Abstract

The development and progression of liver cirrhosis are considerably influenced by immune processes, with CD8 + T cells playing a key role. Notably, cytokines can activate bystander CD38 + HLA-DR + CD8 + T cells without the need for T cell receptor (TCR) stimulation. However, their role in liver fibrosis remains controversial. This study aimed to investigate the pathological role of CD38 + HLA-DR + CD8 + T cells in cirrhosis progression and explore the mechanisms that regulate their functions. Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were extracted from patients with cirrhosis and healthy donors, and the ratio of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells was assessed through flow cytometry. The relationship between the prevalence of these cells and certain clinical indicators was investigated. Additionally, CD8+ T cells from healthy donors were used to examine the impact of cytokine IL-15 on CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells, utilizing flow cytometry and in vitro cytotoxicity assays. Finally, the signaling pathways involved in IL-15 activation of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells were examined in vitro. The proportion of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells was significantly increased in patients with cirrhosis compared to healthy donors and exhibited a strong correlation with disease severity, hepatic damage, and inflammation in cirrhosis. IL-15-stimulated CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells from healthy donors demonstrated proliferation and overexpression of cytotoxic molecules, exhibiting NKG2D- and FasL-dependent innate-like cytotoxicity without TCR activation. Notably, IL-15 did not alter the mitochondrial function of these cells. The JAK/STAT5 and PI3K/mTOR pathways were found to play a critical role in IL-15-induced innate-like cytotoxicity. These findings suggested that CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells from patients with cirrhosis contribute to immune-mediated liver injury. Furthermore, the JAK/STAT5 and PI3K/mTOR pathways were essential for IL-15-induced activation of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells, which expressed NKG2D and FasL, demonstrating innate cytotoxicity independent of TCR engagement.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-02693-6.

Keywords: Liver cirrhosis, CD8+ T cell, TCR, Bystander activation, IL-15

Subject terms: Adaptive immunity, Cytokines

Introduction

Cirrhosis poses a major health burden in many countries worldwide. In 2017, there were 10.6 million cases of decompensated cirrhosis and 112 million cases of compensated cirrhosis globally1. Patients with compensated cirrhosis had a fivefold increased risk of mortality, whereas those with decompensated cirrhosis exhibited a tenfold increased risk compared to the general population2. About 80–90% of patients with cirrhosis develop hepatocellular carcinoma, making cirrhosis a crucial risk factor for this type of cancer2. Liver cirrhosis arises from multiple etiologies, including obesity, non-alcoholic fatty liver disease, excessive alcohol intake, hepatitis infections, autoimmune disorders, cholestatic illnesses, and iron or copper overload3. The progression of the disease is characterized by progressive portal hypertension, systemic inflammation, and hepatic damage, which collectively drive its clinical outcomes3.

Immune pathways are crucial in the development and progression of liver cirrhosis in cirrhotic individuals, with CD8+ T cells playing a key role. During the progression of liver injury in cirrhosis, compromised hepatocytes rapidly produce inflammatory mediators, including chemokines and cytokines, which recruit leukocytes to the injury site. Neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages serve as the initial responders to eliminate dead cells and debris, while CD8+ T cells play a crucial role in the subsequent immune response4. However, the role of CD8+ T cells is complex and somewhat contradictory, possibly due to the coexistence of auto-aggressive and protective T cell immunity. For example, CD8+ T cells can promote liver injury and contribute to hepatocyte damage5. Furthermore, in a mouse model of obesity-induced NASH, CD8+ T cells were found to activate hepatic stellate cells (HSCs), thereby promoting the progression of liver cirrhosis6. In contrast, another study indicated that CD8+ T cells can recruit HSCs through a CCR5-dependent mechanism, making activated HSCs susceptible to apoptosis and promoting fibrosis resolution7. These contradictory findings suggest that various subsets of CD8+ T cells play a unique and potentially antagonistic roles in cirrhosis progression and resolution.

Immune memory, a characteristic of adaptive immunity, occurs after infection or vaccination and persists in the organism to provide specific protection against subsequent exposures to the same pathogen. Memory T cells are a key component of this immune memory. In addition to their specific adaptive response upon recognizing their cognate antigen, these cells could also mount an innate-like, antigen-independent response to infections, a phenomenon known as bystander activation8. Recent findings reveal that CD8+T cells having the activation phenotype CD38+HLA-DR+ exhibit bystander activation9,10. These T cells are stimulated not only by cytokines (including Type I interferons, IL-18, and IL-15) but also exhibit the notable ability to induce cytotoxicity independently of T cell receptor (TCR) activation11.

Bystander-activated CD8+ T cells can be either protective or cause injury to the host during infection. For example, local bystander activation of CD8+ memory T cells promoted a swift and efficient innate-like response to infection in mucosal tissue, offering extensive protection against bacterial infection in a helminth infection model12,13. However, bystander-activated CD8+ T cells were linked to cytotoxic effects on hantavirus-infected umbilical vein endothelial cells14. In patients with cirrhosis, CD8+ T cell subsets in ascites displayed a chronically activated bystander pattern, which was associated with disease severity15. However, the specific role of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells in the pathogenesis of liver cirrhosis is yet to be clarified.

This study investigated the functional status of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells in patients with cirrhosis. Clinical investigations demonstrated that CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells were considerably associated with disease severity, liver damage, and inflammation in cirrhosis. IL-15 stimulated the activation of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells, which expressed NKG2D and FasL, demonstrating TCR-independent innate cytotoxicity. Importantly, IL-15 did not affect the mitochondrial function of these cells. Furthermore, we noted that the JAK/STAT5 and PI3K/mTOR pathways greatly contributed to the IL-15-induced innate-like cytotoxicity of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. Collectively, the JAK/STAT5 and PI3K/mTOR pathways played a crucial role in IL-15-induced activation of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells, which exhibited innate cytotoxic-like activity independent of TCR but reliant on NKG2D and FasL, contributing to liver injury in cirrhosis.

Materials

Patient recruitment

This study enrolled 40 participants from the cirrhosis treatment center of the Second Hospital of Nanjing between June 2022 and June 2023. The participants included 30 patients with liver cirrhosis from various etiologies and 10 healthy donors. Among the 30 enrolled patients with cirrhosis, the etiologies of cirrhosis included hepatitis B (n = 14), autoimmune hepatitis (n = 2), primary biliary cholangitis (n = 1), alcoholic liver disease (n = 1), hepatitis C (n = 2), non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (n = 2), and unknown causes (n = 7). Patients with liver cirrhosis were diagnosed using histological, clinical, and imaging criteria. Clinical data were collected after enrollment (Table 1), and peripheral blood specimens were collected from both groups. Ethical approval was obtained from the medical ethics board of the Second Hospital of Nanjing, and all participants provided written informed consent in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). All study procedures were performed in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Table 1.

Demographics and baseline clinical characteristics of healthy donors and liver cirrhosis.

| Healthy donors (n = 10) | Liver cirrhosis (n = 30) |

P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age(years) | 57.00(52.75, 60.00) | 58.50(53.75, 67.50) | > 0.05 |

| Sex(Male/ total (n)) | 8/10 | 22/30 | > 0.05 |

| MELD score | 10.00 (8.00, 14.25) | ||

| Child-Pugh score | 7.00 (5.00, 8.25) | ||

| AST(U/L) | 36.15 (25.93, 53.05) | ||

| ALT(U/L) | 27.30 (20.75, 47.25) | ||

| ALP(U/L) | 109.00 (86.50, 136.75) | ||

| CHE(U/L) |

3127.50 (2626.25, 5090.00) |

||

| γ-GT(U/L) | 62.00 (24.75, 90.25) | ||

| TBIL(µmol/L) | 20.80 (14.05, 35.80) | ||

| ALB (g/L) | 33.60 (29.02, 40.55) | ||

| Leukocytes count (×109 /L) | 4.00 (2.73, 6.04) | ||

| Lymphocytes (%) | 21.90 (17.75, 32.18) | ||

| Monocytes (%) | 7.65(6.55, 9.18) | ||

| Neutrophils (%) | 67.75(55.75, 71.73) | ||

| Basophils (%) | 0.40(0.20, 0.80) |

1 Data are presented as median values (1st − 3rd quartile).2 n, number of subjects; AST, aspartate transaminase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; ALP, alkaline phosphatase; CHE, cholinesterase; γ-GT, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase; TBIL, total bilirubin; ALB, albumin.

Isolation of peripheral blood mononuclear cells

Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) were extracted from fresh blood using a Ficoll gradient centrifugation technique with a lymphocyte isolation solution (TBD, Tianjin, China), in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines.

Flow cytometry

PBMCs were analyzed using flow cytometry for cell surface phenotyping and intracellular staining. Cell surface staining was performed using the following antibodies: LIVE/DEAD Fixable Dead Cell Stain Kits, anti-CD3-PerCP/APC-H7, aanti-CD8-PE-Cy7/APC-Cy7, anti-CD38-APC/BV605, anti-HLA-DR-V450/Alexa Fluor 700, anti-NKG2D-PE-Cy7, anti-NKP30-BV711, anti-TIGIT-PE, anti-PD-1-APC-Cy7, anti-Ki-67-PE, and anti-FasL-PE. Intracellular staining was performed using the following antibodies: anti-perforin-FITC, anti-granzyme B-PE. All the reagents were purchased from BD Biosciences (New York, USA) or Thermo (Waltham, MA, USA). For surface labeling, 1 × 106 cells were treated with antibodies targeting surface markers at 4 °C for 30 min and subsequently washed twice with PBS (pH = 7.4). For intracellular labeling of perforin and granzyme B, 1 × 106 cells were fixed and permeabilized utilizing a fixation and permeabilization solution (BD Biosciences, New York, USA), in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Cell apoptosis was assessed using the Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Assay Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). All cells were assessed using a FACS Aria III flow cytometer. The data were analyzed using Flow Jo V10 software (Flow Jo LLC).

Mice

Male C57BL/6 mice, aged 6 to 8 weeks and approximately 20 g in weight, were supplied by Jiangsu Qinglongshan Biotechnology Co. LTD (Danyang, Jiangsu, China). The mice were accommodated in a pathogen-free setting with an ambient temperature of approximately 26 °C, humidity regulated between 40 and 70%, and a 12 h light/dark cycle. Sterile water and feed were available. For the experimental hepatic fibrosis model, carbon tetrachloride (CCL4) (10% in corn oil, 10 mL/kg) was administered intraperitoneally to C57BL/6 mice twice weekly for a duration of 12 weeks. The control group was administered oil injections. The experimental groups were as follows: (1) control group, n = 4; (2) CCL4 group, n = 4. Following anesthesia by isoflurane, the mice were immobilized, and blood was extracted from the retro-orbital sinus via a capillary tube. The mice were then euthanized by cervical dislocation. Liver and blood specimens from mice were obtained and subjected to histology, gene expression, and serological analyses. All experimental protocols were approved by the Nanjing University of Chinese Medicine. All methods for animal study were performed in accordance with the relevant guidelines and regulations. The study was reported in accordance with the ARRIVE guidelines.

Extraction of hepatic mononuclear cells

Mice liver tissue samples were sectioned into small pieces, approximately 1 mm3 in size. Then, the tissues were digested with collagenase I (Thermo, MA, USA) at 37 ℃ for 2 h. The resultant liver slurry was filtered via 40 μm filters (BD Biosciences, New York, USA) to isolate hepatic mononuclear cells. These cells were subsequently centrifuged at 400 g for 10 min. The separated cells were subjected to two washes with PBS (pH 7.4) (Invitrogen, San Diego, USA) and subsequently resuspended in PBS supplemented with 1% fetal bovine serum (Gibco, New York, USA).

Histological evaluation

Mice liver tissues were sectioned and preserved in 10% paraformaldehyde for 48 h. The tissues were subsequently fixed in paraffin wax, and slices (about 5 μm thick) were stained for liver histology using hematoxylin and eosin at room temperature. Fibrosis was assessed by Masson trichrome staining. Masson trichrome kit (Baso, Zhuhai, China) was used at room temperature according to the manufacturer’s protocols. The sections were sealed with neutral gum before observation with a light microscope.

Western blot

Following the manufacturer’s instructions, proteins were extracted from mouse liver tissue using cell lysis buffer (Beyotime, Shanghai, China), supplemented with 100 mM PMSF (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) and a protease inhibitor cocktail (MedChemExpress, NJ, USA). A BCA protein assay kit (Epizyme Biotech, Shanghai, China) was used to determine each sample’s protein concentration. A 12% SDS-PAGE gel was used to separate the components, which were then electrotransferred onto PVDF membranes with a 0.22 μm pore size (Millipore, MA, USA). The PVDF membranes were blocked using 5% non-fat milk dissolved in TBST for 2 h. Incubation with primary antibodies, such as the anti-IL-15 antibody (Abcam, Cambridge, UK), was performed overnight at 4 °C. The control was GAPDH rabbit monoclonal antibody (ABclonal, Hubei, China). Following three washes with TBST, the membranes were incubated with Goat Anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) (HRP) secondary antibody (Engibody, DE, USA) in blocking solution at room temperature for 2 h. Following three washes with TBST, a chemiluminescent substrate ECL reagent kit (Beyotime, Shanghai, China) was employed to assess the band.

ELISA analysis

Peripheral blood was centrifuged for 10 min at 3000 rpm to extract serum. The levels of IL-15 were detected by sandwich ELISA following the manufacturer’s protocol, and concentrations were determined from the standard curve obtained with replicate samples. The human IL-15 ELISA Kit was purchased from MultiSciences (Hangzhou, China).

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from mouse liver tissues using the FastPure Cell/Tissue Total RNA Isolation Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China), and the RNA concentration in each sample was measured. Then, a HiScript II Q Select RT SuperMix for qPCR (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) was used to reverse transcribe RNA into cDNA. The Applied Biosystems 7500 Fast PCR Instrument (Thermo, MA, USA) was used to amplify the cDNA for 40 cycles using the ChamQ SYBR qPCR Master Mix (Vazyme, Nanjing, China). The housekeeping gene, GAPDH, was used to normalize IL-15 expression. Every experiment was conducted in triplicate and at least three times. The sequences of primers used were as follows: IL-15, forward: 5’-AAACAGAGGCCAACTGGATAG-3’, reverse: 5’-CTTTGCAACTGGGATGAAAGTC-3’; GAPDH, forward: 5’- GGCAAATTCAACGGCACAGT − 3’, reverse: 5’-GGCCTCACCCCATTTGATGT-3’. Gene expression levels were quantified using the 2 −△△Ct method, employing GAPDH as the reference gene.

IL-15 induces proliferation of CD8+ T cells

Peripheral blood CD38−HLA-DR−CD8+ T cells from healthy human PBMCs were sorted using FACS Aria III flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, New York, USA) at a purity level of > 90%. Purified peripheral blood CD38−HLA-DR−CD8+ T cells were then stimulated with IL-15 (20 ng/mL) (Thermo, MA, USA) for 72 h. The expression of CD38 and HLA-DR on CD8+ T cells was assessed by flow cytometry.

Following the manufacturer’s guidelines, CD8+ T cells (1 × 106) were labeled with CFSE using the CellTrace Cell Proliferation Kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, USA), and subsequently stimulated with or without IL-15 (20 ng/mL) (Thermo, MA, USA) for 72 h. The proliferation levels of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells and CD38−HLA-DR−CD8+ T cells were analyzed by flow cytometry.

Cytotoxicity testing

K562 cells were purchased from Shanghai Zhong Qiao Xin Zhou Biotechnology Co., Ltd. These cells were labeled with CFSE using the CellTrace Cell Proliferation Kit (Invitrogen, San Diego, USA), in accordance with the manufacturer’s guidelines. CD8+ T cells (1 × 106) from healthy donors were pre-treated with inhibitors including STAT5 inhibitor pimozide, MEK inhibitor PD98059, PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or mTOR inhibitor PP242 (MedChemExpress, NJ, USA) and stimulated with IL-15 (20 ng/mL) (Thermo, MA, USA) for 72 h. CD8+ T cells were subsequently co-cultured with CFSE-labeled K562 cells at a 10:1 effector-to-target (E: T) ratio for 6 h, and cytotoxicity against K562 cells was assessed. Cytotoxicity was assessed using the Annexin V-FITC/PI Apoptosis Detection Kit (Vazyme, Nanjing, China) following the manufacturer’s instructions.

Analysis of mitochondrial function

Mitochondrial quantity and mitochondrial reactive oxygen species (ROS) generation were assessed using MitoTracker Green and MitoSOX Red (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA), respectively. Briefly, cells were initially surface stained for 30 min at 4 °C. Following this, cells were incubated with MitoTracker Green or MitoSOX Red for 30 min at 37 °C and 5% CO2, in accordance with the manufacturers’ instructions. Subsequently, flow cytometry was conducted using a FACS Aria III flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, New York, USA) for measurement.

Phosphorylation assay of the IL-15 signaling pathway

To assess phosphorylation, 1 × 106 PBMCs were initially incubated with the surface marker antibodies at 4 °C for 30 min. Cells were subsequently fixed with Fixation Buffer for 10 min at 37 °C and permeabilized by the addition of Perm Buffer III for 30 min on ice. After washing, cells were stained with anti-Stat5-RB705, anti-ERK1/2-BV421 or anti-mTOR-PE and incubated at room temperature for 60 min. All the reagents were purchased from BD Biosciences (New York, USA). Flow cytometry was conducted using a FACS Aria III flow cytometer (BD Biosciences, New York, USA), and data were analyzed using FlowJo software (FlowJo, LLC).

Analysis of molecule expression on CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells following treatment with signal pathway inhibitors

CD8+ T cells (1 × 106) from healthy donors were pre-treated with STAT5 inhibitor pimozide, PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or mTOR inhibitor PP242, followed by IL-15 (20 ng/mL) (Thermo, MA, USA) stimulation for the next 72 h. All the inhibitors were obtained from MedChemExpress (NJ, USA). The expression of NKG2D, FasL, perforin, and granzyme B in the CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells was analyzed by flow cytometry.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted on GraphPad Prism 9. The Mann-Whitney U-test, one-way ANOVA, Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test, or paired t-test were employed for the analyses. All data were presented as the mean ± standard error of the mean. The Spearman test was employed for correlation analysis. A p-value below 0.05 was deemed statistically significant.

Result

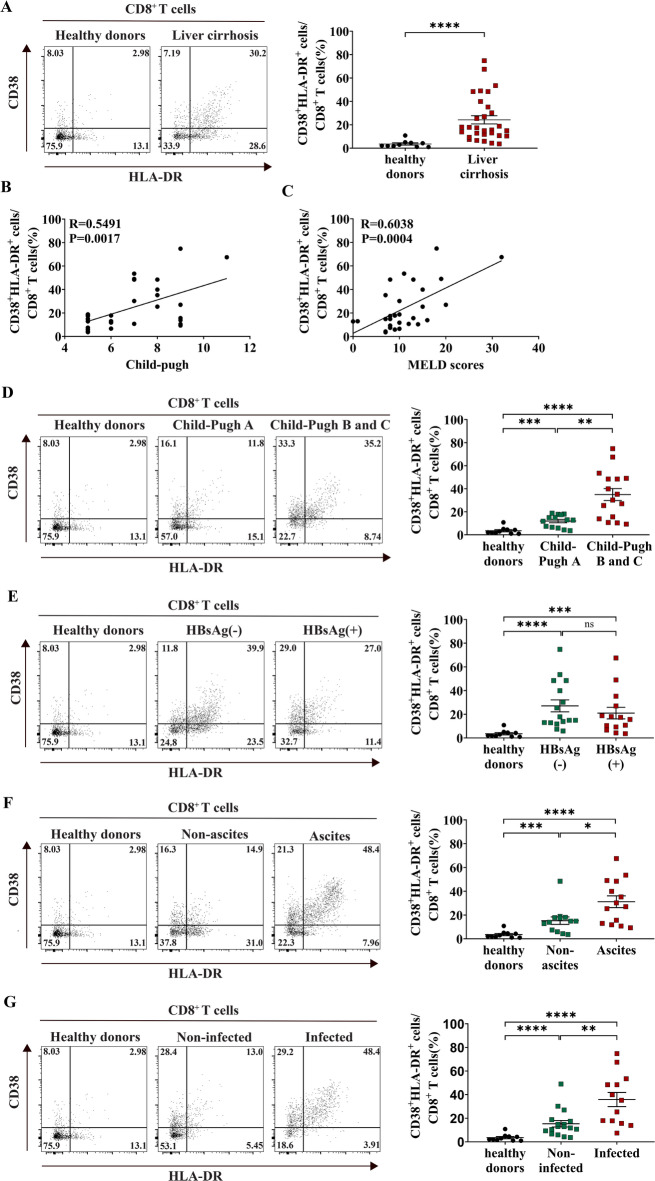

CD38+HLA-DR+ expression on CD8+ T cells is considerably associated with disease severity in cirrhosis

Research on the expression of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells in cirrhosis is relatively scarce. Therefore, we examined the expression of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells in patients with cirrhosis and healthy donors. We found that CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells were significantly increased in patients with cirrhosis from various causes compared to healthy donors (healthy donors vs. liver cirrhosis: 3.53% vs. 24.21%) (Fig. 1A). Figure S1 illustrates the gating strategy for the flow cytometric analysis of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. A positive link was noted between the proportion of these cells and the Child-Pugh and MELD scores, indicating an association with disease severity (Fig. 1B, C). Notably, the percentage of these cells was markedly elevated in patients classified as Child-Pugh B and C compared to those in class A, with both groups exceeding the levels observed in healthy donors (healthy donors vs. Child-Pugh class A vs. Child-Pugh class B and C: 3.53% vs. 11.94% vs. 34.95%) (Fig. 1D). However, no significant difference was noted in the proportion of these cells between hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg)-negative and HBsAg-positive patients, indicating that HBV infection status did not affect the proportion of these cells in patients with liver cirrhosis (healthy donors vs. HBsAg-negative vs. HBsAg-positive: 3.53% vs. 27.06% vs. 20.96%) (Fig. 1E).

Fig. 1.

Correlation of the expression of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells with cirrhosis disease severity. (A) Representative FACS plots showing the expression CD38+HLA-DR+ on CD8+ T cells from healthy donors and liver cirrhosis. The proportion of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells between healthy donors (n = 10) and patients with liver cirrhosis (n = 30) are shown. (B-C) Correlation analysis of the proportion of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells in patients with cirrhosis (n = 30) with Child-Pugh score and MELD score. (D) Comparison of the percentage of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells between healthy donors (n = 10) and patients with cirrhosis classified as Child-Pugh class A (n = 14), B, and C (n = 16). (E) Comparison of the percentage of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells among healthy donors (n = 10), HBsAg-negative patients with cirrhosis (n = 16), and HBsAg-positive patients with cirrhosis (n = 14). (F) Comparison of the percentage of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells among healthy donors (n = 10), patients with cirrhosis without (n = 13), and with ascites (n = 14). (G) Comparison of the percentage of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells among healthy donors (n = 10), patients with cirrhosis without (n = 17), and with infection (n = 13). The Mann-Whitney U-test or one-way ANOVA was used for comparisons between groups. The Spearman test (B-C) was used for correlation analysis. ns, not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

Subsequently, we examined the influence of cirrhosis complications on the expression of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. Table S1 shows the distribution of cirrhosis etiologies among patients with and without ascites, as well as those with and without infections. Fisher’s exact test analysis revealed no statistically significant differences in etiology distribution between patients with and without ascites or between infected and non-infected groups (p > 0.05). The proportion of these cells was considerably higher in individuals with ascites than in those without ascites, and both groups exhibited greater levels than healthy donors (healthy donors vs. without ascites vs. with ascites: 3.53% vs. 15.24% vs. 31.18%) (Fig. 1F). Similarly, individuals with cirrhotic infections demonstrated a markedly elevated proportion of these cells relative to those without infections, with both groups exhibiting greater levels than healthy donors (healthy donors vs. without infection vs. with infection: 3.53% vs. 15.33% vs. 35.83%) (Fig. 1G). Collectively, these findings indicate that CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells are considerably association with disease severity in cirrhosis.

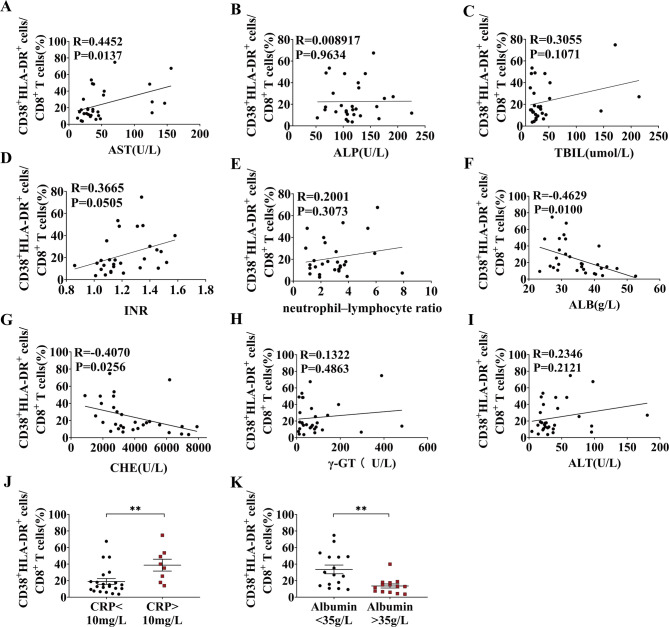

Elevated CD38+HLA-DR+ expression on CD8+ T cells from patients with cirrhosis is associated with liver injury

To examine the correlation between CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells and liver injury, we assessed the relationship between these cells and related clinical data in patients with cirrhosis. Notably, we found a striking positive association between CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells and the liver damage marker aspartate aminotransferase (AST) (Fig. 2A). Albumin (ALB) and cholinesterase (CHE) levels were inversely associated with the proportion of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells, collectively indicating that their expansion is linked to liver injury (Fig. 2F-G). No significant association was identified between this T cell subpopulation and alkaline phosphatase (ALP), total bilirubin (TBil), International Normalized Ratio (INR), and neutrophil-lymphocyte ratio (NLR) (Fig. 2B-E). No associated was found between the percentage of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells and the levels of γ-glutamyl transpeptidase (γ-GT) and alanine transaminase (ALT) (Fig. 2H-I). Furthermore, the percentage of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells was markedly elevated in the abnormal CRP group (CRP > 10 mg/L) relative to the normal CRP group (CRP < 10 mg/L) (Fig. 2J). Similarly, patients exhibiting aberrant albumin levels (ALB < 35 g/L) demonstrated a markedly larger number of these cells in comparison to individuals with normal albumin levels (ALB > 35 g/L) (Fig. 2K). Collectively, CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells demonstrated a significant association with liver injury markers and inflammation in cirrhosis.

Fig. 2.

Correlation of the expression of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells with clinical data in cirrhosis. (A-I) Correlation between the proportion of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells and AST, ALP, TBil, INR, NLR, ALB, CHE, γ-GT, and ALT in patients with cirrhosis, respectively (n = 30). (J) Comparison of the percentage of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells between the CRP normal group (CRP < 10 mg/L, n = 22) and the CRP abnormal group (CRP > 10 mg/L, n = 8). (K) Comparison of the percentage of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells between the albumin abnormal group (ALB < 35 g/L, n = 16) and the albumin normal group (ALB > 35 g/L, n = 14). The Spearman test was used for correlation analysis (A-I). The Mann-Whitney U-test (J, K) was used for comparisons between groups. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

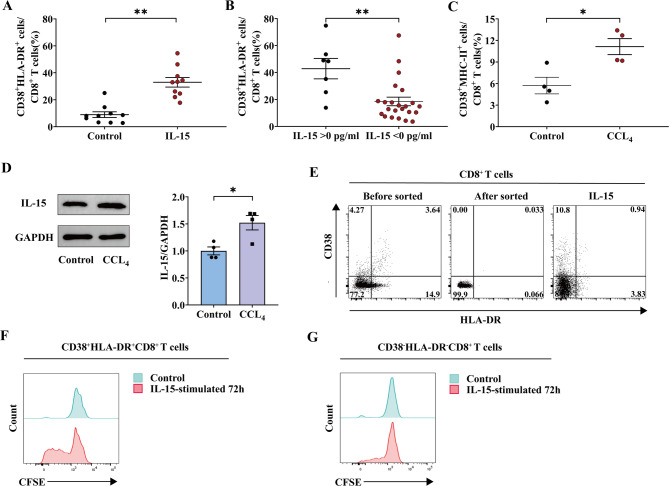

IL-15 induce proliferation and innate-like cytotoxic functions in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells

Our previous studies have shown that IL-15 can enhance the proliferation of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells in vitro16,17. In this study, we obtained fresh CD8+ T cells from different healthy donors and repeated this experiment with or without IL-15 activation. Similarly, there was a marked increase in the fraction of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells following IL-15 stimulation (control vs. IL-15: 8.94% vs. 32.98%) (Fig. 3A). Meanwhile, we assessed IL-15 levels in patients with liver cirrhosis and observed that the percentage of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells was elevated in the cohort with detectable IL-15 concentrations (IL-15 > 0 pg/mL) compared to those without (IL-15 < 0 pg/mL) (IL-15 > 0 pg/mL vs. IL-15 < 0 pg/mL: 42.89% vs. 18.53%) (Fig. 3B). We additionally corroborated these findings in a mouse model of CCL4-induced liver fibrosis (Figure S2). In accordance with our human data, the ratio of CD38+MHC-II+CD8+ T cells (analogous to CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells in mice) and the concentrations of IL-15 in the liver were elevated in the liver fibrosis mouse model (Fig. 3C-D) (Figure S3)10. This suggests that the ratio of CD38+HLA-DR+ on the surface of CD8+ T cells is associated with the stimulation of IL-15 throughout the progression of cirrhosis.

Fig. 3.

Proliferation of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells stimulated by IL-15. (A) CD8+ T cells obtained from healthy donors were incubated for 72 h with or without IL-15 stimulation. Flow cytometry analysis was performed for CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells (n = 10). Control group was not treated with IL-15 stimulation. (B) Comparison of the proportion of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells in the group with a detectable IL-15 concentration (IL-15 > 0 pg/mL, n = 7) versus the group without a detectable IL-15 concentration (IL-15 < 0 pg/mL, n = 23). (C) Comparison of the proportion of CD38+MHC-II+CD8+ T cells from mouse liver tissues in the control group (n = 4) and CCl4 group (n = 4). The control group received corn oil injections. (D) Immunoblot of IL-15 in mice liver tissues between control group (n = 4) and CCl4 group (n = 4). The control group received corn oil injections. (E) Flow cytometry sorted CD38−HLA-DR−CD8+ T cells from PBMCs (n = 4) were cultured with IL-15 (20 ng/mL) for 72 h. (F-G) CFSE-labeled CD8+ T cells from healthy donor PBMCs (n = 8) were cultured with IL-15 (20 ng/mL) for 72 h. The Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test (A) was used for comparisons between groups. The Mann-Whitney U-test (B) was used for comparisons between groups. The Unpaired t-test (C, D) was used for comparisons between groups. ns, not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

To determine which cells were specifically stimulated by IL-15 for proliferation, we sorted CD38−HLA-DR−CD8+ T cells from healthy human PBMCs and stimulated them with IL-15 for 72 h. As shown in Fig. 3E, IL-15 failed to induce the proliferation of CD38−HLA-DR−CD8+ T cells into CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. Additionally, CFSE-labeled CD8+ T cells from healthy donors were stimulated with or without IL-15 for 72 h. We observed that CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells exhibited considerable proliferation in comparison to CD38−HLA-DR−CD8+ T cells (Fig. 3F-G). The results suggest that IL-15 primarily enhances the proliferation of pre-existing CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells.

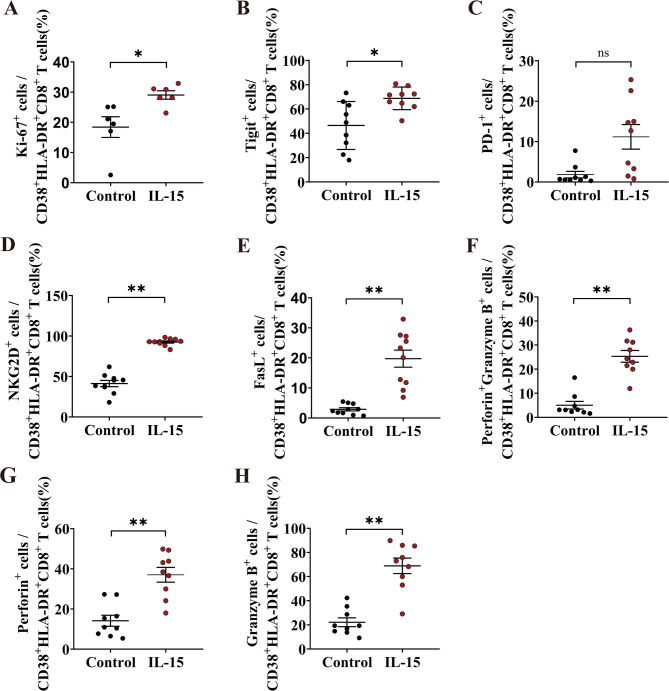

We investigated whether in vitro exposure to cytokine IL-15 would activate and functionally alter CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells from healthy donors in the absence of antigenic stimulation. IL-15 activation led to an increased expression of the proliferation marker Ki-67 in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells (control vs. IL-15: 18.43% vs. 29.07%) (Fig. 4A). Additionally, we observed an upregulation of the immunosuppressive marker TIGIT of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells (control vs. IL-15: 46.48% vs. 68.81%) (Fig. 4B). Despite the absence of a statistically significant increase in PD-1 expression in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells, IL-15 stimulation led to an augmentation in PD-1 expression (control vs. IL-15: 1.83% vs. 11.18%) (Fig. 4C). Subsequently, we examined the effector activity of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells derived from healthy donors subjected to IL-15 exposure. We analyzed CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells for the expression of various NK-activating receptors, specifically NKG2D and FasL, and observed that IL-15 markedly increased the expression levels of these receptors (NKG2D, control vs. IL-15: 41.28% vs. 92.54%) (FasL, control vs. IL-15: 2.87% vs. 19.73%) (Fig. 4D-E). Furthermore, IL-15 markedly enhanced the secretion of perforin+granzyme B+, perforin+ and granzyme B+ in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells (perforin+granzyme B+, control vs. IL-15: 5.04% vs. 25.33%) (perforin+, control vs. IL-15: 14.13% vs. 37.02%) (granzyme B+, control vs. IL-15: 22.2% vs. 68.91%) (Fig. 4F-H). All the representative FACS plots are shown in Figure S4. Collectively, the results suggest that IL-15 played a major role in the activation of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells, leading to their proliferation and the overexpression of cytotoxic molecules.

Fig. 4.

Functional alternations of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells after IL-15 stimulation. CD8+ T cells obtained from healthy donors were incubated for 72 h with or without IL-15 stimulation. Flow cytometry analysis was performed for the expression of surface marker (A) Ki-67 (n = 6), (B) Tigit (n = 9), (C) PD-1(n = 9), (D) NKG2D (n = 10), and (E) FasL (n = 10) in the gate of Live+CD3+CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. Intracellular staining method was used to assess the secretion of (F-H) perforin and Granzyme B (n = 9) in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. The Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test was used for comparisons between groups. Control group was not treated with IL-15 stimulation. ns, not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

CD8+ T cells after IL-15 stimulation exert NKG2D and FasL-dependent innate-like cytotoxic activity

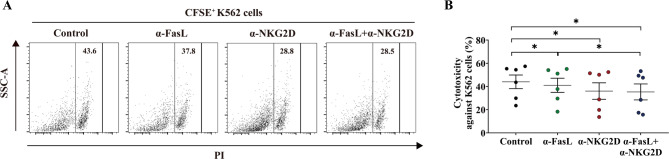

Previous studies have demonstrated that CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells promote innate immune response activities via NKG2D18. Our findings demonstrated that IL-15 not only stimulated the expression of NKG2D on CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells but also increased the expression of FasL. This suggests that FasL, in addition to NKG2D, might contribute to the innate immune functions of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. To explore this, we used CD8+ T cells from healthy donors stimulated with IL-15 for 72 h as effector cells and co-cultured them with CFSE-labeled K562 cells (lacking MHC I molecule expression) as target cells at 10:1 E: T ratio in the presence of either anti-NKG2D antibody, anti-FasL antibody, or both. Figure 5 illustrates that anti-NKG2D and anti-FasL antibodies markedly suppressed the innate-like cytotoxic activity of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells against K562 cells, with the anti-NKG2D antibody demonstrating superior efficacy. Overall, these findings reveal that IL-15-induced CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells exhibit TCR-independent, innate-like cytotoxicity mediated by NKG2D and FasL.

Fig. 5.

NKG2D- and FasL-dependent innate-like cytotoxicity of IL-15-stimulated CD8+ T cells. After 72 h of IL-15 stimulation (20 ng/mL), peripheral blood CD8+ T cells from healthy donors were co-cultured with CFSE-labeled K562 cells at an E: T ratio of 10:1, and cytotoxicity against K562 cells was evaluated in the presence of the indicated antibodies (n = 6). Control group was treated only with IL-15. (A) Representative dot plots shown the expression of PI in the gate of CFSE+. (B) The cytotoxicity against K562 cells (the percentage of PI in the gate of CFSE+) was compared among groups was shown. The Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test (B) was used for comparisons between groups. *p < 0.05.

Functional analysis of mitochondria in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells

In the context of a persistent infection, CD8+ T cells exhibit altered regulation of mitochondrial metabolism19. To explore this, we investigated the impact of mitochondria on the functionality of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. The gating strategy for the flow cytometric analysis of mitochondrial function in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells is shown in Figure S5. No difference in mitochondrial mass (MitoTracker Green) of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells was observed in patients with cirrhosis compared with healthy donors (Fig. 6A). Additionally, we investigated the mitochondrial ROS (MitoSOX) levels in both groups and found no significant difference between the liver cirrhosis group and healthy donors (Fig. 6B). Further, we examined the impact of IL-15 stimulation on mitochondrial activity in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. While mitochondrial mass remained unchanged after IL-15 stimulation, there was a reduction in MitoSOX levels (Fig. 6C-D). Therefore, IL-15 did not significantly affect mitochondrial function in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells.

Fig. 6.

Function of mitochondria in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. (A-B) Flow cytometric analysis of MitoTracker Green and MitoSOX in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells between healthy donors (n = 10) and patients with cirrhosis (n = 22). Representative dot plots and the mean florescence intensity (MFI) of MitoTracker Green and MitoSOX Red are shown. (C-D) CD8+ T cells obtained from healthy donors were incubated for 72 h without or with IL-15 stimulation. Flow cytometry analysis was performed for the MFI of mitochondrial mass (n = 10) and MitoSOX in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells (n = 10). Representative dot plots from a single donor (left) and summary data (right) are presented. The Mann-Whitney U-test (A, B) was used for comparisons between groups. The Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test (C, D) was used for comparisons between groups. Blank group indicate that they did not receive MitoTracker Green or MitoSOX staining. Control group was not treated with IL-15 stimulation. ns, not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

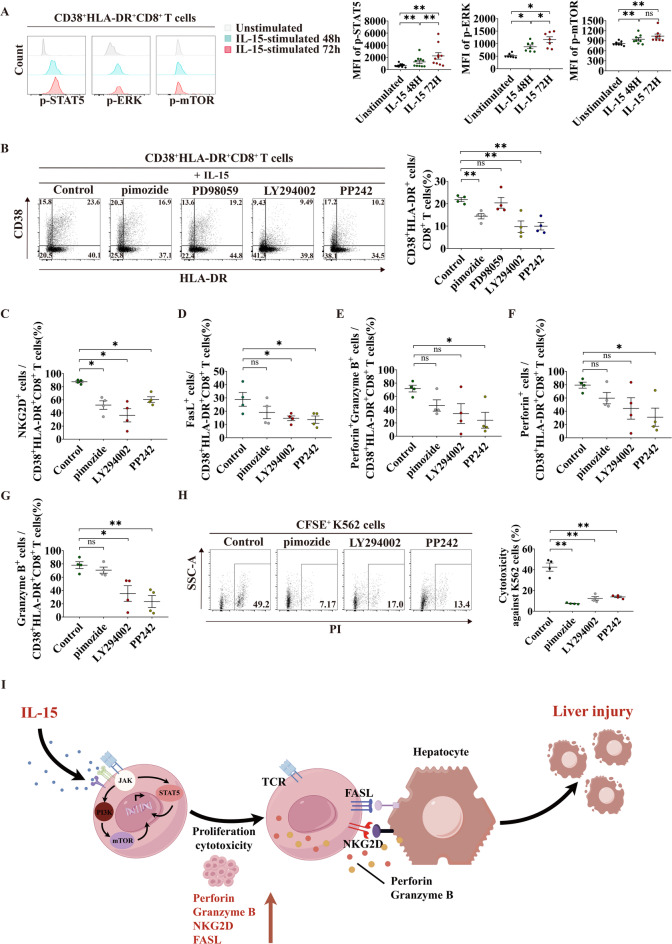

The JAK/STAT5 and PI3K/mTOR pathways play a key role in IL-15-induced innate-like cytotoxicity in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells

IL-15 promotes cellular proliferation and sustenance via many pathways, including JAK/STAT5, Ras/Raf/MEK, and PI3K/mTOR20. Thus, we investigated whether these three signaling pathways play a role in IL-15-induced innate-like cytotoxicity in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. Initially, we observed that IL-15 treatment for 48 h and 72 h enhanced the phosphorylation of signaling proteins such as STAT5, ERK, and mTOR in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells (Fig. 7A). To further investigate which pathway could stimulate CD38+HLA-DR+ expression on CD8 + cells, these cells were pre-treated with STAT5 inhibitor pimozide, MEK inhibitor PD98059, PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or mTOR inhibitor PP242, followed by IL-15 stimulation for the next 72 h. The results showed that the IL-15-induced increase in the proportion of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells was markedly inhibited by pimozide, LY294002, and PP242, but not by PD98059 (Fig. 7B). The results suggest that the JAK/STAT5 and PI3K/mTOR pathways play a role in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells.

Fig. 7.

The signal pathways involved in IL-15-induced innate cytotoxicity of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. (A) 1 × 106 CD8+ T cells from healthy donors were stimulated with IL-15 (20 ng/mL) for 48 h and 72 h, after which phosphorylation of signaling proteins was assessed by flow cytometry for STAT5 (n = 10), ERK1/2 (n = 7) and mTOR (n = 8). Representative dot plots and the summary data show the expression of signaling proteins in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. (B) The percentage of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells was analyzed after inhibitors treatment (n = 4). Representative dot plots from a single donor (left) and summary data (right) are presented. (C-G) The percentage NKG2D, FasL, perforin, and Granzyme B in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells were analyzed after inhibitors treatment (n = 4). (H) CD8+ T cells from healthy donors were pre-treated with STAT5 inhibitor pimozide, MEK inhibitor PD98059, PI3K inhibitor LY294002 or mTOR inhibitor PP242, followed by IL-15 (20 ng/mL) stimulation for the next 72 h. Then, CD8+ T cells were co-cultured with CFSE-labeled K562 cells at a 10:1 E: T ratio and cytotoxicity against K562 cells evaluated (n = 4). Representative dot plots and the summary data show expression of PI in the gate of CFSE+. (I) Schematic representation of cytokine-mediated crosstalk between T cells and liver cells in liver cirrhosis. The Wilcoxon matched-pairs signed rank test (A) was used for comparisons among groups. The one-way ANOVA (B, C, D-H) was used for comparisons between groups. Control group was indicated treatment only IL-15. ns, not significant, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

The above results indicate that CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells exert innate immune cytotoxicity through NKG2D and FasL-dependent pathways. Therefore, we investigated whether these signaling pathways can alter the expression of NKG2D and FasL on CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. After pre-treatment with the inhibitors (pimozide, LY294002 and PP242), the expression of IL-15-induced NKG2D on CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells was significantly reduced (Fig. 7C), and the proportion of FasL+CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells was significantly reduced by LY294002 and PP242 (Fig. 7D). The literature suggests that IL-15 can mediate innate immune cytotoxicity through NKG2D-dependent secretion of perforin and granzyme B21. Thus, we explored whether IL-15-activated signaling pathways affected the secretion of perforin and granzyme B in these cells. The proportion of IL-15-induced perforin+granzyme B+ cells was markedly reduced by PP242 (Fig. 7E). Meanwhile, Only PP242 significantly reduced the percentage of perforin+ cells, while LY294002 and PP242 reduced the number of granzyme B+ cells (Fig. 7F-G).

Finally, we investigated the effect of these signaling pathways on the innate-like cytotoxicity of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells in vitro. CD8+ T cells from healthy donors pre-treated with inhibitors pimozide, LY294002, or PP242 were stimulated with IL-15 for 72 h and then co-cultured with CFSE-labeled K562 cells for 6 h. The innate-like cytotoxicity of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells, activated by IL-15, was markedly suppressed by pimozide, LY294002, and PP242 (Fig. 7H).

Overall, these data demonstrate that the JAK/STAT5 and PI3K/mTOR pathways are pivotal in IL-15-induced innate-like cytotoxicity of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells (Fig. 7I).

Discussion

Research on the functions of bystander CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells has been controversial, and studies on these cells in the context of cirrhosis are sparse. This study showed that CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells were considerably increased in patients with cirrhosis compared to healthy donors. The increase in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells was considerably associated with disease severity, hepatic damage, and inflammation in cirrhosis. Furthermore, we found that IL-15-stimulated CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells exhibited innate-like cytotoxicity, dependent on NKG2D and FasL, in the absence of TCR. These cells also showed an upregulation of proliferative and cytotoxic molecules stimulated by IL-15. Notably, there was no distinction in the mitochondrial function of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells between patients with cirrhosis and healthy individuals, and IL-15 did not influence the mitochondrial function of these cells. Finally, this study demonstrated that IL-15 increased the expression of NKG2D and FasL on CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells through the activation of the JAK/STAT5 and PI3K/mTOR signaling pathways, thereby boosting the innate immunological cytotoxicity of these cells.

Bystander CD8+ T cells denote antigen-induced memory CD8+ T cells that are paradoxically activated in an antigen-independent manner. A previous study showed that the activation of bystander CD8+ T cells and the synthesis of cytotoxic molecules were associated with the severity of liver damage in acute hepatitis A (AHA)16. Furthermore, the inherent cytotoxicity of IL-15-activated human liver CD8+ mucosal-associated invariant T (MAIT) cells was linked to liver injury in patients with AHA22. Similarly, we observed a notable correlation between the percentage of activated CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells in peripheral blood and indicators of hepatic damage, such as AST, ALP, TBil, INR, NLR, ALB, and CHE in patients with cirrhosis. The prevalence of these cells was markedly greater in Child-Pugh class B and C patients compared to class A patients. Likewise, the proportion of these cells was significantly higher in patients with cirrhosis with ascites or infection than in those without these complications. Herein, we demonstrated that CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells were significantly increased in patients with cirrhosis relative to healthy donors, and this increase in cells was considerably associated with disease severity, liver damage indicators, and inflammation in cirrhosis.

IL-15 is a proinflammatory cytokine that plays a role in the formation, survival, proliferation, and activation of many lymphocyte lineages through numerous signaling pathways20. IL-15 is primarily derived from monocytes, dendritic cells, Kupffer cells, and hepatocytes in the liver microenvironment23–25. It was reported that IL-15-related liver-resident CXCR6+CD8+ T cells exhibit auto-aggressive behavior, leading to liver immunopathology in NASH26. Moreover, studies have shown that IL-15 can promote the activation of bystander CD8+ T cells14,16. Our experimental results further demonstrated that IL-15 not only increased the production of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells but also increased TIGIT, Ki-67, granzyme B, and perforin, consistent with existing literature findings16. This indicates that IL-15 plays a role in modulating the function of these T cells. Moreover, we observed that IL-15 did not induce the conversion of CD38−HLA-DR−CD8+ T cells into CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells but rather promoted the proliferation of pre-existing CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. Previous results indicate that IL-15 predominantly stimulated the proliferation of effector T cells. Earlier studies had shown that IL-15 could induce increased expression of NKG2D on CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. Our findings further demonstrates that IL-15 not only upregulates NKG2D expression but also promotes FasL expression on CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. Furthermore, in vitro cytotoxicity assays confirmed that IL-15 enhanced the cytotoxic activity of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells through the NKG2D and FasL pathways in a TCR-independent manner. Therefore, this result broadens the range of targets for CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells killing. Since innate-like cytotoxicity is dependent on NKG2D and FasL rather than TCR involvement, host cells expressing NKG2D and FasL ligands could be cytotoxic targets.

Given that CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells were found to exhibit innate-like cytotoxicity, we hypothesized that these cells might be influenced by mitochondrial homeostasis in a manner similar to NK cells27. Mitochondria greatly influence CD8+ T cell activity by altering their activation, differentiation, and metabolic reprogramming. The mitochondrial translation process specifically modulates the expression of various proteins, including those essential for cytotoxic T lymphocyte activity, such as cytokines, granzyme B, and perforin. Studies have shown that CD8+ T cells regulate mitochondrial metabolism in chronic infections19,28. However, the present study found that there was no significant difference in mitochondrial mass and mitochondrial ROS levels in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells from patients with cirrhosis compared to healthy donors. Additionally, the mitochondrial mass remained unchanged after IL-15 stimulation. These results suggest that IL-15 does not significantly alter mitochondrial function in CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells.

The present study showed that IL-15 promoted the expression of CD38+HLA-DR+ on CD8+ T cells and further increased the expression of NKG2D and FasL on CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. However, the fundamental molecular mechanisms remain unclear. Addtionally, IL-15 promoted the elimination of injured tissue cells by effector CD8+ T cells via the identification of stress and inflammatory signals, rather than specific antigens29. This process occurred via two separate yet complementary mechanisms, which included reducing the activation threshold of the TCR on effector CD8+ T cells and promoting TCR-independent lymphokine-activated killer activity in these cells29. The signaling pathways involved in these processes include JAK/STAT5, Ras/Raf/MEK, and PI3K/mTOR. The experimental results revealed that IL-15-stimulated CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells predominantly involve the JAK/STAT5 and PI3K/mTOR pathways, but not the Ras/Raf/MEK pathway. Additionally, we found that IL-15 could promote the expression of NKG2D and FasL via the JAK/STAT5 and PI3K/mTOR pathways, which is consistent with previous reports30,31. Furthermore, we noted that inhibiting the JAK/STAT5 or PI3K/mTOR pathways markedly diminished the innate-like cytotoxicity of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. NKG2D was suggested to be crucial in modulating the innate immunological cytotoxic activities of effector T cells. NKG2D is associated with the adapter molecule DNAX-activation protein 10 (DAP10), which possesses a PI3K activation motif. Notably, in liver diseases, the expression of NKG2D ligands is increased in liver tissues, suggesting its critical involvement in the immune response16. Similarly, FasL is an essential receptor for T cell-mediated innate immune functions. It binds to Fas on target cells, forming a trimeric complex in the cytoplasm. This complex is subsequently recruits the Fas-associated death domain protein, resulting in the recruitment and activation of caspase-8, which initiates a caspase cascade and eventually induces target cell death32. Although there is sparse data on the specific mechanisms by which IL-15 induces FasL expression in T cells, our findings demonstrate that IL-15 might increase FasL expression via the JAK/STAT5 and PI3K/mTOR pathways. However, further investigation is needed to fully elucidate this regulation mechanism.

The current study was limited by a small sample size, which may affect the generalizability of the findings. Although a link was identified between CD38 + HLA-DR + CD8 + T cells and disease severity, the study did not establish a direct causal relationship. Moreover, the cellular sources of IL-15 within the cirrhotic microenvironment were not thoroughly investigated. Lastly, although our study enrolled patients with cirrhosis of diverse etiologies, the cohort was predominantly composed of those with viral-induced hepatitis. Future research with larger cohorts should further explore the role of these cells in the pathogenesis of cirrhosis.

In conclusion, our findings indicate that bystander-activated CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells are associated with liver damage in patients with cirrhosis. IL-15-activated CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells demonstrated NKG2D- and FasL-mediated innate-like cytotoxicity independent of TCR. The JAK/STAT5 and PI3K/mTOR pathways played a crucial role in IL-15-induced activation of CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells. Thus, our data strongly suggest that CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells contribute to the immunopathology of liver cirrhosis. Therefore, targeting CD38+HLA-DR+CD8+ T cells may provide novel therapeutic approaches for managing liver cirrhosis.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Ke Liu: investigation (equal), Writing - original draft (equal); Hongliang Dong: methodology (equal), resources (equal); Kaiyuan Zhang: data curation (equal), resources (equal); Wanping Yan: project administration (equal), supervision (equal); Huanyu Wu: formal analysis (equal), resources (equal); Jing Fan: funding acquisition (equal), methodology (equal), writing - review & editing (equal); Wei Ye: Funding acquisition (equal), investigation (equal), writing - review & editing (equal).

Funding

This study was funded by the 333 Project of Jiangsu Province (Wei Ye), the Scientific research project of Jiangsu Provincial Health Commission (M2021074) (Wei Ye), the Medical Science and Technology Development Foundation, Nanjing Department of Health (grant numbers: YKK24177) (Wei Ye), the Talent Support Program of the Second Hospital of Nanjing (RCMS23001) (Jing Fan), Nanjing Infectious Disease Clinical Medical Center, Innovation center for infectious disease of Jiangsu Province (No. CXZX202232) (Wei Ye).

Data availability

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics statement

The studies were conducted in accordance with the local legislation and institutional requirements. The participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Jing fan, Email: fanjing@njucm.edu.cn.

Wei Ye, Email: yewei@njucm.edu.cn.

References

- 1.The global, regional, and national burden of cirrhosis by cause in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol, 5(3): pp. 245–266. (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Devarbhavi, H. et al. Global burden of liver disease: 2023 update. J. Hepatol.79 (2), 516–537 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gines, P. et al. Liver cirrhosis. Lancet398 (10308), 1359–1376 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammerich, L. & Tacke, F. Hepatic inflammatory responses in liver fibrosis. Nat. Rev. Gastroenterol. Hepatol.20 (10), 633–646 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wesche-Soldato, D. E. et al. CD8 + T cells promote inflammation and apoptosis in the liver after sepsis: role of Fas-FasL. Am. J. Pathol.171 (1), 87–96 (2007). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Breuer, D. A. et al. CD8(+) T cells regulate liver injury in obesity-related nonalcoholic fatty liver disease. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol.318 (2), G211–g224 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Koda, Y. et al. CD8(+) tissue-resident memory T cells promote liver fibrosis resolution by inducing apoptosis of hepatic stellate cells. Nat. Commun.12 (1), 4474 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tough, D. F., Borrow, P. & Sprent, J. Induction of bystander T cell proliferation by viruses and type I interferon in vivo. Science272 (5270), 1947–1950 (1996). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Huang, C. H. et al. Innate-like bystander-activated CD38(+) HLA-DR(+) CD8(+) T cells play a pathogenic role in patients with chronic hepatitis C. Hepatology76 (3), 803–818 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jia, X. et al. High expression of CD38 and MHC class II on CD8(+) T cells during severe influenza disease reflects bystander activation and trogocytosis. Clin. Transl Immunol.10 (9), e1336 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kim, T. S. & Shin, E. C. The activation of bystander CD8(+) T cells and their roles in viral infection. Exp. Mol. Med.51 (12), 1–9 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Arkatkar, T. et al. Memory T cells possess an innate-like function in local protection from mucosal infection. J. Clin. Invest., 133(10). (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 13.Lin, J. S. et al. Virtual memory CD8 T cells expanded by helminth infection confer broad protection against bacterial infection. Mucosal Immunol.12 (1), 258–264 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang, X. et al. IL-15 induced bystander activation of CD8(+) T cells May mediate endothelium injury through NKG2D in Hantaan virus infection. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol.12, 1084841 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Niehaus, C. et al. CXCR6(+)CD69(+) CD8(+) T cells in Ascites are associated with disease severity in patients with cirrhosis. JHEP Rep.6 (6), 101074 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kim, J. et al. Innate-like cytotoxic function of Bystander-Activated CD8(+) T cells is associated with liver injury in acute hepatitis A. Immunity, 48(1): pp. 161–173e5. (2018). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 17.Fan, J. et al. IL-15-induced CD38(+)HLA-DR(+)CD8(+) T cells correlate with liver injury via NKG2D in chronic hepatitis B cirrhosis. Clin. Transl Immunol.13 (10), e70007 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Balint, E. et al. Bystander activated CD8(+) T cells mediate neuropathology during viral infection via antigen-independent cytotoxicity. Nat. Commun.15 (1), 896 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Leavy, O. T cell responses: defective mitochondria disrupt CD8(+) T cells. Nat. Rev. Immunol.16 (9), 534–535 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mishra, A., Sullivan, L. & Caligiuri, M. A. Molecular pathways: interleukin-15 signaling in health and in cancer. Clin. Cancer Res.20 (8), 2044–2050 (2014). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Choi, Y. H. et al. IL-27 enhances IL-15/IL-18-mediated activation of human natural killer cells. J. Immunother Cancer. 7 (1), 168 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rha, M. S. et al. Human liver CD8(+) MAIT cells exert TCR/MR1-independent innate-like cytotoxicity in response to IL-15. J. Hepatol.73 (3), 640–650 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kim, J. et al. Innate-like cytotoxic function of Bystander-Activated CD8(+) T cells is associated with liver injury in acute hepatitis A. Immunity48 (1), 161–173 (2018). e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dominguez-Andres, J. et al. Inflammatory Ly6C(high) monocytes protect against candidiasis through IL-15-Driven NK cell/neutrophil activation. Immunity46 (6), 1059–1072 (2017). e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Waldmann, T. A. et al. The implications of IL-15 trans-presentation on the immune response. Adv. Immunol.156, 103–132 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Dudek, M. et al. Auto-aggressive CXCR6(+) CD8 T cells cause liver immune pathology in NASH. Nature592 (7854), 444–449 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Guo, X. et al. NAD + salvage governs mitochondrial metabolism, invigorating natural killer cell antitumor immunity. Hepatology78 (2), 468–485 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bengsch, B. et al. Bioenergetic insufficiencies due to metabolic alterations regulated by the inhibitory receptor PD-1 are an early driver of CD8(+) T cell exhaustion. Immunity45 (2), 358–373 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jabri, B. & Abadie, V. IL-15 functions as a danger signal to regulate tissue-resident T cells and tissue destruction. Nat Rev Immunol, 15(12): pp. 771 – 83. (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 30.Seok, J. et al. A virtual memory CD8(+) T cell-originated subset causes alopecia areata through innate-like cytotoxicity. Nat. Immunol.24 (8), 1308–1317 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Long, J. et al. Bone marrow CD8(+) Trm cells induced by IL-15 and CD16(+) monocytes contribute to HSPC destruction in human severe aplastic anemia. Clin. Immunol.263, 110223 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Myers, J. A. & Miller, J. S. Exploring the NK cell platform for cancer immunotherapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol.18 (2), 85–100 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated during and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.