Abstract

Background

Belongingness is considered an important factor contributing to a clinical learning environment for good learning outcomes and higher levels of satisfaction among nursing students. This study investigated the mediating influence of a sense of belonging on the relationship between the clinical learning environment and perceived stress.

Methods

This cross-sectional study was conducted using a convenience sample of 455 internship nursing students from August to November 2023. Data were collected using the Belongingness Scale-Clinical Placement Experience, Perceived Stress Scale, Clinical Learning Environment Scale, and Supervision Scale.

Results

The mean of nursing internship students’ belongingness was 121.27 ± 14.95. The majority of participants had moderate stress levels (83.3%). The direct effects analysis revealed a significant negative correlation between the clinical learning environment, supervision, and perceived stress (β = − 0.484, p < .001). Clinical learning environment and supervision had a positive direct effect on belongingness (β = 0.499, p < .001). Belongingness had a negative effect on perceived stress (β = − 0.163, p = .003). According to further indirect effect analysis (β = − 0.081, p = .003), the association between the clinical learning environment and supervision-perceived stress was mediated by belongingness. Overall, the results showed that felt stress was considerably affected by the clinical learning setting and supervision (β = − 0.565, p < .001).

Conclusion

A sense of belonging is a critical factor for alleviating the impact of an overwhelming environment. These findings emphasize the need to provide a positive environment that promotes the health of internship nursing students.

Clinical trial number

Not applicable.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12912-025-03222-6.

Keywords: Perceived stress, Clinical learning environment, Belongingness, Nursing internship students

Introduction

Nursing education comprises theory and practice, and most nursing students’ educational experiences involve clinical learning [1]. The clinical learning environment is a crucial part of nursing education because it helps students put the information and abilities acquired during their studies into use in the real world and construct their professional identities [2, 3]. The clinical learning environment is a clinical healthcare setting in which students complete their clinical rotations [4]. A vital part of nursing education, clinical training, connects student nurses’ theoretical knowledge with real-world applications [3, 5]. It offers nursing students a special opportunity to apply what they have been taught in the classroom, polish critical clinical skills, and become fully immersed in real healthcare environments [6, 7]. In addition to influencing students’ clinical learning outcomes, internship readiness, and job satisfaction [4], the clinical learning environment (CLE) is a dynamic web of forces that exists within the clinical setting [8].

Higher levels of self-assessed competency and satisfaction with the clinical practicum and nursing education program are associated with graduating nursing students’ positive evaluations of the clinical learning environment, which may lead to a decreased intention to quit the program [9].

In clinical settings, nursing interns are frequently exposed to unforeseen circumstances that can lead to elevated stress and anxiety [10–12]. These circumstances may include managing difficult patients and their families, frequent observation and evaluation by teachers and clinical staff, a mismatch between the duration of internship courses and predetermined goals [8], errors in patient care and equipment handling, and unfamiliar situations in clinical areas [10, 13].

Stress development has been linked to negative learning environments among nursing students in Sri Lanka [10]. Additionally, a positive and good clinical learning environment may increase nursing students’ future intention to work as nurses [8].

The internship period is crucial for building nursing competencies and bridging the gap between theoretical education and clinical practice. In Egypt, after completing a four-year undergraduate program, nursing students must undergo a one-year internship, usually at university hospitals where they rotate through various units each month. These rotations often include different hospital units, such as general, medical, surgical, coronary, and burn units, as well as departments, such as the emergency room, neonatal ICU, and hemodialysis. During their internships, students provided direct bedside care under the supervision of experienced mentors and nurses. At the start of the internship year, they received theoretical refreshers and orientation on current regulations to ensure they were well prepared for practical challenges ahead.

The idea of belongingness in clinical education is defined as a highly subjective and contextually mediated experience that varies depending on how safe, accepted, valued, and respected a person feels by a specific group; how connected they are to the group; and how their values match the group’s professional values [14]. A sense of belonging plays a crucial role in internship students’ mental well-being by making them feel needed, accepted, and valued [15]. When nursing students experience a strong sense of belonging in their clinical environment, they experience less stress and anxiety, which boosts their confidence and cognitive development [16]. Conversely, those struggling with belonging often feel isolated and overwhelmed, leading to increased nervousness and self-doubt. Stress is a significant factor in clinical experiences, as students are exposed to new and intense environments filled with unfamiliar sights, sounds, and responsibilities [17]. Many clinical placements are overcrowded and understaffed, leaving students uncertain and anxious. The shortage of faculty, clinical sites, and preceptors further adds to these challenges, often subjecting students to unsupportive or even hostile behavior from staff nurses [18]. This study addresses this gap by exploring how a strong sense of belonging can act as a buffer against stress and help students feel secure, engaged, and capable of thriving in demanding clinical settings.

One of the most crucial requirements for students to demonstrate appropriate performance in learning environments is a sense of belonging [16]. Furthermore, belongingness in the clinical learning environment is considered an important factor contributing to good learning outcomes and higher levels of satisfaction among nursing students [15]. Improved learning, perseverance, and graduation rates and, most significantly, the growth of a stronger sense of nursing identity and self-actualization are linked to students feeling more integrated into the community [19].

However, it has been shown that nursing students who feel like they belong have better physical and mental health, which reduces stress and anxiety and increases self-confidence [20]. Exploring how belonging, stress, and the clinical learning environment affect nursing interns is essential for their career growth and well-being. When internship nursing students feel that they belong, they are more confident, engaged, and likely to stay in the profession. This provides a deeper understanding of how these experiences shape career aspirations. However, excessive stress can negatively affect performance and mental health [18]. A positive clinical environment with good supervision helps them build skills, think critically, and feel more satisfied with their roles. This study can provide valuable insights into reducing stress, improving mentorship, and creating a better learning experience, ultimately leading to stronger, more resilient nurses, and better patient care. In conclusion, we hypothesized that a positive clinical learning environment would enhance nursing students’ sense of belonging and thus reduce their perceived stress.

Theoretical framework

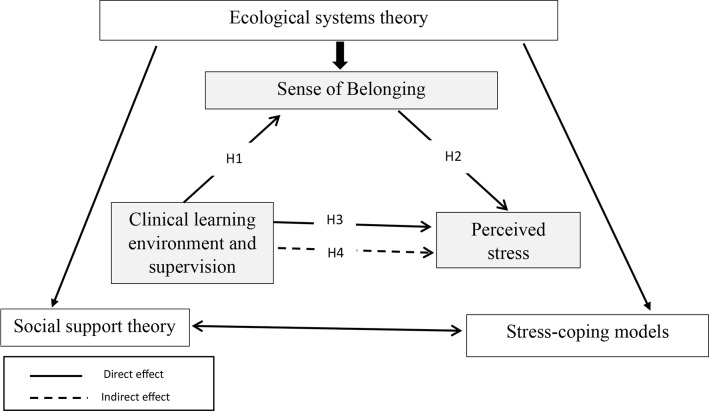

The framework of this study combines ideas from ecological systems theory [21], social support theory [22], and stress-coping models to explain how nursing students’ experiences in clinical settings affect their overall well-being [23]. This suggests that a supportive clinical environment and effective supervision create conditions in which students feel a strong sense of belonging, which in turn helps lower their stress levels. In this view, the immediate clinical setting, where students interact with mentors and peers, is essential for fostering acceptance and integration, as explained by the ecological systems theory. Social support theory adds that feeling connected and valued not only buffers stress, but also builds resilience, enabling students to handle high-pressure situations better [22]. Finally, stress-coping models indicate that when students receive both emotional and practical support, they are better equipped to face the challenges of clinical placements [23]. Overall, this integrated framework highlights the key role of belonging, enhanced by a positive learning environment and strong supervision, in reducing stress and promoting professional growth (Fig. 1). Accordingly, this study proposes the following hypotheses:

Fig.1.

Theoretical framework of the study

Hypothesis 1

There is a positive relationship between clinical learning environment and supervision, and sense of belongingness among nursing internship students.

Hypothesis 2

There is a negative relationship between sense of belongingness and perceived stress among nursing internship students.

Hypothesis 3

There is a negative relationship between clinical learning environment and supervision and perceived stress among nursing internship students.

Hypothesis 4

Sense of belongingness mediates the relationship between clinical learning environment and supervision, and perceived stress among nursing internship students.

Methods

Study aims

This study aimed to examine the clinical learning environment and supervision of nursing internship students, as well as their sense of belonging, perceived stress, and the role that the sense of belonging plays as a mediator in the relationship between perceived stress and the clinical learning environment.

Study design

Descriptive, cross-sectional research was used.

Setting

This study was conducted in the Faculty of Nursing at Damanhour University, Egypt, from August to November 2023. This public university was established in 2010, after its separation from Alexandria University. Each year, nearly one thousand students graduate after completing four academic years and a training internship. The clinical training environment during the 12-month internship involved rotations across various units, under the supervision of clinical instructors and diverse medical staff. Trainees are placed in private or public hospitals affiliated with the Egyptian Health Authority, which is established through formal academic contracts between the Faculty of Nursing at Damanhour University and these hospitals. The placements included rotations in general, cardiac, and coronary heart disease intensive care units at the National Medical Institute in Damanhour, Kafr El-Dawar, Itay El-Baroud, and Kom Hamada, as well as in the intensive care units at Children’s Cancer Hospital Egypt 57,357 and Magdi Yacoub Hospital in Aswan. Assignment to these hospitals was based on each student’s cumulative grade point average over the four-year academic programme.

Study participants

A convenience sample of 455 internship nursing students was included in the study after sample size calculation. All students who were expected to graduate in 2022/2023, during the period of internship training at the hospitals, who had completed at least ten months of their internship academic year, were included in the study to ensure they had full experience over different units, and approved to participate were involved in this study. Students who had training for less than 10 months or declined to participate were excluded. The researchers used Open Epi Version 3, an open-source calculator, to ascertain the sample size necessary for their study. The total number of nursing internship students in the study hospitals was 1220. The calculation used the following parameters: the presumed percentage frequency (p) of the outcome factor in the population was set at 50%, with a margin of error of 5%. The confidence level was set at 99%, and a design effect (DEFF) of 1 was applied, which is relevant for cluster surveys. Based on these characteristics, a minimum sample size of 430 was determined. The questionnaire was distributed to 500 nursing internship students, of whom 455 completed the questionnaire, with a response rate of 91%.

Tools of data collection

Data were collected in four parts: demographic characteristics, belongingness scale–clinical placement experience (BES-CPE), Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-14), and Clinical Learning Environment and Supervision (CLES).

Part I: Demographic characteristics

This section contains items regarding participants’ demographics and job-related data, including age, gender, marital status, previous GPA grade, and number of shift hours.

Part II: Belongingness scale-clinical placement experience (BES-CPE)

The 34 items of the BES-CPE, created by Levett-Jones (2009) [24], assess students’ emotions, thoughts, and behaviors that represent the three main components or subscales of belongingness: esteem, connectivity, and efficacy. Esteem refers to feeling safe, included, appreciated, and respected by the other members of a group. Connectedness is embraced, and one feels like a member of a group. Efficacy describes the actions performed to improve a person’s sense of belonging [25]. Active and passive interactions, that is, what the person receives or believes they receive from others, as well as the constructive activities they take part in to either increase or respond to belongingness, are also reflected in these elements. To reduce the response bias, the items were written in both positive and negative terms. The elements with negative wording (Q10, 14, 22, and 26) were reversed. The instrument was self-reported using a five-point Likert scale ranging from (1) never true, (2) to (3) sometimes true, (4) often true, and (5) always true. A higher degree of belonging is indicated by a higher score. The overall BES-CPE score ranges from 34, indicating low belongingness, to 170, indicating high belongingness [16].

The internal consistency reliability of each subscale was assessed using Cronbach’s alpha (after eliminating poorly fitting items). The subscales and the BES-CPE both had high reliability coefficients: the efficacy subscale was 0.81, the connectedness subscale was 0.82, the self-esteem subscale was 0.91, and the BES-CPE was 0.92 [24]. Internal consistency was acceptable in this study, as revealed by a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.85.

Part III: Perceived stress scale (PSS-14)

The PSS-14 is one of the most widely used instruments for measuring stress perceptions by asking about feelings and thoughts during the last month, and has good psychometric properties. The method was developed by Cohen et al. (1983) [26]. Each item is scored from never (0) to almost always (4) on a 5-point Likert scale, with total scores ranging from 0 to 56, with higher scores indicating higher stress [20]. Items 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, and 13 were coded in the reverse order. The stress levels were categorized as low, moderate, or high. Low stress was defined as scores ranging from 0 to 18, moderate stress as scores ranging from 19 to 37, and high stress as scores ranging from 38 to 56 [27]. The PSS-14 exhibits strong test-retest reliability (r = .55 over a 6-week period, and α = 0.84 to 0.86 over a 2-day period) [26]. Internal consistency was acceptable in this study, as revealed by a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.89.

Part IV: Clinical learning environment and supervision (CLES)

The original version of the CLES was developed in 2002 as a tool to assess the clinical learning environment for nursing students in Finland [28]. Comprehensive literature studies, audits, and earlier work of the Finnish research group served as the foundation for CLES’ development of CLES. The 27 questions on the CLES scale were divided into five categories: ward atmosphere (items 1–5), leadership style of the ward manager (items 6–9), premises of nursing care in the ward (items 10–13), premises of learning in the ward (items 14–19), and supervisory relationship (items 20–27) [28, 29]. Using a five-point Likert scale (1 = completely disagree; 2, disagree somewhat; 3, neither agree nor disagree; 4, somewhat agree, and 5 = completely agree), the students answered these statements with total scores ranging from 27 to 125. To convert the total scores to percentages for each participant, the questionnaire scores were subtracted by 27, and the results were divided by 108 and multiplied by 100. The overall response rate of each participant ranged from 0 to 100%. The percentage was then categorized as inadequate, moderate, and adequate, with scores of less than 40%, 40-70%, and > 70%, respectively [30]. The alpha coefficient of the subdimension for measuring students’ total satisfaction (three items) was 0.78 [29]. Internal consistency was acceptable in this study, as revealed by a Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of 0.95.

Data collection phase

After obtaining official permission from the administrative authority of the nursing faculty to collect data, an electronic online questionnaire was integrated into the Google survey tool (Google Forms) and sent to internship program supervisors to internship nursing student groups through university social media channels. To ensure the comprehensibility and usability of the survey, 45 nursing students participated in the pilot study. Overall, the results showed that the questionnaire was straightforward to read, understand, and comprehend and that it took an average of 15 to 20 min to complete. No modifications or changes were made to the manuscript. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for the BES-CPE, PSS-14, and CLES were 0.853, 0.894, and 0.952, respectively. Because the online survey did not move on to the next question until the previous one was answered, the item nonresponse rate was reduced. Data were entered into an Excel spreadsheet and subjected to statistical analysis at the end of the collection period.

Ethical consideration

The Research Ethics Committee (REC) of Damanhur University’s Faculty of Nursing approved this study (IRB: 69 on December 15, 2022). This study followed the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki and its later amendments, or comparable ethical standards. The first page of the online survey link contained an explanation that all participants were required to read carefully before completing the survey and a consent form by clicking an agreement checkbox before proceeding with the survey to ensure ethical compliance. This explanation included information about the study’s purpose and content, the right to withdraw from research participation, confidentiality, anonymity, the fact that no personally identifiable information was collected, and consent to participate. The study followed the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES) guidelines by carefully designing and testing an online questionnaire before its launch. The recruitment process was transparently documented, and technical safeguards were put in place to avoid duplicate responses and ensure secure data storage and analysis, thereby enhancing the overall transparency and reliability of the findings [31]. The aim of the study was communicated to the participants, ensuring that all collected data would be used solely for research purposes.

Data analysis

IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 27.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) was used for data analysis. The mean and standard deviation for normally distributed continuous variables and frequencies and proportions for categorical variables were used to depict the sociodemographic characteristics of the nursing internship students. To examine the differences between the mean scores of belongingness, perceived stress, and clinical learning environment for dichotomous variables, an independent sample t-test was employed. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test the differences between the means of the independent variables with more than two categories. The association between the mean scores of the dependent variables was examined using Pearson’s correlation coefficient. A structural equation modeling approach with the bootstrap method (2000 replicates, 95% bias-corrected confidence interval) was employed in AMOS 22.0 to test the mediating effect of belongingness on the relationship between the clinical learning environment, supervision, and perceived stress. Model fit indices such as the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), and Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) are typically used to assess the adequacy of the model. These indices could not be reliably computed in this analysis because of the presence of Heywood cases, where parameter estimates such as variances become negative or correlations exceed 1, indicating estimation issues, which led to implausible parameter estimates and consequently unreliable fit indices. Handling of Heywood ؤases, marked by implausible estimates like negative variances, undermined traditional fit indices (e.g., CFI, RMSEA) in our structural equation modeling analysis. We attempted remedies such as model respecification, variance constraints, and robust estimation methods (e.g., MLR), but the issues persisted, making fit indices unreliable. Instead, the validity of the model was assessed through the significance and magnitude of the path coefficients (β), standard errors, and critical ratios, which provided strong evidence of the hypothesized relationships between the CLES, belongingness, and perceived stress (e.g., direct effect: β = − 0.484, p < .001; indirect effect: β = − 0.081, p = .003). The direct, indirect, and total effects were statistically significant (p < .05), supporting the robustness of the mediation model [32, 33]. Statistical significance was set at p < .05.

Results

As described in Table 1, the majority of participants were ≤ 22 years old, female, and single (62.9%, 65.9%, and 88.6%, respectively). More than two-thirds (65.3%) of the participants had excellent academic performance (GPA) during their study, and more than half (57.8%) worked for 6 h. Nursing internship students with excellent grades significantly expressed a sense of belongingness (p = .015) and clinical learning environment scores (p < .001) more than their counterparts. In contrast, there were no significant relationships between age, sex, marital status, working hours, and dependent variables (p > .05), Table 1.

Table 1.

The relationship between nursing internship students’ characteristics and study variables

| Variables | n | % | Belongingness | t/f (p-value) |

Perceived stress | t/f (p-value) |

Clinical learning environment | t/f (p-value) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | |||||||||

| ≤ 22 | 286 | 62.9 | 121.22 ± 14.80 | − 0.80 (0.936) | 35.04 ± 8.39 | 0.735 (0.463) | 103.79 ± 18.28 | − 0.277 (0.782) | |

| > 22 | 169 | 37.1 | 121.34 ± 15.23 | 34.47 ± 7.10 | 104.30 ± 20.08 | ||||

| Gender | |||||||||

| Male | 155 | 34.1 | 121.81 ± 15.08 | -563 (0.574) | 34.71 ± 8.48 | 0.230 (0.818) | 106.38 ± 20.05 | 1.943 (0.053) | |

| Female | 300 | 65.9 | 120.98 ± 14.90 | 34.89 ± 7.65 | 102.75 ± 18.26 | ||||

| Marital status | |||||||||

| Single | 403 | 88.6 | 120.87 ± 14.88 | − 0.1.599 (0.120) | 34.99 ± 8.11 | 0.1.160 (0.247) | 103.78 ± 18.82 | − 0.635 (0.526) | |

| Married | 52 | 11.4 | 124.30 ± 15.26 | 33.63 ± 6.36 | 105.55 ± 20.03 | ||||

| GPA | |||||||||

| Fair | 5 | 1.1 | 119.40 ± 14.11 | 3.538 (0.015) | 36.80 ± 13.66 | 2.070 (0.103) | 98.80 ± 17.93 | 8.222 (< 0.001) | |

| Good | 36 | 7.9 | 117.25 ± 11.50 | 37.33 ± 10.07 | 91.36 ± 24.91 | ||||

| Very good | 117 | 25.7 | 118.43 ± 15.53 | 35.45 ± 9.15 | 101.62 ± 19.25 | ||||

| Excellent | 297 | 65.3 | 122.90 ± 14.89 | 34.25 ± 6.92 | 106.53 ± 17.30 | ||||

Table 2 shows that the mean score for nursing internship students’ belongingness was 121.27 ± 14.95. The majority of them had moderate stress levels (83.3%) with a total mean of 34.83 ± 7.93. On the other hand, the majority (61.8%) had adequate levels of clinical learning environments and supervision, Table 2.

Table 2.

The level of nursing internship students’ belongingness, perceived stress, and clinical learning environment and supervision

| Variable | n (%) | Mean ± SD | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belongingness | 121.27 ± 14.95 | ||

| Esteem | 37.53 ± 4.85 | ||

| Connectivity | 45.63 ± 5.80 | ||

| Efficacy | 34.29 ± 5.57 | ||

| Perceived stress | 34.83 ± 7.93 | ||

| Low-stress (0–18) | 1 (0.2) | ||

| Moderate-stress (19–37) | 379(83.3) | ||

| High-stress (38–56) | 75(16.5) | ||

| Clinical learning environment and supervision | 103.98 ± 18.95 | ||

| Inadequate (< 40%) | 28(6.2) | ||

| Moderate (≥ 40 < 70%) | 146 (32.1) | ||

| Adequate (≥ 70%) | 281 (61.8) |

Table 3 shows a significant negative correlation between participants’ perceived stress and belongingness, and the clinical learning environment and supervision (r=-.405, p < .001, and r=-.566, p < .001, respectively). In contrast, there was a significant positive correlation between belongingness and clinical learning environment and supervision (r = .499, p < .001), Table 3.

Table 3.

Correlation matrix between the studied variables

| Variables | Belongingness | Perceived stress | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Belongingness | Pearson’s r | 1 | |

| p-value | |||

| Perceived stress | Pearson’s r | − 0.405** | 1 |

| p-value | < 0.001 | ||

| Clinical learning environment and supervision | Pearson’s r | 0.499** | − 0.566** |

| p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

**. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level (2-tailed)

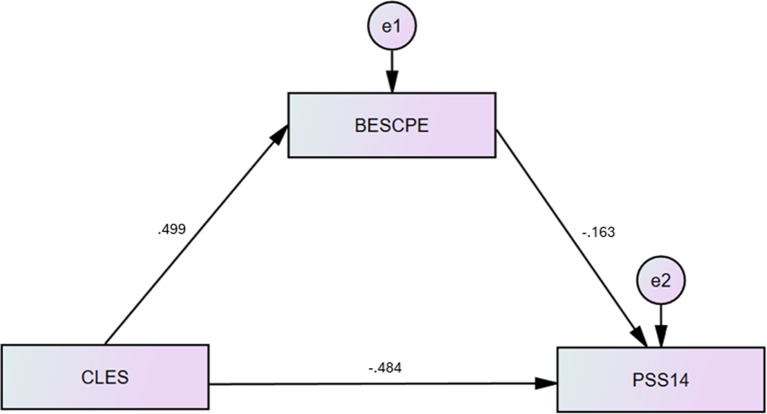

Structural equation modeling

Table 4 and Fig. 2 illustrate the direct, indirect, and total effects of the clinical learning environment and supervision on perceived stress mediated by belongingness among the nursing internship students. The direct effects analysis revealed a significant negative correlation between the clinical learning environment, supervision, and perceived stress (β = − 0.484, p < .001). Clinical learning environment and supervision had a positive direct effect on belongness (β = 0.499, p = .001). Belongingness had a negative effect on perceived stress (β = − 0.163, p = .003). According to further indirect effect analysis (β = − 0.081, p = .003), the association between the clinical learning environment and supervision-perceived stress was mediated by belongingness. Overall, the results showed that felt stress was considerably affected by the clinical learning setting and supervision (β = − 0.565, p < .001) (Table 4).

Table 4.

Direct, indirect, and total effects of clinical learning environment and supervision on perceived stress mediated by belongingness among nursing internship students

| Path | β | CI (95%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Direct effect | |||

| Clinical learning environment and supervision → Perceived stress | − 0.484 | − 0.585/-0.365 | < 0.001 |

| Clinical learning environment and supervision→ Belongingness | 0.499 | 0.428/0.563 | 0.001 |

| Belongingness→ Perceived stress | − 0.163 | − 0.254/-0.072 | 0.003 |

| Indirect effect | |||

| Clinical learning environment and supervision → Belongingness → Perceived stress | − 0.081 | − 0.136/-0.034 | 0.003 |

| Total effect | |||

| Clinical learning environment and supervision → Perceived stress | − 0.565 | − 0.631/-0.488 | < 0.001 |

CI: Confidence Interval

Fig. 2.

Mediating effect of belongingness on the relationship between clinical learning environment and supervision and perceived stress. BES-CPE: Belongingness Scale-Clinical Placement Experience; PSS-14: Perceived Stress Scale; CLES: Clinical Learning Environment and Supervision

Discussion

This study aimed to investigate the clinical learning environment, sense of belonging, and level of perceived stress among nursing interns. This is especially relevant to the mediating influence of a sense of belonging on the connection between the clinical learning environment and the perceived level of stress. The results of the current study revealed that nursing students with high academic performance achieved a higher sense of belonging and clinical learning environment scores than the other groups. Conversely, demographic variables such as age, sex, marital status, and hours worked each week did not have a significant relationship with any of the dependent variables. These results reinforce earlier work that has argued for the vital role of a conducive clinical learning environment in nursing students’ sense of belonging. It has been reported that nursing students experience great problems owing to accentuated restrictions on online education requirements, along with a deficit in the real education process [34]. In contrast, an earlier study highlighted the positive effects of structured mentorship programs on the reduction of perceived stress and improvement in students’ belongingness and self-esteem [18]. This demonstrates that, even if the clinical learning environment is critical, attention and support from other sources are paramount. This includes mentorship, which is also crucial for reducing stress and enhancing feelings of belonging among nursing students. As such, it is likely that even if the clinical learning environment is given a great deal of focus, it is still useful and there is a need to implement it. Mentoring and peer support in the psychological and emotional well-being of students were better.

The non-significant relationships between the demographic factors and dependent variables corresponded to the findings of a previous study. For example, stressors are mainly associated with workload and not demographic features [35]. This suggests that efforts directed towards promoting a clinical learning environment should be centered on managing workload and stress. Indeed, it should not be a demographic variable that is unlikely to have a significant effect on the student experience. In this context, further emphasis should be placed on enhancing students’ clinical learning approach through the development of positive emotional attachment.

Nurse-intern students reported an average belongingness score and a moderate level of stress. In addition, the students rated their overall clinical learning environment and supervision as adequate. This implies that belongingness and the presence of a healthy and non-harassing clinical environment emerged as important factors in the experience of nursing students in internships during such crucial periods. These results are consistent with those of other studies that assert that belongingness is a significant factor in nursing students’ learning lives. In particular, scholars posited the “Ascent to Competence” model where “Students feel safe and secure to practice clinically only when they have a sense of belonging” [36].

As social gatekeepers of belongingness boundaries, clinical instructors play a crucial role in creating engaging environments. Students are more likely to learn as fully as possible and develop their clinical skills. This underscores the importance of the student-instructor bond in fostering effective learning [37]. In contrast, other scholars have adopted a much more complex view of belonging and perceived stress, and the functional relationship between the two. A previous study found that nursing students’ interactions with their colleagues significantly enhanced or undermined their feelings of inclusion in the profession [14]. If such interactions are aggressive or insufficiently supportive, students may find themselves in heightened stress premiums. This corroborates the current research observation that most students, although feeling a sense of belonging, still reported moderate stress levels. As such, it indicates that, whereas belongingness is crucial, it may not be enough to lower stress levels. This is particularly true when the clinical learning environment is not supportive, or when there are other stressors.

The results of the current study showed notable relationships in the areas of belongingness, perceived stress, and clinical learning environment among nursing internship students. In particular, the correlation between belongingness and perceived stress is highly negative. This means that, as the belongingness of students increases, their stress easily decreases. These observations are important for correlating with the improvement in the feeling of belonging among students in their environment. Likewise, perceived stress and the clinical learning environment were negatively correlated. This implies that a favorable clinical environment reduces stress in individuals. The following observations correspond with the literature, which highlights the significance of belonging to students in clinical educational settings: a supportive environment encourages nursing students to develop a sense of belonging, which is important for their growth as students [15].

This study underlines that if students have a sense of identity, they feel that it is important in clinical settings. In fact, they tend to be more engaged in learning activities, and lower stress levels have been reported [15]. These findings corroborate the current study’s outcome, which establishes that a positive clinical learning environment is associated with improved student feelings of belonging and reduced stress levels [38]. Conversely, some studies found a more complicated relationship between belongingness and perceived stress. It has been reported that although belongingness indicates that some of the associated outcomes are counterproductive, this is because the sense of belonging is subjective and usually relative [14]. Previous research found that students were able to establish that while there are benefits of being a part of the group, stress is still accessible. This is due to negative interactions with peers and hindering belonging to the group definition [14]. Although it is important to promote a sense of belonging, it does not need to move on its own without efforts to promote healthy interactions in a clinical setting. Therefore, nursing education programs should define the essence of nursing practices and provide practical settings. The rationale for such an approach lies in the fact that well-orchestrated mentorship programs would ensure that clinical learners are supported by nurses during their clinical practice. Nursing students’ stress and anxiety levels decrease when knowledgeable mentors are present during their clinical experience, thereby enhancing learning outcomes [39].

The findings of the present study revealed relationships between clinical learning environment, sense of belonging, and perceived stress among nursing interns. In particular, the clinical learning environment had a statistically significant negative relationship with stress levels, whereas the clinical learning environment and belongingness were positively related, and vice versa. In addition, a sense of belonging plays a significant mediating role in the association between the clinical learning environment and perceived stress, suggesting that a supportive clerical environment averts stress by improving students’ sense of belonging [20]. The results of the present study support the existing literature on clinical learning environment as an important area for nursing students’ development of a sense of belonging.

One study pointed out that students should not only be given knowledge but also invest in a practical supportive clinical setting that is critical in enhancing their levels of learning [40]. Similarly, nursing students who related themselves to the domain during clinical placements expressed higher satisfaction and self-efficacy. This further strengthens the notion of belongingness as a part of learning [16]. However, belonging is not always linearly associated with stress. For example, Patel et al. (2022) found that incivility, particularly from staff nurses, can cause bullying among students, thereby affecting belongingness, which may increase student stress [41]. This suggests that although a favorable clinical learning atmosphere may improve students’ belongingness and lower stress, negative interactions may reverse their merits, which indicates that a more comprehensive approach to creating support is needed. As such, the nursing education programs should be reformed in such a way that a ‘safe’ clinical learning environment that cultivates students’ sense of belonging can be created. This can be achieved through mentorship provisions by nurse colleagues [42]. This can help to build students’ self-efficacy and reduce the physical and emotional costs of stress, thereby leading to more effective learning. In addition, nurse educators must understand that there is potential for stress, even in environments that promote reading. Courses and programs for students teach them the proper relief of applicable stress in practical settings. Therefore, relieving stressors, even in clinical settings, is important for effective teaching, learning, and practice [35].

Limitations of the study

While this study contributes to the limited body of knowledge regarding the relationship between clinical settings, belongingness, and stress among nursing interns, it has certain limitations. The complex interplay between clinical environments, belongingness, and stress, particularly concerning nursing interns, was considered in-depth for the first time in this study. Nevertheless, one must approach the conclusions with great caution because of the methodological limitations. Causal pathways cannot be established because of the cross-sectional design, which is useful for the initial data collection. For example, there are relationships that were identified, but no definitive conclusions can be drawn about whether certain characteristics of a clinical setting have a direct effect on belongingness while feeling stressed or whether pre-existing levels of stress or belongingness impact how interns view the clinical setting. Additionally, this design does not provide an answer to how these elements interact over the course of an internship.

Limiting the study to a single institution limits the generalizability of our results. The particular culture, along with the support systems and clinical settings at this institution, is unlikely to capture the variation in educational institutions for nursing interns. As a result, correlational phenomena may not be accurate in institutions with different organizational designs or teaching methodologies. Convenience sampling also increases the risk of selection bias. Interns who opted to volunteer to participate may differ in some systematic way from those who chose not, which would result in the data being biased towards those who have greater availability, stronger viewpoints, or specific experiences that make participation less representative.

Moreover, self-reported data are associated with concerns regarding social desirability bias. Participants may have attempted to provide what they perceived as more socially acceptable responses, such as downplaying negative encounters and exaggerating positive ones concerning their well-being within the clinical setting. This could result in an unrealistic, exuberant representation of the situation, which could mask the actual level of distress or difficulties that interns had to cope with. Future studies should focus on random sampling from multiple institutions to improve the external validity of the outcomes. Moreover, the use of self-reported and objective indicators of stress could reduce the effects of the social desirability bias. Other studies could look at possible mediating or moderating variables of these relationships to better understand internal experience. These limitations should be addressed to draw appropriate conclusions regarding the findings and to inform future research in this field.

Finally, this study did not account for potential confounders that may need to be considered in future studies, such as previous clinical experience, coping style, and quality of mentorship. While our results showed strong associations between the CLES, belongingness, and perceived stress (e.g., β = -0.484, p < .001), these unmeasured variables might have influenced the findings. Future research should include these factors to enhance our understanding and to confirm our results. Finally, there is an absence of traditional model fit indices (e.g., CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR). Heywood cases prevented reliable fit indices (e.g., CFI, RMSEA), limiting model fit assessment. Future studies should replicate these findings with refined models or larger samples to ensure that model fit can be adequately evaluated.

Conclusion

Nursing students reported greater belongingness and better clinical learning experience. Although demographic characteristics were not statistically meaningful predictors, supportive clinical culture contributed to a sense of belonging and decreased stress. A sense of belonging is a critical factor in alleviating the impact of an overwhelming environment. These findings emphasize the need to provide a positive environment that promotes the health of internship nursing students.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all nursing internship students who participated in this study.

Abbreviations

- CLE

Clinical learning environment

- BES-CPE

Belongingness Scale-Clinical Placement Experience

- PSS

Perceived stress scale

Author contributions

Sameer A. Alkubati: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Resources, Validation, Visualization, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Talal Ali Hussein Alqalah; Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Basma Salameh; Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Ahmed Loutfy: Investigation, Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Wesam T. Almagharbeh; Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing, Eddieson Pasay-an; Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Abdelaziz Hendy; Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation. Mohamed A. Zoromba; Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Heba E. El-Gazar; Writing – original draft, Writing – review & editing. Maysa Abdalla Elbiaa; Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation. Shimmaa M. Elsayed; Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology.

Funding

No funding.

Data availability

The data are available at request from the corresponding author.

Declarations

Ethical consideration

The Research Ethics Committee (REC) of Damanhur University’s Faculty of Nursing approved this study (IRB: 69 on December 15, 2022). The study adhered to the guidelines outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The first page of the online survey link contained an explanation that all the participants were required to read carefully before completing the survey. This explanation included information about the study’s purpose and content, the right to withdraw from research participation, confidentiality, anonymity, the fact that no personally identifiable information was collected, and their consent to participate. The aim of the study was communicated to the participants, ensuring that all collected data would be used solely for research purposes.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.Arkan B, Ordin Y, Yılmaz D. Undergraduate nursing students’ experience related to their clinical learning environment and factors affecting to their clinical learning process. Nurse Educ Pract. 2018;29:127–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Woo MWJ, Li W. Nursing students’ views and satisfaction of their clinical learning environment in Singapore. Nurs Open. 2020;7(6):1909–19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Alrasheeday AM, Alkubati SA, Alqalah TAH, Alrubaiee GG, Alshammari B, Almazan JU, Abdullah SO, Loutfy A. Nursing students’ perceptions of patient safety culture and barriers to reporting medication errors: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2025;146:106539. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rodríguez-García MC, Gutiérrez-Puertas L, Granados-Gámez G, Aguilera-Manrique G, Márquez-Hernández VV. The connection of the clinical learning environment and supervision of nursing students with student satisfaction and future intention to work in clinical placement hospitals. J Clin Nurs. 2021;30(7–8):986–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lee T, Damiran D, Konlan KD, Ji Y, Yoon YS, Ji H. Factors related to readiness for practice among undergraduate nursing students: A systematic review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2023;69:103614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Labrague LJ, Arteche DL, Rosales RA, Santos MCL, Calimbas NDL, Yboa BC, Sabio JB, Quiña CR, Quiaño LQ, Apacible MAD. Development and psychometric testing of the clinical adjustment scale for student nurses (CAS-SN): A scale for assessing student nurses’ adaptation in clinical settings. Nurse Educ Today. 2024;142:106350. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Alkubati SA, Albagawi B, Alharbi TA, Alharbi HF, Alrasheeday AM, Llego J, Dando LL, Al-Sadi AK. Nursing internship students’ knowledge regarding the care and management of people with diabetes: A multicenter cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2023;129:105902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhang J, Shields L, Ma B, Yin Y, Wang J, Zhang R, Hui X. The clinical learning environment, supervision and future intention to work as a nurse in nursing students: a cross-sectional and descriptive study. BMC Med Educ. 2022;22(1):548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Visiers-Jiménez L, Suikkala A, Salminen L, Leino-Kilpi H, Löyttyniemi E, Henriques MA, Jiménez-Herrera M, Nemcová J, Pedrotti D, Rua M, et al. Clinical learning environment and graduating nursing students’ competence: A multi-country cross-sectional study. Nurs Health Sci. 2021;23(2):398–410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jagoda T, Rathnayake S. Perceived stress and learning environment among nursing students: A cross-sectional study. Collegian. 2021;28(5):587–94. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mazalová L, Gurková E, Štureková L. Nursing students’ perceived stress and clinical learning experience. Nurse Educ Pract. 2022;64:103457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Alkubati SA, Alsaqri SH, Alrubaiee GG, Almoliky MA, Al-Qalah T, Pasay-an E, Almeaibed H, Elsayed SM. The influence of anxiety and depression on critical care nurses’ performance: A multicenter correlational study. Australian Crit Care. 2025;38(1):101064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bhurtun HD, Azimirad M, Saaranen T, Turunen H. Stress and coping among nursing students during clinical training: an integrative review. J Nurs Educ. 2019;58(5):266–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ashktorab T, Hasanvand S, Seyedfatemi N, Salmani N, Hosseini SV. Factors affecting the belongingness sense of undergraduate nursing students towards clinical setting: A qualitative study. J Caring Sci. 2017;6(3):221–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Singer DL, Sapp A, Baker KA. Belongingness in undergraduate/pre-licensure nursing students in the clinical learning environment: A scoping review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2022;64:103422. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pourteimour S, Jamshidi H, Parizad N. Clinical belongingness and its relationship with clinical Self-Efficacy among nursing students: A descriptive correlational study. Nurs Midwifery Stud. 2021;10(1):47–51. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Alanazi MR, Aldhafeeri NA, Salem SS, Jabari TM, Al Mengah RK. Clinical environmental stressors and coping behaviors among undergraduate nursing students in Saudi Arabia: A cross-sectional study. Int J Nurs Sci. 2023;10(1):97–103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chaabane S, Chaabna K, Bhagat S, Abraham A, Doraiswamy S, Mamtani R, Cheema S. Perceived stress, stressors, and coping strategies among nursing students in the middle East and North Africa: an overview of systematic reviews. Syst Reviews. 2021;10(1):136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Squire D, Gonzalez L, Shayan C. Enhancing sense of belonging in nursing student clinical placements to advance learning and identity development. J Prof Nurs. 2024;51:109–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Grobecker PA. A sense of belonging and perceived stress among baccalaureate nursing students in clinical placements. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;36:178–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tudge JR, Mokrova I, Hatfield BE, Karnik RB. Uses and misuses of Bronfenbrenner’s bioecological theory of human development. J Family Theory Rev. 2009;1(4):198–210. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kort-Butler LA. Social support theory. In: The Encyclopedia of Juvenile Delinquency and Justice. edn.: 1–4.

- 23.Stanisławski K. The coping circumplex model: an integrative model of the structure of coping with stress. Front Psychol. 2019;10:694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Levett-Jones T, Lathlean J, Higgins I, McMillan M. Development and psychometric testing of the belongingness Scale-Clinical placement experience: an international comparative study. Collegian. 2009;16(3):153–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Levett-Jones T. Belongingness: a pivotal precursor to optimising the learning of nursing students in the clinical environment. In: 2007;2007.

- 26.Cohen S, Kamarck T, Mermelstein R. A global measure of perceived stress. J Health Soc Behav. 1983;24(4):385–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ali S, Tauqir S, Farooqi FA, Al-Jandan B, Al-Janobi H, Alshehry S, Abdelhady AI, Farooq I. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on students, assistants, and faculty of a dental institute of Saudi Arabia. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2021;18(24). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Saarikoski M, Leino-Kilpi H. The clinical learning environment and supervision by staff nurses: developing the instrument. Int J Nurs Stud. 2002;39(3):259–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Saarikoski M, Leino-Kilpi H, Warne T. Clinical learning environment and supervision: testing a research instrument in an international comparative study. Nurse Educ Today. 2002;22(4):340–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Joseph JG, Adamu M, K AB, Dele-Alonge J. Clinical learning environment and supervision: experience and satisfaction level of final year basic students, Kaduna state college of nursing and midwifery, Kafanchan. Nurs Scope. 2023;6(1):12–24. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eysenbach G. Improving the quality of web surveys: the checklist for reporting results of internet E-Surveys (CHERRIES). J Med Internet Res. 2004;6(3):e34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kline RB. Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford; 2023.

- 33.Bentler PM, Chou C-P. Practical issues in structural modeling. Sociol Methods Res. 1987;16(1):78–117. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cengiz Z, Gurdap Z, Isik K. Challenges experienced by nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Perspect Psychiatr Care. 2022;58(1):47–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ab Latif R, Mat Nor MZ. Stressors and coping strategies during clinical practice among diploma nursing students. Malays J Med Sci. 2019;26(2):88–98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Levett-Jones T, Lathlean J. The ascent to competence conceptual framework: an outcome of a study of belongingness. J Clin Nurs. 2009;18(20):2870–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manokore V, Rosalia GI, Ali F, Letersky S, Piadu IO, Palmer-Virgo L. Crossing the ascent to competence borders into privileged belongingness space: practical nursing students’ experiences in clinical practice. Can J Nurs Res. 2019;51(2):94–104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Moeller RW, Seehuus M, Peisch V. Emotional intelligence, belongingness, and mental health in college students. Front Psychol. 2020;11:93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kachaturoff M, Caboral-Stevens M, Gee M, Lan VM. Effects of peer-mentoring on stress and anxiety levels of undergraduate nursing students: an integrative review. J Prof Nurs. 2020;36(4):223–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Carless-Kane S, Nowell L. Nursing students learning transfer from classroom to clinical practice: an integrative review. Nurse Educ Pract. 2023;71:103731. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Patel SE, Chrisman M, Russell CL, Lasiter S, Bennett K, Pahls M. Cross-sectional study of the relationship between experiences of incivility from staff nurses and undergraduate nursing students’ sense of belonging to the nursing profession. Nurse Educ Pract. 2022;62:103320. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Baixinho CL, Ferreira ÓR, Medeiros M, Oliveira ESF. Sense of belonging and evidence learning: A focus group study. Sustainability. 2022;14(10):5793. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data are available at request from the corresponding author.