Abstract

Rheumatoid arthritis is a chronic autoimmune inflammatory joint condition that progressively becomes devastating. Patient satisfaction with treatment is a predictor of medication adherence. Not only this, but it also affects the correct use of medication. Findings in this area are insufficient and contradictory. Therefore, this study aimed to assess treatment satisfaction and associated factors among patients with rheumatoid arthritis in northwest Ethiopia in 2024. A multi-center cross-sectional study was conducted among 393 rheumatoid arthritis patients attending the rheumatoid follow-up clinic of five comprehensive specialized hospitals in northwest Ethiopia from June 21 to September 20, 2024. A systematic random sampling technique was used to collect data. The Treatment Satisfaction with Medicines Questionnaire was used to determine treatment satisfaction. Face-to-face interviews with respondents from selected hospitals were used to gather data. Multiple linear regression was done to identify associated factors. Statistical significance was declared as p-value < 0.05. 393 participants were included in the study. The mean age was 52.28 (SD, 13.43). Around 75.6% were female, and 56.5% were married. Around 42.7% of patients had moderate disease activity, and 53.9% had comorbidities. The overall scores of treatment satisfaction were 52.8 (SD, 10.5). Treatment satisfaction was negatively associated with not taking therapeutic education (β = − 0.14, 95% CI (− 6.12, − 1.54), p = 0.001), high disease activity (β = − 0.31, 95% CI (− 12.64, − 0.45), p = 0.035), unavailability of medication (β = − 0.13, 95% CI (− 6.22, − 1.09), p = 0.005), ≥ 5-year duration of disease (β = − 0.16, 95% CI (− 7.01, − 1.45), p = 0.003). The present study revealed that overall treatment satisfaction was good. Duration of disease, disease activity, unavailability of medication and therapeutic education were factors affecting treatment satisfaction. Therefore, it is essential to prioritize therapeutic education and medication availability for patients with extended disease durations and high disease activity to improve treatment satisfaction.

Keywords: Treatment satisfaction, Rheumatoid arthritis, Ethiopia

Subject terms: Health care, Rheumatology, Risk factors

Introduction

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune condition that affects around 1% of people globally1. In developed nations, 5 to 10 individuals per 1000 suffer from this chronic inflammatory illness2. Rheumatoid arthritis negatively impacts 0.24% of the global population1. Compared to men, women are more commonly affected1,3. RA is a progressive illness associated with substantial morbidity and mortality1,4. In Africa, the prevalence of RA varies from 0.1 to 2.5% in urban areas and from 0.07 to 0.4% in rural regions1,5,6. In sub-Saharan Africa, rheumatoid arthritis affects approximately 59.1% of those with musculoskeletal disorders (MSD)7.

In sub-Saharan Africa, chronic inflammatory illnesses like RA are no longer viewed as major concerns; therefore, they are often identified too late and receive inadequate care8,9. Rheumatoid arthritis affected 18.5% of people in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, with 4.6 women for every man, indicating a substantial impact on women1. Rheumatoid arthritis was responsible for 3.4 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) between 1990 and 2017 worldwide10. Patients report up to 50% more fatalities than the general population11–13. Ethiopia accounted for 221 deaths, or 0.04% of total deaths related to RA, according to revised WHO data published in 20201.

Treatment satisfaction is a patient-reported outcome that provides valuable insights into the patient’s perspective on their willingness to continue treatment and reflects how they feel about the pros and cons of that treatment14,15. It is important because it can influence drug adherence, treatment persistence, and ultimately treatment outcomes16,17. Higher patient satisfaction is linked to improved health-related quality of life, predicts medication adherence, and affects proper medication use4. Patient satisfaction is vital in managing rheumatoid arthritis17,18. Additionally, it enables clinicians to better understand patients’ needs and preferences to achieve clinical remission17,19. Various factors such as therapeutic education, disease activity, or discomfort have been linked to treatment satisfaction20.

The treatment objectives are reducing disease activity, symptom relief, improving quality of life, and preventing joint deterioration2,21. Treatment choices include biologic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (bDMARDs), targeted synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (tsDMARDs), and conventional disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (cDMARDs)8,21. Corticosteroids and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory medicines (NSAIDs) are necessary when patients’ symptoms are not adequately controlled21,22.

Measuring patient-reported outcomes such as treatment satisfaction is essential, as patient satisfaction could increase treatment effectiveness and restore their sense of control4. To reduce the risk of serious relapses and hospitalization, it would be more effective to evaluate treatment satisfaction and assist patients in taking their medications as prescribed23.

According to author’s best literature search there are no studies published in Ethiopia and we observed a difference in the determinant factors between studies to close this gap and to provide evidence-based insight, intervention, and recommendations that enhance treatment satisfaction and also to give crucial hints for classifying and stratifying patients in follow-up care and optimizing care according to relevant precipitants. Therefore, this study examined treatment satisfaction and associated factors among patients with rheumatoid arthritis at comprehensive, specialized hospitals in Northwest Ethiopia.

Methods

Study area and period

The study was conducted from June 21 to September 20, 2024, in five public comprehensive specialized hospitals located in the Amhara region of Northwest Ethiopia, including the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (UOGCSH), Debre Markos Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (DMCSH), Tibebe Gion Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (TGCSH), and Debre Tabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (DTCSH), and Felege Hiwot Comprehensive Specialized Hospital (FHCSH). Amhara Regional Comprehensive Specialized Hospital is a healthcare facility located in the northwestern region of Amhara. Established to provide comprehensive medical services to the local population, it serves as a referral center for patients requiring specialized care from the surrounding area. The hospital offers a range of services; all selected hospitals provide rheumatoid arthritis care in their chronic Patient care clinics.

Study design, population, inclusion and exclusion criteria

A multicenter cross-sectional study was conducted. The source population was all patients with rheumatoid arthritis who had regular follow-ups at comprehensive specialized hospitals in northwest Ethiopia. The study population was all patients with rheumatoid arthritis who visited chronic follow-up clinics and fulfilled the inclusion criteria during the data collection period. Participants ≥ 18 years or older and willing to provide written informed consent, definitive diagnosis of rheumatoid arthritis and taking medication for rheumatoid arthritis for greater than 6 months were included in the present study. Participants who were unable to communicate due to severe illness, psychiatric problems, or neurological illness, suffer from chronic inflammatory diseases like psoriatic arthritis, ankylosing spondylitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, gout, systemic sclerosis and other autoimmune rheumatic diseases like osteoarthritis, still’s disease, dermatomycosis, and antiphospholipid syndrome other than rheumatoid arthritis and, participants are not willing to participate during data collection were excluded.

Sample size determination and sampling technique

Using the single population proportion formula, the sample size was determined as follows:

|

where n = the required sample, degree of accuracy (95% level of significance = 1.96), p = expected proportion of treatment satisfaction among rheumatoid arthritis patients assumed to be 0.5 (50%) this is because as far as literature search has done there is no study previously on treatment satisfaction among rheumatoid arthritis patients in Ethiopia.

Margin of error, which is 5% (0.05): therefore,

|

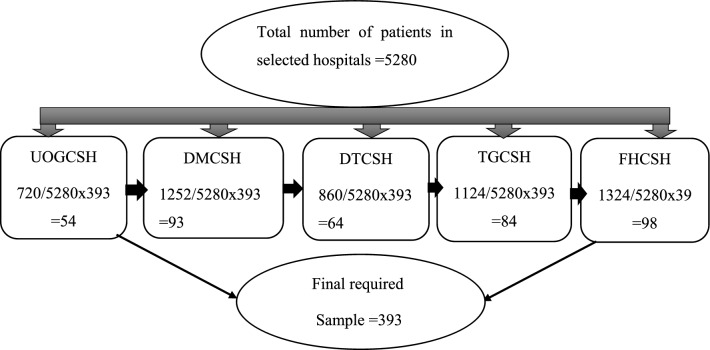

The total number of RA patients registered in selected hospitals similar to the study period was as follows:

720, patients at the University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital.

1252, patients at Debre Markos Comprehensive Specialized Hospital.

860, patients at Debre Tabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital.

1124, patients at Tibebe Gion Comprehensive Specialized Hospital.

1324, patients at Felege Hiwot Comprehensive Specialized Hospital.

These hospitals reported 5280 RA patients in total. Each hospital’s medical records served as the source of this data. Based on the data, the sample size in each hospital would be; since the total population was less than 10,000, we used the correction formula to determine the final sample size. nf = = 357. By adding a 10% contingency for the non-response rate, the final calculated sample size was 393 (Supplementary Information).

= 357. By adding a 10% contingency for the non-response rate, the final calculated sample size was 393 (Supplementary Information).

All five comprehensive specialized hospitals found in Northwest Ethiopia were included in the study. A systematic random sampling technique was employed to select the study participants. Then, the total sample size was allocated proportionally for each hospital, and proportional allocation of the sample to the total population of each hospital was applied using the formula as follows: n = n × Ni/N, where n = required sample size, Ni = the total number of patients in each hospital; N = the total number of patients. Following proportional allocation, study participants were chosen using a systematic random sampling procedure. The sampling fraction (k = 13) divides the study area’s total number of participants by the total sample size.

The starting points were selected randomly from 1 to 13. Then, for each hospital that was chosen, participants were interviewed every thirteenth interval. At the same time, pertinent information was examined from each patient’s medical chart, like comorbidity, total number of medications and treatment regimen, every thirteenth patient until the necessary samples were collected. Four bachelor pharmacists and two nurses with training took part in gathering the data. A unique patient identification card number was used as a code on the questionnaire to avoid including the same patient in the study more than once.

A detailed description of the sampling procedures is presented below (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Sampling procedure of health-related quality of life, treatment satisfaction and associated factors in patients with rheumatoid arthritis in North West Ethiopia, 2024.

Study variables

Treatment satisfaction was the outcome variable, while, socio-demographic factors (sex, age, insurance, occupation, marital status, educational status, and place of residence), clinical factors (disease activity, BMI, comorbid condition, disease duration, and history of skeletal surgery) and treatment-related factors (number of medications, treatment regimen, therapeutic education, and unavailability of medication).

Operational definition

BMI

The BMI is categorized into three groups. Based on BMI, patients were divided into three groups: those with a BMI between 18.5 and 25 kg/m2 were classified as having a normal BMI. Alternatively, individuals classified as overweight or obese were those whose BMI was 25 < BMI < 30 kg/m2 and those whose BMI was > 30 kg/m2, respectively24,25.

Therapeutic education

Describes the instruction given to patients about their course of therapy, which is crucial for adherence and the best possible care of RA, Drug unavailability refers to the inability to access disease-modifying antirheumatic medications (DMARDs), such as biological DMARDs (bDMARDs), targeted synthetic DMARDs (tsDMARDs), and conventional synthetic DMARDs (csDMARDs), during follow-up visits26.

Treatment satisfaction

The observed total composite scores were converted to a measure with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 100 that is more understandable and intuitive. Patients with good treatment satisfaction scores are close to 100, while those who score closer to 0 have poor satisfaction17.

Data collection instrument and procedure

A structured questionnaire was taken from earlier research4,27–29. It was prepared in English and translated into the Amharic local language by two individuals fluent in both Amharic and English. Data was collected by interviewing the respective participants. The data collection tool has three parts. The first section includes the participants’ sociodemographic details. The second section consists of clinically related variables.

Disease activity was measured using the Disease Activity Score 28 (DAS28) at the follow-up appointment of each study participant. A tool for assessing treatment satisfaction was included in the third part. The Treatment Satisfaction with Medicines Questionnaire (SATMED-Q), comprising 17 items spanning 6 categories, which are treatment effectiveness (3 items), ease of use (3 items), unwanted side effects (3 items), medical care (2 items), impact on daily activities (3 items), and overall satisfaction (3 items), was used to measure treatment satisfaction. It was validated and used worldwide for all chronic diseases, including rheumatoid arthritis, with a Cronbach alpha > 0.8929,30. An ordinal score on a five-point Likert scale is assigned to each of the specified domains: very much satisfied = 4 points, quite a bit = 3 points, somewhat satisfied = 2 points, a little bit = 1 point, and not at all = 0 points. A total composite score, ranging from 0 to 68 points, was obtained by adding all the direct scores. The observed total composite score was transformed using the following formula into a more understandable and intuitive metric with a minimum of 0 and a maximum of 100: Ymax − Ymin/(Yobs − Ymin) = Yʹ When Ymin is the lowest total score, Ymax is the highest total score, and Yʹ is the transformed score, the patient’s overall score is represented by × 100 = Yobs × 1.471. Every dimension has a comparable statement31.

Data quality control

The principal investigator provided extensive training to data collectors regarding questionnaire content, data collection techniques, and ethical considerations for 1 day at each study site for both data collectors and supervisors. A pretest was done on 19 RA patients (5% of the study participants) in the University of Gondar comprehensive specialized hospitals before data collection started. In the pre-test, patients were asked whether they found any of the questions confusing, difficult to answer or understand, upsetting, or offensive. Nevertheless, no difficulty in answering the question was observed. The internal consistency and reliability of the treatment satisfaction with medicines questionnaire were checked. We found the tool was reliable and valid with Cronbach alpha ranging from 0.79 for global satisfaction domains to 0.97 for side effect domains for all subscales of the Treatment Satisfaction with Medicines Questionnaire. The patients participating in the pretest study were not included in the final analysis. The principal investigator oversaw the gathering of data and provided comments and adjustments.

Data entry and analysis

The collected data were cleaned, coded, entered into EpiData version 4.6.2, and analyzed using the statistical package for social studies (SPSS) version 26. Data was treated and expressed using their respective measurements, descriptive (frequencies) and inferential (univariable and multivariable linear regression) analysis methods. The variables with p-values less than 0.25 in the univariable analysis of the predictors were incorporated into the multivariable model. Simple linear regression and multiple linear regression models were used to identify factors associated with the treatment satisfaction of RA patients. The assumption of linearity, normality, homogeneity of variances, presence of outliers, and multicollinearity between the predicted variables was checked for linear regression. Scatter plots demonstrate that the outcome variable’s linear relationship with the independent variables was satisfied. The assumption that the values of residuals are independent has been met, as we obtained the Durbin–Watson statistics values close to 2 for all overall treatment satisfaction scores. The standardized residuals vs. standardized predicted values plot revealed no discernible funneling, indicating that the homoscedasticity assumption was satisfied. The p–p plot shows that the dots lie closer to the diagonal line and the skewness ranges between ± 1, suggesting the assumption of normality has been met. Analysis of collinearity statistics shows that there was no multicollinearity between the independent variables, as VIF scores were below 4. A multiple linear regression analysis’s p-values of less than 0.05 were regarded as an independent predictor of treatment satisfaction. The model fitness was run and found to be statistically significant at F = 14.47, p-value 0.000, R = 0.604, R square = 0.365, and adjusted R square = 0.340 for overall treatment satisfaction. Standardized beta coefficients with 95% CI were used to assess the level of association and Statistical significance in multiple linear regression analysis.

Ethical considerations

The proposal was submitted to the Department of Clinical Pharmacy, and ethical clearance was obtained from the University of Gondar Department of Clinical Pharmacy, Research and Ethical Review Committee, with a reference number, SOPS/288/2016 and a permission letter was obtained from the department for each study set up. The nature of the study was fully explained to the study participants, and written informed consent was obtained. This study was done complying with the Declaration of Helsinki. Furthermore, to maintain the confidentiality of the responses, no personal identifiers were included in the questionnaires. Additionally, the study participants’ right to refuse participation was communicated to both the participant and their caregiver at any time.

Result

Socio-demographic and clinical-related characteristics of the study participants

Three hundred ninety-three adult patients participated in this study. The mean age of participants was 52.28 (SD = 13.43), which ranged from 19 to 85 years. Females comprised nearly three-quarters of the sex category 279 (75.6%). In addition, 222 (56.5%) were married. More than half of the study participants were urban, 216 (55%); and 201 (51.1%) had health insurance. The majority of respondents (69.5%) had a disease duration of ≥ 5 Years, and 42.7% of respondents had Moderate Disease activity. Two hundred twelve (53.9%) had one or more comorbid diseases; of these, 47.65% were hypertension, followed by diabetes mellitus (16.5%), and 81.4% of participants were taking three or more medications. The majority of the study participants do not take therapeutic education (80.9%), and 44.8% of participants use substances, of which 29.8% were alcohol (Table 1).

Table 1.

Socio-demographic and clinical-related characteristics of study participants in a selected comprehensive specialized hospital, North West Ethiopia, 2024 (N = 393).

| Variable | Frequency (N = 393) | Percent (%) | Variable | Frequency (N = 393) | Percent (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | Disease duration | ||||

| Male | 96 | 24.4 | < 5 Years | 120 | 30.5 |

| Female | 297 | 75.6 | ≥ 5 Years | 273 | 69.5 |

| Age in years | Mean (± SD) 52.28 (± 13.43) | Disease activity | |||

| 18–40 | 84 | 21.4 | Low | 122 | 31 |

| 41–65 | 237 | 60.3 | Moderate | 168 | 42.7 |

| > 65 | 72 | 18.3 | High | 103 | 26.3 |

| Marital status | BMIa | Mean (± SD) 22.54 ± 4.7 | |||

| Married | 222 | 56.5 | Underweight | 39 | 9.9 |

| Single | 102 | 26.0 | Normal | 96 | 24.4 |

| Widowed | 51 | 13.0 | Overweight | 147 | 37.5 |

| Divorced | 18 | 4.5 | Obese | 111 | 28.2 |

| Residence | Skeletal surgery | ||||

| Urban | 216 | 55 | Yes | 135 | 34.4 |

| Rural | 177 | 45 | No | 258 | 65.6 |

| Religion | Number of medication | ||||

| Orthodox | 291 | 74 | One | 3 | 0.8 |

| Muslim | 60 | 15.3 | Two | 70 | 17.8 |

| Protestant | 27 | 6.9 | Three or more | 320 | 81.4 |

| Othersa | 15 | 3.8 | Comorbid disease | ||

| Educational status | |||||

| Uneducated | 241 | 61.3 | Yes | 212 | 53.9 |

| Able to read and write | 30 | 7.6 | No | 181 | 46.1 |

| 1–8 grade | 18 | 4.6 | Specify | ||

| 9–12 grade | 40 | 10.2 | Hypertension | 94 | 23.9 |

| Diploma and above | 64 | 16.3 | Diabetes mellitus | 37 | 9.4 |

| Occupational status | Asthma | 20 | 5.1 | ||

| Housewife | 108 | 27.5 | Dyslipidemia | 18 | 4.6 |

| Student | 12 | 3.1 | HIV AIDS | 9 | 2.3 |

| Jobless | 75 | 19.1 | Major depressive disorder | 7 | 1.8 |

| Daily labor | 86 | 21.9 | Othersb | 27 | 6.8 |

| Private business | 37 | 9.3 | Substances use | ||

| Employed | 75 | 19.1 | Yes | 176 | 44.8 |

| Insurance | No | 217 | 55.2 | ||

| Yes | 201 | 51.1 | Specify | ||

| No | 192 | 48.9 | Alcohol | 117 | 29.8 |

| Khat | 24 | 6.1 | |||

| Alcohol and Khat | 21 | 5.3 | |||

| Cigarette | 14 | 3.6 | |||

| Medication unavailability | |||||

| Yes | 330 | 84.0 | |||

| No | 63 | 16.0 | |||

SD standard deviation.

aCatholic, Jewish, Body mass index.

bChronic obstructive pulmonary disease, ischemic heart disease, chronic heart failure.

Medication and management of rheumatoid arthritis

Most patients (62.42%) who were treated for rheumatoid arthritis used folic acid and methotrexate together. The patients’ primary corticosteroid treatment was prednisolone, while their primary non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drug was meloxicam (22.79%), followed by indomethacin (24.79%) (Table 2).

Table 2.

Medication and management of rheumatoid arthritis participants in a selected comprehensive specialized hospital, North West Ethiopia, 2024 (N = 393).

| Medication | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|

| Meloxicam, folic acid, MTX, prednisolone, indomethacin | 12 (3.1%) |

| Meloxicam, ibuprofen | 82 (20.8%) |

| Meloxicam, MTX, folic acid | 4 (1.02%) |

| MTX, folic acid, indomethacin, meloxicam | 24 (6.12%) |

| MTX, folic acid | 39 (9.9%) |

| MTX, folic acid, indomethacin | 28 (7.12%) |

| MTX, folic acid, meloxicam, indomethacin | 23 (5.85%) |

| MTX, folic acid, meloxicam, prednisolone | 22 (5.58%) |

| MTX, folic acid, indomethacin, prednisolone | 12 (3.1%) |

| MTX, folic acid, prednisolone | 47 (11.95%) |

| MTX, folic acid, indomethacin, prednisolone, meloxicam | 11 (2.79%) |

| Meloxicam, folic acid, MTX, tramadol | 11 (2.79%) |

| Meloxicam, diclofenac, chloroquine | 11 (2.79%) |

| Indomethacin, prednisolone | 31 (7.89%) |

| Meloxicam, folic acid, indomethacin | 24 (6.1%) |

| Folic acid, MTX, prednisolone | 12 (3.1%) |

MTX methotrexate.

Treatment satisfaction of the study participants

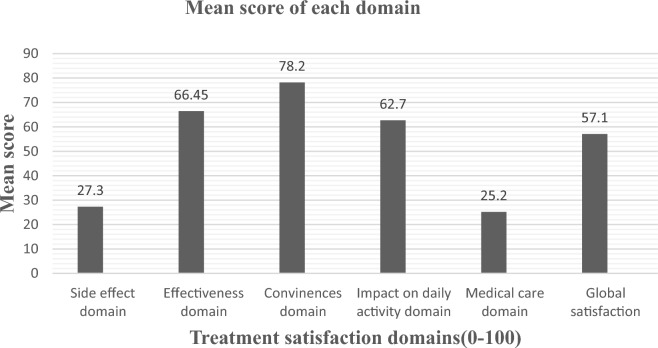

The overall treatment satisfaction composite score of the study participants was 52.8 (SD, 10.5). The highest scores were found in the treatment convenience or ease of use domain, 78.2 (SD, 24.9), and the lower scores were reported in undesirable side effects, 27.3 (SD, 25.1). The lowest scores were reported in the medical care or follow-up 25.2 (SD, 23.7) domain (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2.

Mean score of treatment satisfaction domain of rheumatoid arthritis participants in a selected comprehensive specialized hospital, North West Ethiopia, 2024 (N = 393).

Simple and multiple linear regression for factors associated with treatment satisfaction

Unavailability of medication, ≥ 5 years’ duration of disease, high disease activity, and not taking therapeutic education were significant factors affecting treatment satisfaction with a p-value less than 0.05 (Table 3).

Table 3.

Simple and multiple linear regression for treatment satisfaction in selected comprehensive specialized hospitals, North West Ethiopia, 2024 (N = 393).

| Variables | SLRa | MLRb | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| β | 95% CI | p-value | β | 95% CI | p-value | |||

| Lower | Upper | Lower | Upper | |||||

| Marital status (Ref = married) | ||||||||

| Single | − 3.32 | − 5.74 | − 0.89 | 0.007 | − 0.07 | − 6.21 | 0.55 | 0.102 |

| Divorced | 1.76 | − 1.16 | 4.69 | 0.32 | – | – | – | – |

| Windowed | − 4.81 | − 8.13 | − 1.49 | 0.005 | − 0.034 | − 3.99 | 1.74 | 0.44 |

| Therapeutic education (Ref = Yes) | ||||||||

| No | − 3.12 | − 5.71 | − 0.43 | 0.023 | − 0.14 | − 6.12 | − 1.54 | 0.001 |

| BMI (Ref = Normal) | ||||||||

| Overweight | − 2.21 | − 4.79 | 0.39 | 0.098 | 0.08 | − 3.63 | 7.42 | 0.501 |

| Obese | − 10.11 | − 12.37 | − 7.69 | < 0.001 | − 0.14 | − 8.97 | 2.93 | 0.312 |

| Disease duration (Ref ≤ 5 year) | ||||||||

| > 5 Years | − 7.15 | − 9.67 | − 4.63 | < 0.001 | − 0.16 | − 7.01 | − 1.45 | 0.003 |

| Disease activity (Ref = Low) | ||||||||

| Moderate | − 1.89 | − 4.45 | 0.67 | 0.14 | − 0.01 | − 5.61 | 5.56 | 0.99 |

| High | − 10.68 | − 13.1 | − 8.28 | < 0.001 | − 0.31 | − 12.64 | − 0.45 | 0.035 |

| Unavailability of medication (Ref = No) | ||||||||

| Yes | − 2.67 | − 5.51 | 0.16 | 0.064 | − 0.13 | − 6.22 | − 1.09 | 0.005 |

BMI body mass index, CI confidence interval, β-regression coefficient.

aSimple linear regression.

bMultiple linear regression.

Significant values are in bold.

Patients facing medication unavailability during treatment have 0.13 times lower overall treatment satisfaction composite mean scores compared to those not (β = − 0.13, 95% CI (− 6.22, − 1.09), p = 0.005), Patients not taking therapeutic education about treatment have 0.14 times lower overall treatment satisfaction composite mean scores compared to those taking therapeutic education (β = − 0.14, 95% CI (− 6.12, − 1.45), p = 0.001), Patients who are living with high rheumatoid disease activity have 0.31 times lower overall treatment satisfaction composite mean scores compared to low disease activity (β = − 0.31, 95% CI (− 12.64, − 0.45), p = 0.035), Patients who have been living with RA for ≥ 5 years have 0.16 times lower overall treatment satisfaction composite mean scores compared to < 5-year duration of disease (β = − 0.16, 95% CI (− 7.01, − 1.45), p = 0.003).

Discussion

Despite the high incidence of RA, this is the first multicenter study to assess treatment satisfaction and its associated factors among RA patients in Northwest Ethiopia. Our findings revealed that the total composite score for treatment satisfaction was 52.8, and there were significant correlations between treatment satisfaction and factors including high disease activity, lack of therapeutic education, medication unavailability, and disease duration (≥ 5 years).

The overall treatment satisfaction score was 52.8 (51.8–53.9), comparable with a study conducted in Palestine 54.2 (37.5–66.4)4. Our study revealed the lowest scores in medical care follow-up domains (25.2). Contrast this to the study in Palestine, which was 54.84. This discrepancy could be attributed to differences in healthcare infrastructure. In Ethiopia, limitations in follow-up care and patient-provider communication may contribute to lower satisfaction levels. In Palestine may be more structured follow-up care and therapeutic education, positively affecting patient satisfaction4. Suboptimal RA treatment satisfaction in Ethiopia, especially regarding follow-up care, underscores the necessity for healthcare improvements and better patient-provider communication.

In the current study, 52.8% had good overall satisfaction with treatment, which is higher than the study conducted in Tunisia 39%, Sudan 26%, and the United States 25%17,32,33. The possible reasons for the higher satisfaction in our findings might be the large sample size, the use of the new six-domain treatment satisfaction tool, and differences in study populations. For example, a study in the United States used only a 258-sample size and a TSQM global satisfaction score ≥ 80 measurement tool, and the United States reported low patient satisfaction despite having a sophisticated healthcare system, which may be related to things like expensive medical care and difficult healthcare navigation.

In this study, the SATMED-Q domain mean scores were as follows: 66.45 for effectiveness, 78.2 for convenience, 27.2 for medical treatment, 57.1 for global satisfaction, 62.7 for impact on daily activity, and 27.3 for side effect, this is in line with study’s conducted in 18 countries across Europe, Asia, and South America34.

In this study, various socio-demographic and clinical characteristics were checked in multivariable linear regression analysis for their possible influences on treatment satisfaction. Significantly, lower treatment satisfaction was seen among participants facing the unavailability of medication when compared with non-problem medication availability. These findings are in line with other similar studies16,4. The possible justification may be when patients facing medication unavailability experience worsening health conditions that lead to increased symptoms and complications, increased stress and anxiety, and perception of inadequate care, which leads to poor satisfaction with treatment35. Improve RA treatment satisfaction by ensuring consistent medication access, addressing affordability, and providing comprehensive physical and psychological support to patients facing unavailability.

This study found that participants not taking therapeutic education had significant impacts on treatment satisfaction as compared to those taking therapeutic education, which was decreased by 0.14 times. Our results were consistent with previous studies17. This may be due to patients not receiving therapeutic education, reduced adherence, unrealistic expectations of treatment, and lack of education, which worsens psychological well-being and reduces the quality of life, impacting patient treatment satisfaction36. Enhance RA treatment satisfaction by providing comprehensive therapeutic education to improve adherence, expectations, well-being, and quality of life.

Patients who have been living with RA for more than 5 years have reduced treatment satisfaction by 0.16 times compared to those who were living with it for 5 years or less; similar findings were reported in a study conducted in China37. The possible reason for this may be that patients living with RA for more than 5 years have reduced treatment satisfaction due to increased disease progression, severity of symptoms, and chronic fatigue. In addition to this, patients may have limited treatment options, which leads to feelings of hopelessness regarding their treatment16. This study found that higher disease activity decreased treatment satisfaction by 0.31 times as compared to low disease activity. Our results were consistent with most existing literature strongly negatively associating disease activity with treatment satisfaction of rheumatoid patients16,20. This is due to increased symptoms like pain and fatigue, leading to poor expectations of treatment outcomes. This condition influences quality of life and exacerbates psychological issues like anxiety and depression, leading to dissatisfaction with treatment34. Improve RA treatment satisfaction by aggressively managing disease activity to reduce symptoms, improve expectations, enhance quality of life, and mitigate psychological distress.

The implication of these findings suggests a need for targeted interventions in Ethiopia to improve treatment satisfaction. Addressing factors like medication availability and disease management could enhance overall treatment satisfaction. Additionally, public health initiatives should consider the socio-demographic influences on treatment satisfaction. Furthermore, the levels of treatment satisfaction provide a helpful starting point for monitoring future interventions. According to this study, there may be an association between greater disease activity and reduced satisfaction, suggesting that people with lower levels of satisfaction may also have worse disease control. Clinical outcomes and treatment satisfaction may both be enhanced by initiatives to enhance disease management and lower disease activity in Ethiopia.

Strengths and limitations of the study

This study was multicenter, which will create a database for RA disease in North West Ethiopia, which is preferable for generalizability. We used a tool, which is mostly applied and validated in Ethiopia, to assess the patients’ treatment satisfaction and excellent response rate and sufficient sample size were the strengths of the study. This study also has some limitations. Information such as the dose of prescribed medication was not collected; in addition, patient and physician interaction was not assessed. Due to the study’s reliance on self-reported surveys, reporting biases may be present. It is impossible to prove a causal relationship between satisfaction and related factors due to the cross-sectional design. Despite being multicenter, the results might not apply to all Ethiopian RA patients, especially those who live in remote residences or different types of treatment settings.

Conclusion

Overall, treatment satisfaction of rheumatoid arthritis patients in North West Ethiopia was good; it is strongly influenced by disease activity, therapeutic education, disease duration and medication access. Patient-centered treatment requires addressing these modifiable factors with focused interventions. This makes it possible to identify at-risk patients swiftly. In areas with limited resources, provider and policymaker collaboration will alter rheumatoid arthritis care, improve clinical outcomes, and increase treatment satisfaction.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

First, I would like to express my heartfelt thanks to almighty God, who blessed me with adequate strength to complete this thesis. I am very grateful to Debre Tabor University for sponsoring me to attend the MSc program. In addition, I would like to express my gratitude to the University of Gondar, the School of Pharmacy, and the Department of Clinical Pharmacy for its formal permission. I am very thankful to the study participants for their willingness to participate and the data collectors for cooperating in the data collection process.

Abbreviations

- BDMARDs

Biological disease-modifying ant-rheumatic drugs

- BMI

Body mass index

- CI

Confidences interval

- CsDMARDs

Conventional synthetic disease-modifying ant rheumatic drugs

- DMARD

Disease-modifying ant-rheumatic drugs

- DMCSH

Debre Markos Comprehensive Specialized Hospital

- DTCSH

Debre Tabor Comprehensive Specialized Hospital

- FHCSH

Felege Hiwot Comprehensive Specialized Hospital

- MSD

Musculoskeletal disorder

- MTX

Methotrexate

- NSAIDs

Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs

- RA

Rheumatoid arthritis

- SPSS

Statistical package for social studies

- TGCSH

Tibebe Gion Comprehensive Specialized Hospital

- TsDMARDs

Targeted synthetic Disease-modifying ant rheumatic disease

- TSQM

Treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication

- UOGCSH

University of Gondar Comprehensive Specialized Hospital

- WHO

World Health Organization

Author contributions

TE: contributed to the inception, design, analysis, interpretation, and drafting of the research manuscript, AF: contributed to the inception, design, analysis, and interpretation, AT: contributed to the inception, design, analysis, and interpretation, DA: contributed to the inception, design, analysis, interpretation, and drafting of the research manuscript, WS: contributed to the inception, design, analysis, interpretation, and drafting of the research manuscript, FN: contributed to the inception, design, analysis, and interpretation, GY: contributed to the source, design, analysis, and interpretation, SB: contributed to the inception, design, analysis, and interpretation, TA: contributed to the source, design, analysis, and interpretation, BY: contributed to the source, design, analysis, interpretation, and drafting of the research manuscript, EA: contributed to the source, design, analysis, interpretation, and drafting of the research manuscript, TB: contributed to the source, design, analysis, and interpretation, AT: contributed to the source, design, analysis, interpretation, and drafting of the research manuscript. All authors read and approved the revised manuscript for publication.

Data availability

Data will be disclosed upon a reasonable request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Consent for publication

Consent was directly obtained from the patients.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-02199-1.

References

- 1.Bogale, Z. & Feleke, Y. Prevalence, clinical manifestations, and treatment pattern of patients with rheumatoid arthritis attending the rheumatology clinic at Tikur Anbessa specialized hospital, Ethiopia: A cross-sectional study. Open Access Rheumatol.14, 221–229 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aletaha, D. & Smolen, J. S. Diagnosis and management of rheumatoid arthritis: A review. JAMA320(13), 1360–1372 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cross, M. et al. The global burden of rheumatoid arthritis: Estimates from the global burden of disease 2010 study. Ann. Rheum. Dis.73(7), 1316–1322 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Abu Hamdeh, H., Al-Jabi, S. W., Koni, A. & Zyoud, S. H. Health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction in Palestinians with rheumatoid arthritis: A cross-sectional study. BMC Rheumatol.6(1), 19 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudan, I. et al. Prevalence of rheumatoid arthritis in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review and analysis. J. Glob. Health5(1), 010409 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Usenbo, A., Kramer, V., Young, T. & Musekiwa, A. Prevalence of arthritis in Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE10(8), e0133858 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Irungu, S. W. Health Related Quality of Life and Treatment Regimens in Patients with Musculoskeletal Disorders at Kenyatta National Hospital (University of Nairobi, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kolou, M. Challenges of rheumatoid arthritis management in sub-Saharan Africa in the 21st century. Open J. Rheumatol. Autoimmune Dis.13(1), 17–40 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Halabi, H. et al. Challenges and opportunities in the early diagnosis and optimal management of rheumatoid arthritis in Africa and the Middle East. Int. J. Rheum. Dis.18(3), 268–275 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safiri, S. et al. Global, regional and national burden of osteoarthritis 1990–2017: A systematic analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Ann. Rheum. Dis.79(6), 819–828 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoshida, K. et al. Roles of postdiagnosis accumulation of morbidities and lifestyle changes in excess total and cause-specific mortality risk in rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res.73(2), 188–198 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Houge, I. S., Hoff, M., Thomas, R. & Videm, V. Mortality is increased in patients with rheumatoid arthritis or diabetes compared to the general population—The Nord-Trøndelag Health Study. Sci. Rep.10(1), 3593 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Essouma, M., Nkeck, J. R., Endomba, F. T., Bigna, J. J. & Ralandison, S. Epidemiology of rheumatoid arthritis in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis protocol. Syst. Rev.9(1), 81 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kim, S. K. et al. Comparisons of treatment satisfaction and health-related quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis treated with tofacitinib and adalimumab. Arthritis Res. Ther.25(1), 68 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Abu Hamdeh, H., Al-Jabi, S. W. & Koni, A. Health-related quality of life and treatment satisfaction in Palestinians with rheumatoid arthritis: A cross-sectional study. BMC Rheumatol.6(1), 1–12 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li, H. B. et al. Treatment satisfaction with rheumatoid arthritis in patients with different disease severity and financial burden: A subgroup analysis of a nationwide survey in China. Chin. Med. J. (Engl.)133(8), 892–898 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miladi, S. et al. Patient satisfaction with medication in rheumatoid arthritis: An unmet need. Reumatologia61(1), 38–44 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ishikawa, H., Hashimoto, H. & Yano, E. Patients’ preferences for decision making and the feeling of being understood in the medical encounter among patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Rheum.55(6), 878–883 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Salomon-Escoto, K. & Kay, J. The, “treat to target” approach to rheumatoid arthritis. Rheum. Dis. Clin. N. Am.45(4), 487–504 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Schäfer, M. et al. Factors associated with treatment satisfaction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Data from the biological register RABBIT. RMD Open6(3), e001290 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Joseph, T. et al. Pharmacotherapy: A Pathophysiologic Approach (McGraw-Hill Education, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 22.Radu, A. F. & Bungau, S. G. Management of rheumatoid arthritis: An overview. Cells10(11), 1 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Miladi, S. et al. Patient satisfaction with medication in rheumatoid arthritis: An unmet need. Reumatologia61(1), 38 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Safita, N. et al. The impact of type 2 diabetes on health related quality of life in Bangladesh: Results from a matched study comparing treated cases with non-diabetic controls. Health Qual. Life Outcomes14, 1–9 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Esubalew, H. Assessment of Health Related Quality of Life and Its Determinants Among Type II Diabetes Mellitus Patients in Selected Public Hospitals of Addis Ababa (Addis Ababa University, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 26.Katchamart, W., Narongroeknawin, P., Chanapai, W. & Thaweeratthakul, P. Health-related quality of life in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. BMC Rheumatol.3, 34 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Esubalew, H. et al. Health-related quality of life among type 2 diabetes mellitus patients using the 36-item short form health survey (SF-36) in Central Ethiopia: A multicenter study. Diabetes Metab. Syndr. Obes.17, 1039–1049 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kebede, D. et al. Health related quality of life (SF-36) survey in Butajira, rural Ethiopia: Normative data and evaluation of reliability and validity. Ethiop. Med. J.42(4), 289–297 (2004). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ruiz, M. A. et al. Development and validation of the “treatment satisfaction with medicines questionnaire” (SATMED-Q). Value Health11(5), 913–926 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Atkinson, M. J. et al. Validation of a general measure of treatment satisfaction, the treatment satisfaction questionnaire for medication (TSQM), using a national panel study of chronic disease. Health Qual. Life Outcomes2, 1–13 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wondesen, A., Berha, A. B., Woldu, M., Mekonnen, D. & Engidawork, E. Impact of medication therapy management interventions on drug therapy problems, medication adherence and treatment satisfaction among ambulatory heart failure patients at Tikur Anbessa Specialised Hospital, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia: A one-group pre–post quasi-experimental study. BMJ Open12(4), e054913 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ali, Z. A. H., Abd El-Raheem, G. O. H. & Noma, M. Status of rheumatoid arthritis practice and treatment in Sudan. Sci. Afr.22, e01939 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Radawski, C. et al. Patient perceptions of unmet medical need in rheumatoid arthritis: A cross-sectional survey in the USA. Rheumatol. Ther.6, 461–471 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Taylor, P. C. et al. Treatment satisfaction, patient preferences, and the impact of suboptimal disease control in a large international rheumatoid arthritis cohort: SENSE study. Patient Prefer. Adher.15, 359–373 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Cross, A. J., Elliott, R. A., Petrie, K., Kuruvilla, L. & George, J. Interventions for improving medication-taking ability and adherence in older adults prescribed multiple medications. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev.5(5), CD012419 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Naqvi, A. A., Hassali, M. A., Naqvi, S. B. S. & Aftab, M. T. Impact of pharmacist educational intervention on disease knowledge, rehabilitation and medication adherence, treatment-induced direct cost, health-related quality of life and satisfaction in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: Study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials20, 1–11 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jiang, N. et al. Satisfaction of patients and physicians with treatments for rheumatoid arthritis: A population-based survey in China. Patient Prefer. Adher.14, 1037–1047 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Data will be disclosed upon a reasonable request from the corresponding author.