Abstract

Background

As dementia is a life-limiting illness, it is now widely accepted that people with dementia benefit from palliative care. The core components of palliative care for people with dementia have been suggested, however little is known about what an effective dementia palliative care service looks like in practice. While some services exist, a lack of description and scant detail on how and why they work makes it difficult for others to learn from existing successful models and impedes replication. Accordingly, we set out to describe an effective dementia palliative care service using programme theory, and to visually represent it in a logic model.

Methods

This was mixed-methods study. An exemplary dementia palliative care service, which cares for people with advanced dementia in their own home in the last year of life, had been identified from a previous survey. The development of the programme logic model was informed by interviews with staff (n = 6), staff surveys (n = 1), service user surveys (n = 10) and the analysis of secondary data sources including routinely collected service data.

Results

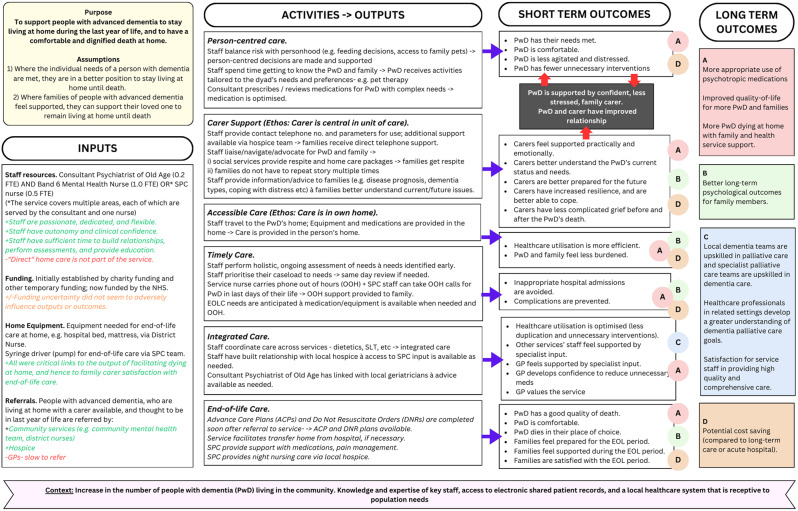

The logic model and summary results explain in detail how this dementia palliative care service undertook activities relating to person-centred care, carer support, end-of-life care, accessible care, timely care, and integrated care. It maps each activity to specific outputs and outcomes, showing that dementia palliative care, when provided appropriately, can greatly improve the quality of care received by people living and dying with advanced dementia, and their families, in the community.

Conclusions

The logic model presented may support those developing dementia palliative care services, or guide others running existing services in how to systematically present their service activities to others, and demonstrates how clinicians, policy-makers, and others involved in service planning can utilise logic models to design new services and improve existing services.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12904-025-01701-w.

Keywords: Dementia, Palliative care, End-of-life, Service evaluation, Logic model, Programme theory

Background

Dementia is a syndrome with an ever-growing population. In 2010, about 35.6 million people globally were living with dementia [1]; in 2023, this figure increased to 55 million, and there are now nearly 10 million new cases every year [2]. In the advanced stage of dementia people become fully dependent on carers [1].

It is now well accepted that dementia is a life-limiting condition, and people living with dementia can greatly benefit from palliative care at any stage of their illness [3]. However, only a minority of countries in Europe have sufficient palliative care services available to their citizens with dementia [4]. Across Europe and much of the world, home care of a PwD until death is a rare event, with the most common place of death being a care home (65.4%), followed by a hospital (22.9%) [5–7]. There may be various reasons for the relatively low percentage of home deaths, including that dying at home is not facilitated by statutory (i.e. government funded) services [7].

It is recognised that healthcare practitioners should adopt a general palliative care approach when supporting people with dementia [8], but some people will need the support of dedicated dementia palliative care (DPC) services. Although the theorised components of effective palliative care interventions have been elucidated in the literature [8, 9], no one ‘model’ or framework for a DPC service exists. There are limited examples of exemplary services [10]; however, a lack of descriptions of what they look like and how and why they work means that it is difficult for others to learn from existing successful services, impeding the ability to replicate them or develop new services in other locations.

Healthcare services, including palliative care services, are often complex, comprising many different components. One way of understanding services is to develop a programme theory which is a useful way to develop a causal model, linking programme inputs and activities to a chain of intended or observed outcomes [11]. A logic model, presented as a flow diagram, provides a summary of this information. The logic model describes how a programme, such as the provision of palliative care to a person with dementia (PwD), theoretically works to achieve benefits for participants, and captures the logical flow and linkages that exist between programme elements. Even in cases where the theory of a programme has never been made explicit, the logic model approach can help to uncover, articulate, present and examine a programme’s theory [12]. Explicitly stating causal assumptions about how an intervention will work can allow external scrutiny of its plausibility and help evaluators decide which aspects of the intervention to prioritise for investigation [13]. Analysis can also include mechanisms of change, for example, exploring how and why the delivered activities produce the desired outputs and outcomes [13]. This is important information to have when the intent is to learn from existing healthcare services, to expand them or replicate them in new sites.

The basic logic model includes the following four components [12]: Inputs: the human, financial, organisational, and community resources that need to be invested in a programme; Activities: what the programme does with the inputs, including the processes, events, and actions that are an intentional part of the programme implementation; Outputs: the direct products of programme activities, commonly measured in terms of the volume of work accomplished and the number of people reached; and Outcomes: the benefits or changes in the programme’s target population (or in the health service or its staff), measured at two timeframes of immediate and long-term outcomes.

In relation to palliative care, very few logic models have been published. Those that have been reported refer to general palliative care [14], children’s palliative care services [15] and for people with an intellectual disability who require palliative care [16]. There is, to date, no logic model that examines the causal relationships between inputs and outcomes within DPC services.

This paper presents our experience in using logic modelling to inform service development. As part of a wider research programme on palliative care for people with dementia (The Model for Dementia Palliative Care Project), we visited and evaluated four DPC services. Published elsewhere [10], we described each using programme theory and represented them using logic models. We then compared the services using the RE-AIM framework [17] to identify common elements of a successful programme. In the current paper, we focus on one service example, with the aim to describe an effective DPC service using programme theory, and to visually represent it in a logic model. We asked the following research questions:

What was the purpose of the DPC programme and on what assumptions was it based?

What resources facilitated implementation of the programme?

What activities were offered during the programme?

What were the programme’s outputs?

What were the outcomes of the programme in relation to each activity?

Methods

Design

This was a mixed-methods study using cross-sectional surveys, qualitative interviews, and examination of the service’s routinely collected activity data.

Setting and participants

A long list of DPC services was identified in The Republic of Ireland, Northern Ireland, England, Scotland, and Wales, through a survey with key stakeholders. Four exemplar services were chosen for evaluation, based on criteria including: in operation at least 6 months; provides identifiable activities; availability of routinely collected service data; not exclusively for people with dementia in final hours or days of life (full detail available elsewhere [9, 18]). This study focusses on one of these exemplar services, selected as it was the only service focused exclusively on home care (addressing our national strategy), and because there was data from service providers, users, and secondary sources, so that we could fully describe the service.

Data collection

The development of the programme logic model for the specialist DPC service consisted of several stages, namely interviews with staff, surveys completed by staff and service users, and the analysis of secondary data sources i.e. routinely collected service data and cost data. The surveys and interview schedules can be seen in supplemental file 1.

Data were collected between June and September 2020. Using purposive sampling, interviews were conducted with key service staff, guided by a semi-structured topic guide. Participants received an information sheet and provided written consent, prior to taking part in interview. Owing to Covid-19 restrictions at the time of data collection, interviews were conducted via a videoconference software platform. Interviews were audio-recorded with permission and lasted 59 min on average (range 44–88 min).

Online staff surveys were distributed to any staff wishing to take part, but who were unavailable for interview. Paper surveys for service users (current or bereaved family members of person with dementia) were distributed via service staff, with a pre-paid, pre-addressed envelope for direct return to the researchers. The front page of the survey had a clear statement, that returning a completing survey indicated consent to take part. As per the ethics process the survey was disseminated via the service staff who contacted families about their involvement. However, to ensure anonymity, we ensured families returned completed surveys directly to the research team and were aware their answers would not be shared with their healthcare team or impact on their care in any way.

Finally, anonymised routinely collected service data was requested, including demographics of service users, number of referrals per year, and place of death. A summary of all the data collected across these different methods and sources is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of data collected across all sources

| Primary data sources | N |

|---|---|

| Staff interviews | 6 |

| Consultant | 2 |

| Nurse | 3 |

| Administrator | 1 |

| Staff surveys (nurse) | 1 |

| Service user surveys | 10 |

| Daughter or son of person with dementia | 9 |

| Spouse of person with dementia | 1 |

| Secondary data sources | 2 |

| Routinely collected service data | 1 |

| Cost data | 1 |

Data analysis

The interviews were transcribed verbatim, imported to NVivo software, and analysed using “theoretical” Thematic Analysis [19] whereby our analysis was informed by previous research into the components of palliative care for community-dwelling people with dementia [9, 18]. Two researchers coded the data. Survey data was analysed, and descriptive statistics were produced for quantitative data, and with simple content analysis for qualitative data. Routinely collected data provided by the service was presented as aggregated numerical data. We applied the four components of a logic model (i.e. inputs, activities, outputs, outcomes) when coding the data, synthesising data from across sources into these categories.

Ethics

On review of the proposed study, no ethical concerns were identified. Approval was granted by the Social Research Ethics Committee, University College Cork (reference 755) and the Leeds East Research Ethics Committee (reference 20/YH/0027).

Results

In-depth interviews were conducted with key service staff: consultants (n = 2), nurses (n = 3) and an administrator (n = 1). This sample includes all current staff (n = 4) and former staff (n = 2). The service supports people with dementia to remain at home during the last year of life, and to die at home. It is led by a Consultant Psychiatrist of Old Age, with either (A) a Mental Health Nurse supporting families 9am-5pm, Monday-Friday and providing phone support outside of these hours, or (B) a Specialist Palliative Care (SPC) nurse supporting families 9am-5pm with phone support via hospice outside of these hours. The consultant serves all geographical areas covered by the service, and the two nurses each serve a different geographical area. The routinely collected data shared by the service is presented in Table 2. Study findings are displayed as a logic model (Fig. 1) and described in the subsequent sections.

Table 2.

Routinely collected demographic details provided by the service (2019 data)

| Routinely Collected Demographic details | N |

|---|---|

| At the time of site visit, what was the number of: | |

| Staff employed by the service | 3 (0.2 FTE Consultant Psychiatrist; 1.0 FTE Band 6 Mental Health Nurse-covering two geographic areas; 0.5 FTE Specialist Palliative Care Nurse, covering a third geographic area) |

| Service volunteers | 0 |

| In the previous year, what was the number of: | |

| Referrals of people with dementia | 23 |

| Referrals of all service users | 23 |

|

Referrals of people with dementia as a) a primary diagnosis b) a secondary diagnosis |

23 0 |

| All service users admitted to the service as a whole | 54 (includes all patients in the community) |

| Service users supported to die at home | 50 |

| Service users admitted to hospice | 0 (however hospice services were involved in approximately 50% of cases with support in the last days of life in the community) |

| Service users who were discharged and readmitted to the service | 0 |

Fig. 1.

A logic model to visually describe the inputs, activities and outputs, short- and long-term outcomes, and context of the dementia palliative care service, as well as the relationships between these elements

Context

The advanced dementia service was located in a country with established dementia and SPC services. It had the stated purpose to support people with advanced dementia to stay living at home during the last year of life, and to have a comfortable and dignified death at home. Service staff hypothesized that a combination of specific programme activities influenced patients’ ability to avoid admission to hospital or hospice and to remain at home. Of note, there was no formal protocol for the programme, which grew organically with staff working quite autonomously. Analysis of the multiple data sources uncovered two key assumptions underlying service activities:

1) When the individual needs of a PwD are met, they can be supported to stay living at home until death.

2) When families of people with advanced dementia feel supported, they can support their relative to remain living at home until death.

Inputs

The service was established through charitable seed funding in the early 2000s and received dedicated National Health Service (NHS) funding ten years later. The service consists of three key staff; a consultant psychiatrist (0.2 full-time equivalent (FTE)) and Band 6 (i.e. senior) mental health nurse (1.0 FTE). Recently the service has been extended to a neighbouring area, with an additional SPC nurse (palliative care clinical nurse specialist, 0.5 FTE). The SPC nurse works another 0.5FTE in a hospice (not specific to dementia care) thus she can offer her patients some additional support from the hospice (e.g. providing the hospice out of hours phone number).

Additional to the input of staffing, were the characteristics of passionate and dedicated staff. This was evident from their interviews, and service users’ testimonials.

They exceeded the help that we could even imagine that we would want. They absolutely changed a horrible time for the greater good, massively. (Family member)

Staff noted the necessary traits for being effective in the service. Staff were vocal and proactive in advocating for patients, for example around transferring the PwD home from hospital, where the nurse would proactively liaise with the hospital to enable the transfer rather than the typical hospital-directed discharge plan.

With this role you have to make sure you’re on the ball. So, when someone goes into hospital I can’t just sit back on my laurels and you know wait for them come [home], I have to be going in and saying “look, what’s happening? we want the person back home” … I’ll go then and try and make it happen as quick as possible, in a safe and holistic way. (ID: Staff 2)

Provision of essential equipment in patients’ homes was identified as an input necessary to support programme activities. This includes hospital-type beds and pressure-relieving mattresses, and syringe drivers, to afford the client a comfortable death at home. Such equipment is available via district nursing (similar to public health or community nursing in other countries) or occupational health services.

Receiving appropriate referrals was another key input. Staff spoke of their efforts to promote the service, and to challenge misconceptions of it being an end-of-life service only (i.e. last few hours or days of life). Early in the course of the service, the primary referral source was case finding through the routine work of the community mental health team. Subsequently, referrals also come from community services (specialist nurses, speech and language therapists, dietitians, physiotherapists, district nurses), General Practitioners (GPs), or the hospice. Referral criteria were kept purposively broad.

“When we started we had a referral form and some referral criteria but we’ve not really used it. We [the nurse and I] just have a conversation with a referral and we can tell [whether the referral is appropriate] because it’s … do they have dementia, are they bed bound … that’s basically it.” (ID: staff 5).

The full-time nurse maintains an active caseload of up to 45 patients, who are rarely discharged from the service.

Activities and outputs

Person-centred care

The service staff practice person-centred care through varied activities. Day-to-day activities are run by a key nurse. Upon referral, patients and families receive a detailed initial assessment, and the key nurse familiarises themself with each family, building a trusting relationship with them over time. The team delivers a care plan that is individualised to each patient and family. One participant explained, “there’s no guidebook”, and every individual is different and thus unique care plans are needed. The agreed plan between the key nurse and family outlines the PwD’s assessed needs and support plan.

Person-centred care is further facilitated by a service ethos of balancing risk with personhood; one example given was allowing a patient to have their favourite chocolate when they were otherwise following a pureed, speech and language therapist-instructed, diet. Another example concerned a bedbound man with advanced dementia whose family was encouraged to allow his beloved pets onto his bed.

He loved the animals, well at one point, [his daughter] would say “well they can’t go on the bed” and I said “why can’t they go on the bed?” So he had the cats and the dogs on the bed with him all day long, and…you could see him actually putting his hand out to them and just putting his hand on them, and he used to love that sort of, that contact, the touch or tactile feeling and everything (ID: Staff 3).

Carer support

Service activities recognise the family carer as central in the care unit. Staff participants discussed supports, such as respite via social services, or home care packages for those with high-level needs. The key nurse also supported carers in practical matters, such as applications for financial grants, with outputs including the carer reducing their working hours, or converting a room to care for their relative.

Carer education was another activity highlighted. The key nurse provides tailored information and advice to families on issues such as disease prognosis, dementia types, and dealing with distress. Families thus feel more supported and prepared for the end-of-life period.

You’re educating the family … so for example we know that swallow’s gonna deteriorate, we know that eating and drinking is gonna stop, we know sleep is gonna increase. So … what I do is, I speak to the families first, we talk about it you know, and they understand. So when these things happens, for example they go “oh we know, yeah, we spoke about this, we know-“. So you’re helping them understand what’s happening, making it less painful, and less daunting for them. (ID: Staff 2)

Staff participants spoke of carers as care-partners; rather than giving instructions, they sit down with the family and plan together.

Accessible care

All care for the PwD is provided in their home. The key nurses offer phone and video calls, as well as in-person care. The patient and family meet with the key nurse in-person for an initial assessment, and she/he provides them with a direct phone number, outlines a clear plan for ongoing communication, and ensures that the family know that they can contact her/him directly when needed.

I just jump in as “this is who I am, as things deteriorate, or as you have any worries or concerns, you’ve got my number…you give me a call or I’ll call you weekly, we’ll see how things are going” and it can be something as simple as that (ID: Staff 2).

The key nurses often gave their phone number to families for support outside of the official service hours.

If I had a difficulty or just needed reassurance, she was at the end of the phone. That meant the difference of solving a problem rather than spending the night worrying about it (Family member).

Timely care

The team carry out ongoing assessments, aiming to identify issues before they arise. The key nurses are very responsive to families, reporting that they will usually call to see them on the same day as being contacted. They can also arrange for district nurses to visit during the night and can take out-of-hours calls for those in the final days of life. The part-time SPC key nurse enabled formal 24/7 phone support via the hospice. Staff noted that families didn’t call out of hours often, theorising that simply possessing the contact details was enough to “get them through a bad night”.

The clinical nurse specialist is always on call through the night and [families] didn’t actually call that often because…there was a huge relief when we were able to give the numbers and say that we … we are a 24-hour advisory service, and we are there overnight if you need to ring. I think after five o’clock these relatives are kind of feeling, you know, very much on their own, so that was a huge support to a lot of relatives and carers. (ID: Staff 6)

Integrated care

An important activity provided by the key nurses, identified by staff and service users, was to coordinate the care provided by all related healthcare services.

I have generated a package, complete all the paperwork, as far as even doing things like DSTs (decision support tools) and checklists, I do all that if I need to … So for example, if I need someone to have a bit of respite and the reason I need them to have respite is because, prime example, the family are not coping, it’s too emotional, its impacting their sort of social life. I’ll go straight to social services, I’ll give them good clinical reasoning, and they accept that, … you know I’ve never had any hurdles (ID: Staff 2).

Good communication between healthcare team members enables optimal palliative care practices. Some service staff engage in formal teaching to district nurses and GPs. The lead consultant works closely with colleagues from different disciplines; for example, seeking advice from geriatricians on a patient’s comorbid conditions. The consultant can prescribe medications, and review complex medication regimes, beyond a GP’s usual scope; for example, stopping prescription medications such as warfarin or statins that are no longer appropriate at end-of-life. Consultants will also cancel unnecessary outpatient or community appointments (e.g., a long-standing recurring dermatology appointment). The output of this is reduced patient burden.

Families also appreciated not having to repeat their story to multiple healthcare professionals. Often team members will do joint visits when external services are referred, enabling the service team member(s) to explain the patient’s history to the other professional, and also to help the family interpret the advice from the external service.

So yeah, so this kind of in-depth knowledge you get for your family … so a lot of misunderstandings and tensions between professionals and families we can iron out, because we explain both sides so that they understand. (ID: Staff 5)

End-of-life care

Where not already in place, advanced care plans and ‘do not resuscitate’ orders are completed soon after referral to the service. The key nurse prepares families for what to expect at end-of-life. They ensure any prescription medications needed towards the end-of-life are available and stored securely in the house, to avoid delays when eventually needed. The team is supported by the hospice team for night nursing (where a SPC nurse provides overnight direct care in the final days of life), end-of-life medications, pain management. The output of this is that necessary provisions are in place by time of end-of-life. According to interviewed participants, this was a very responsive aspect of the service. This benefits patients, as one participant noted that when the SPC nurse gets involved and the pain settles, other symptoms, such as agitation, might settle too.

She got quite agitated…and in the end there was a lot of grimacing, a lot of frowning, so we felt it was likely to be pain related so we started a little pain patch which kind of, changed her life overnight really for that little period of time, because she was just so relaxed and settled. (ID: Staff 4)

In addition, transfer home from hospital to facilitate dying at home is arranged by the team, if necessary. After a patient’s death, the team carries out bereavement calls for families three months after the death, although families are encouraged to make contact sooner if they need to. Routinely collected data showed that most patients in the service die at home (93% in the previous year).

Outcomes

Outcomes can be described in terms of effect on the PwD, carer, and healthcare professionals / system. The logic model depicts the flow from service activities and outputs to outcomes (Fig. 1).

The combined service activities and outputs led to long-term positive effects on the PwD and families. Service users highly rated the quality of care. All service users who completed the survey (n = 10) were very satisfied (80%) or satisfied (20%) with the service; 100% responded “yes” that the service benefitted their loved one with dementia and their family.

PwD

The person-centred, timely care, delivered in the PwD’s home, was seen to result in less agitation and distress for the PwD, fewer unnecessary interventions or medications, and in the PwD’s wishes being respected. Excellent carer support meant in turn that the PwD is supported by a confident family carer. The participants all observed that PwD do better when cared for in their home by people they know.

Often what happens is when a patient comes out of hospital, they do present as very unwell, but many times, after a bit of tweaking, they actually do settle because they’re back in their own environment (ID: Staff 2).

Staff and service users noted the PwD has a good quality of death and has symptoms managed, for example pain and agitation. While prospectively measuring long-term outcomes was outside the study remit, the staff, some of whom were part of the service preceding its formal inception 17 years previously, provided valuable insight. They noted that more PwD are being supported to die at home each year; staff who had worked in the area prior to the service was commencement noted that previously it was rare that anyone with advanced dementia lived at home, and very few died at home.

Carers

Outputs noted by staff and families were that carers feel supported, better able to cope, and have increased resilience. One staff member observed better relationships between carers and the PwD, postulating that the carer is more likely to experience the (increasingly rare) occasions where the PwD is more engaged and well in advanced dementia, when they are caring for them at home.

It was also reported that, sometimes, simply meeting the different teams, even when they can’t do much for the person, helps the family feel more supported, knowing that “everything … is being done”. Service users were more relaxed and confident having the phone number of their key nurse; this was hugely valued by families.

If I had a difficulty or just needed reassurance, she was at the end of the phone. That meant the difference of solving a problem rather than spending the night worrying about it (Family member).

For some people, simply getting a phone call from their key nurse weekly was reported as greatly relieving anxiety, as they feel supported and knew that they had access to help when needed. This was perceived to avoid inappropriate hospital admissions during evenings or weekends; this was supported by the administrative data which showed that very few patients in the service died in hospital.

Healthcare professionals / systems

The key nurses managed their own caseloads, and decided when to discharge anyone doing “well”. They can thus provide a continuous level of care appropriate to the needs of each family, inclusive of those with high and low needs.

If I thought someone needed me for 2–3 h, I would go there for 2–3 h, if I thought they needed me for 10 min or half an hour, or a phone call, that’s what I’ll do. (ID: Staff 3)

Staff noted improved healthcare utilisation as an outcome of all necessary services being accessible to the PwD and family via the DPC service. Simultaneously, the service took pressure off other healthcare services, for example, instead of district nurses needing to physically visit a patient, the key nurse can carry out some activities under their phone guidance.

Another notable outcome was that local dementia teams are informally upskilled in palliative care and SPC teams are upskilled in dementia, through integrated working. Staff postulated that, compared to care preceding the service, there has been progressively reduced use of antipsychotic and antidepressant medications because of personalised care and met needs.

Another outcome observed for staff was high job satisfaction from providing such high quality and comprehensive care, creating a feedback loop and a longer-term outcome of fulfilled staff providing a better service.

To me it’s a very rewarding post, I loved it to bits…it’s also very humbling for [PwD and families] to let you into their…homes. (ID: Staff 3)

Finally, the service had data to support the service being much cheaper compared to long-term care or acute hospital services. However, as cost effectiveness, i.e. comparing the additional costs to additional benefits, has not be examined and is complex to measure in services of this nature, staff advised building a case for a similar service around quality of care and not just cost savings.

Mechanism of action wherein activities led to improved outcomes

There appeared to be several key mediators of the programme success. The first was the “timely care”, delivered in the person’s home, and focussed on the carer as much as the PwD, which resulted in increased carer resilience.

I think carers develop a lot more resilience if they think there is sensible advice and help on the same day, if they think they are going to have to get referred and wait for six weeks they can’t possibly carry on, so it’s about that ability to respond which I think produces a lot of resilience among carers. And with that they’ll carry a lot more burdens than otherwise. (ID: Staff 1)

This was intrinsically linked to relationship building, 24/7 support and carer education, and greatly contributed to more deaths at home and reduced unnecessary hospitalisations. The emotional support and person-centred approach of the key nurses was a mediator of carer resilience. These activities and outputs together led to more positive outcomes for the PwD, such as reduced distress, and wishes to remain at home (where relevant) being fulfilled.

Another key mediator was the presence of highly experienced and dedicated staff, who were passionate about their role. Combined with a focus on integrating with and streamlining existing services, the programme ran successfully on relatively limited staff resources, with high job satisfaction. Staff made determined connections with related healthcare services in the area, promoted the service, and tackled misconceptions. They showcased the service benefit, including how they could reduce work for other teams by avoiding duplication.

Like any project, it’s breaking down those silos you know “ah well this is how we’ve always done it” you know, you know “do we really need you, we’ve been doing this for years” kinda thing. (ID: Staff 4)

This integration of care was a mediator in facilitating death at home, where the SPC team and night nursed played a key role.

Staff autonomy was another important mechanism, mentioned by numerous staff. This autonomy meant that staff could make decisions about who to prioritise for support, and how to provide this support to suit individual families, again ensuring more PwD overall can remain at home and increasing service user satisfaction.

Numerous staff identified GPs as a group who were slower to engage with the service, although newer GPs were seen to be more amenable, and service staff targeted local GPs during formal/informal education initiatives. Having a doctor and nurse in the service was considered helpful as it was suggested that external doctors are more willing to engage when approached by another doctor.

When you ask GPs if they need [a DPC service], they don’t think they need it, they think that they can do it, which is very interesting. Because they’re like oh yeah we can monitor people with advanced dementia, yeah and you know how long it takes? (ID: Staff 5)

Another notable factor was that there is a shared electronic patient health record across all community services in the area. However, one staff member pointed out that for this to be useful, the district nurses and others need to “actually read notes”. Thus, the influence of this on outcomes does not appear pivotal.

While the service performed well, a few staff and service user participants suggested that it could be improved by offering formal out-of-hours support. Equally, one staff member said that it manages fine as a 9 − 5 service as you can usually anticipate end-of-life, make referrals, and provide extra care packages before a weekend.

Finally, staff reported little ‘fear’ of palliative care from patients or families, this was an advanced dementia service and people are already dealing with that. Any fear or hesitation is dealt with, as staff have the time to explain what palliative care is and its goals, and answer any questions the family may have.

Discussion

Understanding an effective DPC service in terms of existing literature

It is widely advocated that PwD will benefit from palliative care [3], yet complete descriptions of DPC services are lacking from the literature. This paper presents a thorough description of an exemplary DPC service using the framework of programme theory. Creating the logic model allowed us to elucidate providers’ assumptions about why the programme worked. Participants described many different core service activities; these functioned on the assumptions that providing individualised care to PwD, and meaningfully supporting the carer, would allow a PwD to live well at home until death. Key activities and outputs could be grouped into the categories of providing person-centred care, carer support, end-of-life care, accessible care, timely care, and integrated care. The first three categories align with the European Association of Palliative Care white paper recommendations for optimal palliative care [8], and all six were identified in an expert survey to identify theorised core components of a DPC model [9].

Providing person-centred care was key to why this DPC service worked. While the positive impact of person-centred interventions for people living with various stages of dementia across settings is known [20], a scoping review found that empirical evidence specifically for the effectiveness of person-centred care approaches for community dwelling PwD at end-of-life is limited [18], although a small randomised control trial showed promising results [21]. Also, nurses in the Netherlands (n = 416 surveyed) providing palliative care to PwD at home or in nursing homes, said that if they had more time, the most important activity they would increase would be providing person-centred care, including meaningful activities, connecting to the patient, sensory stimulation, and complying with individual wishes [22]. In the service reported here, person-centred care notably improved quality-of-life and death, as evidenced by service staff and family accounts.

It is essential that carer support and a dyadic approach is central to any model which aims to support PwD to live at home [21]. Carers take on a more prominent role when the PwD is cared for at home rather than a nursing home, and carers greatly value this role [22]. This DPC service worked as families had their needs met, as well as being respected as members of the caregiving team.

A significant source of stress at end-of-life is carers feeling uninformed or unsupported in making care decisions for their loved one with advanced dementia [23]. Seamless care by a key nurse, who has a relationship with the family, provided positive experiences during and beyond end-of-life. The psychosocial support provided here appeared to be particularly important; others have reported the common and negative impact of conflict between carers of PwD and staff at end-of-life [24].

Care that is accessible, timely and integrated across healthcare services is crucial for a community DPC service. PwD living at home have better quality-of-life compared to their counterparts in residential care [25]. Coordination and continuity of care, and effective working with primary care, are essential for good end-of-life care for PwD [26]. Here, the key nurse was integral to activities in ensuring accessible, timely, and integrated care, resulting in a very positive experiences for service users.

A key input was the dedicated and hard-working key staff; in attempting to scale up such a programme, identification and support of suitable individual staff members is paramount. While the service evidently ran well with limited staff resources, there may be a risk of burnout as providing formal care for PwD living at home is emotionally intense [27], so it is important that services are resourced adequately, and appropriate staff supports are provided in medium and long-term. The latter requires investment and, to date, the cost effectiveness of the service remains unknown. As mentioned above, an in-house informal cost analysis suggested the service is much cheaper compared to long-term care or acute hospital services. However, a formal economic evaluation is needed, cognisant that measuring benefits to inform an economic evaluation and determine cost effectiveness is challenging and complex for such a service.

Value of the application of programme theory and the logic model

Simplistic depictions of causal relationships are weaknesses of logic models [28]. An intervention may have different effects in different contexts even if implemented exactly the same [13], thus it is important to consider context when developing a logic model. In the current example, key staff personalities, access to electronic shared patient records, and a receptive local healthcare system were contextual factors which may have contributed to the service outcomes, to varying degrees.

This paper reports on a subset of data from a wider project, where we evaluated four exemplar DPC services [10]. Employing logic models allowed us to individually describe each service as a model, which was important given the heterogeneity of the DPC services, before subsequently comparing them and identifying common elements [10]. There are some examples of logic models being applied to dementia interventions and services (see for example [28–30]). Logic models are a valuable tool that may be used by others looking to understand and share effective DPC, or other types of, services.

Limitations

While we made effort to collect data from multiple sources, the main source of in-depth data was interviews with staff. It is often not possible to collect qualitative data from people with advanced, end-stage dementia, or from their family carers who are in the midst of caring. The number of families using the service who responded to our survey was small. There may also have been selection or response biases since families were recruited through service staff.

Future research

The first step suggested by the Medical Research Council [13] is to describe an intervention to determine what ingredients are present, identifying which ones are presumed to bring about change. It would be interesting in future research to apply this logic model in a different setting, investigating the reasons behind any differences in outcomes of the model in different settings. It would also be helpful to collect data prospectively for further evidence relating to effectiveness of the currently described service and to relate this to any structural changes to the DPC service that may happen in the future. Also, to inform policy and future service developments, it would be important to have formal economic evaluations to determine a DPC service’s cost effectiveness and budget impact.

Conclusion

This paper presents a logic model which may support service planning to those developing DPC services, or guide those running existing services in how to systematically present their service activities to others. Clinicians, policy-makers, and others involved in developing DPC services can utilise logic models to design new services, and improve existing services. The logic model and summary results herein explain how effective DPC service activities led to outputs such as person-centred care, carer support, end-of-life care at home, accessible care, timely care, and integrated care. The model shows that DPC, when provided appropriately, can greatly improve the quality of care received by people living and dying with advanced dementia, and their families, in the community.

Electronic supplementary material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

The authors wish to thank all of the participants, notably the staff at the service who were generous with their time and assistance in collecting routine data, providing contacts for interviews, and distributing service users surveys.

Abbreviations

- DPC

Dementia Palliative Care

- FTE

Full-Time Equivalents

- GP

General Practitioner

- SPC

Specialist Palliative Care

- PwD

Person/People with Dementia

Author contributions

SF, JD, SG, WGK, AM, and ST were involved in the study design. SF and NOC were involved in carrying out the data collection and analysis. All authors were involved in preparing and/or reviewing the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported by a grant from the Health Research Board (ref: ILP-HSR-2017-020). The funder had no role in the conceptualization, design, data collection, analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

Data availability

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

This study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the Social Research Ethics Committee, University College Cork (reference 755) and the Leeds East Research Ethics Committee (reference 20/YH/0027). All participants provided informed consent.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Dementia: a public health priority. Geneva: WHO; 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Dementia. 2023. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/dementia

- 3.Timmons S, Fox S, Drennan J, Guerin S, Kernohan WG. Palliative care for older people with dementia—we need a paradigm shift in our approach. Age Ageing. 2022;51 3:afac066. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alzheimer Europe. European dementia monitor 2020: comparing and benchmarking National dementia strategies and policies. Luxembourg: Rue Dicks; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dasch B, Bausewein C, Feddersen B. Place of death in patients with dementia and the association with comorbidities: a retrospective population-based observational study in Germany. BMC Palliat Care. 2018;17:1–2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Houttekier D, Cohen J, Bilsen J, Addington-Hall J, Onwuteaka-Philipsen BD, Deliens L. (2010). Place of death of older persons with dementia. A study in five European countries. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 2010;58(4):751–756. 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.02771.x [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Mogan C, Lloyd-Williams M, Harrison Dening K, Dowrick C. The facilitators and challenges of dying at home with dementia: A narrative synthesis. Palliat Med. 2018;32(6):1042–54. 10.1177/0269216318760442. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Van der Steen JT, Radbruch L, Hertogh CM, de Boer ME, Hughes JC, Larkin P, et al. White paper defining optimal palliative care in older people with dementia: a Delphi study and recommendations from the European association for palliative care. Palliat Med. 2014;28 3:197–209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fox S, O’Connor N, Drennan J, Guerin S, Kernohan WG, Murphy A, Timmons S. Components of a community model of dementia palliative care. J Integr Care. 2020;28(4):349–64. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fox S, Guerin S, Kernohan WG, Drennan J, O’Connor N, Rukundo A, Timmons S. A comparison of four dementia palliative care services using the RE-AIM framework. BMC Geriatr. 2023;23:677. 10.1186/s12877-023-04343-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rogers P, Petrosino A, Hacsi T, Huebner T. Programme theory evaluation: practice, promise and problems. In: Rogers P, Petrosino A, Hacsi T, Huebner T, editors. Programme theory evaluation: challenges and opportunities, new directions in evaluation series. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2000. pp. 5–13. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Savaya R, Waysman M, The Logic Model. Adm Social Work. 2005;29(2):85–103. 10.1300/J147v29n02_06.

- 13.Moore GF, Audrey S, Barker M, Bond L, Bonell C, Hardeman W et al. Process evaluation of complex interventions: medical research Council guidance. BMJ;2015, h1258–1258. 10.1136/bmj.h1258 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 14.Uneno Y, Iwai M, Morikawa N, Tagami K, Matsumoto Y, Nozato J, Kessoku T, Shimoi T, Yoshida M, Miyoshi A, Sugiyama I. Development of a National health policy logic model to accelerate the integration of oncology and palliative care: a nationwide Delphi survey in Japan. Int J Clin Oncol. 2022;27(9):1529–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Maynard L, Lynn D. Development of a logic model to support a network approach in delivering 24/7 children’s palliative care: part one. Int J Palliat Nurs. 2016;22(4):176–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.McKibben L, Brazil K, McLaughlin D, Hudson P. Determining the informational needs of family caregivers of people with intellectual disability who require palliative care: A qualitative study. Palliat Support Care. 2021;19(4):405–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Glasgow RE, Vogt TM, Boles SM. Evaluating the public health impact of health promotion interventions: the RE-AIM framework. Am J Public Health. 1999;89:1322–7. 10.2105/AJPH.89.9.1322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.O’Connor N, Fox S, Kernohan WG, Drennan J, Guerin S, Murphy A, Timmons S. A scoping review of the evidence for community-based dementia palliative care services and their related service activities. BMC Palliat Care. 2022;21:132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. In: Qualitative Research in Psychology. vol. 3. 2006;77–101.

- 20.Kim SK, Park M. Effectiveness of person-centered care on people with dementia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Interv Aging. 2017;12:381–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Reisberg B, Shao Y, Golomb J, Monteiro I, Torossian C, Boksay I, et al. Comprehensive, individualized, person-centered management of community-residing persons with moderate-to severe alzheimer disease: a randomized controlled trial. Dement Geriatr Cogn Disord. 2017;43(1–2):100–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bolt SR, Meijers JMM, van der Steen JT, Schols JMGA, Zwakhalen SMG. Nursing staff needs in providing palliative care for persons with dementia at home or in nursing homes: A survey. J Nurs Scholarsh. 2020;52(2):164–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bolt S, van der Steen J, Schols J, Zwakhalen S, Meijers J. What do relatives value most in end-of-life care for people with dementia? Int J Palliat Nurs. 2019;25(9):432–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Davis R, Ziomkowski MK, Veltkamp A. Everyday decision making in individuals with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease: an integrative review of the literature. Res Gerontol Nurs. 2017;10(5):240–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Olsen C, Pedersen I, Bergland A, Ender-Slegers MJ, Joranson N, Calogiuri G, Ihlebaek C. Differences in quality of life in home-dwelling persons and nursing home residents with dementia - a cross-sectional study. BMC Geriatr. 2016;16:137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Bamford C, Lee R, McLellan E, Poole M, Harrison-Dening K, Hughes J, et al. What enables good end of life care for people with dementia? A multi-method qualitative study with key stakeholders. BMC Geriatr. 2018;18(1):1–15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Yeh IL, Samsi K, Vandrevala T, Manthorpe J. Constituents of effective support for homecare workers providing care to people with dementia at end of life. Int J Geriatr Psychiatry. 2019;34(2):352–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rogers PJ. Using programme theory to evaluate complicated and complex aspects of interventions. Evaluation. 2008;14:1. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lassell R, Fields B, Busselman S, Hempel T, Wood W. A logic model of a dementia-specific programme of equine-assisted activities. Human-Animal Interact Bull. 2021;9:2. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ho P, Cheong RCY, Ong SP, Fusek C, Wee SL, Yap PLK. Person-Centred care transformation in a nursing home for residents with dementia. Dement Geriatric Cogn Disorders Extra. 2021;11(1):1–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.