Abstract

Paired-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation is a valuable tool for investigating inhibitory mechanisms in motor cortex. We recently demonstrated its use in measuring cortical inhibition in visual cortex, using an approach in which participants trace the size of phosphenes elicited by stimulation to occipital cortex. Here, we investigate age-related differences in primary visual cortical inhibition and the relationship between primary visual cortical inhibition and local GABA+ in the same region, estimated using magnetic resonance spectroscopy. GABA+ was estimated in 28 young (18 to 28 years) and 47 older adults (65 to 84 years); a subset (19 young, 18 older) also completed a paired-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation session, which assessed visual cortical inhibition. The paired-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation measure of inhibition was significantly lower in older adults. Uncorrected GABA+ in primary visual cortex was also significantly lower in older adults, while measures of GABA+ that were corrected for the tissue composition of the magnetic resonance spectroscopy voxel were unchanged with age. Furthermore, paired-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation–measured inhibition and magnetic resonance spectroscopy–measured tissue-corrected GABA+ were significantly positively correlated. These findings are consistent with an age-related decline in cortical inhibition in visual cortex and suggest paired-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation effects in visual cortex are driven by GABAergic mechanisms, as has been demonstrated in motor cortex.

Keywords: aging, gamma-aminobutyric acid, magnetic resonance spectroscopy, transcranial magnetic stimulation

Introduction

Healthy aging, even in the absence of disease, is associated with reduced visual abilities, including impaired motion perception (Hutchinson et al. 2012; Billino and Pilz 2019), slowed visual processing speed (Kline and Birren 1975; Habekost et al. 2013), and spatial contrast deficits (Higgins et al. 1988; Elliott et al. 1990). While the optical quality of the eye deteriorates over the lifespan (Shinomori et al. 2022), these changes alone are unable to account for all visual performance declines (Ball and Sekuler 1986; Sekuler and Ball 1986; Spear 1993; Bennett et al. 1999; Calkins 2013). Changes in the physiological properties of neurons in the visual system appear to also lead to age-related impairments in visual abilities (Spear 1993; Andersen 2012), and observations from nonhuman primates suggest that impaired gammaaminobutyric acidergic (GABAergic) inhibition may play a role. In older macaques, neurons in the primary visual cortex fire less selectivity to specific orientations and motion directions, and show higher spontaneous firing rates than neurons in young adult monkeys (Schmolesky et al. 2000). When GABA or GABAA receptor agonists are administered to these neurons, they begin to respond more selectively, like the younger animals (Leventhal et al. 2003). Further, there is evidence suggesting that the proportion of GABAergic neurons is reduced in primary visual cortex in older cats compared to younger cats (Hua et al. 2006).

In humans, magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) allows for the noninvasive in vivo quantification of local GABA concentrations in regions of interest. Examination of GABA in frontal regions indicates an increase in GABA during adolescence, followed by a peak in early adulthood, before declining over middle and older age (Porges et al. 2021). In visual cortex, there is evidence for reduced GABA concentrations in older adults (Hermans et al. 2018; Maes et al. 2018; Simmonite et al. 2018; Chamberlain et al. 2021). MRS studies of visual cortex GABA reveal correlations with cognitive performance in domains such as fluid processing (Simmonite et al. 2018), working memory (Marsman et al. 2017), and cognitive failures (Sandberg et al. 2014), as well as visual performance including orientation-specific contrast suppression (Cook et al. 2016; Yoon et al. 2010), spatial suppression of motion (Pitchaimuthu et al. 2017), orientation discrimination (Edden et al. 2014; Mikkelsen et al. 2017), and binocular rivalry (van Loon et al. 2013; Robertson et al. 2016; Pitchaimuthu et al. 2017).

Transcranial magnetic stimulation (TMS) is a noninvasive neurostimulation technique that uses magnetic fields to induce an electrical current in a localized region of the brain, which can then depolarize neurons within this region, discharging action potentials. These action potentials propagate along the axon of the stimulated neurons, transmitting the electrical signal to other neurons. Depending on the brain region stimulated, the functional response to TMS can include the modulation of sensory perception, motor control, or cognitive processes.

Paired-pulse TMS (ppTMS) protocols allow for the in vivo assessment of cortical inhibition (Kujirai et al. 1993). In ppTMS paradigms, two magnetic pulses are delivered in quick succession to the same brain region, with the first conditioning stimulus modifying the response to the following test stimulus. The intensity of the conditioning pulse is typically set below the minimum intensity required to elicit a response, while the intensity of the test stimulus is set above this threshold. When there is a 1–6 ms interval between the conditioning and test pulse, the response to the test pulse is reduced in comparison with a test pulse of the same intensity presented alone. This elicited inhibition is known as short-interval intracortical inhibition (SICI; Kujirai et al. 1993).

Most studies of SICI have focused on the motor cortex. One reason is the ease with which the motor cortex can be accessed and stimulated, since it is located on the surface of the brain. In addition, TMS stimulation of motor cortex generates action potentials that propagate along the corticospinal tract to the spinal cord, where they activate alpha motor neurons that lead to muscle contractions that are easily recorded with skin electrodes as motor-evoked potentials (MEPs). Characteristics of MEPs such as amplitude and latency can be used to probe aspects of cortical inhibition and facilitation. Pharmacological studies have indicated that SICI in primary motor cortex is mediated by GABAA receptors, since positive allosteric modulators of GABAA increase the inhibitory effect (Di Lazzaro et al. 2005a; Ziemann et al. 1996). When investigating age-related changes in motor cortex SICI at rest, there have been mixed findings (age-related increases: Kossev et al. 2002; Smith et al. 2009; McGinley et al. 2010; age-related decreases: Peinemann et al. 2001; Marneweck et al. 2011; no differences: Oliviero et al. 2006; Rogasch et al. 2009; Cirillo et al. 2011) with meta-analysis indicating no significant changes over the course of healthy aging (Bhandari et al. 2016).

Our group has demonstrated that ppTMS can also be used to assess inhibition in primary visual cortex by measuring participant-traced phosphenes; short-lived visual disturbances that result from occipital stimulation (Khammash et al. 2019a, 2019b). In this paradigm, a decrease in the size of the conditioned phosphene compared with the unconditioned phosphene can be used to estimate cortical inhibition outside motor cortex. In the present study, we use this paradigm to explore age-related differences in cortical inhibition in left primary visual cortex in healthy older adults. To our knowledge, this is the first study to examine aging effects on ppTMS in visual cortex. While previous studies have been unable to provide robust evidence for age differences in cortical inhibition in motor cortex, age-related changes in the brain are not uniform (Trollor and Valenzuela 2001; Scahill et al. 2003), and it is unclear how cortical inhibition is affected in other regions of the brain. Based on reports of decreased GABAergic inhibition in primary visual cortex of older macaque monkeys (Schmolesky et al. 2000; Levanthal et al. 2003), we predict that older adults will demonstrate lower visual cortical inhibition compared with young adults. In addition, we also use MRS to estimate GABA concentrations in the same region of the brain that we stimulate using TMS—left primary visual cortex—and perform an exploratory analysis probing the relationship between GABA and visual cortical inhibition. While pharmacological studies have indicated that SICI in motor cortex is GABA mediated, previous investigations exploring the relationship between ppTMS-measured motor cortical inhibition and MRS estimates of motor cortex GABA concentrations have indicated a lack of association between these measures (Cuypers and Marsman 2021). Therefore, we did not have a strong a priori hypothesis regarding the results of this analysis.

Materials and methods

Participants

Participants were 29 young (15 men and 14 women, mean age: 22.79 ± 3.02 years, range: 18 to 28 years) and 49 older (21 men and 28 women; mean age: 70.45 ± 4.66 years, range: 65 to 84 years) adults who were recruited to take part in the Michigan Neural Distinctiveness (MiND) study (Gagnon et al. 2019). Prior to enrollment in the MiND study, participants were telephone-screened to identify contraindications for magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and TMS, such as metal implants, a personal or family history of seizures, or any use of central nervous system–active medications(Rossi et al. 2021). All participants taking part in the MiND study self-reported as right-handed; had normal or corrected to normal vision; and were free from self-reported histories of psychiatric or neurological disorders, head injuries with loss of consciousness for greater than 5 min, or drug or alcohol abuse. All study procedures and protocols were approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan, and all participants provided written informed consent following explanation of the study.

Participants took part in an MRS session and a TMS session on separate days. MRS sessions took place as part of the main arm of the MiND study, and following participants’ completion of these, they were contacted and asked if they wished to take part in an optional TMS session. The average time between MRS and TMS sessions was 116 days (SD = 198 days).

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy

All scanning was performed on a GE Discovery MR750 3 Tesla scanner at the University of Michigan Functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging Laboratory. A high-resolution T1-weighted spoiled 3D gradient-echo acquisition (SPGR) image was collected for MRS voxel placement and to allow the classification of tissue types within the MRS voxel.

GABA-edited MRS spectra were acquired from a 3 cm × 3 cm × 3 cm left primary visual voxel using a MEGA-PRESS sequence with the following parameters: TE = 68 ms (TE1 = 15 ms, TE2 = 53 ms); TR = 1,800 ms; 256 transients (128 ON interleaved with 128 OFF) of 4,096 datapoints; spectral width—5 kHz; and frequency-selective editing pulses (14 ms) applied at 1.9 ppm (ON) and 7.46 ppm (OFF). Total scan time was approximately 8.5 min. The voxel was placed entirely in the left hemisphere, and centered on the calcarine sulcus, according to a template image (provided in Fig. 1) and was positioned as close to the cortical surface as possible, to ensure overlap with the TMS-targeted region. Spectra from six other voxels were collected using the same parameters during the same scanning session but are not relevant to the current research question and are not presented in this manuscript (but see Cassady et al. 2019; Chamberlain et al. 2021; Lalwani et al. 2019).

Fig. 1.

Template for MRS voxel placement in left primary visual cortex.

Recommended minimum reporting details for the MRS data are included in Supplemental Table 1, as recommended by Lin et al. (2021).

TMS

A MagPro X 100 stimulator (MagVenture Inc., Atlanta, GA) with a figure-eight coil (MC-B70, MagVenture Inc., Atlanta, GA) was used to deliver posterior–anterior TMS over left occipital cortex. A frameless stereotactic neuronavigational system (BrainSight 2, Rogue-Research Inc, Montreal, Canada) was employed to mark scalp stimulation sites and ensure that stimulation location and trajectory remained constant throughout the session.

Participants were seated in a dark room and instructed to fix their gaze on the center of a 188 cm × 107 cm wall-projected screen, which was 120 cm away from them. Research staff explained to participants that they were going to receive stimulation over the occipital lobe and that it may elicit a brief, subtle visual disturbance called a phosphene. This phosphene could look like a flash or light, or a focal fuzzy spot. To discourage response bias, research staff emphasized that not all participants report seeing phosphenes. Participants were then briefed on our previously validated method of phosphene quantification (Khammash et al. 2019a, 2019b) in which a custom LabView program is displayed on the projected screen and participants use a mouse cursor to outline the shape of the perceived phosphene.

To determine the optimum stimulation location and intensity, BrainSight was used to generate a 3 cm × 3 cm grid comprised of 9 targets, the center located 3 cm anterior and 1.5 cm left-lateral of the inion. The coil was pressed tangentially against the scalp, with the handle angled 90° to the midline (see Fig. 2a, for visualization of the stimulation grid and coil orientation). Starting at 60% of the maximum stimulator intensity, each grid target was stimulated three times. After each stimulation, the participant was asked to report whether they perceived a phosphene. Stimulation intensity was increased by 10% increments and all targets tested again, until stimulation at one or more locations elicited a phosphene. If more than one location evoked phosphenes, the target that generated the most consistent, largest phosphenes was selected as the “hotspot.” Once a hotspot had been identified, the participants’ phosphene threshold (PT) was obtained by increasing or decreasing the stimulation intensity by 2%, then 1% increments to find the lowest intensity stimulation that elicited phosphenes on 5 out of 10 trials. Each participant’s phosphene threshold was expressed as a percentage of the maximum intensity of stimulator output.

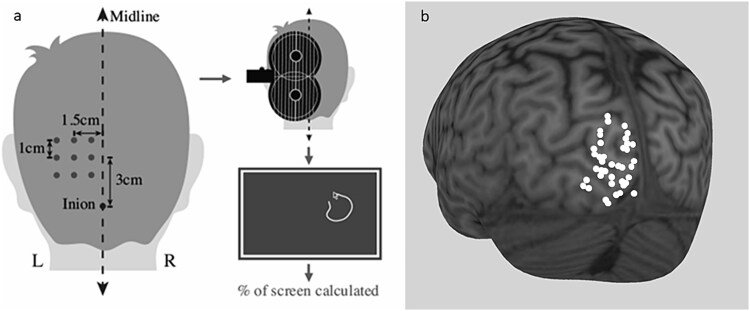

Fig. 2.

a) Schematic demonstrating phosphene data collection method. BrainSight was used to generate a 3 × 3 grid of stimulation targets over the visual cortex, with the center of the grid 3 cm dorsal and 1.5 cm left-lateral of the inion. The TMS coil was held at 90° to the midline. Starting with a stimulator input of 60% of maximum stimulator output, each target was stimulated three times (monophasic, lateral-medial induced current, MagPro X100 with MagOption stimulator and MC-B70 butterfly coil). If stimulation at 60% of maximum output failed to induce phosphenes at any of the 9 targets, intensity was increased in increments of 10% until the participants reported seeing phosphenes. If phosphenes were elicited by stimulation to more than one target, the target reported to generate the brightest and most consistent phosphenes was selected as the target to continue data collection. At this target, stimulation intensity was increased and decreased in 2%, then 1% increments, to determine the phosphene threshold, which was defined as the lowest stimulation intensity that resulted in a phosphene on at least 5 of 10 trials. Participants traced phosphenes on screen after each trial, and area was calculated. Adapted from Khammash et al. (2019a); b) MNI locations of TMS hot spots in left primary visual cortex. n = 38 participants.

The TMS protocol consisted of a total of 50 single pulses, comprised of 10 pulses delivered at each of 60%, 80%, 100%, 120%, and 140% of the participants’ phosphene threshold. Pulses were presented in a pseudorandom order. We previously demonstrated that when a test stimulus of 120% PT is delivered 2 ms after a conditioning stimulus of 45% PT, phosphene size is significantly inhibited compared to when the test stimulus is delivered alone (Khammash et al. 2019b). Participants were therefore administered 10 paired pulses with these parameters, and phosphenes elicited by this paired-pulse stimulation were then compared to phosphenes elicited by the same test stimulus (120% of PT) but without a preceding conditioning stimulus (i.e. single pulse).

Data preprocessing

MRS analysis and GABA estimation

The MATLAB toolbox Gannet (version 3.2, Edden et al. 2014) was used to preprocess the MRS data and to estimate GABA concentration in the left primary visual MRS voxel. Spectral registration was used to frequency and phase-correct time-resolved data. Time-resolved data were filtered with 3 Hz exponential line broadening and zero-filled by a factor of 16. The 3-ppm GABA peak in the difference spectrum was modeled using a five-parameter Gaussian model between 2.19 and 3.55 ppm. Co-edited macromolecule signals overlap with GABA and make a significant contribution (up to 50%) of the GABA signal (Harris et al. 2015a; Harris et al. 2017). Therefore, all GABA values we report are a combination of GABA and macromolecules, and shall be described as GABA+, in line with previous literature conventions. GABA+ was quantified relative to water, which was fit using a Gaussian–Lorentzian model, and is expressed in institutional units (i.u.).

GABA levels and water relaxation times differ across tissue type (i.e. gray matter, white matter, cerebrospinal fluid) and voxel tissue composition varies across participants. For each participant, the gray matter, white matter, and cerebrospinal fluid fractions of their MRS voxel were calculated by co-registering the MRS voxel to their anatomical image using the SPM12 segmentation function, which is integrated into Gannet. These fractions were then used to correct GABA+ estimates for voxel composition using two methods. The first, as described by Gasparovic et al. (2006), and which we refer to as tissue correction, corrects for the tissue composition of the voxel and the associated differences in water concentration and tissue relaxation time. The second method, detailed by Harris et al. (2015b), and which we refer to as α-corrected, is like that of Gasparovic et al. (2006) but additionally considers the different levels of GABA within white matter and gray matter. While modifications of the α-correction measure scale by the average gray matter and white matter composition of all datasets in the group (named ConcIU_AlphaTissCorr_GrpNorm in Gannet), we instead used a version that scales each participant to their individual white matter and gray matter fractions (named ConcIU_AlphaTissCorr in Gannet). We felt that this was most appropriate as there typically are significant anatomical differences between older and young adults, with older participants displaying cerebral atrophy (Fox et al. 2004). Thus, correcting each group to its respective average may introduce systematic differences into the GABA+ estimates.

Spectra were visually inspected for artifacts across Gannet’s preprocessing steps, as well as goodness of model fit. Gannet provides a measure of fit error, and to ensure the robustness of our findings, only estimates of uncorrected, tissue-corrected, and α-corrected GABA+ with a fit error of less than 12% were included in our analysis.

TMS data quality control

As phosphenes are a self-report measure, there is the concern that participants may respond in a way that they perceive to be desirable to the experimenter rather than reporting their true experience, even unintentionally. To mitigate this, during data collection, we assured participants that some individuals do not see phosphenes, and we additionally established quantitative criteria to determine the reliability of a participant’s data. Our previous work showed that phosphene sizes scale linearly with stimulus intensity for single pulses ranging from 80% to 140% of PT (Khammash et al. 2019a), much like MEPs’ scale with stimulus intensity in motor cortex (Kiers et al. 1993). Therefore, for each participant, we assessed phosphene size as a function of stimulus intensity, by fitting a linear regression model to the data from the single-pulse 80% to 140% PT conditions. For each participant, if stimulus intensity was a significant predictor of phosphene size, we included that participant’s data in further analysis. If it did not, their data were excluded from further analysis.

Statistical analysis

All analyses were performed using R (version 4.2.3). Data manipulation was performed using the “dplyr” (Wickham et al. 2023) and “tidyr” (Wickham et al. 2024) packages. Linear mixed-effects models were performed using the “lme4” (Bates et al. 2015) and “lmerTest” (Kuznetsova et al. 2017) packages. The “ggplot2” package was used for data visualization (Wickham et al. 2016).

Demographics and sample characteristics

Age differences in demographic variables and sample characteristics were assessed using independent-sample t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables.

Five logistic regression analyses were conducted to determine whether uncorrected GABA+ concentrations, tissue-corrected GABA+ concentrations, α-corrected GABA+ concentrations, percentage of gray matter within the MRS voxel, or age group were significant predictors of whether a participant reported being able to see phosphenes. These regression analyses were performed on a sample that included the participants who reported seeing phosphenes and who completed the full TMS protocol, the participants who did not report seeing phosphenes, and the participants who reported seeing phosphenes, but whose phosphene thresholds were too high to run the complete protocol. Individuals whose data were determined to be unreliable (i.e. individuals who reported seeing phosphenes, but for whom stimulus intensity was not a significant predictor of phosphene size) were not included in this analysis. Separate logistic regressions were conducted for each predictor to avoid issues of multicollinearity, since the predictors were not independent. For all demographic and sample characteristic analyses, P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Single-pulse TMS data

For each participant, single-pulse recruitment curves were derived from the single-pulse intensities (80%, 100%, 120%, and 140% of PT) by averaging the phosphene size (as a percentage of the screen size) traced at each intensity. To investigate the effects of age group and stimulus intensity on phosphene size, a linear mixed model was fit using the phosphene size data from the single-pulse stimulations as an outcome measure. This model included stimulation intensity (80%, 100%, 120%, and 140% of PT) as a within-subject factor, age group (young, older) as a between-subjects factor, and an age group × stimulation intensity interaction term as fixed effects. Participant was included in the model as a random-effect intercept term. Trials were only included in the model if a phosphene was elicited. We did not include single-pulse intensities of 60% of PT in this analysis, as most participants (59%) did not see phosphenes on trials when they were stimulated at this intensity. Since the outcome measure (phosphene size) was not normally distributed, we performed a log transform on the data.

Three planned comparisons with a Bonferroni-adjusted alpha level of 0.0167 (0.05/3) were conducted between each successive stimulus intensity to determine the effect of increasing stimulation intensity on phosphene size.

As noted in the TMS Data Quality Control section, participants were only included in further analyses if stimulus intensity was a significant predictor of phosphene size, which essentially guarantees a significant main effect of stimulation intensity in the linear mixed model and significant planned comparisons. Therefore, this analysis was repeated with data from all participants who reported seeing phosphenes—including those whose data did not pass TMS quality control—and full results of this analysis are reported in the Supplementary Materials.

Age differences in visual cortical inhibition

In two independent groups of young healthy participants, we have previously demonstrated that a conditioning stimulus that is 45% of PT is optimal for reducing the size of phosphenes elicited by a test stimulus of 120% of PT, relative to a single-pulse condition (Khammash et al. 2019a, 2019b). Here, we wished to determine if this inhibitory effect was reduced in older adults in comparison with young adults. We fit a linear mixed-effects model on phosphene size as a percentage of the projection screen as the outcome measure, with up to 20 observations per participant (10 single pulse and 10 paired pulse). Age group (young, older), stimulus condition (single pulse, paired pulse), and an age group × stimulus condition interaction were included in the model as fixed effects, and participant intercept was included as a random effect. Again, trials were only included in the model if a phosphene was elicited. To reduce the skewness of the response variable and to ensure normality of residuals, a log transformation was applied to the dataset. Significant interaction effects were probed using post hoc pairwise comparisons.

Relationship between visual cortical inhibition and MRS GABA+ estimates

Average phosphene sizes in the 120% of PT single-pulse (no conditioning stimulus) and 120% of PT paired-pulse (conditioning stimulus at 45% of PT) conditions were calculated for each participant. Then, using these two values, an index of visual cortical inhibition was calculated for each participant using the following formula:

.

.

For this measure, a value of 0 means that there was no difference in phosphene size during the conditioned and unconditioned conditions while a value of 1 means that the conditioning pulse eliminated the phosphene completely. Regression analyses were then performed to determine whether GABA+/H2O predicted the TMS index of visual cortical inhibition. Age group was included in the regression, to ensure that age effects were not the driver of significant effects. Separate regressions were performed for uncorrected, tissue-corrected, and α-corrected measures of left primary visual GABA+, since findings involving uncorrected GABA+ estimates may be driven by differences in tissue composition between young and older adults.

To determine whether significant relationships between visual cortical inhibition and GABA+ concentrations were driven by differences in voxel tissue composition, we ran regression analyses assessing whether visual cortical inhibition was predicted by voxel gray matter percentages.

Age differences in GABA+

Age differences in MRS-derived GABA+ were assessed using independent-sample t-tests; P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Final sample size and characteristics

Of the 78 participants who participated in the study, we were unable to successfully estimate GABA+ values from 3 participants (1 young and 2 older) due to data quality issues. Our MRS dataset therefore included 28 young adults and 47 older adults.

Of the 75 participants in our MRS dataset, we were unable to elicit phosphenes from 3 young and 15 older participants, despite testing at a range of stimulus intensities and target locations. The proportion of young adults who did not report seeing phosphenes (~10%) was lower than in our previous works, in which we investigated the phosphene response in a young population (Khammash et al. 2019a, 2019b). An additional 3 young and 8 older adults had phosphene thresholds that were too high for us to be able to run the full TMS protocol based on the limits of our TMS stimulator (i.e. their phosphene thresholds were such that the TMS stimulator could not stimulate at 120% or 140% of phosphene threshold). TMS data from 1 young and 5 older adults were excluded for not meeting reliability criteria for inclusion (as per TMS Data Quality Control section). Two participants (1 young, 1 older) withdrew from the study, and 1 young adult was excluded following a vasovagal syncope event resulting from TMS. Subsequently, the final sample from which we obtained both MRS and TMS data included 19 young adults and 18 older adults.

Participant demographics for the MRS sample and the MRS and TMS sample are presented in Table 1. There were no significant differences in the gender breakdown of the young and older groups in either of the samples, nor were there significant differences between the groups in years of education. In both the MRS sample, and the TMS and MRS sample, older participants had significantly lower visual acuity scores (P values < 0.0001) than young participants, as assessed using the NIH toolbox Visual Acuity Test (Varma et al. 2013).

Table 1.

Mean and standard deviations of participant demographics.

| MRS sample | MRS and TMS sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young adults (n = 28) |

Older adults (n = 47) |

Group Differences | Young adults (n = 19) |

Older adults (n = 18) |

Group differences |

|

| Age at enrollment | 22.61 (±2.90) | 70.45 (±4.75) |

t

72.93 = −54.18, P < 0.0001 |

22.32 (±2.91) | 70.50 (±4.64) |

t

28.29 = −37.60, P < 0.0001 |

| Gender (W:M) | 13:15 | 27:20 | χ2(1) = 0.86, P = 0.35 |

8:11 | 10:8 | χ2(1) = 0.67, P = 0.41 |

| Years of education | 23.32 (±3.75) | 22.21 (±1.90) |

t

35.39 = 1.46, P = 0.15 |

23.89 (±3.71) | 22.22 (±1.48) |

t

23.82 = 1.82, P = 0.08 |

| Visual acuity | 107.5 (± 7.13) | 93.45 (±8.72) |

t

65.86 = 7.59, P < 0.0001 |

107.70 (±7.67) | 94.78 (±10.07) |

T

31.75 = 4.39, P < 0.0001 |

| Phosphene threshold (% of maximum stimulator output) | ND | ND | ND | 63.58 (±11.69) | 68.33 (±8.57) | t32.99 = −1.42, P = 0.17 |

MRS, magnetic resonance spectroscopy; TMS, transcranial magnetic stimulation; W, women; M, men; ND, no data.

Within the MRS and TMS sample, average phosphene threshold was 65.89% (±10.43%) of maximum stimulator output. Average phosphene threshold was 63.58 (±11.69%) and 68.33% (± 8.57%) of the maximum stimulator output in the young and older participants, respectively. Statistical comparison revealed no significant difference in phosphene threshold between the young and older groups (t32.99 = −1.42. P = 0.17). Figure 2 shows the left primary visual cortex hotspots for all participants.

To determine significant predictors of whether an individual reported seeing phosphenes, we performed a series of five separate logistic regressions, which included MRS voxel gray matter percentage, uncorrected GABA+ estimates, tissue-corrected GABA+ estimates, α-corrected GABA+ estimates, and age group as predictors of whether phosphenes were perceived. Separate logistic regressions were performed to avoid multicollinearity, since our predictor candidates were not independent. These regressions were performed on a sample of 69 participants, which included the participants who ran through the full TMS protocol (n = 38), the participants who did not report seeing phosphenes (n = 19), and the participants who reported seeing phosphenes, but whose phosphene thresholds were too high to run the TMS protocol (n = 12). These logistic regressions indicated that including TMS gray matter percentage [χ2(1) = 0.89, P = 0.34], uncorrected GABA+ estimates [χ2(1) = 0.01, P = 0.91], tissue-corrected GABA+ estimates [χ2(1) = 0.18, P = 0.67], or α-corrected GABA+ [χ2(1) = 1.17, P = 0.28], did not significantly improve the fit of the regression model, when compared with the intercept only model. Including age group in the model produced a significant improvement in model fit χ2(1) = 5.85, P = 0.02, with members of the older group 78% less likely to report seeing phosphenes than those in the young group (OR = 0.22, 95% CI [0.04, 0.76]).

Since a higher proportion of older adults did not report seeing phosphenes, we compared the MRS voxel gray matter percentages of older adults who did see phosphenes with the MRS voxel gray matter percentages of the older adults who did not report seeing phosphenes, to determine if there were any systematic differences. There were no significant differences in MRS voxel gray matter percentages between the older adults who reported seeing phosphenes and those who did not (t26.25 = −0.33, P = 0.75).

Single-pulse TMS data

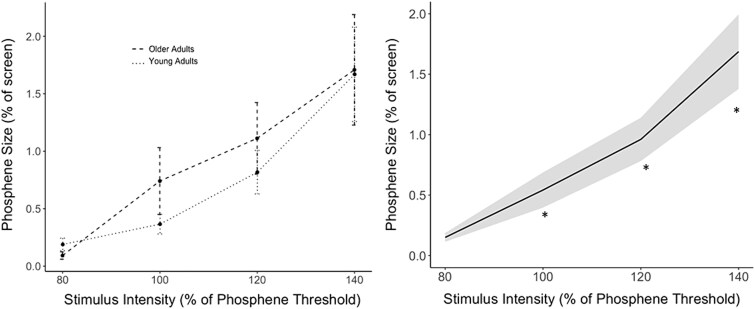

A linear mixed model revealed a significant linear effect of stimulus intensity on phosphene size (β = 1.51, SE = 0.17, t804.23 = 9.09, P < 0.0001). There were no differences in phosphene size between the age groups (β = 0.22, SE = 0.46, t36.17 = 0.48, P = 0.64), and age did not interact with the linear effect of stimulus intensity (β = 0.11, SE = 0.22, t803.15 = 0.50, P = 0.62). Paired t-tests indicated that phosphene size was positively associated with stimulus intensity, significantly increasing (P’s < 0.01) with incremental increases in stimulus intensity between 80% and 140% of PT (Fig. 3b). Means and standard deviations of raw, nontransformed data are displayed in Table 2.

Fig. 3.

a) Phosphene size as a function of single-pulse intensity for both young and older adults. Points represent mean phosphene size at each stimulation intensity. Error bars present the standard error of the mean. b) Mean phosphene size as a function of single-pulse stimulation for the whole sample. *indicate a stimulation intensity that produces significantly larger phosphenes than the previous intensity, with a P-value that survives correction for multiple comparisons (P < 0.0167). Error ribbon represents the standard error of the mean.

Table 2.

Mean and standard deviation phosphene sizes in young and older adults, for single-pulse and paired-pulse conditions.

| Paradigm | Condition | Phosphene size (% of screen) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Young group (n = 19) |

Older group (n = 18) |

||

| Single pulse (% of phosphene threshold) | 80% | 0.19 ± 0.19 | 0.09 ± 0.09 |

| 100% | 0.37 ± 0.36 | 0.74 ± 1.16 | |

| 120%* | 0.82 ± 0.82 | 1.11 ± 1.32 | |

| 140% | 1.67 ± 1.79 | 1.71 ± 1.92 | |

| Paired pulse (conditioning stimulation % of phosphene threshold) | 0%* | 0.82 ± 0.82 | 1.11 ± 1.32 |

| 45% | 0.45 ± 0.46 | 1.02 ± 1.17 | |

aSingle-pulse 120% and paired-pulse 0% conditioning stimulus conditions are equivalent, with values derived from the same trials.

We repeated this analysis, including participants for whom stimulus intensity was not a significant predictor of phosphene size, and found the same pattern of results (see Supplementary Materials for statistics).

Age differences in visual cortical inhibition

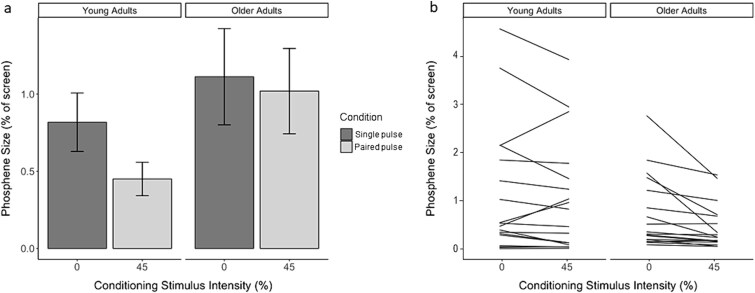

Results of the linear mixed-effects model indicated a significant interaction effect of age and condition (paired-pulse vs single-pulse) on phosphene size (β = −0.40, SE = 0.16, t507.85 = 2.48, P = 0.01). There were no main effects of age (β = 0.12, SE = 0.47, t36.37 = 0.26, P = 0.80) or condition (β = −0.16, SE = 0.12, t507.33 = −1.36, P = 0.17). Examination of this significant interaction revealed that young adults experienced a significant reduction in phosphene size in response to the conditioned stimulus (estimated difference = 0.56, SE = 0.11; 95% CI [0.34, 0.78], P < 0.0001), while the older adults did not (estimated difference = 0.16, SE = 0.12; 95% CI [−0.07, 0.38], P = 0.17), reflecting decreased visual cortical inhibition with age (Fig. 4a and b).

Fig. 4.

a) Bar graph of phosphene size as a function of condition for young and older adults. Bars represent the average size of phosphenes elicited during either the single-pulse (no conditioning stimulation) or paired-pulse (conditioning stimulation at 45% of PT) condition. n = 19 young adults, 18 older adults. Error bars indicate standard error of the mean. b) Average phosphene size as a function of condition for each participant. A linear mixed-effects model was fit with age and condition as fixed effects and participant as a random intercept effect. Each participant is represented by a separate line. Steeper negative slopes indicate stronger inhibition of phosphene size resulting from the conditioning stimulus.

We also performed the same analysis while including gray matter percentage of the MRS voxel as a nuisance covariate, and the age × condition interaction (β = −0.40, SE = 0.16, t507.86 = −2.49, P = 0.01) remained significant, suggesting that bulk tissue differences were not driving the effects.

Relationship between cortical inhibition and GABA+

Regression analyses revealed that uncorrected GABA+ concentrations estimated using MRS significantly predicted visual cortical inhibition assessed using ppTMS (β = 0.71, SE = 0.29, t35 = 2.46, P = 0.02). When age group was included in the model, the relationship approached significance (β = 0.59, SE = 0.32, t34 = 1.86, P = 0.07). Across all participants, tissue-corrected left primary visual GABA+ concentrations significantly predicted the ppTMS measure of visual cortical inhibition (β = 0.75, SE = 0.23, t35 = 3.22, P = 0.003). This relationship remained significant when age group was included in the model (β = 0.70, SE = 0.23, t34 = 3.09, P = 0.004, Fig. 5b). Regression analyses revealed that the relationship between α-corrected GABA+ and visual cortical inhibition approached significance, both with and without age group included in the model (without age: β = 0.42, SE = 0.21, t35 = 2.02, P = 0.051, Fig. 5c; with age: β = 0.38, SE = 0.20, t34 = 1.86, P = 0.072). We did not observe significant relationships between visual cortical inhibition, and MRS voxel gray matter percentage (β = 0.03, SE = 0.02, t35 = 1.66, P = 0.11).

Fig. 5.

Scatter plots showing the relationship between TMS-elicited phosphene size and a) uncorrected GABA+, b) tissue-corrected GABA+, and c) α-corrected GABA+ for the whole sample (solid line), young adults (circles, dotted line), and older adults (triangles, dashed line). n = 19 young adults, 18 older adults.

Age differences in primary visual cortex GABA+

Uncorrected, tissue-corrected, and α-corrected GABA+ values, alongside the average tissue composition of the MRS voxel, are provided in Table 3 for the MRS sample, as well as the subsample for which we obtained TMS data. Figure 6 presents heatmaps describing the MRS voxel locations in all participants, as well as example spectra. In both the full MRS sample and the subsample with TMS data, young adults had greater gray matter percentages and lower cerebrospinal fluid percentages than older adults (all P’s < 0.001). There were no significant age differences in white matter percentages. In addition, there were no differences in GABA+ fit error or full width at half maximum (FWHM) between the groups.

Table 3.

Means and standard deviations of voxel tissue composition percentages, MRS quality control metrics, and MRS-derived estimations of water reference uncorrected, tissue-corrected, and α-corrected GABA+/H2O in left primary visual of young and older adults. All values in institutional units.

| MRS sample | MRS and TMS sample | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Young adults (N = 28) |

Older adults (n = 47) |

Group differences | Young adults (n = 19) |

Older adults (n = 18) |

Group differences | |

| Voxel tissue composition measure | ||||||

| Gray matter (%) | 47.59 ± 3.60 | 41.85 ± 3.97 |

t

61.44 = 6.42, P < 0.0001 |

47.94 ± 3.13 | 42.54 ± 3.55 |

t

33.88 = 4.89, P < 0.0001 |

| White matter (%) | 45.55 ± 3.93 | 46.03 ± 4.21 |

t

60.03 = −0.50, P = 0.62 |

45.35 ± 3.62 | 45.40 ± 4.37 |

t

33.10 = −0.04, P = 0.97 |

| CSF (%) | 6.86 ± 2.99 | 12.12 ± 4.45 |

t

71.86 = −6.11, P < 0.0001 |

6.71 ± 3.30 | 12.06 ± 4.10 |

t

32.66 = −4.35, P < 0.001 |

| MRS quality control metrics | ||||||

| GABA+ Fit Error | 3.31 ± 0.81 | 3.06 ± 0.61 |

t

45.23 = 1.40, P = 0.17 |

3.46 ± 0.83 | 3.13 ± 0.58 |

t

32.35 = 1.38, P = 0.18 |

| GABA+ FWHM | 18.44 ± 1.42 | 18.76 ± 1.29 |

t

52.47 = −0.97, P = 0.34 |

18.21 ± 1.07 | 18.64 ± 1.55 |

t

30.00 = −0.97, P = 0.34 |

| GABA+ estimation | ||||||

| Uncorrected GABA+/H2O | 1.85 ± 0.19 | 1.73 ± 0.23 |

t

65.74 = 2.41, P = 0.02 |

1.87 ± 0.21 | 1.68 ± 0.24 |

t

33.48 = 2.54, p = 0.02 |

| Tissue-corrected GABA+/H2O | 2.11 ± 0.18 | 2.06 ± 0.33 |

t

72.61 = 0.75, P = 0.45 |

2.15 ± 0.17 | 2.08 ± 0.38 |

t

23.10 = 0.69, P = 0.50 |

| α-corrected GABA+/H2O |

2.92 ± 0.31 | 2.97 ± 0.39 |

t

66.68 = −0.55, P = 0.59 |

2.94 ± 0.32 | 2.86 ± 0.37 |

t

33.91 = 0.70, P = 0.49 |

CSF, cerebrospinal fluid; FWHM, full width at half maximum.

Fig. 6.

a) Heatmaps describing MRS voxel placement overlap across all MRS participants. b) Example MRS spectra. c) Bar graph of uncorrected, tissue-corrected, and α-corrected left primary visual GABA+ concentrations in young and older participants. Bars represent average GABA+ concentrations for each group. Dots represent observations from individual participants. n = 28 young adults, 47 older adults. Error bars represent standard deviations.

In the full MRS sample, uncorrected GABA+ values were significantly higher in young adults, compared with older adults (t65.74 = 2.41, P = 0.02). When tissue-corrected and α-corrected GABA+ values were examined, this difference between age groups was eliminated (tissue-corrected GABA+: t72.61 = 0.75, P = 0.45; α-corrected GABA+: t66.68 = −0.58, P = 0.59).

Analyses were repeated in the subset of participants from whom we had obtained both MRS and TMS data from, which demonstrated the same pattern of results (uncorrected GABA+: t33.48 = 2.54; P = 0.02; tissue-corrected GABA+: t23.10 = 0.69; P = 0.50, α-corrected GABA+: t33.91 = 0.70; P = 0.49).

Discussion

The present study used a bimodal approach to explore age differences in cortical inhibition in the visual system, investigating TMS-measured inhibitory function and MRS-derived GABA+ in left primary visual cortex, as well as the relationship between the two measures. We first showed that our phosphene tracing paradigm can be successfully used in an older adult population. We then demonstrated three main findings: (i) Older adults exhibit reduced visual cortical inhibition when compared to young adults. (ii) Greater TMS-measured inhibitory activity in left primary cortex is associated with higher MRS-derived tissue-corrected GABA+ levels. (iii) Uncorrected GABA+ levels in left primary visual cortex are lower in older adults compared to young adults.

Using phosphene-tracing paradigm in older adults

Our group has previously established phosphene tracing as a valid and reliable tool for measuring cortical inhibition in primary visual cortex (Khammash et al. 2019a, 2019b). Single pulse recruitment curves from the present study show that this method can be successfully extended to older adult populations, as both age groups respond similarly to primary visual cortex stimulation. Both young and older adults experience scaling of phosphene size with increased stimulus intensity, with no significant differences between groups.

Cross-sectional age differences in TMS measures of visual cortical inhibition

Our results indicate that older adults exhibit weaker cortical inhibition in visual cortex than younger adults, as evidenced by less reduction in conditioned phosphene size compared with unconditioned phosphene size. To our knowledge, this is the first demonstration of age-related changes in visual cortical inhibition, as assessed by ppTMS.

Motor cortical inhibition, as quantified with SICI, does not change significantly with age (Bhandari et al. 2016). It is unsurprising that there may be age-related differences in cortical inhibition in some regions, but not others, as it is well documented that age-related changes in the brain are not uniform and some regions may be affected more than others (Trollor and Valenzuela 2001; Scahill et al. 2003). Several age-related changes in the brain can be explained in part by changes in gene expression levels (Kumar et al. 2013; Smith et al. 2021), which are sometimes associated with chronological age (Kumar et al. 2013). GABA is synthesized by two co-expressed isoforms of the same enzyme, glutamic acid decarboxylase (GAD). GAD65 is found in axon terminals and synthesizes GABA that is bound for release in the synaptic terminal (Feldblum et al. 1995; Soghomonian and Martin 1998). This on-demand pool of phasically active GABA plays a role in inhibitory synaptic transmission (Bell et al. 2021). The other isoform, GAD67, is localized in the cell body and maintains the basal pool of GABA (Feldblum et al. 1995; Soghomonian and Martin 1998). GAD67-synthesized GABA is tonically active and modulates inhibition via extrasynaptic receptors (Soghomonian and Martin 1998). While GAD65 declines with age in human visual cortex, it appears to remain stable in primary motor cortex (Pandya et al. 2019), a pattern that offers a potential explanation as to why we observed significant age-related reductions in TMS measures of visual cortical inhibition, whereas there do not appear to be significant declines in TMS measures of motor cortical inhibition (Bhandari et al. 2016).

Relationship between TMS measures of visual cortical inhibition and MRS-derived primary visual GABA+ estimates

We observed a significant positive relationship between a TMS measure of visual cortical inhibition, and tissue-corrected primary visual GABA+ estimated using MRS. This relationship was present when we controlled for age in the model. Interestingly, previous studies have failed to observe a relationship between GABA+ and motor cortical inhibition (Stagg et al. 2011; Tremblay et al. 2013; Cuypers and Marsman 2021). It is likely that key physiological differences between primary visual and primary motor are responsible for these different results. As we note in the Introduction, the mean areal density of GABAA receptors is highest in visual cortex, with a maximum in primary visual cortex, while the lowest densities are found in motor cortex (Zilles and Palomero-Gallagher 2017). We hypothesize that due to this increased density of GABAA receptors, basal GABA in visual cortex may have had a greater influence on cell excitability than in motor cortex, thus leading to a positive association between MRS measures of GABA and TMS-measured inhibitory activity.

While the relationships between TMS-measured inhibition and the three GABA+ estimations were similar, only the relationship between tissue-corrected GABA+ reached significance. However, the similarity of these relationships suggests to us that this relationship was not simply driven by differences in the tissue composition of the brain.

Cross-sectional age differences in MRS measures of primary visual GABA+

Older adults had lower concentrations of uncorrected GABA+ compared with younger adults, but there were no significant age differences in tissue-corrected GABA+ or α-corrected GABA+. While this finding contradicts studies in which an age-related decrease in corrected GABA+ estimates has been observed in visual regions (Hermans et al. 2018; Simmonite et al. 2018), it is in line with the findings of Maes et al. (2018) and Porges et al. (2017) who explored the impact of different correction approaches on age-related GABA+ differences, concluding that differences often disappear when correction is used.

Even over the course of healthy aging, the brain is subject to atrophy. Brain weight declines approximately 5% per year over the age of 40 (Svennerholm et al. 1997) with the rate increasing after the age of 70 (Scahill et al. 2003). This loss of neurons with age results in markedly different tissue composition of MRS voxels in young and older adults. Because the distribution of GABA differs across tissue types, with cerebrospinal fluid containing negligible amounts and gray matter containing roughly twice the amount of that present in white matter (Harris et al. 2015b), this difference in tissue composition has predictable effects on MRS-derived GABA+ estimates. This likely explains why, when GABA+ concentrations were corrected for voxel tissue compositions, there were no significant effects of age, unlike those observed in uncorrected GABA+. These results imply that although levels of GABA+ associated with primary visual gray matter may not decline with age, overall levels of GABA+ do, largely because of reductions in gray matter volume. While it is possible that correcting for the composition of the voxel (and therefore controlling for brain atrophy) reduced the size of the age-related effect and our study simply did not have enough power to reveal it, the pattern of findings we present does not support this.

Our measure of GABA+ likely includes significant contributions from macromolecules (Harris et al. 2015a; Harris et al. 2017). While it is possible that age-related differences in macromolecular profile could have driven our results, it is unlikely, since evidence suggests that older adults have a higher macromolecular content in the occipital cortex compared with young adults (Marjańska et al. 2018).

Limitations

An important limitation of the present study was the reduction of our sample size, following exclusion of participants who did not report seeing phosphenes. TMS preferentially activates neurons oriented perpendicularly to the plane of the magnetic field, and some individuals may have a greater proportion of primary visual cortex neurons that were not stimulated. Additionally, some participants simply may have had trouble identifying phosphenes. Studies have reported that almost 100% of young adult participants report seeing phosphenes following multiple training sessions (Kammer and Baumann 2010). It is possible that, with more training time, more of our participants would have reported seeing phosphenes.

Several participants may have had a phosphene threshold higher than the maximum output of our TMS stimulator, and we suspect that this may have been the case for many of our excluded older participants. Age-related brain atrophy leads to an increase in the brain-to-scalp distance, and because magnetic field strength diminishes with distance, higher stimulation intensities are needed to achieve the same degree of tissue stimulation. Studies of motor cortex indicate that brain-to-scalp distance is a significant determinant of motor threshold (McConnell et al. 2001). Indeed, analysis of the tissue compositions of the MRS voxels we acquired revealed significant differences in grey matter and cerebrospinal fluid between the groups, consistent with atrophy in the older adults. Regardless, the exclusion of the individuals who did not report seeing phosphenes—especially the disproportionate number of older adults—may have removed an important source of variability from the TMS dataset.

Of the 37 participants in whom we successfully elicited phosphenes, eight participants (3 young adults and 5 older adults) demonstrated facilitation in response to the paired-pulse condition—i.e. the phosphenes that were elicited in response to a test stimulus that followed a conditioning pulse were larger in comparison with phosphenes elicited by an unconditioned test stimulus. The finding of such facilitation was surprising, based on our previous investigations of the temporal dynamics of local inhibitory and facilitatory networks in visual cortex, in which we found that, when preceding the test stimulus by 2 - 5 ms, a conditioning pulse of 45% of an individual’s phosphene threshold led to uniform suppression of phosphenes across all participants in our sample of young adults (Khammash et al. 2019b). Given that there were both young and older adults within the small group of participants in the present sample that demonstrated facilitation, it does not seem likely that this finding is age-related. In our previous study, we also explored a conditioning pulse of 75% of phosphene threshold, which elicited a much more varied response, with some participants demonstrating inhibition and other facilitation. It may be that the parameters we used here were simply not optimal for all participants.

A further limitation is the poor spatial resolution of MRS. The spatial resolution is quite coarse, with a typical voxel measuring around 3 cm × 3 cm × 3 cm. The inability to collect GABA+ estimates from a smaller region limits our ability to closely match the exact area of neuronal tissue being activated by TMS.

Lastly, though pharmacological evidence has demonstrated that SICI in motor cortex is mediated by GABAA receptor subtypes (Ziemann et al. 1996; Di Lazzaro et al. 2000; Di Lazzaro et al. 2005a; Di Lazzaro et al. 2005b), to our knowledge, the mechanisms underlying this effect in visual cortex have not been explored. We therefore cannot unambiguously attribute the observed inhibitory effects to GABAA receptors. Indeed, previous investigation of phosphene perception has implicated glutamatergic activity in primary visual cortex (Terhune et al. 2015).

Conclusion

The present study provides evidence for age-related reductions of inhibition in visual cortex, as assessed using ppTMS. We also demonstrate a positive relationship between this measure of visual cortical inhibition and MRS-derived tissue-corrected primary visual GABA+ concentrations in older adults. Future work should investigate the trajectory of visual cortical inhibition across the lifespan, by including middle-aged adults and examining age-related changes longitudinally.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Molly Simmonite, Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan, 4250 Plymouth Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, United States; Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, 530 Church Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, United States.

Dalia Khammash, Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, 530 Church Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, United States.

Katherine J Michon, Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, 530 Church Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, United States.

Abbey Hamlin, Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, 530 Church Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, United States.

Stephan F Taylor, Department of Psychiatry, University of Michigan, 4250 Plymouth Road, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, United States.

Michael Vesia, School of Kinesiology, University of Michigan, 830 North University, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, United States.

Thad A Polk, Department of Psychology, University of Michigan, 530 Church Street, Ann Arbor, MI 48109, United States.

Author contributions

Molly Simmonite: Formal Analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Project Administration; Dalia Khammash: Conceptualization, Methodology, Investigation, Formal Analysis, Writing - Original Draft, Writing - Review & Editing, Visualization, Funding Acquisition, Project Administration; Katherine J. Michon: Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing, Project Administration; Abbey Hamlin: Investigation, Writing - Review & Editing; Stephan F. Taylor: Conceptualization, Methodology; Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision; Michael Vesia: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision; Thad A. Polk: Conceptualization, Methodology, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Funding Acquisition.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (grant number R01AG050523) and the Office of Research Infrastructure Programs at the National Institutes of Health (grant number S10OD026738).

Conflict of interest statement: None declared.

References

- Andersen GJ. Aging and vision: changes in function and performance from optics to perception. Wiley Interdiscip Rev Cogn Sci. 2012:3(3):403–410. 10.1002/wcs.1167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ball K, Sekuler R. Improving visual perception in older Observers1. J Gerontol. 1986:41(2):176–182. 10.1093/geronj/41.2.176. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bates D, Mächler M, Bolker B, Walker S. Fitting linear mixed-effects models using lme4. J Stat Softw. 2015:67(1):1–48. 10.18637/jss.v067.i01. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bell T, Stokoe M, Harris AD. Macromolecule suppressed GABA levels show no relationship with age in a pediatric sample. Sci Rep. 2021:11(1):722. 10.1038/s41598-020-80530-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bennett PJ, Sekuler AB, Ozin L. Effects of aging on calculation efficiency and equivalent noise. J Opt Soc Am A Opt Image Sci Vis. 1999:16(3):654–668. 10.1364/JOSAA.16.000654. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhandari A, Radhu N, Farzan F, Mulsant BH, Rajji TK, Daskalakis ZJ, Blumberger DM. A meta-analysis of the effects of aging on motor cortex neurophysiology assessed by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Clin Neurophysiol. 2016:127(8):2834–2845. 10.1016/j.clinph.2016.05.363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Billino J, Pilz KS. Motion perception as a model for perceptual aging. J Vis. 2019:19(4):3. 10.1167/19.4.3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calkins DJ. Age-related changes in the visual pathways: blame it on the axon. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci 54:ORSF37–ORSF41. 2013:54(14):ORSF37–ORSF41. 10.1167/iovs.13-12784. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cassady K, Gagnon H, Lalwani P, Simmonite M, Foerster B, Park DC, Peltier SJ, Petrou M, Taylor SF, Weissman DH, et al. Sensorimotor network segregation declines with age and is linked to GABA and to sensorimotor performance. NeuroImage. 2019:186:234–244. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.11.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chamberlain JD, Gagnon H, Lalwani P, Cassady K, Simmonite M, Seidler RD, Taylor SF, Weissman DH, Park DC, Polk TA. GABA levels in ventral visual cortex decline with age and are associated with neural distinctiveness. Neurobiol Aging. 2021:102:170–177. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2021.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cirillo J, Todd G, Semmler JG. Corticomotor excitability and plasticity following complex visuomotor training in young and old adults. Eur J Neurosci. 2011:34(11):1847–1856. 10.1111/j.1460-9568.2011.07870.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook E, Hammett ST, Larsson J. GABA predicts visual intelligence. Neurosci Lett. 2016:632:50–54. 10.1016/j.neulet.2016.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuypers K, Marsman A. Transcranial magnetic stimulation and magnetic resonance spectroscopy: opportunities for a bimodal approach in human neuroscience. NeuroImage. 2021:224:117394. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2020.117394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lazzaro V, Oliviero A, Meglio M, Cioni B, Tamburrini G, Tonali P, Rothwell JC. Direct demonstration of the effect of lorazepam on the excitability of the human motor cortex. Clin Neurophysiol Practice. 2000:111(5):794–799. 10.1016/S1388-2457(99)00314-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lazzaro V, Oliviero A, Saturno E, Dileone M, Pilato F, Nardone R, Ranieri F, Musumeci G, Fiorilla T, Tonali P. Effects of lorazepam on short latency afferent inhibition and short latency intracortical inhibition in humans. J Physiol. 2005a:564(2):661–668. 10.1113/jphysiol.2004.061747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Lazzaro V, Pilato F, Dileone M, Tonali PA, Ziemann U. Dissociated effects of diazepam and lorazepam on short-latency afferent inhibition. J Physiol. 2005b:569(1):315–323. 10.1113/jphysiol.2005.092155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edden RAE, Puts NAJ, Harris AD, Barker PB, Evans CJ. Gannet: a batch-processing tool for the quantitative analysis of gamma-aminobutyric acid-edited MR spectroscopy spectra. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2014:40(6):1445–1452. 10.1002/jmri.24478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliott D, Whitaker D, MacVeigh D. Neural contribution to spatiotemporal contrast sensitivity decline in healthy ageing eyes. Vis Res. 1990:30(4):541–547. 10.1016/0042-6989(90)90066-T. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feldblum S, Dumoulin A, Anoal M, Sandillon F, Privat A. Comparative distribution of GAD65 and GAD67 mRNAs and proteins in the rat spinal cord supports a differential regulation of these two glutamate decarboxylases in vivo. J Neurosci Res. 1995:42(6):742–757. 10.1002/jnr.490420603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fox NC, Schott JM. Imaging cerebral atrophy: normal ageing to Alzheimer’s disease. The Lancet. 2004:363(9406):392–394. 10.1016/s0140-6736(04)15441-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon H, Simmonite M, Cassady K, Chamberlain J, Freiburger E, Lalwani P, Kelley S, Foerster B, Park DC, Petrou M, et al. Michigan neural distinctiveness (MiND) study protocol: investigating the scope, causes, and consequences of age-related neural dedifferentiation. BMC Neurol. 2019:19(1):61. 10.1186/s12883-019-1294-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gasparovic C, Song T, Devier D, Bockholt HJ, Caprihan A, Mullins PG, Posse S, Jung RE, Morrison LA. Use of tissue water as a concentration reference for proton spectroscopic imaging. Magn Reson Med. 2006:55(6):1219–1226. 10.1002/mrm.20901. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Habekost T, Vogel A, Rostrup E, Bundesen C, Kyllingsbæk S, Garde E, Ryberg C, Waldemar G. Visual processing speed in old age. Scand J Psychol. 2013:54(2):89–94. 10.1111/sjop.12008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AD, Puts NAJ, Barker PB, Edden RAE. Spectral-editing measurements of GABA in the human brain with and without macromolecule suppression. Magn Reson Med. 2015a:74(6):1523–1529. 10.1002/mrm.25549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AD, Puts NAJ, Edden RAE. Tissue correction for GABA-edited MRS: considerations of voxel composition, tissue segmentation, and tissue relaxations. J Magn Reson Imaging. 2015b:42(5):1431–1440. 10.1002/jmri.24903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris AD, Saleh MG, Edden RAE. Edited 1H magnetic resonance spectroscopy in vivo: methods and metabolites. Magn Reson Med. 2017:77(4):1377–1389. 10.1002/mrm.26619. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hermans L, Leunissen I, Pauwels L, Cuypers K, Peeters R, Puts NAJ, Edden RAE, Swinnen SP. Brain GABA levels are associated with inhibitory control deficits in older adults. J Neurosci. 2018:38(36):7844–7851. 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0760-18.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Higgins KE, Jaffe MJ, Caruso RC, deMonasterio FM. Spatial contrast sensitivity: effects of age, test–retest, and psychophysical method. JOSA A. 1988:5(12):2173–2180. 10.1364/JOSAA.5.002173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hua T, Li X, He L, Zhou Y, Wang Y, Leventhal AG. Functional degradation of visual cortical cells in old cats. Neurobiol Aging. 2006:27(1):155–162. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hutchinson CV, Arena A, Allen HA, Ledgeway T. Psychophysical correlates of global motion processing in the aging visual system: a critical review. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 2012:36(4):1266–1272. 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2012.02.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kammer T, Baumann LW. Phosphene thresholds evoked with single and double TMS pulses. Clin Neurophysiol. 2010:121(3):376–379. 10.1016/j.clinph.2009.12.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khammash D, Simmonite M, Polk TA, Taylor SF, Meehan SK. Probing short-latency cortical inhibition in the visual cortex with transcranial magnetic stimulation: a reliability study. Brain Stimulat. 2019a:12(3):702–704. 10.1016/j.brs.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Khammash D, Simmonite M, Polk TA, Taylor SF, Meehan SK. Temporal dynamics of Corticocortical inhibition in human visual cortex: a TMS study. Neuroscience. 2019b:421:31–38. 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2019.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kiers L, Cros D, Chiappa KH, Fang J. Variability of motor potentials evoked by transcranial magnetic stimulation. Electroencephalogr Clin Neurophysiol Potentials Sect. 1993:89(6):415–423. 10.1016/0168-5597(93)90115-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline DW, Birren JE. Age differences in backward dichoptic masking. Exp Aging Res. 1975:1(1):17–25. 10.1080/03610737508257943. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kossev AR, Schrader C, Däuper J, Dengler R, Rollnik JD. Increased intracortical inhibition in middle-aged humans; a study using paired-pulse transcranial magnetic stimulation. Neurosci Lett. 2002:333(2):83–86. 10.1016/S0304-3940(02)00986-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kujirai T, Caramia MD, Rothwell JC, Day BL, Thompson PD, Ferbert A, Wroe S, Asselman P, Marsden CD. Corticocortical inhibition in human motor cortex. J Physiol. 1993:471(1):501–519. 10.1113/jphysiol.1993.sp019912. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kumar A, Gibbs JR, Beilina A, Dillman A, Kumaran R, Trabzuni D, Ryten M, Walker R, Smith C, Traynor BJ, et al. Age-associated changes in gene expression in human brain and isolated neurons. Neurobiol Aging. 2013:34(4):1199–1209. 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2012.10.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuznetsova A, Brockhoff PB, Christensen RHB. lmerTest Package: Tests in Linear Mixed Effects Models. J Stat Softw. 2017:82(13). 10.18637/jss.v082.i13. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lalwani P, Gagnon H, Cassady K, Simmonite M, Peltier S, Seidler RD, Taylor SF, Weissman DH, Polk TA. Neural distinctiveness declines with age in auditory cortex and is associated with auditory GABA levels. NeuroImage. 2019:201:116033. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2019.116033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leventhal AG, Wang Y, Pu M, Zhou Y, Ma Y. GABA and its agonists improved visual cortical function in senescent monkeys. Science. 2003:300(5620):812–815. 10.1126/science.1082874. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin A, Andronesi O, Bogner W, Choi IY, Coello E, Cudalbu C, Juchem C, Kemp GJ, Kreis R, Krššák M, et al. Minimum reporting standards for in vivo magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRSinMRS): experts’ consensus recommendations. NMR Biomed. 2021:34(5):e4484. 10.1002/nbm.4484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maes C, Hermans L, Pauwels L, Chalavi S, Leunissen I, Levin O, Cuypers K, Peeters R, Sunaert S, Mantini D, et al. Age-related differences in GABA levels are driven by bulk tissue changes. Hum Brain Mapp. 2018:39(9):3652–3662. 10.1002/hbm.24201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marjańska M, Deelchand DK, Hodges JS, McCarten JR, Hemmy LS, Grant A, Terpstra M. Altered macromolecular pattern and content in the aging human brain. NMR Biomed. 2018:31(2):e3865. 10.1002/nbm.3865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marneweck M, Loftus A, Hammond G. Short-interval intracortical inhibition and manual dexterity in healthy aging. Neurosci Res. 2011:70(4):408–414. 10.1016/j.neures.2011.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsman A, Mandl RCW, Klomp DWJ, Cahn W, Kahn RS, Luijten PR, Hulshoff Pol HE. Intelligence and brain efficiency: investigating the association between working memory performance, glutamate, and GABA. Front Psychiatry. 2017:8:154. 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00154. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConnell KA, Nahas Z, Shastri A, Lorberbaum JP, Kozel FA, Bohning DE, George MS. The transcranial magnetic stimulation motor threshold depends on the distance from coil to underlying cortex: a replication in healthy adults comparing two methods of assessing the distance to cortex. Biol Psychiatry. 2001:49(5):454–459. 10.1016/S0006-3223(00)01039-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGinley M, Hoffman RL, Russ DW, Thomas JS, Clark BC. Older adults exhibit more intracortical inhibition and less intracortical facilitation than young adults. Exp Gerontol. 2010:45(9):671–678. 10.1016/j.exger.2010.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mikkelsen M, Barker PB, Bhattacharyya PK, Brix MK, Buur PF, Cecil KM, Chan KL, Chen DYT, Craven AR, Cuypers K, et al. Big GABA: edited MR spectroscopy at 24 research sites. NeuroImage. 2017:159:32–45. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.07.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oliviero A, Profice P, Tonali PA, Pilato F, Saturno E, Dileone M, Ranieri F, Di Lazzaro V. Effects of aging on motor cortex excitability. Neurosci Res. 2006:55(1):74–77. 10.1016/j.neures.2006.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pandya M, Palpagama TH, Turner C, Waldvogel HJ, Faull RL, Kwakowsky A. Sex- and age-related changes in GABA signaling components in the human cortex. Biol Sex Differ. 2019:10(1):5. 10.1186/s13293-018-0214-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peinemann A, Lehner C, Conrad B, Siebner HR. Age-related decrease in paired-pulse intracortical inhibition in the human primary motor cortex. Neurosci Lett. 2001:313(1–2):33–36. 10.1016/S0304-3940(01)02239-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pitchaimuthu K, Wu QZ, Carter O, Nguyen BN, Ahn S, Egan GF, McKendrick AM. Occipital GABA levels in older adults and their relationship to visual perceptual suppression. Sci Rep. 2017:7(1):14231. 10.1038/s41598-017-14577-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges EC, Woods AJ, Lamb DG, Williamson JB, Cohen RA, Edden RAE, Harris AD. Impact of tissue correction strategy on GABA-edited MRS findings. NeuroImage. 2017:162:249–256. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.08.073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Porges EC, Jensen G, Foster B, Edden RAE, Puts NAJ. The trajectory of cortical gaba across the lifespan, an individual participant data meta-analysis of edited mrs studies. elife. 2021:10. 10.7554/eLife.62575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robertson CE, Ratai E-M, Kanwisher N. Reduced GABAergic action in the autistic brain. Curr Biol. 2016:26(1):80–85. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.11.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rogasch NC, Dartnall TJ, Cirillo J, Nordstrom MA, Semmler JG. Corticomotor plasticity and learning of a ballistic thumb training task are diminished in older adults. J Appl Physiol. 2009:107(6):1874–1883. 10.1152/japplphysiol.00443.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossi S, Antal A, Bestmann S, Bikson M, Brewer C, Brockmöller J, Carpenter LL, Cincotta M, Chen R, Daskalakis JD, et al. Safety and recommendations for TMS use in healthy subjects and patient populations, with updates on training, ethical and regulatory issues: expert guidelines. Clin Neurophysiol Off J Int Fed Clin Neurophysiol. 2021:132(1):269–306. 10.1016/j.clinph.2020.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sandberg K, Blicher JU, Dong MY, Rees G, Near J, Kanai R. Occipital GABA correlates with cognitive failures in daily life. NeuroImage. 2014:87:55–60. 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.10.059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scahill RI, Frost C, Jenkins R, Whitwell JL, Rossor MN, Fox NC. A longitudinal study of brain volume changes in normal aging using serial registered magnetic resonance imaging. Arch Neurol. 2003:60(7):989–994. 10.1001/archneur.60.7.989. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmolesky MT, Wang Y, Pu M, Leventhal AG. Degradation of stimulus selectivity of visual cortical cells in senescent rhesus monkeys. Nat Neurosci. 2000:3(4):384–390. 10.1038/73957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sekuler R, Ball K. Visual localization: age and practice. J Opt Soc Am A. 1986:3(6):864–867. 10.1364/JOSAA.3.000864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shinomori K, Barbur JL, Werner JS. Chapter 13 - aging of visual mechanisms. In: Santhi N, Spitschan M, editors. Progress in brain research. Circadian and visual neuroscience. Elsevier; 2022. pp. 257–273. 10.1016/bs.pbr.2022.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simmonite M, Carp J, Foerster BR, Ossher L, Petrou M, Weissman DH, Polk TA. Age-related declines in occipital GABA are associated with reduced fluid processing ability. Acad Radiol. 2018:26(8):1053–1061. 10.1016/j.acra.2018.07.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith AE, Ridding MC, Higgins RD, Wittert GA, Pitcher JB. Age-related changes in short-latency motor cortex inhibition. Exp Brain Res. 2009:198(4):489–500. 10.1007/s00221-009-1945-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GS, Oeltzschner G, Gould NF, Leoutsakos JMS, Nassery N, Joo JH, Kraut MA, Edden RAE, Barker PB, Wijtenburg SA, et al. Neurotransmitters and Neurometabolites in late-life depression: a preliminary magnetic resonance spectroscopy study at 7T. J Affect Disord. 2021:279:417–425. 10.1016/j.jad.2020.10.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soghomonian J-J, Martin DL. Two isoforms of glutamate decarboxylase: why? Trends Pharmacol Sci. 1998:19(12):500–505. 10.1016/S0165-6147(98)01270-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Spear PD. Neural bases of visual deficits during aging. Vis Res. 1993:33(18):2589–2609. 10.1016/0042-6989(93)90218-L. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stagg CJ, Bestmann S, Constantinescu AO, Moreno Moreno L, Allman C, Mekle R, Woolrich M, Near J, Johansen‐Berg H, Rothwell JC. Relationship between physiological measures of excitability and levels of glutamate and GABA in the human motor cortex. J Physiol., 2011:589(23):5845–5855. Portico. 10.1113/jphysiol.2011.216978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Svennerholm L, Boström K, Jungbjer B. Changes in weight and compositions of major membrane components of human brain during the span of adult human life of swedes. Acta Neuropathol (Berl). 1997:94(4):345–352. 10.1007/s004010050717. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Terhune DB, Murray E, Near J, Stagg CJ, Cowey A, Cohen KR. Phosphene perception relates to visual cortex glutamate levels and Covaries with atypical visuospatial awareness. Cereb Cortex. 2015:25(11):4341–4350. 10.1093/cercor/bhv015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tremblay S, Beaulé V, Proulx S, de Beaumont L, Marjańska M, Doyon J, Pascual-Leone A, Lassonde M, Théoret H Relationship between transcranial magnetic stimulation measures of intracortical inhibition and spectroscopy measures of GABA and glutamate+glutamine. J Neurophysiol. 2013:109(5):1343–1349. 10.1152/jn.00704.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Trollor JN, Valenzuela MJ. Brain ageing in the new millennium. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2001:35(6):788–805. 10.1046/j.1440-1614.2001.00969.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Loon AM, Knapen T, Scholte HS, St John-Saaltink E, Donner TH, Lamme VAF. GABA shapes the dynamics of bistable perception. Curr Biol CB. 2013:23(9):823–827. 10.1016/j.cub.2013.03.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varma R, McKean-Cowdin R, Vitale S, Slotkin J, Hays RD. Vision assessment using the NIH toolbox. Neurology. 2013:80(11 Suppl 3):S37–S40. 10.1212/WNL.0b013e3182876e0a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wickham H, François R, Henry L, Müller K, Vaughan D. dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation [dataset]. In CRAN: Contributed Packages. The R Foundation. 2014. 10.32614/cran.package.dplyr. [DOI]

- Wickham H, Chang W, Henry L, Pedersen TL, Takahashi K, Wilke C, Woo K, Yutani H, Dunnington D, van den Brand T. ggplot2: Create Elegant Data Visualisations Using the Grammar of Graphics [dataset]. In CRAN: Contributed Packages. The R Foundation. 2007. 10.32614/cran.package.ggplot2. [DOI]

- Wickham H, Vaughan D, Girlich M. tidyr: Tidy Messy Data [dataset]. In CRAN: Contributed Packages. The R Foundation. 2014. 10.32614/cran.package.tidyr. [DOI]

- Yoon JH, Maddock RJ, Rokem A, Silver MA, Minzenberg MJ, Ragland JD, Carter CS GABA Concentration Is Reduced in Visual Cortex in Schizophrenia and Correlates with Orientation-Specific Surround Suppression. J Neurosci. 2010:30(10):3777–3781. 10.1523/jneurosci.6158-09.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemann U, Lönnecker S, Steinhoff BJ, Paulus W. Effects of antiepileptic drugs on motor cortex excitability in humans: a transcranial magnetic stimulation study. Ann Neurol. 1996:40(3):367–378. 10.1002/ana.410400306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zilles K, Palomero-Gallagher N. Multiple transmitter receptors in regions and layers of the human cerebral cortex. Front Neuroanat. 2017:11. 10.3389/fnana.2017.00078. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.