Summary

Increasing atmospheric CO2 levels have a variety of effects that can influence plant responses to microbial pathogens. However, these responses are varied, and it is challenging to predict how elevated CO2 (eCO2) will affect a particular plant–pathogen interaction. We investigated how eCO2 may influence disease development and responses to diverse pathogens in the major oilseed crop, soybean.

Soybean plants grown in ambient CO2 (aCO2, 419 parts per million (ppm)) or in eCO2 (550 ppm) were challenged with bacterial, viral, fungal, and oomycete pathogens. Disease severity, pathogen growth, gene expression, and molecular plant defense responses were quantified.

In eCO2, plants were less susceptible to Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea (Psg) but more susceptible to bean pod mottle virus, soybean mosaic virus, and Fusarium virguliforme. Susceptibility to Pythium sylvaticum was unchanged, although a greater loss in biomass occurred in eCO2. Reduced susceptibility to Psg was associated with enhanced defense responses. Increased susceptibility to the viruses was associated with reduced expression of antiviral defenses.

This work provides a foundation for understanding how future eCO2 levels may impact molecular responses to pathogen challenges in soybean and demonstrates that microbes infecting both shoots and roots are of potential concern in future climatic conditions.

Keywords: bean pod mottle virus, carbon dioxide, Fusarium virguliforme, Glycine max, plant immunity, Pseudomonas syringae, Pythium sylvaticum, soybean mosaic virus

Short abstract

See also the Commentary on this article by Sanchez‐Lucas & Luna, 246: 2380–2383.

Introduction

Atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) levels are steadily rising and by some estimates, are predicted to increase to 550 parts per million (ppm) or more by mid‐century. Increasing CO2 levels, in combination with more extreme and unpredictable weather events, are expected to have significant impacts on global food security. The majority of plants on Earth use C3 photosynthesis, with relative atmospheric [O2] and [CO2] favoring photorespiration or photosynthesis, respectively (Pinto et al., 2014). As a result, elevated CO2 (eCO2) stimulates photosynthesis, generally increasing plant biomass and yield, providing a potential benefit to crop production (Dusenge et al., 2019; Ainsworth & Long, 2021). However, this CO2 ‘fertilization effect’ depends on a number of factors, including water and nutrient availability and optimal growth temperatures (Ainsworth & Long, 2021). Moreover, suppression of photorespiration, once thought to be a wasteful process, has been associated with poor growth (Timm & Bauwe, 2013), lower nutrient and protein content (Taub et al., 2008; Broberg et al., 2017), and reduced abiotic stress tolerance (Voss et al., 2013) under ambient atmospheric conditions (aCO2).

Another possible impact of eCO2 is changes in the occurrence and severity of plant diseases. Pests and diseases that affect plant quality and yield pose one of the greatest challenges to crop production and are responsible for 17–30% of total yield losses of major crops (Savary et al., 2019). Climate change is expected to cause latitudinal shifts in disease pressure associated with the migration of important plant pathogens to new geographic regions (Bebber et al., 2013; Chakraborty, 2013; Raza and Bebber, 2022) as well as changes in pathogen virulence or aggressiveness (Pangga et al., 2007; Lake & Wade, 2009; Aguilar et al., 2015; Singh et al., 2023). Additionally, eCO2 has been demonstrated to alter interactions between plants and their attackers through changes in plant architecture, physiology, and molecular defense responses (Velásquez et al., 2018; Bazinet et al., 2022).

Plant disease development relies on three factors: a susceptible plant host, a virulent pathogen, and environmental conditions conducive to infection (Stevens, 1960; Grulke, 2011). Over the past decade, tremendous advances have been made in our understanding of plant–microbe interactions (Ngou et al., 2022; Petre et al., 2022); however, it is still not well‐understood how changes in environmental conditions shape these interactions. Several mechanisms by which eCO2 affects defense responses have been reported, including changes in leaf nutrition (Ryalls et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2016), stomatal density (Li et al., 2015; Zhou et al., 2017), host metabolism (Matros et al., 2006; Ode et al., 2014), and redox homeostasis (Mhamdi & Noctor, 2016; Noctor & Mhamdi, 2017; Foyer & Noctor, 2020; Ahammed & Li, 2022). Altered levels of defense‐related phytohormones, salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene (ET), have also been reported (Zhang et al., 2015; Pan et al., 2019; Zhou et al., 2019). In general, constitutive and/or pathogen‐induced SA levels have been reported to be higher in the foliar tissues of C3 plants grown under eCO2 (Bazinet et al., 2022), suggesting that plants could be more resistant to viral and biotrophic pathogens (Vlot et al., 2009; Murphy et al., 2020). However, the extent and directionality of these responses are highly variable between studies (Bazinet et al., 2022), which may reflect species, cultivar, or ecotype‐specific CO2 adaptations, as well as differences in additional environmental growth conditions. For example, in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), eCO2 increased SA biosynthesis, and plants displayed higher resistance to leaf curl virus, tobacco mosaic virus, and the hemibiotrophic bacterial pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato (PstDC3000), but were more susceptible to the necrotrophic fungal pathogen Botrytis cinerea (Huang et al., 2012; Zhang et al., 2015). By contrast, eCO2 increased JA‐dependent responses in Arabidopsis (Arabidopsis thaliana), enhancing resistance to B. cinerea and reducing resistance to PstDC3000 (Zhou et al., 2019). These discrepancies highlight the need for direct investigations of pathosystems involving important crop species rather than relying on generalized information from model systems.

Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr.) is the most widely grown protein and oilseed crop, accounting for c. 329 million tons of global crop production in 2022 (http://www.worldagriculturalproduction.com/). The effect of eCO2 on soybean physiology has been investigated at various scales (Ainsworth & Long, 2021; Li et al., 2021). In general, soybean yield potential and root nodule mass increase under eCO2 (Dermody et al., 2008) with no significant impact on plant nutrient or protein content (Myers et al., 2014). eCO2 has also been associated with changes in leaf endophyte communities (Christian et al., 2021; Gonçalves et al., 2021), rhizospheric bacterial communities (Yu et al., 2016), and responses to herbivore attack (Casteel et al., 2008; O'Neill et al., 2010; Paulo et al., 2020). However, only one study has reported the effect of predicted future CO2 atmospheric conditions (550 ppm) on soybean diseases (downy mildew, brown spot, and sudden death syndrome (SDS)) by monitoring the incidence and severity of some naturally occurring diseases at the Soybean Free Air Concentration Enrichment (SoyFACE) facility (Eastburn et al., 2010). As soybean is susceptible to numerous economically important pathogens, including bacteria, fungi, oomycetes, viruses, and nematodes that are expected to be affected by climate change (Whitham et al., 2016; Roth et al., 2020), a formal investigation of how eCO2 impacts susceptibility to diverse pathogens is needed. Moreover, the effects of eCO2 on molecular defense responses has not yet been investigated in this species.

In this study, we assessed the effects of eCO2 on soybean defense response in plants grown under the current [aCO2] of 419 ppm vs an [eCO2] of 550 ppm. Using the soybean–P. syringae pathosystem, we assessed innate immune responses and disease susceptibility and conducted transcriptomic analyses to gain a global understanding of how eCO2 levels affect interactions in this pathosystem. We also conducted infection experiments using two foliar viral pathogens, bean pod mottle virus (BPMV) and soybean mosaic virus (SMV), and two filamentous root pathogens, Fusarium virguliforme and Pythium sylvaticum, and demonstrate that eCO2 exerts differential effects on interactions with these diverse microbial pathogens. Our work provides a foundation for future studies investigating the molecular interplay that regulates defense responses in eCO2 and identifies pathogens of potential concern in predicted future atmospheric conditions.

Materials and Methods

Plant growth and maintenance

Soybean (Glycine max (L.) Merr. cv Williams 82) plants were grown in chambers at the Iowa State University Enviratron facility (Bao et al., 2019) with lighting, humidity, and temperature conditions as illustrated in Supporting Information Fig. S1. [CO2] maintained at 419 ppm represented aCO2 and 550 ppm represented future atmospheric conditions (eCO2) (Jaggard et al., 2010). For each condition, three replicate growth chambers were used to provide biological replicates. Plants were grown in LC‐1 potting soil mix (Sungro, Agawam, MA, USA) and fertilized weekly with 15‐5‐15 Cal‐Mag Special (G99140; Peters Excel, St. Louis, MO, USA).

Physiological measurements

Shoot biomass, photosystem II (PSII) activity (quantum yield of fluorescence; ΦPSII activity), and stomatal conductance (gas exchange rate; g sw) were measured for 15 plants per CO2 treatment. ΦPSII and g sw were obtained using a LI‐600 Portable System (LI‐COR Biosciences, Lincoln, NE, USA) during the VC‐V4 growth stages (Kumudini, 2010). ΦPSII measurements were conducted on the adaxial surface of unifoliate leaves of 14‐d‐old plants and the newest fully expanded trifoliolate leaves of 3‐ and 5‐wk‐old plants. g sw measurements were simultaneously collected from the abaxial surface. At 21 d after planting (dap), leaves were collected from eight plants per treatment and chamber, yielding three biological replicates per treatment for QuantSeq 3′ mRNA‐Seq analyses (48 samples for QuantSeq dataset 1). Samples were collected between 09:00 h and 10:00 h for all replicates. At 35 dap, shoots were collected to determine fresh weight and dry weight.

Stomatal density, aperture, and index measurements

Stomatal density and aperture measurements were assessed from 10 leaf samples, while stomatal index measurements were taken from five leaf samples for each CO2 treatment at 21 dap. Impressions were made from the abaxial leaf surfaces using clear nail varnish (Ceulemans et al., 1995). Stomata were imaged using light microscopy, and counted in three randomly selected fields of view per leaf sample. Stomatal aperture and stomatal index measurements were conducted as described (Sultana et al., 2021; Zhu et al., 2021).

Reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction and quantitative polymerase chain reaction analyses

Total RNA was isolated from c. 50 mg of leaf tissue using TRIzol Reagent (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Subsequently, 2 μg of RNA was reverse transcribed using the Maxima First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific). Reverse transcription quantitative PCR (RT‐qPCR) was conducted using 2× PrimeTime Gene Expression Master Mix (Integrated DNA Technologies, Coralville, IA, USA) and multiplexed probes designed for Pathogenesis‐Related Protein 1 (PR1) (Glyma.13G251600), Kunitz Trypsin Inhibitor 1 (KTI1) (Glyma.08G342000), BPMV, or SMV (Table S1). Expression of Dicer‐Like 2 (DCL2) (Glyma.09 g025300) and Argonaute 1 (AGO1) (Glyma.09 g167100) was assessed using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio‐Rad). F. virguliforme and P. sylvaticum were quantified in soybean roots at 14 and 35 dap, respectively. DNA was extracted using the CTAB method (Rogers & Bendich, 1994), and qPCR was performed using primers specific to each pathogen (Table S1). S‐phase kinase‐associated protein 1 (Skp1) (Glyma.08G211200) was used as an internal reference for all experiments (Beyer et al., 2021). Primers and probes were designed from cultivar Williams 82 reference sequence (version Wm82.a4.v1, Schmutz et al., 2010) using PrimerQuest Tool (Integrated DNA Technologies).

Immune signaling assays

Oxidative species production was monitored in 14‐d‐old soybean plants (Bredow et al., 2019) using leaf disks collected from 16 plants per CO2 treatment. The elicitor solution contained 100 μM luminol (Sigma‐Aldrich), 10 μg ml−1 horseradish peroxidase (Sigma‐Aldrich), with or without 100 nM flg22 (VWR International, Radnor, PA, USA). Chemiluminescence was quantified on a GloMax® plate reader (luminescence module; Promega) every 2 min for 30 min with a 1000 ms integration time.

Flg22‐induced MITOGEN‐ACTIVATED PROTEIN KINASE (MAPK) activation was assessed (Xu et al., 2018) using leaf disks collected from six plants per CO2 treatment. Leaf disks were maintained in CO2 chambers, treated with 10 μM of flg22 peptide, and sampled between 0 and 250 min. Total protein was extracted and normalized (Wang et al., 2018), and MAPK activation was assessed by immunoblot analysis using primary anti‐Phospho‐p44/42 MAPK antibody (Erk1/I 2; Thr‐202/Tyr‐204) (Cell Signaling, Danvers, MA, USA) and secondary goat anti‐rabbit‐HRP antibody (Cell Signaling).

Bacterial infection assays

Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea (Psg) race 4, PstDC3000, and PstDC3000 hrcC‐ (hrcC‐) were grown at 30°C overnight in Luria Bertani (LB) broth with appropriate antibiotics. The next day, cells were harvested and resuspended in 10 mM MgCl2 at OD600 = 0.2 (c. 1 × 108 colony‐forming units (CFU) ml−1). Immediately before inoculations, 0.04% of Silwet L‐77 (ThermoFisher Scientific) was added to the suspension, and the unifoliate leaves of 14‐d‐old soybeans were spray‐inoculated on adaxial and abaxial surfaces until fully wet. Leaf disks were extracted from 24 plants per treatment, between 1‐ and 7 d post inoculation (dpi). Leaf disks from three plants were pooled per sample and were used to quantify CFU cm−2 (Liu et al., 2015). For phytohormone analyses, eight plants per treatment were sampled at 6‐ and 24 h post inoculation (hpi) and 3′ mRNA sequencing (3′ mRNA‐Seq) analysis was performed using 6 hpi samples. Detailed methods describing extraction and quantification of the phytohormones SA and JA are provided in Methods S1. g sw in response to Psg was measured at 1 hpi using 10 plants per treatment. For 3′ mRNA‐Seq analyses, leaves were collected from eight Psg‐infected and mock‐inoculated plants per CO2 treatment and chamber, yielding three biological replicates per treatment (96 samples, QuantSeq dataset 2). Samples were collected between 09:00 h and 10:00 h for all replicates.

Bacterial growth curves

Liquid PstDC3000 cultures were seeded at a concentration of 1 × 107 CFU ml−1 in 100 ml of LB broth containing appropriate antibiotics. Cultures were grown in 500‐ml Erlenmeyer flasks with gas‐permeable caps to allow free diffusion of CO2 and kept in temperature‐controlled growth chambers maintained at 28°C (no light), c. 20% relative humidity, and either 419 or 550 ppm of CO2. Cultures were shaken at 100 rpm and OD600 was recorded every 4 h over 32 h.

QuantSeq 3′ mRNA‐Seq analyses

Total RNA was extracted from c. 50 mg of soybean leaf tissue using the Direct‐zol RNA Miniprep Plus Kit with DNaseI treatment (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). RNA samples were quantified using a Qubit 4.0 Fluorometer (Invitrogen), and RNA integrity was assessed using the Fragment Analyzer Automated CE System. All RNA samples used for sequencing had an RQN (RNA Quality Number) equal to or > 7. Library preparation was performed using the QuantSeq 3′ mRNA‐Seq Library Prep Kits (Lexogen, Greenland, NH, USA), and samples were sequenced using the Illumina NovaSeq 6000 System (Iowa State University DNA Facility). Details of bioinformatic and statistical analyses of 3′ mRNA‐Seq data to identify differentially expressed genes (DEGs) and subsequent analysis of DEG annotation and identification of overrepresented transcription factors and promoter elements are provided in Methods S1.

Viral infection assays

Lyophilized soybean leaves infected with BPMV or SMV were ground in 10 ml of 50 mM potassium phosphate buffer (pH 7.5) per 1 g of tissue. One unifoliate leaf of 14 dap soybean was dusted with carborundum (Fisher Scientific) and rub‐inoculated with 50 μl of inoculum or buffer (Mock). The second unifoliate leaf was inoculated 2 d later using the same method. Systemic leaves were sampled from six plants per treatment, at 14 and 21 dpi to assess viral titer. Fresh weight, dry weight, and gene expression were measured using 21 dpi plants. Disease severity was evaluated between 0 and 21 dpi using a single‐digit disease rating scale ranging from 0 to 3 (0–no disease, 1–mild, 2–moderate, and 3–severe). Area under disease progress curve (AUDPC) was calculated based on the equation (Simko & Piepho, 2012).

, disease severity on i th date; , i th date; , total number of observations.

Fusarium virguliforme and P. sylvaticum infection assays

Sterilized sorghum (Sorghum bicolor (L.) Moench) seeds were inoculated with F. virguliforme O'Donnell and T. Aoki (isolate LL0036) and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 21 d and dried for 3–4 d. Styrofoam cups (8 oz.) were filled with a mixture of 180 ml of sterile sand soil and 9 ml of F. virguliforme‐infested sorghum. Soybean seeds were placed in the cups and covered with 25 ml of peat mix. At 35 dap, roots and shoots were sampled from six cups of each CO2 treatment to measure fresh weight and dry weight. Disease severity was assessed on leaves on a 0 to 7 rating scale (Roth et al., 2019) (Table S2), and the AUDPC was calculated. For plate growth assays, a starting culture of F. virguliforme was prepared on 1/3 strength potato dextrose agar (PDA) and grown at room temperature for 21 d in the dark. A 7‐mm plug was punched out of the starting culture and placed into the center of a 90‐mm‐diameter Petri dish containing 1/3 strength PDA. Ten plates per CO2 treatment were maintained in the dark under aCO2 or eCO2, and hyphal growth was assessed every other day for 11 d.

Millet was inoculated with a 3‐d‐old culture of P. sylvaticum W. A. Campb. & F. F. Hendrix 1967 and incubated in the dark at room temperature for 7–14 d (Matthiesen et al., 2016). A mixture of 100 ml of sterile sand soil and 5 ml of P. sylvaticum‐infested millet was placed in a 237 ml (8 oz.) polystyrene cup and covered with 25 ml of peat mix. The seed was placed on top of the peat mix and then covered with another 25 ml layer of peat mix. At 14 dap, plants in six cups of each treatment were uprooted, roots were washed, and disease severity was assessed using a 0 to 4 rating scale (Zhang & Yang, 2000) (Table S3). Root and shoot fresh weight and P. sylvaticum copy numbers were determined at 21 dap. For plate growth assays, a starting culture of P. sylvaticum (isolate Gr8) was grown on 1/2 strength PDA at room temperature for 5 d in the dark. A 7‐mm plug was punched and transferred into the edge of a 90‐mm‐diameter Petri dish containing 1/2 strength PDA. Ten plates per treatment were incubated in the dark under aCO2 or eCO2, and growth was measured from the edge of the inoculum plug to the tip of the longest hypha every 24 h for 96 h.

Statistical analysis

Linear mixed‐effects models (LMM) were fit to each response following the experimental design. Taking the bacterial infection experiment measuring CFUs as an example, the whole‐plot factor was CO2 level and the whole‐plot experimental units were growth chambers. Randomized complete block design was implemented at the whole‐plot level, with each block comprising a pair of chambers at aCO2 or eCO2. At the split‐plot level, 24 plants were assigned to each pathogen, with sets of three plants pooled for each CFU measurement, repeated over time. Following this split‐plot design, the fixed effects of the LMM include the main effects and all interaction effects of the factors CO2, bacterial species, and time, and random effects include block, chamber, split‐plot, and sets of plants. Similar to this example, LMMs were fit for other responses following the corresponding experimental designs.

For response variables that exhibited unequal variances on the original scale, LMM analysis was done on power‐ or log‐ transformed data, and the Delta method was used to compute SE for the original scale. For all LMM analysis, model diagnostic checks were done to ensure that model assumptions were appropriate. Parameters of LMM were estimated using lmer() in the lme4 R package. The emmeans() function in the emmeans R package was used to compute the SE. Type III ANOVA tables with F‐tests were conducted by anova() and the lmertest R package.

Results

Elevated CO2 alters soybean physiology and gene expression

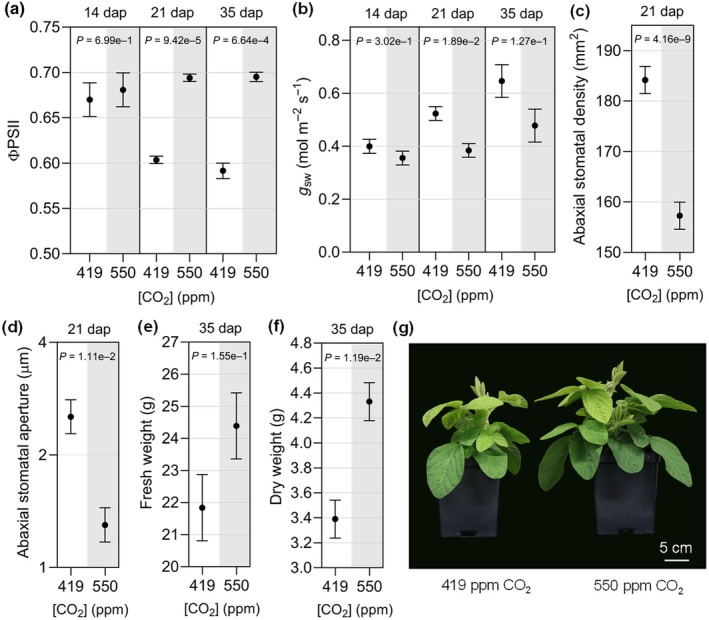

Before studying the effects of eCO2 on soybean defense, we wanted to ensure that our growth conditions caused changes in physiological responses that were previously observed under higher atmospheric CO2 (Ainsworth & Long, 2021; Li et al., 2021). At 14 dap, unifoliate leaves of soybean plants grown in eCO2 displayed no difference in ΦPSII activity compared with plants grown at aCO2 (Fig. 1a). However, at 21 and 35 dap, ΦPSII activity was higher in eCO2 (Fig. 1a), indicating a higher photosynthetic rate in trifoliate leaves. Stomatal conductance to water vapor (g sw) was also affected, with trifoliate leaves of plants grown at eCO2 displaying lower g sw at 21 and 35 dap (Fig. 1b), which was consistent with the lower stomatal density (Fig. 1c) and reduced stomatal aperture (Fig. 1d) on the abaxial leaf surface. In line with the lower stomatal density, a reduction in stomatal index was observed at eCO2, indicating that the decrease in stomatal density was due to reduced stomatal production and not an increase in leaf expansion (Fig. S2). At 35 dap, soybeans grown in eCO2 had greater shoot fresh weight (Fig. 1e) and dry weight (Fig. 1f) and were visibly larger than those grown in aCO2 (Fig. 1g). Together, these experiments demonstrate that a 31% increase in [CO2] induced physiological responses under our conditions that were consistent with prior studies.

Fig. 1.

Effects of elevated CO2 on soybean physiology and growth. (a) Photosystem II (ΦPSII) activity and (b) stomatal conductance (g sw) were measured at the indicated days after planting (dap) using a LI‐600 portable system. (c) Stomatal density and (d) stomatal aperture measured at 21 dap using three randomly selected fields of view per leaf sample using a brightfield microscope. (e) Shoot fresh weight, (f) shoot dry weight, and (g) representative photos of soybean plants at 35 dap. Measurements and samples were taken from the unifoliate leaves at 14 dap or the newest fully expanded trifoliate leaves at 21 and 35 dap of 10 plants at each time point, except ΦPSII and g sw, which were measured in 15 plants per CO2 treatment. The three experimental replicates were conducted simultaneously in independent CO2 controlled chambers using a replicated completely randomized design. Data were graphed as the mean across the three replicates with SE bars. Linear mixed effect model (LMM) analysis was applied to the fourth power of ΦPSII 35 dap and log‐transformed stomatal aperture data due to unequal variance on the original scale. P‐values were computed based on F‐tests for the effect of CO2 at each time point from the LMM analysis. The letter e denotes an exponent to the power of 10 and ppm denotes parts per million.

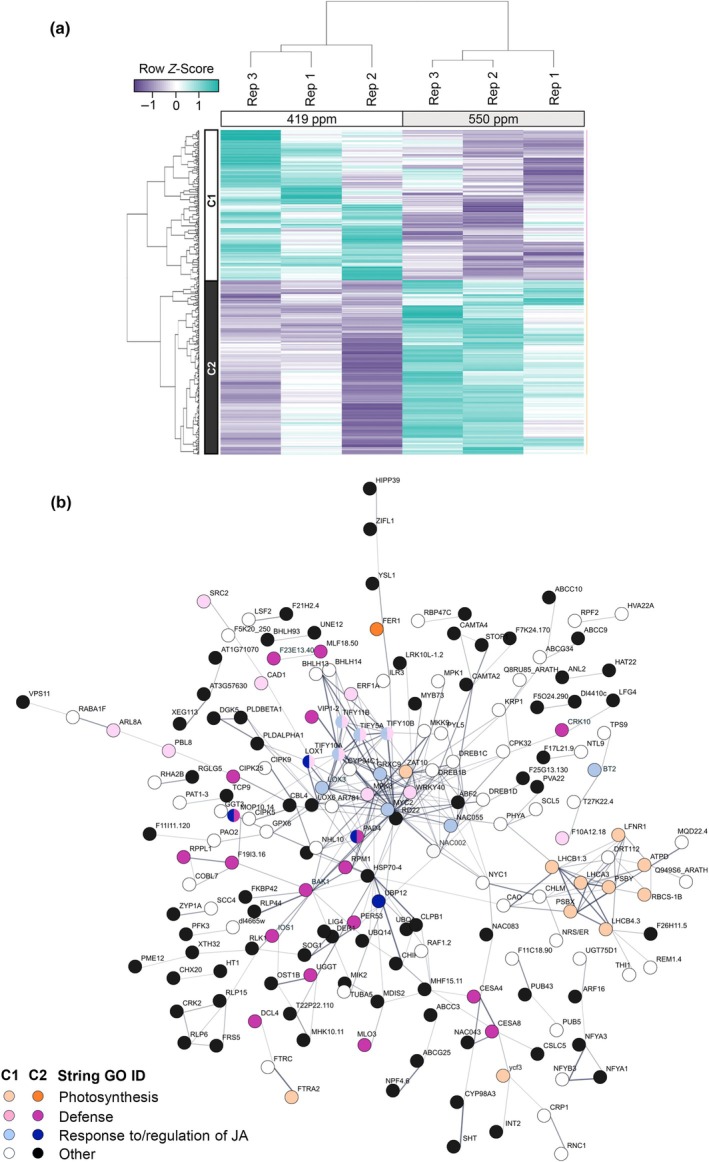

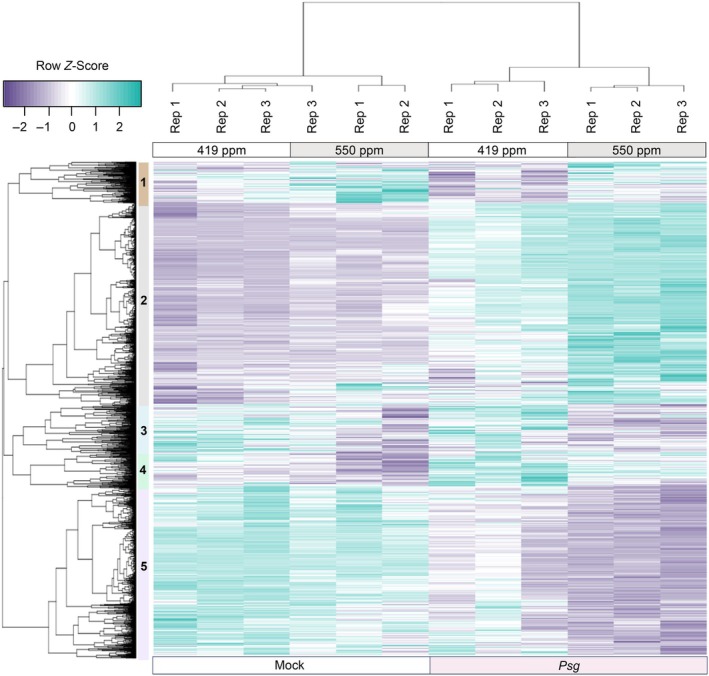

To investigate gene expression changes associated with physiological responses to eCO2, we conducted 3′ mRNA‐Seq analysis using RNA isolated from trifoliate leaves at 21 dap. We identified 388 DEGs (Table S4), which were used to construct a heat map that formed two distinct clusters associated with [CO2] (Fig. 2a). The 180 DEGs in Cluster 1 were repressed in eCO2, while the 208 DEGs in Cluster 2 were induced in eCO2 (Table S4). To identify gene networks responding to [CO2], the 321 best BLASTP Arabidopsis homologs corresponding to our 388 soybean DEGs were were used as input for STRING (Szklarczyk et al., 2023) and Gene Ontology (GO) analyses (Szklarczyk et al., 2023) to identify biological processes (BP) that were overrepresented within each cluster (Table S5). In Cluster 1, two major themes emerge related to: responses to JA signaling (e.g. response to wounding, response to hormone, regulation of defense response, response to lipid, and regulation of JA‐mediated signaling); and photosynthesis (e.g. response to light intensity, response to high light intensity, photosynthesis, and photosynthesis light reaction). The STRING association network produced from the genes in Cluster 1 also highlights the effects on JA signaling with a node of highly connected genes that include MYC2 transcription factor and TIFY (JAZ repressor) genes (Fig. 2b, light blue). A node of highly connected genes in the lower right quadrant includes several genes related to photosynthetic processes, including soybean homologs of AtRbcS1B, AtRAF1, AtLHCB8, AtLHCB1, AtCHLM, and AtPIF1 (Fig. 2b, light orange).

Fig. 2.

Transcriptomic analysis of soybean gene expression in leaves of plants grown under ambient CO2 (aCO2) (419 parts per million (ppm)) or elevated CO2 (eCO2) (550 ppm). (a) Differentially expressed genes (DEG) responding to eCO2 were identified using a false discovery rate < 0.01 (Supporting Information Table S4). Samples for 3′ mRNA‐Seq analysis were taken from the newest fully expanded trifoliate leaves of soybean plants at 21 d after planting (dap). The three experimental replicates (Rep) were conducted simultaneously in independent CO2‐controlled chambers using eight plants per CO2 treatment. Row Z‐scores were used for hierarchical clustering of DEGs, based on expression across samples and replicates. Two expression clusters were identified. DEGs in Cluster 1 (C1) were expressed at higher levels in 419 ppm vs 550 ppm CO2 and DEGs in Cluster 2 (C2) were expressed at higher levels in 550 ppm vs 419 ppm CO2. (b) STRING network for DEGs identified between aCO2 and eCO2 in leaves at 21 dap. The 388 genes identified in soybean correspond to 321 genes in Arabidopsis thaliana that were used to assign functional annotations (String Gene Ontology Identifiers (GO ID)). Lightly shaded or white circles indicate DEGs from C1 and brightly shaded and black circles indicate DEGs from C2.

Major themes emerging from Cluster 2 are BP terms related to: defense (e.g. defense, response to external stimulus, response to biotic stimulus, response to bacterium, and response to other organism); and protein modification (e.g. protein phosphorylation, protein modification process, and phosphorus metabolic process) (Table S5). The STRING association network identifies interconnected genes associated with defense responses (Fig. 2b). These nodes include soybean homologs of AtBAK1, AtPAD4, and AtIOS1 (Table S4), all required for pattern‐triggered immunity (PTI) responses (Yeh et al., 2016; Pruitt et al., 2021), and a number of resistance‐like proteins, including AtRPM1, AtRLP1, and AtRLP44. While not highlighted in the STRING analyses, soybean homologs of genes associated with reduced g sw and stomatal aperture (AtHT1, AtFER, AtZIFL1, AtPLDa1, and AtNRT1:2) were upregulated in eCO2 (Table S4). Together, our gene expression analyses indicate that eCO2 causes changes in the transcriptome of unifoliate soybean leaves, repressing expression of photosynthetic genes, altering JA signaling, priming innate immunity against microbial pathogens, and promoting expression of genes associated with stomatal closure.

Soybean resistance to Pseudomonas spp. is enhanced under eCO2

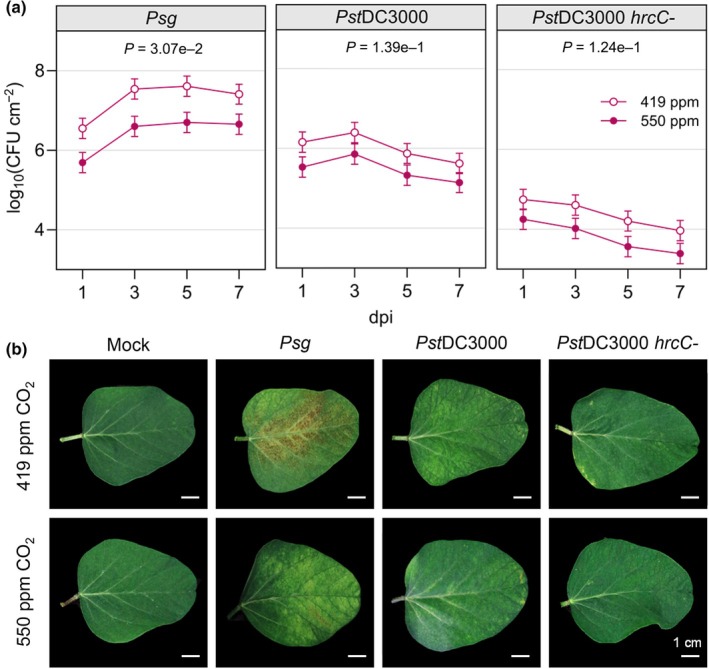

In order to assess the impacts of eCO2 on susceptibility to microbial pathogens, we first used the well‐characterized soybean–P. syringae pathosystem (Lindeberg et al., 2009; Whitham et al., 2016). Basal defense against bacterial pathogens is initiated by cell surface receptors that recognize microbe‐associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), such as the bacterial flagellin peptide flg22 (DeFalco & Zipfel, 2021). Psg, which causes bacterial blight in soybean, was inoculated on the unifoliate leaves of 14‐d‐old plants and chosen to model a compatible interaction where effectors effectively suppress immunity resulting in disease (Prom & Venette, 1997). At 1 dpi, the proliferation of Psg was 1.1‐log10 fold lower in plants grown in eCO2 compared to aCO2 (Fig. 3a), and it remained significantly reduced in eCO2 over the 7‐d time course (Fig. 3a). In compatible interactions, Psg infection causes the development of necrotic spots that become surrounded by yellow halos (Budde & Ullrich, 2000). At 7 dpi, soybeans infected under [aCO2] displayed necrotic lesions across the surface of leaves, consistent with bacterial blight symptoms (Fig. 3b). By contrast and consistent with reduced Psg growth, few disease symptoms were observed on the leaves of plants grown at eCO2 (Fig. 3b).

Fig. 3.

Soybean plants growing in elevated CO2 are less susceptible to Pseudomonas syringae. (a) Colony‐forming units (CFU) of P. syringae pv. glycinea race 4 (Psg), P. syringae pv. tomato (PstDC3000) and PstDC3000 hrcC‐ were quantified in the unifoliate leaves of plants at 1, 3, 5, and 7 d post inoculation (dpi). The unifoliate leaves of 24 plants were sampled for each treatment group, and three independent biological replicates were performed. Data points represent the mean CFU count of the three biological replicates with SE bars. P‐values were computed using t‐tests for the contrast between two CO2 levels of each pathogen averaged over dpi from the linear mixed effect model analysis. (b) Representative images of unifoliate leaves photographed at 7 dpi. Mock plants were treated with 10 mM MgCl2, 0.04% Silwet L‐77 solution with no bacteria. The letter e denotes an exponent to the power of 10.

We also inoculated the unifoliate leaves of 14‐d‐old plants with PstDC3000, as an example of an incompatible interaction causing hypersensitive cell death resulting in disease resistance (Kobayashi et al., 1989), and the PstDC3000 type III secretion mutant, hrcC‐, that cannot secrete bacterial effector proteins and therefore cannot multiply or induce hypersensitive cell death (Brooks et al., 2004). Lower CFUs were consistently observed across the time course in soybean grown at eCO2 when inoculated with either PstDC3000 or hrcC‐, although the P‐values were > 0.05 (Fig. 3a). At 7 dpi, PstDC3000‐infected plants grown at either [CO2] began to show signs of localized chlorosis and cell death while hrcC‐ infection did not result in obvious disease or defense phenotypes, regardless of the [CO2] (Fig. 3b).

To assess whether atmospheric [CO2] independently affects bacterial growth rate, we conducted a growth curve analysis on liquid cultures of PstDC3000 in our controlled environment growth chambers. The growth curves of PstDC3000 cultures were similar between the two CO2 levels (Fig. S3), indicating that reduced growth of P. syringae in soybean is not due to direct effects of eCO2 on bacterial multiplication. Together, these data suggest that eCO2 enhances resistance to P. syringae infection in soybean during compatible interactions and, to a lesser extent, during an incompatible interaction.

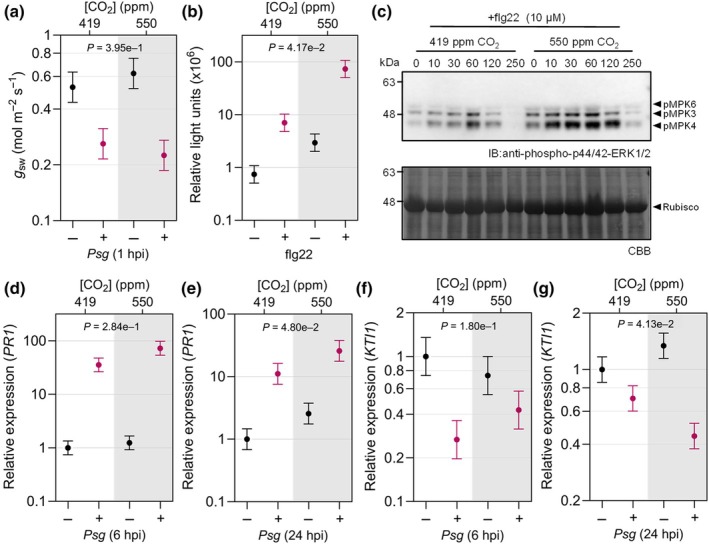

Elevated CO2 alters basal immune responses

To determine whether eCO2 affects immunity to Psg at a molecular level, we assessed multiple hallmarks of plant immune signaling. In response to Psg, the change in stomatal conductance following Psg treatment did not differ between [CO2] (Fig. 4a). However, soybeans grown at eCO2 exhibited greater overall production of reactive oxygen species when considering both mock‐ and flg22‐treated leaf disks (Fig. 4b) as well as higher and more sustained MAPK activation (Fig. 4c). We also observed that a soybean PR1 homolog, an SA‐regulated defense gene, accumulated to higher levels in mock‐ and Psg‐inoculated plants grown in eCO2, particularly in the 24 hpi sample (Fig. 4d,e) and corresponded to a slightly greater SA accumulation in leaves sampled at 6 hpi (Fig. S4a). At 24 hpi, expression of the JA marker gene KTI1 was more downregulated in response to Psg (Fig. 4f,g). However, JA accumulation was not affected by [CO2] in our metabolite analysis (Fig. S4b). Together, these data suggest that bacterially induced immune signaling is more robust in plants grown in eCO2, which correlates with the enhanced resistance to Pseudomonas spp. in these plants.

Fig. 4.

Bacterially induced defense signaling is more strongly upregulated in soybean leaves grown under elevated CO2. (a) Stomatal conductance (g sw) at 1 h post inoculation (hpi) with Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea race 4 (Psg). (b) Reactive oxygen species (ROS) production in response to bacterial flagellin 22 (flg22) peptide was quantified using a chemiluminescence assay. Relative light units were determined using leaf disks from 12 plants per treatment, and (c) flg22‐induced MAPK activation using protein extracted from 12 plants per time point (0 to 250 min after treatment) and visualized by immunoblot analysis. Expression of PR1 (SA marker gene) (d) 6 hpi and (e) 24 hpi and expression of KTI1 (JA marker gene) (f) 6 hpi and (g) 24 hpi with Psg or mock treatment was assessed by reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction. RNA was extracted from six plants per treatment, and expression was measured relative to the Skp1 housekeeping gene. All experiments were conducted using leaves or leaf disks collected from 14‐d‐old plants grown under 419 parts per million (ppm) or 550 ppm CO2. Three independent replicates were conducted for each experiment. Data points represent average values across the three experimental replicates with SE bars. P‐values for ROS production and PR1 expression were computed using F‐tests for the main effect of CO2, and g sw and KTI1 expression using the interaction effect between CO2 and Psg, from the linear mixed effect model analysis based on log‐transformed data. The letter e denotes an exponent to the power of 10.

eCO2 alters the soybean transcriptome in response to Psg

To gain further insight into the effects of eCO2 on molecular responses to Psg treatment, we conducted 3′ mRNA‐Seq analysis on the unifoliate leaves at 6 hpi with buffer alone (mock) or with Psg. We identified DEGs in mock‐ vs Psg‐treated plants grown at each of the two [CO2]: 18054 DEGs were identified in plants grown in aCO2 and 19 443 DEGs were identified for plants grown in eCO2. We produced a combined list of all unique DEGs for a total of 21 822 Psg‐responsive DEGs, which was used to generate a heat map that formed four distinct clusters (Fig. S5; Table S6). Cluster 1 (1661 DEGs) had mixed expression in response to Psg treatment and no significantly (corrected P < 0.05) overrepresented GO terms (Table S7). Cluster 2 (9822 DEGs) was induced by Psg treatment and had 81 significant GO terms associated with stress (response to cadmium ion, heat, hypoxia, oxidative stress, salt, and UV‐B), defense (response to chitin, defense response to bacterium, fungus, and virus, cell death, regulation of SA biosynthesis, response to SA, hypersensitive response, and systemic acquired resistance), and ER stress (protein folding, response to unfolded protein, and response to ER stress). Clusters 3 (6718 DEGs) and 4 (3621 DEGs) were repressed by Psg treatment. While Cluster 3 had 50 significant GO terms associated with photosynthesis, response to light, and circadian rhythm, Cluster 4 had two significant GO terms: response to starvation and oxidation–reduction process. Among DEGs repressed by Psg treatment in aCO2 and eCO2 conditions, 61.6% had greater negative fold‐changes in eCO2 (7419/12 053 DEGs). Similarly, for DEGs induced by Psg in aCO2 and eCO2 conditions, 60.1% had greater positive fold‐changes in soybeans grown in eCO2 (5671/9357 DEGs).

To further understand how responses to Psg differ with changes in atmospheric [CO2], we identified 622 and 1919 DEGs associated with eCO2 vs aCO2 in mock‐ or Psg‐inoculated plants, respectively (Table S8). Using a union of these two lists, we generated a heatmap of the 2419 DEGs, which formed five distinct clusters (Fig. 5). To assign potential function to each of the clusters, we used the Arabidopsis best blastp homologs corresponding to all DEGs within a cluster as input into STRING (Szklarczyk et al., 2023) and performed GO BP enrichment for each cluster (Table S9). Cluster 1, which tended to be induced by eCO2 in mock and Psg samples, was associated with 40 GO terms related to stress (response to chemical, stress, and abiotic stimulus) and defense (regulation of JA signaling, response to JA, response to bacterium, and defense response). DEGs in Cluster 2 were induced by Psg with greater induction observed in eCO2 and corresponded to 139 significant GO terms related to stress and defense responses. DEGs in Cluster 3 were repressed by eCO2 and corresponded to 37 significant GO terms, many associated with stress and regulation (regulation of transcription, circadian rhythm, primary metabolism, development, and photoperiodism). DEGs in Cluster 4 were induced by Psg with greater induction observed in aCO2 and corresponded with 83 significant GO terms associated with stress, signaling, development, and defense. DEGs in Cluster 5 were repressed by Psg, with greater repression at eCO2. The 37 GO terms in Cluster 5 were largely associated with photosynthesis and response to light.

Fig. 5.

Identification of soybean differentially expressed genes (DEGs) responding to elevated CO2 (eCO2) (419 parts per million (ppm) vs 550 ppm) in either mock or Pseudomonas syringae pv. gylcinea (Psg)‐infected samples at 6 h post inoculation (hpi). Samples for 3′ mRNA‐Seq analysis were taken from the unifoliate leaves of 14‐d‐old plants at 6 hpi with mock treatment or Psg. The three independent biological replicates (Rep) were conducted using eight plants per CO2 treatment. Using a false discovery rate < 0.01, we identified 2419 differentially expressed genes (DEG) responding to eCO2 in Psg and/or mock‐treated samples. Row Z‐scores were used for hierarchical clustering of DEGs, based on expression across samples and replicates. Purple indicates expression values below the row mean for a given DEG and sample and teal indicates expression values above the row mean for a given DEG and sample. Rep indicates the independent biological replicate. The five major expression clusters of DEGs are indicated as 1 to 5, with Clusters 2 and 5 containing the most genes. Cluster 2 contains 986 genes that are primarily upregulated at 6 hpi with Psg but these genes are upregulated more in eCO2. Cluster 5 contains 828 genes that are downregulated at 6 hpi with Psg, but these genes are more downregulated in eCO2.

Across all 2419 DEGs, 74.8 and 83.2% of DEGs responding to eCO2 in Psg or mock were also significantly differentially expressed in response to Psg at aCO2 and eCO2, respectively. This confirms that eCO2 impacts the expression of genes involved in pathogen defense responses. This is most obvious in Clusters 2 (986 DEGs) and 5 (828 DEGs), where 71.1 and 94.3% of DEGs are also significantly differentially expressed in response to Psg at aCO2 and 82.3 and 99.5% of DEGs are also significantly Psg‐responsive in eCO2. In summary, the 3′ mRNA‐Seq analyses indicate that eCO2 does not cause a reprogramming of responses to Psg, but rather it enhances the up‐ or downregulation of many genes associated with defense and stress responses and photosynthetic processes.

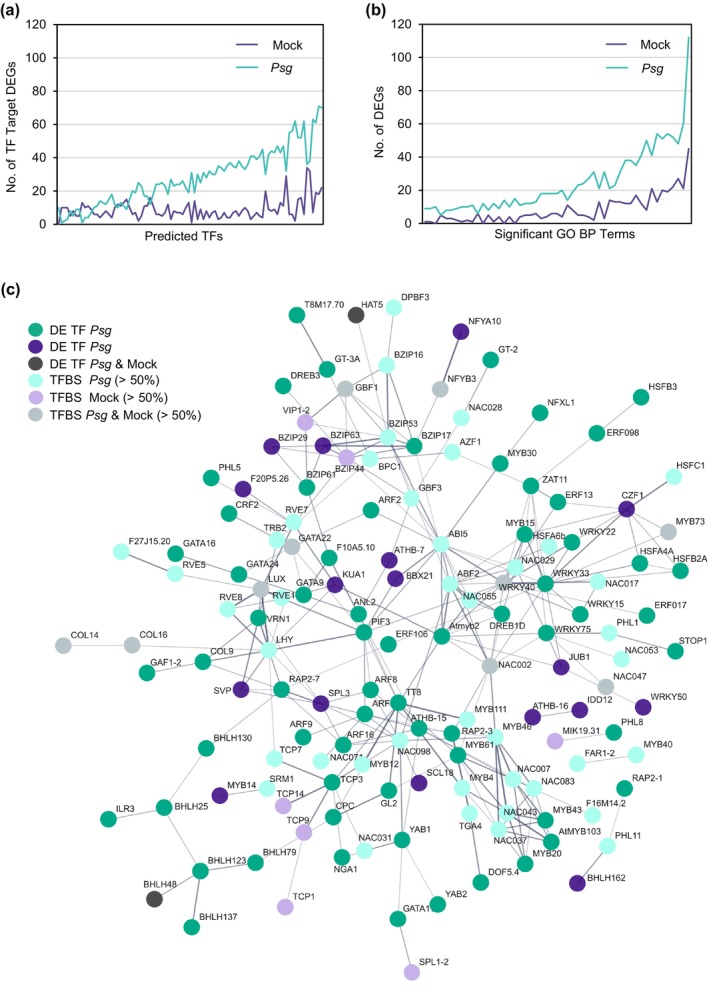

Identification of regulatory elements controlling response to eCO2

We next sought to identify the transcription factors (TFs) that were differentially expressed in the 2419 DEGs responding to eCO2 in Fig. 5. Across all five clusters, we identified 144 TFs representing 31 transcription factor families. Clusters 1–5 contained 7, 43, 27, 19, and 48 unique TFs, respectively (Table S10). Given that many of the GO term descriptions significantly overrepresented in Clusters 1 through 5 included the words ‘response to’ or ‘regulation of’, we were interested in predicting upstream TFs that could also be important in eCO2 responses. Using the DEG list for each cluster as input into PlantRegMap (Tian et al., 2020), we identified 1, 44, 18, 13, and 16 significantly overrepresented TF binding sites (TFBS) for Clusters 1–5, respectively (Table S11). Interestingly, some predicted TFBS were significant in multiple clusters. In addition, five predicted TFBS were also among our DEGs of interest. We identified the DEG targets corresponding to each overrepresented TFBS (Table S12). In order to assign a possible function to a TF with an overrepresented TFBS, we used the SoyBase GO Term Enrichment Tool (https://www.soybase.org/goslimgraphic_v2/dashboard.php) to identify significantly overrepresented GO terms (corrected P < 0.05) associated with the corresponding target DEGs (Table S13). Of the 92 significant TFBS predicted, 48 had significantly overrepresented GO terms. Identified GO terms were associated with stress (response to heat, H2O2, redox state, phosphate starvation, and light), regulation (cell aging, circadian rhythm, growth rate, proton transport, and transcription), photosynthesis (light reaction, electron transport, and plastid organization), and defense (fatty acid elongation, biosynthesis of anthocyanins, carotenoids, and flavonoids, and negative regulation of defense response to bacterium). Sorting the data in Table S13 revealed multiple TFs were regulating DEGs corresponding to the same GO term. For example, we identified nine significant TFBS associated with photosynthetic electron transport in photosystem I.

Given these results, we wanted to examine the TF/TFBS data relative to our DEGs from mock and Psg‐infected tissues. We plotted the number of target DEGs corresponding to each predicted TFBS (Fig. 6a). For almost every predicted TFBS, there were more targets among DEGs from Psg‐infected tissues than mock‐inoculated tissues, suggesting Psg infection resulted in a more robust response to eCO2. To confirm this pattern was not due to errors in predicting TFBS, we also plotted the number of DEGs associated with significantly overrepresented GO terms (Fig. 6b; Tables S8, S9). For almost every significant GO term, there were more GO terms associated with Psg‐infected tissues than mock‐inoculated tissues. To better visualize the interaction between TF and TFBS, we used the best Arabidopsis homolog of each TF and TFBS as input into STRING (Szklarczyk et al., 2023). In Fig. 6c, TF and TFBS associated with Psg‐infected tissues are colored shades of teal, while TF and TFBS associated with mock‐inoculated tissues are colored shades of purple. As in 6a and 6b, the TF and TFBS from Psg‐infected tissues are far more robust, confirming Psg infection enhances responses to eCO2.

Fig. 6.

Significantly differentially expressed transcription factors (TF) and overrepresented TF binding sites (TFBS) are more robust in Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea (Psg)‐infected tissues responding to elevated CO2 (eCO2) than mock‐inoculated tissues. PlantRegMap/PlantTFDB v.5.0 (Tian et al., 2020) was used to identify significantly differentially expressed TFs and significantly overrepresented TFBS among the differentially expressed gene (DEG) clusters identified in Fig. 5 (Supporting Information Tables S9–S11). (a) Significant TFBS vs predicted number of DEG targets. Overrepresented TFBS and DEG targets are plotted for every cluster (cluster information not shown); therefore, if a TFBS was significant in multiple clusters, it was plotted multiple times but with different DEG targets. (b) Significantly overrepresented Gene Ontology (GO) terms (minimum of 10 DEGs per GO term) vs DEG number (Table S5). In both panels, DEG in teal were significant in Psg samples and/or DEG in purple were significant in mock‐treated samples. (c) Best Arabidopsis homologs of TFs and TFBS were input into STRING (Szklarczyk et al., 2023). TFs differentially expressed in response to eCO2 in Psg‐treated samples, mock‐treated samples or both are colored dark teal, dark purple or gray, respectively. TFBS are colored based on the origin of the target DEG.

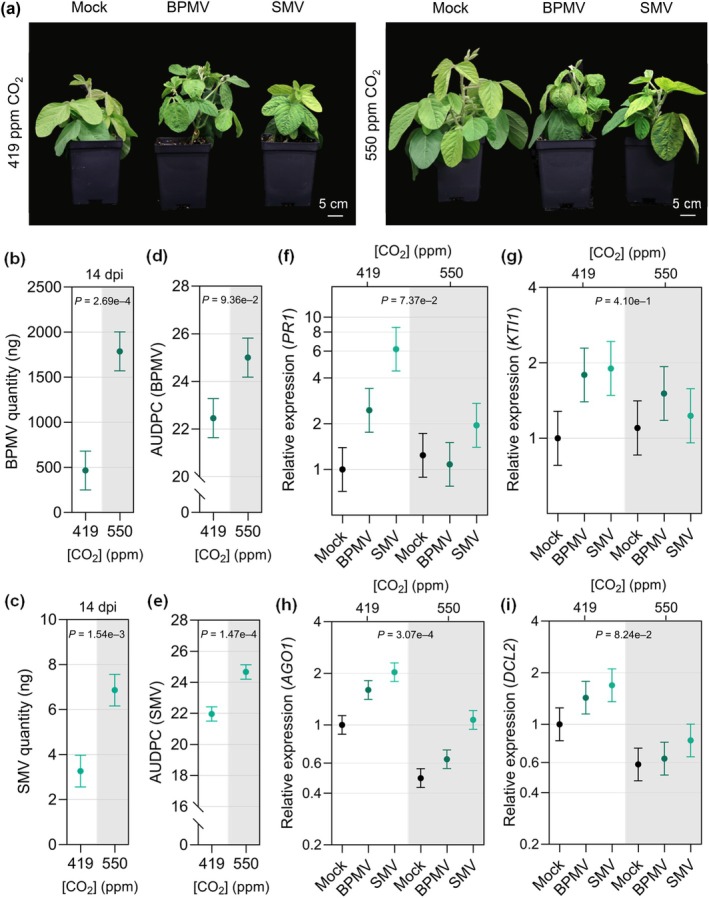

eCO2 suppresses viral immunity

To determine whether eCO2 affects virus susceptibility in soybean, we inoculated the unifoliate leaves of 14‐d‐old plants with two virus species, BPMV, a Comovirus in the family Secoviridae (Sanfaçon et al., 2009), and SMV, a Potyvirus in the family Potyviridae (Hajimorad et al., 2018). BPMV and SMV caused a greater reduction in soybean growth and shoot dry weight when compared to the mock plants in eCO2 than in aCO2 (Figs 7a, S6). Accumulation of BPMV and SMV was higher in the newest fully expanded trifoliate leaves of infected plants grown at eCO2 compared to those grown at aCO2 at 14 dpi (Fig. 7b,c) and to a lesser extent at 21 dpi (Fig. S7). Accordingly, the AUDPC was greater for BPMV‐ and SMV‐infected plants grown at eCO2 (Fig. 7d,e). We used reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction to assay expression of soybean homologs of four genes associated with defense responses to viruses: PR1, KTI1, AGO1, and DCL2. We found that the overall mean expression of the SA marker gene, PR1, was lower at eCO2 when considering both mock‐ and virus‐infected plants (Fig. 7f). In addition, expression of PR1 was induced in both BPMV‐ and SMV‐infected plants relative to mock‐inoculation under aCO2. However, PR1 expression in the virus‐infected plants was similar to the mock‐inoculated plants in eCO2. The expression of KTI1 was similar under the two CO2 levels (Fig. 7g), and its induction in virus‐infected vs mock plants was not significantly different between aCO2 and eCO2, suggesting that JA‐mediated defenses against viruses were not affected. We also observed that AGO1 and DCL2 accumulated to lower levels in plants grown at eCO2 (Fig. 7h,i), suggesting that RNA silencing‐based defenses could potentially be compromised (Leonetti et al., 2021; Akbar et al., 2022). These data suggest that the increased susceptibility of soybean to BPMV and SMV under eCO2 may be partially mediated by suppression of SA‐related signaling and RNA‐silencing mechanisms.

Fig. 7.

Young soybean plants growing in elevated CO2 (eCO2) are more susceptible to bean pod mottle virus (BPMV) and soybean mosaic virus (SMV). (a) Representative photos of soybean growth in response to eCO2 during infection with BPMV or SMV compared with mock‐treated control plants. Plants were photographed at 21 d post‐inoculation (dpi). (b) BPMV and (c) SMV quantity at 14 dpi was assessed by reverse transcriptase‐quantitative polymerase chain reaction using Skp1 as a housekeeping gene. Disease progression of (d) BPMV and (e) SMV calculated as the area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC) over a 35‐d time course. Expression of (f) PR1 (SA marker gene) (g) KTI1 (JA marker gene), and RNA‐silencing‐related genes (h) AGO1 and (i) DCL2 in response to BPMV, SMV, or mock treatment was assessed by reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis relative to the expression of Skp1. The newest fully expanded leaves of eight plants were sampled at the indicated time point for each treatment. The three experimental replicates were conducted simultaneously in independent CO2 controlled chambers using a replicated complete randomized design. Data were graphed as the mean across the three replicates with SE bars. P‐values were computed using F‐tests for the main effect of CO2 from the linear mixed effect model (LMM) analysis on the log‐transformed relative gene expression data. The following P‐values were associated with the log‐transformed relative PR1 expression of virus‐infected plants compared to mock‐treated plants at ambient CO2 condition: p(BPMVPR1,419) = 0.1282, p(SMVPR1,419) = 0.0178 and at eCO2 condition: p(BPMVPR1,550) = 0.7779, p(SMVPR1,550) = 0.3882. All was calculated based on t‐tests for the contrasts between each pathogen and mock at the corresponding CO2 conditions from the LMM analysis. The following P‐values were computed using t‐tests from the LMM analysis for the interaction effect between CO2 condition and pathogen treatment (virus or mock) on log‐transformed KTI1 gene expression: p(BPMVKTI1) = 0.6156 and p(SMVKTI1) = 0.3444. The letter e denotes an exponent to the power of 10.

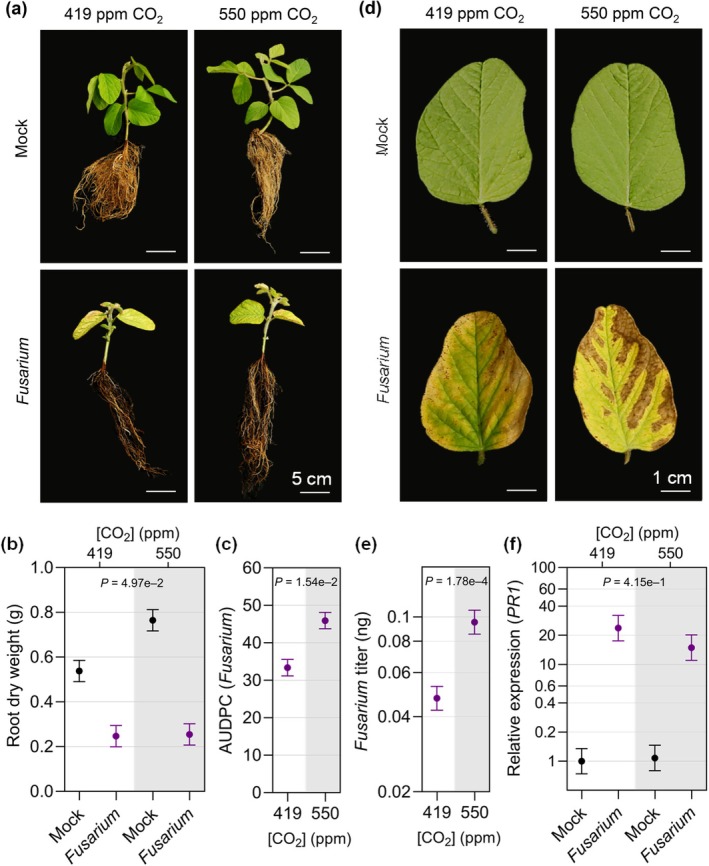

Susceptibility to soil‐borne filamentous pathogens is altered under elevated CO2

To determine whether eCO2 also impacts susceptibility to soil‐borne pathogens, we inoculated soybean with F. virguliforme, a hemibiotrophic fungus causing SDS (O'Donnell et al., 2010), or P. sylvaticum, a necrotrophic oomycete causing seed decay and seedling root rot (Rojas et al., 2017). In mock‐inoculated plants, root dry weight was increased in eCO2 relative to aCO2 (P = 0.0098), which is consistent with the increased shoot dry weight and overall CO2 fertilization effect in soybean (Fig. 1). Root and shoot dry weight were decreased to a greater extent in F. virguliforme‐infected plants grown in eCO2 compared with plants grown under aCO2 at 35 dap (Figs 8a,b, S8). Correspondingly, progression of the foliar symptoms of SDS was greater (Fig. 8c) and more severe symptoms developed on the leaves under eCO2 (Fig. 8d). Consistent with the increased disease symptoms, F. virguliforme was more abundant in the tap roots of plants grown in eCO2 at 35 dap (Fig. 8e). To investigate whether expression of SA‐ or JA‐related defense genes was affected in eCO2, accumulation of PR1 and KTI1 mRNA transcripts, respectively, was quantified in soybean roots using reverse transcription quantitative polymerase chain reaction. Expression of neither gene was convincingly altered in response to F. virguliforme infection in eCO2 relative to plants grown under aCO2 (Figs 8f, S9). To investigate whether F. virguliforme growth is affected by [CO2], we measured the diameter of F. virguliforme colonies as they grew on plates for 11 d in aCO2 or eCO2. Fungal growth was similar at the two CO2 levels (Fig. S10), indicating that the greater fungal accumulation in roots and SDS progression observed in soybeans at eCO2 is not caused by increased pathogen replication rate. Together, our data suggest that eCO2 increases susceptibility to F. virguliforme, although the underlying molecular mechanisms mediating this altered interaction are unclear.

Fig. 8.

Young soybean plants growing in elevated CO2 (eCO2) develop more sudden death syndrome (SDS) symptoms and are more susceptible to Fusarium virguliforme. (a) Representative photos of soybean plants at 35 d after planting (dap) that were mock‐treated or germinated in soil infested with F. virguliforme (Fusarium) and (b) associated root dry weight. (c) SDS disease progression, assessed as area under the disease progress curve (AUDPC), and (d) close‐up photographs of SDS disease symptoms on unifoliate leaves at 35 dap. (e) F. virguliforme titer was assessed by quantitative polymerase chain reaction and (f) expression of PR1 (SA marker gene) in soybean roots at 35 dap was assessed by reverse transcriptase‐quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis relative to the Skp1 housekeeping gene. The three experimental replicates were conducted simultaneously in independent CO2 controlled chambers using a replicated complete randomized design. Data were graphed as the mean across the three replicates with SE bars. P‐values were computed using F‐tests for the main effect of CO2 on AUDPC and log‐transformed titers, and interaction effect between CO2 and Fusarium treatment on root dry weight and log‐transformed PR1 gene expression from the linear mixed effect model analysis. The letter e denotes an exponent to the power of 10.

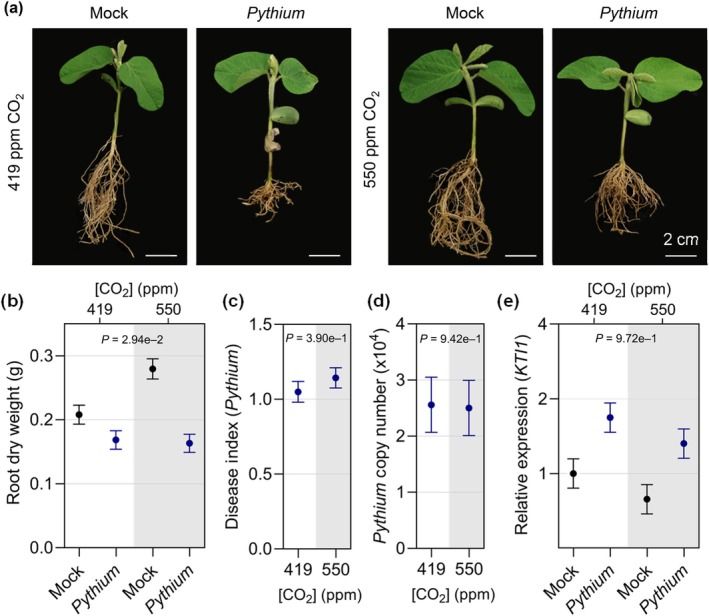

Pythium sylvaticum caused noticeable root rot under both CO2 concentrations (Fig. 9a). Although mock‐inoculated plants exhibited an increase in root dry weight at eCO2 (P‐value = 0.0092), the root and shoot dry weights of P. sylvaticum‐infected plants were more dramatically decreased compared with the mock treatment under eCO2 relative to aCO2 (Figs 9b, S11). Hyphal growth assays indicated that P. sylvaticum grew more quickly in eCO2 than in aCO2 (Fig. S12). However, disease index ratings were similar between infected plants grown under both [CO2] (Fig. 9c), which was consistent with the similar P. sylvaticum titers observed in roots at 14 dap (Fig. 9d). Additionally, no difference was observed in KTI1 expression (Fig. 9e), and while the P‐value for PR1 expression was below 0.05, we do not consider it to be significant because of the similar levels of expression in Pythium‐infected tissue (Fig. S13) at 14 dap between the two [CO2]. Together, our results suggest that eCO2 could have a minor effect on in vitro growth of P. sylvaticum; however, we could not demonstrate that this led to the pathogen being more aggressive in the roots. It is also interesting that while susceptibility to P. sylvaticum appears to be unchanged, there is a greater loss in root and shoot biomass in plants grown in eCO2.

Fig. 9.

Effects of elevated CO2 (eCO2) on Pythium sylvaticum infection in soybean. (a) Representative photos of soybean plants at 21 d after planting (dap) that were mock‐treated or germinated in soil infested with P. sylvaticum (Pythium) and (b) associated root dry weight. (c) P. sylvaticum disease index measured at 14 dap and (d) P. sylvaticum copy number in roots determined by quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis at 14 dap. (e) KTI1 (JA marker gene) expression in response to mock treatment or P. sylvaticum infection assessed by reverse transcriptase‐quantitative polymerase chain reaction analysis. Gene expression was assessed relative to the Skp1 housekeeping gene. The three experimental replicates were conducted simultaneously in independent CO2‐controlled chambers using a replicated complete randomized design. Data were graphed as the mean across the three replicates with SE bars. P‐values were computed using F‐tests for the main effect of CO2 on area under disease progress curve and Pythium copy number, and interaction effect between CO2 and Pythium treatment on root dry weight and log‐transformed KTI1 expression from the linear mixed effect model analysis. The letter e denotes an exponent to the power of 10.

Discussion

Given the central role of CO2 in plant biology and its increasing abundance in the atmosphere, there are many effects on plant physiology that can potentially impact interactions with pathogenic microbes (Bazinet et al., 2022). While some themes are beginning to emerge, it remains challenging to predict the response of a given plant to a given pathogen under eCO2. Here, we selected a diverse panel of phytopathogens to assess whether and how soybean–microbe interactions are impacted by eCO2. Our results demonstrate that CO2 levels expected by mid‐century (Jaggard et al., 2010) have significant impacts on soybean immunity that varied across the different pathogen types.

Extensive research from SoyFACE experiments has demonstrated that under favorable environmental conditions, eCO2 (550 ppm CO2) has the potential to benefit soybean growth and yield (Long et al., 2006; Ainsworth & Long, 2021). In line with field results, we observed that leaf photosynthetic rate and plant biomass increased, whereas stomatal conductance, density, and aperture decreased (Fig. 1). Interestingly, we found that expression of some photosynthesis‐related genes, such as Rubisco small subunit 1B (RbcS1B), decreased under eCO2, which seems contradictory to the enhanced photosynthesis. However, others have shown that mRNA expression of RbcS and other photosynthesis‐related genes can be downregulated as nonstructural sugars accumulate and plants begin to acclimate to eCO2 (Cheng et al., 1998; Thompson et al., 2017). The combined results indicated that the soybean plants were performing as expected in eCO2 under our growth conditions.

The impacts of eCO2 on disease are limited to one study that investigated the incidence and severity of three naturally occurring diseases over 3 years in SoyFACE (Eastburn et al., 2010). eCO2 did not affect SDS incidence or severity, but the severity of brown spot disease (Septoria glycines) increased, while the severity of downy mildew (Peronospora manshurica) decreased. The results from this study are consistent with the idea that diseases caused by necrotrophic pathogens may be typically enhanced under eCO2, whereas diseases caused by biotrophic and hemibiotrophic pathogens may be suppressed in C3 plants (Bazinet et al., 2022). Our goal was to extend these findings under controlled environmental conditions to determine how eCO2 differentially affects responses to distinct types of pathogens and to establish a foundation to understand the complex and dynamic signaling events that influence soybean–pathogen interactions in response to eCO2.

The effects of [CO2] on bacterial infection have not been investigated previously in soybean; however, several independent studies have indicated that for the hemibiotrophic pathogen PstDC3000, eCO2 enhances resistance in tomato (Li et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2021) and mostly increases susceptibility in Arabidopsis (Zhou et al., 2017, 2019). Arabidopsis does not become more susceptible to all pathogens, as it is more resistant to infection with the necrotrophic pathogen B. cinerea at eCO2 (Zhou et al., 2019). In our work, we observed enhanced resistance in compatible interactions between Psg and soybean under eCO2, and to a lesser extent, during incompatible interactions with PstDC3000 and PstDC3000 hrcC‐ (Fig. 3a). Taken together, it is evident that bacterial immunity is altered under eCO2 in C3 plants in a pathosystem‐specific manner.

Phytohormones and stomatal immunity play pivotal roles in altering defense responses to bacteria under eCO2 in Arabidopsis and tomato. For example, in tomato, enhanced resistance to PstDC3000 was associated with eCO2‐induced stomatal closure (Li et al., 2015) and higher SA biosynthesis (Li et al., 2015; Zhang et al., 2015). In Arabidopsis, increased susceptibility to PstDC3000 was associated with reduced abscisic acid (ABA) levels, causing changes in stomatal dynamics favoring bacterial infection (Zhou et al., 2017), and shifts in SA/JA antagonism toward JA‐mediated immunity against necrotrophic pathogens (Zhou et al., 2019). In response to Psg infection, we observed a 1.7‐fold increase in SA accumulation and no notable change in JA levels (Fig. S4). However, this slight increase in SA seems unlikely to provide the level of resistance against Psg observed under eCO2 based on previous work showing that free SA was increased by seven‐ to tenfold in soybean plants exhibiting SA‐dependent, constitutive defense responses (Liu et al., 2011). We hypothesize that enhanced bacterial resistance is likely conferred by a combination of physiological, metabolic, and molecular responses that together limit bacterial infection under eCO2. Indeed, we observed an upregulation of MAMP‐triggered immune responses in soybeans at eCO2 including flg22‐induced oxidative species production (Fig. 4b) and MAPK activation (Fig. 4c). We additionally observed reduced stomatal density (Fig. 1c) and a constitutive decrease in stomatal aperture (Fig. 1d), which is likely to limit the entry of bacterial species.

Our transcriptomic analysis also indicates that eCO2 has direct impacts on soybean defense. eCO2 caused an overrepresentation of DEGs associated with defense responses (Fig. 2; Table S5), even in the absence of pathogen challenge. Most notable was altered expression of genes associated with JA signaling and response to JA, including decreased expression of Jasmonate Zim Domain (JAZ)‐encoding genes, which repress jasmonate signaling, and MYC2 orthologs, known as the master regulators of jasmonate signaling (Johnson et al., 2023). Although we did not observe higher JA levels under eCO2 in our metabolite analysis (Fig. S4), downregulation of these genes suggests that JA‐mediated responses may be altered in soybean plants growing in eCO2. This finding is consistent with prior work demonstrating that various insects prefer to feed on and cause more damage to plants grown in eCO2 (DeLucia et al., 2008; Johnson et al., 2020), which has been attributed at least in part to compromised JA‐mediated defenses (Zavala et al., 2008).

While we focused on JA in our studies, we are aware that ethylene often works cooperatively with JA in plant defense, and there is also evidence that ethylene biosynthesis and response may be affected in soybean in eCO2. Casteel et al. (2008) found that mRNA transcripts for a gene encoding 1‐aminocyclopropane 1‐carboxylate (ACC) synthase were downregulated in eCO2 in SoyFACE before and after beetle damage. However, neither ethylene biosynthesis nor response were enriched GO terms in our experiments. In soybean, there are at least 21 genes annotated as ACC synthase and 16 annotated as ACC oxidase, which catalyze the final steps in ethylene biosynthesis (Arraes et al., 2015), but none were differentially expressed in the newest fully expanded trifoliate leaves at 21 dap (Table S4). However, many of these genes were differentially expressed in the unifoliate leaves following Psg inoculation in both CO2 treatments (Table S6), and of these, there were no ACC synthase genes that were differentially expressed when comparing response to Psg in eCO2 vs aCO2 (Table S8). There were six ACC oxidase genes differentially regulated in response to Psg in eCO2 vs aCO2 (Table S8), and five of these have higher expression in eCO2. These observations suggest that ethylene biosynthesis and response were not downregulated in our experiments and warrant further investigations into the roles of ethylene in soybean–pathogen interactions in future climate scenarios.

We also found no evidence for constitutive upregulation of SA‐mediated defenses under eCO2. However, some genes that positively regulate basal defense responses were upregulated, suggesting that some immune responses might be primed in soybean under these conditions. The effects of eCO2 on DEGs were even more pronounced following Psg infection (Fig. 5; Table S8). Similar DEGs were identified at aCO2 and eCO2 in response to Psg infection; however, the amplitude of these responses were significantly more up‐ or downregulated, depending on the gene, in response to eCO2 (Table S8). This is in line with the higher Psg‐ and flg22‐elicited defense gene expression and basal defense responses under eCO2.

The effects of eCO2 on virus susceptibility have been studied in various other C3 plants, most of which have reported increased resistance to viral pathogens associated with a constitutive overproduction of SA (Fu et al., 2010; Trębicki et al., 2016) or upregulation of RNA silencing genes that are critical for viral defense (Guo et al., 2020). As discussed previously, we did not observe a constitutive stimulation of SA levels or SA‐based defenses in our experimental system, and interestingly, we found that expression of two genes potentially involved in antiviral RNA silencing were decreased (Fig. 7h,i). In line with our molecular analyses, soybean plants were more susceptible to BPMV and SMV in eCO2. Increased susceptibility could be partially explained by reduced induction of SA‐based defenses, as indicated by reduced PR1 gene expression in virus‐treated plants in eCO2 (Fig. 7f). It is also possible that changes in RNA‐silencing components are responsible for increased susceptibility, as we observed a reduction in both AGO1 (Fig. 7h) and DCL2 (Fig. 7i) expression in virus‐infected soybean at eCO2. An interesting avenue to pursue in the future would be to test whether there is a link between the apparent downregulation of SA‐mediated defenses and antiviral RNA silencing.

Many viruses, including BPMV and SMV, are transmitted by an insect vector in nature. Importantly, many of the studies indicating that plants are less susceptible to viruses under eCO2 have used aphids as a vector for viral delivery. Thus, we do not know whether the presence of bean leaf beetle (BPMV) or aphid (SMV) may influence the outcome of the interaction. Furthermore, other factors may be influenced by eCO2 in ways that could affect dissemination of the viruses. For example, the larger canopy size associated with increased photosynthetic rates in soybean are expected to cause a higher dispersion rate, increasing disease incidence, and severity in the field (Amari et al., 2021). It will be interesting to study the tri‐trophic interactions in the future from mechanistic and epidemiological perspectives, and perhaps including other climate change‐associated gasses such as ozone, which retards SMV infection in soybean (Bilgin et al., 2008).

eCO2 has been shown to have various effects on diseases caused by fungi and oomycetes (filamentous pathogens). While various studies have investigated the effect of eCO2 on filamentous pathogens (Smith & Luna, 2023), relatively few have examined soil‐borne pathogens. Elevated CO2 (800 ppm) had no effect on infections caused by Rhizoctonia solani or F. oxysporum in Arabidopsis plants (Zhou et al., 2019). Tomato plants grown in 700 ppm CO2 were more tolerant to root rot caused by Phytophthora infestans (Jwa & Walling, 2001). Growth of P. infestans was not directly affected by [CO2] and the increased resistance of tomato plants could not be associated with changes in expression of marker genes associated with SA‐, ABA‐, or JA‐based defenses. In FACE experiments involving natural infections, eCO2 led to higher incidence of sheath blight (Rhizoctonia solani) on rice (Kobayashi et al., 2006), but SDS (F. virguliforme) in soybean was not affected (Eastburn et al., 2010). Interestingly, the increased incidence of rice sheath blight was only observed in plots that also received input of high nitrogen fertilizer.

Our data indicate that soybean plants are more susceptible to F. virguliforme under eCO2 but had no notable change in P. sylvaticum infection. Surprisingly, we observed a greater loss in root and shoot dry weight in response to P. sylvaticum even though visual disease scores were similar, and similar quantities of P. sylvaticum DNA were observed in the roots of plants grown at eCO2 and aCO2. These observations suggest that the CO2 fertilization effect was lost due to P. sylvaticum infection. We only observed a modest reduction in PR1 expression following F. virguliforme treatment under eCO2, and there was no change in expression of the KTI1 JA marker gene. These gene expression results are similar to what has previously been observed in tomato with increased susceptibility showing no correlation with concomitant changes in expression of defense pathway marker genes (Jwa & Walling, 2001). Various other factors have been linked to F. virguliforme resistance, which we did not assess in this study, including the production of phytoalexins and changes in root exudates, both of which can be affected by eCO2 (Vaughan et al., 2014; Usyskin‐Tonne et al., 2020). Experiments at FACE facilities have demonstrated dramatic changes in the soil microbial rhizosphere and endosphere (Gao et al., 2022; Rosado‐Porto et al., 2022), which could also impact the composition of phytopathogenic fungi in the surrounding soil and cause changes in soybean–pathogen interactions. One could also expect that changes in root architecture and growth could benefit or curtail infection by soil pathogens. Our data indicate that disease losses due to soil‐borne filamentous pathogens can be exacerbated in soybean grown in eCO2, and there is much more to learn about the underlying mechanisms.

In conclusion, we have demonstrated that soybean basal defense responses and gene expression are altered under eCO2, differentially regulating susceptibility to bacterial, viral, fungal, and oomycete pathogens. In our experiments, we assessed the effect of [CO2] on pathogen growth, however, we did not investigate how pathogen virulence or evolution affects soybean–pathogen interactions under these conditions. In our study, we focused on the impact of one factor, eCO2, on soybean physiology and disease susceptibility. However, eCO2 is not the only environmental factor to consider when predicting the outcome of future climatic conditions on plant health. Increases in temperature, changes in water and nutrient availability, soil pH, photoperiod, and severe weather events are also expected to affect disease susceptibility (Saijo & Loo, 2020). Understanding how combined stresses, in the context of future atmospheric CO2 levels that are likely to occur, affect defense signaling and disease development is a critical question that needs to be investigated further to develop new strategies to mitigate crop losses due to threats imposed by climate change.

Competing interests

None declared.

Author contributions

EK, MB, ASC and KLH performed the experiments. MB, EK and SAW conceived of the experiments. MWB performed the metabolite analysis. YQ and PL performed statistical analysis using the linear mixed models. MAG performed the QuantSeq 3′ mRNA‐Seq data analysis. MB, EK, MAG and SAW wrote the manuscript with contributions from all authors. MB, EK and ASC contributed equally to this work.

Disclaimer

The New Phytologist Foundation remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in maps and in any institutional affiliations.

Supporting information

Fig. S1 Schematic representation of growth chamber conditions.

Fig. S2 Stomatal index on the abaxial leaf surface of soybean.

Fig. S3 Effect of elevated CO2 on growth rate of Pseudomonas syringae pv. tomato DC3000 (PstDC3000).

Fig. S4 Accumulation of salicylic acid and jasmonic acid at 6 h post inoculation with Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea in ambient CO2 and elevated CO2.

Fig. S5 Hierarchical clustering of 21 822 differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.01) responding to Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea at 6 h post inoculation in plants grown in elevated CO2 (550 parts per million (ppm)) or ambient CO2 (419 ppm) conditions.

Fig. S6 Effect of elevated CO2 on the shoot fresh weight and shoot dry weight of soybean plants infected with bean pod mottle virus and soybean mosaic virus.

Fig. S7 Bean pod mottle virus and soybean mosaic virus accumulation at 21 d post inoculation in soybean plants growing in ambient CO2 and elevated CO2.

Fig. S8 Effects of elevated CO2 on root and shoot biomass of soybean plants infected with Fusarium virguliforme.

Fig. S9 Expression of the jasmonic acid marker gene, KTI1, in roots of plants infected with Fusarium virguliforme in ambient CO2 and elevated CO2.

Fig. S10 CO2 concentration does not impact in vitro growth of Fusarium virguliforme.

Fig. S11 Soybean root and shoot biomass is impacted by elevated CO2 in Pythium sylvaticum‐infected plants.

Fig. S12 In vitro growth of Pythium sylvaticum is accelerated under elevated CO2.

Fig. S13 Expression of the salicylic acid marker gene, PR1, in roots of plants infected with Pythium sylvaticum in ambient CO2 and elevated CO2.

Methods S1 QuantSeq 3′mRNA‐Seq data analysis and JA and SA quantification.

Table S1 List of primers and probes used in this study.

Table S2 Sudden death syndrome rating scale of foliar symptoms ranging from 0 to 7.

Table S3 Disease rating scale of Pythium sylvaticum root symptoms.

Table S4 Significantly differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.01) identified by comparing Williams 82 grown at elevated CO2 (550 parts per million (ppm)) vs ambient CO2 (419 ppm) conditions for 21 d.

Table S5 Gene Ontology biological process terms significantly enriched in the STRING (v12) network developed from clusters of differentially expressed genes responding to elevated (550 parts per million (ppm)) vs ambient CO2 conditions (419 ppm) for 21 d.

Table S6 Significantly differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.01) responding to Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea infection (6 h) in plants grown in elevated CO2 (550 parts per million (ppm)) or ambient CO2 (419 ppm) conditions.

Table S7 Gene Ontology biological process terms significantly overrepresented among differentially expressed gene clusters comparing Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea response (Psg v. Mock) in elevated CO2 (550 parts per million (ppm)) and/or ambient CO2 (419 ppm) CO2 conditions (419 ppm).

Table S8 Significantly differentially expressed genes (FDR < 0.01) responding to changes in CO2 (elevated (eCO2) 550 parts per million (ppm) or ambient (aCO2) 419 ppm) in Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea‐infected (6 h) and/or mock‐infected leaves.

Table S9 Gene Ontology biological process terms significantly enriched in the STRING (v12) network developed from clusters of differentially expressed genes responding to elevated (550 parts per million (ppm)) vs ambient CO2 conditions (419 ppm) in Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea and/or mock‐infected leaves at 21 d.

Table S10 Annotation of significantly differentially expressed transcription factors (FDR < 0.01) responding to changes in CO2 (elevated (eCO2) 550 parts per million (ppm) or ambient CO2 419 ppm) in Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea‐infected (6 h) and/or mock‐infected leaves.

Table S11 Identification of transcription factors with overrepresented binding sites among the promoters of differentially expressed genes responding to changes in CO2 (elevated (eCO2) 550 parts per million (ppm), ambient CO2 419 ppm) in Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea‐infected (6 h) and/or mock‐infected leaves.

Table S12 Differentially expressed gene targets of transcription factors with overrepresented binding sites (Table S10) responding to changes in CO2 (elevated (eCO2) 550 parts per million (ppm), ambient CO2 419 ppm) in Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea‐infected (6 h) and/or mock‐infected leaves.

Table S13 Gene Ontology biological process terms significantly overrepresented among differentially expressed gene targets of transcription factors with overrepresented transcription factor binding sites in expression clusters from Pseudomonas syringae pv. glycinea and/or mock‐infected leaves responding to CO2 levels (elevated = 550 parts per million (ppm) vs ambient = 419 ppm).

Please note: Wiley is not responsible for the content or functionality of any Supporting Information supplied by the authors. Any queries (other than missing material) should be directed to the New Phytologist Central Office.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Iowa State University (ISU) DNA Facility for providing analytical instrumentation and technical expertise, and the ISU WM Keck Metabolomics Research Laboratory (RRID:SCR_017911) for providing analytical instrumentation. We thank Gwyn Beattie (ISU) for the PstDC3000 hrcC‐ strain, Leanor Leandro and Vijitha K. Silva (ISU) for SDS inoculum and inoculation protocols, and Alison Robertson and Clarice Schmidt (ISU) for P. sylvaticum inoculum and inoculation protocols. This work was supported in part by the Iowa Soybean Research Center, the ISU Plant Sciences Institute, USDA NIFA Hatch Project 4308, the ISU College of Agriculture and Life Sciences and by USDA‐ARS projects 5030‐21220‐007‐000D (Leveraging Crop Genetic Diversity and Genomics to Improve Biotic and Abiotic Stress Tolerance in Soybean) and 0500‐00093‐001‐00‐D (SCINet). Ekkachai Khwanbua is supported by an Anandamahidol fellowship from the government of Thailand. Mention of trade names or commercial products in this publication is solely for the purpose of providing specific information and does not imply recommendation or endorsement by the USDA. USDA‐ARS is an equal opportunity employer and provider.

See also the Commentary on this article by Sanchez‐Lucas & Luna, 246: 2380–2383.

Data availability

The RNA‐seq reads for QuantSeq dataset 1 and dataset 2 were deposited in NCBI under BioProject PRJNA1017882 and PRJNA1017884, respectively. The raw data and statistical reports from R that underlie the graphs in Figs 1, 3, 4, and 7, 8, 9 and Figs S2–S4 and S6–S13 were deposited at the Iowa State University DataShare, and they can be accessed using this Doi: 10.25380/iastate.27287847. The authors declare that any additional supporting data for this work can be found in the manuscript and its Supporting Information.

References

- Aguilar E, Allende L, Del Toro FJ, Chung B‐N, Canto T, Tenllado F. 2015. Effects of elevated CO2 and temperature on pathogenicity determinants and virulence of potato virus X/potyvirus‐associated synergism. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions 28: 1364–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahammed GJ, Li X. 2022. Elevated carbon dioxide‐induced regulation of ethylene in plants. Environmental and Experimental Botany 202: 105025. [Google Scholar]

- Ainsworth EA, Long SP. 2021. 30 years of free‐air carbon dioxide enrichment (FACE): what have we learned about future crop productivity and its potential for adaptation? Global Change Biology 27: 27–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akbar S, Wei Y, Zhang M‐Q. 2022. RNA interference: promising approach to combat plant viruses. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 23: 5312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Amari K, Huang C, Heinlein M. 2021. Potential impact of global warming on virus propagation in infected plants and agricultural productivity. Frontiers in Plant Science 12: 649768. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arraes FB, Beneventi MA, Lisei de Sa ME, Paixao JF, Albuquerque EV, Marin SR, Purgatto E, Nepomuceno AL, Grossi‐de‐Sa MF. 2015. Implications of ethylene biosynthesis and signaling in soybean drought stress tolerance. BMC Plant Biology 15: 213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bao Y, Zarecor S, Shah D, Tuel T, Campbell DA, Chapman AVE, Imberti D, Kiekhaefer D, Imberti H, Lübberstedt T et al. 2019. Assessing plant performance in the Enviratron. Plant Methods 15: 117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bazinet Q, Tang L, Bede JC. 2022. Impact of future elevated carbon dioxide on C3 plant resistance to biotic stresses. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions 35: 527–539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bebber DP, Ramotowski MAT, Gurr SJ. 2013. Crop pests and pathogens move polewards in a warming world. Nature Climate Change 3: 985–988. [Google Scholar]

- Beyer SF, Bel PS, Flors V, Schultheiss H, Conrath U, Langenbach CJG. 2021. Disclosure of salicylic acid and jasmonic acid‐responsive genes provides a molecular tool for deciphering stress responses in soybean. Scientific Reports 11: 20600. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bilgin DD, Aldea M, O'Neill BF, Benitez M, Li M, Clough SJ, DeLucia EH. 2008. Elevated ozone alters soybean‐virus interaction. Molecular Plant–Microbe Interactions 21: 1297–1308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bredow M, Sementchoukova I, Siegel K, Monaghan J. 2019. Pattern‐triggered oxidative burst and seedling growth inhibition assays in Arabidopsis thaliana . Journal of Visualized Experiments 147: e59437. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]