Abstract

Background/Aims:

The reuse of clinical trial data available through data-sharing platforms has grown over the past decade. Several prominent clinical data-sharing platforms require researchers to submit formal research proposals before granting data access, providing an opportunity to evaluate how published analyses compare with initially proposed aims. We evaluated the concordance between the included trials, study objectives, endpoints, and statistical methods specified in researchers’ clinical trial data use request proposals to four clinical data-sharing platforms and their corresponding publications.

Methods:

We identified all unique data request proposals with at least one corresponding peer-reviewed publication as of 3/31/2023 on four prominent clinical trial data sharing request platforms (Vivli, ClinicalStudyDataRequest.com [CSDR], the Yale Open Data Access [YODA] Project, and Supporting Open Access to Researchers–Bristol Myers Squibb [SOAR-BMS]). When data requests had multiple publications, we treated each publication-request pair as a unit. For each pair, the trials requested and analyzed were classified as fully concordant, discordant, or unclear, whereas the study objectives, primary and secondary endpoints, and statistical methods were classified as fully concordant, partially concordant, discordant, or unclear. For Vivli, CSDR, and SOAR-BMS, endpoints of publication-request pairs were not compared because the data request proposals on these platforms do not consistently report this information.

Results:

Of 117 Vivli publication-request pairs, 76 (65.0%) were fully concordant for the trials requested and analyzed, 61 (52.1%) for study objectives, and 57 (48.7%) for statistical methods; 35 (29.9%) pairs were fully concordant across the 3 characteristics reported by all platforms. Of 106 CSDR publication-request pairs, 66 (62.3%) were fully concordant for the trials requested and analyzed, 41 (38.7%) for study objectives, and 35 (33.0%) for statistical methods; 20 (18.9%) pairs were fully concordant across the 3 characteristics. Of 65 YODA Project publication-request pairs, 35 (53.8%) were fully concordant for the trials requested and analyzed, 44 (67.7%) for primary study objectives, and 25 (38.5%) for statistical methods; 15 (23.1%) pairs were fully concordant across the 3 characteristics. In addition, 26 (40.0%) and 2 (3.1%) YODA Project publication-request pairs were concordant for primary and secondary endpoints, respectively, such that only 1 (1.5%) YODA Project publication-request pair was fully concordant across all 5 characteristics reported. Of 3 SOAR-BMS publication-request pairs, 1 (33.3%) was fully concordant for the trials requested and analyzed, 2 (66.6%) for primary study objectives, and 2 (66.6%) for statistical methods; 1 (33.3%) pair was fully concordant across all 3 characteristics reported by all platforms.

Conclusion:

Across 4 clinical data sharing platforms, data request proposals were often discordant with their corresponding publications, with only 25% concordant across all three key proposal characteristics reported by each platform. Opportunities exist for investigators to describe any data sharing request proposal deviations in their publications and for platforms to enhance the reporting of key study characteristic specifications.

Keywords: Clinical trials, transparency, data sharing

Introduction

Over the past decade, efforts to facilitate wider access to clinical trial data, including summary level data (e.g., protocols, clinical study reports, and publications) and raw study data (i.e., individual patient-level data [IPD]), have heightened.1,2,3,4 Various stakeholders have increasingly recognized the benefits of data sharing,1, 3–6 including its potential to enhance the credibility of scientific research,7 reduce duplicative experimentation, maximize the contributions of human subjects who participate in trials, and allow for secondary analyses.8, 9 To foster responsible data use, several clinical study data-sharing platforms have emerged that require external researchers, who were not involved in the design or conduct of the original trial, to submit formal data request proposals before providing access to the clinical study data for secondary analyses, which may involve developing/validating methods, sub-group or replication analyses, or meta-analyses.8, 10–12 While the specificity of information required for these proposals varies across platforms,11, 13 such as whether to explicitly outline study objectives, primary and secondary endpoints, and/or statistical methods, these a priori research proposals are potentially important mechanisms for enhancing research transparency. These data request proposals also provide a unique opportunity to evaluate how published analyses compare with initially proposed aims and the degree to which any deviance is noted in peer-reviewed publications.

Previous studies have documented discrepancies between the objectives, endpoints, and statistical methods described in protocols or registrations and corresponding published reports of clinical trials and meta-analyses.14 For instance, an early examination of the consistency between clinical trial protocols and published reports of randomized trials approved by Scientific-Ethical Committees for Copenhagen and Frederiksberg found that nearly two-thirds had primary outcomes that were changed, later introduced, or omitted in the published report.15 Subsequent studies comparing ClinicalTrials.gov registrations and linked peer-reviewed publications across various fields have demonstrated similar findings,16,17,18 with recent estimates suggesting that approximately three-fourths of phase III trial registrations and publications contain at least one discrepancy.19 Similar trends have been observed among systematic reviews with pre-registered protocols on PROSPERO, with evidence suggesting that nearly one-third of publication-protocol pairs have discordant primary outcomes.20 While these findings provide insight into the extent of discordance between the initial aims and published analyses of clinical trials and meta-analyses, less is known about the consistency between request proposals for secondary analyses of shared clinical study data and corresponding publications.

Concerns have been raised about the susceptibility of secondary analyses to selective reporting of statistically significant results.21, 22, 23, 24 Therefore, understanding whether and what changes are made to secondary analyses after submission of clinical trial data request proposals is important for evaluating current clinical trial data sharing efforts and whether additional mechanisms may be needed to signal the reasons for such changes to the larger research community. Accordingly, we evaluated the concordance between researchers’ request proposals to reuse clinical trial data from Vivli, ClinicalStudyDataRequest.com (CSDR), the Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project, and the Supporting Open Access to Researchers–Bristol Myers Squibb (SOAR–BMS) initiative and their corresponding publications, focusing our comparisons on the specific trials requested and analyzed, specified study objectives, primary and secondary endpoints, and statistical methods.

Methods

The data-sharing platforms were selected based on size, clinical relevance, public availability of prespecified data request proposals, and availability of linked corresponding publications: Vivli, CSDR, the YODA Project, and SOAR–BMS (Table 1).11 Although the Duke Clinical Research Institute (DCRI) also shares data from the Duke Databank for Cardiovascular Disease and has a catalog of clinical research data sets on SOAR–BMS, the details on accepted data request proposals are not publicly reported. We did not include Project Data Sphere and the Biological Specimen and Data Repository Information Coordinating Center (BioLINCC) run by the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute (NHLBI) because they do not publicly share their data request proposals and linked publications.

Table 1.

Prominent clinical trial data sharing platforms.

| Name | Program Description | Example data partners | Dates Active |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vivli—Center for Global Clinical Research Data | Independent non-profit organization that evolved from a project at the Multi-Regional Clinical Trials Center of Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard | Abbvie, Biogen, BioLINCC, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Critical Path Institute, CureDuchenne, Daiichi Sankyo, Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, Duke University, GSK, Harvard University, IMMPort, Johns Hopkins University, Johnson & Johnson, Lilly, Pfizer, Project Data Sphere, Regeneration, Roche, Takeda, Tempus, The Leona M. and Harry B. Helmsley Charitable Trust, UCB, and University of California San Francisco | 2018-Present |

| ClinicalStudyDataRequest.com (CSDR) | Consortium of clinical study sponsors and funders | Astellas, Bayer, Chungai, Eisai, GSK, Novartis, Ono, Roche, Sanofi, Shionogi DSP/Sunovion, UCB, ViiV, Cancer Research UK | 2014-Present |

| The Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project | Academic-based data sharing program run through Yale University | Johnson & Johnson, Medtronic, Inc., Queen Mary University of London, SIBONE, Inc. | 2011-Present |

| Supporting Open Access to Researchers–Bristol Myers Squibb (SOAR–BMS) | Academic-based data sharing program run through the Duke Clinical Research Institute (DCRI) | Bristol Myers Squibb | 2013–2020 (requests now processed through Vivli) |

Data extraction

Characteristics of data sharing platforms.

We identified all data request proposals with at least one corresponding peer-reviewed publication listed on each data-sharing platform website. We excluded any data request proposals where the public reports were not peer-reviewed (e.g., conference abstracts, dissertations, pre-prints, or other documents reporting study findings). For each platform, we only identified unique data request proposals, and data request proposals submitted for trials across multiple data-sharing platforms were attributed to the platform hosting the study data for a particular data request proposal (e.g., Johnson & Johnson lists studies on both the Vivli and YODA Project platforms. Vivli reviews data request proposals for data from multiple sponsors, while YODA reviews data request proposals for data from only Johnson & Johnson).

Identification of data request proposal characteristics.

For each data request proposal, we identified the trials requested, the number of requested trials, and the study objectives, which were consistently reported across platforms. For the YODA Project platform, we also reviewed a specific section of each data request proposal to determine the primary and secondary endpoints (i.e., ‘Primary and Secondary Measure(s) and how they will be categorized/defined for your study’). For Vivli, CSDR, and SOAR-BMS, primary and secondary endpoints of publication-request pairs were not compared because the data request proposals on these platforms do not consistently report this information, or when reported, the information is frequently reported without sufficient specificity to allow for reliable abstraction. Lastly, data proposals were reviewed to determine the overarching statistical methods, and we recorded key statistical tests and approaches specified in the statistical analysis plan or study design sections of each data request proposal.

Identification of publication characteristics.

For each peer-reviewed publication linked to a data request proposal, we first determined the trials analyzed by reviewing the methods or supplementary materials to identify the names of the trials requested from the data sharing platform and included in the analyses. In particular, we looked for any mention of the data sharing platform, corresponding data request proposal, or individual study names or identifiers (e.g., ClinicalTrials.gov NCT numbers). We then reviewed the title, abstract, and introduction to determine the study objectives. Next, for publications from the YODA Project platform, we reviewed the abstract, methods, and results sections for specific terms to identify the primary and secondary endpoints (i.e., ‘endpoint’, ‘outcome’, ‘primary’, ‘secondary’). If a publication did not differentiate between primary and secondary endpoints, all study endpoints were classified as primary without any additional secondary endpoint. However, to be included in our evaluation, endpoints needed to be explicitly referred to as an ‘endpoint’ or ‘outcome’ in the manuscript. When the publication provided no clear endpoint information, we assigned a designation of ‘unclear’. For any publication where the study objective was to generate or test methods, endpoints were not recorded, as prespecified primary or secondary endpoints may not be relevant or reported. Finally, we reviewed the methods section to determine the overarching statistical methods, and we recorded any key statistical tests and approaches.

All data extraction was performed by one author (EV) and reviewed by a second author (JDW), with discrepancies reviewed by a third author (JSR).

Comparison of publication and request characteristics

For data request proposals with multiple publications, it was not feasible to evaluate whether multiple publications combined satisfied all objectives and analyses outlined in data request proposals (Appendix Table 1 in the Supplementary Material). Therefore, each publication was considered a unit that was compared to the corresponding data request proposal (i.e., a publication-request pair). From each publication-request pair, the trials requested and analyzed were classified as fully concordant if all the trials requested were included in the analyses described in the publications. Otherwise, trials were classified as discordant or unclear. The study objectives were classified as fully concordant (the same overarching objectives with only minor clarifications or changes, see Appendix Table 2 in the Supplementary Material), partially concordant (the same overarching objectives with additional or more specific objectives in the publication), discordant (completely different overarching objectives in the publication), or unclear (insufficient information to make a determination). For publication-request pairs from the YODA Project platform, primary and secondary endpoints were classified as fully concordant (i.e., the same domain, independent of ascertainment time or collection method), partially concordant (≥1 additional primary/secondary endpoint in publication that was not in the data request proposal), discordant (≥1 primary endpoint dropped or converted to a secondary endpoint, secondary endpoint dropped or converted to a primary endpoint, or primary and secondary endpoints swapped), or unclear. Although endpoints are typically defined across five elements (i.e., domain, specific measurement, specific metric, method of aggregation, and time-points), our approach was deliberately lenient, recognizing that these characteristics may not always be reported in the data request proposals and that certain adjustments may be necessary and justified once researchers gain access to the data.25 Statistical methods were classified as concordant (the same primary statistical methods with additional components, including descriptive analyses, sensitivity analyses, or subgroup analyses), partially concordant (≥1 additional primary statistical methods that were not disclosed in the data request proposal), discordant (completely different primary statistical methods used), and unclear (not enough information was provided to make a determination). All concordance determinations were discussed with a second investigator (JDW).

Statistical analyses

We conducted descriptive analyses of the main characteristics. Data were collected using Google forms and analyzed using Excel (version 16.39). All data were accessed between 1 January and 31 May 2023. This study was conducted using publicly reported, nonclinical data and did not require institutional review board approval or informed consent.

Results

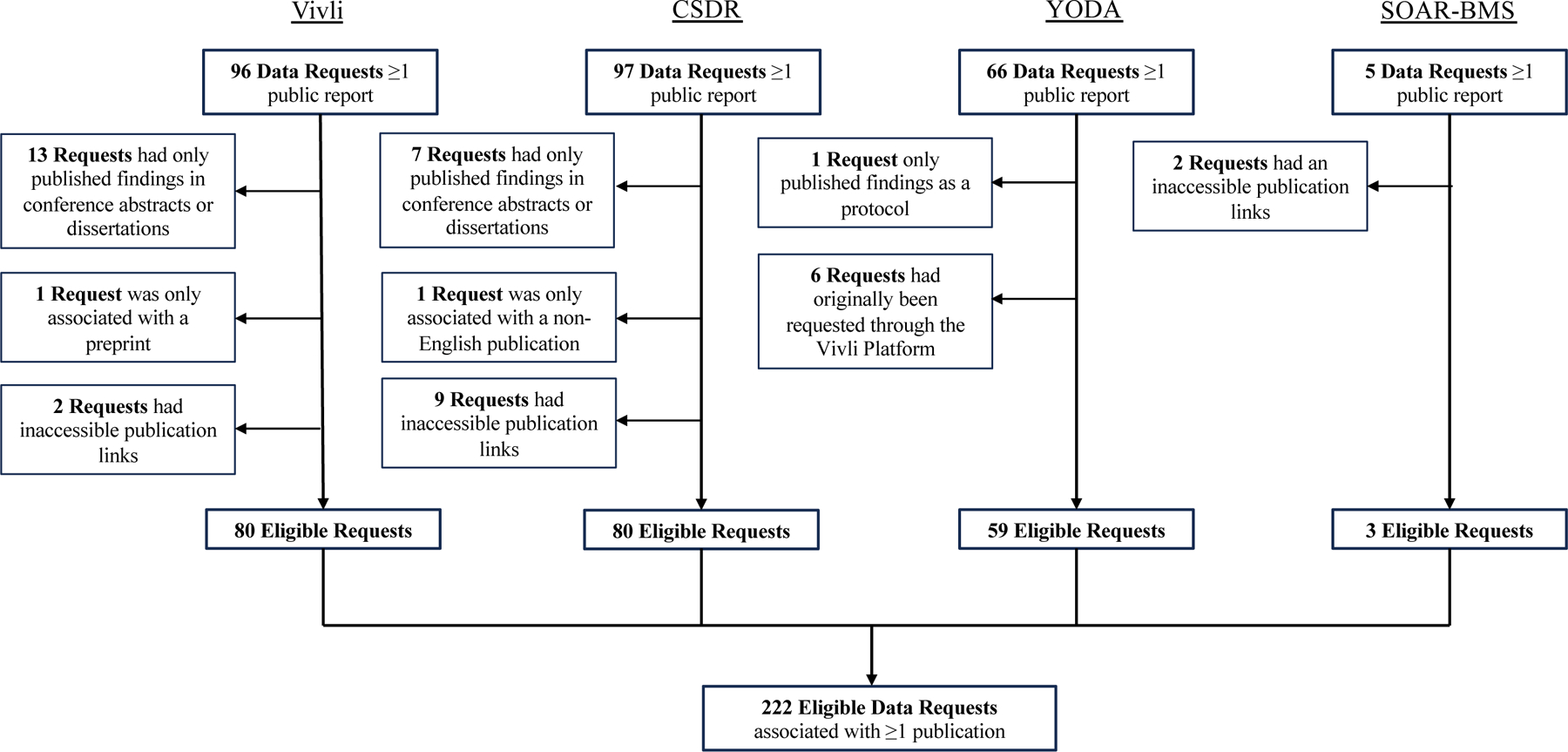

As of May 31, 2023, Vivli listed 96 data request proposals with at least one public report of study findings. Of these, we excluded 13 data request proposals that only had published conference abstracts, 2 with inaccessible publication links, and 1 with a preprint (Figure 1). The 80 eligible data request proposals had a total of 117 peer-reviewed publications, resulting in 117 publication-request pairs. As of January 15, 2023, CSDR listed 97 data request proposals with at least one public report. Of these, we excluded 7 data request proposals that only had published conference abstracts or dissertations, 1 that only had non-English language publications, and 9 that only had inaccessible publication links. The 80 eligible data request proposals had a total of 106 peer-reviewed publications, resulting in 106 publication-request pairs. As of January 18, 2023, the YODA Project listed 66 data requests proposals with at least one public report. Of these, we excluded 6 data request proposals that had been originally submitted through the Vivli platform and 1 data request proposal that only had a published protocol. The 59 eligible data request proposals had a total of 65 peer-reviewed publications, resulting in 65 publication-request pairs. As of January 15, 2023, SOAR-BMS listed 5 data request proposals with least one public report. Of these, we excluded 2 data request proposal that had inaccessible publication links. The eligible 3 requests had a total of 3 peer-reviewed publications.

Figure 1.

Data request eligibility by platform.

Vivli

Among the 117 publication-request pairs, there were 76 (65.0%) where all trials requested were included in the published analyses (Table 2). Among the 40 (34.2%) discordant pairs, all had publications that included fewer trials than the number specified in the data request proposal. There was 1 (0.9%) published manuscript did not disclose the trials included in the analysis. There were 61 (52.1%) pairs with fully concordant study objectives, 41 (35.0%) with partially concordant study objectives, and 11 (9.4%) with discordant study objectives. Among the 117 publication-request pairs, 57 (48.7%) pairs had fully concordant and 32 (27.4%) had partially concordant statistical methods; 23 (19.7%) were discordant and 5 (4.3%) were unclear. Overall, 35 (29.9%) publication-request pairs were fully concordant across all 3 of the request characteristics reported by all platforms.

Table 2.

Concordance between data publications and associated requests across all platforms.

| Platform (No. pairs) | Vivli (n=117) | CSDR (n=106) | YODA (n=65) | SOAR–BMS (n=3) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Characteristics | Publication-Request Pairs, No. (%) | Publication-Request Pairs, No. (%) | Publication-Request Pairs, No. (%) | Publication-Request Pairs, No. (%) |

|

Trials requested and analyzed |

||||

| Fully concordant | 76 (65.0) | 66 (62.3) | 35 (53.8) | 1 (33.3) |

| Discordant | 40 (34.2) | 29 (27.4) | 29 (44.6) | 1 (33.3) |

| Greater number of trials listed in the data request | 40 (100.0) | 28 (96.6) | 29 (100.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Greater number of trials listed in the publication | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (100.0) |

| Unclear number of trials in the publication | 1 (0.9) | 11 (10.4) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (33.3) |

| Study objective(s) | ||||

| Fully concordant | 61 (52.1) | 41 (38.7) | 44 (67.7) | 2 (66.7) |

| Partially concordant | 41 (35.0) | 36 (34.0) | 14 (21.5) | 1 (33.3) |

| Discordant | 11 (9.4) | 29 (27.4) | 7 (10.8) | 0 (0.0) |

| Unclear | 4 (3.4) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Primary endpoint(s) a | ||||

| Undefined primary endpoints | - | - | 18 (27.7) | - |

| Methods publications | - | - | 17 (94.4) | - |

| Unclear or no primary endpoints disclosed | - | - | 1 (5.6) | - |

| Defined primary endpoints | - | - | 47 (72.3) | - |

| Fully concordant | - | - | 26 (55.3) | - |

| Partially concordant | - | - | 6 (12.8) | - |

| Discordantb | - | - | 15 (32.0) | - |

| Secondary endpoint(s) a | - | - | ||

| Undefined secondary endpoints | - | - | 40 (61.5) | - |

| Methods publications | - | - | 17 (42.5) | - |

| Unclear or no secondary endpoints disclosed | - | - | 23 (57.5) | - |

| Defined secondary endpoints | - | - | 25 (38.5) | - |

| Fully concordant | - | - | 2 (8.0) | - |

| Partially concordant | - | - | 3 (12.0) | - |

| Discordantb | - | - | 20 (80.0) | - |

| Statistical Methods | ||||

| Fully Concordant | 57 (48.7) | 35 (33.0) | 25 (38.5) | 2 (66.7) |

| Partially Concordant | 32 (27.4) | 25 (23.6) | 15 (23.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Discordant | 23 (19.7) | 42 (39.6) | 24 (36.9) | 0 (0.0) |

| Unclear | 5 (4.3) | 4 (3.8) | 1 (1.5) | 1 (33.3) |

Primary and secondary endpoints not consistently reported on CSDR and SOAR–BMS data requests and were not captured by researchers.

At least one primary endpoint dropped or converted to a secondary endpoint, secondary endpoint dropped or converted to a primary endpoint, or primary and secondary endpoints swapped.

CSDR

Among the 106 publication-request pairs, there were 66 (62.3%) pairs where all the trials requested were included in the published analyses (Table 2). Among the 29 (27.4%) discordant pairs, 28 (96.6%) had publications that included fewer trials than the number of trials specified in the data request proposals. There were 11 (10.4%) publications that did not disclose the trials included in the analysis. There were 41 (38.7%) publication-request pairs with fully concordant study objectives, 36 (34.0%) had partially concordant study objectives, and 29 (27.4%) had discordant study objectives (Table 2). Primary and secondary endpoints of publication-request pairs were not compared because CSDR data request proposals do not consistently report or require this information. Among the 106 publication-request pairs, 35 (33.0%) had fully concordant statistical methods and 25 (23.6%) with partially concordant statistical methods; 42 (39.6%) were discordant and 4 (3.8%) were unclear. Overall, 20 (18.9%) of the publication-request pairs were fully concordant across all 3 of the request characteristics reported by all platforms.

The YODA Project

Among the 65 publication-request pairs, there were 35 (53.8%) pairs where all the trials requested were included in the published analyses (Table 2). Among the 29 (44.6%) discordant pairs, all of them had publications that used fewer trials than the number specified in the data request proposal. There was 1 (1.5%) pair where the did not report the trials included in the analyses. There were 44 (67.7%) pairs with fully concordant, 14 (21.5%) partially concordant, and 7 (10.8%) discordant study objectives.

There were 17 (26.2%) publication-request pairs focused on generating or testing methods, where prespecified primary or secondary endpoints may not be relevant or reported. There was one pair with unclear or no primary endpoints disclosed. Among the 47 remaining pairs with defined primary endpoints, 26 (55.3%) had fully concordant primary endpoints, 6 (12.8%) had partially concordant primary endpoints (i.e. the publication contained all primary endpoints reported in the data request proposal, along with additional primary endpoints), and 15 (32.0%) had discordant primary endpoints (i.e. the publication did not contain all primary endpoints disclosed in the data request proposal). There were 23 (35.4%) pairs where the publications did not clearly disclose any secondary endpoints. Among the 25 remaining pairs with defined secondary endpoints, 2 (8.0%) had fully concordant secondary endpoints, 3 (12.0%) had partially concordant secondary endpoints, and 20 (80.0%) had discordant secondary endpoints.

Among all 65 publication-request pairs, 25 (38.5%) had fully concordant and 15 (23.1%) had partially concordant statistical methods; 24 (36.9%) were discordant and 1 (1.5%) was unclear.

Overall, 15 (23.1%) of the publication-request pairs were fully concordant across all 3 of the request characteristics reported by all platforms. Only 1 (1.5%) publication-request pair was fully concordant across all 5 of the request characteristics, when also considering primary and secondary endpoints.

SOAR–BMS

Among the 3 publication-request pairs, there was 1 (33.3%) pair where all trials requested were included in the published analyses (Table 2). There was 1 (33.3%) discordant pair and 1 (33.3%) pair where the publication did not disclose the trials included in the analysis. There were 2 (66.7%) pairs that had fully concordant study objectives and 1 (33.3%) pair that had partially concordant study objectives. Primary and secondary endpoints of publication-request pairs were not compared because SOAR–BMS data request proposals do not consistently report or require this information. There were 2 (66.7%) pairs with fully concordant statistical methods and 1 (33.0%) pair for which the statistical methods were unclear. Overall, 1 of the publication-request pair was fully concordant across all 3 of the request characteristics reported by all platforms.

Discussion

In this cross-sectional study of the concordance between researchers’ requests to reuse clinical trial data from prominent data sharing platforms and their corresponding publications, we found that data request proposals were often discordant with their corresponding publications, with only one quarter were concordant across three key proposal characteristics reported by each platform. While most publication-request pairs across platforms were either fully or partially concordant in terms of primary study objectives, the trials request and analyzed and statistical methods were often discordant. While clinical data-sharing platforms have facilitated access to thousands of trial datasets for secondary analyses and have resulted in hundreds of publications, our findings suggest that opportunities exist for investigators to describe any data request proposal deviations in their publications and for platforms to enhance the reporting of key study characteristic specifications.

Although we found that many publication-request pairs had discordant trials requested and analyzed and statistical methods, it is unclear how often these differences reflect changes that are necessary and justified once researchers gain access to the data. For instance, investigators may discover that specific trials do not meet their eligibility criteria after attempting to conduct their proposed analyses. For certain platforms, it is also difficult to establish how many proposal requests had statistical methods that were updated after the study had been completed. Although proposal requests on CSDR platform contain a separate field for ‘Statistical Analysis Plan‘, this section is only posted on CSDR after the research is published. While one would suspect that platforms allowing for statistical analysis sections to be updated after the publication of a manuscript would lead to more concordant classifications in the statistical analysis section, we did not find that CSDR had the highest proportion of publication-request pairs with fully or partially concordant statistical methods.

The ability to determine whether discordances reflect appropriate protocol modifications, exploratory analyses, or potential selective reporting is contingent on data-sharing platforms consistently requiring data requestors to prespecify the trials requested, study objectives, primary and secondary outcomes, and statistical methods.26 The YODA Project was the only examined platform that consistently required requestors to prespecify their primary and secondary endpoints and publicly reported this information on their platforms. We found that approximately one-third of the YODA Project publication-request pairs with defined endpoints had discordant primary endpoints and 80% had discordant secondary endpoints. Overall, these findings mirror the results from previous studies evaluating the extent of selective reporting in publications of clinical trials with associated ClinicalTrial.gov registrations or meta-analyses with pre-registered protocols on PROSPERO.14, 17, 18, 20

This study highlights opportunities to enable external evaluators, including peer reviewers, to better determine whether the findings in publications of secondary analyses of clinical trial data should be considered hypothesis-driven or largely exploratory. First, data-sharing platforms should standardize the format of their data request proposal forms to include structured fields for several important study design characteristics, including specific trials requested, study objectives, primary and secondary endpoints, and statistical methods. Providing and requiring structured fields will make it easier for researchers to design their analyses and for external investigators to evaluate potential changes. Second, in addition to publicly reporting all approved data request proposals on their websites, data-sharing platforms could require researchers to report any major changes made to the prespecified study design characteristics outlined in the data request proposal after gaining access to trial data. Third, publications reporting the results of secondary analyses of shared clinical trial data should clearly describe the reasons for any changes made to their prespecified data request proposals. Moreover, the original data request proposals should be included as publicly available supplementary materials at the time of journal submission. Lastly, opportunities exist to develop a consensus document and structured template for planning and reporting on the secondary analyses of shared clinical trial data. While these recommendations may not fully address the discordance between publication-request pairs, they can help improve transparency and minimize selective reporting.

The recommendations to standardize the data request proposal forms can also help inform the National Institutes of Health (NIH) in establishing standards to ensure responsible data stewardship, allowing external investigators to register their secondary analyses using short data request proposal forms that require them to prespecify the trials requested, the study objectives, primary and secondary outcomes, and statistical methods.26

Limitations

This study had several limitations. First, there were 21 data request proposals with multiple corresponding peer reviewed publications. For these, it was not feasible to evaluate if all analyses proposed in the data request proposals were reported across the separate publications. Instead, we evaluated each associated publication individually as a publication-request pair. Given the inconsistent level of detail provided in data request proposals and publications, it was difficult to make definitive determinations regarding how analyses and results were divided across publications, especially as certain publications dropped and/or expanded upon their planned analyses. However, all recorded characteristics and resulting concordance determinations were reviewed by a second reviewer (JDW) for validity. Lastly, we relied on public information from each platform’s website. Therefore, we did not include platforms that did not make data request proposals and corresponding publications publicly available on their websites (i.e., Project Data Sphere and BioLINCC). It is unclear how our findings would have changed had these platforms published their data sharing requests. Additionally, we were unable to account for any communication between researchers and platforms or any changes made to proposal requests after the study was completed that were not publicly disclosed.

Conclusion

In this evaluation of the concordance between researchers’ requests to reuse clinical trial data from Vivli, ClinicalStudyDataRequest.com (CSDR), the Yale Open Data Access (YODA) Project, and the Supporting Open Access to Researchers–Bristol Myers Squibb (SOAR–BMS) initiative and their corresponding publications, we found that data request proposals were often discordant with their corresponding publications, with only one quarter concordant across all three key proposal characteristics reported by each platform. While some deviations may reflect how a researcher’s understanding of data changes once they gain access to the information requested, our findings suggest that opportunities exist to improve the information about data requests reported by data-sharing platforms and to enhance the transparency of reporting in publications of secondary analyses of shared clinical trial data.

Supplementary Material

Funding

The author(s) disclosed receipt of the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Dr. Wallach is supported by the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism of the National Institutes of Health under award 1K01AA028258. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of conflicting interests

The author(s) declared the following potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: J.S.R., C.P.G., J.D.R., H.M.K., and J.D.W. are members of the YODA Project leadership team and receive support from Johnson & Johnson to support data sharing through the YODA project. J.S.R. is supported by the FDA, Arnold Ventures, AHRQ, and NHLBI and was an expert witness at the request of Relator’s attorneys, the Greene Law Firm, in a qui tam suit alleging violations of the False Claims Act and Anti-Kickback Statute against Biogen Inc. that was settled in September 2022. CPG has received research funding from the NCCN Foundation (Astra-Zeneca) and Genentech. K.C. and S.B. are current employees and shareholder of Johnson & Johnson. J.D.R receives support from the FDA and Arnold Ventures. J.W. is a former employee and current shareholder of Johnson & Johnson and an Independent Board of Director and Shareholder for Becton Dickinson and Structure Therapeutics. J.W. is also a consultant for Galapagos NV. H.M.K. received options for Element Science and Identifeye and payments from F-Prime for advisory roles. He is a co-founder of and holds equity in Hugo Health, Refactor Health, and ENSIGHT-AI. He is associated with research contracts through Yale University from Janssen, Kenvue, and Pfizer. J.D.W. is supported by the FDA and Arnold Ventures. JDW previously served as a consultant to Hagens Berman Sobol Shapiro LLP and Dugan Law Firm APLC.

Data sharing

Data will be shared on osf.io upon publication.

References

- 1.Medicine Io. Sharing Clinical Trial Data: Maximizing Benefits, Minimizing Risk. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2015, p.304. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ohmann C, Banzi R, Canham S, et al. Sharing and reuse of individual participant data from clinical trials: principles and recommendations. BMJ Open 2017; 7: e018647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kiley R, Peatfield T, Hansen J, et al. Data Sharing from Clinical Trials — A Research Funder’s Perspective. N Engl J Med 2017; 377: 1990–1992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.The World Health Organization. Developing Global Norms for Sharing Data and Results during Public Health Emergencies, http://www.who.int/medicines/ebola-treatment/data-sharing_phe/en/ (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.2023 NIH Data Management and Sharing policy, https://oir.nih.gov/sourcebook/intramural-program-oversight/intramural-data-sharing/2023-nih-data-management-sharing-policy (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hudson KL and Collins FS. Sharing and Reporting the Results of Clinical Trials. JAMA 2015; 313: 355–356. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gøtzsche PC. Strengthening and Opening Up Health Research by Sharing Our Raw Data. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012; 5: 236–237. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ross JS and Krumholz HM. Ushering in a New Era of Open Science Through Data Sharing: The Wall Must Come Down. JAMA 2013; 309: 1355–1356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Macleod MR, Michie S, Roberts I, et al. Biomedical research: increasing value, reducing waste. Lancet 2014; 383: 101–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross JS, Waldstreicher J, Bamford S, et al. Overview and experience of the YODA Project with clinical trial data sharing after 5 years. Sci Data 2018; 5: 180268. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Vazquez E, Gouraud H, Naudet F, et al. Characteristics of available studies and dissemination of research using major clinical data sharing platforms. Clin Trials 2021; 18: 657–666. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Berlin JA, Morris S, Rockhold F, et al. Bumps and bridges on the road to responsible sharing of clinical trial data. Clin Trials 2014; 11: 7–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Krumholz HM, Gross CP, Blount KL, et al. Sea change in open science and data sharing: leadership by industry. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2014; 7: 499–504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.TARG Meta-Research Group and Collaborators. Estimating the prevalence of discrepancies between study registrations and publications: a systematic review and meta-analyses. BMJ Open 2023; 13: e076264. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chan A-W, Hróbjartsson A, Haahr MT, et al. Empirical Evidence for Selective Reporting of Outcomes in Randomized TrialsComparison of Protocols to Published Articles. JAMA 2004; 291: 2457–2465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Florez MA, Jaoude JA, Patel RR, et al. Incidence of Primary End Point Changes Among Active Cancer Phase 3 Randomized Clinical Trials. JAMA Netw Open 2023; 6(5): e2313819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hartung DM, Zarin DA, Guise JM, et al. Reporting discrepancies between the ClinicalTrials.gov results database and peer-reviewed publications. Ann Intern Med 2014; 160: 477–483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Anderson ML, Chiswell K, Peterson ED, et al. Compliance with results reporting at ClinicalTrials.gov. N Engl J Med 2015; 372: 1031–1039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Talebi R, Redberg RF and Ross JS. Consistency of trial reporting between ClinicalTrials.gov and corresponding publications: one decade after FDAAA. Trials 2020; 21: 675. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tricco AC, Cogo E, Page MJ, et al. A third of systematic reviews changed or did not specify the primary outcome: a PROSPERO register study. J Clin Epidemiol 2016; 79: 46–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krumholz HM. Documenting the Methods History. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes 2012; 5: 418–419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Baldwin JR, Pingault J-B, Schoeler T, et al. Protecting against researcher bias in secondary data analysis: challenges and potential solutions. Eur J Epidemiol 2022; 37: 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Luijken K, Dekkers OM, Rosendaal FR, et al. Exploratory analyses in aetiologic research and considerations for assessment of credibility: mini-review of literature. BMJ 2022; 377: e070113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simmons JP, Nelson LD and Simonsohn U. False-Positive Psychology:Undisclosed Flexibility in Data Collection and Analysis Allows Presenting Anything as Significant. Psychol Sci 2011; 22: 1359–1366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Saldanha IJ, Dickersin K, Wang X, et al. Outcomes in Cochrane systematic reviews addressing four common eye conditions: an evaluation of completeness and comparability. PLoS One 2014; 9: e109400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ross JS, Waldstreicher J and Krumholz HM. Data Sharing — A New Era for Research Funded by the U.S. Government. N Engl J Med 2023; 389(26):2408–2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.