myocardial infarction is safe and improves angiographic outcomes. Eur Heart J Acute Cardiovasc Care. 2021;10:1140–1147. doi: 10.1093/ehjacc/zuab032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Macherey S, Meertens MM, Adler C, et al. Impact of respiratory infectious epidemics on STEMI incidence and care. Sci Rep. 2021;11 doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-02480-z. 23066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pfister R, Lee S, Kuhr K, et al. Impact of the type of first medical contact within a guideline-conform ST-elevation myocardial infarction network: a prospective observational registry study. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0156769. e0156769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Flesch M, Hagemeister J, Berger HJ, et al. Implementation of guidelines for the treatment of acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the Cologne Infarction Model Registry. Circ Cardiovasc Interv. 2008;1:95–102. doi: 10.1161/CIRCINTERVENTIONS.108.768176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hamm CW, Schneck E, Buerke M, et al. Empfehlungen zur prähospitalen Behandlung des akuten Koronarsyndroms bei Patienten unter Dauertherapie mit neuen oralen Antikoagulanzien (NOAKs) Der Kardiologe. 2021;15:32–37. doi: 10.1007/s00101-021-00943-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.TIMI Study Group. The thrombolysis in myocardial infarction (TIMI) trial. Phase I findings. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:932–936. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198504043121437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Turer AT, Mahaffey KW, Gallup D, et al. Enzyme estimates of infarct size correlate with functional and clinical outcomes in the setting of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction. Curr Control Trials Cardiovasc Med. 2005;6:12. doi: 10.1186/1468-6708-6-12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Macherey-Meyer S, Braumann S, Heyne S, et al. [Preclinical loading in patients with acute chest pain and acute coronary syndrome—PRELOAD survey] Med Klin Intensivmed Notfmed. 2024;119:529–537. doi: 10.1007/s00063-023-01087-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Macherey-Meyer S, Heyne S, Meertens MM, et al. Outcome of out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients stratified by pre-clinical loading with Aspirin and Heparin: a retrospective cohort analysis. J Clin Med. 2023;12 doi: 10.3390/jcm12113817. 3817. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Montalescot G, Zeymer U, Silvain J, et al. Intravenous enoxaparin or unfractionated heparin in primary percutaneous coronary intervention for ST-elevation myocardial infarction: the international randomised open-label ATOLL trial. Lancet. 2011;378:693–703. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60876-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Collet JP, Zeitouni M. Heparin pretreatment in STEMI: is earlier always better? EuroIntervention. 2022;18:697–699. doi: 10.4244/EIJ-E-22-00035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zijlstra F, Ernst N, de Boer MJ, et al. Influence of prehospital administration of aspirin and heparin on initial patency of the infarct-related artery in patients with acute ST elevation myocardial infarction. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2002;39:1733–1737. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(02)01856-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.McGinley C, Mordi IR, Kell P, et al. Prehospital administration of unfractionated Heparin in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction is associated with improved long-term survival. J Cardiovasc Pharmacol. 2020;76:159–163. doi: 10.1097/FJC.0000000000000865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stone GW, Cox D, Garcia E, et al. Normal flow (TIMI-3) before mechanical reperfusion therapy is an independent determinant of survival in acute myocardial infarction: analysis from the primary angioplasty in myocardial infarction trials. Circulation. 2001;104:636–641. doi: 10.1161/hc3101.093701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chung WY, Han MJ, Cho YS, et al. Effects of the early administration of heparin in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction treated by primary angioplasty. Circ J. 2007;71:862–867. doi: 10.1253/circj.71.862. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Giralt T, Carrillo X, Rodriguez-Leor O, et al. Time-dependent effects of unfractionated heparin in patients with ST-elevation myocardial infarction transferred for primary angioplasty. Int J Cardiol. 2015;198:70–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ijcard.2015.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kammler J, Kypta A, Hofmann R, et al. TIMI 3 flow after primary angioplasty is an important predictor for outcome in patients with acute myocardial infarction. Clin Res Cardiol. 2009;98:165–170. doi: 10.1007/s00392-008-0735-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Scholz P, Friede T, Scholz KH, Grabmaier U, Meyer T, Seidler T. Pre-hospital heparin is not associated with infarct vessel patency and mortality in ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction patients with out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Clin Res Cardiol. 2024 doi: 10.1007/s00392-024-02499-y. DOI: 10.1007/s00392-024-02499-y. Online ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liem A, Zijlstra F, Ottervanger JP, et al. High dose heparin as pretreatment for primary angioplasty in acute myocardial infarction: the Heparin in Early Patency (HEAP) randomized trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2000;35:600–604. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(99)00597-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]