Abstract

Solid polymer electrolytes (SPEs) have been regarded as one of the most encouraging choices for lithium-based cells of the future generation as they further boost battery energy density and do away with any potential safety risks associated with liquid organic electrolytes. Nevertheless, solid electrolytes’ restricted ion conductivity hinders their hands-on applications. In this work, lithium-ion conductor SPEs based on polymer/polyoxovanadates nanocomposites are fabricated by a facile cast solution method. Polyoxovanadate Li7[V15O36(CO3)] (LVC) possesses a high diffusion coefficient which acts as lithium salt. The dual function role of polyoxovanadates in the diffusion of Li+ cations and reducing the crystallinity of polymer leads to high ion conductivity of 4.1 × 10−4 S cm−1 at room temperature. Moreover, compared to the routine CA-PEG1000-LiPF6 electrolyte, the SPE with LVC had a broader electrochemical voltage window of more than 5 V. The excellent performance as lithium salt and inorganic filler and its role in reducing the crystallinity of polymers and providing mobile cations in polymer matrix, and acceptable electrochemical properties, including considerable transference number (t+) 0.59, good stability of electrode/electrolye interface after 100 h Li plating/stripping without short-circuiting, and good specific capacity (226 mAh g−1 of LiCoO2/CA-PEG1000-LVC/Gr at 0.1 C) suggest LVC as lithium salt and also as inorganic fillers for designing new SPEs with high performance for next-generation lithium-based batteries.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-03169-3.

Keywords: Lithium-ion batteries, Solid polymer electrolyte, Polyoxometalates, Nanocomposites

Subject terms: Chemical engineering, Electrochemistry

Introduction

Lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) have advanced quickly in recent years due to their use in grid energy storage, transportable electronics, and electric vehicles (EVs)1,2. LIBs require to have improved cycling and safety, and high-performance electrolyte materials. Presently, a significant barrier to the further development of LIBs is the safety concerns resulting from the flammable carbon-based solvents in conventional non-aqueous liquid electrolytes, which include fire, explosion, and electrolyte leakage3. With regard to post-Li-ion batteries with greater energy density, such as Li-metal, Li-S, and Li-O2 batteries, these issues get even more severe4–6.

Replacing traditional liquid electrolytes with polymer electrolytes has been identified as a possible approach to addressing the safety concerns associated with LIBs. To create next-generation LIBs, polymer electrolytes (PEs), for instance, gel polymer electrolytes (GPEs), solid polymer electrolytes (SPEs), and composite polymer electrolytes (CPEs) are thought to be promising solid or quasi-solid electrolytes because they can overwhelm the disadvantages of common liquid electrolytes, including severe dendrite aggregation, toxicity, poor electrochemical stability window, flammability, and electrolyte leakage7–10. Additionally, SPEs have significant stretchability, processability, and flexibility due to the elastic modulus and flexure strength of the polymer chains, which permits the creation of flexible and wearable electronics11. The high electrode/electrolyte interfacial resistance causes the ionic current conduction between the anode and cathode along the SPEs path to be harder than that of liquid electrolytes12. Additionally, the lithium ion transference number (t+) and ionic conductivity remain lower than the standards needed for hands-on application13.

Typically, inorganic fillers are used in SPEs to create CPEs that enhance mechanical strength and ionic conductivity. Fillers that are used can be classified as either ionically conductive (active) or non-ionically conductive (passive)14. Inert oxide fillers efficiently improve the electrochemical characteristics of PEs by reducing the crystallinity of the matrix and encouraging the development of permeating channels through the Lewis acid-base interaction amongst the filler and polymer chains15. Many studies have employed diverse passive fillers such as SiO216, Al2O317, TiO218, etc. CPEs based on Li-ion conductor fillers demonstrate numerous advantages inherited from fillers and polymer matrices, such as high ion conductivity at room temperature, non-flammability, greater thermal and electrochemical stability, and high interface compatibility with electrodes. Unlike the previously stated CPEs with Li+-free inorganic fillers, the Li+ cations in these CPEs can flow both through the polymer chains and the Li+-conductor fillers such as Li7La3Zr2O1219, Li6.4Ga0.2La3Zr2O1220, Li6.4La3Zr1.4Ta0.6O1221,22, Li10GeP2S1223, and lithium montmorillonite24.

A novel class of nanofillers has drawn interest lately because of their distinctive characteristics. Transition metal ions that form polyoxometalates (POMs), or oxo-clusters, include Mo, W, V, Nb, and Ta25. POMs are of great interest to the disciplines of electrochemical energy storage and conversion, electronic devices, catalysis, and functional material synthesis because of their unique structure and variable redox properties26,27. POMs are categorized into explicit types, such as polyoxovanadates (POVs), polyoxotungstates (POTs), polyoxoniobates (PONbs), and polyoxomolybdates (POMos), although hetero polyoxometalates may belong to more than one of these groups28. Since they are hydrophilic and have a lot of terminal oxygen on their surface, the most POMs can function as ion conductors. The utility of POMs in energy storage and conversion is further increased by the ability of some redox-active POMs to store electrons in addition to facilitating ion movement. As a result, POMs differ greatly from mononuclear oxides in terms of their physical and chemical characteristics. Proton conduction is a routine type of ion conduction that is utilized extensively in sensors and proton exchange membranes for fuel cells. At ambient temperature, hydrated POMs exhibit the highest H+ conductivity of all proton conductors based on inorganic solid materials due to the abundance of water clusters on their surface. A high hydrophilic route in hydrated POMs leads to a fast proton transfer “quasi-liquid” state. Additionally, it has been shown that aprotic POMs possess the ability to transform into materials that conduct ions (such as Li+, Na+, and K+). POMs’ well-ordered construction improves the composite electrolyte’s mechanical stability by creating a network and free volume that makes ion storage and transit easier. In addition to serving as ion sources, these POMs have a large number of terminal oxygens—Lewis bases—on their surface. These oxygens are used to adsorb and transfer alkali metal ions, which enhances the conduction of ions in solid-state electrolytes29.

One type of POMs with an open-hollow construction is polyoxovanadate Li7[V15O36(CO3)] (LVC), which can be readily synthesized in air. It can dissociate Li+ in electrolytes because Li+ cations are distributed outside the lattice, and it has a relatively high Li+ mobility and diffusion coefficient (at the voltage range 2.2–3.9 V, ranging from 1.4 × 10−10 to 2.3 × 10−7 cm2 s−1), making it a possible candidate for fast ion conductivity30–32. LVC is utilized by Dong et al.. to build a polymer-polyoxometalate electrolyte with ionic conductivity of 9.1 × 10−5 S cm−1 at 40 °C for LIBs. In addition to improving the composite electrolyte’s mechanical strength and thermal stability and creating a strong network that prevents the growth of lithium dendrites, the addition of a rigid framework LVC decreases poly(ethylene oxide) (PEO)’s crystallinity and expands the available space for Li+ ion conduction. Additionally, the solubility of the mobile Li+ ions can be increased by the presence of LVC. This proves the opportunity of the polyoxometalate-based SPEs in solid-state LIBs with high levels of safety33. Another research employed LVC to make POVs/PSS by in situ polymerization at 80 °C and synthesized SPEs after alkali ion exchange, which demonstrate high ionic conductivity (3.3 × 10−3, 2.0 × 10−3, and 4.6 × 10−3 S cm−1 for Li+, Na+, and K+ at room temperature). The Lewis bases, namely, terminal oxygens on the surface of the LVC, can provide more sites for transporting the lithium cations and, as a result, the transfer of the ions is enhanced. Additionally, the one-dimensional structure of the synthesized SPEs increased the conductivity by reducing interface barriers and providing continuous ion conduction paths32. Encouraged by such properties, preparing a novel nanocomposite polymer electrolyte containing polyoxovanadate LVC as a multi-ion lithium salt and inorganic filler to ease the lithium ions’ transport and decrease the crystallinity of the polymer is anticipated to be an efficient approach to progress the electrochemical behavior of SPEs. The advantage of LVC as filler is its capability to reduce the crystallinity of the polymer system because inorganic fillers can act as a solid plasticizer to disrupt the orderly arrangement of polymer chains, thereby reducing the crystallinity of the polymer34. Furthermore, it can act as a multi-ion salt and provide more lithium ions with high mobility in the polymer matrix due to its high diffusion coefficient, and distribution of Li+ cations outside the lattice. Also, the Lewis bases, namely, terminal oxygens on the surface of the LVC, can provide more sites for transporting Li+ ions and, as a result, the transfer of the ions is enhanced. So, in this study, we consider the role of LVC as a lithium salt and its effect on the physiochemical and electrochemical behavior of cellulose acetate (CA)-PEG1000 solid polymer electrolyte. The SPEs show enhanced ionic conductivity, which reaches 4.1 × 10−4 S/cm at room temperature due to the low crystallinity of CA-PEG1000 in the presence of LVC nanoparticles (25.1%), with high electrochemical stability over 5 V.

Materials and approaches

Materials

Lithium carbonate (Li2CO3, Merck, 99.9%), vanadium pentoxide (V2O5, Merck, ≥ 99%), hydrazine sulfate (N2H4 ·H2SO4, Merck, ≥ 99%), lithium hexafluorophosphate (LiPF6, Sigma-Aldrich, 99.9%), dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Sigma-Aldrich, 99.5%), 2-propanol ((CH3)2CHOH, Merck, 99.9%), poly(vinylidene fluoride) (PVDF, kynar761, Arkema), lithium cobalt(III) oxide (LiCoO2, Sigma-Aldrich, 99.8%), cellulose acetate (CA, average Mn of 30000 g/mol, Sigma-Aldrich), poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG1000, average Mn of 1000 g/mol, Sigma-Aldrich), graphite (Sigma-Aldrich, > 99%), N-methyl pyrrolidone (NMP, Sigma-Aldrich, 99.5%) and carbon black (C, Sigma-Aldrich, 99.9%) were utilized as obtained.

Synthesis of Li7V15

Li7V15 (the formula is Li7[V15O36(CO3)]⋅39H2O, LVC) is prepared following the reported method35. 79.6 mmol Li2CO3 (5.88 g) was dissolved in 150 mL deionized water under stirring to gain a homogeneous solution. 65.9 mmol V2O5 (12 g) was gradually added to the mixture during stirring, and for an additional five minutes, the solution was stirred. The solution was heated to 90 °C in an Erlenmeyer flask after the residues were filtered out. Following the portion-wise addition of 11.5 mmol hydrazine sulfate (1.5 g) to the solution under stirring, the flask was heated to 90 °C for an hour. After filtering, the resulting greenish-black solution was cooled to 20 °C and shaken with 50 mL 2-propanol. Black crystals were formed when the solution was kept at 5–7 °C for 2 days, washed with 2-propanol, and dried out under vacuum at 50 oC 12 h.

Preparation of SPEs

The solution casting technique was employed to prepare SPEs. For the preparation of the CA-PEG1000-LiPF6 electrolyte, LiPF6 with the ratio of 16:1 (units of electron donor atoms/unit of LiPF6) was dissolved in DMSO under stirring for 2 h, and then 0.5 g PEG1000 was added to the solution. Finally, after dissolving the PEG1000, 0.5 g cellulose acetate powder was added. For the preparation of electrolytes containing LVC as lithium salt and inorganic filler, LVC powder with the same ratio of lithium salt was uniformly dissolved in DMSO under ultrasonic. Afterward, the same amounts of PEG1000 and cellulose acetate applied for the preparation of CA-PEG1000-LiPF6 were added to the solution under constant stirring for 1 h. The obtained slurries were transferred into Teflon plates and located in a vacuum oven for 24 h at 50 °C to evaporate the solvent.

Characterizations

XRD patterns were recorded on a Tongda TD-3700 diffractometer with Cu Kα radiation (λ = 1.54 Å). The FTIR was collected on a Bruker spectrometer. Raman measurement was performed on a UniDron-A Confocal Microscope Raman/PL Spectroscopy. A FE-SEM (MIRA3 FE-SEM) with an acceleration voltage of 10 kV was employed to consider the morphology of the polyoxovanadates. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was carried out under N2 flowing with a heating rate of 10 oC/min from room temperature to 800 oC. For estimation of glass transition temperature (Tg), Tm, and the percentage of crystallinity ( ) of SPEs, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed on NETZSCH DSC 200 F3, Bavaria.

) of SPEs, differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) was performed on NETZSCH DSC 200 F3, Bavaria.  could be obtained from the Eq. (2):

could be obtained from the Eq. (2):

|

1 |

and

and  (58.8, 196.8 J /g) denoted as the enthalpies of melting for the prepared samples and pure CA and PEG with a crystallinity of 100%, respectively36,37.

(58.8, 196.8 J /g) denoted as the enthalpies of melting for the prepared samples and pure CA and PEG with a crystallinity of 100%, respectively36,37.

Electrochemical measurements

The ionic conductivity was calculated via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) using the Radsat200 instrument. The prepared SPEs were cut into rounded pellets. Throughout the test, the pellet was located between two stainless-steel plates under an argon atmosphere to remove the effect of oxygen and water. The applied frequency range was 200 kHz–0.1 Hz, and the AC amplitude was 10 mV. The ionic conductivity was measured according to Eq. (2):

|

2 |

Rb (Ohm) stands for the electrolyte resistivity, L (cm) is the thickness of the pellet, and A (cm2 is the area of the pellet. For the calculation of the activation energies, EIS assessments at different temperatures were done, and through the Arrhenius formula, the values of activation energies were calculated.

For the LSV tests, a graphite electrode was used as the reference/counter electrodes, and a stainless-steel plate was applied as the working electrode, and CA-PEG1000-LiPF6 and CA-PEG1000-LVC (with a diameter of 9 mm) were exploited as polymer electrolytes. The LSV tests were conducted in the potential range of 1–6 V at a scan rate of 0.1 V/s on an electrochemical workstation Radsat200.

The transference number of lithium (t+) for the prepared SPEs was additionally determined through the potentiostatic polarization approach. Electrolytes were conducted with a constant voltage of 10 mV while packed in a Li/SPE/Li symmetric cell for this experiment. Transference number (t+) of SPEs was determined by combining chronoamperometry and EIS tests Via Eq. (3).

|

3 |

R0 and Rss are the initial and the steady-state resistance, and I0 and Iss are the initial and the steady-state currents, and ΔV represents the constant potential.

The GCD cycling tests (constant current) of LiCoO2/SPE/Gr cell were carried out at room temperature in the voltage range of 2–5 V at current rates of 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 C, by an electrochemical workstation Radsat200. The cathode comprised 80 wt. % LiCoO2, 5 wt. % PVDF, and 15 wt. % super-P carbon black. Anode was prepared by 80 wt. % graphite, 5 wt. % PVDF, and 15 wt. % super-P carbon black. All these materials were mixed with NMP as a solvent to prepare a slurry, which was coated on aluminum foil for cathode and Cu sheet for anode, and then dried in a vacuum oven at 80 °C for 24 h. All cell fabrications and electrochemical characterizations were performed in a glovebox under nitrogen. To prepare the cell, the SPE (CA-PEG1000-LVC) was packed between the cathode and anode. To analyze the stripping/plating of Li ions in the Lithium meta anode, a Li plating/stripping cyclic performance was studied. A protocol of 0.5 h stripping followed by 0.5 h plating with the current density of 0.3 mA cm−2 has been used over 100 h at room temperature. The electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) before and after the stripping/plating test was done with the applied frequency range of 200 kHz–0.1 Hz at the AC amplitude of 10 mV.

Results and discussion

Physiochemical characterizations

Figure 1 shows the intermolecular interaction between cellulose acetate and PEG1000, and the pathway of Li+ cations in SPEs. Since LVC is a heteropolyanion, with countercations of lithium, and in this system acted as a multi-ion salt, the suggested mechanism of cations’ transport in the polymer matrix is similar to other lithium salts. In this regard, ions coordinate with the e−-donor functional groups in the polymer matrix after dissociating from the counterions. The ions have the tendency to jump between coordinative sites, which are typically composed of more than 3 e−donor groups, when exposed to an electric field. Either an ion-cluster-assisting function or segmental motion of the polymer chains, in which the counterion is temporarily re-associated before being re-solvated by the donor groups in the polymer matrix, enhances this type of ion hopping. Therefore, in this system, like commonly accepted for PEO-based SPEs, ionic conduction mostly occurs in the amorphous area of the polymer medium, whereas very little ion motion is provided by the crystalline part38.

Fig. 1.

Schematic illustration of intermolecular interaction between CA and PEG and cations’ pathway in CA-PEG1000-LVC solid polymer electrolyte.

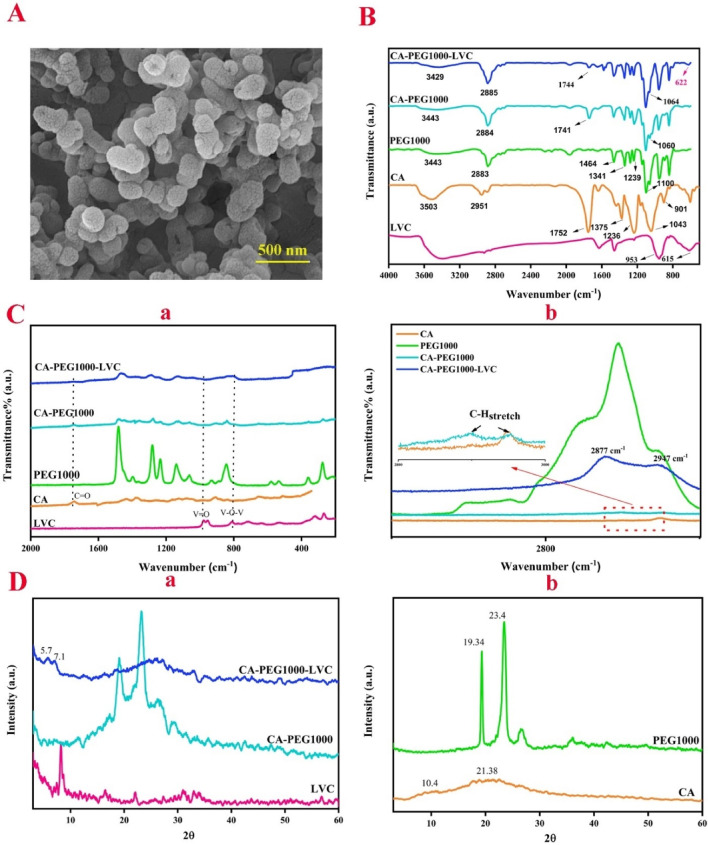

The microscopic morphology of LVC was observed by FE-SEM, as reflected in Fig. 2A, which shows that the synthesized polyoxovanadates have a semi-spherical morphology (mean size of particles 65–100 nm, Figure S1) and are composed of some tens of individual small clusters, as reported in previous studies30. Figure 2B illustrates the FT-IR spectra of LVC, pure cellulose acetate, PEG1000, CA/PEG1000, and CA/PEG1000/LVC. The peaks at 953 and 615 cm−1 correspond to V = O bending vibration and asymmetric bending vibration of V-O-V in polyoxovanadate, respectively39. The FTIR spectrum of pure CA displays several characteristic bands. The O-H stretching and C-H stretching vibrations are observed at 3503 and 2951 cm−1. The bands at 1640 and 1752 cm−1 are attributed to bonded and free carbonyl groups, respectively. The bands at 1436 and 1375 cm−1 are related to C-H bending and rocking modes. Additionally, the C-O-C stretching of acetate and C-OH stretching are detected at 1236 and 1043 cm−1, respectively. Lastly, the band at 901 cm−1 is assigned to the combination of C-O-C stretching and C-H rocking modes. Similarly, the FTIR spectrum of PEG1000 shows distinct bands corresponding to its functional groups. The O-H stretching vibration is observed at 3443 cm−1. The C-H stretching and bending modes are seen at 2883 and 1464 cm−1, respectively. The peak at 1646 cm−1 is attributed to the bending mode of C-OH40. The peaks at 1341, 1239, and 1100 cm−1 correspond to C-H bending vibration, C-H twisting vibration, and C-O stretching vibration, respectively41,42. The primary peaks of the pure CA are visible in the spectra of the CA-PEG1000 blends without new peaks. As can be observed, several peaks’ locations and intensities are different from their main position. Specifically, the interaction between the functional groups may cause some groups’ bands to move slightly to the higher or lower wavenumbers, known as blue and red shifts, respectively. The peaks of the bonded carbonyl and hydroxyl displaced to 1741 and 3444 cm−1, respectively, while the peak locations of 3503 and 1752 cm−1 of the pure CA relatively moved to the lower wavenumber in the CA-PEG1000, indicating the hydrogen bonding of the PEG’s O-H groups with the carbonyl group of CA. Also, the band at 1043 cm−1 in CA has been moved to the broadened peak at 1060 cm−1 owing to the hydrogen bonding between the C-O-H in CA and O-H in PEG40, as illustrated in Fig. 2B. By the addition of LVC, the peak at 622 cm−1 in the spectrum of CA-PEG1000-LVC is detected, which is attributed to the bending vibration of the V-O-V bond, confirming the successful loading of LVC nanoparticles in the polymer matrix. The change in the position of the peak is due to the varied electrostatic environment of POV anions43,44. Similar to the CA-PEG1000 spectrum, the location of some peaks of CA and PEG rarely shifts to higher and smaller wavenumbers due to the interaction between LVC and polymer chains45. A Raman spectrum contains bands triggered by inelastic scattering from chemically bonded structures, as demonstrated in Fig. 2C (a, b). The asymmetric stretching vibration of the C-O-C glycosidic linkage and C-H stretching contributed to the distinctive Raman bands for CA, which were detected at 2953 and 1129 cm−1, respectively. Furthermore, we detected the band linked to C-OH in the rings at 1262 cm−1 and the pyranose ring signal at 1076 cm−1. The acetyl group’s distinctive Raman signals are visible at 1745, 1433, and 1377 cm−1, which correspond to the carbonyl group’s vibration as well as the C-H asymmetric and symmetric vibrations that exist in the acetyl groups. The bands detected at 990, 904, 836, and 655 cm−1 can be related to C-O, C-H, O-H, and C-OH bonds46. Stretching vibrations of alkyl chains at 2947, 2893, and 2855 cm−1 are the most characteristic band positioning for PEG; we can observe that these vibration groups are stronger in the Raman spectra than in the IR spectra. The C-H group’s bending mode is attributed to the bands at 1481 and 1403 cm−1. The C-H twisting vibrations are represented by the bands at 1277 and 1234 cm−1. The stretching vibrations of C-O and C-O-H are located at 1066 and 1143 cm−1, respectively. The skeletal vibrations of PEG are attributed to the peaks at 842 and 880 cm−1. The C-C-O bending vibration is represented by the signals at 533 and 358 cm−1, whereas the PEG skeleton deformation mode is represented by the band at 218 cm[−147,48. The peak of the C = O stretching band is slightly shifted to the lower wavenumber when PEG is combined with CA (from 1745 to 1742 cm−1 after adding PEG). This behavior similar to the FTIR results, suggests that PEG and CA may interact, most likely through a hydrogen bonding interaction. The PEG/CA polymer blend structure is stabilized by this interaction. The presence of PEG and CA allows for the formation of several bands in the C-H stretching region, which spans around 3000–2700 cm−1. The bands in pure PEG are located at 2947, 2893, and 2855 cm−1. These bands are associated with PEG’s crystalline state. The pure CA shows a major band at 2953 cm−1 aligned to the amorphous state of CA. In the PEG/CA blend, a change in the Raman spectra occurs49, which shows a combination of PEG and CA’s peaks (Fig. 2C (b)). By adding LVC nanoparticles, two peaks at around 810 and 994 cm−1 appeared in CA-PEG1000-LVC which confirms the presence of polyoxovanadates32.

Fig. 2.

(A) FE-SEM image of LVC nanoparticles, (B) FT-IR and (C) Raman spectra, and (D) XRD patterns of LVC, CA, PEG1000, CA-PEG1000, CA-PEG1000-LVC.

Figure 2D (a, b) shows the XRD pattern of LVC, CA, PEG1000, CA-PEG1000, and CA-PEG1000-LVC. The XRD pattern of LVC nanoparticles is displayed in Fig. 2D (b), which is consistent with the pattern reported in previous studies, and no noticeable impurity phases were detected32. CA and PEG1000 exhibited peaks at 2θ = 10.4, 21.4, and 2θ = 19.3, 23.4, respectively. In contrast, the CA-PEG1000 sample demonstrates the major diffraction peaks at 2θ = 19.2, 23.4, corresponding to the PEG1000, which shifts to smaller angles due to the attendance of CA. Adding polyoxovanadate to the polymer matrix shows additional diffraction peaks at 2θ = 5.7 and 7.1, corresponding to LVC nanoparticles32. The diffraction peaks of PEG broadened and weakened when PEG1000 was mixed with the CA, indicating that the polymer’s crystallinity was reduced50. Following the addition of LVC, the matrix’s peak intensity further dropped in comparison to the CA-PEG1000 sample, confirming LVC’s crucial function in lowering the polymer blend’s crystallinity33. The crystallite size of polymers and composites was determined using the Scherrer equation 51:

|

4 |

K and θ are the diffraction angle and the Scherrer constant, β and λ are the FWHM and the wavelength of the X-radiation. Based on the achieved data, the crystallite sizes for CA, PEG1000, CA-PEG1000, and CA-PEG1000-LVC were calculated as 77.8, 295, 157.5, and 95.6, respectively.

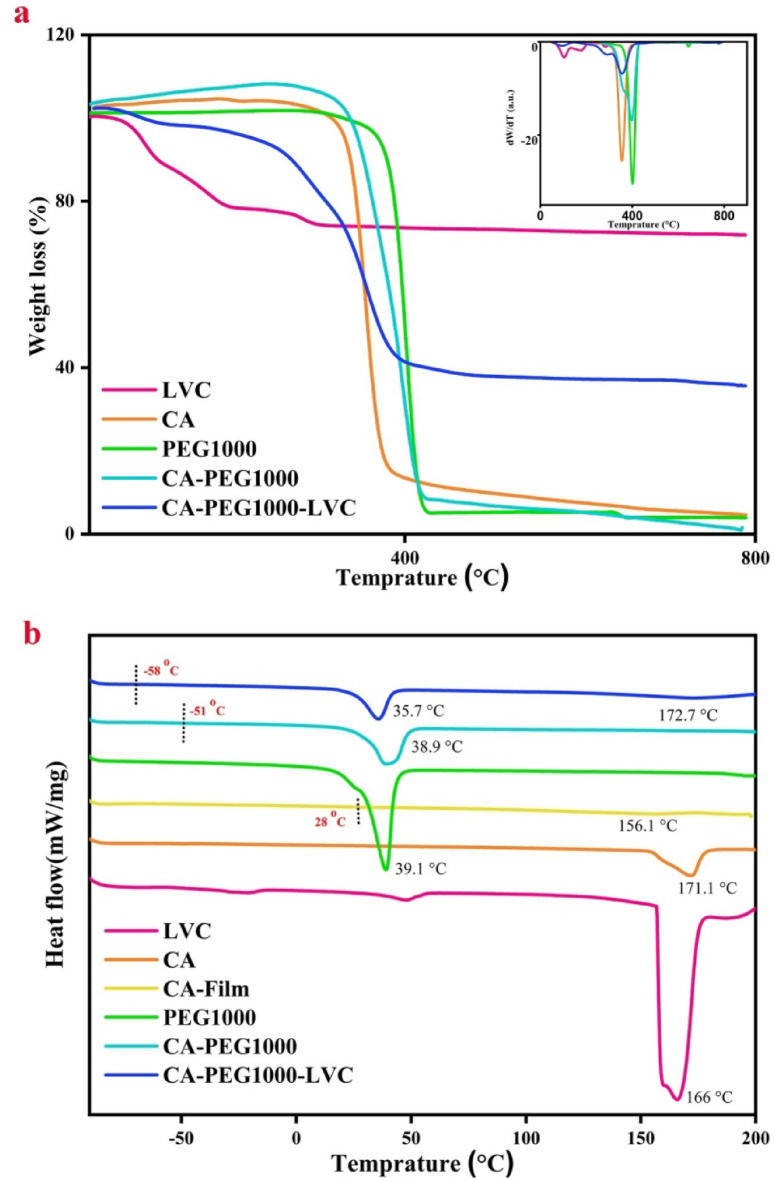

The one-step thermal degradation of CA demonstrates a maximum degradation rate at 355.4 °C as revealed in Fig. 3a. After blending of CA with PEG1000, the obtained blend displayed two-step degradation at temperatures 358.3–377.8 °C and 398.6 °C related to CA and PEG1000, respectively52. Additionally, the ratio of Cell-PEG1000 residue to neat CA was altered from 4.6 to 1.5%. In Fig. 3a, the thermograms of CA-PEG1000-LVC (TGA and derivative thermogravimetry (DTG)) are shown. Consequences exhibited that after adding LVC, three stages of degradation were observed. Degradation at 356.7 °C is correlated to CA, and the other one at 291.9 °C is related to LVC33.

Fig. 3.

(a) TGA and DTG curves, and (b) DSC curves of LVC, CA, PEG1000, CA-PEG1000, CA-PEG1000-LVC.

The thermal properties of the samples are presented in Table 1. Based on the DSC analysis of samples (Fig. 3b), by the addition of PEG1000 and LVC, Tm moved from 39.1 to 35.7 °C, and the area peak of melting also reduced meaningfully. In accordance with the XRD data, this proposes that the polymer chains were more plasticized and crystallinity was reduced. These modifications are explained by the critical roles that PEG1000 and LVC nanoparticles play in developing amorphous areas and boosting polymer chain mobility33. The pure PEG1000, due to the high crystallinity, does not show Tg; however, in CA-PEG1000 and CA-PEG1000-LVC samples, due to the decreasing in crystallinity of polymer blends, it appears at −51 and − 58 °C. The Tg correlated to CA was not detected in the blend forms, which might be owing to the high scanning rate. Additionally, the melting peak’s area dropped with the addition of nanoparticles, indicating a notable drop in crystallinity; for CA-PEG1000-LVC, this was 25.1%. The chain of polymer achieved more flexibility and more free volume for segmented motion due to the expansion of the amorphous area, which improved the ion transport capabilities. The DSC findings showed that the significant decrease in Tg and χc% helped to increase Li+-transportation capability of this type of composite PEs with polyoxovanadates33.

Table 1.

Thermal properties of CA, PEG, LVC, and composite PEs.

| Sample | Td,5% (oC) |

Td, LVC (oC) |

Td, CA (oC) |

Td, PEG1000 (oC) |

Ash (%) |

Tmelting, CA (°C) |

Tmelting, PEG1000 (°C) |

Tg (°C) |

(%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CA | 331.7 | - | 355.4 | - | 4.6 | 171.1 (powder), 156.1 (film) | - | 28 |

98.1 (powder) 14.7 (film) |

| PEG1000 | 369.9 | - | - | 401.8 | 3.9 | - | 39.1 | - | 83.2 |

| CA-PEG1000 | 346.5 | - | 358–377.8 | 398.6 | 1.5 | - | 38.9 | −51 (PEG) | 40.8 |

| CA-PEG1000-LVC | 228.3 | 101.1, 291.9 | 356.7 | - | 35.6 | 172.7 | 35.7 | −58 (PEG) | 25.1 |

Electrochemical behaviors of SPEs

A significant aspect in determining whether SPE films are appropriate for LIBs is ionic conductivity. In this regard, the Nyquist and Bode plots of the produced SPEs are shown in Fig. 4 (a, b). The EIS curves show the imaginary impedance (Z″) as a function of the real impedance (Z′), whereas the Bode plot illustrates the phase angle and impedance magnitude as a function of frequency. Using the ZSimpWin software, the resulting Nyquist curves were thoroughly examined and adjusted with equivalent electrical circuit53,54. Important electrochemical factors, including interface information, diffusion processes, capacitance, and resistance, could be figured out by examining the impedance spectrum. The polymer bulk resistance is represented by the first resistance (Rb) in the equivalent circuit depicted in Fig. 4a. The terms Qint, Rint, and W stand for the interface capacitance, the electrolyte/electrode interface resistance, and Li+ penetration into the electrode denoted as Warburg impedance (W), respectively51. Equation (2) and the data from the equivalent circuit were used to determine the ionic conductivity values of SPEs. Because PEG structures contain electron donor groups, the presence of PEG1000 in the CA-PEG1000 electrolyte improved ionic conductivity. As a result, the existence of extra oxygen atoms greatly accelerated the Li salt dissociation in the electrolyte and improved its transference within the SPEs. Additionally, PEG has a very low Tg, which causes greater segmental movements. The host polymer’s notable segmental motion produced more free volume, which facilitated the transference of lithium cations across the electrolytes. In the CA-PEG1000-LVC electrolyte, by employing LVC nanoparticles as lithium salt and inorganic filler, the conductivity of the prepared electrolyte increased from 8.2 × 10−5 S cm−1 in the presence of LiPF6 to 4.1 × 10−4 S cm−1 at room temperature (Table 2). The enhancement of the conductivity might be related to the larger quantity of terminal oxygen atoms (Lewis base sites) and LVC counteractions, leading to additional sites for ion transport. Furthermore, LVC nanoparticles decrease the crystallinity of SPEs, which is a crucial factor for easing segmental motions in polymers32,33. Also, the effect of different molar ratios of LVC nanoparticles (1:8 and 1:24) on the ionic conductivity was considered via EIS test (Figure S2 and Table S1). Results showed that by increasing the LVC content, ionic cinductivity increased.

Fig. 4.

(a) Nyquist and (b) Bode plots of SS/SPEs/SS at RT.

Table 2.

The electrochemical properties of SPEs.

| Sample name | Day | Rint(Ω) | σ (S cm−1) |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA-PEG1000-LiPF6 | 1 | 8.0 × 104 | 8.2 × 10−5 |

| 3 | 7.7 × 104 | 5.7 × 10−5 | |

| 7 | 6.4 × 104 | 4.8 × 10−5 | |

| 10 | 1.1 × 105 | 4.6 × 10−5 | |

| CA-PEG1000-LVC | 1 | 1.3 × 105 | 4.1 × 10−4 |

| 3 | 2.2 × 105 | 1.1 × 10−4 | |

| 7 | 4.2 × 105 | 8.8 × 10−5 | |

| 10 | 3.1 × 105 | 7.6 × 10−5 |

The behavior of the prepared electrolytes with increasing temperature from RT to 65 oC is illustrated in Fig. 5 (a, b, c). The trend is in accordance with the Arrhenius model, which is stated by Eq. (5)55.

|

5 |

Fig. 5.

(a, b) EIS results at temperatures ranging from 25 to 65 °C for CA-PEG1000-LiPF6 and CA-PEG1000-LVC, respectively (c) Temperature-dependent manner via the Arrhenius model for CA-PEG1000-LiPF6 and CA-PEG1000-LVC.

Where Ea represents the activation energy, kB denotes the Boltzmann constant, T stands for the temperature, and σ0 is the preexponential factor. Figure 5c also reports the squared error (R2 and activation energy from the Arrhenius model. Figure 5a and b show EIS curves of SPEs at 25–65 °C. The consideration of temperature effects on SPEs’ ionic conductivity revealed that by increasing the temperature, an increase in ion conductivity is detected. This is explained by the polymer chains’ segmental mobility and the rise in mobile carrier ions. The development of these characteristics 3, 7, and 10 days after the initial EIS test for SPEs, is also shown in Figs. 6a, b, and c. According to the results (Table 2), the conductivity of SPEs showed a decline 10 days after the initial EIS test, which shows the ability of the polymer structure to stabilize the Li+ is slightly decreased after 10 days and could prevent the reaction of Li+ with other charged species (PF6− and anions of polyoxovanadate). The resistance of the electrode/electrolyte interface (Rin) in CA-PEG1000-LiPF6 increases after 10 days; however, the trend of interface resistance decreases during 7 days, confirming good compatibility with electrodes. In CA-PEG1000-LVC, the compatibility is enhanced after 7 days, and an upward trend was seen for one week. The above results indicated that the prepared SPEs could provide an acceptable interface to attain decent connection between the electrolytes and electrodes.

Fig. 6.

(a, b) EIS results and (c) ionic conductivity curves of CA-PEG1000-LiPF6 and CA-PEG1000-LVC after 1, 3,7, and 10 days.

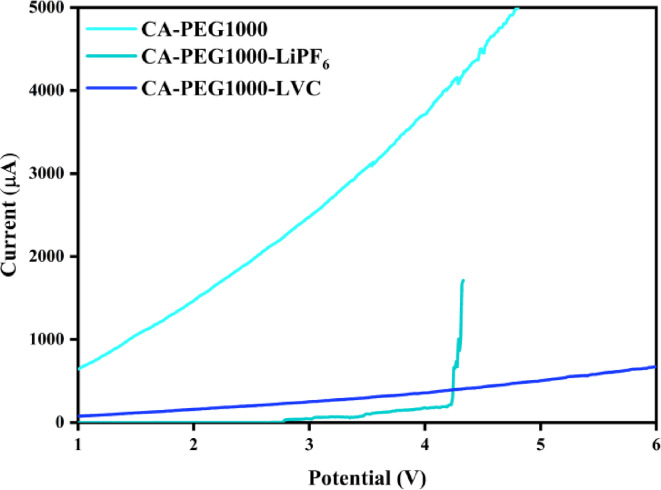

Another crucial characteristic of electrolytes is their electrochemical stability. Generally, the electrolyte should have a chemical potential that prevents it from taking part in the redox process occurring in the cell and be electrochemically stable. To separate the lithium-ion from the cathodes, a voltage between 3 and 3.8 V is required51. So, the desired electrolytes for practical applications must possess a stable structure at the mentioned voltage. On the other hand, for polymer electrolytes, an electrochemical stability range greater than 4 Volts is preferred. Undoubtedly, the capacity to apply a greater potential variation to conduct redox processes on both electrodes (anode and cathode) is made possible by electrochemical steadiness at a higher potential. As a result, lithium-ion charging and transport capacity rise. The electrochemical stability of electrolytes was examined using the LSV test, as the results are shown in Fig. 7. SPEs have an electrochemical steadiness window greater than 4 Volts. Between the potential range of 1 and 6 V, at 4.2 V, a current response was detected for CA-PEG1000-LiPF6, but no current response was seen for blend polymer (CA-PEG1000) and CA-PEG1000-LVC, suggesting that no electrochemical reaction took place. The Lewis acid–base interactions between the polymer chains and the LVC nanoparticles can alter the chemical environment of the polymer matrix, consistent with the results obtained from FT-IR and RAMAN analyses, accordingly enhancing the anti-oxidative steadiness of the polymer matrix and overwhelming the oxidation breakdown of the polymer matrix at a high voltage56. Consequently, the electrochemical stability factor of both SPEs falls within the required range for LIBs.

Fig. 7.

LSV curves of SS/SPEs/Gr cells.

The transference number of lithium-ion (t+) plays a crucial role in rechargeable LIBs. Figure 7 (a, b) shows the AC impedance spectra and DC polarization curves of SPEs at room temperature. Table S2 provides the data of final and initial current (ISS, I0), in addition to resistance values (R0, RSS) for these measurements. Based on Eq. (3), the t+ of the synthesized electrolytes was measured 0.47 for CA-PEG1000-LiPF6 and 0.59 for CA-PEG1000-LVC. A high transfer number value indicates that the gradient of ion concentration at the interface of the electrolyte with the electrode was decreased, reflecting the high stability of the SPEs. This result highlights the favorable compatibility of the synthesized electrolytes with the electrode. Also, the functional groups of poly(ethylene glycol) provide more locations for Li cations coordination, enabling their transportation inside the electrolyte, leading to more effective migration of ions and consequently an improved t58.

Fig. 8.

Chronoamperometry and Nyquist curves before and after polarization of (a) Li/CA-PEG1000-LiPF6/Li, (b)/Li/CA-PEG1000-LVC/Li.

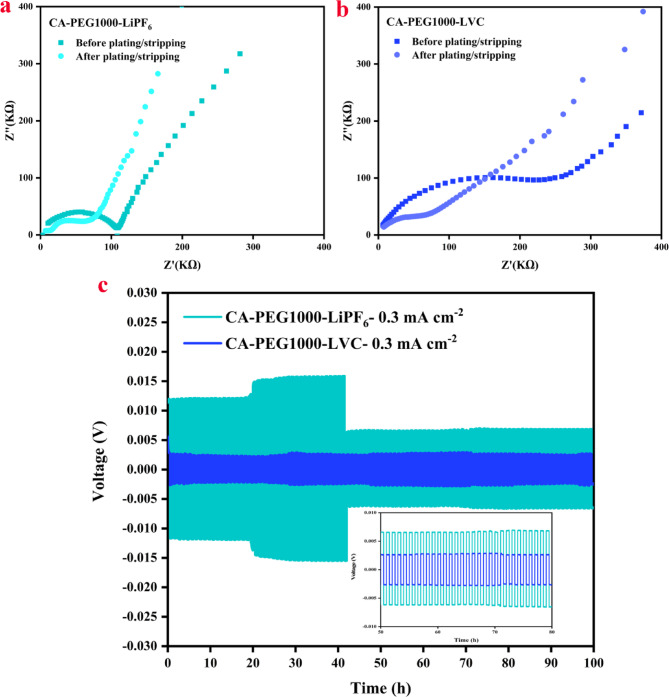

For evaluation of the compatibility between the polymer electrolytes and Li metal anode, the stripping/plating test of lithium symmetrical cells was conducted. In this regard, the interfacial resistance of SPEs with Li electrode was studied via EIS before and after Li plating/stripping cyclic performance. The Li|CA-PEG1000-LVC |Li symmetric cell showed relatively lower interfacial resistance of about 1.9 × 105 Ω before cyclic test at room temperature in comparison to CA-PEG1000-LiPF6 (2.7 × 105 Ω). After a 100-hour cycling test, the interfacial resistance is decreased to 1.18 × 105 and 1.25 × 105 Ω for CA-PEG1000-LVC and CA-PEG1000-LiPF6, respectively. Such behavior, which suggests the suppression of lithium dendrites and uniform lithium deposition, may be correlated to the enhanced interface compatibility over an extended period of cycling (Fig. 9a, b)59. According to the galvanostatic cycling test (Fig. 9c), the cell with the SPEs could remain stable with no short-circuiting under a current density of 0.3 mA cm−2. The Li|CA-PEG1000-LVC|Li cell gave a minimum polarization voltage (∼4 mV) compared to the CA-PEG1000-LiPF6. This suggests that LVC nanoparticles induce slight resistance to the battery and a lower Li transport barrier at the CA-PEG1000-LVC/Li interface, which contributes to the uniform distribution of Li+. These consequences clarify that such a composite electrolyte is comparatively capable of controlling Li deposition and overwhelming the growth of lithium dendrites.

Fig. 9.

(a, b) EIS before and after plating/stripping, (c) Voltage profiles of symmetric cell of Li|SPEs|Li at RT. The inset in (c) displays enlarged voltage profiles from the 50–80 h.

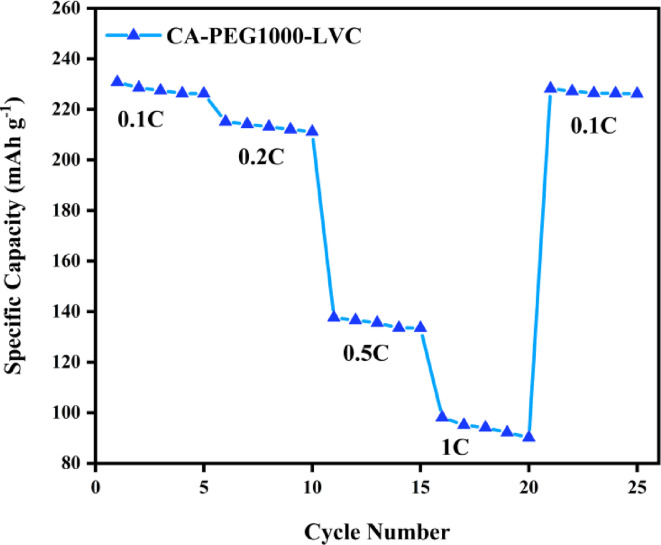

LiCoO2//Gr full cells were assembled to test the performance of CA-PEG1000-LVC for Li ion batteries. As depicted in Fig. 10, when the C-rates were 0.1, 0.2, 0.5, and 1 C, the LiCoO2/SPE with LVC/Gr cell showed specific capacities of 226.2, 211.1, 133.5, and 90.2 mAh/g, respectively. As C-rate decreased from 1 to 0.1 C, the discharge capacity quickly raised to 226.2 mAh/g, representing the cell’s good reversibility and cycleability.

Fig. 10.

Rate performance of LiCoO2/CA-PEG1000-LVC/Gr.

In comparison with the previous studies, the obtained data confirm that the CA-PEG1000-LVC electrolyte could be a good candidate for lithium-based batteries. In Table 3, the ionic conductivity and χc% of the prepared SPEs in this study with currently reported SPEs are compared.

Table 3.

Comparison of the ionic conductivity among CA-PEG1000-LVC and other polymer-based SPEs.

| Materials | Ionic conductivity (S cm−1) |

% % |

Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|

| CA-PEG1000-LiPF6 | 8.2 × 10−5 | 40.8 | This work |

| CA-PEG1000-LVC | 4.1 × 10−4 | 25.1 | This work |

| PVDF/CA- LiTFSI-LATP | 4.9 × 10−4 | 24.1 | 60 |

| Cellulose/PEO-LiTFSI-LAGP | 2.7 × 10−5 | - | 61 |

| PEO-LiTFSI-LLTO | 1.6 × 10−4 | - | 62 |

| PEO/PVDF-LiTFSI-LLZO | 4.2 × 10−5 | 61 | 63 |

| PVDF-HFP/CAP- LiTFSI | 1.2 × 10−4 | - | 64 |

| Cell/g-m-PEG/Pyr14 TFSI/LiTFSI | 1.0 × 10−5 | 38 | 65 |

| PVDF-HFP/CA-LiTFSI | 4.33 × 10−4 | - | 66 |

|

MOF (Zr-BPDC-2SO3 H) grown on bacterial cellulose-LiTFSI |

7.9 × 10−4 | - | 67 |

| Cellulose-Al2 O3 - LiTFSI | 2.0 × 10−4 | - | 68 |

| Cellulose-SiO2 - LiTFSI | 4.1 × 10−4 | - | 69 |

Conclusions

In this work, cellulose acetate-PEG1000-based SPEs were fabricated by a solution casting approach, and the role of Li7[V15O36(CO3)] (LVC) nanoparticles as inorganic filler and lithium salt was investigated. By adding LVC, the prepared electrolyte showed good ionic conductivity in the order of 10−4 S cm−1 at room temperature. LVC can establish effective ion transport routes because of its terminal oxygen atoms (Lewis base sites) and a large number of highly mobile working ions. Interestingly, because PEG1000 owns further electron-donor functional groups and likewise functions as a plasticizer agent, it increased the movement of ions inside the polymer medium, which in turn enhanced the ionic conductivity of SPEs. Additionally, PEG1000 has strong film-forming qualities and is a flexible polymer. This aids in the creation of flexible films when mixed with cellulose acetate. Because these films are readily formed, they may be used with various device designs. Moreover, compared to the routine CA-PEG1000-LiPF6 electrolyte, the SPE with LVC had a broader electrochemical voltage window of more than 5 V. The excellent performance of LVC as lithium salt and inorganic filler and its role in reducing the crystallinity of polymers and providing mobile cations in polymer matrix, this research could pave the way for the development of LVC as lithium salt and also polyoxometalates as inorganic fillers for designing new SPEs with high performance for next-generation lithium-based batteries.

Electronic Supplementary Material

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Author contributions

Elmira Kohan: Methodology, Formal analysis, Investigation, Writing - Original Draft, Visualization., Roushan Khoshnavazi: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision. Mir Ghasem Hosseini: Formal analysis, Investigation, Visualization. Abdollah Salimi: Validation, Resources. Mehdi Salami-Kalajahi: Conceptualization, Validation, Resources, Data Curation, Writing - Review & Editing, Supervision, Project administration, Funding acquisition.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Data availability

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the data form part of an ongoing study but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Roushan Khoshnavazi, Email: r.khoshnavazi@uok.ac.ir.

Mehdi Salami-Kalajahi, Email: m.salami@sut.ac.ir.

References

- 1.Golshan, M. & Salami-Kalajahi, M. Unraveling Chromism-induced marvels in energy storage systems. Prog. Mater. Sci.148, 101374. 10.1016/j.pmatsci.2024.101374 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 2.Li, F. et al. High-performance lithium metal anode enhanced by multifunctional film of PAN@AgNWs with antimicrobial activity. Electrochim. Acta. 493, 144444. 10.1016/j.electacta.2024.144444 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kohan, E., Khoshnavazi, R., Hosseini, M., Salimi, A. & Salami-Kalajahi, M. A review on instability factors of mono- and divalent metal ion batteries: from fundamentals to approaches. J. Mater. Chem. A. 12, 30190–30248. 10.1039/D4TA05386A (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 4.Oroujpour, M. & Salami-Kalajahi, M. Recent progress in application of polymers in potassium–sulfur batteries. J. Energy Storage. 112, 115590. 10.1016/j.est.2025.115590 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu, H. et al. Ti3C2Tx MXene enhanced high-performance LiFePO4 cathode for all-solid-state lithium battery. J. Mater. Sci. Technol.223, 104–113. 10.1016/j.jmst.2024.12.005 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu, J. et al. Lithophilic alloy and 3D grid structure synergistically reinforce dendrite-free Li–Sn/Cu anode for ultra-long cycle life lithium metal battery. Rare Met.10.1007/s12598-024-03102-z (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ye, T., Li, L. & Zhang, Y. Recent progress in solid electrolytes for energy storage devices. Adv. Funct. Mater.30, 2000077. 10.1002/adfm.202000077 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Armand, M. et al. Lithium-ion batteries – Current state of the Art and anticipated developments. J. Power Sources. 479, 228708. 10.1016/j.jpowsour.2020.228708 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 9.Choo, Y., Halat, D. M., Villaluenga, I., Timachova, K. & Balsara, N. P. Diffusion and migration in polymer electrolytes. Prog. Polym. Sci.103, 101220. 10.1016/j.progpolymsci.2020.101220 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 10.Li, M., Wang, C., Chen, Z., Xu, K. & Lu, J. New concepts in electrolytes. Chem. Rev.120, 6783–6819. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.9b00531 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Fan, X. et al. Opportunities of flexible and portable electrochemical devices for energy storage: expanding the spotlight onto Semi-solid/Solid electrolytes. Chem. Rev.122, 17155–17239. 10.1021/acs.chemrev.2c00196 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gerdroodbar, A. E. et al. A review on ion transport pathways and coordination chemistry between ions and electrolytes in energy storage devices. J. Energy Storage. 74, 109311. 10.1016/j.est.2023.109311 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 13.Jagan, M. & Vijayachamundeeswari, S. P. A comprehensive investigation of Lithium-based polymer electrolytes. J. Polym. Res.30, 250. 10.1007/s10965-023-03623-8 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 14.Enayati-Gerdroodbar, A., Eliseeva, S. N. & Salami-Kalajahi, M. A review on the effect of nanoparticles/matrix interactions on the battery performance of composite polymer electrolytes. J. Energy Storage. 68, 107836. 10.1016/j.est.2023.107836 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 15.Tan, X. et al. Preparation of nanocomposite polymer electrolyte via in situ synthesis of SiO2 nanoparticles in PEO. Nanomaterials10, 157. 10.3390/nano10010157 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wilson, M. K. et al. Solid electrolyte membranes with Al2O3 nanofiller for fully solid-state Li-ion cells. Polym. Bull.81, 6003–6024. 10.1007/s00289-023-04945-9 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sasikumar, M. et al. Titanium dioxide nano-ceramic filler in solid polymer electrolytes: strategy towards suppressed dendrite formation and enhanced electrochemical performance for safe lithium ion batteries. J. Alloys Compd.882, 160709. 10.1016/j.jallcom.2021.160709 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wang, J. et al. Highly conductive thin composite solid electrolyte with vertical Li7La3Zr2O12 sheet arrays for high-energy-density all-solid-state lithium battery. Chem. Eng. J.450, 137994. 10.1016/j.cej.2022.137994 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 19.Guo, B. et al. Enhanced electrochemical performance of PEO/Li6.4Ga0.2La3Zr2O12 composite polymer electrolytes. Ionics30, 3915–3924. 10.1007/s11581-024-05589-z (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo, Q. et al. 20 µm-thick Li6. 4La3Zr1. 4Ta0. 6O12-based flexible solid electrolytes for all-solid-state lithium batteries. Energy Material Advances 2022, 9753506, (2022). 10.34133/2022/9753506

- 21.Xu, H. et al. Synergistic effect of Ti3C2Tx MXene/PAN nanofiber and LLZTO particles on high-performance PEO-based solid electrolyte for lithium metal battery. J. Colloid Interface Sci.668, 634–645. 10.1016/j.jcis.2024.04.201 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Huang, Z. X., Zhang, T., Zhang, Z. P., Rong, M. Z. & Zhang, M. Q. Highly ionic conductive, Self-Healing, Li10GeP2S12-Filled composite solid electrolytes based on reversibly interlocked macromolecule networks for Lithium metal batteries with improved cycling stability. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 16, 42736–42747. 10.1021/acsami.4c09099 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wang, L. et al. Bifunctional lithium-montmorillonite enabling solid electrolyte with superhigh ionic conductivity for high-performanced lithium metal batteries. Energy Storage Mater.63, 102961. 10.1016/j.ensm.2023.102961 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 24.Liu, R. L. et al. Proton conductive polyoxometalates. Coord. Chem. Rev.522, 216224. 10.1016/j.ccr.2024.216224 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yang, L. et al. The intrinsic charge carrier behaviors and applications of polyoxometalate clusters based materials. Adv. Mater.33, 2005019. 10.1002/adma.202005019 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Teymouri, N., Khoshnavazi, R., Molaei, S. & Ghadermazi, N. Keggin Trimetallo-POM@MIL-101(Cr), synthesis, characterization and catalytic applications. Catal. Lett.155, 61. 10.1007/s10562-024-04885-7 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Aureliano, M. et al. Polyoxovanadates with emerging biomedical activities. Coord. Chem. Rev.447, 214143. 10.1016/j.ccr.2021.214143 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng, D., Li, K., Zang, H. & Chen, J. Recent advances on Polyoxometalate-Based Ion-Conducting electrolytes for Energy-Related devices. Energy Environ. Mater.6, e12341. 10.1002/eem2.12341 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiao, H. et al. Polyoxovanadate Li7[V15O36(CO3)] and its derivative γ-LiV2O5 as superior performance cathode materials for aqueous zinc-ion batteries. Chem. Eng. J.489, 151312. 10.1016/j.cej.2024.151312 (2024). [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chen, J. J. et al. Design and performance of rechargeable sodium ion batteries, and symmetrical Li-Ion batteries with Supercapacitor-Like power density based upon polyoxovanadates. Adv. Energy Mater.8, 1701021. 10.1002/aenm.201701021 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 31.Zhang, M. et al. Polyoxovanadate-polymer hybrid electrolyte in solid state batteries. Energy Storage Mater.29, 172–181. 10.1016/j.ensm.2020.04.017 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 32.Yuan, X. et al. A polyoxometalate-based polymer electrolyte with an improved electrode interface and ion conductivity for high-safety all-solid-state batteries. J. Mater. Chem. A. 7, 15924–15932. 10.1039/C9TA04714J (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yang, X. et al. The critical role of fillers in composite polymer electrolytes for lithium battery. Nano-Micro Lett.15, 74. 10.1007/s40820-023-01051-3 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Müller, A., Penk, M., Rohlfing, R., Krickemeyer, E. & Döring, J. Topologically interesting cages for negative ions with extremely high coordination number: an unusual property of V-O clusters. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed.29, 926–927. 10.1002/anie.199009261 (1990). [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fornazier, M. et al. Additives incorporated in cellulose acetate membranes to improve its performance as a barrier in periodontal treatment. Front. Dent. Med.2, 776887. 10.3389/fdmed.2021.776887 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 36.Sheik, M. A., Aravindan, M. K., Beemkumar, N., Chaurasiya, P. K. & Dhanraj, J. A. Enhancement of heat transfer in PEG 1000 using Nano-Phase change material for thermal energy storage. Arab. J. Sci. Eng.47, 15899–15913. 10.1007/s13369-022-06810-9 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhou, D., Shanmukaraj, D., Tkacheva, A., Armand, M. & Wang, G. Polymer electrolytes for Lithium-Based batteries: advances and prospects. Chem5, 2326–2352. 10.1016/j.chempr.2019.05.009 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 38.Chen, J. J. et al. High-performance Polyoxometalate‐based cathode materials for rechargeable lithium‐ion batteries. Adv. Mater.27, 4649–4654. 10.1002/adma.201501088 (2015). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Doosti, M. & Abedini, R. Polyethyleneglycol-Modified cellulose acetate membrane for efficient olefin/paraffin separation. Energy Fuels. 36, 10082–10095. 10.1021/acs.energyfuels.2c01768 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 40.Fahmy, H. M. & Amr, A. Synthesis of castor oil/peg as textile softener. Sci. Rep.14, 7208. 10.1038/s41598-024-56917-2 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.León, A. et al. FTIR and Raman characterization of TiO2 nanoparticles coated with polyethylene glycol as carrier for 2-Methoxyestradiol. Appl. Sci.7, 49. 10.3390/app7010049 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 42.Wang, G. et al. Nanostructured polymer composite electrolytes with Self-Assembled polyoxometalate networks for proton conduction. CCS Chem.4, 151–161. 10.31635/ccschem.021.202000608 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 43.Zheng, Z. et al. Polyoxometalate-Poly(Ethylene Oxide) nanocomposites for flexible anhydrous Solid-State proton conductors. ACS Appl. Nano Mater.4, 811–819. 10.1021/acsanm.0c03141 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Guo, H. et al. Multifunctional enhancement of Proton-Conductive, stretchable, and adhesive performance in hybrid polymer electrolytes by polyoxometalate nanoclusters. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 13, 30039–30050. 10.1021/acsami.1c06848 (2021). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Kubota, H., Sakamoto, K. & Matsui, T. A confocal Raman microscopic visualization of small penetrants in cellulose acetate using a deuterium-labeling technique. Sci. Rep.10, 16426. 10.1038/s41598-020-73464-8 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kuzmin, V. et al. Raman spectra of polyethylene glycols: comparative experimental and DFT study. J. Mol. Struct.1217, 128331. 10.1016/j.molstruc.2020.128331 (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yamini, D., Devanand Venkatasubbu, G., Kumar, J. & Ramakrishnan, V. Raman scattering studies on PEG functionalized hydroxyapatite nanoparticles. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc.117, 299–303. 10.1016/j.saa.2013.07.064 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Marlina, D., Novita, M., Anwar, M. T., Kusumo, H. & Sato, H. Raman spectra of polyethylene glycol/cellulose acetate butyrate biopolymer blend. Journal of Physics: Conference Series 1869, 012006, (2021). 10.1088/1742-6596/1869/1/012006

- 49.Sundararajan, S., Samui, A. B. & Kulkarni, P. S. Shape-stabilized poly(ethylene glycol) (PEG)-cellulose acetate blend Preparation with superior PEG loading via microwave-assisted blending. Sol. Energy. 144, 32–39. 10.1016/j.solener.2016.12.056 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 50.Safavi-Mirmahalleh, S. A. & Salami-Kalajahi, M. Application of cellulose-polyaniline blends as electrolytes of lithium-ion battery. Adv. Energy Sustain. Res.XX, 2500021. 10.1002/aesr.202500021 (2025). [Google Scholar]

- 51.Zhang, H. et al. Polyethylene glycol-grafted cellulose-based gel polymer electrolyte for long-life Li-ion batteries. Appl. Surf. Sci.593, 153411. 10.1016/j.apsusc.2022.153411 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 52.Lazanas, A. C. & Prodromidis, M. I. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy a tutorial. ACS Meas. Sci. Au. 3, 162–193. 10.1021/acsmeasuresciau.2c00070 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Faris, B. K. et al. Impedance, electrical equivalent circuit (EEC) modeling, structural (FTIR and XRD), dielectric, and electric Modulus study of MC-Based Ion-Conducting solid polymer electrolytes. Mater. (Basel). 1510.3390/ma15010170 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 54.Bradford, G. et al. Chemistry-informed machine learning for polymer electrolyte discovery. ACS Cent. Sci.9, 206–216. 10.1021/acscentsci.2c01123 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Fan, P. et al. High performance composite polymer electrolytes for Lithium-Ion batteries. Adv. Funct. Mater.31, 2101380. 10.1002/adfm.202101380 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 56.He, X. et al. Anion concentration Gradient-Assisted construction of a Solid–Electrolyte interphase for a stable zinc metal anode at high rates. J. Am. Chem. Soc.144, 11168–11177. 10.1021/jacs.2c01815 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Hoffknecht, J. P. et al. Coordinating anions to the rescue of the Lithium ion mobility in ternary solid polymer electrolytes plasticized with ionic liquids. Adv. Energy Mater.13, 2202789. 10.1002/aenm.202202789 (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 58.Yao, M., Ruan, Q., Yu, T., Zhang, H. & Zhang, S. Solid polymer electrolyte with in-situ generated fast Li + conducting network enable high voltage and dendrite-free lithium metal battery. Energy Storage Mater.44, 93–103. 10.1016/j.ensm.2021.10.009 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 59.Liang, H. et al. Stabilizing the interface of PEO solid electrolyte to lithium metal anode via a g-C3N4 mediator. Chem. Commun.58, 10821–10824. 10.1039/D2CC03310K (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Chao, S. C., Kuo, Y. S., Chen, P. X. & Liu, Y. H. Solution-processed Poly (vinylidene difluoride)/cellulose acetate/Li1 + xAlxTi2-x (PO4) 3 composite solid electrolyte for improving electrochemical performance of solid-state lithium-ion batteries at room temperature. J. Colloid Interface Sci.674, 306–314. 10.1016/j.jcis.2024.06.108 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Wang, C. et al. Three-Dimensional-Percolated ceramic nanoparticles along Natural-Cellulose-Derived hierarchical networks for high Li + Conductivity and mechanical strength. Nano Lett.20, 7397–7404. 10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c02721 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Liu, K., Zhang, R., Sun, J., Wu, M. & Zhao, T. Polyoxyethylene (PEO)|PEO–Perovskite|PEO composite electrolyte for All-Solid-State Lithium metal batteries. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces. 11, 46930–46937. 10.1021/acsami.9b16936 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Li, J. et al. A promising composite solid electrolyte incorporating LLZO into PEO/PVDF matrix for all-solid-state lithium-ion batteries. Ionics26, 1101–1108. 10.1007/s11581-019-03320-x (2020). [Google Scholar]

- 64.Gao, C. et al. Cellulose acetate propionate incorporated PVDF-HFP based polymer electrolyte membrane for lithium batteries. Compos. Commun.33, 101226. 10.1016/j.coco.2022.101226 (2022). [Google Scholar]

- 65.Nematdoust, S., Najjar, R., Bresser, D. & Passerini, S. Partially oxidized cellulose grafted with polyethylene glycol mono-Methyl ether (m-PEG) as electrolyte material for Lithium polymer battery. Carbohydr. Polym.240, 116339. 10.1016/j.carbpol.2020.116339 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ma, Q. et al. Cellulose acetate-promoted polymer-in-salt electrolytes for solid-state lithium batteries. J. Solid State Electrochem.27, 1411–1421. 10.1007/s10008-023-05414-z (2023). [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zeng, Q. et al. Cross-Linked chains of Metal–Organic framework afford continuous ion transport in solid batteries. ACS Energy Lett.6, 2434–2441. 10.1021/acsenergylett.1c00583 (2021). [Google Scholar]

- 68.Chiappone, A., Nair, J. R., Gerbaldi, C., Bongiovanni, R. & Zeno, E. UV-cured Al2O3-laden cellulose reinforced polymer electrolyte membranes for Li-based batteries. Electrochim. Acta. 153, 97–105. 10.1016/j.electacta.2014.11.141 (2015). [Google Scholar]

- 69.Li, H. et al. -i. Integrated composite polymer electrolyte cross-linked with SiO2-reinforced layer for enhanced Li-ion conductivity and lithium dendrite Inhibition. ACS Appl. Energy Mater.3, 8552–8561 (2020). https://slink.access.semantak.com/go.php?u=10.1021/acsaem.0c01173 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets generated and/or analysed during the current study are not publicly available due to the data form part of an ongoing study but are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.