Abstract

Atherosclerosis is a chronic inflammatory disease, this study aims to investigate the immune landscape in carotid atherosclerotic plaque formation and explore diagnostic biomarkers of lactylation-associated genes, so as to gain new insights into underlying molecular mechanisms and provide new perspectives for disease detection and treatment. Single cell transcriptome data and Bulk transcriptome data of carotid atherosclerosis samples were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO). Eleven cell types were identified by scRNA-seq data. Lactylation scores were significantly higher in γδT cells than in cells of other subtypes, but lower in plasma cells than in cells of other subtypes. The scores of malignant related pathways were significantly increased in cells with high lactylation scores. scRNA-seq combined with bulk-seq identified differentially expressed lactylation genes in carotid atherosclerosis. A diagnostic model was constructed by combining 10 machine learning algorithms and 101 algorithms, SOD1, DDX42 and PDLIM1 as core genes. Further analysis revealed that the expression levels of core genes were significantly correlated with immune cell infiltration, and their regulatory networks were constructed. Clinical samples verified that the expression of core gene in unstable plaque was significantly lower than that in stable plaque, suggesting that it has protective effect on atherosclerosis. By combining scRNA-seq and Bulk transcriptome data in this study, three lactylation-associated genes SOD1, DDX42 and PDLIM1 were identified in carotid atherosclerosis samples, providing targets for the diagnosis and treatment of carotid atherosclerosis samples.

Keywords: Carotid atherosclerosis, Lactylation, Gene, Immune, Single cell, Machine learning

Subject terms: Computational biology and bioinformatics, Immunology, Diseases, Medical research, Pathogenesis

Introduction

Carotid atherosclerosis plays a substantial role in cerebrovascular disease by progressively narrowing the vessel lumen partially or completely, thereby reducing cerebral blood flow and triggering symptoms such as blurred vision and sudden loss of consciousness. In more severe cases, acute plaque rupture may induce local thrombosis and subsequent vascular occlusion, significantly elevating the risk of ischemic stroke and cerebral infarction1,2. Stroke remains the second most common cause of death worldwide3,4. Although the incidence and mortality of carotid atherosclerosis have notably decreased in high-income countries due to advancements in healthcare, improved living standards, and comprehensive health management, it continues to pose a significant public health challenge in many low- and middle-income countries5. The onset and progression of atherosclerosis are governed by a complex network of molecules and signaling pathways. Atherosclerosis involves both aerobic and anaerobic glycolysis, where lactate, the metabolic byproduct, plays a critical role in pathological processes, including endothelial cell dysfunction, vascular smooth muscle cell proliferation, migration, phenotypic conversion, lipid accumulation, vascular inflammation, and calcification6,7. Targeting glycolysis and lactate may present innovative therapeutic strategies for preventing and treating atherosclerosis. As an epigenetic disorder, atherosclerosis emerges from the intricate interplay of various epigenetic mechanisms, with recent studies delving into the specific epigenetic modifications linked to its pathogenesis8. Lactate has recently been identified as a significant epigenetic regulator, with its metabolic accumulation serving as a precursor for histone lysine lactylation, thereby influencing epigenome reprogramming9. Wan et al. revealed the widespread presence of lactylation within the human proteome, indicating substantial prospects for advancing lactylation research10. In vitro studies have demonstrated that increased lactic acid levels impair T cell migration, trigger the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-17 by T cells, and sustain local chronic inflammation11. Studies have shown that lactylation occurs in a variety of protein, including histone and non-histone, and is related to a variety of physiological and pathological backgrounds12. Although lactylation-related genes have been associated with cell metabolism, disease progression, and immune infiltration in previous research, their expression and function in atherosclerosis remain unexamined. This gap highlights the necessity for further exploration into the mechanisms and implications of lactylation in atherosclerosis.

High-throughput sequencing technologies, including RNA sequencing and single-cell sequencing, generate vast gene expression datasets that are critical for identifying differential genes and signaling pathways implicated in atherogenesis. Bioinformatics analyses have been leveraged to explore hub genes correlated with the progression, instability, and rupture of carotid atherosclerotic plaques13–15. The immune response to lipid-induced inflammation within the arterial subendothelial intima constitutes a fundamental mechanism in atherosclerosis. The infiltration of immune cells into the vascular wall plays a significant role in the stability and progression of atherosclerosis16. Understanding the distribution of immune cells within affected tissues, alongside a detailed characterization of their type, composition, and functional status in atherosclerosis, is imperative for elucidating their cellular roles17. Advances in medical technology have markedly enhanced the precision in diagnosing and treating atherosclerosis. Emerging strategies, particularly lactylation and immunotherapy, present promising avenues for targeted interventions in cases where patients exhibit insufficient response to lipid-lowering agents and traditional anti-atherosclerotic therapies. Despite these advancements, the pathogenesis of carotid atherosclerosis remains inadequately understood, with limited insights into the functions of lactylation-related genes, immune-related characteristics, and diagnostic biomarkers in atherosclerotic plaque formation. This study conducted a comprehensive analysis of single-cell and transcriptome data, utilizing ten machine learning algorithms to pinpoint hub genes implicated in lactylation that influence carotid atherosclerosis. Validation of protein expression of these hub genes was performed on carotid endarterectomy specimens through HE staining and immunohistochemical analysis. The findings shed light on the molecular underpinnings of carotid atherosclerosis, highlighting the significance of lactylation in its pathogenesis and offering valuable insights for the development of personalized precision therapies for this condition.

Materials and methods

Data source

GSE159677, GSE21545, GSE24495, and GSE43292 datasets were procured from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/geo/). GSE159677 comprised single-cell transcriptomic profiles from three carotid atherosclerosis samples and three adjacent non-diseased samples. GSE21545 provided bulk transcriptomic data from 126 carotid atherosclerosis specimens, whereas GSE24495 included bulk data from 133 such specimens. GSE43292 contributed bulk transcriptomic profiles from 32 carotid atherosclerosis samples and an equal number of controls. A total of 336 lactylation-associated genes were curated from prior studies10,18,19. The datasets GSE21545, GSE24495, and GSE43292 were subsequently merged and normalized using the R packages “limma” and “sva” to correct for batch effects.

Single-cell data analysis

Single-cell data were processed and analyzed utilizing the “Seurat” package in R version 4.2.2. The filtering parameters applied were nFeature_RNA (< 5000 genes per cell), percent_mito (< 15% mitochondrial gene expression), percent_ribo (> 3% ribosomal gene expression), and percent_hb (< 0.1% red blood cell gene expression). Post-filtering, the dataset comprised 21,013 genes and 46,969 cells. Data normalization was executed via the ScaleData function, followed by PCA on the scaled data. Dimensionality reduction was achieved through UMAP using the RunUMAP function. Cell annotation was conducted by integrating the “singleR” package with manual curation. Differential gene expression across clusters was identified using the FindAllMarkers function. HALLMARK pathway data were sourced from the Msigdb database, with pathway scoring for each cell performed via the GSVA R package. The outcomes were represented using a heat map.

Difference analysis of bulk sequencing data

The differential analysis was performed using the “Limma” package in R software version 4.2.2, applying a threshold of corrected P < 0.05 for identifying differential genes. The outcomes were visualized via heat maps and volcano plots.

Functional enrichment analysis

GO functional enrichment analysis, a widely adopted method for interpreting large-scale gene datasets, includes three key domains: biological process (BP), cellular component (CC), and molecular function (MF). The Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) was utilized to explore gene set relationships and their roles within signaling pathways. Enrichment analyses integrating GO and KEGG were executed via the “ClusterProfiler” package in R, with statistical significance determined at P < 0.05. For gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA), the C2.Reactome dataset was sourced from the Msigdb database and subsequently analyzed using the “ClusterProfiler” package.

Building a diagnostic model based on machine learning

This study employed ten machine learning algorithms and 101 algorithmic combinations to construct a highly accurate diagnostic model. The algorithms utilized were Random Survival Forest (RSF), Elastic Net (Enet), Lasso, Ridge, Stepwise Cox, CoxBoost, Partial Least Squares Regression for Cox (plsRcox), Supervised Principal Component (SuperPC), Generalized Boosting Model (GBM), and Survival Support Vector Machine (survival-SVM). The model development involved: (a) identifying diagnostic genes in the training set through univariate Cox regression; (b) applying the 101 algorithmic combinations to these genes, followed by fitting the predictive models using a leave-one-out cross-validation (LOOCV) approach; (c) validating the models on both the test dataset and the entire dataset; and (d) assessing the area under the ROC curve (AUC) for each model across all validation datasets, with the model yielding the highest AUC selected as optimal.

Immune infiltration analysis

The “GSVA” package within R software was employed to perform single-sample gene set enrichment analysis (ssGSEA), utilizing integrated expression profile data. This approach quantified the infiltration scores for various immune cell types within the immune microenvironment of each sample.

RegNetwork database

The RegNetwork database (https://regnetworkweb.org/) serves as a comprehensive resource for transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulatory interactions in humans and mice, encompassing relationships such as transcription factor to transcription factor (TF → TF), transcription factor to gene (TF → gene), transcription factor to microRNA (TF → miRNA), microRNA to transcription factor (miRNA → TF), and microRNA to gene (miRNA → gene)20. This study leveraged the RegNetwork database to predict upstream miRNAs and TFs relevant to gene regulation.

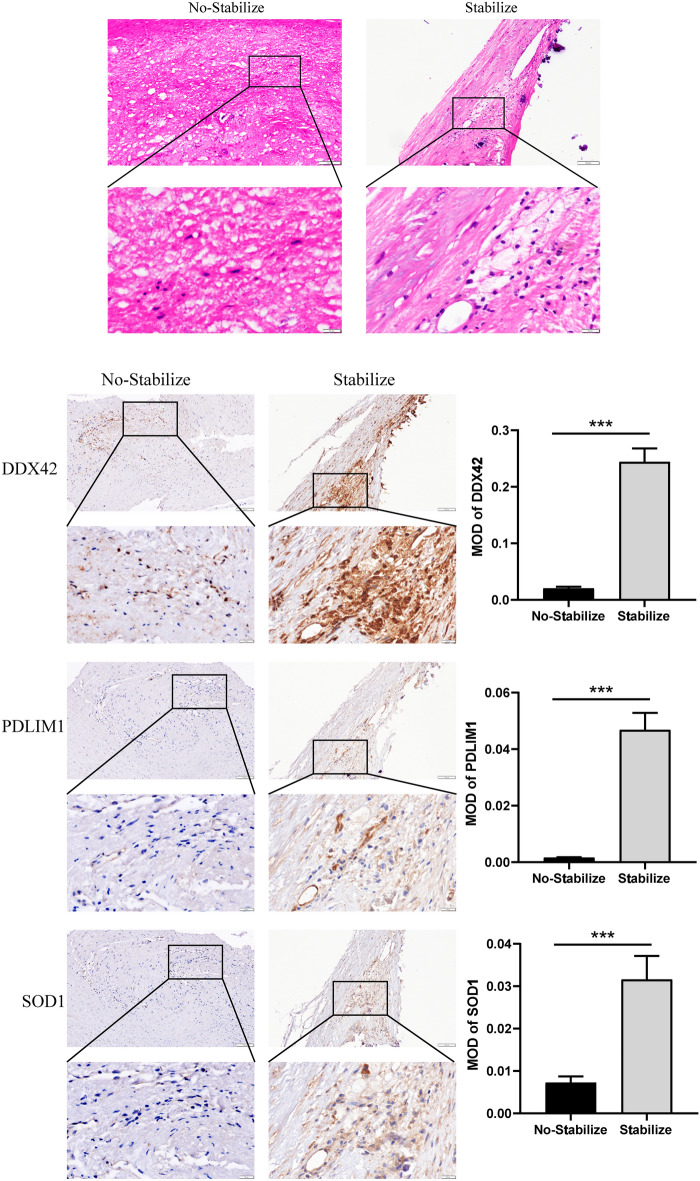

HE staining

The archival tissue samples of stable (10 groups) and unstable carotid plaque (10 groups) came from the pathological samples previously archived by the pathology department of the hospital. This study confirms that all experimental schemes have been approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University.These samples were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde and subsequently embedded in paraffin. Sections of 4–5 μm thickness were then dewaxed, rehydrated, and washed before being stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E).

Immunohistochemistry

Tissues were fixed in formalin for over 24 h, followed by a dehydration process through graded alcohol immersion (75%, 95%, 95%, 100%, 100%). Post-dehydration, the tissues were triple-waxed and embedded. Sections were sliced at 5 µm thickness using a microtome, floated on water at 40°C, and mounted onto glass slides, which were then baked in a slide dryer for 30 min. Dewaxing and rehydration were carried out through sequential immersion in xylene (xylene I, II, III) and progressively diluted alcohol solutions (100%, 90%, 80%, 70%, 0%). The rehydrated sections then underwent heat-induced antigen retrieval in a 96°C solution. Endogenous enzyme activity was suppressed using hydrogen peroxide, followed by slide sealing. Sequential application of primary antibodies (SOD1 (1: 200, Immunoway, YN5474) , DDX42 (1: 200, Immunoway, YN0489) , and PDLIM1 (1: 200, Immunoway, YT0979) ) and secondary antibodies was conducted. Streptavidin-peroxidase solution was then added and allowed to react at room temperature. DAB was used to visualize the reaction, and the slides were rinsed with water. Hematoxylin was applied for counterstaining for 1–2 min, followed by brief differentiation with 1% hydrochloric acid alcohol for 3 s, after which the slides were rinsed again. The slides were dehydrated, sealed, and subsequently imaged.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons of measurement data across groups utilized either the t-test or U-test, contingent upon the distribution normality. Pearson correlation analysis was performed to assess relationships between variables. All statistical analyses were executed using R software, with significance thresholds set as #0.05 < p < 0.2, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001.

Results

scRNA-seq data identified 11 types of cells in carotid plaque tissue

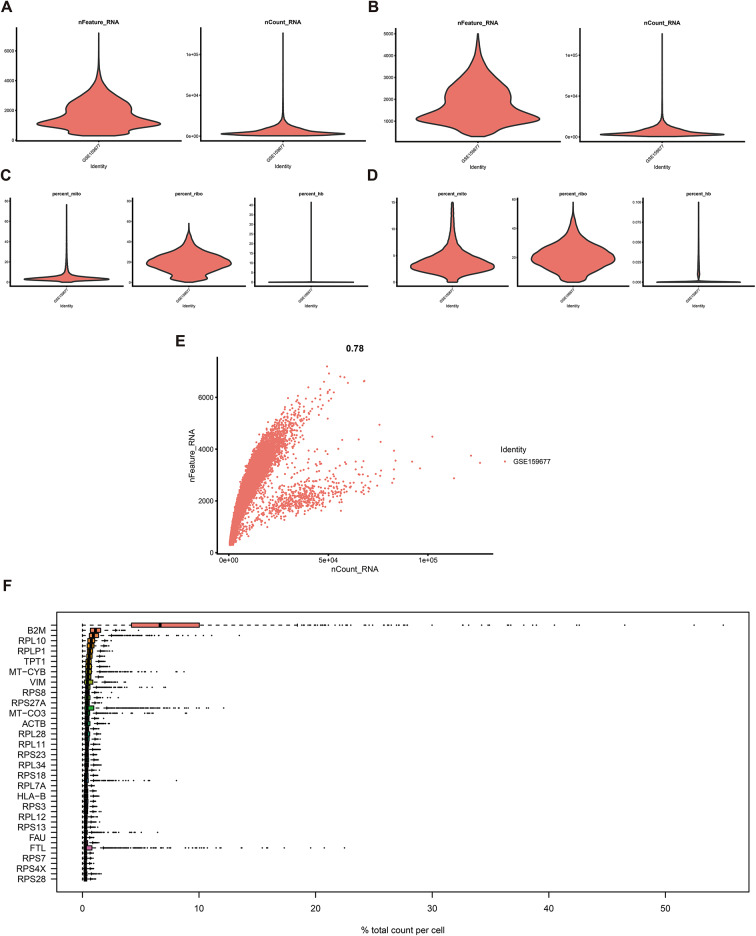

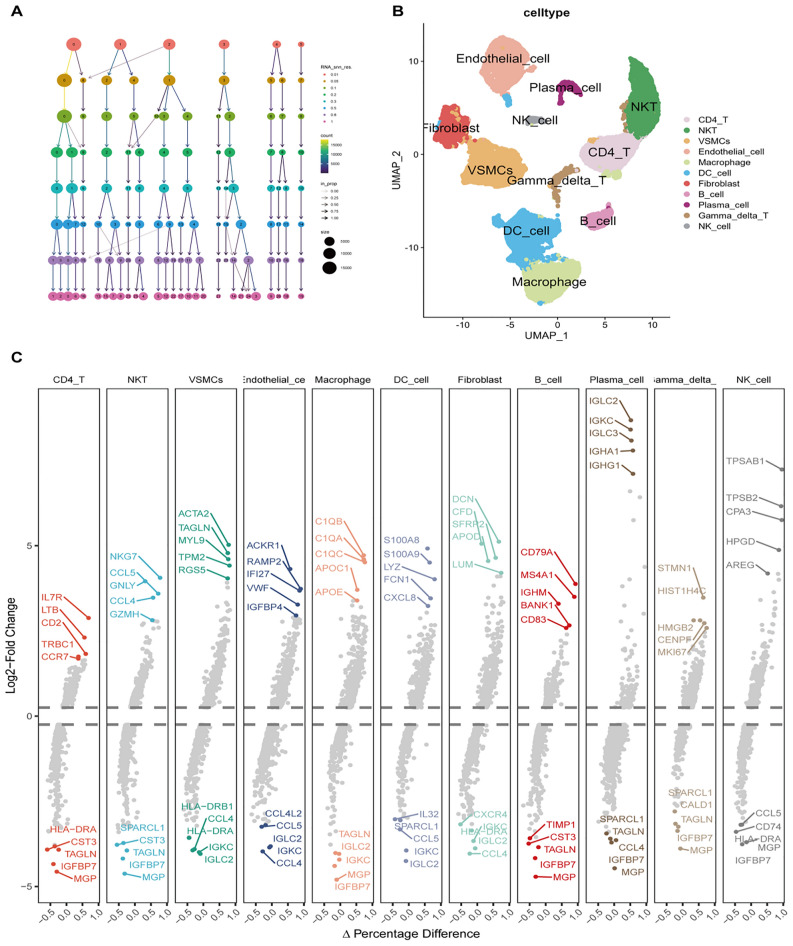

To characterize the immune microenvironment of carotid atherosclerosis at the single-cell level, scRNA-seq analysis was performed utilizing publicly accessible datasets. Quality control measures, depicted in Fig. 1A–E, validated the data integrity after filtering. Figure 1F identified B2M, RPL10, and RPLP1 as the most highly expressed genes. Dimensionality reduction of the scRNA-seq data facilitated cell staging at varying resolutions, as illustrated in Fig. 2A. UMAP analysis identified 11 distinct cell types, including CD4 T cells, NKT cells, VSMC cells, endothelial cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, fibroblasts, B cells, plasma cells, γδT cells, and NK cells (Fig. 2B). Marker genes corresponding to these cell types were subsequently identified (Fig. 2C). TOP5 genes of CD4 + T cells are IL7R, LTB, CD2, TRBC1 and CCR7, respectively; top5 genes of NK T cells are NKG7, CCL5, GNLY, CCL4 and GZMH, respectively; top5 genes of VSMCs are ACTA2, TAGLN, MYL9, TPM2 and RGS5, respectively; top5 genes of epithelial cells are ACKR1, RAMP2, IFI27, VWF and IGFBP4, respectively; top5 genes of macrophages are C1QB, C1QA, C1QC, APOC and APOE, respectively; top5 genes of DC cells are S100A8, S100A9, LYZ, FCN1 and CXCL8, respectively; top5 genes genes of fibroblasts are DCN, CFD, SFRP2, APOD and LUM, respectively; top5 genes of B cells are CD79A, MS4A1, IGHM, BANK1 and CD83, respectively; top5 genes of plasma cells are IGLC2, IGKC, IGLC3, IGHA1 and IGGH1, respectively; top5 genes of γδT cells are STMN1, HIST1H, HMGB2, CENPF and MKI67, respectively; top5 genes of NK cells are TPSAB1, TPSB2, CPA3, HPGD and AREG respectively (Fig. 2C).

Fig. 1.

Overview of single-cell data. (A–B) Single-cell data metrics, nFeature_RNA and nCount_RNA, were analyzed before (A) and after (B) applying the filtering criteria. (C–D) Proportions of percent.mito, percent.ribo, and percent.hb were assessed before (C) and after (D) filtering. (E) A direct correlation between nFeature_RNA and nCount_RNA was observed. (F) The most highly expressed genes were highlighted.

Fig. 2.

Single-cell data analysis of cell staging, clustering, and gene expression. (A) Dimensionality reduction techniques revealed cell staging across different resolutions. (B) UMAP reduction illustrated cell clustering. (C) The FindAllMarkers function was employed to identify differentially expressed genes, showcasing the top five upregulated and downregulated genes in each cell.

Analysis of lactylation score at the single-cell level

To investigate the functional characteristics of distinct cell types, HALLMARK pathway scores were calculated for each cell subtype. Figure 3A presents these scores, highlighting pronounced enrichment of ALLOGRAFT_REJECTION in CD4 + T cells and NKT cells; MYOGENES/S and EPITHELIAL_MESENCHYMAL_TRANSITION in VSMCs and fibroblasts; and TNFA_SIGNALING_VIA_NFKB, COMPLEMENT, and INFLAMMATORY_RESPONSE in macrophages and dendritic cells. Additionally, lactylation scores for each cell type were determined and subjected to correlation analysis with HALLMARK pathway scores. The analysis revealed a strong positive correlation between the lactylation score and pathways such as MYC TARGETS, MTORC1 SIGNALING, OXIDATIVE PHOSPHORYLATION, and E2F TARGETS across most cell types (Fig. 3B); these pathways were often implicated in cancer progression. Notably, in plasma cells, the lactylation score correlated positively with nearly all pathways, indicating a potential involvement of lactylation in diverse biological processes within these cells. A comparative analysis of lactylation scores across various cell subtypes demonstrated a marked increase in γδT cells relative to other subtypes, while plasma cells exhibited notably lower scores (Figs. 4A, D). Figure 4B–C highlighted the top 10 marker genes across 11 cell types. Cells were stratified into high and low expression groups according to their lactylation gene set scores. In the high lactylation score group, the proportions of CD4 + T cells, NK T cells, and B cells were reduced, whereas VSMCs, endothelial cells, and dendritic cells showed an increase (Fig. 4E). Furthermore, the high lactylation score group exhibited significantly elevated scores across multiple malignancy-associated pathways (ALLOGRAFT REJECTION, INTERFERON GAMMA RESPONSE, INTERFERON ALPHA RESPONSE, TNFA SIGNALING VIA NFKB, IL6 JAK STAT3 SIGNALING, INFLAMMATORY RESPONSE, COMPLEMENT, MYC TARGETS V1, OXIDATIVE PHOSPHORYLATION , E2F TARGETS, G2M CHECKPOINT, FATTY ACID METABOLISM and HYPOXIA) compared to the low lactylation score group (Fig. 4F).

Fig. 3.

HALLMARK pathway and lactylation scores. (A) Heat map displaying the HALLMARK pathway scores across individual cells. (B) Heat map illustrating the correlation between lactylation levels and HALLMARK pathways.

Fig. 4.

High and low expression grouping of the lactylation gene set. (A) Distribution of lactylation pathway scores across different cell types. (B–C) Violin plot (B) and heat map (C) highlighting the top 10 marker genes for each cell type. (D) UMAP visualization of lactylation gene set scores. (E) Showing the number and proportion of each cell type categorized by high and low lactylation gene set scores. (F) Heat map comparing HALLMARK pathway scores between high and low expression groups.

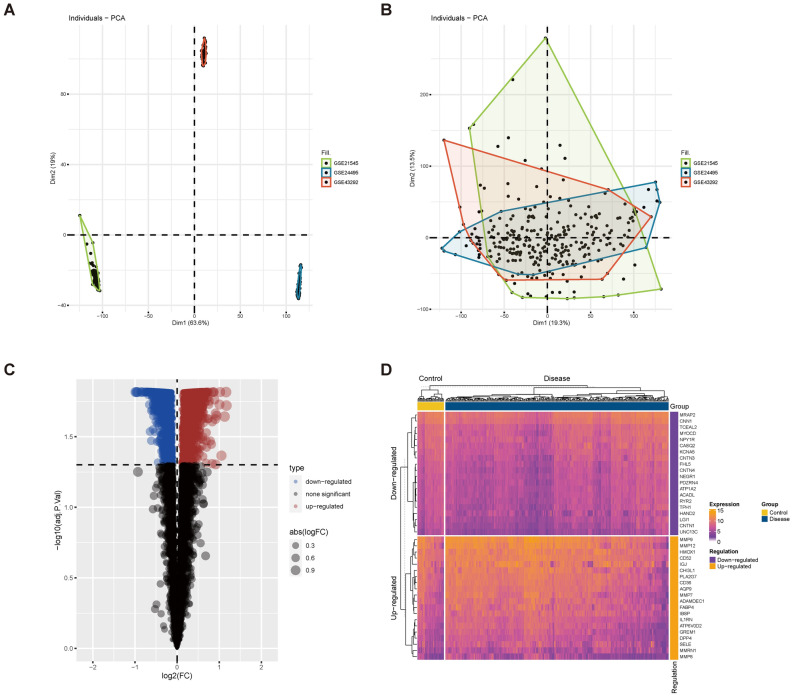

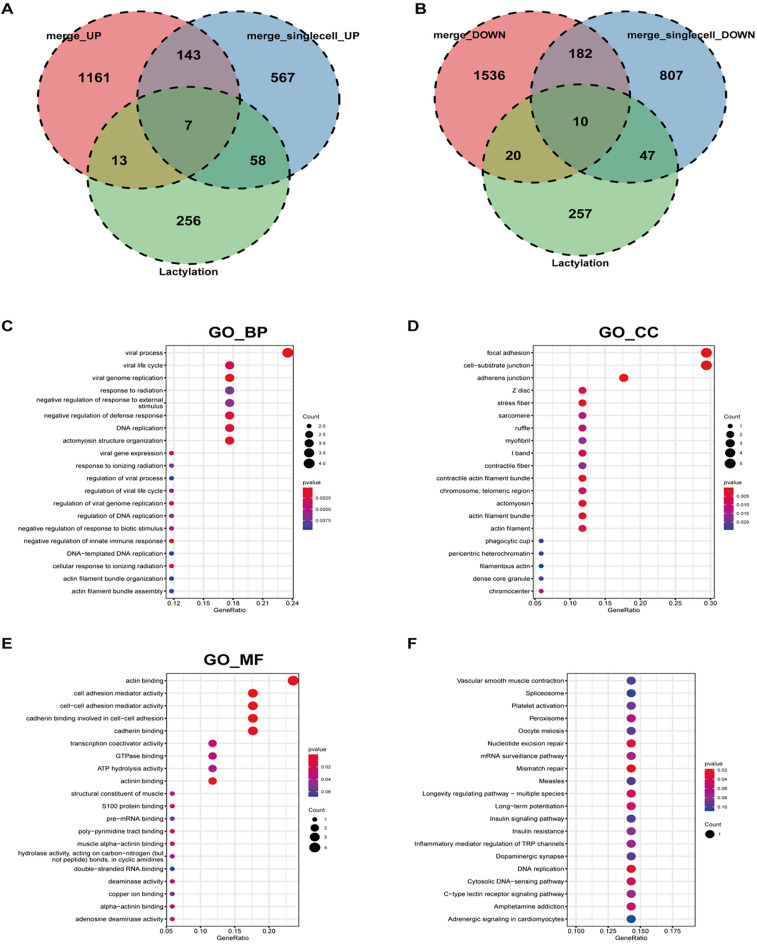

scRNA-seq combined with bulk transcriptome to identify lactylation-related differential genes

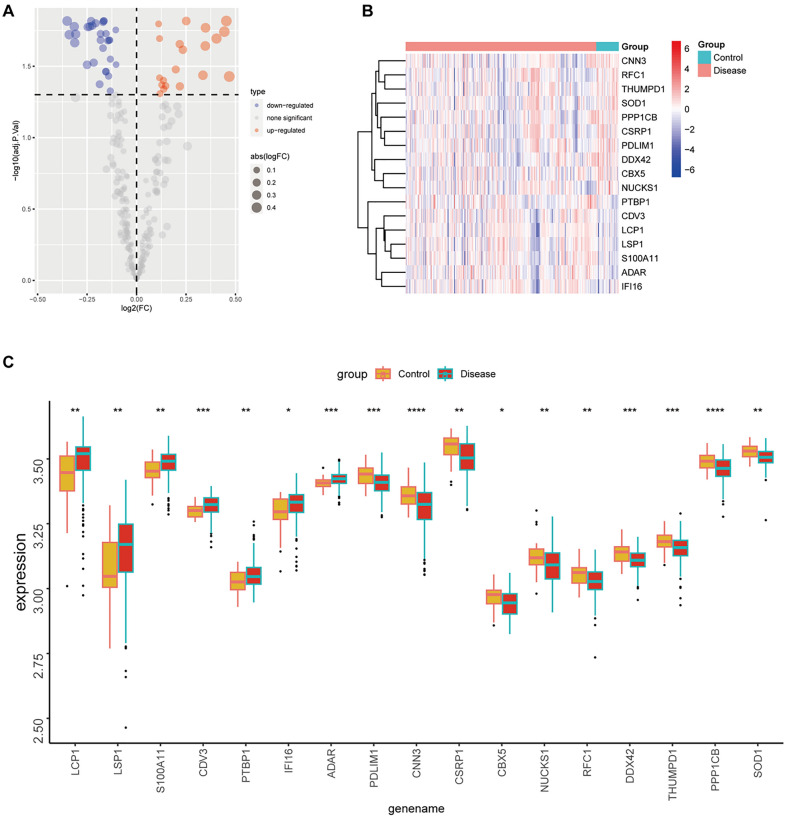

To achieve sufficient sample size and eliminate batch effects, datasets GSE21545, GSE24495, and GSE43292 were integrated. PCA validated the effective removal of batch effects (Fig. 5A–B). Differential expression analysis identified 3072 dysregulated genes in the carotid atherosclerosis group compared to the control, with 1324 up-regulated and 1748 down-regulated (Fig. 5C). The top 20 most significantly dysregulated genes were presented (Fig. 5D). Intersection analysis of differentially expressed genes from both single-cell and bulk transcriptomes with lactylation-related molecules identified 7 commonly up-regulated and 10 commonly down-regulated genes (Fig. 6A–B). GO-BP enrichment analysis indicated these genes were primarily involved in viral processes, including viral life cycle, genome replication, response to radiation, and negative regulation of response to external stimuli (Fig. 6C). GO-CC enrichment analysis localized these molecules to focal adhesion, cell-substrate junctions, adherens junctions, Z discs, stress fibers, sarcomeres, and ruffles (Fig. 6D). GO-MF analysis identified that these molecules predominantly participate in actin binding, cell adhesion mediator activity, cell–cell adhesion mediator activity, cadherin binding involved in cell–cell adhesion, cadherin binding, transcription coactivator activity, and GTPase binding activity (Fig. 6E). KEGG analysis further indicated their involvement in pathways such as vascular smooth muscle contraction, spliceosome function, platelet activation, peroxisome function, oocyte meiosis, nucleotide excision repair, and mRNA surveillance (Fig. 6F). Expression levels of seven genes with consistent upregulation and ten genes with downregulation were evaluated in carotid plaque versus control tissues (Fig. 7A–C). Specifically, LCP1, LSP1, S100A11, CDV3, PTBP1, IF116, and ADAR exhibited increased expression in carotid plaque tissues, while PDLIM1, CNN3, CSRP1, CBX5, NUCKS1, RFC1, DDX42, THUMPD1, PPP1CB, and SOD1 displayed decreased expression (Fig. 7B–C).

Fig. 5.

Differential gene analysis of carotid arteriosclerosis and normal groups. (A) Gene expression before batch effect correction; (B) Gene expression after batch effect correction; (C–D) Differential analysis using the R language limma package; (C) Volcano plot illustrating differential gene expression; (D) Heat map visualizing the differential genes between diseased and healthy tissues.

Fig. 6.

Intersection of differential gene sets. (A) Intersection of up-regulated differential genes with the lactylation gene set identified 7 differentially expressed genes; (B) Intersection of down-regulated differential genes with the lactylation gene set revealed 10 differentially expressed genes; (C–E) GO annotation of the intersecting differential genes; (F) KEGG pathway enrichment analysis of the intersecting differential genes.

Fig. 7.

Expression levels of differential genes. (A–B) The volcano plot (A) and heat map (B) depict the expression differences of 17 intersecting differentially expressed genes between diseased and healthy tissues; (C) Box plot illustrates the expression levels of 17 differential genes in diseased versus healthy tissues (ns p > 0.05, *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001).

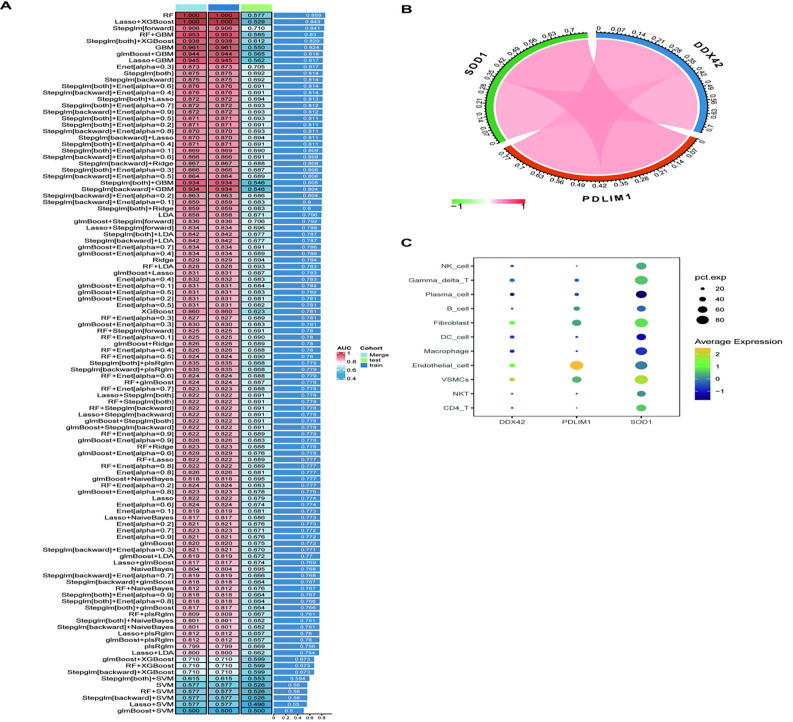

Machine learning to identify hub genes of carotid arteriosclerosis

A comprehensive screening for hub genes linked to carotid arteriosclerosis was conducted using ten machine learning algorithms, including various combinations. The RF algorithm demonstrated an AUC of 1 in the training dataset, 0.577 in the test dataset, and 1 in the overall dataset (Fig. 8A). The model identified three hub genes—SOD1, DDX42, and PDLIM1—exhibiting strong positive correlations (Fig. 8B). Single-cell analysis revealed distinct expression patterns: DDX42 was highly expressed in fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and VSMCs; PDLIM1 was notably expressed in B cells, fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and VSMCs; and SOD1 was predominantly expressed in NK cells, γδT cells, fibroblasts, VSMCs, NKT cells, and CD4 + T cells (Fig. 8C).

Fig. 8.

Identification of hub genes in carotid arteriosclerosis using machine learning. (A) Machine learning algorithms were employed to select critical differential genes from a pool of 17 candidates to construct a diagnostic model; (B) Correlation analysis of the three hub genes, with red indicating positive correlation and green indicating negative correlation; (C) Single-cell level expression profiles of the three hub genes.

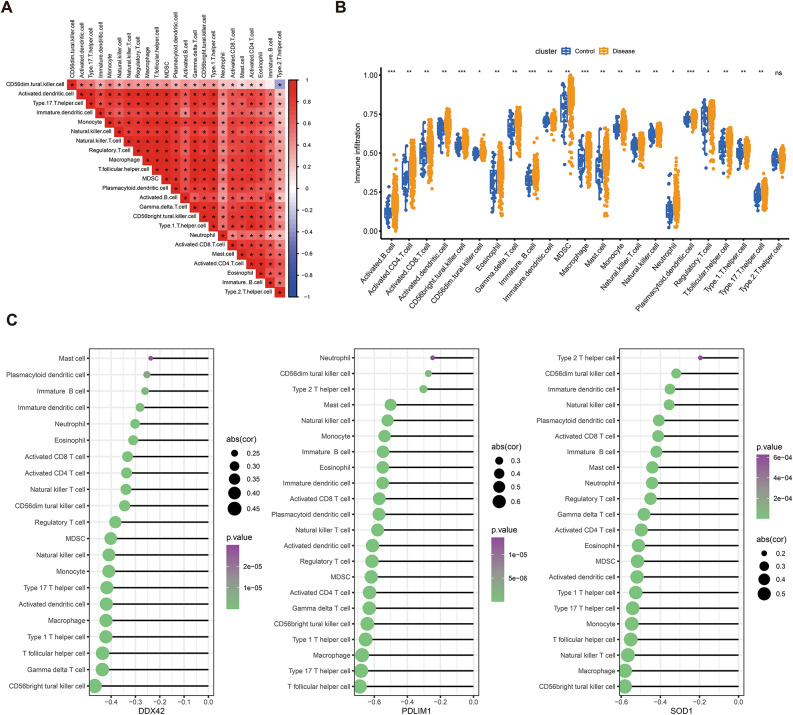

SOD1, DDX42 and PDLIM1 were associated with immune infiltration in carotid atherosclerosis

Immune cell infiltration levels in carotid atherosclerosis tissue were quantified using the ssGSEA algorithm, followed by correlation analysis among infiltration scores. A robust positive correlation was observed across all immune cell types (Fig. 9A). In comparison to the control group, infiltration scores were markedly elevated for activated B cells, activated CD4 + T cells, activated CD8 + T cells, activated dendritic cells, CD56high NK cells, CD56low NK cells, eosinophils, γδ T cells, immature B cells, immature dendritic cells, MDSCs, macrophages, mast cells, NKT cells, NK cells, neutrophils, plasmacytoid dendritic cells, regulatory T cells, T follicular helper (Tfh) cells, Th1, Th2, and Th17 cells (Fig. 9B). Furthermore, correlation analysis identified inverse relationships between the expression levels of SOD1, DDX42, and PDLIM1 and immune cell infiltration scores. Notably, DDX42 exhibited a strong negative correlation with CD56high NK cells, γδ T cells, and Tfh cells. PDLIM1 was negatively correlated with Tfh cells, Th17 cells, and macrophages, while SOD1 showed an inverse correlation with CD56high NK cells, macrophages, and NKT cells (Fig. 9C).

Fig. 9.

Analysis of immune cell infiltration. (A) Correlation matrix of immune cell infiltration proportions. (B) Comparative analysis of immune cell infiltration levels between healthy and control groups, with significance levels indicated as ns (p > 0.05), * (p < 0.05), ** (p < 0.01), and *** (p < 0.001). (C) Correlation between the three hub genes and immune cell infiltration, displaying only immune cells with p < 0.05. The circle’s size indicates the magnitude of the correlation coefficient, while color intensity reflects the p-value.

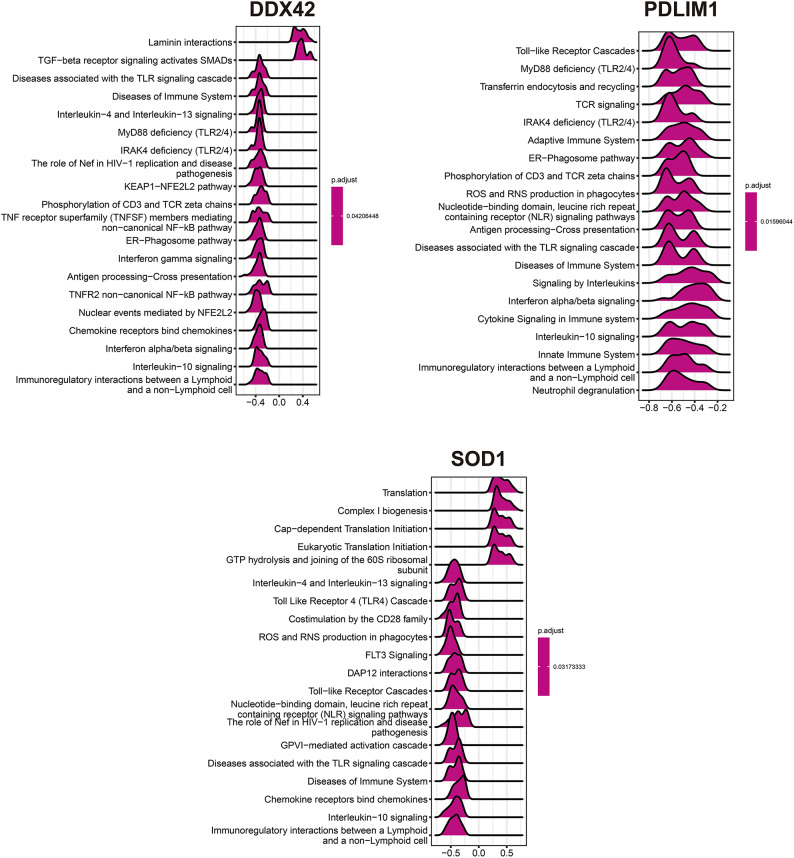

Functional enrichment analysis of SOD1, DDX42 and PDLIM1 in carotid atherosclerosis

To examine the roles of SOD1, DDX42, and PDLIM1 in carotid atherosclerosis, the top 50 genes positively correlated with their expression levels were identified (Fig. 10). Subsequent GSEA for each gene revealed distinct pathway associations. Elevated DDX42 expression correlated with significant enrichment in Laminin interactions and TGF-beta receptor signaling pathways that activate SMADs. In contrast, reduced DDX42 expression was linked to pronounced enrichment in pathways associated with TLR signaling, immune system diseases, Interleukin-4 and Interleukin-13 signaling, and MyD88 deficiency (TLR2/4) (Fig. 11). Diminished PDLIM1 expression was similarly associated with significant enrichment in pathways such as Toll-like Receptor Cascades, MyD88 deficiency (TLR2/4), Transferrin endocytosis and recycling, TCR signaling, and IRAK4 deficiency (TLR2/4) (Fig. 11). Additionally, increased SOD1 expression resulted in significant enrichment in pathways related to Translation, Complex I biogenesis, Cap-dependent Translation Initiation, and Eukaryotic Translation Initiation. Conversely, decreased SOD1 expression was associated with significant enrichment in Interleukin-4 and Interleukin-13 signaling, Toll-Like Receptor 4 (TLR4) Cascade, CD28 family costimulation, and ROS and RNS production in phagocytes (Fig. 11).

Fig. 10.

Heat map of three genes and top 50 positively correlated genes.

Fig. 11.

GSEA analysis of three single genes. (The value represents the enrichment score, where > 0 indicates a positive correlation between the gene and the pathway, and < 0 indicates a negative correlation).

Regulatory network of SOD1, DDX42, and PDLIM1

To investigate the regulatory mechanisms governing SOD1, DDX42, and PDLIM1, upstream miRNAs and TFs were predicted using the RegNetwork database (Fig. 12). DDX42 was regulated by 15 TFs and 15 miRNAs, PDLIM1 by 5 TFs and 10 miRNAs, and SOD1 by 23 TFs and 5 miRNAs (Fig. 12). Notably, E2F1 was found to regulate the transcription of both DDX42 and PDLIM1, while MYC and EGR1 concurrently regulated the transcription of DDX42 and SOD1 (Fig. 12).

Fig. 12.

Regulatory network of SOD1, DDX42, and PDLIM1.

Expressions of SOD1, DDX42 and PDLIM1 in tissues

HE staining was employed to distinguish between stable and unstable plaque lesions, followed by immunohistochemical analysis to quantify the expression levels of three key genes.Unstable plaques typically have characteristics such as thinner fibrous caps, enlarged lipid cores, intraplaque hemorrhage, and increased inflammation21. These features make plaques prone to rupture or ulceration, potentially leading to intracerebral thrombosis or embolism. In contrast, stable plaques usually have a simple structure, consisting of lipid accumulation and foam cells22. A significant reduction in DDX42, PDLIM1, and SOD1 expression was observed in unstable plaques compared to stable ones, suggesting a potential protective role for these genes in the progression of carotid atherosclerosis (Fig. 13).

Fig. 13.

Immunohistochemistry of SOD1, DDX42 and PDLIM1.

Discussion

Atherosclerosis, a chronic arterial disorder and a leading cause of cardiovascular diseases, is pathologically defined by the gradual accumulation of lipid deposits within the arterial wall, resulting in the formation of atherosclerotic plaques and characteristic lesions8. Carotid atherosclerosis, a major contributor to cerebrovascular disease, advances through distinct stages: early stages manifest as carotid intima-media thickening and fatty streaks, while advanced stages are distinguished by the development of atherosclerotic plaques. These advanced plaques are particularly susceptible to rupture, significantly elevating the risk of ischemic stroke23–26. Stroke prevention necessitates the identification of biomarkers in patients with carotid atherosclerosis and the targeting of therapies to stabilize plaques, thereby reducing the likelihood of adverse cardiovascular and cerebrovascular events27.

Under normal physiological conditions, cells predominantly rely on oxidative phosphorylation for glucose metabolism, with glycolysis being activated primarily under hypoxic conditions. Oxygen delivery to vascular wall cells is mediated by blood flow within the lumen or through the adventitial vasa vasorum. During the progression of atherosclerotic plaque, luminal narrowing increases oxygen demand within the vessel wall, reducing oxygen diffusion to the intima and resulting in localized hypoxia. Consequently, intimal cells adapt by shifting to glycolysis for energy production. In atherosclerosis, both aerobic and anaerobic glycolysis pathways contribute to elevated lactate levels28. Recent studies have revealed that lactate, a byproduct of glycolysis, exerts a significant and complex influence on the progression of atherosclerosis. Shantha et al. reported a strong correlation between elevated blood lactate levels and plaque burden in carotid atherosclerosis, independent of conventional cardiovascular risk factors, implicating lactate in the initiation and progression of the disease29. Additionally, lactate has been identified as a novel signaling molecule and an active immunomodulator, playing roles in both innate and adaptive immune responses30. Moreover, lactate serves as a donor for protein lactylation, a recently discovered modification that links metabolic reprogramming to epigenetic regulation, thereby influencing various cellular processes31. Lactylation, a dynamic and reversible post-translational modification mediated by specific enzymes, intricately regulates cellular functions by modulating protein structure and activity. This modification affects various biological processes, including gene transcription and signal transduction32. Although its importance is increasingly recognized, research on lactylation remains nascent, especially in non-neoplastic conditions such as arteriosclerosis, warranting further in-depth investigation. Currently, the immune landscape of carotid atherosclerotic plaques has not been thoroughly characterized within a histological context. This study identified 11 distinct cell types in carotid artery tissue: CD4 + T cells, NKT cells, VSMCs, endothelial cells, macrophages, dendritic cells, fibroblasts, B cells, plasma cells, γδ T cells, and NK cells. Lactylation scores were calculated for each cell type and subsequently correlated with HALLMARK pathway scores. Notably, positive correlations were identified between lactylation scores and the MYC TARGETS, MTORC1 SIGNALING, OXIDATIVE PHOSPHORYLATION, and E2F TARGETS pathways across nearly all cell types, pathways commonly linked to cancer progression. Lactylation score comparisons across cell subtypes identified a marked elevation in γδ T cells and a reduction in plasma cells. γδ T cells, distinguished by their unique T cell receptors comprising γ and δ chains, are primarily located in the intestinal mucosa, skin, and lungs, where they initiate and propagate immune responses33. In the intestinal tract, γδ T cells are implicated in metabolic regulation and the progression of cardiovascular disease34, suggesting their potential role in atherosclerosis, which merits further exploration. The progression of plaque is notably characterized by inflammatory cell infiltration and immune pathway activation26. Foundational research suggests that lactate exerts effects on various cell types involved in atherosclerosis, including vascular endothelial cells, VSMCs, macrophages, and lymphocytes, via intricate intracellular mechanisms35,36. Cells were categorized into high and low expression groups according to the lactylation gene set score. In the high lactylation score group, a reduction in the proportion of CD4 + T cells, NKT cells, and B cells was observed, while an increase was noted in VSMCs, endothelial cells, and dendritic cells. SMCs and endothelial cells play a central role in both sustaining and exacerbating inflammation, whereas dendritic cells are often linked to plaque rupture, neovascularization, and intramural hemorrhage. The shift in immune cell composition suggests that the high lactylation score group more closely corresponds with the characteristics of advanced arterial plaque23–26. Additionally, this group demonstrated significantly elevated scores in malignancy-related pathways compared to the low lactylation score group. This study is the first to elucidate the intricate relationship between lactylation levels and immune cell infiltration using single-cell analysis, emphasizing the lactylation profile in carotid atherosclerosis. Targeting lactylation and its associated genes could represent a promising therapeutic strategy.

High-throughput sequencing technologies, such as transcriptome and single-cell sequencing, have been employed to examine gene expression profiles, enabling the study of immune cell distribution and the identification of molecular diagnostic biomarkers. Machine learning, a powerful approach for identifying critical cell types and diagnostic markers, has been widely applied to pinpoint relevant biomarker features, as well as to classify and validate these biomarkers37,38. This study employed scRNA-seq alongside bulk transcriptome analysis to identify common lactylation-associated differential genes, resulting in the identification of 7 upregulated and 10 downregulated genes. Through the application of 10 machine learning algorithms, three signature genes—SOD1, DDX42, and PDLIM1—were identified. Correlation analysis demonstrated that the expression levels of SOD1, DDX42, and PDLIM1 were inversely associated with infiltration scores of various activated immune cells within carotid plaques. Notably, DDX42 exhibited a significant negative correlation with CD56high NK cells, γδ T cells, and Tfh cells; PDLIM1 was negatively correlated with Tfh cells, Th17 cells, and macrophages; while SOD1 showed a significant negative correlation with CD56high NK cells, macrophages, and NK T cells. Histological examination using HE staining and immunohistochemical staining of carotid unstable and stable plaque tissues from pathology archives further highlighted the potential regulatory role of these genes in carotid atherosclerosis. Unstable plaques are defined by a large necrotic core, thin fibrous cap, punctate calcification, and heightened inflammation39. Previous studies have also pointed out that cell senescence may play an important role in the progression mechanism of unstable plaques and is closely related to the influence of immune microenvironment40. These vulnerable atherosclerotic plaques are major contributors to thromboembolic events in carotid, coronary, and lower extremity arteries41, making early detection and prevention of plaque rupture or erosion clinically imperative. A significant reduction in SOD1, DDX42, and PDLIM1 expression in unstable plaques compared to stable ones suggests that these genes play a protective role in inhibiting the pathological progression of carotid atherosclerosis. Notably, this study provides the first evidence that DDX42, an ATP-dependent RNA helicase 42 (DEAD(Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 42, along with superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1), is implicated in the onset and progression of carotid atherosclerosis, identifying these genes as key components in lactylation associated with the disease. DExH/D-box helicases, such as DDX42, are essential nucleic acid and ribonucleoprotein remodelers, with roles in nucleic acid metabolism, including replication, gene expression, and post-transcriptional modifications. DDX42, a member of the DExH/D-box helicase family and the DEAD box RNA helicase superfamily, plays a yet-to-be fully understood role potentially linked to both intrinsic and innate antiviral immunity42. This study revealed a significant inverse correlation between DDX42 expression and levels of CD56high NK cells, γδ T cells, and Tfh cells. Low DDX42 expression is predominantly associated with enrichment in immune-related pathways. SOD1, a key enzyme, mitigates cellular oxidative stress by converting superoxide radicals into molecular oxygen and hydrogen peroxide, acting as a primary defense against oxidative damage caused by reactive oxygen species43,44. Dysregulation of SOD1 activity has been implicated in the pathogenesis of cancer and neurodegenerative diseases45. Oxidative stress is a known contributor to the progression of atherosclerosis46. As an antioxidant gene, SOD1 is essential for scavenging reactive oxygen species, with recent studies highlighting its roles in metabolic regulation, redox balance, and transcriptional modulation47. The study identified a significant association between reduced SOD1 expression and the increased production of reactive oxygen and nitrogen species, suggesting an activation of oxidative stress within atherosclerotic plaques. The observed downregulation of SOD1 in these plaques underscores its role in the oxidative stress response during atherosclerosis. Furthermore, PDZ and LIM domain protein 1 (PDLIM1), a cytoskeletal protein, acts as a scaffold for the assembly of multi-protein complexes. Precise regulation of PDLIM1 is critical for maintaining physiological homeostasis, impacting cytoskeletal organization and synapse formation. Research has revealed that PDLIM1 expression is markedly reduced in endothelial cells of intracranial aneurysms, where silencing of the PDLIM1 gene impairs the viability, migration, and tube formation of vascular endothelial cells. Conversely, PDLIM1 overexpression has been observed to attenuate intracranial aneurysms in vivo48. Additionally, PDLIM1 plays a role in reducing phosphorylated p65 levels and in suppressing the secretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines and chemokines49. Gong et al. reported that miR-150 mitigates atherosclerosis progression and inflammatory factor secretion through the upregulation of PDLIM1, which in turn enhances plaque stability50. Furthermore, this study identified a significant negative correlation between PDLIM1 and Tfh cells, Th17 cells, and macrophages, with functional enrichment analysis indicating its involvement in various immune signaling pathways.

This study investigated three lactylation-related hub genes implicated in the onset and progression of carotid atherosclerosis, proposing their potential as biomarkers and therapeutic targets. The findings contribute to a deeper understanding of lactylation’s role in carotid atherosclerosis, laying the groundwork for future research and clinical application. Nonetheless, the study is limited by a small sample size and the inherent heterogeneity of carotid atherosclerosis, necessitating cautious interpretation of the results. Furthermore, the specific pathophysiological mechanisms by which these lactylation-related genes impact carotid atherosclerosis require further elucidation to confirm their biological significance. Additionally, the study assessed hub gene expression levels in relation to plaque stability. It should be noted that certain plaques may contain significant calcium deposits, which could alter plaque morphology and potentially affect the integrity of the fibrous cap during freezing microtome sectioning. Further studies involving larger cohorts are necessary to validate these observations due to the limited tissue sample size. Notably, this study identified three lactylation-related differential genes—SOD1, DDX42, and PDLIM1—differentially expressed between carotid plaques and normal carotid tissue, utilizing transcriptome and single-cell sequencing techniques for the first time. These genes may provide critical insights into the pathological mechanisms underlying carotid plaque formation and represent potential therapeutic targets from both metabolic and immunological perspectives. Subsequent research should focus on clinical validation of these results. Lactylation, as an emerging epigenetic modification, has an unclear role in atherosclerosis. The mechanisms and functions of the three biomarkers in the progression of carotid atherosclerosis warrant further exploration. Although research into lactylation-mediated epigenetic regulation is still in its infancy, it holds considerable potential. Continued investigation is anticipated to elucidate the intricate mechanisms underlying atherosclerosis, potentially leading to the development of targeted therapeutics and novel strategies for its management.

Conclusions

By combining scRNA-seq and Bulk transcriptome data in this study, three lactylation-associated genes SOD1, DDX42 and PDLIM1 were identified in carotid atherosclerosis samples, providing targets for the diagnosis and treatment of carotid atherosclerosis samples.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

None

Abbreviations

- GEO

Gene expression omnibus

- BP

Biological process

- CC

Cellular component

- MF

Molecular function

- KEGG

The kyoto encyclopedia of genes and genomes

- GSEA

Gene set enrichment analysis

- RSF

Random survival forest

- Enet

Elastic net

- plsRcox

Partial least squares regression for cox

- SuperPC

Supervised principal component

- GBM

Generalized boosting model

- survival-SVM

Survival support vector machine

- LOOCV

Leave-one-out cross-validation

- AUC

Area under the ROC curve

- ssGSEA

Single sample gene set enrichment analysis

- H&E

Hematoxylin and eosin

- DDX42

DEAD (Asp-Glu-Ala-Asp) box polypeptide 42

- SOD1

Superoxide dismutase

- PDLIM1

PDZ and LIM domain protein 1

Author contributions

G L: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software Y S: Data curation, Writing- Original draft preparation. S Y: Visualization, Investigation. B Z: Supervision. P H: Writing- Reviewing and Editing.

Funding

None.

Data availability

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) with the primary accession code GSE159677, GSE21545, GSE24495, and GSE43292.

Declarations

Competing interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval

All authors confirm that all experimental schemes have been approved by the Ethics Committee of the First Affiliated Hospital of Harbin Medical University. All authors confirm that all methods were carried out in accordance with relevant guidelines and regulations. All authors confirm that informed consent was obtained from all subjects and/or their legal guardian(s).

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-025-00834-5.

References

- 1.Taleb, S. Inflammation in atherosclerosis. Arch. Cardiovasc. Dis.109, 708–715 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kanter, J. E. et al. Diabetes promotes an inflammatory macrophage phenotype and atherosclerosis through acyl-CoA synthetase 1. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci.109, E715–E724 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Golledge, J., Greenhalgh, R. M. & Davies, A. H. The symptomatic carotid plaque. Stroke31, 774–781 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Feigin, V. Global, regional, and national disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) for 315 diseases and injuries and healthy life expectancy (HALE), 1990–2015: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2015. (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 5.Herrington, W., Lacey, B., Sherliker, P., Armitage, J. & Lewington, S. Epidemiology of atherosclerosis and the potential to reduce the global burden of atherothrombotic disease. Circ. Res.118, 535–546 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Oorni, K. et al. Acidification of the intimal fluid: The perfect storm for atherogenesis. J. Lipid. Res.56, 203–214. 10.1194/jlr.R050252 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.van Tuijl, J., Joosten, L. A. B., Netea, M. G., Bekkering, S. & Riksen, N. P. Immunometabolism orchestrates training of innate immunity in atherosclerosis. Cardiovasc. Res.115, 1416–1424. 10.1093/cvr/cvz107 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhao, W. et al. M6A plays a potential role in carotid atherosclerosis by modulating immune cell modification and regulating aging-related genes. Sci. Rep.14, 60. 10.1038/s41598-023-50557-8 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zhang, D. et al. Metabolic regulation of gene expression by histone lactylation. Nature574, 575–580. 10.1038/s41586-019-1678-1 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wan, N. et al. Cyclic immonium ion of lactyllysine reveals widespread lactylation in the human proteome. Nat. Methods.19, 854–864. 10.1038/s41592-022-01523-1 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Haas, R. et al. Lactate regulates metabolic and pro-inflammatory circuits in control of T cell migration and effector functions. PLoS Biol.13, e1002202. 10.1371/journal.pbio.1002202 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li, H., Sun, L., Gao, P. & Hu, H. Lactylation in cancer: Current understanding and challenges. Cancer Cell42, 1803–1807. 10.1016/j.ccell.2024.09.006 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang, R. et al. Identification of hub genes in unstable atherosclerotic plaque by conjoint analysis of bioinformatics. Life Sci.262, 118517. 10.1016/j.lfs.2020.118517 (2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen, M. et al. Weighted gene co-expression network analysis identifies crucial genes mediating progression of carotid plaque. Front. Physiol.12, 601952. 10.3389/fphys.2021.601952 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Xu, B. F. et al. Identification of key genes in ruptured atherosclerotic plaques by weighted gene correlation network analysis. Sci. Rep.10, 10847. 10.1038/s41598-020-67114-2 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fernandez, D. M. et al. Single-cell immune landscape of human atherosclerotic plaques. Nat. Med.25, 1576–1588. 10.1038/s41591-019-0590-4 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zheng, K. et al. Identification of immune infiltration-related biomarkers in carotid atherosclerotic plaques. Sci. Rep.13, 14153. 10.1038/s41598-023-40530-w (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cheng, Z. et al. Lactylation-related gene signature effectively predicts prognosis and treatment responsiveness in hepatocellular carcinoma. Pharmaceuticals (Basel)10.3390/ph16050644 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Liu, X., Zhang, Y., Li, W. & Zhou, X. Lactylation, an emerging hallmark of metabolic reprogramming: Current progress and open challenges. Front. Cell Dev. Biol.10, 972020. 10.3389/fcell.2022.972020 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Liu, Z. P., Wu, C., Miao, H. & Wu, H. RegNetwork: an integrated database of transcriptional and post-transcriptional regulatory networks in human and mouse. Database (Oxford).10.1093/database/bav095 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Virmani, R., Burke, A. P., Farb, A. & Kolodgie, F. D. Pathology of the vulnerable plaque. J. Am. Coll. Cardiol.47, C13-18. 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.065 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Giannotti, N. et al. Association between 18-FDG positron emission tomography and MRI biomarkers of plaque vulnerability in patients with symptomatic carotid stenosis. Front. Neurol.12, 731744. 10.3389/fneur.2021.731744 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Goikuria, H., Vandenbroeck, K. & Alloza, I. Inflammation in human carotid atheroma plaques. Cytokine Growth Factor Rev.39, 62–70. 10.1016/j.cytogfr.2018.01.006 (2018). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Baradaran, H. & Gupta, A. Brain imaging biomarkers of carotid artery disease. Ann. Transl. Med.8, 1277. 10.21037/atm-20-1939 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Liu, W., Zhao, Y. & Wu, J. Gene expression profile analysis of the progression of carotid atherosclerotic plaques. Mol. Med. Rep.17, 5789–5795. 10.3892/mmr.2018.8575 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ammirati, E., Moroni, F., Norata, G. D., Magnoni, M. & Camici, P. G. Markers of inflammation associated with plaque progression and instability in patients with carotid atherosclerosis. Mediators Inflamm.2015, 718329. 10.1155/2015/718329 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tada, H. et al. Clinical impact of carotid plaque score rather than carotid intima-media thickness on recurrence of atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease events. J. Atheroscler. Thrombosis.27, 38–46 (2020). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu, R., Yuan, W. & Wang, Z. Advances in glycolysis metabolism of atherosclerosis. J. Cardiovasc. Transl. Res.16, 476–490 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Shantha, G. P. S. et al. Association of blood lactate with carotid atherosclerosis: The atherosclerosis risk in communities (ARIC) carotid MRI study. Atherosclerosis228, 249–255 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Manoharan, I., Prasad, P. D., Thangaraju, M. & Manicassamy, S. Lactate-dependent regulation of immune responses by dendritic cells and macrophages. Front. Immunol.12, 691134. 10.3389/fimmu.2021.691134 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang, T. et al. Lactate induced protein lactylation: A bridge between epigenetics and metabolic reprogramming in cancer. Cell Prolif.56, e13478 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu, J., Chen, P., Zhou, J., Li, H. & Pan, Z. Prognostic impact of lactylation-associated gene modifications in clear cell renal cell carcinoma: Insights into molecular landscape and therapeutic opportunities. Environ. Toxicol.39, 1360–1373 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao, J. et al. Difference of immune cell infiltration between stable and unstable carotid artery atherosclerosis. J. Cell Mol. Med.25, 10973–10979 (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.He, S. et al. Gut intraepithelial T cells calibrate metabolism and accelerate cardiovascular disease. Nature566, 115–119 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kubatova, H., Poledne, R. & Piťha, J. Immune cells in carotid artery plaques: What can we learn from endarterectomy specimens?. Int. Angiol. J. Int. Union Angiol.39, 37–49 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ouyang, J., Wang, H. & Huang, J. The role of lactate in cardiovascular diseases. Cell Commun. Signal.21, 317 (2023). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Jin, J. et al. Machine learning classifies ferroptosis and apoptosis cell death modalities with TfR1 immunostaining. ACS Chem. Biol.17, 654–660 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waljee, A. K. et al. Artificial intelligence and machine learning for early detection and diagnosis of colorectal cancer in sub-Saharan Africa. Gut71, 1259–1265 (2022). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Shaw, L.J., Blankstein, R., Min, J.K. Outcomes in stable coronary disease: is defining high-risk atherosclerotic plaque important? In: American College of Cardiology Foundation Washington DC; 302–304 (2019). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 40.Cai, G. F. et al. Decoding marker genes and immune landscape of unstable carotid plaques from cellular senescence. Sci. Rep.14, 26196. 10.1038/s41598-024-78251-3 (2024). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Yuan, J. et al. Imaging carotid atherosclerosis plaque ulceration: comparison of advanced imaging modalities and recent developments. Am. J. Neuroradiol.38, 664–671 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bonaventure, B. & Goujon, C. DExH/D-box helicases at the frontline of intrinsic and innate immunity against viral infections. J. Gen. Virol.103, 001766 (2022). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ighodaro, O. M. & Akinloye, O. A. First line defence antioxidants-superoxide dismutase (SOD), catalase (CAT) and glutathione peroxidase (GPX): Their fundamental role in the entire antioxidant defence grid. Alexandria J. Med.54, 287–293 (2018). [Google Scholar]

- 44.Montllor-Albalate, C. et al. Extra-mitochondrial Cu/Zn superoxide dismutase (Sod1) is dispensable for protection against oxidative stress but mediates peroxide signaling in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Redox Biol.21, 101064 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Atiya, A. et al. Unveiling promising inhibitors of superoxide dismutase 1 (SOD1) for therapeutic interventions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.253, 126684 (2023). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kattoor, A. J., Pothineni, N. V. K., Palagiri, D. & Mehta, J. L. Oxidative stress in atherosclerosis. Curr. Atheroscler. Rep.19, 1–11 (2017). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Banks, C. J. & Andersen, J. L. Mechanisms of SOD1 regulation by post-translational modifications. Redox Biol.26, 101270 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Yan, Y. et al. Decreased PDLIM1 expression in endothelial cells contributes to the development of intracranial aneurysm. Vasc. Med.29, 5–16 (2024). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ono, R., Kaisho, T. & Tanaka, T. PDLIM1 inhibits NF-κB-mediated inflammatory signaling by sequestering the p65 subunit of NF-κB in the cytoplasm. Sci. Rep.5, 18327 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gong, F.-H. et al. Reduced atherosclerosis lesion size, inflammatory response in miR-150 knockout mice via macrophage effects. J. Lipid Res.59, 658–669 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Sequence data that support the findings of this study have been deposited in the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) with the primary accession code GSE159677, GSE21545, GSE24495, and GSE43292.